-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kecheng Fang, The social movement was live streamed: a relational analysis of mobile live streaming during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 28, Issue 1, January 2023, zmac033, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac033

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study proposes a sociotechnical framework to study digital media and social movements and uses it to analyze the 2019 protests in Hong Kong. Informed by actor-network theory, this framework examines media technology as infrastructure, practice, and text, and discusses its relation to other actors/actants in the network of social movements. Based on qualitative analysis of live streaming sessions and in-depth interviews with journalists and audiences, I identify and explicate the major actors/actants related to mobile live streaming and argue that mobile live streaming became an obligatory passage point through which actors/actants reached other parts of the network and realized their goals. The assemblage of heterogeneous actors/actants not only contributed to the solidarity and longevity of the movement but also brought risks. This study extends the line of research on media technology and social movements by proposing a framework that examines one specific media technology while maintaining an ecological lens.

Lay Summary

Mobile live streaming was considered a key media technology in the 2019 Hong Kong protests. It was not simply because of the technology itself. Rather, its importance was made by how this technology interacted with other actors in the social movement. For example, the protesters adopted a highly fluid strategy, and it was very difficult to capture their flash mob-like moves by bulky professional cameras. Mobile live streaming became the perfect technology for the movement. Citizens who supported the protests but could not join offline relied on the technology to be involved because they could post live comments while watching. Opponents of the movement also largely relied on it to criticize protesters and express their support for the police. The use of mobile live streaming not only connected more people, promoted emotional involvement, and enhanced the solidarity of the movement, but also brought risks.

Digital media have become an indispensable part of contemporary social movements. As evidenced in major movements such as the Occupy Wall Street Movement and the Arab Spring, activists have effectively used emerging media technology to disseminate information, mobilize the public, and organize protests (Kavada, 2015; Lotan et al., 2011). The 2019 Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) Movement in Hong Kong was no exception. During the city-wide, prolonged political movement, digital technologies were widely used, including the encrypted messaging app Telegram, online forum LIHKG, and mobile live streaming (MLS) on Facebook and YouTube. While messaging apps and online forums were not new to social movements, the central role of MLS was not seen in previous protests. A survey conducted in August 2019 revealed that live streaming was considered the most important information channel in the movement by Hong Kong citizens (scoring 8.12 out of 10), significantly surpassing traditional media (6.85) and social media (6.01) (Lee, 2019). On-site surveys of protesters also found that more than half (55.2%) of them considered live streaming as an important channel for seeking information about the movement, only slightly less than traditional media (56.5%) but much more than online and social media (ranging from 10.2% to 44.8%) (Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey, 2020).

This study provides a framework for the study of media technology in social movements and uses this framework to empirically explain the essential role of MLS in the Anti-ELAB Movement. Informed by the perspective of media ecology (Mattoni, 2017; Mercea et al., 2016; Treré, 2018) and actor-network theory (ANT) (Latour, 1987, 2005), I propose a sociotechnical framework that includes various kinds of human, non-human, and contextual elements, and traces their interconnections. I suggest that media technology can be examined as infrastructure, practice, and text, and that each of the three perspectives should be analyzed in relation with other actors in the network. In the empirical analysis, I explain how the unprecedented importance of MLS as a media technology in the Anti-ELAB Movement was built on its relations with other actors. I also evaluate how the interactions between MLS and other actors/actants contributed but also brought risks to the development of the movement.

This study is at the intersection of mobile technology, digital journalism, political communication, and social movements. It not only provides a timely analysis of an emergent media technology in a recent major social movement, but also contributes to the scholarship on digital media and social movements by providing a useful framework for thoroughly examining one specific media technology while maintaining an ecological lens without falling into the “one-medium fallacy” (Treré, 2018, p. 9).

Theoretical Framework

Digital media and social movements: toward greater complexity

The emergence of digital media has deeply changed the dynamics between the media and social movements. While scholars engaged in debates about whether movements such as the Arab Spring were “tweeted”/”Facebooked” or not around a decade ago (e.g., Lim, 2012; Lotan et al., 2011), they have largely moved beyond the reductionist and deterministic view characterized by a techno-utopian or techno-dystopian lens. Scholars have adopted multiple theoretical views, including collective identity (e.g., Gerbaudo, 2015), network theory (e.g., Castells, 2012), and media ecology (e.g., Earl & Garrett, 2017; Treré, 2012), to replace the functional paradigm and offer greater complexity in approaching digital media and social movements.

The strength of these approaches is that they unpack the dynamics as multiple media technologies, used by various actors across online and offline spaces for different purposes, produce a diverse set of effects together with human agency and social factors. More specifically, the key points are discussed as follows.

First, scholars argue that focusing on single technologies is not a productive way to understand social movements in the current media environment. As Rohlinger and Earl (2017) remind us, media systems are “hybridized” (Chadwick, 2013) and are in “panmediation” (DeLuca et al., 2012), consisting of different formats of legacy and emerging media, as well as public and private media. Hence, it is useful to consider the diversity and interconnections among various media. For example, in their study on the 2011 Egyptian revolution, Aouragh and Alexander (2011) suggest that the synergy between social media and satellite broadcasters, rather than the internet alone, was the key force behind the uprisings. Mason (2012) also indicates that the Arab Spring protests were “planned on Facebook, organized on Twitter, broadcast on YouTube, and then amplified and distributed by Al Jazeera or Indymedia” (Benski et al., 2013, p. 547).

