-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yajin Wang, Alison Jing Xu, Ying Zhang, L’Art Pour l’Art: Experiencing Art Reduces the Desire for Luxury Goods, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 49, Issue 5, February 2023, Pages 786–810, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac016

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

When consumers shop in luxury boutiques, high-end shopping malls, and even online, they increasingly encounter luxury products alongside immersive art displays. Exploring this novel phenomenon with both field studies and lab experiments, the current research shows that experiencing art reduces consumer desire for luxury goods. Three boundary conditions have been identified. The effect does not materialize in contexts in which the work of art is not experienced as art per se, such as when the work of art appears as decoration on the product or packaging or is processed analytically rather than naturally, and when luxury goods are not seen as status goods. We propose that experiencing art induces a mental state of self-transcendence, which undermines consumers’ status-seeking motive and consequently decreases their desire for luxury goods. This research contributes to the literature on consumer esthetics and has important practical applications for luxury businesses.

Art and luxury, at first glance, seem to be a perfect pairing. Art is a creative artisan activity that results in outcomes of esthetic and narrative appeal. Similarly, luxury has been defined as “expensive and exclusive products and brands that are differentiated from other offers based on their exquisite design and craftmanship, sensory appeal, and distinct socio-cultural narratives” (Wang 2021). Luxury firms thus seem to have good reasons to incorporate art into their businesses. In addition, art initiatives may attract attention, show corporate social responsibility, and enhance customer experience (Grassi 2019; Koenig 2017; Pine and Gilmore 1999; Schmitt 1999, 2003).

These benefits may be on managers’ minds when luxury firms are creating extensive retail environments (offline and online) in which consumers can experience art while shopping (see appendix A for select examples). However, is it effective to surround consumers with art when they shop in luxury boutiques, high-end shopping malls, and online? Exploring this new phenomenon of pairing art and luxury in retail environments empirically, we find that, counterintuitively, experiencing art (e.g., paintings, sculptures, and artistic photographs) reduces consumer desire for luxury goods.

This finding identifies an important consequence of art initiatives on luxury brands. For example, Louis Vuitton launched art gallery spaces next to or above its stores around the world and displays art next to handbags and leather goods on its website. Gucci displays art next to its products online and has integrated art exhibition rooms into its shopping environment at Gucci Garden in Florence. Well-known luxury department stores and malls in New York (Nordstrom), Paris (Galeries Lafayette Haussmann), Singapore (Marina Bay Shoppes), and Beijing (Parkview Green) have presented art shows. Beijing’s Parkview Green even hosts a permanent collection of more than 500 works of arts (mostly sculptures), claiming its mall “redefines luxury shopping” (http://www.parkviewgreen.com/eng/art/). However, based on our findings, these art initiatives may have unintended drawbacks.

We observe the robust effect that experiencing art diminishes consumer desire for luxury goods in two field studies and in a series of lab studies. The first field study shows that after viewing a real art exhibition, consumers were less interested in a nearby luxury shopping mall than a non-luxury mall. In the second field study, after viewing art in a mall, consumers were less interested in receiving promotional materials from luxury brands. In the lab studies, when consumers experienced visual art images (in contrast to non-art images that were equally esthetically appealing) or visual images that were framed as art (in contrast to the same images that were framed as non-art), they were less likely to choose luxury brands, and less interested in and less likely to purchase luxury products. We hypothesize that these findings occur because experiencing art induces a process of “self-transcendence,” which decreases the significance of the self and suppresses mundane thoughts, including concern about other people (Maslow 1969; Yaden et al. 2017). Self-transcendence, in turn, dampens the status-seeking motive that drives luxury consumption (Han, Nunes, and Drèze 2010; Ordabayeva and Chandon 2011). In our studies, we explore and delineate the phenomenon by showing when it occurs and when it does not. We find that the effect occurs only when art is really experienced as art. In contrast, the effect does not occur when art is experienced for other purposes, such as being strategically placed on the product or packaging for decoration or marketing purposes, or being processed analytically with a focus on technical details. The effect also does not occur when luxury goods are not framed as status objects. Finally, we present evidence that the core effect is mediated by self-transcendence. Overall, these results indicate that art—if experienced as l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake)—reduces the desire for luxury because art induces a state of self-transcendence in consumers, which suppresses their status-seeking motive.

Our research is the first to investigate whether, when, and how art in environments affects consumer desire for luxury products and thus complements prior literature on the effect of esthetics in product design, known as the art infusion effect (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a). We show that when art is experienced and appreciated as art, and not used strategically as decoration on the product or packaging (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b, 2009), it has the effect of reducing consumer desire for luxury. Finally, our research has practical relevance. Although a company’s decision to use art may be driven by multiple factors, practitioners need to be aware that when consumers experience art, it may undermine luxury consumption. Therefore, luxury firms should consider whether other positive benefits might outweigh this drawback before launching art initiatives in luxury stores.

THEORETICAL BACKGOUND

What is Art?

The perennial question “What is art?” has led to intense debates among scholars across a wide variety of disciplines, including history, anthropology, philosophy, and psychology. In general, art is associated with creativity and esthetics. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines art as “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects.” Similarly, Hagtvedt and Patrick (2008a, 380) view art objects as “skillful and creative expressions of human experiences, in which the manner of creation is not primarily driven by any other function.” Art also elevates viewers from everyday mundane pursuits to transcend their daily lives (Berlyne 1974; Joy and Sherry 2003; Wartenberg 2006).

Art spans a wide spectrum, ranging from visual art to music and dance. In this article, we focus exclusively on visual art, which includes painting, sculpture, photography, installations, and mixed media. In general, visual art can be classified as classic art (e.g., works from the Renaissance and Baroque periods to Impressionism), art from the modern period, and contemporary art. For modern and contemporary art in particular, social norms often determine what viewers consider to be art. That is, experts (art historians, curators, critics, and artists themselves) may declare works as art when an art object becomes part of a collection in a museum, gallery, or art-related event.

Because social norms determine, in part, what qualifies as art, we confine our investigation to stimuli that most consumers would clearly consider art (Hagtvedt 2020; Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b). Specifically in our studies, we feature classic and modern paintings by prominent artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Jan van Eyck, William Turner, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso as well as established contemporary sculptors and photographers. In addition, we do not present just one work of art in isolation; rather, our field and lab studies include displays of collections of art objects, which reinforces that the objects are indeed art rather than non-art objects. Finally, note that the focus of our research is not a particular artist, genre, or style. We are interested in how visual art in general—as an overall elevated expression of the human experience—affects individuals in their role as actual or potential luxury consumers.

The Influence of Art on Consumer Choice

A rich stream of consumer literature has examined how the visual processing of design influences product choices and preferences (Hoegg and Alba 2008; Wyer, Hung, and Jiang 2008). Different product design features such as physical size (Silvera, Josephs, and Giesler 2002), shape (Jiang et al. 2016), and attractiveness (Hoegg, Alba, and Dahl 2010; Wu et al. 2017) have been shown to affect consumer choice and consumption.

Of particular relevance to our study is the finding that the esthetic features of products can positively influence consumers’ perceptions and evaluations of these products and brands (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b; Lee, Chen, and Wang 2015; Schmitt and Simonson 1997; Townsend and Shu 2010). Importantly, associating a product with a work of art either directly (through product design) or indirectly (through packaging and advertising) can enhance the image and consumers’ evaluations of the product (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b; Townsend and Shu 2010). For example, a set of ordinary silverware with an image of Vincent van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night on top of the package can make the product seem more luxurious and result in more positive evaluations compared with the same silverware with a non-art picture on the package (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, study 1). Similarly, printing an art image on a soap dispenser can lead to a more positive perception of a brand extension (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008b). In sum, when the image of a work of art is presented as an integral part of the product (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, study 1) or is strongly associated with the product (e.g., in an advertisement, Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008b, study 1), consumers tend to have more positive reactions to the product and brand, presumably because of a positive “spillover effect.”

However, when works of art are experienced on their own as art for art’s sake, they may elicit responses that are different from seeing the image of a work of art printed on a product. The increasingly common presence of displaying art pieces in consumption-related environments such as retail malls thus raises the question of how art is experienced in this context and how it might affect luxury consumption. Next, we review literature on the psychological consequences of experiencing art and propose that art elicits the mental state of self-transcendence, which, we argue, reduces consumers’ status-seeking motive and, in turn, their desire for luxury goods.

