-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pengfei Zhao, Natalie N Bazarova, Dominic DiFranzo, Winice Hui, René F Kizilcec, Drew Margolin, Standing up to problematic content on social media: which objection strategies draw the audience’s approval?, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 29, Issue 1, January 2024, zmad046, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad046

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Problematic content on social media can be countered through objections raised by other community members. While intended to deter offenses, objections can influence the surrounding audience observing the interaction, leading to their collective approval or disapproval. The results of an experiment manipulating seven types of objections against common types of offenses indicate audiences’ support for objections that implore via appeals and disapproval of objections that threaten the offender, as they view the former as more moral, appropriate, and effective compared to the latter. Furthermore, audiences tend to prefer more benign and less threatening objections regardless of the offense severity (following the principle of “taking the high road”) instead of objections proportionate to the offense (“an eye for an eye”). Taken together, these results show how objections to offensive behaviors may impact collective perceptions on social media, paving the way for interventions to foster effective objection strategies in social media discussions.

Lay Summary

Problematic content that involves misleading information or contains offensive language is prevalent on social media. Other users can confront it by objecting to this content, but the effectiveness of different objection strategies is not well understood. We conducted a randomized controlled experiment in a simulated social media environment to investigate how audiences interpret (e.g., as appropriate, justified, and persuasive) and react to them (e.g., intentions to upvote and downvote). The results indicate that audiences approve objections that appeal to consciousness, as they are viewed as more appropriate, justified, and effective; conversely, objections that undermine the offender’s reputation or imply physical threats are most likely to be downvoted because they are judged as morally questionable. Furthermore, audiences prefer more benign and less threatening objections, even when encountering severe offenses. These findings shed light on what objections—even as all of them call out offensive content—find favor in audiences’ eyes, which can be leveraged for interventions and trainings in how to counter offenses on social media.

While objectionable speech, including misinformation, hate speech, and harassment, is prevalent on social media, it is often contended and confronted by other community members (Bode & Vraga, 2018; Crockett, 2017). We refer to these confrontations as objections, which are speech acts (Wierzbicka, 1987) that call out objectionable content, or offenses, as inappropriate. As captured by the prosocial adage “if you see something, say something,” the offense is what an individual “sees” and identifies as wrong, while the objection is what they “say” in response.

While there are many different types of objection strategies (e.g., Cai & Wohn, 2019), they may vary in their impact and the intended effect (e.g., Álvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018; Crockett, 2017). To begin with, understanding the impacts of objections is complicated by the fact that there are at least three potential targets that could be intentionally or unintentionally influenced by an objection—the offender (author of the offense), the objector themselves, and the surrounding audience observing the interaction. Second, an objection could have many different potential goals, such as obtaining a specific response (e.g., a retraction or apology) from the offender, changing norms in the conversation, provoking a collective response (e.g., approval or further comment from other members of the audience), or even satisfying a need to express feelings (e.g., outrage) by the objector (e.g., Álvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018; Crockett, 2017; Fiesler & Bruckman, 2019). Furthermore, objections, even if motivated by a prosocial desire to correct the offense, may at times become part of the problem by making threats and using abusive language, perpetuating a cycle of divisive, offensive, or hateful speech (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2018; Shmargad et al., 2022).

This study focuses on the impact of objections on the onlooking audiences because of their potential role in establishing or maintaining social norms (Álvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018; Wenzel et al., 2008). That is, objections that rally the audience to the objector’s side should impact the perceived appropriateness of offenses and ongoing behaviors in online spaces differently compared to those that fail to engage the audience or perhaps even drive the audience to defend the offender (e.g., Lee et al., 2022; Mathew, 2017). Previous research has compared the effects of verbal sanction with other content moderation approaches (e.g., algorithm correction and content removal) in correcting misperceptions and reducing offenses (e.g., Álvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018; Bode & Vraga, 2018), examined the consequences of different types of flags for online offenses (e.g., Garrett & Poulsen, 2019), and investigated how contextual factors (e.g., norms and information sources) may impact the use and effects of objections (e.g., Vraga & Bode, 2017). However, no study has compared different types of discursive objection strategies vis-à-vis each other across various kinds of online offenses from the perspective of on-looking audiences. To address this gap, we conducted an experiment on a simulated social media platform to examine the impact of different types of objections on the perceptions and behavioral intentions of an on-looking audience, specifically their moral, emotional, and attitudinal reactions, and finally, how these reactions predict audience’s behavioral responses toward objections.

Regulation of online offenses

In the online context, offensive speech violates normative expectations of communication, such as politeness, mutual respect, and information quality (Bormann et al., 2022). Though objections may target a specific offensive statement, the criticism of the offense is implied as a rule to other similar behaviors within that community (e.g., Álvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018). For these rules to apply to everyone in the community, they must be established and transmitted to others as social norms (Elster, 1989).

Social norms are “mental representations of appropriate behavior in society or smaller groups and, consequently, guide the behaviors of individuals” (Rost et al., 2016, p. 2), which are sustained through the community’s approval and disapproval (Elster, 1989). In offline communities, norms are often long established through culture and practice (Gavrilets & Richerson, 2017), but in online communities, such sharedness cannot be taken for granted (Marwick, 2021). Although individuals may agree on norms in principle (e.g., that incivility is bad), they may disagree about what constitutes a norm violation (Liang & Zhang, 2021). Individuals may also change their judgments over time, for example, becoming de-sensitized to violations after repeated exposures (Crockett, 2017). Despite the fact that the presence of or agreement on norms is not a guarantee, individuals appear to try to establish, maintain, and/or enforce the norms they support (Rost et al., 2016; Marwick, 2021). In particular, when explicit rules or top-down approaches for regulating online offenses are inapplicable or ineffective (e.g., official content removal and user bans), users themselves often take an informal, or bottom-up, approach, including objecting to an offense, to shape and maintain social norms regarding what ought and ought not to be said (e.g., Cai & Wohn, 2019; Matias, 2019; Marwick, 2021).

There are broadly three mechanisms through which a norm can be created or maintained without support from formal authority (e.g., Fiesler & Bruckman, 2019). One is through direct punishments or sanctions, that is, the penalty or social consequences for violating the norm imposed by the community (Fiesler & Bruckman, 2019). Punishment works via the mechanism of self-interest, as individuals bear a personal cost when they fail to comply (Boyd & Richerson, 1992; Gavrilets & Richerson, 2017). In the online context, punishing the offender can take the form of “public shaming,” “threatening,” or “retributive harassment;” that is, the offender is publicly criticized or even harassed or threatened by other users because of moral violations (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2018). For example, social media users may deride and criticize the conduct of politicians or celebrities for being inappropriate.

The second mechanism for maintaining community norms is through norm internalization and moral persuasion (Gavrilets & Richerson, 2017). When a norm is internalized, people act according to it even when there is no threat of external sanction or explicit norm enforcement (Gavrilets & Richerson, 2017). Rather, they see the norm as having moral value and may anticipate internal responses, such as feelings of guilt, if they violate it (Roberts et al., 2014). The process of instilling norms and rules may involve moral persuasion that relies on appealing to moral principles, such as equality, reciprocity, or civility, aiming to shape the offender’s perception of right and wrong and facilitate a change in their future behaviors (Hunter, 1974; Guadagno & Cialdini, 2009). In online communities, one example of maintaining norms via internalization mechanisms is through “gentle reminders” from other community members who remind each other about appropriate behaviors or justify compliance morally (e.g., Fiesler & Bruckman, 2019).

The third mechanism is through the preservation of group boundaries. When there is disagreement or controversy over norms in a community, one way to maintain normative order is for the group to split (Stanish, 2017). Unlike the other approaches which target the behavior of a violator, preservation targets the violator’s membership. For example, on Reddit, members can create separate online spaces for different kinds of talk on similar topics that follow different social norms (Matias, 2019). People may also ostracize those who violate group norms from the online community to maintain norm integrity (Fiesler & Bruckman, 2019).

As the logic of these mechanisms indicates, the response of the surrounding community plays an important role in supporting the normative aims of an objection (Elster, 1989; Mathew, 2017). One individual can assert that a statement is an offense, but if others do not agree, or are indifferent, the norm may not be formed or enforced (e.g., Lee et al., 2022). Previous research has shown that collective approval and disapproval of retributive harassment on social media, as signaled by the number of Likes and Dislikes from the audience, can shape social norms and further influence community members’ judgment about that harassment (Lee et al., 2022). Therefore, to identify and develop effective objections aimed at fostering norms that are intolerant of problematic content on social media, it is necessary to understand how and why different types of objections can lead to collective approval or disapproval.

