-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Eithne Nic An Riogh, Davina Swan, Geoff McCombe, Eileen O’Connor, Gordana Avramovic, Juan Macías, Cristiana Oprea, Alistair Story, Julian Surey, Peter Vickerman, Zoe Ward, John S Lambert, Willard Tinago, Irina Ianache, Maria Iglesias, Walter Cullen, Integrating hepatitis C care for at-risk groups (HepLink): baseline data from a multicentre feasibility study in primary and community care, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 74, Issue Supplement_5, November 2019, Pages v31–v38, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz454

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To examine HCV prevalence and management among people who inject drugs (PWID) attending primary care and community-based health services at four European sites using baseline data from a multicentre feasibility study of a complex intervention (HepLink).

Primary care and community-based health services in Dublin, London, Bucharest and Seville were recruited from the professional networks of the HepLink consortium. Patients were eligible to participate if aged ≥18 years, on opioid substitution treatment or at risk of HCV (i.e. injecting drug use, homeless or incarcerated), and attended the service. Data on patient demographics and prior HCV management were collected on participants at baseline.

Twenty-nine primary care and community-based health services and 530 patients were recruited. Baseline data were collected on all participants. Participants’ mean age ranged from 35 (Bucharest) to 51 years (London), with 71%–89% male. Prior lifetime HCV antibody testing ranged from 65% (Bucharest) to 95% (Dublin) and HCV antibody positivity among those who had been tested ranged from 78% (Dublin) to 95% (Bucharest). Prior lifetime HCV RNA testing among HCV antibody-positive participants ranged from 17% (Bucharest) to 84% (London). Among HCV antibody- or RNA-positive participants, prior lifetime attendance at a hepatology/infectious disease service ranged from 6% (London) to 50% (Dublin) and prior lifetime HCV treatment initiation from 3% (London) to 33% (Seville).

Baseline assessment of the HCV cascade of care among PWID attending primary care and community-based health services at four European sites identified key aspects of the care cascade at each site that need to be improved.

Introduction

Prevalence of HCV infection among people who inject drugs (PWID) ranges from 5% to 90% in 29 European countries.1 Despite the high prevalence of HCV among PWID, estimates of undiagnosed HCV infection among PWID in Europe range from 24% to 76% and among PWID diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) just 1%–19% have commenced HCV treatment.2 Consequently, modelling studies predict substantial increases in the burden of decompensated cirrhosis among ageing HCV-infected PWID populations.3,4

Research has identified multiple barriers impeding PWID from accessing HCV testing, follow-up evaluation and treatment, including restrictions around HCV treatment eligibility; not being referred for treatment; fear of HCV investigations (e.g. liver biopsy) and of HCV treatment side-effects; competing priorities (such as drug use, employment or family commitments); inconvenience of travelling to testing locations and hospitals; anticipated stigma and discrimination; perceptions of HCV as relatively benign; and being asymptomatic.5–7

To address the growing burden of HCV-related morbidity among PWID and to achieve the WHO HCV targets for 2030,8 it is essential that countries increase HCV prevention and screening and the treatment of diagnosed individuals. As many PWID remain unaware of their infection or are not accessing HCV care, new strategies to reach such individuals are needed, including testing strategies to increase the number diagnosed, and improved care pathways to ensure those diagnosed as PWID are successfully linked to HCV evaluation and treatment.

The design and evaluation of interventions that target and simplify multiple aspects of the HCV cascade of care in the direct-acting antiviral agent (DAA) treatment era is a research priority.9 Culturally appropriate and flexible models of care that meet the specific needs and are adapted to the circumstances of PWID will be essential to optimize HCV diagnosis and linkage to HCV evaluation and treatment.10,11 Multidisciplinary, integrated models of HCV care involving partnership between HCV specialists and community healthcare providers,12 and the continuing extension of HCV care into community settings, will be an appropriate model of HCV care adapted to the needs of PWID. Various integrated care models have been described to enhance HCV assessment and interferon-based treatment among PWID, including telemedicine clinics between specialists and primary care providers,13 and on-site HCV nursing and specialist support within opioid substitution therapy (OST) clinics and community health centres.14,15

HepLink is an EU-funded project involving a consortium of five institutions: University College Dublin (Ireland); Servicio Andaluz De Salud (Spain); Spitalul Clinic de Boli Infectioase si Tropicale ‘Dr Victor Babes’ (Romania); University College London (UK); and University of Bristol (UK). The aim of HepLink is to develop integrated models of HCV care at participating sites in the consortium (Dublin, Seville, Bucharest and London), tailored to health service infrastructure and population health needs locally, with the aim of improving engagement and retention along the HCV cascade of care among PWID.16,17

The at-risk population and delivery of HCV services varies across the countries participating in the HepLink consortium (Table 1). While estimates of CHC in the general population are up to 30000 in Ireland, estimates in Spain and Romania are approximately 472000 and 489000, respectively.18–21 Estimates of HCV antibody prevalence among PWID range from 52% in England19 to up to 80% in Ireland and Spain.22–25 All four countries provide a number of options for OST, although in Ireland methadone is the almost universally prescribed formulation and buprenorphine/naloxone is currently available on a limited named patient basis only.26 Access to DAA therapies for HCV treatment has been expanding in recent years in all four countries. Presently, in Ireland, England and Spain, patients with CHC can access DAA treatments regardless of stage of liver fibrosis. In Romania, DAA access was expanded in September 2018 to all CHC patients starting from fibrosis stage Metavir F1. However, the social circumstances of many PWID in Romania mean they lack health insurance and the necessary documents (identity card and health card) to access treatment.

