-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jacqueline Findlay, Virginia C Gould, Paul North, Karen E Bowker, Martin O Williams, Alasdair P MacGowan, Matthew B Avison, Characterization of cefotaxime-resistant urinary Escherichia coli from primary care in South-West England 2017–18, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 75, Issue 1, January 2020, Pages 65–71, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz397

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from community-acquired urinary tract infections are increasingly reported worldwide. We sought to determine and characterize the mechanisms of cefotaxime resistance employed by urinary E. coli obtained from primary care, over 12 months, in Bristol and surrounding counties in South-West England.

Cefalexin-resistant E. coli isolates were identified from GP-referred urine samples using disc susceptibility testing. Cefotaxime resistance was determined by subsequent plating onto MIC breakpoint plates. β-Lactamase genes were detected by PCR. WGS was performed on 225 isolates and analyses were performed using the Center for Genomic Epidemiology platform. Patient information provided by the referring general practices was reviewed.

Cefalexin-resistant E. coli (n=900) isolates were obtained from urines from 146 general practices. Following deduplication by patient approximately 69% (576/836) of isolates were cefotaxime resistant. WGS of 225 isolates identified that the most common cefotaxime-resistance mechanism was blaCTX-M carriage (185/225), followed by plasmid-mediated AmpCs (pAmpCs) (17/225), AmpC hyperproduction (13/225), ESBL blaSHV variants (6/225) or a combination of both blaCTX-M and pAmpC (4/225). Forty-four STs were identified, with ST131 representing 101/225 isolates, within which clade C2 was dominant (54/101). Ciprofloxacin resistance was observed in 128/225 (56.9%) of sequenced isolates, predominantly associated with fluoroquinolone-resistant clones ST131 and ST1193.

Most cefalexin-resistant E. coli isolates were cefotaxime resistant, predominantly caused by blaCTX-M carriage. The correlation between cefotaxime resistance and ciprofloxacin resistance was largely attributable to the high-risk pandemic clones ST131 and ST1193. Localized epidemiological data provide greater resolution than regional data and can be valuable for informing treatment choices in the primary care setting.

Introduction

Escherichia coli that are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics, particularly to cephalosporins, represent a major global public health concern. Third-generation cephalosporins (3GCs) are used across the world to treat infections caused by E. coli [e.g. urinary tract infections (UTIs), bloodstream infections (BSIs) and intra-abdominal infections] and subsequently the emergence of resistance is particularly worrying.1 Resistance to 3GCs in E. coli can be caused by multiple mechanisms, including chromosomally encoded AmpC β-lactamase hyperproduction, and may involve increased efflux and reduced outer membrane permeability, but is predominantly attributed to the spread of plasmid-mediated ESBLs (e.g. blaCTX-M) and, to a lesser extent, plasmid-mediated AmpCs (pAmpCs; e.g. blaCMY).2,E. coli that harbour ESBLs are often co-resistant to multiple antibiotic classes and subsequently the treatment options for such infections may be limited.3

UTIs are the most common bacterial infection type in both primary and hospital care settings in the developed world4 and are associated with considerable morbidity.5 Previous studies of community-onset UTIs (CO-UTIs) in several mainland European countries found that E. coli was the most commonly isolated uropathogen, accounting for over half of all isolates (53.3%–76.7%).6–8 The incidence of CO-UTIs in the UK is difficult to determine since such infections are not reportable and most are diagnosed and treated in a primary care setting, with diagnosis often based solely upon patient symptoms rather than a positive urine culture. CO-UTIs are most often treated empirically and subsequently local epidemiological data are useful for informing treatment choice. Treatment failure for CO-UTIs, particularly in immunocompromised patients, increases the risk of the infection spreading to other sites including the bloodstream, with grave consequences.9,10

E. coli STs belonging to phylogroups B2 (STs 73, 95 and 131) and D (ST69) have been reported to be major causes of both UTIs and BSIs in the UK.11 Since its initial description in 2008, numerous studies have shown that the MDR pandemic clone, ST131, is a major cause of UTI globally.12–14 The ST131 clonal group can be broken down by population genetics into three clades based on their association with particular fimH types: A/fimH41, B/fimH22 and C/fimH30.15 Clade C can be further broken down into four subclades: C1, not usually associated with ESBL carriage, but typically fluoroquinolone resistant; C1-M27 and C1-nM27, both associated with blaCTX-M-27 carriage and fluoroquinolone resistant; and C2 (also known as H30Rx), associated with blaCTX-M-15 carriage and fluoroquinolone resistant.15,16 Studies have suggested that the global dominance of ESBL-positive ST131 is, in part, due to its increased virulence potential over its non-ST131 ESBL-positive counterparts.17,18

