-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jih-Hsuan (Tammy) Lin, Christine Linda Cook, Ji-Wei Yang, I wanna share this, but…: explicating invested costs and privacy concerns of social grooming behaviors in Facebook and users’ well-being and social capital, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 29, Issue 1, January 2024, zmad038, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The social grooming model (SGM), which theorizes social media users’ social grooming behaviors based on invested costs, is robust, reflecting various and nuanced social grooming styles. However, its core assumptions have not been validated. Using a nationally representative sample of 1,001 Taiwanese social media users, we explored costs and privacy for each social grooming behavior via a survey. Our results supported the hypotheses of the SGM. Users reported greater costs and reputational concerns for private topics than public topics, and higher costs for emotional and controversial topics than for informational and trending topics. With the new five styles identified in this study, social butterflies and meformers reported significantly greater social capital and well-being than lurkers; however, social butterflies reported greater invested costs in social grooming than meformers, indicating that being strategic is most efficient when it comes to social grooming, considering invested costs and the social benefits. SGM is robust and can reflect rich social grooming patterns.

Lay Summary

The social grooming model theorizes the content people post in social media based on the invested costs in social grooming behavior and the privacy one has to sacrifice. This model is robust, reflecting various and nuanced social grooming styles in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. In this study, we theorize and validate the constructs of costs and privacy (with a new construct of image awareness) and the core assumptions in this model. We explore how social media users’ understanding of privacy affected the ways they used social media to share general information, personal information, opinions on controversial topics, trends, and comments on others’ posts. The results support hypotheses in Lin’s original model, with more emotional and personal topics incurring higher privacy and invested costs than public topics or general information. We also found that the more socially active social grooming styles, “social butterflies” and “meformers,” reported greater social capital and well-being than lurkers. However, social butterflies invested more costs than meformers, indicating that strategic social grooming on Facebook is the most efficient style to lower costs but receive the same benefits. Lin’s (2019) model works as a scientifically sound lens to use when looking at interactions between people on social media.

Social grooming, repeated social interactions with others, is key to gradually forming social ties and accumulating various types of social capital (Donath, 2007) and social support (Kim & Tussyadiah, 2013). Research on social network sites (SNSs) in the past two decades has covered various types of social grooming behaviors in social media and how these behaviors influence social outcomes (Brandtzæg, 2012; Ellison et al., 2014). For example, posting on Facebook offers opportunities for others to socially interact with the user to form and maintain relationships (Ellison et al., 2014). Self-disclosure through SNSs promotes close relationship bonding through positive feedback and bridging social capital for users (Liu & Brown, 2014). While existing literature focuses on certain social grooming behaviors or various actions including game behaviors in social media (Brandtzæg, 2012), Lin (2019) proposed a social grooming model (SGM) based on signaling theory to reflect comprehensive types of social grooming behavior. Based on the costs and the perceived relevance to self, the SGM serves as a foundational framework to reflect dynamic types of users in social media in terms of how they socially groom with others, termed social grooming styles (Lin, 2019), and how these social grooming styles change and evolve over time (Lin & Hsieh, 2021).

Indeed, employing the social grooming style approach (i.e., a combination of different uses of each social grooming behavior) to classify and understand the rich forms of user social interactions has received empirical support (Brandtzæg, 2012; Lin, 2019; Lin & Hsieh, 2021). The style-based approach provides a lens for researchers to capture the rich types of social grooming styles users engaged in at the studied timeframe. Based on signaling theory, five social grooming behaviors were theorized from invested costs devoted to the shared content type and content topics (personal vs. public information) on social media. These costs are briefly theorized as “requiring time, resources, considerations of imagined audiences, and a sacrifice of privacy” (Lin, 2019, p. 92). However, they have not been validated and explicated through empirical examination and were only at the theoretical stage at the time of Lin’s (2019) publication. This study aims to further explicate and operationalize the construct of the invested “costs” of these social grooming behaviors from audiences and their associations with various types of social groomers.

Privacy is also a key factor affecting disclosed content in social media (Martin, 2016) and can be theorized as part of the invested costs (Chen, 2018) in these social grooming behaviors. Indeed, privacy concerns and dispositions toward the engaged social activities in social media can determine audiences’ willingness to adopt an SNS or not (Tufekci, 2008). The privacy calculus model describes a negotiation between disclosure costs and social benefits, and privacy concern of these social grooming behaviors is part of the complicated privacy management process (Chen, 2018; Lee & Yuan, 2020). As social grooming styles reflect strategic content disclosure, knowing how privacy concerns affect the invested costs and processes is critical to shedding light on the negotiation of engaged social grooming behaviors.

A nationally representative sample was surveyed in Taiwan to explicate SNSs users’ perceived costs and privacy considerations toward each social grooming behavior. We aim to validate the implicit assumptions of costs invested in each social grooming behavior in order to understand this negotiated process. We also examine privacy concerns and specific concerns about reputation among imagined audiences, which we call “image awareness,” to reflect a more comprehensive consideration of how image awareness influences content creation and engagement in social grooming in SNSs. As these costs were the foundation of the model, validating these assumptions is key to building a theory. This study is also the first to examine privacy alongside the SGM.

Theoretical background

SGM, social grooming behavior, and styles

What type of topics do Facebook users talk about on their shared posts or comments on others’ posts? Past literature (Donath, 2007; Ellison et al., 2014) has theorized these social media interactions as a form of social grooming. Focusing on theorizing the content users construct and share on Facebook, Lin (2019) theorized five types of social grooming behavior, and the framework of costs and privacy to structure these social grooming behaviors was thus termed the “social grooming model.” The SGM (Lin, 2019) was heavily based on the invested costs in signaling theory to theorize the types of various social grooming behaviors in SNSs, specifically focusing on the content one created to interact with others. Five social grooming behaviors (i.e., emotional vs. informational self-disclosure, private vs. public topics, and relationship maintenance behavior, which is operationalized as commenting on others’ posts; see Lin, 2019 for more details) were theorized based on signaling theory to serve as the foundation of the SGM.

Using these five social grooming behaviors, rich social interactions can be reflected by identifying the combination of various engagement levels in these five social grooming behaviors, forming a social grooming style. In other words, we can identify users’ social grooming style considering all these five behaviors. For example, in Lin’s (2019) SGM, she found that the SGM with these five social grooming behaviors can reflect various social grooming styles, including image managers, social butterflies, trend followers, relationship maintainers, and lurkers. Social butterflies engage in all these five social grooming behaviors frequently (they reported high frequency of engaging in all these five social grooming behaviors), whereas lurkers never engaged in any of these five social grooming behaviors (reported low to no frequency in all these behaviors). Image managers mainly engage in private posts (reporting high frequency in emotional and informational posts) and commenting on others’ posts, but never post about public topics, including controversial and trending topics (reporting low frequency). Trend followers reported medium frequency of engaging in posting about trending and non-controversial topics and also commented other people’s posts often. Relationship maintainers reported commenting on others’ posts frequently but no-to-low frequencies in other behaviors. Therefore, social grooming behaviors can form and reflect various social grooming styles. These styles of social butterflies, image managers, and others emerged based on the frequencies of these five social grooming behaviors and were named post-hoc. In a longitudinal panel study (Lin & Hsieh, 2021), users reported either persistent social grooming styles (i.e., remained the same style across time) or transitioned social grooming patterns (e.g., social butterfly to relationship maintainer). This SGM can also be applied to different platforms such as Instagram (Chien, 2020) and can be explored among different populations for different emerging styles. See Table 1 for an in-depth description of the relationship between social grooming behaviors and social grooming styles.