Objections and the on-looking audience on social media

Objections on social media

Based on the three mechanisms for norm enforcement and maintenance in the online context—punishment, internalization and moral persuasion, and preservation, Shea et al. (2023) identified seven common strategies that people use to object to offenses on social media. These strategies were developed through an iterative analysis of several thousand replies observed on highly viewed YouTube news videos and controversial topics on Twitter. The development of the objection classification was a two-phased process: The first phase employed a rigorous six-step method, encompassing sampling, coding, preliminary codebook development, internal testing, reliability checks, and finalizing the codebook. The second phase involved Amazon’s Mechanical Turk crowdworkers to validate the codebook. For further explanation of these two phases and the objection taxonomy identification, please refer to the Supplementary Materials based on Shea et al. (2023). In our study, we use real-world examples from the aforementioned comment corpus to help us identify realistic language for articulating objections that aligns with the three identified theoretical principles. Therefore, these objection strategies are grounded in theoretically driven concepts and substantiated by real-world observations.

Two strategies lie in the punishment/threatening category: threatening via reputational attacks or “face threats” (Cupach & Metts, 1994) and threatening via violent warnings; two strategies belong to the internalization category: imploring via appeals to conscience (i.e., what is morally right or wrong) and imploring via appeals to logic (i.e., what is consistent with proper principles of inference). Two strategies lie in the preservation category: preserving through group maintenance, in which offenders are encouraged to leave the group space, and preserving through personal abstinence, in which objectors declare that they will leave the group space. The last strategy, dismissal-objectionable content, is the most basic type of objection that simply calls out inappropriate behavior without making any specific threat, appeal, or claim about the group. See Table 1 for definitions and examples of each objection strategy.

| Objection strategy . | Definition . | Operationalization examples . |

|---|---|---|

| Dismissal—Objectionable Content | The most basic element of all other objections signaling the content should be objected | “This is false!” “This is harassment!” “That’s racist!” |

| Imploring—Conscientious Appeal | Comments that appeal to ethical and moral principles of conduct | “This is false! You should feel better about getting it but still need to get doctor input based on your history. It is also still your choice. Hope and pray for everyone to see the light and do the right things for everyone, not just themselves.” |

| Imploring—Logical Appeal | Comments that appeal to principles of reasoned argument | “This is false! There's really little downside to getting the vaccine, at any rate. We have vaccines just sitting on shelves because anti-vaxxers refuse to take them and follow the science in the first place. CDC scientists are looking at risk/reward ratios, not pragmatic policy. And by that, I mean risk being almost nil, not that vaccines are risky in any way.” |

| Threatening—Reputational Attack | Comments that seek to undermine the authority or reputation of the offender | “This is harassment! I can’t even tell you to ‘do some research’ cuz you’ve been brainwashed to think that is dumb as sh! t too.” |

| Threatening—Violent Warning | Comments that directly state or imply violence toward the offender | “This is harassment! You should be hanged!” |

| Preserving—Group Maintenance | Comments that direct the offender to leave the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform, or to delete their comment(s) | “That’s racist! You should just delete your comment.” |

| Preserving—Personal Abstinence | Comments that signal one’s own (the objector) departure from the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform | “That’s racist! I am done with you.” |

| Objection strategy . | Definition . | Operationalization examples . |

|---|---|---|

| Dismissal—Objectionable Content | The most basic element of all other objections signaling the content should be objected | “This is false!” “This is harassment!” “That’s racist!” |

| Imploring—Conscientious Appeal | Comments that appeal to ethical and moral principles of conduct | “This is false! You should feel better about getting it but still need to get doctor input based on your history. It is also still your choice. Hope and pray for everyone to see the light and do the right things for everyone, not just themselves.” |

| Imploring—Logical Appeal | Comments that appeal to principles of reasoned argument | “This is false! There's really little downside to getting the vaccine, at any rate. We have vaccines just sitting on shelves because anti-vaxxers refuse to take them and follow the science in the first place. CDC scientists are looking at risk/reward ratios, not pragmatic policy. And by that, I mean risk being almost nil, not that vaccines are risky in any way.” |

| Threatening—Reputational Attack | Comments that seek to undermine the authority or reputation of the offender | “This is harassment! I can’t even tell you to ‘do some research’ cuz you’ve been brainwashed to think that is dumb as sh! t too.” |

| Threatening—Violent Warning | Comments that directly state or imply violence toward the offender | “This is harassment! You should be hanged!” |

| Preserving—Group Maintenance | Comments that direct the offender to leave the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform, or to delete their comment(s) | “That’s racist! You should just delete your comment.” |

| Preserving—Personal Abstinence | Comments that signal one’s own (the objector) departure from the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform | “That’s racist! I am done with you.” |

Note: The objection strategy classifications and definitions are based on Shea et al. (2023).

| Objection strategy . | Definition . | Operationalization examples . |

|---|---|---|

| Dismissal—Objectionable Content | The most basic element of all other objections signaling the content should be objected | “This is false!” “This is harassment!” “That’s racist!” |

| Imploring—Conscientious Appeal | Comments that appeal to ethical and moral principles of conduct | “This is false! You should feel better about getting it but still need to get doctor input based on your history. It is also still your choice. Hope and pray for everyone to see the light and do the right things for everyone, not just themselves.” |

| Imploring—Logical Appeal | Comments that appeal to principles of reasoned argument | “This is false! There's really little downside to getting the vaccine, at any rate. We have vaccines just sitting on shelves because anti-vaxxers refuse to take them and follow the science in the first place. CDC scientists are looking at risk/reward ratios, not pragmatic policy. And by that, I mean risk being almost nil, not that vaccines are risky in any way.” |

| Threatening—Reputational Attack | Comments that seek to undermine the authority or reputation of the offender | “This is harassment! I can’t even tell you to ‘do some research’ cuz you’ve been brainwashed to think that is dumb as sh! t too.” |

| Threatening—Violent Warning | Comments that directly state or imply violence toward the offender | “This is harassment! You should be hanged!” |

| Preserving—Group Maintenance | Comments that direct the offender to leave the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform, or to delete their comment(s) | “That’s racist! You should just delete your comment.” |

| Preserving—Personal Abstinence | Comments that signal one’s own (the objector) departure from the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform | “That’s racist! I am done with you.” |

| Objection strategy . | Definition . | Operationalization examples . |

|---|---|---|

| Dismissal—Objectionable Content | The most basic element of all other objections signaling the content should be objected | “This is false!” “This is harassment!” “That’s racist!” |

| Imploring—Conscientious Appeal | Comments that appeal to ethical and moral principles of conduct | “This is false! You should feel better about getting it but still need to get doctor input based on your history. It is also still your choice. Hope and pray for everyone to see the light and do the right things for everyone, not just themselves.” |

| Imploring—Logical Appeal | Comments that appeal to principles of reasoned argument | “This is false! There's really little downside to getting the vaccine, at any rate. We have vaccines just sitting on shelves because anti-vaxxers refuse to take them and follow the science in the first place. CDC scientists are looking at risk/reward ratios, not pragmatic policy. And by that, I mean risk being almost nil, not that vaccines are risky in any way.” |

| Threatening—Reputational Attack | Comments that seek to undermine the authority or reputation of the offender | “This is harassment! I can’t even tell you to ‘do some research’ cuz you’ve been brainwashed to think that is dumb as sh! t too.” |

| Threatening—Violent Warning | Comments that directly state or imply violence toward the offender | “This is harassment! You should be hanged!” |

| Preserving—Group Maintenance | Comments that direct the offender to leave the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform, or to delete their comment(s) | “That’s racist! You should just delete your comment.” |

| Preserving—Personal Abstinence | Comments that signal one’s own (the objector) departure from the one-on-one interaction, comment thread, or platform | “That’s racist! I am done with you.” |

Note: The objection strategy classifications and definitions are based on Shea et al. (2023).

