-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Minh Hao Nguyen, Eszter Hargittai, Digital disconnection, digital inequality, and subjective well-being: a mobile experience sampling study, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 29, Issue 1, January 2024, zmad044, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad044

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Drawing on theories of digital media (non-)use and well-being, this study examines how voluntary disconnection relates to subjective well-being and what role digital skills play in this relationship. We rely on mobile experience sampling methods to link nuanced disconnection practices throughout the day (e.g., putting screen devices away and muting notifications) with momentary experiences of well-being. We collected 4,028 responses from 105 mobile media users over the course of one week. Multilevel regression analyses revealed neither significant within-person effects of disconnection on affective well-being, social connectedness, or life satisfaction, nor a significant moderation effect of digital skills. Exploratory analyses, however, show that effects of disconnection on well-being vary greatly across participants, and that effects are dependent on whether one disconnects in the physical copresence of others. Our study offers a refined perspective on the consequences, or lack thereof, of deliberate non-use of technology in the digital age.

Lay Summary

This study looked at whether taking breaks from digital media throughout the day has an impact on people’s own perceptions of their well-being. Over the course of one week, the researchers asked 105 participants to answer six questionnaires each day through a mobile application, which resulted in 4,028 filled-out questionnaires. The results show that, on average, taking a break from digital media does not affect how people feel (positively or negatively), or how socially connected they feel immediately after their disconnection. It also does not affect how satisfied they are with their life considering the past day. However, upon further analysis, the results show that people’s reactions to breaks from technology vary greatly. Some people experience no or negative effects of disconnection on their well-being, while others experience positive effects. The study also finds that when people take a break from digital media while being with others, this has short-term positive effects on their well-being. With this, the study shows a nuanced picture of the benefits—or lack of these—of what taking breaks from digital media can do for people’s well-being.

In today’s “permanently online, permanently connected” world (Vorderer et al., 2017), people increasingly make purposeful efforts to disconnect, such as by limiting their connectivity or time spent on digital media (Nguyen et al., 2022). For instance, individuals might take “digital detoxes” and use tech-based solutions such as apps and device features to unplug (Nguyen, 2021). Societal norms toward disconnection might also develop, as social groups and organizations implement guidelines and policies around digital media use (Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2023). Research reveals that well-being and health considerations are one of the central reasons why people decide to place limits on their digital media use or to “disconnect” (Jorge, 2019; Nguyen, 2023). Yet, in current scholarship on digital media use and its impact on subjective well-being, the role of everyday digital media practices that are geared toward limiting connectivity remains understudied. Exceptions to this are intervention studies where people are asked to take breaks from social media or mobile devices, but these do not reflect people’s everyday lived experiences (e.g., Hall et al., 2021; for a systematic review, see Radtke et al., 2021). As such, research has not yet been able to address to what extent disconnection is able to restore people’s sense of well-being, which is perceived to be threatened by digital media use (Nguyen, 2023). Note that ample research has been conducted on the relationship between digital media use and subjective well-being, finding mostly none to small effects (for a review, see Meier & Reinecke, 2020; for a discussion, see Orben, 2020), but individual perceptions that digital media affects well-being negatively still remain (e.g., Comparis, 2018; Kantar, 2018). Since well-being considerations are one of the key motivations to disconnect (Nguyen, 2023), it is important to examine if disconnection—that is, deliberately limiting the use of digital media—is an effective strategy to restore such perceptions of reduced well-being.

Another important question is to what extent digital inequalities shape the relationship between digital disconnection and subjective well-being. In recent years, scholars have voiced concerns about how digital inequalities may extend to the realm of digital disconnection, putting forward the notion that some might be better able to manage the abundant digital information and communication environment than others (e.g., Gui & Büchi, 2021; Hargittai & Micheli, 2019; Nguyen, 2021; Nguyen & Hargittai, 2023). In a world where connection is the default, disconnection may be reserved for the more digitally and socioeconomically privileged, who are able to “afford” going offline (Beattie & Cassidy, 2020; Büchi et al., 2019). With many disconnective features being built into device and app interfaces (e.g., Apple Screen Time, “Focus” mode), it is likely that these will be more accessible to those who are digitally skilled enough to utilize them (Nguyen, 2021). Overall, digital inequality research has shown that more skilled digital media users are more likely to experience benefits from their digital media uses, for instance, in terms of increased social capital or well-being (Hofer et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2020). As such, an important question is whether and how digital skills play a moderating role in the relationship between everyday digital disconnection practices and subjective well-being.

In this preregistered study, we examine the implications of people’s everyday disconnection practices for their sense of well-being (i.e., affective, social, and cognitive well-being), and how digital skills play a role in this. We aim to explore people’s broader digital media repertoire instead of only focusing on specific devices or platforms, as digital media use and henceforth disconnection likely does not happen in an isolated context (e.g., Nguyen et al., 2021). Regarding digital disconnection, we aim to capture the everyday practices in which people engage while maintaining connectivity—but without going completely offline for longer periods of time, such as in the case of digital detoxes where users take longer breaks (e.g., weeks and months) from mobile or social media (Baym et al., 2020; Franks et al., 2018; Radtke et al., 2021). To capture these everyday disconnection practices in their natural setting—as opposed to intervention studies that “force” participants to disconnect—this study employs an experience sampling method (ESM) design where digital media users are surveyed six times throughout the day over the course of a week to capture their possible disconnection practices as they occur naturally. The unique advantage of ESM in the context of this study is that it can capture (a) the nuanced disconnection practices in which people engage throughout the day (e.g., putting the phone with the screen down for several minutes; making a mental note not to visit certain apps or websites) and (b) the momentary, likely short-lived, effects of such nuanced disconnection practices on subjective well-being.

Theorizing the relationship between disconnection and subjective well-being

Digital media play an essential role in organizing everyday life, maintaining social relationships, and fulfilling leisure time, and as such may be important for nourishing affective, cognitive, and social well-being outcomes (Meier & Reinecke, 2020). It is not surprising that decades of research have been concerned with the question of how digital media use affects people’s subjective well-being (for a review, see Meier & Reinecke, 2020). With respect to the impact of digital disconnection on various dimensions of subjective well-being, there are several hypotheses to consider. As a starting point, we first discuss existing theories about the relationship between digital media use and well-being, and then elaborate on what this would mean for potential effects of disconnection on different well-being outcomes. In this study, we define digital disconnection as nuanced acts of deliberately limiting one’s digital media use (e.g., putting devices away, making mental notes not to look at devices, turning off notifications or the internet). Overall, it is important to note that digital disconnection and its potential consequences for well-being might differ depending on geographic and cultural context (Bozan & Treré, 2023; Treré, 2021). Much of the disconnection literature so far (for a review, see Nassen et al., 2023), as this study, has been focused on Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries (Henrich et al., 2010), where dis/connectivity for many is likely a choice rather than a necessity (also see the Discussion and Conclusion section).