| Paper . | Lin (2019) SGM . | Lin and Hsieh (2021) . | Current study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core contribution |

| Longitudinal data showing latent transition analysis of social grooming styles at two times using panel data. | Validate the costs of each social grooming behavior based on the core assumptions in Lin (2019). Define, theorize, and operationalize costs in these social grooming behaviors. Social butterflies and meformers reported the same level of social benefits, but meformers reported significantly lower costs than social butterflies. Strategic social grooming is most efficient. |

| Core Assumptions |

| Social grooming styles predicted by the SGMs were the same across time. However, individuals might transit from one style to another style. Results showed that passive styles (maintainers and lurkers) maintained passive; and half of the active styles transited to passive styles. | Costs can be operationalized as planning time and actual time of writing the posts, mental efforts, censoring and canceling behaviors. Privacy concern is also part of invested costs. |

| Social outcomes | Greater social grooming activities do not lead to greater social capital. Strategic social grooming style (i.e., image manager) reported the greatest bonding social capital among the five styles. | Persistent image managers (e.g., image manager at both Time1 and Time2) reported the greatest social outcomes. | The SGM reflects two new styles. Strategic style gained the most social outcomes. |

| Paper . | Lin (2019) SGM . | Lin and Hsieh (2021) . | Current study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core contribution |

| Longitudinal data showing latent transition analysis of social grooming styles at two times using panel data. | Validate the costs of each social grooming behavior based on the core assumptions in Lin (2019). Define, theorize, and operationalize costs in these social grooming behaviors. Social butterflies and meformers reported the same level of social benefits, but meformers reported significantly lower costs than social butterflies. Strategic social grooming is most efficient. |

| Core Assumptions |

| Social grooming styles predicted by the SGMs were the same across time. However, individuals might transit from one style to another style. Results showed that passive styles (maintainers and lurkers) maintained passive; and half of the active styles transited to passive styles. | Costs can be operationalized as planning time and actual time of writing the posts, mental efforts, censoring and canceling behaviors. Privacy concern is also part of invested costs. |

| Social outcomes | Greater social grooming activities do not lead to greater social capital. Strategic social grooming style (i.e., image manager) reported the greatest bonding social capital among the five styles. | Persistent image managers (e.g., image manager at both Time1 and Time2) reported the greatest social outcomes. | The SGM reflects two new styles. Strategic style gained the most social outcomes. |

| Paper . | Lin (2019) SGM . | Lin and Hsieh (2021) . | Current study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core contribution |

| Longitudinal data showing latent transition analysis of social grooming styles at two times using panel data. | Validate the costs of each social grooming behavior based on the core assumptions in Lin (2019). Define, theorize, and operationalize costs in these social grooming behaviors. Social butterflies and meformers reported the same level of social benefits, but meformers reported significantly lower costs than social butterflies. Strategic social grooming is most efficient. |

| Core Assumptions |

| Social grooming styles predicted by the SGMs were the same across time. However, individuals might transit from one style to another style. Results showed that passive styles (maintainers and lurkers) maintained passive; and half of the active styles transited to passive styles. | Costs can be operationalized as planning time and actual time of writing the posts, mental efforts, censoring and canceling behaviors. Privacy concern is also part of invested costs. |

| Social outcomes | Greater social grooming activities do not lead to greater social capital. Strategic social grooming style (i.e., image manager) reported the greatest bonding social capital among the five styles. | Persistent image managers (e.g., image manager at both Time1 and Time2) reported the greatest social outcomes. | The SGM reflects two new styles. Strategic style gained the most social outcomes. |

| Paper . | Lin (2019) SGM . | Lin and Hsieh (2021) . | Current study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core contribution |

| Longitudinal data showing latent transition analysis of social grooming styles at two times using panel data. | Validate the costs of each social grooming behavior based on the core assumptions in Lin (2019). Define, theorize, and operationalize costs in these social grooming behaviors. Social butterflies and meformers reported the same level of social benefits, but meformers reported significantly lower costs than social butterflies. Strategic social grooming is most efficient. |

| Core Assumptions |

| Social grooming styles predicted by the SGMs were the same across time. However, individuals might transit from one style to another style. Results showed that passive styles (maintainers and lurkers) maintained passive; and half of the active styles transited to passive styles. | Costs can be operationalized as planning time and actual time of writing the posts, mental efforts, censoring and canceling behaviors. Privacy concern is also part of invested costs. |

| Social outcomes | Greater social grooming activities do not lead to greater social capital. Strategic social grooming style (i.e., image manager) reported the greatest bonding social capital among the five styles. | Persistent image managers (e.g., image manager at both Time1 and Time2) reported the greatest social outcomes. | The SGM reflects two new styles. Strategic style gained the most social outcomes. |

Since the SGM is heavily based on the invested costs in signaling theory, we focus on theorizing these costs and validating whether certain social grooming behaviors require greater costs than others implicitly stated in the original SGM in Lin (2019). Signaling theory originated in biology to explain how animals used signals to communicate intent, despite the costs this signaling may bring to survival (Zahavi & Zahavi, 1999). Donath (2007) further employed the signaling theory to theorize humans’ social interactions as social grooming behaviors signaling various intentions or self-status.

Lin’s (2019) SGM provides a theoretical lens to categorize various types of social grooming behaviors based on two dimensions: self-relevance and invested costs. Self-relevance is more explicit, as it categorizes shared content as disclosing information regarding the self (i.e., private topic) or discussing personal opinions based on news or popular trends (i.e., public topic). In the original piece (Lin, 2019), implicit assumptions of self-relevance and invested costs were theorized but were never validated. Private topics are theorized as requiring the sacrifice of more privacy (i.e., a type of costs) than public topics (Assumption 1). Regarding invested costs, theoretically, the model derived the implicit assumption that emotional self-disclosure should require greater costs than informational-disclosure, and discussing controversial topics requires greater effort than simply sharing trending content (Assumption 2). Commenting on others’ posts (relationship maintenance) is theorized as requiring the fewest costs compared to other social grooming behaviors (Assumption 3). However, in human social grooming behavior, what are the actual costs?

Costs were implicitly discussed in previous literature, but mostly were discussed as the efforts put into the formation of an SNSs profile to gain trust and signal reliable information. For example, using a person’s real name in SNSs sacrifices privacy, but the information provided will be deemed more reliable than information provided by an anonymous user (Donath & boyd, 2004). Linking one’s SNSs profile with other social contacts, such as showcasing friends, also signals that this identity is more reliable (Donath & boyd, 2004). These implicitly indicated that self-information disclosure and disclosing social ties are invested costs. We aim to explicate the perceived costs of engaging in social grooming behaviors in this study.

Costs of social grooming behaviors

What are the invested costs when composing a certain topic as a social grooming behavior? Lin (2019,) briefly discussed these costs as “time, resources, considerations of imagined audiences, and a sacrifice of privacy” (p. 92). Regarding time, despite calls for “time spent on social media” to be divided into a multifaceted construct instead of a single measure (see Ellison et al., 2014), most social grooming articles still talk about SNS time in a macro sense (see Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). We know little empirically regarding just how long it takes to construct a post, though we know intuitively that there is a time cost. For example, simply saying “hi” was a casual post back in 2006 and remains a part of social grooming, but today people are more likely to craft more elaborate posts that present an ideal self (see Hollenbaugh, 2021; Schlosser, 2020) to their imagined audience (see Litt & Hargittai, 2016). When posting different types of posts, logically, varying amounts of actual writing time are required. For example, actually writing a post about controversial issues may take more time than simply forwarding or posting a trending photo or meme. Writing an emotional post may also require more actual time than a simple informational post about the gourmet food one is enjoying. However, actual time may not be an ideal indicator on its own because it is inconsistent; one can also spend a lot of time describing food, whereas one can spend only one minute to describe one’s mood.

Planning time could therefore be an indicator of cost, defined as the time consumed by constructing and planning the post. One can spend ten actual minutes writing an emotional post, but several hours thinking about the presentation structure or the creative punchline. A user perhaps spent lots of time researching information and opinions regarding controversial issues before actually creating the controversial post. Relationship maintenance behaviors such as comments and reactions probably take the least amount of time to plan. However, we do not have the empirical basis to know this for sure, as time is still too often measured as an all-consuming statistic. The study aims to break time down into planning and posting time to better capture the granularity of time spent on each social grooming behavior.