Experiencing Art Elicits Self-Transcendence

The experience of visual art has been shown to evoke a wide range of emotions, including happiness, awe, sadness, and even anger and contempt (Cupchik et al. 2009; for a review, see Silvia 2005). Art, however, evokes more than emotions, given that it is one of the most profound human symbolic activities (Read 1965). Phenomenologically, the art experience differs from the esthetic experience because art extends beyond beauty to reflect the artist’s intentions, the work’s place in history, as well as political and social dimensions (Sibley 1965). Scholars have also contended that art appeals to people because of its figurative meaning (Babcock 1978; Holbrook and Hirschman 1993). In work on experiential consumption (Holbrook and Hirschman 1982, 1993), art has been singled out for its particularly rich and salient symbolic meaning.

Of particular importance to our research are philosophical ideas about art. As Kant (1790/1987) pointed out, the symbolic meaning of art interacts with people’s perceptions, intellect, and imagination, creating “disinterested interest,” which could be recast as “liking without wanting.” Art elevates the viewers from daily mundane life and compels them to face their own insignificance. As a result, neo-Kantian philosopher Cassirer (1944) argues that art symbolism elevates individuals to a mental state during which mundane matters are less concerning. Relatedly, Dewey (1934) argues that art elicits thoughts concerning issues beyond people’s everyday routines. In a consumer context, Venkatesh and Meamber (2006, 20) emphasize that “the consumer of art responds to it differently when compared to more mundane objects in life.” In short, art can induce a mental state where the mundane is less of a concern. In his esthetic theory, Beardsley (1958/1981, 1966) calls this state of mind “self-transcendence.”

Self-transcendence has been studied in cognitive, clinical, and social psychology (Frankl 1966; Haidt 2012; Koltlo-Rivera 2006; Piedmont 1999; Van Cappellen and Rime 2014). Self-transcendence can be experienced at different levels of intensity; at the extreme, it may encompass a sense of awe, elevation, and admiration (Haidt and Morris 2009; Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker 2012), similar to a “transcendent” or “extraordinary” experience (the Latin prefix extra referring to “outside” or “beyond”) (Arnould and Price 1993; Schouten, McAlexander, and Koenig 2007). This is consistent with early discussions of self-transcendence by Maslow (1969), who describes emotions associated with self-transcendence as a “peak experience.” As Maslow (1969) describes, the feelings during such moments are rich and often associated with complex expressions of wonder, amazement, awe, reverence, and humility.

The mental state induced by art also entails the fading away of the subjective sense of one’s self as an isolated entity; as a consequence, purely personal pursuits become less important (Koltlo-Rivera 2006; Levenson et al. 2005; Maslow 1969; Read 1991; Schwartz 1992). Maslow (1969) considers self-transcendence as the highest level of motivation (even beyond self-actualization), where an experience extends beyond the personal self and ego and seeks communion with the transcendent. Interestingly, neuroscientists who study art have also argued that art transcends thoughts of self-centered pursuits (Chatterjee 2014; Cupchik and Winston 1996; Dutton 2009). Therefore, the psychological state of self-transcendence suppresses mundane concerns including self-centered pursuits, self-interested related thoughts, and others’ opinions toward oneself (Cupchik and Winston 1996; Dutton 2009).

In sum, we argue that the art experience elicits a mental state of self-transcendence that, overall, decreases the significance of one’s sense of self (Bai et al. 2017). In doing so, the state of self-transcendence reduces the focus on one’s own desires and shifts attention away from the self (Haidt and Morris 2009; Maslow 1969, 1993), including decreased attention to others’ opinions of oneself and the desire for monetary gains (Antonucci 2001; Jiang et al. 2018; Loy 1996).

Having explicated the mental state of self-transcendence elicited by experiencing art, we next argue that self-transcendence inhibits consumers’ status-seeking motive, which is at the core of the desire for luxury consumption.

Self-Transcendence Undermines Consumers’ Status-Seeking Motive and Reduces the Desire for Luxury

Luxury goods are exclusive products offered at a premium price and quality (Fuchs et al. 2013; Nelissen and Meijers 2011; Patrick and Hagtvedt 2009; Wang 2021), and brands such as Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Prada, and BMW are widely viewed as prime examples (Berger and Ward 2010; Fuchs et al. 2013; Han et al. 2010). While luxury products may be sought for various reasons (e.g., quality, craftsmanship, or esthetic appeal; Wang 2021), one of the primary motivations driving luxury consumption is the desire to seek and display social status (Han et al. 2010; Nelissen and Meijers 2011; Ordabayeva and Chandon 2011; Veblen 1899). As a result, luxury products are promoted as status symbols, and consumer desire to obtain luxury goods and brands is largely driven by motivation for status and power (Dubois and Ordabayeva 2015). For example, people with a high need for social status usually show an enhanced desire for luxury goods (Han et al. 2010). Lack of status (e.g., induced by a sense of powerlessness) also leads to greater interest in luxury goods because such consumption can compensate for the feelings of powerlessness (Rucker and Galinsky 2008, 2009).

The status-seeking motive inherent in the desire for luxury is a self-centered motivation; that is, people highly prioritize their own interests and concerns (Maner and Mead 2010; Piff et al. 2010, 2012). Status-seeking, by nature, also includes a comparison of one’s own social rank with that of others and is driven by the desire to outrank others in society (Anderson, Hildreth, and Howland 2015; Dubois and Ordabayeva 2015). Given that self-transcendence, induced by experiencing art, decreases the significance of one’s self and suppresses mundane thoughts including concerns about other people, we expect that experiencing art should undermine self-centered status-seeking motivations and, in turn, the desire for luxury goods. We summarize our hypotheses and empirical works next.

HYPOTHESES AND OVERVIEW OF THE EMPIRICAL STUDIES

Our research is guided by three core hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 relates to the central phenomenon that we expect to emerge from our studies: experiencing art reduces consumer desire for luxury goods. Hypothesis 2 relates to the moderators of this phenomenon: we hypothesize that the effect proposed in hypothesis 1 occurs only when consumers experience and appreciate art as art per se and when the luxury good is perceived as a status good. When consumers experience art not as art for its own sake but for other purposes, or luxury products are not seen as status goods, the effect should be attenuated. Finally, hypothesis 3 proposes that self-transcendence can account for the phenomenon; that is, the effect occurs because experiencing art elicits the mental state of self-transcendence, which undermines consumers’ status-seeking motives.

We test these three hypotheses in eight studies, conducted both in the field and in the lab. In the first group of studies, we test the hypothesis related to the core phenomenon that experiencing visual art reduces consumer desire for luxury goods (hypothesis 1). We demonstrate this basic effect in three studies: two field studies (studies 1a and 1b) and one lab experiment (study 1c) in which we manipulate an art versus non-art experience by framing the same visuals differently. The second group of studies establishes boundary conditions through moderators (hypothesis 2). We show that the hypothesized negative effect of experiencing art on consumer desire for luxury diminishes when art is not experienced as purely art because the work of art offers instrumental value, such as decorating a product (study 2a); or the work of art is seen analytically and not naturally (study 2b); or the luxury firm positions the product not as a status product (study 2c). The final two studies provide evidence for the proposed psychological process (hypothesis 3). Study 3a shows that experiencing art induces self-transcendence, which, in turn, dampens consumer desire for luxury goods. Study 3b tests the full logical link that the art experience induces the mental state of self-transcendence, which in turn reduces the status-seeking motive and dampens the desire for luxury goods. In this study, we use a combination of moderation-of-process and measurement-of-mediation approaches in which we manipulate the absence of self-transcendence to eliminate the hypothesized effect and measure the status-seeking motive to establish a mediating role. Together, the final two studies provide evidence for the roles of self-transcendence and the status-seeking motive in mediating the effect of the art experience on desire for luxury goods.

STUDY 1A: ENCOUNTERING AN ART EXHIBITION REDUCES INTEREST IN A NEARBY LUXURY SHOPPING MALL

We begin our investigation into the effects of experiencing art on luxury consumption by examining whether encountering art as part of an exhibition can reduce consumer interest in luxury. This field study was conducted at a metro station in Shanghai, China, where London’s National Gallery was hosting a 30-day art exhibition in June 2018. We approached consumers who viewed the art exhibition as well as those who were unlikely to have viewed the art exhibition. We assessed their interest in luxury by comparing their choice to search for more information about a luxury mall or a non-luxury mall nearby.

