-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Naoko Igarashi, Maho Aoyama, Masaya Ito, Satomi Nakajima, Yukihiro Sakaguchi, Tatsuya Morita, Yasuo Shima, Mitsunori Miyashita, Comparison of two measures for Complicated Grief: Brief Grief Questionnaire (BGQ) and Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG), Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 51, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 252–257, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa185

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

No prior studies have used a single sample of bereaved families of cancer patients to compare multiple scales for assessing Complicated Grief. Here, we compare the two measures.

We sent a questionnaire to the bereaved families of cancer patients who had died at 71 palliative care units nationwide.

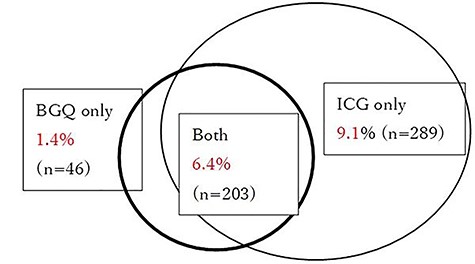

The analysis included 3173 returned questionnaires. Prevalence of Complicated Grief was 7.8% by Brief Grief Questionnaire (with a cutoff score of 8) and 15.5% for Inventory of Complicated Grief (with a cutoff score of 26). The Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the Brief Grief Questionnaire and the Inventory of Complicated Grief was 0.79, and a ceiling effect was seen for the distribution of the Brief Grief Questionnaire scores. Although 6.4% of respondents scored both 8 or higher on the Brief Grief Questionnaire and 26 or higher on the Inventory of Complicated Grief, only 1.4% scored both 8 or higher on the Brief Grief Questionnaire and <26 on the Inventory of Complicated Grief. In contrast, 9.1% scored <8 on the Brief Grief Questionnaire but 26 or higher on the Inventory of Complicated Grief.

The prevalence of Complicated Grief was estimated to be higher by the Inventory of Complicated Grief than by the Brief Grief Questionnaire in this sample. Patients with severe Complicated Grief might be difficult to discriminate their intensity of grief by the Brief Grief Questionnaire. Once the diagnostic criteria of Complicated Grief are established, further research, such as optimization of cutoff points and calculations of sensitivity and specificity, will be necessary.

Introduction

Grief reactions following the loss of a loved one are often associated with psychological and functional impairment (1). In most cases, the mourning process eventually leads to restored psychological equilibrium. Sometimes, however, the grief reaction becomes severe and prolonged. This has been referred to as ‘Complicated Grief’ (CG) or ‘Prolonged Grief Disorder’ (PGD), but the diagnostic criteria of CG or PGD is yet to be established and still controversy (2–4). Several screening measures of CG have been developed (5–8) and used in research. Previous studies have estimated the prevalence of CG among bereaved subjects to be 2–32% (9–12). This wide variation in reported prevalence is likely related to differences in cultural norms across the populations studied, decedents’ clinical courses and durations of bereavement.

Participant factors strongly affect the CG prevalence. In the previous studies, the prevalence of CG in general population was 0.9–9% (10–14), whereas among loved ones of cancer patients, it was higher, at 7.7–14% (15,16) Previous studies also reported that the prevalence of CG decreases with increasing time elapsed after the death (1,15).

Of note, however, is a striking difference in CG prevalence across two studies of groups of bereaved with similar family and decedent backgrounds. Both were surveys of bereaved families of cancer patients who died in palliative care units (PCU) in Japan (16,17). Sakaguchi et al. (17) used the Inventory of Traumatic Grief and found a CG prevalence of 2.4%. Aoyama et al. (16), on the other hand, used the Brief Grief Questionnaire (BGQ) and estimated that the prevalence of CG was 14%. Given the similarity of the study populations, this difference is attributed to differences in the screening scales and is thought to have arisen from either or both of two factors: different cutoff points and differences in the structure and content of the scales.

