-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Junyao Zheng, Yongbo Lu, Wenjie Li, Bin Zhu, Fan Yang, Jie Shen, Prevalence and determinants of defensive medicine among physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 35, Issue 4, 2023, mzad096, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzad096

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

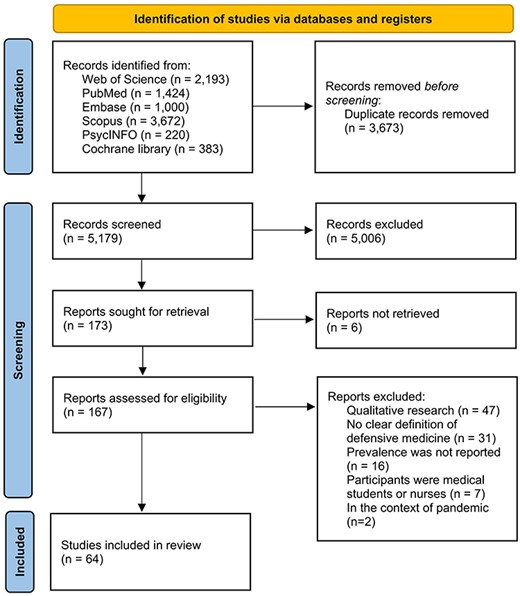

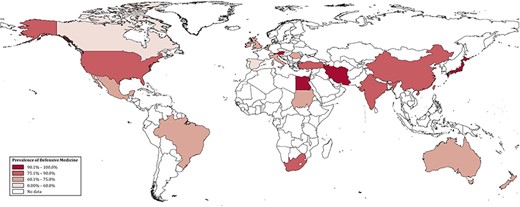

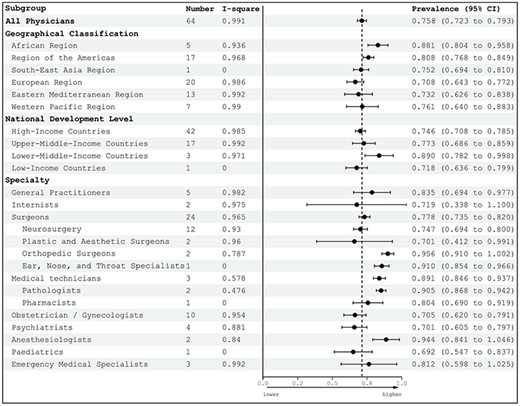

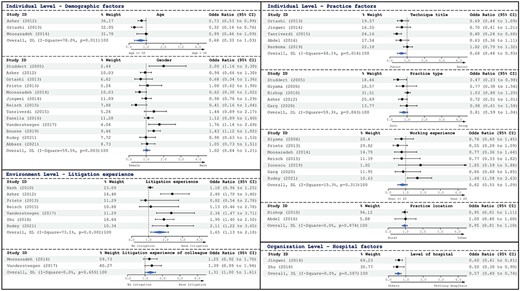

Defensive medicine, characterized by physicians’ inclination toward excessive diagnostic tests and procedures, has emerged as a significant concern in modern healthcare due to its high prevalence and detrimental effects. Despite the growing concerns among healthcare providers, policymakers, and physicians, comprehensive synthesis of the literature on the prevalence and determinants of defensive medicine among physicians has yet been reported. A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify eligible studies published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2022, utilizing six databases (i.e. Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library). A meta-analysis was conducted to determine the prevalence and determinants of defensive medicine. Of the 8892 identified articles, 64 eligible studies involving 35.9 thousand physicians across 23 countries were included. The overall pooled prevalence of defense medications was 75.8%. Physicians engaged in both assurance and avoidance behaviors, with the most prevalent subitems being increasing follow-up and avoidance of high-complication treatment protocols. The prevalence of defensive medicine was higher in the African region [88.1%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 80.4%–95.8%] and lower-middle-income countries (89.0%; 95% CI: 78.2%–99.8%). Among the medical specialties, anesthesiologists (92.2%; 95% CI: 89.2%–95.3%) exhibited the highest prevalence. Further, the pooled odds ratios (ORs) of the nine factors at the individual, relational, and organizational levels were calculated, and the influence of previous experience in medical-legal litigation (OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.13–2.18) should be considered. The results of this study indicate a high global prevalence of defensive medicine among physicians, underscoring the necessity of implementing targeted interventions to reduce its use, especially in certain regions and specialties. Policymakers should implement measures to improve physicians’ medical skills, enhance physician–patient communication, address physicians’ medical-legal litigation fears, and reform the medical liability system. Future research should focus on devising and assessing interventions to reduce the use of defensive medicine and to improve the quality of patient care.

Introduction

Defensive medicine has become a prominent issue in contemporary healthcare, marked by physicians’ tendency to order excessive diagnostic tests, procedures, or referrals and avoid certain patients and procedures [1, 2]. It is often motivated by concerns about litigation and malpractice claims rather than by patients’ best interests, potentially decreasing the quality while increasing the costs of patient care [3]. Previous studies indicate that defensive medicine can be divided into assurance and avoidance behavior [4, 5]. Assurance behavior is regarded as a positive defensive medicine that prevents unnecessary and additional medical treatments [6], whereas avoidance behavior is considered a negative defense behavior. Owing to the fear of becoming involved in medical litigation, physicians implement avoidance behaviors by avoiding high-risk procedures or patients [7]. These phenomena have been linked to various negative outcomes, including increased healthcare costs, reduced quality of care, and patient harm [8–10].

The prevalence of defensive medicine significantly varies across countries and specialties. A comprehensive national study revealed that 92% of physicians in the USA engaged in defensive medicine practices [10]. In contrast, European data indicated that 74.4% of Belgian physicians and 45.39% of Spanish physicians reported employing such practices [11, 12]. Moreover, physicians of different specialties were found to have different degree of defensive medicine utilization. Several factors have been identified as the determinants, including practice type [4], previous experiences with medical-legal litigation [13, 14], and pressure from patients or colleagues [13]. Moreover, healthcare system factors such as reimbursement policies, quality metrics, and regulatory requirements may also contribute to the prevalence of defensive medicine [3, 15].

To date, there has been no comprehensive synthesis of existing literature on the prevalence and determinants of defensive medicine among physicians. By identifying the prevalence and determinants of defensive medicine among physicians, this systematic review aimed to inform the development of targeted interventions to reduce defensive medicine practices and promote high-quality patient-centered care.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

As defensive medicine is a multifaceted phenomenon involving medicine, law, and society, multiple electronic literature databases were used. In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16], we conducted a comprehensive literature search spanning from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2022 across six major and comprehensive databases: Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. A broad search strategy was used to minimize the risk of bias. Based on the standardized Medical Subject Headings term ‘defensive medicine’ in the PubMed database, four groups of keywords were generated. The full search strategy is shown in Supplemental File 1.

EndNote software (version 20) was employed to manage the citations.

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were defined: (i) defensive medicine was performed by or related to practicing physicians from any specialty; (ii) the concept of defensive medicine was clearly defined; (iii) the prevalence of defensive medicine among physicians was explicitly reported, including both overall and subitems; (iv) studies that reported defensive medicine among physicians not in emergencies or extreme circumstances (such as warfare or pandemic); (v) original studies being published in peer-reviewed journals; (vi) full text was available; and (vii) for duplicate publications, the most extensive studies were included.

