-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tatsuo Akechi, Kanae Momino, Fujika Katsuki, Hiroko Yamashita, Hiroshi Sugiura, Nobuyasu Yoshimoto, Yumi Wanifuchi-Endo, Tatsuya Toyama, Brief collaborative care intervention to reduce perceived unmet needs in highly distressed breast cancer patients: randomized controlled trial, Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 51, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 244–251, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa166

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Our newly developed brief collaborative care intervention program has been suggested to be effective in reducing breast cancer patients’ unmet needs and psychological distress; however, there has been no controlled trial to investigate its effectiveness. The purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of the program in relation to patients’ perceived needs and other relevant outcomes for patients including quality of life, psychological distress and fear of recurrence (Clinical trial register; UMIN-CTR, Clinical registration number; R5172).

Fifty-nine highly distressed breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy were randomly assigned either to a treatment as usual group or to a collaborative care intervention, consisting of four sessions that mainly included assessment of the patients’ perceived needs, learning skills of problem-solving treatment for coping with unmet needs and psycho-education provided by trained nurses supervised by a psycho-oncologist.

Although >80% of the eligible patients agreed to participate, and >90% of participants completed the intervention, there were no significant differences with regard to patients’ needs, quality of life, psychological distress and fear of recurrence, both at 1 and 3 months after intervention.

Newly developed brief collaborative care intervention program was found to be feasible and acceptable. The trial, however, failed to show the effectiveness of the program on patients’ relevant subjective outcomes. Further intervention program having both brevity and sufficient intensity should be developed in future studies.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers among women worldwide. In Japan, it is the most common cancer among women, with its incidence increasing continually. At present, >90 000 women are diagnosed with breast cancer annually in Japan. The psychosocial impact of breast cancer has received a good deal of attention because of its high prevalence and the severe psychosocial effects of both the cancer and its treatment. For example, previous studies have suggested that ~20–40% of breast cancer patients suffer from psychiatric morbidity, including depression and/or anxiety (1–4). In addition, our previous study demonstrated that the most common unmet needs experienced by ambulatory breast cancer patients are psychological, such as fears of cancer spread and anxiety, and that more than half of the patients experience these unmet needs (5).

Since the previous studies suggest that just screening of patients’ unmet needs cannot contribute to improve patients’ psychosocial well-being and care needs in patients with cancer (6), we have developed several types of intervention strategy for improving the quality of life (QoL) and alleviating the psychological distress of cancer patients, including a multifaceted psychosocial intervention program (7), a pharmacological treatment algorithm (8) and a nurse-assisted screening and psychiatric referral program (9). Based on these experiences, we have developed a brief collaborative care program that focuses on patients’ individual needs.

Focusing on patients’ needs offers a number of advantages. In particular, for patients, their perceived needs are as important as other outcomes such as QoL and psychological distress, even though their problems and symptoms do not necessarily reflect the actual need for help (5). Our previous study suggested that compared to other programs, an intervention program focusing on the needs of highly distressed patients, which is provided by nurses and supervised by trained psycho-oncologists, is more feasible, acceptable and satisfying to individual patients. For example, our preliminary study demonstrated that ~70% of eligible patients had participated in and >90% of them had completed our newly developed program (10). In contrast, although group psychotherapy, one of the most common psychosocial interventions for breast cancer patients, has proven to be effective in enhancing their QoL and reducing psychological distress, a previous study indicated that the rate of participation in the program was generally <50% (11). Our newly developed brief collaborative care program has been suggested to be effective in reducing breast cancer patients’ unmet needs and psychological distress; however, there is no controlled trial to investigate its effectiveness (10).

This study examined the effectiveness of our newly developed brief collaborative care intervention program on patients’ perceived needs and other relevant outcomes, such as QoL, psychological distress and fear of recurrence.

Patients and methods

Participants

Patients were recruited from October 2010 to March 2013. We aimed to include disease-free, but highly distressed breast cancer patients, at least 3 months after surgery because such subjects can have more unmet needs (5). The study participants were ambulatory female breast cancer patients attending the outpatient clinic for Oncology, Immunology and Surgery at Nagoya City University Hospital. Potential participants were consecutively sampled.

The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study were as follows: (i) diagnosis of breast cancer, (ii) aged 20 years or older, (iii) awareness of the cancer diagnosis, (iv) 3–6 months after breast surgery, (v) currently disease-free, (vi) not currently following up and getting treated in a psychiatry department and/or by any other mental health professionals, (7) suffering from psychological distress (a positive result of screening using the distress and impact thermometer; namely four points or more on the distress thermometer and/or three points or more on the impact thermometer [This implies that patients were suffering from clinical anxiety and/or depression] (12)) and (8) a general condition sufficient to participate in the intervention (0–2 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] performance status). The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with (i) cognitive impairment (e.g. dementia, delirium) and (ii) an inability to understand Japanese.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences (No. 467), Japan and was conducted in accordance with the principles laid down in the Helsinki Declaration. Written consent was obtained from each patient after thoroughly explaining the purpose and method of the study.

Study design

The design of the present study was an individually randomized, parallel-group trial. An independent statistician provided computer-generated random allocation sequences. Allocation sequences were maintained centrally and communicated to a study assistant who did not know the enrolled patients. Participants were randomized to collaborative care plus treatment as usual (TAU) or TAU alone.

