-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Wirawan Jeong, Peter Haywood, Naranie Shanmuganathan, Julian Lindsay, Karen Urbancic, Michelle R. Ananda-Rajah, Sharon C. A. Chen, Ashish Bajel, David Ritchie, Andrew Grigg, John F. Seymour, Anton Y. Peleg, David C. M. Kong, Monica A. Slavin, Safety, clinical effectiveness and trough plasma concentrations of intravenous posaconazole in patients with haematological malignancies and/or undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: off-trial experience, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 71, Issue 12, 1 December 2016, Pages 3540–3547, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw322

Close - Share Icon Share

This study describes the safety, clinical effectiveness and trough plasma concentration (Cmin) of intravenous (iv) posaconazole, provided as part of Merck Sharp and Dohme Australia's Named Patient Programme (NPP) in non-clinical trial settings.

A multicentre, retrospective study on the NPP use of iv posaconazole between July 2014 and March 2015 across seven Australian hospitals.

Seventy courses of iv posaconazole were prescribed and evaluated in 61 patients receiving treatment for haematological malignancy. Sixty-one courses were prescribed for prophylaxis against invasive fungal disease (IFD), the majority of which (59) were initiated in patients with gastrointestinal disturbances and/or intolerance to previous antifungals. The median (IQR) duration for prophylaxis was 10 (6–15) days. No breakthrough IFD was observed during or at cessation of iv posaconazole. Nine courses of iv posaconazole were prescribed for treatment of IFD with a median (IQR) duration of 19 (7–30) days. Improvement in signs and symptoms of IFD was observed in five cases at cessation of, and six cases at 30 days post-iv posaconazole. Cmin was measured in 39 courses of iv posaconazole, with the initial level taken [median (IQR)] 4 (3–7) days after commencing iv posaconazole. The median (IQR) of initial Cmin was 1.16 (0.69–2.06) mg/L. No severe adverse events specifically attributed to iv posaconazole were documented, although six courses were curtailed due to potential toxicity.

This non-clinical trial experience suggests that iv posaconazole appeared to be safe and clinically effective for prophylaxis or treatment of IFD in patients receiving treatment for haematological malignancies.

Introduction

Posaconazole is a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal1 with good in vitro activity against fungal pathogens including Candida, Aspergillus, the mucormycetes and endemic fungi.2–4 Its efficacy as antifungal prophylaxis when administered orally is well established.5–7 In spite of the recent availability of posaconazole tablets, current international consensus guidelines still recommend posaconazole oral suspension as antifungal prophylaxis in haematology patients at high risk of developing invasive fungal disease (IFD).8–10

Despite displaying linear pharmacokinetics and non-CYP450-mediated metabolism,11 the clinical utility of posaconazole oral suspension is limited by its erratic bioavailability and unpredictable trough plasma concentration (Cmin).12 These properties limit the use of posaconazole oral suspension as a first-line treatment against IFD caused by posaconazole-susceptible pathogens, including mucormycosis.13 Whilst administering posaconazole oral suspension with high-fat meals to optimize its bioavailability is recommended,12,14 this can be challenging in patients with poor oral intake or impaired gastrointestinal (GI) function,15 both of which are common in patients receiving intensive chemotherapy for haematological malignancies or following allogeneic HSCT. Although posaconazole in tablet form has been demonstrated to achieve therapeutic Cmin regardless of food intake,16 it was not available in Australia at the time of this study.

Intravenous (iv) posaconazole could potentially be an alternative in patients with poor GI function and/or intolerant of posaconazole oral suspension. Whilst the safety and efficacy of iv posaconazole is well documented from clinical trials,17,18 experience outside of this setting remains scant. Prior to its commercial registration in Australia in January 2015, iv posaconazole was available from Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) via the Named Patient Programme (NPP) (see below). Accordingly, this study describes the safety and clinical effectiveness of iv posaconazole provided via this programme.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

This is a multicentre, retrospective observational study involving seven Australian tertiary teaching hospitals, which provide treatment for patients with haematological malignancies and perform HSCT. All patients receiving iv posaconazole under the NPP in the participating institutions were included in the study. MSD Australia was not involved in the study design, data analysis or the formulation of this manuscript.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the human research ethics committees of Royal Melbourne Hospital (approval number: QA2015058), Royal Adelaide Hospital (HREC/15/RAH/104), Royal North Shore Hospital (LNR/15/HAWKE/36), Austin Hospital (LNR/15/Austin/192), Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (15/54R), The Alfred (281/15), Westmead Hospital (LNR/15/WMEAD/188) and Monash University (CF15/2277-2015000916). Written informed consent was waived by all ethics committees.

