-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Susanna Molander, Jacob Ostberg, Lisa Peñaloza, Brand Morphogenesis: The Role of Heterogeneous Consumer Sub-assemblages in the Change and Continuity of a Brand, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 49, Issue 5, February 2023, Pages 762–785, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac009

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

How do brands change in environments defined by increasing consumer heterogeneity? Drawing on assemblage theory, this research develops the concepts of brand morphogenesis and consumer sub-assemblage to explain how heterogeneous consumer groups instigate, reinforce, and hinder the evolution of a brand. This longitudinal case study of a Swedish fashion brand delineates the role of heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages in the continual process of emergence and transformation of a brand assemblage through space and time—a process defined as brand morphogenesis. The findings detail brand morphogenesis in the sub-assemblage dynamics of exploration, actualization, and habituation of value, as heterogeneous consumer groups form consumer sub-assemblages in interaction with other brand components and interact in patterns of coexisting with, coopting, and contesting other sub-assemblages. By charting consumers’ value negotiations as they play out within and among consumer sub-assemblages, this research contributes to understanding continuity and change for brands that face increasing consumer heterogeneity.

A brand’s ability to change to remain relevant for various stakeholders is key in today’s increasingly unstable and fragmented world (Arvidsson and Caliandro 2016; Bardhi and Eckhardt 2017; Giesler 2012; Holt 2004; Keller 2021; Preece, Kerrigan, and O'Reilly 2019). Some researchers have focused on how successful brands balance change by emphasizing the continuity of certain essential qualities (Aaker 2012; Keller and Swaminathan 2020), such as brand identity (De Chernatony 1999), powerful myths (Holt 2004), and brand formulas (Preece et al. 2019). Other researchers have highlighted that monitoring and controlling change is increasingly difficult for brand managers not least because of the many stakeholders that influence brands in different ways (Keller 2021; Swaminathan et al. 2020).

One important set of stakeholders is the heterogeneous consumer groups that consume brands in more or less distinct ways (Keller 2021; Price and Coulter 2019; Warren et al. 2019). A recent stream of research has taken an assemblage perspective to detail processes of change and continuity among the multitude of components that comprise brands (Giesler 2012; Parmentier and Fischer 2015; Preece et al. 2019; Rokka and Canniford 2016). Whether focusing on how to hold on to a brand’s essential qualities while updating it to integrate social change (Preece et al. 2019) or on the different stakeholders that push brands in various directions (Giesler 2012; Parmentier and Fischer 2015; Rokka and Canniford 2016), these studies have generated important insights into the dynamics of change and continuity in brands.

Nevertheless, although brand assemblages have been theorized extensively as continuously subject to change, we know comparably little about how heterogeneous consumer groups react to such change and thus reinforce or hinder it. When investigated from an assemblage perspective, change has been attributed to the introduction of new, heterogeneous components to the brand assemblage, such as the increasingly progressive social views of gender that influence the Bond brand (Preece et al. 2019), the microcelebrity selfies produced and posted online by subsets of champagne consumers (Rokka and Canniford 2016), the doppelgänger brand images created by fans of the television show America’s Next Top Model (Parmentier and Fischer 2015), and the Botox doppelgänger brand images created by activists, competitors, and other stakeholders (Giesler 2012).

Conversely, continuity has been theorized as the result of processes whereby skilled management action succeeds in (re)stabilizing the brand. Focusing on longevity for the James Bond brand, for example, Preece et al. (2019) detailed the important activities of skilled brand stewards in adding and removing brand components to keep a brand assemblage current with sociocultural changes while keeping the brand formula intact. In another work, Giesler (2012) explained how Botox brand managers countered doppelgänger brand images.

Indeed, the detailed focus on brand managers has taught us plenty about their role in achieving continuity amidst change, and yet we know relatively little about the roles played by heterogeneous consumer groups. Although previous research has directed some attention to the different images of brands among different stakeholders (Giesler 2012) and to consumers’ different activities, including selfies (Rokka and Canniford 2016) and protests against content changes (Parmentier and Fischer 2015), questions involving how different types of consumer groups react to change and contribute to continuity are left unanswered in these brand assemblage theorizations. For example, how did consumers attracted to the original version of James Bond (Preece et al. 2019) or Botox (Giesler 2012) react to new versions of the brand? When fans denounced the changes introduced in the serial brand America’s Next Top Model (Parmentier and Fischer 2015), what about the rest of the audience? As importantly, how do these different consumer groups relate to each other? Taken together, this work has generated valuable insight into aspects of the constant change processes characterizing brand assemblages, yet leaves a dearth of knowledge regarding how such changes are instigated, reinforced, and hindered by heterogeneous consumer groups as they actualize value in relation to each other.

To address this gap, this article theorizes how multiple heterogeneous consumer groups simultaneously consuming a brand impact its change and continuity over time. We apply an assemblage perspective in examining brands as open-ended sociomaterial systems of value that are created for commercial purposes and managed over time to serve the needs, wants, and desires of companies, consumers, and other stakeholders, and we are particularly concerned with the formation of and dynamics among heterogeneous subgroups of consumers in the continuity and change of a brand assemblage. Drawing on Deleuze (1994), we define brand morphogenesis as a continual process of emergence and transformation for a brand assemblage as it develops its particular shape through space and time. Although a certain degree of repetition among activities, materials, and stakeholders tends to occur when an assemblage is continuously reassembled in various new iterations, the new versions also tend to differ as the process inexorably takes place in different spaces and times (Colebrook 2002). Rather than focusing on the results of the process, DeLanda (1998) noted that key in analyzing morphogenesis are the dynamics that drive the process of emergence and transformation, without which the assemblage would cease to exist. Of particular importance in our theorization of brand morphogenesis is the entrance and exit of heterogeneous groups of consumers that interact with subsets of other brand components and thereby form consumer sub-assemblages that are nested in the overall brand assemblage. We define a consumer sub-assemblage as a distinct value arrangement that is produced by a subset of consumers as they actualize value in interaction with other brand components. This latter concept enables us to comprehend and highlight the different sets of expressive and material capacities that heterogeneous consumer groups produce as they interact with various components in the overall brand assemblage and to trace the interactions among their distinct value arrangements.

This research is important as it highlights the dynamic role of heterogeneous groups of consumers in the change and continuity of a brand assemblage over time. As Keller (2021) observed, brands and branding are likely to be increasingly defined by consumer heterogeneity in the coming years, and thus an understanding of how distinct consumer groups influence brand assemblages is critical for brand managers, consumers, and other stakeholders. Despite having limited control over the components that continuously enter and leave a brand assemblage, brand managers are challenged to cater to diverse consumer groups simultaneously and keep brand assemblages relevant for each (Warren et al. 2019). In turn, consumers are challenged by the contested, heterogeneous terrains of brands in fashioning identity (Arsel and Thompson 2011) and community (Luedicke 2015; Thomas, Price, and Schau 2013). Our theorization of brand morphogenesis addresses Preece et al.’s (2019) call for insight into how consumers consume a diverse and dynamic brand assemblage over time in relation to their own life histories. Furthermore, by considering the role of consumers in forming consumer sub-assemblages with subsets of brand components, and the interactions of such sub-assemblages in the change and continuity of a brand assemblage, we complement former studies in shedding light on the continued allure of brands in consumer culture increasingly characterized by the instability of heterogeneity and fragmentation (Bardhi and Eckhardt 2017; Keller 2021).

