-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Li-Wen Lin, Curtis J. Milhaupt, Bonded to the State: A Network Perspective on China's Corporate Debt Market, Journal of Financial Regulation, Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2017, Pages 1–39, https://doi.org/10.1093/jfr/fjw016

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

A corporate bond market has the potential to play an important role as a supplement to bank-oriented financial systems in emerging markets—functioning in effect as a ‘spare tire’. Yet bond markets typically rely upon formal institutions that are lacking in developing economies. Despite significant institutional weaknesses, China’s corporate bond market has grown to become the third largest in the world. In this article, we use a network perspective to explore the formation, operation, and function of the Chinese corporate bond market. We explain the market’s exponential growth as a result of a network of relationships among state-owned or linked actors that has substituted for formal institutions. But the consequences of this state-centric network may undermine the spare tire function. We begin by unpacking the complexities of the market’s structure and formal regulation, which have been shaped by a surprising degree of regulatory competition. Next, we analyse China’s corporate bond market as a network of relationships that invariably lead back to the state, and explore the consequences of this network on the pricing, rating, and default of corporate bonds. The paper concludes by highlighting several important policy issues raised by our analysis, including the consequences of regulatory competition, the potential role of the bankruptcy system in handling issuer financial distress, and the linkages between the corporate bond market and China’s rapidly expanding shadow banking system. The size, and institutional fragility, of the Chinese corporate bond market illustrate both the accomplishments and limitations of state capitalism.

I. Introduction

The emergence of a corporate bond market, sometimes analogized to a ‘spare tire’, can play an important role in the maturation of bank-dominated financial systems in developing economies.1 Corporate bond finance diversifies risk away from the banking sector and expands financing channels for firms, particularly those that might otherwise lack access to the capital market. The corporate bond market also provides an alternative mechanism for monitoring corporate management and fosters practices essential to a robust financial system, such as a sound risk assessment culture and a reliable information disclosure regime. But creating a functional corporate bond market is difficult, because it requires a host of institutions that are usually underdeveloped or entirely lacking in a developing economy. These include credit rating agencies, a liquid trading market for debt, a robust regulatory regime, and reliable legal mechanisms for protecting bondholders in the event of an issuer’s default.

At least as measured by size, China has been spectacularly successful in developing a corporate bond market. Essentially non-existent 15 years ago, today China’s corporate bond market is the third largest in the world. Yet looks can be deceiving. A Standard & Poor’s report in 2014 garnered global media attention with its announcement that China had the largest amount of corporate debt in the world.2 While technically accurate, this conclusion was potentially misleading: the S&P analysts had included in their estimate a huge quantity of bonds issued by financing vehicles set up by local governments. As typically defined by the international financial community, these bonds constitute ‘corporate debt’ because they were issued by non-financial entities (ie special purpose vehicles). Moreover, in China the generic term ‘corporate bond’ encompasses several different types of debt instrument (under the jurisdiction of three different government regulators), including the type issued by these local government financing vehicles.3 Yet these are essentially municipal bonds in disguise, designed to circumvent, with the tacit approval of the central government, a law prohibiting local governments from issuing debt. Given these complexities, the confusion wrought by the S&P report is understandable. As The Economist remarked of this episode, ‘Just as staggering [as the amount of Chinese corporate debt] … is the challenge of figuring out who owes what to whom’.4

Despite its importance, size, and complexity, however, China’s corporate bond market has received relatively little academic attention.5 We seek to redress this situation, in part to deepen understanding of an important component of the Chinese financial system and the lessons it may hold for other developing economies. Equally important, given the distinctive aspects of China’s corporate bond market alluded to in the S&P example above, our study also serves to open a unique window into Chinese ‘state capitalism’ in operation.

In this article, we use a network perspective6 to explore the formation and effects of the complex web of relationships comprising China’s corporate bond market—relationships that overwhelmingly revolve around the state. We highlight the consequences of state-centricity for the market’s development—including concentration of risk in state-linked financial intermediaries, expansion of credit to local state-owned enterprises, and growth of the shadow banking system—and for its operation, including an increasingly fragile ‘no-default’ norm that has protected bondholders from issuer default. State-centricity may have played a large role in the extraordinary growth of China’s corporate bond market in the absence of the formal institutional infrastructure normally deemed essential to such a market’s development. Yet state-centricity also has unanticipated or unavoidable consequences that may undermine national government policy in promoting healthy growth of the corporate bond market. Thus, in addition to serving as a comprehensive study of this facet of China’s financial system, our article provides an important counterexample to the popular view of Chinese state capitalism as featuring a high degree of coordination among government ministries and highly successful implementation of national industrial policy.7

Section II provides an overview of the development, structure, and regulation of the Chinese corporate bond market, whose complexities have been shaped by a surprising degree of regulatory competition among the three central government ministries overseeing the issuance and trading of corporate debt instruments. Section III analyses the Chinese corporate debt market as a network, first by describing the actors and highlighting their relationships to the state; next, by examining the linkages that bind the actors, based on ownership, personnel ties, and organizational membership. Section IV explores the consequence of this network of relationships for the market’s development and operation. Section V considers several important policy implications of our study, drawing in part on the experiences of Japan and Korea, two other formerly high-growth, state-led8 East Asian economies with distinctive corporate bond markets in their developmental heydays.

II. Market Overview

In this section, we trace the trajectory of the Chinese corporate bond market’s development, provide an overview of the fairly complex array of debt instruments comprising the market, explain how they are regulated, and conclude by highlighting an important underlying dynamic that has shaped the Chinese corporate bond market to this point—one not commonly perceived to operate in a system of state capitalism—regulatory competition.

1. Developmental trajectory

China’s corporate bond market, like those of other developing countries, including Japan and Korea in earlier decades, played only a marginal role in corporate finance during its takeoff period.9 The reasons include ready access to loans from state-owned banks for the largest (typically state-owned) firms, heavy regulation of the bond market, both to control allocation of credit and to protect the state-owned banking sector, the relative attractiveness to firm managers of equity finance over bond finance, and as noted, under-development of institutions needed to support a robust corporate bond market, such as independent credit rating agencies and a liquid secondary market.

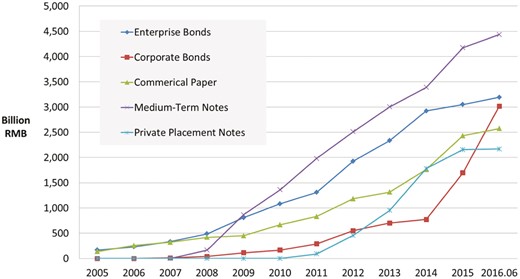

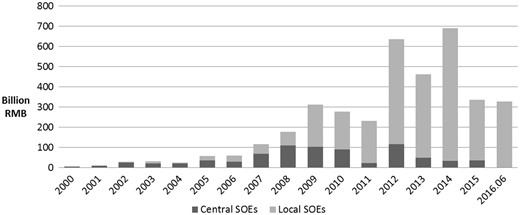

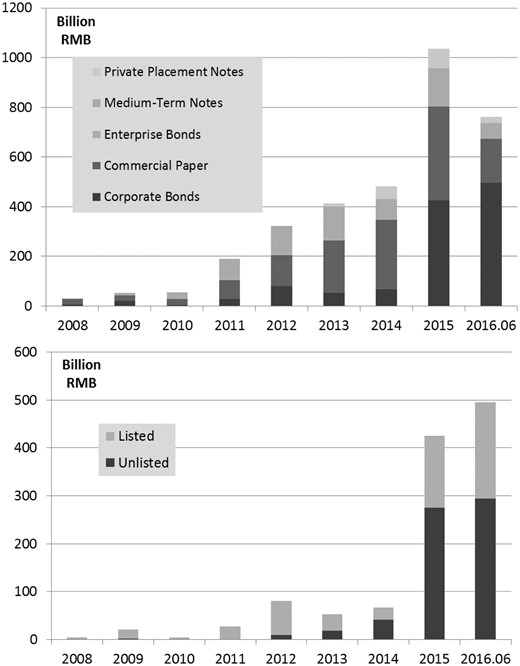

Outstanding balance by type of bond. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