Mental effort is another indicator of invested costs, as users may collect sharable content during their lives and constantly think about how they can share it. Controversial topics should theoretically require greater mental and cognitive efforts from users to read and process various arguments while constructing their own arguments. They may craft their arguments by weighing the impact and the potential discussions afterward, which may influence their reputation. Emotional posts may require users to go through complicated negotiation processes between privacy and context collapse (Hogan, 2010). When various audiences (i.e., coworkers, family, friends, etc.) are all seeing what one posts, people may be more inclined to present rather than disclose (Schlosser, 2020), and if they do disclose, it will probably be done with more care than if they were sharing the information in person with a trusted other party. Since comments (theorized as relationship maintenance behaviors) are already directed at a single person and do not necessitate much self-disclosure, these would theoretically also be low in mental effort. Therefore, different from the actual or planning time, mental effort captures the overall perception of how much they devote their cognitive efforts to the posts.

In addition to time and effort, behavioral indicators reflect the additional actions invested in posting the content on social media for social grooming. These indicators—frequency of censoring the post and frequency of canceling the post—describe the censoring process of examining the content to carefully calculate the potential gains and losses when sharing the post. Leaving a comment on a friend’s post is a type of mass-personal communication (O’Sullivan & Carr, 2018) and requires a censoring process to make sure the content fits the norm among the “lowest common denominators” (Hogan, 2010, p. 383). However, controversial takes on complicated arguments may require greater costs in censoring processes. Both commenting and self-censorship have a role to play in social media self-presentation (Hollenbaugh, 2021; Schlosser, 2020). We therefore include these two indicators, frequency of censoring the post and frequency of canceling the post, as part of the invested costs of each social grooming behavior.

Based on the above five indicators of the invested costs in social grooming behavior, we can categorize these five indicators into effort-based versus behavioral-based indicators. Effort-based indicators include planning time and mental effort, which focus on the thought-planning phase. Behavioral-based indicators include the actual time of writing the posts, censoring, and canceling behaviors. All social media users can report the effort-based indicators regardless of their actual posting frequencies. For those who do not post any controversial posts, they may have a hard time reporting their actual time behavior, but they can evaluate the efforts to be invested in the posts. Based on the original assumptions from the SGM, we propose the following hypotheses and research question:

H1a. Emotional posts should require greater effort-based costs than informational posts.

H1b. Controversial posts should require greater effort-based costs than non-controversial posts.

H1c. Commenting should require the fewest effort-based costs among the five social grooming behaviors.

RQ1: How do effort-based costs differ between emotional and controversial posts?

Regarding the behavioral-based costs, since each social grooming style engages in social grooming behavior in different ways, and some styles do not post anything at all, we therefore examine the behavioral-based costs of each social grooming behavior between these social grooming styles. For example, lurkers do not post anything, and may report zero for all these behaviors. Therefore, we cannot examine the behavioral-based costs directly within each person but have to consider their social grooming styles in this study.

RQ2: How does each social grooming style report behavior-based costs, including (a) actual post time, (b) frequency of content censoring, and (c) frequency of canceling the posts, for each social grooming behavior?

Privacy calculus and social grooming behavior

In the SGM, disclosure of private information (i.e., self-relevance, private or public topic) is another main dimension of costs. The model only distinguishes the topic based on self-relevance; privacy concerns associated with specific types of content have yet to be addressed in extant literature. We break down privacy concerns further than in the extended privacy calculus model (see Dinev & Hart, 2006). The privacy calculus model is essentially how people compare the costs (e.g., loss of privacy regarding thoughts and opinions) and benefits (e.g., increased social capital) when they decide to self-disclose on the internet. Even in more recent publications on privacy calculus theory, privacy concerns are typically combined in a single measurement about everyone who could have access to the information posted online as opposed to specifying specific people and how the loss of privacy to them might be more important than losing privacy to another person (see Chen, 2018). We can therefore “calculate” whether it is worth posting information or not using the privacy calculus model. We have already seen, though, that privacy is not the only concern when posting on social media. Time is a concern, for example. Lin (2019) actually alluded to another major concern that may be linked to privacy, but remains separate, when she described one type of social groomer as “image managers”: reputational concerns.

Whenever a person posts to social media, they are self-disclosing to at least some extent. Those high in privacy self-efficacy might be disclosing to a more specific audience, while lurkers (Lin, 2019) may not disclose at all because they do not post, but each post reveals something about the person—their interests, concerns, etc.—to a collapsed context, which is to say all of their social media connections, irrespective of how they know them offline (Litt & Hargittai, 2016). For example, a person may be comfortable presenting images of themselves cutting loose at a party to family and friends, while they may not want their boss to see them acting so wild (Hogan, 2010; Vitak, 2012). In other words, audience matters on social media, especially when their potential feedback on posts is taken into account (Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021). Therefore, to fully capture all of the possible costs of the various social grooming behaviors, we include not only traditional measures of privacy costs and measures of time and mental effort, but also a newly-developed measure of reputational concern, which we call “image awareness,” to grasp which audiences are most important to which social grooming styles, and how much a person considers their post’s effect on other social groups’ image of them before posting. In other words, we un-collapse the context of social media (Davis & Jurgenson, 2014) to see how conscious people are of the various pieces that form their imagined audience (Litt & Hargittai, 2016). In this way, we not only extend the privacy calculus model by adding in the full complement of costs, but we also add to the available tools we can use to understand even more theorized costs than were previously measured. More specifically, we address the following research questions:

RQ3: How does participants’ image awareness differ when engaging in different social grooming behaviors?

RQ4: Does each social grooming style users’ image awareness differ when engaging in different social grooming behaviors?

To respond to the audiences’ reactions and privacy concerns when dealing with sharing information under context collapse, social media platforms allow users to adjust their privacy settings to share their content with customized audiences. We theorize that spending effort to adjust their privacy settings before sharing their content is a part of the invested cost regarding privacy. As privacy settings are an important strategy used to enable sharing of information and thoughts within their “comfort zone” with desired audiences, we explore the role of privacy settings and social grooming styles.

RQ5: How often do overall users adjust their privacy settings for each social grooming post?

RQ6: Do differing social grooming style users report their frequency of adjusting their privacy settings for each social grooming behavior differently?

Social grooming styles on social outcomes

Social interactions and social media use have been found to link with social benefits in existing literature in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Liu et al., 2016). A meta-analysis of 58 studies showed that social media use is positively linked to bridging and bonding social capital (Liu et al., 2016), and is particularly good for accumulating bridging social capital over bonding social capital (Ellison et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2016). In addition to social capital, a meta-analysis of 38 studies (Chu et al., 2023) showed that the valence and honesty of self-disclosure were positively associated with psychological well-being. The quantity of self-disclosures is not correlated with well-being. These correspond to Lin’s (2019) argument that strategic social grooming styles such as posting private topics and relationship maintenance lead to greater social outcomes than social butterflies who post every type of social grooming behavior on Facebook. Wang et al. (2023), focusing on social interactions, also indicated that daily social interactions can have a positive influence on coworkers’ social connectedness and daily life satisfaction in the context of work (Wang et al., 2023). Whereas these studies focused only on a certain type of behavior or general Facebook use time, scholars gradually adopted the style approach to explicate the styles of social media use and their influence on social outcomes.

Lin (2019) examined how social grooming styles link to various social outcomes, including well-being and social capital, both in nationally representative, cross-sectional results (Lin, 2019) and longitudinal panel data using the social grooming transition styles (Lin & Hsieh, 2021). The contribution of previous literature is that social grooming style can capture various usage combinations of social grooming behavior and is associated with social capital and well-being differently. For example, lurkers who do not engage in any of the social grooming behaviors received the least social benefits. While social butterflies engage in every social grooming behavior and are associated with greater bridging social capital, image managers engage in strategic ways by picking certain social grooming behaviors, instead of all, and are associated with greater bonding and bridging social capital than other styles. In a panel study from 2018 to 2020 (Lin & Hsieh, 2021), various transition styles of social grooming styles between two time points have been identified, suggesting that social media users change their social grooming styles over time. In this study, we recruit a completely different sample, which may generate new social grooming styles, and aim to test how social grooming styles in this sample are associated with the social benefits in order to show whether this SGM can reflect various patterns and outcomes.

