-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mercedes Delgado-Valverde, Adoración Valiente-Mendez, Eva Torres, Benito Almirante, Silvia Gómez-Zorrilla, Nuria Borrell, Ana Isabel Aller-García, Mercedes Gurgui, Manel Almela, Mercedes Sanz, Germán Bou, Luis Martínez-Martínez, Rafael Cantón, Jose Antonio Lepe, Manuel Causse, Belén Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, Álvaro Pascual, Jesús Rodríguez-Baño, on behalf of the REIPI/GEIH-SEIMC BACTERAEMIA-MIC Group, MIC of amoxicillin/clavulanate according to CLSI and EUCAST: discrepancies and clinical impact in patients with bloodstream infections due to Enterobacteriaceae, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 72, Issue 5, May 2017, Pages 1478–1487, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw562

Close - Share Icon Share

Objectives: To compare results of amoxicillin/clavulanate susceptibility testing using CLSI and EUCAST methodologies and to evaluate their impact on outcome in patients with bacteraemia caused by Enterobacteriaceae.

Patients and methods: A prospective observational cohort study was conducted in 13 Spanish hospitals. Patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae who received empirical intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment for at least 48 h were included. MICs were determined following CLSI and EUCAST recommendations. Outcome variables were: failure at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate (FEAMC); failure at day 21; and 30 day mortality. Classification and regression tree (CART) analysis and logistic regression were performed.

Results: Overall, 264 episodes were included; the urinary tract was the most common source (64.7%) and Escherichia coli the most frequent pathogen (76.5%). Fifty-two isolates (19.7%) showed resistance according to CLSI and 141 (53.4%) according to EUCAST. The kappa index for the concordance between the results of both committees was only 0.24. EUCAST-derived, but not CLSI-derived, MICs were associated with failure when considered as continuous variables. CART analysis suggested a ‘resistance’ breakpoint of > 8/4 mg/L for CLSI-derived MICs; it predicted FEAMC in adjusted analysis (OR = 1.96; 95% CI: 0.98–3.90). Isolates with EUCAST-derived MICs >16/2 mg/L independently predicted FEAMC (OR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.05–4.21) and failure at day 21 (OR= 3.01; 95% CI: 0.93–9.67). MICs >32/2 mg/L were only predictive of failure among patients with bacteraemia from urinary or biliary tract sources.

Conclusions: CLSI and EUCAST methodologies showed low agreement for determining the MIC of amoxicillin/clavulanate. EUCAST-derived MICs seemed more predictive of failure than CLSI-derived ones. EUCAST-derived MICs >16/2 mg/L were independently associated with therapeutic failure.

Introduction

Clinical breakpoints for the interpretation of antimicrobial susceptibility testing of microorganisms in the laboratory are set by international expert committees to help guide clinical decisions in antimicrobial therapy.1 EUCAST2 and CLSI3 use a range of information to do this, including: MIC distributions for large collections of microorganisms; genotypic resistance markers; pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the antimicrobials; and clinical outcomes observed in patients relative to MIC values, when available.1,4 Unfortunately, clinical data supporting the establishment of clinical breakpoints are usually lacking particularly for older drugs, so that in vitro data, animal experiments and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic stochastic models are frequently the only data available for these decisions.5

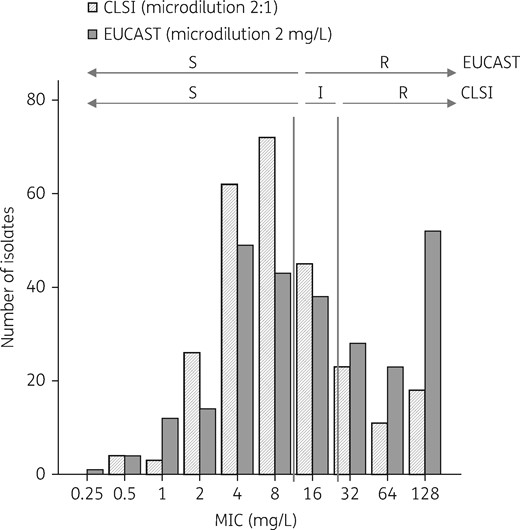

Amoxicillin/clavulanate is a broad-spectrum β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combination with activity against Gram-negative and -positive bacteria. EUCAST recommends using a fixed concentration of 2 mg/L clavulanate for susceptibility testing of the amoxicillin/clavulanate combination; Enterobacteriaceae with MICs ≤8/2 mg/L are considered as susceptible and those with MICs >8/2 mg/L are considered as resistant for invasive infections.2 CLSI recommends using a 2:1 ratio of amoxicillin/clavulanate, and considers Enterobacteriaceae with MICs ≤8/4 mg/L as susceptible, but classifies those with MICs 16/8 mg/L as intermediate and those with MICs ≥32/16 mg/L as resistant.3 The rationale for using a fixed concentration for clavulanate in EUCAST recommendations is based on the fact that a minimum concentration of the drug is needed to exert its inhibitory effect on β-lactamases; such concentrations would not be reached for low concentrations of amoxicillin if using a 2:1 ratio. Previous studies on Escherichia coli isolates have shown low agreement between the results obtained with the two methods, with EUCAST methodology providing higher rates of resistance;6,7 data on other Enterobacteriaceae and a more detailed analysis of the clinical implications of the results obtained using these two methods are needed.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of amoxicillin/clavulanate MIC values on the clinical outcome of patients with bacteraemia caused by Enterobacteriaceae when treated following the recommendations of these two methodologies.

Patients and methods

This study forms part of the Bacteraemia-MIC project, aimed at investigating the impact of the MICs of different antimicrobials on the outcome of bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae,8 and was designed as a prospective observational multicentre cohort study, conducted between January 2011 and December 2013 at 13 Spanish university hospitals belonging to the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI) (www.reipi.org). Patients aged >17 years with monomicrobial bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae, and monotherapy with a β-lactam or fluoroquinolone as initial treatment were identified by daily communication with the microbiology laboratory; patients were included in the Bacteraemia-MIC database if the first antibiotic dose was administered in the first 12 h after blood cultures were obtained and for at least 48 h. Patients with any of the following criteria were excluded: transient bacteraemia (occurring after an invasive procedure such as digestive tract endoscopy that cleared without treatment and had no complications); polymicrobial bacteraemia; non-hospitalized patients; patients with do-not-resuscitate orders; neutropenic patients (total neutrophil count <500/mm3); and survival <24 h after blood cultures were obtained. In this analysis, only patients initially treated with intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanate in monotherapy for at least 48 h were included; patients could be changed later to another antibiotic.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, which waived the need to obtain consent because of the observational nature of the study.

Variables and definitions

The outcome variables were: (i) clinical response at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate; (ii) clinical response at day 21, irrespective of whether amoxicillin/clavulanate continued for the full course of treatment or was changed to another antibiotic; and (iii) all-cause 30 day mortality.

Clinical response at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate was classified as: (i) ‘clinical cure’ if all symptoms and signs of infection were completely resolved and no further antibiotics were needed; (ii) ‘improvement’ if all symptoms and signs of infection were completely or partially resolved and antibiotic therapy for the episode was continued with another drug because of one of the following reasons: (a) de-escalation, (b) switch to an oral drug, (c) change to a more convenient parenteral drug for outpatient therapy, or (d) reported in vitro resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate; and (iii) ‘failure’, if a switch to, or addition of, another antibiotic was needed because infection-related symptoms or signs worsened or persisted, or death from any cause occurred. Clinical response at day 21 was classified as: (i) ‘clinical cure’ if all symptoms and signs of infection were completely resolved and all antibiotics were stopped; (ii) ‘improvement’ if symptoms and signs of infection improved, but had not completely resolved; and (iii) ‘failure’ if there were persistent, recurrent or new symptoms or signs present related to the infection, or death occurred. Clinical response at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at day 21 was determined by a trained clinical investigator at each site; however, because of the subjectivity of this endpoint, one investigator (J. R. B.), blinded with respect to exposure (MIC of amoxicillin/clavulanate), assessed the clinical response data of all cases according to vital signs, evolution of Pitt9,10 and SOFA11 scores, and laboratory data at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at day 21. When the assessment of clinical response made by the blind investigator differed from the one indicated by the local investigator, a query was sent to the local team with the indication to review the case, and agreement was reached based on available data.