Study selection and data extraction

Two investigators independently screened the titles and abstracts generated by the search strategy. Once one of the investigators determined that an abstract was eligible, a full-text article was obtained. Subsequently, two investigators examined the full texts and assessed the final study inclusion by referring to the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by a third investigator. To determine whether additional articles should be included, the reference lists of the included studies were manually searched. Finally, all investigators participated in data extraction.

Information about defensive medicine and its determinants was extracted from each included study using a standardized form (Table 1). Descriptive details included the first author, year of publication, research location, medical specialty investigated, sample size, outcome dimensions, influencing factors, and definition of defensive medicine. The authors of the included studies were contacted for additional clarification or data if needed.

| No . | First author . | Publication year . | Location . | Specialty . | Sample size . | Outcome dimension . | Influencing factorsh . | Definition of defensive medicine . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Summerton | 2000 | UK | General practitioners | 339 | Subitems | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 2 | Symon | 2000 | UK | Midwives and obstetrician | 211 | Overall | N/A | Personally changed practice as a result of the fear of litigation |

| 3 | Passmore | 2002 | UK | Psychiatrists | 95 | Overall | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 4 | Toker | 2004 | Israel | Ear, nose, and throat physicians | 194 | Subitems | N/A | A physician’s deviation from what is considered to be good practice to prevent complaints from patients or their families |

| 5 | Studdert | 2005 | USA | Multiple specialtiesa | 824 | Subitems | Gender, insurance coverage, premium burden, experience of being dropped by insurer practice type, and working experience | Physicians alter their clinical behavior because of the threat of malpractice liability |

| 6 | Sánchez-González | 2005 | Mexico | Unclear | 613 | Overall | N/A | Application of treatments, tests, and procedures with the explicit main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies, over and above the diagnosis or treatment of the patient |

| 7 | Hiyama | 2006 | Japan | Gastroenterologists | 131 | Overall | Working experience and practice type | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by the threat of liability claims |

| 8 | Krawitz | 2006 | New Zealand | Clinician | 26 | Overall | Public and mass media attention, Ministry of Health, requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine, and politicians and policy | Taken a treatment approach not likely to be in the client’s best interest but protects from medicolegal repercussions |

| 9 | Mullen | 2008 | New Zealand | Psychiatrists | 86 | Subitems | N/A | Additional effort, of marginal clinical utility, is made to avoid complaint or legal liability |

| 10 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners | 307 | Overall | Fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel order unnecessary treatments (positive defensive medicine) or avoid high-risk procedures or patients (negative defensive medicine) with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to damages claims |

| 11 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners, anesthetists, and surgeons | 102 | Overall | Age, fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel effect unnecessary treatments or avoid high-risk procedures, with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to malpractice litigation |

| 12 | Bishop | 2010 | USA | Multiple specialtiesb | 1231 | Overall | Gender, practice location (rural or urban), practice type, source of income, and hour-long patient care | Physicians order more tests and procedures than patients need to protect themselves from malpractice suits |

| 13 | Nash | 2010 | Australia | Multiple specialtiesb | 2999 | Subitems | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Perceived change in practice behavior due to concerns about medicolegal negligence claims and complaints |

| 14 | Anderson | 2011 | USA | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 241 | Subitems | Age, career satisfaction, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, insurance premium evolution, and malpractice crisis level of the region | Changes in practices due to malpractice concern |

| 15 | Leary | 2011 | USA | Residents (surgical versus medical) | 76 | Overall | N/A | A deviation from sound medical practice that physicians engage in primarily because they perceive a threat of liability |

| 16 | Asher | 2012 | Israel | Multiple specialtiesc | 877 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, exposure to complaint, practice type, managerial job, career satisfaction, and owning private malpractice insurance | Ordering of tests, procedures, and visits or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures, primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 17 | Nahed | 2012 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1028 | Subitems | N/A | Perception changes actions solely to mitigate liability risk |

| 18 | Manish | 2012 | USA | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 1214 | Subitems | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate physicians from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 19 | Asher | 2013 | Israel | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Subitems | Age, gender, concern over potential medicolegal litigation, practice location (rural or urban), and professional status | Medical actions, performed mainly in order to refrain from being sued rather than actually aiding the patient |

| 20 | Ortashi | 2013 | UK | Unclear | 204 | Overall | Age, gender, technical title, and specialty | A doctor’s deviation from their usual behavior or that considered good practice, to reduce or prevent complaints or criticism by patients or their families |

| 21 | Prieto-Miranda | 2013 | Mexico | Multiple specialtiesd | 246 | Overall | Age, gender, work shifts, specialty, professional certification, working experience, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Aapplication of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the objective of diagnosing and adequately treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 22 | Jingwei | 2014 | China | Unclear | 504 | Overall | Gender, working experience, education, specialty, technical title, monthly payroll income, workload, type of hospital, and exposure to medical dispute | Medical practice based on fear of legal liability rather than on patients’ best interests |

| 23 | Moosazadeh | 2014 | Iran | General practitioners | 423 | Subitems | Age, gender, working experience, insurance coverage, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Every therapeutic test or method, whose primary aim is to protect the physician against the threat of being accused of making a forensic medicine mistake or of being sued for medical mistakes |

| 24 | Roytowski | 2014 | South Africa | Neurosurgeons | 66 | Subitems | N/A | Changing practice behavior to try to minimize the risk of a lawsuit |

| 25 | Solaroglu | 2014 | Turkey | Neurosurgeons | 404 | Overall | Gender, working experience, types of hospital, and the geographic regions | Medical practices that help doctors avoid liability without providing any additional benefit to the patient |

| 26 | Bourne | 2015 | UK | Multiple specialties | 7926 | Subitems | Exposure to complaint, length of investigation, outcome of investigation, complaint source, and type of complaint | Broadly categorized into ‘hedging’ and ‘avoidance’. Hedging is when doctors are overcautious, leading to overprescribing, referring too many patients or over investigation. Avoidance includes not taking on complicated patients and avoiding certain procedures or more difficult cases |

| 27 | Motta | 2015 | Italy | Otolaryngology | 100 | Overall | Concern over potential medicolegal disputes, concern over variations in the doctor/patient relationship, and knowledge of insurance clauses | Defensive medicine is defined as the ordering of tests and procedures (positive defensive medicine) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine), primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 28 | Osti | 2015 | Austria | Multiple specialtiese | 193 | Overall | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate doctors from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 29 | Reisch | 2015 | USA | Breast pathologists | 252 | Overall | Age, gender, geographic region, medical skills training, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, working experience, workloads, and exposure to medical malpractice | A deviation from standard medical practice induced primarily by a threat of liability |

| 30 | Smith | 2015 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1026 | Overall | Working experience, reimbursement patterns, claims history, insurance coverage and cost, malpractice crisis level of the region, and patients with public insurance | An incentive to administer precautionary treatment with minimal expected medical benefit out of fear of litigation |

| 31 | Tanriverdi | 2015 | Turkey | Medical oncologists | 124 | Overall | Age, gender, academic occupation, working experience, type of hospital, and occupational status | Occasionally indulging unnecessary treatment requests to defend against lawsuits for medical errors and the use of unapproved medical applications |

| 32 | Abdel | 2016 | Sudan | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Overall | Working experience, professional certification, technical title, and type of hospital | A doctor’s deviation from the usual practice in order to reduce or prevent criticism and/or complaints by patients or their relatives |

| 33 | Panella | 2016 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, working experience, workload, and perception of being a ‘second victim’i | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 34 | Silberstein | 2016 | Israel | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 78 | Overall | Gender, working experience, managerial job, exposure to medicolegal literature, and requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine | Medical practices carried out primarily to avoid malpractice liability rather than to benefit the patient |