2. Market segments and regulation

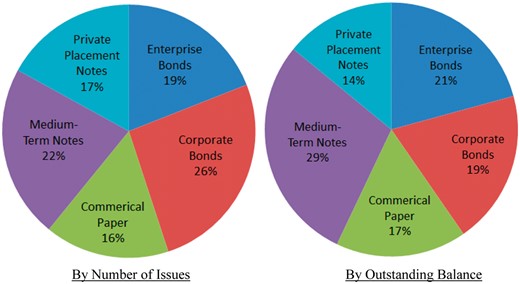

Size of each segment of China’s corporate bond market. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

a. Enterprise bonds

Beginning in the early 1980s, enterprises were permitted to issue bonds with the permission of the PBOC. The first regulations (‘Interim Regulations on Administration of Enterprise Bonds’) were promulgated by the State Council in March 1987. These debt instruments were called ‘enterprise bonds’ because the corporate form was not available in China until the passage of the first Corporate Law in 1993.14 The Interim Regulations recognized the legal status of enterprise bonds, but limited eligible issuers to SOEs. The PBOC was charged with overseeing the issuance of enterprise bonds and, in cooperation with a number of government agencies such as the State Planning Office (predecessor of the NDRC), it set annual quotas for enterprise bond issues, which were implemented at the local level. But the Interim Regulations were weakly enforced, and the amount of enterprise bonds issued greatly exceeded the quotas. Many bonds fell into default, and disorder in the enterprise bond market began to negatively affect the sale of government bonds. In response, the government took a number of measures which reduced the attractiveness of enterprise bonds.

During this early period of economic reform, the Chinese government was actively seeking to develop the stock market, launching the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges in 1990. After the stock markets opened, bond issues declined in favour of equity issues. Enterprise managers perceived equity to be a cheaper form of capital than bonds, especially because at the time there was no expectation that listed firms would pay dividends. In fact, Chinese enterprises paid no dividends to their public or state shareholders for many years after the stock markets were established. Moreover, the largest, most listing-worthy firms in this era were state-owned, having been ‘corporatized’ in the process of transitioning out of a centrally planned economy. The SOEs released only a small fraction of their shares to the public in the listing process; the vast majority were so-called ‘non-tradable shares’—more accurately, shares that could only be traded at the direction of the state, from one state-related entity to another. Public listing on a stock exchange therefore raised capital for the firm without diluting management’s (and the state’s) control rights or engendering meaningful capital market discipline. Given these circumstances, bonds were a less attractive source of capital.

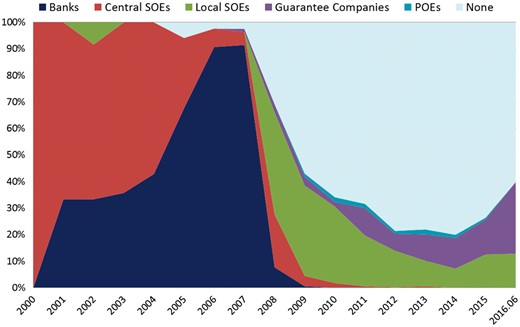

In 1993, the State Council promulgated Regulations on Enterprise Bonds (‘Regulations’). The Regulations provided that all enterprises with legal personality, not exclusively SOEs, were eligible to issue enterprise bonds through a public offering.15 The Regulations maintained the quota system for enterprise bond issues and, in view of past disorder in the market, provided that any deviation from the quotas required explicit authorization by the State Council. Enterprise bond issues of central SOEs were to be approved by the PBOC in conjunction with the State Planning Office; local SOEs received approval from the local counterparts of the PBOC and State Planning Office. To be eligible, an enterprise was required to meet requirements relating to size, accounting standards, solvency and profitability, and the issue had to be guaranteed by a (state-owned) bank. Moreover, the Regulations required that funds raised in the bond issue be used in a manner approved by regulators and consistent with national industrial policy. The Regulations prohibited the use of bond proceeds for real estate, stock and futures investments. Although as a legal matter enterprise bonds could now be issued by any corporation, virtually the only firms that could meet the requirements were central SOEs. In 2011, the State Council promulgated new Regulations on Enterprise Bonds, but in substance, the new and old regulations are virtually identical.

While the Regulations contemplate that both the PBOC and the NDRC are responsible for regulating enterprise bonds, in practice only the NDRC exercises regulatory authority over this segment of the corporate debt market. NDRC regulatory authority is premised on the notion that enterprise bonds not only serve an individual firm’s financing needs, but more importantly, support national industrial policies. As noted, the Regulations expressly implement this goal: capital raised in an enterprise bond issue must be used in a manner consistent with national industrial policies.16 Enterprise bonds have been used mostly to support government-approved projects on fixed-asset investment and technological innovation.

Percentage of enterprise bonds guaranteed, by type of guarantor. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), complied by authors.

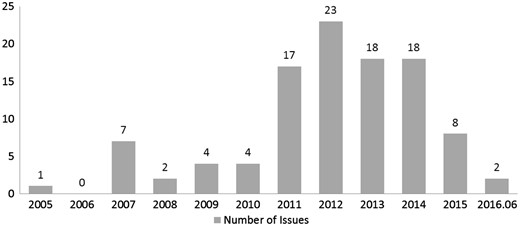

Number of enterprise bonds issued by private enterprises. Source: raw data collected from WIND and www.chinabond.com (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

It is instructive to examine the POEs approved to issue enterprise bonds; they illustrate the NDRC’s use of the debt instrument to promote national objectives. One such POE is Legend Holdings Limited, the controlling shareholder of its well-known subsidiary, the Lenovo Group. Legend issued enterprise bonds in 2011 and 2012, with most of the proceeds used to develop ethylene derivatives. The bond prospectus notes that ‘this product structure, market position, and the company’s orientation toward the development of new materials and refined chemical engineering are consistent with the government’s industrial restructuring plan during the period of the 12th 5-year plan’.20 Another example is Tianrui Group, a cement producer, one of the 500 largest private enterprises in China. In 2014, the NDRC of Henan Province approved Tianrui’s issue of up to 5 billion RMB (US$750 million)21 in enterprise bonds, a record for private enterprises. The NDRC approved the bond issue to alleviate oversupply in the cement industry through mergers and acquisitions and technological upgrades.22 The NDRC’s approval notice states that the bond proceeds should be directed towards a basket of measures such as acquisitions and plant closures to solve cement oversupply problems.

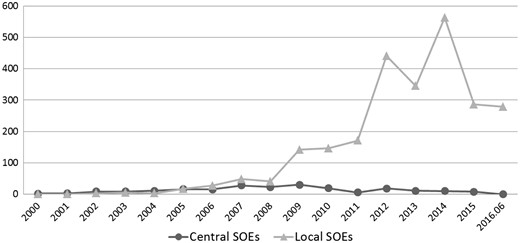

Central SOEs versus local SOEs by number of enterprise bond issues. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

Central SOEs versus Local SOEs by volume of enterprise bond issues (Billion RMB). Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

b. Corporate bonds

Although Corporate Bonds25 have been recognized in China’s company law and securities law—and subject to regulation and approval by the CSRC—since the 1990s,26 virtually all of the bonds issued by Chinese corporations until the mid-2000s were enterprise bonds. Responding to this situation, China’s 11th Five Year Plan (2006–10) featured development of the corporate bond market as one of its major goals. The current regulatory framework for Corporate Bonds is provided by the CSRC’s Administrative Measures on Corporate Bond Issuance and Trading (‘Administrative Measures’), promulgated in January 2015.27

The Administrative Measures (and the prior set of regulations they replaced) provide simply that Corporate Bonds may be issued by ‘companies’—listed or unlisted. However, in practice, until 2015 the CSRC permitted only listed companies to issue Corporate Bonds.28 The CSRC must approve all Corporate Bond issues. Most of the bonds are traded on either the Shanghai Stock Exchange or the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. As Figure 2 indicates, Corporate Bonds represent a relatively small share of the overall market for corporate debt securities—accounting for 26 per cent of the market by number of issues and 19 per cent by outstanding balance as of 30 June 2016. However, there has been a spike in the issuance of Corporate Bonds in the past year, after the CSRC began to permit their issuance by unlisted firms.29

c. Commercial paper, medium-term notes, and private placement notes

Commercial paper (CP) and medium-term note (MTN) issues first emerged in the late 1980s, but they were suspended in the ensuing decade due to market disorder. In an effort to jump start the corporate bond market, CP was reintroduced by the PBOC in 2005 and MTN were reintroduced in 2008.30 Both forms of debt are traded in interbank markets. Figure 2 indicates that CP and MTN now comprise a majority of China’s corporate bond market, both by number of issues and outstanding balance. There are several major attractions of CP and MTN over the other forms of corporate debt in China: they carry comparatively low interest rates and can be issued in small amounts; they are unsecured; and they impose no restrictions on the issuer’s use of proceeds. Most importantly, CP and MTN issues are subject only to a registration regime, in contrast to the pre-approval process for enterprise bonds and Corporate Bonds.31 Private placement notes, a form of short-term debt security similar to MTN, are privately placed with institutional investors.