There has been substantial research to date on under what conditions people engage in objections and similar “upstanding” behaviors (e.g., Bastiaensens et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2019). The literature on bystander involvement indicates that social media users are more likely to engage in objections to offenses when they are held accountable, empathize with the victim, consider the inappropriate behavior as severe, and believe their actions are socially transparent and effective (Bastiaensens et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2019). In addition, the willingness to object is also shaped by perceived social norms; that is, individuals are more likely to call out inappropriate behaviors when these behaviors are considered more unacceptable (i.e., injunctive norms) and less prevalent (i.e., descriptive norms; Brauer & Chaurand, 2009). For example, on social media, repeated uncivil comments receive more upvotes, which may be less likely to be objected to, if nearby comments also include incivility (Shmargad et al., 2022).

Audience responses to objections

Although objections are morally motivated to deter inappropriate behaviors and build/maintain the integrity of norms (Carlsmith et al., 2002; Gavrilets & Richerson, 2017; Marwick, 2021), the specific objection strategies may trigger different audience reactions and, in some cases, even backfire. For example, while sanctioning offenders through public shaming approaches tends to draw audience support (Schoenebeck et al., 2021), sanctions that are viewed as motivated by malicious intent or as harassment itself can meet with resistance from other community members (e.g., Hornsey, 2005).

Appealing to internalized norms and moral values can be particularly effective if there is a common bond or group identity among community members (e.g., Hogg & Reid, 2006). In addition, explanations for how problematic content deviates from community norms are also found to be useful in reducing antisocial behaviors (e.g., Lewis & Yoshimura, 2017). In particular, when correcting misinformation, using logical explanations and reasoning can decrease misperception (Bode & Vraga, 2018), whereas mere peer-generated flagging does not reduce acceptance and sharing intention of misinformation (Garrett & Poulsen, 2019).

Although the above-mentioned research suggests distinct effects of different mechanisms for norm enforcement and maintenance, no study has compared their effects vis-à-vis each other, making it unknown how different types of objections influence the on-looking audience’s intention to engage in supportive and suppressive behaviors. Therefore, we pose:

RQ1: How do different types of objections influence the on-looking audience’s behavioral intentions (e.g., upvote, downvote, flag, share, and reply) toward the objection and the offense on social media?

Moral, emotional, and attitudinal responses

Although all types of objections can be morally motivated to deter inappropriate behaviors, they may differ in how the audience evaluates their morality (Gromet & Darley, 2009). Previous research has shown that certain justice responses to wrongdoings are considered more morally justified and deserved over others under certain conditions (Gromet & Darley, 2009). For example, punishing the offenders with imposing proportional harm (i.e., retributive justice) is considered more moral than restoring the harm for the victim and building value consensus (i.e., restorative justice) when the offense is severe and intentional (Gromet & Darley, 2009). Namely, if the justification for punishment is sufficient, it will be considered moral. Extending this pattern to the online context, Blackwell et al. (2018) found that individuals consider harassment, normally a moral violation, as justified and deserved if it is targeted at an individual who has committed a severe offense. Furthermore, the morality of the objection behaviors can shape the collective’s approval and disapproval of the offense and objection (e.g., Mathew, 2017). For example, when a sanction is considered appropriate and justified, people are more likely to disapprove of wrongdoing (Mathew, 2017). Together, the onlooking audience may have different moral judgments toward different objections, which can influence their approval and disapproval of the objector and offender.

In addition to perceived appropriateness and justifiability, moral emotions associated with moral violations also shape people’s behaviors. When people are exposed to moral violations or unfair treatment, their negative emotions, such as anger and disgust, will increase as expressions of their moral outrage (e.g., Molho et al., 2017). Disgust tends to prompt indirect attacks against offenders, such as reputational sabotage, while anger leads to direct aggression (e.g., physical and verbal confrontation) (Molho et al., 2017). Additionally, people feel guilt when they or their community members commit transgressions that violate moral principles and values (Carni et al., 2013). Feelings of guilt can be a mechanism to promote prosocial behaviors (Carni et al., 2013). Taken together, when the onlooking audience considers the objection to be inappropriate and unjustified, or a moral violation, they may experience moral indignation, anger, disgust, and guilt, which can, in turn, suppress their support for the objection. Because attitudes are also important in driving support for the behavior (Ajzen, 1991), we will examine audiences’ attitudinal responses, in addition to their moral and emotional reactions, toward objections:

RQ2: How do different types of objections influence the on-looking audience’s emotional, attitudinal, and moral responses on social media?

Based on the above reasoning, it can be expected that moral judgments shape people’s emotional and attitudinal responses to objections, subsequently shaping their behaviors. Central to this argument is that individuals’ moral or justice judgments serve as foundational evaluations of social situations, profoundly affecting their thoughts, feelings, and actions (e.g., Gromet & Darley, 2009; Tyler et al., 1997). Particularly, research has consistently shown that moral judgments influence emotional reactions, with individuals experiencing more negative feelings when confronted with immoral acts (e.g., Carni et al., 2013; Molho et al., 2017). Furthermore, perceived morality also shapes people’s attitudes, causing individuals to attitudinally favor actions deemed moral (e.g., Sparks & Shepherd, 2002). Importantly, both emotions and attitudes are well-established determinants of behavior (e.g., Ajzen, 1991; Sparks & Shepherd, 2002; Molho et al., 2017). Therefore, when people consider an objection as appropriate, justified, and deserved, they are likely to have positive emotions and attitudes, further leading to supportive behaviors toward the objection; conversely, when individuals consider an objection morally unfavorable, they tend to have negative emotions and attitudes, resulting in suppressive behaviors. Given this reasoning, we examine a possible serial mediation: objection → moral judgment → emotional & attitudinal responses → behavioral intentions:

H1: Different types of objections indirectly impact the on-looking audience’s behavioral intentions via the influence on moral judgment and subsequent emotional and attitudinal responses to the objection.1

Does offense matter?

For our study, we specifically focus on three types of problematic content commonly encountered on social media: misinformation (i.e., inaccurate or misleading information), harassment (i.e., abusive or offensive comments directed at a particular person), and hate speech (i.e., abusive or threatening speech that expresses prejudice against a particular group). Because people’s perceptions of morality and their emotions toward the objection may be tied to specific types of offense (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2018), we are also interested in whether the audience reacts to objections differently across offense types:

RQ3: Do the effects of different types of objections on moral, emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral responses vary by the kind of offense on social media?

An eye for an eye?

According to the retributive justice framework, the extent to which the punishment is proportional to the moral violation influences the audience’s moral judgments (Carlsmith et al., 2002; Walen, 2015). Specifically, it is assumed that justice is out of balance when individuals harm society by committing wrongs, and balance is restored when the offender is inflicted proportionate suffering (Carlsmith et al., 2002). As such, a response that is too harsh, such as an extreme punishment for a minor offense, can itself be an offense (Mathew, 2017). Conversely, a response that is too weak does not signal the importance of the norm, appearing to be “a slap on the wrist.” For example, failing to object strenuously to offending speech is often viewed as tacit “tolerance” and thus a normative violation. Thus, in this framework, it is important that the sanction “fit” the crime, which can also be described by the “an eye for an eye” metaphor (Carlsmith et al., 2002). Supporting this framework, research has shown that online harassment toward an offender can be considered justified and deserved while not appropriate (Blackwell et al., 2018). That said, there are also other principles of ethics and justice that can account for people’s perceptions of morality. For example, the restorative approach focuses on repairing harm and building a consensus of right and wrong by balancing the needs of the victim, wrongdoer, and community (Bazemore, 1998). In addition, the humanity perspective may emphasize following the action that is the most moral and least harmful even when opposed to offenses (e.g., empathy, forgiveness; e.g., Exline et al., 2003). However, because the retributive justice framework was widely supported and applied, we hypothesize:

H2: The closer the match between the severity of objections and offenses, the more favorable moral judgments of objections are.

Finally, given the potential effects of moral judgments on other types of responses, we propose the following research question regarding the mediating effect of moral judgments:

RQ4: Do moral judgments mediate the effects of the match between offenses and objections on emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral responses?

Method

To test the effects of different types of objections, this study built a simulated video-based social media platform, “VidShare,” which has a similar look and feel to YouTube. Participants were able to view a video and the related comments on VidShare, which were presumed to be generated by real users on the site but, in reality, predetermined by the researchers. The study design, hypotheses, and analysis plan were pre-registered on OSF.