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS: UNDERSTANDING HETEROGENEOUS CONSUMER GROUPS AND THEIR INTERACTIONS IN EVOLVING BRANDS

Many previous studies of brands apply an assemblage perspective (Giesler 2012; Lury 2009; Parmentier and Fischer 2015; Preece et al. 2019; Rokka and Canniford 2016). This body of work approaches brands as “mobile arrangements of multiple, heterogeneous, and unpredictable [components]” (Rokka and Canniford 2016, 1792) that interact with one another “in ways that can either stabilize or destabilize an assemblage’s identity” (DeLanda 2006, 12). When change occurs, the interactions between the components risk losing their alignments and the assemblage becomes destabilized. Conversely, when the interactions become a habit, that is, habituated, the assemblage stabilizes. All assemblages are characterized by continuous iterations of destabilization and restabilization as they move through space and time. These iterations are like a continuous but necessary pulse—sometimes high in frequency, sometimes low, sometimes more amplified, sometimes less.

It is this pulse of new iterations that causes the brand assemblage to continuously evolve in a process of brand morphogenesis. Change triggers of different scale and scope can all lead to destabilization, from macrolevel changes involving sociocultural and market contexts (Preece et al. 2019) to microlevel changes including activities by subsets of consumers (Rokka and Canniford 2016), fans (Parmentier and Fischer 2015), managers (Preece et al. 2019), and combinations of both media and consumers (Giesler 2012). Staying true to the “‘flat’ ontology” of assemblage theory (Bajde 2013, 229), we give none of these triggers an a priori status as more important than the others. As already mentioned, the view of (re)stabilization and the ensuing continuity of a brand assemblage has typically been theorized as instigated by managers’ skilled actions. Preece et al. (2019) emphasized managers’ careful curation of the brand formula, whereas Giesler (2012) directed attention to their effort in countering the effect of doppelgänger brand images. These studies illuminate various agents and forces destabilizing brand assemblages and what managers do to restabilize them. Nevertheless, they have not addressed the activity of heterogeneous consumer groups in instigating, reinforcing, and hindering change and continuity in a brand assemblage.

Notably, although most brand assemblages feature a specific type of consumer group as they start out, successful brands tend to expand and diversify in targeting other consumer groups over time, leading to a more heterogeneous customer base. In their work on brand coolness, for example, Warren et al. (2019) discussed the problems as cool niche brands expand their customer base and become adopted by the mainstream. Moreover, the addition of new, heterogeneous consumer groups to a brand assemblage presents a type of change that risk destabilizing the brand. Indeed, the expansion of a brand’s customer base to include new heterogeneous consumer groups is part and parcel of most companies’ growth strategies and thus merits further exploration.

Rather than viewing the increased heterogeneity as inherently problematic, we draw inspiration from Lury’s (2009) account of the value potential in brand assemblages, in suggesting that difference and destabilization are what opens up the assemblage to further value potential. The author suggested that brand assemblages produce value over time in processes that involve “diverse professional activities, including marketing, graphic and product design, accountancy, media, retail, management, and the law […] And consumers, of course, are also involved in making the brands through their participation in activities of recognition, communication, and identification and the purchase of goods and services” (Lury 2009, 67). We further build on Canniford and Shankar’s (2013, 1053) insight that value emerges “from networked associations established between diverse kinds of consumption resources,” in considering the eclectic components at different levels as we analyze the clustering of value arrangements among brand components, which we term consumer sub-assemblages. We are particularly interested in the sub-assemblages formed as consumers interact with other consumers and other brand components.

Previous research has suggested that the relations between components form value arrangements that manifest as identity (Elliott and Wattanasuwan 1998), community (Thomas et al. 2013), and linking value (Cova 1997). Applying the consumer sub-assemblage concept to such diverse identity, community, and linking value arrangements helps explore how one consumer group’s interaction with assemblage components gives rise to a set of expressive and material capacities that differ from those activated by another consumer group with different identity, community, and linking value.

Also helpful in examining the value produced within and among heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages is previous work detailing a range of different types of consumer groups, from communities with close affiliations to more loose gatherings. One side of the spectrum is exemplified by Muñiz and O’Guinn (2001) in recognizing the shared sense of belonging, social relationships, and activity among members of a brand community. The other side of the spectrum is exemplified by Arvidsson and Caliandro’s (2016) work on brand publics that describes a formation comprised of consumers with a plurality of identities and practices, who engage with other consumers regarding a brand on social media, yet lack a shared sense of belonging, close relationships, common value systems, rituals, and traditions. In between these two types of aggregations of consumers are more or less ephemeral tribe constellations (Cova 1997; Cova and Shankar 2018) held together for reasons of shared activity and interest.

As crucial to the conceptual framing of this research is building on previous work attending to how an assemblage holds multiple consumer groups simultaneously. Thomas et al. (2013) pointed to the shared resources that bind heterogeneous consumer groups and the efforts of members in mending betrayals and overcoming differences to keep their community intact. In turn, Arvidsson and Caliandro (2016) highlighted the affective intensities of a brand that drive engagement in collective public discourse. Our analytical focus on distinct consumer groups that interact within a brand assemblage and thereby form various types of value arrangements can include any of these different types of consumer groups. Of interest are the multiple ways in which consumers relate to a brand, as it encompasses several intersecting assemblages simultaneously, each with its own internal driving force affecting how the brand emerges and morphs through space and time. For example, in applying this logic to Thomas et al.’s (2013) study, we would consider the heterogeneous consumption community of competitive and social runners as an assemblage with a driving force to evolve for its own sake while intersecting with many brand assemblages that play a subordinate role as a community resource. In applying this logic to the brand publics described by Arvidsson and Caliandro (2016), we would highlight a contrasting, centripetal role for the brand in collectively binding the intersecting assemblage of affective intensities characterizing the heterogeneous brand public.

In summary, this research builds on this previous work in exploring the activities of heterogeneous consumer groups and their interactions in the continual process of brand morphogenesis through which a brand assemblage emerges and transforms in increasingly diverse and fragmented consumer cultures over space and time. More specifically, we examine the dynamics at play within and among the diverse consumer groups simultaneously consuming a brand as we address the following questions: What are the dynamics in a brand assemblage when heterogeneous consumer groups enter? What are the dynamics within heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages housed in a brand assemblage over time? And what are the dynamics among heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages housed in a brand assemblage? In examining the distinct value arrangements produced by heterogeneous consumer subgroups as they interact in a brand assemblage in various ways, we strive to generate insight into consumer heterogeneity more broadly (Keller 2021), and more specifically, to “the kinds of assemblages created in consumer culture” (Rokka and Canniford 2016, 1807, emphasis in original) and “the dynamics in one or more intersecting brand assemblages” that “contribute to the stabilization and destabilization of the focal brand” (Parmentier and Fischer 2015, 1249).

METHOD

As is customary with assemblage approaches (Giesler 2012; Parmentier and Fischer 2015; Preece et al. 2019; Rokka and Canniford 2016), we focus deeply on a single case. We selected the Cheap Monday (CM) brand assemblage for study because of its many changes and heterogeneous consumer base over the years. Guided by Giesler and Thompson’s (2016) process theorization, we seek to specify the theoretically relevant role(s) of consumers as they interacted with various components in the CM brand assemblage. Specifically, we aim to identify and examine the catalytic triggers, the consumers, and other components as they contributed to the value rearrangements forming consumer sub-assemblages, and decipher the relations within and among these sub-assemblages across six phases from 2004 to 2019. The research design features fieldwork and photographs, interviews, artifacts, and archival data (see appendix for a list of data types and sources).

Field observations were conducted at the rock club Debaser, a site frequented by CM founder Örjan Andersson and his circle of friends, as well as other indie consumers, during the brand’s early days, and in following company activity in the various Stockholm stores from 2006 to 2018, at flagship stores in London, Copenhagen, and Paris, and at a popup store in Tel Aviv. Additionally, we observed company activity in the CM head office in Stockholm and attended events from 2009 to 2017, including a conference where Ann-Sophie Back, CM’s chief designer, gave a talk and several fashion shows in Stockholm. Later, we collected additional data pertaining to CM’s branding activities and related media coverage in other geographic contexts in accord with its international growth and diffusion to help situate the brand assemblage globally.