Methods

Participants

Two research assistants were asked to approach approximately 150 participants over three days: 136 participants were successfully approached and completed the survey (Mage = 25.68, SD = 6.08, 67% female); 14 people declined to participate.

Procedure

The art exhibition, located near one of the exits of the metro station, displayed master paintings by Leonardo da Vinci, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and other artists on a 30-meter-long panel inside the South Shaanxi Road metro station in Shanghai (see exhibition details in appendix B and web appendix A). Two locations in the station were chosen as sites where the research assistants recruited participants. One location (the art condition) was next to the art exhibition panel on the way to the nearest exit. The research assistant was instructed to approach people who had stopped in front of the exhibition and looked at the paintings for some time. The other recruiting location (the control condition) was near a different exit where passengers were unlikely to have seen the panel. The two research assistants switched roles during the data collection period (see web appendix A for details). Participants were approached and asked if they would like to complete a short survey. People who agreed to participate completed the survey on iPads. After participating, they were thanked and received a small cash compensation.

Consumer Choice and Browsing Behavior

Participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to ask consumers for their opinions about shopping malls. Participants were asked to indicate their shopping preferences, and they were given descriptions of two nearby malls. To increase external validity, both malls were located within a 10-minute walk from the metro station. One of them is a luxury mall, carrying high-end brands such as Prada, Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Bulgari. The other is a mid-level mall, carrying affordable brands such as H&M, Calvin Klein Jeans, and Nike. Participants read short descriptions of each mall and then were asked to choose one of the two malls to get more information about it, including ongoing promotions. Clicking on the name of the chosen mall directed participants to the corresponding website, which constituted our main dependent measure. Participants browsed the website of the mall they chose for as long as they wanted, and then they proceeded to answer the remaining survey questions.

Manipulation Checks

After responding to the main dependent variable, participants answered a few manipulation check questions. First, they reported their perceptions of how luxurious the two shopping malls were (within-subject; 3-point scale: 1 = low end, 2 = middle level, 3 = high end). The results confirmed that participants perceived the luxury mall as more high-end and luxurious than the mid-level mall (M = 2.58 vs. 2.01, t(135) = 10.50, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.91). An additional manipulation check question asked participants to indicate whether they had seen the art exhibition. Consistent with our expectation, 98.6% of the consumers in the art condition had viewed the art exhibition, compared with 26.6% of the consumers in the control condition. Finally, participants were asked to provide demographic information, such as age, gender, and income level.

Results and Discussion

We tested hypothesis 1 by examining whether the likelihood of choosing to view the websites of the luxury shopping mall differed between the art and control groups. Consistent with our prediction, a chi-square test revealed that consumers in the art condition were less likely to choose to browse the website of the high-end luxury mall than the control condition (51.4% vs. 70.3%, χ2 (1) = 5.07, p = .024, OR = 0.45). Study 1a thus demonstrates the basic effect that experiencing art reduces consumer interest in luxury shopping.

One potential criticism of the design of study 1a is self-selection bias. That is, some consumers may have self-selected to view the art exhibition and therefore chosen the exit where the exhibition was located. These “artsy types” may be different from the other group, and they may be less interested in luxury to begin with. We attempted to minimize this bias by conducting the study in a busy subway station rather than in an art museum or gallery. Nonetheless, we conducted a second field experiment to better control for self-selection bias in the study design.

STUDY 1B: VISITING AN ART MALL REDUCES INTEREST IN PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL FROM LUXURY BRANDS

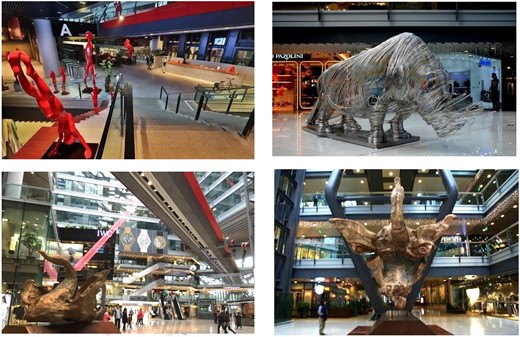

Study 1b serves three purposes. First, the field study provides additional external validity and shows the practical relevance of our phenomenon because the study was conducted in a real shopping environment. Two different shopping malls located close to each other were chosen as the settings. Both are equally luxurious but differ in whether they display art in the retail environment. One mall (the art mall) displayed works of art, whereas the other mall (the non-art mall) did not feature works of art at the time of study.

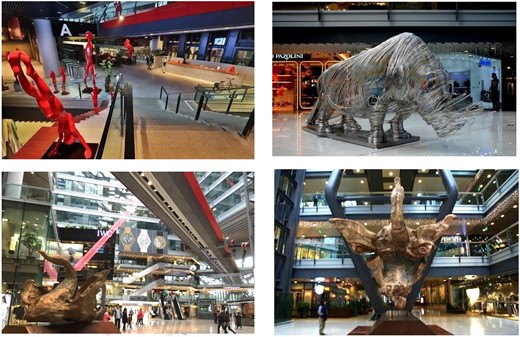

Second, the study extends our investigation from one form of visual art (i.e., paintings in study 1a) to a different form of visual art (i.e., sculptures in study 1b). Specifically, besides some paintings, the art mall primarily features more than 500 mostly modern and contemporary small and large sculptures. The sculptures are interspersed throughout the open spaces of the building, creating an artistic environment inside the mall.

Third, the study utilizes a design that controls for self-selection bias. Specifically, in the art mall condition, we approached shoppers either outside at the entrance of the art mall before they entered (control condition) or inside the mall after they had experienced art (experimental condition). In the non-art mall condition, participants did not experience art regardless of whether they were recruited outside or inside the mall, which provides two additional control conditions. We predicted that experiencing art inside the art mall should reduce consumer interest in luxury, compared with the three control conditions.

Method

Participants and Design

The field study used a 2 (type of mall: art mall vs. non-art mall) × 2 (location of study: outside the mall vs. inside the mall) between-subjects design. The study was conducted on different days during shopping hours by separate teams of research assistants who were blind to the hypothesis. We had planned to approach approximately 200 consumers for this study, and 206 consumers (Mage = 28.21, SD = 7.10, 57.3% female) were successfully recruited and completed the survey for a small monetary compensation.

Procedure

Beijing Parkview Green, the art mall, is known for exhibiting works of art such as sculptures (as well as some paintings) in the open spaces in the mall. The website (www.parkviewgreen.com/eng/art) states that “Art is Parkview Green’s most distinctive feature… Parkview Green will redefine luxury shopping and recreation, as visitors will have the opportunity to experience a truly artistic mall.” For the non-art mall, we selected a nearby shopping mall (The Kerry Center), which displayed no works of art at the time of the study (see appendix C for example pictures of both malls). The Kerry Center is a 10-minute walk from Parkview Green Mall. Both malls carry mid-level affordable brands as well as high-end luxury brands (see the manipulation check results) and attract the same clientele.

To manipulate whether shoppers had experienced art or not, the research assistants recruited participants at different mall locations. In the outside art-mall condition, the research assistants recruited shoppers before they entered the mall. In the inside art-mall condition, the research assistants recruited shoppers who were already inside and about to leave the mall to make sure they had experienced the art inside the mall. In the non-art-mall condition, shoppers were also approached either outside or inside the mall following the same instructions. All shoppers were asked if they would like to complete a short survey about their shopping preferences and habits. Participants completed the survey on iPads and received cash compensation.

Choice of Promotion Message

We showed participants a partial list of the brands sold in each mall. For each list, there were two sets of brands: the first set included affordable, mid-level brands (e.g., GAP and Fila), and the second set included high-end luxury brands (e.g., Van Cleef & Arpels and Dunhill). Participants were told that they could choose to receive promotional materials from either set of brands by clicking on their selected set. This choice served as the main dependent measure.

Manipulation Check

Participants answered questions on their perceived brand positioning of the mall (1 = low end, 2 = middle level, 3 = high end) and how artsy it was (“To what extent do you think this mall is artsy?” 1 = not at all, 7 = very much), among other filler items (e.g., “How do you like the decoration of this shopping mall?”). Finally, all shoppers were asked to provide demographic information and were thanked for their participation.