| 35 | Smith | 2016 | Canada | Neurosurgeons | 75 | Subitems | N/A | A deviation from regular medical practice because of medicolegal fears |

| 36 | Yan | 2016 | Cross-nationf | Neurosurgeons | 1142 | Overall | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care or avoiding high-risk situations out of fear of litigation |

| 37 | Din | 2017 | USA | Spine neurosurgery | 1024 | Overall | Malpractice crisis level of the region, premium burden, patients with public insurance, and exposure to malpractice claims | The provision of services beyond what is needed to improve patient outcomes (assurance behavior) and the evasion of high-risk procedures (avoidance behavior) to either deter litigation or substantiate clinical decision-making in the court |

| 38 | Olcay | 2017 | Turkey | Cardiologists | 253 | Overall | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Establishing diagnoses that would not alter patient care and performing unnecessary testing and treatments |

| 39 | Panella | 2017 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Exposure to malpractice claims, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of a request for compensation, fear of negative publicity, ineffective physician–patient relationship, insurance coverage, hospital support for liability issues, and public and mass media attention | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 40 | Ramírez-Alcántara | 2017 | Turkey | General practitioners | 87 | Overall | Work shifts | Application of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the aim of properly diagnosing and treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 41 | Reuveni | 2017 | Israel | Psychiatrists | 213 | Subitems | N/A | Medical actions that deviate from sound medical practice, performed primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability or to provide legal protection in the case of a malpractice lawsuit |

| 42 | Vandersteegen | 2017 | Belgium | Multiple specialties | 508 | Overall | Age, gender, region, working experience, insurance premium evolution, incitement by fund for medical accidents, consequences of medical lawsuit, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | The avoidance of certain high-risk procedures or patients or the ordering of procedures, tests, or visits, primarily (but not solely) due to the threat of medical liability |

| 43 | Yan | 2017 | Netherlands | Neurosurgeons | 45 | Subitems | N/A | A departure from standard medical practices out of fear of litigation |

| 44 | Tebano | 2018 | Cross-nationg | Antibiotic stewards | 830 | Subitems | Specialty, geographic regions, age, type of employment (contract or permanent), and fear of medical-legal litigation | When physicians perceive litigation as a threat, they may adopt defensive behaviors as a way to reduce the chances of litigation or to ensure a form of defense in the case of malpractice claims |

| 45 | Titus | 2018 | USA | Melanoma pathologists | 207 | Subitems | N/A | Behaviors that are intended to reduce exposure to malpractice litigation but may not clinically benefit the patient |

| 46 | Zhu | 2018 | China | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 1486 | Overall | Gender, level of hospital, education, specialty, exposure to medical dispute, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, consequences of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | The alterations of modes of medical practice, induced by the threat of liability, for the principal purposes of forestalling lawsuits by patients as well as providing good legal defense in the event that such lawsuits are instituted |

| 47 | Delice | 2019 | Turkey | Emergency medical specialists | 321 | Overall | N/A | Physicians requesting additional tests in the absence of indications or else avoiding high-risk patient groups in which adverse outcomes may occur during diagnosis and treatment |

| 48 | Ionescu | 2019 | Romania | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 73 | Overall | Working experience | A cesarean delivery recommended by the doctor in the absence of any clear medical indication that such a delivery method is needed to avoid possible litigation or a possible accusation of malpractice (defensive cesarean section) |

| 49 | Renkema | 2019 | Netherlands | Multiple specialties | 214 | Subitems | Age, specialty, technical title, attitude toward justified/unjustified litigation, and perceived patient pressure | The ordering of extra tests or procedures (assurance behavior) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (avoidance behavior), primarily to reduce the risk of being held liable for malpractice |

| 50 | Qiao | 2019 | China | Multiple specialties | 226 | Overall | N/A | Prescribe procedures or diagnostic tests or drugs that are clinically unnecessary to avoid possible troubles (such as lawsuits and disputes) |

| 51 | Garg | 2020 | India | Neurosurgeons | 214 | Subitems | Working experience and practice type | Clinical and operative practices to prevent medicolegal issues |

| 52 | Borgan | 2020 | USA | Internal medicine residents | 49 | Subitems | N/A | The deviation from routine medical care in order to avoid or reduce the risk of real or perceived future legal consequences |

| 53 | Calikoglu | 2020 | Turkey | Surgeons | 190 | Overall | Gender, academic occupation, specialty, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Medical behaviors that avoid physician liability without providing increased benefits to the patient |

| 54 | Gadjradj | 2020 | Cross-nation | Neurosurgeons | 490 | Subitems | N/A | Perform unnecessary, additional therapeutic or diagnostic interventions that do not improve the medical condition of the patient (positive defensive medicine), or it may cause physicians to refer or refuse difficult cases (negative defensive medicine) |

| 55 | Abbass | 2021 | Egypt | Multiple specialties | 261 | Subitems | Gender and specialty | The overuse of the resources such as ordering unnecessary investigations, giving treatment, or performing procedures aiming at doctors’ self-protection against claims rather than for the patient best interest |

| 56 | Fineschi | 2021 | Italy | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 168 | Subitems | N/A | The practice of recommending a diagnostic test or medical treatment (positive defensive medicine) or avoidance of risky patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine) that serves the function to protect physicians against patients’ claims |

| 57 | Kolcu | 2021 | Turkey | General practitioners | 196 | Subitems | N/A | The cost-increasing, defensive, or avoidance behavior displayed by physicians in healthcare delivery in order to protect themselves from legal problems |

| 58 | Perea-Pérez | 2021 | Spain | Emergency physicians | 1449 | Subitems | N/A | The making of clinical decisions that, while being explainable, prioritize the doctor’s legal security over other healthcare considerations |

| 59 | Rudey | 2021 | Brazil | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 403 | Overall | Gender, working experience, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | A practice wherein a healthcare professional makes decisions out of fear of litigation and not for the benefit of the patients |

| 60 | Ekici | 2021 | Turkey | Oral and maxillofacial surgeons | 109 | Subitems | N/A | A medical behavior that avoids medical responsibility without offering the patient greater benefits |

| 61 | Tumelty | 2021 | Ireland | Surgeons | 157 | Subitems | N/A | Behaviors engaged in by physicians for the purposes of averting the threat of medical negligence litigation and/or complaints |

| 62 | Zaed | 2021 | Italy | Neurosurgeons | 64 | Subitems | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care to minimize litigation exposure (positive defensive medicine) or the practice of avoiding more risky, albeit important, treatment measures to avoid litigation exposure (negative defensive medicine) |

| 63 | Vizcaino-Rakosnik | 2022 | Spain | Unclear | 282 | Overall | N/A | Made changes in their clinical practice because of the experience of being claimed |

| 64 | Shehata | 2022 | Egypt | Anesthesiologists | 177 | Subitems | Age, gender, marital status, technical title, professional certification, practice location, and type of employment (contract or permanent) | Defensive medicine occurs when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits or avoid high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily or solely) to reduce their exposure to malpractice liability |

| No . | First author . | Publication year . | Location . | Specialty . | Sample size . | Outcome dimension . | Influencing factorsh . | Definition of defensive medicine . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Summerton | 2000 | UK | General practitioners | 339 | Subitems | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 2 | Symon | 2000 | UK | Midwives and obstetrician | 211 | Overall | N/A | Personally changed practice as a result of the fear of litigation |

