-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lianshan Zhang, Eun Hwa Jung, Time counts? A two-wave panel study investigating the effects of WeChat affordances on social capital and well-being, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 28, Issue 1, January 2023, zmac030, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac030

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Drawing from the social capital framework and socioemotional selectivity theory, this study examines how individuals’ future time perspective (FTP) alters their social capital processes, which further influences their well-being. A two-wave survey was conducted across WeChat users possessing different FTPs. The findings showed that bonding and bridging social capital accumulation were attributed to differential WeChat affordances, which in turn exerted disparate influences on individuals’ positive affect and psychological well-being. Importantly, multigroup analyses revealed that future-oriented users were more fulfilled from the broadcasting affordance, whereas present-oriented users derived more emotional gains from the association affordance. Notably, frequent engagement with the reviewability affordance was found to diminish WeChat bonding social capital only for those who possessed open-ended FTP. The findings contribute to theoretical knowledge of social media affordances and provide practical implications for social media developers in harnessing social media to improve users’ well-being across lifespans by considering their priority of social goals.

Lay Summary

As the most popular mobile social media platform in China, WeChat plays a key role in influencing individuals’ well-being. Nevertheless, given the diverse functions concurrently available on WeChat, it is hard to tell which specific usage is beneficial or harmful to individuals’ well-being, and by what means. In addition, do people in different life stages prefer or seek different social interactions on WeChat? Do such differences change the effects of WeChat usage over time? Analysis of the survey data collected at two-time points revealed that users who perceived their future as relatively limited obtained more social bonding and then more positive affect by engaging with the Like and Comment features on WeChat. For users who believed their future was expansive, they felt more fulfilled by broadcasting on WeChat (as social bridging). However, constantly viewing others’ posts on WeChat was found to reduce social bonding only for users who perceived their future as long and vast. This study provides meaningful insights into why social media usage can lead to various psychological outcomes from different time perspectives. The findings also contribute to social media design that helps individuals reap benefits from social media use and ultimately improve their well-being.

Social media platforms are woven into the fabric of people’s daily lives across generations. As of the third quarter of 2021, WeChat remained the most popular mobile social media platform in China (Statista, 2022), providing a plethora of functionalities and services (e.g., social networking, mini programs). The enhanced features afforded by WeChat have expanded people’s range and scope of social interaction via various types of communication activities (e.g., status updates, private messaging). This makes WeChat well suited to social capital accumulation, which may further influence individual well-being across generations. However, prior research investigating the relationship between social media use (e.g., Facebook, WeChat) and well-being outcomes has yielded mixed results (for a review, see Valkenburg, 2022).

The inconclusive results from previous research revealed several gaps. First, the majority of extant research has treated social media as a relatively monolithic entity and thus broadly measured the social media use as a whole (i.e., time duration, intensity, and use vs. nonuse) without distinguishing between the affordances that are concurrently available (Kim & Shen, 2020). Such simplistic measures restrict firmer conclusions and limit theoretical understanding of the implications of social media usage since people may use social media differently to pursue unique goals. Hence, this study examines social media usage through the lens of affordances, which are action possibilities that interface features provide for certain interactions (Norman, 1999). Second, although a growing number of studies have paid attention to the influence of specific social media use on well-being, most of these studies relied on young users, such as adolescents and college students (Valkenburg, 2022), even though older adults have increasingly used social media in recent years. Social media users should not be approached as a uniform group, considering that the needs and priorities of individuals differ at different life stages in terms of social communication (Carstensen, 1998). Third, instead of directly influencing it, social media may bring about changes to well-being through crucial mediators, such as social capital (Chen & Li, 2017). Furthermore, extant studies have predominately used cross-sectional data, which makes the causality of social media use and psychosocial outcomes equivocal and controversial, highlighting the necessity of longitudinal research.

Therefore, drawing from the social capital framework (Putnam, 2000), this study examines the relationship between WeChat affordances and individual well-being, focusing on the crucial mediators of bonding and bridging social capital. Additionally, considering potential age-related differences in social communication and responding to the call for a “causal effect heterogeneity” approach (Valkenburg, 2022), this study employs two-wave panel data to examine the moderating role of age-related future time perspective (FTP) on the relationship between WeChat affordances and psychosocial outcomes of social capital and well-being in light of socioemotional selectivity theory (SST; Carstensen, 1998) and the contemporary uses and gratifications (U&G) perspective (Katz et al., 1974; Smock et al., 2011). In doing so, this study potentially contributes to the theoretical framework of U&G by integrating a lifespan theory of the social motivation of SST and shedding light on the root causes of various outcomes concerning social media usage. Practically, the findings can provide useful guidelines for harnessing social media affordances for well-being improvement.

Literature review

Examining WeChat interactions from an affordance approach

The term “affordances” is broadly conceptualized as opportunities for action constituted by the relation between technology capabilities and groups of actors (Hutchby, 2001; Majchrzak et al., 2013). Considering affordance as a bridging concept that conceptually links the objective materiality of technologies and subjective actor agency, numerous studies have applied an affordance approach in understanding human–computer interaction and its subsequent outcomes involving a wide range of media technologies (e.g., Evans et al., 2017; Majchrzak et al., 2013; Treem & Leonardi, 2013). Bucher and Helmond (2018) epitomize that the trajectory of an affordance approach tends to focus either on “an abstract high-level” or “a more concrete feature-oriented low-level” (p. 239). They demonstrated that researchers who adopt a low-level or design-oriented notion of affordances explicate affordances through specific and concrete material features located in the medium (e.g., Postigo, 2016). Moving beyond specific features, the notion of high-level affordances in social media contexts focuses on the high-level abstractions of dynamic and relational patterns of practices enabled by media platforms (e.g., Majchrzak et al., 2013). To further advance affordances research in communication scholarship, Nagy and Neff (2015) proposed the concept of imagined affordances to address the complexity of cognitive and emotional processes in the relationship among users, designers, and the digital materiality of technologies. Despite various affordances (e.g., association, visibility, editability) having been introduced to account for the complex relationships between human agency and the materiality of technologies, researchers applying the high-level framework share the commonality of emphasizing the value of the affordance lens to contextualize their findings in relation to higher-level patterns of human–technology interactions (as opposed to the idiosyncratic features of a particular technology) to better elucidate the mechanisms behind the investigated relationships (Ellison & Vitak, 2015).

