-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marianne Wyder, Manaan K Ray, Helena Roennfeldt, Michael Daly, David Crompton, How health care systems let our patients down: a systematic review into suicide deaths, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 32, Issue 5, June 2020, Pages 285–291, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To synthesize the literature in relation to findings of system errors through reviews of suicide deaths in the public mental health system.

A systematic narrative meta-synthesis using the PRISMA methodology was conducted.

All English language articles published between 2000 and 2017 that reported on system errors identified through reviews of suicide deaths were included. Articles that reported on patient factors, contact with General Practitioners or individual cases were excluded.

Results were extracted and summarized. An overarching coding framework was developed inductively. This coding framework was reapplied to the full data set.

Fourteen peer reviewed publications were identified. Nine focussed on suicide deaths that occurred in hospital or psychiatric inpatient units. Five studies focussed on suicide deaths while being treated in the community. Vulnerabilities were identified throughout the patient’s journey (i.e. point of entry, transitioning between teams, and point of exit with the service) and centred on information gathering (i.e. inadequate and incomplete risk assessments or lack of family involvement) and information flow (i.e. transitions between different teams). Beyond enhancing policy, guidelines, documentation and regular training for frontline staff there were very limited suggestions as to how systems can make it easier for staff to support their patients.

There are currently limited studies that have investigated learnings and recommendations. Identifying critical vulnerabilities in systems and to be proactive about these could be one way to develop a highly reliable mental health care system.

Introduction

Despite a reduction in deaths due to suicide in most World Health Organization (WHO) regions, suicide still accounts for ~1 million deaths per year and remains a leading cause of death among younger age groups. The 26% decline in suicide rates has not occurred in all regions with suicide disproportionately affecting those who are disadvantaged by education, employment and socioeconomic status with males continuing to be disproportionately represented in suicide data [1, 2]. Data indicate that factors such as access to mental health care, type of vocation, presence of mental illness, general health, social isolation and marital status influence the risk of suicide. [3–5]. The literature also highlights that countries with declining rates of suicide still rank as among the highest suicide rates in the world with countries such as the USA and Australia [6].

The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health in the UK report 28% of people who completed suicide had contact with mental health services in the preceding year [1, 2]. Identifying those who may attempt or die through suicide, however, is difficult. Although the human cost in pain and anguish is high, the event of a suicide remains relatively rare. While various risk factors have been identified, they do not allow to differentiate between people who had contact with the mental health services and died by suicide and those who had contact and did not die. [3–5]. Some of the risk factors identified include a history of deliberate self-harm and previous suicide attempts [4, 6–9]; family history of mental illness and suicide [4, 8, 10]; chronic mental illness, with the most common diagnosis being schizophrenia or delusional disorders [4, 9–12] or depression [4, 8, 13, 14] and drug and alcohol dependency [15] social isolation as well as age and gender [16].

There is now increasing evidence certain aspects of service provision affect the quality of care provided. While et al. [17] investigated the uptake of key mental health recommendations from the National Confidential enquiry into suicide and their impact on suicide rates. The provision of 24 hours crisis care, local policies on dual diagnosis, multidisciplinary reviews and information sharing with families after suicide were associated with the biggest falls in suicide. Services that did not implement any of these recommendations did not have a reduction in suicides [17].

To ensure that health care is delivered in a safe and optimal manner health services around the world monitor and investigate deaths and other serious adverse event which have occurred during the provision of health care. Methodologies such as root cause analysis (RCA) or Human Error and Patient Safety (HEAPS) reviews are generally used for such reviews. These tools are structured approaches to analyse serious adverse events and focus on the earliest point in the chain of events at which action could have been taken to prevent or reduce the chance of the incident. They generally adopt a no blame and system improvement approach to these investigations. Despite the richness of each of these reviews they generally focus on individual deaths and do not incorporate trend data [18]. There would however be the opportunity to apply these finding to broader health care systems issues and to determine which aspects of the health care system are preventative and protective and how to facilitate the delivery and implementation of optimum care. A systematic meta-synthesis, a methodology focussed on integrating qualitative data from different studies, would be helpful in shaping our understanding of pressure points in mental health care systems, how to address these to ensure that people who are experiencing a suicidal crisis do not fall through these cracks. It would also shape our understanding of how health care systems can best respond to those experiencing a suicidal crisis. In this review we seek to examine common systems factors affecting suicide deaths.