RQ7: How do social grooming styles differ regarding their (a) bonding and bridging social capital and (b) well-being?

Method

Participants and procedure

This study was reviewed and approved by National Chengchi University’s Institutional Review Board, #NCCU-REC-202001-I001. A total of 283 participants (25.4% men and 73.9% women) were recruited online through a local university community for a pilot study, aiming to examine the factor structure of the self-developed image awareness scale and reliability and validity of other scales. Participants filled out a questionnaire containing each scale and the initial image awareness scale. Two female participants were dropped because they failed the attention check; the average age of the rest of the sample was 23.71 (SD = 6.35).

For the main study, an online investigation was entrusted to a market research company: NielsenIQ Taiwan Ltd. To increase the sample’s representativeness, we first divided the national population into subgroups by sex, age, and place of residence according to national census data. The target age group was set to between 18 and 60. In the next step, we set the quota of every subgroup in our sample based on the same proportion in the national population. Finally, the questionnaire was published on the company’s website. NielsenIQ monitored the sample proportion during the data collecting phase and excluded participants who failed the attention check. After collecting sufficient data (N = 1,000), the questionnaire was closed.

A total of 1,001 respondents (500 men and 501 women) from Taiwan completed the questionnaire. The average age was 39.62 (SD = 11.34), ranging from 18 to 60. This sample was a nationally representative sample, meaning the ages, sex, and geographic locations of the participants are a facsimile of the Taiwanese population at large. Each participant uses Facebook 5.9 (SD = 1.84) days per week on average and spends roughly 133.79 (SD = 149.50) minutes on Facebook per day. Our sample’s mean number of Facebook friends is 332.94 (SD = 508.28).

Measurement

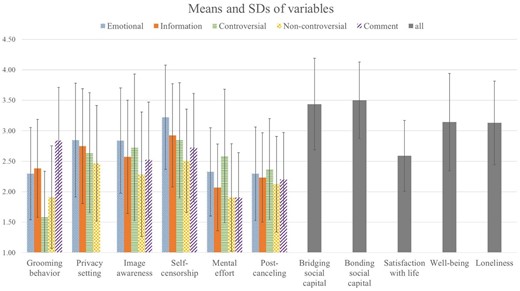

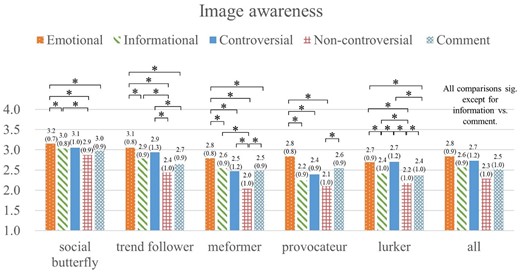

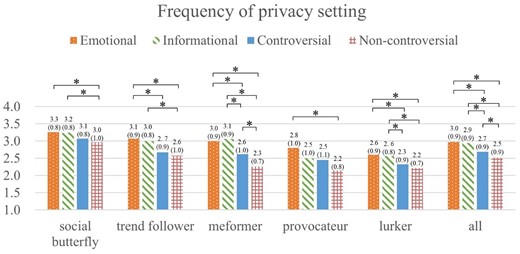

Table 2 describes the means and SDs of all variables, and Figure 1 presents the error bars of variables and their statistics. Facebook was chosen to serve as the social media platform in this study because it is the most used social media in Taiwan; a nationally representative sample reported 97%–98% of Taiwanese people were using Facebook between 2016 and 2020 (Taiwan Communication Survey, 2021).

| . | M . | SD . | N . | α . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.30 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.85 | 0.93 | 859 | |

| Image awareness | 2.77 | 0.82 | 1,001 | 0.93 |

| Actual post time | 28.73 | 57.65 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 39.52 | 82.94 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.32 | 0.73 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 3.22 | 0.86 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.29 | 0.77 | 879 | |

| Information post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.35 | 0.81 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.75 | 0.94 | 860 | |

| Image awareness | 2.53 | 0.90 | 1,001 | 0.96 |

| Actual post time | 25.56 | 65.97 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 29.61 | 69.23 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.07 | 0.71 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.92 | 0.85 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.23 | 0.73 | 879 | |

| Controversial post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.58 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.64 | 0.99 | 428 | |

| Image awareness | 2.68 | 1.17 | 1,001 | 0.98 |

| Actual post time | 19.42 | 53.06 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 36.36 | 93.97 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.58 | 1.10 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.84 | 0.94 | 433 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.37 | 0.83 | 433 | |

| Non-controversial/trend post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.91 | 0.84 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.47 | 0.95 | 621 | |

| Image awareness | 2.25 | 1.00 | 1,001 | 0.97 |

| Actual post time | 15.60 | 60.60 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 20.42 | 56.77 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.88 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.51 | 0.85 | 635 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.12 | 0.79 | 635 | |

| Comment to others | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.84 | 0.87 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | NAa | NAa | NAa | |

| Image awareness | 2.47 | 0.91 | 1,001 | .95 |

| Actual post time | 13.30 | 53.54 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 13.48 | 35.53 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.74 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.72 | 0.89 | 936 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.20 | 0.77 | 936 | |

| Bonding social capital | 3.44 | 0.75 | 1,001 | 0.85 |

| Bridging social capital | 3.50 | 0.63 | 1,001 | 0.83 |

| Loneliness | 2.59 | 0.58 | 1,001 | 0.78 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.14 | 0.80 | 1,001 | 0.90 |

| Well-being | 3.13 | 0.69 | 1,001 | 0.94 |

| . | M . | SD . | N . | α . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.30 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.85 | 0.93 | 859 | |

| Image awareness | 2.77 | 0.82 | 1,001 | 0.93 |

| Actual post time | 28.73 | 57.65 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 39.52 | 82.94 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.32 | 0.73 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 3.22 | 0.86 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.29 | 0.77 | 879 | |

| Information post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.35 | 0.81 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.75 | 0.94 | 860 | |

| Image awareness | 2.53 | 0.90 | 1,001 | 0.96 |

| Actual post time | 25.56 | 65.97 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 29.61 | 69.23 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.07 | 0.71 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.92 | 0.85 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.23 | 0.73 | 879 | |

| Controversial post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.58 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.64 | 0.99 | 428 | |

| Image awareness | 2.68 | 1.17 | 1,001 | 0.98 |

| Actual post time | 19.42 | 53.06 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 36.36 | 93.97 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.58 | 1.10 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.84 | 0.94 | 433 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.37 | 0.83 | 433 | |

| Non-controversial/trend post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.91 | 0.84 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.47 | 0.95 | 621 | |

| Image awareness | 2.25 | 1.00 | 1,001 | 0.97 |

| Actual post time | 15.60 | 60.60 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 20.42 | 56.77 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.88 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.51 | 0.85 | 635 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.12 | 0.79 | 635 | |

| Comment to others | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.84 | 0.87 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | NAa | NAa | NAa | |

| Image awareness | 2.47 | 0.91 | 1,001 | .95 |

| Actual post time | 13.30 | 53.54 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 13.48 | 35.53 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.74 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.72 | 0.89 | 936 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.20 | 0.77 | 936 | |

| Bonding social capital | 3.44 | 0.75 | 1,001 | 0.85 |

| Bridging social capital | 3.50 | 0.63 | 1,001 | 0.83 |

| Loneliness | 2.59 | 0.58 | 1,001 | 0.78 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.14 | 0.80 | 1,001 | 0.90 |

| Well-being | 3.13 | 0.69 | 1,001 | 0.94 |

Notes. Means, standard deviations, sample sizes, and internal reliabilities of measurements. Variables with a blank reliability coefficient are single-item measures.

