-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Georgia Tobiano, Sharon Latimer, Elizabeth Manias, Andrea P Marshall, Megan Rattray, Kim Jenkinson, Trudy Teasdale, Kellie Wren, Wendy Chaboyer, Co-design of an intervention to improve patient participation in discharge medication communication, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 36, Issue 1, 2024, mzae013, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzae013

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients can experience medication-related harm and hospital readmission because they do not understand or adhere to post-hospital medication instructions. Increasing patient medication literacy and, in turn, participation in medication conversations could be a solution. The purposes of this study were to co-design and test an intervention to enhance patient participation in hospital discharge medication communication. In terms of methods, co-design, a collaborative approach where stakeholders design solutions to problems, was used to develop a prototype medication communication intervention. First, our consumer and healthcare professional stakeholders generated intervention ideas. Next, inpatients, opinion leaders, and academic researchers collaborated to determine the most pertinent and feasible intervention ideas. Finally, the prototype intervention was shown to six intended end-users (i.e. hospital patients) who underwent usability interviews and completed the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability questionnaire. The final intervention comprised of a suite of three websites: (i) a medication search engine; (ii) resources to help patients manage their medications once home; and (iii) a question builder tool. The intervention has been tested with intended end-users and results of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability questionnaire have shown that the intervention is acceptable. Identified usability issues have been addressed. In conclusion, this co-designed intervention provides patients with trustworthy resources that can help them to understand medication information and ask medication-related questions, thus promoting medication literacy and patient participation. In turn, this intervention could enhance patients’ medication self-efficacy and healthcare utilization. Using a co-design approach ensured authentic consumer and other stakeholder engagement, while allowing opinion leaders and researchers to ensure that a feasible intervention was developed.

Introduction

Improving medication safety is a priority in many health systems, yet 24–44% of recently discharged patients report not adhering to their hospital discharge medication regimen [1, 2]. Contributing factors include a lack of discussion of patients’ medication-related problems in hospital, misunderstanding administration directions, and lack of awareness of medication changes [3]. Non-adherence to hospital discharge medication regimens can result in poor outcomes, including patient harm and readmission to hospital [4]. In a 2018 systematic review of 19 studies, the median prevalence of medication-related readmissions was 21% (interquartile range (IQR) 14, 23%), and of these, 76% were deemed preventable [5]. Despite healthcare advances, it is clear that new approaches are required to ensure that patients can safely manage their medications after hospital discharge.

There is some evidence that patient participation improves medication adherence, which in turn can reduce medication-related harm [6] and subsequent hospital readmissions [7]. While patient participation can mean many things, it has been defined as the provision of choices for patients to take part in their care in an individualized manner, in collaboration with healthcare professionals, with the purpose of maximizing outcomes or enhancing patient experience [8]. One way that patients can participate is through medication communication. This is conceptualized as patients and healthcare professionals sharing information about medications in a patient-centred manner, and patients seeking clarification and contributing to decisions based on patient needs [9].

Medication communication can be complex and dauting for patients; thus, to feel confident to participate in these conversations, people require adequate levels of medication literacy [10]. Medication literacy is defined as ‘the degree to which individuals can obtain, comprehend, communicate, calculate, and evaluate patient-specific information about their medications to make informed medication and health decisions in order to safely and effectively use their medications… (p.10)’ [10]. People with low medication literacy are less likely to ask questions, such as why they should continue taking their medications [11].

Nevertheless, patient participation in medication conversations can be modified, from passive to more active levels of participation. In a 2017 systematic review, 8 out of the 10 interventions aimed at enhancing patient communication skills training showed significant changes in patients’ active communication, without increasing the duration of conversations with healthcare professionals [12]. This suggests a promising avenue for promoting patient participation to enhance medication safety outcomes. Considerably, less attention has been given to improving patient communication skills, as opposed to those of healthcare professionals [13]. Additionally, there is a paucity of communication interventions that encourage patient participation in medication conversations in the hospital setting, and these interventions were seldom developed with patient input [14]. Thus, targeting hospital patients is a novel opportunity to be explored. Co-design is when stakeholders, such as patients and healthcare professionals, are presented with a problem, and they actively collaborate to design solutions, usually in the early development phases of a project [15]. The aims of this study were to co-design and test an intervention to enhance patient participation in discharge medication communication.