On the one hand, scholarship has theorized digital media use to have a positive effect on well-being. For instance, digital media such as smartphones can help young people develop a sense of autonomy (Schnauber-Stockmann et al., 2021) and can support older adults in living an autonomous life (Abascal & Civit, 2000), which are fundamental human needs that contribute to overall well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001). With respect to digital communication, researchers have suggested that both the quantity and quality of human communication can be improved through use of technology, which in turn contributes to greater social connection and overall well-being (Dienlin et al., 2017; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). If we think of digital media use, that is, connection, as having positive effects on subjective well-being, then one hypothesis could be that disconnection interferes with this relationship and thus negatively impacts well-being.

On the other hand, digital media use may also have negative consequences for subjective well-being. For instance, a well-known hypothesis is that of “displacement” (Dienlin et al., 2017; Kraut et al., 1998; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007), whereby time spent on digital media detracts from time that could be spent on other potentially more meaningful activities, including in-person social ones. For instance, in the case of problematic social media use—when people feel a loss of control over their social media use or experience “overconnection”—research has shown that it can lead to increased loneliness (Marttila et al., 2021) and is thus detrimental to one’s well-being. Digital media have also been experienced as distracting, leading to unwanted effects such as procrastination (Hinsch & Sheldon, 2013; Meier, 2021). Disconnection, then, could be a solution to such perceived negative effects and allow people to spend their free time on other activities that are perceived to be more meaningful, all the while regaining a sense of control over their digital media use (Aranda & Baig, 2018; Franks et al., 2018; Nguyen, 2021).

So far, in theorizing the relationship between digital disconnection and subjective well-being, we have given examples in which we think of disconnection as the reverse of connection, and likewise the effects it may have on subjective well-being. While this might seem logical and straightforward, we argue that effects of digital disconnection on well-being are not necessarily the opposite of those of digital media use. Unlike digital media use, which is often described as automatic, habitual (Bayer et al., 2022; Giannakos et al., 2013; Wohn, 2012) and perhaps even as mindless (Baym et al., 2020; Schellewald, 2021), when it comes to disconnection practices, people engage in them more consciously and in a goal-oriented manner (Aranda & Baig, 2018; Franks et al., 2018; Nguyen, 2021). Through disconnecting, people often hope to achieve something specific, such as being more present in offline activities, not being distracted when wanting to concentrate on an activity, or escaping the social pressure to be online (Nguyen, 2023). These observations are in line with Communication Bond Belong theory, which posits that the motivation to engage in social interactions decreases when the need to belong is fulfilled, and vice versa, because social interactions come at the expense of social energy, which people need to preserve (Hall & Davis, 2017). Recently, scholars have linked this theory to the concept of digital solitude (Campbell & Ross, 2022), suggesting that when people actively decide to disconnect, this can help them regain their social energy (Ross et al., 2023). From the various points of view discussed, it would make sense to expect that, overall, people’s disconnection practices have a positive impact on well-being in general. Nonetheless, it is important to note that digital media use itself (rather than disconnection) can also be practiced as a moment of digital solitude, for instance when someone uses social media by oneself for a moment of relaxation or to cope with offline stress (Keessen, 2023; Wolfers & Utz, 2022), and so the relationship of disconnection to well-being may not be that straightforward.

What does existing empirical scholarship on digital disconnection have to say about its effects on subjective well-being? Research on the relationship between disconnection and subjective well-being has so far mostly been of experimental nature, where participants are instructed to abstain from social media or their smartphones for a certain time period. Overall, the results of such studies are mixed: Some find positive effects on affective, cognitive, and social well-being outcomes, while others find no such effects, or even negative ones (for a systematic review, see Radtke et al., 2021). In one of the most comprehensive studies to date, Hall et al. (2021) randomly assigned participants to one of five experimental conditions in which they were either asked to make no changes to their social media use or take a break from social media ranging from 1 to 4 weeks. Relying on daily diary assessments, the authors found no effect of abstention nor the duration of abstinence on affective, social, or cognitive dimensions of subjective well-being.

Aside from intervention studies, there is also research that relies on participants’ recall of their disconnection experiences. For instance, in a study where researchers collected open survey responses, Facebook users reported that after a time of deactivation, they returned to be more mindful users of the platform (Baym et al., 2020). Cross-sectional survey research has shown that intended unavailability to communicate with others (either in person or digitally) can increase overall well-being, but only for users who are more digitally connected than others (Ross et al., 2023). An interview study found that taking breaks from social media could benefit people’s sense of health and well-being, although this was not the case for all interviewed participants (Nguyen, 2021). On the whole, while experimental studies show mixed effects of forced disconnection from social media/mobile phones on subjective well-being (e.g., Radtke et al., 2021), interview studies that ask about voluntary disconnection experiences in retrospect report overall benefits for perceived well-being (Aranda & Baig, 2018; Baym et al., 2020; Franks et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2020). This leaves the question of whether method of analysis may influence how disconnection and well-being are linked.

Observational studies that focus on the effects of disconnection strategies implemented in day-to-day life on subjective well-being (unlike forced “detoxes” where people opt out of social media for a certain time period due to researcher prompting) are less present in the literature. Yet, such everyday disconnection practices are quite common and, as such, are ripe for investigation. For instance, research from Switzerland indicates that two-thirds of digital media users engage in at least one strategy to disconnect (e.g., turning off notifications, using do-not-disturb-functions, or putting digital devices away), with health and well-being among the most prominent reasons listed for doing so (Nguyen et al., 2022). In an Austrian study of people ages 18–35, almost half used screen time apps on their smartphone (Schmuck, 2020). Moreover, among people who do not use screen time apps, social network site use was positively associated with problematic smartphone use, and consequently, lower subjective well-being, while there was no such link among screen time app users (Schmuck, 2020). As such, it could be that engaging in efforts to regulate one’s media use can mitigate potential negative effects of digital media use on subjective well-being. While these studies are helpful as a first step, more research is needed to deepen our understanding of the possible effectiveness of everyday disconnection practices for subjective well-being.

Momentary effects of disconnection on subjective well-being

Given that people often engage in disconnection practices consciously and with a specific goal in mind (e.g., being more present in offline activities; Aranda & Baig, 2018; Franks et al., 2018; Nguyen, 2021), we expect that the effects on affective and cognitive well-being overall will be positive. However, when it comes to social well-being, existing empirical work seems to suggest that in the short-term, disconnection can lead to diminished feelings of connectedness. Nguyen (2021) found this to be the case in an interview study with 30 adults who had taken a break from social media at least once. People’s overall, long-term reflections were positive and reflected increased well-being, whereas short-term, they had reported negative effects on social well-being, such as fear of missing out and restlessness when they decided to deactivate Facebook or put their mobile phone away (Nguyen, 2021).