d. Small and medium-sized enterprise bonds

China’s financial system has historically provided privileged access to credit to large, particularly state-owned, enterprises. Small and medium-sized enterprises—whether SOE or POE—have faced more limited formal financing options. In recent years, the Chinese government has sought to address the situation. Each of the three regulators of the corporate bond market has created a debt instrument designed for use by SMEs. The NDRC introduced the ‘small and medium-sized enterprise collective bond’ in 2007.32 This is a bond that essentially bundles the credit risks of a number of companies. A more successful competing alternative, ‘small and medium-sized enterprise collective medium-term notes’, was introduced in 2009 by the PBOC. And the CSRC now permits SMEs to issue bonds via private placement. It has delegated to the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges the authority to oversee issuance and trading of these bonds. In 2012, the stock exchanges jointly released Experimental Measures on Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Private Placement Bonds.33 Under the Measures, bonds must be guaranteed and are traded on a special platform provided by the exchanges open only to qualified investors. As of the end of 2014, 631 bonds were listed on this platform, with a value of 91.2 billion RMB (US$13.7 billion). A majority of the issuers are POEs, but small and medium-sized SOEs also participate in this market.

3. Regulatory competition

Outstanding corporate debt securities, by regulatory jurisdiction. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

The competition among the NDRC, PBOC, and CSRC not only reflects the separation of power within China’s central bureaucracy, it also highlights significant differences in regulatory philosophy that drive the various regulatory methodologies and result in different degrees of market liberalization. NDRC-regulated enterprise bonds are a legacy of the planned economy, in which the state uses the market for its own purposes. To varying degrees, the PBOC-deregulated interbank market for short-term debt and the CSRC-regulated Corporate Bond market reflect the state’s continuous, experimental efforts to build a market economy within the state-capitalist system.

At times, turf battles among the three regulators have surfaced publicly. One recent head of the CSRC publicly suggested consolidating regulatory authority over both enterprise bonds and Corporate Bonds in the CSRC. But the trial balloon was quickly shot down by the NDRC. As Figure 7 shows, until very recently the NDRC regulated a larger share of the overall corporate bond market than the CSRC, placing the latter agency in a relatively weak position to argue that it should be the sole regulator. Moreover, the NDRC has justified its continued regulatory involvement in the market by contrasting the role of enterprise bonds in serving the needs of state-backed development projects with that of Corporate Bonds under the CSRC’s purview, which serve the financing needs of individual firms. The NDRC’s expertise and central role in formulating and implementing national industrial policy, perhaps bolstered by the legacy of the planned economy, have given it a leg up in its regulatory competition with the CSRC.

In contrast to the CSRC’s unsuccessful direct public challenge to the NDRC, the PBOC has quietly sped past the regulatory space occupied by the other two ministries. As noted, prior to 2005, with limited exceptions, virtually the only corporate debt securities in the market were enterprise bonds regulated by the NDRC or its predecessor agency. The PBOC injected competition into the market when it authorized the issuance of CP in 2005—a move explicitly aimed at resuscitating the moribund corporate bond market. Commercial paper quickly overtook enterprise bonds in number and volume. But the NDRC did not remain passive in the face of this competition,35 and enterprise bond issues spiked up in the wake of the PBOC’s initiative. The PBOC, in turn, responded by approving the issuance of MTN in 2009. Because MTN have terms and maturities quite similar to those of enterprise bonds and Corporate Bonds, they posed a direct challenge to the NDRC and CSRC. Innovations with respect to enterprise bonds (ie allowing POEs and LGFVs to issue enterprise bonds) and Corporate Bonds (ie allowing unlisted firms to issue Corporate Bonds), and the ensuing increase in the issuance of these debt instruments, were prompted in part by the challenge posed by the PBOC’s lighter regulatory approach.

While regulatory competition has probably benefited Chinese firms of all types seeking capital, the biggest winners in this competition are local SOEs and LGFVs—the principal issuers of enterprise bonds, CP and MTN since 2009—and their backers, the local governments.

III. The Chinese Corporate Bond Network

Although the term ‘market’ is ubiquitous in reference to the organizational structure in which the issuance and trading of corporate bonds takes place, as the Introduction noted, developing economies typically lack the institutional infrastructure needed to create a fully functional corporate bond market. China is no exception. For this reason, we believe that approaching the Chinese organizational structure for bond issuance and trading as a network provides a helpful analytical framework for understanding its features and consequences. Therefore, in this section of the article, we examine the actors comprising the network and the relationships that bind them to the state.

1. Actors

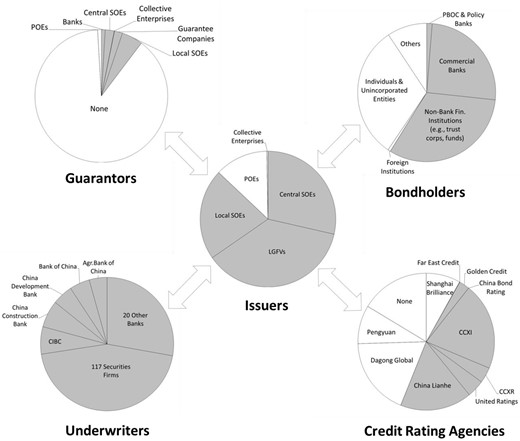

a. Issuers

In China, corporate debt instruments are issued overwhelmingly by enterprises whose majority (and perhaps sole) shareholder is an organ of the central or local government. The largest issuers by amount of outstanding bonds are LGFVs, with 36.8 per cent of the total. The next largest category of issuers, with 28.6 per cent of the total, are central SOEs, whose controlling shareholder typically is the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC).36 SASAC, established under the State Council in 2003 and acting on behalf of the state, is the formal shareholder in non-financial, central SOEs. It also performs regulatory functions and, together with a senior Communist Party committee, appoints, rotates, and sets compensation for the top managers of the SOEs under its supervision. We described SASAC elsewhere as ‘the organizational manifestation of the party-state in its role as controlling shareholder’.37 Next are local SOEs, under the control of provincial-level SASACs, with 21.7 per cent of the total. Collective enterprises, also state-affiliated, comprise the smallest group of issuers, with 0.3 per cent of the total. Issuances by POEs, at least as classified according to equity ownership,38 account for only 12.7 per cent of all outstanding corporate bonds.

b. Underwriters

One striking fact about corporate bond underwriting in China is the large number of lead underwriters in the market. Over 140 lead underwriters were involved in the issuance of the corporate debt instruments outstanding as of June 2016. No Chinese financial institution, however prominent, has captured more than a small fraction of the underwriting market. The big four Chinese state-owned banks together account for 22.4 per cent of the market. Collectively, 117 securities firms account for 44.8 per cent of the market. Several other major financial institutions, such as CITIC Securities and Agricultural Bank of China, each have 4–5% of the market. The large number of underwriters in the Chinese corporate bond market may partially be a function of the huge volume of bonds issued by local SOEs and LGFVs. But this does not appear to be the only explanation, as even the central SOEs have used 77 different lead underwriters. More importantly, it reflects an attempt by the government to diversify risk through syndication. This may be of particular concern to the government due to the second striking feature of the underwriting market: the pervasiveness of state ownership. Of the financial institutions with at least 2 per cent of the underwriting market, only one—Minsheng Bank, is not state-owned.39

c. Guarantors

Most corporate debt securities are no longer required by law to be guaranteed. As discussed in Section II, virtually all enterprise bonds were guaranteed until 2007, when banks were prohibited from serving as guarantors. Of the bonds that are guaranteed, the guarantors are almost exclusively enterprises affiliated with the state: the most common guarantors are local and central SOEs, state-owned banks, and guarantee companies, which are state-owned or affiliated with state-owned banks.40 In a small number of cases, a POE serves as a guarantor, principally in connection with a bond issuance by another POE, but in rare instances POEs have served as guarantors for bonds issued by local SOEs, LGFVs and collective enterprises. The reverse phenomenon also exists in some cases, where a POE receives a guarantee from a local SOE. These cases obviously suggest the existence of close linkages between the particular POE and local government officials. The resolution of some recent default crises discussed in Section IV illustrates the effects of these linkages.