Procedures

All participants received usual care. Patients in the intervention group also received four sessions over the course of ~3 months, provided by trained nurses, as shown in Table 1. The intervention program mainly included assessment of the patients’ perceived needs, learning skills of problem-solving treatment (PST) for coping with patients’ needs, psycho-education provided by a booklet including useful information on self-care for the adverse events of anti-cancer treatment, the psychological impact of cancer and its treatment and the available social resources, as well as behavioural activation using activity scheduling. PST and behavioural activation program for cancer patients was developed in our previous study (13, 14) and a modified, condensed version of the program was used in the current study. With regard to behavioural activation, patients were encouraged to complete an activity scheduling sheet and recommended to engage in pleasurable activities on a more frequent basis (15). Two trained nurses provided the intervention; one had previous experience of psychiatry and PST, while the other had no experience of psychiatry and PST (but had the experience of oncology) and was trained by trained psycho-oncologists to deliver the intervention, in particular, PST, using role-playing. In principle, the first two sessions were reviewed and supervised by a trained psycho-oncologist and the remaining two sessions were supervised as needed.

| Session . | Style . | Time . | Components . | Description . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview during a hospital visit | 90 min | Introduction Psycho-education Patients’ perceived needs Problem-solving treatment Behavioural activation Supervision | Explanation of the purpose and methods of intervention and establishment of a confidential relationship Provision of useful information, including self-care for the adverse events of anti-cancer treatment, the psychological impact of cancer and its treatment, and available social resources, using a booklet Recognizing patients’ perceived needs by reviewing SCNS-SF34 Introducing the purpose and methods of problem-solving treatment, identifying patients’ problems and setting goal using a worksheet Introducing activity scheduling and encouraging behavioural activation The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist |

| 2 | Interview during a hospital visit | 60 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Brainstorming strategies for the resolution of problems and concrete plans for their resolution The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 3 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 4 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Termination Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment Reviewing the previous sessions and managing termination anxiety as needed The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| Session . | Style . | Time . | Components . | Description . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview during a hospital visit | 90 min | Introduction Psycho-education Patients’ perceived needs Problem-solving treatment Behavioural activation Supervision | Explanation of the purpose and methods of intervention and establishment of a confidential relationship Provision of useful information, including self-care for the adverse events of anti-cancer treatment, the psychological impact of cancer and its treatment, and available social resources, using a booklet Recognizing patients’ perceived needs by reviewing SCNS-SF34 Introducing the purpose and methods of problem-solving treatment, identifying patients’ problems and setting goal using a worksheet Introducing activity scheduling and encouraging behavioural activation The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist |

| 2 | Interview during a hospital visit | 60 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Brainstorming strategies for the resolution of problems and concrete plans for their resolution The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 3 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 4 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Termination Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment Reviewing the previous sessions and managing termination anxiety as needed The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

SCNS-SF34, the short-form supportive care needs survey questionnaire; A/N, as needed.

| Session . | Style . | Time . | Components . | Description . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview during a hospital visit | 90 min | Introduction Psycho-education Patients’ perceived needs Problem-solving treatment Behavioural activation Supervision | Explanation of the purpose and methods of intervention and establishment of a confidential relationship Provision of useful information, including self-care for the adverse events of anti-cancer treatment, the psychological impact of cancer and its treatment, and available social resources, using a booklet Recognizing patients’ perceived needs by reviewing SCNS-SF34 Introducing the purpose and methods of problem-solving treatment, identifying patients’ problems and setting goal using a worksheet Introducing activity scheduling and encouraging behavioural activation The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist |

| 2 | Interview during a hospital visit | 60 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Brainstorming strategies for the resolution of problems and concrete plans for their resolution The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 3 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 4 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Termination Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment Reviewing the previous sessions and managing termination anxiety as needed The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| Session . | Style . | Time . | Components . | Description . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview during a hospital visit | 90 min | Introduction Psycho-education Patients’ perceived needs Problem-solving treatment Behavioural activation Supervision | Explanation of the purpose and methods of intervention and establishment of a confidential relationship Provision of useful information, including self-care for the adverse events of anti-cancer treatment, the psychological impact of cancer and its treatment, and available social resources, using a booklet Recognizing patients’ perceived needs by reviewing SCNS-SF34 Introducing the purpose and methods of problem-solving treatment, identifying patients’ problems and setting goal using a worksheet Introducing activity scheduling and encouraging behavioural activation The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist |

| 2 | Interview during a hospital visit | 60 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Brainstorming strategies for the resolution of problems and concrete plans for their resolution The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 3 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

| 4 | Tel. interview | 30 min | Problem-solving treatment Termination Supervision (A/N) | Continue to learn and master problem-solving treatment Reviewing the previous sessions and managing termination anxiety as needed The session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist as needed |

SCNS-SF34, the short-form supportive care needs survey questionnaire; A/N, as needed.

Outcome measures

The participants were assessed 1 and 3 months after the intervention. Those who dropped out of the intervention were asked to complete the assessments.

The primary outcome was the total score of patients’ perceived needs 1 month after intervention, as assessed by the Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire (SCNS-SF34) (16). Secondary outcomes included QoL, psychological distress and fear of recurrence 1 month after intervention. All measures were also assessed as secondary outcomes 3 months after the intervention.

Patients perceived needs: Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire

SCNS-SF34 is a self-administered instrument for assessing the perceived needs of cancer patients (17). SCNS-SF34 consists of 34 items covering five domains of need: psychological (10 items), health system and information (11 items), physical and daily living (5 items), patient care and support (5 items) and sexuality (3 items). Respondents were asked to indicate the level of their need for help over the last month in relation to their having cancer using the following five response options: (i) (No Need [Not applicable]), (ii) (No Need [Satisfied]), (iii) (Low Need), (iv) (Moderate Need), (v) (High Need). Subscale scores were obtained by summing the individual items, and the total score was obtained by summing all the subscales (range, 34–170). A higher score indicated a higher perceived need. The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of SCNS-SF34 have been established (16).