When comparing experimental studies in which people were asked to disconnect from social media, a one-week intervention yielded an increase in social connectedness (Brown & Kuss, 2020), while another study with a shorter two-day intervention led to lower connectedness (Sheldon et al., 2011), although the latter finding likely does not reflect momentary effects. A comprehensive study which compared different lengths of social media breaks (ranging from 0 to 4 weeks) found no effects of the duration of abstinence on loneliness (Hall et al., 2021). Research using the ESM to examine communication between close ties (e.g., couples) has shown that connected availability—the perception that a partner is continuously available digitally—benefits subjective well-being (Taylor & Bazarova, 2021). Theoretically, disconnection then could be detrimental to feelings of social connectedness—at least in the short term, as it interferes with this state of “connected presence” (Christensen, 2009; Licoppe, 2004) to others at all times. In the context of in-person social interactions, however, phubbing—interrupting a social situation through smartphone use—can lead to detrimental well-being (Nuñez & Radtke, 2023). Disconnection, then, could increase especially perceived social well-being. As an observational study showed, people experienced more intimate conversations when smartphones were used less (Vanden Abeele et al., 2019).

This study aims to examine the momentary effects of people’s disconnection practices throughout the day on three dimensions of subjective well-being: affective (i.e., positive/negative mood), cognitive (i.e., life satisfaction), and social (i.e., social connectedness), as these can be considered the core elements of general well-being (Andrews & McKennell, 1980; Diener et al., 2009). In the case of such everyday disconnection practices (e.g., putting the phone away or turning off the internet for a short time period), effects on subjective well-being indicators may be short-lived and limited to how one feels in the moment, thus requiring momentary assessment methods to capture. Our aim is to include people’s broader digital media repertoire, thus focusing on devices that grant access to the internet, such as a smartphone, laptop/computer, or tablet, and the apps and programs that one can use through them. Inspired by current theorizing and empirical work in the area of digital media use, digital disconnection, and well-being, we expect that engaging in disconnection practices will benefit affective and cognitive well-being in particular. However, for social well-being, we expect negative effects in the short-term. As such, we formulate the following hypotheses:1

H1: Everyday disconnection practices are related to higher perceived affective well-being.

H2: Everyday disconnection practices are related to higher perceived cognitive well-being.

H3: Everyday disconnection practices are related to lower perceived social well-being.

Digital inequalities in disconnection: the role of digital skills

Scholars have suggested that socio-digital inequalities exist around people’s disconnection practices and have highlighted the importance of digital skills—that is, the ability to use technology effectively and efficiently (Hargittai & Hsieh, 2012)—in managing the abundant information and communication that people are exposed to through digital media (Gui et al., 2017; Hargittai et al., 2012; Hargittai & Micheli, 2019). A survey of American internet users revealed that people with greater digital skills were more likely to use strategies to limit their digital media use during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nguyen & Hargittai, 2023). Qualitative interview studies have also reported that digital skills are important for being able to use features of technology to limit connectivity (Nguyen, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). Examples of such strategies include the use of screen time apps to track and set limits to one’s digital media use, as well as the use of app and device settings to manage one’s online availability or exposure to online information and communication. Overall, since evidence of an association between digital skills and disconnection behaviors is still scarce, a first question that we will explore in this article is whether people’s digital skills predict the extent to which they engage in nuanced disconnection practices throughout the day.

While previous research has established that digital inequalities in people’s disconnection behaviors exist, the extended question of whether this results in differentiated benefits derived from such deliberate non-use remains unanswered to date. This focus on disparities in the benefits that people are able to derive from technology use is an important aspect of digital inequality (Hargittai, 2008): Digital inequality research suggests that in order for people to reap the benefits from using digital media, people need to possess the skills needed to capitalize on such use (DiMaggio et al., 2004). For instance, research on digital media use and social and cognitive well-being in older adults reveals a positive relationship, which was stronger for those with greater digital skills (Hofer et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2020), indicating that digital skills are an important moderator of media effects. This suggests that people with adequate digital skills can mobilize technology use for greater benefits—meaning that more digitally privileged people might disproportionally profit from engaging in digital activities. Given the importance of digital skills for engaging in disconnection practices (Nguyen & Hargittai, 2023), the question of whether such differences also extend to the benefits that people potentially derive from such disconnection is a highly relevant one. In this study, we also explore the role of digital skills for the benefits that people reap from digital disconnection in terms of their subjective well-being. Here, we ask the following research questions:

RQ1: Do digital skills predict people’s engagement in disconnection practices?2

RQ2: Do digital skills moderate the relationships between digital disconnection and (a) affective, (b) cognitive, and (c) social well-being?

Methods

In this preregistered study, we use ESM (for more information about this method, see Myin-Germeys & Kuppens, 2022) to examine the effects of everyday disconnection practices on three different dimensions of subjective well-being: affective, cognitive, and social. We also examine how these relationships are dependent on people’s digital skills. ESM is an appropriate method to examine the occurrence of everyday disconnection practices that happen throughout the day, as well as the immediate, momentary, short-lived effects that it may have on subjective well-being. The hypotheses, research questions, design, and analytical plan were preregistered (https://osf.io/6kw9c).

Design and sampling plan

We recruited Dutch participants 18 years and older through a market research company in March and April 2022. We aimed for a somewhat equal distribution of gender, age, and education levels, which the research company took into account in sending out invitations. Prospective participants received an invitation e-mail from the research company with the study information letter and a link to the informed consent form and intake questionnaire. In the study information letter, we explained the study procedure and that people needed to possess an Android smartphone and install the mobile experience sampling app (movisensXS) to participate. On day 1, participants received an intake questionnaire to measure sociodemographics and general digital media use. Through this intake survey, participants also received step-by-step instructions to install the movisensXS app. We also gaveinstructions to change device settings to receive questionnaire notifications from the app, even in “do-not-disturb” mode (this is a default option of the app, which is needed so that it can function properly).

On days 2–8 (i.e., 7 consecutive days), participants received six questionnaires each day through movisensXS at semi-random time intervals between 8:30 am and 9:00 pm (see exact sampling schedule in preregistration). Given that our questions (see “Daily ESM Questionnaire”) asked about the preceding 2-hr time window for several questions, we ensured that all questionnaire prompts were at least 2 hr apart to avoid overlap in the 2-hr time windows. In total, participants received 42 questionnaires through the app. For most participants (99 out of 105) we needed to extend the ESM part of the study (by 1 day n = 64; 2 days n = 12; 3 days n = 10; 4 days n = 6; 5 days n = 5; 6 days n = 2), either because they had missed questionnaires on the first days due to unforeseen technical issues or because of personal reasons such as illness (see under the Analyses section that the day of measurement did not influence the results). For those willing to continue their participation in the study in spite of this, we sampled until they filled out at least 33 questionnaires (which was one of our inclusion criteria in the preregistration based on power calculations). On the 9th day, participants received a final outtake questionnaire (these data are not part of this article). Participants received a financial compensation of 25 Euros upon completion of the study if they filled out the intake and final questionnaire, and if they filled out at least 80% of the ESM questionnaires (i.e., a minimum of 33), with at least one each day.

