-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Brian E Weeks, Audrey Halversen, German Neubaum, Too scared to share? Fear of social sanctions for political expression on social media, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 29, Issue 1, January 2024, zmad041, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad041

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

While social media provide opportunities for political expression, many people may be reluctant to share their opinions if they fear personal or professional repercussions for posting political views. Fear of social sanctions (FOSSs) therefore represents a promising approach to investigate why people often avoid expressing political opinions online. Using panel survey data collected during the 2020 U.S. election, this study examines the predictors of FOSSs, as well as its relationship with several forms of online political expression. Results indicate that the ideological diversity of people’s online networks fosters their FOSSs, which in turn is associated with decreases in several types of online political expression. Thus, FOSSs may be an important determinant in individuals’ calculations to express political opinions online and may also hinder lower commitment forms of political engagement.

Lay Summary

Social media allow people to publicly express their political views, but many say they do not take advantage of this opportunity because they are afraid that sharing their political opinions online could lead to negative consequences in their personal or professional lives, such as damaging their relationships with friends and family or jeopardizing their job. This study has two goals. First, we examine whether characteristics of people’s social media environments impact their fears about sharing their political views online. Second, we test whether fears about the social and professional consequences of sharing political views online actually make it less likely that people express their political opinions on social media. We find that people who have more politically diverse social media environments are more fearful of sharing their political views online. We also find that people who are more afraid of the social and professional consequences of sharing their political views on social media often engage in self-censorship, becoming less likely to share news or their political opinions online, including liking or commenting on political posts made by others. This suggests that fears about the negative consequences of sharing political views on social media can limit political expression online.

Social media have created myriad opportunities for citizens to express their political views online. While this expression can at times encourage anti-democratic outcomes, such as spreading misinformation or facilitating hate speech (e.g., Valenzuela et al., 2019), sharing one’s political views online can also have benefits, including strengthening users’ political self-concepts (Lane et al., 2019), mobilizing offline participation in politics (Yamamoto et al., 2015), and advancing social causes (Jackson et al., 2020). Yet, many social media users are disinclined to express their political opinions online (Shen & Liang, 2015). While there may be a number of reasons why users choose not to engage politically online, one prominent explanation stems from spiral of silence theory. The theory argues that individuals fear and want to avoid social isolation and therefore monitor the opinion environment to assess the degree to which their views are shared by others (Hayes et al., 2011; Noelle-Neumann, 1974). Subsequently, those who perceive that their opinion aligns with the majority are more inclined to freely share their views, while those in the minority often self-censor (Scheufele et al., 2001; Glynn & Huge, 2013).

With the expansion of social media, spiral of silence theory has often been used to explain when and why users express themselves online (or not) (see Neubaum & Weeks, 2023). While this research illustrates some factors that promote or inhibit online political expression, we argue that extant work concerning online spirals of silence is limited in two important ways. First, although research into offline opinion expressions has often utilized survey data (see Glynn & Huge, 2013), the body of work examining silencing and online expressions has typically utilized experiment-based studies that measure behavioral intentions or participants’ willingness to self-censor. While these approaches have helped establish causal arguments related to online spirals of silence, they are limited in that they often do not examine how characteristics of participants’ own online social networks (e.g., network size and diversity) relate to their actual expression behaviors on these networks (cf Kwon et al., 2015).

Second, online spiral of silence research is often limited in the measurement of fear of isolation (FOI). A central tenet of spiral of silence suggests that people fear social isolation, leading minority opinion holders to self-censor to avoid expected social sanctions imposed by the majority (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). To assess this claim, most research has measured trait-based constructs that capture dispositional fear of being socially excluded, such as FOI or fear of social isolation (FSI) (Hayes et al., 2011; Scheufele et al., 2001). Though important, this approach fails to capture individuals’ situational FOI, or the degree to which people fear social sanctions in specific communication contexts or environments. This limitation is especially important in the contemporary media landscape, where online political expression may be influenced by a number of situational factors, such as maintaining professional and personal relationships or avoiding public online shaming.

This study addresses these gaps in a few ways. We argue that spiral of silence research must also examine how situational—rather than just dispositional—fears of social consequences are associated with political expression in contemporary online environments. To test this, we use survey data of Facebook users in the USA to examine how characteristics of their real-world online social networks are related to fears of social sanctions and whether those fears subsequently inhibit several types of political expression on the platform (political opinion expression, news sharing, liking, and commenting on political posts).

The spiral of silence in computer-mediated communication

One main premise of spiral of silence theory states that the perception of a disagreeable opinion climate inhibits opinion expression (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). In the context of social media, political expression is defined as actions that allow people to communicate their political preferences, attitudes, and opinions to others, including both higher-commitment behaviors (e.g., posting a political view) and lower-commitment behaviors (e.g., liking political content) (Lane et al., 2019; Vaccari et al., 2015). Much like in offline contexts, perceiving a hostile opinion climate reduces online expression behaviors (Gearhart & Zhang, 2015; Matthes et al., 2018), while imagining or perceiving an audience that aligns with the majority encourages speaking out (Chun & Lee, 2022; Soffer & Gordoni, 2018; Wang et al., 2017; Yun et al., 2020).

However, there are some boundary conditions to the spiral of silence (Matthes et al., 2010; Noelle-Neumann, 1974). For instance, when individuals have strong political opinions, identify as strong partisans, or perceive a political issue as highly important (those Noelle-Neumann termed the “hard-core”), they are less likely to silence themselves in the face of a counter-attitudinal climate, and this holds true in online contexts (Duncan et al., 2020; Gearhart & Zhang, 2014; Kim, 2016; Wang et al., 2017). This phenomenon may owe itself in part to ego involvement (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005); when an issue is important enough to constitute a part of someone’s identity, they may be willing to express their views in a dissenting environment. Some studies have also failed to find evidence that online opinion climates impact political expression (Kwon et al., 2015; Liu & Fahmy, 2011). For instance, some individuals with minority views about race were comfortable expressing unpopular opinions on Facebook (Chaudhry & Gruzd, 2019).1 Despite these caveats, a recent meta-analysis (Matthes et al., 2018) found that opinion climate and opinion expression (as the key correlates of the silencing hypothesis) were strongly related.

