-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tanya du Plessis, Genevieve Walls, Anthony Jordan, David J Holland, Implementation of a pharmacist-led penicillin allergy de-labelling service in a public hospital, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 74, Issue 5, May 2019, Pages 1438–1446, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky575

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Inaccurate allergy labelling results in inappropriate antimicrobial management of the patient, which may affect clinical outcome, increase the risk of adverse events and increase costs. Inappropriate use of alternative antibiotics has implications for antimicrobial stewardship programmes and microbial resistance.

All adult inpatients labelled as penicillin allergic were identified and screened for eligibility by the study pharmacist. An accurate allergy and medication history was taken. Patients were ‘de-labelled’, underwent oral challenge or were referred to an immunology clinic, if study criteria were met. All patients included in the study were followed-up 1 year after intervention.

Two hundred and fifty eligible patients with a label of ‘penicillin allergy’ were identified. The prevalence of reported penicillin allergy at Middlemore Hospital was 11%. We found that 80% of study patients could be ‘de-labelled’. Of those, 80% were ‘de-labelled’ after an interview with the pharmacist alone, 16% had an uneventful oral challenge and 4% were deemed to be inappropriately labelled after referral to an immunology clinic. Appropriately labelled patients accounted for 20% of the study population. Changes to inpatient antibiotic therapy were recommended in 61% of ‘de-labelled’ patients, of which no patients had adverse events after commencing on penicillin antibiotics. At the 1 year follow-up, 98% of patients who were ‘de-labelled’ had no adverse events to repeated administration of penicillin antibiotics.

This study showed that a pharmacist-led allergy management service is a safe option to promote antimicrobial stewardship and appropriate allergy labelling.

Introduction

Antimicrobial stewardship encompasses the concept of reducing inappropriate antibiotic use with the aim of preserving therapeutic options and slowing the spread of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance is identified by the WHO as a current global health emergency.1 Inappropriate use of antibiotics, particularly broad-spectrum antibiotics, contributes to increasing resistance in bacteria. Patients who are allergic to β-lactam antibiotics (e.g. penicillin) are commonly prescribed second-line or unnecessarily broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat infection. The IDSA has recently published guidelines in which it recognized the impact of allergy assessments as part of an antimicrobial stewardship programme.2

The prevalence of self-reported penicillin allergy is up to 15% in hospital inpatients3–8 and yet between 80% and 90% of patients labelled as penicillin allergic are found to be negative on skin testing,3,9,10 suggesting the majority are inaccurately labelled as penicillin allergic. Patients with penicillin allergy have longer lengths of hospital stay,11 are more likely to be treated with potentially less effective12–14 or more costly11,15 second-line antibiotics and are at higher risk of acquisition of multiresistant organisms,11,16 readmission to hospital and treatment-related adverse events.17 Studies have suggested that >50% of reported ‘allergies’ are non-immunological in nature15 (i.e. adverse reactions such as nausea or intolerances), rather than true allergy. Pharmacists are uniquely placed to play an essential part in assessing reported allergy. Perceived barriers to implementing formal allergy assessments in many healthcare settings include lack of access to allergists/immunologists to perform penicillin skin testing followed by oral challenge,8,18–21 as well as the cost associated with these tests.22 Between 30% and 63% of patients can be ‘de-labelled’ after patient interview and interrogation of the electronic medical record and medication history,23,24 without the need for formal testing. However, supporting evidence is largely based on smaller studies that are extrapolated to population level.

We hypothesized that a significant proportion of ‘penicillin allergic’ patients at Middlemore Hospital were inaccurately labelled and could be safely de-labelled by a combination of history and oral challenge, undertaken by a specialist pharmacist in the hospital setting.

Methods

Setting and participants

This prospective interventional study was performed between May and July 2015 at Middlemore Hospital, an 800 bed tertiary-level referral hospital located in Auckland, New Zealand. Middlemore Hospital has specialist Infectious Diseases and Antimicrobial Stewardship services but does not have on-site allergy/immunology consultants. Patients requiring formal allergy/immunology assessment are referred to the Immunology Clinic at Auckland City Hospital.

The allergy status of all adult patients (aged >16 years) admitted during the study period was reviewed electronically and manually, using paper-based medication prescription charts or the electronic Inpatient Management System, a comprehensive record of all ‘warnings’ (including reported allergy) attached to each patient’s unique National Health Index number. Access to the Inpatient Management System is restricted to only healthcare providers and information is validated and audited regularly.