| 3 | Passmore | 2002 | UK | Psychiatrists | 95 | Overall | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 4 | Toker | 2004 | Israel | Ear, nose, and throat physicians | 194 | Subitems | N/A | A physician’s deviation from what is considered to be good practice to prevent complaints from patients or their families |

| 5 | Studdert | 2005 | USA | Multiple specialtiesa | 824 | Subitems | Gender, insurance coverage, premium burden, experience of being dropped by insurer practice type, and working experience | Physicians alter their clinical behavior because of the threat of malpractice liability |

| 6 | Sánchez-González | 2005 | Mexico | Unclear | 613 | Overall | N/A | Application of treatments, tests, and procedures with the explicit main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies, over and above the diagnosis or treatment of the patient |

| 7 | Hiyama | 2006 | Japan | Gastroenterologists | 131 | Overall | Working experience and practice type | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by the threat of liability claims |

| 8 | Krawitz | 2006 | New Zealand | Clinician | 26 | Overall | Public and mass media attention, Ministry of Health, requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine, and politicians and policy | Taken a treatment approach not likely to be in the client’s best interest but protects from medicolegal repercussions |

| 9 | Mullen | 2008 | New Zealand | Psychiatrists | 86 | Subitems | N/A | Additional effort, of marginal clinical utility, is made to avoid complaint or legal liability |

| 10 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners | 307 | Overall | Fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel order unnecessary treatments (positive defensive medicine) or avoid high-risk procedures or patients (negative defensive medicine) with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to damages claims |

| 11 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners, anesthetists, and surgeons | 102 | Overall | Age, fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel effect unnecessary treatments or avoid high-risk procedures, with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to malpractice litigation |

| 12 | Bishop | 2010 | USA | Multiple specialtiesb | 1231 | Overall | Gender, practice location (rural or urban), practice type, source of income, and hour-long patient care | Physicians order more tests and procedures than patients need to protect themselves from malpractice suits |

| 13 | Nash | 2010 | Australia | Multiple specialtiesb | 2999 | Subitems | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Perceived change in practice behavior due to concerns about medicolegal negligence claims and complaints |

| 14 | Anderson | 2011 | USA | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 241 | Subitems | Age, career satisfaction, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, insurance premium evolution, and malpractice crisis level of the region | Changes in practices due to malpractice concern |

| 15 | Leary | 2011 | USA | Residents (surgical versus medical) | 76 | Overall | N/A | A deviation from sound medical practice that physicians engage in primarily because they perceive a threat of liability |

| 16 | Asher | 2012 | Israel | Multiple specialtiesc | 877 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, exposure to complaint, practice type, managerial job, career satisfaction, and owning private malpractice insurance | Ordering of tests, procedures, and visits or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures, primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 17 | Nahed | 2012 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1028 | Subitems | N/A | Perception changes actions solely to mitigate liability risk |

| 18 | Manish | 2012 | USA | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 1214 | Subitems | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate physicians from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 19 | Asher | 2013 | Israel | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Subitems | Age, gender, concern over potential medicolegal litigation, practice location (rural or urban), and professional status | Medical actions, performed mainly in order to refrain from being sued rather than actually aiding the patient |

| 20 | Ortashi | 2013 | UK | Unclear | 204 | Overall | Age, gender, technical title, and specialty | A doctor’s deviation from their usual behavior or that considered good practice, to reduce or prevent complaints or criticism by patients or their families |

| 21 | Prieto-Miranda | 2013 | Mexico | Multiple specialtiesd | 246 | Overall | Age, gender, work shifts, specialty, professional certification, working experience, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Aapplication of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the objective of diagnosing and adequately treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 22 | Jingwei | 2014 | China | Unclear | 504 | Overall | Gender, working experience, education, specialty, technical title, monthly payroll income, workload, type of hospital, and exposure to medical dispute | Medical practice based on fear of legal liability rather than on patients’ best interests |

| 23 | Moosazadeh | 2014 | Iran | General practitioners | 423 | Subitems | Age, gender, working experience, insurance coverage, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Every therapeutic test or method, whose primary aim is to protect the physician against the threat of being accused of making a forensic medicine mistake or of being sued for medical mistakes |

| 24 | Roytowski | 2014 | South Africa | Neurosurgeons | 66 | Subitems | N/A | Changing practice behavior to try to minimize the risk of a lawsuit |

| 25 | Solaroglu | 2014 | Turkey | Neurosurgeons | 404 | Overall | Gender, working experience, types of hospital, and the geographic regions | Medical practices that help doctors avoid liability without providing any additional benefit to the patient |

| 26 | Bourne | 2015 | UK | Multiple specialties | 7926 | Subitems | Exposure to complaint, length of investigation, outcome of investigation, complaint source, and type of complaint | Broadly categorized into ‘hedging’ and ‘avoidance’. Hedging is when doctors are overcautious, leading to overprescribing, referring too many patients or over investigation. Avoidance includes not taking on complicated patients and avoiding certain procedures or more difficult cases |

| 27 | Motta | 2015 | Italy | Otolaryngology | 100 | Overall | Concern over potential medicolegal disputes, concern over variations in the doctor/patient relationship, and knowledge of insurance clauses | Defensive medicine is defined as the ordering of tests and procedures (positive defensive medicine) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine), primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 28 | Osti | 2015 | Austria | Multiple specialtiese | 193 | Overall | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate doctors from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 29 | Reisch | 2015 | USA | Breast pathologists | 252 | Overall | Age, gender, geographic region, medical skills training, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, working experience, workloads, and exposure to medical malpractice | A deviation from standard medical practice induced primarily by a threat of liability |

| 30 | Smith | 2015 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1026 | Overall | Working experience, reimbursement patterns, claims history, insurance coverage and cost, malpractice crisis level of the region, and patients with public insurance | An incentive to administer precautionary treatment with minimal expected medical benefit out of fear of litigation |

| 31 | Tanriverdi | 2015 | Turkey | Medical oncologists | 124 | Overall | Age, gender, academic occupation, working experience, type of hospital, and occupational status | Occasionally indulging unnecessary treatment requests to defend against lawsuits for medical errors and the use of unapproved medical applications |

| 32 | Abdel | 2016 | Sudan | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Overall | Working experience, professional certification, technical title, and type of hospital | A doctor’s deviation from the usual practice in order to reduce or prevent criticism and/or complaints by patients or their relatives |

| 33 | Panella | 2016 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, working experience, workload, and perception of being a ‘second victim’i | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 34 | Silberstein | 2016 | Israel | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 78 | Overall | Gender, working experience, managerial job, exposure to medicolegal literature, and requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine | Medical practices carried out primarily to avoid malpractice liability rather than to benefit the patient |

| 35 | Smith | 2016 | Canada | Neurosurgeons | 75 | Subitems | N/A | A deviation from regular medical practice because of medicolegal fears |

| 36 | Yan | 2016 | Cross-nationf | Neurosurgeons | 1142 | Overall | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care or avoiding high-risk situations out of fear of litigation |

| 37 | Din | 2017 | USA | Spine neurosurgery | 1024 | Overall | Malpractice crisis level of the region, premium burden, patients with public insurance, and exposure to malpractice claims | The provision of services beyond what is needed to improve patient outcomes (assurance behavior) and the evasion of high-risk procedures (avoidance behavior) to either deter litigation or substantiate clinical decision-making in the court |

| 38 | Olcay | 2017 | Turkey | Cardiologists | 253 | Overall | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Establishing diagnoses that would not alter patient care and performing unnecessary testing and treatments |