Second, media technologies are used by various actors, not limited to activists. As Lazar et al. (2020) argue, simply focusing on the affordances of digital media would risk losing the sociocultural perspective, including the specific circumstances under which the potential of certain digital media is achieved. For example, social media can be used by activists for connective action, but can also be used by the government for surveillance. Similarly, hashtags can be hijacked by those who work against the movement’s goals (Drüeke & Zobl, 2016). The individualist view of affordances is less helpful than the perspective that considers both the technology and the users.

Third, and related to the previous point, scholars argue that digital media have been used for diverse purposes, and it is difficult to assign specific objectives to them, even among activists. As Gerbaudo (2012, p. 3) suggests, the uses of digital media include a variety of external/representational and internal/organizational purposes. Furthermore, digital media are important not only in “frontstage” activities, such as mobilizing protests and tweeting photos, but also in “backstage” processes, such as collective identity building and meaning construction (Benski et al., 2013; Svensson et al., 2015; Treré, 2018), which have been largely overlooked in instrumental explanations.

Fourth, digital media connect online and offline spaces, instead of only facilitating virtual connection and mobilization. Activists in urban space are still on their smartphones, sending and receiving information about the field. In the process of “cyber-spatial networking” (Kidd & McIntosh, 2016), digital technology should not only be considered as an online tool.

Fifth, previous studies have demonstrated that technology is far from a defining factor in the movements and that the agency of protesters and other social factors should not be disregarded (Aouragh & Alexander, 2011). There is also an “ambivalent, contradictory, and ambiguous nature that characterizes the sinuous dance between media and movements” (Treré, 2018, p. 8), which is far more complicated than the clear-cut relation as implied in the deterministic view.

Sixth, the effects brought about by digital technology are diverse and multi-directional. For example, as Uldam (2018) suggests, social media can empower activists, but can also make them feel insecure and intimidated, due to the fact that they are constantly surveilled by the government and corporations. The low barrier to post on social media enables mass participation, but also creates noise that may inhibit decision-making, innovation, and productivity (Murthy, 2018). Assuming any deterministic relation is unproductive in investigating the dynamic.

The current study is informed by these advances in understanding digital media and social movements, and largely follows the media ecology approach, which emphasizes “the relative and situated reading of any medium against the background of a myriad of contextual factors and their continuous interactions” (Haciyakupoglu & Zhang, 2015, p. 463). I further extend this line of research by unpacking digital media technology as infrastructure, practice, and text, and examining its relationship with other actors in the movement through these three aspects. By infrastructure, I focus on the contextualized affordances provided by the technology to multiple actors. By practice, I emphasize the routines, expectations, norms, and ethics related to the use of digital technology. By text, I highlight the collective making of the product and its discursive power. By complicating the media technology itself, this approach contributes to the better understanding of the complexity in the relationship between digital media and social movements. It also answers Caren et al.’s (2020) call to “move toward a broader conception of media in movements” (p. 443).

Live streaming and protests

We now turn to the review of previous studies on live streaming and social movements. Live streaming is not an entirely new technology in protests. As early as 2008, activists in the Wild Strawberries Students Movement in Taiwan already used their 10.1-inch laptop computers and 3.5G mobile broadband USB modems to live stream the protest 24 hours a day (Hsu, 2010). During the 2011 Occupy Wall Street Movement in the United States and the 15M Movement in Spain, live streaming was used by activists to broadcast the general assemblies, internal meetings, and the everyday lives of the occupations (Kavada & Treré, 2020). Activists in the 2012 Quebec Student Strike also used live streaming to disrupt state surveillance and operated it as a surveillance technology against the police force (Thorburn, 2014).

The democratic potential of live streaming is at the center of many previous studies. As summarized by Kavada and Treré (2020), live streaming is characterized by its immediacy, rawness, liveness, and embedded/embodied perspective, which connect with the democratic cultures of various social movements. It is also believed that live streaming can hold the powerful accountable by gathering evidence and practicing sousveillance (Fan, 2019; Gregory, 2021).

Previous studies have also emphasized the effect of live streaming on audience perception and engagement. Martini (2018) argues that compared with non-live online videos, live streaming on social media platforms provides a different form of connectivity, which tends to be highly intensive yet short-lived in terms of user engagement. Such engagement occurs both between users and streamers, and among users. Gregory (2015) also emphasizes that live streaming can create a ubiquitous, shared witness experience among dispersed watchers and increase audience engagement.

Taken together, previous discussions on MLS and social movements are largely limited to its decontextualized affordances used by activists for social good. They are far from reaching the level of complexity as discussed in the previous section. One exception is a recent study by Kim and Yu (2022), in which they point out that far-right figures also use live streaming to mobilize their followers, and that live streaming sessions can shape a “polemic identity” among participants, which focuses on otherizing and exclusion, rather than solidarity and inclusion. In this study, I offer a more complicated analysis by examining MLS conducted by professional journalists (rather than activists), its interactions with multiple actors in the sociopolitical context, and its diverse effects on the social movement.