Interviews provided access to the microinteractions and interpretations that took place within the brand sub-assemblages, whereas observations and artifacts helped elucidate relations among sub-assemblages and impacts to the overall brand assemblage. In selecting consumers to interview, we seek variation in their time with the CM brand and their interest in fashion. The 28 interviews lasted on average one hour. To minimize interview bias, we applied an informal, conversational style, and introjected our questions and prompts during natural pauses in the dialog, as recommended by McCracken (1988). We began interviews in 2006 with founder Andersson, other key members of the organization, various employees, and consumers. Although 24 of the interviews were individualized, we also conducted interviews with four friendship pairs of consumers, with the researcher playing a minor role, which enabled the participants to talk naturally to each other (Bulmer and Buchanan-Oliver 2014) in ways that simulated their interactions within the brand assemblage. In 2012, we conducted a second set of interviews with representatives of the company at the Stockholm headquarters and at the London store. Our last set of interviews in 2014 explored consumers’ experiences with the brand from its initial launch through its middle growth years and later international expansions.

The archival data were collected during our observations, from the CM website, and with help of Google search and Mediearkivet, a Swedish research archive that contains material regarding Swedish companies in all the major and provincial newspapers, magazines, journals, and periodicals in Sweden as well as internationally. By using case-related search terms, we captured major developments occurring within and around the brand assemblage from 2000 until 2019. As examples, we collected company sales figures and details pertaining to events, such as fashion shows, which we supplemented with online and conventional media accounts of particular components comprising the diverse manifestations of the brand assemblage over the years. As such, our dataset features consumers’ perspectives and interactions with the brand, as well as its mediated activity, in ways somewhat like those of Arvidsson and Caliandro (2016).

Using a hermeneutical approach (Thompson 1997), we analyzed these data in an iterative process in which our research questions and readings of relevant theoretical material guided the initial coding, followed by subsequent data analysis, interpretation, and rereading of the literature. In addressing our first research question—the dynamics at play in a brand assemblage when heterogeneous consumer groups enter—we conducted a holistic analysis of the interview transcripts, field notes, photographs, promotions, company data, and media coverage to specify respective triggers pertaining to the introduction of a new brand component and to chart subsequent value rearrangements within the brand assemblage in its entirety. In addressing our second research question—dynamics within heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages after change—we conducted an intratextual analysis to distinguish components, interactions, and the types of material and expressive enactments that these interactions gave rise to and thus identify the types of value actualized within particular consumer sub-assemblages. Six distinct phases involving four different consumer sub-assemblages emerged in the initial analysis as follows: indie consumers, trend seekers, fashionistas, and mainstream consumers. We identified common themes within, as well as variation across these sub-assemblages, on the basis of their respective interests and activities regarding the CM brand as such, fashion and popular culture more broadly, and their interactions with others—or the lack thereof. The groups were not homogeneous in terms of demographics, nor did they share “a consciousness of kind” (Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001). Instead, they were grouped via the specific value arrangements they produced when interacting with subsets of other brand components in the form of consumer sub-assemblages that materialized in a similar form.

To answer the third research question—the dynamics at play among heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages after change—we conducted a more detailed intratextual analysis within each phase, mapping the interactions among the sub-assemblages housed in the overall assemblage. In addressing the role of heterogeneous consumer groups in the dynamics of continuity and change overall, we conducted an intertextual analysis across the totality of the material in distinguishing the role of heterogeneous consumer groups as subjects and objects. As subjects, consumer groups operated as agents in contributing to changing the overall assemblage in all the phases except for the last one, when the brand owner discontinued the brand. As objects, the consumer groups were impacted by the presence of the other consumer sub-assemblages as well as other components. In the next section, we begin with some background in charting the CM brand from a small niche operation selling jeans in Stockholm into a player on the global fashion market and then present the six phases in discussing dynamics within and among consumer sub-assemblages, and their impacts on the change and continuity of a brand assemblage.

CM: A Brief Background

In 2000, Örjan Andersson started a “hobby business” with three of his friends selling vintage clothes, designer jeans, and tops, alongside his full-time job at a Swedish apparel chain. In March 2004, the first CM jeans debuted a skinny, matchstick look in stretchy black fabric at the price of 400 SEK ($55 USD). The jeans became an immediate success. By the end of 2006, CM was sold in 150 stores in six countries in Europe, the United States, and Japan (Challis 2006). In 2008, the global retail chain H&M bought 60% of CM, which then sold at 1,000 retail outlets worldwide (H&M 2008). CM’s expansion continued thereafter as a wholesale brand controlled by H&M. In 2009, the renowned fashion designer Ann-Sofie Back joined Andersson as creative director, and in 2011, Andersson and the other founders sold the rest of their shares to H&M and left the company. Notably, the CM brand was never sold in H&M’s stores but had its own flagship, internet, and popup stores as well as independent resellers that numbered approximately 2,000 in 35 countries globally by 2012 (Affärsvärlden 2012). Carl Malmgren, who had been with CM from the start, replaced Back in 2017. In November of the following year, H&M announced the discontinuance of CM as a response to major challenges in their retail business model that forced the company to streamline operations (Yttergren 2018). By then, one flagship store in London remained, alongside 1,800 resellers globally in more than 35 countries (Cheap Monday 2018). In what follows, our findings detail how dynamics at play within and among heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages contributed to change and stability in the multiple iterations of the brand assemblage that manifest during CM’s 15 years in business.

FINDINGS

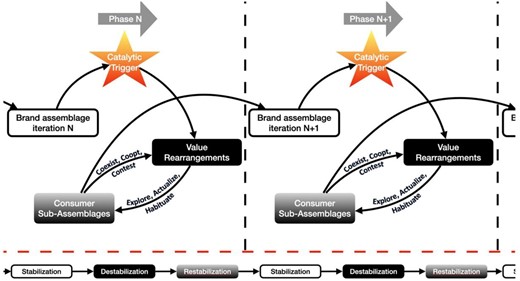

In presenting the findings, we first describe the general process of brand morphogenesis. We then detail how the CM brand assemblage formed and evolved over time in six phases, with attention to the catalytic trigger and subsequent value rearrangements forming each consumer sub-assemblage, and to the relations among consumer sub-assemblages for each phase. Figure 1 shows two such phases. A more detailed account and graphic representation of the distinct consumer sub-assemblages and interactions that formed the six phases of the focal brand assemblage is available in the web appendix.

BRAND MORPHOGENESIS

Distinct consumer sub-assemblages form as consumers explore, actualize and eventually habituate the value potential in the destabilized brand assemblage. Consumer sub-assemblages relate to each other in three principle ways-coexistence, cooptation, and contestation-that in turn cause further value rearrangements.

In the initial iteration of the brand assemblage—the genesis of form (DeLanda 1998)—its components form the coherent entity that we normally recognize as a brand assemblage. Prior to this, some of the components already had loose relationships with each other. However, the components started relating to each other as a brand assemblage through actions of the founders, such as registering a name and a trademark, developing a logo, designing products and services, and bringing them to the market; and the actions of consumers in buying and wearing the brand. Once the jeans were on the market, consumers started interacting with components in the brand assemblage to explore possible identity, community, and linking value arrangements. When enough consumers actualize value from the brand and relate to it habitually, by purchasing the brand and making it part of the constellation of brands with which they furnished their lives, the brand assemblage manifests a position of relative stability, which we label brand assemblage iteration N in figure 1.

From assemblage theory, we know that assemblages rarely remain in a position of stability and are instead characterized by a constant renegotiation of relationships among components. Although small changes and ensuing renegotiations of relationships among the components happen all the time, the findings focus on substantial shifts that cause disruptive changes. In what follows, we identify three key dynamics that encapsulate this change process.