Users cannot adjust the privacy settings of their comment on Facebook. This item was not shown in the “comment to others” section in the questionnaire.

| . | M . | SD . | N . | α . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.30 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.85 | 0.93 | 859 | |

| Image awareness | 2.77 | 0.82 | 1,001 | 0.93 |

| Actual post time | 28.73 | 57.65 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 39.52 | 82.94 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.32 | 0.73 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 3.22 | 0.86 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.29 | 0.77 | 879 | |

| Information post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.35 | 0.81 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.75 | 0.94 | 860 | |

| Image awareness | 2.53 | 0.90 | 1,001 | 0.96 |

| Actual post time | 25.56 | 65.97 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 29.61 | 69.23 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.07 | 0.71 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.92 | 0.85 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.23 | 0.73 | 879 | |

| Controversial post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.58 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.64 | 0.99 | 428 | |

| Image awareness | 2.68 | 1.17 | 1,001 | 0.98 |

| Actual post time | 19.42 | 53.06 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 36.36 | 93.97 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.58 | 1.10 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.84 | 0.94 | 433 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.37 | 0.83 | 433 | |

| Non-controversial/trend post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.91 | 0.84 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.47 | 0.95 | 621 | |

| Image awareness | 2.25 | 1.00 | 1,001 | 0.97 |

| Actual post time | 15.60 | 60.60 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 20.42 | 56.77 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.88 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.51 | 0.85 | 635 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.12 | 0.79 | 635 | |

| Comment to others | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.84 | 0.87 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | NAa | NAa | NAa | |

| Image awareness | 2.47 | 0.91 | 1,001 | .95 |

| Actual post time | 13.30 | 53.54 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 13.48 | 35.53 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.74 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.72 | 0.89 | 936 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.20 | 0.77 | 936 | |

| Bonding social capital | 3.44 | 0.75 | 1,001 | 0.85 |

| Bridging social capital | 3.50 | 0.63 | 1,001 | 0.83 |

| Loneliness | 2.59 | 0.58 | 1,001 | 0.78 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.14 | 0.80 | 1,001 | 0.90 |

| Well-being | 3.13 | 0.69 | 1,001 | 0.94 |

| . | M . | SD . | N . | α . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.30 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.85 | 0.93 | 859 | |

| Image awareness | 2.77 | 0.82 | 1,001 | 0.93 |

| Actual post time | 28.73 | 57.65 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 39.52 | 82.94 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.32 | 0.73 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 3.22 | 0.86 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.29 | 0.77 | 879 | |

| Information post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.35 | 0.81 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.75 | 0.94 | 860 | |

| Image awareness | 2.53 | 0.90 | 1,001 | 0.96 |

| Actual post time | 25.56 | 65.97 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 29.61 | 69.23 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.07 | 0.71 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.92 | 0.85 | 879 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.23 | 0.73 | 879 | |

| Controversial post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.58 | 0.76 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.64 | 0.99 | 428 | |

| Image awareness | 2.68 | 1.17 | 1,001 | 0.98 |

| Actual post time | 19.42 | 53.06 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 36.36 | 93.97 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 2.58 | 1.10 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.84 | 0.94 | 433 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.37 | 0.83 | 433 | |

| Non-controversial/trend post | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 1.91 | 0.84 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | 2.47 | 0.95 | 621 | |

| Image awareness | 2.25 | 1.00 | 1,001 | 0.97 |

| Actual post time | 15.60 | 60.60 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 20.42 | 56.77 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.88 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.51 | 0.85 | 635 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.12 | 0.79 | 635 | |

| Comment to others | ||||

| Frequency of publishing | 2.84 | 0.87 | 1,001 | |

| Privacy setting | NAa | NAa | NAa | |

| Image awareness | 2.47 | 0.91 | 1,001 | .95 |

| Actual post time | 13.30 | 53.54 | 1,001 | |

| Planning post time | 13.48 | 35.53 | 1,001 | |

| Perceived mental effort | 1.91 | 0.74 | 1,001 | |

| Self-censoring | 2.72 | 0.89 | 936 | |

| Post-canceling | 2.20 | 0.77 | 936 | |

| Bonding social capital | 3.44 | 0.75 | 1,001 | 0.85 |

| Bridging social capital | 3.50 | 0.63 | 1,001 | 0.83 |

| Loneliness | 2.59 | 0.58 | 1,001 | 0.78 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.14 | 0.80 | 1,001 | 0.90 |

| Well-being | 3.13 | 0.69 | 1,001 | 0.94 |

Notes. Means, standard deviations, sample sizes, and internal reliabilities of measurements. Variables with a blank reliability coefficient are single-item measures.

Users cannot adjust the privacy settings of their comment on Facebook. This item was not shown in the “comment to others” section in the questionnaire.

Social grooming behavior

We used the same questions regarding social grooming behavior as Lin (2019), shown in Table 3.

| Social grooming behavior . | Items (4-point scale)a . | M (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional self-disclosure | How often do you share your emotions on your Facebook wall? | 2.30 (0.76) |

| Informational self-disclosure | How often do you share daily general events on your Facebook wall (such as where you are, what you are doing, eating, watching or listening to?) | 2.38 (0.31) |

| Controversial topics | How often do you discuss controversial issues on your Facebook wall? | 1.58 (0.76) |

| Non-controversial topics | How often do you discuss current noncontroversial and trending topics? | 1.91 (0.84) |

| Relationship maintenance | How often do you respond to other people’s posts on Facebook (including like-clicks, emojis, or comments) | 2.84 (0.87) |

| Social grooming behavior . | Items (4-point scale)a . | M (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional self-disclosure | How often do you share your emotions on your Facebook wall? | 2.30 (0.76) |

| Informational self-disclosure | How often do you share daily general events on your Facebook wall (such as where you are, what you are doing, eating, watching or listening to?) | 2.38 (0.31) |

| Controversial topics | How often do you discuss controversial issues on your Facebook wall? | 1.58 (0.76) |

| Non-controversial topics | How often do you discuss current noncontroversial and trending topics? | 1.91 (0.84) |

| Relationship maintenance | How often do you respond to other people’s posts on Facebook (including like-clicks, emojis, or comments) | 2.84 (0.87) |

1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often.

| Social grooming behavior . | Items (4-point scale)a . | M (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional self-disclosure | How often do you share your emotions on your Facebook wall? | 2.30 (0.76) |

| Informational self-disclosure | How often do you share daily general events on your Facebook wall (such as where you are, what you are doing, eating, watching or listening to?) | 2.38 (0.31) |

| Controversial topics | How often do you discuss controversial issues on your Facebook wall? | 1.58 (0.76) |

| Non-controversial topics | How often do you discuss current noncontroversial and trending topics? | 1.91 (0.84) |

| Relationship maintenance | How often do you respond to other people’s posts on Facebook (including like-clicks, emojis, or comments) | 2.84 (0.87) |

| Social grooming behavior . | Items (4-point scale)a . | M (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional self-disclosure | How often do you share your emotions on your Facebook wall? | 2.30 (0.76) |

| Informational self-disclosure | How often do you share daily general events on your Facebook wall (such as where you are, what you are doing, eating, watching or listening to?) | 2.38 (0.31) |

| Controversial topics | How often do you discuss controversial issues on your Facebook wall? | 1.58 (0.76) |

| Non-controversial topics | How often do you discuss current noncontroversial and trending topics? | 1.91 (0.84) |

| Relationship maintenance | How often do you respond to other people’s posts on Facebook (including like-clicks, emojis, or comments) | 2.84 (0.87) |

1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often.

Frequency of adjusting privacy settings

Privacy settings were measured by a single item: “Before posting, how often do you change your privacy settings so that only certain people can see your post?” for each social grooming behavior, except for commenting to others, via a 4-point scale (1 = never, 4 = often). For those who did not know how to change their privacy settings, an additional option labeled “I don’t know how to set the privacy settings” was added.

Image awareness

The authors developed a 16-item scale to measure image awareness, indicating how aware people were of how different posts could affect their public image or reputation among different social groups present in the collapsed context of social media. Although other scales do explore similar concepts (e.g., the appearance-related social media consciousness scale by Choukas-Bradley et al., 2020), we were unable to find a preexisting scale that (a) separated out different potential audiences of the content that was being posted and (b) did not focus exclusively on physical image, but dealt instead with reputation and public image in a more abstract sense. The original scale was composed of 16 items inspired by de Cremer and Tyler’s (2005) concern for reputation scale, but expanded for additional audiences and adapted to the social media context. Four items were deleted after an exploratory factor analysis run using our pilot data, and another item was deleted after a confirmatory factor analysis run on our formal data. The full exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results can be found in our Supplementary Material, while the full scale can be found in Appendix A. By using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much), participants expressed how much effort they made to consider the reputational consequences among different groups following their social grooming behavior.