Participants were instructed to fill out the questionnaire as soon as possible after receiving a notification, but it stayed available for 30 min after the first prompt. Alternatively, participants could delay the notification up until 25 min later, or they could skip the questionnaire. Participants received four reminder notifications if they had not filled out the questionnaire in those 30 min. Given this study’s focus on disconnection practices, it is important to note that the mobile experience app also worked offline (i.e., when there was no internet connection). The app would then upload the results to the server once the participant again had an active internet connection.

The irony of using mobile media to study disconnection practices is not lost on the authors. We nonetheless believe that this is still an appropriate method to study this behavior, as we do not expect to include participants who disconnect from their phone for longer periods of time (i.e., days, weeks). Instead, we focus on the brief, nuanced disconnection practices that active digital media users engage in throughout the day. Extended disconnection is quite rare, and likely limited to a select group of people who are extremely serious about disconnecting (Nguyen, 2021).

Participants

In total, 151 people signed through the experience sampling app, of which n = 14 never filled out any questionnaires, and n = 32 ended their participation early. Our final sample consisted of 105 participants, of which two-thirds were female (68.6%). The average age of participants was 40.10 years (SD = 13.10) and ranged from 19 to 75 years. The sample included both lower educated (50.5%) and higher educated participants who had earned at least a Bachelor’s degree (49.5%).

In total, we sent 5055 ESM questionnaires to our 105 participants, of which they filled out 4028 (79.7%). On average, participants completed 38.4 ESM questionnaires (range 32–42). Note that we had an inclusion criterion of filling out at least 33 ESM questionnaires to be included in the final sample of our study (for more detailed information on the rationale behind this decision, see our preregistration). However, as two participants started, but did not finish the 33rd questionnaire, we ended up including all participants who completed 32 questionnaires.

Baseline questionnaire

Sociodemographics

We measured age by asking for people’s birth year and subtracting that from 2022. We asked about gender (female, male, other), which we recoded into a female category (vs. other). We measured education level through nine categories, ranging from no formal education to having obtained an academic degree, which we recoded into a dichotomous variable reflecting higher education level (i.e., university versus all lower education categories).

General digital media use

We asked about people’s use of the internet and their smartphones separately, distinguishing between weekdays and the weekend, which resulted in four items. The question was: “On an average [weekday/Saturday or Sunday], how often do you use [the internet, either on a computer, tablet, or smartphone/your smartphone]?”. We calculated the average use per day by taking the sum of the weekday answer * 5 days and the weekend answer * 2 days, and dividing this by 7 days, resulting in two variables separately reflecting average internet use and smartphone use per day. On average, participants used the internet for 4.20 hr per day (SD = 1.43), and their smartphone for 3.35 hr per day (SD = 1.61).

Digital skills

For digital skills, we used an established and validated index to measure people’s know-how about the internet and social media (Hargittai, 2020; Hargittai & Hsieh, 2012). This self-reported index has partly been validated against people’s actual performance of skills (Hargittai, 2005). Respondents reported their understanding of 12 internet and social media-related items on a 1–5 point scale ranging from no understanding to full understanding (e.g., “PDF,” “cache,” “followers,” “tagging”). We took the average of the items as the digital skills score (Cronbach’s α = 0.87). The average level of digital skills was relatively high, but people with lower levels of skills were also represented in the sample (M = 3.88, SD = 0.78, range 1–5).

Daily ESM questionnaire

Disconnection

We pretested the question and answer options for measuring disconnection (n = 9) for clarity, comprehensibility, and completeness during a pilot of the study procedure and made several adjustments before finalizing the version presented here. To measure disconnection practices in everyday life, we asked people: “In the past two hours, have you done any of the following deliberately to take a break from digital media? Check all that apply.” We communicated to participants that digital media entailed “devices that grant access to the internet, such as a smartphone, laptop/computer, or tablet.” The nine answer options were: (a) put my mobile phone or other digital media away; (b) put my mobile phone or other digital media with the screen facing down; (c) told myself not to look at my mobile phone or other digital media; (d) told myself not to look at certain websites or apps (for instance, email, news, and social media); (e) closed programs, apps, and websites (for instance, email, news, and social media); f) turned off notifications (for instance from email, news, and social media); (g) turned off the internet (for instance, flight mode, “do-not-disturb” function); (h) took a break from digital media in another way; and (i) limited digital media use without any special approach. At the end of the list, we included a 10th option for people to report that they had not disconnected in the past 2 hr: “I have NOT taken a break from digital media in the past two hours.”

Confirmatory factor analyses (using the R package lavaan; Rosseel et al., 2023) relying on tetrachoric correlations suitable for dichotomous variables showed an acceptable model fit (χ2(27, N = 3972) = 308.92, P < .001, CFI = 0.800, RMSEA = 0.051; Hooper et al., 2008), justifying our decision to combine the nine items for measuring disconnection into one index. Thus, for our analyses, we created a dichotomous variable reflecting whether people had disconnected in the past 2 hr (versus not). If people indicated that they had used one of the disconnection strategies while simultaneously reporting that they had not disconnected in the past two hours, we recoded their responses as missing since those answers are logically misaligned.

If people had indicated that they had disconnected, we also collected data on whom they were with when they disconnected. Answer options were: alone, partner, child(ren), other family, friend(s), colleague(s), and other; people could select multiple answer options. For the analyses, we created a dichotomous variable for each type of social tie. We also created another dichotomous variable to reflect whether people had disconnected in the copresence of other(s) (1) versus while alone (0).

Subjective well-being

We focused on three dimensions of subjective well-being, namely affective, cognitive, and social well-being. We measured affective and social well-being at every occasion, that is, six times per day. Given that we expected less variability during the day in cognitive well-being than other dimensions of subjective well-being (de Vries et al., 2021), we asked this only once: in the last questionnaire of each day. We used one-item measures for these constructs, which is common in experience sampling research to lower participant burden.