In adopting an affordance approach to examining WeChat interaction and its associated outcomes, this study did not aim to take a stand on low-level or high-level affordances. On the one hand, an approach involving high-level affordances can provide analytical value concerning the relationality of a given technology and actors and delineate a general framework for the dynamic mechanism shaped by human–technology interactions (Ju et al., 2019). On the other hand, examinations of the material features of a given platform (e.g., WeChat’s voice call) help attribute the action possibilities to specific features that users enact or to specific agential actions. Considering this, a growing body of research tends to employ a high-level understanding of affordances that takes into account specific features to understand the underlying processes (Bucher & Helmond, 2018; Ju et al., 2019; Treem & Leonardi, 2013). Hence, following such an integration view, this study seeks to examine what affordances are enabled by which specific features on the WeChat platform in transforming seemingly isolated feature use into meaningful and analytical constructs to understand underlying relational processes among technological properties, agential actions, and subsequent outcomes.

Furthermore, as an all-in-one “super-sticky mega-platform” (Chen et al., 2018, p. 15), WeChat has integrated multifarious services and opens to extendable affordances as well as externally available applications, penetrating the social, political, and economic lives of ordinary people. In the broader context of platformization (Helmond, 2015; Poell et al., 2021), WeChat exhibits its capacity of penetrating into the rest of the digital ecosystem as well as internalizing external data and software services. For example, WeChat is now home to over 4.3 million mini programs (an app-in-app functionality) across e-commerce, health, news, and more (Graziani, 2021), offering an infinite number of opportunities for action. In light of this, the action possibilities rendered by WeChat are not only structured by the socio-technical nature of the platform but also constantly shaped by and adapted to dynamic patterns of practices involving both human and nonhuman agency (e.g., algorithms) across the boundaries of platforms (Bucher & Helmond, 2018). This indicates that a more nuanced understanding of user interactions on the platform of WeChat should take a relational and variable view of the entanglement between technology and actors due to WeChat’s programmable and extendable infrastructure, pointing to the necessity of adopting the affordance approach in the context of platformization.

WeChat affordances in social capital processes

The literature on social capital has identified two distinct types of social capital—bonding and bridging—which are primarily derived from strong-tie and weak-tie relationships, respectively (Putnam, 2000). Three components are crucial for sustaining and advancing bonding social capital: (a) strong in-group mutual trust (exclusive), (b) substantive emotional and psychological support, and (c) specific or direct reciprocity. As for bridging social capital, three key components are essential: (a) outward-looking (inclusive), (b) access to a broader range of people and diverse perspectives, and (c) diffuse or generalized reciprocity among a broader community (Putnam, 2000; Williams, 2006). Conceptualizing social capital as the resources and social benefits (e.g., trust, norms of reciprocity) derived from social relations (Putnam, 2000), inadequate studies on this topic have identified specifically what type of resources (e.g., bonding, bridging) people perceive as more or less accessible in relation to different affordances on the WeChat platform in Chinese and longitudinal contexts. Hence, in line with scholarship on social capital and social media affordances (Burke et al., 2011; Ellison & Vitak, 2015), this study proposed four affordances (i.e., association, dyadic interaction, broadcasting, and reviewability) influencing bonding and bridging social capital processes over time.

Association affordance in bonding and bridging social capital processes

Social media afford associations within the social network via (a) linking individuals to one another to indicate an explicit relationship between two people and/or (b) directly associating users with the content posted by their social ties to display those who interact with a social tie’s postings (Treem & Leonardi, 2013). Treem and Leonardi (2013) suggested several social media features that afford association, including Comment, Like, and tag (e.g., @) buttons that display direct messages and activities among network members.

The association affordance has the potential to enhance social capital through several theoretical mechanisms. First, establishing associations with others through a more directed form of communication, such as giving feedback or replying to others, can boost a sense of reciprocity (Ellison et al., 2014b), a critical component of social capital (Putnam, 2000). Second, considering that engagement with the association affordance is simultaneously visible to the receiver’s and sender’s mutual friends on WeChat, WeChat users’ association-based activities (e.g., Like, Comment) are a reliable and explicit way of publicly declaring friendship in the presence of mutual friends, functioning as “public displays of connection” (Donath & boyd, 2004). Such avowal behavior can increase the receiver’s feelings of inclusion and inform the receiver of the relationship strength with the sender, fostering their connection. More importantly, this association-based activity offers users additional opportunities to interact with their common friends, given the inherent context collapse on social media. This helps broaden actors’ access to bridging and latent ties and facilitates “second-degree connections,” which are critical for the formation of bridging social capital (Ellison et al., 2014a, p. 1109).

Nevertheless, unlike Facebook, WeChat is a less public and more mobile-based platform in which the majority of user connections is limited to the social network that is tied to users’ mobile contact lists, and thus, the visibility of user association-based activities is lower than is the case with Facebook or Twitter (Shen & Gong, 2019). For instance, Harwit (2017) articulated that WeChat is a “person-to-small-group” communication tool mainly used to enhance trusted contacts among familiar users (p. 312). Ju et al. (2019) indicated that dual migrants primarily used the association affordance on WeChat to build solidarity with their close-ties relationships (e.g., family, workmates). Accordingly, it seems that the association affordance on WeChat has more to do with a user’s bonding than bridging social capital, which suggests our first hypothesis:

H1: Frequent engagement with the association affordance on WeChat is a stronger predictor of bonding social capital than bridging social capital.

Dyadic interaction affordance in bonding and bridging social capital processes

As a powerful messaging tool, WeChat affords users private and intensive dyadic communication. The dyadic interaction affordance provides users with the opportunity to communicate with a specific individual with in-depth and personalized messages (Bazarova & Choi, 2014; Burke et al., 2011). Private messaging (e.g., sending text and photos) and voice/video calls are typical features of WeChat that accomplish dyadic interaction.

One-to-one communication enabled by the dyadic interaction affordance is likely to be rich in content and modalities, given the high bandwidth, which allows for more intimate dialogue. Media richness theory (Daft & Lengel, 1986) demonstrates that a richer form of communication (e.g., instant messaging, video call) allows richer information exchanges involving a high variety of cues (verbal, audio, and facial). Such rich exchanges of verbal and nonverbal cues can thus provide higher levels of self-disclosure and foster intimate relationships. Along with social penetration theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973), more intimate self-disclosure with a great amount of private and in-depth information exchange on a more personal level can result in closer relationships. Hence, it is apparent that engaging in dyadic interactions on WeChat is conducive to bonding social capital accumulation.