Methods

In this review we adopted a systematic narrative meta-synthesis methodology to summarize, explain and interpret existing evidence. This methodology provides a framework to synthesize qualitative information in the literature [19]. To conduct this review, we adopted the PRISM methodology. The results of each these articles were then extracted and summarized. An overarching coding framework was then developed inductively from this data. An inductive approach allows condensing raw textual data into a brief summary format. It also enables the development of a framework describing the underlying structure of themes that are evident in the data [20]. The coding framework developed inductively is then reapplied to the full data set to ensure that all the data was coded and accounted for. The data for this project was managed in Atlas TI, a qualitative software management tool. The initial coding framework was developed by MW.

Search strategy

Articles written in English were searched on Cinahl, Psychinfo, Medline, Ovid and Web of Science with the following search terms: (Death OR Review OR Suicide) AND (Clinical Audit OR Root Cause Analysis, OR audit OR mental health Service OR notification OR Psychological Autopsy OR Inpatient OR in-patient OR Accident and Emergency).

All English language articles that reported on system errors identified through reviews of suicide deaths that had contact with the mental health care services within a year of their death were included. Contact included inpatient units (including those who either had absconded, were absent without leave or on leave); Accident and Emergency Services or Community Mental Health Services. Mental health care services are composed of various systems, including the public mental health care system, the primary health care system (i.e. General Practitioners) as well as private providers (i.e. private psychologists etc.). System errors are often unique to each of these parts as the focus of mental health care provision is quite different. This article aimed to synthesize system errors of the mental health care system. For these reasons articles that reported on patient factors, contact with General Practitioners, individual cases were excluded from this review.

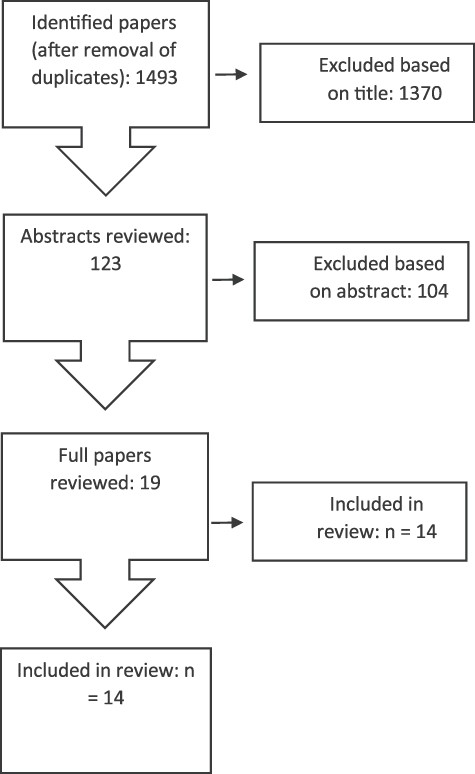

In most countries over the past 20 years there has been a shift toward community mental health care. This started during the late 1990 [21]. To ensure that the mental health findings remain relevant today we limited our search to literature published between 2000 and 2017. A total of 3754 articles were retrieved. When duplicates were removed, 1493 remained. The titles and abstracts of these articles were examined and a further 1370 were excluded. The search was conducted on 15 November 2017. The reference lists of relevant articles were also scanned. One further article was identified in this manner. A total of 14 articles were included in the final review. Figure 1 provides more details of this search.