Adults with reported penicillin allergy, admitted for ≥24 h and available for interview within working hours (08:00–16:00 h, Monday–Friday) were included in the study. Consent to approach the patients was sought from the treating clinical team. All patients provided informed consent prior to inclusion. Patients were excluded from the study if they were admitted to the mental health unit or theatre admission day unit, or if they were unable to give consent. Patients enrolled in the study had additional exclusion criteria applied before a decision on oral challenges (see Table 1).

| Pregnant patients |

| <16 years and >70 years |

| Patients with asthma and/or COPD that is (i) poorly controlled and/or (ii) required hospitalization within 1 year of consent and/or (iii) ever admitted to an ICU and/or (iv) FEV1 <40% |

| Patients who have had an allergic reaction within 4 weeks of proposed enrolment |

| Patients who have ever had SJS, TEN or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in relation to a β-lactam antibiotic |

| Patients with significant cardiovascular disease (active angina; arrhythmias; NSTEMI or CABG within 6 months) |

| Patients on β-blockers and ACE inhibitors |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg |

| Haemodynamically unstable patients |

| Pregnant patients |

| <16 years and >70 years |

| Patients with asthma and/or COPD that is (i) poorly controlled and/or (ii) required hospitalization within 1 year of consent and/or (iii) ever admitted to an ICU and/or (iv) FEV1 <40% |

| Patients who have had an allergic reaction within 4 weeks of proposed enrolment |

| Patients who have ever had SJS, TEN or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in relation to a β-lactam antibiotic |

| Patients with significant cardiovascular disease (active angina; arrhythmias; NSTEMI or CABG within 6 months) |

| Patients on β-blockers and ACE inhibitors |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg |

| Haemodynamically unstable patients |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in first second; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

| Pregnant patients |

| <16 years and >70 years |

| Patients with asthma and/or COPD that is (i) poorly controlled and/or (ii) required hospitalization within 1 year of consent and/or (iii) ever admitted to an ICU and/or (iv) FEV1 <40% |

| Patients who have had an allergic reaction within 4 weeks of proposed enrolment |

| Patients who have ever had SJS, TEN or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in relation to a β-lactam antibiotic |

| Patients with significant cardiovascular disease (active angina; arrhythmias; NSTEMI or CABG within 6 months) |

| Patients on β-blockers and ACE inhibitors |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg |

| Haemodynamically unstable patients |

| Pregnant patients |

| <16 years and >70 years |

| Patients with asthma and/or COPD that is (i) poorly controlled and/or (ii) required hospitalization within 1 year of consent and/or (iii) ever admitted to an ICU and/or (iv) FEV1 <40% |

| Patients who have had an allergic reaction within 4 weeks of proposed enrolment |

| Patients who have ever had SJS, TEN or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in relation to a β-lactam antibiotic |

| Patients with significant cardiovascular disease (active angina; arrhythmias; NSTEMI or CABG within 6 months) |

| Patients on β-blockers and ACE inhibitors |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg |

| Haemodynamically unstable patients |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in first second; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

The investigating pharmacist undertook training in the preparation and administration of oral challenges at a local immunology clinic.

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Health and Disability Ethics Committee (15/CEN/87).

Intervention

After informed consent, the pharmacist interviewed eligible patients. The interview included a full medication history and allergy assessment using a standardized questionnaire (see Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online) to assess the validity of the documented allergy and collate the antibiotic history. The patient’s recall was corroborated with medical records where possible.

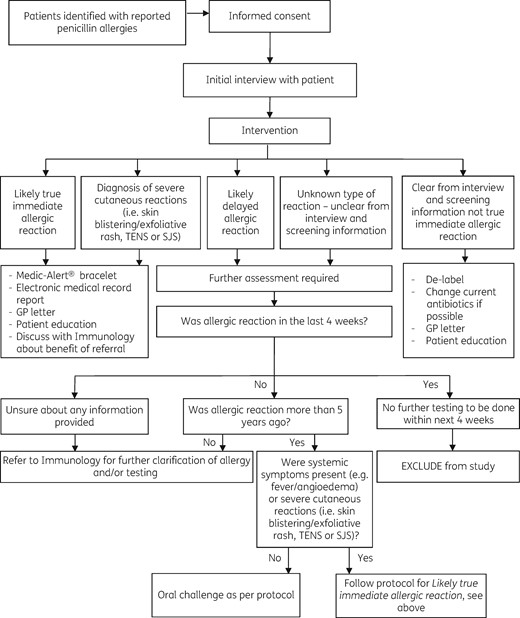

Following the interview, patients were directly de-labelled, offered an oral challenge to clarify allergy status or referred to the immunology clinic for further assessment where allergy status was not clear (see Figure 1).