We conceptualized affective well-being as people’s experience of negative and positive emotions or mood. To capture affective well-being, we asked: “How do you feel at this moment?”, with answer options ranging from 1 “Very negative” to 7 “Very positive” (de Vries et al., 2021). We conceptualized cognitive well-being as one’s general satisfaction with life, and asked: “When you look at the past day, how satisfied are you with your life at this moment?” Participants could answer on a slider ranging from 1 “Very unsatisfied” to 100 “Very satisfied” (de Vries et al., 2021). We used a slider with a larger range, as this has been shown to be a reliable and valid method to assess constructs related to overall quality of life, such as life satisfaction (Benrud-Larson et al., 2005; de Boer et al., 2004). Finally, we conceptualized social well-being as people’s sense of social connectedness, where we asked: “How socially connected do you feel at this moment?,” with answer options ranging from 1 “Not at all” to 7 “Very much” (Arjmand et al., 2021).

Analyses

We first conducted exploratory analyses to look into the prevalence of disconnection practices across our sample, as well as how sociodemographics, digital experiences, and digital skills (RQ1) related to disconnection practices. Here, we used mixed effects logistic regression to model binary outcome variables, with a random intercept varying by participant. The outcome variables were disconnection behavior in the past two hours (yes/no), and whom they were with when they disconnected (dichotomous variable for each type of social company: alone, partner, child(ren), other family, friend(s), colleague(s), and other).

Next, we tested the hypotheses with multilevel linear regression modeling to account for the nested structure of the data. We estimated two-level models in which repeated measurements of digital disconnection (level 1) are nested within individuals (level 2). To test H1, H2, and H3, we estimated separate models for each dependent variable (affective, cognitive, and social well-being). For affective and social well-being as outcomes, which were measured at six times daily, we estimated a fixed-effects model with disconnection as predictor. For cognitive well-being, which was measured once per day, we estimated a fixed-effects model with the sum score of total disconnection during the day as predictor. We conducted additional exploratory analyses to examine if the within-person effects of digital disconnection on subjective well-being (H1–H3) differ across individuals. To do so, we extended each model with a random slope and tested if the model fit improved when doing so.

To answer RQ2, we extended each of the aforementioned models with an interaction term between digital skills and disconnection. We also conducted all analyses with age, gender, education level, and general digital media use as control variables. Since these were not significant, we report the analyses without them. We also considered the measurement day type (weekday versus weekend) and whether it was the 1st–6th questionnaire of the day, but given that these showed no effect on the dependent variables, we excluded them from further analyses. The time-level variables (level 1) were person-mean centered as we are interested in the within-subject effects. The individual-level variables of digital skills and general media use (level 2) were grand-mean centered. All analyses were conducted in R, using package lme4 (Bates et al., 2022) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., 2020).

Results

Disconnection practices (exploratory analyses and RQ1)

Table 1 displays the prevalence of disconnection practices. In 39.5% (n = 1,567) of completed ESM questionnaires, participants indicated that they had used at least one of the listed disconnection strategies in the preceding two hours. Recall that the question asked whether participants had engaged in these actions “deliberately to take a break from digital media.” The most commonly used strategies were “Put my mobile phone or other digital media away” (23.4%, n = 928), “Put my mobile phone or other digital media with the screen facing down” (7.4%, n = 295), and “Limited digital media use without any special approach” (7.6%, n = 303). Participants, when they had disconnected, used on average 1.36 strategies (SD = 0.77) with a range of 1–8 strategies. Specifically, in 75.4% (n = 1,182) of filled-out ESM questionnaires where people said they had disconnected, only one strategy was used, followed by 17.5% (n = 274) with two strategies, and 4.9% (n = 76) with three strategies.

| . | % . | n . |

|---|---|---|

| Any disconnection practice | 39.5 | 1,567 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media away | 23.4 | 928 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media with the screen facing down | 7.4 | 295 |

| Told myself not to look at my mobile phone or other digital media | 4.7 | 187 |

| Told myself not to look on certain websites or apps (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.3 | 53 |

| Closed programs, apps and websites (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.5 | 59 |

| Turned off notifications (e.g., from email, news, and social media) | 2.7 | 108 |

| Turned off the internet (e.g., flight mode, “do-not-disturb” function) | 1.9 | 76 |

| Took a break from digital media in another way | 3.0 | 118 |

| Limited digital media use without any special approach | 7.6 | 303 |

| I have NOT taken a break from digital media in the past 2 hr | 60.5 | 2,405 |

| . | % . | n . |

|---|---|---|

| Any disconnection practice | 39.5 | 1,567 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media away | 23.4 | 928 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media with the screen facing down | 7.4 | 295 |

| Told myself not to look at my mobile phone or other digital media | 4.7 | 187 |

| Told myself not to look on certain websites or apps (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.3 | 53 |

| Closed programs, apps and websites (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.5 | 59 |

| Turned off notifications (e.g., from email, news, and social media) | 2.7 | 108 |

| Turned off the internet (e.g., flight mode, “do-not-disturb” function) | 1.9 | 76 |

| Took a break from digital media in another way | 3.0 | 118 |

| Limited digital media use without any special approach | 7.6 | 303 |

| I have NOT taken a break from digital media in the past 2 hr | 60.5 | 2,405 |

Note: Data from 105 participants with 3,972 valid responses to the question about disconnection.

| . | % . | n . |

|---|---|---|

| Any disconnection practice | 39.5 | 1,567 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media away | 23.4 | 928 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media with the screen facing down | 7.4 | 295 |

| Told myself not to look at my mobile phone or other digital media | 4.7 | 187 |

| Told myself not to look on certain websites or apps (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.3 | 53 |

| Closed programs, apps and websites (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.5 | 59 |

| Turned off notifications (e.g., from email, news, and social media) | 2.7 | 108 |

| Turned off the internet (e.g., flight mode, “do-not-disturb” function) | 1.9 | 76 |

| Took a break from digital media in another way | 3.0 | 118 |

| Limited digital media use without any special approach | 7.6 | 303 |

| I have NOT taken a break from digital media in the past 2 hr | 60.5 | 2,405 |

| . | % . | n . |

|---|---|---|

| Any disconnection practice | 39.5 | 1,567 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media away | 23.4 | 928 |

| Put my mobile phone or other digital media with the screen facing down | 7.4 | 295 |

| Told myself not to look at my mobile phone or other digital media | 4.7 | 187 |

| Told myself not to look on certain websites or apps (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.3 | 53 |

| Closed programs, apps and websites (e.g., email, news, social media) | 1.5 | 59 |

| Turned off notifications (e.g., from email, news, and social media) | 2.7 | 108 |

| Turned off the internet (e.g., flight mode, “do-not-disturb” function) | 1.9 | 76 |

| Took a break from digital media in another way | 3.0 | 118 |

| Limited digital media use without any special approach | 7.6 | 303 |

| I have NOT taken a break from digital media in the past 2 hr | 60.5 | 2,405 |

Note: Data from 105 participants with 3,972 valid responses to the question about disconnection.