QoL: The European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30

Patient QoL was assessed using European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 (18). QLQ-C30 is a 30-item, self-report questionnaire covering functional (Global Health Status, Physical Functioning, Role Functioning, Emotional Functioning, Cognitive Functioning, Social Functioning) and symptom-related aspects (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea, financial difficulties) of QoL in cancer patients (18). The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of EORTC QLQ-C30 have been confirmed (19). A high functional score represents a high QoL. A high symptom score indicates severe symptoms.

Psychological distress: the Profile of Mood States scale

Profile of Mood States (POMS) is a self-rating scale measuring six emotional states (tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, vigor, fatigue and confusion) and total mood disturbance, which is the sum of the emotional state subscales (20). POMS is a widely used, reliable measure of emotional distress that has been validated in cancer patients and demonstrated to be reliable for the Japanese people (21). The possible scores for each subscale are tension-anxiety, 0–36; depression-dejection, 0–60; anger-hostility, 0–48; vigor, 0–32; fatigue, 0–28; confusion, 0–28; total mood disturbance, −32–200. (A total mood disturbance score is obtained by summing the subscale scores [with vigor weighted negatively] on the six primary mood factors.) A higher score indicates greater emotional distress, except for the vigor subscale.

Fear of recurrence: Japanese version of the Concerns about Recurrence Scale (CARS-J)

Japanese version of the Concerns about Recurrence Scale (CARS-J) is a 26-item self-report scale, originally developed in the USA (22). The reliability and validity of CARS-J have been confirmed among Japanese breast cancer patients, although the factor structure is slightly different from the original study, suggesting some cross-cultural differences with regard to the construct validity of fear of recurrence (23). CARS-J assesses the overall fear of breast cancer recurrence and four domains of specific fear of recurrence. Overall fear consists of four items: questions on frequency, potential for upset, consistency and intensity of fear. Although CARS-J has other four domains (Health and Death Worries; Womanhood Worries; Self-valued Worries; and Role Worries), the overall fear score was used. The range of possible scores for overall fear is 1–24, and a higher score indicates greater fear of recurrence.

Sociodemographic and biomedical factors

An ad hoc self-administered questionnaire was used to obtain information on the patients’ sociodemographic statuses, including their marital status, level of education and employment status. Their performance status, as defined by ECOG, was evaluated by the attending physicians. All other medical information (duration since diagnosis, clinical stage and anti-cancer treatment) was obtained from the patients’ medical records.

Sample size

Sample size was based on a power analysis conducted for the total score on SCNS-SF34. Effect size was estimated from our previous preliminary study on the effectiveness of collaborative care intervention on patients’ needs and distress (24). Based on our pilot test, we estimated that the mean reductions (standard deviation) of the total SCNS-SF34 score for the intervention group and TAU group would be 17 (18) and 3 (18) points, respectively, resulting in an effect size of 0.78. With 0.8 power to detect a significant difference at P = 0.05 (two-sided), it was calculated that 26 participants would be required for each arm. Thus, allowing for a 10% dropout rate (this estimate was also based on our pilot study), 30 patients would need to be recruited in each group.

| Characteristic . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual (n = 31) . | Treatment as usual (n = 28) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 52 (12) | 56 (13) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| ≤High school >Some college or university | 19 (61) 12 (39) | 19 (68) 9 (32) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Full-time Part-time Unemployed | 6 (19) 4 (13) 21 (68) | 5 (18) 4 (14) 19 (68) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married Divorced or widowed Single | 23 (74) 5 (16) 3 (10) | 24 (86) 4 (14) 0 (0) |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | ||

| I II | 18 (58) 13 (42) | 12 (43) 16 (57) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||

| Mastectomy Partial mastectomy | 5 (16) 26 (84) | 9 (32) 19 (68) |

| Lymphnode resection, n (%) | ||

| Presence Absence | 7 (23) 24 (67) | 6 (21) 22 (79) |

| Anticancer treatmenta, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy Trastuzumab Hormonal therapy | 17 (55) 5 (16) 23 (74) | 15 (54) 3 (10) 18 (64) |

| Distress and Impact thermometer | ||

| Distress, mean (SD) Impact, mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.1) 4.7 (2.1) | 5.2 (2.1) 4.5 (2.1) |

| Performance statusb, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 31 (100) | 28 (100) |

| Characteristic . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual (n = 31) . | Treatment as usual (n = 28) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 52 (12) | 56 (13) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| ≤High school >Some college or university | 19 (61) 12 (39) | 19 (68) 9 (32) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Full-time Part-time Unemployed | 6 (19) 4 (13) 21 (68) | 5 (18) 4 (14) 19 (68) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married Divorced or widowed Single | 23 (74) 5 (16) 3 (10) | 24 (86) 4 (14) 0 (0) |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | ||

| I II | 18 (58) 13 (42) | 12 (43) 16 (57) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||

| Mastectomy Partial mastectomy | 5 (16) 26 (84) | 9 (32) 19 (68) |

| Lymphnode resection, n (%) | ||

| Presence Absence | 7 (23) 24 (67) | 6 (21) 22 (79) |

| Anticancer treatmenta, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy Trastuzumab Hormonal therapy | 17 (55) 5 (16) 23 (74) | 15 (54) 3 (10) 18 (64) |

| Distress and Impact thermometer | ||

| Distress, mean (SD) Impact, mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.1) 4.7 (2.1) | 5.2 (2.1) 4.5 (2.1) |

| Performance statusb, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 31 (100) | 28 (100) |

