-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

James A Karlowsky, Mark G Wise, Meredith A Hackel, David A Six, Tsuyoshi Uehara, Denis M Daigle, Daniel C Pevear, Greg Moeck, Daniel F Sahm, Cefepime–taniborbactam activity against antimicrobial-resistant clinical isolates of Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: GEARS global surveillance programme 2018–22, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 79, Issue 12, December 2024, Pages 3116–3131, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkae329

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Taniborbactam is a boronate-based β-lactamase inhibitor in clinical development in combination with cefepime.

Cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator broth microdilution MICs were determined for patient isolates of Enterobacterales (n = 20 725) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 7919) collected in 59 countries from 2018 to 2022. Taniborbactam was tested at a fixed concentration of 4 mg/L. Isolates with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs ≥ 16 mg/L underwent WGS. β-Lactamase genes were identified in additional meropenem-resistant isolates by PCR/Sanger sequencing.

Taniborbactam reduced the cefepime MIC90 value for all Enterobacterales from >16 to 0.25 mg/L (>64-fold). At ≤16 mg/L, cefepime–taniborbactam inhibited 99.5% of all Enterobacterales isolates; >95% of isolates with MDR and ceftolozane–tazobactam-resistant phenotypes; ≥ 89% of isolates with meropenem-resistant and difficult-to-treat-resistant (DTR) phenotypes; >80% of isolates with meropenem–vaborbactam-resistant and ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant phenotypes; 100% of KPC-positive, 99% of OXA-48-like-positive, 99% of ESBL-positive, 97% of acquired AmpC-positive, 95% of VIM-positive and 76% of NDM-positive isolates. Against P. aeruginosa, taniborbactam reduced the cefepime MIC90 value from 32 to 8 mg/L (4-fold). At ≤16 mg/L, cefepime–taniborbactam inhibited 96.5% of all P. aeruginosa isolates; 85% of meropenem-resistant phenotype isolates; 80% of isolates with MDR and meropenem–vaborbactam-resistant phenotypes; >70% of isolates with DTR, ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant and ceftolozane–tazobactam-resistant phenotypes; and 82% of VIM-positive isolates. Multiple potential mechanisms of resistance, including carriage of IMP, or alterations in PBP3 (ftsI), porins (decreased permeability) and efflux (up-regulation) were present in most isolates with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs ≥ 16 mg/L.

Cefepime–taniborbactam exhibited potent in vitro activity against Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa, and inhibited most carbapenem-resistant isolates, including those carrying serine carbapenemases or NDM/VIM MBLs.

Introduction

Taniborbactam is a novel bicyclic boronic acid-based, transition state analogue that reversibly and covalently inhibits serine β-lactamases (Ambler class A, C and D β-lactamases), including KPC and OXA-48-like carbapenemases, and that competitively inhibits substrate binding to MBLs (Ambler class B β-lactamases), including NDM, VIM, SPM and GIM, but not IMP.1–4 An investigational combination of cefepime, a fourth-generation cephalosporin and taniborbactam has completed Phase 3 clinical development for the treatment of adult patients with complicated urinary tract infection, including acute pyelonephritis.5 A second Phase 3 clinical trial is planned to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cefepime–taniborbactam in adults with ventilated hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (NCT06168734).6

The current study assessed the in vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparators against a global collection of clinical isolates of Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa collected from 2018 to 2022 as part of the Global Evaluation of Antimicrobial Resistance via Surveillance (GEARS) programme, characterized the activity of cefepime–taniborbactam against phenotypic and genotypic resistance isolate subsets, and defined resistance mechanisms in isolates with elevated MICs to cephalosporins, carbapenems and cefepime–taniborbactam.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates

Enterobacterales (n = 20 725) and P. aeruginosa (n = 7919) cultured from patients with community- and hospital-associated infections in 336 sites in 59 countries across five geographic regions (Asia/South Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Middle East/Africa and North America) from 2018 to 2022 were collected and shipped to IHMA (Schaumburg, IL, USA) where their identities (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online) were confirmed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). Isolates were limited to one per patient per year.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

MICs were determined using the CLSI broth microdilution reference method.7 Taniborbactam was supplied by Venatorx Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Malvern, PA, USA) and tested at a fixed concentration of 4 mg/L with cefepime.8 Other agents were purchased from commercial sources. Broth microdilution panels were prepared at IHMA using CAMHB (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) and stored at −70°C until the day of testing. MICs for approved agents were interpreted using 2023 CLSI8 and EUCAST9 breakpoints. Cefepime–taniborbactam MICs against both Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa were interpreted using provisional breakpoints of ≤16 mg/L (susceptible) and >16 mg/L (resistant).10 MDR and difficult-to-treat-resistant (DTR)11 isolate definitions are provided in Table S2.

WGS

Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa with cefepime–taniborbactam MIC values of ≥16 mg/L underwent WGS (Tables S2 and S3). Among the 153 of 20 725 (0.7%) Enterobacterales that met this criterion, 47 (30.7%), 45 (29.4%), 33 (21.6%) and 28 (18.3%) isolates, respectively, had cefepime–taniborbactam MICs of 16, 32, 64 and >64 mg/L. Among the 560 of 7919 (7.1%) P. aeruginosa that met this criterion, 284 (50.7%), 63 (11.3%), 28 (5.0%), 58 (10.4%) and 127 (22.7%), respectively, had cefepime–taniborbactam MICs of 16, 32, 64, 128 and >128 mg/L. Three P. aeruginosa isolates collected in 2021 that tested with cefepime–taniborbactam MIC values ≥ 16 mg/L were not available for sequencing. Additionally, 30 isolates that originally tested with elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MIC values but upon retesting displayed MIC values < 16 mg/L were subjected to WGS.

β-Lactamase characterization via PCR and Sanger sequencing

Eight hundred thirty-three Enterobacterales isolates inhibited by cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤8 mg/L and concurrently meropenem-resistant (CLSI criteria)8 and 945 randomly selected meropenem non-resistant isolates that concurrently tested with cefepime and/or ceftazidime MIC values ≥ 2 mg/L were surveyed for their β-lactamase gene content by PCR and Sanger sequencing (Table S2). P. aeruginosa isolates with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs of ≤8 mg/L that were meropenem-resistant (CLSI criteria; n = 1211)8 as well as 100 randomly selected 2018 and 2021 meropenem non-resistant P. aeruginosa, testing with ceftazidime and/or cefepime MIC values ≥ 16 mg/L, also underwent β-lactamase gene PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Results

Enterobacterales: phenotype analysis

Among the 20 725 tested isolates of Enterobacterales, the cefepime–taniborbactam MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.06 and 0.25 mg/L, respectively, and 99.5% of isolates were inhibited by cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L (Table 1). The addition of taniborbactam reduced the cefepime MIC90 value by >64-fold (from >16 to 0.25 mg/L).