Methods

This study involved co-design and testing of an intervention at one tertiary hospital in Queensland, Australia. The relevant hospital (HREC/2021/QGC/74 585) and university (GU: 2021/436, DU: 2021–216) Human Research Ethics Committees approved the study.

Co-design

The co-design framework for healthcare innovation [16] was used, which involves three steps: (i) predesign; (ii) co-design; and (ii) postdesign. The framework provides pragmatic guidance on how researchers can work with stakeholders to harness their expertise to co-design an intervention before formal pilot testing. The first two steps are process-related; with the approach we took as described in this ‘Methods’ section. The lead researcher (G.T.) and Project Lead were present for all meetings, and the Project Lead recorded meetings and wrote meeting notes after listening to recordings. Three stakeholder meetings occurred ∼1 month apart. After each stakeholder meeting, separate meetings were held with opinion leaders and then academic researchers.

Step1: Predesign

This step involves both ‘contextual inquiry’ and ‘preparation’ [16]. ‘Contextual inquiry’ is aimed at understanding end-user challenges and current practices. To carry out ‘contextual inquiry’, we undertook a series of activities including a systematic review, a mixed methods study, and an observational study (see results in Supplementary File 1). Our ‘preparation’ involved assembling the consumer and healthcare professional stakeholders who undertook co-design (see Table 1). The stakeholders were partners in the research process; thus, consent was not required. We hired a Project Lead who built rapport with stakeholders and developed a plan to meaningfully engage stakeholders in the project (see Supplementary File 2). A group of opinion leaders were also assembled alongside our academic research team, both groups’ purpose was to provide guidance to the facilitator (G.T.) and Project Lead running co-design meetings (Table 1).

Groups assembled for co-design (stakeholders n = 12) and to guide the co-design process (opinion leaders and academic researchers n = 9).

| Group type . | Description of group . | Members of group . | Method of identificationa . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders | Consumers and healthcare professionals who had experiential knowledge of the study topic. Consumers who had lived experience of hospital discharge, were aged ≥45 years, with ≥1 chronic illness and ≥1 regularly prescribed medication that they managed at home. Healthcare professionals who worked at the study hospital and had direct experience undertaking discharge medication communication with patients. | Consumers = 3 Doctors = 3 Nurses = 3 Pharmacists =3 | Consumers were recruited through an advertisement on Health Consumers Queensland website. Interested consumers returned an expression of interest form designed by Health Consumers Queensland that included age, gender, and self-identifiers such as living with a disability /chronic condition, carer responsibilities, physical isolation or transport disadvantage, culturally or linguistically diverse, from a non-English speaking background or LGBTIQA + . Applicants also provided insights into the support needed to be part of the project and their interest in the topic or role. The Project Lead conducted telephone meetings to delve deeper into applicants’ interest and discussed their experiences with medication communication at hospital discharge. From the pool, three diverse consumers were selected based on age, gender, self-identifiers, experiences, and interests. Healthcare professionals were recruited through our opinion leaders (see row below). Opinion leaders purposefully reached out to healthcare professionals with diverse experiences, and healthcare professionals who were interested were invited to be stakeholders. |

| Opinion leaders | Senior/managerial and influential consumers and healthcare professionals within the organisation with a direct interest in the study topic | Chair of consumer advisory group= 1 Medical Executive Director = 1 Nursing Safety and Quality Coordinator = 1 Pharmacy Assistant Director = 1 | Academic researchers had pre-existing relationships with these influential people and invited them onto the team. |

| Academic researchers | Researchers with expertise in medication safety and communication, patient participation, and/or intervention co-design. | Professors = 3 Senior Research Fellows = 2 | These were the research team members who led the study. |