MSD Australia's NPP

The NPP provided free access to iv posaconazole from 1 July 2014 to 12 March 2015 prior to its commercial availability. Under the NPP, patients (≥18 years old) suspected of having impaired GI absorption of posaconazole oral suspension due to nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea and/or mucositis, or those who were unable to tolerate alternative antifungals, were eligible to access iv posaconazole for the following indications: (i) prophylaxis against IFD whilst patients were likely to be at risk of poor absorption and/or other available treatments were not suitable due to intolerance, potential for drug–drug interactions, pharmacokinetic failure or contraindication; (ii) prophylaxis in AML during induction, remission or consolidation chemotherapy; (iii) prophylaxis post-allogeneic HSCT; (iv) secondary prophylaxis for patients undergoing HSCT; and (v) treatment of IFD refractory and/or when patients were intolerant to other available antifungals.

The recommended dose for iv posaconazole was 300 mg twice daily on the first day followed by 300 mg once daily thereafter for up to 14 and 30 days for prophylaxis and treatment of IFD, respectively. Posaconazole was reconstituted in 150 mL of 5% dextrose or 0.9% sodium chloride solution and administered through an inline filter over 90 min via a central venous line.19

Clinical data collection

Investigators from the participating sites extracted the data using a standardized case report form developed for the study. Patient data were obtained from patient medical records, laboratory, pathology and radiology reports. These included demographic characteristics, primary underlying conditions, Charlson comorbidities up to 30 days prior to the initiation of iv posaconazole, neutropenia status at the initiation of iv posaconazole, episodes of graft versus host disease (GVHD), cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation and renal replacement therapy whilst receiving iv posaconazole, details of iv posaconazole therapy (indication, dosing regimen, duration of therapy, Cmin, reason for cessation and patient outcomes), details of other antifungal agents administered in the previous 7 days, during and post-iv posaconazole (type of antifungal, dose form and indication), liver and renal function tests at commencement and cessation of iv posaconazole, radiological and microbiological results. All data were de-identified, collated and pooled for analysis.

Neutropenia was defined as absolute neutrophil count <500 cells/mm3. CMV reactivation was defined as detection of viral nucleic acid in plasma or whole blood sample.20 Charlson comorbidity score was determined using the adapted weighted Charlson Comorbidities Index,21 whereby haematological malignancies were excluded given that our patients were receiving treatment for these conditions. Cases of IFD were categorized into proven, probable or possible according to the revised European Organisation for Treatment of Cancer/Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) criteria.22 The cases of IFD were adjudicated by infectious diseases physicians: M. A. S., S. C. A. C. and M. A.-R.

Outcomes assessment

The outcomes of iv posaconazole therapy were evaluated only in patients receiving at least one course of iv posaconazole, defined as administration of iv posaconazole for at least 3 days consecutively before ceasing or switching to another antifungal. Effective prophylaxis was defined as the absence of breakthrough IFD during and at cessation of iv posaconazole. When used to treat IFD, the outcome of iv posaconazole treatment was assessed at cessation and 30 days post-cessation of iv posaconazole, and was defined as complete response, partial response, stable response, progression of disease or death, using published criteria.23

The safety and tolerability of iv posaconazole were based on observations documented (as part of routine patient care) in patients’ medical records by the treating medical team (i.e. doctors, nurses and pharmacists). All patients received standard care including daily electrolytes, complete blood count, liver and renal function tests. The effects of iv posaconazole on the liver and renal function were assessed by comparing ALT, total bilirubin and calculated creatinine clearance values at the commencement and cessation of iv posaconazole.

Trough plasma concentrations

Intravenous posaconazole Cmin and monitoring frequency were recorded. Posaconazole Cmin was determined using validated analytical assays performed by National Association of Testing Authorities Australia accredited laboratories servicing the participating hospitals. Intra-patient variability in iv posaconazole Cmin was evaluated in patients who had at least two measurements whilst receiving iv posaconazole.24Cmin of at least 0.7 and 1 mg/L were considered therapeutic for the prophylaxis and treatment of IFD, respectively.25,26

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics and outcomes. The Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney test was used to evaluate the difference between two independent variables. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess the difference between liver function tests and calculated creatinine clearance values at baseline and post-treatment. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using Stata 14.0 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