Study protocol. SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Patients were directly de-labelled and had their allergy label removed from their medical record if the interview clearly revealed their ‘allergy’ was not consistent with a true immediate hypersensitivity reaction.

Patients were offered an oral challenge if the interview suggested that the penicillin ‘allergy’ was likely to be a delayed-type reaction (e.g. delayed- onset rash). Patients were provided with written information on the oral challenge and asked to give separate informed consent. Oral challenges were undertaken while the patients were still inpatients and were supervised by the primary treating team. The investigating pharmacist prepared the test doses and oversaw administration (see Table 2).

| Drug . | Drug class . | Doses (in mg) . | Route . | Daily dose for adult . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | penicillin | placebo, placebo, 5 mg, 50 mg, 500 mg (all suspension, in yoghurt) | oral | 1000 mg three times daily (given as 500 mg capsules) |

| Drug . | Drug class . | Doses (in mg) . | Route . | Daily dose for adult . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | penicillin | placebo, placebo, 5 mg, 50 mg, 500 mg (all suspension, in yoghurt) | oral | 1000 mg three times daily (given as 500 mg capsules) |

Doses given 30 min apart until the daily adult dose is attained. If no reaction, further full doses are administered to ensure no reaction. If no continued therapy is required, then only 24 h is administered.

| Drug . | Drug class . | Doses (in mg) . | Route . | Daily dose for adult . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | penicillin | placebo, placebo, 5 mg, 50 mg, 500 mg (all suspension, in yoghurt) | oral | 1000 mg three times daily (given as 500 mg capsules) |

| Drug . | Drug class . | Doses (in mg) . | Route . | Daily dose for adult . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | penicillin | placebo, placebo, 5 mg, 50 mg, 500 mg (all suspension, in yoghurt) | oral | 1000 mg three times daily (given as 500 mg capsules) |

Doses given 30 min apart until the daily adult dose is attained. If no reaction, further full doses are administered to ensure no reaction. If no continued therapy is required, then only 24 h is administered.

If the oral challenge was negative, the patient was de-labelled. The oral challenge was positive if it reproduced the original reported reaction. In this situation, the patient’s allergy label was confirmed and communicated as below.

Patients who gave a vague history, had an inconclusive interview, who did not meet the inclusion criteria for oral challenge, who had had a hypersensitivity reaction within 5 years prior to the study, who had had systemic symptoms or symptoms suggestive of Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis or whom the pharmacist felt were unsafe to de-label via the other methods were referred to the immunology clinic for full assessment. The investigating pharmacist reviewed the outcomes of these assessments and completed planned communication.

Communication

All patients received education about their allergy status, regardless of whether they were de-labelled or not. Formal letters were given to patients and sent to primary care practitioners, explaining the outcome of the interview and any intervention. All electronic medical records were updated after interventions, to reflect allergy label status as confirmed or de-labelled. In the event of confirmed allergy label, type and time of reaction including medical management given was recorded in the patient’s medical record, if this was available. Results from the formal allergy/immunology assessment were followed-up and electronic medical records updated. Patients also received information about applying for a Medic-Alert® bracelet.

Follow-up

All included patients were followed-up at 1 month and 1 year after the intervention, with a telephone interview performed by the investigating pharmacist to ascertain patients’ perspective and interpretation and safety after interventions.

Antibiotic usage and cost

Antibiotic usage for patients, 1 year prior to and 1 year after the intervention, was obtained by searching outpatient dispensing records, and inpatient and outpatient drug acquisition costs at the time of follow-up were used to estimate the cost of antibiotics before and after interventions. Estimated costs were used after intervention, using the appropriate dosing regimen for the patient and the treatment duration prescribed. Appropriateness of antibiotic selection was determined by comparing indication for antibiotic with approved local guidelines or by discussing with an infectious diseases physician.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using StatPlus® software version 5.0 (AnalystSoft). Frequencies were calculated for categorical variables and medians and IQRs were calculated for continuous variables. Bivariable analysis identified relationships between patient characteristics and appropriate allergy labelling using Fisher’s exact test or Hartley’s f-test for equality of variance. Coefficients were reported with 95% CIs and P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was deemed as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