In addition, there have not been many studies comparing the outcomes of multiple CG screening measures on the same subjects, and no research has been conducted to compare different screening scales for CG on the same subjects for bereaved families of cancer patients.

The Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) is the most commonly employed worldwide. On the other hand, when conducting a large sample survey, it is more convenient to use the scale that is least burdensome to respondents. Thus the BGQ is attractive, as it includes only five items. It is therefore important to compare the performance of the BGQ to that of the dominant CG screening scale, the ICG. Thus, the purposes of this study is to describe the distributions of the BGQ and the ICG scores obtained from a single group of subjects that underwent both screening tests, compare the results of the two tests to one another and characterize each.

Patients and Methods

This study was part of a nationwide survey of bereaved family members of cancer patients that evaluated the quality of end-of-life care in Japan, the Japan Hospice and Palliative Care Evaluation Study 2016 (J-HOPE2016 Study). The J-HOPE2016 study was a self-reported questionnaire-based survey.

Participating institutions

We recruited from 169 inpatient PCUs that were members of Hospice Palliative Care Japan, of which 71 PCUs participated in the study.

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional, anonymous, self-reported questionnaire survey between May and July of 2016. We asked each institution to identify and list up to 80 bereaved family members of patients who had died before 31 January 2016. Inclusion criteria were: (i) the patient died of cancer, (ii) the patient was at least 20 years old and (iii) the bereaved family members were at least 20 years old. Exclusion criteria were: (i) the patient received palliative care for <3 days, (ii) the bereaved family member could not be identified, (iii) terminal treatment or death occurred in an intensive care unit, (iv) the potential participant experienced serious psychological distress as determined by a primary physician and a nurse and (v) the potential participant was incapable of completing the self-reported questionnaire because of cognitive impairment or visual disability. The questionnaire was sent to the bereaved family members from participating institutions along with a letter explaining the survey. The return of a completed questionnaire was considered consent to participate in the study. Participants were asked to return the completed questionnaire to the secretariat office (Tohoku University) within 1 month. We sent a reminder to non-responders 1 month after the questionnaire went out. If they did not wish to participate in the study, they were asked to check a ‘no participation’ box and return the incomplete questionnaire. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the institutional review boards of Tohoku University and all participating institutions. The approval number is 2016-1-015.

Questionnaire

We asked the participating institutions to collect the following data for each decedent: age, gender, duration of hospitalization immediately preceding death and primary cancer site.

Brief Grief Questionnaire

The BGQ was developed by Shear et al. (5,12,18), and the reliability and validity of the Japanese version have previously been confirmed. Although the BGQ was originally developed to assess CG in people who had lost a loved one to the September 11th World Trade Centre attacks, Ito et al. (12,18) employed the questionnaire among the general population of Japan for people who had lost a loved one and for bereaved family members of cancer patients. The BGQ consists of five items, each of which is scored from 0 to 2 (0 = not at all, 1 = somewhat, 2 = a lot). The BGQ total scores range from 0 to 10. A total score of 5 to 7 suggests that the respondent is likely to develop CG, and 8 or higher indicates that the respondent has CG.

Inventory of Complicated Grief

The ICG was developed by Prigerson et al. (6,19), and the reliability and validity of the Japanese version have previously been confirmed. The scale consists of 19 items. The respondent is asked to report the frequency (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always) with which they currently experience each of the emotional, cognitive and behavioural states described. Total scores range from 0 to 76, and a total score of 26 or higher suggest that the respondent is suffering from CG.

Patient Health Questionnaire 9

We used the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) to assess depressive symptoms. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version have previously been confirmed (20,21). The scale consists of nine items, each of which is scored from 0 to 3. Total scores for the PHQ-9 range from 0 to 27 and a total score of 10 or higher indicates at least moderate depression.

Overall care satisfaction

We asked participants about their overall satisfaction with the care that the patient had received at the place of death. The question used was, ‘Overall, were you satisfied with the medical care the patient received?’ Participants were asked to respond using a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = absolutely dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = somewhat dissatisfied, 4 = somewhat satisfied, 5 = satisfied and 6 = absolutely satisfied).