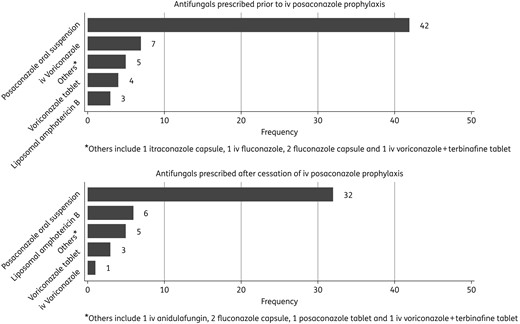

One hundred and six patients received iv posaconazole under the NPP, of which 72 were from institutions participating in this study. Sixty-one patients were included in the final analysis; two were excluded due to missing records, whilst nine did not receive iv posaconazole for at least 3 days consecutively due to improvement in GI function (n = 4), or death (n = 2), or abnormal baseline liver function (n = 1) or treating clinicians’ preference for other antifungals (n = 2). Seventy courses of iv posaconazole were administered to the 61 patients (Table 1). Fifty-two patients received 61 courses of iv posaconazole for prophylaxis against IFD (1 course in 46, 2 courses in 5, and 5 courses in 1). The remaining nine patients were each prescribed a single course of iv posaconazole for the treatment of IFD. Posaconazole oral suspension was the most commonly prescribed antifungal before, and after, iv posaconazole (Figure 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients receiving intravenous posaconazole

| Characteristics . | Prophylaxis n (%), unless otherwise stated . | Treatment n (%), unless otherwise stated . |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics of patients, n = 61 (total) | ||

| no. of patients | 52 (85) | 9 (15) |

| age; median (IQR), years | 52 (34–60) | 57 (55–63) |

| no. of male gender | 29 (56) | 8 (89) |

| Clinical characteristics of patients per iv posaconazole course, n = 70 (total) | ||

| no. of courses of iv posaconazole | 61 (87) | 9 (13) |

| Underlying conditions being treated at the initiation of iv posaconazole | ||

| AML | 12 (20) | 2 (22) |

| ALL | 1 (2) | 1 (11) |

| allo-HSCT | 45 (74) | 2 (22) |

| related | 14 (31) | 2 (100) |

| unrelated | 30 (67) | 0 |

| cord blood | 1 (2) | 0 |

| other | 3 (5)a | 4 (44)b |

| Neutropenic at the initiation of iv posaconazole | 38 (62) | 2 (22) |

| Charlson comorbidity scorec | ||

| 1–2 | 9 (15) | 4 (44) |

| 3 or higher | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Renal replacement therapy during iv posaconazole | 4 (7) | 1 (11) |

| CMV reactivation during iv posaconazole | 9 (15) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD during iv posaconazole | 15 (25) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD grade | ||

| I–II | 3 (20) | 0 |

| III–IV | 6 (40) | 2 (100) |

| not stated | 6 (40) | 0 |

| Characteristics . | Prophylaxis n (%), unless otherwise stated . | Treatment n (%), unless otherwise stated . |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics of patients, n = 61 (total) | ||

| no. of patients | 52 (85) | 9 (15) |

| age; median (IQR), years | 52 (34–60) | 57 (55–63) |

| no. of male gender | 29 (56) | 8 (89) |

| Clinical characteristics of patients per iv posaconazole course, n = 70 (total) | ||

| no. of courses of iv posaconazole | 61 (87) | 9 (13) |

| Underlying conditions being treated at the initiation of iv posaconazole | ||

| AML | 12 (20) | 2 (22) |

| ALL | 1 (2) | 1 (11) |

| allo-HSCT | 45 (74) | 2 (22) |

| related | 14 (31) | 2 (100) |

| unrelated | 30 (67) | 0 |

| cord blood | 1 (2) | 0 |

| other | 3 (5)a | 4 (44)b |

| Neutropenic at the initiation of iv posaconazole | 38 (62) | 2 (22) |

| Charlson comorbidity scorec | ||

| 1–2 | 9 (15) | 4 (44) |

| 3 or higher | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Renal replacement therapy during iv posaconazole | 4 (7) | 1 (11) |

| CMV reactivation during iv posaconazole | 9 (15) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD during iv posaconazole | 15 (25) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD grade | ||

| I–II | 3 (20) | 0 |

| III–IV | 6 (40) | 2 (100) |

| not stated | 6 (40) | 0 |

aIncluding one blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell sarcoma, one granulocytic myeloid sarcoma and one multiple myeloma.

bIncluding one auto-HSCT, one minimal change glomerulonephritis and diabetes mellitus, one inactive lymphoma (remission) and one diabetes mellitus.