Participants

Based on a power analysis (see our preregistration), we recruited 1,069 participants from CloudResearch, using a cover story that participants would be beta testing a new social media platform. This study took approximately eight minutes to complete, and participants were compensated $2 for completing the study. The sample comprised 464 females (43.41%), 599 males, and 6 people who identified as non-binary. The average age for participants is 41.89 (SD = 12.45). Most participants in the sample self-identified as White American (n = 854, 79.89%), followed by Black or African American (n = 95, 8.89%), Asian (n = 85, 7.95%), two or more races (n = 15, 1.40%), other (n = 9, 0.84%), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 8, 0.75%), and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (n = 3, 0.28%).

Experimental design

Participants were first asked to view a snapshot of VidShare that represented the condition they were randomly assigned to (see an example in Figure 1). The snapshot included a post containing a short video segment followed by comments and replies to them. As shown in Figure 1, the video content and comments were related to the approval of the Pfizer vaccine. After viewing the snapshot, they were asked to complete a series of questions about their emotions, perceptions, and behavioral intentions toward the offense and objection messages.

An example VidShare snapshot.

Note: Only offense and objection messages were manipulated for each condition.

This study employed a between-subject factorial design to test the effects of objections and offenses. Offense messages were direct comments on the vaccine news, and objection messages were replies to the offense. The three types of manipulated offenses were misinformation, hate speech, and harassment. The eight conditions for objections are seven types of objection (see Table 1) and one control condition without any objection. All stimuli messages were developed based on real-world observations (see Supplementary materials for specific message stimuli).

In addition to three types of offenses and eight objection types, to avoid conflation between the treatment and message effects, we had two messages for each objection type, which resulted in a final design of 3 (offense) × 8 (7 objection types + 1 control) × 2 objection messages. Participants were randomly assigned to one of these 48 conditions. The 24 groups of interest reflecting different offense-objection type combinations were tested for differences in age, gender, race, education, income, religion, political orientation, and social media use. There were no significant differences among them on any of these variables, demonstrating the efficacy of randomization.

In some cases, the two objection messages differed on some of the dependent variables, including moral judgment, attitudes, and message effectiveness (see Supplementary materials), but this variability was expected and factored into our models. Specifically, we pre-registered and conducted mixed-effects models with objection types as a fixed factor and objection messages as a random factor (see details below), under the assumption that objection messages were drawn from a normally distributed population of messages of a given objection type (e.g., Brown, 2021). Therefore, as specific objection messages representing a given objection type were expected to randomly vary from each other, we accounted for this variability by including objection messages as a random factor to obtain a more general estimate of the fixed effects of objection types.

Measures

Moral judgment

Adapting from Blackwell et al. (2018), we asked participants to report to what extent they considered the objection message as appropriate, justified, and deserved. These three items were measured on 7-point semantic differential scales. A composite was calculated by averaging the items, with a larger value indicating more favorable moral judgments (See Table 2 for reliability indexes for all dependent variables).

Means, standard deviations, alpha, and zero-order correlations for measured variables

| Variable . | Scale . | Mean . | SD . | Alpha . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Emotion | 0–10 | 5.44 | 2.35 | – | — | |||||||||

| 2. Negative Emotion | 0–10 | 3.31 | 2.77 | – | −.62** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Emotional Arousal | 0–10 | 3.48 | 2.49 | – | .12** | .13** | — | |||||||

| 4. Anger | 1–5 | 1.61 | 0.90 | – | −.41** | .47** | .23** | — | ||||||

| 5. Disgust | 1–5 | 1.71 | 1.01 | – | −.49** | .54** | .18** | .79** | — | |||||

| 6. Guilt | 1–5 | 1.12 | 0.46 | – | −.03 | .14** | .17** | .28** | .28** | — | ||||

| 7. Offense Severity | 1–7 | 5.55 | 1.48 | 0.89 | .10** | −.04 | .17** | .10** | .07* | −.02 | — | |||

| 8. Objection Severity | 1–7 | 2.91 | 1.57 | 0.89 | −.02 | .13** | .19** | .11** | .13** | .15** | .02 | — | ||

| 9. Objection Attitude | 1–7 | 4.35 | 2.05 | 0.97 | .19** | −.17** | .04 | .02 | −.07* | .03 | .36** | −.48** | — | |

| 10. Objection Effectiveness | 1–7 | 3.77 | 1.90 | 0.96 | .21** | −.13** | .14** | .05 | −.02 | .07* | .38** | −.28** | .78** | — |

| 11. Moral Judgment | 1–7 | 4.96 | 1.93 | 0.96 | .13** | −.15** | −.00 | −.00 | −.06 | .01 | .38** | −.55** | .84** | .75** |

| Variable . | Scale . | Mean . | SD . | Alpha . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Emotion | 0–10 | 5.44 | 2.35 | – | — | |||||||||

| 2. Negative Emotion | 0–10 | 3.31 | 2.77 | – | −.62** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Emotional Arousal | 0–10 | 3.48 | 2.49 | – | .12** | .13** | — | |||||||

| 4. Anger | 1–5 | 1.61 | 0.90 | – | −.41** | .47** | .23** | — | ||||||

| 5. Disgust | 1–5 | 1.71 | 1.01 | – | −.49** | .54** | .18** | .79** | — | |||||

| 6. Guilt | 1–5 | 1.12 | 0.46 | – | −.03 | .14** | .17** | .28** | .28** | — | ||||

| 7. Offense Severity | 1–7 | 5.55 | 1.48 | 0.89 | .10** | −.04 | .17** | .10** | .07* | −.02 | — | |||

| 8. Objection Severity | 1–7 | 2.91 | 1.57 | 0.89 | −.02 | .13** | .19** | .11** | .13** | .15** | .02 | — | ||

| 9. Objection Attitude | 1–7 | 4.35 | 2.05 | 0.97 | .19** | −.17** | .04 | .02 | −.07* | .03 | .36** | −.48** | — | |

| 10. Objection Effectiveness | 1–7 | 3.77 | 1.90 | 0.96 | .21** | −.13** | .14** | .05 | −.02 | .07* | .38** | −.28** | .78** | — |

| 11. Moral Judgment | 1–7 | 4.96 | 1.93 | 0.96 | .13** | −.15** | −.00 | −.00 | −.06 | .01 | .38** | −.55** | .84** | .75** |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01

Means, standard deviations, alpha, and zero-order correlations for measured variables

| Variable . | Scale . | Mean . | SD . | Alpha . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Emotion | 0–10 | 5.44 | 2.35 | – | — | |||||||||

| 2. Negative Emotion | 0–10 | 3.31 | 2.77 | – | −.62** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Emotional Arousal | 0–10 | 3.48 | 2.49 | – | .12** | .13** | — | |||||||

| 4. Anger | 1–5 | 1.61 | 0.90 | – | −.41** | .47** | .23** | — | ||||||

| 5. Disgust | 1–5 | 1.71 | 1.01 | – | −.49** | .54** | .18** | .79** | — | |||||

| 6. Guilt | 1–5 | 1.12 | 0.46 | – | −.03 | .14** | .17** | .28** | .28** | — | ||||

| 7. Offense Severity | 1–7 | 5.55 | 1.48 | 0.89 | .10** | −.04 | .17** | .10** | .07* | −.02 | — | |||

| 8. Objection Severity | 1–7 | 2.91 | 1.57 | 0.89 | −.02 | .13** | .19** | .11** | .13** | .15** | .02 | — | ||

| 9. Objection Attitude | 1–7 | 4.35 | 2.05 | 0.97 | .19** | −.17** | .04 | .02 | −.07* | .03 | .36** | −.48** | — | |

| 10. Objection Effectiveness | 1–7 | 3.77 | 1.90 | 0.96 | .21** | −.13** | .14** | .05 | −.02 | .07* | .38** | −.28** | .78** | — |

| 11. Moral Judgment | 1–7 | 4.96 | 1.93 | 0.96 | .13** | −.15** | −.00 | −.00 | −.06 | .01 | .38** | −.55** | .84** | .75** |

| Variable . | Scale . | Mean . | SD . | Alpha . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Emotion | 0–10 | 5.44 | 2.35 | – | — | |||||||||

| 2. Negative Emotion | 0–10 | 3.31 | 2.77 | – | −.62** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Emotional Arousal | 0–10 | 3.48 | 2.49 | – | .12** | .13** | — | |||||||

| 4. Anger | 1–5 | 1.61 | 0.90 | – | −.41** | .47** | .23** | — | ||||||

| 5. Disgust | 1–5 | 1.71 | 1.01 | – | −.49** | .54** | .18** | .79** | — | |||||

| 6. Guilt | 1–5 | 1.12 | 0.46 | – | −.03 | .14** | .17** | .28** | .28** | — | ||||

| 7. Offense Severity | 1–7 | 5.55 | 1.48 | 0.89 | .10** | −.04 | .17** | .10** | .07* | −.02 | — | |||

| 8. Objection Severity | 1–7 | 2.91 | 1.57 | 0.89 | −.02 | .13** | .19** | .11** | .13** | .15** | .02 | — | ||

| 9. Objection Attitude | 1–7 | 4.35 | 2.05 | 0.97 | .19** | −.17** | .04 | .02 | −.07* | .03 | .36** | −.48** | — | |

| 10. Objection Effectiveness | 1–7 | 3.77 | 1.90 | 0.96 | .21** | −.13** | .14** | .05 | −.02 | .07* | .38** | −.28** | .78** | — |

| 11. Moral Judgment | 1–7 | 4.96 | 1.93 | 0.96 | .13** | −.15** | −.00 | −.00 | −.06 | .01 | .38** | −.55** | .84** | .75** |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01