| Group type . | Description of group . | Members of group . | Method of identificationa . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders | Consumers and healthcare professionals who had experiential knowledge of the study topic. Consumers who had lived experience of hospital discharge, were aged ≥45 years, with ≥1 chronic illness and ≥1 regularly prescribed medication that they managed at home. Healthcare professionals who worked at the study hospital and had direct experience undertaking discharge medication communication with patients. | Consumers = 3 Doctors = 3 Nurses = 3 Pharmacists =3 | Consumers were recruited through an advertisement on Health Consumers Queensland website. Interested consumers returned an expression of interest form designed by Health Consumers Queensland that included age, gender, and self-identifiers such as living with a disability /chronic condition, carer responsibilities, physical isolation or transport disadvantage, culturally or linguistically diverse, from a non-English speaking background or LGBTIQA + . Applicants also provided insights into the support needed to be part of the project and their interest in the topic or role. The Project Lead conducted telephone meetings to delve deeper into applicants’ interest and discussed their experiences with medication communication at hospital discharge. From the pool, three diverse consumers were selected based on age, gender, self-identifiers, experiences, and interests. Healthcare professionals were recruited through our opinion leaders (see row below). Opinion leaders purposefully reached out to healthcare professionals with diverse experiences, and healthcare professionals who were interested were invited to be stakeholders. |

| Opinion leaders | Senior/managerial and influential consumers and healthcare professionals within the organisation with a direct interest in the study topic | Chair of consumer advisory group= 1 Medical Executive Director = 1 Nursing Safety and Quality Coordinator = 1 Pharmacy Assistant Director = 1 | Academic researchers had pre-existing relationships with these influential people and invited them onto the team. |

| Academic researchers | Researchers with expertise in medication safety and communication, patient participation, and/or intervention co-design. | Professors = 3 Senior Research Fellows = 2 | These were the research team members who led the study. |

Note, these different groups partnered in the research process by co-designing the intervention; informed consent was not required.

Groups assembled for co-design (stakeholders n = 12) and to guide the co-design process (opinion leaders and academic researchers n = 9).

| Group type . | Description of group . | Members of group . | Method of identificationa . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders | Consumers and healthcare professionals who had experiential knowledge of the study topic. Consumers who had lived experience of hospital discharge, were aged ≥45 years, with ≥1 chronic illness and ≥1 regularly prescribed medication that they managed at home. Healthcare professionals who worked at the study hospital and had direct experience undertaking discharge medication communication with patients. | Consumers = 3 Doctors = 3 Nurses = 3 Pharmacists =3 | Consumers were recruited through an advertisement on Health Consumers Queensland website. Interested consumers returned an expression of interest form designed by Health Consumers Queensland that included age, gender, and self-identifiers such as living with a disability /chronic condition, carer responsibilities, physical isolation or transport disadvantage, culturally or linguistically diverse, from a non-English speaking background or LGBTIQA + . Applicants also provided insights into the support needed to be part of the project and their interest in the topic or role. The Project Lead conducted telephone meetings to delve deeper into applicants’ interest and discussed their experiences with medication communication at hospital discharge. From the pool, three diverse consumers were selected based on age, gender, self-identifiers, experiences, and interests. Healthcare professionals were recruited through our opinion leaders (see row below). Opinion leaders purposefully reached out to healthcare professionals with diverse experiences, and healthcare professionals who were interested were invited to be stakeholders. |

| Opinion leaders | Senior/managerial and influential consumers and healthcare professionals within the organisation with a direct interest in the study topic | Chair of consumer advisory group= 1 Medical Executive Director = 1 Nursing Safety and Quality Coordinator = 1 Pharmacy Assistant Director = 1 | Academic researchers had pre-existing relationships with these influential people and invited them onto the team. |

| Academic researchers | Researchers with expertise in medication safety and communication, patient participation, and/or intervention co-design. | Professors = 3 Senior Research Fellows = 2 | These were the research team members who led the study. |