Results

Manipulation Check

Shoppers considered the two malls to be at a similar level of positioning (M = 2.54 vs. 2.44, F(1, 204) = 1.85, p = .175). Shoppers perceived the art mall as significantly more “artsy” than the control mall (M = 5.33 vs. 4.11, F(1, 204) = 46.43, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.95).

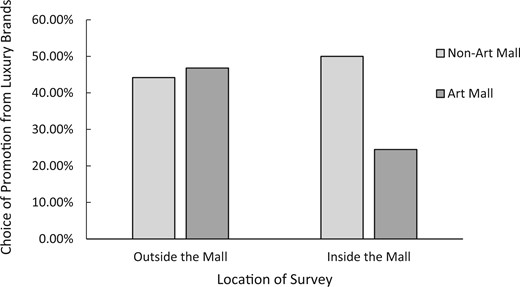

Choice

We examined the interactive effect of the mall type (art mall vs. non-art mall) and location of the survey (outside the mall vs. inside the mall) to determine how the art and non-art environments affected consumer preferences for receiving promotional materials from the luxury brands versus mid-level brands. A binary logistic regression revealed the predicted interaction (b = −1.23, SE = 0.58, Wald = 4.44, p = .035, OR = 0.29; figure 1); there were no main effects of the type of mall (b = −0.10, SE = 0.40, Wald = 0.07, p = .797) or location (b = −0.23, SE = 0.39, Wald = 0.35, p = .552). Confirming hypothesis 1, shoppers in the art mall were less likely to choose to receive promotions from luxury brands when surveyed inside the mall (24.5%) than outside the mall (46.8%, χ2(1) = 5.44, p = .02, OR = 0.37). However, for the non-art mall, no difference was observed between shoppers who were surveyed outside (44.2%) and inside the mall (50%, χ2(1) = 0.35, p = .55).

CHOICE OF PROMOTIONAL MESSAGES FROM LUXURY BRANDS BY THE TYPE OF MALL (STUDY 1B)

We also tested the simple effect of the mall type (i.e., art mall vs. non-art mall) at different survey locations (outside the mall vs. inside the mall). Among the shoppers surveyed outside the malls, there was no difference in the choice of luxury brands (Mart = 46.8% vs. Mnon-art = 44.2%, χ2(1) = 0.07 p = .797), minimizing the possibility of self-selection bias. However, among the shoppers who were surveyed inside the shopping malls, those in the art mall were significantly less likely (24.5%) to choose to receive promotional materials from luxury brands than those in the control mall condition (50%, χ2(1) = 7.41, p = .006, OR = 0.33), indicating that the experience of an art environment had an impact on their preference.

Discussion

The results of study 1b replicated the findings of study 1a in a real shopping environment and again supported hypothesis 1. We found that experiencing a shopping environment where works of art were prominently displayed significantly reduced consumer desire for luxury brands. Together, the two studies demonstrate the phenomenon that experiencing art reduces consumer interest in luxury in consumer-relevant field settings. Next, we provide causal evidence for the phenomenon in a controlled lab experiment. In this experiment, we also examine the effect with another art form (photography) and a new manipulation of the art versus non-art experience.

STUDY 1C: PHOTOGRAPHS FRAMED AS ART REDUCE INTEREST IN A LUXURY PRODUCT

In study 1c, we use photographic images as stimuli. We present them to participants online in a video clip, similar to how art has been presented on the websites of luxury brands. Most importantly, we frame the photographs as either art or non-art. By using the same visual images and framing them as art or non-art, we tightly control the content of the visuals and sensory engagement and simply vary whether participants perceive them as art or not. This is consistent with our theorizing: art must be perceived as art by consumers for the effect to occur.

Methods

Participants and Design

A total of 186 participants (Mage = 20.46, SD = 1.11, 64.6% female) from a public university in North America were recruited in exchange for partial course credit. They were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: framing visuals as art versus non-art.

Procedure

Participants came to the lab and were individually seated in private cubicles. They were told that the research section included two short unrelated studies. The first study involved a visual task where participants watched a 100-second video clip that contained six visuals. Using this procedure, the exposure time and content were identical for participants in all conditions. The visuals were photographs of plants by Karl Blossfeldt, a photographer and artist known for close-up photographs of plants and other living things. Participants in the art-framing condition read that the photographs were taken from an art book featuring a collection of artistic images of plants. They also read that the artist is known for his acute sense of the exquisite and sublime beauty of plants. In the non-art-framing condition, participants read that these photographs were from a botany book that documents a collection of botanical images of plants, and the botanist is known for his accurate documentation of horticultural and floral features of the plants (for detailed manipulations, see appendix D). Using this procedure, we ensured that while participants saw the exact same photographs for the same length of time, they experienced the visuals either as art or non-art.

Next, participants moved to a second ostensibly unrelated study in which their interest in luxury goods was measured. They evaluated the LV Pochette Jour, a product by the brand Louis Vuitton, which can be used as a clutch, laptop holder, or document portfolio (see web appendix B for visuals). Participants were asked to evaluate the product on three attitude items (e.g., “I think the product is: unfavorable = 1, favorable = 7; negative = 1, positive = 7; unpleasant = 1, pleasant = 7”). The average of the three items formed the main dependent measure (α = 0.89).

Manipulation Pretests

To ensure that the manipulation of framing the images as art or non-art would lead participants to perceive them differently, a separate sample of 202 participants from Mturk (Mage = 35.65, SD = 10.28, 41.9% female) was randomly assigned to read the art or non-art framing instructions for the six photographs. After viewing each photograph, they rated how artistic the photographs were on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). The results revealed that participants rated the photographs in the art-framing condition as significantly more artistic than visuals in the non-art-framing condition (average score of the six images: Mart = 5.61 vs. Mnon-art = 5.20, F(1, 200) = 10.61, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.05).

Results and Discussion

We predicted that viewing visuals framed as art (vs. non-art) would reduce interest in the Louis Vuitton product. The results confirmed our prediction; participants in the art-framing condition evaluated the LV Pochette Jour less favorably than those in the non-art-framing condition (Mart = 3.88, SD = 1.20 vs. Mnon-art = 4.25, SD = 1.20, F(1, 184) = 4.50, p = .035, ηp2 = 0.024). This result once again supports hypothesis 1 that experiencing art dampens the desire for luxury goods.

In sum, in the first group of three studies (two field studies and a lab experiment), we have established the phenomenon that experiencing art reduces consumer desire for luxury. All the results support hypothesis 1. In the next group of three experimental studies, we further examine the phenomenon by identifying boundary conditions of the effect. Following hypothesis 2, we predict that the effect occurs only when art is experienced as art per se and when the luxury good is perceived as a status good. However, we expect the effect to be attenuated when art is experienced for other purposes (such as being part of product packaging or being viewed with a focus on the technical details) or when the luxury good is presented as a non-status good.

STUDY 2A: ART IN THE ENVIRONMENT (BUT NOT ON PACKAGING) REDUCES INTEREST IN A LUXURY PRODUCT

In the studies reported above, participants experienced art by appreciating art per se. In this study, we test what happens when art appears as part of a luxury product or merchandise (e.g., on the packaging or on a shopping bag) versus when art is in the environment around the product. Indeed, luxury brands often incorporate art images strategically into their products to make them more appealing. For example, Louis Vuitton collaborated with contemporary artist Jeff Koons to put images of works of art on luxury bags and backpacks. Similarly, Hermès printed the work of artists on its scarves.

When art becomes part of a commercial product, the purpose is not solely to appreciate art per se. In the words of philosopher and art critic Benjamin (1935/1968), art loses its “aura” when it is reproduced for a commercial purpose. Art is then not only experienced as art for its own sake but also as a product attribute. As a result, the elevated mental state of self-transcendence is unlikely to occur and the negative effect on consumer interest in luxury should not be observed. Study 2a tests this boundary condition.

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 193 participants (Mage = 20.21, SD = 2.51, 44% female) from a public university in North America were recruited for this study in exchange for partial course credit. They were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: art on the package versus art in the environment versus the control. The control condition, which did not include exposure to art, was used to assess the baseline evaluation of the target luxury product.