Catalytic Triggers Leading to Value Rearrangements

Scaraboto and Fischer (2016) noted that disruptive changes are caused by catalytic triggers. In building on their work, we highlight the catalytic trigger (marked with a star in figure 1) that sets in motion a series of renegotiations of relationships among the components in the brand assemblage. For CM, catalytic triggers included the jeans, the media buzz around the brand, H&M purchasing the brand, the addition of designer Ann-Sofie Back, the exit of Örjan Andersson and the other founders, and the discontinuation of the brand. In these renegotiations, components may join the brand assemblage, leave, or carry on apart from one another. The analysis elaborates the disruptions and altered relationships that stem from the entry and activity of consumer groups and their interrelationships as they destabilize the brand assemblage and lead to subsequent value rearrangements, as indicated in figure 1.

Value Rearrangements within Consumer Sub-assemblages

When relationships are destabilized, consumers must again explore whether they can actualize and habituate value in the brand assemblage. New heterogeneous consumer sub-assemblages form in certain circumstances when subsets of new and already existing consumers interact with brand components in new ways, producing new distinct value arrangements. Each consumer sub-assemblage is characterized by distinct expressive and material capacities of value pertaining to the consumer group in question. Also important are the within-group activities, vis-à-vis the other components, that constitute value in the brand sub-assemblage, and the interrelations among different sub-assemblages, which we discuss next.

Relationships among Consumer Sub-assemblages

As a new consumer sub-assemblage forms, relations among sub-assemblages are renegotiated. Our analysis distinguished the following three principal relations: coexistence, whereby a sub-assemblage exists alongside another sub-assemblage without changing its expressive and material character; cooptation, whereby a sub-assemblage appropriates parts of another assemblage’s expressive and/or material character; and contestation, whereby a sub-assemblage is unable to actualize value when existing side by side with another sub-assemblage and thereby dissolves. Over time, when a new sub-assemblage forms and relates to (an)other sub-assemblage(s), the overall brand assemblage may again achieve a position of relative stability and emerge as a new iteration, which we label as iteration N + 1 for the brand assemblage in figure 1. The text at the bottom of figure 1 charts the constant flow of continuity and change in a brand assemblage as renegotiations among sub-assemblages shift from relative stability, to instability, to a new form of relative stability. Drawing on Deleuze (1994), we adapt the term morphogenesis to encompass the processes by which a brand assemblage continuously morphs into new, yet recognizable versions of itself. The series of arrows in figure 1 indicate continually ongoing morphogenetic processes of triggers, sub-assemblage relations, and value rearrangements in the brand assemblage, rather than a linear cause and effect process.

We next detail the catalytic triggers and sub-assemblage formations and interrelations across six phases in the morphogenesis of the CM brand assemblage. As we demonstrate, each new phase is catalyzed by a trigger that attracts a new consumer group to explore and actualize value in the brand assemblage and thus forms a consumer sub-assemblage of new value rearrangements in interaction with other brand assemblage components and with interactions among existing sub-assemblages. We end with the sixth and last phase, when the brand was discontinued, which caused drastic rearrangements among the components in the brand assemblage, although some consumers continued to interact with it.

Phase 1: Genesis of a Brand Enabling Indie Consumers to Enact the “Affordable Indie Uniform” (2004–2005)

Then we got the idea: “Shit, let’s get our own brand that no one else has!” […] Hardly anybody did [skinny jeans] then and all our regulars wanted them. (Andersson, interview 2006)

In this passage, Andersson, one of the three founders of CM, describes how they grew tired of seeing all their struggling indie friends come into their store ogling their selection of really cool skinny jeans from around the world and never being able to afford to buy anything.

Catalytic Trigger Leading to Value Rearrangements

The CM brand assemblage was formed at a time of a strong indie rock trend and a thriving scene of young creatives in Stockholm focused on music, art, design, fashion, and related areas. “Indie” is short for independent, and “refers to artistic creations produced outside the auspices of media conglomerates and distributed through small-scale and often localized channels” (Arsel and Thompson 2011, 792). Although indie consumers are energized by a “countercultural ethos of resistance to the market” (Bannister 2006, 57), collective consumption characterized by shared cultural knowledge, esthetic tastes, and social networks (Arsel and Thompson 2011) is an important part of what distinguishes them. For the indie consumers orbiting around what was to become the CM brand, this consumption usually took place in clubs and backstreet stores. This also was the kind of environment in which the CM brand assemblage emerged, catalyzed by a small backstreet store that sold other brands. “In the beginning, the store was a place to hang out, where people came to try on jeans, slouch in the armchairs, and listen to indie music,” said Malin (interview 2006, female, age 25 years), who later became a CM manager. She recalled Andersson sitting behind the cash register, casually flipping through a magazine as if he was hanging out in his own living room. The store and the other hangouts offered important material capacities during these early days that enabled indie consumers to routinely interact in face-to-face encounters with those who would later become the brand stewards. These places also offered an expressive capacity in the form of shared cultural knowledge and esthetic tastes that contributed to the brand stewards’ sensibility in understanding consumers’ preferences for jeans design and marketing and thus contributed to the brand assemblage’s initial formation:

When we made the first pair, we had only one store… we lived worse than students and felt like we had to do something to get our business moving, something that pulled in customers. We had some very faithful customers who were really cool and they came to the store and really wanted all the expensive clothes we had. They could only afford one thing, but they wanted to buy five… (Andersson, interview 2006)

As the quote illustrates, consumers and brand stewards formed a fairly closely knit brand assemblage of mutual respect based on cultural knowledge, esthetic tastes, and social networks (faithful customers who were really cool) that existed outside the mainstream (we lived worse than students). When Andersson and the other founders identified an available market position for cool and affordable jeans, they set in motion a series of events that subsequently produced the jeans that gave birth to the CM brand.

Value Arrangements within the Assemblage

The black matchstick silhouette obtained in wearing the jeans enabled indie consumers to enact what we call the Affordable Indie Uniform. Andersson made the jeans affordable by positioning them in between what he called “the stylish, unique designs of the stuck-up world of high fashion” and the “nondescript, low-quality jeans” of discount retailers (2006 interview). The denim fabric contained a lot more stretch material than denim typically did at the time, which provided wearers with the black, skinny silhouette that had characterized edgy rock for decades, as worn by Jim Morrison of The Doors in the 1960s, Bon Scott of AC/DC, and the members of the Ramones in the 1970s, and this look had resurged among indie rock bands such as The Strokes and The Vines at the time CM jeans launched.

Our analysis emphasizes how material and expressive capacities were produced when the jeans interacted with different types of consumer groups that conveyed important cultural values to each. For the indie consumer, those values were indie knowledge and esthetics, as the material capacities of the stretch jeans esthetically transformed the body into a skinnier-looking silhouette by functioning as a type of corset, and as the expressive capacities of the skinny jeans articulated an edgy, emaciated, rock esthetic. Still, these material and expressive capacities did not play out perfectly for everyone. The jeans had to interact materially with a lean body type to bring out the expressive capacities sought after by those in the know. Andersson, with his long and skinny physique, materialized a perfect version of the look.

The jeans were situated in a symbolic landscape of stories—materialized on the leather patch logo on the back of the jeans, as well as texts, such as “Over my dead body” and others, printed on t-shirts and captured in fashion photos, and articles about the brand—that gave the indie consumers access to expressive capacities of cultural knowledge outside the mainstream (Arsel and Thompson 2011). One of the designers of the logo, Björn Atldax, explained in an interview that he came up with a skull with a cross turned upside down on its forehead as CM’s logo in 2004, inspired by his interest in the occult, his participation in the indie music scene in Stockholm, and the Mexican holiday the Day of the Dead. He further described with enthusiasm having been inspired by pop culture when creating CM’s symbolic landscape, especially horror, fantasy, and science fiction, and he singled out the authors H. P. Lovecraft and Ray Bradbury, together with the Bible, as key sources. Such occultism historically has been related to popular music like The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Alice Cooper, and Black Sabbath and is a common reference to this day (Case 2016). Atldax explained that he used the symbols to “tell important stories” by mixing a skull that was meant to “repudiate Christianity” with “silly” illustrations of nonsensical objects from his everyday life, such as fishhooks, to “challenge viewers and offer something new.” Only those in the innermost circle knew what the fishhooks meant, whereas many indie consumers were knowledgeable about H. P. Lovecraft’s early 20th century horror stories and Ray Bradbury’s sci-fi and fantasy novels. Overall, with the jeans themselves as the catalytic trigger, the specific relationships among the components that were brought together as the CM brand assemblage was formed enabled distinct value arrangements for indie consumers.