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacteralesa

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 99.5 | NAd | 0.5 | 99.5 | NA | 0.5 |

| Cefepimec | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 84.2 | NA | 15.8 | 76.8 | 4.4 | 18.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | ≤0.12 | 0.5 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 | >16 | ≤0.03 to >16 | 75.2 | 2.3 | 22.5 | 71.0 | 4.2 | 24.8 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 0.5 | 8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 87.0 | 2.3 | 10.7 | 87.0 | NA | 13.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 83.7 | 0.9 | 15.4 | 83.7 | NA | 16.3 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.06 | >8 | ≤0.004 to >8 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 97.3 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.7 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 95.3 | 1.1 | 3.6 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | ≤4 | 128 | ≤4 to >128 | 80.4 | 4.1 | 15.6 | 80.4 | NA | 19.6 |

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 99.5 | NAd | 0.5 | 99.5 | NA | 0.5 |

| Cefepimec | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 84.2 | NA | 15.8 | 76.8 | 4.4 | 18.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | ≤0.12 | 0.5 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 | >16 | ≤0.03 to >16 | 75.2 | 2.3 | 22.5 | 71.0 | 4.2 | 24.8 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 0.5 | 8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 87.0 | 2.3 | 10.7 | 87.0 | NA | 13.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 83.7 | 0.9 | 15.4 | 83.7 | NA | 16.3 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.06 | >8 | ≤0.004 to >8 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 97.3 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.7 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 95.3 | 1.1 | 3.6 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | ≤4 | 128 | ≤4 to >128 | 80.4 | 4.1 | 15.6 | 80.4 | NA | 19.6 |

aThe 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales were cultured from patients with community- and hospital-associated infections in 336 sites in 59 countries across five geographic regions (Asia/South Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Middle East/Africa and North America) in the years 2018 (n = 4567), 2019 (n = 5274), 2020 (n = 3886), 2021 (n = 4100) and 2022 (n = 2898). Patient locations/wards at the time of specimen collection included (n/percent of total): general medicine (6985/33.7%); medical ICU (4285/20.4%); general surgery (2505/12.1%); ICU surgery (2003/9.7%); emergency room (1721/8.3%); paediatric ICU (1412/4.7%); general ICU (984/4.8%); general paediatric (669/3.2%); and other/no location given (685/3.3%).

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible and % resistant values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≥32 mg/L, respectively.

cFor cefepime, susceptible values by CLSI breakpoints include isolates with both susceptible (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L) and susceptible-dose dependent (MIC 4 and 8 mg/L) MICs.

dNA, not applicable.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacteralesa

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 99.5 | NAd | 0.5 | 99.5 | NA | 0.5 |

| Cefepimec | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 84.2 | NA | 15.8 | 76.8 | 4.4 | 18.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | ≤0.12 | 0.5 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 | >16 | ≤0.03 to >16 | 75.2 | 2.3 | 22.5 | 71.0 | 4.2 | 24.8 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 0.5 | 8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 87.0 | 2.3 | 10.7 | 87.0 | NA | 13.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 83.7 | 0.9 | 15.4 | 83.7 | NA | 16.3 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.06 | >8 | ≤0.004 to >8 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 97.3 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.7 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 95.3 | 1.1 | 3.6 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | ≤4 | 128 | ≤4 to >128 | 80.4 | 4.1 | 15.6 | 80.4 | NA | 19.6 |

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 99.5 | NAd | 0.5 | 99.5 | NA | 0.5 |

| Cefepimec | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 84.2 | NA | 15.8 | 76.8 | 4.4 | 18.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | ≤0.12 | 0.5 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 | >16 | ≤0.03 to >16 | 75.2 | 2.3 | 22.5 | 71.0 | 4.2 | 24.8 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 0.5 | 8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 87.0 | 2.3 | 10.7 | 87.0 | NA | 13.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 83.7 | 0.9 | 15.4 | 83.7 | NA | 16.3 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.06 | >8 | ≤0.004 to >8 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 | 71.6 | 4.2 | 24.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 97.3 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 97.6 | NA | 2.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.7 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 95.3 | 1.1 | 3.6 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | ≤4 | 128 | ≤4 to >128 | 80.4 | 4.1 | 15.6 | 80.4 | NA | 19.6 |

aThe 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales were cultured from patients with community- and hospital-associated infections in 336 sites in 59 countries across five geographic regions (Asia/South Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Middle East/Africa and North America) in the years 2018 (n = 4567), 2019 (n = 5274), 2020 (n = 3886), 2021 (n = 4100) and 2022 (n = 2898). Patient locations/wards at the time of specimen collection included (n/percent of total): general medicine (6985/33.7%); medical ICU (4285/20.4%); general surgery (2505/12.1%); ICU surgery (2003/9.7%); emergency room (1721/8.3%); paediatric ICU (1412/4.7%); general ICU (984/4.8%); general paediatric (669/3.2%); and other/no location given (685/3.3%).

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible and % resistant values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≥32 mg/L, respectively.

cFor cefepime, susceptible values by CLSI breakpoints include isolates with both susceptible (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L) and susceptible-dose dependent (MIC 4 and 8 mg/L) MICs.

dNA, not applicable.

Cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L inhibited ≥90% of Enterobacterales isolates that were resistant to each of ceftazidime, cefepime, piperacillin–tazobactam, ceftolozane–tazobactam and meropenem; >80% of isolates resistant to each of meropenem–vaborbactam and ceftazidime–avibactam; 96.2% of MDR isolates; and 89.4% of DTR isolates (Table 2). Cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L inhibited a greater percentage of isolates than ceftazidime–avibactam, meropenem–vaborbactam and ceftolozane–tazobactam for each of the nine resistance phenotypes analysed.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against clinical isolates of Enterobacterales with antimicrobial-resistant phenotypes