Emotional responses

We measured participant’s emotional responses (i.e., positive emotion, negative emotion, emotional arousal, and feelings of anger, disgust, and guilt) to the stimuli. These single-item measurements were developed based on different studies: Positive emotion, negative emotion, and emotional arousal were measured on a 0–10 slider from not at all to extremely (Betella & Verschure, 2016), and feelings of anger, disgust, and guilt were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very slightly or not at all to 5 = Extremely; Molho et al., 2017).

Attitudinal responses

We measured attitudes toward the message and its perceived effectiveness on 7-point semantic differential scales, with larger values indicating more positive attitudes and higher effectiveness, respectively. The measurement for attitude consisted of three items adapted from Lee (2013) (e.g., I disliked this reply—I liked this reply); and the measure for message effectiveness was based on Dillard and Ye (2008) and consisted of four items (e.g., This reply was completely not persuasive—completely persuasive).

Behavioral intentions

To assess behavioral intentions toward the offense and objection messages, participants were asked how they would react if they came across a similar comment on a social media platform that they normally use. They were provided with six options: upvote, downvote, flag, share, reply, and would not react, and participants could select all options that apply to them. Intentions for each type of behavior were dummy coded (0 = would not behave in this way, 1 = would behave in this way).

The severity of offense and objection

The measurement for offense severity consisted of four items adapted from Bastiaensens et al. (2014; e.g., This comment was not severe—severe). In addition to perceived severity, a measure of objection severity was needed to reflect perceived emotional harm and pain inflicted on a specific target and developed by combining items from Bastiaensens et al. (2014) and Vangelisti & Young (2000). It consisted of five items (e.g., this reply did not hurt the offender at all—hurt the offender quite a bit), one of which was dropped because of a low factor loading. Both scales were assessed on a 7-point semantic differential scale, with larger values indicating higher severity.

Results

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, alphas, and zero-order correlations for all the measured variables are shown in Table 2.

Preliminary analyses on objection severity

Before examining the effects of different types of objections, pre-registered preliminary analyses were conducted to examine how people feel about these objections. First, a mixed-effect analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the severity of various objections while controlling for the fixed effects of offenses and their interaction with objections, as well as the random effects of objection messages nested in the offense-objection interaction. Results indicated significant differences in objection severity, F(6, 911) = 23.11, p < .001, with Tukey’s HSD pairwise comparisons revealing that a threatening-violent warning was considered the most severe, and a threatening-reputational attack was viewed as more severe than a dismissal-objectionable comment (see Table 3).

Pairwise comparisons of objections on severity, moral judgment, attitudes, and perceived effectiveness toward the objection

| Objection . | M(SD) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | 2.30(1.25)c | 5.47(1.76)bc | 4.79(1.84)bc | 3.77(1.80)b |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | 2.38(1.21)bc | 5.93(1.24)c | 5.25(1.71)c | 4.85(1.49)c |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | 2.46(1.24)bc | 5.80(1.31)bc | 5.32(1.74)c | 4.86(1.74)c |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | 3.28(1.44)b | 4.76(1.80)b | 4.03(2.02)b | 3.52(1.75)b |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | 4.91(1.31)a | 2.38(1.43)a | 1.97(1.34)a | 2.11(1.40)a |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | 2.48(1.27)bc | 5.18(1.59)bc | 4.33(1.64)bc | 3.55(1.73)b |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | 2.58(1.44)bc | 5.18(1.81)bc | 4.70(1.94)bc | 3.73(1.93)b |

| Objection . | M(SD) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | 2.30(1.25)c | 5.47(1.76)bc | 4.79(1.84)bc | 3.77(1.80)b |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | 2.38(1.21)bc | 5.93(1.24)c | 5.25(1.71)c | 4.85(1.49)c |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | 2.46(1.24)bc | 5.80(1.31)bc | 5.32(1.74)c | 4.86(1.74)c |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | 3.28(1.44)b | 4.76(1.80)b | 4.03(2.02)b | 3.52(1.75)b |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | 4.91(1.31)a | 2.38(1.43)a | 1.97(1.34)a | 2.11(1.40)a |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | 2.48(1.27)bc | 5.18(1.59)bc | 4.33(1.64)bc | 3.55(1.73)b |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | 2.58(1.44)bc | 5.18(1.81)bc | 4.70(1.94)bc | 3.73(1.93)b |

Note: Within columns, objection types that share the same letter are not different from each other at a p-value level of .05.

Pairwise comparisons of objections on severity, moral judgment, attitudes, and perceived effectiveness toward the objection

| Objection . | M(SD) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | 2.30(1.25)c | 5.47(1.76)bc | 4.79(1.84)bc | 3.77(1.80)b |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | 2.38(1.21)bc | 5.93(1.24)c | 5.25(1.71)c | 4.85(1.49)c |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | 2.46(1.24)bc | 5.80(1.31)bc | 5.32(1.74)c | 4.86(1.74)c |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | 3.28(1.44)b | 4.76(1.80)b | 4.03(2.02)b | 3.52(1.75)b |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | 4.91(1.31)a | 2.38(1.43)a | 1.97(1.34)a | 2.11(1.40)a |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | 2.48(1.27)bc | 5.18(1.59)bc | 4.33(1.64)bc | 3.55(1.73)b |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | 2.58(1.44)bc | 5.18(1.81)bc | 4.70(1.94)bc | 3.73(1.93)b |

| Objection . | M(SD) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | 2.30(1.25)c | 5.47(1.76)bc | 4.79(1.84)bc | 3.77(1.80)b |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | 2.38(1.21)bc | 5.93(1.24)c | 5.25(1.71)c | 4.85(1.49)c |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | 2.46(1.24)bc | 5.80(1.31)bc | 5.32(1.74)c | 4.86(1.74)c |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | 3.28(1.44)b | 4.76(1.80)b | 4.03(2.02)b | 3.52(1.75)b |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | 4.91(1.31)a | 2.38(1.43)a | 1.97(1.34)a | 2.11(1.40)a |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | 2.48(1.27)bc | 5.18(1.59)bc | 4.33(1.64)bc | 3.55(1.73)b |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | 2.58(1.44)bc | 5.18(1.81)bc | 4.70(1.94)bc | 3.73(1.93)b |

Note: Within columns, objection types that share the same letter are not different from each other at a p-value level of .05.

Second, we evaluated whether perceptions of objection severity vary more by objection type or by persons. By calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient, we found that 32.8% of the variance in objection severity was explained by objection types, while individual differences explained 61.7% of the variance.

Lastly, to examine whether exposure to objections changes people’s perceptions of the offense, a series of t-tests were conducted to compare offense severity between those exposed solely to offenses and those exposed to both offense and objection. Results showed no significant difference for each type of offense (Misinformation: t(64) = −0.19, p = .85; Harassment: t(57) = −0.44, p = .66; Hate Speech: t(66) = −0.46, p = .65), indicating that people’s perceptions of offenses were not impacted by exposure to objections.

Main and interaction effects of objections

To test the main effects of objections and interaction effects between objections and offenses (RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3), we conducted a series of mixed-effect logistic regressions with behavioral intentions as the outcome variables and a series of mixed-effect ANOVAs with emotional, attitudinal, and moral responses as the outcome variables. Each model included objections, offenses, and the interaction between them as fixed factors and specific objection messages nested in the offense-objection interaction as a random factor. HSD was used to test pairwise comparisons.