National context – HCV and addiction treatment services in countries participating in the HepLink consortium

| Characteristic . | Ireland . | Romania . | UK . | Spain . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic HCV infection rate estimate | 20000–3000021 | 48900018 | 21400019 | 47200020 |

| HCV antibody prevalence among PWID | 62%–81%22–24 | 74%29 | England 52%, Wales 53%, Northern Ireland 23%, Scotland 58%.19 | 60%–80%25 |

| OST modalities | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone (most common), buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone, buprenorphine, diamorphine. | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. |

| Where is OST available? | Addiction treatment centres, general practices, prisons. | Prevention, evaluation and counselling centres, by private providers and NGOs, hospitals, prisons. | Primary care treatment centres, specialist general practices, prisons. Local Clinical Commissioning Groups coordinate designation of services in each local area. | Specialized outpatient drug treatment centres, primary care centres, mental health centres, inpatient facilities, prisons. |

| DAAs available to |

|

|

|

|

| Characteristic . | Ireland . | Romania . | UK . | Spain . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic HCV infection rate estimate | 20000–3000021 | 48900018 | 21400019 | 47200020 |

| HCV antibody prevalence among PWID | 62%–81%22–24 | 74%29 | England 52%, Wales 53%, Northern Ireland 23%, Scotland 58%.19 | 60%–80%25 |

| OST modalities | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone (most common), buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone, buprenorphine, diamorphine. | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. |

| Where is OST available? | Addiction treatment centres, general practices, prisons. | Prevention, evaluation and counselling centres, by private providers and NGOs, hospitals, prisons. | Primary care treatment centres, specialist general practices, prisons. Local Clinical Commissioning Groups coordinate designation of services in each local area. | Specialized outpatient drug treatment centres, primary care centres, mental health centres, inpatient facilities, prisons. |

| DAAs available to |

|

|

|

|

National context – HCV and addiction treatment services in countries participating in the HepLink consortium

| Characteristic . | Ireland . | Romania . | UK . | Spain . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic HCV infection rate estimate | 20000–3000021 | 48900018 | 21400019 | 47200020 |

| HCV antibody prevalence among PWID | 62%–81%22–24 | 74%29 | England 52%, Wales 53%, Northern Ireland 23%, Scotland 58%.19 | 60%–80%25 |

| OST modalities | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone (most common), buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone, buprenorphine, diamorphine. | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. |

| Where is OST available? | Addiction treatment centres, general practices, prisons. | Prevention, evaluation and counselling centres, by private providers and NGOs, hospitals, prisons. | Primary care treatment centres, specialist general practices, prisons. Local Clinical Commissioning Groups coordinate designation of services in each local area. | Specialized outpatient drug treatment centres, primary care centres, mental health centres, inpatient facilities, prisons. |

| DAAs available to |

|

|

|

|

| Characteristic . | Ireland . | Romania . | UK . | Spain . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic HCV infection rate estimate | 20000–3000021 | 48900018 | 21400019 | 47200020 |

| HCV antibody prevalence among PWID | 62%–81%22–24 | 74%29 | England 52%, Wales 53%, Northern Ireland 23%, Scotland 58%.19 | 60%–80%25 |

| OST modalities | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone (most common), buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone. | Methadone, buprenorphine, diamorphine. | Methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone. |

| Where is OST available? | Addiction treatment centres, general practices, prisons. | Prevention, evaluation and counselling centres, by private providers and NGOs, hospitals, prisons. | Primary care treatment centres, specialist general practices, prisons. Local Clinical Commissioning Groups coordinate designation of services in each local area. | Specialized outpatient drug treatment centres, primary care centres, mental health centres, inpatient facilities, prisons. |

| DAAs available to |

|

|

|

|

This article examines baseline levels of HCV prevalence and HCV management at the four different country sites in the HepLink consortium (Dublin, Seville, Bucharest and London) through presenting baseline data collected prior to the introduction of the HepLink model of care at each site. These data are important for highlighting areas where improvement in the HCV care cascade is required and will provide baseline data on HCV testing, referral and treatment rates for the HepLink prospective, non-randomized pre/post-intervention feasibility study.