Participant characteristics

We asked the bereaved family members for details about their own age, sex, physical health, educational background and relationship with the patient, as well as about the presence of other care givers, frequency with which the respondent attended to the patient and social support.

Statistical analysis

First, we characterized the distributions of patient background, family background, the BGQ, the ICG and the PHQ-9. We then calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of the BGQ total score and the ICG total score and illustrated the ICG and the BGQ distribution overlap with a Venn diagram. We adopted the original cutoff point (7/8), which was developed in the USA for the Venn diagram. Finally, considering BGQ as a screening tool among Japanese bereaved family members of cancer, we examined the cutoff points that could cover participants identified as CG by ICG as gold standard. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4, Japanese version (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and JMP® 11 (SAS Institute Inc.). We considered a P value <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

The data analysis included 3173 returned questionnaires (for a response rate of 56%). Patient and caregiver characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age of patients was 75.3 ± 11.5 years (mean ± SD), 55% were male and 22% had lung cancer as the primary tumour, followed by 21% with tumours of the liver, bile duct or pancreas. The average length of stay was 38.8 ± 51.7 days. The average age of bereaved family members was 61.6 ± 12.1 years, 66% were female, 40% had been married to the deceased, and the average time elapsed between bereavement and survey completion was 284.5 ± 134.7 days.

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics . | . | . |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1741 | 55 |

| Female | 1432 | 45 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (75.3 ± 11.5) | |

| <60 years | 273 | 8 |

| 60–69 years | 647 | 20 |

| 70–79 years | 957 | 30 |

| ≥80 years | 1296 | 41 |

| Primary tumour site | ||

| Lung | 711 | 22 |

| Stomach, oesophagus | 450 | 14 |

| Colon, rectum | 432 | 14 |

| Liver, bile duct, pancreas | 667 | 21 |

| Breast | 132 | 4 |

| Prostate, kidney, bladder | 218 | 7 |

| Ovary, uterus | 135 | 4 |

| Other | 428 | 13 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) | (38.8 ± 51.7) | |

| <1 week | 269 | 8 |

| 1–2 weeks | 652 | 21 |

| 2–4 weeks | 876 | 28 |

| 4–8 weeks | 776 | 24 |

| 8–12 weeks | 291 | 9 |

| ≥12 weeks | 309 | 10 |

| Bereaved Family Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1036 | 33 |

| Female | 2084 | 66 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (61.6 ± 12.1) | |

| <60 years | 1280 | 40 |

| 60–69 years | 1021 | 33 |

| 70–79 years | 620 | 20 |

| ≥80 years | 196 | 6 |

| Relationship | ||

| Spouse | 1271 | 40 |

| Child | 1490 | 47 |

| Parent | 79 | 2 |

| Others | 289 | 9 |

| Duration of bereavement (mean ± SD) | (284.5 ± 134.7) | |

| <6 months | 701 | 22 |

| 6–12 mmonths | 1869 | 60 |

| 1–1.5 years | 443 | 14 |

| 1.5–2 years | 105 | 3 |

| ≥2 years | 55 | 2 |

| Overall care satisfaction | ||

| Absolutely dissatisfied | 148 | 5 |

| Dissatisfied | 42 | 1 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 126 | 4 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 438 | 14 |

| Satisfied | 1419 | 45 |

| Absolutely satisfied | 952 | 30 |

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics . | . | . |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1741 | 55 |

| Female | 1432 | 45 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (75.3 ± 11.5) | |

| <60 years | 273 | 8 |

| 60–69 years | 647 | 20 |

| 70–79 years | 957 | 30 |

| ≥80 years | 1296 | 41 |

| Primary tumour site | ||

| Lung | 711 | 22 |

| Stomach, oesophagus | 450 | 14 |

| Colon, rectum | 432 | 14 |

| Liver, bile duct, pancreas | 667 | 21 |

| Breast | 132 | 4 |

| Prostate, kidney, bladder | 218 | 7 |

| Ovary, uterus | 135 | 4 |

| Other | 428 | 13 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) | (38.8 ± 51.7) | |