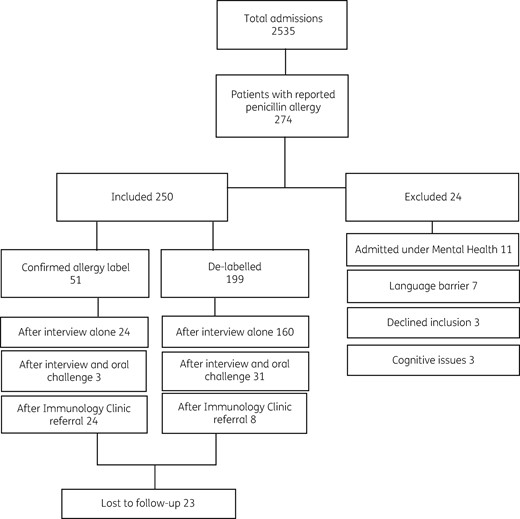

The study was performed for 32 days spread over 2 months. The medical records of 2535 patients were screened and all patients with reported penicillin allergies (274) were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 24 patients were excluded (see Figure 2).

Proportion of study population included and excluded. Intervention outcomes described for included population.

None of the included patients had previously had any allergy testing. Table 3 outlines the patient demographics and details of reported allergic reactions. The median time since the initial reported reaction was 22 years (IQR = 9–42 years). Many patients (143 of 250, 57%) had poor recall about their initial hypersensitivity reaction. On admission, 192 of 250 patients (77%) received an antibiotic. The indications for antibiotics in this group were bloodstream (39 of 192, 20%), skin and soft tissue (35 of 192, 18%), respiratory (30 of 192, 16%) and urinary tract (28 of 192, 15%) infections.

Demographic data and details of reported allergy for enrolled patients; N = 250

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 65 (51–81) |

| Female, n (%) | 156 (62) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 116 (46) |

| Maaori | 37 (15) |

| Pacific Island | 43 (17) |

| Asian | 48 (19) |

| other | 6 (2) |

| Family history of allergy, n (%) | 93 (37) |

| Time since reported reaction (years), n (%) | |

| 1–5 | 39 (16) |

| 6–20 | 72 (29) |

| >20 | 139 (56) |

| Type of reported reactions, n (%) | |

| rash | 69 (28) |

| nausea/vomiting | 43 (17) |

| gastrointestinal upset | 39 (16) |

| throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 26 (10) |

| dizziness/headaches | 28 (11) |

| deranged liver function tests | 8 (3) |

| seizures | 1 (0.4) |

| general swelling (excluding throat) | 7 (3) |

| unsure | 29 (12) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 65 (51–81) |

| Female, n (%) | 156 (62) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 116 (46) |

| Maaori | 37 (15) |

| Pacific Island | 43 (17) |

| Asian | 48 (19) |

| other | 6 (2) |

| Family history of allergy, n (%) | 93 (37) |

| Time since reported reaction (years), n (%) | |

| 1–5 | 39 (16) |

| 6–20 | 72 (29) |

| >20 | 139 (56) |

| Type of reported reactions, n (%) | |

| rash | 69 (28) |

| nausea/vomiting | 43 (17) |

| gastrointestinal upset | 39 (16) |

| throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 26 (10) |

| dizziness/headaches | 28 (11) |

| deranged liver function tests | 8 (3) |

| seizures | 1 (0.4) |

| general swelling (excluding throat) | 7 (3) |

| unsure | 29 (12) |

Demographic data and details of reported allergy for enrolled patients; N = 250

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 65 (51–81) |

| Female, n (%) | 156 (62) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 116 (46) |

| Maaori | 37 (15) |

| Pacific Island | 43 (17) |

| Asian | 48 (19) |

| other | 6 (2) |

| Family history of allergy, n (%) | 93 (37) |

| Time since reported reaction (years), n (%) | |

| 1–5 | 39 (16) |

| 6–20 | 72 (29) |

| >20 | 139 (56) |

| Type of reported reactions, n (%) | |

| rash | 69 (28) |

| nausea/vomiting | 43 (17) |

| gastrointestinal upset | 39 (16) |

| throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 26 (10) |

| dizziness/headaches | 28 (11) |

| deranged liver function tests | 8 (3) |

| seizures | 1 (0.4) |

| general swelling (excluding throat) | 7 (3) |

| unsure | 29 (12) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 65 (51–81) |

| Female, n (%) | 156 (62) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 116 (46) |