Although geographically dispersed weak ties may also engage in private dyadic communication, the frequency of such communication and the depth of exchange are not comparable to interactions involving strong ties. Following Markus’s (1994) rational actor perspective, people tend to make strategic choices in selecting media channels based on the characteristics of the channels and goals of communication. For example, studies have found that voice-based CMC (e.g., voice chat rooms) and video-based communication are deemed more appropriate for getting companionship and emotional support compared to text-only-based CMC, and thus, are more preferred by people communicating with significant others (e.g., Xie, 2008). Applying the above reasoning to the WeChat platform, this study assumes that people frequently engaging in dyadic interactions accumulate more bonding than bridging social capital on WeChat. Accordingly, this study postulates the following:

H2: Frequent engagement with the dyadic interaction affordance on WeChat is a stronger predictor of bonding social capital than bridging social capital.

Broadcasting affordance in bonding and bridging social capital processes

Broadcasting allows users to quickly expand the range of information diffusion to a wide range of intended audiences in the social media context (Ellison & Vitak, 2015). Scholars have identified several features affording broadcasting, including status updating, photo posting, video posting, and related features providing possibilities for broadcasting in networked publics (Vitak & Ellison, 2013).

Engaging the broadcasting affordance in publicly revealing personal information to others is noted as self-disclosure (Bazarova & Choi, 2014). The public statements of one’s daily life and personal feelings on social media intentionally reveal one’s thoughts and cues for needs. Most importantly, such disclosures usually invite comments and other forms of interaction to derive social benefits (e.g., social validations, social support; Bazarova & Choi, 2014). This can make the message poster more aware of others’ attentiveness and offer them perceptions of greater access to a diverse and responsive network (Ellison et al., 2014b). Even though sometimes the content of broadcasted messages on social media is just a mundane expression of activities that may not spur active responses, the sharing of personal observations and interpretations of daily events helps maintain social connections, primarily through the process of saying something more than having something to say (Tong & Walther, 2011).

However, as noted by social penetration theory, relational intimacy develops from relatively shallow, nonintimate levels to deeper, more intimate levels along with an increasing level of intimate information exchanges (Altman & Taylor, 1973). Although broadcasting is conducive to information mobilization, the self-disclosure of personal information on social media largely functions as a kind of small talk of informal superficial or peripheral information that usually follows the standards of social desirability and norms of appropriateness (Bazarova, 2012). Individuals’ concerns pertaining to privacy, impression, and identity management were also found to inhibit their public disclosure of highly intimate and deep personal information that is vital for relationship intimacy and social bonding (Dienlin & Metzger, 2016). Hence, this study expects that the use of the broadcasting affordance would have a stronger relationship with bridging than bonding social capital on WeChat, and thus posits the following hypothesis:

H3: Frequent engagement with the broadcasting affordance on WeChat is a stronger predictor of bridging social capital than bonding social capital.

Reviewability affordance in bonding and bridging social capital processes

On most social media platforms, individuals can rapidly and easily access other people’s updates and their communication patterns through a stream of recently updated content via social ties, such as WeChat’s Moments and Facebook’s News Feed. Such streams have been considered “social awareness streams” (Naaman et al., 2010) providing individuals with social monitoring through the reviewability affordance (Wagner et al., 2014). Reviewability on WeChat can be achieved through browsing WeChat friends’ profiles and checking out others’ past activities (e.g., status updates) and communication activities on Moments. Additionally, being noted as a “second layer of network” (Shen & Gong, 2019, p. 21), WeChat groups provide rich resources for information consumption. As such, checking out posted information (e.g., links, videos, documents) and conversations among WeChat group members also embody the reviewability affordance.

Reviewing the digital footprints of social ties functions as a form of social monitoring, which can increase social media users’ pervasive awareness (Hampton, 2016) or ambient awareness (Levordashka & Utz, 2016) of their social environment and accumulates social media users’ knowledge of their network of friends. Such heightened awareness processes supported by the reviewability affordance can increase people’s familiarity with the overall social environment and help build a cognitive representation of “who-knows-what” in their social networks (Leonardi, 2015). Furthermore, by observing social exchanges and interactions, such as how others respond to common friends’ posts in the form of liking, sharing, and commenting, the reviewability affordance enables users to obtain knowledge of “who-knows-whom” (Hampton, 2016; Leonardi, 2015), informing them of their social structure (e.g., density) and the characteristics of ties (e.g., tie strength), as well as overlapped social contacts and potential connections. Such metaknowledge allows people to identify broader resources in their networks and contributes to their perceptions of bridging social capital that can be accessed and motivated.

However, reviewability-based activities do not involve both parties directly. For example, WeChat does not inform a user when their Moments and profiles have been viewed and by whom. Without a targeted interaction that signals one’s attention and the value placed on a given relationship, it would be difficult to form specific reciprocity or foster intimacy (Donath, 2007), which are essential for bonding social capital accumulation (Putnam, 2000). Therefore, we expect that WeChat user engagement with the reviewability affordance is more beneficial for cultivating bridging than bonding social capital by proposing the following hypothesis:

H4: Frequent engagement with the reviewability affordance on WeChat is a stronger predictor of bridging social capital than bonding social capital.

Mediating role of social capital in predicting well-being

Along with cumulative studies that have evidenced the relationship between social media affordances and social capital, another line of research has lent credence to the relationship between social capital and individual well-being (e.g., Chan, 2018; Chen & Li, 2017). Well-being is a multidimensional concept. Prior literature has revealed two essential facets of well-being: positive affect and psychological well-being tapping different pursuits of a good life. Positive affect concerns hedonically positive feelings (e.g., happiness, joy, contentment) that can be induced by both physical and psychological pleasures (Huta & Ryan, 2010). Moving beyond the pursuit of hedonic experiences, psychological well-being was proposed to reflect a more complex perspective on well-being highlighting one’s functioning and full development of one’s potential, such as purpose in life and personal growth (Diener et al., 2010; Ryff, 1989).