| <1 week | 269 | 8 |

| 1–2 weeks | 652 | 21 |

| 2–4 weeks | 876 | 28 |

| 4–8 weeks | 776 | 24 |

| 8–12 weeks | 291 | 9 |

| ≥12 weeks | 309 | 10 |

| Bereaved Family Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1036 | 33 |

| Female | 2084 | 66 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (61.6 ± 12.1) | |

| <60 years | 1280 | 40 |

| 60–69 years | 1021 | 33 |

| 70–79 years | 620 | 20 |

| ≥80 years | 196 | 6 |

| Relationship | ||

| Spouse | 1271 | 40 |

| Child | 1490 | 47 |

| Parent | 79 | 2 |

| Others | 289 | 9 |

| Duration of bereavement (mean ± SD) | (284.5 ± 134.7) | |

| <6 months | 701 | 22 |

| 6–12 mmonths | 1869 | 60 |

| 1–1.5 years | 443 | 14 |

| 1.5–2 years | 105 | 3 |

| ≥2 years | 55 | 2 |

| Overall care satisfaction | ||

| Absolutely dissatisfied | 148 | 5 |

| Dissatisfied | 42 | 1 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 126 | 4 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 438 | 14 |

| Satisfied | 1419 | 45 |

| Absolutely satisfied | 952 | 30 |

SD, standard deviation.

Some items have missing values due to unanswered.

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics . | . | . |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1741 | 55 |

| Female | 1432 | 45 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (75.3 ± 11.5) | |

| <60 years | 273 | 8 |

| 60–69 years | 647 | 20 |

| 70–79 years | 957 | 30 |

| ≥80 years | 1296 | 41 |

| Primary tumour site | ||

| Lung | 711 | 22 |

| Stomach, oesophagus | 450 | 14 |

| Colon, rectum | 432 | 14 |

| Liver, bile duct, pancreas | 667 | 21 |

| Breast | 132 | 4 |

| Prostate, kidney, bladder | 218 | 7 |

| Ovary, uterus | 135 | 4 |

| Other | 428 | 13 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) | (38.8 ± 51.7) | |

| <1 week | 269 | 8 |

| 1–2 weeks | 652 | 21 |

| 2–4 weeks | 876 | 28 |

| 4–8 weeks | 776 | 24 |

| 8–12 weeks | 291 | 9 |

| ≥12 weeks | 309 | 10 |

| Bereaved Family Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1036 | 33 |

| Female | 2084 | 66 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (61.6 ± 12.1) | |

| <60 years | 1280 | 40 |

| 60–69 years | 1021 | 33 |

| 70–79 years | 620 | 20 |

| ≥80 years | 196 | 6 |

| Relationship | ||

| Spouse | 1271 | 40 |

| Child | 1490 | 47 |

| Parent | 79 | 2 |

| Others | 289 | 9 |

| Duration of bereavement (mean ± SD) | (284.5 ± 134.7) | |

| <6 months | 701 | 22 |

| 6–12 mmonths | 1869 | 60 |

| 1–1.5 years | 443 | 14 |

| 1.5–2 years | 105 | 3 |

| ≥2 years | 55 | 2 |

| Overall care satisfaction | ||

| Absolutely dissatisfied | 148 | 5 |

| Dissatisfied | 42 | 1 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 126 | 4 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 438 | 14 |

| Satisfied | 1419 | 45 |

| Absolutely satisfied | 952 | 30 |

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics . | . | . |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1741 | 55 |

| Female | 1432 | 45 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (75.3 ± 11.5) | |