Procedure

Participants came to the lab and were individually seated in private cubicles. They were told that the research session was to gather their thoughts about certain luxury brands and products. In the art on the package condition, they were told that Louis Vuitton “plans to introduce new packaging that incorporates the visuals of some famous paintings into the design.” Next, they were presented with a series of “newly designed Louis Vuitton packages.” We hired a professional advertising agency to design eight Louis Vuitton package boxes, each with a classic painting on the lid (e.g., Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh; see appendix E for visual examples and web appendix C for full materials). In the art in the environment condition, participants were told that Louis Vuitton “plans to host an art exhibition in its flagship store” and were then asked to view some of the paintings that might be included in the exhibition. The same eight paintings as those used in the art on the package condition were presented to participants. In both conditions, participants spent as much time as they wanted looking at the packages or the paintings in the art exhibition. Finally, in the control condition, participants did not see any visual stimuli.

Dependent Measures

Participants evaluated an LV Pochette Jour product that can be used as a clutch, laptop holder, or document portfolio (see web appendix C for visuals). The product was displayed next to a Louis Vuitton box. Participants in the art on the package condition saw the package box with an art image printed on it (one of the same package boxes they saw earlier). Participants in the other two conditions saw a regular Louis Vuitton box without art images. Next, participants were asked to evaluate the product on five items (e.g., “I think the product is: unfavorable = 1, favorable = 7; negative = 1, positive = 7; bad = 1, good = 7; unpleasant = 1, pleasant = 7; How much do you like this product?: dislike very much = 1, like very much = 7”). The average of the five items formed the main dependent measure (α = 0.96).

Finally, participants in the art on the package condition were asked how much they enjoyed viewing the packages and how much they liked the idea of including the paintings on the package. Similarly, participants in the art in the environment condition were asked how much they enjoyed viewing the paintings as part of the art exhibition in the flagship store and how much they liked the idea of including them in the art exhibition. Finally, they rated the luxuriousness of the product on four 7-point items from Hagtvedt and Patrick (2008a).

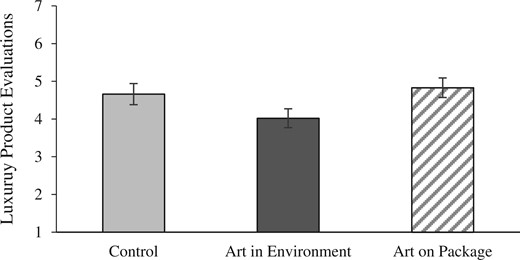

Results

Luxury Product Evaluations

A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of treatment conditions on the luxury product evaluations (F(2, 190) = 5.82, p = .004, ηp2 = 0.06; figure 2). A series of planned contrasts was performed to test our predictions. First, participants in the art in the environment condition showed significantly less interest in the luxury product (M = 4.02, SD = 1.47) than participants in the control condition (M = 4.66, SD = 1.47, F(1, 190) = 6.46, p = .012, ηp2 = 0.03). This replicated our main finding that experiencing art as art per se reduces consumer interest in luxury goods, supporting hypothesis 1. Moreover, consistent with our prediction, participants in the art in the environment condition (M = 4.02, SD = 1.47) also indicated significantly lower interest in the luxury product than those in the art on the package condition (M = 4.83, SD = 1.35, F(1, 190) = 10.47, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.05). Finally, product evaluations in the art on the package condition were non-significantly higher than those in the control condition (F(1, 190) = 0.48, p = .49, ηp2 = 0.003). This pattern of results provided important evidence for our conceptualization and supported hypothesis 2 by suggesting that (1) experiencing art only caused the hypothesized effect when it is experienced as art and (2) when art becomes part of product packaging, it has no impact on consumer interest in luxury products. Importantly, our findings also add nuance to prior research that demonstrated that adding art to product packaging enhances the appeal of a product due to the increased perception of luxuriousness (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a). To show this effect, prior research examined non-luxury products. In contrast, in the present study, the art was added to a luxury product. Our results show that including art images on the package of a luxury product only directionally increases the attractiveness. This limited positive effect likely occurred because the product was already a luxurious product and thus the perceived luxuriousness could not easily be further increased. Therefore, reconciling our findings with previous research, we suggest that incorporating art images on packages has a much greater positive effect for non-luxury products than luxury products.

ART IN ENVIRONMENT VERSUS ART ON THE PRODUCT PACKAGING (STUDY 2A)

ANALYTIC VIEWING OF ART DIMINISHES THE NEGATIVE INFLUENCE OF THE ART EXPERIENCE ON LUXURY (STUDY 2B)

In addition, we found that participants reported similar levels of enjoyment viewing the art on the package and viewing art in the environmental (M = 5.13 vs. 5.14, F(1, 127) = 0.003, p = .96). Participants also liked the idea of including art in the store environment as much as they liked the idea of including art on the packaging (M = 5.02 vs. 5.38, F(1, 127) = 1.85, p = .18). Moreover, they judged the product to be equally luxurious in all conditions (M = 4.84 vs. 5.04 vs. 5.21, F(2, 190) = 1.13, p = .33, respectively, for the environment, package, and control conditions). However, participants evaluated the products less positively when art was prominently featured in the environment, which is consistent with hypothesis 2.

STUDY 2B: VIEWING ART NATURALLY (BUT NOT ANALYTICALLY) REDUCES INTEREST IN BUYING LUXURY CLOTHES

Our conceptualization posits that experiencing art reduces consumer desire for luxury goods because appreciating art per se elicits a sense of self-transcendence. We argue specifically that the symbolic meanings of art lead to this mental state during which mundane matters are less concerning. Prior research indicates that different processing styles might affect how people experience art (Liberman and Trope 1998). Therefore, we expected that self-transcendence may be interrupted when art is processed in particular ways. In study 2b, we asked participants to either view and appreciate art naturally or to analyze works of art by paying specific attention to the technical elements, such as lines and colors. We expected that viewing a work of art analytically (i.e., by focusing on the technical details of the work of art rather than appreciating it naturally as a whole in terms of the symbolic meaning) should eliminate the negative effect on consumer interest in luxury goods.

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 167 participants (Mage = 20.16, SD = 1.21, 58.2% female) from a public university in North America participated in the experiment in exchange for partial course credit. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions of a 2 (visual stimuli: art vs. non-art) × 2 (viewing mode: natural vs. analytical) between-subjects design.

Procedure and Measures

Participants were randomly assigned to a visual task in which participants viewed 10 images (either art or non-art visual images) on a desktop computer. In the art conditions, participants saw images of 10 well-known paintings (e.g., Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh). Each of the images appeared in the center of a 21-inch desktop screen with a full-screen display. Participants could view each image for as long as they wished and then click to see the next image. In the non-art control conditions, 10 photographs included matching colors and topic themes (consistent with Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008b, see web appendix D for examples of the experimental stimuli).

In the natural viewing conditions, participants viewed the 10 visuals without additional instructions. In contrast, in the analytic viewing conditions, participants were asked to evaluate the lines and colors of each of the same 10 visuals in detail. Specifically, they were asked to rate each picture on a 7-point scale for the following two items: (1) “How much do you like the color of this picture?” and (2) “How much do you like the lines of this picture?”

Next, participants were presented with a second ostensibly unrelated study where we measured their interest in luxury goods. Participants were asked to imagine that they were considering buying clothes and to separately rate their interest in “high-end, expensive brands” and “mainstream, affordable brands” (1 = Not at all interested, 7 = Extremely interested).

Included at the end of the survey were debriefing questions asking participants to guess the purpose of the study. None of the participants saw a connection between their viewing of visuals and their interest in different brands, and none guessed the hypothesis that viewing art would lead to less interest in luxury brands. Therefore, the observed negative effects of art experience on interest in luxury goods were not due to demand characteristics.

Manipulation Pretest

To ensure that the art and non-art conditions were perceived as similar in their esthetic value but different in their artistic value, a separate sample of 168 participants (Mage = 20.36, SD = 2.82, 49.4% female) from the same population was randomly assigned to view the computer images of 10 visuals of the paintings or the 10 non-art visuals. Participants rated the pictures on (1) “How artistic are these pictures?”; (2) “How esthetic are these pictures?”; and (3) “How much did you appreciate the overall beauty of these pictures?” Responses were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all to 7 = very much). The results revealed that participants rated the visuals in the art condition as significantly more artistic than the visuals in the control condition (M = 6.14 vs. 5.11, F(1, 166) = 28.51, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.15). However, they rated the art visuals and non-art visuals as being similar in esthetics (M = 5.58 vs. 5.45, F(1, 166) = 0.50, p = .48) and overall beauty (M = 5.44 vs. 5.36, F(1, 166) = 0.15, p = .70).