cFifteen patients had co-morbidities other than haematological malignancies and thus had their Charlson score calculated.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients receiving intravenous posaconazole

| Characteristics . | Prophylaxis n (%), unless otherwise stated . | Treatment n (%), unless otherwise stated . |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics of patients, n = 61 (total) | ||

| no. of patients | 52 (85) | 9 (15) |

| age; median (IQR), years | 52 (34–60) | 57 (55–63) |

| no. of male gender | 29 (56) | 8 (89) |

| Clinical characteristics of patients per iv posaconazole course, n = 70 (total) | ||

| no. of courses of iv posaconazole | 61 (87) | 9 (13) |

| Underlying conditions being treated at the initiation of iv posaconazole | ||

| AML | 12 (20) | 2 (22) |

| ALL | 1 (2) | 1 (11) |

| allo-HSCT | 45 (74) | 2 (22) |

| related | 14 (31) | 2 (100) |

| unrelated | 30 (67) | 0 |

| cord blood | 1 (2) | 0 |

| other | 3 (5)a | 4 (44)b |

| Neutropenic at the initiation of iv posaconazole | 38 (62) | 2 (22) |

| Charlson comorbidity scorec | ||

| 1–2 | 9 (15) | 4 (44) |

| 3 or higher | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Renal replacement therapy during iv posaconazole | 4 (7) | 1 (11) |

| CMV reactivation during iv posaconazole | 9 (15) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD during iv posaconazole | 15 (25) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD grade | ||

| I–II | 3 (20) | 0 |

| III–IV | 6 (40) | 2 (100) |

| not stated | 6 (40) | 0 |

| Characteristics . | Prophylaxis n (%), unless otherwise stated . | Treatment n (%), unless otherwise stated . |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics of patients, n = 61 (total) | ||

| no. of patients | 52 (85) | 9 (15) |

| age; median (IQR), years | 52 (34–60) | 57 (55–63) |

| no. of male gender | 29 (56) | 8 (89) |

| Clinical characteristics of patients per iv posaconazole course, n = 70 (total) | ||

| no. of courses of iv posaconazole | 61 (87) | 9 (13) |

| Underlying conditions being treated at the initiation of iv posaconazole | ||

| AML | 12 (20) | 2 (22) |

| ALL | 1 (2) | 1 (11) |

| allo-HSCT | 45 (74) | 2 (22) |

| related | 14 (31) | 2 (100) |

| unrelated | 30 (67) | 0 |

| cord blood | 1 (2) | 0 |

| other | 3 (5)a | 4 (44)b |

| Neutropenic at the initiation of iv posaconazole | 38 (62) | 2 (22) |

| Charlson comorbidity scorec | ||

| 1–2 | 9 (15) | 4 (44) |

| 3 or higher | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Renal replacement therapy during iv posaconazole | 4 (7) | 1 (11) |

| CMV reactivation during iv posaconazole | 9 (15) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD during iv posaconazole | 15 (25) | 2 (22) |

| GVHD grade | ||

| I–II | 3 (20) | 0 |

| III–IV | 6 (40) | 2 (100) |

| not stated | 6 (40) | 0 |

aIncluding one blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell sarcoma, one granulocytic myeloid sarcoma and one multiple myeloma.

bIncluding one auto-HSCT, one minimal change glomerulonephritis and diabetes mellitus, one inactive lymphoma (remission) and one diabetes mellitus.

cFifteen patients had co-morbidities other than haematological malignancies and thus had their Charlson score calculated.

Intravenous posaconazole prophylaxis

Details of iv posaconazole therapy in the setting of prophylaxis against IFD

| Variables . | Prophylaxis n (%) [n = 61] . |

|---|---|

| Indications for iv posaconazole prophylaxis | |

| prophylaxis of IFD during poor GI function and/or intolerant to other antifungal | 59 (97) |

| GI absorption concerns—GVHD-associated | 10 (17) |

| GI absorption concerns—non-GVHD | 42 (71) |

| Intolerant to other antifungal | 7 (12) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in AML during chemotherapy | 1 (2) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in post-allo SCT | 1 (2) |

| Use of loading dose | 33 (54) |

| Reason for ceasing iv posaconazole | |

| improvement in GI function | 44 (72) |

| potential toxicity | 5 (8)a |

| death (non-IFD related) | 8 (13) |

| other | 4 (7)b |

| Variables . | Prophylaxis n (%) [n = 61] . |

|---|---|

| Indications for iv posaconazole prophylaxis | |

| prophylaxis of IFD during poor GI function and/or intolerant to other antifungal | 59 (97) |

| GI absorption concerns—GVHD-associated | 10 (17) |

| GI absorption concerns—non-GVHD | 42 (71) |

| Intolerant to other antifungal | 7 (12) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in AML during chemotherapy | 1 (2) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in post-allo SCT | 1 (2) |

| Use of loading dose | 33 (54) |

| Reason for ceasing iv posaconazole | |

| improvement in GI function | 44 (72) |

| potential toxicity | 5 (8)a |

| death (non-IFD related) | 8 (13) |

| other | 4 (7)b |

aIncluding four abnormal liver function tests and one thrombocytopenia.

bIncluding switching to Scedosporium spp. prophylaxis (n = 1), empirical treatment (n = 2) and palliative care (n = 1).