Data collected included: patient demographics; height; weight; site of acquisition, classified as community, healthcare-associated or nosocomial according to Friedman’s criteria;12 chronic underlying diseases; severity of underlying condition according to the Charlson score13 and McCabe classification;14 severity of acute condition according to Pitt and SOFA scores; invasive procedures; source of bacteraemia according to standard clinical and microbiological criteria;15 severity of systemic inflammatory response syndrome at presentation, classified as sepsis, severe sepsis or shock; baseline creatinine level; aetiology; treatment; and outcome. Vital signs were recorded daily, if available, until day 7, and thereafter weekly; Pitt and SOFA scores were recorded at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at days 14 and 21, and all key laboratory data were recorded as available. Patients were followed for 1 month after the onset of bacteraemia to assess clinical outcome, including mortality.

Microbiological studies

The first blood isolate from each patient was frozen at −80ºC and sent to the reference laboratory (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena), where identification was confirmed and the amoxicillin/clavulanate MIC for each isolate was determined by manual broth microdilution following EUCAST and CLSI methodologies.16,17 Briefly, amoxicillin (Sigma–Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) MICs in the presence of potassium salt clavulanate (Sigma–Aldrich) were determined by standard broth microdilution (BBL–Mueller–Hinton II cation-adjusted broth; Becton-Dickinson, Madrid, Spain). For the EUCAST methodology, panels were freshly prepared with a range of concentrations of amoxicillin, from 0.03 to 64 mg/L, and a fixed 2 mg/L concentration of clavulanate, while for CLSI, the panels were freshly prepared using amoxicillin/clavulanate in a 2:1 ratio with the same range of concentrations. E. coli ATCC 25922 and E. coli ATCC 35218 were used as the control strain in microdilution. The reading of the results was performed fully manually by three independent researchers.

ESBL production was determined by standard phenotypic methods.18,19 PCR assays were used to characterize β-lactamase genes. PCR conditions and previously described group-specific primers covering the most frequent ESBLs in our area (SHV,20 CTX-M-9,21 CTX-M-122 and TEM20) were used to amplify the bla genes, and the amplicons were sequenced. When OXA-1 production was suspected, the presence was determined by PCR with specific primers.23

Statistical analysis

Discrepancies between susceptibility methods were analysed by means of essential and categorical agreement. Essential agreement referred to amoxicillin concentration and was considered when the same MIC values (±1 dilution) were obtained for both microdilution methods, using EUCAST as the reference. The kappa index was used to evaluate concordance.24 For categorical agreement, MICs were classified into clinical categories according to EUCAST and CLSI interpretive criteria;19,25 very major, major and minor errors were calculated according to established guidelines, with EUCAST considered as the reference method.26

For analysis of the independent impact of MIC breakpoints on outcome, a univariate analysis of associated variables was first performed; proportions were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. MIC breakpoints potentially predictive of clinical outcomes were initially explored by classification and regression tree (CART) analysis (CART software 7.0, Salford Systems) for both CLSI- and EUCAST-derived MICs once converted into their base 2 logs; however, the different breakpoints recommended by CLSI and EUCAST, as well as others, were also tested. The independent association between MIC values (base 2 log) or specific breakpoints and the different outcomes were assessed by multivariate logistic regression. Potential confounders (age, Charlson index, Pitt score, presentation with severe sepsis or shock, source, Enterobacteriaceae and site) were included in the models if their univariate P value was <0.1. To control for the site effect, participating centres were classified into those with lower and higher rates of the different outcomes after considering all other variables using TreeNet (Salford Systems). Interaction between MIC breakpoints and source was also investigated. The variables in the final model were selected by a stepwise backward procedure; variables with P < 0.1 were kept in the models. The MIC breakpoint was always kept. Subgroup analyses of patients with and without a urinary tract source, and with urinary or biliary tract sources were also performed. All analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0.

Results

Description of the cohort

During the study period, 1058 episodes of bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae were included in the Bacteraemia-MIC cohort. Of these, 264 were initially treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate and included in this analysis. Demographic, epidemiological, clinical and microbiological data and the outcomes of episodes are shown in Table 1. The most common source of bacteraemia was the urinary tract. E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were the most frequent pathogens. ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae were identified in 15 (5.7%) episodes: nine were E. coli, five K. pneumoniae and one Proteus mirabilis (4.5%, 14.7% and 9.1% of total specific species, respectively). The ESBL genes were blaCTX-M-15 (seven isolates), blaCTX-M-14 (two), blaCTX-M-1 (one) and blaSHV-12 (five). The OXA-1 gene was detected in five (1.9%) isolates, all of which were also ESBL producers (four E. coli and one K. pneumoniae).

Characteristics, clinical features and outcomes of patients with bloodstream infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate according to CART-derived breakpoints for both CLSI and EUCAST methods

| Variable . | All isolates (N = 264) . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | MIC (mg/L) . | ||||

| ≤8/4 (N = 167) . | >8/4 (N = 97) . | ≤32/2 (N = 189) . | >32/2 (N = 75) . | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 75 (64–82) | 75 (65–82) | 76 (64–84) | 76 (65–83) | 75 (63–80) |

| Male | 123 (46.6) | 73 (43.7) | 50 (51.5) | 84 (44.4) | 39 (52.0) |

| Hospital-acquired episode | 109 (41.3) | 60 (35.9) | 49 (50.5)a | 68 (36.0) | 41 (54.7)a |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| diabetes mellitus | 86 (32.6) | 58 (34.7) | 28 (28.9) | 68 (36.0) | 18 (24.0) |

| chronic pulmonary disease | 42 (15.9) | 26 (15.6) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 13 (17.3) |

| congestive heart failure | 27 (10.2) | 17 (10.2) | 10 (10.3) | 20 (10.6) | 7 (9.3) |

| malignancy | 47 (17.8) | 28 (16.8) | 19 (19.6) | 30 (15.9) | 17 (22.7) |

| renal failure (end-stage renal disease) | 35 (13.3) | 18 (10.8) | 17 (17.5) | 21 (11.1) | 14 (18.7) |

| liver cirrhosis | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.7) |

| immunocompromised | 22 (8.3) | 13 (7.8) | 9 (9.3) | 13 (6.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| Ultimately or rapidly fatal disease (according to McCabe classification) | 62 (23.5) | 36 (21.6) | 26 (26.8) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| Age-weighted Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 2 (0.5–3) | 2 (0–4) |

| Pitt score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Previous invasive procedures | |||||

| mechanical ventilation | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| major surgery | 21 (8.0) | 9 (5.4) | 12 (12.4)a | 10 (5.3) | 11 (14.7)a |

| urinary catheter | 34 (12.9) | 17 (10.2) | 17 (17.5) | 16 (8.5) | 18 (24.0)a |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 49 (18.6) | 28 (16.8) | 21 (21.6) | 30 (15.9) | 19 (25.3) |

| Source of bloodstream infections | |||||

| urinary tract | 171 (64.7) | 105 (62.9) | 67 (69.1) | 125 (66.1) | 47 (62.7) |

| biliary tract | 44 (16.7) | 33 (19.8) | 11 (11.3) | 34 (18.0) | 10 (13.3) |

| abdominal | 14 (5.3) | 9 (5.4) | 5 (5.2) | 8 (4.2) | 6 (8.0) |

| vascular catheter | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.0) |

| respiratory | 7 (2.7) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (2.7) |

| others | 22 (8.3) | 15 (9.0) | 7 (7.2) | 15 (7.9) | 7 (9.3) |

| Aetiology | |||||

| E. coli | 202 (76.5) | 130 (77.8) | 72 (74.2) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| K. pneumoniae | 34 (12.9) | 25 (15.0) | 9 (9.3) | 26 (13.8) | 8 (10.7) |