| Group type . | Description of group . | Members of group . | Method of identificationa . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders | Consumers and healthcare professionals who had experiential knowledge of the study topic. Consumers who had lived experience of hospital discharge, were aged ≥45 years, with ≥1 chronic illness and ≥1 regularly prescribed medication that they managed at home. Healthcare professionals who worked at the study hospital and had direct experience undertaking discharge medication communication with patients. | Consumers = 3 Doctors = 3 Nurses = 3 Pharmacists =3 | Consumers were recruited through an advertisement on Health Consumers Queensland website. Interested consumers returned an expression of interest form designed by Health Consumers Queensland that included age, gender, and self-identifiers such as living with a disability /chronic condition, carer responsibilities, physical isolation or transport disadvantage, culturally or linguistically diverse, from a non-English speaking background or LGBTIQA + . Applicants also provided insights into the support needed to be part of the project and their interest in the topic or role. The Project Lead conducted telephone meetings to delve deeper into applicants’ interest and discussed their experiences with medication communication at hospital discharge. From the pool, three diverse consumers were selected based on age, gender, self-identifiers, experiences, and interests. Healthcare professionals were recruited through our opinion leaders (see row below). Opinion leaders purposefully reached out to healthcare professionals with diverse experiences, and healthcare professionals who were interested were invited to be stakeholders. |

| Opinion leaders | Senior/managerial and influential consumers and healthcare professionals within the organisation with a direct interest in the study topic | Chair of consumer advisory group= 1 Medical Executive Director = 1 Nursing Safety and Quality Coordinator = 1 Pharmacy Assistant Director = 1 | Academic researchers had pre-existing relationships with these influential people and invited them onto the team. |

| Academic researchers | Researchers with expertise in medication safety and communication, patient participation, and/or intervention co-design. | Professors = 3 Senior Research Fellows = 2 | These were the research team members who led the study. |

Note, these different groups partnered in the research process by co-designing the intervention; informed consent was not required.

Step 2: Co-design

The co-design step involved ‘framing the issue’, ‘generative design’, and ‘sharing ideas’ [16]. ‘Framing the issue’ ensured the stakeholders co-designing the intervention understood the problems and context, discussed their lived experiences, and shared goals and plans for co-design. Thus, in the first meeting, consumer and healthcare professional stakeholders met together and the facilitator (G.T.) shared previous research (step 1: contextual inquiry), which the group discussed in the context of their lived experience. Furthermore, the stakeholder group collectively agreed upon ground rules for future meetings, the mission, purpose, and group activities. At the end of the meeting, ‘generative design’ was encouraged, by asking stakeholders to reflect on what they wanted future patient participation in hospital discharge medication communication to look like. They were encouraged to write down ideas for possible approaches to achieve this, no matter how unusual, and were told to bring them to the next meeting. The approach of writing ideas independently reduced stakeholders’ influence on each other. Opinion leaders and then academic researchers met to discuss stakeholder meeting notes, and through discussion, guidance was provided to the meeting facilitator (G.T.) and Project Lead prior to the next stakeholder meeting.

In the second stakeholder group meeting, members were asked to ‘share ideas’ generated since the last meeting (1 month prior). The facilitator (G.T.) encouraged each stakeholder to speak, and as ideas emerged, other stakeholders built on the ideas. Individual face-to-face meetings occurred with stakeholders who were unable to attend scheduled meetings. Meetings were supplemented with ongoing email communication.

Step 3: Postdesign

The postdesign step involved ‘data analysis’ and ‘requirements translation’ (p. 8) [16]. The outcomes of this step are reported in the ‘Results’ section. ‘Data analysis’ began by sorting and distilling ideas that stakeholders generated in the co-design step into a list. Opinion leaders and academic researchers met; they reviewed and added to the list. The academic researchers discussed how to best prioritize the n = 10 ideas on the list and decided that broader consultation with end-users, beyond the stakeholder group, was required.

Thus, 15 end-users were recruited, consented, and individually presented examples of each intervention idea by the Project Lead. Their role was to prioritize intervention ideas. Intended end-users were hospital patients aged ≥45 years, with ≥1 chronic illness and ≥1 regularly prescribed medication from two medical units at the study site (a tertiary teaching hospital in southeast Queensland). Over 3 days, the Nurse Unit Manager or their designate screened all patients on the units for eligibility and then the Project Lead consecutively recruited eligible participants on the units until the Project Lead’s shift was complete. End-users ranked the intervention ideas from 1 (least preferred) to 10 (most preferred). During this process, end-users spoke about how they made decisions about the ranking and were asked probing questions to understand their selection process. The Project Lead asked the intended end-users how they would like the intervention delivered (e.g. electronic, paper-based, etc.) and documented field notes about their responses. The 15 end-user responses were summated; thus, the score for each potential intervention ranged from 15 to 150.