Relationships among Nascent Consumer Sub-assemblages

During the first phase of the CM brand assemblage, the jeans became an instant success among the indie consumers. As Andersson (interview 2006) put it, “Two weeks [after their release], we sold tons of them ’cause the word was out. Yeah, and then the whole thing just speeded up. So, that whole first summer we never had enough.” The brand assemblage was fairly homogenous and formed a value arrangement catering chiefly to indie consumers—first in the closely knit circles around Andersson, then to increasingly larger indie crowds, and then beyond to others outside the intersecting indie assemblage. Nevertheless, it was not easy for anyone outside the closely knit circle around Andersson to explore value potential in the brand assemblage at this point in time. For those without in-depth knowledge of indie culture and occultism, the original store and symbolic landscape were difficult to interact with. Although the closely knit indie circle interacted with the store through habitual visits or even by helping out in different capacities, this type of value exploration was not as available for others. Indeed, Jamila, a trend seeker looking for the Absolutely Latest, recalled how hard it was to even find it: “We ran around in town and didn’t know where we were going. And when we asked people [about the store], they knew nothing. ‘What store?’” Even the consumers who eventually found it risked being repelled by the expressive capacities that came into play when interacting with the store. Alexander (male, age 30 years), a former salesperson, described the store as somewhat intimidating at this time, noting “all these thresholds that some people just couldn’t get over.” Sara, a designer who studied at Beckmans, Sweden’s premier design school, was more explicit in corroborating Alexander’s account in her description of guys hanging out at the store who were “far too tattooed, in saggy tank tops, [CM] jeans, worn-out Converse, and always hungover. […] The image was not so easily accessible.” The store functioned as a materialization of the sub-assemblage’s sharply drawn indie boundaries, crowned by the CM jeans that emerged as the most essential piece of the Affordable Indie Uniform.

Phase 2: Additional Value Arrangements Enabling Trend Seekers to Enact the “Absolutely Latest” (2005–2008)

I looked like a chicken with thunder thighs [laughing]. But then I just [said], “Damn, this is fashion. I gotta have them.” So, I bought them anyway. (Jamila, female, age 16 years)

Jamila was a typical trend seeker who started consuming the brand after it received worldwide notoriety via an AP news story coining the logo with the upside down cross on a skull as satanic. Key for Jamila, however, was not the symbolic meanings of Satanism but the fact that the CM logo represented the Absolutely Latest fashion look at the time.

Catalytic Trigger Leading to Value Rearrangements

Though CM was making greater sales and attracting larger crowds, it was an AP news story calling CM’s symbolic landscape “satanic” (Ritter 2005) that acted as a catalytic trigger by attracting a new consumer group, trend seekers, that destabilized the fairly homogenous brand assemblage. The story generated a buzz that according to Andersson (interview 2006), “spread like wildfire,” and for our analysis, instigated change around the world for the brand. Our search for CM in Google Trends indicated a boom of international attention to the brand after the story, akin to Arvidsson and Caliandro’s (2016) brand public.

The AP news story was first picked up by media houses such as NBC News (2005) and Fox News (2005) and consequently spread to Christian blogs in the United States, including Dean (2006) and Good Fight Ministries (2006), who criticized the success of the CM brand with its satanic logo and, by proxy, Sweden for taking “another huge step away from God, the creator and toward death and darkness.” The moral outcry of some Christian groups turned out to be a good global marketing and PR campaign for a brand with a limited marketing budget (FaBric Scandinavien 2006). The news story was a catalytic trigger that channeled the jeans and the symbolic landscape to a group of trendy resellers who in turn made the jeans available to consumers who otherwise might not have found them. In coinciding with the growth of indie consumption and the trendiness of satanic associations on the internet and in TV series (Abebe 2010), the buzz extended the reach of the brand assemblage well beyond the markets it had diffused into. In total, the changes that were ignited by the AP news story attracted trend-seeking consumers to explore value potential in the brand assemblage, and as they actualized and habituated this value, the consumer sub-assemblage that they formed destabilized the relationships among existing components.

Value Rearrangements within Consumer Sub-assemblages

Even as the news story worked as a repellant for consumers who did not appreciate the satanic undertones, the commotion attracted the trend seekers to explore the brand assemblage. Other components introduced by the brand stewards contributed to constituting CM jeans as the Absolutely Latest for trend seekers. Trendy stores, such as Colette in Paris, Selfridges in London, and Fred Segal in West Hollywood (Andersson, interview 2006), showcased CM to trend seekers and contributed to CM’s acclaim as one of the trendiest jean brands at the time. The disruptive fashion value logic of bridging the gap between an affordable price and trendiness was another factor, commented on by the renowned fashion journalist Susanne Ljung in an interview about the brand (Johansson 2020):

I remember when I saw CM jeans in a store in New York, hanging among Helmut Lang and other fancy brands. It was really a wow moment! […] Other brands usually have to choose between being popular or cool. CM managed to be both things at once by combining coolness and a low price. There was a mysticism around all of that and one just couldn’t wrap one’s head around the idea that a pair of jeans could be that cheap. Can anything that cool be that cheap?

That the coolness and trendiness of the jeans took center stage was corroborated by aspiring trend seeker Christoffer (male, age 25 years), who recounted that at first, it was only the really trendy who were into the brand:

It was like a small clique in our high school [who first had CM]. We didn’t really like how they dressed, even though we probably did deep down anyway. […] Well, these jeans guys, they had fairly tight jeans and Converse, they were very fashion conscious. And they had these fashionable hairstyles you had back then… this kind of rocker haircut.

It is important to note that Christoffer’s description of this trendy high school clique offers no elaborations on material and expressive designators that were typical for the indie consumers. Instead, he highlights a mesh of stylistic elements, the jeans brand, the shoe brand, and the hair. What materialized from these trend seekers’ focus on the indie style and occult symbols when interacting with the jeans was the type of prepackaged look that Arsel and Thompson’s (2011, 800) informants characterized as typical of “wannabes” who purchase a commercialized hipster ensemble rather than doing esthetic exploration and discovery on their own. As Jamila’s comment above illustrates, among the trend seekers, the brand logo emerged as emblematic of an entire stylistic ensemble, in functioning as a metonym for the entire look (Thompson and Haytko 1997)—the look “in vogue: “When you wear something you want to represent something, and as long as the brand is the right one, [you’re fine]” (Leila, female, age 17 years).

The value forming in the interaction between the trend seekers and the assemblage manifested a materiality that depended on body type, as the jeans’ tight-fitting denim stretch interacted with different consumers in different ways. Jamila, for example, did not like how she looked in the CM jeans when she first tried them on. Still, the jeans enabled her to embody the look in vogue, which compensated for their less compelling capacities:

But it’s OK. Even if I look like thunder thighs, I look around and realize that everyone else [in the know] actually looks the same [laughing again]. So it’s OK, that’s how it should be.

In fact, the jeans even gave rise to a new phenomenon called “poprygg” [pop back, equivalent to “muffin top”], indicating their ability to create a bump in the back due to their material capacity to press up parts of the body at the wearer’s back that did not fit in the jeans. The phenomenon became so common that Sweden’s major newspaper wrote about it in their style section (Nyheter 2005). Indeed, the materialization in wearing the right logo trumped the silhouette à la mode, at least for those unable to accomplish it.