Although the use of cephalosporins for the treatment of UTIs is not typical in the UK, they may be used where resistance to first- and second-line treatment exists. This may select cephalosporin-resistant UTIs and, if an invasive infection occurs, empirical therapy with a 3GC is likely to fail. This study sought to use WGS to characterize the population structure and determine the mechanisms of resistance to the 3GC cefotaxime employed by urinary E. coli isolates referred from general practices in Bristol and surrounding counties in South-West England serving a population of ∼ 1.2 million people.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates, identification and susceptibility testing

Cefalexin-resistant urinary E. coli isolates were obtained from routine urine microbiology testing at Severn Infection Partnership, Southmead Hospital. Urine samples were submitted between September 2017 and August 2018 from 146 general practices located throughout Bristol and including coverage in Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire.

Bacterial identification was carried out using BD™ CHROMagar™ Orientation Medium chromogenic agar (BD, GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by disc diffusion or, in the case of colistin, by broth microdilution, and interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines.19 A single colony from cefalexin-resistant isolates was subcultured onto TBX agar plates (Sigma–Aldrich, Dorset, UK) containing 2 mg/L cefotaxime and isolates that were positive for growth were deemed cefotaxime resistant and taken forward for further molecular testing.

Screening for β-lactamase genes

Two multiplex PCRs were performed to screen for β-lactamase genes. The first was to detect blaCTX-M groups as previously described20 and the second was to detect the additional β-lactamase genes blaCMY-2-type, blaDHA, blaSHV, blaTEM and blaOXA-1 using the primers listed in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

WGS and analyses

WGS was performed by MicrobesNG (https://microbesng.uk/) on a HiSeq 2500 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using 2×250 bp paired-end reads. Reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic,21 assembled into contigs using SPAdes22 3.13.0 (http://cab.spbu.ru/software/spades/) and contigs were annotated using Prokka.23 Resistance genes, plasmid replicon types, STs and fim types were assigned using ResFinder,24 PlasmidFinder,25 MLST26 2.0 and FimTyper on the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org/) platform.

ST131 clades were identified by resistance gene carriage and fimH type and, in the case of clade C1-M27, by the presence of the prophage region M27PP1 (LC209430)16 through sequence alignment using progressiveMauve alignment software.27

MLST and resistance gene data were analysed to produce a minimum spanning tree using BioNumerics software v7.6 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

Plasmid pUB_DHA-1 assembled onto a single contig. The overlap of contig ends was confirmed by PCR and the plasmid sequence was submitted to GenBank with accession number MK048477. Reads were mapped using Geneious Prime 2019.1.3 (https://www.geneious.com).

Plasmid transformation

Transformation of plasmid extractions from isolates encoding mcr-1 and blaOXA-244 were attempted by electroporation using E. coli DH5α as a recipient. Transformants were selected, respectively, on LB agar containing 0.5 mg/L colistin, or containing 100 mg/L ampicillin with a 10 μg ertapenem disc being placed on the agar surface (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, UK). Transformants were confirmed by PCR (Table S1).

Analysis of patient demographic information

Limited, non-identifiable patient information was obtained from the request forms sent with submissions from referring general practices.

Results and discussion

Patient demographics and antimicrobial susceptibilities

E. coli is cultured from approximately two-thirds of all bacterium-positive GP-submitted urine samples processed by the Southmead Hospital laboratory, totalling ∼36 000 isolates per year. Trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin and cefalexin resistance is observed in ∼35%, 2% and ∼8% of these E. coli, respectively. If the E. coli is 3GC resistant, trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin resistance rates increase to ∼67% and ∼7%, respectively. 3GC resistance is seen in ∼72% of cefalexin-resistant E. coli.