Data analysis

Analysis

A general inductive approach was used to analyse the data where the themes and theory emerge from the data [20]. The data from the various articles were analysed with Strauss and Corbin’s three stages of coding [22]. In the first stage we used “open coding” where we identified common or broad themes. During this stage, the data was extracted from the articles and restructured into broad overarching themes. All the results were included into these summaries. The summaries were developed by MW and crosschecked by HR. The broad themes were developed by consensus. In the second stage, also called “axial coding”, these broad themes were refined into subthemes and linked to theoretical concepts within the study. This stage was managed in the qualitative software management program ATLAS TI [23]. In the third stage, these subthemes were refined and the coding framework was reapplied to the data. Both the overarching themes and associated subthemes were developed inductively. The coding and overarching framework was developed by MW and crosschecked by the research team. Where there were discrepancies these were discussed and resolved as a group.

Description of articles

A total of 14 articles were retrieved. Table 1 provides the details of these studies. Eight studies focussed on suicide deaths which occurred while the person was receiving care in hospital. Three of these focussed on suicide deaths in the psychiatric inpatient unit; one focussed on suicide death of people who had absconded. Two studies focussed on suicide deaths while being treated in the Emergency Department and one focused on suicide deaths that occurred while being treated in the general hospital. One study focussed on suicide deaths which occurred on hospital grounds. Six studies investigated deaths that occurred while being treated in the community. The timing of the last contact for these studies varied. One study focussed on suicide deaths within 1 week of discharge from the inpatient unit. One study focussed on suicide deaths that had contact within 7 days of their death with mental health care services. One focussed on those who died by suicide and contact with the mental health services within the 12 months of their death. A further two studies investigated suicides of people who were still open to the service. One study focussed on service gaps and included all suicide deaths in the region.

| Authors . | Country . | Population studied . | Treatment-related factors . | Risk assessment . | Family . | Transition of care . | Policies and procedures not followed . | Discharge planning . | Access to means . | Observational related factors (inpatient) . | Follow-up . | Service-related factors . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx not person-centred . | Tx not good practice . | Med change not monitored . | Inappropriate risk assessment . | Risk assessment not shared . | No emergency plan . | No family involvement . | Inconsistent transfer info . | Transition of care . | Staff unaware of policies and procedures . | Inappropriate discharge planning . | Access to means . | Leave policies . | Observation ward . | Escalation staffing . | No 7 days follow . | No assertive follow-up . | No 24-h crisis team . | No specialist services . | |||

| Lesage et al. [33] | Canada | All suicides | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardone et al. [24] | Italy | Hospital | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [35] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [32] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [26] | The USA | Hospital grounds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [34] | England | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [30] | The USA | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vine and Mulder [29] | Australia | Inpatient | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [30] | England | Absconded | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Riblet et al. [28] | The USA | 1 week after discharge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gillies [27] | Australia | Contact within 7 days | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Huisman et al [16] | The Netherlands | Open clients to MHS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Burgess et al. [3] | Australia | Contact within 12 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Catalan et al. [25] | England | Open to service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Authors . | Country . | Population studied . | Treatment-related factors . | Risk assessment . | Family . | Transition of care . | Policies and procedures not followed . | Discharge planning . | Access to means . | Observational related factors (inpatient) . | Follow-up . | Service-related factors . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx not person-centred . | Tx not good practice . | Med change not monitored . | Inappropriate risk assessment . | Risk assessment not shared . | No emergency plan . | No family involvement . | Inconsistent transfer info . | Transition of care . | Staff unaware of policies and procedures . | Inappropriate discharge planning . | Access to means . | Leave policies . | Observation ward . | Escalation staffing . | No 7 days follow . | No assertive follow-up . | No 24-h crisis team . | No specialist services . | |||

| Lesage et al. [33] | Canada | All suicides | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardone et al. [24] | Italy | Hospital | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [35] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [32] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [26] | The USA | Hospital grounds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [34] | England | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [30] | The USA | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vine and Mulder [29] | Australia | Inpatient | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [30] | England | Absconded | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Riblet et al. [28] | The USA | 1 week after discharge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gillies [27] | Australia | Contact within 7 days | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Huisman et al [16] | The Netherlands | Open clients to MHS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Burgess et al. [3] | Australia | Contact within 12 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Catalan et al. [25] | England | Open to service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Authors . | Country . | Population studied . | Treatment-related factors . | Risk assessment . | Family . | Transition of care . | Policies and procedures not followed . | Discharge planning . | Access to means . | Observational related factors (inpatient) . | Follow-up . | Service-related factors . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx not person-centred . | Tx not good practice . | Med change not monitored . | Inappropriate risk assessment . | Risk assessment not shared . | No emergency plan . | No family involvement . | Inconsistent transfer info . | Transition of care . | Staff unaware of policies and procedures . | Inappropriate discharge planning . | Access to means . | Leave policies . | Observation ward . | Escalation staffing . | No 7 days follow . | No assertive follow-up . | No 24-h crisis team . | No specialist services . | |||