Next, we looked into the role of sociodemographics and digital skills in disconnection behavior, and the social context of disconnecting (Table 2). Mixed-effects logistic regression analysis revealed that gender, age, and education level did not relate to disconnection behavior over the course of one week. Digital skills (RQ1) were also not related to people’s engagement in disconnection practices throughout the day. When looking into the social context in which people disconnected, we found significant age and gender patterns. Specifically, older age was related to greater odds of disconnecting around one’s partner. We found no significant relationships between sociodemographics and disconnecting around children. On the other hand, older age was related to lower odds of disconnecting around other family members (besides one’s partner and children), friends, and colleagues—suggesting that younger people are more likely to do so in these social contexts. Female participants also had lower odds of disconnecting while being with friends, as compared to male participants.

| . | Disconnection behavior (n = 3972) . | Social context: Alone (n = 1559) . | Social context: Partner (n = 1559) . | Social context: Child(ren) (n = 1559) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | OR . | [95% CI] . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . |

| Intercept | −0.07 | 0.93 | [0.21–4.19] | 0.84 | 2.32 | [0.78–6.88] | −4.94*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.05] | −7.30** | 0.00 | [0.00–0.06] |

| Female | −0.25 | 0.77 | [0.35–1.71] | −0.44 | 0.65 | [0.36–1.15] | 0.53 | 1.71 | [0.64–4.54 | 1.76 | 3.96 | [0.50–31.56] |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.96–1.02] | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.97–1.01] | 0.06*** | 1.07 | [1.03–1.10] | 0.04 | 1.04 | [0.96–1.13] |

| Higher educated | 0.19 | 1.21 | [0.59–2.50] | −0.13 | 0.87 | [0.52–1.48] | 0.41 | 1.51 | [0.64–3.57] | −0.14 | 0.87 | [0.13–5.91] |

| Digital skills (RQ1) | −0.19 | 0.83 | [0.52–1.33] | |||||||||

| ICC | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.84 | ||||||||

Social context: Other family (n = 1559) | Social context: Friend(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Colleague(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Other (n = 1559) | |||||||||

| B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | −1.02 | 0.36 | [0.05–2.38] | −0.18 | 0.84 | [0.20–3.47] | −0.68 | 0.51 | [0.06–4.40] | −5.18*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.07] |

| Female | 0.05 | 1.05 | [0.39–2.86] | −0.85* | 0.43 | [0.20–0.91] | 0.24 | 1.27 | [0.40–4.03] | 0.21 | 1.23 | [0.33–4.52] |

| Age | −0.07** | 0.94 | [0.90–0.98] | −0.06*** | 0.94 | [0.91–0.97] | −0.08** | 0.92 | [0.88–0.97] | 0.01 | 1.01 | [0.97–1.06] |

| Higher educated | −0.82 | 0.44 | [0.18–1.06] | 0.12 | 1.13 | [0.57–2.21] | −0.32 | 0.73 | [0.26–2.01] | 0.44 | 1.56 | [0.48–5.05] |

| ICC | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.58 | ||||||||

| . | Disconnection behavior (n = 3972) . | Social context: Alone (n = 1559) . | Social context: Partner (n = 1559) . | Social context: Child(ren) (n = 1559) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | OR . | [95% CI] . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . |

| Intercept | −0.07 | 0.93 | [0.21–4.19] | 0.84 | 2.32 | [0.78–6.88] | −4.94*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.05] | −7.30** | 0.00 | [0.00–0.06] |

| Female | −0.25 | 0.77 | [0.35–1.71] | −0.44 | 0.65 | [0.36–1.15] | 0.53 | 1.71 | [0.64–4.54 | 1.76 | 3.96 | [0.50–31.56] |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.96–1.02] | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.97–1.01] | 0.06*** | 1.07 | [1.03–1.10] | 0.04 | 1.04 | [0.96–1.13] |

| Higher educated | 0.19 | 1.21 | [0.59–2.50] | −0.13 | 0.87 | [0.52–1.48] | 0.41 | 1.51 | [0.64–3.57] | −0.14 | 0.87 | [0.13–5.91] |

| Digital skills (RQ1) | −0.19 | 0.83 | [0.52–1.33] | |||||||||

| ICC | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.84 | ||||||||

Social context: Other family (n = 1559) | Social context: Friend(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Colleague(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Other (n = 1559) | |||||||||

| B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | −1.02 | 0.36 | [0.05–2.38] | −0.18 | 0.84 | [0.20–3.47] | −0.68 | 0.51 | [0.06–4.40] | −5.18*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.07] |

| Female | 0.05 | 1.05 | [0.39–2.86] | −0.85* | 0.43 | [0.20–0.91] | 0.24 | 1.27 | [0.40–4.03] | 0.21 | 1.23 | [0.33–4.52] |

| Age | −0.07** | 0.94 | [0.90–0.98] | −0.06*** | 0.94 | [0.91–0.97] | −0.08** | 0.92 | [0.88–0.97] | 0.01 | 1.01 | [0.97–1.06] |

| Higher educated | −0.82 | 0.44 | [0.18–1.06] | 0.12 | 1.13 | [0.57–2.21] | −0.32 | 0.73 | [0.26–2.01] | 0.44 | 1.56 | [0.48–5.05] |

| ICC | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.58 | ||||||||

Notes: N = 105 participants. Analyses for the role of social context were done in a subsample of events in which people disconnected. B = unstandardized coefficient, OR = odds ratio; CI = OR confidence interval; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001.

| . | Disconnection behavior (n = 3972) . | Social context: Alone (n = 1559) . | Social context: Partner (n = 1559) . | Social context: Child(ren) (n = 1559) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | OR . | [95% CI] . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . |

| Intercept | −0.07 | 0.93 | [0.21–4.19] | 0.84 | 2.32 | [0.78–6.88] | −4.94*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.05] | −7.30** | 0.00 | [0.00–0.06] |

| Female | −0.25 | 0.77 | [0.35–1.71] | −0.44 | 0.65 | [0.36–1.15] | 0.53 | 1.71 | [0.64–4.54 | 1.76 | 3.96 | [0.50–31.56] |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.96–1.02] | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.97–1.01] | 0.06*** | 1.07 | [1.03–1.10] | 0.04 | 1.04 | [0.96–1.13] |

| Higher educated | 0.19 | 1.21 | [0.59–2.50] | −0.13 | 0.87 | [0.52–1.48] | 0.41 | 1.51 | [0.64–3.57] | −0.14 | 0.87 | [0.13–5.91] |

| Digital skills (RQ1) | −0.19 | 0.83 | [0.52–1.33] | |||||||||

| ICC | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.84 | ||||||||

Social context: Other family (n = 1559) | Social context: Friend(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Colleague(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Other (n = 1559) | |||||||||

| B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | −1.02 | 0.36 | [0.05–2.38] | −0.18 | 0.84 | [0.20–3.47] | −0.68 | 0.51 | [0.06–4.40] | −5.18*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.07] |