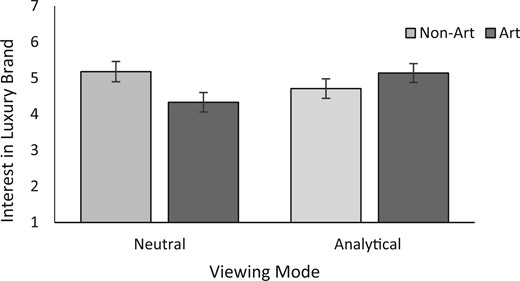

Results and Discussion

First, an ANOVA with interest in luxury brands as the dependent measure revealed a significant interaction between the visual type (art vs. non-art) and viewing mode (natural vs. analytical), F(1, 163) = 5.31, p = .022, ηp2 = 0.032). There was no main effect of the visual type (F(1, 163) = 0.56, p = .45, ηp2 = 0.003) or main effect of the viewing mode (F(1, 163) = 0.37, p = .54, ηp2 = 0.002). To decompose this interaction, we conducted a series of pairwise comparisons (figure 4). Specifically, when art was viewed naturally, viewing art (Mart = 4.33, SD = 1.97) significantly reduced participant interest in luxury brands compared with participants viewing non-art visuals (Mnon-art = 5.18, SD = 1.75, F(1, 163) = 4.58, p = .034, ηp2 = 0.027). This result replicated the findings of previous experiments and supported our hypothesis 1. However, when participants were instructed to analyze the technical elements of the visuals, viewing art (Mart = 5.14, SD = 1.62) did not affect participants’ interest in luxury brands compared to viewing the non-art condition (Mnon-art = 4.71, SD = 1.76, F(1, 163) = 1.23, p = .27, ηp2 = 0.008). Finally, viewing art naturally (M = 4.33, SD = 1.97) significantly reduced participants’ interest in luxury brands compared to viewing art analytically (M = 5.14, SD = 1.62, F(1, 163) = 4.37, p = .038, ηp2 = 0.026).

THE MODERATING ROLE OF STATUS POSITIONING OF LUXURY GOODS (STUDY 2C)

Next, the parallel analysis was conducted using interest in non-luxury brands (i.e., mainstream affordable brands) as the dependent variable. The results showed that there was no significant interaction (F(1, 163) = 2.32, p = .13). There was no significant main effect of the visual type (F(1, 163) = 0.03, p = .87), and no significant main effect of the viewing mode (F(1, 163) = 0.06, p = .80).

In sum, study 2b replicated the effect that viewing art reduces consumer interest in luxury products (hypothesis 1). However, when consumers analyzed the technical details of the work of art rather than experience it as art per se, the negative impact on interest in luxury goods was eliminated. These results support hypothesis 2.

In this study, participants independently rated their interest in high-end luxury brands and their interest in mainstream affordable brands, which allowed us to evaluate the influence of the art experience on both luxury and non-luxury brands separately. The lack of an effect on participant interest in non-luxury brands suggests two conclusions. First, although the art experience decreases consumer interest in luxury brands, it does not enhance consumer interest in non-luxury brands. Second, the art experience does not affect consumer interest in shopping, in general. Rather, the art experience only affects consumer response to luxury brands.

STUDY 2C: ART REDUCES INTEREST IN LUXURY ONLY WHEN THE LUXURY PRODUCT IS POSITIONED AS A STATUS SYMBOL

In study 2c, we examine yet another boundary condition of the effect. Based on our conceptualization, enhanced self-transcendence (caused by experiencing art) reduces consumers’ status-seeking motives, which then leads to reduced desire for luxury goods. One important assumption underlying this line of reasoning is that luxury goods are primarily perceived as status symbols. Although this assumption seems to be well supported (Wang 2021), luxury products are sometimes not positioned as status symbols. Instead, they can be positioned, for example, in terms of their artistry and creativity. When luxury products are positioned on characteristics other than as a status symbol, the proposed negative effect of the art experience on consumer desire for luxury should diminish. In study 2c, we manipulate the brand positioning of a luxury product (status vs. artistic positioning) and assess the moderating role of status positioning.

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 294 undergraduate students from a large public university in North America participated in the study in exchange for partial course credit. They were randomly assigned to one of four conditions in a 2 (visual stimuli: art vs. non-art) × 2 (luxury brand positioning: status positioning vs. artistic positioning) between-subjects design.

Procedure

As in the prior experimental studies, participants came to the lab, were seated in individual cubicles, and were told that the study had two unrelated parts. Participants first viewed either 10 art or non-art visuals, as in study 2b. In the art condition, participants saw images of 10 well-known paintings (e.g., Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, see web appendix D). In the non-art control condition, participants viewed 10 photographs with the same colors and topic themes as the paintings. Next, participants moved on to an ostensibly unrelated study and evaluated an advertisement for a collection of Gucci sneakers, based on the cover story of helping the experimenter learn about consumer preferences for luxury products. In the status positioning condition, there were three posters of Gucci’s “exclusive sneaker collection.” The text on the posters read “The collection features an exclusive and high-end mix of contemporary colors, materials and designs,” with a prominent slogan, “With our exclusive collection of sneakers, we invite you to immerse yourself in a world of prestige, distinctiveness, and deluxe appeal.” In the artistic positioning condition, the three posters had identical images but the text had different slogans. Specifically, Gucci’s “artistic sneaker collection” featured “an artistic and creative mix of contemporary colors, materials and designs,” with the prominent slogan, “With our artistic collection of sneakers, we invite you to immerse yourself in a world of artistry, creativity, and sensory appeal” (see web appendix E for the experiment details). Participants then evaluated the Gucci sneakers on three items on a 7-point Likert scale (e.g., “To what extent do you find Gucci’s sneakers appealing?”; “To what extent do you like Gucci’s sneakers?”; and “How likely are you to purchase a pair of Gucci’s sneakers?”). The average of the three items formed the main dependent measure (α = 0.89).

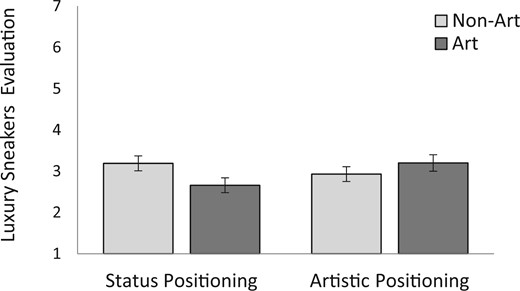

Results and Discussion

The 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between the type of visual stimulus and luxury brand positioning (F(1, 290) = 4.64, p = .032, ηp2 = 0.016). As shown in figure 4, in the status positioning condition, viewing the art visuals significantly reduced the appeal of the luxury sneakers (Mart = 2.66, SD = 1.38) compared with viewing the non-art visuals (Mnon-art = 3.19, SD = 1.74, F(1, 290) = 4.26, p = .04, ηp2 = 0.014). However, in the artisitic positioning condition, participants who viewed the art versus non-art visuals rated the luxury sneakers as equally appealing (Mart = 3.20, SD = 1.62 vs. Mnon-art = 2.93, SD = 1.57), F(1, 290) = 1.00, p = .32, ηp2 = 0.003).

Study 2c provides evidence showing that the status-seeking motive is a key component in explaining the negative effect of the art experience on luxury interest. Experiencing art leads to reduced interest in luxury only when luxury is positioned as a status symbol. In contrast, when luxury is not positioned as a status symbol, experiencing art has no impact on consumer interest.

In sum, the results of the three preceding studies support both hypotheses 1 and 2. Results indicate that the negative effect of art on consumer desire for luxury goods occurs only when art is experienced as art and not for other purposes, and when luxury products are perceived as status goods. In the final two studies, we present evidence for the underlying mechanism proposed in hypothesis 3. We first provide evidence for the mediating role of self-transcendence and then test the full causal link that the art experience induces self-transcendence, which decreases the status-seeking motive and reduces the desire in luxury goods.

STUDY 3A: THE MEDIATING ROLE OF SELF-TRANSCENDENCE

In study 3a, we examine the role of self-transcendence in linking the art experience to a reduced interest in luxury. One important instantiation of self-transcendence is the diminished significance of self, or what Bai et al. (2017, 187) refer to as the “small self” or “diminished perceived self-size.” Accordingly, we expect that experiencing art induces consumers to perceive themselves as less significant (Haidt and Morris 2009; Koltlo-Rivera 2006). In study 3a, we capture the mental state of self-transcendence by assessing people’s perceived self-size, thereby testing the mediating role of self-transcendence between the art experience and reduced interest in luxury.