Patients and methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital Research Ethics Committee in Dublin (1/378/1722) and the Research Ethics Committees of collaborating institutions in Bucharest (Victor Babes Clinical Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, 3/06.01.2016), London (North West – Haydock Research Ethics Committee, 17/NW/0417) and Seville (Hospital Universitario de Valme, 0131-N-16). Regarding informed consent and consenting capacity, all potential participants (GPs, patients) were given written information on the study and the intervention being proposed, and were asked to state in writing that they consented to participation and that non-participation would not compromise their usual care. Participation in the study was on a voluntary basis. No inducements to participation were offered. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and with national and institutional standards in each country.

Setting

The study was conducted in primary care and community-based health services at four different country sites in the HepLink consortium: Dublin, Ireland; Seville, Spain; Bucharest, Romania; and London, UK. Services participating in the study at all four sites were OST-prescribing clinical services based in the community and in primary care. In Bucharest, where OST coverage is lower,27 other community-based services that provide healthcare to PWID were also recruited, including night shelters and prison services.

All participating services were recruited through the professional networks/databases of the research consortium. In Dublin, OST-prescribing general practices were recruited from the catchment area of the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital infectious diseases clinic. In Seville, large OST-prescribing primary care centres located in areas where injecting drug use is prevalent were recruited. In London, OST-prescribing primary care services with links to the pan-London Find & Treat service were recruited. The Find & Treat service is a specialist outreach service provided by University College London Hospitals NHS Trust to tackle TB among homeless people, drug or alcohol users, vulnerable migrants and people who have been in prison. In Bucharest, the OST-prescribing services and other community-based health services recruited were those with whom the Infectious Diseases Department of the Victor Babes Clinical Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases had pre-existing collaborations.

Study population

Participating patients were ≥18 years of age and on OST or at risk of HCV. In Dublin, London and Seville, patients were eligible to participate if they were aged at least 18 years, were receiving OST and attended the service during the recruitment period. In Seville, patients who currently or previously injected drugs but were not on OST were also included. In Bucharest, patients were eligible to participate if they were aged at least 18 years, had any history of high-risk behaviour (including active or past injecting drug use, homelessness or incarceration) and attended the service during the recruitment period. In London, patients currently receiving HCV treatment were excluded from the study. Patients interested in participating signed a consent form witnessed by the GP or research team member.

Patients were recruited by healthcare professionals in the respective services or by members of the research team. Methods of recruitment varied from site to site and are outlined in Table 2. Participants recruited to the HepLink study are a subset of the larger cohort of participants recruited to the HepCheck study in London, Bucharest and Seville. In Dublin, participants in the HepLink study are a separate cohort of participants from the HepCheck participants.

| Characteristic . | Dublin . | Bucharest . | London . | Seville . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating services | 14 OST-prescribing general practices in North Dublin. (7 Level 1 OST-prescribing practices, 7 Level 2 OST-prescribing practices.a) | 9 services in Bucharest: 3 centres for OST, 3 night shelters, 2 prisons, 1 other healthcare facility. | 2 OST-prescribing primary care services commissioned to test for HCV and refer for treatment in London (North and South London drug services and GP shared care patients.) | 4 OST-prescribing primary care centres in health districts north and south of Seville. |

| Recruited patients | 135 | 230 | 35 | 130 |

| eligibility criteria |

|

|

|

|

| other comments | A standardized non-probability sampling framework was used to recruit approximately 10 consecutively presenting, eligible patients from each practice.16 | Participants were recruited following invitation to screening at the relevant site. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. |

| Data collection | Manual review of patients’ medical records. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records where available. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, supplemented with case note review. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records. |

| Date baseline data collected | 2016–17 | 2016–18 | 2017–18 | 2017–18 |

| Characteristic . | Dublin . | Bucharest . | London . | Seville . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating services | 14 OST-prescribing general practices in North Dublin. (7 Level 1 OST-prescribing practices, 7 Level 2 OST-prescribing practices.a) | 9 services in Bucharest: 3 centres for OST, 3 night shelters, 2 prisons, 1 other healthcare facility. | 2 OST-prescribing primary care services commissioned to test for HCV and refer for treatment in London (North and South London drug services and GP shared care patients.) | 4 OST-prescribing primary care centres in health districts north and south of Seville. |

| Recruited patients | 135 | 230 | 35 | 130 |

| eligibility criteria |

|

|

|

|

| other comments | A standardized non-probability sampling framework was used to recruit approximately 10 consecutively presenting, eligible patients from each practice.16 | Participants were recruited following invitation to screening at the relevant site. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. |

| Data collection | Manual review of patients’ medical records. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records where available. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, supplemented with case note review. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records. |

| Date baseline data collected | 2016–17 | 2016–18 | 2017–18 | 2017–18 |

At Level 1 practices, methadone is prescribed to fewer than 15 patients. At Level 2 practices methadone is prescribed to 15 or more patients and GPs are subject to more regular audit and training. ‘Level two’ GPs can initiate patients on OST whereas ‘level one’ GPs can only treat patients already stabilized on OST.