Behavioral intentions

We found significant main effects of offenses and objections (RQ1) and interaction effects between them (RQ3) on behavioral intentions toward the offense and objection. As shown in Table 4, people are most likely to downvote and least likely to upvote a threatening-violent warning. They also prefer to downvote threatening-reputational attacks over imploring-conscientious appeals and dismissal-objectionable comments. Conversely, people intend to upvote imploring-conscientious appeals more than both threatening objections and preserving-personal abstinence, and imploring-logical appeals are upvoted more than preserving-personal abstinence.

Pairwise comparisons of objections on intentions to downvote and upvote objections

| Objection . | logit(se) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to downvote . | Intention to upvote . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | −2.93(0.40)c | −0.34(0.21)abc |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | −3.29(0.48)c | 0.10(0.21)a |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | −2.63(0.36)bc | −0.01(0.21)ab |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | −1.55(0.23)b | −0.90(0.23)bc |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | −0.36(0.18)a | −3.40(0.53)d |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | −15.86*abc | −1.05(0.24)c |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | −2.63(0.40)bc | −0.49(0.21)abc |

| Objection . | logit(se) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to downvote . | Intention to upvote . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | −2.93(0.40)c | −0.34(0.21)abc |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | −3.29(0.48)c | 0.10(0.21)a |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | −2.63(0.36)bc | −0.01(0.21)ab |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | −1.55(0.23)b | −0.90(0.23)bc |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | −0.36(0.18)a | −3.40(0.53)d |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | −15.86*abc | −1.05(0.24)c |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | −2.63(0.40)bc | −0.49(0.21)abc |

Note: Within columns, objection types that share the same letter are not different from each other at a p-value level of .05. For Preserving-Personal Abstinence*, only two persons chose to downvote, while the vast majority did not, leading to a high standard error. This makes comparisons with other groups statistically challenging.

Pairwise comparisons of objections on intentions to downvote and upvote objections

| Objection . | logit(se) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to downvote . | Intention to upvote . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | −2.93(0.40)c | −0.34(0.21)abc |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | −3.29(0.48)c | 0.10(0.21)a |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | −2.63(0.36)bc | −0.01(0.21)ab |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | −1.55(0.23)b | −0.90(0.23)bc |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | −0.36(0.18)a | −3.40(0.53)d |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | −15.86*abc | −1.05(0.24)c |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | −2.63(0.40)bc | −0.49(0.21)abc |

| Objection . | logit(se) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to downvote . | Intention to upvote . | |

| Dismissal-Objectionable Comment | −2.93(0.40)c | −0.34(0.21)abc |

| Imploring-Conscientious Appeal | −3.29(0.48)c | 0.10(0.21)a |

| Imploring-Logical Appeal | −2.63(0.36)bc | −0.01(0.21)ab |

| Threatening-Reputational Attack | −1.55(0.23)b | −0.90(0.23)bc |

| Threatening-Violent Warning | −0.36(0.18)a | −3.40(0.53)d |

| Preserving-Personal Abstinence | −15.86*abc | −1.05(0.24)c |

| Preserving-Group Maintenance | −2.63(0.40)bc | −0.49(0.21)abc |

Note: Within columns, objection types that share the same letter are not different from each other at a p-value level of .05. For Preserving-Personal Abstinence*, only two persons chose to downvote, while the vast majority did not, leading to a high standard error. This makes comparisons with other groups statistically challenging.

Regarding the main effects of offenses, people are more likely to upvote an objection when the offense is hate speech compared to harassment (estimate = 0.82, p = .01). In addition, people are more likely to downvote and flag a hate speech compared to misinformation (Downvote: estimate = 0.57, p = .001; Flag: estimate = 1.28, p < .001) and harassment (Downvote: estimate = 0.51, p = .005; Flag: estimate = 1.16, p < .001).

Pairwise comparisons revealed significant offense-objection interaction effects on downvoting and upvoting objections (RQ3). Specifically, for misinformation, a threatening-violent warning is more likely to be downvoted compared to all other objections except for threatening-reputational attacks. Similarly, for harassment, a threatening-violent warning tends to be downvoted compared to a dismissal-objectionable comment, imploring-conscientious appeal, and imploring-logical appeal. For hate speech, a threatening-violent warning tends to be downvoted compared to all other objections except for preserving-personal abstinence. Regarding upvoting intentions, for misinformation, people are more likely to upvote imploring-conscientious appeal and imploring-logical appeal compared to a threatening-violent warning. For harassment, people are more likely to upvote imploring-conscientious appeal, imploring-logical appeal, and dismissal-objectionable comment compared to a threatening-violent warning. Lastly, for hate speech, compared to a threatening-violent warning, all other objections except for preserving-personal abstinence tend to be upvoted.

Moral, emotional, and attitudinal responses

We also found significant main effects of offenses and objections (RQ2) but no interaction effects (RQ3) on moral judgments, attitudes, and perceived effectiveness of the objection. There were also main effects of offenses on emotional responses (see Table 5). Specifically, people feel more negative emotions and guilt when exposed to hate speech compared to misinformation. In addition, people evaluate the objection as more attitudinally favorable and effective when exposed to hate speech compared to harassment. Lastly, people feel angrier, more disgusted, and perceive objections as more morally favorable when exposed to hate speech compared to both misinformation and harassment.

Pairwise comparison of offenses on emotional, moral, and attitudinal responses

| Offense . | M(SD) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions . | Anger . | Disgust . | Guilt . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Misinformation | 2.87(2.75)a | 1.47(0.84)a | 1.52(0.94)a | 1.08(0.36)a | 4.79(2.01)a | 4.28(2.14)ab | 3.73(1.95)ab |

| Harassment | 3.36(2.68)ab | 1.54(0.81)a | 1.65(0.89)a | 1.11(0.42)ab | 4.61(1.86)a | 3.96(1.89)a | 3.40(1.86)a |

| Hate Speech | 3.68(2.83)b | 1.81(1.00)b | 1.95(1.15)b | 1.18(0.57)b | 5.49(1.79)b | 4.8(2.03)b | 4.18(1.82)b |

| Offense . | M(SD) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions . | Anger . | Disgust . | Guilt . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Misinformation | 2.87(2.75)a | 1.47(0.84)a | 1.52(0.94)a | 1.08(0.36)a | 4.79(2.01)a | 4.28(2.14)ab | 3.73(1.95)ab |

| Harassment | 3.36(2.68)ab | 1.54(0.81)a | 1.65(0.89)a | 1.11(0.42)ab | 4.61(1.86)a | 3.96(1.89)a | 3.40(1.86)a |

| Hate Speech | 3.68(2.83)b | 1.81(1.00)b | 1.95(1.15)b | 1.18(0.57)b | 5.49(1.79)b | 4.8(2.03)b | 4.18(1.82)b |

Note: Within columns, offense types that share the same letter are not different from each other at a p-value level of .05.

Pairwise comparison of offenses on emotional, moral, and attitudinal responses

| Offense . | M(SD) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions . | Anger . | Disgust . | Guilt . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Misinformation | 2.87(2.75)a | 1.47(0.84)a | 1.52(0.94)a | 1.08(0.36)a | 4.79(2.01)a | 4.28(2.14)ab | 3.73(1.95)ab |

| Harassment | 3.36(2.68)ab | 1.54(0.81)a | 1.65(0.89)a | 1.11(0.42)ab | 4.61(1.86)a | 3.96(1.89)a | 3.40(1.86)a |

| Hate Speech | 3.68(2.83)b | 1.81(1.00)b | 1.95(1.15)b | 1.18(0.57)b | 5.49(1.79)b | 4.8(2.03)b | 4.18(1.82)b |

| Offense . | M(SD) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions . | Anger . | Disgust . | Guilt . | Moral judgment . | Attitude . | Effectiveness . | |

| Misinformation | 2.87(2.75)a | 1.47(0.84)a | 1.52(0.94)a | 1.08(0.36)a | 4.79(2.01)a | 4.28(2.14)ab | 3.73(1.95)ab |

| Harassment | 3.36(2.68)ab | 1.54(0.81)a | 1.65(0.89)a | 1.11(0.42)ab | 4.61(1.86)a | 3.96(1.89)a | 3.40(1.86)a |

| Hate Speech | 3.68(2.83)b | 1.81(1.00)b | 1.95(1.15)b | 1.18(0.57)b | 5.49(1.79)b | 4.8(2.03)b | 4.18(1.82)b |

Note: Within columns, offense types that share the same letter are not different from each other at a p-value level of .05.