| Lesage et al. [33] | Canada | All suicides | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardone et al. [24] | Italy | Hospital | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [35] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [32] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [26] | The USA | Hospital grounds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [34] | England | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [30] | The USA | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vine and Mulder [29] | Australia | Inpatient | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [30] | England | Absconded | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Riblet et al. [28] | The USA | 1 week after discharge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gillies [27] | Australia | Contact within 7 days | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Huisman et al [16] | The Netherlands | Open clients to MHS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Burgess et al. [3] | Australia | Contact within 12 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Catalan et al. [25] | England | Open to service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Authors . | Country . | Population studied . | Treatment-related factors . | Risk assessment . | Family . | Transition of care . | Policies and procedures not followed . | Discharge planning . | Access to means . | Observational related factors (inpatient) . | Follow-up . | Service-related factors . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx not person-centred . | Tx not good practice . | Med change not monitored . | Inappropriate risk assessment . | Risk assessment not shared . | No emergency plan . | No family involvement . | Inconsistent transfer info . | Transition of care . | Staff unaware of policies and procedures . | Inappropriate discharge planning . | Access to means . | Leave policies . | Observation ward . | Escalation staffing . | No 7 days follow . | No assertive follow-up . | No 24-h crisis team . | No specialist services . | |||

| Lesage et al. [33] | Canada | All suicides | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardone et al. [24] | Italy | Hospital | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [35] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [32] | The USA | Within ED | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [26] | The USA | Hospital grounds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [34] | England | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. [30] | The USA | Inpatient | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vine and Mulder [29] | Australia | Inpatient | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Hunt et al. [30] | England | Absconded | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Riblet et al. [28] | The USA | 1 week after discharge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gillies [27] | Australia | Contact within 7 days | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Huisman et al [16] | The Netherlands | Open clients to MHS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Burgess et al. [3] | Australia | Contact within 12 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Catalan et al. [25] | England | Open to service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

Overarching themes

Seven overarching themes were identified across the 14 articles. These included: Inappropriate or incomplete risk assessment; Lack of family involvement; Inadequate transitions and communication between different teams; Policies and procedures not always followed; Treatment not in line with current guidelines; Access to means, Observation and, Potential service gaps. Table 1 provides more details on these themes.

Inappropriate or incomplete risk assessment

All articles which focussed on suicides that occurred in the community (either shortly after discharge from an inpatient unit or while being treated in the community) noted that in many cases there were either inadequate or no formal risk assessment conducted [3, 16, 24–26]; that the attention to the risk of suicide had waned after a period of time [16]; or the person had denied suicidality. As a result, for many of these deaths the treating team had been unaware of other risk factors and the response to the suicide risk had been inadequate [3, 16, 25, 27–29]. Furthermore, it was noted that for many suicidal patients there were either incomplete or inadequate crisis or safety plans in place [27, 28]. One study noted the importance of including a psychiatrist in risk assessments [16].

Lack of family involvement

Related to incomplete risk assessments, were a lack of processes to involve families and carers in risk assessment or discharge planning. As a result, there was either a lack of collateral information collected from family around potential risks and issues, or the families had been unaware of the suicide risks [16, 25, 28, 30].

Transitions and communication between different teams

Over half of the studies highlighted a lack of communication or collaboration between different services or teams [3, 16, 24, 25, 31]. There was also poor or insufficient transfer of information about the suicide risk from one service or team to another [16, 26, 31]. It was also noted that in some cases there had been poor communication between staff and patients [3]. As a result, clinicians may not have been aware of potential risks as well as protective factors for the person who died. This issue was identified across the inpatient, hospital and outpatient setting [3, 16, 24–28, 32].