Given the theoretically different dimensions of individual well-being, examining one dimension of well-being may obscure the differential effects of distinct types of social capital on the dimensions of well-being. As such, this study examined the mediating role of social capital linking WeChat affordances with well-being by considering different well-being niches, namely positive affect and psychological well-being. As hypothesized above (H1–H4), each affordance has its superiority in accumulating a particular type of social capital. Accordingly, the indirect effects of WeChat affordances on individual well-being are supposed to be disparate by the mediation of distinct types of social capital, which suggests the following hypotheses:

H5: The effect of frequent engagement with the WeChat association affordance on individuals’ (a) positive affect and (b) psychological well-being is stronger by the mediation of bonding social capital than bridging social capital.

H6: The effect of frequent engagement with the WeChat dyadic interaction affordance on individuals’ (a) positive affect and (b) psychological well-being is stronger by the mediation of bonding social capital than bridging social capital.

H7: The effect of frequent engagement with the WeChat broadcasting affordance on individuals’ (a) positive affect and (b) psychological well-being is stronger by the mediation of bridging social capital than bonding social capital.

H8: The effect of frequent engagement with the WeChat reviewability affordance on individuals’ (a) positive affect and (b) psychological well-being is stronger by the mediation of bridging social capital than bonding social capital.

Moderating role of the FTP

To reconcile and explain prior inconsistent findings, it is also important to consider the role of users’ inner needs and motivations in altering the outcomes of social media usage given users’ active role in selecting platform features to fulfill their social and psychological needs (Smock et al., 2011). Theoretically, a lifespan theory of social motivation—SST—contends that individuals in different life stages place different values and priorities in pursuing social or emotional goals because of their age-associated shift in time perspective (Carstensen et al., 1999). SST demonstrates that when time is perceived as open-ended, as it typically is for younger adults, people are strongly motivated to prioritize knowledge-related and future-oriented goals with long-term payoffs (e.g., establishing new social ties for career networking). By contrast, when time is conceived as limited, as it typically is for older adults who are increasingly aware of constraints on time, people tend to prioritize present-oriented goals that are associated with achieving short-term rewards to optimize emotional gratification and positive affect (e.g., seeking emotional gains from close ties; Lang & Carstensen, 2002).

According to the U&G perspective, individuals’ value priorities influence not only how media and its functions are selected and used but also the effects of media use, as the user’s activity plays a central role in the effects process (Rubin, 2002). By extending time perspective–related social goal selections to social media usage, prioritizing social interaction with strong ties/weak ties should make a difference not only in their social media usage patterns but also in the development of the bonding and bridging social capital derived from strong and weak ties, respectively. Put differently, future-oriented individuals who prioritize information and knowledge goals may benefit more from certain social media affordances (e.g., broadcasting) in accumulating bridging social capital, which offers them preferred social resources embedded in large and heterogeneous networks outside their close social spheres. By contrast, present-oriented individuals who prefer emotional goals may derive more benefits from specific social media affordances (e.g., dyadic interaction, association) in augmenting bonding social capital, which is the primary source of emotional gains they appreciate. Aligning with this argument, a recent WeChat study has documented the moderating role of users’ chronological age in developing emotional well-being from the perspective of SST (Rui et al., 2021). Despite the theoretical reasoning, to our best knowledge, no empirical study has extended SST to examine the influence of time perspectives on the relationships among WeChat affordances, social capital, and well-being. Thus, the following research question is proposed to investigate the moderating role of FTP:

RQ1: To what extent would the FTP moderate the relationships among WeChat affordances, social capital, and well-being?

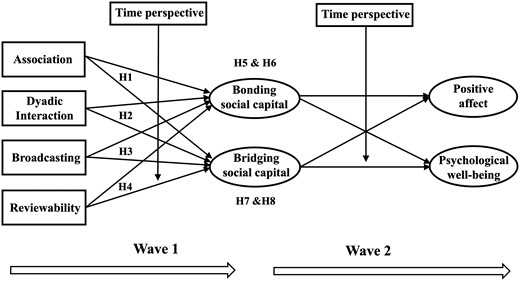

Juxtaposing all hypotheses and the research question, Figure 1 illustrates our hypothesized model.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Upon approval of the institutional review board, a two-wave longitudinal online survey in China was conducted by employing a professional survey company in China, namely Wenjuan. The two-wave data were collected between January and May 2020. To ensure a better representation of the Chinese population, quota sampling was employed by considering the population’s income (by five quintiles) and gender ratios (male vs. female) based on the most recent census data (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020). For the recruiting process, participants were randomly selected from the survey company’s panels until the number of required participants for each quota was saturated. Considering the insufficient number of older WeChat users (aged 55 years and above) on online panels in China, the income ratio for older users was not strictly requested.

A total of 1,418 respondents participated in the Wave 1 survey, with a completion rate of 27.79%. After excluding invalid questionnaires, a valid sample of 1,202 respondents was obtained. Based on previous studies in social media research (e.g., Lee et al., 2020) and due to practical considerations (e.g., attrition issues), this study chose a time lag of 3 months between the two waves. Within this timeframe, this study was able to maintain a low attrition rate in the second wave, which is beneficial for maintaining representative and valid data (Chen & Li, 2017). A total of 740 valid responses were collected for the Wave 2 survey, with a retention rate of 61.56%. Supplementary Table 1 shows detailed descriptive statistics for both waves.

Measures

All variables were assessed using multiple-item scales adapted from pre-validated measures. The following variables were measured with a 7-point Likert scale.

WeChat affordances

In light of the theoretical framework of high-level affordances and the integration view in social media contexts (Bucher & Helmond, 2018), a given affordance typically can be actualized through a set of material features that enable users to engage in activities, serving a shared function. In other words, the enactment of sets of features embodies affordances, and affordances are possible actions linked to features (Treem & Leonardi, 2013). Given the limited research identifying the specific technological features reflecting different high-level affordances on WeChat, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on 18 frequently performed WeChat activities was conducted to abstract the underlying WeChat affordances (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin = .94; Bartlett’s test of sphericity, χ2(153) = 11552.138, p < .001). The EFA with oblique rotation yielded four factors with 15 items (three items were dropped because they failed to meet the factor purity criteria), together accounting for 69.86% of the variance (see Supplementary Table 2). Given the EFA results, the following context describes the measures of WeChat affordances employed in further analyses.

Association affordance

Following prior research (Treem & Leonardi, 2013), participants were asked to report their frequency of engaging with association-based activities on WeChat (e.g., Like, Comment) (1= very infrequently, 7 = very frequently). The 5-item scale of the association affordance was reliable for both Wave 1 (α = .91) and Wave 2 (α = .92).