| K. oxytoca | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) |

| E. cloacae | 7 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.2)a | 0 (0) | 7 (9.3)a |

| P. mirabilis | 11 (4.2) | 10 (6.0) | 1 (1.0) | 10 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| S. marcescens | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.1)a | 0 (0) | 3 (4.0)a |

| others | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1)a | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| ESBL producer | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| OXA-1 producer | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.2)a | 6 (3.2) | 6 (12.0)a |

| Reason for changing amoxicillin/clavulanate to another antibiotic | |||||

| resistance | 41 (15.5) | 0 (0) | 41 (42.3)a | 3 (1.6) | 38 (50.7)a |

| de-escalation | 39 (14.8) | 29 (17.4) | 10 (10.3) | 30 (15.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| unsatisfactory evolution | 31 (11.7) | 19 (11.4) | 12 (12.4) | 20 (10.6) | 11 (14.7) |

| Dose | |||||

| 1.2 g/8 h | 210 (79.5) | 135 (80.8) | 75 (77.3) | 154 (81.5) | 56 (74.7) |

| 2.2 g/8 h | 23 (8.7) | 17 (10.2) | 6 (6.2) | 18 (9.5) | 5 (6.7) |

| others | 31 (11.7) | 15 (9.0) | 16 (16.5) | 15 (8.0) | 14 (18.7)a |

| Outcome at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate | |||||

| clinical cure | 115 (43.6) | 82 (49.1) | 33 (34.0)a | 91 (48.1) | 24 (32.0)a |

| improvement | 105 (39.8) | 63 (37.7) | 42 (43.3) | 74 (39.2) | 31 (41.3) |

| failure | 44 (16.7) | 22 (13.2) | 22 (22.7)a | 24 (12.7) | 20 (26.7)a |

| Outcome at day 21 | |||||

| clinical cure | 208 (78.8) | 135 (80.8) | 73 (75.3) | 154 (81.5) | 54 (72.0) |

| improvement | 41 (15.5) | 25 (15.0) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 12 (16.0) |

| failure | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (12.0)a |

| Mortality at day 30 | 19 (7.2) | 12 (7.2) | 7 (7.2) | 11 (5.8) | 8 (10.7) |

| Variable . | All isolates (N = 264) . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | MIC (mg/L) . | ||||

| ≤8/4 (N = 167) . | >8/4 (N = 97) . | ≤32/2 (N = 189) . | >32/2 (N = 75) . | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 75 (64–82) | 75 (65–82) | 76 (64–84) | 76 (65–83) | 75 (63–80) |

| Male | 123 (46.6) | 73 (43.7) | 50 (51.5) | 84 (44.4) | 39 (52.0) |

| Hospital-acquired episode | 109 (41.3) | 60 (35.9) | 49 (50.5)a | 68 (36.0) | 41 (54.7)a |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| diabetes mellitus | 86 (32.6) | 58 (34.7) | 28 (28.9) | 68 (36.0) | 18 (24.0) |

| chronic pulmonary disease | 42 (15.9) | 26 (15.6) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 13 (17.3) |

| congestive heart failure | 27 (10.2) | 17 (10.2) | 10 (10.3) | 20 (10.6) | 7 (9.3) |

| malignancy | 47 (17.8) | 28 (16.8) | 19 (19.6) | 30 (15.9) | 17 (22.7) |

| renal failure (end-stage renal disease) | 35 (13.3) | 18 (10.8) | 17 (17.5) | 21 (11.1) | 14 (18.7) |

| liver cirrhosis | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.7) |

| immunocompromised | 22 (8.3) | 13 (7.8) | 9 (9.3) | 13 (6.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| Ultimately or rapidly fatal disease (according to McCabe classification) | 62 (23.5) | 36 (21.6) | 26 (26.8) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| Age-weighted Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 2 (0.5–3) | 2 (0–4) |

| Pitt score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Previous invasive procedures | |||||

| mechanical ventilation | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| major surgery | 21 (8.0) | 9 (5.4) | 12 (12.4)a | 10 (5.3) | 11 (14.7)a |

| urinary catheter | 34 (12.9) | 17 (10.2) | 17 (17.5) | 16 (8.5) | 18 (24.0)a |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 49 (18.6) | 28 (16.8) | 21 (21.6) | 30 (15.9) | 19 (25.3) |

| Source of bloodstream infections | |||||

| urinary tract | 171 (64.7) | 105 (62.9) | 67 (69.1) | 125 (66.1) | 47 (62.7) |

| biliary tract | 44 (16.7) | 33 (19.8) | 11 (11.3) | 34 (18.0) | 10 (13.3) |

| abdominal | 14 (5.3) | 9 (5.4) | 5 (5.2) | 8 (4.2) | 6 (8.0) |

| vascular catheter | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.0) |

| respiratory | 7 (2.7) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (2.7) |

| others | 22 (8.3) | 15 (9.0) | 7 (7.2) | 15 (7.9) | 7 (9.3) |

| Aetiology | |||||

| E. coli | 202 (76.5) | 130 (77.8) | 72 (74.2) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| K. pneumoniae | 34 (12.9) | 25 (15.0) | 9 (9.3) | 26 (13.8) | 8 (10.7) |

| K. oxytoca | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) |

| E. cloacae | 7 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.2)a | 0 (0) | 7 (9.3)a |

| P. mirabilis | 11 (4.2) | 10 (6.0) | 1 (1.0) | 10 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| S. marcescens | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.1)a | 0 (0) | 3 (4.0)a |

| others | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1)a | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| ESBL producer | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| OXA-1 producer | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.2)a | 6 (3.2) | 6 (12.0)a |

| Reason for changing amoxicillin/clavulanate to another antibiotic | |||||

| resistance | 41 (15.5) | 0 (0) | 41 (42.3)a | 3 (1.6) | 38 (50.7)a |

| de-escalation | 39 (14.8) | 29 (17.4) | 10 (10.3) | 30 (15.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| unsatisfactory evolution | 31 (11.7) | 19 (11.4) | 12 (12.4) | 20 (10.6) | 11 (14.7) |

| Dose | |||||

| 1.2 g/8 h | 210 (79.5) | 135 (80.8) | 75 (77.3) | 154 (81.5) | 56 (74.7) |

| 2.2 g/8 h | 23 (8.7) | 17 (10.2) | 6 (6.2) | 18 (9.5) | 5 (6.7) |

| others | 31 (11.7) | 15 (9.0) | 16 (16.5) | 15 (8.0) | 14 (18.7)a |

| Outcome at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate | |||||

| clinical cure | 115 (43.6) | 82 (49.1) | 33 (34.0)a | 91 (48.1) | 24 (32.0)a |

| improvement | 105 (39.8) | 63 (37.7) | 42 (43.3) | 74 (39.2) | 31 (41.3) |

| failure | 44 (16.7) | 22 (13.2) | 22 (22.7)a | 24 (12.7) | 20 (26.7)a |

| Outcome at day 21 | |||||

| clinical cure | 208 (78.8) | 135 (80.8) | 73 (75.3) | 154 (81.5) | 54 (72.0) |

| improvement | 41 (15.5) | 25 (15.0) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 12 (16.0) |

| failure | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (12.0)a |

| Mortality at day 30 | 19 (7.2) | 12 (7.2) | 7 (7.2) | 11 (5.8) | 8 (10.7) |

Data are expressed as number of patients (%) except where specified.

P < 0.05.