SD, standard deviation

aMultiple choice.

bEastern Cooperative Oncology Group criteria.

| Characteristic . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual (n = 31) . | Treatment as usual (n = 28) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 52 (12) | 56 (13) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| ≤High school >Some college or university | 19 (61) 12 (39) | 19 (68) 9 (32) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Full-time Part-time Unemployed | 6 (19) 4 (13) 21 (68) | 5 (18) 4 (14) 19 (68) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married Divorced or widowed Single | 23 (74) 5 (16) 3 (10) | 24 (86) 4 (14) 0 (0) |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | ||

| I II | 18 (58) 13 (42) | 12 (43) 16 (57) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||

| Mastectomy Partial mastectomy | 5 (16) 26 (84) | 9 (32) 19 (68) |

| Lymphnode resection, n (%) | ||

| Presence Absence | 7 (23) 24 (67) | 6 (21) 22 (79) |

| Anticancer treatmenta, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy Trastuzumab Hormonal therapy | 17 (55) 5 (16) 23 (74) | 15 (54) 3 (10) 18 (64) |

| Distress and Impact thermometer | ||

| Distress, mean (SD) Impact, mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.1) 4.7 (2.1) | 5.2 (2.1) 4.5 (2.1) |

| Performance statusb, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 31 (100) | 28 (100) |

| Characteristic . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual (n = 31) . | Treatment as usual (n = 28) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 52 (12) | 56 (13) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| ≤High school >Some college or university | 19 (61) 12 (39) | 19 (68) 9 (32) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Full-time Part-time Unemployed | 6 (19) 4 (13) 21 (68) | 5 (18) 4 (14) 19 (68) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married Divorced or widowed Single | 23 (74) 5 (16) 3 (10) | 24 (86) 4 (14) 0 (0) |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | ||

| I II | 18 (58) 13 (42) | 12 (43) 16 (57) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||

| Mastectomy Partial mastectomy | 5 (16) 26 (84) | 9 (32) 19 (68) |

| Lymphnode resection, n (%) | ||

| Presence Absence | 7 (23) 24 (67) | 6 (21) 22 (79) |

| Anticancer treatmenta, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy Trastuzumab Hormonal therapy | 17 (55) 5 (16) 23 (74) | 15 (54) 3 (10) 18 (64) |

| Distress and Impact thermometer | ||

| Distress, mean (SD) Impact, mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.1) 4.7 (2.1) | 5.2 (2.1) 4.5 (2.1) |

| Performance statusb, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 31 (100) | 28 (100) |

SD, standard deviation

aMultiple choice.

bEastern Cooperative Oncology Group criteria.

Analysis

All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat model. The analysis of covariance was used to test group effects while controlling for the baseline scores. No statistical tests were planned to detect a difference at baseline between the two arms because we aimed to avoid multiple tests, and the decision to adjust for baseline in randomized controlled trials should not be determined by whether baseline differences are statistically significant (25). However, when clinically important differences at baseline were noted from a clinician’s perspective, sensitivity analyses were performed by adjusting for all such possible confounds.

A P value of <0.05 was regarded as being statistically significant, and all reported P values were two-tailed. All statistical procedures were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 16 software for Windows (IBM SPSS Inc., 2010).

Results

Enrolment and participants’ baseline characteristics

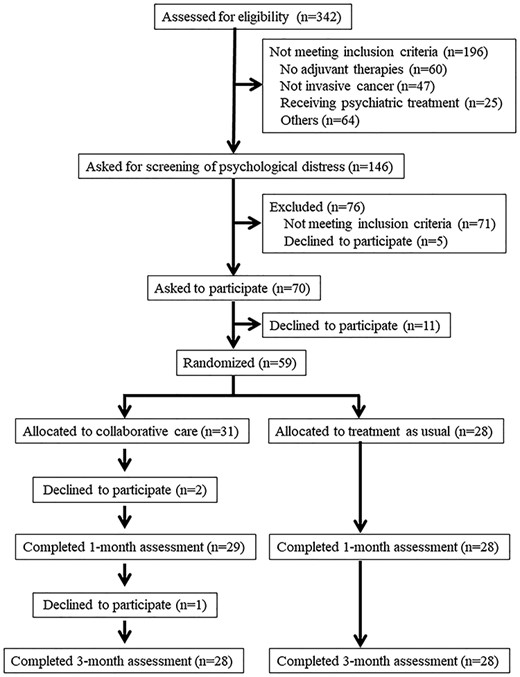

Three hundred and forty-two patients were assessed for potential eligibility, of which 146 were invited to be screened for their distress (Fig. 1). Among these, 59 participants were randomized, of which 31 and 28 participants were randomly assigned to the collaborative care and TAU groups, respectively (Fig. 1). Table 2 summarizes the sociodemographic and clinical factors at baseline. A possible clinically significant difference at baseline was found only for age.

Attrition

Among the eligible patients, 84% agreed to participate. Among the participants who were randomized to the collaborative care group, two patients discontinued the intervention after reporting that they suffered from physical symptoms due to chemotherapy (Fig. 1), and one further patient declined to participate after finishing the intervention. Thus, 29 of 31 patients in the intervention group completed the 1-month assessment (primary endpoint), and 28 of them completed the 3-month assessment (secondary endpoint). All 28 participants in the TAU group completed both endpoints (Fig. 1). Thus, 90% of the participants completed the study.