Dyadic interaction affordance

Dyadic interactions provide users with the possibility of interacting with a specific person individually, which is typically reflected in one-to-one interactions (Burke et al., 2011). Hence, participants were asked to report their frequency of engaging in three WeChat activities affording dyadic interaction (Wave 1: α = .82; Wave 2: α = .82).

Broadcasting affordance

The broadcasting affordance enables users to quickly disseminate content across one’s entire network. As in previous studies (Burke et al., 2011; Vitak & Ellison, 2013), participants were asked to report their frequency of engaging with three broadcasting activities on WeChat (Wave 1: α = .80; Wave 2: α = .81).

Reviewability affordance

The reviewability affordance enables users to access and review content after it has been posted. Guided by previous research (Sutcliffe et al., 2011), participants were asked to estimate their frequency of using four reviewability-based activities on WeChat (Wave 1: α = .84; Wave 2: α = .85).

Bonding and bridging social capital on WeChat

To examine the degree to which participants perceived that they had access to social bond resources (e.g., emotional support, trust) derived from their social connections on WeChat, nine items were adapted from the Internet Social Capital Scales ([ISCS], Williams, 2006) for bonding social capital (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; Wave 1: α = .84; Wave 2: α = .86). Similarly, to estimate the extent to which participants perceived that they had access to a wide variety of people and heterogeneous resources on WeChat (e.g., diverse worldviews, a broader community), nine items were adapted from the ISCS for bridging social capital (Wave 1: α = .86; Wave 2: α = .84). See all the measured items for the latent variables in Supplementary Table 3.

Positive affect

According to prior research (Diener, 2010), respondents were asked to report how frequently they had experienced positive emotions (e.g., happiness, joyfulness) in the past four weeks (1 = never, 7 = always). The 6-item scale of positive affect was reliable for both Wave 1 (α = .93) and Wave 2 (α = .93).

Psychological well-being

To examine to what extent participants can realize their true potential and find meaning in their lives, this study adopted a brief 8-item summary measure of psychological well-being devised by Diener et al. (2010). Respondents were asked to report their level of agreement with eight statements concerning the meaningfulness and various important domains of their functioning (Wave 1: α = .89; Wave 2: α = .88).

Future time perspective

To examine to what extent participants perceive the amount of time they have left relative to their current and future circumstances, a 10-item scale of FTP was adapted from Lang and Carstensen’s (2002). Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they thought the following statements were true for them: (1) Many opportunities await me in the future. (2) I expect that I will set many new goals in the future. (3) My future is filled with possibilities. (4) Most of my life lies ahead of me. (5) My future seems infinite to me. (6) I could do anything I want in the future. (7) There is plenty of time left in my life to make new plans. (8) I have the sense time is running out. (9) There are only limited possibilities in my future. (10) As I get older, I begin to experience that time as limited. The FTP scale was reliable for both Wave 1 (α = .87) and Wave 2 (α = .88). To answer RQ1, following reported procedures of using this continuous variable for group comparison (Lang & Carstensen, 2002), the scale was first transformed into T scores (M = 50), with values above 50 denoting a more open-ended time perspective and values below 50 indicating a more limited time perspective. Based on the T scores, a tercile split of the FTP scores was created for three groups of participants with limited (lower third; M = 37.24, SD = 7.05; Mage = 53.08, SD = 11.02), indefinite (middle third; M = 51.38, SD = 3.06; Mage = 43.96, SD = 13.61), and open-ended (upper third; M = 62.23, SD = 2.64; Mage = 35.42, SD = 11.90) time perspectives.

Control variables

A host of covariates were measured, including time spent on WeChat, WeChat network size, physical health, major life events, and demographic variables.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis: WeChat affordances

To verify that the four types of WeChat affordances derived from EFA are legitimately distinct, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted by using Wave 2 data (N = 740) following scholars’ recommendation of using different datasets for EFA and CFA (Thompson, 2004). The CFA model for the four factors revealed a very good model fit: χ2(84) = 322.56, p < .001, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.049, .058] (see Supplementary Table 3). Considering the frequency of using affordances as a formative factor rather than a reflective factor (Bollen & Lennox, 1991), for further analyses, scales for each affordance were created by averaging the ratings of a set of activities enabled by the respective affordances.

Full measurement model

The full measurement model was conducted with all latent variables, including both waves, simultaneously using the lavaan package in R. As recommended for longitudinal data analyses with structural equation modeling, the error terms of the same item measured at two measurement occasions were not constrained (Little et al., 2007). For model test statistics, the chi-square test was provided but not used as a primary criterion to judge the model fit because it tests the exact-fit hypothesis which is sensitive to large sample sizes (Kline, 2015). Consistent with the widely accepted combinational rules based on the two-index presentation strategy suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) , this study regards the cut-off good fit should be (a) TLI or CFI ≥ .95, and SRMR ≤ .08, or, alternatively, (b) RMSEA < .05 and SRMR < .06. The full measurement model with eight latent variables showed acceptable model fit: χ2(1898) = 3428.35, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI [.031, .035], SRMR = .04 (see Supplementary Table 4).

Longitudinal measurement invariance

To interpret the panel model with latent variables validly, metric invariance must be established (Little et al., 2007). The results showed that metric invariance (Δχ2(28) = 65.54, p < .001; ΔCFI = −.002; ΔRMSEA = .000) and scalar invariance were established (Δχ2(28) = 93.95, p < .001; ΔCFI = −.003; ΔRMSEA = .001) following the widely used criteria that the changes in CFI are smaller than a cut-off point of −.010 and the changes in RMSEA are smaller than a cutpoint of .015 (Chen, 2007). See Supplementary Table 5 for a summary of the results of the longitudinal measurement invariance.

Structural model

Following previous literature, cross-lagged models and an autoregressive analytic approach were employed to examine the causal relationships among WeChat affordances, social capital, and well-being (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Little et al., 2007). Considering the complexity of our hypothesized structural model, prior to running the structural model analysis, item parcels were used as indicators, following a balancing approach that has been commonly employed in prior research (e.g., Trepte & Reinecke, 2013). Three parcels for each latent variable were created, resulting in a total of 24 item parcels for T1 and T2 endogenous variables.