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial-resistant phenotype, by prevalence (no. of isolates; % of total isolates)a . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Ceftazidime-resistant (4661; 22.5%) | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.12 | 2 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 97.7 | 97.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 89.3 | 89.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 45.8 | 45.8 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 77.8 | 80.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 88.2 | 89.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 34.0 | 34.0 | |

| Cefepime-resistant (3283; 15.8%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.6 | 85.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 48.7 | 48.7 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 69.8 | 72.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 83.2 | 85.1 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 35.5 | 35.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam-resistant (3231; 15.6%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.7 | 96.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.3 | 85.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 26.6 | 26.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 66.6 | 70.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 82.5 | 84.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | — | — | |

| MDR phenotype (2730; 13.2%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | 0.015 to >64 | 96.2 | 96.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 82.2 | 82.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 33.2 | 33.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 62.2 | 65.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 79.4 | 81.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 20.3 | 20.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam-resistant (2218; 10.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 8 | 0.015 to >64 | 95.4 | 95.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 77.6 | 77.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 8 to >8 | — | — | |

| Meropenem | 1 | 64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 52.9 | 57.4 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 74.9 | 77.9 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| Meropenem-resistant (972; 4.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.6 | 89.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.4 | 54.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | — | — | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 41.9 | 48.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| DTR phenotype (939; 4.5%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.4 | 89.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 56.1 | 56.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 2 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 7.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 44.7 | 51.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant (499; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 81.4 | 81.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 8.4 | 11.2 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 20.8 | 28.3 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam-resistant (498; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 81.5 | 81.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 28.1 | 28.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 8 to >128 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial-resistant phenotype, by prevalence (no. of isolates; % of total isolates)a . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Ceftazidime-resistant (4661; 22.5%) | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.12 | 2 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 97.7 | 97.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 89.3 | 89.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 45.8 | 45.8 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 77.8 | 80.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 88.2 | 89.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 34.0 | 34.0 | |

| Cefepime-resistant (3283; 15.8%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.6 | 85.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 48.7 | 48.7 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 69.8 | 72.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 83.2 | 85.1 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 35.5 | 35.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam-resistant (3231; 15.6%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.7 | 96.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.3 | 85.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 26.6 | 26.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 66.6 | 70.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 82.5 | 84.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | — | — | |

| MDR phenotype (2730; 13.2%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | 0.015 to >64 | 96.2 | 96.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 82.2 | 82.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 33.2 | 33.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 62.2 | 65.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 79.4 | 81.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 20.3 | 20.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam-resistant (2218; 10.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 8 | 0.015 to >64 | 95.4 | 95.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 77.6 | 77.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 8 to >8 | — | — | |

| Meropenem | 1 | 64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 52.9 | 57.4 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 74.9 | 77.9 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| Meropenem-resistant (972; 4.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.6 | 89.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.4 | 54.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | — | — | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 41.9 | 48.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| DTR phenotype (939; 4.5%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.4 | 89.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 56.1 | 56.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 2 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 7.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 44.7 | 51.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant (499; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 81.4 | 81.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 8.4 | 11.2 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 20.8 | 28.3 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam-resistant (498; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 81.5 | 81.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 28.1 | 28.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 8 to >128 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

aResistant phenotypes determined using CLSI breakpoints. % of total isolates calculated as % of 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales.

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L.

cAn MDR phenotype was assigned to isolates resistant, using 2023 CLSI breakpoints,8 to at least one agent from ≥3 of the following antimicrobial agent classes: aminoglycosides (gentamicin), β-lactam combination agents (piperacillin–tazobactam, ceftazidime–avibactam, ceftolozane–tazobactam, meropenem–vaborbactam), carbapenems (meropenem or imipenem), cephems (ceftazidime, cefepime) and fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin).

dDTR isolates were identified using the definition of Kadri et al.11 as isolates intermediate or resistant, by 2023 CLSI breakpoints,8 to fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin) and all β-lactams including carbapenems and piperacillin–tazobactam, but excluding ceftazidime–avibactam, ceftolozane–tazobactam and meropenem–vaborbactam.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against clinical isolates of Enterobacterales with antimicrobial-resistant phenotypes

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial-resistant phenotype, by prevalence (no. of isolates; % of total isolates)a . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Ceftazidime-resistant (4661; 22.5%) | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.12 | 2 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 97.7 | 97.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 89.3 | 89.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 45.8 | 45.8 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 77.8 | 80.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 88.2 | 89.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 34.0 | 34.0 | |

| Cefepime-resistant (3283; 15.8%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.6 | 85.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 48.7 | 48.7 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 69.8 | 72.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 83.2 | 85.1 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 35.5 | 35.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam-resistant (3231; 15.6%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.7 | 96.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.3 | 85.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 26.6 | 26.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 66.6 | 70.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 82.5 | 84.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | — | — | |

| MDR phenotype (2730; 13.2%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | 0.015 to >64 | 96.2 | 96.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 82.2 | 82.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 33.2 | 33.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 62.2 | 65.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 79.4 | 81.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 20.3 | 20.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam-resistant (2218; 10.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 8 | 0.015 to >64 | 95.4 | 95.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 77.6 | 77.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 8 to >8 | — | — | |

| Meropenem | 1 | 64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 52.9 | 57.4 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 74.9 | 77.9 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| Meropenem-resistant (972; 4.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.6 | 89.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.4 | 54.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | — | — | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 41.9 | 48.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| DTR phenotype (939; 4.5%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.4 | 89.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 56.1 | 56.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 2 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 7.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 44.7 | 51.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant (499; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 81.4 | 81.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 8.4 | 11.2 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 20.8 | 28.3 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam-resistant (498; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 81.5 | 81.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 28.1 | 28.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 8 to >128 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial-resistant phenotype, by prevalence (no. of isolates; % of total isolates)a . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Ceftazidime-resistant (4661; 22.5%) | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 0.12 | 2 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 97.7 | 97.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 89.3 | 89.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 45.8 | 45.8 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 77.8 | 80.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 88.2 | 89.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 34.0 | 34.0 | |

| Cefepime-resistant (3283; 15.8%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.6 | 85.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 4 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 48.7 | 48.7 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 69.8 | 72.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 83.2 | 85.1 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 32 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 35.5 | 35.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam-resistant (3231; 15.6%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 96.7 | 96.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 85.3 | 85.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 26.6 | 26.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 66.6 | 70.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 82.5 | 84.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | — | — | |

| MDR phenotype (2730; 13.2%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.25 | 4 | 0.015 to >64 | 96.2 | 96.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.5 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 82.2 | 82.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 33.2 | 33.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.12 | >32 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 62.2 | 65.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 79.4 | 81.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 20.3 | 20.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam-resistant (2218; 10.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 8 | 0.015 to >64 | 95.4 | 95.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 77.6 | 77.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 8 to >8 | — | — | |

| Meropenem | 1 | 64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 52.9 | 57.4 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 74.9 | 77.9 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| Meropenem-resistant (972; 4.7%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.6 | 89.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.4 | 54.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | — | — | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 41.9 | 48.8 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| DTR phenotype (939; 4.5%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 32 | 0.015 to >64 | 89.4 | 89.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 56.1 | 56.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 2 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 7.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 44.7 | 51.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant (499; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 81.4 | 81.4 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 8.4 | 11.2 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 20.8 | 28.3 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam-resistant (498; 2.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 81.5 | 81.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 28.1 | 28.1 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 4 to >64 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 16 to >16 | — | — | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 8 to >128 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

aResistant phenotypes determined using CLSI breakpoints. % of total isolates calculated as % of 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales.