Patients’ perceived needs, emotional distress and fear of recurrence at 1 and 3 monthsa

| . | 1 month . | 3 months . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . |

| Patients’ needsb, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total needs Psychological Health system and information Physical and daily living Patient care and support Sexuality | 76.1 (27.3) 24.1 (9.4) 26.0 (10.7) 10.4 (4.0) 10.8 (4.3) 4.7 (2.9) | 84.0 (30.6) 26.3 (10.0) 30.5 (14.6) 11.5 (4.0) 11.6 (5.5) 4.2 (2.2) | 0.09 0.14 0.61 0.16 0.05 0.02 | 0.77 0.72 0.44 0.69 0.82 0.90 | 73.6 (29.3) 22.7 (9.4) 25.3 (12.5) 9.5 (3.6) 11.1 (5.1) 4.3 (2.3) | 79.1 (30.5) 24.8 (10.7) 28.9 (14.0) 10.3 (4.0) 10.8 (5.0) 4.3 (2.0) | 0.00 0.05 0.14 0.11 0.51 1.21 | 0.99 0.83 0.71 0.75 0.48 0.28 |

| Quality of lifec, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Global health status Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Fatigue Nausea and vomiting Pain Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhoea Financial difficulties | 53.7 (20.7) 85.5 (14.0) 78.7 (17.2) 71.6 (23.3) 67.8 (25.2) 82.8 (15.1) 40.2 (23.1) 0.6 (3.1) 26.4 (20.7) 16.1 (19.1) 25.3 (27.7) 12.6 (18.7) 24.1 (28.0) 8.0 (14.5) 26.4 (24.2) | 62.5 (19.2) 82.6 (10.8) 72.6 (20.4) 71.1 (19.1) 64.3 (24.7) 81.0 (18.5) 41.7 (21.1) 1.2 (4.4) 28.6 (19.2) 17.9 (21.2) 28.6 (28.3) 13.1 (22.8) 26.2 (30.6) 14.3 (21.1) 26.2 (21.0) | 4.29 0.18 0.51 1.68 0.07 0.71 0.60 0.44 0.002 0.03 0.01 0.06 0.18 1.93 0.42 | 0.04 0.68 0.48 0.20 0.80 0.40 0.44 0.51 0.97 0.87 0.93 0.80 0.67 0.17 0.52 | 57.7 (22.4) 85.0 (15.8) 85.0 (15.8) 76.2 (18.7) 72.6 (19.4) 86.3 (13.6) 33.3 (21.2) 3.0 (7.9) 22.0 (19.3) 15.5 (19.2) 32.1 (29.4) 8.3 (17.3) 23.8 (25.4) 11.9 (20.7) 21.4 (18.6) | 65.2 (20.2) 86.0 (9.0) 86.0 (9.0) 75.6 (19.8) 66.7 (24.0) 81.5 (16.6) 41.3 (21.4) 3.0 (7.9) 23.2 (18.3) 17.9 (19.2) 27.4 (27.3) 15.9 (10.7) 21.4 (31.7) 13.1 (21.0) 20.2 (24.6) | 2.57 1.04 0.77 0.58 1.29 2.10 0.87 0.01 0.21 0.00 2.25 0.70 0.07 0.06 0.69 | 0.12 0.31 0.39 0.45 0.26 0.15 0.36 0.91 0.65 0.99 0.14 0.41 0.80 0.81 0.41 |

| Emotional distressd, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total mood disturbance Tension-anxiety Depression-dejection Anger-hostility Vigor Fatigue Confusion | 41.1 (38.6) 10.0 (6.8) 11.9 (12.1) 7.5 (7.6) 8.4 (5.1) 9.7 (7.1) 9.8 (5.7) | 44.9 (40.0) 11.5 (7.5) 13.8 (12.3) 9.1 (8.4) 8.3 (4.6) 9.0 (6.8) 9.7 (5.5) | 0.17 0.39 0.21 0.65 0.003 0.02 0.03 | 0.68 0.54 0.65 0.43 0.96 0.88 0.87 | 34.1 (35.8) 9.1 (7.2) 10.2 (9.5) 6.4 (8.3) 8.7 (5.0) 8.1 (6.6) 9.0 (4.8) | 38.8 (38.8) 10.3 (7.2) 11.7 (11.7) 8.3 (8.7) 9.4 (5.5) 8.8 (6.9) 9.0 (5.4) | 0.12 0.19 0.90 0.88 1.01 0.82 0.14 | 0.73 0.66 0.35 0.35 0.32 0.37 0.71 |

| Fear of recurrencee, mean (SD) | 15.1 (4.6) | 16.2 (5.6) | 1.04 | 0.31 | 15.0 (4.9) | 15.2 (5.8) | 0.01 | 0.94 |

| . | 1 month . | 3 months . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . |

| Patients’ needsb, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total needs Psychological Health system and information Physical and daily living Patient care and support Sexuality | 76.1 (27.3) 24.1 (9.4) 26.0 (10.7) 10.4 (4.0) 10.8 (4.3) 4.7 (2.9) | 84.0 (30.6) 26.3 (10.0) 30.5 (14.6) 11.5 (4.0) 11.6 (5.5) 4.2 (2.2) | 0.09 0.14 0.61 0.16 0.05 0.02 | 0.77 0.72 0.44 0.69 0.82 0.90 | 73.6 (29.3) 22.7 (9.4) 25.3 (12.5) 9.5 (3.6) 11.1 (5.1) 4.3 (2.3) | 79.1 (30.5) 24.8 (10.7) 28.9 (14.0) 10.3 (4.0) 10.8 (5.0) 4.3 (2.0) | 0.00 0.05 0.14 0.11 0.51 1.21 | 0.99 0.83 0.71 0.75 0.48 0.28 |