| Female | 0.05 | 1.05 | [0.39–2.86] | −0.85* | 0.43 | [0.20–0.91] | 0.24 | 1.27 | [0.40–4.03] | 0.21 | 1.23 | [0.33–4.52] |

| Age | −0.07** | 0.94 | [0.90–0.98] | −0.06*** | 0.94 | [0.91–0.97] | −0.08** | 0.92 | [0.88–0.97] | 0.01 | 1.01 | [0.97–1.06] |

| Higher educated | −0.82 | 0.44 | [0.18–1.06] | 0.12 | 1.13 | [0.57–2.21] | −0.32 | 0.73 | [0.26–2.01] | 0.44 | 1.56 | [0.48–5.05] |

| ICC | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.58 | ||||||||

| . | Disconnection behavior (n = 3972) . | Social context: Alone (n = 1559) . | Social context: Partner (n = 1559) . | Social context: Child(ren) (n = 1559) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | OR . | [95% CI] . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . | B . | OR . | 95% CI . |

| Intercept | −0.07 | 0.93 | [0.21–4.19] | 0.84 | 2.32 | [0.78–6.88] | −4.94*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.05] | −7.30** | 0.00 | [0.00–0.06] |

| Female | −0.25 | 0.77 | [0.35–1.71] | −0.44 | 0.65 | [0.36–1.15] | 0.53 | 1.71 | [0.64–4.54 | 1.76 | 3.96 | [0.50–31.56] |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.96–1.02] | −0.01 | 0.99 | [0.97–1.01] | 0.06*** | 1.07 | [1.03–1.10] | 0.04 | 1.04 | [0.96–1.13] |

| Higher educated | 0.19 | 1.21 | [0.59–2.50] | −0.13 | 0.87 | [0.52–1.48] | 0.41 | 1.51 | [0.64–3.57] | −0.14 | 0.87 | [0.13–5.91] |

| Digital skills (RQ1) | −0.19 | 0.83 | [0.52–1.33] | |||||||||

| ICC | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.84 | ||||||||

Social context: Other family (n = 1559) | Social context: Friend(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Colleague(s) (n = 1559) | Social context: Other (n = 1559) | |||||||||

| B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | B | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | −1.02 | 0.36 | [0.05–2.38] | −0.18 | 0.84 | [0.20–3.47] | −0.68 | 0.51 | [0.06–4.40] | −5.18*** | 0.01 | [0.00–0.07] |

| Female | 0.05 | 1.05 | [0.39–2.86] | −0.85* | 0.43 | [0.20–0.91] | 0.24 | 1.27 | [0.40–4.03] | 0.21 | 1.23 | [0.33–4.52] |

| Age | −0.07** | 0.94 | [0.90–0.98] | −0.06*** | 0.94 | [0.91–0.97] | −0.08** | 0.92 | [0.88–0.97] | 0.01 | 1.01 | [0.97–1.06] |

| Higher educated | −0.82 | 0.44 | [0.18–1.06] | 0.12 | 1.13 | [0.57–2.21] | −0.32 | 0.73 | [0.26–2.01] | 0.44 | 1.56 | [0.48–5.05] |

| ICC | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.58 | ||||||||

Notes: N = 105 participants. Analyses for the role of social context were done in a subsample of events in which people disconnected. B = unstandardized coefficient, OR = odds ratio; CI = OR confidence interval; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001.

Disconnection practices and subjective well-being (H1–H3)

The results of the multilevel linear regression models examining the relationship between disconnection and well-being are detailed in Tables 3–5. We first estimated intercept-only models, where we find intra-class correlations (ICC) of r = 0.39 for affective well-being, r = 0.48 for life satisfaction, and r = 0.41 for social connectedness. In general, the larger the ICC, the lower the variability within a person (and thus momentary assessments become irrelevant), and the higher the variability between the persons. In this case, our ICCs mean that over half of the variability in the outcome variables is due to momentary fluctuations within persons. As such, by using multilevel models, we can better model the variation in the outcome variables by allowing for individual differences in comparison to a model that does not take into account the multilevel structure of the data. Next, we included disconnection behavior as a predictor in the models to test the hypotheses (Tables 3–5, Model 1). Here, we found no significant effects of disconnection behavior on affective well-being, life satisfaction, or social connectedness. Thus, when a participant disconnected more or less often than they would do on average, this did not change their level of subjective well-being. As such, our hypotheses are rejected.

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H1) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | Β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.09*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.05 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.03] | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.29*** | 0.11 | [0.07–0.15] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.67 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.11 | 0.11 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.43 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H1) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | Β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.09*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.05 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.03] | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.29*** | 0.11 | [0.07–0.15] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.67 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.11 | 0.11 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.43 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

Note: B = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval; σ2 = variance, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

P < .01,

P < .001.

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H1) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | Β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.09*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.05 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.03] | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.29*** | 0.11 | [0.07–0.15] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.67 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.11 | 0.11 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.43 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H1) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | Β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.14*** | 5.09*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.05 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | −0.27** | −0.16 | [−0.28, −0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.03] | 0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.29*** | 0.11 | [0.07–0.15] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.67 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.11 | 0.11 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.43 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

Note: B = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval; σ2 = variance, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

P < .01,

P < .001.

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H3) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 3.75*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | −0.08 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.00] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.28 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | −0.028 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.10 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.92*** | 0.25 | [0.21–0.29] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.91 | 1.91 | 1.69 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.32 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.34 | 0.34 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H3) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 3.75*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | −0.08 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.00] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.28 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | −0.028 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.10 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.92*** | 0.25 | [0.21–0.29] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.91 | 1.91 | 1.69 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.32 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.34 | 0.34 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

Note. B = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval; σ2 = variance, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

P < .001.

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H3) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 3.75*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | −0.08 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.00] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.28 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | −0.028 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.10 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.92*** | 0.25 | [0.21–0.29] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.91 | 1.91 | 1.69 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.32 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.34 | 0.34 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H3) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 4.05*** | 3.75*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | −0.08 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.00] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.09 | −0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] | |||

| Digital skills | −0.28 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | −0.028 | −0.12 | [−0.24, 0.00] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | 0.10 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 0.92*** | 0.25 | [0.21–0.29] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.91 | 1.91 | 1.69 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.32 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.34 | 0.34 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

Note. B = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval; σ2 = variance, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

P < .001.

