-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Benito Arruñada, Giorgio Zanarone, Nuno Garoupa, Property Rights in Sequential Exchange, The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Volume 35, Issue 1, March 2019, Pages 127–153, https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewy023

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We analyze the “sequential exchange” problem in which traders have imperfect information on earlier contracts. We show that under sequential exchange, it is in general not possible to simultaneously implement two key features of markets—specialization between asset ownership and control, and impersonal trade. In particular, we show that in contrast with the conventional wisdom in economics, strong property rights—enforceable against subsequent buyers—may be detrimental to impersonal trade because they expose asset buyers to the risk of collusive relationships between owners and sellers. Finally, we provide conditions under which a mechanism that overcomes the trade-off between specialization and impersonal trade exists. We characterize and discuss such mechanism. Our results provide an efficiency rationale for how property rights are enforced in business, company and real estate transactions, and for the ubiquitousness of “formalization” institutions that the literature has narrowly seen as entry barriers. (JEL D23, D83, K11, K22)

1. Introduction

From Coase (1960) to Akerlof (1970), Williamson (1979), and Grossman and Hart (1986), economic models assume that transactors are well informed on the allocation of property rights prior to contracting. Although this assumption is useful to keep formal analysis tractable, it contradicts the reality of modern markets. Thus, a buyer of assets may not know whether she is buying from the owner, an authorized agent of the owner, a nonauthorized agent, or even a fraudulent seller. Similarly, a company’s client, supplier, or investor, may ignore whether the manager she is dealing with has been previously authorized by shareholders to conduct that particular business on behalf of the company. As a result, transactors may acquire rights over an asset that are inconsistent with a prior allocation of rights established by potentially hidden contracts.

This article develops one of the first formal economic models analyzing this fundamental “sequential exchange” problem [an earlier important model is Ayotte and Bolton (2011); we discuss the two papers’ distinctive yet complementary contributions in our literature review in Section 6]. We argue that under sequential exchange, if agents suffer from limited liability, the central question is who should be allocated an asset in case of conflict—that is, whether owners’ rights over the asset should be enforced against subsequent buyers, as “property rights,” or only against the seller, as “personal rights.” We show that under these polar institutional regimes, it is in general not possible to simultaneously support two key features of markets—namely, specialization of asset ownership and control, and impersonal trade.1 In particular, we show that in a world where asset owners’ property rights are strictly enforced, these may use their personal relationships to secretely collude with agents against unrelated future acquirers of the assets, who will therefore not buy in anticipation of such collusion. In other words, relational “originative” contracts between owners and agents may crowd out impersonal “subsequent” contracts between agents and third parties. At the same time, however, if owners’ property rights are not enforced, they will not delegate control of their assets to agents unless they have a tight relationship with them, hampering both efficient specialization and trade.

We conclude our analysis by showing how complex and sometimes misunderstood institutions, such as adverse possession, the rules of good faith purchase, and property and company registries, share the common goal of jointly supporting specialization and impersonal trade. An important implication of this analysis is that the adaptation and updating of these institutions should be carried out without hampering their fundamental market-preserving function.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents our sequential exchange model. Section 3 demonstrates the inefficiency of unconditional property rights. Section 4 studies the conditions under which property rights should be enforced, and discusses how our results relate to the current economic literature on property rights. Section 5 discusses some key applications and illustrations of the model. Section 6 discusses our article’s contributions to the literature. Section 7 concludes.

2. The model

2.1 Sequential Exchange

The economy consists of three risk-neutral players, P [principal], A [agent], and T [third party], and an asset owned by P at the outset of play. The simplest interpretation is that A is the manager of P’s firm but we discuss alternative interpretations at the end of this section.

We model a situation in which an impersonal market contract between parties A and T may interact with, and be endangered by a previous relational contract between A and P. We assume there are both gains from specialization between A and P and gains from impersonal trade between A and T. Regarding specialization, we assume the asset’s value to P is if P controls it, and if P delegates control to A. Regarding impersonal trade, we assume that T’s valuation of the asset exceeds P’s valuation by .2 Notice the double role of A as P’s agent. On the one hand, even in the absence of trade with T, A creates additional value () by managing P’s asset. For instance, may measure P’s specialization in tasks such as monitoring or ownership, as emphasized by the agency literature (e.g. Fama and Jensen 1983). On the other hand, A is also essential to realize the gains from trade, x—we may think, for instance, that only A, not P, has the skills or time necessary to sell the asset to T.3

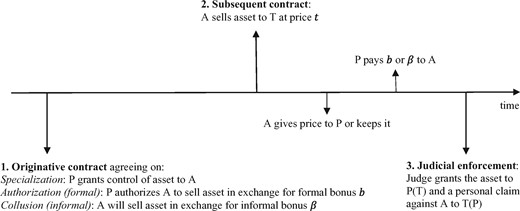

Figure 1 summarizes the sequence of moves in the model. In the first stage, P may enter an “originative” contract with A, in which P delegates control of the asset to A (hereafter, “specialization”), and may also authorize A to sell the asset on P’s behalf, in exchange for a bonus. If the authorization is formal (i.e. court-enforceable), we denote A’s bonus as . If the authorization is informal (i.e. not court-enforceable), we denote the bonus as . For reasons that will become apparent in a moment, we call the case where P informally authorizes A “collusion.” In the second stage, which we call the “subsequent” contract, A may sell the asset to T, in exchange for price .4 Finally, in the third stage, if A has entered a contract with T without formal authorization, the judge allocates the asset to either P or T, assigning a mere claim against A to the loser, respectively T or P.5 Using the language of property law (Merrill and Smith 2000; Hansmann and Kraakman 2002), we will say that if the judge assigns the asset to P and a claim against A to T, P held a “property” (or in rem) right over the asset. Conversely, if the judge assigns the asset to T and a claim against A to P, P held only a “personal” (or in personam) right over the asset.

Between stage two (subsequent contract) and three (judicial enforcement), A may decide to give the sale price to P or keep it; and, after observing A’s choice, P may pay the appropriate bonus ( or ) to A.

2.1.1 Alternative Interpretations of the Model

When presenting the model, we mentioned that A could be the manager of P’s firm or simply P’s selling agent. Still, a sequential exchange problem takes place in many other contexts of specialization (i.e. separation) of ownership and control in which P is an owner and A is an agent that gets control of P’s asset. For example, it is the case with all types of rentals of durable assets (houses, land, planes, automobiles, factories, etc.). It also takes place in one of the most common transactions in modern economies: when firms transfer possession of goods to other firms in the productive chain. This happens, most clearly, when manufacturers deliver merchandise to retailers who sell to final customers. In all these different cases, in essence, by P ceding control (transferring possession) of the goods to A, both parties reach specialization advantages at the price of creating new contractual problems in the ultimate sale of such goods to final buyers. In case of conflict (e.g. the retailer does not pay the manufacturer), judges will have to adjudicate the goods to the manufacturer or the buyer, granting the losing party a mere personal claim on the retailer. As shown below, these judicial decisions will affect the degree of specialization and the extent of impersonal exchanges.

2.2 Contractual Frictions and the Model’s Assumptions

Assumptions in our sequential-exchange model capture the key frictions that may arise when relational and impersonal contracts interact. First, we assume that when deciding whether to buy the asset, T does not know whether A is authorized to sell (and, a fortiori, whether P and A are colluding against him)—that is, T does not observe the originative contract between P and A. As shown below, this may prevent the gains from impersonal trade from being realized.6

Second, we assume that A has limited liability, and hence may have an incentive to behave opportunistically toward T or P, potentially endangering both specialization and impersonal trade. In particular, we assume for most of the model that A has no wealth that can be recovered by P or T through a lawsuit. This assumption captures the fact that in advanced economies, agents do not have enough personal wealth to effectively bond their large transactions. While assuming that A has zero cash is a simplification, we show in Section 1 of the Appendix that the model’s results continue to hold provided that A’s ability to pay damages to P and T is not significant.

Third, we assume that P and A have a personal relationship, whose breakdown may cause losses to them. We capture this “relational liability” in the simplest possible way by assuming that if A violates the originative contract with P (by selling the asset against P’s will or keeping the sale price instead of giving it to P), he suffers an exogenous disutility . Similarly, P incurs a disutility if he violates the originative contract (by not paying the promised bonus to A).7 For instance, if A manages other assets owned by P in addition to the focal asset modeled here, may represent the future payoff losses that arise once A stops managing those assets following a deviation. In the conclusion, we discuss how future work may model the analytically more complex case of endogenous relational liability.

As we shall see in a moment, relational liability plays a dual role in the model. On one hand, it prevents A from being opportunistic toward P, thus favoring specialization. On the other hand, it enables P and A to collude against T, thereby hampering impersonal trade. To make collusion interesting, we assume that . As shown below, this ensures that the parties’ relational liability is large enough for a collusive agreement between P and A to be self-enforcing.

2.3 Payoffs

Given the timeline and assumptions discussed above, Tables 1 and 2 show the payoffs as a function of the three players’ moves for the two alternative cases where P has a property or a personal right over the asset, respectively.

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, no collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A keeps price | |||

| Unauthorized sale, collusion, A transfers price to P | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, collusion | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, collusion | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, collusion | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

| . | P’s payoff . | A’s payoff . | T’s payoff . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If P does not specialize | |||

| If P specializes: | |||

| Authorized sale, A keeps price | |||

| Authorized sale, A transfers price to P | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, no collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A keeps price, collusion | |||

| Unauthorized sale, A transfers price to P, collusion | |||

| No sale (A does not offer or T rejects) |

Two remarks on the structure of payoffs. First, we assume that when P has a property right over the asset and colludes with A, P can keep both the asset and the price. The rationale behind this assumption is that P and A keep their collusive agreement informal. Therefore, T cannot show in court that despite lacking a formal authorization to sell, A informally acted as P’s agent. In Section 3 of the Appendix, we analyze how the model changes under imperfect collusion (i.e. when T may be able to recover part of the price from P). Second, when P has a personal right over the asset, collusion between P and A does not harm T because she keeps the asset anyway.

2.4 The Benchmark Case Where Property Rights are Irrelevant

If T observes the originative contract and A has unlimited liability, the first best is achieved irrespective of whether P has a property right over the asset.

Proposition 1 is a direct consequence of the Coase theorem. With perfect information on the originative contract and unlimited liability—a hypothetical situation that approaches a small world of local, personal markets—and given that no other transaction costs are present in the model, efficient exchange can be achieved under any institutions governing the allocation of assets. In that case, our sequential exchange environment would be equivalent to an environment where P contracts directly with T, as assumed in most of the economics of contracts. Only under these narrow conditions, which are not satisfied in impersonal markets, it is sensible to disregard the differences between property/real and contractual/personal rights, as most traditional economic analyses do.

In the rest of the article we show how, given T’s imperfect information about the originative contract and A’s limited liability, the equilibrium outcome depends on whether P has a property right, and that enforcing property rights may or may not be efficient, depending on the circumstances. Therefore, most traditional economic analyses fail to capture essential elements of modern market transactions.

3. Unconditional Property Rights

We begin by analyzing two polar cases that correspond to the main legal solutions. In the first one, the law unconditionally enforces property rights—that is, in case of unauthorized sale, the judge gives the asset to P and grants T a mere personal claim against A. In the second case, the law does not enforce property rights—that is, in case of unauthorized sale, the judge gives the asset to T and grants P a personal claim against A.

3.1 Equilibrium Concept and Strategies

Formally, we analyze pure-strategy perfect Bayesian equilibria (PBEs) of the imperfect information game between P, A and T. In our game, P’s strategy consists of five actions—namely: (1) whether to specialize at stage 1; (2) whether to authorize A to sell, (3) whether to collude with A, and (4) what formal bonus (or informal bonus , in case of collusion) to offer, at stage 2; and in case of collusion, (5) whether to pay the promised informal bonus, .

A’s strategy consists of two actions, both taken at stage 2—namely, which sale price to ask T, and if T accepts, whether to keep the price or to transfer it to P. Finally, T’s strategy consists of one action—namely, whether to accept or reject A’s offer. In the event that A makes her an offer , T also has a belief about A’s contractual status—that is, about whether A has been authorized to make such an offer. We denote T’s belief that A is authorized to make offer as , and T’s belief that A is not authorized as .

3.2 Case 1: Property Rights are Always Enforced

If T knows that P will be given the asset in case of conflict, she is exposed to the risk of entering an unenforceable contract with A. This risk is generated by the fact that P and A can rely on their personal relationship to collude against T. We show below that given A’s limited damage liability, “collusion” between P and A (in general, their ability to privately enforce transactions) has unraveling consequences for trade.

If property rights are unconditionally enforced, there is no PBE with trade.

3.3 Case 2: Property Rights are Never Enforced

This analysis proves our next result.

If property rights are unenforceable, there is a unique PBE. In this PBE, A sells the asset to T when his relationship with P is strong and the gains from specialization are large, such that condition (3) holds. Otherwise, trade does not occur, and the gains from specialization are lost.

3.4 Discussion of Contractual Restrictions

One may wonder whether the inefficiencies highlighted in this section could be avoided by allowing for more complex arrangements (in the vein of the literature on optimal contracts, e.g.) between P, A and T—such as A posting collateral, T postponing the payment till the asset is delivered, or T asking to pay P directly. Here we briefly discuss why these mechanisms are not viable in our setting.

Regarding collateral, it is ruled out by our assumption that A has zero cash. In the first subsection of the Appendix we relax this assumption and allow for A to have some cash that can be used to bond his transaction with P and T and pay damages. We show that, provided that A’s liability is not too significant—which is realistic in the impersonal exchange environment we model—, the frictions analyzed in this section are still present.

Moreover, T’s postponing the payment would not protect him or P from A’s opportunism. Start by noticing that specialization implies that A is in possession of the asset—that is, A can deliver the asset to T irrespective of whether or not the transfer has been authorized by P. Therefore, in the personal right regime, even if T refuses to pay until the asset is delivered does not protect P in case A decides to keep the price. Second, if P has a property right, he will have a strong incentive to wait till T pays before reclaiming the asset, so waiting does not protect T from collusion between P and A.

Finally, T cannot solve the sequential exchange problem by insisting on paying P directly. On one hand, T may not even know who P is (as in the example where a good faith purchaser buys goods from a merchant, discussed in Section 5). On the other hand, even if T knows who P is (for instance, because P is sole owner of a company that A manages), A may falsely facilitate forms of payment (e.g. A could claim that he is giving P’s bank account details to T for the payment when in fact he is giving his own account details). At the limit, completely avoiding this problem would require P to be both owner and manager of the firm, which is incompatible with delegation in our setup.

4. Conditional Property Rights

The analysis conducted so far shows that in our sequential exchange environment, given T’s imperfect information on the originative contract and A’s limited liability, both unconditional enforcement of property rights and unconditional refusal to enforce them may be inefficient. In this section, we show that efficiency can be improved by conditioning the enforcement of property rights to verifiable information.

4.1 Property Rights Conditional on Explicit Consent

Consider a mechanism whereby at stage 1, P makes his originative contract with A public. Doing so in a way that guarantees that the published information cannot be manipulated ex post may be costly (see Section 5.3) but, if feasible, it removes the informational asymmetry that T suffers when contracting with A, thereby potentially restoring efficiency. To illustrate the benefits of such an explicit “public notice” mechanism, we analyze a version, consistent with observed practice, where in case of conflict between P and T, the asset is allocated solely based on the originative contract published by P, that is, disregarding any other contract between A and P that they may have kept private.

Definition. under a right-switching mechanism (RSM), P is given the asset in case of conflict if the contract published by P does not authorize the sale between A and T, whereas T is given the asset if the contract published by P authorizes the sale.

RSM corrects both of the inefficiencies that arise under unconditional property rights. On one hand, it removes P’s incentive to collude with A. On the other hand, RSM removes T’s incentive to buy regardless A’s authority, which arises in the absence of property rights, thereby making it safe for P to specialize. In particular, notice that under RSM, P would publicly make A’s authorization to sell contingent on T transferring the price to P’s account, so T would not accept to pay A directly and consequently, A could not act opportunistically.

RSM implements the first best.

We formally prove our proposition by showing that given RSM, there is a unique PBE where: (1) P specializes, publishes a contract authorizing A to sell the asset at price and have T transfer the price to P, and offers A a small formal bonus, ; (2) A offers the authorized sale terms to T; and (3) T accepts A’s offer. Notice first that if P chooses (1), (2) and (3) are the unique best responses for A and T: given (1), T is better off buying because RSM insures that she will keep the asset, and A is better off selling, having the price transferred to P and getting a small bonus than not selling and getting zero. Notice next that P has no incentive to deviate from (1). On one hand, P cannot gain by authorizing A to sell at a different price or by paying a different bonus, because is the highest price acceptable for T, and zero is the lowest bonus acceptable for A. On the other hand, P cannot gain by prohibiting the sale, because if he did so, RSM implies that T would never buy from A for fear of losing the asset that. We have thus proved that (1)–(3) describe a unique PBE ■

4.2 Property Rights Conditional on Implicit Consent

Suppose explicit mechanisms for the publication of consent, such as RSM, are not available or are too costly to implement. We now show that even in this case, efficiency may be improved by conditioning property rights to verifiable evidence on P’s implicit consent to sell, although the first best may not be achieved.8

Proposition 3 implies that if the law grants P a mere personal claim against A, rather than a property right on the asset, efficient trade occurs in equilibrium only if (3) holds—that is, if P’s relationship with A is sufficiently strong, and the gains from specialization sufficiently high, such that P prefers to specialize and permit trade. If (3) does not hold, trade fails as in the case where property rights are unconditionally enforceable, but the total surplus is even lower because, lacking such legal protection, P prefers to forgo the gains from specialization in order to keep control of the asset and thus prevent its sale. This suggests that in the absence of explicit mechanisms like RSM, the enforcement of property rights should in some cases depend on environment characteristics that provide evidence of whether (3) holds—that is, of whether P has implicitly consented to the sale.

In the absence of explicit mechanisms for publishing P’s consent, enforcing property rights is efficient if and only if P’s relationship with A and the gains from specialization are weak, such that condition (3) does not hold.

Proof. absent public notice mechanisms, enforcing property rights is efficient if, and only if it achieves a higher total surplus than would be achieved if property rights were not enforced: , or . This condition is satisfied when 3 does not hold (), whereas it is not satisfied when 3 holds (). ■

4.3 Explicit versus Implicit Mechanisms

Conditioning property rights on evidence of P’s explicit consent is efficient if the gains from trade, , are large, if the cost of producing such evidence, , is low, and if the likelihood that P would specialize in the absence of property rights, , is low.

Proof. by inspection of (4).

5. Applications

There are two key insights from our theoretical analysis. First, when parties contracting over an asset cannot observe previous “originative” contracts, optimal property rights solve a trade-off between ex ante gains from specialized asset management (which call for enforcing property rights) and ex post gains from trade (which asks for enforcing personal rights). Second, conditioning the enforcement of property rights to public evidence of the originative contract overcomes the trade-off and is therefore efficient, provided that the cost of producing such evidence is low relative to the gains from specialization and trade. In this section, we discuss how our theoretical framework applies to or sheds light on key market institutions underlying both company and property transactions.

5.1 Property and Company Registries

Consistent with our analysis, the enforcement of property rights is often contingent on institutions that provide public evidence of past contracts over the underlying assets. In a company context, historically, a contract entered by a manager used to commit its company—that is, shareholders lost their property rights over the company’s assets—only if such commitment fell within the scope of the manager’s authorization, as filed in a public registry (Armour and Whincop 2007; Arruñada 2010). Today, this happens even without any explicit filing, but only if the manager is—depending on the jurisdiction—registered as a manager or publicly acting as such. Similarly, in the context of land, the law typically grants rightholders (owners, mortgagees) a property right—that is, a right valid against subsequent acquirers of competing property rights in the same land—only in the presence of verifiable evidence of their holding. In old times, this evidence used to be produced, for ownership, through the public delivery of possession, as in the Roman mancipatio ceremony (Arruñada 2015). However, possession is out of the question for abstract rights such as mortgages—a main reason behind the creation of public property registries (e.g. Arruñada 2003; Arruñada and Garoupa 2005).

As mentioned above, our framework also suggests that the enforcement of property rights should be contingent on explicit/registered—as opposed to implicit/unregistered—evidence of the owners’ consent (or lack thereof) only if the cost of developing and maintaining registries is small relative to the gains from specialization and trade. This prediction is also consistent with the broad historical evolution of property and company institutions. In particular, the evidence to establish whether unauthorized contracts entered by a manager do or do not commit the company has switched from implicit consent (apparent authority) to explicit consent (describing the manager’s authority or merely recording of her appointment in a company registry) as the scope and size of markets and trade has expanded. In a similar vein, property registries as an explicit mechanism to define property rights over land are more developed and successful in advanced market economies. By making impersonal trade viable, these institutions make it easier to break the limits of local and personal markets that characterize traditional and less-developed economies.

By performing a comparative analysis of the costs and benefits of publicity mechanisms, our article also sheds new light on the debate on property and business institutions initiated by De Soto (1989) and Djankov et al. (2002), and reflected in influential policy initiatives like the Doing Business Project (World Bank 2004–2018). This literature emphasizes the rent-seeking costs of “formalizing” business companies via institutions such as company registries, and thus primarily views registries (and other formalization procedures not analyzed here) as entry barriers that should be simplified, if not outright eliminated. By showing the benefits of registries as facilitators of trade, our model suggests that their elimination is not so obviously efficient.

As to simplification, the model calls for a case-by-case approach. In particular, it suggests that simplifying formalization procedures by reducing registry verification is not optimal when the gains from trade are large. To understand why simplified registration may hamper trade, consider a hypothetical company registry with limited verification of managerial authority. Suppose our RSM mechanism is played using this simpler, and hence less accurate registry—that is, judges allocate the asset to the company’s clients or investors (T) if, and only if the registry reports that the manager (A) is authorized to sell. The clients will not buy unless the manager’s authorization is registered, so they are protected from collusion between the firm’s owners (P) and the manager (A), as in the case of perfect registries analyzed in Section 4. However, the owners are now exposed to the risk of managerial opportunism—that is, the manager may exploit the inaccurate registry to sell without authorization. At the limit (i.e. as the registry’s quality goes to zero), this would induce the owners to manage the company themselves, or not to create it in the first place, hampering both specialization and trade, as shown in Section 3.3. In practice, legal systems avoid such a perverse outcome by enforcing the RSM selectively, what amounts to using registry information as one more piece of evidence instead of the only relevant evidence. This is the standard case when company registries are “ministerial” and only verify formal aspects. This solution endangers trade by allowing owners and managers to collude against third parties, as shown in Section 3.2. Moreover, to safeguard against collusion, third parties must spend considerable resources to verify the validity of registered information ex post (e.g. Arruñada and Manzanares 2016).

More broadly, our analysis suggests that both costs and benefits of formalization should be factored into institutional design. At the same time, it also suggests that there may be considerable value in developing technologies that produce reliable public evidence on originative contracts without generating the direct and indirect costs of the existing formalization mechanisms. This conclusion is consistent with the current interest in applying the blockchain technology beyond Bitcoin.

5.2 The Law of Good Faith Purchase

As documented by numerous scholars (e.g. Medina 2003; Arruñada 2010, 2012; Schwartz and Scott 2011), when a seller sells an asset to an innocent buyer, the law generally allows the buyer to keep the asset in case of conflict with the original owner—that is, the owner loses his property right—if the seller is a “merchant” (e.g. UCC 2-403 in the United States, the “market overt” rule in England and other European countries). However, this principle does not typically apply for used goods stores, art galleries, and auction or pawn shops.

Both the general good faith purchase rule and its exceptions appear to be guided by efficiency considerations according to our theory. In particular, a professional merchant is more likely to develop a relational contract with the goods’ owner, and hence less likely to sell those goods against the owner’s will than a nonmerchant seller or a pawnbroker (in terms of the model, the owner-merchant pair will have a higher relational liability, , than the owner-pawnbroker pair). Thus, when the seller is a merchant it is a priori more likely that the original owner appropriates the gains from trade, and hence that she has efficiently separated ownership and control by entrusting the good to the seller—that is, condition (3) holds. Accordingly, when the seller is a merchant it makes sense for the law to presume delegation and refuse to enforce the owner’s property rights against innocent buyers. On the contrary, when the seller is a pawnbroker it is reasonable to presume lack of delegation, and to enforce the owner’s property rights.

5.3 Adverse possession

Adverse possession implies that an owner loses property rights over his assets to a good faith possessor, provided that the latter’s possession is notorious and has lasted for a long enough period (e.g. Lueck and Miceli 2007). This implies that an adverse possessor can sell the assets to third parties, who will be allowed to keep them in case the original owner claims them back. Thus, in the language of our article, adverse possession implies that relative to subsequent transactions with third parties, the original owner’s property rights are enforced if possession of the seller has lasted less than the critical time threshold, but are turned into mere personal claims against the seller if possession has lasted beyond the time threshold.

The time threshold that triggers adverse possession has been observed to vary across both legal systems (e.g. Guerriero 2016) and transaction characteristics. Regarding the former, there is evidence that the number of years necessary to trigger adverse possession is greater in US states with lower land development value (Netter et al. 1986; Baker et al. 2001). Regarding transaction characteristics, it is well known that in Classical Roman law (i.e. within a given legal system) the time necessary to trigger adverse possession (usucapio) of provincial land was longer (longi tempori praescriptio) when the original owner and the possessor were not in the same district (Arruñada 2015).

Our theoretical framework provides a joint efficiency explanation for both the adverse possession principle and the patterns of variation of time terms described above. Regarding the general principle, the legally established time term can be interpreted as the time the original owner has to notice and revoke undesired possession (in terms of our model, to exert the choice of not specializing) if he wants to do so. Then, possession beyond the term indicates that the owner has consented to leave the possessor in control of the asset. If the time term is appropriately chosen, our theory suggests that it is efficient to enforce the original owner’s property rights, even against third parties who may have acquired the asset from the possessor if, and only if possession has not lasted more than the time term. That is exactly what the law does.

Regarding the time term’s patterns of variation, note first that, all else equal, if the original owner and the possessor reside in different districts, it is more difficult for the owner to get notice and repossess the asset. Therefore, it is less likely that possession for a given number of years indicates voluntary delegation of the asset’s control to the possessor, or to put it differently, the critical time term such that voluntary delegation can be presumed is longer. This is consistent with the longer term for different-district as opposed to same-district adverse possession in Roman law. Moving to the cross-jurisdictional evidence, lower land development value indicates lower gains from the specialized management of land. This suggests that holding the years of possession constant, separation of land ownership and possession is less likely to be voluntary in those jurisdictions, and hence the time threshold necessary to presume voluntary separation should be longer. This is consistent with the US empirical evidence.10

6. Contribution to the Literature

Our article relates to the vast economic literature on property rights initiated by Coase (1960), and continued by Demsetz (1967), Barzel (e.g. Barzel 1997), Hart (e.g. Grossman and Hart 1986), and many others (e.g. Libecap 1993; see also Lueck and Miceli 2007, and Segal and Whinston 2013, for recent reviews). Defining property as the right to use and dispose of an asset, much of this literature focuses on how allocating property rights to one or the other party in a bilateral transaction may affect ex ante investments in the asset (e.g. Grossman and Hart 1986; Hart and Moore 1990; Holmstrom and Milgrom 1991, 1994), and the two parties’ ability to bargain over its transfer ex post (e.g. Matouschek 2004; Segal and Whinston 2016).

Relative to this literature, our article brings two central features of modern impersonal markets into the analysis, which importantly affect the role of property rights. The first feature is what we label “sequential exchange”: the potential buyer of rights on an asset (T in our model) may not know whether the seller (A) has been authorized by the asset’s initial owner (P) to transfer such rights; thus, the relevant transaction to be analyzed is (at least) tri-lateral, rather than bilateral. The second feature of impersonal markets incorporated by our model is limited liability: it may not be credible for the law to impose effective penalties on a seller (A) if he expropriates the owner of an asset (P) by selling it against the latter’s will.11

In this environment, the key attribute of property rights is not that they assign (residual) rights of control, but rather, that they “run with the asset,” which is thus assigned to the owner (P), and not to the uninformed acquirer (T), in case of unauthorized transactions (Merrill and Smith 2000; Hansmann and Kraakman 2002; Arruñada 2003). Moreover, whether property rights should be enforced depends on whether the ex ante gains from specialization () are large enough to induce the owner to delegate control of the asset and thus enable its future transfer. If that is the case, enforcing the owner’s property rights against future buyers prevents the gains from trade (), and hence is not optimal. Otherwise, enforcing property rights allows the owner to protect the asset while maintaining separation of ownership and control, and hence is optimal.

A few recent papers have developed economic models of property rights in sequential exchange environments (Medina 2003; Ayotte and Bolton 2011; and Dari-Mattiacci et al. 2016). As explained below, these papers importantly differ from ours in terms of analytical results, applications, and scope. Both Medina (2003) and Dari-Mattiacci et al. (2016) study the sale of stolen goods to a good faith purchaser. Medina (2003) shows that if the owner is entitled to restitution, the buyer’s willingness to pay decreases, while his incentive to investigate the goods’ origin may increase. Thus, depending on which effect dominates, it may be more efficient to allow the buyer to keep the goods. Dari-Mattiacci et al. (2016) develop a model where the good’s price and the probability of theft are endogenously determined, and show that in such a context, value allocation is more important than incentive inducement. The main difference between these papers and ours is that by focusing on buyer incentives as the key benefit of property rights, they are not well suited to analyze complex property and company transactions where buyer investigation is unlikely to be feasible or effective.

Closer to our article, Ayotte and Bolton (2011) develop a model where an entrepreneur’s assets serve as collateral for two sequential loans. They show that under a legal rule granting prior enforcement to the earlier loan (akin to our “property right” solution), the entrepreneur has an incentive to keep it hidden, forcing the second creditor to conduct due diligence or bear risk. This may cause credit rationing, while at the same time preventing excess lending. Like us, Ayotte and Bolton (2011) explicitly model a tri-lateral, sequential exchange environment, and find that a major cost of enforcing property rights is a reduction in trade. However, in their model the choice between the property right and personal right solutions solves a trade-off between two different ex post inefficiencies—that is, too little trade under property rights (no lending by the second creditor in a good state) and too much trade under personal rights (lending by the second creditor even in a bad state). In our model, instead, the key tradeoff is beween ex post and ex ante inefficiencies—namely, too little trade under property rights (T does not buy the asset from A, and the gain is not realized), and no separation of ownership and control under personal rights (P may not delegate control of the asset to A, in which case the gain from specialization is not realized). As discussed below, bringing the ex ante gains from specialization, and the owner’s endogenous decision to separate ownership and control, into a sequential exchange framework is important, because it allows us to explain property rights enforcement in a variety of nonfinancial property and company transactions that the model developed by Ayotte and Bolton (2011) cannot capture.

7. Conclusion

This article has studied property rights in a realistic market and institutional environment, where the acquirer of rights over an asset may not know whether the agent selling those rights has been authorized to do so by the owner, an essential element in productive specialization. In this setting, a key feature of property rights is that they can be enforced against subsequent acquirers, or in rem. This has been largely ignored in the economic literature by assuming that economic agents enjoy unlimited liability, and hence that the difference between property and personal rights is not a key aspect of enforcement.

We fill this gap by showing that in a setting where agents suffer from limited liability, if property rights are unconditionally enforced, impersonal exchange fails. The reason for such failure is that potential buyers of an asset anticipate collusion between its owner and the selling agent, and therefore do not buy—that is, hidden personal relationships may crowd out impersonal trade. In contrast, if property rights are not enforced (and hence impersonal buyers are fully protected), the fear of expropriation by opportunistic sellers may induce inefficient concentration of asset ownership and control, wasting specialization possibilities. In this case, personal ties between the asset’s owner and the selling agent will favor specialization and trade by protecting the owner from the agent’s opportunism. We show that to overcome this trade-off, property rights must be conditioned on explicit evidence of the owner’s consent to transfer the asset. In the absence of mechanisms for making the owner’s consent public, property rights should be conditioned on implicit evidence that the owner has voluntarily delegated control of the asset to the agent. The baseline trade-off we have identified is robust to different analytical specifications and extensions.

Our model thus provides a unified rationale for the institutional underpinnings of specialization and the separation of ownership and control—a central feature of market economies at least since the analysis of Adam Smith (1776). In particular, our model highlights how specialization is made possible by a panoply of complex and sometimes misunderstood institutions, such as adverse possession, the rules on good faith purchase, and property and company registries. Our model also provides an analytical framework that may be useful to adapt these institutions without hampering their fundamental market-preserving function.

An important force in our model is the personal relationship between the asset’s owner and seller, which may hamper or favor specialization and impersonal exchange depending on how property rights are enforced. We currently model this hidden personal relationship as exogenous, and thus independent of the gains from trade. In future work, we plan to endogenize personal relationships by embedding them in a relational contracting model (e.g. Baker et al. 2001; Levin 2003), or a community enforcement model (e.g. Milgrom et al. 1990; Greif et al. 1994), where their strength is shaped and limited by the potential future gains from impersonal trade. This extension will shed light on the complex interplay between personal relationships, impersonal exchange, and institutions, which the economic literature treats as independent.

Our parsimonious model could also be enriched to allow for multiple assets as well as multiple owners, agents and traders enjoying different specialization opportunities and suffering different degrees of asymmetric information caused by the more or less strict enforcement of property rights. This more general model could be used to study economic development and growth as a function of property rights institutions, as well as their distributive consequences. Although these extensions are outside the scope of the present article, we hope to pursue them in future research.

Acknowledgement

We thank the editor, two anonymous referees and Agustín Casas, Lisa Berstein, Pablo Casas-Arce, Oscar Contreras, Carlos Gómez-Ligüerre, Carmine Guerriero, Stephen Hansen, Daniel Herbold, Thomas Merrill, Jens Prüfer, Alan Schwartz, Henry Smith, Giuseppe Zanarone, and audiences at the ALEA and SIOE conferences, the Fourth Workshop on Relational Contracts, as well as George Mason University, Washington and Lee University, and HKU Faculty of Law for useful comments. This study received financial support from the Spanish Ministry of the Economy, Industry and Competitiveness through grant ECO2017-85763-R, and the Severo Ochoa Program for Centers of Excellence in R&D (SEV-2015-0563). Usual disclaimers apply.

Footnotes

1. In a different yet complementary paper, Kranton (1996) shows that the emergence of impersonal trade may also be discouraged by the existence of well-developed reciprocal exchange channels.

2. In the Appendix, we explore the case where principal P may value the asset more than the third party T.

3. Modeling of an alternative technology (such that P can contact T directly) would not change the trade-offs we identity. It would add a simple observation—that is, when transaction costs resulting from the agency problems we analyze are too burdensome, then P may prefer to bypass A and contact T directly. However, this is a very unrealistic possibility given the overwhelming preponderance of agency relations.

4. We assume that T pays upfront and receives the asset on the spot from A, who is in possession of the asset. In an alternative specification, empirically interesting but analytically equivalent, A may be a buyer and T a seller. That is, A may buy goods from T on credit, offering P’s asset as a guarantee of payment. For instance, in a company context, the asset may be the cash of P’s firm of which A is a manager.

5. We model a perfect court (there is no verifiability problem in our analysis). The consideration of partial indemnity claims might affect the incentives of P and A, but it would not eliminate the possibility of collusion, which is central to our model and is defined and discussed below.

6. The model’s results would continue to hold under the weaker assumption that T may observe the originative contract at a cost [for instance, by conducting a “due diligence” investigation, as in (Ayotte and Bolton 2011)].