| Maaori | 37 (15) |

| Pacific Island | 43 (17) |

| Asian | 48 (19) |

| other | 6 (2) |

| Family history of allergy, n (%) | 93 (37) |

| Time since reported reaction (years), n (%) | |

| 1–5 | 39 (16) |

| 6–20 | 72 (29) |

| >20 | 139 (56) |

| Type of reported reactions, n (%) | |

| rash | 69 (28) |

| nausea/vomiting | 43 (17) |

| gastrointestinal upset | 39 (16) |

| throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 26 (10) |

| dizziness/headaches | 28 (11) |

| deranged liver function tests | 8 (3) |

| seizures | 1 (0.4) |

| general swelling (excluding throat) | 7 (3) |

| unsure | 29 (12) |

Intervention outcomes

A total of 199 of 250 patients (80%) were found to have an incorrect penicillin allergy label and had their allergy labels removed (see Figure 2). Of these 199 patients, 160 (80%) were de-labelled after the assessment interview without any further testing. Of these patients, 127 of 160 (79%) had received and tolerated a course of a penicillin antibiotic prior to inclusion without adverse effect (despite apparently being ‘allergic’). In addition, about two-thirds of patients (110 of 160, 69%) described an adverse event such as nausea, vomiting or headaches (see Table 4) rather than a recognized hypersensitivity reaction. Many patients fell into both groups (77 of 160, 48%).

Intervention outcomes for the study population with reference to reported reactions

| Reported reaction . | De-labelled, n = 199 . | Confirmed, n = 51 . | Total, n = 250 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rash | 64 | 5 | 69 |

| after oral challenge | 29 | 1 | |

| immunology referral | 2 | 4 | |

| interview | 33 | 0 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 43 | 0 | 43 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 43 | 0 | |

| Throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 2 | 24 | 26 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 2a | 24 | |

| Dizziness/headaches | 28 | 0 | 28 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 28 | 0 | |

| Hepatic derangements | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 8 | 0 | |

| Seizures | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 0 | |

| interview | 0 | 0 | |

| General swelling/oedema (excluding throat) | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 4 | |

| interview | 2 | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 39 | 0 | 39 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 39 | 0 | |

| Unsure | 11 | 18 | 29 |

| after oral challenge | 2 | 2 | |

| immunology referral | 4 | 16 | |

| interview | 5 | 0 |

| Reported reaction . | De-labelled, n = 199 . | Confirmed, n = 51 . | Total, n = 250 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rash | 64 | 5 | 69 |

| after oral challenge | 29 | 1 | |

| immunology referral | 2 | 4 | |

| interview | 33 | 0 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 43 | 0 | 43 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 43 | 0 | |

| Throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 2 | 24 | 26 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 2a | 24 | |

| Dizziness/headaches | 28 | 0 | 28 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 28 | 0 | |

| Hepatic derangements | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 8 | 0 | |

| Seizures | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 0 | |

| interview | 0 | 0 | |

| General swelling/oedema (excluding throat) | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 4 | |

| interview | 2 | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 39 | 0 | 39 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 39 | 0 | |

| Unsure | 11 | 18 | 29 |

| after oral challenge | 2 | 2 | |

| immunology referral | 4 | 16 | |

| interview | 5 | 0 |

Interview refers to full allergy and medication history including the purpose-designed questionnaire.

These patients were found to have tolerated subsequent courses of penicillin prior to the interview.

Intervention outcomes for the study population with reference to reported reactions

| Reported reaction . | De-labelled, n = 199 . | Confirmed, n = 51 . | Total, n = 250 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rash | 64 | 5 | 69 |

| after oral challenge | 29 | 1 | |

| immunology referral | 2 | 4 | |

| interview | 33 | 0 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 43 | 0 | 43 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 43 | 0 | |

| Throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 2 | 24 | 26 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 2a | 24 | |

| Dizziness/headaches | 28 | 0 | 28 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 28 | 0 | |

| Hepatic derangements | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 8 | 0 | |

| Seizures | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 0 | |

| interview | 0 | 0 | |

| General swelling/oedema (excluding throat) | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 4 | |

| interview | 2 | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 39 | 0 | 39 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 39 | 0 | |

| Unsure | 11 | 18 | 29 |

| after oral challenge | 2 | 2 | |

| immunology referral | 4 | 16 | |

| interview | 5 | 0 |

| Reported reaction . | De-labelled, n = 199 . | Confirmed, n = 51 . | Total, n = 250 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rash | 64 | 5 | 69 |

| after oral challenge | 29 | 1 | |

| immunology referral | 2 | 4 | |

| interview | 33 | 0 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 43 | 0 | 43 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 43 | 0 | |

| Throat swelling/breathing difficulties | 2 | 24 | 26 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 2a | 24 | |