Actor-network theory and the analytical framework

To operationalize the empirical approach, I propose a framework that is informed by Actor-Network Theory (ANT). Originated in Science and Technology Studies (STS), ANT is an analytical approach that is especially strong at grasping the complexity of social processes (Couldry, 2020) and helps “regain the sense of heterogeneity” (Latour, 1996, p. 380). A key premise of ANT is the hybridity of society and technology (Latour, 1993)—“the social is always already technical, just as the technical is always already social” (Couldry, 2008, p. 95). In other words, ANT rejects both social and technological determinism. Rather, it regards the associations among different entities as the driving force in making dynamic systems stable.

ANT recognizes both human actors and non-human actants, and focuses on tracing the connections and interactions among actors and actants in a network instead of analyzing discrete actors and actants (Latour, 2005). As Law (2009) suggests, ANT “assumes that nothing has reality or form outside the enactment of those relations” (p. 141). For example, as Archetti (2014) argues in the case of photojournalism, “a journalist with a camera is not the same as one without, just as a camera in the hand of a journalist is not the same as a camera inside a pocket” (p. 588). The power lies in the association between the journalist and the camera rather than in the isolated journalist or the isolated camera. ANT also emphasizes the contingency, both in the position of each actor/actant in the network and in the relations among them. The positions and relations could “change over time depending on the equilibrium of power, strategies, and definitions of the network that the different members of the network have” (Schmitz Weiss & Domingo, 2010, p. 1159). These features are all in line with the media ecology perspective.

ANT is often mistaken as a descriptive approach. However, it also explains. The explanatory power lies within, rather than outside, the network itself. As Latour (1996) claims, “there is no difference between explaining and telling how a network surrounds itself with new resources” (p. 376). When researchers trace the connections and describe how networks grow, they are already providing explanations on why certain actions become stabilized and naturalized. By following actors/actants and the network, we could understand technology and society from an anti-deterministic perspective—development and changes are results of the changing relations among actors and actants, rather than something that is intrinsic and taken for granted. One key concept related to this explanatory power is the “obligatory passage point,” which refers to an actor/actant through which other actors/actants need to pass in order to connect to other parts of the network (Callon, 1984). The obligatory passage point aligns a series of other elements in the network and “becomes strategic through the number of connections it commands” (Latour, 1996, p. 372). Identifying the obligatory passage point and tracing its connections with other elements thus become an important means of explaining the emergence of certain key elements in the networks.

Thanks to ANT’s emphasis on describing continuity and change, communication scholars are especially attracted by ANT’s ability to help explain digital media innovations. Turner (2005) introduces ANT to journalism studies and argues that it is useful to “chart the coming together of journalistic practice and digital technologies” (p. 323). Plesner (2009) argues that ANT could help scholars avoid essentializing the effects of digital technologies. ANT has also been used to study the use of digital technologies in social movements. The concept of connective action by Bennett and Segerberg (2012) borrows from ANT and recognizes social media, smartphones, and other devices as actants alongside human actors. In the study on environmental movements and the #MeToo Movement, Brunner proposes the concept of “wild public networks” to capture the shifting relationships among activists, media technologies, and other actors (Brunner, 2017; Brunner & Partlow-Lefevre, 2020). Joia and Soares (2018) investigate the socio-technical network in the 20 Cents Movement in Brazil from the ANT perspective. They argue that social media was the central node, or the single obligatory passage point in the movement for different actors, including protesters, the government, military police, traditional media, and independent media, to converge.

Based on the media ecology perspective and ANT, I propose an analytical framework to examine the role of media technology in social movements. This framework includes the following components: (1) the examination of media technology asinfrastructure, practice, and text, during which relevant human actors and non-human actants in the network are identified; (2) the tracing of relations among the actors/actants and the evaluation of the position of media technology in the network; and (3) the assessment of the changes in the network brought by the media technology. To illustrate how this framework works, I use it to investigate the adoption and use of MLS in the Hong Kong Anti-ELAB Movement.

The case: MLS in the anti-ELAB movement

Live streaming was previously used by activists to get their voice out, mobilize the participants, and organize activities; but during the Anti-ELAB Movement, it was mainly used by individuals and organizations outside the movement, i.e., journalists and media organizations. Although some grassroots online media (e.g., HKGolden) live streamed the protests and their position was more ambiguously placed between media and activists, most of the popular live streaming were conducted by professional journalists on behalf of institutional media (e.g., Apple Daily and Stand News). This significant difference suggests that for the first time in the history of social movements, MLS was primarily used independently from the movement, which produced more interesting dynamics between the media technology and the protests.

The Anti-ELAB Movement was triggered by a proposed bill to allow extradition to jurisdictions with which Hong Kong did not have bilateral extradition agreements, including Mainland China. Starting from early June 2019, there were frequent peaceful protests, some of which had more than a million participants according to the organizers. A couple of months later, however, the weekly (and even daily) protests frequently deteriorated into violent clashes between protesters and the police. The movement itself gradually evolved into a movement against police brutality and seeking political reforms (Lee et al., 2019; Purbrick, 2019). It was largely halted as the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in early 2020 and the Chinese government issued the draconian National Security Law in mid-2020.

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, surveys suggest that MLS was one of the most important media technologies used in the Anti-ELAB Movement. To understand its adoption and use, this study seeks to answer the following research question (RQ):

RQ1:Why did MLS become a key media technology during the Anti-ELAB Movement?