Behavioral-based and effort-based costs

Behavioral-based costs were operationalized as the actual post time, in which participants wrote down the time they usually needed (hours and minutes) to design, create, and publish their posts or comments for each social grooming behavior. Time was calculated as minutes for statistical analysis. Participants rated their frequency of self-censorship (“How often did you recheck the content before you published your post?”) and post-canceling (“How often did you cancel your post before you published it?”) on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all/never, 4 = lots of/often) for each social grooming behavior.

Effort-based costs include planning post time and perceived mental effort. Participants responded to a hypothetical question (“Assuming you’re planning to design, establish and publish a post right now, how much time do you think it would cost?”) for planning post time. As for perceived mental effort, participants answered the question “On average, how much effort did you put into the post before you published it?” using a 4-point scale (1 = not at all/never, 4 = lots of/often) for each social grooming behavior.

Bridging/bonding social capital

The social capital scale (Williams, 2006) was employed to measure both types of social capital. To shorten the questionnaire, six items that were the same as Lin (2019) used and four additional items (“There is someone I can turn to for advice about making very important decisions” and “If I needed an emergency loan of $500, I know someone I can turn to” for bonding social capital; “Interacting with people gives me new people to talk to” and “I come in contact with new people all the time” for bridging social capital) composed the final measurement of social capital in this study. Participants evaluated these statements using a 5-point scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree).

Loneliness

An 8-item version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) (Wu & Yao, 2008) was used to measure participants’ loneliness. Participants picked a number on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 =never to 5 = always) to express how often they thought about each item on a day-to-day basis (e.g., “I lack companionship”, “People are around me but not with me”).

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) was used to estimate life satisfaction. Participants responded to items such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Well-being

The 14-item Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) was used to measure subjective well-being (Tennant et al., 2007).1 Participants chose a number on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) to show how often in the last 2 weeks they felt the same way as the items described (for instance, “I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future”).

Demographics

Sex, age, and place of residence were collected to ensure that our sample fit the proportions we set previously. Sex and age are also used as covariates in this study for all analyses.

Results

Emergent social grooming styles in this sample

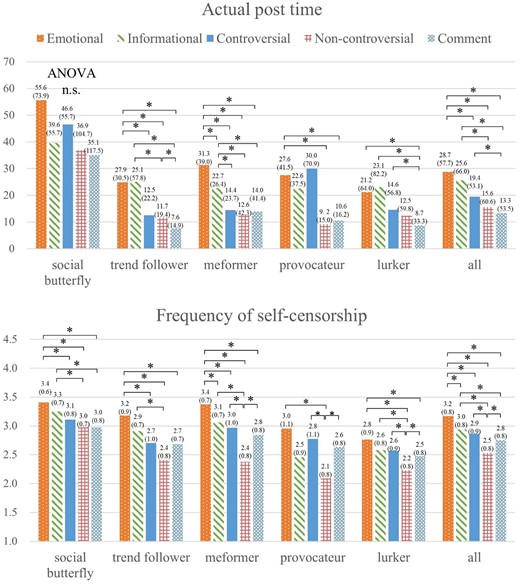

To identify the emergent social grooming styles based on the original model of five social grooming behaviors (Lin, 2019), we ran a latent class analysis on the frequency (four points were categorized into low or high following Lin’s procedure) of these posts (emotional, informational, controversial, non-controversial, comments on posts). Five classes emerged (AIC = 5,166.01; BIC = 5,308.37; G2(5) = 4.69; χ2(5) = 5.14), but there were a few differences from Lin’s (2019) results. Although we once again saw three of the five classes from Lin (2019), which are the social butterfly (13.8%), who engages in every social grooming behavior highly, the trend follower or life sharer (15%), who primarily shares their life while including some trend-following content, and the lurker (47.4%), who never engages in any of the social grooming behaviors, two new classes appeared as well. The first new class is the provocateur (4.9%), who almost exclusively posts about controversial issues. The second new class is the “meformer” (19.0%), who posts almost exclusively about emotional and personal topics, rarely talks about controversial issues, and comments on others’ posts frequently. These five classes (Figure 2) may reflect the changing landscape of usage styles on social media and were used as the basis for the rest of our analyses.

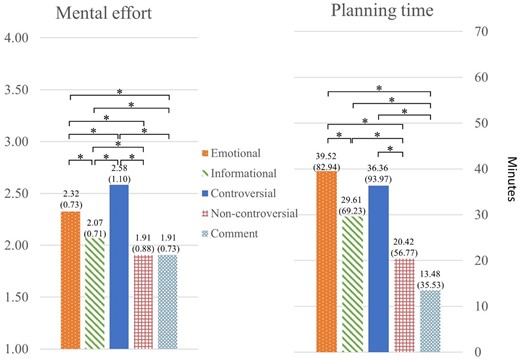

Breaking down costs

Our first hypothesis and RQ focused on effort-based costs, which are planning post time and mental effort. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA and post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction were conducted to examine the differences between the five grooming behaviors (Figure 3 with Ms and SDs). Since the assumption of sphericity was violated and the Greenhouse–Geisser ε was greater than 0.75, the Huynh–Feldt correction was adopted (Field, 2017). Results showed a significant effect of grooming behaviors on planning time (F(3.24, 3242.26) = 37.62, p < .001, ω2 = 0.33) and mental effort (F(3.23, 3232.06) = 195.41, p < .001, ω2 = 0.82). Post hoc analyses indicated that participants spend more mental effort (M = 2.32) and more time on planning (M = 39.52) emotional posts comparaed to informational posts (M = 25.56, p < .001 for planning time; M = 2.07, p < .001 for mental effort); thus, H1a was supported. Similarly, planning time (M = 36.36) and mental effort (M = 2.58) for controversial posts were higher than for non-controversial posts (planning time M = 20.42, p < .001; mental effort M = 1.91, p < .001), supporting H1b. Regarding H1c, planning time and mental effort for comments to others (M = 13.48 and M = 1.91, respectively) were significantly lower than for other grooming behaviors, except for non-controversial posts (all ps < .001); H1c was supported as well. As for RQ1, the planning time for emotional posts and controversial posts was not significantly different (p = 1.00); however, the participants reported spending more mental effort on controversial posts (p < .001).

Response of overall users on mental effort and planning time for each grooming behavior.

Note. Bar means and SDs enclosed in the parentheses are shown above the bars.

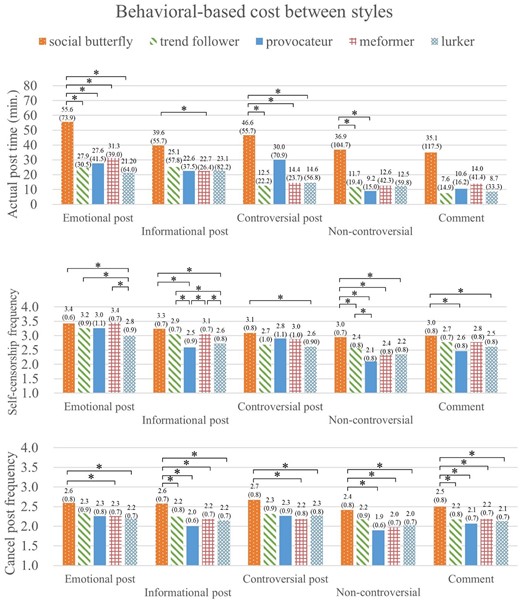

To answer RQ2 regarding behavioral-based costs, we conducted one way repeated-measures ANOVAs for each social grooming style on (a) actual post time, (b) frequency of content censoring, and (c) frequency of canceling the posts. More details regarding ANOVA tables and post-hoc comparisons can be found in Part B of the Supplementary Material. Except for the actual post times of social butterflies and the frequency of canceling posts among the meformers, trend followers, and provocateurs, all of the ANOVAs showed significant main effects of grooming behaviors on behavior-based costs. Results of post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction are summarized in Figure 4 with Ms and SDs. Emotional disclosure is the most time-costly social grooming behavior, especially for trend followers and meformers. They also tend to spend more time on informational/life posts than controversial posts, non-controversial posts, and comments. When it comes to the frequency of self-censorship, emotional self-disclosure is the most frequently self-censored social grooming behavior for social butterflies, trend followers, and meformers. For provocateurs and lurkers, although emotional self-disclosure is relatively self-censored, the frequency was only significantly higher than one or two of the other grooming behaviors. Apart from emotional self-disclosure, people tend to self-censor informational self-disclosure as well. Non-controversial posts are the least frequently self-censored for meformers, provocateurs, and lurkers, and the same pattern emerged for social butterflies and trend followers. Results indicated that the frequency of canceling posts is not significantly different between social grooming behaviors, except for lurkers, who cancel non-controversial posts significantly less.