| <60 years | 273 | 8 |

| 60–69 years | 647 | 20 |

| 70–79 years | 957 | 30 |

| ≥80 years | 1296 | 41 |

| Primary tumour site | ||

| Lung | 711 | 22 |

| Stomach, oesophagus | 450 | 14 |

| Colon, rectum | 432 | 14 |

| Liver, bile duct, pancreas | 667 | 21 |

| Breast | 132 | 4 |

| Prostate, kidney, bladder | 218 | 7 |

| Ovary, uterus | 135 | 4 |

| Other | 428 | 13 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) | (38.8 ± 51.7) | |

| <1 week | 269 | 8 |

| 1–2 weeks | 652 | 21 |

| 2–4 weeks | 876 | 28 |

| 4–8 weeks | 776 | 24 |

| 8–12 weeks | 291 | 9 |

| ≥12 weeks | 309 | 10 |

| Bereaved Family Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1036 | 33 |

| Female | 2084 | 66 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | (61.6 ± 12.1) | |

| <60 years | 1280 | 40 |

| 60–69 years | 1021 | 33 |

| 70–79 years | 620 | 20 |

| ≥80 years | 196 | 6 |

| Relationship | ||

| Spouse | 1271 | 40 |

| Child | 1490 | 47 |

| Parent | 79 | 2 |

| Others | 289 | 9 |

| Duration of bereavement (mean ± SD) | (284.5 ± 134.7) | |

| <6 months | 701 | 22 |

| 6–12 mmonths | 1869 | 60 |

| 1–1.5 years | 443 | 14 |

| 1.5–2 years | 105 | 3 |

| ≥2 years | 55 | 2 |

| Overall care satisfaction | ||

| Absolutely dissatisfied | 148 | 5 |

| Dissatisfied | 42 | 1 |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 126 | 4 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 438 | 14 |

| Satisfied | 1419 | 45 |

| Absolutely satisfied | 952 | 30 |

SD, standard deviation.

Some items have missing values due to unanswered.

The average of the BGQ total score was 3.8 ± 2.4, and the prevalence of CG was 7.8% by the BGQ (cutoff 7/8). The average of the ICG total score was 12.8 ± 12.5, and the prevalence of CG by the ICG was 15.5% (cutoff 25/26). The average PHQ-9 total score was 5.5 ± 5.6, and 21.7% of total scores achieved 10 or higher (Table 2).

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| BGQ total score (mean ± SD) | (3.8 ± 2.4) | |

| BGQ < 8 | 2925 | 92.2 |

| BGQ ≥ 8 | 248 | 7.8 |

| ICG total score(mean ± SD) | (12.8 ± 12.5) | |

| ICG < 26 | 2628 | 84.5 |

| ICG ≥ 26 | 491 | 15.5 |

| PHQ-9 total score(mean ± SD) | (5.5 ± 5.6) | |

| PHQ-9 < 10 | 2379 | 78.3 |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | 660 | 21.7 |

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| BGQ total score (mean ± SD) | (3.8 ± 2.4) | |

| BGQ < 8 | 2925 | 92.2 |

| BGQ ≥ 8 | 248 | 7.8 |

| ICG total score(mean ± SD) | (12.8 ± 12.5) | |

| ICG < 26 | 2628 | 84.5 |

| ICG ≥ 26 | 491 | 15.5 |

| PHQ-9 total score(mean ± SD) | (5.5 ± 5.6) | |

| PHQ-9 < 10 | 2379 | 78.3 |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | 660 | 21.7 |

BGQ, Brief Grief Questionnaire; ICG, Inventory of Complicated Grief; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; SD, standard deviation.

Some items have missing values due to unanswered.