| Quality of lifec, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Global health status Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Fatigue Nausea and vomiting Pain Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhoea Financial difficulties | 53.7 (20.7) 85.5 (14.0) 78.7 (17.2) 71.6 (23.3) 67.8 (25.2) 82.8 (15.1) 40.2 (23.1) 0.6 (3.1) 26.4 (20.7) 16.1 (19.1) 25.3 (27.7) 12.6 (18.7) 24.1 (28.0) 8.0 (14.5) 26.4 (24.2) | 62.5 (19.2) 82.6 (10.8) 72.6 (20.4) 71.1 (19.1) 64.3 (24.7) 81.0 (18.5) 41.7 (21.1) 1.2 (4.4) 28.6 (19.2) 17.9 (21.2) 28.6 (28.3) 13.1 (22.8) 26.2 (30.6) 14.3 (21.1) 26.2 (21.0) | 4.29 0.18 0.51 1.68 0.07 0.71 0.60 0.44 0.002 0.03 0.01 0.06 0.18 1.93 0.42 | 0.04 0.68 0.48 0.20 0.80 0.40 0.44 0.51 0.97 0.87 0.93 0.80 0.67 0.17 0.52 | 57.7 (22.4) 85.0 (15.8) 85.0 (15.8) 76.2 (18.7) 72.6 (19.4) 86.3 (13.6) 33.3 (21.2) 3.0 (7.9) 22.0 (19.3) 15.5 (19.2) 32.1 (29.4) 8.3 (17.3) 23.8 (25.4) 11.9 (20.7) 21.4 (18.6) | 65.2 (20.2) 86.0 (9.0) 86.0 (9.0) 75.6 (19.8) 66.7 (24.0) 81.5 (16.6) 41.3 (21.4) 3.0 (7.9) 23.2 (18.3) 17.9 (19.2) 27.4 (27.3) 15.9 (10.7) 21.4 (31.7) 13.1 (21.0) 20.2 (24.6) | 2.57 1.04 0.77 0.58 1.29 2.10 0.87 0.01 0.21 0.00 2.25 0.70 0.07 0.06 0.69 | 0.12 0.31 0.39 0.45 0.26 0.15 0.36 0.91 0.65 0.99 0.14 0.41 0.80 0.81 0.41 |

| Emotional distressd, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total mood disturbance Tension-anxiety Depression-dejection Anger-hostility Vigor Fatigue Confusion | 41.1 (38.6) 10.0 (6.8) 11.9 (12.1) 7.5 (7.6) 8.4 (5.1) 9.7 (7.1) 9.8 (5.7) | 44.9 (40.0) 11.5 (7.5) 13.8 (12.3) 9.1 (8.4) 8.3 (4.6) 9.0 (6.8) 9.7 (5.5) | 0.17 0.39 0.21 0.65 0.003 0.02 0.03 | 0.68 0.54 0.65 0.43 0.96 0.88 0.87 | 34.1 (35.8) 9.1 (7.2) 10.2 (9.5) 6.4 (8.3) 8.7 (5.0) 8.1 (6.6) 9.0 (4.8) | 38.8 (38.8) 10.3 (7.2) 11.7 (11.7) 8.3 (8.7) 9.4 (5.5) 8.8 (6.9) 9.0 (5.4) | 0.12 0.19 0.90 0.88 1.01 0.82 0.14 | 0.73 0.66 0.35 0.35 0.32 0.37 0.71 |

| Fear of recurrencee, mean (SD) | 15.1 (4.6) | 16.2 (5.6) | 1.04 | 0.31 | 15.0 (4.9) | 15.2 (5.8) | 0.01 | 0.94 |

SD, standard deviation.

aEach analysis is adjusted for its baseline score.

bAssessed by the Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire.

cAssessed by the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30.

dAssessed by the Profile of Mood States scale.

eAssessed by Japanese version of the Concerns about Recurrence Scale.

Patients’ perceived needs, emotional distress and fear of recurrence at 1 and 3 monthsa

| . | 1 month . | 3 months . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . |

| Patients’ needsb, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total needs Psychological Health system and information Physical and daily living Patient care and support Sexuality | 76.1 (27.3) 24.1 (9.4) 26.0 (10.7) 10.4 (4.0) 10.8 (4.3) 4.7 (2.9) | 84.0 (30.6) 26.3 (10.0) 30.5 (14.6) 11.5 (4.0) 11.6 (5.5) 4.2 (2.2) | 0.09 0.14 0.61 0.16 0.05 0.02 | 0.77 0.72 0.44 0.69 0.82 0.90 | 73.6 (29.3) 22.7 (9.4) 25.3 (12.5) 9.5 (3.6) 11.1 (5.1) 4.3 (2.3) | 79.1 (30.5) 24.8 (10.7) 28.9 (14.0) 10.3 (4.0) 10.8 (5.0) 4.3 (2.0) | 0.00 0.05 0.14 0.11 0.51 1.21 | 0.99 0.83 0.71 0.75 0.48 0.28 |