| Dizziness/headaches | 28 | 0 | 28 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 28 | 0 | |

| Hepatic derangements | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 8 | 0 | |

| Seizures | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 0 | |

| interview | 0 | 0 | |

| General swelling/oedema (excluding throat) | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 1 | 4 | |

| interview | 2 | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 39 | 0 | 39 |

| after oral challenge | 0 | 0 | |

| immunology referral | 0 | 0 | |

| interview | 39 | 0 | |

| Unsure | 11 | 18 | 29 |

| after oral challenge | 2 | 2 | |

| immunology referral | 4 | 16 | |

| interview | 5 | 0 |

Interview refers to full allergy and medication history including the purpose-designed questionnaire.

These patients were found to have tolerated subsequent courses of penicillin prior to the interview.

Fifty-one of 250 patients (20%) were referred to the immunology clinic for further assessment; 24 (47%) of these had their allergy label confirmed.

Oral challenges were performed for 34 of 250 patients (14%); 31 (91%) had no reaction and these patients were de-labelled. Three positive reactions occurred within the 72 h protocol time and were comparable with the patients’ original reported reactions (see Table 5). Positive reactions were validated by the pharmacist and clinical team.

Description of positive oral challenges for inpatients with confirmed allergy labels; original reported reactions are as stated by patients

| Patient . | Original reported reaction . | Protocol . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time until reactiona (h) . | cumulative amoxicillin dose given (mg) . | new reaction . | ||

| 1 | rash/itchiness | 29 | 1555 | itchiness |

| 2 | red rash/no itchiness | 27 | 1555 | redness on trunk |

| 3 | widespread rash | 42 | 1555 | rash/itchiness |

| Patient . | Original reported reaction . | Protocol . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time until reactiona (h) . | cumulative amoxicillin dose given (mg) . | new reaction . | ||

| 1 | rash/itchiness | 29 | 1555 | itchiness |

| 2 | red rash/no itchiness | 27 | 1555 | redness on trunk |

| 3 | widespread rash | 42 | 1555 | rash/itchiness |

Start time defined as time of first full dose of amoxicillin (500 mg) taken.

Description of positive oral challenges for inpatients with confirmed allergy labels; original reported reactions are as stated by patients

| Patient . | Original reported reaction . | Protocol . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time until reactiona (h) . | cumulative amoxicillin dose given (mg) . | new reaction . | ||

| 1 | rash/itchiness | 29 | 1555 | itchiness |

| 2 | red rash/no itchiness | 27 | 1555 | redness on trunk |

| 3 | widespread rash | 42 | 1555 | rash/itchiness |

| Patient . | Original reported reaction . | Protocol . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time until reactiona (h) . | cumulative amoxicillin dose given (mg) . | new reaction . | ||

| 1 | rash/itchiness | 29 | 1555 | itchiness |

| 2 | red rash/no itchiness | 27 | 1555 | redness on trunk |

| 3 | widespread rash | 42 | 1555 | rash/itchiness |

Start time defined as time of first full dose of amoxicillin (500 mg) taken.

The prevalence of reported penicillin allergy was 11% at Middlemore Hospital; our study showed a prevalence of study-confirmed allergy in 2% of patients.

Antibiotic use in hospital

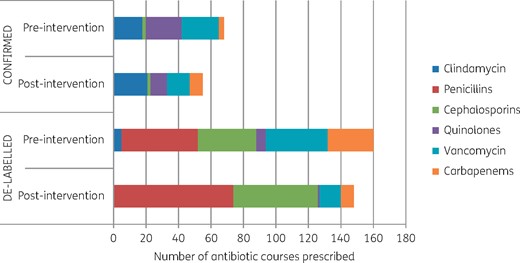

Antibiotics were prescribed in 192 patients at the time of admission. The investigating pharmacist recommended changing de-labelled patients to first-line antibiotics consistent with our local hospital guidelines. Of the patients requiring antibiotics, who were de-labelled as inpatients, 91 of 149 (61%) were not on first-line antibiotics. All recommended antibiotic changes were first discussed with the primary team and in all cases the recommendation was accepted. No de-labelled patients experienced a hypersensitivity reaction after antibiotics were changed in hospital. There was an overall reduction in antibiotic use before and after intervention in both groups with a significant association found between outcome of intervention and antibiotic usage (P < 0.001). The use of penicillins and cephalosporins increased significantly in the de-labelled group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.02, respectively), whereas the use of other agents decreased commensurately (Figure 3).