d. Credit rating agencies

China has nine domestic credit rating agencies—a large number, even for a market of its size. Competition among the rating agencies is fierce, inviting credit ratings shopping. Five of the rating agencies are at least majority state-owned, although several have formed alliances with Moody’s or S&P. Sixty per cent of all rated corporate bonds in China were rated by a state-owned ratings agency. One of the most prominent rating agencies, Dagong Global Credit Rating (18.4 per cent of all ratings by volume), is privately owned, but commentators have expressed doubts about its actual independence from the Chinese government.41 In fact, Dagong fits the profile of many prominent POEs in China: although it is ‘private’ from the standpoint of equity ownership, its origins have roots in the Chinese government, and it is led by a politically well-connected controlling shareholder whose business model is closely aligned with the policy objectives of the Chinese government.42 We assess the effects of the credit rating agencies’ links to the state in Section IV.

e. Bondholders43

Major holders of Chinese corporate debt can be grouped into several categories. First are trust corporations, funds, and other non-financial institutions—members of China’s shadow banking system—which as of June 2016 held 32.2 per cent of all outstanding corporate debt instruments. Chinese trusts are ‘a unique form of financial institutions, to which there is nothing comparable in the developed markets’.44 The trust is the only financial license in China that permits investments in the entire range of asset classes: the money market, the capital markets, and unlisted assets such as loans. This allows the trust to serve as a conduit between firms that want to launch investment products and firms that want to invest in multiple asset classes. The most prominent use of the trust license is by Chinese banks marketing wealth management products to high-net worth individuals.45 There are 68 licensed trust companies in China. According to one assessment, 27 of these are owned by a local government, 20 are owned by an SOE parent company, and 12 are part of a large corporate group, most of which are SOEs.46 These state-affiliated trusts collectively account for 92 per cent of assets under management in the trust industry.47 A McKinsey study finds that ‘many trust companies are quite primitive in terms of quality of management’ and investors perceive there to be an implicit guarantee of their principal, particularly since most trust companies are owned by SOEs and there is no way to verify the due diligence and risk disclosures made by the trusts.48

Another major category of corporate bondholders in China is comprised of national commercial banks, virtually all of which are state-owned. As of June 2016, the banks collectively held 25.4 per cent of outstanding corporate debt instruments. Individuals and unincorporated entities (which may include funds) accounted for 31 per cent of the market. Not counting a small percentage of shares held by the Chinese government, foreign banks and offshore institutions, this leaves about 9 per cent of outstanding corporate debt instruments held by ‘others’. The ‘other’ category includes online money market funds, another actor in China’s rapidly expanding shadow banking system.

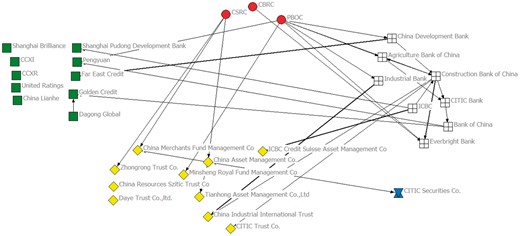

2. Linkages

In previous work, we suggested that China’s central SOEs can profitably be understood as a ‘networked hierarchy’.49 We used this term to describe the way in which the massive business groups under SASAC supervision (a hierarchical form of corporate organization) are deeply enmeshed in a dense network of party and government institutions through equity ownership, personnel rotations, and membership in organizations that transmit party and industrial policy. This network serves to connect the separate components of the state-owned sector into a complementary whole.50 We argued that Chinese economic strategists’ encouragement of the formation of state-owned business groups in the 1980s and 90s reflected the familiar motivations of filling institutional voids in weak rule-of-law environments and internalizing the capital markets during an early phase of economic development.51

China’s corporate bond network. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016). Each pie chart represents the total outstanding balance of bonds issued/underwritten/rated/held. Gray shading indicates state ownership; white indicates private ownership.

Issuer–guarantor relationships, by outstanding balance. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016). Bonds issued without guarantees are not shown. The width of each flow reflects the relative amount of outstanding bonds guaranteed by a particular type of guarantor.

CEO/chairman career network. Source: raw data collected from corporate websites and annual reports (as of December 2015).

A third type of connective tissue in state-sector networks, whether corporate or financial, is membership in organizations that carry out quasi-governmental tasks. In the corporate bond network, this function is played by membership in the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII), a self-regulatory organization under the supervision of the PBOC.55 Its members include individuals and institutions across the entire financial industry. The management council of NAFMII has committees responsible for different market domains, the most relevant of which are a bond market committee and a credit rating committee, whose members include officials from the PBOC, NDRC, Ministry of Finance, and Insurance Regulatory Commission. Self-regulatory organizations are of course commonplace in the financial industry around the world. In China, however, SROs are not substantively distinguishable from other organs of the party-state. Leadership of SROs is appointed through the Party’s regular nomenklatura system, government regulators are also members, and most of the institutional members are affiliated with the state. Thus, SROs actually serve as a powerful coordinating mechanism for the formulation and implementation of government policy.

IV. The Consequences of State Centricity

Section III has painted a picture of the organizational structure for corporate bonds in China that is less like a ‘market’ and more like what scholars have evocatively referred to as a ‘network with a spider’. 56 These are ‘networks that form around (or are formed by) a central agent—a regime that exercises some control over the distribution of benefits and costs in the network’.57 China’s corporate bond network has a very large spider at its core—the party-state. In this section, we consider the impact of state-centricity on the corporate bond market’s developmental trajectory and operation.

1. Market development

As previously discussed, after a brief and problematic initial experiment with a lightly regulated corporate bond market in the 1980s, the Chinese government exerted tight control over the market for the next decade and a half, effectively limiting corporate debt issues (in the form of enterprise bonds) to central SOEs in service of national industrial policy. In this sense, the Chinese corporate bond market developed in a manner reminiscent of its Japanese and Korean counterparts, in which bond issues were effectively limited to the largest firms enjoying close relations with major banks and, by extension, the financial regulators. For example, in Japan corporate bond issues were strictly allocated among large firms by a group of large banks acting as the Committee on Bond Issues (Kisaikai) under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Finance.58 Under the Committee’s guidelines, only firms that could post collateral were eligible to issue bonds. In combination with the regulation of interest rates, this practice resulted in capital being preferentially allocated to heavy industries in support of Japan’s export-oriented, income doubling plan.59 In Korea, the government favoured large business conglomerates (chaebol) in the allocation of capital; accordingly, the early corporate bond market was dominated by chaebol issuers. As in Japan, a high-growth, export-oriented economy provided a favourable environment for these Korean bond issuers. In all three East Asian countries, however, during their formative growth periods corporate debt played a distinctly secondary role to bank finance, both as a means of protecting the banking sector from competition and because growth of the corporate debt market raises the spectre of risks that all three governments assiduously sought to avoid: losing control over the allocation of credit and the negative fallout of corporate bond defaults.