| Quality of lifec, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Global health status Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Fatigue Nausea and vomiting Pain Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhoea Financial difficulties | 53.7 (20.7) 85.5 (14.0) 78.7 (17.2) 71.6 (23.3) 67.8 (25.2) 82.8 (15.1) 40.2 (23.1) 0.6 (3.1) 26.4 (20.7) 16.1 (19.1) 25.3 (27.7) 12.6 (18.7) 24.1 (28.0) 8.0 (14.5) 26.4 (24.2) | 62.5 (19.2) 82.6 (10.8) 72.6 (20.4) 71.1 (19.1) 64.3 (24.7) 81.0 (18.5) 41.7 (21.1) 1.2 (4.4) 28.6 (19.2) 17.9 (21.2) 28.6 (28.3) 13.1 (22.8) 26.2 (30.6) 14.3 (21.1) 26.2 (21.0) | 4.29 0.18 0.51 1.68 0.07 0.71 0.60 0.44 0.002 0.03 0.01 0.06 0.18 1.93 0.42 | 0.04 0.68 0.48 0.20 0.80 0.40 0.44 0.51 0.97 0.87 0.93 0.80 0.67 0.17 0.52 | 57.7 (22.4) 85.0 (15.8) 85.0 (15.8) 76.2 (18.7) 72.6 (19.4) 86.3 (13.6) 33.3 (21.2) 3.0 (7.9) 22.0 (19.3) 15.5 (19.2) 32.1 (29.4) 8.3 (17.3) 23.8 (25.4) 11.9 (20.7) 21.4 (18.6) | 65.2 (20.2) 86.0 (9.0) 86.0 (9.0) 75.6 (19.8) 66.7 (24.0) 81.5 (16.6) 41.3 (21.4) 3.0 (7.9) 23.2 (18.3) 17.9 (19.2) 27.4 (27.3) 15.9 (10.7) 21.4 (31.7) 13.1 (21.0) 20.2 (24.6) | 2.57 1.04 0.77 0.58 1.29 2.10 0.87 0.01 0.21 0.00 2.25 0.70 0.07 0.06 0.69 | 0.12 0.31 0.39 0.45 0.26 0.15 0.36 0.91 0.65 0.99 0.14 0.41 0.80 0.81 0.41 |

| Emotional distressd, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total mood disturbance Tension-anxiety Depression-dejection Anger-hostility Vigor Fatigue Confusion | 41.1 (38.6) 10.0 (6.8) 11.9 (12.1) 7.5 (7.6) 8.4 (5.1) 9.7 (7.1) 9.8 (5.7) | 44.9 (40.0) 11.5 (7.5) 13.8 (12.3) 9.1 (8.4) 8.3 (4.6) 9.0 (6.8) 9.7 (5.5) | 0.17 0.39 0.21 0.65 0.003 0.02 0.03 | 0.68 0.54 0.65 0.43 0.96 0.88 0.87 | 34.1 (35.8) 9.1 (7.2) 10.2 (9.5) 6.4 (8.3) 8.7 (5.0) 8.1 (6.6) 9.0 (4.8) | 38.8 (38.8) 10.3 (7.2) 11.7 (11.7) 8.3 (8.7) 9.4 (5.5) 8.8 (6.9) 9.0 (5.4) | 0.12 0.19 0.90 0.88 1.01 0.82 0.14 | 0.73 0.66 0.35 0.35 0.32 0.37 0.71 |

| Fear of recurrencee, mean (SD) | 15.1 (4.6) | 16.2 (5.6) | 1.04 | 0.31 | 15.0 (4.9) | 15.2 (5.8) | 0.01 | 0.94 |

| . | 1 month . | 3 months . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . | Collaborative care + Treatment as usual . | Treatment as usual . | F . | P . |

| Patients’ needsb, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total needs Psychological Health system and information Physical and daily living Patient care and support Sexuality | 76.1 (27.3) 24.1 (9.4) 26.0 (10.7) 10.4 (4.0) 10.8 (4.3) 4.7 (2.9) | 84.0 (30.6) 26.3 (10.0) 30.5 (14.6) 11.5 (4.0) 11.6 (5.5) 4.2 (2.2) | 0.09 0.14 0.61 0.16 0.05 0.02 | 0.77 0.72 0.44 0.69 0.82 0.90 | 73.6 (29.3) 22.7 (9.4) 25.3 (12.5) 9.5 (3.6) 11.1 (5.1) 4.3 (2.3) | 79.1 (30.5) 24.8 (10.7) 28.9 (14.0) 10.3 (4.0) 10.8 (5.0) 4.3 (2.0) | 0.00 0.05 0.14 0.11 0.51 1.21 | 0.99 0.83 0.71 0.75 0.48 0.28 |

| Quality of lifec, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Global health status Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Fatigue Nausea and vomiting Pain Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhoea Financial difficulties | 53.7 (20.7) 85.5 (14.0) 78.7 (17.2) 71.6 (23.3) 67.8 (25.2) 82.8 (15.1) 40.2 (23.1) 0.6 (3.1) 26.4 (20.7) 16.1 (19.1) 25.3 (27.7) 12.6 (18.7) 24.1 (28.0) 8.0 (14.5) 26.4 (24.2) | 62.5 (19.2) 82.6 (10.8) 72.6 (20.4) 71.1 (19.1) 64.3 (24.7) 81.0 (18.5) 41.7 (21.1) 1.2 (4.4) 28.6 (19.2) 17.9 (21.2) 28.6 (28.3) 13.1 (22.8) 26.2 (30.6) 14.3 (21.1) 26.2 (21.0) | 4.29 0.18 0.51 1.68 0.07 0.71 0.60 0.44 0.002 0.03 0.01 0.06 0.18 1.93 0.42 | 0.04 0.68 0.48 0.20 0.80 0.40 0.44 0.51 0.97 0.87 0.93 0.80 0.67 0.17 0.52 | 57.7 (22.4) 85.0 (15.8) 85.0 (15.8) 76.2 (18.7) 72.6 (19.4) 86.3 (13.6) 33.3 (21.2) 3.0 (7.9) 22.0 (19.3) 15.5 (19.2) 32.1 (29.4) 8.3 (17.3) 23.8 (25.4) 11.9 (20.7) 21.4 (18.6) | 65.2 (20.2) 86.0 (9.0) 86.0 (9.0) 75.6 (19.8) 66.7 (24.0) 81.5 (16.6) 41.3 (21.4) 3.0 (7.9) 23.2 (18.3) 17.9 (19.2) 27.4 (27.3) 15.9 (10.7) 21.4 (31.7) 13.1 (21.0) 20.2 (24.6) | 2.57 1.04 0.77 0.58 1.29 2.10 0.87 0.01 0.21 0.00 2.25 0.70 0.07 0.06 0.69 | 0.12 0.31 0.39 0.45 0.26 0.15 0.36 0.91 0.65 0.99 0.14 0.41 0.80 0.81 0.41 |