Relationships among Consumer Sub-assemblages

The trend seekers formed a value arrangement in interaction with a subset of the brand assemblage components that enacted the Absolutely Latest and aligned an important identity position for consumers belonging to this group. Their diligence in following fashion was not a value arrangement that materialized in the indie consumer sub-assemblage. Instead, for the indie consumers, value came from enacting the Affordable Indie Uniform, which successfully linked them to other indie consumers.

Indeed, the brand stewards’ jean prowess and polyvocality in portraying CM opened for both groups to simultaneously actualize and habituate value in the brand assemblage. On the one hand, CM was portrayed as ideologically charged in “making an active statement against Christianity” that attracted some indie consumers (Atldax in Fox News 2005 and interview), and on the other hand, it was portrayed as merely playing with the symbols in ways that attracted the trend seekers (Andersson in Dean 2006 and interview 2006). Leila (female, age 17 years), a trend seeker who was more interested in wearing the jeans and logo than the assemblage’s anti-Christian ideology, commented: “I haven’t thought about [the inverted cross] […] Currently, religion doesn’t mean much, so people don’t really [get upset].” In contrast, Mats (male, age 34 years), an artist and specialist in the occult and closer to the indie circles, was more attentive to CM’s references to “classic [occult] iconography” in his interview.

But although the assemblage’s openness toward these multiple value arrangements opened possibilities, some indie consumers made a distinction between their sub-assemblage and that of trend seekers. Malin (interview 2006, female, age 25 years) was clear in expressing how the value arrangements differed between the two groups:

There are many personalities here that are quite strong, from the music world and the club world. [Meanwhile, we have] a lot of these Laroy [a posh night club and hang out for trend-seekers] customers, because they’re the ones with money [laughter]. Sort of a love-hate relationship, you could say. But in my eyes, these customers don’t really have any feel for fashion. […] People who, in my opinion, have the money and who buy a brand.

Her remark corroborated our analysis that the “many strong personalities” of the indie contingency were more informed about music and style, and their value in interacting with and being part of the assemblage had more to do with linking to other like-minded individuals who shared the same cultural references. As such, their relationship to the trend seekers was more passive coexistence as they focused on their own consumer sub-assemblage.

Conversely, the trend seeker sub-assemblage related to that of indie consumers is, in a way, best characterized as cooptation. Given that the indie look was fashionable at the time, part of what attracted the trend seekers to the CM brand assemblage was the copresence of the indie consumers. In wearing CM as a way to manifest the Affordable Indie Uniform, indie consumers connected the brand to the indie look. As such, trend seekers were eager to emphasize the logo and made sure to interact with it in ways that did not obscure it. Furthermore, although some indie consumers, like Malin above, denounced all connections to those who only “buy a brand,” as consistent with Arsel and Thompson’s study of consumers motivated to protect their “field-dependent identity” (2011), others were indifferent to the trend seekers and capitalized on the presence of other indie consumers in valuing the brand.

We draw further from Arsel and Thompson (2011) in explaining indie consumers’ indifference to being symbolically coopted by the trend seekers as the reason our findings contrast with the destabilization in a brand assemblage upon the entry of new components noted by Parmentier and Fischer (2015). Arsel and Thompson (2011) emphasized investments and purposefully difficult access as ways of protecting the cultural capital upon which field-dependent identity depends. Because such investments safely mark distinction from less knowledgeable consumers and tend to have relative longevity, they provide some explanation for the ability of the indie consumer sub-assemblage to passively coexist with the coopting trend seeker sub-assemblage. Moreover, the two sub-assemblages related differently to the indie rock trend; for the trend seeker sub-assemblage, the trend was key for actualizing identity value and social distinction in the form of the Absolutely Latest, whereas for the indie consumer sub-assemblage, it was key for actualizing linking values via communal interests in indie clothing, music, and art. Here the stores were not only points of sale but also hang outs and sources of information (fieldnotes 2006). CM’s signature slim black jeans were important parts of both consumer sub-assemblages, albeit in different ways.

Phase 3: Value Arrangements Preventing the Trend Seekers from Enacting the “Absolutely Latest” (2008–2009)

It feels like something has been lost. The cheekiness or however one should put it. (Christoffer, male, age 25 years)

In this passage, Christoffer, a trend seeker, expresses loss in considering the effects of H&M’s entry into the CM brand assemblage in 2008.

Catalytic Trigger Leading to Value Rearrangements

The third phase was triggered in 2008 when H&M purchased CM and the assemblage destabilized. Their entry was an unlikely experiment in globally commercializing the localized indie sub-assemblage, yet it promised valuable financial resources and brand building expertise in exchange for indie savvy (SVT 2008). The event was promoted by the stewards of both CM and H&M in a joint press release: “The idea behind Cheap Monday is fashion at good prices, something that goes well with H&M’s business idea: fashion and quality at the best price” (H&M 2008).

Value Rearrangements within Consumer Sub-assemblages

Although this made sense from the brand stewards’ perspectives, our consumer interviews showed that the trend seekers were skeptical toward the new value arrangements opening up by the brand stewards’ actions. Like Christoffer above, Noel (male, age 18 years) was among them: “When H&M bought [CM], the collection really changed. […] It’s hard to say what it was, but I guess they became more focused on selling than on innovating.” Indeed, the trend seekers expressed negative feelings over what they interpreted as commercial mainstreaming, as illustrated in the quote from Alexander (male, age 30 years), a former salesperson at CM who also attributed these feelings to a misunderstanding:

Some have started conflating CM and H&M, […] It really bothers me, because they don’t understand the relationship between CM and H&M when it comes to, like, creative direction and independence and the like.

CM’s independence was corroborated by Håkan Ström, who took over as CEO at CM in 2009 and praised H&M for letting CM keep their original spirit intact. “H&M has been extremely understanding all along, they understand that we have a brand that is worth something and that we must preserve the culture…” (Interview).

Nonetheless, the decrease in exclusivity and trendiness experienced by the trend seekers was further emphasized by the retail expansion that followed H&M’s acquisition. Although the original store was on a back street and hard to find and the subsequent stores were in trendy areas, they now expanded to the High Streets. For the trend seekers, these high street locations compromised the value they generated in the boutiques, and to make matters worse, important international stores that legitimized the brand as trendy—Colette in Paris, Selfridges in London, and Fred Segal in West Hollywood—had stopped distributing the brand. Indeed, the high street stores’ material capacities in the form of a well-frequented location and a size for volume sales were not appealing to the trend seekers as they did not offer them the exclusivity they were after. Additionally, the indie trend was gaining mainstream appeal at the time (Abebe 2010), which also cut into its appeal for trend seekers. All in all, these developments reduced the assemblage’s ability to offer the Absolutely Latest to the trend seekers who subsequently left the assemblage to explore trendiness elsewhere.

Relationships among Consumer Sub-assemblages

Although the trend seekers could not reconcile the relative mainstreaming and the threat of mainstream consumers that came with the entrance of H&M and departed, the indie consumers did not seem bothered by H&M’s presence and continued to immerse themselves in their usual subcultural values and practices in relishing indie music and its accouterments. As Håkan Ström notes below, indie consumers maintained a semblance of the DIY ethos from the earlier phase when sewing machines were displayed in the shops and consumers helped out:

Those who worked here, they were also our customers, that’s why we succeeded [We did everything ourselves back then] […] We still don’t have any agency that creates our [advertising campaigns] We [still] do everything ourselves… We sit in the kitchen and talk, and just go […] and all our photo shoots are done by Valle [an indie consumer] who is hardly a photographer, and it gets better and better every time.