Characteristics, clinical features and outcomes of patients with bloodstream infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate according to CART-derived breakpoints for both CLSI and EUCAST methods

| Variable . | All isolates (N = 264) . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | MIC (mg/L) . | ||||

| ≤8/4 (N = 167) . | >8/4 (N = 97) . | ≤32/2 (N = 189) . | >32/2 (N = 75) . | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 75 (64–82) | 75 (65–82) | 76 (64–84) | 76 (65–83) | 75 (63–80) |

| Male | 123 (46.6) | 73 (43.7) | 50 (51.5) | 84 (44.4) | 39 (52.0) |

| Hospital-acquired episode | 109 (41.3) | 60 (35.9) | 49 (50.5)a | 68 (36.0) | 41 (54.7)a |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| diabetes mellitus | 86 (32.6) | 58 (34.7) | 28 (28.9) | 68 (36.0) | 18 (24.0) |

| chronic pulmonary disease | 42 (15.9) | 26 (15.6) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 13 (17.3) |

| congestive heart failure | 27 (10.2) | 17 (10.2) | 10 (10.3) | 20 (10.6) | 7 (9.3) |

| malignancy | 47 (17.8) | 28 (16.8) | 19 (19.6) | 30 (15.9) | 17 (22.7) |

| renal failure (end-stage renal disease) | 35 (13.3) | 18 (10.8) | 17 (17.5) | 21 (11.1) | 14 (18.7) |

| liver cirrhosis | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.7) |

| immunocompromised | 22 (8.3) | 13 (7.8) | 9 (9.3) | 13 (6.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| Ultimately or rapidly fatal disease (according to McCabe classification) | 62 (23.5) | 36 (21.6) | 26 (26.8) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| Age-weighted Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 2 (0.5–3) | 2 (0–4) |

| Pitt score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Previous invasive procedures | |||||

| mechanical ventilation | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| major surgery | 21 (8.0) | 9 (5.4) | 12 (12.4)a | 10 (5.3) | 11 (14.7)a |

| urinary catheter | 34 (12.9) | 17 (10.2) | 17 (17.5) | 16 (8.5) | 18 (24.0)a |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 49 (18.6) | 28 (16.8) | 21 (21.6) | 30 (15.9) | 19 (25.3) |

| Source of bloodstream infections | |||||

| urinary tract | 171 (64.7) | 105 (62.9) | 67 (69.1) | 125 (66.1) | 47 (62.7) |

| biliary tract | 44 (16.7) | 33 (19.8) | 11 (11.3) | 34 (18.0) | 10 (13.3) |

| abdominal | 14 (5.3) | 9 (5.4) | 5 (5.2) | 8 (4.2) | 6 (8.0) |

| vascular catheter | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.0) |

| respiratory | 7 (2.7) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (2.7) |

| others | 22 (8.3) | 15 (9.0) | 7 (7.2) | 15 (7.9) | 7 (9.3) |

| Aetiology | |||||

| E. coli | 202 (76.5) | 130 (77.8) | 72 (74.2) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| K. pneumoniae | 34 (12.9) | 25 (15.0) | 9 (9.3) | 26 (13.8) | 8 (10.7) |

| K. oxytoca | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) |

| E. cloacae | 7 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.2)a | 0 (0) | 7 (9.3)a |

| P. mirabilis | 11 (4.2) | 10 (6.0) | 1 (1.0) | 10 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| S. marcescens | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.1)a | 0 (0) | 3 (4.0)a |

| others | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1)a | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| ESBL producer | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| OXA-1 producer | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.2)a | 6 (3.2) | 6 (12.0)a |

| Reason for changing amoxicillin/clavulanate to another antibiotic | |||||

| resistance | 41 (15.5) | 0 (0) | 41 (42.3)a | 3 (1.6) | 38 (50.7)a |

| de-escalation | 39 (14.8) | 29 (17.4) | 10 (10.3) | 30 (15.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| unsatisfactory evolution | 31 (11.7) | 19 (11.4) | 12 (12.4) | 20 (10.6) | 11 (14.7) |

| Dose | |||||

| 1.2 g/8 h | 210 (79.5) | 135 (80.8) | 75 (77.3) | 154 (81.5) | 56 (74.7) |

| 2.2 g/8 h | 23 (8.7) | 17 (10.2) | 6 (6.2) | 18 (9.5) | 5 (6.7) |

| others | 31 (11.7) | 15 (9.0) | 16 (16.5) | 15 (8.0) | 14 (18.7)a |

| Outcome at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate | |||||

| clinical cure | 115 (43.6) | 82 (49.1) | 33 (34.0)a | 91 (48.1) | 24 (32.0)a |

| improvement | 105 (39.8) | 63 (37.7) | 42 (43.3) | 74 (39.2) | 31 (41.3) |

| failure | 44 (16.7) | 22 (13.2) | 22 (22.7)a | 24 (12.7) | 20 (26.7)a |

| Outcome at day 21 | |||||

| clinical cure | 208 (78.8) | 135 (80.8) | 73 (75.3) | 154 (81.5) | 54 (72.0) |

| improvement | 41 (15.5) | 25 (15.0) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 12 (16.0) |

| failure | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (12.0)a |

| Mortality at day 30 | 19 (7.2) | 12 (7.2) | 7 (7.2) | 11 (5.8) | 8 (10.7) |

| Variable . | All isolates (N = 264) . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | MIC (mg/L) . | ||||

| ≤8/4 (N = 167) . | >8/4 (N = 97) . | ≤32/2 (N = 189) . | >32/2 (N = 75) . | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 75 (64–82) | 75 (65–82) | 76 (64–84) | 76 (65–83) | 75 (63–80) |

| Male | 123 (46.6) | 73 (43.7) | 50 (51.5) | 84 (44.4) | 39 (52.0) |

| Hospital-acquired episode | 109 (41.3) | 60 (35.9) | 49 (50.5)a | 68 (36.0) | 41 (54.7)a |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| diabetes mellitus | 86 (32.6) | 58 (34.7) | 28 (28.9) | 68 (36.0) | 18 (24.0) |

| chronic pulmonary disease | 42 (15.9) | 26 (15.6) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 13 (17.3) |

| congestive heart failure | 27 (10.2) | 17 (10.2) | 10 (10.3) | 20 (10.6) | 7 (9.3) |

| malignancy | 47 (17.8) | 28 (16.8) | 19 (19.6) | 30 (15.9) | 17 (22.7) |

| renal failure (end-stage renal disease) | 35 (13.3) | 18 (10.8) | 17 (17.5) | 21 (11.1) | 14 (18.7) |

| liver cirrhosis | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.7) |

| immunocompromised | 22 (8.3) | 13 (7.8) | 9 (9.3) | 13 (6.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| Ultimately or rapidly fatal disease (according to McCabe classification) | 62 (23.5) | 36 (21.6) | 26 (26.8) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| Age-weighted Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 2 (0.5–3) | 2 (0–4) |

| Pitt score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Previous invasive procedures | |||||

| mechanical ventilation | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| major surgery | 21 (8.0) | 9 (5.4) | 12 (12.4)a | 10 (5.3) | 11 (14.7)a |

| urinary catheter | 34 (12.9) | 17 (10.2) | 17 (17.5) | 16 (8.5) | 18 (24.0)a |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 49 (18.6) | 28 (16.8) | 21 (21.6) | 30 (15.9) | 19 (25.3) |

| Source of bloodstream infections | |||||

| urinary tract | 171 (64.7) | 105 (62.9) | 67 (69.1) | 125 (66.1) | 47 (62.7) |

| biliary tract | 44 (16.7) | 33 (19.8) | 11 (11.3) | 34 (18.0) | 10 (13.3) |

| abdominal | 14 (5.3) | 9 (5.4) | 5 (5.2) | 8 (4.2) | 6 (8.0) |

| vascular catheter | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.0) |

| respiratory | 7 (2.7) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (2.7) |

| others | 22 (8.3) | 15 (9.0) | 7 (7.2) | 15 (7.9) | 7 (9.3) |

| Aetiology | |||||

| E. coli | 202 (76.5) | 130 (77.8) | 72 (74.2) | 152 (80.4) | 50 (66.7)a |

| K. pneumoniae | 34 (12.9) | 25 (15.0) | 9 (9.3) | 26 (13.8) | 8 (10.7) |

| K. oxytoca | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) |

| E. cloacae | 7 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.2)a | 0 (0) | 7 (9.3)a |