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L.

cAn MDR phenotype was assigned to isolates resistant, using 2023 CLSI breakpoints,8 to at least one agent from ≥3 of the following antimicrobial agent classes: aminoglycosides (gentamicin), β-lactam combination agents (piperacillin–tazobactam, ceftazidime–avibactam, ceftolozane–tazobactam, meropenem–vaborbactam), carbapenems (meropenem or imipenem), cephems (ceftazidime, cefepime) and fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin).

dDTR isolates were identified using the definition of Kadri et al.11 as isolates intermediate or resistant, by 2023 CLSI breakpoints,8 to fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin) and all β-lactams including carbapenems and piperacillin–tazobactam, but excluding ceftazidime–avibactam, ceftolozane–tazobactam and meropenem–vaborbactam.

Enterobacterales: genotype analysis

In total, 1931 Enterobacterales isolates were subjected to molecular testing by WGS or PCR and Sanger sequencing. Cefepime–taniborbactam (MIC50, 1 mg/L; MIC90, 16 mg/L), ceftazidime–avibactam (MIC50, 4 mg/L; MIC90, >16 mg/L) and meropenem–vaborbactam (MIC50, 16 mg/L; MIC90, >16 mg/L) inhibited 90.1%, 54.6% and 42.7%, respectively, of carbapenemase-positive isolates of Enterobacterales. Cefepime–taniborbactam inhibited 77.5% of MBL-positive isolates overall, including 95.2% of VIM-positive and 75.5% of NDM-positive isolates. Cumulative MIC distributions stratified by carbapenemase type for the 961 IMP-negative isolates of carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales (that carried a single carbapenemase) are shown in Table S4. The most active comparator, meropenem–vaborbactam, inhibited only 8.5% of MBL-positive Enterobacterales isolates.

Cefepime–taniborbactam (100% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L), ceftazidime–avibactam (94.8% susceptible) and meropenem–vaborbactam (92.7% susceptible) were active against Enterobacterales carrying KPCs (Table 3). Cefepime–taniborbactam (98.7% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L) and ceftazidime–avibactam (95.2% susceptible) were also highly active against Enterobacterales carrying OXA-48-like enzymes, while meropenem–vaborbactam was not (32.9% susceptible). Cefepime–taniborbactam (at ≤16 mg/L), ceftazidime–avibactam, meropenem–vaborbactam and meropenem inhibited ≥90% of ESBL-positive and acquired AmpC-positive isolates.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against 1931 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales with molecularly identified β-lactamase genotypes

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype (no. of isolates; % of total molecularly characterized isolates) . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Carbapenemase-positive (968; 50.1%)a | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 1 | 16 | 0.015 to >64 | 90.1 | 90.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.6 | 54.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 4.5 | 6.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 42.7 | 49.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| MBL-positive (413; 21.4%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 77.5 | 77.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.5 to >64 | 1.9 | 2.7 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 8.5 | 17.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| NDM-positive (364; 18.9%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.06 to >64 | 75.5 | 75.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 2 to >16 | 3.3 | 11.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| VIM-positive (42; 2.2%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 8 | 0.03 to 32 | 95.2 | 95.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 4 to >16 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 8 | 64 | 0.5 to >64 | 7.1 | 11.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | 0.5 to >16 | 42.9 | 52.4 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| KPC-positive (327; 16.9%)e | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 4 | 0.015 to 8 | 100 | 100 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 94.8 | 94.8 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 2.8 | 4.6 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | 4 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 92.7 | 96.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| OXA-48 group-positive (228; 11.8%)f | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 4 | 0.03 to >64 | 98.7 | 98.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | 4 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 95.2 | 95.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Meropenem | 16 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 11.8 | 18.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | 0.12 to >16 | 32.9 | 39.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 64 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| ESBL-positive (794; 41.1%)g | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.12 | 1 | 0.015 to 64 | 99.1 | 99.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 98.5 | 98.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 75.1 | 75.1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to 64 | 93.3 | 94.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 99.4 | 99.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 57.8 | 57.8 | |

| Acquired AmpC-positive (66; 3.4%)h | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 2 | 0.015 to 32 | 97.0 | 97.0 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.0 | 97.0 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 2 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.015 to 8 | 93.9 | 95.5 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to 4 | 100 | 100 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype (no. of isolates; % of total molecularly characterized isolates) . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Carbapenemase-positive (968; 50.1%)a | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 1 | 16 | 0.015 to >64 | 90.1 | 90.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.6 | 54.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 4.5 | 6.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 42.7 | 49.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| MBL-positive (413; 21.4%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 77.5 | 77.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.5 to >64 | 1.9 | 2.7 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 8.5 | 17.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| NDM-positive (364; 18.9%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.06 to >64 | 75.5 | 75.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 2 to >16 | 3.3 | 11.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| VIM-positive (42; 2.2%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 8 | 0.03 to 32 | 95.2 | 95.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 4 to >16 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 8 | 64 | 0.5 to >64 | 7.1 | 11.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | 0.5 to >16 | 42.9 | 52.4 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| KPC-positive (327; 16.9%)e | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 4 | 0.015 to 8 | 100 | 100 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 94.8 | 94.8 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 2.8 | 4.6 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | 4 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 92.7 | 96.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| OXA-48 group-positive (228; 11.8%)f | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 4 | 0.03 to >64 | 98.7 | 98.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | 4 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 95.2 | 95.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Meropenem | 16 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 11.8 | 18.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | 0.12 to >16 | 32.9 | 39.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 64 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| ESBL-positive (794; 41.1%)g | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.12 | 1 | 0.015 to 64 | 99.1 | 99.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 98.5 | 98.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 75.1 | 75.1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to 64 | 93.3 | 94.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 99.4 | 99.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 57.8 | 57.8 | |

| Acquired AmpC-positive (66; 3.4%)h | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 2 | 0.015 to 32 | 97.0 | 97.0 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.0 | 97.0 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 2 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.015 to 8 | 93.9 | 95.5 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to 4 | 100 | 100 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

aIncludes isolates with MBLs and serine carbapenemases; isolates could also possess OSBLs (original spectrum β-lactamases, e.g. TEM-1 and SHV-1), ESBLs or AmpC-type enzymes.