| Characteristic . | Dublin . | Bucharest . | London . | Seville . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating services | 14 OST-prescribing general practices in North Dublin. (7 Level 1 OST-prescribing practices, 7 Level 2 OST-prescribing practices.a) | 9 services in Bucharest: 3 centres for OST, 3 night shelters, 2 prisons, 1 other healthcare facility. | 2 OST-prescribing primary care services commissioned to test for HCV and refer for treatment in London (North and South London drug services and GP shared care patients.) | 4 OST-prescribing primary care centres in health districts north and south of Seville. |

| Recruited patients | 135 | 230 | 35 | 130 |

| eligibility criteria |

|

|

|

|

| other comments | A standardized non-probability sampling framework was used to recruit approximately 10 consecutively presenting, eligible patients from each practice.16 | Participants were recruited following invitation to screening at the relevant site. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. |

| Data collection | Manual review of patients’ medical records. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records where available. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, supplemented with case note review. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records. |

| Date baseline data collected | 2016–17 | 2016–18 | 2017–18 | 2017–18 |

| Characteristic . | Dublin . | Bucharest . | London . | Seville . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating services | 14 OST-prescribing general practices in North Dublin. (7 Level 1 OST-prescribing practices, 7 Level 2 OST-prescribing practices.a) | 9 services in Bucharest: 3 centres for OST, 3 night shelters, 2 prisons, 1 other healthcare facility. | 2 OST-prescribing primary care services commissioned to test for HCV and refer for treatment in London (North and South London drug services and GP shared care patients.) | 4 OST-prescribing primary care centres in health districts north and south of Seville. |

| Recruited patients | 135 | 230 | 35 | 130 |

| eligibility criteria |

|

|

|

|

| other comments | A standardized non-probability sampling framework was used to recruit approximately 10 consecutively presenting, eligible patients from each practice.16 | Participants were recruited following invitation to screening at the relevant site. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. | All patients who met the eligibility criteria and attended the service during the recruitment period were invited to participate. |

| Data collection | Manual review of patients’ medical records. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records where available. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, supplemented with case note review. | Patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, with use of medical records. |

| Date baseline data collected | 2016–17 | 2016–18 | 2017–18 | 2017–18 |

At Level 1 practices, methadone is prescribed to fewer than 15 patients. At Level 2 practices methadone is prescribed to 15 or more patients and GPs are subject to more regular audit and training. ‘Level two’ GPs can initiate patients on OST whereas ‘level one’ GPs can only treat patients already stabilized on OST.

Data collection

Prior to the implementation of the HepLink intervention at each site, baseline data on patient demographics and prior HCV care were collected from participants’ clinical records and/or from patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires (Table 2), and included the following variables:

Prior HCV antibody test in lifetime

HCV antibody status

Prior HCV RNA test in lifetime

HCV RNA status

Referral to a specialist hepatology/infectious diseases service (for HCV) in lifetime

Attendance at a specialist hepatology/infectious diseases service in lifetime

Initiated HCV treatment in lifetime

Completed HCV treatment in lifetime

Achieved sustained virological response (SVR) in lifetime

In all sites except Seville, data were also collected on the following variable:

FibroScanned in lifetime

Past 12 month data on all of the above variables were also collected at all sites. Baseline data collection was conducted between April 2016 and December 2018.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ characteristics and study outcomes. Continuous variables were summarized using mean with standard deviation or range and categorical variables using frequencies or percentages. Analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Across the four different country sites, 29 primary care and community-based health services participated: Dublin (n=14); London (n=2); Seville (n=4); and Bucharest (n=9). A total of 530 patients were recruited (Dublin n=135; London n=35; Seville n=130; Bucharest n=230) and baseline data were collected on all participants. The mean age of participants ranged from 35 years (Bucharest) to 51 years (London) (Table 3). Male participants (n=435; 82.1%) were predominantly represented.

Participant demographics and lifetime hepatitis C screening and infection status

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=135) . | (N=35) . | (N=230) . | (N=130) . | (N=530) . | |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 71.9% (97) | 71.4% (25) | 85.7% (197) | 89.2% (116) | 82.1% (435) |

| female | 28.1% (38) | 28.6% (10) | 14.3% (33) | 10.8% (14) | 17.9% (95) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42.8 (7.6) | 51.3 (8.8) | 35.2 (7.9) | 50.0 (6.4) | – |

| HCV antibody tested | 94.8% (128) | 94.3% (33) | 65.2% (150) | 86.2% (112) | 79.8% (423) |

| HCV antibody positive/tested | 78.1% (100) | 93.9% (31) | 95.3% (143) | 87.5% (98) | 87.9% (372) |

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=135) . | (N=35) . | (N=230) . | (N=130) . | (N=530) . | |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 71.9% (97) | 71.4% (25) | 85.7% (197) | 89.2% (116) | 82.1% (435) |

| female | 28.1% (38) | 28.6% (10) | 14.3% (33) | 10.8% (14) | 17.9% (95) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42.8 (7.6) | 51.3 (8.8) | 35.2 (7.9) | 50.0 (6.4) | – |

| HCV antibody tested | 94.8% (128) | 94.3% (33) | 65.2% (150) | 86.2% (112) | 79.8% (423) |

| HCV antibody positive/tested | 78.1% (100) | 93.9% (31) | 95.3% (143) | 87.5% (98) | 87.9% (372) |