Details of iv posaconazole therapy in the setting of prophylaxis against IFD

| Variables . | Prophylaxis n (%) [n = 61] . |

|---|---|

| Indications for iv posaconazole prophylaxis | |

| prophylaxis of IFD during poor GI function and/or intolerant to other antifungal | 59 (97) |

| GI absorption concerns—GVHD-associated | 10 (17) |

| GI absorption concerns—non-GVHD | 42 (71) |

| Intolerant to other antifungal | 7 (12) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in AML during chemotherapy | 1 (2) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in post-allo SCT | 1 (2) |

| Use of loading dose | 33 (54) |

| Reason for ceasing iv posaconazole | |

| improvement in GI function | 44 (72) |

| potential toxicity | 5 (8)a |

| death (non-IFD related) | 8 (13) |

| other | 4 (7)b |

| Variables . | Prophylaxis n (%) [n = 61] . |

|---|---|

| Indications for iv posaconazole prophylaxis | |

| prophylaxis of IFD during poor GI function and/or intolerant to other antifungal | 59 (97) |

| GI absorption concerns—GVHD-associated | 10 (17) |

| GI absorption concerns—non-GVHD | 42 (71) |

| Intolerant to other antifungal | 7 (12) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in AML during chemotherapy | 1 (2) |

| prophylaxis of IFD in post-allo SCT | 1 (2) |

| Use of loading dose | 33 (54) |

| Reason for ceasing iv posaconazole | |

| improvement in GI function | 44 (72) |

| potential toxicity | 5 (8)a |

| death (non-IFD related) | 8 (13) |

| other | 4 (7)b |

aIncluding four abnormal liver function tests and one thrombocytopenia.

bIncluding switching to Scedosporium spp. prophylaxis (n = 1), empirical treatment (n = 2) and palliative care (n = 1).

Antifungal prescribed prior to and after cessation of iv posaconazole prophylaxis.

Intravenous posaconazole for treatment of IFD

Nine courses of iv posaconazole were administered for the treatment of IFD (Table 3). The median (IQR) treatment duration was 19 (7–30) days. Discontinuation of iv posaconazole for reasons other than completion of iv therapy was observed in three cases due to unfavourable susceptibility profile of the fungal isolate, concern about abnormal liver function tests (LFT) and perceived lack of efficacy (patient nos. 1, 5 and 6, respectively). For these three cases, iv posaconazole was discontinued 7, 22 and 19 days after initiation of treatment, respectively. After cessation of iv posaconazole, all patients continued to receive antifungals including liposomal amphotericin B, posaconazole oral suspension, posaconazole tablet or iv voriconazole. Improvement in signs and symptoms of IFD were observed in five (one complete response, four partial responses) and six (one complete response, five partial responses) cases at cessation of, and 30 days post-iv posaconazole, respectively. The patient with perceived lack of efficacy (patient no. 6) had probable aspergillosis with suspected progression of IFD, Klebsiella pneumonia and multi-organ failure including respiratory failure. For this patient, iv posaconazole was administered for 7 days before being replaced by liposomal amphotericin B. The patient died 2 days later and Rhizopus was isolated from the tracheal aspirate.

Details of proven, probable and possible IFD treated with iv posaconazole (POS) (n = 9 patients)

| Classification of IFD . | Patient no. . | Organisms . | POS MIC (mg/L) or susceptibility . | Initial POS Cmin (mg/L) . | Patient response . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at cessation of iv POS . | 30 days post-iv POS . | |||||

| Proven | 1 | Fusarium solani complex | >8 | 1.02 | partial | partial |

| 2 | Rhizopus oryzae | NA | 2.09 | stable | partial | |

| 3 | unspecified mucormycete | NA | 2.31 | complete | complete | |

| 4 | unspecified coelomycete | resistant | 1.16 | stable | partial | |

| Probable | 5 | Aspergillus fumigatus | NA | NA | partial | death (non-IFD) |

| 6 | Aspergillus niger | 0.50 | 0.60 | progression | death | |

| 7 | unspecified Aspergillus sp. | NA | 0.691 | stable | stable | |

| 8 | Lichtheimia corymbifera | 0.12 | 1.81 | partial | partial | |

| Possible | 9 | NA | NA | NA | partial | partial |

| Classification of IFD . | Patient no. . | Organisms . | POS MIC (mg/L) or susceptibility . | Initial POS Cmin (mg/L) . | Patient response . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at cessation of iv POS . | 30 days post-iv POS . | |||||

| Proven | 1 | Fusarium solani complex | >8 | 1.02 | partial | partial |

| 2 | Rhizopus oryzae | NA | 2.09 | stable | partial | |

| 3 | unspecified mucormycete | NA | 2.31 | complete | complete | |

| 4 | unspecified coelomycete | resistant | 1.16 | stable | partial | |

| Probable | 5 | Aspergillus fumigatus | NA | NA | partial | death (non-IFD) |

| 6 | Aspergillus niger | 0.50 | 0.60 | progression | death | |

| 7 | unspecified Aspergillus sp. | NA | 0.691 | stable | stable | |

| 8 | Lichtheimia corymbifera | 0.12 | 1.81 | partial | partial | |

| Possible | 9 | NA | NA | NA | partial | partial |

NA, not available.