Actual post time and frequency of self-censorship across and within each grooming style.

Note. Bar means and SDs enclosed in the parentheses are shown above the bars.

*p < .05

We also compared the behavioral-based costs of each social grooming behavior across the social grooming styles by one-way independent ANOVA with Games–Howell post hoc comparison (Figure 5). Social butterflies reported greater actual post time regarding emotional post than other four groups, greater time of informational post and controversial posts than meformers. Social butterflies also reported greater frequencies of censorship of non-controversial issues than meformers, and greater canceling behaviors of all five types of posts and comments than meformers. Social butterflies spent more invested costs than meformers.

Comparisons between grooming styles on behavioral-based costs.

Note. Bar means and SDs enclosed in the parentheses are shown above the bars.

*p < .05

Image awareness

To explore how image awareness is perceived across the social grooming styles (RQ3) and within every social grooming style (RQ4), we ran another series of repeated-measures ANOVAs (Figure 6). We found a significant effect of grooming behaviors (i.e., post type) on image awareness (F(3.28, 3283.94) = 129.9, p < .001, ω2 = .54) for the entire sample with Huynh–Feldt correction; emotional posts (M = 2.84) made posters most aware of their public image across social contexts (all ps < .05 in every pairwise comparison), followed by controversial posts (M = 2.73, significantly higher than informational posts, non-controversial posts, and comments, all ps < .001), informational posts (M = 2.57, significantly higher than non-controversial posts, p < .001), comments (M = 2.52), significantly higher than non-controversial posts, (p < .001), and non-controversial posts (M = 2.28).

Image awareness for each social grooming behavior for each grooming style and overall users.

Note. Bar means and SDs enclosed in the parentheses are shown above the bars.

*p < .05

The data were split into five grooming styles to take a closer look at the image awareness associated with each post type in each grooming style (Figure 6). For social butterflies, image awareness is the highest for emotional posts (M = 3.15) and tends to be the lowest for non-controversial posts (M = 2.87); there were no significant differences between informational posts (M = 3.03), controversial posts (M = 3.05) and comments (M = 2.98). For trend followers, image awareness of emotional posts is the highest (M = 3.06, significantly higher than informational posts, non-controversial, and comments), followed by controversial posts (M = 2.94, significantly higher than non-controversial and comments), informational posts (M = 2.79), comments (M = 2.65), and non-controversial posts (M = 2.44). Meformers are aware of their image most on emotional posts (M = 2.79) and least on non-controversial posts (M = 2.04), with awareness of the other three post types falling in the middle. The pattern of provocateurs is slightly different from other styles. Although emotional posts are still the highest on image awareness score (M = 2.84), the second highest appears to be comments (M = 2.55); the rest are controversial (M = 2.39), informational posts (M = 2.24), and non-controversial posts (M = 2.10). For lurkers, the image awareness scores of emotional (M = 2.70) and controversial posts (M = 2.70) are highest; the next are informational posts (M = 2.41) and comments (M = 2.36), and the score of non-controversial posts is the lowest (M = 2.18).

Frequency of adjusting privacy settings

RQ5 and RQ6 explore how often users adjust their privacy settings, considering both overall users and users conforming to each social grooming style. Because users are not allowed to adjust privacy settings for comments, only four social grooming posts are included in the analysis. As for RQ5 and RQ6, a series of one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted. Since all of the ANOVAs reached the significance criteria (F(2.83, 957.35) = 44.64 for the overall sample; F(2.66, 306.38) = 6.98 for social butterflies; F(3, 126) = 5.12 for trend followers; F(2.66, 169.93) = 24.42 for meformers; F(3, 57) = 3.20 for provocateurs; F(2.63, 247.13) = 12.24 for lurkers, all ps < .05), post hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction were conducted to understand the nuances of different grooming behaviors. As Figure 7 shows, overall, users reported more frequently adjusting privacy settings for emotional posts (M = 2.97) and informational posts (M = 2.94) than for controversial posts (M = 2.69, ps < .001) and non-controversial posts (M = 2.52, ps <.001). The frequency of adjusting the privacy settings for controversial posts is also significantly greater than for non-controversial posts, p <.01.

Frequency of adjusting privacy settings for different posts across and within each grooming type.

Note. Bar means and SDs enclosed in the parentheses are shown above the bars.

*p < .05

Social butterflies adjust emotional (M = 3.26) and informational posts (M = 3.24) more frequently than non-controversial posts (M = 2.97), with no difference between controversial posts (M = 3.07) and any other posts. Trend followers adjust emotional (M = 3.07) and informational posts (M = 3.00) more frequently than non-controversial posts (M = 2.58), and adjust emotional posts more than controversial posts (M = 2.67). For meformers, the frequency of adjusting privacy settings is higher for emotional (M = 3.00) and informational posts (M = 3.06) than for controversial (M = 2.62) and non-controversial posts (M = 2.26). Provocateurs only adjust privacy settings more often for emotional posts (M = 2.80) than for non-controversial posts (M = 2.15). Similar to meformers, lurkers adjust the privacy settings more often for emotional (M = 2.60) and informational posts (M = 2.56) than controversial (M = 2.33) and non-controversial posts (M = 2.21).

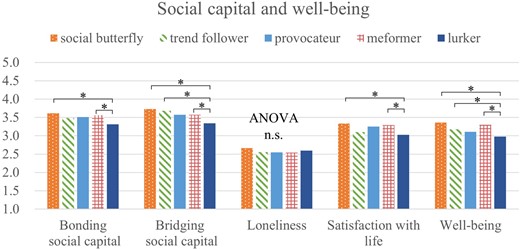

The benefits of social grooming styles

RQ7 explored which of the five social grooming styles is or are associated with positive outcomes for users. We ran a series of one-way independent ANOVAs with Games–Howell post hoc or Hochberg’s GT2 comparison due to the heteroscedasticity or inequality of sample size between groups on many variables (Field, 2017). For bonding capital, we found a significant effect of social grooming style (Welch’s F(4, 250.54) = 6.71, p < .001, ω2 = .02). Post hoc effects are shown in Figure 8, with social butterflies (M = 3.61) and meformers (M = 3.56) obtaining more bonding social capital than lurkers (M = 3.32), ps < .01. No significant differences were found between social butterflies, provocateurs (M = 3.51), trend-followers (M = 3.49), and meformers. We found another significant effect for bridging social capital (F(4, 996) = 17.55, p < .001, ω2 = .06), with social butterflies (M = 3.73), trend-followers (M = 3.68), and meformers (M = 3.58) gaining more than lurkers (M = 3.34), all ps < .001. For satisfaction with life (F(4, 996) = 6.56, p < .001, ω2 = .02), social butterflies (M = 3.34) and meformers (M = 3.29) reported more satisfaction with life than lurkers (M = 3.03), ps < .01. For well-being (F(4, 996) = 13.37, p < .001, ω2 = .05), social butterflies (M = 3.36), meformers (M = 3.30) and trend-followers (M = 3.18) reported significantly higher well-being than lurkers (M = 2.98, all ps < .05). No comparison related to provocateurs (M = 3.11) was significant (all ps > .20). There were no significant effects for loneliness, F(4, 996) = 1.10, p = .35, ω2 = .00. In sum, lurkers received the worst results across all psychological outcomes, and social butterflies and meformers received the best.