Traditional spiral of silence research often relies on either topical opinion climates about particular political issues (e.g., “I agree with most Americans on the issue of gun laws”) or the general distribution of political ideologies in a social environment as the correlate of individuals’ willingness to express themselves. Yet, changes in the media environment may require different approaches to the conceptualization of opinion climates. Because people can more easily curate their own online environment, their perceptions of the opinion climate may be influenced by the diversity of information and people they surround themselves with on social media (see Tsfati et al., 2014). We therefore focus on the construct of “perceived ideological network diversity” as a measure of the opinion climate, which reflects the extent to which an individual perceives that their online social network as a whole holds political ideologies that diverge from their own.

The ideological diversity of one’s social media networks can have implications for political expression. More ideologically or politically diverse networks can lead individuals to encounter more disagreement and conflict (Lu & Myrick, 2016; Neubaum et al., 2021), which may increase their fear of facing moral and social condemnation for speaking out. In other words, if someone exists in a more diverse online network, they may be aware that there are many people with whom they disagree, perceive a more hostile opinion climate, and ultimately be more hesitant to speak publicly. This is especially true on non-anonymous platforms like Facebook, where users interact with friends, coworkers, acquaintances, relatives, and others who hold the power to enact social or professional sanctions against the user for expressing (unpopular) political views. In this way, diverse networks online can be perceived as risky for political speech (Barnidge et al., 2018; Neubaum & Weeks, 2023). Empirical evidence supports this as well; greater network diversity online is associated with lower intentions to engage in some expressive political behaviors, such as posting political content or liking a political candidate’s social media page (Barnidge et al., 2018; Marder, 2018).

Based on these arguments, we expect that network diversity will be negatively related to political expression on social media generally. But social media affordances open up a variety of ways to express one’s political views, and it is important to also look individually at both high and low commitment forms of engagement. Two active types of political expression that require more effort and commitment on the part of social media users include news sharing and opinion expression (Vaccari et al., 2015). News sharing, which consists of posting news articles on social media, requires higher commitment because individuals often reframe or repurpose the news content for others (Choi, 2016). Opinion expression is a high commitment form of engagement because it requires cognitive effort to compose and post a message relaying one’s beliefs or views (Kim et al., 2021). Taken together, we expect that individuals who perceive their own online network to be ideologically diverse (and therefore include more dissidents) will be less likely to engage in expressive actions, including high commitment behaviors.

H1: Perceived ideological network diversity will be negatively associated with political expression (H1) on Facebook, including news sharing (H1a) and opinion expression (H1b).

While some silencing studies have assessed political news and opinion sharing behaviors, fewer have investigated participants’ willingness to speak out online through a broader range of behaviors, such as liking or commenting on political posts. This point is crucial, as recent work has found that these different forms of online political expression have distinct impacts for outcomes such as political knowledge (Kim et al., 2021). In the context of spiral of silence research, it is especially important to analyze these behaviors, as they are typically less public and require less commitment than making original posts about politics. If spiral of silence processes emerge even for behaviors such as liking political posts, this indicates broad applicability of the theory in online networks; if not, it may illustrate an important boundary condition. Thus, it is important to expand the outcomes assessed in spiral of silence research to include liking and commenting on posts. There is some evidence suggesting that these behaviors may similarly be inhibited by ideologically threatening networks (Kushin et al., 2019; Lee & Chun, 2016; Marder, 2018). However, because these studies measured expression intentions, it is not entirely clear whether actual commenting and liking expressions relate to network diversity. Therefore, we investigate the following research question:

RQ1: Is perceived ideological network diversity associated with commenting on (RQ1a) and liking (RQ1b) political posts on Facebook?

Rethinking FOI in computer-mediated spirals of silence

In the extant spiral of silence literature, FOI has traditionally served as a primary explanation for why minority opinion holders are less willing to speak about politics. Methodologically, studies have typically employed one of two scales, including the FSI scale (Hayes et al., 2011) (e.g., “It would bother me if no one wanted to be around me”; “I dislike feeling left out of social functions, parties, or other social gatherings”) as well as variations of the generalized FOI scale (Scheufele et al., 2001) (e.g., “I worry about being isolated if people disagree with me; I try to avoid getting into arguments”). As the statements indicate, these scales assess individuals’ dispositional attitudes toward being socially excluded.

Conversely, some scholars have conceptualized FOI as a situational variable related to communication apprehension (e.g., Fox & Holt, 2018; Neuwirth et al., 2007), though these studies are few in number. Neubaum and Krämer (2018)—drawing on Roessler and Schulz’ (2014) work on expected sanctions—argued that people may expect different social sanctions based on the conversational context, for example online versus offline situations. In other words, FOI “manifests in accordance with the social situation” (p. 145). Even within the context of online communication, there are specific situations that may increase the likelihood of silencing. The expected costs of political expression may vary alongside the affordances offered by particular social media platforms (Neubaum & Weeks, 2023). For example, more public and/or non-anonymous (i.e., more visible and identifiable) social media platforms may be particularly ripe for silencing, as people may be less able to control who sees their posted messages or have networks that include diverse audiences or multiple social groups (e.g., friends, family, acquaintances, and co-workers). In such cases, people may perceive these spaces as especially threatening because of the networks’ potential to impose social sanctions (in comparison to offline or more anonymous online spaces) and feel less equipped to deal with expected sanctions when communicating online (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018). Thus, the affordances that some social media platforms offer (e.g., visibility, persistence, and identifiability) may create situational fears of social sanctions that are not captured by trait- or dispositional-based constructs like FSI or FOI. We argue that in the contemporary media environment, whether individuals choose to express themselves politically online may depend on fears directly connected to their expectations of social sanctions in a social media context.