Policies and procedures not always followed

In many cases there were policies and procedures in place, however, staff were not always aware of these or did not follow them [3, 24, 26, 28, 29, 33]. Of note were the policies around the 7 days follow-up after discharge [3, 27, 28, 32] or a lack of consistent assertive follow-up after a missed appointment [28, 33].

Treatment not in line with current guidelines

The various studies highlighted that the provision of accurate psychiatric diagnosis and adequate psychiatric treatment are critical for the prevention of suicide. Different cases were identified where treatments may not have been in line with best clinical practice. Some of the identified issues include non-adherence to treatment guidelines; poor assessments of symptoms changes in medication not being monitored or poor adherence and side effects not being addressed with patients [3, 27], as well as insufficient monitoring of severely depressed or psychotic patients [16].

Access to means and observation

All studies that focussed on suicide deaths occurred while being in hospital identified access to means and a lack of regular ligature reviews as being a major factor in these deaths [28, 29, 32, 34, 35]. Within the inpatient unit, inconsistent or inadequate policies around observation while people are on the ward or leave arrangement were also identified as factors in these deaths [29, 32, 34].

Lack of specialist services within the community

One study found that a lack of specialized service for those who were experiencing mental health and drug and alcohol-related issues could have contributed to some deaths [33].

Strengths and limitations

Before discussing these results some limitations should be noted. This study used an inductive approach, condensing raw data into categories. This process is inherently reductive and it is possible that some of the nuances of the different studies are lost through this process. Related to this is that while different vulnerabilities have been identified, it is difficult to determine the impact of each of these on the suicide deaths. Furthermore, the focus of this review was on suicide death that occurred within the public mental health system. Studies that focussed on the contact with General Practitioner could contain relevant information on system errors at the primary care interface. However, the inclusion of these studies would have made the studies heterogenous and would have considerably expanded the scope of the review as primary care has its unique system challenges for mental health care provision. Lastly, it is unclear if these same vulnerabilities are present in the group who did not commit suicide. It is important to note however that a narrative synthesis remains a powerful aggregative synthesis method, which allows for the identification of key themes of key themes.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic narrative meta-synthesis to investigate system pressure points within mental health care systems. While most health care districts conduct individual reviews into a suicide death that had contact with their services, only 14 peer-reviewed publication focus on synthesizing these learnings. Nine of these inquiries focussed on suicide deaths that occurred either in hospital or while being treated in a psychiatric inpatient unit or shortly after discharge. Five focussed on suicide death that had occurred within the community. The lack of research and knowledge in this area is of real concern. Identifying critical vulnerabilities in such systems and to be proactive about these could be one way to develop a highly reliable mental health care system [36]. It is important to note that the vulnerabilities, despite being undertaken in different countries, with different health care systems were remarkable consistent.

Suicide deaths while being treated in hospital

Within an inpatient or hospital setting the main concerns centred on access to means and observation of the patients. This suggests that for hospitals to provide a safe environment for those who are experiencing suicidal thoughts, routine surveys of potential ligatures and anchor points should be conducted. Furthermore, specialized protocols for suicidal patients, including continuous monitoring when possible will potentially impact on suicidal acts on the wards [32].

Suicide death while being treated in the community

For those deaths that occurred while being treated in a community setting, system vulnerabilities were identified throughout the patient’s journey starting from the point of entry to transitioning between teams to the point of exit with the service. Many of the vulnerabilities centred on information gathering (i.e. inadequate and incomplete risk assessments or lack family involvement) and information flow (i.e. transitions between different teams). These vulnerabilities are not surprising as information gathering and flow is core to managing suicide risk. The care for those experiencing a suicidal crisis is complex. It is not uncommon for a person to encounter various stakeholders such as the emergency department, the crisis team, the case manager, the general practitioners or non-government organizations. Furthermore, mental health systems are not static and are composed of individuals and groups of individuals who, to meet the demands and ever-changing needs of their patients, continually construct and reconstruct themselves in loose, coordinated networks. These networks continually change over time [37–39]. It can be a real challenge to ensure that care is delivered consistently across these different networks. Transitions between teams have been identified as a common medical error for all health care systems and it has been estimated that more people have been harmed by errors in transition from one health care setting to another than any other medical error [40].