Once MLS was introduced to the network of the Anti-ELAB Movement, it was expected to interact with other actors and actants in the network and take part in the process of reshaping the movement dynamics. Thus, the following question is also posed:

RQ2:What are the effects produced by the interactions between MLS and other actors/actants in the Anti-ELAB Movement?

Data and methods

As Champ and Johnson (2017) summarize, the approach of ANT guides researchers to gain observational awareness at various “intermediaries” within a setting (Latour, 2005, p. 238) and consider them for later interpretations. Human actors and non-human actants emerge through the process of identifying the intermediaries whose associations with other intermediaries can be more meaningfully interpreted. Researchers then describe the shifting interconnections among the actors and actants in the network and capture the complexity of social processes.

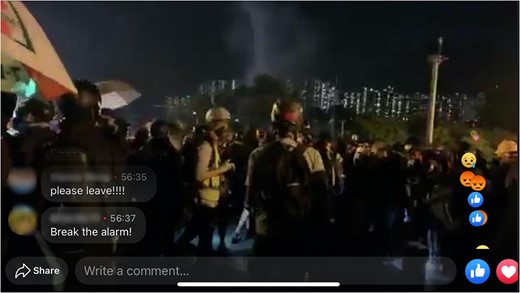

In this study, I rely on two modes of data that help identify actors/actants and interpret their associations. The first is observations of the MLS sessions on Facebook and YouTube. From June to December 2019, I watched around 100 hours of live streaming of the Anti-ELAB Movement, observing the interface provided by the platforms, the video stream, and the reactions from the audiences, including the floating emojis (like, love, haha, wow, sad, and angry) and live comments (see Figure 1). The live streaming sessions were conducted by popular media outlets including Stand News, Apple Daily, RTHK, Oriental Daily, and HK01, as well as by grassroots social media channels including HKGolden, 404 News Media, and Cupid Producer. The aim was to become familiarized with the experience of watching and engaging with MLS and identify the major actors/actants. The live sessions were recorded by the platforms and could be replayed, enabling me to repeatedly engage with the materials. Three types of data were collected during the process: screenshots of important scenes, copies of highly popular or frequently seen comments, and notes on the interactions among actors/actants (e.g., how the audiences reacted to protesters; how the journalists described the police).

The second mode of data is in-depth interviews with both live streaming journalists and audience members. From October 2019 to June 2020, I conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 professional journalists who did MLS during the Anti-ELAB Movement. They worked for six different media organizations and had varying lengths of work experience (from half a year to 15 years). Sixty percent of them were female. The questions focused on how they did their work and how they perceived the role of MLS in the movement. I also asked them to name human actors and nonhuman actants that they considered to be closely associated with their live streaming work. In addition, I interviewed 15 audience members in Hong Kong who watched live streaming sessions of the movement. Their demographics and occupations varied. Some of them were frequent watchers, spending at least two hours per week on the live streaming sessions. Some were occasional watchers, only tuning into live videos once or twice a week. I mainly asked about their experience of watching the live streaming, including how they reacted to the videos, how they talked about it with their friends and on social media platforms, and how it had influenced their perceptions of the movement. The interviewees were recruited through snowball sampling, in which I paid attention to ensure the diversity in backgrounds and experiences related to the movement. All the interviews lasted from one to two hours and were conducted either face-to-face or online via Zoom. Data saturation was achieved after these 30 interviews, as no additional themes or points were proposed by the last few interviewees. Due to the political sensitivity of this topic, especially after the adoption of the National Security Law (many live streaming sessions included slogans and comments that would now be considered illegal), I chose not to provide detailed information about the interviewees in this article.

Data collected from the observations and interviews were analyzed together following a grounded theory approach to identify common themes (Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). During the data collection and analysis, I constantly compared the two modes of data, informing one by the other. For example, some interview questions were developed based on my experience in watching the live streaming sessions, and some answers provided by the journalists and audience members helped me better understand and interpret the video stream and audience engagement that I observed. Through this process, I triangulated the data and identified major actors and actants in the network of movement live streaming. The process also sheds light on the associations among the actors and actants.

Findings

MLS as infrastructure

The first step of the framework is to examine the multiple layers of MLS as a media technology: infrastructure, practice, and text. In this process, we continuously consider the technology in relation to other actors in the Anti-ELAB movement.

Infrastructure refers to “pervasive enabling resources in network form” (Bowker et al., 2010, p. 98), which support certain practices in the background. As Star and Ruhleder (1996) suggest, infrastructure is a relational concept—one’s daily work could be another’s infrastructure. Following this approach, MLS as an infrastructure indicates that it is on the one hand, supported by a set of hardware and software technologies and on the other hand, provides affordances to multiple actors. As a highly developed city with one of the world’s most comprehensive 4G network coverage (Boyland, 2019), Hong Kong provided an ideal technological environment for conducting mobile video streaming. The smartphones were powerful enough, and the MLS platforms on Facebook and YouTube were already mature as they were launched respectively three years and two years before the Anti-ELAB Movement. As informed by the journalist interviewees, most of the media outlets used products developed by LiveU, a company specializing in live broadcasting solutions. They were highly portable, and the most popular device could hold eight sim cards to ensure fast and reliable connection. During the 2008 Wild Strawberries Movement in Taiwan, student activists used the smallest device available at that time—“netbooks,” which weighted 1.2 kg (Hsu, 2010). The Anti-ELAB Movement required even higher portability because there was no fixed site for the protests. A journalist shared that even TV journalists started to use mobile phones to shoot the video during protests because “there were so many unexpected things happening in so many places that it was impossible for TV cameramen to follow with their bulky cameras.”