| P. mirabilis | 11 (4.2) | 10 (6.0) | 1 (1.0) | 10 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| S. marcescens | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.1)a | 0 (0) | 3 (4.0)a |

| others | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (4.1)a | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| ESBL producer | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7)a |

| OXA-1 producer | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.2)a | 6 (3.2) | 6 (12.0)a |

| Reason for changing amoxicillin/clavulanate to another antibiotic | |||||

| resistance | 41 (15.5) | 0 (0) | 41 (42.3)a | 3 (1.6) | 38 (50.7)a |

| de-escalation | 39 (14.8) | 29 (17.4) | 10 (10.3) | 30 (15.9) | 9 (12.0) |

| unsatisfactory evolution | 31 (11.7) | 19 (11.4) | 12 (12.4) | 20 (10.6) | 11 (14.7) |

| Dose | |||||

| 1.2 g/8 h | 210 (79.5) | 135 (80.8) | 75 (77.3) | 154 (81.5) | 56 (74.7) |

| 2.2 g/8 h | 23 (8.7) | 17 (10.2) | 6 (6.2) | 18 (9.5) | 5 (6.7) |

| others | 31 (11.7) | 15 (9.0) | 16 (16.5) | 15 (8.0) | 14 (18.7)a |

| Outcome at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate | |||||

| clinical cure | 115 (43.6) | 82 (49.1) | 33 (34.0)a | 91 (48.1) | 24 (32.0)a |

| improvement | 105 (39.8) | 63 (37.7) | 42 (43.3) | 74 (39.2) | 31 (41.3) |

| failure | 44 (16.7) | 22 (13.2) | 22 (22.7)a | 24 (12.7) | 20 (26.7)a |

| Outcome at day 21 | |||||

| clinical cure | 208 (78.8) | 135 (80.8) | 73 (75.3) | 154 (81.5) | 54 (72.0) |

| improvement | 41 (15.5) | 25 (15.0) | 16 (16.5) | 29 (15.3) | 12 (16.0) |

| failure | 15 (5.7) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (12.0)a |

| Mortality at day 30 | 19 (7.2) | 12 (7.2) | 7 (7.2) | 11 (5.8) | 8 (10.7) |

Data are expressed as number of patients (%) except where specified.

P < 0.05.

The median duration of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate was 4 days for 135 patients who were changed to another drug and 11 days for those treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate for the whole course of treatment. The most frequent dose was 1 g of amoxicillin plus 0.2 g of clavulanate (1.2 g) every 8 h intravenously; we have no information about the reasons why some patients were administered 2.2 g every 8 h; finally, some patients received other doses because of adjustments due to renal insufficiency. The most common reasons for switching from amoxicillin/clavulanate to another drug were: report of resistance, 41 patients (15.5%); de-escalation, 39 patients (14.8%); and unsatisfactory clinical evolution, 31 patients (11.7%). The most frequently used antibiotics after amoxicillin/clavulanate were cephalosporins (31.1%), fluoroquinolones (29.6%), carbapenems (20.7%) and piperacillin/tazobactam (13.3%).

MIC distributions and concordance between CLSI and EUCAST methodologies

MIC distribution of amoxicillin/clavulanate for all isolates according to the method used: microdilution with a 2:1 amoxicillin/clavulanate ratio (CLSI) and microdilution with fixed 2 mg/L clavulanate (EUCAST). I, intermediate; R, resistant; S, susceptible.

The data for specific microorganisms are shown in Table 2. E. coli and Klebsiella spp. were more frequently considered resistant by EUCAST than by CLSI, although Proteus spp. was more frequently susceptible. All other Enterobacteriaceae were resistant by both methods.

Distribution of Enterobacteriaceae causing bacteraemia, according to EUCAST and CLSI criteria for susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanate

| . | . | Susceptible . | Intermediate . | Resistant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All isolates (n = 264) | EUCAST | 123 (46.6) | – | 141 (53.4) |

| CLSI | 167 (63.3) | 45 (17.0) | 52 (19.7) | |

| E. coli (n = 202) | EUCAST | 91 (45.0) | – | 111 (55.0) |

| CLSI | 130 (64.4) | 42 (20.8) | 30 (14.8) | |

| Klebsiella spp. (n = 36) | EUCAST | 24 (66.7) | – | 12 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 26 (72.3) | 3 (8.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Proteus spp. (n = 12) | EUCAST | 8 (66.7) | – | 4 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 11 (91.7) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | |

| Other (n = 14)a | EUCAST | 0 | – | 14 (100) |

| CLSI | 0 | 0 | 14 (100) |

| . | . | Susceptible . | Intermediate . | Resistant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All isolates (n = 264) | EUCAST | 123 (46.6) | – | 141 (53.4) |

| CLSI | 167 (63.3) | 45 (17.0) | 52 (19.7) | |

| E. coli (n = 202) | EUCAST | 91 (45.0) | – | 111 (55.0) |

| CLSI | 130 (64.4) | 42 (20.8) | 30 (14.8) | |

| Klebsiella spp. (n = 36) | EUCAST | 24 (66.7) | – | 12 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 26 (72.3) | 3 (8.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Proteus spp. (n = 12) | EUCAST | 8 (66.7) | – | 4 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 11 (91.7) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | |

| Other (n = 14)a | EUCAST | 0 | – | 14 (100) |

| CLSI | 0 | 0 | 14 (100) |

Data are presented as number of isolates (%).

Enterobacter spp. (8), Serratia spp. (4) and Morganella morgannii (2).

Distribution of Enterobacteriaceae causing bacteraemia, according to EUCAST and CLSI criteria for susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanate

| . | . | Susceptible . | Intermediate . | Resistant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All isolates (n = 264) | EUCAST | 123 (46.6) | – | 141 (53.4) |

| CLSI | 167 (63.3) | 45 (17.0) | 52 (19.7) | |

| E. coli (n = 202) | EUCAST | 91 (45.0) | – | 111 (55.0) |

| CLSI | 130 (64.4) | 42 (20.8) | 30 (14.8) | |

| Klebsiella spp. (n = 36) | EUCAST | 24 (66.7) | – | 12 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 26 (72.3) | 3 (8.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Proteus spp. (n = 12) | EUCAST | 8 (66.7) | – | 4 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 11 (91.7) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | |

| Other (n = 14)a | EUCAST | 0 | – | 14 (100) |

| CLSI | 0 | 0 | 14 (100) |

| . | . | Susceptible . | Intermediate . | Resistant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All isolates (n = 264) | EUCAST | 123 (46.6) | – | 141 (53.4) |

| CLSI | 167 (63.3) | 45 (17.0) | 52 (19.7) | |

| E. coli (n = 202) | EUCAST | 91 (45.0) | – | 111 (55.0) |

| CLSI | 130 (64.4) | 42 (20.8) | 30 (14.8) | |

| Klebsiella spp. (n = 36) | EUCAST | 24 (66.7) | – | 12 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 26 (72.3) | 3 (8.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Proteus spp. (n = 12) | EUCAST | 8 (66.7) | – | 4 (33.3) |

| CLSI | 11 (91.7) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | |

| Other (n = 14)a | EUCAST | 0 | – | 14 (100) |

| CLSI | 0 | 0 | 14 (100) |

Data are presented as number of isolates (%).

Enterobacter spp. (8), Serratia spp. (4) and Morganella morgannii (2).