Research into the specific fears social media users have about political expression online helps form the basis for how we conceptualize fear of social sanctions (FOSSs) as a variable of interest in this study. Using semi-structured interviews and data from an experiment, Neubaum and Krämer (2018) identified three expected social sanctions people anticipated when deciding whether to express a minority opinion online, including fear of being judged, fear of rejection, and fear of being personally attacked. Another study similarly found that Facebook users feared being publicly shamed for merely expressing a political opinion (Vraga et al., 2015). In addition, social media users may fear professional repercussions such as damage to professional relationships if they state minority views online, especially if their networks are composed of multiple social groups (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, 2018; Fox & Holt, 2018; Gil-Lopez et al., 2018). Based on these contemporary realities, we argue that the concept of FOSSs will better grasp context-specific fears social media users face when considering whether to express themselves online and help explain the silencing processes on social media.

That said, little work has examined how opinion climates relate to situational fears of social sanctions, but prior work on dispositional FOI does offer some important insights for our approach. Past work indicates that individuals who perceive an opinion climate to be more supportive of their views express lower FOI (Kushin et al., 2019; Schulz & Roessler, 2012). Moreover, when individuals perceive social support in the form of online opinion congruency, they may feel empowered (Chun & Lee, 2017; Yun et al., 2020), and thus their FOI may be diluted. Such findings are consistent with Noelle-Neumann’s (1974) original theoretical logic, which proposed that ideologically diverse environments trigger social fears about whether people would be punished for expressing their views. Based on this evidence and logic, we posit that:

H2: Perceived ideological network diversity will be positively associated with FOSSs.

In addition to network diversity, there are reasons to suspect that network size may relate to FOSSs among social media users (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). A larger network may heighten users’ perceptions of social surveillance, causing them to self-censor. Further, a large network may result in a context collapse (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, 2018; Gil-Lopez et al., 2018), in which users attempt to appease followers from multiple social groups (e.g., coworkers, acquaintances, family, and friends); as a result, these users may be more likely to fear repercussions if they become politically active online. For example, Das and Kramer (2013) showed that Facebook users with more expansive online social networks were more likely to censor their posts. It is possible that these larger networks are more difficult for users to control or include a greater number of less trusted contacts. Thus, there is some evidence supporting the idea that larger networks may be associated with greater FOSSs, leading us to predict that:

H3: Network size will be positively associated with FOSSs.

FOSSs and online expression

We argue here that FOSSs may represent an explanatory link between characteristics of one’s online network (diversity and size) and their willingness to express political views online. When people fear negative social consequences for political expression, they are simply less likely to engage in it. Such fears may be particularly likely to inhibit political expression in online contexts. For instance, people with greater dispositional fears of social isolation were less willing to speak out or engage politically online (Hoffman & Lutz, 2017; Shim & Oh, 2018). Fears about political expression on social media may be heightened by the specific affordances of the platforms. People appear to be especially concerned about the persistence of political messages posted to social media, or the idea that messages may exist and be seen long after they were originally posted. Such persistence of messages can lead to self-censorship of political speech online (Fox & Holt, 2018; Neubaum, 2022). Other affordances like message visibility, editability, and the (lack of) anonymity on some social media platforms all contribute to whether or not people express themselves on social media, and people are less likely to share their views when the potential negative costs of that expression are high (Neubaum & Weeks, 2023). Based on these findings, as well as Noelle-Neumann’s (1974) original assertion that minority views are silenced, in part, due to expected social sanctions imposed by the majority, we predict that:

H4: FOSSs will be negatively associated with political expression on Facebook (H4), including news sharing (H4a) and opinion expression (H4b).

Because research into political liking and commenting behaviors is sparse and limited to assessing intentions to engage in expressive behaviors (Kushin et al., 2019; Lee & Chun, 2016; Marder, 2018), it is unclear whether FOSSs will relate to low-commitment expression. Therefore, we investigate the following research question:

RQ2: Is FOSSs associated with commenting on (RQ2a) and liking (RQ2b) political posts on Facebook?

Do FOSSs and political expression vary by political party affiliation?

In the particular context of the USA, there are also important questions of whether fears of social sanctions and their potential consequences vary by political party. Interview studies suggest that both Democrats and Republicans are concerned that sharing political views with others could damage their relationships or take an emotional toll on their personal or professional lives, suggesting there may not be partisan differences in FOSSs (Masullo & Duchovnay, 2022). That said, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say that people who are called out for posting potentially offensive content on social media are unfairly punished (Pew Research Center, 2021a, 2021b). There is mixed evidence, however, as to whether political expression is dependent on party affiliation or ideology. For example, Van Duyn (2018) found that some Democratic women in more conservative rural communities in Texas were reluctant to express their political views publicly because they feared social repercussions. Similarly, conservatives in academia are more likely to fear professional repercussions for voicing their political opinions than are their liberal counterparts (Norris, 2023). These cases reflect specific instances in which people who identify with one political party or ideology are in the overwhelming minority in their social or professional group. Other work that looks at political discussion more broadly indicates that conservatives and liberals do not differ in the extent to which they express political views in heterogeneous discussion groups (Peacock, 2021). Based on these findings, we do not have strong predictions about the relationships between political party affiliation, FOSSs, and political expression. We therefore ask two final research questions:

RQ3: To what extent do FOSSs vary across political party affiliation?

RQ4: Does political party affiliation moderate the relationships between FOSSs and political expression on Facebook?

Method

To assess the hypotheses and research questions, we designed a series of questions that were fielded as part of an original two-wave survey using a sample we contracted from the research company YouGov. The first wave of data collection was fielded prior to the 2020 U.S. general election in late September and early October of 2020, while W2 was collected immediately following the election (4–11 November 2020). While not a probability-based sample, the sample closely resembles the U.S. population on age, race, gender, and education due to the sample matching methodology employed by YouGov. Full details concerning the sampling methodology and demographics are provided in the Supplementary Materials. In total, 5,382 individuals were invited to take part in the survey; 2,153 participants completed the survey for a completion rate of roughly 40%. 353 respondents who completed the study were removed from the sample by YouGov in order to meet quota sampling requirements and ensure a reasonably representative sample of the U.S. adult population. This resulted in a final sample size of 1,800 participants in W1. 1,265 respondents returned to complete W2 (70.28% retention rate).