‘Requirements translation’ (p. 8) [16] involved a series of meetings; first consumer and healthcare professional stakeholders met together, then opinion leaders, and then academic researchers. Each group reviewed end-user rankings of intervention ideas, determined action items (i.e. what would be required to actualise the ideas), and the feasibility of these action items [16]. To ensure the intervention was feasible in terms of uptake and implementation, academic researchers decided to select the three intervention ideas that were ranked highest by intended end-users that were also deemed to be feasible by stakeholders and opinion leaders. Additionally, the academic research team developed a logic model to illustrate the causal pathways between planned research activities, the intervention, and intended outcomes, and how the context influenced the intended outcomes [11].

Finally, two consumers from the stakeholder group and the lead researcher completed action items for intervention ideas selected. Action items involved consumers reviewing existing resources that could address the intervention ideas. The consumers met with the lead researcher after reviewing and discussed their preferred resources, and when a resource was deemed as insufficient in addressing the intervention idea, consumers discussed their ideas for new resources that needed to be created. Consumers also developed the mode of delivery (i.e. poster). A website designer and graphic designer developed new resources and the poster; the lead researcher met with designers and shared consumers’ ideas for resources/poster content and layout. Consumers, opinion leaders, and research team members reviewed multiple versions of resources/poster, and designers actioned their feedback.

Testing the intervention

The prototype intervention was tested with end-users, which is common when designing new interventions. The role of these end-users was to test the content, format, and delivery method, which informed intervention refinement. The intervention was shown to six new intended end-users in-person by a hired study researcher, and they participated in semistructured think aloud usability interviews. The same inclusion criteria as intended end-users in ‘step 3: post-design’ were used. Usability questions related to the perceived ease of performing the intervention, end-user understanding of the intervention (i.e. clarity), and the logistics of implementing the intervention (i.e. resources and procedures) were used. This methodology only requires 5–10 participants to refine the intervention [17]. Interviews were audio-recorded and the researcher kept notes, to capture the intended end-users’ reactions while using the intervention.

After the interview, the eight-item Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) questionnaire was administered to end-users [18]. This questionnaire is used to determine intervention acceptability from intervention deliverer or recipient perspective [18]. Each item included in the TFA questionnaire reflected each of the seven TFA constructs: affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, intervention coherence, self-efficacy, opportunity costs, perceived effectiveness, and self-efficacy. There is also a final item that measures ‘general acceptability’ overall. This questionnaire has been systematically developed using a five-step prevalidation method for developing patient-reported outcome measures, and future psychometric assessment is planned. End-user demographic data were also gathered. Interviews were listened to by the lead researcher who wrote notes about usability issues that arose. Surveys and demographics were analysed using descriptive statistics. Based on the findings, the intervention was modified.

Rigour

Strategies to uphold credibility included the Project Lead building rapport with stakeholders to increase their comfort participating in co-design, triangulation of multiple perspectives (i.e. stakeholders, opinion leaders, and academic researchers) when making decisions and up-skilling the facilitator (G.T.) prior to conducting co-design meetings (see Supplementary File 2). For transferability, co-design group members were selected who experienced discharge medication communication. For dependability, an audit trail of documents is available, showing decisions made throughout the study. Finally, for confirmability, the lead researcher, and Project Lead met weekly throughout the co-design process, to critically reflect and ensure coherence between the study goals, stakeholders’ input, and outcomes [19]. Preconceptions that would influence the intervention were noted allowing the intervention to evolve without this influence.

Results

Outputs are reported in relation to the ‘Step 3: postdesign’ and ‘testing the intervention’ step.