Participant demographics and lifetime hepatitis C screening and infection status

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=135) . | (N=35) . | (N=230) . | (N=130) . | (N=530) . | |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 71.9% (97) | 71.4% (25) | 85.7% (197) | 89.2% (116) | 82.1% (435) |

| female | 28.1% (38) | 28.6% (10) | 14.3% (33) | 10.8% (14) | 17.9% (95) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42.8 (7.6) | 51.3 (8.8) | 35.2 (7.9) | 50.0 (6.4) | – |

| HCV antibody tested | 94.8% (128) | 94.3% (33) | 65.2% (150) | 86.2% (112) | 79.8% (423) |

| HCV antibody positive/tested | 78.1% (100) | 93.9% (31) | 95.3% (143) | 87.5% (98) | 87.9% (372) |

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=135) . | (N=35) . | (N=230) . | (N=130) . | (N=530) . | |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 71.9% (97) | 71.4% (25) | 85.7% (197) | 89.2% (116) | 82.1% (435) |

| female | 28.1% (38) | 28.6% (10) | 14.3% (33) | 10.8% (14) | 17.9% (95) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42.8 (7.6) | 51.3 (8.8) | 35.2 (7.9) | 50.0 (6.4) | – |

| HCV antibody tested | 94.8% (128) | 94.3% (33) | 65.2% (150) | 86.2% (112) | 79.8% (423) |

| HCV antibody positive/tested | 78.1% (100) | 93.9% (31) | 95.3% (143) | 87.5% (98) | 87.9% (372) |

Screening for hepatitis C

When considering HCV antibody testing across the four different country sites at baseline, diversity was observed in lifetime HCV testing rates, with rates ranging from 65.2% in Bucharest, 86.2% in Seville, 94.3% in London and 94.8% in Dublin (Table 3). A positive HCV antibody status was observed in 78.1% (Dublin) to 95.3% (Bucharest) of those that had been tested. When considering screening conducted in the 12 months previous to the study, 68/530 (12.8%) participants across the four sites had been tested and of these 57/68 (83.8%) were HCV antibody positive.

Subsequent care of HCV antibody-positive patients

Table 4 presents the cascade of care among HCV antibody-positive participants at the four sites. Across the sites, lifetime RNA testing among HCV antibody-positive participants ranged from 16.8% (Bucharest) to 83.9% (London), with rates of RNA positivity among those who had been RNA tested ranging from 33.3% (Bucharest) to 95.6% (Seville). When considering RNA testing in the 12 months prior to the study across the four sites, testing was performed in far fewer of the HCV antibody-positive participants, with rates of 0.7% (Bucharest) to 12.9% (London) observed; 56.3% (9/16) of those who had been RNA tested in the previous 12 months across the four sites were RNA positive.

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=100) . | (N=31) . | (N=143) . | (N=98) . | (N=372) . | |

| HCV RNA tested | 57.0% (57) | 83.9% (26) | 16.8% (24) | 69.4% (68) | 47.0% (175) |

| HCV RNA positive/RNA tested | 61.4% (35) | 92.3% (24) | 33.3% (8) | 95.6% (65) | 75.4% (132) |

| N=101a | N=31 | N=143 | N=98 | N=373 | |

| Referred to hepatology/infectious disease service | 69.3% (70) | 54.8% (17) | 45.5% (65) | 45.9% (45) | 52.8% (197) |

| Attended hepatology/infectious disease service | 50.5% (51) | 6.5% (2) | 41.3% (59) | 45.9% (45) | 42.1% (157) |

| FibroScan | 16.8% (17) | 0% (0) | 7.0% (10) | NA | 9.8% (27) |

| HCV treatment initiated | 19.8% (20) | 3.2% (1) | 10.5% (15) | 32.7% (32) | 18.2% (68) |

| HCV treatment completed | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 7.7% (11) | 25.5% (25) | 13.7% (51) |

| SVR attained | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 2.8% (4) | 21.4% (21) | 10.7% (40) |

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=100) . | (N=31) . | (N=143) . | (N=98) . | (N=372) . | |

| HCV RNA tested | 57.0% (57) | 83.9% (26) | 16.8% (24) | 69.4% (68) | 47.0% (175) |

| HCV RNA positive/RNA tested | 61.4% (35) | 92.3% (24) | 33.3% (8) | 95.6% (65) | 75.4% (132) |

| N=101a | N=31 | N=143 | N=98 | N=373 | |

| Referred to hepatology/infectious disease service | 69.3% (70) | 54.8% (17) | 45.5% (65) | 45.9% (45) | 52.8% (197) |

| Attended hepatology/infectious disease service | 50.5% (51) | 6.5% (2) | 41.3% (59) | 45.9% (45) | 42.1% (157) |

| FibroScan | 16.8% (17) | 0% (0) | 7.0% (10) | NA | 9.8% (27) |

| HCV treatment initiated | 19.8% (20) | 3.2% (1) | 10.5% (15) | 32.7% (32) | 18.2% (68) |

| HCV treatment completed | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 7.7% (11) | 25.5% (25) | 13.7% (51) |

| SVR attained | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 2.8% (4) | 21.4% (21) | 10.7% (40) |

NA, not applicable (Seville did not collect data on these variables).