We analysed the crude outcomes of patients with bacteraemia due to isolates with concordant and discrepant categories. The rate of failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment was 13.1% (16 of 122) for patients with isolates classified as susceptible and 23.5% (12 of 51) for those classified as resistant by both CLSI and EUCAST [relative risk (RR) = 1.76; 95% CI: 0.90–3.45; P = 0.09]. The failure rate for isolates classified as susceptible or intermediate by CLSI and resistant by EUCAST lay between the two [17.8% (16 of 90)]. All failures among discrepant isolates occurred in those with MICs of 8/4 or 16/8 mg/L by CLSI. The results were similar for failure at day 21 (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Association of CLSI-derived MICs and outcomes

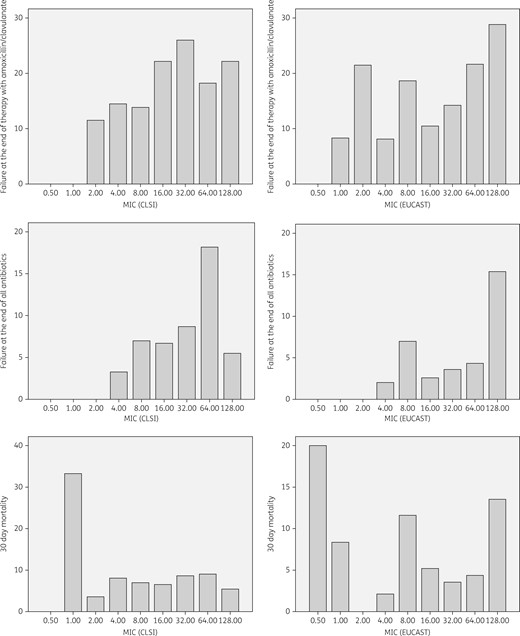

Outcome of patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate according to MIC, as determined by CLSI or EUCAST. Data are presented as percentage of patients with the specified outcome. Numbers of patients at each MIC value are specified in Table 3.

Crude outcomes of patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate, by MIC and category, according to CLSI and EUCAST methods

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . |

| ≤1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.8) |

| 2 | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 9 (14.5) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| 8 | 10 (13.9) | 5 (6.9) | 5 (6.9) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.6) |

| 16 | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) |

| 32 | 6 (26.1) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| >32 | 6 (20.7) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) | 20 (26.7) | 9 (12.0) | 8 (10.7) |

| Category | ||||||

| susceptible | 22 (13.2)a | 7 (4.2)c | 12 (7.2)e | 16 (13.0)g | 4 (3.3)h | 8 (6.5)i |

| intermediate | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | – | – | – |

| resistant | 12 (23.2)b | 5 (9.6)d | 4 (7.7)f | 28 (19.9) | 11 (7.8) | 11 (7.8) |

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . |

| ≤1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.8) |

| 2 | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 9 (14.5) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| 8 | 10 (13.9) | 5 (6.9) | 5 (6.9) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.6) |

| 16 | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) |

| 32 | 6 (26.1) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| >32 | 6 (20.7) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) | 20 (26.7) | 9 (12.0) | 8 (10.7) |

| Category | ||||||

| susceptible | 22 (13.2)a | 7 (4.2)c | 12 (7.2)e | 16 (13.0)g | 4 (3.3)h | 8 (6.5)i |

| intermediate | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | – | – | – |

| resistant | 12 (23.2)b | 5 (9.6)d | 4 (7.7)f | 28 (19.9) | 11 (7.8) | 11 (7.8) |

Data are presented as number of patients (%).

Comparisons of outcomes (Fisher test):

susceptible versus intermediate and resistant, P = 0.06;

resistant versus susceptible and intermediate, P = 0.21;

susceptible versus intermediate and resistant, P = 0.17;

resistant versus susceptible and intermediate, P = 0.18;

susceptible versus intermediate and resistant, P = 1.0;

resistant versus susceptible and intermediate, P = 0.77;

susceptible versus resistant, P = 0.18;

susceptible versus resistant, P = 0.18; and

susceptible versus resistant, P = 0.81.

Crude outcomes of patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate, by MIC and category, according to CLSI and EUCAST methods

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . |

| ≤1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.8) |

| 2 | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 9 (14.5) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| 8 | 10 (13.9) | 5 (6.9) | 5 (6.9) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.6) |

| 16 | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) |

| 32 | 6 (26.1) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| >32 | 6 (20.7) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) | 20 (26.7) | 9 (12.0) | 8 (10.7) |

| Category | ||||||

| susceptible | 22 (13.2)a | 7 (4.2)c | 12 (7.2)e | 16 (13.0)g | 4 (3.3)h | 8 (6.5)i |

| intermediate | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | – | – | – |

| resistant | 12 (23.2)b | 5 (9.6)d | 4 (7.7)f | 28 (19.9) | 11 (7.8) | 11 (7.8) |

| . | CLSI . | EUCAST . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . | failure at end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate . | failure at day 21 . | mortality . |

| ≤1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.8) |

| 2 | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 9 (14.5) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| 8 | 10 (13.9) | 5 (6.9) | 5 (6.9) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.6) |

| 16 | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) |

| 32 | 6 (26.1) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| >32 | 6 (20.7) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) | 20 (26.7) | 9 (12.0) | 8 (10.7) |

| Category | ||||||

| susceptible | 22 (13.2)a | 7 (4.2)c | 12 (7.2)e | 16 (13.0)g | 4 (3.3)h | 8 (6.5)i |

| intermediate | 10 (22.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | – | – | – |

| resistant | 12 (23.2)b | 5 (9.6)d | 4 (7.7)f | 28 (19.9) | 11 (7.8) | 11 (7.8) |

Data are presented as number of patients (%).

Comparisons of outcomes (Fisher test):

susceptible versus intermediate and resistant, P = 0.06;

resistant versus susceptible and intermediate, P = 0.21;

susceptible versus intermediate and resistant, P = 0.17;

resistant versus susceptible and intermediate, P = 0.18;

susceptible versus intermediate and resistant, P = 1.0;

resistant versus susceptible and intermediate, P = 0.77;

susceptible versus resistant, P = 0.18;

susceptible versus resistant, P = 0.18; and

susceptible versus resistant, P = 0.81.

We first analysed MIC >8/4 mg/L, which is the present CLSI breakpoint for non-susceptibility, which was also selected by exploratory CART analysis as predictive of failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate. The characteristics of patients with isolates showing MICs ≤8/4 mg/L (n = 167) or >8/4 mg/L (n = 97) are compared in Table 1. Several differences were found: nosocomial infection, major surgery and specific aetiologies (Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens) were more frequent in the MIC >8/4 mg/L group. The failure rate at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate was significantly higher in the MIC >8/4 mg/L group in crude analysis (22.7% versus 13.2%, RR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.00–2.94; P = 0.04) and in adjusted analysis (Table 4). An MIC >8/4 mg/L was not predictive of failure at day 21 or mortality in multivariate analyses (Table 4). Subgroup analyses of patients according to the source of bacteraemia showed similar results (data not shown).

Adjusted association of different breakpoints using CLSI or EUCAST methodology with clinical outcomes in patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate

| Outcome . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI >4/2 mg/L | CLSI >8/4 mg/L | CLSI >16/8 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.47 (0.69–3.12) | 0.31 | 1.96 (0.98–3.90) | 0.05 | 1.81 (0.81–4.03) | 0.14 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.92 (0.62–14.31) | 0.17 | 1.97 (0.65–5.98) | 0.22 | 2.20 (0.64–7.52) | 0.20 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 0.70 (0.25–1.99) | 0.51 | 0.91 (0.33–2.50) | 0.86 | 0.98 (0.29–3.31) | 0.98 |

| EUCAST >8/2 mg/L | EUCAST >16/2 mg/L | EUCAST >32/2 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.68 (0.82–3.41) | 0.14 | 2.10 (1.05–4.21) | 0.03 | 2.32 (1.13–4.77) | 0.02 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.36 (0.69–8.08) | 0.17 | 3.01 (0.93–9.67) | 0.06 | 3.44 (1.08–10.88) | 0.03 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 1.05 (0.38–2.85) | 0.91 | 1.17 (0.43–3.18) | 0.74 | 1.43 (0.50–4.02) | 0.49 |

| Outcome . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI >4/2 mg/L | CLSI >8/4 mg/L | CLSI >16/8 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.47 (0.69–3.12) | 0.31 | 1.96 (0.98–3.90) | 0.05 | 1.81 (0.81–4.03) | 0.14 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.92 (0.62–14.31) | 0.17 | 1.97 (0.65–5.98) | 0.22 | 2.20 (0.64–7.52) | 0.20 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 0.70 (0.25–1.99) | 0.51 | 0.91 (0.33–2.50) | 0.86 | 0.98 (0.29–3.31) | 0.98 |

| EUCAST >8/2 mg/L | EUCAST >16/2 mg/L | EUCAST >32/2 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.68 (0.82–3.41) | 0.14 | 2.10 (1.05–4.21) | 0.03 | 2.32 (1.13–4.77) | 0.02 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.36 (0.69–8.08) | 0.17 | 3.01 (0.93–9.67) | 0.06 | 3.44 (1.08–10.88) | 0.03 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 1.05 (0.38–2.85) | 0.91 | 1.17 (0.43–3.18) | 0.74 | 1.43 (0.50–4.02) | 0.49 |