Comparisons of social capital and well-being between grooming styles.

Note. Bar means and SDs enclosed in the parentheses are shown above the bars.

*p < .05

Discussion

The SGM categorizes the types of content social media users post in order to interact with others and has received support from both cross-sectional (Lin, 2019) and longitudinal examinations (Lin & Hsieh, 2021). In this study, we validated the theorized “costs” in the original SGM, using time/effort and privacy dimensions, while examining the model’s robustness with image awareness.

From the mental planning effort, to actual composing, to censoring and canceling the post, to adjusting the privacy settings, we fully examined how people with different social grooming styles perceived these costs during all stages of posting the content on social media. The results supported the theoretical model of social grooming: that discussing private topics (including emotional and informational disclosure) has greater costs than discussing public topics (mainly controversial and trending topics) or simply commenting on others’ posts. Additionally, emotional posts led to the greatest costs among all the social grooming behaviors, as the planning time of the composition is high, mental effort is high, and they require users to self-censor the content and to manage privacy settings. Controversial posts also required a significant amount of actual and planned post time, as well as high mental effort. Personal topics, including emotional and informational posts, required more adjustments to privacy settings than public posts. Using these indicators from planning a post to actually posting a post, we provided empirical evidence to support the idea that discussing private topics leads to greater costs than discussing public topics, and, within private and public topics, emotional posts and controversial posts have greater costs than informational and trending posts. Overall, emotional posts require the greatest effort, and commenting requires the least effort among all five social grooming behaviors.

Through the lens of these costs, we also explored how different styles of social groomers execute these costs. We found that all social grooming styles incured higher costs from emotional posts compared to other types of posts, even for the more socially active groups, such as social butterflies and meformers. Private topics require meformers and social butterflies to be more cautious about their online image when constructing such content on Facebook. These findings contribute insights to the existing literature (Vitak et al., 2015) and further demonstrate that highly engaged users need more time and effort to balance their audience’s expectations and their own concerns (Litt & Hargittai, 2016; Schlosser, 2020) by strategically crafting content (Hogan, 2010) and exposing it within a controlled context (Loh & Walsh, 2021) through privacy management strategies (Chen, 2018).

This is consistent with several sets of literatures within the realm of social media scholarship, notably context collapse (e.g., Davis & Jurgenson, 2014) and imagined audience (e.g., Litt & Hargittai, 2016). These literatures deal with the people seeing the posts and comments, but from slightly different angles. In context collapse, all of the audiences that exist in the real world are combined into a single audience: the social media network (Loh & Walsh, 2021). Imagined audiences refer to the imagined feedback that a person will receive about their posts and/or comments from the various audiences present in the collapsed context (Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021). By adjusting the privacy settings on different posts and comments, a person is actually able to separate out the various contexts that are normally collapsed, allowing for a unique self-presentation for each (see Djafarova & Trofimenko, 2019). By adjusting privacy settings, people can self-disclose to those they are close to and self-present to colleagues or strangers (Schlosser, 2020). In this way, they can effectively reduce the associated costs of emotional or controversial posts.

Provocateurs, who only post about controversial topics and invest relatively high costs, are a newly emerged social grooming style in this study. Facebook has become a place for them to gain influence regarding certain topics, so they have to carefully craft their content to be persuasive and influential (Hogan, 2010). It would seem that the provocateur style is actually a meticulous self-presentation practice (see Hollenbaugh, 2021) in which the user styles themselves as an expert on certain controversial issues, or at the very least makes an effort to take a public stance on the social issues of the day. This identity goal is carefully presented to the collapsed context of social media (Hollenbaugh, 2021), creating the provocateur.

The meformer is another newly identified social grooming style; these users heavily share their own private information (i.e., emotional and informational posts), and on occasion they mention controversial topics. Costs are relatively low for meformers compared to social butterflies, allowing for quicker content creation. As opposed to the careful self-presentation of the provocateur (Hollenbaugh, 2021) and social butterflies who spent lots of costs in all their posts, the meformer appears to opt for a pure self-disclosure approach with little to no pretense, irrespective of audience (Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021). Social media is their diary, while social media is the provocateur’s soapbox.

We explored how much each social grooming style user was aware of their image to others after posting about certain topics. Image awareness focuses on how people are aware of how other people think of them based on the content they post; in other words, image awareness describes how users conceptualize their reputational concerns vis-à-vis each of the social groups comprising their collapsed social media context. As this awareness is key to influencing users’ self-presentation and imagined audience (Hogan, 2010), understanding how each style perceives their image awareness regarding different posts is important. The results indicated that emotional disclosure and controversial topics are the types of posts that require a greater degree of image awareness than other types of posts. Lurkers, who did not post anything on Facebook, also reported similar image awareness concerns regarding each type of social grooming post. Even provocateurs, who only posted controversial topics on Facebook, reported significantly greater concern about image awareness for emotional posts than for controversial posts. Posting controversial posts requires fewer costs than emotional posts for provocateurs, consistent with the idea that provocateurs are carefully self-presenting (Hollenbaugh, 2021). Social grooming style practices are therefore a negotiation between personal social goals and image costs, and their interaction with image awareness is key for content variability, complementing existing literature (Hollenbaugh, 2021; Schlosser, 2020).

This study showed that the SGM can reflect various social grooming styles among different samples and at different times. Because of the above, new styles were identified in this study. First, all five social grooming styles reported means above 3, the middle value on a 5-point scale, indicating that all users reported relatively high social benefits. Social butterflies and meformers reported the best social benefits, including greater bonding and bridging social capital, social life satisfaction, and well-being than lurkers. These are consistent with previous literature (Lin, 2019; Lin & Hsieh, 2021), and also indicate that higher social activity is correlated with greater social benefits like well-being (Dhir et al., 2018; O’Reilly et al., 2018). Meanwhile, trend followers gained bridging social capital and greater well-being than lurkers because they share trends to experience belongingness with others. Although provocateurs did not report significantly greater social benefits than other styles, they employed Facebook as a way to gain influence, while lurkers seemed to choose passive consumption. The new patterns in this study reflect the rich styles people use to engage in social media and report varying social benefits.

The model and results demonstrate that outcomes associated with social media use may depend more on it may be more about how people engage with social media rather than simple engagement alone. The present results would suggest that those who use social media in a more varied way are more satisfied with their lives and experience higher levels of well-being. Of course, due to the methodology employed in the present work, we cannot determine whether it is the style of social grooming that leads to these positive outcomes or whether those who are generally more satisfied with their lives and are feeling good use social media in this way; future experimental and/or longitudinal work is required to untangle that relationship.

Some nuances exist between social butterflies and meformers. Although these two styles receive the same social benefits, social butterflies reported greater costs, including time, censoring, and canceling the posts, than meformers. This showed that the more socially active users (i.e., social butterflies) not only gain social benefits but also invest greater costs than others. Meformers are a type of user who engages in strategic social grooming with others and receive similar social benefits to social butterflies while incurring lower costs. This consistency aligns with the notion that strategically engaging in social grooming may be the most efficient approach among various social grooming styles (Lin, 2019; Lin & Hsieh, 2021).

Limitations and contributions

Some limitations require attention when interpreting the results. First, all the participants were recruited online through Nielson, possibly introducing a bias in the sample. The new styles of provocateur and meformer may be an artifact of this sampling of highly engaged internet users. Second, the construct of image awareness was newly developed in this study. Though it had good reliability, its robustness should be examined further in future studies, particularly in different cultural contexts or among different age groups. Third, we operationalized costs using a very detailed approach, but using self-report data may not capture an accurate reflection of each of the social grooming behaviors. Nonetheless, our data showed variances among these social grooming behaviors, and it corresponds with our theorized predictions. Fourth, some behaviors were measured using single items, which could be further explored with more developed scales.