Details of proven, probable and possible IFD treated with iv posaconazole (POS) (n = 9 patients)

| Classification of IFD . | Patient no. . | Organisms . | POS MIC (mg/L) or susceptibility . | Initial POS Cmin (mg/L) . | Patient response . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at cessation of iv POS . | 30 days post-iv POS . | |||||

| Proven | 1 | Fusarium solani complex | >8 | 1.02 | partial | partial |

| 2 | Rhizopus oryzae | NA | 2.09 | stable | partial | |

| 3 | unspecified mucormycete | NA | 2.31 | complete | complete | |

| 4 | unspecified coelomycete | resistant | 1.16 | stable | partial | |

| Probable | 5 | Aspergillus fumigatus | NA | NA | partial | death (non-IFD) |

| 6 | Aspergillus niger | 0.50 | 0.60 | progression | death | |

| 7 | unspecified Aspergillus sp. | NA | 0.691 | stable | stable | |

| 8 | Lichtheimia corymbifera | 0.12 | 1.81 | partial | partial | |

| Possible | 9 | NA | NA | NA | partial | partial |

| Classification of IFD . | Patient no. . | Organisms . | POS MIC (mg/L) or susceptibility . | Initial POS Cmin (mg/L) . | Patient response . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at cessation of iv POS . | 30 days post-iv POS . | |||||

| Proven | 1 | Fusarium solani complex | >8 | 1.02 | partial | partial |

| 2 | Rhizopus oryzae | NA | 2.09 | stable | partial | |

| 3 | unspecified mucormycete | NA | 2.31 | complete | complete | |

| 4 | unspecified coelomycete | resistant | 1.16 | stable | partial | |

| Probable | 5 | Aspergillus fumigatus | NA | NA | partial | death (non-IFD) |

| 6 | Aspergillus niger | 0.50 | 0.60 | progression | death | |

| 7 | unspecified Aspergillus sp. | NA | 0.691 | stable | stable | |

| 8 | Lichtheimia corymbifera | 0.12 | 1.81 | partial | partial | |

| Possible | 9 | NA | NA | NA | partial | partial |

NA, not available.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed to guide treatment in four cases (Table 3). Although in vitro susceptibility data suggested that the Fusarium and coelomycetes isolates were not susceptible to posaconazole, these patients’ conditions continued to improve whilst on posaconazole. In one patient with a Fusarium isolate (patient no. 1), iv posaconazole (after 22 days of therapy) was replaced by iv voriconazole as the fungal isolate was deemed more susceptible to voriconazole, whilst the other patient (patient no. 4) continued receiving posaconazole oral suspension for 3 months, following 3 days of iv posaconazole therapy.

Three courses of iv posaconazole were prescribed in combination with liposomal amphotericin B for the treatment of mucormycete infections (two pulmonary and one rhino-orbital). Surgical resections of affected areas were performed in conjunction with the antifungal therapy in two cases. Improvement in signs and symptoms was observed in all three patients following the completion of iv posaconazole therapy.

Safety of iv posaconazole

The effect of iv posaconazole on liver and renal function at the end of treatment was minimal. No statistically significant difference was observed in ALT (P = 0.303), total bilirubin (P = 0.213) and calculated creatinine clearance (P = 0.927) at the commencement and cessation of iv posaconazole. However, six courses of iv posaconazole across both the prophylaxis and treatment groups were discontinued due to concern about thrombocytopenia (n = 1) or abnormal liver function (n = 5), which did not normalize upon or 7 days post-iv posaconazole cessation. These adverse events were observed [median (IQR)] 13 (9–19) days after iv posaconazole initiation. No instances of infusion-related reactions, QTc prolongation and electrolyte imbalances attributed to iv posaconazole were documented in the patients’ medical histories.