Nine hundred cefalexin-resistant urinary E. coli isolates were collected during the period of our study. Following deduplication by patient, isolates were obtained from 836 patients. Most isolates were obtained from female patients (669/836; 80.0%) and the mean patient age was 62.4 years (median=69 years). Almost 69% (576/836) were cefotaxime resistant, which matches phenotypic laboratory data, confirming that this is a representative sample. Most cefotaxime-resistant isolates were again from females (465/576; 80.7%) and the mean patient age was 62.5 years (median=69 years). Ciprofloxacin resistance was observed in 424/836 (50.7%) of all isolates and in 363/576 (63.0%) of cefotaxime-resistant isolates.

β-Lactamase genes of interest (GOIs) detected by PCR in cefotaxime-resistant isolates

Table 1 indicates the number of cefotaxime-resistant isolates carrying each β-lactamase GOI: blaCTX-M, blaCMY, blaDHA or blaSHV. Of these, blaCTX-M genes were by far the most prevalent, found in 571/626 (91.2%) of isolates. Within these, blaCTX-M-G1 was most common (421/626), followed by blaCTX-M-G9 (149/626) and blaCTX-M-G8 (1/626). A previous study performed across four primary care trusts in England in 2013–14 estimated the carriage of CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the faeces of healthy adults to be 7.3% (range of 4.9%–16.0%), over 95% of which were E. coli.28 Based on our data above, 5.3% of GP-submitted urinary E. coli were CTX-M positive.

pAmpCs blaCMY and blaDHA were found in 13 (3 alongside blaCTX-M-G1) and 17 (4 alongside blaCTX-M-G1) isolates, respectively. blaSHV was found in 11 (3 alongside blaCTX-M-G1) isolates and the remaining 24 isolates harboured none of the GOIs as detected by PCR.

β-Lactamase genes detected by multiplex PCRs from 626 cefotaxime-resistant isolates

| Isolates (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance mechanisms identified by PCR . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-G1 . | CTX-M-G1 + DHA . | CTX-M-G1 + SHV . | CTX-M-G1 + CMY . | CTX-M-G9 . | CTX-M-G8 . | CMY . | DHA . | SHV . | none . | |

| Female (n = 507) | 334 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 123 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 20 |

| Male (n = 119) | 77 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total (626) | 411 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 149 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 24 |

| Isolates (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance mechanisms identified by PCR . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-G1 . | CTX-M-G1 + DHA . | CTX-M-G1 + SHV . | CTX-M-G1 + CMY . | CTX-M-G9 . | CTX-M-G8 . | CMY . | DHA . | SHV . | none . | |

| Female (n = 507) | 334 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 123 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 20 |

| Male (n = 119) | 77 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total (626) | 411 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 149 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 24 |

β-Lactamase genes detected by multiplex PCRs from 626 cefotaxime-resistant isolates

| Isolates (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance mechanisms identified by PCR . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-G1 . | CTX-M-G1 + DHA . | CTX-M-G1 + SHV . | CTX-M-G1 + CMY . | CTX-M-G9 . | CTX-M-G8 . | CMY . | DHA . | SHV . | none . | |

| Female (n = 507) | 334 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 123 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 20 |

| Male (n = 119) | 77 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total (626) | 411 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 149 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 24 |

| Isolates (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance mechanisms identified by PCR . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-G1 . | CTX-M-G1 + DHA . | CTX-M-G1 + SHV . | CTX-M-G1 + CMY . | CTX-M-G9 . | CTX-M-G8 . | CMY . | DHA . | SHV . | none . | |

| Female (n = 507) | 334 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 123 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 20 |

| Male (n = 119) | 77 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total (626) | 411 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 149 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 24 |

WGS analyses

GOI variants and STs

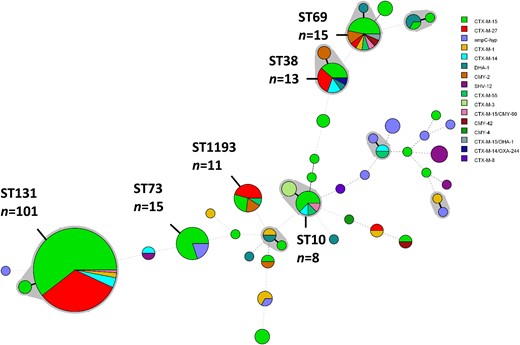

Two-hundred and twenty-five isolates, chosen to be representative of resistance gene carriage (as previously determined by PCR) and patient demographics (age, sex) obtained throughout the entire study period, were selected for WGS. Within these, 44 STs were identified, with numbers of isolates ranging from 1 to 101 representatives. ST131 was dominant (n=101), followed by STs 69 (n=15), 73 (n=15), 38 (n=13), 1193 (n=11) and 10 (n=8). The remaining 38 STs had one to four representative isolates (Figure 1). Ciprofloxacin resistance was observed in 128/225 (56.9%) of sequenced isolates, predominantly associated with fluoroquinolone-resistant clones ST131 and ST1193.