Consistent with our independent variables, we employed Wave 1 scores of the control variables in the statistical models. Among the control variables, only those significantly related to endogenous variables at the bivariate level were included in the model. Bivariate correlations between all variables are presented in Supplementary Table 6. The initial model had an acceptable model fit: χ2(468) = 1504.28, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [.061, .067], SRMR = .06. However, a set of controls was not significantly associated with social capital and well-being outcomes. Hence, to produce a parsimonious model, these nonsignificant paths were pruned. The re-specified model showed a better fit: χ2(344) = 1040.91, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.047, .055], SRMR = .05 The chi-square difference test revealed that the re-specified model was improved significantly: Δχ2(124) = 463.37, p < .001.

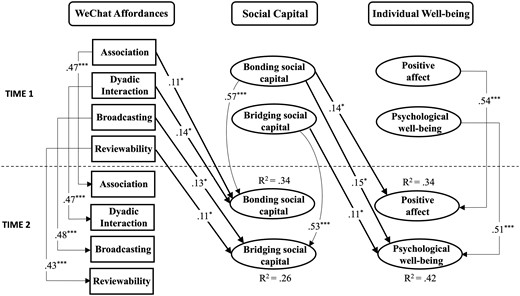

As illustrated in Figure 2, the association affordance was positively associated with bonding social capital (β = .11, p < .05) but not with bridging social capital (β = .04, p = .31), supporting H1. As predicted, frequent dyadic interaction was positively associated with bonding social capital (β = .14, p < .01) but not with bridging social capital (β = .07, p = .12), supporting H2. The broadcasting affordance positively predicted bridging social capital at a later time (β = .13, p < .05), but not for bonding social capital (β = .01, p = .78), rendering support for H3. Engaging more with the reviewability affordance improved bridging social capital (β = .11, p < .05) but not bonding social capital (β = −.02, p = .68); hence, H4 was supported. Furthermore, bonding social capital significantly improved individuals’ positive affect (β = .14, p < .05) and psychological well-being (β = .15, p < .05); while bridging social capital exerted a positive influence only on psychological well-being (β = .11, p < .05) and not on positive affect (β = .05, p = .36).

Final cross-lagged model examining the relationships between WeChat affordances, bonding social capital, bridging social capital, and two dimensions of well-being.

Note. Values reflect standardized coefficients. Rectangles reflect manifest variables, and ovals reflect latent variables. Paths in bold indicate cross-lagged effects. For clarity, error terms, covariances, control variables, and nonsignificant paths are not shown. The curve lines between two waves of bonding social capital and bridging social capital were used just for clarity.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Regarding the mediation effects (H5–H8), as summarized in Supplementary Table 7, the results revealed that bonding social capital significantly mediated the effect of the association affordance on positive affect (95% CI [.006, .031]) and psychological well-being (95% CI [.005, .030]), but not bridging social capital. Similarly, bonding social capital significantly mediated the effects of engaging in dyadic interaction on positive affect (95% CI [.009, .038]) and psychological well-being (95% CI [.006, .037]), but not bridging social capital. Hence, H5 and H6 were supported. However, frequent engagement with broadcasting (95% CI [.008, .037]) and reviewability (95% CI [.005, .034]) exerted significant indirect effects on the participants’ psychological well-being through bridging social capital but not bonding social capital. Nevertheless, there was no significant mediation effect of bridging social capital linking the reviewability affordance and positive affect (95% CI [−.005, .019]). Therefore, H7 was supported, but H8 was partially supported.

Multigroup analysis

Prior to multigroup analysis, the metric invariance across groups was checked and established given the satisfactory model fit: χ2(704) = 1207.55, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.049, .059], and the CFI and RMSEA did not decrease substantially than the fit of the baseline model (χ2(672) = 1144.062, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.048, .059]): ΔCFI = .002, ΔRMSEA = .000 (Chen, 2007).

In congruence with the independent variables, Wave 1 FTP scores were employed in the multigroup analysis. The freely estimated multigroup model using the grouping variable of time perspective fit the data at a satisfactory level: χ2(1032) = 1686.37, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.046, .054]. As shown in Table 1, the results revealed that participants who perceived their future as restricted obtained significantly more WeChat bonding social capital from the association affordance than participants who had an open-ended FTP (βlimited = .23, p < .01; βopen-ended = .05, p = .66): Δχ2(1) = 4.42, p < .05. In addition, the relationship between frequent broadcasting and bridging social capital (βopen-ended = .31, p < .001; βindefinite = .09, p = .25; βlimited = .03, p = .71) was significantly different between participants who had an open-ended FTP and those with a limited perspective: Δχ2(1) = 5.80, p < .05. Such a path was also significantly different between users with open-ended FTP and those with indefinite FTP: Δχ2(1) = 4.33, p < .05. Intriguingly, the reviewability affordance significantly weakened only future-oriented users’ perceived bonding social capital on WeChat (βopen-ended = −.12, p < .05; βindefinite = .06, p = .32; βlimited = .07, p = .29). This path was statistically different from that of participants who perceived their future as limited: Δχ2(1) = 3.91, p < .05, and those with indefinite FTP: Δχ2 (1) = 4.14, p < .05. Additionally, the results revealed that the positive effect of bridging social capital on psychological well-being was significantly stronger for future-oriented users (βopen-ended = .25, p < .01) than present-oriented users (βlimited = .02, p = .83): Δχ2(1) = 4.66, p < .05.

A multigroup analysis predicting social capital and individual well-being by FTPs

| . | Path coefficient β . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Open-ended (n = 239) . | Indefinite (n = 285) . | Limited (n = 216) . |

| Association → Bonding social capital | .05 | .06 | .23** |

| Dyadic interaction → Bonding social capital | .15* | .13* | .21** |

| Broadcasting → Bonding social capital | .08 | .03 | −.10 |

| Reviewability → Bonding social capital | −.12* | .06 | .07 |

| Association → Bridging social capital | .06 | .09 | .03 |

| Dyadic interaction → Bridging social capital | .07 | .11* | .04 |

| Broadcasting → Bridging social capital | .31*** | .09 | .03 |

| Reviewability → Bridging social capital | .10 | .12* | .11 |

| Bonding social capital → Positive affects | .11 | .17* | .12* |

| Bonding social capital → Psychological well-being | .13* | .13* | .21* |

| Bridging social capital → Positive affects | .08 | .04 | .01 |

| Bridging social capital → Psychological well-being | .25** | .11* | .02 |

| . | Path coefficient β . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Open-ended (n = 239) . | Indefinite (n = 285) . | Limited (n = 216) . |

| Association → Bonding social capital | .05 | .06 | .23** |

| Dyadic interaction → Bonding social capital | .15* | .13* | .21** |

| Broadcasting → Bonding social capital | .08 | .03 | −.10 |

| Reviewability → Bonding social capital | −.12* | .06 | .07 |

| Association → Bridging social capital | .06 | .09 | .03 |

| Dyadic interaction → Bridging social capital | .07 | .11* | .04 |

| Broadcasting → Bridging social capital | .31*** | .09 | .03 |

| Reviewability → Bridging social capital | .10 | .12* | .11 |

| Bonding social capital → Positive affects | .11 | .17* | .12* |

| Bonding social capital → Psychological well-being | .13* | .13* | .21* |

| Bridging social capital → Positive affects | .08 | .04 | .01 |

| Bridging social capital → Psychological well-being | .25** | .11* | .02 |

Note. The numbers are standardized estimates. The numbers in bold indicate that the differences between the groups are significant.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