Trough plasma concentrations

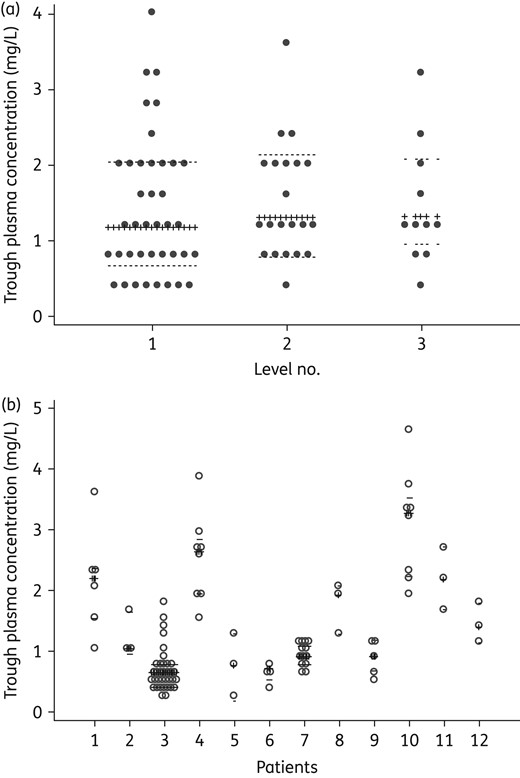

(a) Inter-patient variability in iv posaconazole Cmin. The dots indicate the distribution of posaconazole Cmin during the first (n = 39), second (n = 21), and third (n = 11) sampling in individual patients. (b) Intra-patient variability in iv posaconazole Cmin. Posaconazole Cmin of individual patients who had three or more levels measured throughout the study (n = 12, 94 levels) are shown. The crossed lines represent the median iv posaconazole concentration; dotted lines show the IQR.

Of the nine patients receiving iv posaconazole for treatment of IFD, Cmin was measured in seven, at a median (IQR) of 7 (2–15) days post-treatment initiation. Initial posaconazole Cmin was sub-therapeutic in two patients whilst the remaining five had posaconazole Cmin >1 mg/L (Table 3). Patients achieving therapeutic posaconazole Cmin appeared to have favourable treatment outcomes.

Discussion

The current study provides the first insight into the safety, clinical effectiveness and trough plasma concentrations of iv posaconazole beyond the clinical trial setting. Intravenous posaconazole was prescribed for either prophylaxis or treatment of IFD, predominantly in patients with haematological malignancies and recipients of allogeneic HSCT. The main reason for initiating iv posaconazole prophylaxis was concern about reduced bioavailability of posaconazole oral suspension associated with impaired GI absorption.

Our findings suggested that iv posaconazole was effective for prophylaxis against IFD as evidenced by the absence of breakthrough IFD during and at cessation of iv posaconazole. In contrast, four cases of possible IFD were reported in the 24 patients receiving 300 mg daily of iv posaconazole in the iv posaconazole Phase 1b study (two cases during iv posaconazole and the other two cases, 16 and 22 days after cessation of iv posaconazole).17 One case of proven aspergillosis was also reported, in the same patient cohort, 7 days after cessation of iv posaconazole, whilst the patient was on posaconazole oral suspension. In our study, however, patients receiving prophylaxis were followed only until cessation of iv posaconazole.

The safety profile observed with iv posaconazole in the current study was consistent with published data.17,18 Our experience suggests that iv posaconazole may be a viable alternative to the currently available mould-active antifungals, particularly for patients who are unable to take oral antifungals. Whilst previous randomized studies also reported no breakthrough IFD during iv voriconazole27 or liposomal amphotericin B28 prophylaxis, 21% and 7% of patients receiving iv voriconazole and liposomal amphotericin B prophylaxis, respectively, experienced antifungal-related adverse events requiring discontinuation of therapy. Indeed, the clinically significant side effects associated with voriconazole (visual disturbances, liver toxicity, hallucination, ototoxicity and neurotoxicity)27,29 and liposomal amphotericin B (infusion reactions and renal toxicity)30 are well described. Even though five courses of iv posaconazole prophylaxis in our study were discontinued due to concern about worsening liver function or thrombocytopenia, our patients had complex underlying conditions and treatments, including allogeneic HSCT, and were concurrently receiving other potentially hepatotoxic/myelosuppressive medications. In addition, the liver function or thrombocyte count did not normalize upon or 7 days post-cessation of iv posaconazole. As such, these specific adverse events could not be directly attributed to iv posaconazole. Notably, iv posaconazole in our study and in other studies17,18 has not been associated with renal toxicity, which can be difficult to manage in patients with haematological malignancies and recipients of allogeneic HSCT receiving multiple nephrotoxic medications, including immunosuppressants.

Whilst no infusion adverse events, QTc prolongation or electrolyte imbalances attributed to iv posaconazole were documented in our study, incidents of infusion site reactions and QTc prolongation have been reported following iv posaconazole.18 The absence of documented infusion site reactions in our study may possibly be due to the slower infusion rate used at our centres (90 min versus 30 min in the former study), or to incomplete documentation of the event given the retrospective nature of our study. We were unable to assess QTc prolongation in our study, as ECG was not routinely performed in all centres during iv posaconazole administration. Similarly, there were no suspected electrolyte disturbances attributed to iv posaconazole documented in our study, probably owing to the multiple medications, including potassium and magnesium supplements, our patients were receiving.