Postdesign

Fifteen end-users prioritized the intervention ideas (Supplementary File 3), with two-thirds (n = 9; 60.0%) preferring to share discussions about medications (Table 2). Of the end-users, 66.7% (n = 10) were male and the median age was 65 years (IQR 56–75). Three prioritized intervention ideas were selected that were deemed feasible, and action items including creating new or selecting existing resources were executed. The first chosen intervention idea, ‘learn about medications’, aimed to provide hospital patients with easy access to specific medication information, believed to enhance patient learning and in turn, patient–healthcare professional medication communication in hospital. To action this idea, an existing ‘Medicine Finder’ website was utilized, allowing patients to look up lay language information about medications, including their purpose and side effects.

| Characteristics and survey responses . | End-users who prioritised intervention ideas Total Sample n = 15 . | End-users who tested the intervention Total Sample n = 6 . |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Females | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Males | 10 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| English preferred language at home | 15 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary school or less | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some high school | 8 (53.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| High school graduate | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Some college or university | 3 (20.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| University degree | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Postgraduate university | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| What role do you like in discussing your medicines with healthcare professionals (i.e. doctors, pharmacists, nurses)? | ||

| 9 (60.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| 6 (40.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| In general, you would rate your health as | ||

| Excellent | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Very good | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Good | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fair | 2 (13.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Poor | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Median (IQR) | ||

| Age (years) | 65 (56.0, 75.0) | 65 (51.5, 74.0) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 5.0 (3.9, 15.3) | 2.5 (1.0, 10.0) |

| Total number of discharge medications prescribed per patient | 5.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 6.5 (1.8, 12.3) |

| Characteristics and survey responses . | End-users who prioritised intervention ideas Total Sample n = 15 . | End-users who tested the intervention Total Sample n = 6 . |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Females | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Males | 10 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| English preferred language at home | 15 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary school or less | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some high school | 8 (53.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| High school graduate | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Some college or university | 3 (20.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| University degree | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Postgraduate university | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| What role do you like in discussing your medicines with healthcare professionals (i.e. doctors, pharmacists, nurses)? | ||

| 9 (60.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| 6 (40.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| In general, you would rate your health as | ||

| Excellent | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Very good | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Good | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fair | 2 (13.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Poor | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Median (IQR) | ||

| Age (years) | 65 (56.0, 75.0) | 65 (51.5, 74.0) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 5.0 (3.9, 15.3) | 2.5 (1.0, 10.0) |

| Total number of discharge medications prescribed per patient | 5.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 6.5 (1.8, 12.3) |

| Characteristics and survey responses . | End-users who prioritised intervention ideas Total Sample n = 15 . | End-users who tested the intervention Total Sample n = 6 . |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Females | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Males | 10 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| English preferred language at home | 15 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary school or less | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some high school | 8 (53.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| High school graduate | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Some college or university | 3 (20.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| University degree | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Postgraduate university | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| What role do you like in discussing your medicines with healthcare professionals (i.e. doctors, pharmacists, nurses)? | ||

| 9 (60.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| 6 (40.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| In general, you would rate your health as | ||

| Excellent | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Very good | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Good | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fair | 2 (13.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Poor | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Median (IQR) | ||

| Age (years) | 65 (56.0, 75.0) | 65 (51.5, 74.0) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 5.0 (3.9, 15.3) | 2.5 (1.0, 10.0) |

| Total number of discharge medications prescribed per patient | 5.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 6.5 (1.8, 12.3) |

| Characteristics and survey responses . | End-users who prioritised intervention ideas Total Sample n = 15 . | End-users who tested the intervention Total Sample n = 6 . |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Females | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Males | 10 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| English preferred language at home | 15 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary school or less | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some high school | 8 (53.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| High school graduate | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Some college or university | 3 (20.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| University degree | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Postgraduate university | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| What role do you like in discussing your medicines with healthcare professionals (i.e. doctors, pharmacists, nurses)? | ||

| 9 (60.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| 6 (40.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| In general, you would rate your health as | ||

| Excellent | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Very good | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Good | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fair | 2 (13.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Poor | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Median (IQR) | ||

| Age (years) | 65 (56.0, 75.0) | 65 (51.5, 74.0) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 5.0 (3.9, 15.3) | 2.5 (1.0, 10.0) |

| Total number of discharge medications prescribed per patient | 5.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 6.5 (1.8, 12.3) |