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L.

cIncludes isolates that possess IMP alone (n = 7), NDM alone (n = 363), VIM alone (n = 42) and NDM + IMP (n = 1).

dIsolates could also possess serine carbapenemases, ESBLs, AmpCs and/or OSBLs, but no other MBLs.

eIsolates could also possess OXA-48 group, ESBLs, AmpC-type enzymes and OSBLs but not MBLs.

fIsolates could also possess ESBLs, AmpC-type enzymes or OSBLs, but no other carbapenemases.

gIsolates could also possess AmpC-type enzymes, or OSBLs, but no carbapenemases.

hIsolates could also possess OSBLs, but no ESBLs or carbapenemases.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against 1931 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales with molecularly identified β-lactamase genotypes

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype (no. of isolates; % of total molecularly characterized isolates) . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Carbapenemase-positive (968; 50.1%)a | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 1 | 16 | 0.015 to >64 | 90.1 | 90.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.6 | 54.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 4.5 | 6.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 42.7 | 49.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| MBL-positive (413; 21.4%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 77.5 | 77.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.5 to >64 | 1.9 | 2.7 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 8.5 | 17.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| NDM-positive (364; 18.9%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.06 to >64 | 75.5 | 75.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 2 to >16 | 3.3 | 11.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| VIM-positive (42; 2.2%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 8 | 0.03 to 32 | 95.2 | 95.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 4 to >16 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 8 | 64 | 0.5 to >64 | 7.1 | 11.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | 0.5 to >16 | 42.9 | 52.4 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| KPC-positive (327; 16.9%)e | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 4 | 0.015 to 8 | 100 | 100 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 94.8 | 94.8 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 2.8 | 4.6 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | 4 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 92.7 | 96.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| OXA-48 group-positive (228; 11.8%)f | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 4 | 0.03 to >64 | 98.7 | 98.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | 4 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 95.2 | 95.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Meropenem | 16 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 11.8 | 18.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | 0.12 to >16 | 32.9 | 39.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 64 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| ESBL-positive (794; 41.1%)g | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.12 | 1 | 0.015 to 64 | 99.1 | 99.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 98.5 | 98.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 75.1 | 75.1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to 64 | 93.3 | 94.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 99.4 | 99.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 57.8 | 57.8 | |

| Acquired AmpC-positive (66; 3.4%)h | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 2 | 0.015 to 32 | 97.0 | 97.0 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.0 | 97.0 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 2 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.015 to 8 | 93.9 | 95.5 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to 4 | 100 | 100 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype (no. of isolates; % of total molecularly characterized isolates) . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Carbapenemase-positive (968; 50.1%)a | Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 1 | 16 | 0.015 to >64 | 90.1 | 90.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 4 | >16 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 54.6 | 54.6 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 4.5 | 6.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 42.7 | 49.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| MBL-positive (413; 21.4%)c | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.03 to >64 | 77.5 | 77.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.5 to >64 | 1.9 | 2.7 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 8.5 | 17.2 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| NDM-positive (364; 18.9%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 64 | 0.06 to >64 | 75.5 | 75.5 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 0.25 to >16 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | >32 | >64 | 2 to >64 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | >16 | >16 | 2 to >16 | 3.3 | 11.5 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| VIM-positive (42; 2.2%)d | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 1 | 8 | 0.03 to 32 | 95.2 | 95.2 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | >16 | >16 | 4 to >16 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | >8 to >8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 8 | 64 | 0.5 to >64 | 7.1 | 11.9 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 8 | >16 | 0.5 to >16 | 42.9 | 52.4 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 32 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| KPC-positive (327; 16.9%)e | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.5 | 4 | 0.015 to 8 | 100 | 100 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 94.8 | 94.8 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 0.5 to >8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Meropenem | 32 | >64 | 0.03 to >64 | 2.8 | 4.6 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.12 | 4 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 92.7 | 96.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| OXA-48 group-positive (228; 11.8%)f | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 2 | 4 | 0.03 to >64 | 98.7 | 98.7 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 1 | 4 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 95.2 | 95.2 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | >8 | >8 | 1 to >8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Meropenem | 16 | 64 | 0.12 to >64 | 11.8 | 18.0 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 16 | >16 | 0.12 to >16 | 32.9 | 39.0 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | >128 | >128 | 64 to >128 | 0 | 0 | |

| ESBL-positive (794; 41.1%)g | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.12 | 1 | 0.015 to 64 | 99.1 | 99.1 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 98.5 | 98.5 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 75.1 | 75.1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to 64 | 93.3 | 94.8 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to >16 | 99.4 | 99.6 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 57.8 | 57.8 | |

| Acquired AmpC-positive (66; 3.4%)h | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 2 | 0.015 to 32 | 97.0 | 97.0 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 97.0 | 97.0 | |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 2 | >8 | ≤0.25 to >8 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.015 to 8 | 93.9 | 95.5 | |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 to 4 | 100 | 100 | |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 8 | >128 | ≤4 to >128 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |

aIncludes isolates with MBLs and serine carbapenemases; isolates could also possess OSBLs (original spectrum β-lactamases, e.g. TEM-1 and SHV-1), ESBLs or AmpC-type enzymes.

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L.

cIncludes isolates that possess IMP alone (n = 7), NDM alone (n = 363), VIM alone (n = 42) and NDM + IMP (n = 1).

dIsolates could also possess serine carbapenemases, ESBLs, AmpCs and/or OSBLs, but no other MBLs.

eIsolates could also possess OXA-48 group, ESBLs, AmpC-type enzymes and OSBLs but not MBLs.

fIsolates could also possess ESBLs, AmpC-type enzymes or OSBLs, but no other carbapenemases.

gIsolates could also possess AmpC-type enzymes, or OSBLs, but no carbapenemases.

hIsolates could also possess OSBLs, but no ESBLs or carbapenemases.

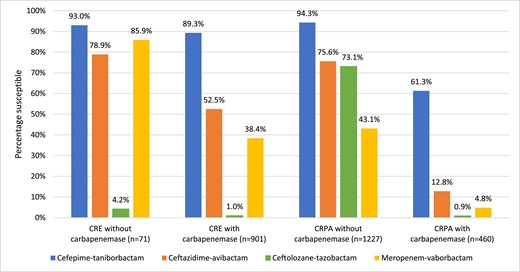

At least 92.7% (901/972) of meropenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates carried one or more carbapenemase genes detectable by the methods used (Figure 1). Against the 972 meropenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates identified in the study, cefepime–taniborbactam inhibited 37%–88% more isolates with carbapenemases (n = 901) and 7%–89% more isolates without carbapenemases (n = 71) than the other newer β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations tested. Overall, 37.1% (334/901) and 21.1% (15/71) of meropenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates with and without carbapenemases had a cefepime–taniborbactam-susceptible/ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant phenotype, respectively. Less than 80% (56/71) of meropenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates without carbapenemases were ceftazidime–avibactam-susceptible compared to 93% (66/71) for cefepime–taniborbactam.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactama and comparator agentsb against carbapenem-resistantc clinical isolates of Enterobacterales (CRE) and P. aeruginosa (CRPA) stratified by the presence and absence of molecularly identified carbapenemases. aFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L. bCLSI and EUCAST susceptible breakpoints for ceftazidime–avibactam and ceftolozane–tazobactam are harmonized. As CLSI does not publish breakpoints for meropenem–vaborbactam against P. aeruginosa, the EUCAST susceptible breakpoint is used. cCarbapenem-resistant phenotypes for Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa were based on meropenem susceptibility using CLSI 2023 breakpoints. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Enterobacterales: characterization of isolates with elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MICs