Despite these similarities, the development of the Chinese corporate bond market has several distinctive characteristics that set it apart from those of other developing countries. These distinctive characteristics bear the hallmarks of Chinese state capitalism. The first is the use of sophisticated structures developed in a market environment to advance political interests and policies. 60 A prime example is the LGFV, which puts the globally familiar capitalist tool of the special purpose vehicle to work in service of local Chinese infrastructure investment, circumventing a national-level prohibition against the issuance of local government debt. As one commentator notes, ‘[t]he central government acquiesced in or even supported local governments’ efforts to tackle their financing problem’,61 leading to a joint declaration by the PBOC and the CSRC supporting the issuance of enterprise bonds and MTN by local government financing platforms.62 In this case, the corporate bond market functioned not as a means of financing the projects of individual firms or a national plan for economic growth, but as a device to ease the transition from a planned economy to a market economy, filling a funding gap created by decentralization of power and decline of revenues flowing from the centre to the provinces.63

A second characteristic of the bond market closely associated with Chinese state capitalism is the blurring of the conventional distinction between state-owned and private enterprises, as determined by equity ownership. As one of us has noted in previous work, the state/private dichotomy breaks down in China because the institutional environment—extensive state intervention in the economy, weak formal institutions to check state power, and the pervasive influence of the Communist Party—encourages all firms to seek rents from the state by cultivating ties to party and government organs and by aligning their business models with the policy objectives of the Party-state.64 Examples in the corporate bond market include the NDRC’s decision to allow POEs to issue enterprise bonds if the proceeds promote specific national industrial policies, POE guarantees of the bonds issued by local SOEs, and the perception of Dagong as a ‘state-controlled’ credit rating agency despite its status as a ‘private’ firm from the perspective of equity ownership.

Finally, the consequences of state centrism are clearly reflected in the characteristics of issuers in the Chinese corporate bond market. By number of bonds outstanding as of June 2016, LGFVs (5410 issues) and local SOEs (4189) are the largest issuers. There are somewhat more issues by POEs (2268) than by central SOEs (1726); however, the amount of outstanding bond issues and the average issue size of bond issues by central SOEs swamp those of POEs. For example, the average issue size of all types of corporate bonds issued by central SOEs is 2.6 billion RMB, as compared to 0.9 billion RMB for POEs. LGFV issues average 1.09 billion RMB and local SOE issues average 0.83 billion RMB. This is despite the fact that POEs are more profitable than the state-owned/linked issuers.65 Proceeds of bond issues by state-owned/linked issuers have been used largely to finance construction, real estate, infrastructure, and mining. Bond issues by POEs have financed a broader spectrum of industrial sectors. Collectively, the data suggest that China’s corporate bond market principally serves the interests of state-owned/linked issuers, rather than the financing needs of China’s private sector. The regulatory competition that has partially fuelled explosive growth in bond issues, therefore, has principally benefitted state actors.

Arising out of this developmental trajectory, of potentially significant importance, are the deep linkages that have emerged between China’s corporate bond market and the shadow banking system, whose main players are also closely linked to the state.66 As noted in the previous section, corporate bonds have become an important destination for investment by Chinese trust companies and funds, which market wealth management and related products to high net worth individuals seeking higher returns than are otherwise available in the domestic credit market. These funds have fuelled expansion of the corporate bond market, particularly by increasing demand for higher-quality bonds. At the same time, players in the shadow banking system leverage the corporate bond market to circumvent regulatory obstacles. For example, shadow banking actors use funds raised in the corporate bond market to finance SMEs that cannot themselves issue bonds, either due to eligibility requirements or because the costs of issuance are too high.67 In similar fashion, LGFVs leverage the corporate bond market by issuing ‘special enterprise bonds’ regulated by the NDRC and using the proceeds to extend credit to SMEs with low credit quality. The market considers these bonds to be effectively guaranteed by the local government that established the LGFV. Consequences of the interconnectedness between the corporate bond market and the shadow banking system will be explored in Section V.

2. Market operation

State centricity has left an indelible mark not only on the market’s developmental path, but also on the way it currently functions. Credit ratings, pricing, and issuer defaults reflect the deep penetration of state policies and interests into the basic mechanisms of the market’s operation.

a. Credit ratings

As discussed above, China’s credit rating industry is closely linked to the state, which is also the direct or indirect owner of the largest issuers in the corporate bond market. It is not surprising, then, that the reliability of China’s credit ratings has been questioned. Credit ratings in China are heavily skewed towards the high end of the ratings scale. According to our analysis, of the approximately 10,000 corporate bonds outstanding as of June 2016 that received a rating at the time of issuance, almost 90 per cent received ratings of AAA to AA, and just 0.27 per cent received a rating of BBB or lower.68 There is a much wider distribution of corporate bond credit ratings in the US, the EU, and globally.69 The Chinese ratings likely reflect the fact that the market, at least among rated issuances, has been largely confined to the largest and most politically connected firms, for which default risk has long been considered to be essentially non-existent, as discussed in the next section. Consistent with this view, almost all corporate bonds issued by SOEs receive an AAA rating, compared to less than 15 per cent of bonds issued by POEs.70 But this explanation is incomplete, as many of the default crises discussed below involved bonds rated A, and in some cases AA or AAA. As one report notes, ‘domestic Chinese credit ratings are widely considered to not be equivalent to ratings from international agencies’.71 Available data support this contention: a small percentage of Chinese corporate bonds have been rated by both an international rating agency and a domestic rating agency. For these bonds, the international ratings display a much wider level of credit quality differentiation than the domestic ratings,72 and some bonds rated AAA by Chinese rating agencies have received ‘junk’ ratings from international rating agencies.73

b. Pricing

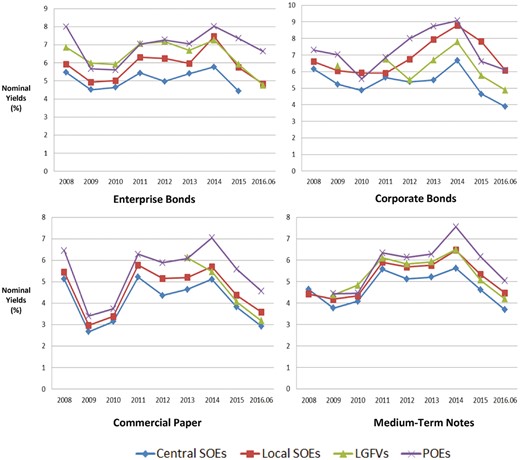

Nominal yields, by type of issuer and debt instrument. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

The term ‘bond market’ conjures up the cut and thrust of a developed economy, but in the Chinese context it means something very different. The market is distorted and fails to price risk appropriately… . The absence of default has made it impossible to price the bonds of state-owned firms and the deals are often done on the basis of other conditions as well. The result is a manufactured spread between government bonds, state-owned firms’ bonds and private firms’ corporate bonds.75

c. Default

In the absence of strong institutions to protect investors, it is common for bonds in emerging markets to be covered by an implicit guarantee. This was true in Japan, where market norms, though nothing in the law, required corporate bond trustees (uniformly major banks) to repurchase at par the bonds of defaulting issuers.76 It has long been conventional wisdom that all corporate bonds in China are covered by an expectation of full repayment thanks to an implicit guarantee from the government.77 In recent years, the no-default norm has been challenged by a number of defaults and near defaults on Chinese corporate debt instruments. Table 1 lists defaults by ownership type of the issuer and type of bond.

| Type of Bond . | Type of Issuer . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Central SOEs . | Local SOEs . | POES . | |

| Enterprise Bond | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Corporate Bond | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Commercial Paper | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Medium-Term Note | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Private Placement Note | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Private Placement Bond | 0 | 2 | 19 |

| Total | 10 | 16 | 34 |

| Type of Bond . | Type of Issuer . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Central SOEs . | Local SOEs . | POES . | |

| Enterprise Bond | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Corporate Bond | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Commercial Paper | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Medium-Term Note | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Private Placement Note | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Private Placement Bond | 0 | 2 | 19 |

| Total | 10 | 16 | 34 |

Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

| Type of Bond . | Type of Issuer . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Central SOEs . | Local SOEs . | POES . | |

| Enterprise Bond | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Corporate Bond | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Commercial Paper | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Medium-Term Note | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Private Placement Note | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Private Placement Bond | 0 | 2 | 19 |

| Total | 10 | 16 | 34 |

| Type of Bond . | Type of Issuer . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Central SOEs . | Local SOEs . | POES . | |

| Enterprise Bond | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Corporate Bond | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Commercial Paper | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Medium-Term Note | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Private Placement Note | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Private Placement Bond | 0 | 2 | 19 |

| Total | 10 | 16 | 34 |

Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

When an SOE defaulted on a bond payment in the spring of 2015, analysts were quick to interpret the episode as a ‘landmark for market discipline in the corporate bond market’.78 Yet as we explore below, how and why the no-default norm has been operationalized—and the significance of default in the market—are more complex than conventional wisdom suggests. In this section, we examine several episodes of default or near default to understand how relationships among state-linked actors in the Chinese corporate bond market affect behaviour during repayment crises. Close examination of these episodes provides a more nuanced perspective on when and why Chinese corporate bonds are implicitly backed by the state. This perspective, in turn, sheds light on how the no-default norm may begin to unravel as the Chinese economy slows.