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 400 people participated on Prolific (Mage = 30.08, SD = 9.44, 49.3% female) in exchange for a small monetary compensation. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (visual stimuli: art vs. non-art).

Procedure and Measures

Participants viewed similar visual images to study 2b. In the art condition, participants saw images of 10 well-known paintings (e.g., Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh). In the non-art control condition, they viewed 10 photographs with similar colors and topic themes to the paintings. Next, participants were presented with an ostensibly unrelated study where we measured their perceived significance of the self. Specifically, participants were shown a picture with seven different sizes of signatures and told to imagine that they were going to sign this picture. They were asked which size of signature would best represent them (see web appendix F for visuals, adapted from Bai et al. 2017). This measure has been validated in prior research as an assessment of people’s subjective perceptions of the significance of the self (Bai et al. 2017). Finally, we measured interest in luxury goods in yet another ostensibly unrelated task. Participants evaluated the LV Pochette Jour (see web appendix G for visuals). Participants were asked to evaluate the product using three items (e.g., “I think the product is: unfavorable = 1, favorable = 7; negative = 1, positive = 7; unpleasant = 1, pleasant = 7”). The average of the three items formed the main dependent measure (α = 0.91).

Results and Discussion

First, as in the prior studies, a one-way ANOVA indicated that experiencing art decreased the evaluation of the luxury product compared to experiencing the non-art condition (Mart = 3.78, SD = 1.51 vs. Mnon-art = 4.16, SD = 1.47; F(1, 398) = 6.38, p = .012, ηp2 = 0.016), again supporting hypothesis 1.

Next, we analyzed the significance of the self as a function of the art versus non-art conditions. Consistent with our prediction, the results showed that participants in the art condition reported a less significant sense of self (M = 2.66, SD = 1.71) than participants in the non-art condition (M = 3.01, SD = 1.70, F(1, 398) = 4.21, p = .041, ηp2 = 0.010).

Finally, a 10,000-resample bootstrap (Hayes 2018, model 4) revealed an indirect effect of experiencing art on evaluation of the luxury product via perceived significance of the self (b = −0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.1618, −0.0019]). This analysis confirmed that the effect of experiencing art on interest in luxury was statistically mediated by the decreased significance of self, supporting hypothesis 3.

STUDY 3B: ART INDUCES SELF-TRANSCENDENCE AND THEN REDUCES STATUS-SEEKING AND INTEREST IN LUXURY

In the final study, we test the full causal link of our conceptualization: the art experience induces self-transcendence, which decreases the status-seeking motive and thus reduces the desire for luxury goods. We test this proposed psychological process through a combination of a moderation-of-process approach and a measurement-of-mediation approach. Specifically, we experimentally inhibit the induction of self-transcendence by shielding participants from it and also measure the status-seeking motive. We expect that when feelings of self-transcendence are inhibited, the negative effect of experiencing art on consumer desire for luxury goods should disappear.

Methods

Participants and Design

A total of 287 participants (Mage = 21.72, SD = 1.64, 62.1% female) from a public university in North America were recruited in exchange for extra course credit. One participant’s survey was recorded with an error and therefore was excluded leaving 286 valid responses in the final analysis. They were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions in a 2 (visual stimuli: art framing vs. non-art framing) × 2 (self-transcendence: shielded vs. control) between-subjects design.

Procedure

Participants came to the lab and were individually seated in private cubicles. They were told that the research session included three short, unrelated studies. Participants in the self-transcendence shielding condition were first asked to complete a survey from the career center to better understand college students’ ability to express their opinions by providing arguments on issues. As part of the survey, participants were asked to write a few sentences to support three statements, which were designed to counteract self-transcendence by getting participants to focus on mundane matters and become concerned about others’ opinions of themselves. The statements that participants were asked to support were: (1) “My sense of self often depends on other people and things”; (2) “I am often bothered by everyday mundane matters”; and (3) “I am concerned about others’ opinion of me.” These items were adopted from prior research (Levenson et al. 2005). Participants in the self-transcendence control condition did not complete this task.

Participants were then told that the second study involved a visual task. In this task, participants saw a 100-second video clip that contained six visuals by Karl Blossfeldt that were either framed as art or non-art. As in study 1c, participants in the art-framing condition read that the photographs were taken from an art book featuring a collection of artistic images of plants; whereas in the non-art-framing condition, participants read that these photographs were from a botany book that documents a collection of botanical images of plants (for detailed manipulations, see appendix D).

After viewing the visuals, participants proceeded to complete an unrelated study in which their status-seeking motive was measured with the need for status scale (adapted from Eastman, Goldsmith, and Flynn 1999). Three items were included (α = 0.88): “I would buy a product just because it has status”; “I am interested in new products with status”; and “I would pay more for a product if it had status” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Finally, participants moved to the third unrelated study, in which their desire for luxury goods was measured. We showed participants a map of an ostensibly new mall (see web appendix H for details). On the map, there were eight luxury brand stores (Nordstrom, Bloomingdales, Neiman Marcus, Louis Vuitton, Prada, Burberry, Giorgio Armani, and Tiffany & Co.) and eight non-luxury brand stores (Macy’s, Sears, J.C. Penney, Gap, J.Crew, H&M, Zara, and Claire’s). We conducted a separate pretest to confirm that the eight luxury stores were indeed perceived as more luxurious than the eight non-luxury stores (web appendix I). Participants were asked to indicate which stores they would like to visit if they were to visit the mall. They could choose as many or as few stores as they wanted. For each participant, we calculated the number of luxury stores they had chosen to visit as the main dependent measure.

Manipulation Pretests

To ensure that the self-transcendence shielding condition could inhibit self-transcendence, a separate sample of 152 university student participants (Mage = 21.21, SD = 1.74, 26.4% female) were randomly assigned to the self-transcendence shielding and control conditions, which was similar to the main study. After the self-transcendence shielding manipulation, participants rated five statements adopted from the self-transcendence scale developed by Levenson et al. (2005): “I have become less concerned about other people’s opinions of me”; “I feel that my individual life is a part of a greater whole”; “My sense of self is less dependent on other people and things”; “I feel that my life has more meaning”; and “I find more joy in life.” Participants indicated their level of agreement with each statement on a 7-point scale (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree, α = 0.70). The results showed that participants in the self-transcendence shielding condition reported a significantly lower level of self-transcendence than participants in the control condition (M = 4.84 vs. 5.13, F(1, 150) = 4.36, p = .039, ηp2 = 0.03).

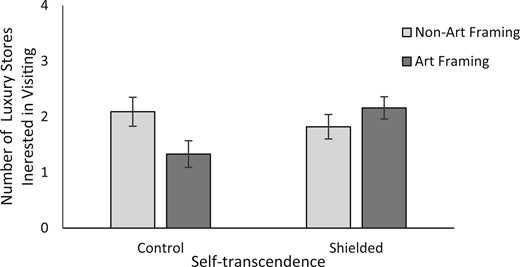

Results and Discussion

Interest in Luxury

We predicted that in the self-transcendence control condition, viewing visuals framed as art (vs. non-art) would reduce participants’ interest in visiting luxury stores. However, shielding the formation of the self-transcendence state should eliminate this effect. To test this interaction, we analyzed the number of luxury stores that participants wanted to visit as a function of visual stimuli framing (art framing vs. non-art framing) and self-transcendence shielding (shielding vs. control). The results revealed a significant interaction (F(1, 282) = 5.06, p = .025, ηp2 = 0.02; figure 5). There was no significant main effect of the visual type (F(1, 282) = 2.06, p = .15), and no significant main effect of the self-transcendence shielding manipulation (F(1, 283) = 0.90, p = .34).