The 153 of 20 725 Enterobacterales isolates with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs ≥ 16 mg/L [47 (30.7%) of which had MIC of 16 mg/L] consisted of 93 Klebsiella pneumoniae, 36 Escherichia coli, 10 Providencia rettgeri, three Providencia stuartii, three Serratia marcescens, three Enterobacter cloacae, two Enterobacter hormaechei, two Citrobacter freundii and one Morganella morganii. Every isolate carried one or more β-lactamase genes; 89.6% of isolates carried one or more carbapenemase genes. Nearly all (104/106; 98%) Enterobacterales with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs > 16 mg/L were MDR, and only 10.6%, 7.7% and 0% of these isolates were susceptible to ceftazidime–avibactam, meropenem–vaborbactam and ceftolozane–tazobactam, respectively.

Putative explanations for elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MICs could be deduced for 91 of 93 K. pneumoniae isolates. Two isolates carried IMP-8. Eighty of the remaining 91 isolates harboured NDM in combination with other resistance factors like porin mutations that may result in decreased susceptibility. One isolate had a ftsI gene (PBP3; the primary target of cefepime) encoding a four amino acid insertion (TVPY) at position 334 and also possessed NDM-5, OXA-181 (an OXA-48-group carbapenemase) and CTX-M-15 (each within spectrum of taniborbactam). Eighty-nine of the 93 isolates (95.7%) had a porin disruption or alteration likely affecting drug entry through the outer membrane, including 76 isolates exhibiting a disruption in ompK35 (OmpF homologue) and 89 exhibiting a disruption or insertion in ompK36 (OmpC homologue) in regions of each porin known to affect permeability. Overall, 81.7% (76/93) of isolates showed disruptions or relevant insertions in both major porins. Three isolates showed a disruption in ramR, and for four isolates the gene coding for this protein appeared to be deleted. RamR, a negative regulator of RamA, is an enhancer of AcrAB efflux pump expression (and multidrug resistance) in K. pneumoniae.12

Putative factors contributing to elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MICs were identified in 34 of 36 (94.4%) E. coli isolates. Thirty-one of the 36 (86.1%) isolates (14/31 with cefepime–taniborbactam MIC of 16 mg/L and 17/31 with cefepime–taniborbactam MIC > 16 mg/L) showed four amino acid insertions (YRIN or YRIK) at position 333 in PBP3 known to negatively impact accessibility of cephalosporins and aztreonam to the transpeptidase binding site.13 Of the five remaining isolates, one had a novel four amino acid insertion ‘IPYR’ at amino acid position 331, one had a single substitution (I332V) and three exhibited wild-type ftsI. Twenty-eight isolates carried NDM. All but one of the NDM-positive isolates also possessed one of the aforementioned PBP3 insertions. Previous testing demonstrated that some E. coli isolates possessing these PBP3 insertions were inhibited by cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤8 mg/L, suggesting that these insertions alone should not be considered the unique basis for resistance.10 Thirty-two of the 36 isolates (88.9%) had an alteration in OmpC and/or OmpF likely resulting in reduced permeability. Genetic lesions suggestive of a non-functional protein were observed for marR (AcrAB efflux pump regulatory gene) in one isolate, marA in one isolate and acrR (another AcrAB efflux pump regulatory gene) in 20 other isolates. Table 4 summarizes the overlap of mutations in porin genes, ftsI and efflux regulatory genes in E. coli isolates with elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MICs. Nine of the 16 E. coli with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs of 16 mg/L and nine of the 20 with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs of >16 mg/L exhibited all three of the putative resistance mechanisms: porin disruption, PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation.

Occurrence and co-occurrence of putative non-β-lactamase resistance mechanisms identified in 36 isolates of E. coli with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs ≥ 16 mg/L

| . | Cefepime–taniborbactam MIC (number of isolates) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | 16 mg/L (n = 16) . | >16 mg/L (n = 20) . |

| Putative resistance mechanism(s)a . | Number of isolates (%) . | Number of isolates (%) . |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 9 (56.2) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation | 4 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption alone | 0 | 1 (5.0) |

| PBP3 sequence variation alone | 0 | 0 |

| PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| Efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| No putative resistance mechanism(s) identified | 1 (6.2) | 1 (5.0) |

| . | Cefepime–taniborbactam MIC (number of isolates) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | 16 mg/L (n = 16) . | >16 mg/L (n = 20) . |

| Putative resistance mechanism(s)a . | Number of isolates (%) . | Number of isolates (%) . |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 9 (56.2) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation | 4 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption alone | 0 | 1 (5.0) |

| PBP3 sequence variation alone | 0 | 0 |

| PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| Efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| No putative resistance mechanism(s) identified | 1 (6.2) | 1 (5.0) |

aMajor porin genes, ompC and ompF, were screened for alterations that code for a truncated, presumably non-functional protein; PBP3 sequence variation included ftsI sequences predicted to code for insertions known to reduce cefepime binding;13 and efflux up-regulation included genetic changes that likely enhance drug extrusion via AcrAB-TolC efflux pump.14

Occurrence and co-occurrence of putative non-β-lactamase resistance mechanisms identified in 36 isolates of E. coli with cefepime–taniborbactam MICs ≥ 16 mg/L

| . | Cefepime–taniborbactam MIC (number of isolates) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | 16 mg/L (n = 16) . | >16 mg/L (n = 20) . |

| Putative resistance mechanism(s)a . | Number of isolates (%) . | Number of isolates (%) . |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 9 (56.2) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation | 4 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption alone | 0 | 1 (5.0) |

| PBP3 sequence variation alone | 0 | 0 |

| PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| Efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| No putative resistance mechanism(s) identified | 1 (6.2) | 1 (5.0) |

| . | Cefepime–taniborbactam MIC (number of isolates) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | 16 mg/L (n = 16) . | >16 mg/L (n = 20) . |

| Putative resistance mechanism(s)a . | Number of isolates (%) . | Number of isolates (%) . |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 9 (56.2) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption and PBP3 sequence variation | 4 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Porin disruption alone | 0 | 1 (5.0) |

| PBP3 sequence variation alone | 0 | 0 |

| PBP3 sequence variation and efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| Efflux up-regulation | 1 (6.2) | 0 |

| No putative resistance mechanism(s) identified | 1 (6.2) | 1 (5.0) |

aMajor porin genes, ompC and ompF, were screened for alterations that code for a truncated, presumably non-functional protein; PBP3 sequence variation included ftsI sequences predicted to code for insertions known to reduce cefepime binding;13 and efflux up-regulation included genetic changes that likely enhance drug extrusion via AcrAB-TolC efflux pump.14