To structure the discussion, we disaggregate the motivations behind the no-default norm into three partially overlapping categories, which we label as follows: TCTF (Too Connected to Fail), in which an issuer is either an SOE enjoying the implicit guarantee of the central or (more typically, local) government, or a POE whose founder or controlling shareholder has strong political backing; TMTF (Too Many to Fail), in which a default would affect a group of individual Chinese bond holders large enough to raise the spectre of social unrest, a deeply worrisome outcome for the Chinese Communist Party; and TBTF (Too Big to Fail), in which an issuer’s default is avoided because it may trigger contagion in the financial system. Whereas TBTF responds to systemic risk, TCTF and TMTF respond to political and social risk.

It bears noting that, as Table 1 shows, relatively few defaults have involved enterprise bonds or Corporate Bonds. Recall that enterprise bonds are issued exclusively by central SOEs, LGFVs, and major POEs advancing national industrial policies, subject to pre-approval by the NDRC. Enterprise bond defaults could thus be embarrassing to the government, and may be avoided by arranging loans from state-owned banks to cover payments of interest and principal. Much the same holds for Corporate Bonds regulated by the CSRC, which are also subject to pre-approval and have been issued by large SOEs and POEs. Moreover, Corporate Bonds are traded on the stock exchanges and potentially held by significantly more private investors than bonds traded in the interbank market, heightening the fear of social unrest in the event of non-payment. Virtually all of the repayment crises in the Chinese corporate bond market have involved CP, MTN, and privately placed bonds and notes. These instruments are subject to a lighter regulatory regime than enterprise bonds and Corporate Bonds. Moreover, because these instruments are placed with a small number of qualified investors, risk of social instability in the event of default is comparatively low.

TCTF: As the preceding analysis has indicated, many Chinese corporate bond issuers are affiliated with the state. Some SOE issuers are so integrally connected to the government that default can be avoided by invoking assistance from other entities connected to the same governmental controller. One example is CP issued by Shandong Helon Co. Ltd, a company controlled by Weifeng Investment, an SOE under the local SASAC of Weifeng City. When Helon was unable to repay its maturing CP in April of 2012, the funds were provided in the form of a loan from Evergrowing Bank, its lead underwriter. The loan was guaranteed by Weifeng City, in essence the ultimate controlling shareholder of Helon.

But SOEs are not alone in enjoying implicit backing from the state. Private enterprises that are important to the government also enjoy protection from default. LDK Solar is one example. LDK Solar is a manufacturer of photovoltaic products. Its controller was Xiaofung Peng, one of the wealthiest people` in China and a member of both the 11th People’s Congress and the 11th Political Consultative Conference of Jiangxi Province. LDK was hand-picked by the NDRC as one of six companies in the photovoltaic industry to receive government backing. The company grew rapidly with the financial support of the local government, eventually becoming the largest taxpayer and a major employer in Xinyu City. In 2012, LDK was ranked as the 266th largest company in China, and one the few from Jiangxi Province. But the company’s performance declined rapidly after the financial crisis and due to an oversupply in the global photovoltaic market. As a result, LDK had trouble paying its debts, including a CP issue due in October 2012. But in the end, there was no default—LDK paid the CP at maturity. Although it has never been confirmed, the source of the funds is assumed to be Xinyu City, which had earlier approved, in apparent violation of a national law, the use of city government funds to pay off LDK’s debts to a local SOE.

In the preceding case, the TCTF motivation was likely buttressed in part by localized TBTF concerns, given the importance of LDK to the local economy. But TCTF can be at work even where the bond issuer is neither an SOE nor a large POE. Private enterprises of little economic consequence to the government can be protected from default if the founder is sufficiently influential. For example, the earliest default crisis since the re-emergence of China’s corporate bond market in the mid-2000s involved a small (100 million RMB; or $15 million) CP issuance by Fuxi Investment Holding Co. Ltd, which invested in highway companies. Fuxi was controlled by Rongquan Zhang, a member of the 10th National People’s Political Consultative Conference and numerous Shanghai business associations. Somewhat curiously, the small CP issuance was underwritten by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), one of the big four state-owned banks.79 When Zhang became embroiled in a corruption investigation in Shanghai, creditors sued Fuxi and succeeded in freezing its assets. Fuxi’s ability to repay the CP was consequently put into doubt, and the credit rating on the paper was lowered to C, the first Chinese debt instrument ever to receive a rating that low. Bondholders (largely mutual funds) eventually participated in a negotiation hosted by the PBOC, during which an arrangement was made to deposit funds sufficient to repay the CP in a court-monitored account. The source of the funds is unknown, but it is assumed to be the Shanghai branch of ICBC.

TMTF: Another motivation for the no-default norm is the Chinese Communist Party’s overriding concern for social stability. Where the effects of a default would be felt by a large number of bondholders, Party-state actors have substantial incentive to make them whole. An example is provided by Chaori Solar Energy Science and Technology Co., a manufacturer of solar energy products. Chaori was founded by Kailu Ni, originally a farmer, who enjoyed close relations with the Shanghai local government. Chaori issued five-year unsecured Corporate Bonds in the amount of 1 billion RMB ($150 million) in 2012. In March 2014, the company’s board of directors announced that it would not be able to pay the interest coming due on the bonds. With the bond default, trading in the company’s shares on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange was suspended. Chaori entered a bankruptcy reorganization process, which was approved by the local Shanghai court in December 2014. At the time it entered the reorganization process, Chaori’s corporate bonds were held by 6300 bondholders, most of whom where individuals. 80 In order to ensure approval of the bondholders, two guarantors emerged to provide extra protection outside the reorganization process: China Great Wall Assets Management Corporation, wholly owned by the Chinese Ministry of Finance, and Shanghai Eternal Sunshine Investment Management Centre, apparently a shell company set up by the Shanghai local government two weeks before the reorganization plan was to be approved by creditors.81 The bondholders received full payment of principal, interest, and penalties for late payment. In the reorganization plan, eight private equity investors took control of the company. Subsequently it was revealed that behind layers of ownership, the private equity investors were all controlled by state-owned enterprises.82 Chaori thus presents a case in which bonds issued by a private enterprise were indirectly guaranteed by the central and local governments, after which control of the firm was effectively transferred to entities affiliated with the central government. Given the large number of individual bondholders involved, maintaining social stability is widely assumed to be the motivation for this high level of government involvement in the Chaori debt resolution.

The TMTF motivation also appears to apply to issuers that are not strategically important or particularly influential politically. A high-end restaurant chain called Beijing Xiangeqing Group, founded by a wealthy couple, had insufficient funds to make good on a redemption right on its 5-year unsecured Corporate Bonds issued in 2012. The firm’s business had grown rapidly but then suffered under the government’s anti-corruption campaign. An attempt to enter the technology field failed and ratings on the bonds were lowered from BB to CC. A trustee was appointed for the bondholders and eventually sufficient funds were marshalled by the issuer to pay the bondholders in full. But commentators suggested that the Xiangeqing bondholders never had to fear a haircut in this process because 60 per cent were individual investors.83

Limiting Cases: Other recent default crises in China suggest the limits of the no-default norm’s application. The first is an inter-SOE creditor squabble, in which all players are politically connected and the number of bondholders is small. On 21 April 2015, Baoding Tianwei Group Co., announced that it could not pay interest due on a large medium-term note. Tianwei, which operates in the electricity equipment industry and had ambitions to develop new energy (particularly solar) technologies, began as a local SOE. In 2008, it became a wholly owned subsidiary of China South Industries Group Corporation (CSGC), a central SOE. In 2011, Tianwei issued two medium-term notes in the amount of 2.5 billion RMB (US$375 million), which were rated AA+. But Tianwei had a history of known governance problems, including a series of investments lacking proper regulatory and internal approvals. At the end of 2014, Tianwei reported losses of 10 billion RMB, and it encountered loan repayment problems even before defaulting on the interest payment due under the note.