| Emotional distressd, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total mood disturbance Tension-anxiety Depression-dejection Anger-hostility Vigor Fatigue Confusion | 41.1 (38.6) 10.0 (6.8) 11.9 (12.1) 7.5 (7.6) 8.4 (5.1) 9.7 (7.1) 9.8 (5.7) | 44.9 (40.0) 11.5 (7.5) 13.8 (12.3) 9.1 (8.4) 8.3 (4.6) 9.0 (6.8) 9.7 (5.5) | 0.17 0.39 0.21 0.65 0.003 0.02 0.03 | 0.68 0.54 0.65 0.43 0.96 0.88 0.87 | 34.1 (35.8) 9.1 (7.2) 10.2 (9.5) 6.4 (8.3) 8.7 (5.0) 8.1 (6.6) 9.0 (4.8) | 38.8 (38.8) 10.3 (7.2) 11.7 (11.7) 8.3 (8.7) 9.4 (5.5) 8.8 (6.9) 9.0 (5.4) | 0.12 0.19 0.90 0.88 1.01 0.82 0.14 | 0.73 0.66 0.35 0.35 0.32 0.37 0.71 |

| Fear of recurrencee, mean (SD) | 15.1 (4.6) | 16.2 (5.6) | 1.04 | 0.31 | 15.0 (4.9) | 15.2 (5.8) | 0.01 | 0.94 |

SD, standard deviation.

aEach analysis is adjusted for its baseline score.

bAssessed by the Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire.

cAssessed by the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30.

dAssessed by the Profile of Mood States scale.

eAssessed by Japanese version of the Concerns about Recurrence Scale.

Outcome measures: patients’ needs, QoL, psychological distress and fear of recurrence

There were no significant differences with regard to patients’ needs as assessed by SCNS-SF34, at both the 1-month and 3-month assessments (Table 3). Similarly, no significant differences were observed among other outcome measures, including QoL, psychological distress and fear of recurrence (Table 3), whereas the global health status score of patients in the TAU condition was higher at the 1-month assessment (P = 0.04). Similar findings were obtained after adjusting for age as a covariate.

Discussion

This study is the first randomized trial investigating the effectiveness of our newly developed brief collaborative care program to reduce patients’ unmet needs, which was directly provided by trained nurses supervised by psycho-oncologists. The program was found to be feasible and acceptable, insofar as >80% of the eligible patients agreed to participate, and >90% of the participants completed the intervention; however, the trial failed to show the effectiveness of the brief collaborative care program in reducing patients’ unmet needs, improving QoL and ameliorating psychological distress while the intervention group had an overall better tendency than the TAU group in patients’ perceived needs at 1 and 3 months.

Why did this collaborative care program not improve patients’ outcomes? Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate that psychosocial intervention programs for cancer patients are effective in improving their psychological outcomes (26–28). However, these studies suggest that psychosocial interventions generally have small-to-medium-sized effects on patients’ outcomes (26, 28). Considering that our newly developed collaborative care program emphasizes on brevity (e.g. program comprising only four sessions), one possibility is that this low intensity of the intervention program may result in a less effective outcome than expected. Actually some previous studies also failed to show the effectiveness of brief psychosocial intervention programs such as screening of needs and subsequent tailored support on improving patients’ unmet needs (29, 30). Our study suggests that balancing the brevity of the intervention and its clinical effectiveness is a relevant issue for future studies. Among all, appropriate estimation with regard to effect size of planned intervention should be relevant. Actually, our current estimation of effect size of 0.78 seems to be too large considering the effect sizes of other psychosocial intervention studies. Since the modality of the intervention seems to be feasible and acceptable, increasing the intensity of the intervention program while maintaining its brevity presents a challenge for the future development of a novel intervention program. Another possible reason for the lack of a significant result is sampling bias. A total of 25 patients were excluded from the present study because they were receiving psychiatric treatment by the clinical department (Fig. 1). These patients could suffer from clinical distress, and their exclusion might cause a bias because patients who actually needed help were excluded.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, it was conducted in one institution, so institutional bias could be a problem. Second, the sample sizes were relatively small and concerns could be raised about type II error (e.g. standard deviations for our outcomes were higher than expected), although the sample sizes were derived from a power calculation based on our preliminary study. Third, we do not know the parts and/or structures of the intervention that are problematic in relation to providing clinical relevance for the patients, because of the complexity of the intervention.

Clinical implications

The newly developed brief collaborative care intervention is not sufficiently effective in relation to subjective outcomes for highly distressed breast cancer patients, albeit that the program is feasible and acceptable. Further intervention programs having both brevity and intensity should be developed in future studies.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, and Technology (Grant No. 21390207) and a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Japanese Ministry of Labor, Health, and Welfare (Grant No. 201411002A).

Conflict of interest statement

Tatsuya Toyama received grants and lecture fee from Chugai, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, Novartis, Kyowa Kirin, Eisai, Takeda, Nippon Kayaku, Taiho, and lecture fee from AstraZeneca.