This figure includes one patient who was HCV antibody negative but RNA positive.

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=100) . | (N=31) . | (N=143) . | (N=98) . | (N=372) . | |

| HCV RNA tested | 57.0% (57) | 83.9% (26) | 16.8% (24) | 69.4% (68) | 47.0% (175) |

| HCV RNA positive/RNA tested | 61.4% (35) | 92.3% (24) | 33.3% (8) | 95.6% (65) | 75.4% (132) |

| N=101a | N=31 | N=143 | N=98 | N=373 | |

| Referred to hepatology/infectious disease service | 69.3% (70) | 54.8% (17) | 45.5% (65) | 45.9% (45) | 52.8% (197) |

| Attended hepatology/infectious disease service | 50.5% (51) | 6.5% (2) | 41.3% (59) | 45.9% (45) | 42.1% (157) |

| FibroScan | 16.8% (17) | 0% (0) | 7.0% (10) | NA | 9.8% (27) |

| HCV treatment initiated | 19.8% (20) | 3.2% (1) | 10.5% (15) | 32.7% (32) | 18.2% (68) |

| HCV treatment completed | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 7.7% (11) | 25.5% (25) | 13.7% (51) |

| SVR attained | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 2.8% (4) | 21.4% (21) | 10.7% (40) |

| Variable . | Dublin . | London . | Bucharest . | Seville . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=100) . | (N=31) . | (N=143) . | (N=98) . | (N=372) . | |

| HCV RNA tested | 57.0% (57) | 83.9% (26) | 16.8% (24) | 69.4% (68) | 47.0% (175) |

| HCV RNA positive/RNA tested | 61.4% (35) | 92.3% (24) | 33.3% (8) | 95.6% (65) | 75.4% (132) |

| N=101a | N=31 | N=143 | N=98 | N=373 | |

| Referred to hepatology/infectious disease service | 69.3% (70) | 54.8% (17) | 45.5% (65) | 45.9% (45) | 52.8% (197) |

| Attended hepatology/infectious disease service | 50.5% (51) | 6.5% (2) | 41.3% (59) | 45.9% (45) | 42.1% (157) |

| FibroScan | 16.8% (17) | 0% (0) | 7.0% (10) | NA | 9.8% (27) |

| HCV treatment initiated | 19.8% (20) | 3.2% (1) | 10.5% (15) | 32.7% (32) | 18.2% (68) |

| HCV treatment completed | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 7.7% (11) | 25.5% (25) | 13.7% (51) |

| SVR attained | 13.9% (14) | 3.2% (1) | 2.8% (4) | 21.4% (21) | 10.7% (40) |

NA, not applicable (Seville did not collect data on these variables).

This figure includes one patient who was HCV antibody negative but RNA positive.

Of the 373 participants known to be HCV antibody or RNA positive across the four sites, 197 (52.8%) had been referred to a hepatology or infectious disease specialist during their lifetime, with the highest referral rate in Dublin (69.3%). In the 12 months before the study, 44/373 (11.8%) antibody- or RNA-positive participants had been referred. Lifetime attendance at a hepatology/infectious diseases service among HCV antibody- or RNA-positive participants showed considerable differences between the sites, with 50.5% of HCV antibody- or RNA-positive participants ever attending in Dublin, 45.9% attending in Seville, 41.3% attending in Bucharest and 6.5% attending in London. Attendance at hepatology/infectious diseases services in the 12 months before the study ranged from 0% (London) to 25.7% (Dublin) of HCV antibody- or RNA-positive participants, with 51/373 (13.7%) antibody- or RNA-positive participants across the four sites attending in the past year. A FibroScan had ever been carried out in 27 (9.8%) of the 275 HCV antibody- or RNA-positive participants in Dublin, London and Bucharest.

Across the four sites, HCV treatment had ever been initiated in 3.2% (London) to 32.7% (Seville) of HCV antibody- or RNA-positive participants. Among the 373 antibody- or RNA-positive participants across the four sites, a total of 68 (18.2%) had ever initiated HCV treatment, 51 (13.7%) had ever completed treatment and 40 (10.7%) had ever attained SVR (Table 4).

Discussion

Key findings

We examined HCV prevalence and HCV management among PWID attending primary care and community-based health services at four European sites (Dublin, London, Bucharest and Seville) using baseline data from a multicentre feasibility study of a complex intervention. Services participating in the study were OST-prescribing clinical services based in the community and in primary care, and in Bucharest, where OST coverage is lower,27 other community-based services which provide healthcare to PWID were also recruited, including night shelters and prisons. The cohorts recruited at the four different sites differ in terms of mean age and the proportion of male participants. Although cohorts are not comparable across the four sites, they provide important data on the HCV cascade of care at each site and the aspects of the care cascade that need to be improved.