To the indie consumers, not much had changed after H&M entered the brand assemblage. Their consumer sub-assemblage remained relatively intact, and Andersson and his group remained prominent as CM continued to operate as an independent subsidiary, with H&M in the background (Håkan Ström, interview; SVT 2008).

Phase 4: Additional Value Arrangements Enabling Fashionistas to Enact the “Alternative Highbrow Fashion” (2009–2011)

She [Ann-Sofie Back] feels very CM. Well, her design feels very CM, the eclectic and the layering. It’s a lot of crazy stuff, weird cuts […] She’s extra-sharp in her own collections, but just transferring a hint of it to CM is pretty important. The reason she’s there is, of course, because she fits the concept so well. (Isabel, female, age 24 years)

Isabel, a fashion blogger, was one of the many fashionistas who instantly reacted to Ann-Sofie Back joining CM in 2009. The key for Isabel when evaluating CM was that Back fit CM well; her provocative designs could help maintain CM’s edge. Back’s “crazy stuff” and “weird cuts” were inspirations for the fashionistas to further explore how CM’s street style could add value to their fashionista identity and related sub-assemblage, which we label “Alternative Highbrow Fashion.”

Catalytic Trigger Leading to Value Rearrangements

To maintain CM’s edge and perhaps offset possible negative influences from H&M’s involvement, the brand stewards brought highly renowned avant-garde fashion designer Ann-Sofie Back to their team in 2009. Back became head codesigner and brand steward alongside Andersson, whereas the intersecting H&M brand assemblage remained in the background. Because of a distinct position in high fashion, Back emerged as a rather foreign component in CM’s overall brand assemblage. She was equipped with two prestigious fashion degrees and several prominent fashion awards. Apart from the handicraft itself, her collections had also won praise for their artistry (Aftonbladet 2014). Besides Back’s solid standing as a high-fashion designer, she had a rough edge that fit CM’s alternative way of approaching the world (Aftonbladet 2014). Isabel, the fashion blogger, captured this alternative way in our interview: “What she [Back] adds is that she really has something to say about fashion. She changes all the time but still keeps her concept intact, and that is just a little, like, crazy and daring. Just what one wants fashion to be!”

Back’s role as a catalytic trigger manifests in her ability to attract fashionistas. The fashionistas joined consumers with a keen interest and knowledge of fashion with high-profile designers, stylists, photographers, journalists, and PR and marketing professionals who contributed screen prints, music, and photo shoots, as well as bloggers who worked and lived fashion. Varied numbers of each showed up at parties wearing CM and other clothing designs in ways that actualized value in the assemblage. Indeed, CM offered them clothing, accessories, and most importantly, opportunities to materialize and express their identities as fashionistas in connection to others. Sara, a designer from Beckman’s School of Design, compared CM’s fashionista circle in Stockholm at the time to The Factory that surrounded Andy Warhol:

She builds a kind of modern Andy Warhol “The Factory” status via the people she surrounds herself and her brands with [both at work and privately]. She wears all her brands herself and also gives them away to these people, stylists, photographers, musicians, artists. She knows exactly how to play on cultural status and includes both those who already are established, smart, and well-read and those who are up and coming. (Sara, female, age 30 years)

According to Sara, CM’s creative team attracted even more qualified and daring fashionistas in a virtuous circle expanding their material capacity and numbers. This was also confirmed by Maria (female, age 30 years), who named prominent artists, DJs, stylists, and musicians who had started to work with CM while also working on other projects in intersecting fashion, art, and music assemblages. What attracted them was Back’s ability to draw in others and arrange the assemblage components in ways that produced the potential for the identity, community, and linking value and careers spanning “Alternative Highbrow Fashion.”

Value Rearrangements within Consumer Sub-assemblages

Alongside H&M and high street locations lingering in an associated sub-assemblage, with Back the fashionistas further explored and materialized value arrangements for the Alternative Highbrow Fashion sub-assemblage in contributing to the CM brand assemblage. The consumer group had, in fact, already started paying interest in the CM assemblage in 2004, because of the similarities they found in CM jeans with those launched by Hedi Slimane for Dior Homme in 2003. Slimane had gained acclaim for replacing the bulky style of the ‘80s and ‘90s, as well as the pumped-up, muscular body that accompanied it, with the slim esthetic and slim body ideal in menswear (Bowstead 2015). This subsequently spread to women’s jeans fashion. Maria, a fashion journalist, expressed relief at finding affordable jeans that conformed to this slim esthetic at the time:

I remember the relief in finding that finally someone is doing this. Because it was the pants we were all looking for. We looked for them everywhere. But there weren’t any reasonably priced pants around that gave us the look we wanted, this tight, skinny, matchstick look. […] I remember I was just so happy! My God, that is so smart, why hasn’t anyone done it before? And since then, I’ve always had a pair of CM in my wardrobe. (female, age 30 years)

Maria’s quote credits the material capacities of the jeans that enabled her body to transform into the slim esthetic that was fashionable at the time, and their expressive capacity to communicate the right sartorial statement. Still, the fashionistas had existed as a marginal consumer component in the CM brand assemblage until Back entered the CM environment and invigorated them as key players in her rendition of “The Factory.” Back continued making her own label, an intersecting assemblage that offered the CM assemblage potential for a high-fashion connection, thus providing the CM assemblage an identity value that was key for the fashionistas. This was reflected by several fashion bloggers around the world after Back’s first collection with CM:

Back’s influence is clear to see. Her own girly goth vibe is weaved throughout the collection with rips, gashes, and holes adorning both jumpers and jeans. The jeans ooze that cool kid about town look. While the jumpers are a perfect choice for our very unpredictable English weather, allowing us to cover up stylishly. (My Fashion Life 2009)

CM’s linkages to high fashion became more pronounced when high-fashion magazines like Vogue (Bumpus 2011; Milligan 2009; Kilcooley-O’Halloran 2014) as well as narrower, more highbrow fashion magazines like S magazine (Cirelli 2011) started to pay attention to CM.

As already indicated, the jeans were part of the value arrangement offering a central identity value for the fashionistas as a Hedi Slimane silhouette at a low price. It was not just any pair of black matchstick jeans. As the fashionista Sara (female, age 30 years) said, “It’s like Balenciaga [a highly acclaimed high-fashion brand], black classics but designed. It is something with the cut that you can’t get elsewhere.” When interacting with the fashionistas, this material capacity of an edgier cut was activated in a way that expressed a more fashion-conscious jean. However, this consumer group preferred the jeans without the label and its symbolic landscape—the label did not contribute to expressing an Alternative Highbrow Fashion identity, rather the opposite. Both Maria (female, age 30 years) and Alexander (male, age 30 years) described how they routinely cut the skull-ornamented patch from the back pocket of their new CM jeans:

[The patch] just didn’t blend with the rest of the jeans, it made you feel like a billboard for CM, without having chosen to. Logos aren’t something I normally shy away from [touches her earrings with Chanel logos], but the CM logo just became so huge. It felt like a cliché that came with all this baggage. (Maria, female, age 30 years)

Although important and highly symbolically charged among the indie consumers, the patch could not offer any value for the fashionistas, who therefore eliminated or deemphasized it. The CM assemblage thus housed two slightly different value arrangements, one catering to the fashionistas as Alternative Highbrow Fashion brand and another catering to the indie consumers as Affordable Indie Uniform, respectively. Among the fashionistas, the symbolic landscape took a back seat, whereas the jeans component activated material capacities that manifested in a specific cut and look and ignited expressive capacities of high-fashion knowledge, albeit with an indie touch. Among the indie consumers, in turn, the jeans component materialized as a street version and activated expressive capacities in the jeans that were rougher than the fashionistas’—but that also went in line with and strengthened Back’s “darker, worn, and deconstructed high-fashion punk style” (Kilcooley-O’Halloran 2014).