With regard to objections (see Table 3), a threatening-violent warning was rated lowest in terms of appropriateness, justifiability, deservedness, attitudinal favorability, and effectiveness. However, an imploring-conscientious appeal was viewed as more morally and attitudinally favorable and persuasive than both threatening objections. Also, an imploring-logical appeal outperformed both threatening objections in terms of attitudinal favorability and message effectiveness. Other types of objections were rated in the middle.

In summary, people tend to consider imploring objections, particularly conscientious appeals, as more morally and attitudinally favorable and effective, with higher upvote intentions. In contrast, threatening objections, especially violent warnings, are viewed as the least morally and attitudinally favorable and least persuasive and tend to be downvoted by the audience.

Serial mediation on objections

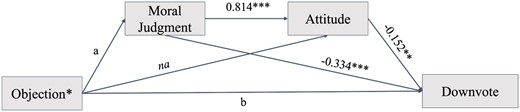

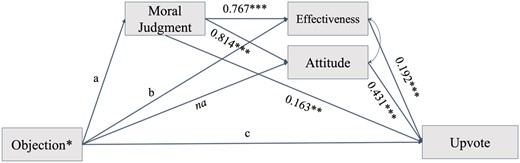

Given that moral, emotional, and attitudinal responses were correlated with each other in an expected way, we next explored whether there is a serial mediation from objections to behavioral intentions via moral judgments and emotional and attitudinal responses (H1). Only intentions of downvoting and upvoting the objection were considered outcome variables because they differ across objections. Based on the associations between objections and mediators (i.e., moral, emotional, and attitudinal responses) and the associations between mediators and outcome variables, we developed a path model for upvotes and downvotes, respectively (see Figures 2 and 3). We used the Lavvan package in R to test these two path models.

The path model with downvote of objections as the outcome variable.

Note: Objection* represents seven dummy-coded objection types with Dismissal-Objectionable Comment as the reference group. a: Compared to dismissal-objectionable comment, the path was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = −0.557, p < .001), Threatening-Reputational Attack (β = −0.129, p < .001), and Imploring-Conscientious Appeal (β = 0.084, p < .012). b: Compared to dismissal-objectionable comment, the direct effect was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = 0.126, p < .020), Threatening-Reputational Attack (β = 0.075, p < .032), and Preserving-Personal Abstinence (β = −0.068, p < .004).

The path model with upvote of objections as the outcome variable.

Note: Objection* represents seven dummy-coded objection types with Dismissal-Objectionable Comment as the reference group. a: Compared to dismissal-objectionable comment, the path was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = −0.557, p < .001), Threatening-Reputational Attack (β = −0.129, p < .001), and Imploring-Conscientious Appeal (β = 0.084, p < .012). b: Compared to dismissal-objectionable comment, the path was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = 0.124, p < .001), Imploring-Conscientious Appeal (β = 0.134, p < .001), and Imploring-Logical Appeal (β = 0.153, p < .001). c: Compared to dismissal-objectionable comment, the direct effect was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = 0.073, p < .014).

Our evidence first showed that people intend to downvote threatening objections due to moral and attitudinal unfavorability. Specifically, the path model results (see Figure 2) supported the serial mediation: Objection → Moral Judgment → Attitude → Intention to Downvote for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = 0.069, p = 0.002) and Threatening-Reputational Attack (β = 0.016, p = .025) when compared to Dismissal-Objectionable Comment. That is, compared to a dismissal objection, people consider violent warnings and reputational attacks as more morally unfavorable, which, in turn, decreases positive attitudes toward them and eventually increases the intention to downvote them. We also found participants’ perceptions of a conscientious appeal as morally favorable are related to a lower inclination to downvote it. Specifically, the mediation path: Objection → Moral Judgment → Intention to Downvote was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = 0.186, p < .001), Threatening-Reputational Attack (β = 0.043, p = .006), and Imploring-Conscientious Appeal (β = −0.028, p = .020), after controlling for the effects of attitudes on downvotes.

We also found that people intend to upvote a conscientious appeal because it is viewed as moral and then attitudinally favorable and effective. Specifically, the path model in Figure 3 supported both serial mediations of Objection → Moral Judgment → Attitude → Intention to Upvote and Objection → Moral Judgment → Effectiveness → Intention to Upvote for Threatening-Violent Warning (via Attitude: β = −0.195, p < .001; via Effectiveness: β = −0.082, p < .001), Threatening-Reputational Attack (via Attitude: β = −0.045, p = .003; via Effectiveness: β = −0.019, p = .008), and Imploring-Conscientious Appeal (via Attitude: β = 0.029, p = .016; via Effectiveness: β = 0.012, p = .032). That is, compared to a dismissal-objectionable comment, people more morally favor a conscientious appeal, which increases their positive attitude and perceived effectiveness for this message and eventually enhances their intention to upvote it. Conversely, people less morally favor both threatening objections, which then reduces their positive attitudes and perceptions of effectiveness toward them and eventually decreases their likelihood of upvoting them.

Interestingly, we also found that after controlling for the effects of moral judgment on effectiveness, people indeed consider a threatening-violent warning as more effective than a dismissal-objectionable comment, and then they are more likely to upvote a violent warning. Specifically, the residual mediation path: Objection → Effectiveness → Upvote was significant for Threatening-Violent Warning (β = 0.024, p = .002), Imploring-Conscientious Appeal (β = 0.026, p = .002), and Imploring-Logical Appeal (β = 0.029, p = .001).

The mismatch between objection and offense

To test whether the proportionality of objections to offenses determines moral judgments (H2), we first calculated the difference between objection severity and offense severity by subtracting objection severity from offense severity, which we called “mismatch” (M = 2.64; SD = 2.13). For negative numbers (Offense Severity < Objection Severity), a larger value means the perceived severity of the offense is smaller than but closer to the severity of the objection; for positive numbers (Offense Severity > Objection Severity), a larger value means the offense is perceived as more severe than the objection.

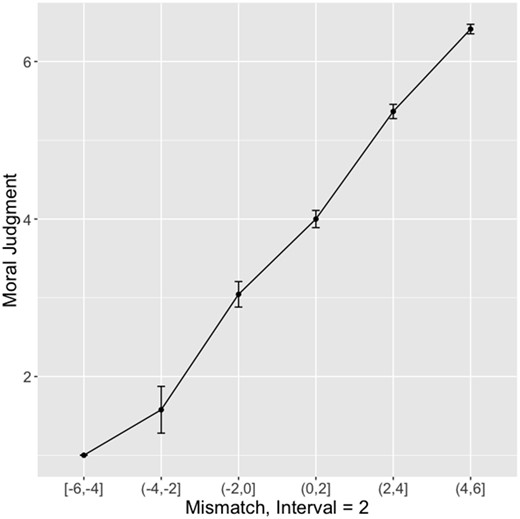

We conducted a mixed-effect regression analysis to test the effect of mismatch on moral judgments while controlling for the fixed effect of objections and offenses and the random effect of objection messages. Results showed that partly opposite of H2, mismatch was positively associated with moral judgment (b = 0.47, p < .001) (see Figure 4 for the plot of mismatch and moral judgment). Specifically, we hypothesized that for a given offense, people would consider the matching objection more appropriate, justified, and deserved. Although this hypothesis was supported when offense severity is smaller than objection severity, we indeed found that, overall, people consider a more benign and less threatening objection as more morally favorable for any offense.

Plot mismatch against moral judgment.

Note: The mean of moral judgment at each interval (i.e., 2) of mismatch was plotted. The error bar indicates one standard error below and above the mean.

We also tested whether mismatch influences downvoting and upvoting the objection via moral judgment and emotional and attitudinal responses (RQ4). The path model with upvoting as the outcome variable supported two serial mediations: (a) Mismatch → (+)Moral Judgment → (+)Attitude → (+)Intention to Upvote (β = 0.212, p < .001) and (b) Mismatch → (+)Moral Judgment →(+) Effectiveness → (+)Intention to Upvote (β = 0.122, p < .001); the path model with downvoting as the outcome variables also supported the serial mediation: Mismatch → (+)Moral Judgment → (+)Attitude → (-)Intention to Downvote (β = −0.071, p = .009). Overall, people consider a less harmful objection to a given offense as more moral, and they then tend to evaluate the objection as more favorable and persuasive, which, in turn, negatively predicts their downvote likelihood and positively predicts their upvote tendency.