Minimum spanning tree of the MLST profiles of 225 cefotaxime-resistant E. coli isolates. The shaded areas represent SLVs. Members of the most prevalent STs (more than four representatives) are labelled and their number of representatives indicated. The diameter of the circle represents the number of isolates of that particular ST and the coloured segments indicate which cefotaxime-resistance mechanisms were identified. Thick solid lines represent SLVs, thin solid lines represent double-locus variants and dashed connecting lines indicate multilocus variants. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Cefotaxime-resistance GOIs were identified in all but 13 isolates (212/225; 94.2%). Eighty-four percent (189/225) of isolates harboured one of seven blaCTX-M gene variants (Table 2). Carriage of blaCTX-M-15 was the most common cefotaxime-resistance mechanism identified (118/189), followed by blaCTX-M-27 (44/189) and blaCTX-M-14 (10/189). Amongst the non-CTX-M GOIs, four blaCMY variants were identified; blaCMY-2 (n=7), blaCMY-4 (n=1), blaCMY-42 (n=2) and blaCMY-60 (n=3; all three being co-carried alongside blaCTX-M-15), as well as blaDHA-1 (n=8; one alongside blaCTX-M-15) and blaSHV-12 (n=6). The narrow-spectrum β-lactamases blaOXA-1, blaTEM-1 and inhibitor-resistant variant blaTEM-33 were found in 53 isolates, 82 isolates and 1 isolate, respectively.

| blaCTX-M variant . | blaCMY variant . | blaDHA variant . | blaSHV variant . | None detected . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-3 . | CTX-M-8 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CTX-M-55 . | CMY-2 . | CMY-4 . | CMY-42 . | CMY-60 . | DHA-1 . | SHV-12 . | |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 118 | 44 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 13 |

| blaCTX-M variant . | blaCMY variant . | blaDHA variant . | blaSHV variant . | None detected . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-3 . | CTX-M-8 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CTX-M-55 . | CMY-2 . | CMY-4 . | CMY-42 . | CMY-60 . | DHA-1 . | SHV-12 . | |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 118 | 44 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 13 |

Note: three isolates harboured both blaCMY-60 and blaCTX-M-15, and one isolate harboured both blaDHA-1 and blaCTX-M-15.

| blaCTX-M variant . | blaCMY variant . | blaDHA variant . | blaSHV variant . | None detected . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-3 . | CTX-M-8 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CTX-M-55 . | CMY-2 . | CMY-4 . | CMY-42 . | CMY-60 . | DHA-1 . | SHV-12 . | |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 118 | 44 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 13 |

| blaCTX-M variant . | blaCMY variant . | blaDHA variant . | blaSHV variant . | None detected . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-3 . | CTX-M-8 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CTX-M-55 . | CMY-2 . | CMY-4 . | CMY-42 . | CMY-60 . | DHA-1 . | SHV-12 . | |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 118 | 44 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 13 |

Note: three isolates harboured both blaCMY-60 and blaCTX-M-15, and one isolate harboured both blaDHA-1 and blaCTX-M-15.

AmpC-hyperproducing isolates

All thirteen (5.8%) sequenced isolates from which no cefotaxime-resistance GOI could be identified were presumed to be chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase hyperproducers because they carried mutations within the ampC promoter/attenuator region previously seen in confirmed AmpC hyperproducers (Table 3).29,30 These represented nine different STs, each having one representative, with the exceptions of the STs 75 and 200, of which there were three representatives each (Table S2). This indicates a lack of dominant clones in AmpC hyperproducers identified in this study. If we go on to assume that the 24 isolates negative for GOIs by PCR are AmpC hyperproducers, as was found with the 13 representative sequenced isolates, then 3.8% of the isolates in this study could be classed as AmpC hyperproducers. Additionally, one blaCTX-M-15-positive isolate was found to also harbour ampC promoter changes associated with hyperproduction.