A multigroup analysis predicting social capital and individual well-being by FTPs

| . | Path coefficient β . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Open-ended (n = 239) . | Indefinite (n = 285) . | Limited (n = 216) . |

| Association → Bonding social capital | .05 | .06 | .23** |

| Dyadic interaction → Bonding social capital | .15* | .13* | .21** |

| Broadcasting → Bonding social capital | .08 | .03 | −.10 |

| Reviewability → Bonding social capital | −.12* | .06 | .07 |

| Association → Bridging social capital | .06 | .09 | .03 |

| Dyadic interaction → Bridging social capital | .07 | .11* | .04 |

| Broadcasting → Bridging social capital | .31*** | .09 | .03 |

| Reviewability → Bridging social capital | .10 | .12* | .11 |

| Bonding social capital → Positive affects | .11 | .17* | .12* |

| Bonding social capital → Psychological well-being | .13* | .13* | .21* |

| Bridging social capital → Positive affects | .08 | .04 | .01 |

| Bridging social capital → Psychological well-being | .25** | .11* | .02 |

| . | Path coefficient β . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Open-ended (n = 239) . | Indefinite (n = 285) . | Limited (n = 216) . |

| Association → Bonding social capital | .05 | .06 | .23** |

| Dyadic interaction → Bonding social capital | .15* | .13* | .21** |

| Broadcasting → Bonding social capital | .08 | .03 | −.10 |

| Reviewability → Bonding social capital | −.12* | .06 | .07 |

| Association → Bridging social capital | .06 | .09 | .03 |

| Dyadic interaction → Bridging social capital | .07 | .11* | .04 |

| Broadcasting → Bridging social capital | .31*** | .09 | .03 |

| Reviewability → Bridging social capital | .10 | .12* | .11 |

| Bonding social capital → Positive affects | .11 | .17* | .12* |

| Bonding social capital → Psychological well-being | .13* | .13* | .21* |

| Bridging social capital → Positive affects | .08 | .04 | .01 |

| Bridging social capital → Psychological well-being | .25** | .11* | .02 |

Note. The numbers are standardized estimates. The numbers in bold indicate that the differences between the groups are significant.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

Through a two-wave longitudinal design across WeChat users with different time perspectives, this study uncovered four distinct affordances on WeChat and provided a more granular view of the specific links among these affordances, distinct social capital, and well-being dimensions. More importantly, this study identified the moderating role of age-related FTP in the process of employing WeChat affordances in developing social capital and well-being. Compared to users who perceived their future as open-ended and those who had an indefinite time perspective, users who perceived their future as limited primarily engaged in the association affordance to directly establish connections toward close social ties on WeChat to maximize their emotional gains. By contrast, it appears that for WeChat users who perceived their future as long and nebulous, the more they engaged in the broadcasting affordance to make conscious investments in widening their networks, the more heterogeneous resources and novel knowledge they obtained from the broader community they sustained. Such findings extend SST’s theoretical principles in social capital processes in a mobile social media context and highlight the crucial role of users’ psychological needs and goal orientations in social media usage, which matter in distinct forms of social capital accrual. Following this logic, this study further found that open-ended users, compared to other users perceiving a more limited time perspective, felt more fulfilled by their greater perceptions of bridging social capital accumulated on WeChat. This finding is consistent with prior SST studies focusing on offline social networking (e.g., Lang & Carstensen, 2002), and it is reasonable, as individuals typically experience greater psychological needs satisfaction when they obtain gains matching their goal hierarchy (Baltes & Carstensen, 1996). Despite the aforementioned disparate findings, dyadic interaction was found to contribute to the accumulation of WeChat bonding social capital across users with different FTPs.

Unexpectedly, an exclusive finding was revealed only among users who perceived their future as long and vast: the more they engaged in reviewability-based activities, the less bonding social capital they perceived on WeChat. This finding may be due to certain age-related characteristics. For example, studies have documented that because of a “positivity bias” on social media (Ziegele & Reinecke, 2017), frequent reviewability activities such as browsing WeChat Moments tend to magnify individuals’ social comparison tendencies and feelings of jealousy (Burke et al., 2020), which may hinder the development of in-group solidarity and sense of belongingness, attenuating their perceptions of bonding social capital. Importantly, the tendency to engage in social comparison has been found to decrease with age (Burke et al., 2020; Callan et al., 2015). Accordingly, the detrimental effect of reviewability-based activities on bonding social capital was found to be more pronounced among users with open-ended FTP, who were typically younger. Having said this, we did not directly examine the role of upward social comparison in the relationship between the reviewability affordance and bonding social capital, which could be a meaningful direction for future research.

Theoretical implications

This study proffers several theoretical implications. First, it is among the first to extensively examine diverse WeChat features to uncover distinct affordances and transform seemingly isolated feature usage into analytical constructs to elucidate the underlying processes. Identifying four distinct affordances on WeChat extends affordance scholarship to a mobile social media platform in a Chinese context. In this regard, this study challenges the traditional U&G approach that examines U&G by treating a medium as a whole and reinforces the necessity of disaggregating social media platforms into their constituent affordances and examining distinctive gratifications derived from those affordances (Sundar & Limperos, 2013).

Second, by building theoretical links between specific affordances carrying distinct functionalities with different forms of social capital processes, this study argues against a general statement of the effects of social media usage without considering the specific affordances with which users engage. It would also be misleading to conclude that media technology as a whole is beneficial or detrimental to one’s psychosocial well-being. Future research should thus focus on specific user engagement with a given affordance to unpack the conditions under which social media platform has a positive or negative effect on one’s well-being.