Clinical information and risk assessment

Similarly, good clinical information and risk assessments are central to the prevention of a suicide [41]. There are many scenarios as to why the risk assessment may have been inadequate and incomplete. Because of the nature of suicidal behaviours, it is possible that the person either did not disclose the extent of the suicidal thoughts and plans to the treatment teams or that life circumstances changed prior to the death. Conversely, relevant information may have been available, and, for a variety of reasons, was not included into the safety plans. Equally, it may have been collated but not appropriately interpreted or accounted for. It is also possible that the necessary safety plans may have been developed but were not documented or shared with all the parties. Finally, it is possible that while all parties knew the role they were meant to play in a person’s care plan, for different reasons, these were not executed. The issue of a lack of good clinical information can be compounded by the clinicians’ level of experience and training, their ability to include the families as well as more systemic issues such as not enough time for handover of care or a lack of beds. Indeed, research into clinical decision-making around suicidal behaviours suggests decisions are influenced by previous experiences as well as resources. While most people describe the decisions-making process as independent of resources, the threshold for admission can change if more beds are available Time pressure, cost and resources can also influence decisions [42].

These vulnerabilities highlight that it is critical to create an enabling infrastructure, which not only supports clinicians’ decision-making but also the transfer of information. There are currently no industry-wide standards for data and communication and there are very limited integrated systems linking the various parts of the health care system [43]. Furthermore, there are currently limited validated measures that allow to measure the process or the outcomes [44]. While quality risk assessments remain a critical tool for practitioners, the current risk assessment tools are often inadequate as they generally focus on the classification of suicide risk in low, medium and high, which have little predictive value. Indeed, it was found that most of those who might be viewed as at high risk of suicide will not die by suicide and over half of those who die through suicide would have been classified as low [45]. These findings highlight that not all risks can be managed and, even when all risks are managed, a person may still suicide. Being too risk-averse can work to the detriment of people with a serious mental illness. It would be unrealistic and counterproductive if health care systems were to start practicing ‘defensively’ towards all those who present to the emergency department. Given the rarity of the event it may mean that restraints will be imposed on patients who would not die by suicide even without such care [46].

Many of the vulnerabilities identified in this review are well known. However, there were very limited suggestions beyond enhancing policy, guidelines, documentation and regular training for frontline staff as to how systems can support their staff in delivering high reliability in care where they are accountable for clinical performance and where systems make it easier for staff to support their patients. While these are critical to the provision of a good service, when they are used alone are unlikely to lead to sustained patient safety improvements as they do not address the larger scale system improvements, which require high reliability in delivery [47]. Formulating recommendations is more difficult than finding pressure points. It has been estimated that only 8% of recommendations that resulted from critical incidents reviews were considered to be strong in that they were likely to be effective and sustainable [18].

While clinical incident reviews can be a useful tool to identify system errors, these can be resource intensive and divert resources from quality improvement. Furthermore, it remains unclear how system recommendations improve our knowledge on contributing factors. It will be important for health care services to not only aggregate the findings from the various clinical incidents but to also design serious incident triage tool and processes to determine the most effective analysis methodology to review clinical incidents. It will also be imperative to improve the strength and efficacy of recommendations from clinical incident analysis.

Conclusions

There are currently limited studies which investigating learnings and recommendations that have arisen from reviews into suicide deaths. Furthermore, while this review has identified several system vulnerabilities within the mental health care system, there was limited attention to how to address these concerns. Poor adherence to policies and procedures, poor communication both within and between teams are common pressure points in all health care and explain many health care errors [40]. A more systematic approach that would assess the key omission of care as well as the reliability of local systems alongside effective implementation, improvement and redesign, would allow for the critical vulnerabilities of care to be addressed.