Because our study examines FOSSs and political expression on social media, it is necessary for us to limit our analyses to social media users. In this case, we opt to examine study respondents who are Facebook users. While Facebook is not generalizable to all social media platforms, it remains by far the most used social networking site in the USA, and its users are more demographically and politically diverse than other platforms like Twitter or Instagram (Pew Research Center, 2021a, 2021b). It therefore serves as a reasonable platform to test our hypotheses and research questions. All descriptives and analyses below are limited to respondents who self-reported using Facebook in the 14 days prior to beginning the study (W1 N = 1291, 71.7% of full sample; W2 N = 860, 66.6% of W2 sample).

Demographics suggest the analyzed sample of Facebook users was reasonably reflective of the adult population in the USA; 59.2% were women, the mean age was 50.32 (SD = 16.31), and the median level of education was “some college.” The sample also resembled the racial (75.9% White, 8.8% Black, 8.6% Hispanic, 2.2% Asian, 0.8% Native American, and 1.6% identified as a non-listed race) and political (36.7% Democrat, 28.1% Republican, and 27.1% Independent) demographics in the USA.

Measures

Perceived ideological network diversity

Perceived ideological network diversity was measured as the degree to which respondents’ political views were aligned with their perception of the dominant political positioning of their connections on social media. Specifically, respondents were asked to think about their online social networks and consider which presidential candidate their friends or other people they follow supported. Response options were “all or almost all support Donald Trump,” “most support Donald Trump,” “about half support Donald Trump and half support Joe Biden,” “most support Joe Biden,” and “all or almost all support Joe Biden.” We compared these responses to participants’ self-reported political party identification. Those whose social networks mostly or completely supported the presidential candidate from their own political party were coded as belonging to congruent networks (n = 606, 51.1%, coded as 1). Those whose social networks mostly or completely supported the presidential candidate from the opposing party were coded as belonging to non-congruent networks (n = 51, 4.3%, coded as 3). All other participants were coded as belonging to mixed networks (n = 529, 44.6%, coded as 2). Higher values on the resulting three-point variable reflect more diverse networks (M = 1.53, SD = 0.58).

Network size

Network size was measured as the number of friends or connections participants had on social media in general. Participants were asked to estimate how many social media connections they have. The resulting variable was skewed (M = 502.12, SD = 997.12, skewness = 4.33). Thus, we used the natural logarithm to bring the distribution closer to the normal curve, reducing the skewness (M = 5.11, SD = 1.63, skewness = −0.46). Six individuals who reported more than 10,000 friends were removed from the data set as outliers.

FOSSs

The FOSSs construct was measured as the degree to which respondents feared they would face social or professional consequences if they expressed their political views online. Based on prior work (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018) demonstrating that individuals fear the social sanctions of being judged, rejected, and personally attacked, this variable included the following four items: (a) “I am afraid others will judge me if I express my true political opinions online”; (b) “I am afraid of the social consequences if I say something controversial online”; (c) “I am afraid of being excluded by people I know if I express my true political opinions online”; and (d) “I am afraid about being publicly shamed or attacked for saying the wrong thing online.” Further, because previous work has suggested that social media users consider the diversity of their network when determining what to post (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, 2018; Gil-Lopez et al., 2018), another item was added to the scale, which was (e) “I am afraid I will damage my professional or social relationships if I express my true political opinions online.” Each item was assessed on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Items were averaged (M = 3.62, SD = 1.68) and the resulting 5-item scale was highly reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = .917). Further, these items were subject to a confirmatory factor analysis whose model fit was good, confirming the factor validity: χ2 (5) = 30.59, p < .001, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.06 (90% confidence interval from 0.05 to 0.08), SRMR = 0.02).

Political expression on Facebook

The study assessed four variables related to political expression on Facebook, including news sharing, political opinion expression, commenting on, and liking political posts. While these measures rely on self-reports, research suggests that self-reported political expression on social media is positively correlated with actual expression behavior on these platforms (Guess et al., 2019). The analyses in the results section report the predictors of expression in the second wave. For each variable, participants were asked to report the frequency with which they had performed these behaviors on Facebook in the past 14 days. Each item was assessed on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “never” (1) to “several times a day” (7). News sharing (W2: M = 2.44, SD = 1.79) was assessed with two items that asked respondents how often they had shared or posted “a link to a news story” and “a photo or video” about the 2020 presidential election or candidates, while political opinion expression (W2 M = 2.63, SD = 1.97) was assessed by asking how often respondents had “shared or posted your own opinions about the 2020 presidential election or candidates.” Commenting on political posts (W2 M = 2.88, SD = 1.98) was measured using the item “how often have you commented on news or information about the 2020 presidential election or candidates that was posted by someone else,” and liking political posts (W2 M = 3.61, SD = 2.17) was measured using the item “how often have you ‘liked’ a post or story about the 2020 presidential election or candidates that was posted by someone else.” While regression analyses assess the four measures of expression individually, we also created a composite measure that reflects the average of the four (W2 M = 2.89, SD = 1.75, α = .90). To further test the factor validity of these items in Wave 2, we ran an CFA which yielded a good model fit: χ2 (2) = 14.01, p = .001, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.08 (90% confidence interval from 0.05 to 0.12), SRMR = 0.02.

Control variables

Participants reported several demographics, including age, gender, race, education level, and political party affiliation. Respondents also reported their political interest, composed of two items measured on a 7-point scale, which were averaged (M = 5.47, SD = 1.60). Further, respondents answered eight questions gauging their political knowledge, resulting in composite scores ranging from 0 to 8 (M = 5.06, SD = 1.99). Participants also reported their traditional news use (national and local television news), online news use, and level of general interpersonal trust (“Most people can be trusted”). These variables are included in all models reported below.