Relationships among Consumer Sub-assemblages

We noted already that when a sub-assemblage is in a relationship of cooptation, it exists side by side with another sub-assemblage while appropriating parts of its expressive and/or material character. However, somewhat distinct from the trend seekers’ cooptation of indie, both the indie consumer and fashionista sub-assemblages interacted and invigorated each other. The indie consumers were already acquainted with the fashionistas, who had long been a low-key part of the assemblage but had not actively engaged until now. Moreover, the borders between their respective territories were porous and somewhat overlapping, as materialized in the way both Back and Andersson actively participated in and invigorated both. Their synergy is illustrated in the interview with Carl Malmgren, chief designer of the denim collection: “CM came at a time when [indie] rockers and fashion were attached to each other a bit more. Like it [indie rock] was a really fashionable style then. So that’s why it became popular amongst the fashionistas too.” The close alliance between indie consumers and fashionistas could also be seen at events like Back’s art and CM’s fashion shows—something that continued for a long time, as illustrated by the following fieldnotes from a CM fashion show in 2015 (Stockholm, Sweden):

In the VIP area I, spotted fashionistas dressed in the latest sharply cut black clothes side by side with indie rockers dressed in their uniform of Converse shoes, ripped skinny jeans, thin jackets, and tattoos, greeting each other while being served drinks.

Back thus stood with one foot in each camp—indie and fashion—and had, according to Carl Malmgren, successfully connected the catwalk and the street via her knowledge of and leanings toward both. “If we had looked the same now as we did then, we would not have had the same degree of fashion at all […] So thanks to Ann-Sofie Back, we have been able to develop fashion-wise.” With Back and the fashionistas, CM became “more than just skinny jeans,” according to fashion authorities like Vogue (Kilcooley-O’Halloran 2014). While keeping true to the mainstay skinny jeans, which the Vogue article labeled as “cult,” Back and her team innovated—with the help of H&M resources—new collections and eccentric fashion shows that gained notoriety as art installations (Braunerhielm 2012). While working with CM, Back’s work also was shown in various Swedish art institutions, including Liljevalchs Arthall in 2011, The Röhsska Museum in 2014, Sven Harry’s Art Museum in 2014, and the Stockholm House of Culture in 2015. With these exhibitions, Back became recognized as one of the few fashion designers who managed to balance high culture and commercial popular culture.

Phase 5: Additional Value Arrangements Enabling Mainstream Consumers to Enact a “Safe Choice” (2011–2018)

It’s very mainstream, everyone can go there, but there is still this unspoken feeling of it being a bit alternative. […] And that is what you want to get at (David, male, age 25 years).

David was a mainstream consumer attracted to CM’s ability to balance edge with a safe fashion choice, as he positioned himself in the mainstream while expressing some alternative esthetics. This broader appeal with an edge was something that the mainstream consumers could actualize in the CM brand assemblage when H&M moved into the foreground in 2011.

Catalytic Trigger Leading to Value Rearrangements

The fifth phase was ignited in 2011 when Andersson and the other founders left CM after selling the rest of their shares to H&M. Their departure was the catalytic trigger that moved H&M to the foreground alongside Back, and the financial resources and global mainstream associations H&M brought aided the CM brand assemblage. Back had etched this broader appeal as well since moving to Sweden and there discovering that she could make clothes with material capacities that were “worn by others than herself and a few Japanese stylists,” as she explained, “Before, in London, I only saw fashion people wearing my stuff. But since I came here [to Stockholm], I’ve seen ordinary people on the street wearing my clothes and it’s really great that that’s the case. It’s a kick to see that the clothes actually work” (quoted in Suarez-Golborne 2009). The industry informant Pär Engsheden, Program Director at Beckmans College of Design in Stockholm and a renowned designer in his own right, featured Back among the new generation of Swedish fashion designers for whom mainstream success was not antithetical to their position in high-fashion circles. As an acclaimed fashion designer, Back was a pioneer in igniting the expressive capacities of high-fashion and mainstream appeal. During her tenure with CM, Back received additional prestigious fashion prizes, including her third Fashion Designer of the Year award by the magazine Elle (2013) and the Torsten and Wanja Söderberg Prize for Nordic designers (2014), valued at one million SEK ($120,000 USD). The awards affirmed Back’s capacity to link fashion with commercial success: “With continuity, while maintaining distance, she has over time been able to prove that having faith in the esthetics of resistance makes it possible to create fashion that is both commercial and expressive” (Röhsska Museum 2014). Together, Back and H&M invited the CM assemblage to open up to the mainstream.

Value Rearrangements within Consumer Sub-assemblages

Even if the mainstream consumers did not know who Back was, they were drawn into the high street stores by the fashionistas’ presence. The copresence of the fashionistas and the high street vibe gave the mainstream consumers a chance to explore an identity value that balanced between edge and safety with the help of the CM brand. When talking about what CM stood for, Filip (male, age 25 years) elaborated this balance: “[CM] are in a pretty good borderland, they are open for everyone, but still a bit edgy.” The quote exposed Filip’s interest in fashion and CM’s ability to match this by being a bit more progressive than typical brands catering to the mainstream. The more extreme clothes in the CM collection had an expressive capacity to shout “Fashion!” for the mainstream consumers Filip and David above, with the material capacity to draw them into the stores—although these were not the clothes that mainstream consumers bought. Even if CM’s edge was accessible, consumers like Filip did not have the desire to express this type of edge. CM’s connection to edge sufficed and also made its less-edgy clothes a safe fashion choice, enabling them to express an adequately conformist identity. David said, “At H&M, one can go in and say that these clothes are ugly, but at [CM] you don’t really know, because [they might have been made by] some fashion guru who knows more than you do.” Indeed, the material and expressive presence of the fashionistas and the unique style sensibilities of the store personnel were evident for mainstream consumers interacting in the stores.

As the rapid expansion of the company and the increased mainstreaming of operations gradually lessened the rough edges, the more edgy brand components, including the indie music scene, indie artists, ideas of the occult, and fashion professionals, started to withdraw from the brand assemblage, watering it down and causing further mainstreaming toward the end of the period. This was consistent with the interests of the mainstream consumers who were mostly looking for the classic skinny jeans that provided the material and expressive safety that they were after. Tony, a store manager in London, described the mainstream consumer as one who “mostly buys the T-shirt with the skull [logo] and skinny black or blue jeans.” Besides the expressive capacity to help consumers fit in fashionwise, the jeans also had material corset-like capacities that could make its wearer appear, or at least feel, skinnier. In societies that have celebrated the skinny silhouette since the early 1900s (Stearns 2002), this further reinforced in the assemblage the ability to deliver identity value in the form of “fitting in” and “being safe.” Malin (interview 2014, female, age 33 years) noted that the jeans could fit anyone between 12 and 60 years old, thanks to their exceptionally stretchy material, and Isabel (female, age 24 years) underlined the material inclusiveness as well: “They looked equally good on all, independent of body type. […] I knew that this was something people had been looking and longing for, but not found [until CM appeared].” Even as the market filled with more brands, “CM remained the perfect silhouette,” as Maria (female, age 30 years) put it.

Mainstream consumers interacted with the CM jeans much like Miller and Woodward (2012) had observed with blue jeans, namely, not to stand out, but to avoid a fashion faux pas. Over the years, skinny jeans had come to express a standard outfit and thus provided mainstream consumers a way to “fit in.” Our informant Alexander (male, age 30 years) noted that “[skinny jeans] have become so well established that it’s hardly fashion anymore, but rather a standard garment.” Every season, fashion journalists heralded their demise and instead pushed for boyfriend jeans, flared jeans, or something else. But the skinny jeans stayed on, much to the annoyance of the fashion industry that prefers changing consumer preferences to drive sales (Rupp and Kaplan 2016). Together with the jeans and a subset of components of the brand assemblage, the mainstream consumers assembled a value arrangement that enabled them to enact a Safe Choice, providing them with value in fitting in.

Relationships among Consumer Sub-assemblages