Mutations found within the promoter/attenuator region of the 13 presumed AmpC-hyperproducing isolates subjected to WGS relative to E. coli MG1655 (GenBank accession number NC_000913.3)

| No. of isolates . | ampC promoter/ attenuator mutations . | Pribnow box . |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | −42C>T, −25G>A, −1C>T, +57C>T | TTGACA—17 nt—TATCGT |

| 2 | −28G>A, ins −12 T −13, +22G>T | TTGTCA—17 nt—TACAAT |

| 2 | −11C>T, ins −12 T −13, +33G>A, +36G>A | TTGTCA—17 nt—TATAAT |

| 1 | −32T>A, +34C>A, +57C>T | TTGACA—16 nt—TACAAT |

| No. of isolates . | ampC promoter/ attenuator mutations . | Pribnow box . |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | −42C>T, −25G>A, −1C>T, +57C>T | TTGACA—17 nt—TATCGT |

| 2 | −28G>A, ins −12 T −13, +22G>T | TTGTCA—17 nt—TACAAT |

| 2 | −11C>T, ins −12 T −13, +33G>A, +36G>A | TTGTCA—17 nt—TATAAT |

| 1 | −32T>A, +34C>A, +57C>T | TTGACA—16 nt—TACAAT |

ins, insertion.

Mutations found within the promoter/attenuator region of the 13 presumed AmpC-hyperproducing isolates subjected to WGS relative to E. coli MG1655 (GenBank accession number NC_000913.3)

| No. of isolates . | ampC promoter/ attenuator mutations . | Pribnow box . |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | −42C>T, −25G>A, −1C>T, +57C>T | TTGACA—17 nt—TATCGT |

| 2 | −28G>A, ins −12 T −13, +22G>T | TTGTCA—17 nt—TACAAT |

| 2 | −11C>T, ins −12 T −13, +33G>A, +36G>A | TTGTCA—17 nt—TATAAT |

| 1 | −32T>A, +34C>A, +57C>T | TTGACA—16 nt—TACAAT |

| No. of isolates . | ampC promoter/ attenuator mutations . | Pribnow box . |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | −42C>T, −25G>A, −1C>T, +57C>T | TTGACA—17 nt—TATCGT |

| 2 | −28G>A, ins −12 T −13, +22G>T | TTGTCA—17 nt—TACAAT |

| 2 | −11C>T, ins −12 T −13, +33G>A, +36G>A | TTGTCA—17 nt—TATAAT |

| 1 | −32T>A, +34C>A, +57C>T | TTGACA—16 nt—TACAAT |

ins, insertion.

Characterization of ST131 isolates

ESBLs and clades

One hundred and one ST131 isolates harboured the following cefotaxime-resistance mechanisms/alleles: blaCTX-M-1 (n=2), blaCTX-M-14 (n=4), blaCTX-M-15 (n=61), blaCTX-M-15/blaCMY-60 (n=1) and blaCTX-M-27 (n=33). The isolates were broken down into their respective clades (Table 4); ST131-C2 was dominant (54/101; 53.5%), followed by C1-M27 (23/101; 22.8%), A (11/101; 10.9%), C1-nM27 (5/101; 5.0%) and B (1/101; 1.0%), and seven isolates were unclassified. Eighty-eight percent (89/101) of isolates, and notably all clade C2 isolates, were ciprofloxacin resistant, a typical characteristic of this lineage. Two non-ST131 members of the ST131 complex, both of which were blaCTX-M-15-positive ST8313 isolates [ST8313 being a fumC single-locus variant (SLV) of ST131], also harboured the same chromosomal fluoroquinolone resistance-associated mutations in gyrA, parC and parE, as are associated with ST131/C2—suggesting this ST may be ST131/C2 derived. Previous studies have highlighted the dominance of ST131 and particularly the clade C2/H30Rx on a worldwide scale.13,14 Since its initial description in 2008 in isolates from three continents,12,13 ST131 has been reported across all inhabited continents.15 The recently described C1 subclade C1-M27, characterized by the presence of an 11 894 bp prophage-like genomic island M27PP1, was initially described in Japan in 2016 and has been reported in countries in at least three continents: Europe, Asia and North America, so far.16 The presence of C1-M27 isolates in this study indicates the expansion of this particular ST131 sublineage into the UK, similar to that which has been reported from countries in mainland Europe.31 There was no geographical clustering of C1-M27-positive isolates within our study region.