Algorithms of social media platforms also contributed to the popularization of live streaming as a dominant news genre during the movement. As indicated by a journalist interviewee, her news organization—a small online media organization—relied heavily on Facebook for traffic, which lead them to study Facebook’s algorithm and follow its directions—for example, they attached more photos to posts once they noticed that it could potentially increase the visibility of the posts. Long before the Anti-ELAB Movement, they had already noticed that live streaming videos were highly prioritized by Facebook algorithms in the newsfeed and notifications, and they started to live stream regularly as early as 2018. Consequently, they were well prepared to use live streaming shortly after the protests began. A few other interviewees also mentioned that their media organizations invested more resources in live streaming when they realized that the algorithm favored live videos. This shows that social media platforms as actants do have their agency—they are not neutral tools but bring changes to the network with their own affordances and rules. In optimizing for user engagement and commercial interest, the platforms unexpectedly created a favorable environment for conducting and disseminating MLS.

As an infrastructure, MLS offered various potentials for actors in the Anti-ELAB Movement. One crucial affordance was portability. As a leaderless movement, the Anti-ELAB protests were unscripted and driven by impromptu decisions of the street protesters. The mobility was a key factor in contributing to its impressive longevity. One of the most famous slogans of the movement was “be water”—a quote from martial arts star Bruce Lee, who advised people to be “formless” and “shapeless” as water (Ting, 2020). Arguably, MLS was the best media technology to follow and capture this highly fluid movement. Protesters used all kinds of urban spaces in Hong Kong based on the strategy of “blossom everywhere.” They were then made visible through MLS sessions. From the production side, journalists could follow the protest in real time and record the possible incidents as comprehensively and in as much detail as possible. From the consumption side, audiences watched episodes of first-person view video dramas with unexpected twists. “It was like real-person VR,” commented an audience member.

MLS as infrastructural also supported the flow of emotions. Protesters used various emotional appeals and organized activities that were deeply touching, such as human chains. The violent clashes between protesters and police, as well as the mysterious death of a few protesters, further fueled the level of emotional engagement. With its first-person view and immediate reactions, MLS displayed more authenticity and intimacy than other media formats and achieved a high level of emotional synergy with the movement.

MLS in the Anti-ELAB Movement also served as a sousveillance infrastructure. The police’s behavior was under scrutiny in the live streaming videos. Similar to Thorburn’s (2014) observation of the Quebec Student Strike, live streaming in the Anti-ELAB Movement monitored police violence and challenged the legitimacy of state power. One of the earliest live streaming videos that went viral and infuriated citizens was Stand News’s live coverage of the July 21 Yuen Long attack, during which a group of thugs in white shirts indiscriminately attacked citizens at a subway station. Stand News’s journalist was beaten to the ground but did not stop live streaming, which was watched by an audience of hundreds of thousands. There was wide speculation that the thugs had connections with the police and government. Police brutality drove the popularity of MLS sessions, as many audiences highly concerned with it chose to tune in as witnesses of possible violence. Several audience interviewees felt that they were helping monitor the police through journalists’ live streaming cameras.

MLS as (journalistic) practice

In the case of Anti-ELAB Movement, MLS was mainly used by professional media. Thus, the aspect of MLS aspractice refers to how MLS enables a new journalistic format, and how norms and ethics evolve around it. My journalist interviewees highlighted four unique characteristics of MLS as a journalistic format. First, it is unedited, without editors being the gatekeeper. On-site reporters are granted with unprecedented power to decide what to include or exclude. Their voiceovers, including introductions, explanations and commentaries on what is happening, can also be sent directly and unfiltered to the audiences. Second, it disrupts traditional forms of journalistic storytelling, including the rigid structure of proper beginning, middle, and end (Andén-Papadopoulos, 2013), and the norm of a detached and impartial standpoint. Although most of the journalist interviewees still considered objectivity important during MLS, they also admitted that this format unavoidably placed them in a more participatory and even interventionist position. Third, MLS is unstaged and spontaneous. It is difficult to estimate what happen next and even how long the live streaming sessions will be. Although a challenging situation for journalists, it conveys an extra sense of authenticity. Fourth, it is interactive and participatory because audiences could send comments and emoji reactions, which float on the video and become an essential part of this journalistic format.

It is notable that the most active live streamers during the movement were not necessarily the largest media organizations with the most resources. In fact, Stand News, which was widely regarded as the most important and popular media outlet that conducted MLS, was only a five-year-old online media with a dozen staff members when the movement started. The interviews suggested that Stand News’s success in live streaming was thanks to, rather than despite of, the fact that it was small and insignificant. Journalists at Stand News shared that there was no hierarchy in the newsroom, and they were granted total autonomy in experimenting with live streaming. One journalist said that she had no experience in any kind of video reporting, but she was given the chance to do the live streaming independently shortly after the movement broke out. She shared, “The editors promised to give me some instructions in June, but I have received nothing until now (December).” The extremely high degree of flexibility in the newsroom decision-making process helped online media such as Stand News to seize the opportunity quickly, in contrast to the slow process and hierarchical structure within large legacy media which often impede innovations (Lowrey, 2011), as in the case of Ming Pao. Journalists at Stand News were also allowed to add their personal touch in the live streaming. One journalist provided real-time comments like a sports commentator. Another journalist, who was also a stand-up comedian, frequently interacted with the audiences and offered his comments with a strong personal style. Both were highly popular among audiences and attracted many loyal fans, who would call out their nicknames during their live streaming sessions. Such intimate relationships between journalists and audience members further contributed to the popularity of Stand News’s MLS sessions.