Adjusted association of different breakpoints using CLSI or EUCAST methodology with clinical outcomes in patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate

| Outcome . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI >4/2 mg/L | CLSI >8/4 mg/L | CLSI >16/8 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.47 (0.69–3.12) | 0.31 | 1.96 (0.98–3.90) | 0.05 | 1.81 (0.81–4.03) | 0.14 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.92 (0.62–14.31) | 0.17 | 1.97 (0.65–5.98) | 0.22 | 2.20 (0.64–7.52) | 0.20 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 0.70 (0.25–1.99) | 0.51 | 0.91 (0.33–2.50) | 0.86 | 0.98 (0.29–3.31) | 0.98 |

| EUCAST >8/2 mg/L | EUCAST >16/2 mg/L | EUCAST >32/2 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.68 (0.82–3.41) | 0.14 | 2.10 (1.05–4.21) | 0.03 | 2.32 (1.13–4.77) | 0.02 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.36 (0.69–8.08) | 0.17 | 3.01 (0.93–9.67) | 0.06 | 3.44 (1.08–10.88) | 0.03 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 1.05 (0.38–2.85) | 0.91 | 1.17 (0.43–3.18) | 0.74 | 1.43 (0.50–4.02) | 0.49 |

| Outcome . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI >4/2 mg/L | CLSI >8/4 mg/L | CLSI >16/8 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.47 (0.69–3.12) | 0.31 | 1.96 (0.98–3.90) | 0.05 | 1.81 (0.81–4.03) | 0.14 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.92 (0.62–14.31) | 0.17 | 1.97 (0.65–5.98) | 0.22 | 2.20 (0.64–7.52) | 0.20 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 0.70 (0.25–1.99) | 0.51 | 0.91 (0.33–2.50) | 0.86 | 0.98 (0.29–3.31) | 0.98 |

| EUCAST >8/2 mg/L | EUCAST >16/2 mg/L | EUCAST >32/2 mg/L | ||||

| Failure at the end of amoxicillin/clavulanate | 1.68 (0.82–3.41) | 0.14 | 2.10 (1.05–4.21) | 0.03 | 2.32 (1.13–4.77) | 0.02 |

| Failure at day 21 | 2.36 (0.69–8.08) | 0.17 | 3.01 (0.93–9.67) | 0.06 | 3.44 (1.08–10.88) | 0.03 |

| Mortality at day 30 | 1.05 (0.38–2.85) | 0.91 | 1.17 (0.43–3.18) | 0.74 | 1.43 (0.50–4.02) | 0.49 |

Multivariate analysis was also performed using MIC >16/8 mg/L as the breakpoint, which is the CLSI breakpoint for resistance; no association with any studied outcome could be identified (Table 4).

Exploratory CART analysis selected >4/2 mg/L as a predictor of failure at day 21; the rates of failure were 2.1% (2 of 95) for MIC ≤4/2 mg/L and 7.7% (13 of 169) for >4/2 mg/L (unadjusted RR = 3.64; 95% CI: 0.84–15.78; P = 0.06). No significant association could be demonstrated by multivariate analysis (Table 4). In subgroup analyses, there was a trend towards increased risk of failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate in patients whose source was different from the urinary or biliary tract (adjusted OR = 2.28; 95% CI: 0.92–5.68; P = 0.07). No other subgroup analyses provided significant results. CART analysis could not find any MIC value that predicted mortality.

Association of EUCAST-derived MICs and outcomes

The associations between MICs obtained with EUCAST methodology and outcomes are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. Crude comparisons of outcomes according to recommended breakpoints are also shown in Table 3; no statistically significant differences between susceptible and non-susceptible isolates were found. Considered as a continuous variable, base 2 log-converted MIC obtained with EUCAST methodology was associated with failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate (OR per increase in MIC value = 1.22; 95% CI: 1.03–1.43; P = 0.01) and at day 21 (OR = 1.42; 95% CI: 1.06–1.92; P = 0.01), but not with mortality (OR = 1.06; 95% CI: 0.85–1.33; P = 0.57).

No significant association could be found with MIC >8/2 mg/L (present breakpoint recommended by EUCAST for resistance) and any of the outcomes investigated (Table 4).

Exploratory CART analysis selected >32/2 mg/L as predicting failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate. The features of patients with isolates showing MIC ≤32/2 mg/L and >32/2 mg/L are shown in Table 1. Higher rates of failure were observed in the high MIC group in crude analysis at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate (12.7% versus 26.7%; RR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.23–3.56; P = 0.006) and at day 21 (3.2% versus 12.0%, RR = 3.78; 95% CI: 1.39–10.25; P = 0.01). The differences were not significant for mortality (5.8% versus 10.7%, RR = 1.83; 95% CI: 0.76–4.37; P = 0.17). By multivariate analysis (Table 4), isolates with MICs >32/2 mg/L remained independently associated with a higher risk of failure at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at day 21 (Table 4). However, subgroup analysis showed that isolates with MICs >32/2 mg/L were associated with failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate in patients with a urinary or biliary tract source (adjusted OR = 2.34; 95% CI: 1.00–5.44; P = 0.04), but the association was not significant for other sources (adjusted OR = 1.83; 95% CI: 0.44–7.61; P = 0.4). MIC >32/2 mg/L also showed independent association with failure at day 21, but not with mortality (Table 4).

We also investigated lower breakpoints. Importantly, MIC >16/2 mg/L was also associated with crude higher risk of failure at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate (12.4% versus 23.3%; RR = 1.88; 95% CI: 1.09–3.21; P = 0.02) and at day 21 (3.1% versus 9.7%; RR = 3.12; 95% CI: 1.10–8.84; P = 0.02), but not with mortality (6.2% versus 8.7%; RR = 1.40; 95% CI: 0.59–3.34; P = 0.4). The associations with failure at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at day 21 were was also significant in multivariate analysis (Table 4). Stratified analysis according to source (urinary tract or others) did not change the results.

Discussion

There are few clinical data available to support the establishment of susceptibility breakpoints for most antimicrobial agents due to the difficulties of performing studies that address this issue. It would be impossible, as well as unethical, to randomize patients for empirical therapy by MIC, and post-hoc analyses of patients included in randomized trials are usually limited by the fact that the most severely affected patients or those with resistant isolates are typically underrepresented. Well-designed observational studies could be useful for this purpose, although designing such studies also presents challenges. Several aspects must be taken into account. First, only patients treated in monotherapy with the antibiotic of interest should be included; second, all patients should receive the antibiotic early enough and for a minimum period to allow the activity to be measured; third, the reasons for changing to another antibiotic should be assessed; fourth, the outcomes should be appropriately chosen to measure the effect; and fifth, the effect of confounders should be controlled for.

The Bacteraemia-MIC project was specifically designed to investigate the impact of MICs of β-lactams and fluoroquinolones on the outcome of patients with bacteraemia due to Enter obacteriaceae. We focused, in this analysis, on amoxicillin/clavulanate because it is commonly used in many countries, and because the methods recommended by CLSI and EUCAST for susceptibility assays and clinical breakpoint values differ.

