-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dmitry Pevni, Nahum Nesher, Amir Kramer, Yosef Paz, Ariel Farkash, Yanai Ben-Gal, Does bilateral versus single thoracic artery grafting provide survival benefit in female patients?, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 28, Issue 6, June 2019, Pages 860–867, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivy367

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bilateral internal thoracic artery (BITA) grafting is associated with improved survival, but this technique is reluctantly used in women due to an increased risk of sternal wound infection. The aim of this study was to compare the long-term survival of women who underwent BITA grafting and single internal thoracic artery (SITA) grafting.

We performed a retrospective analysis of 556 consecutive female BITA patients and 685 female SITA patients.

SITA patients were older and more likely to have comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, chronic renal failure, peripheral vascular disease and cerebral vascular disease). Operative mortality showed a trend towards a benefit for BITA (2.9% vs 5.0% for SITA, P = 0.06). The sternal wound infection rates were similar (3.4% vs 2.9%, P = 0.6); however, the occurrence of stroke was significantly lower in the SITA group (3.4% vs 1.2%, P = 0.007). The median survival of the BITA group was significantly better {13.8 years [95% confidence interval (CI) 12.8–14.9] vs 10.3 years [95% CI 9.6–11.1], P = 0.001}. After propensity score matching (491 pairs), the assignment to BITA was not associated with increased early mortality or complication rates, and the choice of BITA grafting was associated with better survival [14.5 years (95% CI 13.3–15.6) vs 11.8 years (95% CI 10.7–12.9)]. Only the choice of conduits was associated with increased late mortality (multivariable analysis, hazard ratio 1.28, 95% CI 1.024–1.591; P = 0.03).

The low early mortality and complication rate, and the long-term survival benefit of BITA compared to SITA grafting, support the use of BITA grafting in women.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been established as an effective treatment of symptomatic multivessel coronary artery disease [1]. Total arterial revascularization using bilateral internal thoracic artery (BITA) has demonstrated survival benefits compared to a single internal thoracic artery (SITA) in combination with other grafts [2, 3]. However, although BITA grafting of left side coronary vessels was shown to provide improved long-term survival and decreased rates of reinterventions [4], most surgeons are reluctant to use this technique. According to the data of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons in the USA, BITA grafting was used for only 4.7% of patients who underwent primary CABG in 2011 [5]. This low rate may be explained by an increased risk of sternal wound infection (SWI), technical complexity, unfamiliarity with the BITA graft configuration and lack of evidence to support the use of BITA rather than SITA grafting.

The use of BITA grafting in women is extremely low and did not exceed 0.9 of all primary CABG procedures performed in the USA in 2014 [5]. The rates of both referral and surgical revascularization are lower for women than men with coronary artery disease [6, 7]. Women undergoing CABG generally had a higher comorbidity profile, were older and were more often overweight, with diabetes mellitus (DM) and with osteoporosis of the sternum than men [8, 9]. Furthermore, the strategies for surgical coronary revascularization may also differ between the genders. Saraiva et al. [10] reported that BITA grafting in women was associated with higher mortality and SWI rates than SITA grafting. In contrast, Rieß et al. [11] reported no significant differences in the late follow-up results between male patients and female patients. The lack of convincing evidence to support the use of BITA rather than SITA grafting in women is another reason for the very low rate that BITA grafting is performed in women.

BITA grafting has been the revascularization technique of choice without gender discrimination in the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center since 1996, with the sole exception of female patients with multiple risk factors. The main aim of our current study was to compare early results and late survival of women who underwent either BITA or SITA grafting during 1996–2011.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tel Aviv Medical Center. Individual patient consent was waived. Prospective clinical data are routinely collected during surgical admission and comprise part of the Cardiac Surgery Department Database.

Study population

This single-centre retrospective cohort included consecutive patients who underwent primary CABG between 1996 and 2011. Eligibility criteria were at least 2 left coronary system vessel diseases, having undergone isolated CABG with at least 1 ITA conduit and a minimum of 2 conduits targeting the left coronary system. Follow-up survival data collection was completed (98.2%) by means of the Israeli National Registry database. Left system BITA grafting was the preferred method of arterial revascularization. SITA with other grafts was more often used in female patients with multiple risk factors for SWI, such as obesity, DM, osteoporosis and chronic lung disease (CLD), and those who were older than 75 years. Of 1241 female patients who underwent primary CABG during the study period, 556 (45%) patients underwent BITA grafting and 685 (55%) patients underwent SITA grafting.

Surgical techniques

Operations were performed using the standard cardiopulmonary bypass or off-pump CABG. The ITAs were harvested as skeletonized vessels. BITA grafts were used to graft the left coronary system in all cases. The 2 graft arrangements were in situ BITA grafting and composite T-grafting with a free right ITA attached end-to-side on the left ITA. The choice of configuration was determined by previously detailed technical considerations [12–14]. Our strategy was to use the rGEA and the RA as grafts to the right coronary artery branches only in the presence of a significant degree of stenosis (i.e., >80%).

Definitions and data collection

The patients’ data were analysed according to the EuroSCORE clinical data standards [15, 16]. The follow-up for early complications was 30 days from the operation or the length of the hospital period for patients who were not discharged from our hospital within 30 days.