Results

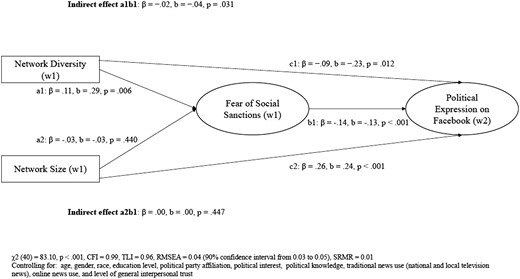

To test our hypotheses and research questions below, we use a combination of structural equation modeling (SEM) and ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions. The SEM tests a theoretical model in which network diversity and size predict FOSSs, as well as the associations of those three variables with political expression on Facebook (see Figure 1 for model). The expression variable in the SEM is a latent variable consisting of the four individual expression items in Wave 2. In the OLS regressions, we use each of the four expression behaviors in Wave 2 as separate outcomes. This approach allows us to test our theorized model of expression, while also examining how our variables of interest are associated with both high and low commitment expression. In the analyses reported below, all predictor variables were measured in Wave 1. All models include the control variables noted in the Methods section.

Our SEM used maximum likelihood estimation (using R, version 4.3.1, and the R packages lavaan, version 0.6.15 and semTools, version 0.5-6), and the overall fit of the model was strong, χ2 (40) = 83.10, p < .001, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% confidence interval from 0.03 to 0.05), SRMR = 0.01. We start by looking at the relationship between perceived ideological network diversity and political expression (H1). In support of H1, the SEM showed a negative relationship between network diversity and political expression on Facebook (as a latent factor including all four forms), β = −0.09, b = −0.23, SEb = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.40, −0.05], z = −2.52, p = .012.

We next use OLS regression to look at the relationships between network diversity and the four individual forms of expression (H1a-b, RQ1a-b). We find that network diversity is negatively related to opinion expression (b = −0.23 (.11), p = .04; supporting H1b), political commenting (b = −0.26 (0.11), p = .02), and political liking (b = −0.35 (0.12), p = .004). Network diversity was also found being a negative predictor of news sharing, though the association failed to reach standard benchmarks of (p < .05) of statistical significance; b = −0.18 (0.10), p = .08 (rejecting H1a). Taken together these results indicate that people in more diverse online networks are less likely to engage in both high and low commitment forms of political expression on social media.

As an exploratory analysis, in the SEM we examined the relationship between network size at Wave 1 and political expression on Facebook at Wave 2. Interestingly, this relationship was positive, β = 0.26, b = 0.24, SEb = 0.04, 95% CI [0.17–0.31], z = 6.76, p < .001, meaning that those with larger networks are more likely to express themselves.

We return to the SEM to examine whether network diversity and network size are predictive of FOSSs. Results indicate that network diversity (β = 0.11, b = 0.29, SEb = 0.11, 95% CI [0.09–0.50], z = 2.76, p = .006) was positively associated with FOSSs (supporting H2) but network size was not (β = −0.03, b = −0.03, SEb = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.05], z = −0.77, p = .440) (H3 not supported).

Keeping with the SEM, we next examine whether fears of social sanctions are associated with lower levels of political expression (H4). We find that they are; people with greater fears of social sanctions were less likely to express their political views on Facebook (β = −0.14, b = −0.13, SEb = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.20, −0.06], z = −3.59, p < .001).

Subsequent OLS regression models are consistent with the SEM, as FOSSs was negatively related to the different forms of expression. Individuals who fear social sanctions are less likely to share political news (b = −0.11 (0.04), p = .002; supporting H4a), express their opinion (b = −0.18 (0.04), p < .001; supporting H4b) and like political posts (b = −0.13 (0.04), p = .004; addressing RQ2b). There was also a negative relationship between FOSSs and commenting on political posts, but this relationship does not fall below the threshold for statistical significance (b = −0.07 (0.04), p = .07; addressing RQ2a).

To summarize the results thus far, the data show a strong and consistent pattern of negative associations between FOSSs and political expression on social media. In the integrative SEM and in all four OLS regression models, individuals with greater fear of being socially sanctioned for expressing their political views online are less likely to express those views on Facebook.2 These relationships hold when accounting for a number of alternative explanations, including the ideological diversity of one’s political network. This suggests that FOSSs may play a pivotal role in limiting political expression on social media.3

Although we do not formally hypothesize mediation, the nature of our proposed relationships suggests that respondents’ perceptions of the diversity of their online networks may have an indirect relationship with political expression through FOSSs. Theoretically, it is possible that perceived network diversity is associated with increased FOSSs, which is subsequently related to less political expression on social media. Indeed, the SEM indicated a significant, albeit weak, indirect relationship between network diversity and political expression through FOSSs (β = −0.02, b = −0.04, SEb = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.07, −0.00], z = −2.15, p = .031). However, we did not find an indirect relationship between network size and political expression through FOSSs (β = 0.00, b = 0.00, SEb = .01, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.02], z = 0.76, p = .447). The total effects were significant though for both network diversity (β = −0.11, b = −0.26, SEb = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.44, −0.09], z = −2.91, p = .004) and network size (β = −0.09, b = −0.22, SEb = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.40, −0.05], z = −2.47, p = .01). R2 was 0.03 for FOSSs and 0.10 for political expression on Facebook.