The Tianwei case is particularly interesting because the 12 note holders are all state-owned institutions, including large banks, as well as central SOEs under SASAC supervision. Tianwei’s default triggered a flurry of legal activity among the note holders, who pressed for, among other things, an unconditional guarantee of the note by Tianwei’s state-owned parent, CSGC. But CSGC refused to provide the funding necessary to rescue its subsidiary, and Tianwei has steadfastly rebuffed the demands of its creditors. For their part, the creditors did not relent: the finance company of the Baosteel Group (a central SOE under SASAC supervision) filed a lawsuit seeking immediate repayment of principal and interest on the two Tianwei MTNs it holds. In September 2015, Tianwei applied for reorganization through the bankruptcy process. It is striking that no smooth resolution could be found to this repayment crisis even though all of the players are SOEs under central government supervision. Why is the TCTF motivation not operative in this case? Tianwei’s bankruptcy filing may indicate that the government is beginning to accept the formal bankruptcy process as a mechanism to resolve corporate debt problems, at least where the direct fallout on Chinese citizens is minimal.84 Indeed, bankruptcy institutions may be viewed by state strategists as playing a valuable intermediary role in reaching solutions to repayment problems that would otherwise require thorny compromises among different state actors. It may also be seen as serving a needed disciplining function, particularly within the SOE system.

An interesting contrast with this case is the resolution of involuntary bankruptcy petitions filed by trade creditors of China National Erzhong Group Co. (CNEG) and its controlled subsidiary China Erzhong in September 2015, almost simultaneous to the Tianwei filing. CNEG is a wholly owned subsidiary of China National Machinery Industry Corporation (Sinomach). According to CNEG’s announcement, the two local bankruptcy courts’ acceptance of the involuntary filings would accelerate CNEG’s payment obligations under 1 billion RMB ($150 million) of MTN publicly traded in the interbank market and China Erzhong’s obligations under a 310 million RMB ($45 million) enterprise bond publicly traded in the exchange market. In contrast to the Tianwei case, the SOE parent of the issuers, Sinomach, offered to assume the two debt instruments in order to protect the creditors’ interests. The bankruptcy courts accepted the assignment and the debt instruments resumed trading.

What explains the contrasting outcomes in Tianwei and CNEG/China Erzhong? Clearly, they cannot be explained by the different risk of contagion posed by the defaults of the issuers. Neither case presented anything approaching systemic risk to China’s financial system. Rather, the explanation seems to lie in the attributes of the debt holders: whereas Tianwei’s debt was held by a small number of institutional investors, the debt of CNEG and China Erzhong was publicly traded. Coming on the heels of the stock market debacle in the summer of 2015, which seriously dented the reputation of China’s financial regulators, the CNEG/China Erzhong case offered the state the opportunity to purchase investor calm and a reputational boost at small cost.

The second limiting case is default on bonds issued in offshore markets. In these cases, although the issuer’s business operations are located in China, the firm is incorporated offshore (typically the British Virgin Islands or Cayman Islands), its stock is listed on a foreign exchange, and the bonds are held exclusively by foreign investors. There are numerous examples of defaults under this scenario, including Suntech Power, listed on the New York Stock Exchange,85 Ocean Grand Holdings, listed in Hong Kong,86 and China Milk Products, listed in Singapore.87 The most high-profile case is Kaisa Group Holdings, a real estate development company based in Shenzhen and listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. After its chairman resigned and several of its projects were blocked as the result of a party corruption investigation in 2014, the company was unable to pay its debts as they came due, including interest on a 7-year, dollar-denominated high-yield note issued in Hong Kong. A deal to transfer the founder’s controlling equity stake in the firm to a Hong Kong-listed company willing to negotiate repayment with bondholders fell through, and to date there is no resolution of Kaisa’s debt crisis.

At one level, it is unsurprising that the no-default norm does not adhere to offshore bonds. These cases involve only non-Chinese bondholders, so the social stability motivation of TMTF is not present. Moreover, all of the operating assets of the issuers are located in China, while the legal issuers of the debt are offshore companies—just pieces of paper and mailing addresses in the Caribbean. So with the major exception of the Chinese employees of these troubled firms, there is a firewall to separate the negative externalities of the default from China itself. Yet these defaults may have a serious impact on foreign investor sentiment towards securities issued offshore by Chinese firms, a consequence likely to be of considerable concern to the Chinese government.88 Thus, these cases support the impression that the no-default norm begins to unravel where direct domestic fallout is minimal and political support for the issuer has waned, either due to scandal (eg China Milk Products and Kaisa), or because the firm is an industry suffering from overcapacity (eg Suntech).

A key takeaway from this analysis is that corporate bond issues in China are subject not only to credit risk, but also to an unusual form of political/policy risk. That is, all else being equal, default is more likely among issuers that have fallen out of favour with the Communist Party, or whose industrial sector or business model is no longer a priority in the government’s economic strategy.

TBTF: None of the default episodes in the Chinese corporate bond market to date has presented a clear risk of contagion to the Chinese financial system. As we have seen, most of the cases have involved relatively small amounts of debt, and it is hard to imagine that the failure of any of the issuers would have seriously jeopardized the stability of major institutions in China’s banking or shadow banking system. Since the largest bond issuers are central SOEs in ‘pillar’ industries like power generation, oil, and mining, many of which enjoy monopoly power, it is almost inconceivable that default risk would arise or would not be mitigated by the state. As in the Japanese and Korean bond markets in their early developmental period, the Chinese government-supported no-default norm has thus far served to provide stability to a less than fully formed market. But as the Japanese and Korean experiences also vividly demonstrate, the no-default norm can mask significant bad debt problems and create serious weaknesses in the underlying credit culture that eventually lead to a financial crisis.89 To be sure, the potential for contagion in the event of widespread default in China’s corporate bond market does exist, perhaps particularly with respect to LGFV debt.

V. Discussion and Policy Implications

Having explored the formation and consequences of China’s state-centric corporate bond network, we now turn to policy implications. We motivate the discussion by first taking stock of China’s efforts to date to build a corporate bond market that functions as a spare tire for the financial system.

1. Assessment

The major economies in East Asia—Japan, Korea, and now China—have addressed the institutional challenge of developing a corporate bond market to supplement their bank-oriented financial systems in roughly similar ways. In each case, the nascent corporate bond market was launched with the largest and most important firms in the economy—firms working in industrial sectors that benefit from investment-driven, export-oriented economic policies and which by definition enjoy government support and ready access to bank finance. Implicit government guarantees at the early stage of market development were pervasive in all three systems. These implicit guarantees serve several functions in an institutional vacuum: First, they provide a form of investor protection in the absence of a robust corporate information disclosure and credit rating regime. Second, they serve as a device to control systemic risk by erecting a backstop behind corporate bond issuers, which is necessary given that the issuers are, as just noted, also major borrowers from banks. Third, they lower the cost of bond finance (at least for favoured firms), because issuer credit risk is essentially eliminated from the system.

The experience of all three countries also suggests the limitations inherent in this approach. Implicit guarantees distort the pricing mechanism, generate moral hazard, and stunt the growth of credit culture. The very institutional development needed to create a truly functional market is retarded in the shadow of the government’s informal backstop. Benchmarks to set yields have an artificial quality, credit ratings lack reliability, the secondary market lacks broad participation, and the bankruptcy regime is little used to resolve issuer distress. In this sense, the early corporate bond market development in the three countries did little to actually fulfil the ‘spare tire’ role. In fact, at least in Japan and Korea, it may have helped, indirectly, to set the stage for or exacerbate the serious financial crises experienced in these countries.