The relative flexibility of online media was echoed by a journalist at another digital outlet HK01. He claimed that all the journalists at HK01 were required to be able to multi-task—“If I conduct an interview, I will decide whether it should be presented in text or in video, and I have to be able to do both.” Therefore, every HK01 journalist was capable of video reporting, and the majority of them did participate in the live streaming work in 2019. Apple Daily was the most active player in live streaming among the large legacy media organizations. Journalists shared that due to the pressure of digitalization, the newsroom had been training the video skills of journalists during the first half of 2019. It coincidentally paved the way for live streaming of the movement. In these cases, the organizational structures of professional media have created inclusions and exclusions in MLS. It is evident that media organizations and journalists as actors/actants have also shaped the network.

In the live coverage of the protests, police became a major impediment but also a catalyst for more confrontational and dramatic scenes, as their attitude toward journalists grew increasingly negative. Almost all the journalist interviewees had experienced conflict with the police, either verbally or physically. Some were pepper-sprayed, and some saw the police shoot tear gas directly at them. As the tension escalated, some journalists chose to fight back by directly responding to the police and stating the rights of the press. Such responses were sometimes broadcasted live and attracted much public attention. For some experienced audience members, witnessing occasional confrontations between journalists and police became part of the live streaming watching experience. Thus, the impediments created by the police ironically further promoted the popularity of MLS sessions.

MLS as text

MLS sessions during the Anti-ELAB Movement produced a large amount of live streaming videos, which were subsequently commented on, circulated, and edited for further usage. Even if not directly involved in street protests, an individual could also virtually participate in the movement by watching live videos and post comments, which became another indispensable layer of the MLS text. Several audience interviewees shared that they were unable to join street protests due to various reasons, and they felt that watching and engaging with the live streaming was the least they could do for the movement. Seeing the real-time development of protests with other fellow watchers, they felt more connected with the movement and thus belonged to the larger community of pro-democracy citizens. The audience members that I interviewed overwhelmingly described it as “real,” “direct,” “a channel to get to know what was happening in the streets,” and even “addictive.” User engagement with MLS videos was high during the 2019 protests, as evidenced in the large number of real-time comments and emoji reactions. Frequently seen comments include support and care for the journalists (e.g., “Be careful, journalist!” “Respect for the press!”), analysis of the conflicts captured in the live video (e.g., “That’s a trap! Run away, everyone!” “You call vandalizing as peaceful protest?”), repeated posting of popular slogans of the movement (e.g., “Five Demands, Not One Less!”), calling for more participation (e.g., “Everyone resist together!”), as well as swear words from all groups—pro-government watchers cursing protesters, supporters of the movement swearing at the police and the government, and pro-democracy and pro-government watchers attacking each other. In general, the comments were highly emotional (Fang & Cheng, 2022), contributing to the affective nature of the MLS text.

Enabled by the real-time interactions, audiences could also take part in the creation of MLS text. As one interviewee shared, “I would say I was not ‘watching’ live stream. Rather, I was ‘participating’ in the live stream, because I could interact with the journalist, and chat with other participants. I once provided a tip to the journalist in the comment section, suggesting her to go to a certain location where the police were having conflicts with protesters. She did notice my comment and went there.”

Many audience members suggested that they not only interacted with journalists and commented on the street protesters and police, but also discussed and disputed with other fellow watchers. For them, engagement through live comments and emoji reactions is baked into the experience of watching MLS. Watchers of live streaming sessions included pro-government users, who would frequently post live comments attacking protesters and watchers supporting the movement. Instead of discouraging the pro-democracy watchers, these comments ended up encouraging them to counterattack, which usually included labeling pro-government users as “fifty-centers” (五毛), a derogatory term referring to online commentators hired by the Chinese government. The fights between these two groups further drove up user engagement and, according to some audience interviewees, became an essential part of the watching experience.

MLS as text also provided opportunities for further editing and circulation of the video clips. As a decentralized movement, the Anti-ELAB Movement was actually well organized, with activists taking up different roles. One important group of activists were in the “publicity group (文宣組)”, which produced and circulated posters, memes, as well as viral posts and videos on social media platforms. According to interviewees who had knowledge about the movement’s organization, members of the publicity group kept a close eye on live streaming sessions from various sources and would quickly make short video clips showing police brutality, edited from the live videos. Some short videos went viral and contributed to the mobilization and solidarity of the movement. Although the videos were originally shot by professional media, the activists reframed them from a raw, balanced representation of protests to materials that focused on exposing police brutality. As a journalist interviewee suggested, “media were quite passive in this process. These short clips might make some people question our objectivity, but the thing is—we did not do the framing of the videos.” This process further reflects the networked nature of this live streamed movement, showing that MLS should be understood as part of a larger ecological system, rather than an isolated technology. MLS as text was a key linking those different media technologies. As the important episodes were made into short videos and GIFs by the publicity group and kept circulating on social media platforms, the fleeting nature of live streaming did not hurt the longevity of the movement. Without the publicity group, MLS could not function as a memory device. Without MLS, the activists would lose the most important resource for producing mobilization materials.