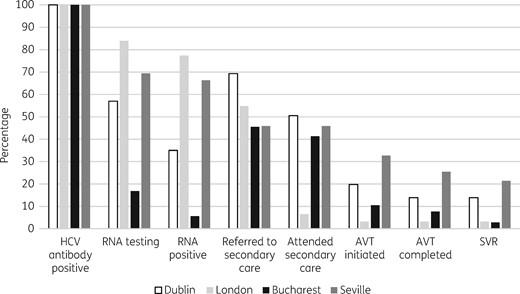

Baseline rates of HCV screening were high (>90%) in Dublin and London and less than optimal in Seville (86%). The lowest screening rate (65%) was observed in Bucharest, where the study recruited from services caring for more marginalized PWID (e.g. street homeless and prisoners). The rate of RNA testing among HCV antibody-positive patients was high in London (84%). In Dublin and Seville, a substantial minority of HCV antibody-positive patients had never been RNA tested (43% Dublin and 31% Seville). Bucharest had the lowest RNA testing rate (17%) among HCV antibody-positive patients, as many PWID in Romania lack health insurance and the necessary documents (identity card and health card) to receive specialist HCV evaluation and treatment. At all four sites, substantial proportions of HCV antibody-positive patients (31%–55%) had never been referred to hepatology or infectious diseases services. Among those ever referred, lifetime attendance was high in Bucharest (91%) and Seville (100%). However, lifetime attendance among those ever referred was suboptimal in Dublin (73%) and very low (12%) in London. In addition, attendance rates for the 12 months before the study among those ever referred was low at all four sites (0%–25.7%). Treatment initiation rates among HCV antibody-positive patients were generally low across the four sites (3%–33%). This may be explained in part by the suboptimal referral to secondary care at all sites, and the poor attendance in London amongst those referred. However, among HCV antibody-positive patients who had ever attended secondary care, treatment initiation rates were low in both Bucharest (25.4%) and Dublin (39.2%). The treatment initiation rate among HCV antibody-positive patients who had ever attended secondary care in Seville was high (71.1%). Restrictions regarding DAA treatment eligibility in Romania and Ireland at the time of data collection may be regarded as a contributory factor to the low treatment rates. These data highlight areas in which the HCV cascade of care needs to be improved (Figure 1).

Cascade of care for HCV antibody-positive PWID attending primary care and community-based services in four European cities. AVT, antiviral therapy.

Comparison with existing literature

This study observed high rates of HCV antibody positivity among those who had been tested across the four sites (78%–95%). The proportion testing HCV antibody-positive in Dublin (78%) is similar to previously published estimates.22–24 The percentage of patients testing HCV antibody-positive in London (94%) is considerably higher than reported rates for PWID in England (52%)19 and London specifically (55%).28 In Bucharest, the proportion testing antibody positive (95%) is higher than that reported for Romania (74%) in the review of anti-HCV prevalence among PWID by Nelson et al.29 In Seville, 88% of those who had been tested were HCV antibody positive, which is slightly higher than published estimates of 60%–80% among PWID in Spain.25 The higher infection rates observed in our study are likely due to participating services being OST-prescribing services and the relatively older age of our cohorts; thus, participants have likely had a longer period of time exposed to risk of HCV infection.

The percentages testing HCV RNA positive varied across the sites from 33% of those RNA tested in Bucharest, to 61% in Dublin, 92% in London and 96% in Seville. The low RNA-positive rate in Bucharest is partly explained by the limitations of patient self-report, where many patients did not know their RNA test results. A recent systematic review of HCV RNA prevalence among people with recent injecting drug use estimated rates of RNA positivity of 23% in England, 53% in Spain, 56% in Ireland and 63% in Romania.30 The higher chronic infection rates in the London and Seville cohorts in our study may be due to a potential bias in cohort selection. It is possible that services focused more on recruiting patients who were known to be chronically infected but disengaged from care, given that the study involved a linkage to care intervention.

Only 18% of HCV antibody-positive patients across the four sites had ever commenced HCV treatment, which is similar to previous reports.2 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examining regional differences in HCV treatment rates among CHC patients (not restricted to PWID) found a treatment rate of 34% for the European region.31

Similar to our findings, a study of HCV care milestones achieved by HCV antibody-positive patients in three community-based primary care clinics in the Bronx, New York, identified multiple deficiencies in the HCV cascade of care.32 More than 20% of HCV antibody-positive patients identified through risk-based and birth cohort screening in their study did not receive confirmatory viral load testing to determine chronic infection. Just 43% of the antibody-positive patients were referred for specialist HCV care, and less than 4% initiated HCV treatment.32 Likewise, a study examining the HCV cascade of care among PWID with CHC in Vancouver, Canada, found that the step in the cascade of care from ever attending an HCV specialist to commencing HCV treatment involves substantial attrition among PWID. In their study, while a high proportion of PWID with CHC had ever seen an HCV specialist (87%), just 10% had ever initiated HCV treatment. Patient as well as system factors were responsible for the low treatment rate, as 70% of PWID who had been offered treatment had declined to take it, with concerns about side effects and being asymptomatic being the most common explanations given for refusing treatment.7