ST131 clades and cefotaxime-resistance GOI alleles harboured by 101 isolates subjected to WGS

| ST131 clade (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance allele (n) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CMY-60 . | |

| A (11) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| B (1) | 1 | ||||

| C | |||||

| C1-M27 (23) | 23 | ||||

| C1-nM27 (5) | 3 | 2 | |||

| C2 (54) | 54 | ||||

| Unclassified (7) | 4a | 3 | 1a | ||

| Total (101) | 2 | 4 | 62a | 33 | 1a |

| ST131 clade (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance allele (n) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CMY-60 . | |

| A (11) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| B (1) | 1 | ||||

| C | |||||

| C1-M27 (23) | 23 | ||||

| C1-nM27 (5) | 3 | 2 | |||

| C2 (54) | 54 | ||||

| Unclassified (7) | 4a | 3 | 1a | ||

| Total (101) | 2 | 4 | 62a | 33 | 1a |

One isolate belonging to an ST131 unclassified clade harboured both blaCTX-M-15 and blaCMY-60.

ST131 clades and cefotaxime-resistance GOI alleles harboured by 101 isolates subjected to WGS

| ST131 clade (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance allele (n) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CMY-60 . | |

| A (11) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| B (1) | 1 | ||||

| C | |||||

| C1-M27 (23) | 23 | ||||

| C1-nM27 (5) | 3 | 2 | |||

| C2 (54) | 54 | ||||

| Unclassified (7) | 4a | 3 | 1a | ||

| Total (101) | 2 | 4 | 62a | 33 | 1a |

| ST131 clade (n) . | Cefotaxime-resistance allele (n) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 . | CTX-M-14 . | CTX-M-15 . | CTX-M-27 . | CMY-60 . | |

| A (11) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| B (1) | 1 | ||||

| C | |||||

| C1-M27 (23) | 23 | ||||

| C1-nM27 (5) | 3 | 2 | |||

| C2 (54) | 54 | ||||

| Unclassified (7) | 4a | 3 | 1a | ||

| Total (101) | 2 | 4 | 62a | 33 | 1a |

One isolate belonging to an ST131 unclassified clade harboured both blaCTX-M-15 and blaCMY-60.

Virotypes

ST131 has been reported in previous studies to be a highly virulent clone, exhibiting lethality in mouse sepsis models.18,32 Virotypes of all 101 ST131 isolates were determined, as previously described.18,33 Virotype C was most common, represented by 38/101 (37.6%) of ST131 isolates and predominantly associated with blaCTX-M-27 (28/38 isolates) across clades A (n=3), C1-M27 (n=22) and C1-nM27 (n=2), and 1 isolate belonged to an unclassified clade. All blaCTX-M-27-positive isolates belonged to virotype C, with the exception of one isolate for which a virotype could not be assigned. The association between virotype C and blaCTX-M-27 carriage is in agreement with a recent study conducted in France.34 Twenty-five isolates belonged to virotype A, all of which except one harboured blaCTX-M-15. The remaining 38 isolates belonged to either virotype B (n=1), D (n=1) or G (n=8) or were unknown virotypes (n=28).

Genetic context of ESBL/pAmpC genes

Despite the limitations of short-read sequencing, by examining the contigs on which GOIs were located we were able to determine the chromosomal or plasmid environments of ESBL/pAmpC genes in 85/225 isolates. Forty blaCTX-M genes, of variants blaCTX-M-14 (n=3) and blaCTX-M-15 (n=37), were found to be located on the chromosome. These were found in 11 STs with STs 131 (n=11) and 73 (n=10) being the most represented. Whilst in ST131 the blaCTX-M genetic environments were diverse, in ST73, 9/10 isolates harboured the gene in the same genomic location, suggesting a high degree of clonality within this ST. Chromosomally encoded blaCTX-M genes have previously been reported in 12.9% of human isolates in a study of ESBL E. coli performed in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK.35 The remaining GOIs were found to be located within a relatively diverse range of plasmids and across multiple STs. Interestingly, all six blaDHA-1-harbouring isolates were found to harbour a similar IncI1 plasmid, pUB_DHA-1, which was sequenced to closure during this study. Read mapping analyses showed that all six isolates exhibited 95%–100% coverage and 98%–100% identity against pUB_DHA-1.