Interestingly, iv posaconazole may be a useful addition to liposomal amphotericin B for mucormycosis; a challenging IFD given the poor susceptibility of mucormycetes to many antifungals.31,32 Posaconazole is one of the few azoles that has in vitro activity against this fungal pathogen.31,32 Although treatment outcomes for the three patients with mucormycosis in the current analysis were favourable, it is important to note that early diagnosis and prompt initiation of antifungal therapy, surgical debridement of affected tissues and correction of predisposing factors are all critical to optimize treatment outcomes for mucormycosis.33

Whilst antifungal susceptibility testing may be helpful in guiding the management and predicting the treatment outcomes of certain IFD,34,35 it was not consistently undertaken in our institutions. The clinical application of antifungal susceptibility testing remains challenging, as it is time consuming and its interpretation can be difficult given the lack of data exploring the correlation between susceptibility data and clinical outcomes.36 In addition, the clinical breakpoints for posaconazole and various moulds remain to be fully elucidated.37–39 Consequently, clinical interpretation and use of antifungal susceptibility data to guide posaconazole therapy should therefore be exercised with care, as illustrated in two of our cases (patient nos. 1 and 4).

The plasma concentrations of iv posaconazole, to date, have been described only in the Phase 1b study, where the mean (CV%) average plasma concentrations sampled over 24 h (Cavg) and mean (CV%) Cmin at day 14 of 300 mg daily iv posaconazole therapy were 1.43 (42) mg/L and 1.05 (50) mg/L, respectively.17 The posaconazole plasma concentrations observed in our study appeared to be lower than those reported in the former study. In the Phase 1b study Cavg was the primary parameter, which is not usually measured in clinical practice, owing to increased cost and patient discomfort.40 Instead, Cmin is the preferred sampling point given its practicality, as reported in the current study.

Even though the median posaconazole Cmin in the current study was >1 mg/L, sub-therapeutic levels were observed in some individuals despite administration of the recommended dose. Of interest, the observed Cmin appeared not to be affected by loading dose or prior posaconazole oral suspension administration. Variations in posaconazole Cmin observed amongst the patients may be associated with the different assays adopted by the National Association of Testing Authorities accredited laboratories servicing our institutions. However, intra-patient variability remained, even when posaconazole Cmin was measured within the same institution. Whilst posaconazole oral suspension has been demonstrated to exhibit linear clearance, this has not been reported for iv posaconazole. In addition, changes in physiological functions have been shown to affect the pharmacokinetics of various antimicrobials in critically ill patients.41 However, there has been no study describing the pharmacokinetics of iv posaconazole in this patient cohort. Similarly, inhibition/induction or genetic polymorphisms of P-glycoprotein (P-gp)42,43 or UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGT)44,45 have also been reported to affect the plasma concentration of various medications that are metabolized via these pathways. Future studies should aim to determine factors affecting the plasma concentration of iv posaconazole so that patients affected can be identified at an early stage and have their posaconazole levels closely monitored. Additionally, further prospective studies should explore strategies to optimize therapeutic drug monitoring of iv posaconazole given the current dearth of information on dose adjustment in response to iv posaconazole Cmin.

Conclusions

Australia's first experience with iv posaconazole in a real-world setting suggests that iv posaconazole therapy was well tolerated and clinically effective for prophylaxis against IFD in patients with haematological malignancies. When prescribed for treatment of IFD, iv posaconazole also appeared to afford favourable outcomes. Given the observed variability in posaconazole plasma concentration in the current study, regular monitoring of posaconazole Cmin in patients receiving iv posaconazole should be considered and further research is needed to explore factors resulting in sub-therapeutic or variable posaconazole levels.

Funding

This was an investigator-initiated study supported by internal funding. The study did not receive any pharmaceutical industry support.

Transparency declarations

M. A. S. and S. C. A. C. have received grants from Pfizer, Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) and Gilead Sciences. D. C. M. K. has sat on advisory boards for Pfizer and MSD, and received financial/travel support unrelated to the current work from Roche, Pfizer, MSD and Gilead Sciences. K. U. has sat on an advisory board for MSD. M. R. A.-R. has received honoraria from Schering Plough and Gilead, grants from MSD and participated in an advisory board for MSD. A. Y. P. has been on an advisory board for MSD unrelated to the current work. P. H. has sat on an advisory board for Amgen. All other authors: none to declare.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary data from this work were presented as an oral presentation at the Australian Society for Antimicrobials 17th Annual Scientific Meeting ‘Antimicrobials 2016’, Melbourne, VIC, Australia (25–27 February 2016), abstract PP3.3.

References