Antibiotic use in hospital before and after intervention. Confirmed allergy label refers to the patients with history strongly suggestive of an immediate allergic reaction, positive oral challenge or who were deemed to have had a confirmed allergy label after an allergy/immunology referral. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Follow-up

Patients were followed-up 1 year after intervention. Twenty-three of 250 patients were lost to follow-up (9%); 13 de-labelled patients and 10 confirmed allergic patients. Of the 186 de-labelled patients available for follow-up, 103 were prescribed an antibiotic in the year following intervention (55%). Three of 186 de-labelled patients (2%) experienced a delayed hypersensitivity reaction following repeat penicillin administration, similar to their original reported reaction (i.e. delayed-onset rash). These patients were relabelled and their electronic medical records amended by reinstating the reaction warning to identify a delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

Community antibiotic use

Community antibiotic use for 1 year before and after intervention was analysed. The total number of antibiotic courses was 270 pre-intervention versus 189 post-intervention for the de-labelled group and 233 versus 208 for the confirmed allergy group. The de-labelled group had a mean number of 1.9 courses of antibiotics prescribed in the year before the intervention, versus 1.8 courses prescribed in the year after the intervention (P = 0.58). The confirmed allergy group had a mean of 5.0 courses versus 4.6 courses before and after the intervention (P = 0.5). While the prescription of penicillin antibiotics in the year post-intervention did not change for the confirmed allergic group (zero courses before and after intervention), the prescription of penicillin antibiotics did change in the year after intervention in the de-labelled group. Penicillin antibiotics were prescribed for 75 of 270 courses (28%) pre-intervention compared with 118 of 189 courses (62%) post-intervention in this group (P < 0.0001).

Antibiotic cost

The drug-related cost per day per inpatient was NZD24.86 for confirmed allergic patients, compared with NZD15.96 for de-labelled patients, i.e. a 1.6 times greater cost per antibiotic per day for patients labelled as penicillin allergic. In the community, the theoretical cost associated with the preferred prescribed antibiotic was used to determine the difference in treating patients. The antibiotic cost per day per patient for confirmed allergic patients was 2.5 times greater than for de-labelled patients (NZD6.51 versus NZD16.43).

Length of hospital stay

Patients who were inaccurately labelled as allergic to penicillin had a median length of stay of 6 days (IQR = 2–8 days), compared with patients who were confirmed allergic (median = 9 days, IQR = 3–13.5 days, P = 0.0015). The median length of stay for acute adult admissions (medical and surgical) to Middlemore Hospital during the study period was 3.7 days.

Patients’ perceptions

Patients were asked on discharge how likely they were to take a penicillin antibiotic after the intervention. Of the de-labelled patients, 60% (119 of 199 patients) were happy to take a penicillin antibiotic and 29% (57 of 199 patients) would only take a penicillin antibiotic if there was no other option, with the remaining 12% (23 of 199 patients) still not comfortable with taking a penicillin antibiotic. At the 1 year follow-up, 85% (159 of 186) of de-labelled patients were agreeable to taking penicillin antibiotics.

Discussion

This prospective interventional study at a general public hospital showed that a specialist pharmacist could safely de-label 64% of patients with inappropriate penicillin allergy warnings through a combination of careful history and medication reconciliation. A further 12% could be de-labelled by a pharmacist using oral challenge, without the need for skin prick testing or formal allergy/immunology assessment. The process of pharmacist-led de-labelling was safe. Only three patients reacted to the oral challenge during its performance in hospital, with a 97% safety of de-labelling after 1 year of follow-up.

To our knowledge, this is the only pharmacist-led allergy management study that employed an oral challenge ahead of a penicillin skin test in selected patients, according to a carefully designed protocol. It is also the only study we are aware of that had a 1 year follow-up to show the safety of de-labelling and effect on future community prescribing.

There is a lack of confidence in assessing and evaluating allergy labels by medical professionals.25 Factors perpetuating an inaccurate allergy label for inpatients at busy public hospitals may include time pressures, lack of knowledge, level of seniority and experience of staff and lack of guidelines for the treatment of infections. Some consider history to be an unreliable method of excluding β-lactam allergy, with some experts advocating more rigorous evaluation.26,27 However, in our study, an accurate medication history confidently excluded immediate allergic reactions in a significant proportion of patients (79% of the de-labelled population). When questioned by a specialist pharmacist, the majority of patients (57%) in our study had no recall of details surrounding their initial reaction. Drug intolerance, e.g. nausea and vomiting unassociated with other symptoms, was reported as ‘allergies’ by 44% of the study population, whilst erythema or urticaria reactions were reported by 28% of patients, with only 10% reporting symptoms consistent with an immediate hypersensitivity reaction at the time of initial assessment.