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| BGQ total score (mean ± SD) | (3.8 ± 2.4) | |

| BGQ < 8 | 2925 | 92.2 |

| BGQ ≥ 8 | 248 | 7.8 |

| ICG total score(mean ± SD) | (12.8 ± 12.5) | |

| ICG < 26 | 2628 | 84.5 |

| ICG ≥ 26 | 491 | 15.5 |

| PHQ-9 total score(mean ± SD) | (5.5 ± 5.6) | |

| PHQ-9 < 10 | 2379 | 78.3 |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | 660 | 21.7 |

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| BGQ total score (mean ± SD) | (3.8 ± 2.4) | |

| BGQ < 8 | 2925 | 92.2 |

| BGQ ≥ 8 | 248 | 7.8 |

| ICG total score(mean ± SD) | (12.8 ± 12.5) | |

| ICG < 26 | 2628 | 84.5 |

| ICG ≥ 26 | 491 | 15.5 |

| PHQ-9 total score(mean ± SD) | (5.5 ± 5.6) | |

| PHQ-9 < 10 | 2379 | 78.3 |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | 660 | 21.7 |

BGQ, Brief Grief Questionnaire; ICG, Inventory of Complicated Grief; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; SD, standard deviation.

Some items have missing values due to unanswered.

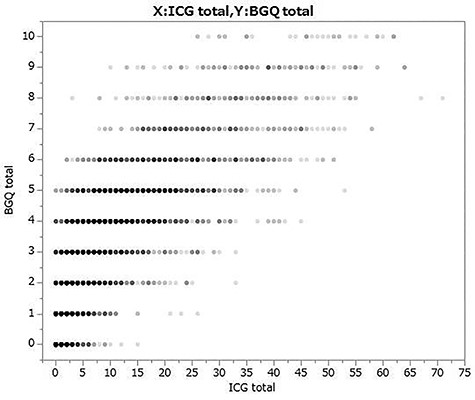

A scatter diagram of the BGQ total score versus the ICG total score is shown in Fig. 1. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was 0.79 (p < 0.0001). The overlap between the ICG and the BGQ using the cutoff developed in the USA is shown in Fig. 2. Six per cent of respondents achieved total scores of at least 8 points on the BGQ and at least 26 points on the ICG. Only 1% of those who scored 8 or higher on the BGQ scored <26 on the ICG, but 9% of those who scored 26 or higher on the ICG scored <8 on the BGQ.

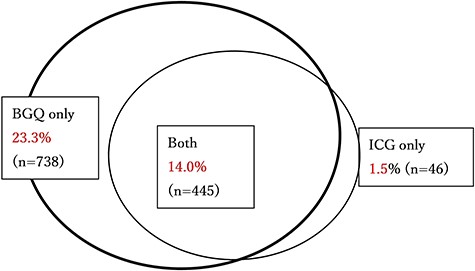

The cutoff point for the BGQ, which can cover participants who were identified as CG by the ICG, was 4 of 5. Fourteen per cent of respondents achieved total scores of at least 5 points on the BGQ and at least 26 points on the ICG. Twenty-three per cent of those who scored 5 or higher on the BGQ scored <26 on the ICG, then 1% of those who scored 26 or higher on the ICG scored <5 on the BGQ (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This is the first study to compare the results of the BGQ and the ICG administered to a single group of bereaved family members of cancer patients as screening measures for CG. We found that (i) the prevalence of CG was estimated to be 7.8% by the BGQ and 15.5% by the ICG; (ii) celling effect was observed in the BGQ, therefore discriminating the intensity among individuals who suffer from severe grief could be difficult and (iii) original cut point of BGQ (7/8) may underestimate the percentage of individuals who may have CG, and cut point of 4/5 might be better adopted when screening CG among Japanese bereaved family members of cancer.

When Fujisawa et al. (12) studied CG using the BGQ for bereaved subjects from the general population, they found a prevalence of 2.4%, but for 60% of their subjects, 3–10 years had elapsed since bereavement. In our study, the majority was within a year of bereavement. It is clear from previous studies that (i) longer durations of bereavement are associated with lower prevalence of CG (11)and (ii) cancer as the cause of death is an additional risk factor for CG (15). It is therefore unsurprising that the prevalence of CG in this study, as measured by the BGQ, was higher than that found by Fujisawa et al. (12) In addition, this is the first study in Japan to use the ICG for evaluating CG in bereaved family members of cancer patients. In their study using the ICG, Allen et al. (22) reported a prevalence of CG among bereaved families of 18.5%, which is very similar to our finding of 15.5%. Because the survey differs across countries and among participants, we cannot simply compare the prevalence of CG. However, from the results of this research and previous studies, the prevalence of CG determined by the BGQ cut-off point (7/8) tends to be smaller than the ICG.