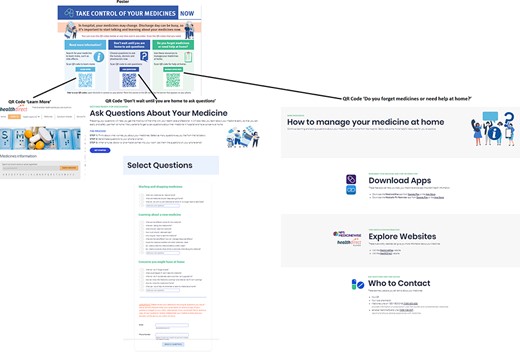

The second chosen intervention idea, ‘manage medications once home’, focused on supporting patients to independently manage their medications after discharge. To action this idea, a website was created with resources for continued learning once at home, tools for updating and tracking medications, and information on whom to contact in case of issues. The site also included links to existing apps for medication tracking and a hotline to contact.

The third chosen intervention idea, ‘ask questions about medications’, aimed to encourage patients to inquire about medications before hospital discharge. It was viewed as important that questions were easily visible, so that when healthcare professionals entered the room, patients would be reminded to ask questions. To action this idea, a question-building website, inspired by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) question builder, was designed. On the website, patients could select or add questions, receiving them via email or text as visible prompts to use during discharge medication discussions with healthcare professionals.

In terms of intervention delivery, field notes revealed that the end-users wanted an electronic intervention (e.g. websites, apps), but the intervention needed unrestricted access so that hospital patients could access when needed. Thus, a poster was designed with QR codes linking to the three intervention ideas. All three intervention ideas had separate websites with distinct domain names; however, there were links on each individual website allowing users to navigate between the three websites.

During the postdesign step, the logic model was developed and refined by academic researchers (Fig. 1).

Testing the intervention

Six intended end-users tested the prototype intervention (see Table 2). End-user median age was 65 years (IQR 51.5, 74.0) and half were females. Intended end-users had a median hospital length of stay of 2.5 days (IQR 1.0, 10.0), were prescribed a median of 6.5 medications (IQR 1.8, 12.3), and most preferred shared medication discussions with healthcare professionals (n = 5, 83.3%).

For the TFA questionnaire, all participants chose the two most positive response options for 7/8 items, and for the item ‘there are moral or ethical consequences using the poster with QR codes and the websites’, n = 4 (66.7%) strongly disagreed, n = 1 (16.7%) had no opinion, and n = 1 (16.7%) agreed (see Supplementary File 4). Usability interviews revealed issues that were actioned to refine the intervention (see Supplementary File 5). The final intervention is available in Fig. 2.

Pictures of the intervention (three websites) and mode of delivery (poster)

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

The final intervention was based on ideas generated by stakeholders that were deemed feasible and included providing patients with access to websites and apps that facilitate searching for medication information, asking questions about medications, and managing medications at home. The prototype intervention was tested with intended end-users and it is acceptable to them. The website was refined based on usability feedback.

Interpretation within the context of the wider literature

Creative intervention ideas were developed during co-design; similar to previous work [20]. Previous researchers suggest that consumers’ creativity is often linked to their determination to improve healthcare, while healthcare professionals’ knowledge of the reality of everyday practice prompts them to think of new ways of working [20]. Our Project Lead undertook intensive preparation for co-design meetings and built rapport with stakeholders, which may have also facilitated their meaningful engagement resulting in novel ideas [21]. Like other projects, in the postdesign step, we had opinion leaders and researchers who relied on practical resources and evidence, to ensure that innovative ideas were actioned into feasible interventions [20]. Co-design required a careful balance between innovation and feasibility, and we recommend careful assembly of group members to enact this process.

We used many existing evidence-based government health agency apps and websites because consumer stakeholders selected them, and they provided evidence-based information [22], and underwent intensive development processes to meet consumer needs [23]. The AHRQ is a US health agency, which provides resources to make care safer and of higher quality; however, these are often slow to diffuse into practice [24]. Our research efforts bridge this gap by prompting direct patient access to trusted and tailored information resources, by scanning a QR code on their mobile phone. This is timely, as many patients use the internet to seek medication information; however, when discerning between different websites, patients depend on a ‘vibe’ or a ‘feeling’ and view a range of websites as credible including those developed by pharmaceutical companies, government health agencies, and other consumers with experience [25]. Our research supported patient access to reliable and current government health agency medication information, while helping to reduce medical misinformation, a complex and multifaceted issue.