The results obtained from this study showed significant discrepancies and there was low overall agreement for susceptibility data obtained using CLSI and EUCAST methodologies; this resulted in a higher percentage of resistant isolates for E. coli and Klebsiella spp. and a lower one for Proteus spp. when EUCAST methodology was used. Two previous studies including only E. coli isolates showed higher resistance rates with EUCAST.6,7 These data have very important implications for surveillance of resistance and antibiotic use; surveillance systems should specify the methodology used and take into account that whenever EUCAST criteria are applied, higher rates of resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate should be expected for E. coli and Klebsiella spp. In addition, empirical and targeted therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate would be less frequently recommended if EUCAST is used.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to include a detailed prospective clinical evaluation of patients with bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae and treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate with the specific objective of investigating the impact of MIC on outcome. Several features of the cohort, even though it was typical of infection studies, should be taken into account when interpreting the data: first, a high proportion of the cases were due to E. coli and representation of other Enterobacteriaceae was therefore limited; second, the most frequent source of bacteraemia was the urinary tract, which has better expected outcomes than other sources; and third, severe sepsis or septic shock were not frequent. This probably explains the low rate of clinical failures and mortality found even in the resistant subgroups. MIC was not therefore expected to have a clear impact on mortality, and clinical failure was also assessed as an outcome. Because clinical failure is prone to subjective interpretations, to try and limit investigator-derived information bias, objective data were collected for use by a blind investigator to check the outcomes determined by the local investigators. In addition, because antibiotic therapy is frequently changed during the course of infection, we assessed clinical failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at day 21. We expected failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate to be most directly associated with amoxicillin/clavulanate activity, because a change to another drug is expected to cure eventually the patients who survive. The definition for this outcome considered any change of antibiotic where the patient was not clearly improving as a failure, to be as sensitive as possible in detecting what was considered as failure in clinical practice.

Overall, our results suggest that EUCAST-derived MICs were more predictive of outcomes. Interestingly, EUCAST-derived MIC values were predictive of outcome when considered as a continuous variable, while CLSI-derived MIC values were not. The failure rates for patients with isolates with discrepant CLSI and EUCAST susceptibility results lay between those that were susceptible and resistant according to the two methodologies, although the differences were not statistically significant, which may be due to the lack of statistical power. Because all failures among discrepant isolates occurred with borderline MICs (8/4–16/8 mg/L) using CLSI criteria, this would suggest using caution when interpreting CLSI results with borderline MICs until more data become available.

The CART analysis for CLSI-derived MICs suggested the currently recommended breakpoint (non-susceptible, >8/4 mg/L) as predictive of failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate. When confounders were taken into account, however, the estimate was less precise as the 95% CI was wider and the association was borderline significant. In any case, we think that these results tend to reinforce the fact that isolates with MICs >8/4 mg/L should not be considered as susceptible when using CLSI methods. We were unable to find any crude or adjusted association between this breakpoint and failure at day 21 or mortality. Interestingly, isolates from patients with sources other than the urinary or biliary tract and with MICs >4/2 mg/L showed an independent trend towards higher risk of failure at day 21. Despite the limitation inherent to low number of cases with other sources, caution should be exercised with patients with these infections and with borderline MICs using CLSI criteria.

On the other hand, the breakpoint for failure identified by CART analysis for EUCAST-derived MICs (>32/2 mg/L) is two dilutions higher than the actual breakpoint for resistance (>8/2 mg/L), but is the recommended breakpoint for uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Importantly, the results of multivariate analysis supported >32/2 mg/L as an independent predictor of failure at the end of treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate in patients with urinary or biliary tract infections; therefore, the latter types of infection might be treated with intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanate, even with MICs up to 32/2 mg/L. However, as MIC >16/2 mg/L was also independently associated with failure, this latter breakpoint is probably more reasonable and safer for all types of infection. Importantly, the present breakpoint recommended by EUCAST (>8/2 mg/L) did not show any predictive effect on any of the outcomes measured. A previous study with fewer patients showed a higher failure rate for patients with isolates with MICs >8/2 mg/L using EUCAST; in that study, however, only episodes caused by E. coli were included, an automated system and gradient test (Etest®) were used to determine the MIC, and the definitions of outcome were different.7 Our results would suggest that the EUCAST breakpoint for invasive infections might need to be reconsidered.

For interpretation of the data, it should be kept in mind that most patients were treated with 1.2 g every 8 h. Because some patients were administered 2.2 g every 8 h, we explored dosing as a potential confounder, but we found no crude association or trend with any of the outcomes. Nevertheless, we performed additional multivariate analysis introducing this variable, but it showed no statistically significant influence on any outcomes or modification effect (interaction) with MIC values (data not shown).

This study has some limitations that should be taken into account. Despite the high number of patients included, the statistical power was limited for some subgroup analyses. The results would apply mainly to the type of patients included here and to the most frequent sources of bacteraemia and severity at presentation as shown by the fact that the rate of failure in our cohort was low even in patients with resistant isolates. We included patients in whom amoxicillin/clavulanate was changed to another antibiotic for various reasons, which gave our results greater external validity, but jeopardized their internal validity. Finally, we used MIC values as a continuous variable for some analysis, which is subject to debate; however, it should be noted that it is not usually possible to analyse this variable as a discrete categorical variable in clinical studies, as was the case in this one, because of the low number of cases for most of the MIC values.

In conclusion, CLSI and EUCAST methodologies showed low agreement when determining the MICs of amoxicillin/clavulanate and interpreting susceptibility; EUCAST MICs were associated with outcomes when considered as a continuous variable while CLSI ones were not. The present CLSI breakpoint (>8/4 mg/L) was only borderline predictive of failure at the end of therapy with this drug; an MIC >16/2 mg/L using EUCAST methodology was independently associated with failure at the end of therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate and at day 21. However, because of the high proportion of cases with a urinary tract source, more studies are needed in patients with bloodstream infections from other sources.

Acknowledgements

Other members of the REIPI/GEIH-SEIMC BACTEREMIA-MIC Group

Marina de Cueto (Unidad Clínica Intercentros de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Microbiología y Medicina Preventiva, Hospitales Universitarios Virgen Macarena y Virgen del Rocío, Seville, Spain), Ana María Planes-Reig (Departamento de Microbiología, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain), Fe Tubau-Quintano (Servicio de Microbiología, Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge-IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain), Carmen Peña (Servicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge-IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain), Carlos Ruíz de Alegría (Servicio de Microbiología, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain), M. Isabel Morosini, Adriana Shan (Servicio de Microbiología, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal and Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS), Madrid, Spain), José Miguel Cisneros (Unidad Clínica Intercentros de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Microbiología y Medicina Preventiva, Hospitales Universitarios Virgen Macarena y Virgen del Rocío, Seville, Spain), J. Enrique Corzo (Unidad Clínica de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología, Hospital Universitario de Valme, Seville, Spain), Núria Prim, María Elvira Galán (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain), Lara García-Álvarez (Departamento de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital San Pedro–CIBIR, Logroño, Spain), Irene Gracia-Ahufinger, Julia Guzmán-Puche, Julián Torre-Cisneros (Unidad de Gestión Clínica de Microbiología y Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba, Spain).

Funding

The study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain (Fondo de investigación en salud; PI10/02021) co-financed by European Development Regional Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ ERDF, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD12/0015).

Transparency declarations

B. A. has been a scientific advisor for AstraZeneca, Merck, Pfizer, Novartis, Astellas and Gilead, and has been a speaker for AstraZeneca, Merck, Pfizer, Astellas, Gilead and Novartis. R. C. is part of the Steering Committee of EUCAST. J. R.-B. has been a scientific advisor for AstraZeneca, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Achaogen, InfectoPharm and Basilea, and has been a speaker for AstraZeneca, Astellas, Merck, Pfizer and Novartis. All other authors: none to declare.

Supplementary data

Table S1 is available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

Author notes

These authors contributed equally to authorship.

Other members are listed in the Acknowledgements section.