The shape of the distributions of scores as plotted on a scatter diagram of the BGQ versus the ICG demonstrates a ceiling effect for the BGQ: an elliptical distribution with a rightward-upward slop is constrained by the upper end of the vertical (the BGQ) axis. This suggests that the BGQ is not adequately capturing the upper extent of grief experiences as compared with the ICG, and the BGQ may therefore be unsuitable for resolving gradations of severe CG. Comparing the ICG and the BGQ, the ICG also covers the small detailed items of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) (2), which is another reason that the ICG is better suited to discriminate among severities of CG.

Our results suggest that the BGQ should be interpreted with caution, as it tends to underestimate the prevalence of CG compared with the ICG. We also found that the BGQ had a ceiling effect, so it may be difficult to discriminate the intensity of grief among patients with severe CG. When the ICG (cutoff 25/26) is regarded as the gold standard, setting the BGQ cutoff point to 4/5 can cover patients identified as CG by the ICG as CG. However, the ICG is uncertain as a gold standard because the CG diagnostic criteria have not been established, and the ICG cutoff point has not been investigated for Japanese people. Furthermore, it will be necessary to identify optimal cutoff points for these tests when used for the bereaved of cancer patients in Japan. Finally, further study is needed on the relationship between CG and depression and how these are measured by different tests in different populations and cultures, as some of our results tended to contradict those of past studies, particularly with regard to PHQ-9 and the BGQ.

Scatter plot (x: BGQ total score, y: ICG total score). BGQ, Brief Grief Questionnaire; ICG, Inventory of Complicated Grief.

Venn diagram showing overlap of two screening measures for Complicated Grief (BGQ cutoff 7/8). BGQ, Brief Grief Questionnaire; ICG, Inventory of Complicated Grief.

Venn diagram showing overlap of two screening measures for Complicated Grief (BGQ cutoff 4/5). BGQ, Brief Grief Questionnaire; ICG, Inventory of Complicated Grief.

Limitation

We have identified three limitations of this investigation. First, we could not calculate or compare sensitivities and specificities of the two scales, because definite diagnostic criteria for CG have not been established. Second, bereaved family members experiencing especially severe grief may not have participated in this study. The response rate of this study is not low (63%), but such under-sampling of a severely affected segment of the population could still cause bias. Finally, the subject sample for this research may not be representative of the general population. Subjects of this study are bereaved family members of cancer patients who died at the member institutions of the Japan Hospice Palliative Care Association. Given that cancer deaths at these institutions comprise only ~8.4% of all cancer deaths in Japan, we cannot definitively state that the cancer deaths and bereaved families sampled for this study are representative of all cancer deaths and bereaved families throughout Japan. Given that ~3000 bereaved families participated; however, we feel confident that the sample was sufficiently large and representative to contribute important insights regarding CG among family members of cancer patients who received palliative care in Japan.

Conclusion

This study is the first to compare the performances of the BGQ and the ICG administered to bereaved family members of cancer patients. We found that (i) the estimated prevalence of Complicated Grief was 7.8% by the BGQ and 15.5% by the ICG, (ii) celling effect was observed in the BGQ, therefore discriminating the intensity among individuals who suffer from severe grief could be difficult and (iii) original cut point of BGQ (7/8) may underestimate the percentage of individuals who may have CG, and cut point of 4/5 might be better adopted when screening CG among Japanese bereaved family members of cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with the cooperation of Hospice Palliative Care Japan. The authors would like to thank all participants and participating institutions for taking part in this study. This work was supported by Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research number 15KK0326.