7. Assuming the same relational liability for P and A simplifies the exposition but does not matter for the model’s results.

8. Opting for simplicity due to expositional reasons, we model implicit consent in a deterministic way. An alternative specification could introduce random provision of informal evidence (by means of a signal) and make the results derived in Proposition 5 conditional on additional thresholds.

9. The fixed cost f should be understood as a reduced form. For instance, besides the cost of setting up a registry, relying on a public registry may reduce anonymity and privacy.

10. This evidence (but not the Roman case) can also be explained by alternative theories. See, for instance, the discussion by Lueck and Miceli (2007: 226).

11. When there are no liability constraints, the efficient sanctions against expropriation may be stronger or weaker depending on the relative importance of promoting ex ante investment or ex post bargaining (e.g. Kaplow and Shavell 1996; Bar-Gill and Persico 2016; Guerriero 2016; Segal and Whinston 2016).

12. If A does not collude, he can choose between not selling the asset or selling the asset and keeping the price. If A does not sell the asset, he loses the relationship with P but pays no damages, so his payoff is . If A sells and keeps the price, he loses the relationship with P and in addition, he must pay damages once P repossesses the asset. Therefore, A’s payoff is . Since damages cannot exceed the price paid by T, A’s best deviation is clearly to sell and keep the price.

Appendix: Possible Extensions

Our parsimonious model is sufficient to generate a tradeoff that has broad relevance and can explain a variety of core economic institutions. At the same time, our framework is tractable and thus could be extended to explore how including additional forces in the model, or relaxing some of its assumptions, may affect the optimal enforcement of property rights. Although fully pursuing these extensions is beyond the scope of this article, we briefly discuss some of them in this section.

1. Partial damage liability

In a first extension, we relax our assumption on A’s limited liability by allowing A to have some damage liability toward both P and T, in addition to the “relational” liability toward P that is already allowed for in the baseline model.

High damage liability

It is easy to verify that if , A has no incentive to sell against P’s will. Moreover, P cannot collude with A in a property right regime because to induce A to prefer collusion over his best alternative option (i.e. breaking the relationship with P and not selling to T), P would have to promise an informal bonus of at least , which is higher than P’s relational liability and hence is not self-enforcing. At the same time, high damage liability ensures that both in the property right and in the personal right regime, P can extract the entire surplus from trade, , by authorizing A to sell and paying A a small formal bonus, . This implies that irrespective of the legal rule, P specializes and the gains from trade are realized—that is, the first best is achieved.

Suppose now that , and consider in turn the cases where P has a property right or a personal right over the asset.

Lower damage liability: P has a property right over the asset

If , condition (A1) does not hold and therefore the only equilibrium when P has a property right is the one with collusion and no trade, as in Section 3.2.

If and , there is a noncollusive equilibrium with trade if, and only if .

Finally, if and , there is a noncollusive equilibrium with trade if, and only if .

Lower damage liability: P has a personal right over the asset

The socially optimal legal rule

We are now ready to compare the property right and personal right rules on efficiency grounds. We separately consider the cases where or . The results are summarized in the following propositions, which follow directly from the analysis above.

Proposition A-1. Suppose . Then, (i) for , both the property right and the personal right rules are socially optimal and achieve the first best; (ii) for , the personal right rule is socially optimal and achieve the first best when condition (A2) holds, whereas the property right regime is socially optimal, but does not achieve the first best, when condition (A2) does not hold.

Proposition A-2. Suppose . Then, (i) for , both the property right and the personal right rules are socially optimal and achieve the first best; (ii) for , the personal right rule is socially optimal and achieves the first best, whereas the property right rule does not achieve the first best and hence is suboptimal; (iii) for , the personal right rule is socially optimal and achieves the first best when condition (A2) holds, whereas the property right regime is socially optimal, but does not achieve the first best, when condition (A2) does not hold.

In sum, allowing A to have positive but small enough damage liability delivers results that are qualitatively similar to those in the baseline model. At higher liability levels, both rules tend to become efficient, and therefore the region where efficiency can be improved by mechanisms like RSM becomes narrower. This is consistent with our discussion at the beginning of the article: when the value of assets and transactions is small enough, so that the personal wealth of individuals is sufficient to bond them, the interaction between sequential personal and impersonal contracts poses little risks to traders. Therefore, the distinction between rights in rem (property rights) and rights in personam (personal rights) loses significance, and of course, there is little need for complex institutions such as registries and other publicity mechanisms. However, property rights and publicity mechanisms become significant in a world of impersonal exchange, where personal wealth cannot bond the large economic transactions at stake.

2. Uncertain Gains from Trade

3. Imperfect Collusion

Finally, if , it is easy to check that there are two possible property right equilibria—one with collusion and no trade (as in Proposition 2), and one without collusion (as in Proposition 3).

Our baseline model, where , should therefore be seen as a normalization for the more general case where . We leave refinements of the multiple equilibria case () for future consideration.

4. Ex ante Investment in the Asset

In a final extension, P may have the opportunity to make a non-contractible, asset-specific investment ex ante, which would be discouraged in the absence of property rights because of A’s “holdup.” This extension would not alter the trade-offs and predictions in our model. However, adding ex ante specific investments to the model would strengthen the case for enforcing property rights, the case being more relevant when P’s productive investment is significant.

References

World Bank.