We also posed RQ3, asking whether political party identification was associated with FOSSs (see Table 1). Our data indicate that they are positively related, meaning that individuals who more strongly identify with the Republican party are more likely to fear social sanctions for political expression, b = 0.11 (0.02), p < .001.

| . | FOSSs (W1) . | News sharing (W2) . | Political opinion expression (W2) . | Commenting on political posts (W2) . | Liking political posts (W2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOSSs | — | −0.11 (0.04)** | −0.18 (0.04)*** | −0.07 (0.04)# | −0.13 (0.04)** |

| Perceived ideological network diversity | 0.33 (0.08)*** | −0.18 (0.10)# | −0.23 (0.11)* | −0.26 (0.11)* | −0.35 (0.12)** |

| Network size (log) | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.28 (0.04)*** | 0.32 (0.05)*** |

| Party affiliation (Rep. coded high) | 0.11 (0.02)*** | 0.05 (0.03)# | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.00 (0.03) |

| Age | −0.02 (0.00)*** | 0.01 (0.00)# | 0.01 (0.01)# | 0.02 (0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Gender (women coded high) | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.13)# | 0.20 (0.14) |

| Education | 0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.18 (0.05)*** | −0.16 (0.05)*** | −0.13 (0.05)* |

| Race (White coded high) | 0.17 (0.12) | −0.06 (0.15) | 0.12 (0.16) | 0.08 (0.16) | −0.00 (0.18) |

| Political interest | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.05)*** | 0.34 (0.04)*** | 0.38 (0.06)*** | 0.41 (0.06)*** |

| Political knowledge | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Traditional news use | 0.07 (0.03)* | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.05) |

| Online news use | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.08 (0.04)* |

| Interpersonal trust | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.05)# | −0.10 (0.05)* |

| Constant | 3.12 (0.38)*** | −0.05 (0.49) | 0.12 (0.53) | −0.95 (0.53)# | −1.14 (0.44)* |

| R2 (F) | 0.08 (8.19) | 0.16 (11.58) | 0.20 (14.74) | 0.21 (15.85) | 0.20 (14.75) |

| (df) | (12, 1166) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) |

| . | FOSSs (W1) . | News sharing (W2) . | Political opinion expression (W2) . | Commenting on political posts (W2) . | Liking political posts (W2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOSSs | — | −0.11 (0.04)** | −0.18 (0.04)*** | −0.07 (0.04)# | −0.13 (0.04)** |

| Perceived ideological network diversity | 0.33 (0.08)*** | −0.18 (0.10)# | −0.23 (0.11)* | −0.26 (0.11)* | −0.35 (0.12)** |

| Network size (log) | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.28 (0.04)*** | 0.32 (0.05)*** |

| Party affiliation (Rep. coded high) | 0.11 (0.02)*** | 0.05 (0.03)# | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.00 (0.03) |

| Age | −0.02 (0.00)*** | 0.01 (0.00)# | 0.01 (0.01)# | 0.02 (0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Gender (women coded high) | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.13)# | 0.20 (0.14) |

| Education | 0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.18 (0.05)*** | −0.16 (0.05)*** | −0.13 (0.05)* |

| Race (White coded high) | 0.17 (0.12) | −0.06 (0.15) | 0.12 (0.16) | 0.08 (0.16) | −0.00 (0.18) |

| Political interest | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.05)*** | 0.34 (0.04)*** | 0.38 (0.06)*** | 0.41 (0.06)*** |

| Political knowledge | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Traditional news use | 0.07 (0.03)* | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.05) |

| Online news use | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.08 (0.04)* |

| Interpersonal trust | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.05)# | −0.10 (0.05)* |

| Constant | 3.12 (0.38)*** | −0.05 (0.49) | 0.12 (0.53) | −0.95 (0.53)# | −1.14 (0.44)* |

| R2 (F) | 0.08 (8.19) | 0.16 (11.58) | 0.20 (14.74) | 0.21 (15.85) | 0.20 (14.75) |

| (df) | (12, 1166) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients reported. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 (all p values two-tailed). All independent variables measured in wave 1.

| . | FOSSs (W1) . | News sharing (W2) . | Political opinion expression (W2) . | Commenting on political posts (W2) . | Liking political posts (W2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOSSs | — | −0.11 (0.04)** | −0.18 (0.04)*** | −0.07 (0.04)# | −0.13 (0.04)** |

| Perceived ideological network diversity | 0.33 (0.08)*** | −0.18 (0.10)# | −0.23 (0.11)* | −0.26 (0.11)* | −0.35 (0.12)** |

| Network size (log) | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.28 (0.04)*** | 0.32 (0.05)*** |

| Party affiliation (Rep. coded high) | 0.11 (0.02)*** | 0.05 (0.03)# | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.00 (0.03) |

| Age | −0.02 (0.00)*** | 0.01 (0.00)# | 0.01 (0.01)# | 0.02 (0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Gender (women coded high) | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.13)# | 0.20 (0.14) |

| Education | 0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.18 (0.05)*** | −0.16 (0.05)*** | −0.13 (0.05)* |

| Race (White coded high) | 0.17 (0.12) | −0.06 (0.15) | 0.12 (0.16) | 0.08 (0.16) | −0.00 (0.18) |

| Political interest | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.05)*** | 0.34 (0.04)*** | 0.38 (0.06)*** | 0.41 (0.06)*** |

| Political knowledge | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Traditional news use | 0.07 (0.03)* | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.05) |

| Online news use | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.08 (0.04)* |

| Interpersonal trust | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.05)# | −0.10 (0.05)* |

| Constant | 3.12 (0.38)*** | −0.05 (0.49) | 0.12 (0.53) | −0.95 (0.53)# | −1.14 (0.44)* |

| R2 (F) | 0.08 (8.19) | 0.16 (11.58) | 0.20 (14.74) | 0.21 (15.85) | 0.20 (14.75) |

| (df) | (12, 1166) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) |

| . | FOSSs (W1) . | News sharing (W2) . | Political opinion expression (W2) . | Commenting on political posts (W2) . | Liking political posts (W2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOSSs | — | −0.11 (0.04)** | −0.18 (0.04)*** | −0.07 (0.04)# | −0.13 (0.04)** |

| Perceived ideological network diversity | 0.33 (0.08)*** | −0.18 (0.10)# | −0.23 (0.11)* | −0.26 (0.11)* | −0.35 (0.12)** |

| Network size (log) | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.28 (0.04)*** | 0.32 (0.05)*** |

| Party affiliation (Rep. coded high) | 0.11 (0.02)*** | 0.05 (0.03)# | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.00 (0.03) |

| Age | −0.02 (0.00)*** | 0.01 (0.00)# | 0.01 (0.01)# | 0.02 (0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Gender (women coded high) | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.13)# | 0.20 (0.14) |

| Education | 0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.18 (0.05)*** | −0.16 (0.05)*** | −0.13 (0.05)* |