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H2) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 72.07*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 71.76*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.31 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.26 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.22 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | 0.18 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | |||

| Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | 0.04 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | −0.67 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.02] | −0.62 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.03] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 4.83* | 0.14 | [0.02–0.25] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 161.18 | 161.07 | 157.77 | 157.77 | 150.75 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 149.83 | 151.53 | 149.64 | 149.64 | 109.39 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 2.76 | 2.76 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.42 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H2) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 72.07*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 71.76*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.31 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.26 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.22 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | 0.18 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | |||

| Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | 0.04 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | −0.67 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.02] | −0.62 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.03] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 4.83* | 0.14 | [0.02–0.25] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 161.18 | 161.07 | 157.77 | 157.77 | 150.75 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 149.83 | 151.53 | 149.64 | 149.64 | 109.39 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 2.76 | 2.76 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.42 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

Note: B = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval; σ2 = variance, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

p < .05,

p < .001.

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H2) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 72.07*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 71.76*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.31 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.26 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.22 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | 0.18 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | |||

| Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | 0.04 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | −0.67 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.02] | −0.62 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.03] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 4.83* | 0.14 | [0.02–0.25] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 161.18 | 161.07 | 157.77 | 157.77 | 150.75 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 149.83 | 151.53 | 149.64 | 149.64 | 109.39 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 2.76 | 2.76 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.42 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

| . | Model 1: Fixed effects (H2) . | Model 2: Fixed effects with interaction (RQ2) . | Model 3: Random effects (Exploratory) . | Model 4: Random effects with interaction (Exploratory) . | Model 5: Fixed effects (Exploratory) . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . | B . | β . | 95% CI . |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 72.07*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 72.08*** | 71.76*** | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 0.31 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.26 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.22 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | 0.18 | 0.01 | [−0.05, 0.07] | |||

| Digital skills | 0.03 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | 0.04 | 0.00 | [−0.14, 0.15] | |||||||||

| Disconnection × Digital skills | −0.67 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.02] | −0.62 | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.03] | |||||||||

| Disconnection with copresent others | 4.83* | 0.14 | [0.02–0.25] | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | σ2 | ||||||||||

| Residual | 161.18 | 161.07 | 157.77 | 157.77 | 150.75 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 149.83 | 151.53 | 149.64 | 149.64 | 109.39 | ||||||||||

| Disconnection | 2.76 | 2.76 | |||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.42 | ||||||||||

| Observations | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 3,972 | 1,559 | ||||||||||

| N | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 100 | ||||||||||

Note: B = unstandardized coefficient, β = standardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval; σ2 = variance, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

p < .05,

p < .001.

Additionally, we ran exploratory models with disconnection as a dichotomous variable (i.e., in its uncentered form). This allowed us to test whether a situation in which someone disconnected (yes/no)—rather than whether someone disconnected more on less than they normally would have—led to a change in their well-being. Here, we also find no significant effects of disconnection behavior on well-being outcomes. Finally, we also explored the possibility that there could be lagged effects of disconnection at one time point, and subjective well-being at the next time point (only for affective well-being and social connectedness, as life satisfaction was only assessed at the end of the day). These results also did not yield additional insights.

Individual differences in the disconnection—subjective-well-being relationship (exploratory analyses)

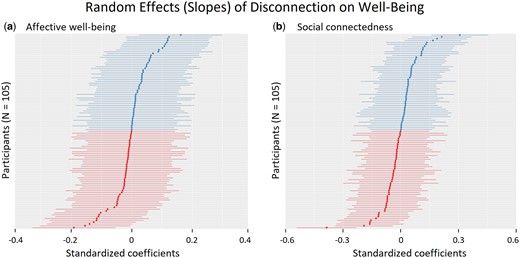

Inspired by previous work in the domain of social media use and well-being (Valkenburg et al., 2021), we conducted exploratory analyses in which we accounted for random slopes to examine whether there are between-person differences in the within-person relationship on disconnection practices and subjective well-being. Extending the models for H1–H3 with random slopes (Tables 3–5, Model 3) significantly improved the model fit for predictions of affective well-being (X2 (2) = 17.97, P < .001) and social connectedness (X2 (2) = 44.91, P < .001), but not for life satisfaction (X2 (2) = 2.84, P = .242). Figure 1 displays the random effects for the relationship between disconnection and (a) affective well-being and (b) social connectedness. For the relationship between disconnection and affective well-being (Figure 1a), β ranged from –.18 (negative) through .18 (positive), with 11 participants (10.5%) experiencing effects of β = –.05 and lower, 73 people (69.5%) between β = –.05 and .05, and 21 participants (20.0%) of β = .05 and higher. For the relationship between disconnection and social connectedness (Figure 1b) β ranged from –0.40 (negative) through 0.29 (positive), with 32 participants (30.5%) experiencing effects of β = –.05 and lower, 57 people (54.3%) between β = –0.05 and .05, and 16 participants (15.2%) of β = .05 and higher. Although the effects are small, our analyses reveal that the within-person relationship between disconnection and affective well-being, as well as disconnection and social connectedness, differs across people.

Random effects (slopes) of disconnection practices on subjective well-being. (a) Affective well-being. (b) Social connectedness.

The moderating role of digital skills (RQ2)

To examine the possible moderating effect of digital skills on the relationship between disconnection and subjective well-being, we added a cross-level interaction term to the fixed-effects regression models (Tables 3–5, Model 2). We found no significant moderation effects, meaning that the within-person relationship between disconnection and subjective well-being did not vary depending on people’s level of digital skills. As exploratory analyses (Tables 3–5, Model 4), we also ran models with cross-level interaction effects between disconnection and digital skills to examine if the varying slopes in the random-effects model (i.e., differences in effects of disconnection on well-being across people) could be explained by their different levels of digital skills. These analyses did not yield additional insights.

The role of social context of disconnection (exploratory analyses)

Finally, we also explored the role of the social context in which people are disconnecting (Tables 3–5, Model 5). One reason for disconnection might be the copresence of others and therefore an immediate desire to disconnect from technology. For these analyses, we focused on the subset of observations in which disconnection took place and used a dichotomous variable reflecting the physical copresence of others during a disconnection attempt (1 versus 0 being alone; see “Daily ESM Questionnaires” in the Methods section). Similar to H1–H3, we ran multilevel linear regression models examining the relationship between disconnection in the physical copresence of others (predictor) and subjective well-being (outcome). The analyses revealed significant main effects indicating that when people disconnected while around others, their affective well-being, social connectedness, and life satisfaction momentarily improved.

Discussion and conclusion

This preregistered study aimed to examine the effects of everyday disconnection practices on people’s affective, cognitive, and social well-being, as well as the role of digital skills in this relationship. By employing mobile ESM, we were able to capture people’s nuanced disconnection practices throughout the day (e.g., putting the phone away or with the screen down; deciding not to use certain apps or websites), as well as give insight into the momentary, short-lived effects of such deliberate non-use on subjective well-being. By applying this methodological approach to addressing this relationship, our work offers a refined and nuanced perspective on the implications, or lack thereof, of deliberate non-use of technology in a digital world. With our work, we contribute to the currently small, but rapidly growing, body of literature on digital disconnection and well-being.