| 39 | Panella | 2017 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Exposure to malpractice claims, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of a request for compensation, fear of negative publicity, ineffective physician–patient relationship, insurance coverage, hospital support for liability issues, and public and mass media attention | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 40 | Ramírez-Alcántara | 2017 | Turkey | General practitioners | 87 | Overall | Work shifts | Application of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the aim of properly diagnosing and treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 41 | Reuveni | 2017 | Israel | Psychiatrists | 213 | Subitems | N/A | Medical actions that deviate from sound medical practice, performed primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability or to provide legal protection in the case of a malpractice lawsuit |

| 42 | Vandersteegen | 2017 | Belgium | Multiple specialties | 508 | Overall | Age, gender, region, working experience, insurance premium evolution, incitement by fund for medical accidents, consequences of medical lawsuit, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | The avoidance of certain high-risk procedures or patients or the ordering of procedures, tests, or visits, primarily (but not solely) due to the threat of medical liability |

| 43 | Yan | 2017 | Netherlands | Neurosurgeons | 45 | Subitems | N/A | A departure from standard medical practices out of fear of litigation |

| 44 | Tebano | 2018 | Cross-nationg | Antibiotic stewards | 830 | Subitems | Specialty, geographic regions, age, type of employment (contract or permanent), and fear of medical-legal litigation | When physicians perceive litigation as a threat, they may adopt defensive behaviors as a way to reduce the chances of litigation or to ensure a form of defense in the case of malpractice claims |

| 45 | Titus | 2018 | USA | Melanoma pathologists | 207 | Subitems | N/A | Behaviors that are intended to reduce exposure to malpractice litigation but may not clinically benefit the patient |

| 46 | Zhu | 2018 | China | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 1486 | Overall | Gender, level of hospital, education, specialty, exposure to medical dispute, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, consequences of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | The alterations of modes of medical practice, induced by the threat of liability, for the principal purposes of forestalling lawsuits by patients as well as providing good legal defense in the event that such lawsuits are instituted |

| 47 | Delice | 2019 | Turkey | Emergency medical specialists | 321 | Overall | N/A | Physicians requesting additional tests in the absence of indications or else avoiding high-risk patient groups in which adverse outcomes may occur during diagnosis and treatment |

| 48 | Ionescu | 2019 | Romania | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 73 | Overall | Working experience | A cesarean delivery recommended by the doctor in the absence of any clear medical indication that such a delivery method is needed to avoid possible litigation or a possible accusation of malpractice (defensive cesarean section) |

| 49 | Renkema | 2019 | Netherlands | Multiple specialties | 214 | Subitems | Age, specialty, technical title, attitude toward justified/unjustified litigation, and perceived patient pressure | The ordering of extra tests or procedures (assurance behavior) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (avoidance behavior), primarily to reduce the risk of being held liable for malpractice |

| 50 | Qiao | 2019 | China | Multiple specialties | 226 | Overall | N/A | Prescribe procedures or diagnostic tests or drugs that are clinically unnecessary to avoid possible troubles (such as lawsuits and disputes) |

| 51 | Garg | 2020 | India | Neurosurgeons | 214 | Subitems | Working experience and practice type | Clinical and operative practices to prevent medicolegal issues |

| 52 | Borgan | 2020 | USA | Internal medicine residents | 49 | Subitems | N/A | The deviation from routine medical care in order to avoid or reduce the risk of real or perceived future legal consequences |

| 53 | Calikoglu | 2020 | Turkey | Surgeons | 190 | Overall | Gender, academic occupation, specialty, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Medical behaviors that avoid physician liability without providing increased benefits to the patient |

| 54 | Gadjradj | 2020 | Cross-nation | Neurosurgeons | 490 | Subitems | N/A | Perform unnecessary, additional therapeutic or diagnostic interventions that do not improve the medical condition of the patient (positive defensive medicine), or it may cause physicians to refer or refuse difficult cases (negative defensive medicine) |

| 55 | Abbass | 2021 | Egypt | Multiple specialties | 261 | Subitems | Gender and specialty | The overuse of the resources such as ordering unnecessary investigations, giving treatment, or performing procedures aiming at doctors’ self-protection against claims rather than for the patient best interest |

| 56 | Fineschi | 2021 | Italy | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 168 | Subitems | N/A | The practice of recommending a diagnostic test or medical treatment (positive defensive medicine) or avoidance of risky patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine) that serves the function to protect physicians against patients’ claims |

| 57 | Kolcu | 2021 | Turkey | General practitioners | 196 | Subitems | N/A | The cost-increasing, defensive, or avoidance behavior displayed by physicians in healthcare delivery in order to protect themselves from legal problems |

| 58 | Perea-Pérez | 2021 | Spain | Emergency physicians | 1449 | Subitems | N/A | The making of clinical decisions that, while being explainable, prioritize the doctor’s legal security over other healthcare considerations |

| 59 | Rudey | 2021 | Brazil | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 403 | Overall | Gender, working experience, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | A practice wherein a healthcare professional makes decisions out of fear of litigation and not for the benefit of the patients |

| 60 | Ekici | 2021 | Turkey | Oral and maxillofacial surgeons | 109 | Subitems | N/A | A medical behavior that avoids medical responsibility without offering the patient greater benefits |

| 61 | Tumelty | 2021 | Ireland | Surgeons | 157 | Subitems | N/A | Behaviors engaged in by physicians for the purposes of averting the threat of medical negligence litigation and/or complaints |

| 62 | Zaed | 2021 | Italy | Neurosurgeons | 64 | Subitems | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care to minimize litigation exposure (positive defensive medicine) or the practice of avoiding more risky, albeit important, treatment measures to avoid litigation exposure (negative defensive medicine) |

| 63 | Vizcaino-Rakosnik | 2022 | Spain | Unclear | 282 | Overall | N/A | Made changes in their clinical practice because of the experience of being claimed |

| 64 | Shehata | 2022 | Egypt | Anesthesiologists | 177 | Subitems | Age, gender, marital status, technical title, professional certification, practice location, and type of employment (contract or permanent) | Defensive medicine occurs when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits or avoid high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily or solely) to reduce their exposure to malpractice liability |

General surgeons, radiologists, emergency physicians, orthopedic surgeons, obstetrician/gynecologists, and neurosurgeons.

Primary care, surgical specialists, nonsurgical specialists, and other specialists.

Obstetricians, gynecologists, physicians, surgeons, anesthetists, psychiatrists, pathologists, radiologists, pediatricians, accident, and emergency specialists.

Pediatricians, internists, obstetricians and gynecologists, orthopedic surgeons, family medicine practitioners, general surgeons, cardiologists, and neurosurgeons.

Orthopaedic surgeons, trauma surgeons, and radiologists.

USA, Canada, and South Africa.

Including 74 countries.

N/A: not applicable.

Second victim: a healthcare provider involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, medical error, and/or a patient related injury, who becomes victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event.

| No . | First author . | Publication year . | Location . | Specialty . | Sample size . | Outcome dimension . | Influencing factorsh . | Definition of defensive medicine . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Summerton | 2000 | UK | General practitioners | 339 | Subitems | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 2 | Symon | 2000 | UK | Midwives and obstetrician | 211 | Overall | N/A | Personally changed practice as a result of the fear of litigation |

| 3 | Passmore | 2002 | UK | Psychiatrists | 95 | Overall | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 4 | Toker | 2004 | Israel | Ear, nose, and throat physicians | 194 | Subitems | N/A | A physician’s deviation from what is considered to be good practice to prevent complaints from patients or their families |

| 5 | Studdert | 2005 | USA | Multiple specialtiesa | 824 | Subitems | Gender, insurance coverage, premium burden, experience of being dropped by insurer practice type, and working experience | Physicians alter their clinical behavior because of the threat of malpractice liability |

| 6 | Sánchez-González | 2005 | Mexico | Unclear | 613 | Overall | N/A | Application of treatments, tests, and procedures with the explicit main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies, over and above the diagnosis or treatment of the patient |

| 7 | Hiyama | 2006 | Japan | Gastroenterologists | 131 | Overall | Working experience and practice type | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by the threat of liability claims |

| 8 | Krawitz | 2006 | New Zealand | Clinician | 26 | Overall | Public and mass media attention, Ministry of Health, requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine, and politicians and policy | Taken a treatment approach not likely to be in the client’s best interest but protects from medicolegal repercussions |

| 9 | Mullen | 2008 | New Zealand | Psychiatrists | 86 | Subitems | N/A | Additional effort, of marginal clinical utility, is made to avoid complaint or legal liability |

| 10 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners | 307 | Overall | Fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel order unnecessary treatments (positive defensive medicine) or avoid high-risk procedures or patients (negative defensive medicine) with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to damages claims |

| 11 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners, anesthetists, and surgeons | 102 | Overall | Age, fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel effect unnecessary treatments or avoid high-risk procedures, with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to malpractice litigation |

| 12 | Bishop | 2010 | USA | Multiple specialtiesb | 1231 | Overall | Gender, practice location (rural or urban), practice type, source of income, and hour-long patient care | Physicians order more tests and procedures than patients need to protect themselves from malpractice suits |

| 13 | Nash | 2010 | Australia | Multiple specialtiesb | 2999 | Subitems | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Perceived change in practice behavior due to concerns about medicolegal negligence claims and complaints |

| 14 | Anderson | 2011 | USA | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 241 | Subitems | Age, career satisfaction, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, insurance premium evolution, and malpractice crisis level of the region | Changes in practices due to malpractice concern |

| 15 | Leary | 2011 | USA | Residents (surgical versus medical) | 76 | Overall | N/A | A deviation from sound medical practice that physicians engage in primarily because they perceive a threat of liability |

| 16 | Asher | 2012 | Israel | Multiple specialtiesc | 877 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, exposure to complaint, practice type, managerial job, career satisfaction, and owning private malpractice insurance | Ordering of tests, procedures, and visits or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures, primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 17 | Nahed | 2012 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1028 | Subitems | N/A | Perception changes actions solely to mitigate liability risk |

| 18 | Manish | 2012 | USA | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 1214 | Subitems | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate physicians from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 19 | Asher | 2013 | Israel | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Subitems | Age, gender, concern over potential medicolegal litigation, practice location (rural or urban), and professional status | Medical actions, performed mainly in order to refrain from being sued rather than actually aiding the patient |

| 20 | Ortashi | 2013 | UK | Unclear | 204 | Overall | Age, gender, technical title, and specialty | A doctor’s deviation from their usual behavior or that considered good practice, to reduce or prevent complaints or criticism by patients or their families |

| 21 | Prieto-Miranda | 2013 | Mexico | Multiple specialtiesd | 246 | Overall | Age, gender, work shifts, specialty, professional certification, working experience, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Aapplication of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the objective of diagnosing and adequately treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 22 | Jingwei | 2014 | China | Unclear | 504 | Overall | Gender, working experience, education, specialty, technical title, monthly payroll income, workload, type of hospital, and exposure to medical dispute | Medical practice based on fear of legal liability rather than on patients’ best interests |

| 23 | Moosazadeh | 2014 | Iran | General practitioners | 423 | Subitems | Age, gender, working experience, insurance coverage, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Every therapeutic test or method, whose primary aim is to protect the physician against the threat of being accused of making a forensic medicine mistake or of being sued for medical mistakes |

| 24 | Roytowski | 2014 | South Africa | Neurosurgeons | 66 | Subitems | N/A | Changing practice behavior to try to minimize the risk of a lawsuit |

| 25 | Solaroglu | 2014 | Turkey | Neurosurgeons | 404 | Overall | Gender, working experience, types of hospital, and the geographic regions | Medical practices that help doctors avoid liability without providing any additional benefit to the patient |

| 26 | Bourne | 2015 | UK | Multiple specialties | 7926 | Subitems | Exposure to complaint, length of investigation, outcome of investigation, complaint source, and type of complaint | Broadly categorized into ‘hedging’ and ‘avoidance’. Hedging is when doctors are overcautious, leading to overprescribing, referring too many patients or over investigation. Avoidance includes not taking on complicated patients and avoiding certain procedures or more difficult cases |

| 27 | Motta | 2015 | Italy | Otolaryngology | 100 | Overall | Concern over potential medicolegal disputes, concern over variations in the doctor/patient relationship, and knowledge of insurance clauses | Defensive medicine is defined as the ordering of tests and procedures (positive defensive medicine) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine), primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 28 | Osti | 2015 | Austria | Multiple specialtiese | 193 | Overall | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate doctors from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 29 | Reisch | 2015 | USA | Breast pathologists | 252 | Overall | Age, gender, geographic region, medical skills training, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, working experience, workloads, and exposure to medical malpractice | A deviation from standard medical practice induced primarily by a threat of liability |

| 30 | Smith | 2015 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1026 | Overall | Working experience, reimbursement patterns, claims history, insurance coverage and cost, malpractice crisis level of the region, and patients with public insurance | An incentive to administer precautionary treatment with minimal expected medical benefit out of fear of litigation |

| 31 | Tanriverdi | 2015 | Turkey | Medical oncologists | 124 | Overall | Age, gender, academic occupation, working experience, type of hospital, and occupational status | Occasionally indulging unnecessary treatment requests to defend against lawsuits for medical errors and the use of unapproved medical applications |

| 32 | Abdel | 2016 | Sudan | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Overall | Working experience, professional certification, technical title, and type of hospital | A doctor’s deviation from the usual practice in order to reduce or prevent criticism and/or complaints by patients or their relatives |

| 33 | Panella | 2016 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, working experience, workload, and perception of being a ‘second victim’i | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 34 | Silberstein | 2016 | Israel | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 78 | Overall | Gender, working experience, managerial job, exposure to medicolegal literature, and requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine | Medical practices carried out primarily to avoid malpractice liability rather than to benefit the patient |

| 35 | Smith | 2016 | Canada | Neurosurgeons | 75 | Subitems | N/A | A deviation from regular medical practice because of medicolegal fears |

| 36 | Yan | 2016 | Cross-nationf | Neurosurgeons | 1142 | Overall | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care or avoiding high-risk situations out of fear of litigation |

| 37 | Din | 2017 | USA | Spine neurosurgery | 1024 | Overall | Malpractice crisis level of the region, premium burden, patients with public insurance, and exposure to malpractice claims | The provision of services beyond what is needed to improve patient outcomes (assurance behavior) and the evasion of high-risk procedures (avoidance behavior) to either deter litigation or substantiate clinical decision-making in the court |

| 38 | Olcay | 2017 | Turkey | Cardiologists | 253 | Overall | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Establishing diagnoses that would not alter patient care and performing unnecessary testing and treatments |

| 39 | Panella | 2017 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Exposure to malpractice claims, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of a request for compensation, fear of negative publicity, ineffective physician–patient relationship, insurance coverage, hospital support for liability issues, and public and mass media attention | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 40 | Ramírez-Alcántara | 2017 | Turkey | General practitioners | 87 | Overall | Work shifts | Application of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the aim of properly diagnosing and treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 41 | Reuveni | 2017 | Israel | Psychiatrists | 213 | Subitems | N/A | Medical actions that deviate from sound medical practice, performed primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability or to provide legal protection in the case of a malpractice lawsuit |

| 42 | Vandersteegen | 2017 | Belgium | Multiple specialties | 508 | Overall | Age, gender, region, working experience, insurance premium evolution, incitement by fund for medical accidents, consequences of medical lawsuit, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | The avoidance of certain high-risk procedures or patients or the ordering of procedures, tests, or visits, primarily (but not solely) due to the threat of medical liability |

| 43 | Yan | 2017 | Netherlands | Neurosurgeons | 45 | Subitems | N/A | A departure from standard medical practices out of fear of litigation |

| 44 | Tebano | 2018 | Cross-nationg | Antibiotic stewards | 830 | Subitems | Specialty, geographic regions, age, type of employment (contract or permanent), and fear of medical-legal litigation | When physicians perceive litigation as a threat, they may adopt defensive behaviors as a way to reduce the chances of litigation or to ensure a form of defense in the case of malpractice claims |

| 45 | Titus | 2018 | USA | Melanoma pathologists | 207 | Subitems | N/A | Behaviors that are intended to reduce exposure to malpractice litigation but may not clinically benefit the patient |

| 46 | Zhu | 2018 | China | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 1486 | Overall | Gender, level of hospital, education, specialty, exposure to medical dispute, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, consequences of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | The alterations of modes of medical practice, induced by the threat of liability, for the principal purposes of forestalling lawsuits by patients as well as providing good legal defense in the event that such lawsuits are instituted |

| 47 | Delice | 2019 | Turkey | Emergency medical specialists | 321 | Overall | N/A | Physicians requesting additional tests in the absence of indications or else avoiding high-risk patient groups in which adverse outcomes may occur during diagnosis and treatment |

| 48 | Ionescu | 2019 | Romania | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 73 | Overall | Working experience | A cesarean delivery recommended by the doctor in the absence of any clear medical indication that such a delivery method is needed to avoid possible litigation or a possible accusation of malpractice (defensive cesarean section) |

| 49 | Renkema | 2019 | Netherlands | Multiple specialties | 214 | Subitems | Age, specialty, technical title, attitude toward justified/unjustified litigation, and perceived patient pressure | The ordering of extra tests or procedures (assurance behavior) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (avoidance behavior), primarily to reduce the risk of being held liable for malpractice |

| 50 | Qiao | 2019 | China | Multiple specialties | 226 | Overall | N/A | Prescribe procedures or diagnostic tests or drugs that are clinically unnecessary to avoid possible troubles (such as lawsuits and disputes) |

| 51 | Garg | 2020 | India | Neurosurgeons | 214 | Subitems | Working experience and practice type | Clinical and operative practices to prevent medicolegal issues |

| 52 | Borgan | 2020 | USA | Internal medicine residents | 49 | Subitems | N/A | The deviation from routine medical care in order to avoid or reduce the risk of real or perceived future legal consequences |

| 53 | Calikoglu | 2020 | Turkey | Surgeons | 190 | Overall | Gender, academic occupation, specialty, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Medical behaviors that avoid physician liability without providing increased benefits to the patient |

| 54 | Gadjradj | 2020 | Cross-nation | Neurosurgeons | 490 | Subitems | N/A | Perform unnecessary, additional therapeutic or diagnostic interventions that do not improve the medical condition of the patient (positive defensive medicine), or it may cause physicians to refer or refuse difficult cases (negative defensive medicine) |

| 55 | Abbass | 2021 | Egypt | Multiple specialties | 261 | Subitems | Gender and specialty | The overuse of the resources such as ordering unnecessary investigations, giving treatment, or performing procedures aiming at doctors’ self-protection against claims rather than for the patient best interest |

| 56 | Fineschi | 2021 | Italy | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 168 | Subitems | N/A | The practice of recommending a diagnostic test or medical treatment (positive defensive medicine) or avoidance of risky patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine) that serves the function to protect physicians against patients’ claims |

| 57 | Kolcu | 2021 | Turkey | General practitioners | 196 | Subitems | N/A | The cost-increasing, defensive, or avoidance behavior displayed by physicians in healthcare delivery in order to protect themselves from legal problems |

| 58 | Perea-Pérez | 2021 | Spain | Emergency physicians | 1449 | Subitems | N/A | The making of clinical decisions that, while being explainable, prioritize the doctor’s legal security over other healthcare considerations |

| 59 | Rudey | 2021 | Brazil | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 403 | Overall | Gender, working experience, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | A practice wherein a healthcare professional makes decisions out of fear of litigation and not for the benefit of the patients |

| 60 | Ekici | 2021 | Turkey | Oral and maxillofacial surgeons | 109 | Subitems | N/A | A medical behavior that avoids medical responsibility without offering the patient greater benefits |

| 61 | Tumelty | 2021 | Ireland | Surgeons | 157 | Subitems | N/A | Behaviors engaged in by physicians for the purposes of averting the threat of medical negligence litigation and/or complaints |

| 62 | Zaed | 2021 | Italy | Neurosurgeons | 64 | Subitems | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care to minimize litigation exposure (positive defensive medicine) or the practice of avoiding more risky, albeit important, treatment measures to avoid litigation exposure (negative defensive medicine) |

| 63 | Vizcaino-Rakosnik | 2022 | Spain | Unclear | 282 | Overall | N/A | Made changes in their clinical practice because of the experience of being claimed |

| 64 | Shehata | 2022 | Egypt | Anesthesiologists | 177 | Subitems | Age, gender, marital status, technical title, professional certification, practice location, and type of employment (contract or permanent) | Defensive medicine occurs when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits or avoid high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily or solely) to reduce their exposure to malpractice liability |

| No . | First author . | Publication year . | Location . | Specialty . | Sample size . | Outcome dimension . | Influencing factorsh . | Definition of defensive medicine . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Summerton | 2000 | UK | General practitioners | 339 | Subitems | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 2 | Symon | 2000 | UK | Midwives and obstetrician | 211 | Overall | N/A | Personally changed practice as a result of the fear of litigation |

| 3 | Passmore | 2002 | UK | Psychiatrists | 95 | Overall | N/A | Ordering of treatments, tests, and procedures for the purpose of protecting the doctor from criticism rather than diagnosing or treating the patient |

| 4 | Toker | 2004 | Israel | Ear, nose, and throat physicians | 194 | Subitems | N/A | A physician’s deviation from what is considered to be good practice to prevent complaints from patients or their families |

| 5 | Studdert | 2005 | USA | Multiple specialtiesa | 824 | Subitems | Gender, insurance coverage, premium burden, experience of being dropped by insurer practice type, and working experience | Physicians alter their clinical behavior because of the threat of malpractice liability |

| 6 | Sánchez-González | 2005 | Mexico | Unclear | 613 | Overall | N/A | Application of treatments, tests, and procedures with the explicit main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies, over and above the diagnosis or treatment of the patient |

| 7 | Hiyama | 2006 | Japan | Gastroenterologists | 131 | Overall | Working experience and practice type | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by the threat of liability claims |

| 8 | Krawitz | 2006 | New Zealand | Clinician | 26 | Overall | Public and mass media attention, Ministry of Health, requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine, and politicians and policy | Taken a treatment approach not likely to be in the client’s best interest but protects from medicolegal repercussions |

| 9 | Mullen | 2008 | New Zealand | Psychiatrists | 86 | Subitems | N/A | Additional effort, of marginal clinical utility, is made to avoid complaint or legal liability |

| 10 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners | 307 | Overall | Fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel order unnecessary treatments (positive defensive medicine) or avoid high-risk procedures or patients (negative defensive medicine) with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to damages claims |

| 11 | Catino | 2009 | Italy | General practitioners, anesthetists, and surgeons | 102 | Overall | Age, fear of a request for compensation, fear of medical-legal litigation, fear of disciplinary sanctions, fear of negative publicity, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Healthcare personnel effect unnecessary treatments or avoid high-risk procedures, with the principle—though not exclusive—aim of reducing their exposure to malpractice litigation |

| 12 | Bishop | 2010 | USA | Multiple specialtiesb | 1231 | Overall | Gender, practice location (rural or urban), practice type, source of income, and hour-long patient care | Physicians order more tests and procedures than patients need to protect themselves from malpractice suits |

| 13 | Nash | 2010 | Australia | Multiple specialtiesb | 2999 | Subitems | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Perceived change in practice behavior due to concerns about medicolegal negligence claims and complaints |

| 14 | Anderson | 2011 | USA | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 241 | Subitems | Age, career satisfaction, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, insurance premium evolution, and malpractice crisis level of the region | Changes in practices due to malpractice concern |

| 15 | Leary | 2011 | USA | Residents (surgical versus medical) | 76 | Overall | N/A | A deviation from sound medical practice that physicians engage in primarily because they perceive a threat of liability |

| 16 | Asher | 2012 | Israel | Multiple specialtiesc | 877 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, exposure to complaint, practice type, managerial job, career satisfaction, and owning private malpractice insurance | Ordering of tests, procedures, and visits or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures, primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 17 | Nahed | 2012 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1028 | Subitems | N/A | Perception changes actions solely to mitigate liability risk |

| 18 | Manish | 2012 | USA | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 1214 | Subitems | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate physicians from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 19 | Asher | 2013 | Israel | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Subitems | Age, gender, concern over potential medicolegal litigation, practice location (rural or urban), and professional status | Medical actions, performed mainly in order to refrain from being sued rather than actually aiding the patient |

| 20 | Ortashi | 2013 | UK | Unclear | 204 | Overall | Age, gender, technical title, and specialty | A doctor’s deviation from their usual behavior or that considered good practice, to reduce or prevent complaints or criticism by patients or their families |

| 21 | Prieto-Miranda | 2013 | Mexico | Multiple specialtiesd | 246 | Overall | Age, gender, work shifts, specialty, professional certification, working experience, and previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Aapplication of treatments, performance of diagnostic tests and therapeutic procedures, more than with the objective of diagnosing and adequately treating the patient, with the main purpose of defending the doctor from criticism, in addition to having documentary evidence in the event of a lawsuit and avoiding controversies |

| 22 | Jingwei | 2014 | China | Unclear | 504 | Overall | Gender, working experience, education, specialty, technical title, monthly payroll income, workload, type of hospital, and exposure to medical dispute | Medical practice based on fear of legal liability rather than on patients’ best interests |

| 23 | Moosazadeh | 2014 | Iran | General practitioners | 423 | Subitems | Age, gender, working experience, insurance coverage, and previous experience of a colleague being subject to medical-legal litigation | Every therapeutic test or method, whose primary aim is to protect the physician against the threat of being accused of making a forensic medicine mistake or of being sued for medical mistakes |

| 24 | Roytowski | 2014 | South Africa | Neurosurgeons | 66 | Subitems | N/A | Changing practice behavior to try to minimize the risk of a lawsuit |

| 25 | Solaroglu | 2014 | Turkey | Neurosurgeons | 404 | Overall | Gender, working experience, types of hospital, and the geographic regions | Medical practices that help doctors avoid liability without providing any additional benefit to the patient |

| 26 | Bourne | 2015 | UK | Multiple specialties | 7926 | Subitems | Exposure to complaint, length of investigation, outcome of investigation, complaint source, and type of complaint | Broadly categorized into ‘hedging’ and ‘avoidance’. Hedging is when doctors are overcautious, leading to overprescribing, referring too many patients or over investigation. Avoidance includes not taking on complicated patients and avoiding certain procedures or more difficult cases |

| 27 | Motta | 2015 | Italy | Otolaryngology | 100 | Overall | Concern over potential medicolegal disputes, concern over variations in the doctor/patient relationship, and knowledge of insurance clauses | Defensive medicine is defined as the ordering of tests and procedures (positive defensive medicine) or the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures (negative defensive medicine), primarily to reduce exposure to malpractice liability |

| 28 | Osti | 2015 | Austria | Multiple specialtiese | 193 | Overall | N/A | Medical practices that may exonerate doctors from liability without significant benefit to patients |

| 29 | Reisch | 2015 | USA | Breast pathologists | 252 | Overall | Age, gender, geographic region, medical skills training, previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation, working experience, workloads, and exposure to medical malpractice | A deviation from standard medical practice induced primarily by a threat of liability |

| 30 | Smith | 2015 | USA | Neurosurgeons | 1026 | Overall | Working experience, reimbursement patterns, claims history, insurance coverage and cost, malpractice crisis level of the region, and patients with public insurance | An incentive to administer precautionary treatment with minimal expected medical benefit out of fear of litigation |

| 31 | Tanriverdi | 2015 | Turkey | Medical oncologists | 124 | Overall | Age, gender, academic occupation, working experience, type of hospital, and occupational status | Occasionally indulging unnecessary treatment requests to defend against lawsuits for medical errors and the use of unapproved medical applications |

| 32 | Abdel | 2016 | Sudan | Obstetrician/gynecologists | 117 | Overall | Working experience, professional certification, technical title, and type of hospital | A doctor’s deviation from the usual practice in order to reduce or prevent criticism and/or complaints by patients or their relatives |

| 33 | Panella | 2016 | Italy | Multiple specialties | 1313 | Overall | Age, gender, specialty, working experience, workload, and perception of being a ‘second victim’i | A deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily, but not solely, by the threat of liability claims |

| 34 | Silberstein | 2016 | Israel | Plastic and aesthetic surgeons | 78 | Overall | Gender, working experience, managerial job, exposure to medicolegal literature, and requests by superiors to practice defensive medicine | Medical practices carried out primarily to avoid malpractice liability rather than to benefit the patient |

| 35 | Smith | 2016 | Canada | Neurosurgeons | 75 | Subitems | N/A | A deviation from regular medical practice because of medicolegal fears |

| 36 | Yan | 2016 | Cross-nationf | Neurosurgeons | 1142 | Overall | N/A | The practice of prescribing unnecessary medical care or avoiding high-risk situations out of fear of litigation |

| 37 | Din | 2017 | USA | Spine neurosurgery | 1024 | Overall | Malpractice crisis level of the region, premium burden, patients with public insurance, and exposure to malpractice claims | The provision of services beyond what is needed to improve patient outcomes (assurance behavior) and the evasion of high-risk procedures (avoidance behavior) to either deter litigation or substantiate clinical decision-making in the court |

| 38 | Olcay | 2017 | Turkey | Cardiologists | 253 | Overall | Previous personal experience of medical-legal litigation | Establishing diagnoses that would not alter patient care and performing unnecessary testing and treatments |