Among the remaining 24 Enterobacterales isolates with elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MICs, one C. freundii isolate carried an IMP-8 gene and one displayed a gross disruption in OmpF porin. Two of the E. cloacae isolates carried an IMP enzyme (IMP-4 and IMP-8). For the third isolate of E. cloacae, no clear explanation for the elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MIC was found, although the deduced PBP3 amino acid sequence showed several substitutions when compared to the reference sequence. One E. hormaechei isolate carried IMP-8, and the second isolate exhibited a ‘YRIN’ insertion in PBP3. Among the 10 P. rettgeri isolates (nine of which had a cefepime–taniborbactam MIC of ≥64 mg/L), one harboured IMP-27 and eight others NDM-1. All P. rettgeri carried at least one acquired OXA-type enzyme, and five carried a VEB-type ESBL (taniborbactam is expected to inhibit both OXA and VEB β-lactamases in addition to NDM-1).2 Two isolates of P. rettgeri showed a disruption in the gene coding for its major porin, an OmpF homologue. Unidentified concurrent resistance mechanisms must have contributed to the elevated cefepime–taniborbactam MICs in the 10 P. rettgeri isolates. The three S. marcescens isolates carried CTX-M-15 and OXA-1. Reduced susceptibility to cefepime has been linked to OXA-1 carriage in Enterobacterales.15

Enterobacterales: regional, specimen source and species analyses

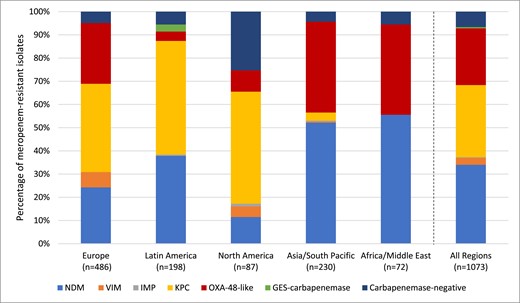

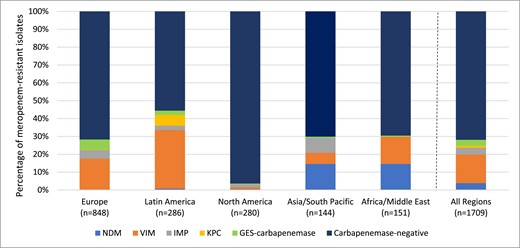

Meropenem susceptible values across the five global regions studied ranged from 98%–99% in North America to 91%–92% in Latin America (Table 5). Cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L inhibited from 98.0% (Asia/South Pacific) to 99.9% (North America) of Enterobacterales across the five global regions. NDM was the predominant carbapenemase among meropenem-resistant Enterobacterales (defined by CLSI criteria) in Asia/South Pacific and Africa/Middle East regions, while KPC was most frequent in Europe, Latin America and North America (Figure 2). Across five common specimen sources, nearly all isolates (99.3%–99.8%) had cefepime–taniborbactam MICs of ≤16 mg/L (Table S5). Cefepime–taniborbactam MIC90 values differed by up to 16-fold across the Enterobacterales species tested (Table S6).

Global region diversity of carbapenemases detected among meropenem-resistant Enterobacteralesa. aIsolates that carried multiple carbapenemases were counted for each carbapenemase type. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam, cefepime and meropenem against 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales stratified by global region of collection

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Region of collection (no. of isolates; % of total isolates) | ||||||

| Asia/South Pacific (2467; 11.9%) | Cefepime–taniborbactama | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Cefepimeb | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 79.4 | 71.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.25 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 92.1 | 92.5 | |

| Europe (8760; 42.3%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.6 | 99.6 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 83.9 | 77.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.1 | 94.8 | |

| Latin America (2331; 11.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.7 | 99.7 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 75.9 | 66.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.5 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 91.3 | 92.2 | |

| Middle East/Africa (1332; 6.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.5 | 99.5 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 73.4 | 62.9 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.4 | 95.0 | |

| North America (5835; 28.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 92.2 | 85.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 98.3 | 98.6 | |

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Region of collection (no. of isolates; % of total isolates) | ||||||

| Asia/South Pacific (2467; 11.9%) | Cefepime–taniborbactama | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Cefepimeb | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 79.4 | 71.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.25 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 92.1 | 92.5 | |

| Europe (8760; 42.3%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.6 | 99.6 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 83.9 | 77.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.1 | 94.8 | |

| Latin America (2331; 11.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.7 | 99.7 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 75.9 | 66.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.5 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 91.3 | 92.2 | |

| Middle East/Africa (1332; 6.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.5 | 99.5 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 73.4 | 62.9 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.4 | 95.0 | |

| North America (5835; 28.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 92.2 | 85.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 98.3 | 98.6 | |

aFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L.

bFor cefepime tested against Enterobacterales isolates: percent susceptible values by CLSI breakpoints include isolates with both susceptible (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L) and susceptible-dose dependent (MIC 4 and 8 mg/L) MICs.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam, cefepime and meropenem against 20 725 clinical isolates of Enterobacterales stratified by global region of collection

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Region of collection (no. of isolates; % of total isolates) | ||||||

| Asia/South Pacific (2467; 11.9%) | Cefepime–taniborbactama | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Cefepimeb | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 79.4 | 71.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.25 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 92.1 | 92.5 | |

| Europe (8760; 42.3%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.6 | 99.6 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 83.9 | 77.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.1 | 94.8 | |

| Latin America (2331; 11.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.7 | 99.7 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 75.9 | 66.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.5 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 91.3 | 92.2 | |

| Middle East/Africa (1332; 6.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.5 | 99.5 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 73.4 | 62.9 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.4 | 95.0 | |

| North America (5835; 28.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 92.2 | 85.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 98.3 | 98.6 | |

| . | . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | CLSI % susceptible . | EUCAST % susceptible . |

| Region of collection (no. of isolates; % of total isolates) | ||||||

| Asia/South Pacific (2467; 11.9%) | Cefepime–taniborbactama | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Cefepimeb | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 79.4 | 71.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.25 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 92.1 | 92.5 | |

| Europe (8760; 42.3%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.6 | 99.6 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 83.9 | 77.3 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.1 | 94.8 | |

| Latin America (2331; 11.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.7 | 99.7 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 75.9 | 66.2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.5 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 91.3 | 92.2 | |

| Middle East/Africa (1332; 6.4%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.5 | 99.5 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | >16 | ≤0.008 to >64 | 73.4 | 62.9 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 94.4 | 95.0 | |

| North America (5835; 28.2%) | Cefepime–taniborbactam | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.25 | 8 | ≤0.008 to 64 | 92.2 | 85.6 | |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | ≤0.004 to >64 | 98.3 | 98.6 | |

aFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L.

bFor cefepime tested against Enterobacterales isolates: percent susceptible values by CLSI breakpoints include isolates with both susceptible (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L) and susceptible-dose dependent (MIC 4 and 8 mg/L) MICs.