Louis Vuitton Official Website

Louis Vuitton Pop-Up Store on Madison Avenue, NYC

Gucci New Wooster Store in Soho, New York City: Art Theater in the Retail Store

Galeries Lafayette Haussmann, Paris

Works of art at the exhibition at South Shaanxi Rd. Metro Station in Shanghai from The National Gallery, London, from June 1, 2018--June 30, 2018

Examples of sculptures in the art mall

Pictures of the non-art mall

Visuals used in the experiment (photos by Karl Blossfeldt)

SELF-TRANSCEDENCE SHIELDING DIMINISHES THE NEGATIVE EFFECT FROM EXPERIENCING ART TO LUXURY (STUDY 3B)

To decompose this interaction, a series of pairwise comparisons were conducted. In the self-transcendence control condition, in which self-transcendence was not shielded, participants in the art-framing condition chose to shop fewer luxury stores than those in the non-art-framing condition (Mart = 1.33, SD = 1.24; Mnon-art = 2.09, SD = 1.96), F(1, 282) = 5.84, p = .016, ηp2 = 0.020). This result once again supports our main prediction that experiencing art reduces consumer interest in luxury goods (hypothesis 1). However, self-transcendence shielding eliminated this effect: framing the visuals as art or non-art had no impact on the number of luxury stores that participants chose to visit (Mart = 1.99, SD = 1.95 vs. Mnon-art = 1.82, SD = 1.59, F(1, 282) = 0.40, p = .53, ηp2 = 0.001). We also analyzed the number of non-luxury stores chosen as a function of the manipulated conditions. The results revealed a non-significant interaction (F(1, 282) = 0.78, p = .38), a non-significant main effect of the visual type (F(1, 282) = 0.83, p = .36), and a non-significant main effect of the self-transcendence shielding manipulation (F(1, 282) = 0.81, p = .37). These results provide strong evidence that viewing art visuals only reduces consumer interest in luxury goods, without affecting non-luxury consumption desire.

Need for Status

Similar analyses were conducted for the need for status. There was a significant interaction (F(1, 282) = 4.35, p = .038, ηp2 = 0.015) and a significant main effect of self-transcendence shielding (F(1, 282) = 8.24, p = .004, ηp2 = 0.028). There was no significant main effect of visual framing (F(1, 282) = 0.43, p = .52,ηp2 = 0.002). Pairwise comparison showed that in the self-transcendence control condition, participants’ need for status was marginally lower after viewing art-framed visuals versus non-art-framed visuals (Mart = 3.87, SD = 1.41 vs. Mnon-art = 4.30, SD = 1.09, F(1, 282) = 3.23, p = .07, ηp2 = 0.01). However, after participants were shielded against self-transcendence, viewing art versus non-art visuals had no impact on participants’ need for status (Mart = 4.64, SD = 1.36 vs. Mnon-art = 4.42, SD = 1.21, F(1, 282) = 1.23, p = .27, ηp2 = 0.004).

Moderated Mediation

Finally, a moderated mediation analysis was performed to test the mediating roles of self-transcendence and the status-seeking motive in explaining the negative effect of viewing visuals framed as art on the number of luxury stores chosen. We conducted a bootstrapping analysis to test this analysis using Hayes’s (2018) model 8. The results showed that in the self-transcendence control condition, the indirect effect of the art-framing visual via the need for status on the desire for luxury was significant (b = 0.32, SE = 0.11, CI: [0.12, 0.55]). However, in the self-transcendence shielding condition, the indirect effect of the art-framing visual via the need for status on the desire for luxury was not significant (b = 0.05, SE = 0.09, CI: [−0.11, 0.23]). The index of moderated mediation was also significant (index = 0.27, SE = 0.13, CI: [0.01, 0.54]). This study provided additional evidence that experiencing art induces self-transcendence, which dampens the status-seeking motive and consequently reduces consumer interest in luxury. However, shielding the induction of self-transcendence eliminated the effect of experiencing art on both the status-seeking motive and interest in luxury. Thus, taken together, the results of our analyses support hypothesis 3.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Luxury firms increasingly present works of art in their boutique stores, high-end malls, and online retail spaces. However, little empirical work has tested the impact of this practice of luxury firms on consumer desire for luxury goods. To the best of our knowledge, the present research is the first to addresses this important issue.

Across multiple field studies and lab experiments, we provide convergent evidence that experiencing art reduces consumer desire for luxury goods. We also identify the conditions under which this negative effect occurs. The phenomenon occurs when consumers experience art for art’s sake, and not for other purposes, and when luxury products are seen as status goods, and not positioned in another way. Accordingly, we show that the effect diminishes when (1) the work of art is experienced as decoration on the product or packaging, (2) processed analytically with a focus on the technical details (such as colors and lines), or (3) when luxury products are positioned as non-status-related such as artistry and creativity. Finally, we provide process evidence for this effect. We demonstrate that experiencing art elicits the mental state of self-transcendence, which undermines consumers’ status-seeking motives and thereby reduces the desire for luxury goods.

Contributions to Consumer Research on Art and Esthetics

The current research contributes to the literature on the roles of art and esthetics in consumer behavior and marketing in multiple ways. Given that product design and esthetics are key factors in marketing and sales success (Bloch 1995; Miller and Adler 2003; Schmitt and Simonson 1997), a rich stream of extant research has studied how a product’s artistic and esthetic design can impact consumers’ evaluation of and experience with the product (Hoegg and Alba 2008). Research has shown that incorporating art in the product or product packaging enhances consumers’ evaluation of the product (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b; Townsend and Shu 2010). Prior research has also demonstrated similar positive spillover effects of esthetic designs on consumer attitudes and purchase intention (i.e., “the art infusion effect,” Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a 2008b; Veryzer and Hutchinson 1998), consumer experience (Kumar and Garg 2010; Venkatesh et al. 2010), and self-affirmation behaviors (Townsend and Sood 2012). While prior research has shown the effects of art when it is part of the product design (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b, 2011), we show the impact of art when it is presented independently—that is, when it is experienced for its own sake.

The distinction between l’art pour l’art versus art being used for another purpose is of theoretical and practical significance. It showcases the different functions and consequences that art may have in luxury business when it is an integral part of the luxury product or when it is used independent of and separate from the merchandise. We provide robust empirical evidence to show that consumer desire for luxury goods can decline after experiencing art as art in the environment. In contrast, including art as part of the packaging design of a luxury product is likely to elevate consumer evaluation directionally, although the size of the effect we observed in study 2a for luxury goods was relatively small and non-significant compared to the effects previously observed for non-luxury products (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a).

Our research reinforces previous results that the effects of consumer esthetics are not universally positive. For example, when a donation solicitation site incorporated costly esthetics such as gold ink, consumers showed less intention to donate (Townsend 2017). In addition, consumer enjoyment of using a highly esthetically appealing product decreased when there were concerns that using it would destroy the beauty of the product (Wu et al. 2017). We extend this line of work by providing theoretical insights and empirical evidence that art can negatively affect consumer desire for status-related luxury goods when art is experienced independently from the product.

Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of this research is the exclusive focus on the influence of visual art (paintings, sculptures, and photography). While, in principle, different forms of art, through their symbolic significance, may elicit the mental state of self-transcendence and therefore reduce the desire for status-enhancing luxury goods, the results of viewing other art forms may vary in how easily and strongly they evoke this unique mental state. Future research should investigate the extent to which our results hold for other art forms such as theater and dance as well as classical music, which is frequently played as background music or performed live in luxury malls. Some luxury firms have already chosen classical musicians as brand ambassadors (Benedetti 2015), and some brands (e.g., Chanel and Dior) have invited orchestras and musicians to perform in fashion shows and in stores. We note that classical music has qualities that many visual works of art possess less of. For example, classical music uses as a different sensory mode and the temporal nature requires attention over time. Future research should therefore investigate whether our results are specific to visual arts or whether they can be extended to other art forms such as music.

Another limitation is that our research only examined the immediate effects of experiencing art on consumer desire for luxury goods. In our research, the proposed effect occurs immediately after consumers experience works of art. Future research should study the long-term consequences of experiencing art, for example, on brand memory, attitudes, and customer loyalty. Incorporating works of art into the retail environment may also affect consumer-brand relationships (Fournier 1998) and brand attachment (Park et al. 2010). For example, Hagtvedt and Patrick (2008b) showed that visual art can enhance the perceived fit in brand extensions and result in more favorable evaluations. Similarly, it is possible that experiencing art, which elicits self-transcendence and leads to an immediate reduction in consumer desire for luxury products, may enhance consumer memory of the brand and thus could contribute to building long-term relationships and engagement with the brand. This long-term relationship may lead consumers to perceive luxury brands that display visual art in the environment as more extendable beyond core product categories and result in more positive brand extension evaluations.

Finally, we did not examine whether owning visual art has the same impact on consumer desire for luxury goods as viewing of art. Future research may investigate whether possessing works of art can lead to materialism, which may, in fact, enhance consumer desire for luxury goods.

Practical Considerations