Other important resistance genes found by WGS

Interestingly, one ST69 CMY-2-producing isolate was also found to harbour mcr-1. Susceptibility testing, performed by broth microdilution, revealed that the MIC of colistin for this isolate was 8 mg/L and so it is colistin resistant. Attempts at transformation of E. coli DH5α using plasmid DNA extracted from this isolate were successful, indicating that mcr-1 is plasmid encoded. Analysis of the genetic environment of mcr-1 found that it is encoded on an IncI2 plasmid of ∼ 62 kb and it lacks the upstream ISApl1 element that was described in the initial discovery of mcr-1 in China.36 The plasmid itself does not encode any additional resistance genes and when subjected to NCBI BLAST analysis exhibited ∼96% similarity to mcr-1-encoding plasmids found in both China (pHNGDF93; GenBank accession number MF978388) and Taiwan (p5CRE51-MCR-1; GenBank accession number CP021176) from animal and human origins, respectively. Since initial reports of its discovery in 2015,36mcr-1 has been reported worldwide in clinical E. coli isolates, although it remains relatively rare.

Another isolate, a blaCTX-M-14-positive ST38, also encoded the blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase gene blaOXA-244.37 Transformation attempts using plasmid DNA from this isolate were unsuccessful and so it was concluded that blaOXA-244 is likely to be chromosomally encoded. Disc susceptibility testing showed that this isolate was resistant to ertapenem, but susceptible to both imipenem and meropenem. The presence of the chromosomally encoded OXA-48-like carbapenemase blaOXA-244 confirms the observations of a previous study, where OXA-48-like genes were shown to have become embedded in the ST38 chromosome.38 ST38 is the most frequent ST associated with OXA-48-like enzymes in the UK.38

Conclusions

Resistance to 3GCs and fluoroquinolones in E. coli is of increasing concern due to the importance of these classes of drugs for the treatment of serious infections. Increasing resistance to 3GCs puts increased pressure and reliance on carbapenems, often referred to as the ‘antibiotics of last resort’ for serious MDR Gram-negative infections, and subsequently the surveillance of this resistance is essential. As observed in this study and in line with previous reports globally,2 the dissemination of successful clones, and/or ST lineages (clades), is a major cause of cefotaxime resistance in urinary isolates from primary care in South-West England.

blaCTX-M-positive E. coli have been observed in our study region since initial reports in 2000.39 The prevalence of blaCTX-M genes observed in the cefotaxime-resistant isolates in this study is reflective of the observed rates of CTX-M E. coli faecal carriage in healthy adults in the UK, as has been quantified in previous studies.28,40

The correlation between ciprofloxacin resistance and cefotaxime resistance highlighted here can be largely attributed to the dominance of successful clones/clades, namely ST131 and ST1193; the majority of both harbour chromosomal fluoroquinolone-resistance mutations. Through WGS of a subset of isolates we have shown that ST131 clade C2 is dominant and that the recently described ST131 subclade C1-M27 is also prevalent despite not previously being described in the UK.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first analysis of cefotaxime-resistant E. coli causing CO-UTIs performed in a relatively localized area in South-West England and could be useful for informing patient treatment, alongside resistance information generated in the hospital laboratory, to provide essential data for comparison purposes with other areas, both within and outside the UK.

Acknowledgements

Genome sequencing was provided by MicrobesNG (https://microbesng.uk/), which is supported by the BBSRC (grant number BB/L024209/1).

Funding

This work was funded by grant NE/N01961X/1 to M. B. A. and A. P. M. from the Antimicrobial Resistance Cross Council Initiative supported by the seven UK research councils.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References

PHE. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR).

EUCAST. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 8.1. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_8.1_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

- polymerase chain reaction

- plasmids

- cefotaxime

- cephalexin

- ciprofloxacin

- urinary tract infections

- clone cells

- disease transmission

- fluoroquinolones

- genes

- genome

- ichthyosis, x-linked

- primary health care

- sequence tagged sites

- urinary tract

- escherichia coli

- sodium thiosulfate

- extended-spectrum beta lactamases

- whole genome sequencing