Despite broad similarities in approach and developmental trajectories of the market in these three countries, China’s corporate bond market is distinguished by what we have called state-centricity. Whereas the governments of Japan and Korea worked hand in glove with private institutions that had close relationships with financial regulators and line ministries, the Chinese approach has been to pervade the entire corporate bond market with state-owned and state-linked actors. The principal role for private actors in this market is as passive suppliers of capital to SOEs and LGFVs,90 mostly through the shadow banking system. Writing a decade ago, scholars Franklin Allen and co-authors ascribed China’s economic success, despite the weakness of its legal system and concomitant underdevelopment of its financial system, to the legacy of a Confucian relationship- and trust-based society that fostered alternative mechanisms to support the growth of the private sector.91 Since their paper was published, China’s corporate bond market has grown from virtually non-existent to the third largest in the world. Our network perspective has also focused on relationships as substitutes for formal institutions. But in the bond market, as in the corporate sector, the crucial relationships were established by and revolve around the Party-state. This Party-state-centric networking phenomenon, in our view, is a distinguishing characteristic of Chinese state capitalism.92

Two recurring themes seem to underlie all policy choices in the Chinese corporate bond market’s developmental history: strengthening state capitalism and maintaining social stability. The state’s tight control over the process of financial liberalization derives in part from its legitimacy concerns, but it also reflects confidence in the ability of economic regulators to manage the market—confidence that persisted until the stock market debacle in the summer of 2015. In the wake of that development, it seems fair to expect that concern for social stability will continue to drive policy choices in the bond market, as illustrated in the recent CNEG/China Erzhong case. Nonetheless, the Party-state is not a monolith, and rapid development, even within a tightly controlled market, breeds competing interests. The Tianwei case suggests the need for new dispute resolution mechanisms to mediate the opposing interests of different state actors. Moreover, the state cannot continue to rescue individual bond holders on an ad hoc basis indefinitely without risking serious moral hazard and other market distortions.93

The state capitalist approach has fostered tremendous growth in the issuance of corporate debt instruments, but it is not obvious that the consequences are favourable for China. The very entities that are underserved by the banking system and equity markets—POEs and SMEs—have benefitted the least from development of the corporate bond market. Instead, benefits have disproportionately flowed to the state sector: in fact, the principal role of the corporate bond market has been to supplement the loan market as a privileged financing channel for SOEs. It has played this role by providing even lower cost financing to SOEs than is available in the loan market and by creating a means of circumventing bank lending limits to favoured SOE borrowers. Meanwhile, the rapidly developing shadow banking system (discussed below), illustrates the limitations of the corporate debt market as a financing channel for SMEs. In short, instead of developing a competitive bond market with diverse products serving multiple classes of credit-worthy issuers, the Chinese government’s approach has been to prioritize SOE interests in a tightly managed market that is simultaneously massive in scale and seriously underdeveloped institutionally.

2. Policy issues

a. The Chinese corporate bond market as a spare tire?

Does the Chinese corporate bond market function as a spare tire, supplementing China’s banking system as an alternative financing channel, especially for firms not well served by banks, and as a means of diversifying risk away from the (mostly state-owned) banking sector? The analysis above strongly suggests a negative answer. In fact, state-centricity has compounded risk in the banking system and enhanced the privileged access to finance already enjoyed by state-owned firms.94 Moreover, recent reforms intended to alleviate China’s corporate debt problem, centred on debt–equity swaps, will present still more risk to Chinese banks, as they hold large amounts of corporate bonds.

If not a spare tire, what is the function of the Chinese corporate bond market as it has developed to this point? There appear to be multiple functions, including providing additional, low-cost financing to SOEs, bypassing bank regulations that impose limits on lending to individual firms, and channeling funds to local governments for investment projects. A likely byproduct of the growth of the corporate bond market, whether intended or not, is advancement of the interests of Party-state officials whose career prospects and/or opportunities for rent seeking are linked to the state sector. It may be too early to render a complete assessment of this market, however, bearing in mind its relatively short life to date and the hazards of measuring it against the standards of much older and more developed markets. In any event, whether the Chinese corporate bond market is capable of performing a spare tire function cannot be definitively judged in the absence of a banking crisis.

b. From network to market? The potential role for regulatory competition

Can a transition be made from a network comprised largely of state-owned and state-linked actors—one that principally has benefited those same actors—to a market that supplies accurately priced credit to firms on the basis of issuer fundamentals rather than ownership or industrial policy considerations; one that protects creditors through legal mechanisms rather than implicit state guarantees? Bond market reform of this sort confronts the fundamental dilemma at the heart of virtually all of the contemporary economic reform efforts in China, including the current ‘mixed ownership’ strategy for improving the performance of SOEs95: it requires the scaling back of state-owned entities as market participants and the transformation of the Party-state from network spider to neutral institution designer and enforcer.

Sources of private sector credit creation. Source: raw data collected from WIND (as of 30 June 2016), compiled by authors.

Yet the consequences of regulatory competition as currently playing out in the Chinese corporate bond market are ambiguous. Against the benefits of the PBOC’s efforts to liberalize the financial markets must be weighed the risks inherent in the expansion of short-term debt finance promoted by the PBOC’s jurisdiction over CP and MTN. The weighted average maturity of Chinese corporate debt has been declining with the mushrooming of CP issuances. It now stands at just 1.5 years, as compared to four years in 2011.97 As maturities decline, the danger of Chinese borrowers being unable to roll over the debt in the event of a shock to the economy, leading to a wide-spread seizing up of the credit markets—ie a Lehman episode with Chinese characteristics—cannot be dismissed.

c. Managing the decline of the no-default norm? The potential role for bankruptcy law

If a more fundamental transition in the corporate bond market is to take place, an important part of the process will be the carefully managed withdrawal of the state from the informal, often politically motivated, resolution of issuer distress. As we noted in the previous section, there are preliminary signs that Chinese policy makers are attempting to initiate this process. It may seem surprising that they chose to start within the SOE system itself. But this starting point has several advantages: (i) the prospect of social fallout is greatly reduced where the debt holders are state-owned institutions; (ii) orderly defaults will expose the SOE sector to badly needed market discipline, a major objective of the above-mentioned mixed-ownership reform strategy;98 and (iii) the process can be overseen by SASAC and party organs.

As the number and complexity of defaults expand, the orderly demise of the no-default norm would appear to require the emergence of a functional bankruptcy regime. China’s corporate bond market designers have long been conscious of the potential role for bankruptcy law.99 But a variety of closely related Party-state concerns have all but eliminated its functional role in the market. For one, Chinese courts are reluctant to accept bankruptcy petitions, even when properly filed, without a green light from local party officials.100 In part, this is because the potential for employee layoffs in bankruptcy implicates the social stability concerns previously discussed. Additionally, severe ideological resistance to, and public criticism of, ‘loss of state assets’ greatly complicates the valuation and sale of state assets in a reorganization process. Importantly, these concerns affect SOEs in all of their various roles in bankruptcy proceedings—as debtors, creditors and purchasers of assets. Thus, as long as state-linked actors continue to be the predominant players in all aspects of the corporate bond market, there would seem to be serious limitations on the role of the bankruptcy process as a pathway to the decline of the no-default norm. However, with the important exception of unemployment considerations, POEs are free of this baggage. If, as the recent data suggest, bond financing by POEs gains momentum, it is conceivable that the bankruptcy regime could begin to develop around private issuer defaults.

d. The implications of China’s shadow banking system

A potentially major complicating factor in managing a transition from network to market is China’s shadow banking system, which, like the corporate bond market, has grown exponentially since the global financial crisis. Moody’s Investors Service estimated that China’s shadow banking assets reached 41 trillion RMB ($6.3 trillion) by the end of 2014, representing 65 per cent of China’s GDP.101 Growth of the shadow banking system may generate significant benefits for the Chinese economy, by creating financing options for POEs and SMEs unable to access bank credit, and by providing higher returns to Chinese savers than those offered by the tightly regulated banking sector. For this reason, a recent Columbia Business School white paper suggests that ‘shadow banking is paving the way to market liberalization as the [Chinese] economy transitions from strict state ownership and control to a broader focus’.102 In a similar vein, a Brookings report suggests that while shadow banking is often negatively associated with regulatory arbitrage, ‘in an over-regulated economy with too large a State role, there can be societal benefits from such regulatory arbitrage. It can diminish the deadweight costs of inappropriate or excessive regulation and it can help force the pace of more comprehensive reforms’.103 At the same time, analysts have tended to downplay the risks posed by China’s shadow banking system in view of its relative simplicity and small size as compared to that of the US.

But the deep connection between China’s shadow banking system and its corporate bond market, a connection that is typically not analysed in detail, has implications both for the risks posed by the shadow banking system and its role in financial market liberalization. In fact, if shadow banking is broadly defined as non-bank intermediated finance, China’s corporate bond market is an integral part of the shadow banking system.104 Although the corporate bond market is itself highly regulated, as we discussed above, it is extensively leveraged by banks, SOEs, and LGFVs, all important players in the shadow banking system.