Interestingly, our results also indicate that when disregarding morality, people indeed consider an objection that is more proportional to the offense as more persuasive and convincing, and they are more likely to upvote the objection. Specifically, the residual mediation path: Mismatch → (-)Effectiveness → (+)Upvote (β = −0.017, p = .017) was significant while controlling for the effects of moral judgments on effectiveness.

Discussion

To deter objectionable content on social media, people resort to different arguments and rhetorical strategies. It is unclear whether some of these discursive strategies are more effective than others at rallying the on-looking audience’s support, and what mechanisms are responsible for their effectiveness. Therefore, we conducted a between-subject experiment using a simulated social media platform to examine seven types of objections against misinformation, hate speech, and harassment on social media.

Although all types of objections can be morally motivated (e.g., Marwick, 2021), we found that audiences tend to support imploring objections and disapprove of threatening objections, as the former is viewed as more moral, attitudinally favorable, and persuasive compared to the latter. Importantly, instead of going with “an eye for an eye” approach favoring objections based on their proportionality to the offense, audiences tend to “take the high road” by preferring more benign and less threatening objections. Taken together, understanding the impacts of different types of objections on audiences paves the way for developing interventions to teach the most effective objection strategies against problematic behaviors on social media.

Objections, morality, and behavioral intentions

Our study examined seven specific types of objections against problematic content on social media that can be broadly classified into (a) the imploring category based on the mechanism of moral persuasion and norm internalization (conscientious appeal and logical appeal), (b) the threatening category based on the mechanism of punishment (violent warning and reputational attack), and (c) the preservation category based on the mechanism of group boundary management (personal abstinence and group maintenance). The last type of objection, named dismissal-objectionable content, functions as a control message. Broadly, we found that where there were differences, imploring objections outperformed threatening objections in drawing audience support. Specifically, violent warnings are the most likely to be downvoted and least likely to be upvoted among all objection types. In addition, people intend to upvote a conscientious appeal compared to a reputational attack. Similarly, a reputational attack is more likely to be downvoted than a conscientious appeal.

The preference for imploring objections, especially conscientious appeals, over threatening objections aligns with previous literature on people’s inclination toward a restorative approach in addressing wrongdoings under certain conditions (Gromet & Darley, 2009). The restorative approach seeks to resolve rule violations by fostering consensus between the community and the offender, revalidating shared values, and repairing harm, rather than merely imposing a punishment (Bazemore, 1998). Specifically, when there is a need to establish shared values with the offender, or the offense is not severe, people consider a less punitive and more restorative approach as more appropriate in addressing offenses (Gromet & Darley, 2009).

Our results also show the centrality of moral judgments in explaining the differences between imploring and threatening objections. Specifically, compared to threatening objections, people morally favor a conscientious appeal more, and they then evaluate it as more attitudinally favorable and persuasive, predicting a higher likelihood to upvote and a lower likelihood to downvote it. In contrast, although previous research has shown that punishment or “retributive harassment,” such as public shaming, can be acceptable on social media (e.g., Fiesler & Bruckman, 2019; Schoenebeck et al., 2021), our results reveal that onlookers, in general, disapprove of threatening objections, judging them as not moral, appropriate, nor persuasive. These results on moral judgments align with previous research that emphasizes the role of morality judgments in shaping the community’s approval and disapproval of punishments (e.g., Mathew, 2017); that is, the collective tends to approve of moral sanctions and disapprove of morally questionable and improper ones. Therefore, the morality, or appropriateness, justifiability, and deservedness of the objection is a key to rallying audience support in online communities.

Interestingly, threatening objections are not always considered the worst kind. We also found that after controlling for the effects of moral judgment on message effectiveness, a violent warning is seen as more persuasive and compelling than a dismissal comment, earning more upvotes. Namely, when leaving out moral judgment, violent warnings can indeed rally the on-looking audience’s support. These results indicate that although the audience rejects a threatening message because of its abusive language, which is judged as morally debased, they actually consider it effective in calling out inappropriate behaviors. This result supports the potential effectiveness of punishment in deterring future transgressions as offenders may choose to refrain from such actions to avoid punishment (Boyd & Richerson, 1992). In addition, this finding is consistent with foundational theoretical arguments about deindividuation in crowd behavior, suggesting that threats are favored in moments when people lose contact with individual concerns (“conscience”) and focus on group goals (“deterrence”; Reicher et al., 1995). This finding is important because it suggests that in a situation where people prioritize the utility of objections or downplay morality, a violent warning can be looked at more favorably than a message that simply calls out problematic behaviors (dismissal objections).

Our results also pose some interesting puzzles for future research. Consistent with previous literature showing that moral violation can lead to moral outrage (Crockett, 2017; Molho et al., 2017), we found that offenses affect audiences’ moral emotions; that is, people have more negative emotions and feel more angry, disgusted, and guilty when exposed to hate speech compared to misinformation. However, despite some objections being judged more morally inappropriate than others, we did not find a significant effect of objections on emotions themselves. In simple terms, while our respondents were angry at (what they perceived to be) immoral offenses, they were not angry at (what they perceived to be) immoral objections. One reason may be pertinent to the legitimate intentions of objections. Even if a threatening objection is considered over the line, potentially constituting harassment, it intends to punish the offender who has committed moral wrongdoings (e.g., Marwick, 2021). Therefore, threatening objections may be considered more moral and justified compared to initial offenses and thus did not lead to moral outrage. This explanation aligns with previous research revealing that retributive harassment can be viewed as justified (Blackwell et al., 2018).

Our findings also raise the question of why onlookers see some objections as more moral and others as less so. The retributive justice framework suggests that justice is restored when there is a fit between “punishment” and the “crime,” a so-called “an eye for an eye” rule (Carlsmith et al., 2002; Walen, 2015). However, we found that people always morally favor the most benign and least threatening objections, even when encountering a severe offense. These results highlight that when objecting to offenses on social media, people see an emphasis on the values of humanity, logical arguments, and norm articulation as more important than focusing on fairness found in retribution. In other words, while an offender might “deserve” a harsher objection, onlookers still prefer the kinder approach, which we call the “high road.” One reason that explains people’s preference for “taking the high road” over “an eye for an eye” may pertain to the perceived severity of online offenses. Specifically, online offenses are discursive violations that may not be as severe as behavioral offenses because a single discursive offense may not lead to physical harm, financial loss, or any other behavioral damage. When the offense is not severe, a benign objection that calls out problematic behaviors via appealing to moral values or rationality may be viewed as sufficient and appropriate.

Limitations and future research

This study is not without limitations. First, we only measured behavioral intentions, not actual behaviors. However, several meta-analyses have shown that behavioral intentions reliably predict actual behaviors (e.g., Webb & Sheeran, 2006). It is worth noting that the most important factor that weakens the association between intentions and behavior is a lack of perceived or actual behavioral control (e.g., Ajzen, 1991; Webb & Sheeran, 2006), which is not a concern of our study because social media users apparently have control over their one-click reactions. Another moderator of intention–behavior association is habit, in which habit may overwhelm the impact of intention and determine behaviors (e.g., Webb & Sheeran, 2006); therefore, future research should explore the role of habits and automaticity in one-click reactions in moderating the link between behavioral intention and behaviors on social media.

Second, we conducted this experiment on a simulated social media platform with which people had no previous experience and connections. While people often join new platforms with limited knowledge of their social norms and may often encounter online offenses from strangers, the awareness of established social norms may influence people’s perceptions and approval of certain actions or objections (e.g., Brady et al., 2021; Shmargad et al., 2022). For example, it could be possible that in contexts where the normative expectation is clear and explicit, articulating the norm may not be necessary for deterring future wrongdoings. Instead, an intentional norm-violation behavior may increase the audience’s moral outrage and enhance the attractiveness of threatening objections. Therefore, future research should test how the patterns found in this study hold in different types of online communities with already-established social norms.

Lastly, this study focuses only on the effects of objection types rather than message characteristics. Further research may examine, in addition to objection types, how theoretically meaningful message characteristics impact the audience’s perceptions and reactions toward certain objections.

Conclusion