The obligatory passage point in the network

Based on the above analysis of how MLS as infrastructure, practice, and text interacted with the major actors and actants in the network, I address RQ1 regarding the adoption and popularization of MLS in the Anti-ELAB Movement. The indispensable role of MLS is explained by its position in the network—other elements have to pass it in order to connect to other parts of the network and achieve their goals.

For media organizations, MLS was the essential option if they aimed at producing influential and engaging coverage at the protest sites. Digital outlets such as Stand News gained a critical advantage in the market by following this path instead of offering live text and photo updates or other journalistic forms. Previous heavy use of social media platforms also made it intuitive and easy for them to adopt MLS. Journalist interviewees at those outlets recalled that there was literally no other way that could have worked better. As one of them shared, “it was super easy for us to get started, as it only required a smartphone, and Facebook had already been our major channel of content distribution. It was where our followers were, and many of us were used to interacting with the audiences on a daily basis. So, I really cannot imagine why we would not fully devote to the live streaming of the movement.”

For movement participants with different roles, MLS was necessary for them to be seen (for street protesters), be involved (for watchers), and to perform their duties (for the publicity group). Activists in the street widely considered MLS as a vital component of the movement. They understood that to agitate the public and mobilize subsequent actions, their struggles and the police brutality they experienced had to be captured and amplified by live streaming phones. Therefore, watchers of the sessions could sometimes hear the protesters calling the journalists to shoot certain conflicts. Some protesters would also persuade the journalists to turn their camera away from the making of Molotov cocktails, as that could potentially become evidence against them if they were charged. The publicity group further contributed to this carefully crafted visibility by selecting MLS videos to produce spreadable media. It is evident that MLS was more than a powerful resource for the activists—it was an essential part of the overall strategy.

Interestingly, opponents of the movement also relied on MLS to criticize protesters and express their support for the police. Fearing that they would be easily outnumbered, few of them would choose to confront protesters in the physical space, except for a few carefully organized sessions in shopping malls when hundreds of them waved the Chinese national flag and sang the national anthem together. For online space, it was also challenging to express pro-government opinions in forums like LIHKG where activists gathered and strong norms and consensus were established. In contrast, the live comment section of MLS sessions, where messages were fleeting and no strong norm had been set, provided a new place where they could easily mask their identity and express their criticisms without being afraid of repercussion. Thus, it became the gathering point of opponents.

In sum, MLS, as infrastructure, practice, and text, became the obligatory passage point into the network, rendering it the key media technology during the Anti-ELAB Movement.

How MLS reshaped the dynamics of the movement

After introducing the formation of the network and explaining the central role of MLS, we now turn to the second RQ: how did the assemblage of heterogeneous actors/actants reshape the movement? Or, to use the terminology of ANT and to focus on the media technology, how did MLS play the role of mediator in the network, reconfiguring and transforming the dynamics of protest communication, reporting, and the movement in general?

Two live streamed incidents, which were mentioned by multiple interviewees, could provide some insights into this question. In the first incident, a journalist from Stand News was stopped and searched by police when he was conducting live streaming. He did not stop the live session even though the police asked him to do so. He said to the police, “I was only doing my job. Why do I have to do that (stop live streaming)?” The police then continued to frisk him and claimed that the bottled water he was carrying was a weapon that could be used to attack the police. The exchange was live streamed on Facebook and quickly went viral. People considered it as evidence of the courage and wisdom of the journalist, as well as the abusiveness and absurdity of the police.

In the second live streamed incident, the police had set up a cordon to prevent the activists from advancing, and were sending the usual warning through a loudspeaker that “You are participating in an unauthorized assembly and may be prosecuted.” In the intense atmosphere, however, a group of activists started dancing in front of the police and the live streaming cameras. One interviewee described it as a “Stephen Chow-style comedy,” which is known for being “nonsensical” (mo lei tau). According to a journalist interviewee, such an incident would never be promoted by institutional media because it did not fit into any traditional news values. However, it became hugely popular among the public and the clip from the live streaming session was regarded by many as representing the spirit of the movement.

The two incidents showed that MLS was not only a tool for actors to realize their goals, but also an actant with agency to influence various actors/actants and reshape the network. It changed how journalists were working by making them visible actors in the news rather than dispassionate observers; it reconfigured the relation between journalists and audiences by building stronger emotional connections; it lead to unprecedented public support including large donations and enviable reputation enhancement for news organizations such as Stand News, and it gave more power to the public to participate in the process of selecting and editing content to represent the movement and mobilize more participants. Watchers of the MLS sessions were not simply information receivers. Rather, they became emotionally connected with protesters and other fellow citizens. MLS also changed how the police were working—perceiving live streaming journalists as deliberately capturing incidents that would work against them, more police started to target the press on the scene, which lead to more conflicts and deepened antagonism between the police and the journalists, as well as between the police and the activists.