We developed our own medication question builder, despite resources being available. For example, the AHRQ question builder was rigorously adapted for the Australian context by Healthdirect, a national health advice service that provides trusted health information. However, this question builder is more suitable for General Practitioner consultations [26], as questions do not focus on in-hospital changes to medication. While many interventions that encourage patients to reflect on their own health/needs/concerns prior to interacting with healthcare professionals occur in community settings, a recent systematic review indicated that these types of interventions can improve patient communication in hospital settings [27]. Overall, there are many opportunities to adapt community resources for hospital settings.

Implications for policy, practice, and research

Further research is required to demonstrate the intervention is effective and cost effective, before the intervention can be implemented into practice. We have tested usability and end-user acceptability for the intervention, in anticipation of plans to further test the intervention as per the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions [28]. First, we will test our study and implementation process in a pilot study before undertaking a larger effectiveness trial [28]. Researchers have demonstrated that anticipated acceptability and experienced acceptability are highly correlated. Thus, based on our study findings, it is likely that future patients will experience the intervention as being acceptable [29], which gives our team confidence to progress with a pilot study.

Strengths and limitations

First, the major study strength was many preexisting health agency websites and apps were used, which represents good use of time and resources for both researchers and health agencies. Second, a hired researcher collected data from end-users meaning the hired researchers did not have a vested interest in the research topic and encouraged end-users to share their perspectives freely, possibly reducing social desirability bias. Third, using a graphic designer and website designer resulted in the production of usable professional websites and poster. However, the lead researcher was a go-between these designers and other groups. This could have been a limitation, as the designers may not fully appreciate consumers’ or others’ opinions when they are delivered by a researcher, and vice versa [30]. It is possible that final designs may have been different if we brought designers and other groups together. The fourth limitation was that more creative approaches in the ‘generating idea’ step of co-design could have been used, such as story-telling activities with illustrations [16]. Finally, the end-users who tested the prototype intervention all preferred to speak English, and it would be important to undertake further testing of the intervention with end-users who speak other languages at home, to see how the intervention needs to be adapted for other groups.

Conclusion

We co-designed an intervention to enhance patient participation in hospital discharge medication communication that consists of three websites: a medication search engine, question builder, and resources to manage medications at home. The mixture of new and existing websites has been tested, and the intervention is usable and acceptable to the target population. In accordance with the logic model, the assumed outcomes of the intervention include improved medication literacy, which in turn could enhance patient self-efficacy and reduce unnecessary medication-related healthcare utilizations; however, ongoing testing of the intervention is required to confirm these outcomes prior to implementation into practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Margaret Shapiro, for her input as a health consumer on the opinion leader group, and Lucy Hervey for collecting data during intervention testing.

Author contributions

We attest that all named authors: made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work (G.T., S.L., E.M., A.P.M., and W.C.); or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work (G.T., S.L., E.M., A.P.M., M.R., K.J., T.T., K.W., and W.C.); drafted the work or reviewed it critically for important intellectual content (G.T., S.L., E.M., A.P.M., M.R., K.J., T.T., K.W., and W.C.); approved the final version to be published (G.T., S.L., E.M., A.P.M., M.R., K.J., T.T., K.W., and W.C.); and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (G.T., S.L., E.M., A.P.M., M.R., K.J., T.T., K.W., and W.C.).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at IJQHC online.

Conflict of interests

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the Gold Coast Health and Gold Coast Foundation Collaborative Research Grant Scheme (RGS2020-038). Two researcher’s salaries (G.T. and S.L.) were funded by the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Wiser Wound Care.

Data Availability Statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly. On reasonable request, we can approach our ethics committee about the option of sharing data.

References

Author notes

Handling Editor: Dr. Aziz Sheikh