Pharmacists are well placed to identify and assess hospital patients with reported allergy.24,28,29 The availability of pharmacists at the frontline of the hospital can afford the opportunity for integrated and proactive allergy assessment, impacting directly on antimicrobial stewardship and improving the use of first-line antibiotics. For example, the inpatient β-lactam use in our study population increased by 29% after the de-labelling of patients with inaccurate allergy labels, while the use of alternative antibiotics decreased commensurately. All recommendations for inpatient treatment made by the pharmacist were accepted and no patients had an adverse drug reaction during their treatment course. We were also able to show a reduction in both inpatient and outpatient drug costs associated with de-labelling patients with inaccurate penicillin allergy warnings.

Sixty-two percent of antibiotic courses prescribed to de-labelled patients in the year after intervention were penicillin antibiotics. This is significantly higher than penicillin antibiotic courses received prior to intervention. However, despite extensive interview and education by the investigating pharmacist, at 1 year post-intervention, 15% of de-labelled patients were still not comfortable taking penicillin antibiotics after the intervention. We did not further investigate the reasons for this reluctance.

There are various testing protocols suggested for patients with reported penicillin allergies. Most of these protocols utilize penicillin skin tests as the first step.18,30,31 Penicillin skin testing has several limitations: specialized equipment and training is required and not available at many hospitals, it is time-consuming (requiring at least 1 h to administer and read), there is low sensitivity for delayed hypersensitivity reactions19,32 and many medications with antihistaminic properties, often prescribed to inpatients, interfere with skin testing. Drug provocation testing or oral challenge is considered the gold standard, with good diagnostic value. It is usually only performed when penicillin skin tests are negative;31 however, oral challenge has been shown by other authors to be safe in patients at low risk of immediate hypersensitivity reactions.19,30 In this study, we used a standard protocolized approach offering oral challenges to patients who met set safety criteria (see Table 1). Amoxicillin was chosen as the penicillin of choice as it is most frequently involved in hypersensitivity reactions.19 We uneventfully de-labelled 91% of patients who underwent an oral challenge using this inpatient protocol. Those patients that did have a reaction experienced mild symptoms that were easily managed. None of our patients was noted as having haemolytic anaemia or serum sickness as allergic reactions; however, it should be noted that these patients are to be excluded from oral challenges.

We believe there are several strengths to this study. This is one of the largest studies investigating the impact of a pharmacist-led allergy assessment service. It was performed prospectively and enrolled a large number of patients in a large general public hospital without ready access to specialist allergy/immunology services and provides an excellent example of a ‘real-world’ intervention that was incorporated into the day-to-day work of an antimicrobial stewardship team.

There are some limitations to this study. The investigating pharmacist has specialist training in infectious diseases and antimicrobial stewardship and so may have expertise beyond that of general pharmacists. However, the protocol followed by the investigating pharmacist was drafted in consultation with infectious diseases and allergy/immunology specialists with safety being paramount. The intention was to design a clear, safe protocol that could be followed by pharmacists without specialized training. If there was any uncertainty about the allergy history, presentation or nature of the reaction, the patient case was referred to the allergy/immunology clinic for expert assessment. An overestimation of confirmed allergy may have resulted from the overcautious nature of our protocol; however, as this was pharmacist-led, we felt this to be an acceptable balance measure.

Another limitation is that we did not collect comorbidity data that may have directly impacted on antibiotic usage in the community and length of hospital admission.

Our oral challenge utilized a 24 h challenge period in patients who did not require continued treatment. Recent research has shown a longer drug challenge may reveal more patients with delayed hypersensitivity reactions, up to an increase of 45% after 3 days of oral challenge, and this prolonged oral challenge has subsequently been incorporated in our protocol.33

Conclusions

In conclusion, we believe that a standard protocol of investigating patients with penicillin allergy in a general hospital conducted by a trained pharmacist is safe and accurate and significantly contributes to better selection of antimicrobials for both inpatient and future community therapy without immediate recourse to specialized allergy/immunology assessment.

Acknowledgements

This study was presented as a poster at IDWeek 2016, New Orleans, LA, USA (Abstract 1853).

We thank the Departments of Pharmacy and Infectious Diseases of Middlemore Hospital for supporting this study.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of routine work; no additional funding was received for this study.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References

WHO. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance.

Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters.

Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters.