-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jeffrey Braithwaite, Robyn Clay-Williams, Natalie Taylor, Hsuen P Ting, Teresa Winata, Gaston Arnolda, Rosa Sunol, Oliver Gröne, Cordula Wagner, Niek S Klazinga, Liam Donaldson, S Bruce Dowton, Bending the quality curve, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 32, Issue Supplement_1, January 2020, Pages 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzz102

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

With this paper, we initiate the Supplement on Deepening our Understanding of Quality in Australia (DUQuA). DUQuA is an at-scale, cross-sectional research programme examining the quality activities in 32 large hospitals across Australia. It is based on, with suitable modifications and extensions, the Deepening our Understanding of Quality improvement in Europe (DUQuE) research programme, also published as a Supplement in this Journal, in 2014. First, we briefly discuss key data about Australia, the health of its population and its health system. Then, to provide context for the work, we discuss previous activities on the quality of care and improvement leading up to the DUQuA studies. Next, we present a selection of key interventional studies and policy and institutional initiatives to date. Finally, we conclude by outlining, in brief, the aims and scope of the articles that follow in the Supplement. This first article acts as a framing vehicle for the DUQuA studies as a whole. Aggregated, the series of papers collectively attempts an answer to the questions: what is the relationship between quality strategies, both hospital-wide and at department level? and what are the relationships between the way care is organised, and the actual quality of care as delivered? Papers in the Supplement deal with a multiplicity of issues including: how the DUQuA investigators made progress over time, what the results mean in context, the scales designed or modified along the way for measuring the quality of care, methodological considerations and provision of lessons learnt for the benefit of future researchers.

Introduction

This article frames the studies that follow, which collectively form a report on the Deepening our Understanding of Quality in Australia (DUQuA) programme. The Supplement is an in-depth examination, across 12 articles, of a 5-year effort to examine the quality of care in 32 large hospitals, geographically spread over the Australian States and Territories. It follows the landmark Deepening our Understanding of Quality improvement in Europe (DUQuE) seven-country study. We begin with a summary profile of the Australian health system (Table 1) and then contextualise the 11 subsequent articles in the Supplement with a brief outline of our view of where the research on the quality of care sits at the moment.

| Australia | |

| Populationa | 25 203 198 |

| Indigenous populationb | 3.3% |

| Land massa | 7 692 024 km2 |

| GDP (per capita)a | US$ 62 765 |

| Urbanisationb | 71% live in cities |

| Australia’s health | |

| Average life expectancyb | 80.4 (males); 84.6 (females) born in 2016 |

| Number of birthsb | 309 000 per year (2015 data) |

| Leading cause of deathb | Coronary heart disease (males); dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (females) |

| Chronic conditionsb | 50% have at least 1/8 chronic conditions |

| Disabilityb | 18% of the population |

| Overweightb | 63% of adults are overweight or obese |

| Australia’s health system | |

| Hospitalsb | 701 public hospitals, 630 private hospitals (2015–2016) |

| Average Length of Stay (admitted patients)b | 5.7 days (public); 5.2 days (private) |

| Health expenditure, proportion of GDPc | 9.25% |

| Admitted patientsb | 6.3 million |

| Emergency Department presentations (2016–2017)b | 7.8 million |

| Australia | |

| Populationa | 25 203 198 |

| Indigenous populationb | 3.3% |

| Land massa | 7 692 024 km2 |

| GDP (per capita)a | US$ 62 765 |

| Urbanisationb | 71% live in cities |

| Australia’s health | |

| Average life expectancyb | 80.4 (males); 84.6 (females) born in 2016 |

| Number of birthsb | 309 000 per year (2015 data) |

| Leading cause of deathb | Coronary heart disease (males); dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (females) |

| Chronic conditionsb | 50% have at least 1/8 chronic conditions |

| Disabilityb | 18% of the population |

| Overweightb | 63% of adults are overweight or obese |

| Australia’s health system | |

| Hospitalsb | 701 public hospitals, 630 private hospitals (2015–2016) |

| Average Length of Stay (admitted patients)b | 5.7 days (public); 5.2 days (private) |

| Health expenditure, proportion of GDPc | 9.25% |

| Admitted patientsb | 6.3 million |

| Emergency Department presentations (2016–2017)b | 7.8 million |

aBased on 2019 data. World Population Review (2019) Australia Population, 2019. [Available at: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/australia-population/].

bAustralian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018) Australia’s health 2018: in brief. AIHW, Canberra, Australia. ISBN: 978-1-76054-377-8.

cBased on 2016 data. The World Bank (2019) Current health expenditure (% of GDP) [Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS].

| Australia | |

| Populationa | 25 203 198 |

| Indigenous populationb | 3.3% |

| Land massa | 7 692 024 km2 |

| GDP (per capita)a | US$ 62 765 |

| Urbanisationb | 71% live in cities |

| Australia’s health | |

| Average life expectancyb | 80.4 (males); 84.6 (females) born in 2016 |

| Number of birthsb | 309 000 per year (2015 data) |

| Leading cause of deathb | Coronary heart disease (males); dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (females) |

| Chronic conditionsb | 50% have at least 1/8 chronic conditions |

| Disabilityb | 18% of the population |

| Overweightb | 63% of adults are overweight or obese |

| Australia’s health system | |

| Hospitalsb | 701 public hospitals, 630 private hospitals (2015–2016) |

| Average Length of Stay (admitted patients)b | 5.7 days (public); 5.2 days (private) |

| Health expenditure, proportion of GDPc | 9.25% |

| Admitted patientsb | 6.3 million |

| Emergency Department presentations (2016–2017)b | 7.8 million |

| Australia | |

| Populationa | 25 203 198 |

| Indigenous populationb | 3.3% |

| Land massa | 7 692 024 km2 |

| GDP (per capita)a | US$ 62 765 |

| Urbanisationb | 71% live in cities |

| Australia’s health | |

| Average life expectancyb | 80.4 (males); 84.6 (females) born in 2016 |

| Number of birthsb | 309 000 per year (2015 data) |

| Leading cause of deathb | Coronary heart disease (males); dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (females) |

| Chronic conditionsb | 50% have at least 1/8 chronic conditions |

| Disabilityb | 18% of the population |

| Overweightb | 63% of adults are overweight or obese |

| Australia’s health system | |

| Hospitalsb | 701 public hospitals, 630 private hospitals (2015–2016) |

| Average Length of Stay (admitted patients)b | 5.7 days (public); 5.2 days (private) |

| Health expenditure, proportion of GDPc | 9.25% |

| Admitted patientsb | 6.3 million |

| Emergency Department presentations (2016–2017)b | 7.8 million |

aBased on 2019 data. World Population Review (2019) Australia Population, 2019. [Available at: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/australia-population/].

bAustralian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018) Australia’s health 2018: in brief. AIHW, Canberra, Australia. ISBN: 978-1-76054-377-8.

cBased on 2016 data. The World Bank (2019) Current health expenditure (% of GDP) [Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS].

Australia is a relatively wealthy country with a well-funded and organised health system. About two-thirds of the care provided is publicly funded. Some 9.25% of gross domestic product (GDP) is spent on healthcare, and while the population is healthy with internationally benchmarked above life expectancy, it is ageing and there are patients with chronic conditions, disabilities and obesity. The leading causes of death are coronary heart disease in males and dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in females.

The arc of improvement

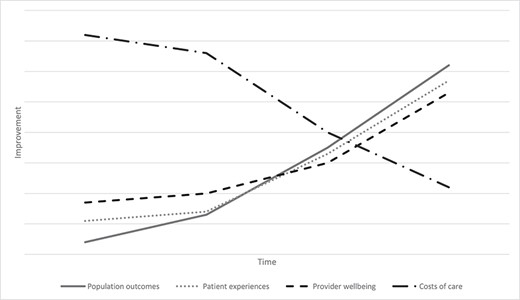

Internationally as well as in Australia, clinicians, their patients and those accountable for healthcare delivery want to see the curve of care arc toward improvement. A healthy healthcare system contributes better outcomes for the population it serves and gives patients enhanced experiences. Architects of well-designed health systems will also preside over the well-being of staff who provide care and seek to reduce costs wherever possible. This ideal has been termed the quadruple aim [1]. The premise is that all four goals can be achieved simultaneously. The first three take care on an improvement gradient, while the cost curve bends downwards (Figure 1) [2].

Bending quality and cost along an improvement gradient. Source: Authors’ conceptualisation, hypothetical data.

What needs to happen for this overarching goal of systems improvement along multiple dimensions to be realised? There have been many responses. Donaldson [3] evocatively contended that we need for healthcare to become ‘an organisation with a memory’: to have a better handle on learning from past failures and adverse events. Berwick [4] argued that we should forge a new, more moral epoch which he labelled Era 3: one predicated on better cultures, interprofessional working and commitment to openness and improvement, transforming from Era 1 (the age of professional dominance) and Era 2 (the age of accountability, scrutiny, bureaucracy and measurement). Other thought leaders are building a multi-faceted evidentiary model for getting what we know into routine practice, which has come to be called implementation science [5–7]. In implementation science, emphasis is shifting from generalisable interventions towards the importance of context [8]. Hollnagel, Braithwaite and colleagues, taking a complex systems approach [9], see that much effort to date has centred on trying to stamp out harm after the event, which has been summarised in the motif ‘Safety-I’. They have promoted a more proactive approach to quality and safety, bringing into sharper focus how everyday performance succeeds more often than it fails (labelled ‘Safety-II’), and recognising that human variability can be an important contributor to success in complex systems. For them, the key task then shifts to encouraging health systems to be more resilient, by learning from the variability of daily common practice—often described simply as how things go right—and figuring out ways to support, augment or encourage how people succeed.

Progress to date

Despite these attractive ideas and frameworks for change, progress in the quality of care has not followed the curves in Figure 1 for most system-level improvement initiatives. Furthermore, the shape of the healthcare cost curve has been pointing upwards, not downwards, for decades. In particular, large-scale change has proven infuriatingly difficult to orchestrate [10]. In one notable example of the lack of improvement despite multi-pronged initiatives, Landrigan and colleagues [11] reported a study of the rates of harm in 10 hospitals in North Carolina, USA, between 2002 and 2007, which had participated extensively in local and national improvement campaigns (Figure 2). Harm remained static over the 6-year period despite these endeavours.

![Rates of all harms, preventable harms and high-severity harms per 1000 patient-days, identified by internal and external reviewers in 10 North Carolina hospitals, 2002–2007. Source: Landrigan et al. [11].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/intqhc/32/Supplement_1/10.1093_intqhc_mzz102/3/m_mzz102f2.jpeg?Expires=1748104592&Signature=v-ztcSCiwnJ4i7OyLJj9Dtl7QqRJh9Ep8nQnn~Qd~lwpMR2wtgXoLU02jyS4lZISdIhLVvvt9p49Wc3Nf39gicxXwBPV84psKQNUmgkOAwXc7-de-av7P13~0jEryhsiYWeiRl7DnjguETtVAej90D~6YyHbwBemmmR~CbKmi~V~GuBNSv-KhArAMU5I6HEEXKMV-i0qboaaL2uWvhbFnMyAMokbwQsgHLNF4yHXTigklSskDvXQqpKM-WPdDCbVWHjnzWd6FRmjYuKcmQfeeKLTdxfAXbDbxxRKLh7ZIaNA9dnk8ZU5YJ1b~pd1z1b6E4Ld-YSoY-l0XH-hOCsJVw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Rates of all harms, preventable harms and high-severity harms per 1000 patient-days, identified by internal and external reviewers in 10 North Carolina hospitals, 2002–2007. Source: Landrigan et al. [11].

In another system-wide initiative, this time in the UK, Benning and Lilford led an evaluation of a concerted effort to improve care for patients (The Health Foundation Safer Patients Initiative) in a group of intervention and control hospitals [12]. The results of the improvement efforts were not significantly different between the two groups (Figures 3 and 4). The figures show change in Clostridioides difficile and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the control and intervention hospitals; both groups fluctuated over the 8-year period, but at the same rate. Therefore, the net effect of the intervention group was no additional gains in performance.

![Source: Benning et al. [12].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/intqhc/32/Supplement_1/10.1093_intqhc_mzz102/3/m_mzz102f3.jpeg?Expires=1748104592&Signature=Z0vi9BjAp6XuE1O6GYnVbN7VPioEClBBq7UCKnAk98Pl8DD7BQqUJsVSqRbUbmyPYmCrwuRTwHoJ5i2CxtHZe3I29cCErvNrFPVjqZruzKnqChVyaX-U7seRy987Z2gjFhEaye7tWlDMP0BVzb8ilKKraS6WPzTZMoL-rnl6N1VadQC07HFDWEaQY0u7rvOndB6x2PS61bU8Qi7eXEhA4EoQPTftDXQIUMHY398f08riPRxJoDsbsqHYPpLg1KcaJo~yPq0Ia0AaC82y6CTN8SwHF~iVk844-VoSqjJyGXFbMGB0K4ngmw1mwFpjLvSLB78uE8FSDIgHS4xo~feDKw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Rate of C. difficile, control and intervention hospitals, UK Safer Patients Initiative, 2004–2011

![Source: Benning et al. [12].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/intqhc/32/Supplement_1/10.1093_intqhc_mzz102/3/m_mzz102f4.jpeg?Expires=1748104592&Signature=39Vs-gQW--XqI5J7KTGGiy8QKZ5cSieLSZnsxCUDhSePgIC0geO3OwO7yb--LRZ7Xw3pw10698WhNiriEfldSc-mZ17~A70e1outW6BzOYTiUVtX82ofLn2naHIcEt4-q69W~Aw8FZ03cGrMAxSHvFvQ5ogY43KdDGW1M1B3bCAOzb4Heu6aTrZimq4ji2wakYRsTZ3YIUVDCyfTJwIZ-MdpAYRNW-z1T5FfW2GwqFT3LittQAI8rkdOrn4BNf3nV9RKIgHdvXu70gQMJjDzGPIOnZA4newhG-JSMLgyKmMDz5h8NoLZTU~1HngbtBfbIF~ozJscglV-jeaelL6ydg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Rate of MRSA, control and intervention hospitals, UK Safer Patients Initiative, 2004–2011

Whether or not the advocates of safer, higher quality care focus in the future on reducing harm or doing more things right, or both, they will need to base their endeavours on at least two strategies. One is designing and implementing interventions to improve the quality of care, which have greater success than the Landrigan et al. [11] and Benning et al. [12] studies. The other is making meaningful and accurate measurement of that quality so that progress can be tracked over time. On interventions, there has been much resourcefulness exercised to design theoretical and practical projects by which care quality can be enhanced. Some initiatives have made gains, but these have often been context-dependent; from a litany of examples, prominent under the Safety-I banner is incident reporting systems, bundles to reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections, hand hygiene campaigns, root cause analyses, checklists, and computerised alerts and reminders. In one celebrated example in The Netherlands, adverse events were reduced by 30% across the country [13]. The Quality and Safety in Europe by Research study, another pan-European program of work, conducted in a similar time-frame to DUQuE, looked at healthcare quality practices and policies in five European countries [14, 15]. The study focused on macro-, meso- and micro-level relationships of care, including conducting longitudinal case studies in hospitals via 389 interviews with healthcare practitioners and 803 hours of observations. Safety-II initiatives include tools for understanding how care frequently goes right, looking to support the ability of systems to perform well under varying conditions. The Resilience Assessment Grid is one of these tools, identifying which efforts to improve in terms of four potentials: to respond, to monitor, to learn and to anticipate [16]. The Functional Resonance Analysis Method is another, which enables performance variability—a naturally recurring property of activities in complex systems—to be modelled and understood [17]. This systems view will become important as we traverse the articles that follow in this Supplement.

Policy and institutional responses

Outside the research domain, at the macro-level of systems, policymakers have tried to regulate or guide clinicians’ behaviours on the front lines of care such that practices are safe, and care is of high quality. But it is true to say that top-down policy-designed mandates, prescriptions or encouragement have also not created the progress we would like them to have made [18–20]. Meso-level management has also struggled at the district, hospital and community levels to embrace, adopt or take up—or otherwise reinforce—policymakers’ prescriptions or researchers’ findings. Although many clinicians on the front lines have become accepting in principle over the last two decades of the quality improvement agenda, they have often exercised autonomy over their activities rather than simply be compliant with the multiplicity of rules, regulations, policies and procedures that have been enacted [21]. Many have also been too busy providing direct care to embrace improvement. Some clinicians have argued that quality improvement has become more bureaucratic, burdensome and time-consuming over time.

Among varied responses, many health systems have encouraged clinicians to take up managerial roles [22]. And consumers have entered the field of quality improvement more recently, becoming increasingly vocal and activated, and have claimed the right to be more than just an input to care decisions, but an active participant in the quality of care that is delivered to them—the ‘co-creators’ rather than ‘passive recipients’ of care [23].

All-in-all, despite increasing interest from all these stakeholders over two and a half decades, progress has been painfully slow. One missing piece of the jigsaw is to understand how quality is enacted on the ground in acute settings across-the-board, and for this, we need to dig deeper.

The present research agenda

To this end, articles reported in this Supplement have been configured as a series of studies under the DUQuA programme of research [24] funded by the Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council. These observational studies measure the quality of care in a sample of large Australian hospitals, cross-sectionally. That said that the program of work included an action-research strategy to provide benchmarked feedback reports to each of the 32 study hospitals (article 10) [25], designed to stimulate targeted internal discussions based on hospital-specific findings and provide a platform for improvement.

In terms of its pedigree, DUQuA follows, with appropriate modifications to the research design, earlier results reported in this Journal in 2014 of the DUQuE programme of research funded by the European Union’s 7th Research Framework Programme [26, 27]. Methodologically, while the DUQuA studies are based on the original DUQuE design, they depart from that template in a number of important ways. There are multiple reasons for these departures, including that methods have advanced, localised modifications were needed and the DUQuA research team added questions along the way. Additionally, DUQuA took into account aspects of the Australian health system and developed and validated scales for those who might need rigorous measurement tools in the future. DUQuE studies were primarily quantitative. DUQuA, too, is quantitative but also includes qualitative studies—for example, on benchmarking and surveying of hospitals. We acknowledge that alternative methodological approaches may offer other advantages and be helpful in disentangling the complex relationships between organisations, quality and patient outcomes.

The DUQuA studies in outline

Across the pages of this Supplement, we will see how the investigators examined two broad questions that the DUQuA team have been grappling with for the last 5 years. The first is: what is the relationship between strategies to manage the quality of care at the organisational and departmental levels in hospitals? The second is: what are the relationships between the way care is organised, and the actual quality of care delivered to patients?

In the article immediately following this one (article 2) [28], the DUQuA investigators take an overarching look at the answers to these questions. The next four contributions [29–32] trace how the project made progress in understanding organisational- and departmental-level quality factors, outcomes and cultures of care. article 3 [29] presents the scales for studying organisational- and department-level quality; article 4 [30] presents results on the extent to which organisation-level quality management systems influence department-level quality; article 5 [31] examines the relationships between the key variables: quality management systems, safety culture and leadership, and patient outcomes in Emergency Departments; and article 6 [32] looks at how we refined and validated a questionnaire scale to examine clinician safety culture and leadership. article 7 [33] changes the focus, examining clinician factors, and article 8 [34], patient factors. The next three articles [25, 35–36] look at methodological issues (article 9) [35], benchmarking of results for the benefits of participating hospitals (article 10) [25] and the use of external surveyors to assess care quality (article 11) [36]. Finally, article 12 [37] concludes the Supplement’s work, reflects on the lessons learnt and considers what should happen next as a result of this work.

Conclusion

By way of summarising, and setting up the rest of the Supplement: progress in shifting the quality curves along multiple dimensions in the right direction has been slower than the community wants and patients deserve. Large-scale studies with some celebrated examples [13] have not made the much-anticipated gains. Stakeholders embedded in healthcare (policymakers, managers, clinicians, associated staff and patients) have been active in contributing to the quality enterprise but they, too, desire more improvement—and at a faster pace. Among multiple changes taking place, Safety-II has offered an alternative perspective, clinicians are not always enjoined in the quality enterprise, patients are more involved than in past eras and care is becoming more complex.

Against this backdrop of challenge and change, it is timely to peer inside the quality black box and to look at one country’s attempts to bend the curve in two of four of the quadruple aims: population outcomes for groups of acute patients, and patient experiences, in this case by making a cross-sectional assessment of the care delivered by 32 of Australia’s largest hospitals. It is to this task that we now turn.

Contributors

The DUQuA research team consists of experienced researchers, clinicians, biostatisticians, and project managers with expertise in health services research, survey design, and validation, large-scale research and project management, sophisticated statistical analysis, quality improvement and assessment, accreditation, clinical indicators, policy and patient experience. JB conceived the idea to embrace DUQuE for Australia, led the research grant to fund the project, chairs the steering committee, and led the development of the manuscript. NT and RCW co-led the detailed study design, managed the project across time, and contributed to the development of the manuscript. HPT and GA provided statistical expertise for the study design and developed the analysis plan for the manuscript. TW contributed to the logistics of project management, the refinement of measures, and the development of the manuscript. Over the years, CW, NSK, LD and SBD provided advice, expertise and encouragement.

Acknowledgements

Members of the original DUQuE team (Oliver Gröne, Rosa Suñol) provided extensive input and advice in the initial stages of the project, supporting design modifications from DUQuE and the planned DUQuA study approach. Dr Annette Pantle provided expert advice on revision and development of DUQuA measures, and Professor Sandy Middleton, Associate Professor Dominique Cadillac, Kelvin Hill, Dr Carmel Crock, and Professor Jacqueline Close provided input into the development of our AMI, hip fracture and stroke clinical process indicator lists. Nicole Mealing and Victoria Pye provided statistical advice in the initial phases of the project. We greatly appreciate their efforts.

Funding

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grant APP1054146 (CI Braithwaite).

Data sharing statement

Data will be made publicly available to the extent that individual participants or participating hospitals cannot be identified, in accordance with requirements of the approving Human Research Ethics Committees.