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted in countries with autonomous service infrastructure and differing populations. Participating services were recruited through the professional networks/databases of the consortium members and therefore are not a random sample of primary care and community-based health services caring for PWID at each site. In Dublin, London and Seville, cohorts were recruited from OST-prescribing services and therefore the findings may not be generalizable to PWID who are not engaged in addiction treatment. In addition, we did not collect data on the number and characteristics of patients who refused to participate in the study. The methodology of collecting data varied between sites, with Seville, London and Bucharest using patient self-report via researcher-administered questionnaires, augmented by medical record or case note review where available, and Dublin using medical record review only. It is not clear what impact the difference in data sources had on study outcome measures.

However, this study provides a baseline assessment of the HCV cascade of care among PWID attending OST-prescribing primary care services and other community-based health services at four European sites, which is crucial for evaluating where improvements to the care cascade are needed. The study provides a benchmark for testing, referral and treatment levels so that increases in these can be targeted through the introduction of new interventions.

Implications for practice, policy and future research

Baseline data presented here highlight the need for better linkage to HCV evaluation and treatment in all sites and increased screening in Bucharest and Seville. The HepLink model of care has since been introduced at the four sites and aims to integrate primary and secondary care services to facilitate linkage to HCV evaluation and treatment among PWID. The key components of the HepLink model are: (i) outreach of an HCV-trained nurse into primary care and community-based services to provide clinical support and facilitate referrals to hepatology and infectious diseases services; (ii) patient and health professional education on HCV and developments in its diagnosis and treatment; and (iii) community-based evaluation of HCV disease (including FibroScan to stage liver fibrosis). Through the evaluation of post-intervention data, it will be possible to discern the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions at the four different country sites and identify where further refinement is needed. Cross-sectional analyses of the data will provide insights into the uptake of the interventions, while longitudinal data will provide information on the potential impact of the interventions over time, including retention of participants through the HCV cascade of care.33

The HepLink model of care has the potential to improve access to HCV care and provide quality healthcare to marginalized populations who might otherwise remain undiagnosed and untreated. Evaluation of post-intervention data will enhance the scientific understanding of interventions that contribute to health and social gain locally and internationally. If successful, the HepLink model could be easily implemented in other sites and could inform national and European policy and service development.

Conclusions

Baseline data on HCV prevalence and HCV management among PWID attending primary care and community-based health services at four European sites highlight the need for better linkage to HCV evaluation and treatment in all sites and increased testing in Bucharest and Seville. It is paramount that effective interventional strategies are developed and implemented in primary and community care settings in order to facilitate HCV treatment among PWID and to achieve the WHO goal of eliminating the virus as a major public health threat by 2030. Characterization of the HCV cascade of care among PWID is crucial to developing appropriate strategies and monitoring their impact.34

Acknowledgements

We thank the services and service users who participated in this study in Dublin, London, Bucharest and Seville.

Funding

This work is supported by the European Commission through its EU Third Health Programme (Grant Agreement Number 709844) and Ireland’s Health Services Executive.

Transparency declarations

J.S.L. has received non-restricted grants from Gilead, Abbvie and MSD for hepatitis C related educational and research activities. J.S.L. has received honorariums for advisory board meetings on HIV and hepatitis C, organized by Gilead, Abbvie, Glaxo Smith Kline, Viiv, and Merck. W.C. has been a principal investigator on research projects funded by the Health Research Board of Ireland, the European Commission Third Health Program, Ireland’s Health Services Executive and Gilead, been co-investigator on projects funded by Abbvie and received honoraria from Gilead in respect of participation in advisory board on hepatitis C. J.M. has served as an investigator in clinical trials supported by Bristol Myers-Squibb, Gilead and MSD. J.M. has also served as a paid lecturer for Gilead, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and MSD, and has received consultancy fees from Bristol Myers-Squibb, Gilead and MSD. J.M. has received a grant from the Servicio Andaluz de Salud de la Junta de Andalucia. C.O. has served as a paid speaker for Janssen, BMS and Abbvie; has served as an advisory board member for Teva, ViiV, and Gilead, and as a principal investigator on clinical trials supported by ViiV, and as a co-investigator on clinical trials supported by Abbvie and Tibot. P.V. has received an honorarium from Abbvie and unrestricted research grants from Gilead, not related to this work. D.S. has received financial support from Gilead for the costs of attendance at IOTOD 2017 conference. All other authors: none to declare.

This article is part of a Supplement sponsored by the HepCare Europe Project.

References

World Health Organization.

Public Health England. Hepatitis C in the UK 2019 - Working to eliminate hepatitis C as a major public health threat. Public Health England, 2019.

Field Epidemiology Service South East and London.