Taken together, MLS boosted affective engagement with the movement, promoted wider participation, created emotional synergy among participants, and arguably contributed to the solidarity and longevity of the movement. However, the central role of MLS also ironically increased the frailty of the network. Seeing the huge influence of MLS, the police enforced more and more restrictions on live streaming journalists since September, including setting up a designated area for them which was far away from the police. As a result, it became increasingly difficult for journalists to clearly capture the actions of the police. According to the journalist interviewees, the police later tried to use the footage of live videos to prosecute protesters. Some news organizations received requests from the police to provide their high-resolution raw footage but refused to comply with them. This possibility made journalists more cautious in filming protesters. MLS was also threatened by overzealous activists, who regarded press as their close allies and even intruded into the private life of some prominent journalists, which made the journalists uncomfortable because it crossed some important lines in professional ethics. Under this pressure, some chose to pause the live streaming work and even stopped completely.

In addition, as MLS captured emotional moments and promoted affective involvement, it also potentially contributed to the radicalization of the movement, which subsequently faced heavy pushback and repression from the government. While we cannot draw any clear-cut relation between MLS and radicalization, it is evident that MLS played a part in the overall radicalization process. The entire network collapsed as violence became more frequent and the government issued draconian measures to crack down on the movement.

Conclusion and discussion

In this study, I propose a relational framework to study media technology and social movement. The framework is informed by the perspective of media ecology and ANT, both of which capture a holistic picture and treat a heterogeneous set of actors/actants in an non-deterministic way (Plesner, 2009). The change of focus from things to relations is beneficial in analyzing complex social processes (Poell et al., 2013). The framework unpacks media technology as infrastructure, practice, and text, and traces its relation with other actors/actants in the network. Applying this framework to analyze the actor-network of MLS during the Anti-ELAB Movement, I argue that MLS became the obligatory passage point for actors/actants to reach other parts of the network and realize their goals. The assemblage of actors/actants in the network increased the affective engagement and facilitated wider participation, which eventually contributed to the solidarity and longevity of the movement, but also contributed to the frailty of the network.

This study helps deepen our understanding of the Anti-ELAB movement. First, the scope of the movement was much larger than what we saw on streets. The mediated experience of watching live streaming sessions could be seen as a form of participation, as it enabled real-time emotional involvement and discursive participation. The audiences of MLS were peripheral yet essential participants of the protests. In other words, the movement happened in the “cyberurban space” (Lim, 2015). Second, the mobility of the movement as a strategic choice of protesters was facilitated by media technologies, especially MLS, which captured the flash mobs and spontaneous actions. The highly mobile and agile style of the protest could help evade police crackdown, but it would be less meaningful if the actions were not visible.

This study also enriches our understanding of MLS as a media technology in social movements. First and foremost, from the relational perspective, we should pay more attention to the interactions between MLS and other actors/actants. A crucial question to ask is: Who uses the technology in what kind of environment? Journalists’ use of MLS has produced distinct consequences than activists’ live streaming as in previous cases. The use could also be different in other less fluid movements, and in movements with less police violence. Second, the life cycle of MLS could be very long if the video is used to produce social media shareables. In this process, it is not only who holds the camera that matters, but also who saves and repurposes the live footage. Third, we see both external/representational and internal/organizational uses of MLS, as it has increased the visibility of the protests and mobilized participation. Fourth, it is important to examine how the business model, rules, and norms of social media platforms facilitate or impede the practice of MLS.

In terms of theoretical contributions, this study extends the line of research on the ecological perspective of social movement and media technology. First and foremost, it provides a framework that zooms in on one specific technology without losing the ecological lens. The focus on relations preserves the complexity of the environment, and the identification of the obligatory passage point helps us understand the contribution of specific actors/actants in the network. The interactions among actors/actants suggest contingency, ambiguity, and contradiction, rather than deterministic processes.

Second, in terms of the analysis of the concerned media technology, the framework proposes a three-perspective approach: infrastructure, practice, and text, followed by tracing its relation with other actors/actants. This practical approach can be widely applied to unpack other media technologies.

Third, this study adds to the ecological perspective by bringing a case of professional media taking advantage of an emerging technology. Comparing MLS by professional journalists to that by protesters as in previous social movements, we see that the involvement of professional media expanded and complicated the actor-network.

This study also contributes to the emerging literature on the role of emotions in journalism (Wahl-Jorgensen, 2020). As a journalistic format that highlights immediacy, rawness, and unfiltered information, MLS is strong in encouraging emotional involvement of the audiences. Interactive features, including emoji reactions and live comments, further facilitate affective participation, which co-produces the final product of this new journalistic format.

One important limitation of this study is that I did not interview street protesters or the police, both of whom were important actors in the network. I relied on the interpretations of journalists and audience members to analyze their agency. Nevertheless, this study contributes to the study of digital technology, social movements, and journalism by providing a useful framework and a holistic but also focused analysis of a recent major social movement. It focuses on both the production and consumption of media content, thus connecting the key processes in the movement. Future studies could adopt this framework to investigate more emerging social movements, media technologies, and journalistic practices in an ever-complex world.

Data Availability

Due to the political sensitivity of the research topic, the data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Calvin Yixiang Cheng and Jichen Fan for research assistance, and to the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their helpful comments. The author is also indebted to all the interviewees who shared their experiences and reflections.