P. aeruginosa: phenotype analysis

Among the 7919 tested isolates of P. aeruginosa, 30.2/30.2% were imipenem resistant (by CLSI/EUCAST breakpoints), the cefepime–taniborbactam MIC50 and MIC90 were 2 and 8 mg/L, and 96.5% of isolates were inhibited by cefepime–taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L (Table 6). The addition of taniborbactam to cefepime reduced the MIC90 value by 4-fold (from 32 mg/L to 8 mg/L). The most active comparators against P. aeruginosa overall were ceftazidime–avibactam (89.7% susceptible), ceftolozane–tazobactam (87.6% susceptible) and meropenem–vaborbactam (85.6% susceptible by EUCAST breakpoints).

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against 7919 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosaa

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 2 | 8 | ≤0.06 to >32 | 96.5 | NAd | 3.5 | 96.5 | NA | 3.5 |

| Cefepimec | 4 | 32 | ≤0.25 to >32 | 78.4 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 78.4 | NA | 21.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 89.7 | NA | 10.3 | 89.7 | NA | 10.3 |

| Ceftazidimec | 4 | >32 | ≤0.25 to >32 | 75.8 | 4.9 | 19.3 | 75.8 | NA | 24.2 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 87.6 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 87.6 | NA | 12.4 |

| Ciprofloxacinc | 0.12 | >4 | ≤0.06 to >4 | 74.9 | 4.1 | 21.0 | 74.9 | NA | 25.1 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Imipenemc | 2 | 16 | ≤0.5 to >64 | 58.4 | 11.3 | 30.2 | 69.8 | NA | 30.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.5 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | NA | NA | NA | 85.6 | NA | 14.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.5 | >8 | ≤0.06 to >64 | 72.0 | 6.7 | 21.3 | 72.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactamc | 8 | >128 | ≤0.5 to >128 | 70.6 | 7.8 | 21.6 | 70.6 | NA | 29.4 |

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 2 | 8 | ≤0.06 to >32 | 96.5 | NAd | 3.5 | 96.5 | NA | 3.5 |

| Cefepimec | 4 | 32 | ≤0.25 to >32 | 78.4 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 78.4 | NA | 21.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 89.7 | NA | 10.3 | 89.7 | NA | 10.3 |

| Ceftazidimec | 4 | >32 | ≤0.25 to >32 | 75.8 | 4.9 | 19.3 | 75.8 | NA | 24.2 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 87.6 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 87.6 | NA | 12.4 |

| Ciprofloxacinc | 0.12 | >4 | ≤0.06 to >4 | 74.9 | 4.1 | 21.0 | 74.9 | NA | 25.1 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Imipenemc | 2 | 16 | ≤0.5 to >64 | 58.4 | 11.3 | 30.2 | 69.8 | NA | 30.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.5 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | NA | NA | NA | 85.6 | NA | 14.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.5 | >8 | ≤0.06 to >64 | 72.0 | 6.7 | 21.3 | 72.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactamc | 8 | >128 | ≤0.5 to >128 | 70.6 | 7.8 | 21.6 | 70.6 | NA | 29.4 |

aThe 7919 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa were cultured from patients with community- and hospital-associated infections in 267 sites in 57 countries across five geographic regions (Asia/South Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Middle East/Africa and North America) in the years 2018 (n = 1343), 2019 (n = 1657), 2020 (n = 1617), 2021 (n = 1800) and 2022 (n = 1502). Patient locations/wards at the time of specimen collection included (n/percent of total): general medicine (2759/34.8%); medical ICU (1887/23.8%); general surgery (742/9.4%); ICU surgery (806/10.2%); emergency room (425/5.4%); paediatric ICU (373/4.7%); general ICU (436/5.5%); general paediatric (295/3.7%); and other/no location given (196/2.5%).

bFor comparative purposes only, % susceptible and % resistant values for cefepime–taniborbactam correspond to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≥32 mg/L, respectively.

cFor cefepime, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, imipenem and piperacillin–tazobactam, percent susceptible values by EUCAST breakpoints include isolates in the susceptible, increased exposure category.

dNA, not available. Neither CLSI nor EUCAST publish MIC breakpoints for gentamicin against P. aeruginosa; CLSI does not publish MIC breakpoints for meropenem–vaborbactam tested against P. aeruginosa.

In vitro activity of cefepime–taniborbactam and comparator agents against 7919 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosaa

| . | MIC, mg/L . | MIC interpretation . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | |||||||

| Antimicrobial agent . | MIC50 . | MIC90 . | MIC range . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . | % Susceptible . | % Intermediate . | % Resistant . |

| Cefepime–taniborbactamb | 2 | 8 | ≤0.06 to >32 | 96.5 | NAd | 3.5 | 96.5 | NA | 3.5 |

| Cefepimec | 4 | 32 | ≤0.25 to >32 | 78.4 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 78.4 | NA | 21.6 |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam | 2 | 16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | 89.7 | NA | 10.3 | 89.7 | NA | 10.3 |

| Ceftazidimec | 4 | >32 | ≤0.25 to >32 | 75.8 | 4.9 | 19.3 | 75.8 | NA | 24.2 |

| Ceftolozane–tazobactam | 1 | 8 | ≤0.12 to >16 | 87.6 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 87.6 | NA | 12.4 |

| Ciprofloxacinc | 0.12 | >4 | ≤0.06 to >4 | 74.9 | 4.1 | 21.0 | 74.9 | NA | 25.1 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | >16 | ≤0.25 to >16 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Imipenemc | 2 | 16 | ≤0.5 to >64 | 58.4 | 11.3 | 30.2 | 69.8 | NA | 30.2 |

| Meropenem–vaborbactam | 0.5 | 16 | ≤0.06 to >16 | NA | NA | NA | 85.6 | NA | 14.4 |

| Meropenem | 0.5 | >8 | ≤0.06 to >64 | 72.0 | 6.7 | 21.3 | 72.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 |