Third, upon prior studies that applied SST in social media contexts, indicating different network compositions and media use with increasing age (e.g., Chan, 2018; Chang et al., 2015), the current study moves a step further by extending SST to the online social capital and well-being framework by integrating its theoretical postulations with the affordance approach in examining online social capital and well-being processes. The finding that the same affordance can lead to differential outcomes among users with different prioritized goals reinforces Evans et al.’s (2017) demonstration that an affordance can remain relatively the same for more than one actor yet carry different goals and outcomes, bolstering both the functional and relational aspects of affordances (Hutchby, 2001). On the one hand, such findings dispute technology determinism, which solely emphasizes the material aspects of technology in examining media effects. On the other hand, by using a theoretical predictor to tap into user social psychology across generations, this study adds to the media effects literature by spotlighting the role of goal-oriented actors or user agency (e.g., motivations, selections) in shaping the outcomes of social media affordances.

Last, extant research that applied SST predominantly used chronological age to examine age-related differences in media usage. However, in light of SST, many observed age-related changes in emotion, cognition, and behavior are attributed to a function of developmental needs or intrinsic motivations that are adaptive across life stages and are caused by the perceived time left in life (Carstensen, 1998). Therefore, this study contributes to methodological knowledge by providing a meaningful way to measure age-related differences in future research.

Practical implications

This study provides several practical implications for social media design. First, considering the positive influence of the association affordance on bonding social capital, particularly for users with a limited time perspective, social media designers can allow users to “privilege” certain social ties (e.g., family members) or design algorithms to make privileged persons’ updates that carry more emotional stimuli more visibly prominent in their streams. Such designs can offer more motivational elements for users with a limited FTP to engage with the association affordance in order to fortify relationships.

Second, given that a dyadic interaction affordance providing richer multimodality communication is crucial in enhancing bonding social capital and well-being for all users in our study, WeChat and other social media platforms should harness voice-based and video-based features offering greater social presence and synchronous conversation to facilitate more in-depth and meaningful communication. Third, given the positive implications of broadcasting for bridging social capital and psychological well-being among users with future-oriented minds, implementing more broadcasting-based features, such as rating and recommendation, would benefit open-ended users by facilitating diverse views and heterogeneous information exchanges within their networks.

Lastly, considering that reviewability affordances appear detrimental to open-ended users’ bonding social capital processes, social media interface designers could employ more advanced filters such as content-based filters or filters of feedback counts for viewers (Burke et al., 2020) to offer end-users a favorable social environment to avoid eliciting potential negative feelings.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Several limitations warrant attention and future research. First, this study chose a 3-month lag following previous research (e.g., Lee et al., 2020) to avoid a high attrition rate that may generate bias in data validity and representation integrity. Although prior research indicates that substantive psychological changes can be observed within this timeframe (Dormann & Griffin, 2015) , the predictive effects of WeChat affordances on social capital and well-being outcomes may reflect an ongoing process of cumulative effects; therefore, future research may consider choosing longer or shorter time intervals or a multiwave design to check whether the study findings are sensitive to different time lags. Second, the effect sizes in our research models were relatively small. Nonetheless, the predictive effects in the longitudinal context controlled for autoregressive effects, which removed a large proportion of the variance in the outcome (Adachi & Willoughby, 2015). Hence, the small effects are deemed meaningful as they predicted changes in levels of the outcomes over time in a 3-month interval, especially as there are strong stability effects in our outcome variables (ranging from .51 to .57). Third, although this study controlled for a set of potential confounders and the autoregressive effects, it should be noted the potential influence of the existing stock of social capital (T1) on WeChat use (T2) at a later time. Additionally, the findings from our longitudinal study are not immune against an unmeasured third variable that may account for or influence the investigated relationships.

Fourth, although this study employed quota sampling in an attempt to proportionally represent the Chinese population, not all Chinese adults had a chance to participate in our surveys. The interpretation of our results should note the potential selection bias, and future research is recommended to employ probability sampling to ensure a broader generalization. Furthermore, in line with prior social media studies (e.g., Chen & Li, 2017; Ellison et al., 2014a), this study employed psychometric measures of social capital that examine users’ perceived access to social capital. This is conceptually different from one’s actual possession of social capital typically captured through either egocentric (e.g., position generator) or complete network analysis tapping into individuals’ social-structural resources that exist in social networks. Thus, it is essential to note the significant differences between one’s perceived and actual possession of social capital, which may exert potentially varying influences on well-being.

It is also worth considering the distinct characteristics of the WeChat platform which may shape the relationships under investigation. For example, certain content may be posted or removed on WeChat with careful self- or platform-imposed censorship that is invisible to end-users (e.g., viewers). Such “hidden affordances” structured by designed algorithms (Nagy & Neff, 2015) or self-surveillance (e.g., privacy settings) can make a difference in the possibilities and types of content rendered by the reviewability and broadcasting affordances, which may further obscure the relationships between such affordances and social capital as well as well-being outcomes. In addition, human–technology interaction on WeChat is situated in a complex ecology of platformization, which is characterized by programmable infrastructures and opens to extendable and adaptive affordances (Bucher & Helmond, 2018; Helmond, 2015). This indicates a contextual and ever-evolving relationality between technology and actors. Hence, the findings derived from this study are not conclusive but rather a heuristic for future research to take steps toward a more granular understanding of the entanglement of technology and groups of actors.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight that the existence of an affordance does not guarantee or determine certain consequences across contexts and user populations. Identifying the moderating role of FTP, which can alter how users reap benefits from WeChat affordances, contributes to a more nuanced knowledge of individuals’ social media practices driven by varying social goal orientations. That said, this study draws attention to future research endeavors to avoid examining the implications of affordances uniformly for all user groups, as certain effects may cancel each other out when users are simply examined as a whole. To this end, this study sheds light on future scholarship on affordances and the associated psychosocial outcomes across lifespans.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at Journal of Computer-mediated Communication.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This research was supported by National University of Singapore under the Graduate Research Support Scheme; Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality [grant number 22692191400]; and Shanghai Pujiang Program [grant number 22PJC062].

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the reviewers and editors for valuable comments and suggestions and to Dr. Cho Hichang (National University of Singapore) for the helpful feedback on an early version of this manuscript.