| Race (White coded high) | 0.17 (0.12) | −0.06 (0.15) | 0.12 (0.16) | 0.08 (0.16) | −0.00 (0.18) |

| Political interest | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.05)*** | 0.34 (0.04)*** | 0.38 (0.06)*** | 0.41 (0.06)*** |

| Political knowledge | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Traditional news use | 0.07 (0.03)* | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.05) |

| Online news use | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.08 (0.04)* |

| Interpersonal trust | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.05)# | −0.10 (0.05)* |

| Constant | 3.12 (0.38)*** | −0.05 (0.49) | 0.12 (0.53) | −0.95 (0.53)# | −1.14 (0.44)* |

| R2 (F) | 0.08 (8.19) | 0.16 (11.58) | 0.20 (14.74) | 0.21 (15.85) | 0.20 (14.75) |

| (df) | (12, 1166) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) | (13, 778) |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients reported. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 (all p values two-tailed). All independent variables measured in wave 1.

Our final set of analyses address RQ4, which asked whether political party identification moderated the relationships between FOSSs and political expression. Were a relationship to emerge, it would suggest that the influence of FOSSs on political expression varies by political party. To test this potential moderation, we included an interaction between the FOSSs variable and political party identification in the OLS regression models (see Supplementary Table S2. Across the four types of political expression, we only find evidence that political party moderates the FOSSs-political expression relationship for news sharing (FOSSs × political party b = −0.04 (0.02), p = .02). A plot of the interaction (see Supplementary Figure S1) illustrates that Republicans are more likely than Democrats and Independents to share news when FOSSs is low. However, as FOSSs increase, Republicans become less willing to share news such that at high levels of FOSSs, there is no difference between Republicans and Democrats in news sharing. Democrats and Republicans do not differ in the degree to which FOSSs associates with the other three forms of political expression.

Discussion

This study addresses the question of whether characteristics of individuals’ online networks promote fears of social and professional consequences for political expression that subsequently diminish people’s willingness to share their political views on social media. We find that people who exist in more politically diverse online networks are less likely to engage in political expression on Facebook. At the same time, perceiving one’s network as ideologically diverse goes hand in hand with stronger fears of being socially sanctioned for political speech online. These fears of social sanctions, in turn, are also negatively associated with expressive behaviors. While these relationships were small in magnitude, the findings suggest that being embedded in a network with diverging political ideologies can create the perception of a threatening environment where sanctions for sharing disagreeable opinions are highly likely (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018; Vraga et al., 2015), and these fears appear to lead people to avoid participating in political conversations online.

Since the emergence of social media, important questions have centered around whether and how opinion silencing processes occur online. We find first that network diversity matters, as people in more politically diverse networks were more fearful of social sanctions for expressing political views online. While this result corroborates theoretical assumptions posited before (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018; Neubaum, 2022), to our knowledge this is one of the first studies to provide empirical evidence for such an association. People with more politically diverse online networks were also less likely to engage in political expression. While everyday self-presentation online may not be as threatening as expressing political views, the self-presentation literature may help explain why diverse networks can stifle political expression. In online networks, users often encounter multiple audiences in the form of context collapse (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, 2018; Gil-Lopez et al., 2018), which requires them to cater their self-presentation to people in their networks for whom messages are not targeted but could see them anyway and find them problematic (i.e., “the lowest common denominator”) (Hogan, 2010). In highly politically polarized spaces online, an “ideological context collapse” seems to be associated with perceptions of potential punishments and negative social repercussions. Therefore, it is plausible that having even a small number of powerful dissidents in a network could lead to political self-censorship. As networks get more diverse and have more disagreeable others, the chances of having more people who could potentially sanction the user are even greater. However, against our expectations, the mere size of one’s network was not associated with people’s FOSSs. This suggests that it is not the number of people one is virtually connected with but the perceived diversity of one’s audience that matters more for online expression.

Perhaps most importantly, fearing social sanctions was negatively related to different forms of political expression including sharing news, posting political opinions, commenting on, and liking political posts on Facebook. People who feared being socially or professionally punished for expressing political views were less likely to do so. This finding is a novel corroboration of Noelle-Neumann’s (1993) original propositions and illustrates how contemporary fears in a social media environment can limit political speech. While this is in line with previous findings (e.g., Neubaum & Krämer, 2018), our study suggests these social fears are very powerful because they apply to mostly the same degree for both higher commitment forms of expression like sharing news and expressing opinions, as well as lower commitment behaviors like commenting on or liking political content (Lane et al., 2019; Vaccari et al., 2015).

We also found that FOSSs varied slightly among political partisans: Republicans were somewhat more likely to fear social sanctions for expressing themselves than Democrats. This is consistent with polls suggesting that Republicans are more concerned about punishment for political speech (Pew Research Center, 2021a, 2021b). While our data do not allow us to pinpoint why such differences emerge, future research should explore several possible explanations for these partisan differences, including Republican politicians’ accusations of censorship on social media platforms, as well as increased public attention on the perceived negative ramifications of political speech (Norris, 2023). Regardless of its origin, it is important to note that Republicans and Democrats mostly did not differ in the extent to which FOSSs influenced expression; members of both parties who feared social sanctions were for the most part equally likely to avoid expressing political views online.

Taken together, the results of this study present a novel view on how one’s digital social environment can shape political expression. While the mechanism we find here clearly resembles Noelle-Neumann’s (1993) predictions of social fears fostering spiraling silence, our findings extend this line of research in several important ways. First, by moving beyond topical opinion climates and focusing more on the general ideological diversity in one’s digital environment, we are able to examine how people’s perceptions of their own social media networks can trigger fears of social sanctions and inhibit political expression. This is one of the first studies to show that perceived ideological diversity increases people’s fears of being socially or professionally punished for expressing themselves on social media. In a highly polarized society like the USA, this has important implications for the quality of political debates. Even the presence of someone from a different political party may increase fears about political expression and reduce one’s propensity to actually share their political views. The silencing mechanism, thus, applies not only to opinion disagreements but also ideological disagreements. Second, we move beyond measuring dispositional FSI to examine fears about specific social sanctions that can result from political expression online. In this way, our measure of FOSSs reflects contemporary concerns that many social media users hold, rather than personal traits. One interesting future application of the measure would be to examine how fears of online social sanctions are influenced by a broad set of perceived affordances in different channels online (Fox & McEwan, 2017). Third, our survey data allows us to overcome limitations inherent in the behavioral intention items that are typically employed in spiral of silence experiments to instead capture people’s (self-reported) political expression. This also allowed us to capture both high and low commitment forms of political expression that are common on social media. It is striking that fears of social sanctions are not only negatively related to high commitment political expression but also more innocuous actions such as liking.

On a practical level, this study illustrates an important paradox of online political expression. Deliberation is often considered a benchmark of democracy, but deliberation is only possible if diverse viewpoints are discussed. Polls (Pew Research Center, 2021a, 2021b) and our study show that many people are clearly afraid of the consequences of sharing their political views on social media, particularly if they exist in diverse online networks. In some instances, these concerns are justified; there are countless examples of public shaming and online firestorms for saying the wrong thing on social media (Johnen et al., 2018), particularly about politics. Rather than risk the potential consequences, many people just simply refrain from sharing their political views on social media. This has important consequences for political debate and opinion climates. Notably, it limits whose voice is heard in online political discussions. People who are fearful of speaking out may have legitimate and reasonable things to say but hold back, falling into a spiral of silence that can limit the viewpoints in the public sphere. Second, it allows people who are not afraid of social sanctions and freely engage in political expression online to have more voice in political debates. Given that political discussions online are notoriously hostile, this raises important questions about what people are willing to say when they are not concerned about alienating others or the social consequences of unpopular political speech.

The study also has limitations of note. One key limitation here is the interpretation of causality, given that we are testing a psychological sequence without accounting for a full longitudinal approach with three waves. Theoretical mechanisms suggest that it is unlikely and counterintuitive for FOSSs to increase people’s perceived ideological network diversity, but experimental work should corroborate the effect of ideological diversity on FOSSs. Another limitation lies in the national context this study was conducted in. Clearly, the U.S. political system is more polarized than in many other countries, and the question of how the processes studied here operate in different national contexts remains open. Further, while our results indicate that perceived network diversity is associated with less online expression, it is possible that this process does not hold for all users—such as those high in ego involvement (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005) or whom Noelle-Neumann (1974) identified as the “hard core”—and such boundary conditions merit further study (see Matthes et al., 2010).

Some of the measures used in the study also introduce limitations. First, items tapping both perceived network diversity and network size could be considered proxy measures for theoretical constructs. In the case of perceived network diversity, our measure in some ways reflects context collapse in that people in diverse networks may have multiple audiences, which might contribute to the perception that some people in their network are able to socially sanction them for political speech. For network size, the measures may stand in for publicness or visibility in that posts made to larger networks are likely more public and visible to more people (Pearce & Malhotra, 2022). While these measures represent reasonable stand-ins, it is important to note that such proxy measures may have suppressed the strength of the relationships we found. Future work could build on this by more directly measuring concepts like context collapse, visibility, or publicness. Second, our measures do not allow us to know who respondents believe is able to sanction them or even whose sanctions they are concerned about. Some respondents may have been concerned with sanctions enacted by specific friends, family, or colleagues who have different ideological viewpoints (and are able to sanction), while others may have been concerned about social repercussions from their networks more generally—particularly in more diverse networks that presumably contain more people who could potentially punish them. Moving forward, it will be important to know more about exactly who people view as ‘able to sanction’ and the consequences of these perceptions. It is also important to note that questions measuring network diversity and size were not specific to Facebook, so it is possible that some respondents were thinking of multiple social media platforms they use or a different platform when answering these questions. We also measured the diversity of respondents’ entire online network, rather than the audience for their posts. It may be that users employ features of social media platforms to limit who in their network is able to see particular posts. Our expression measures were also specific to Facebook. It is possible that the observed relationships could be different on other social media platforms where users have different imagined audiences for posts or those that allow user anonymity (Yun et al., 2020). A final limitation is that we did not explicitly measure related constructs like generalized FOI or FSI. As a result, we are not able to compare the degree to which fear of social sanctions is distinct from these concepts, nor are we able to establish the relative explanatory power each has on political expression.

Conclusion

This study contributes to our understanding of political expression in digital spaces. While previous studies largely focus on how trait-based factors shape people’s political expression on social media, this work emphasizes the power of online networks and, perhaps more importantly, situational fears of social sanctions in determining online expression. Our results clearly indicate that the perceived ideological composition of users’ networks plays a role in whether they fear the consequences of political expression through social media and which expressive actions they engage in based on these expected consequences.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication online.

Data availability statement

Data used in this study are available upon reasonable request to the first author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Howard R. Marsh Endowment in the Department of Communication and Media at the University of Michigan.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Notes

It is possible that these studies may have been picking up on boundary conditions related to the spiral of silence, either due to their sample of college students (Kwon et al., 2015; Liu & Fahmy, 2011)—who may be less likely to silence themselves in the presence of opposition—or the necessary exclusion of those who would not voice an unpopular view online intrinsic to content analysis (Chaudhry & Gruzd, 2019).

We also ran cross-sectional OLS regression analyses with the four W1 expression variables serving as the dependent variables. The results are nearly identical to the analyses using W2 expression as the outcomes with a few exceptions. Network diversity did not significantly predict opinion expression, news commenting, or news liking in the cross-sectional models. See Supplementary Material for regression analyses.

Although we did not have hypotheses about whether online political expression changes over the month between waves, we also evaluated lagged dependent variable models that used political expression in Wave 2 as the dependent variable while controlling for W1 values of expression. In each of these models, the prior value of expression consumes much of the variance and relationships between fear of social sanctions and change in expression are not significant. This is unsurprising given the relatively short time between waves and that fear of social sanctions is unlikely to change considerably in a month.