DM was classified as non-insulin-treated DM (NIDDM) and insulin-treated DM (IDDM). A cerebrovascular accident (CVA) was defined as a new permanent neurological deficit and computed tomographic evidence of cerebral infarction. A perioperative myocardial infarction (MI) was defined as the postoperative appearance of new Q waves or ST segment elevation of more than 2 mm on an electrocardiograph, accompanied by a creatinine phosphokinase-myocardial band >50 mU/ml, with or without regional wall motion abnormality. Chronic renal failure (CRF) was defined according to creatinine clearance (<85 ml/min). Deep SWI in this setting included patients with deep infection involving either the sternum or the substernal tissues. Diabetic end organ damage was defined as diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy or diabetic foot syndrome.

Emergency operations were defined as surgeries conducted within 24 h of cardiac catheterization or those performed on patients with acute evolving MI, pulmonary oedema or in cardiogenic shock.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are described as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were evaluated for normal distribution using the histogram and Q–Q plots and described as medians and interquartile ranges or as means and standard deviations. The length of follow-up was measured using a reverse censoring method. Categorical variables were compared between grafting techniques using the χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared between them using an independent samples t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test. Mortality during the follow-up period was described by a Kaplan–Meier curve. Multivariable Cox regression was used to study the association between grafting techniques and mortality while controlling for confounders. The regression comprised 4 blocks: the first included the grafting technique to describe the crude association, the second included age to describe the association after controlling for the patient’s age, and the third and fourth blocks were performed using the backwards stepwise method (the Wald test was used as criteria, P > 0.1 for removal). The third block included preoperative parameters, and the fourth block included the following operative parameters: ≥3 bypasses, right system revascularization and off-pump CABG. To control for differences between the groups in baseline characteristics, the patients were matched using a propensity score, which was calculated as the probability of having BITA grafting. The logistic regression used to calculate the propensity score included 21 characteristics. The preoperative characteristics were age, NIDDM, IDDM, CLD, CRF, DM with end organ damage, unstable angina pectoris, critical preoperative state, emergency operation, preoperative use of an intra-aortic pump, neurological dysfunction, repeat operation (Redo), peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, old MI, acute MI, congestive heart failure, preoperative percutaneous intervention, left main disease, the number of diseased vessels and left ventricular ejection fraction ≤50% and ejection fraction ≤30. The type of conduit that had been used (BITA or SITA) was forced into the multivariable models. We used the backwards stepwise (likelihood ratio) method to choose the predictors for inclusion in the multivariable analysis, which included the following preoperative and operative data: DM, the number of grafts constructed, off-pump CABG, sequential grafting and the use of other conduits (RA, SVG or rGEA). The operative era (1996–2000 vs 2001–2011) was forced into the regressions. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported.

An absolute difference of up to 5% in the propensity score was considered acceptable for matching. After matching, the patients were compared using the paired samples t-test, the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the McNemar’s test. An absolute standardized difference of up to 0.15 was considered acceptable for matching. The multivariable stratified Cox regression was used to describe the association after matching. The regression included 1 block for the grafting technique to describe the crude association, and a second block included procedure parameters using the backwards stepwise method. All statistical tests were 2-sided. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The plot of the Schoenfeld residuals versus time and the log minus log plot were used to check for the proportional hazard assumption. The Box Tidwell test was used to evaluate the logistic regression assumption.

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., 2013).

RESULTS

A total of 1241 women underwent isolated CABG at our medical centre during 1996–2011. The SITA patients had a significantly higher comorbidity profile: they were older and more patients had IDDM, CLD, CRF, decreased LV function, unstable angina pectoris, preoperative neurological dysfunction, PTCA and Redo (Table 1).

| Factors . | Unmatched groups . | Matched groups . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BITA [N = 556 (45%)] . | SITA [N = 685 (55%)] . | P-valuea . | BITA (N = 491) . | SITA (N = 491) . | P-valueb . | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 9.5 | 70 ± 9.2 | 0.001c | 68.9 ± 9.5 | 69.5 ± 9.2 | 0.22d |

| NIDDM, n (%) | 208 (37.4) | 287 (41.9) | 0.1 | 182 (31.1) | 194 (39.5) | 0.45 |

| IDDM, n (%) | 19 (3.4) | 76 (11.4) | 0.001 | 19 (3.9) | 23 (4.7) | 0.6 |

| DM EOD, n (%) | 33 (5.9) | 114 (16.6) | 0.01 | 33 (6.7) | 45 (9.2) | 0.13 |

| CLD, n (%) | 27 (4.9) | 67 (9.8) | 0.01 | 27 (5.5) | 35 (7.1) | 0.35 |

| CHF, n (%) | 139 (25) | 141 (20.6) | 0.06 | 94 (19.1) | 98 (20) | 0.8 |

| CRF, n (%) | 23 (4.1) | 64 (9.3) | 0.001 | 22 (4.5) | 26 (5.3) | 0.66 |

| Old MI, n (%) | 191 (34) | 253 (36.9) | 0.3 | 164 (33.4) | 176 (35.8) | 0.63 |

| Recent MI, n (%) | 167 (30) | 198 (28.9) | 0.66 | 137 (27.9) | 133 (27.1) | 0.8 |

| UAP, n (%) | 345 (62.1) | 470 (68.6) | 0.01 | 311 (63.3) | 319 (65) | 0.64 |

| EF <50%, n (%) | 74 (13.3) | 157 (22.9) | 0.001 | 73 (14.9) | 77 (15.7) | 0.77 |

| EF <30, n (%) | 31 (5.6) | 42 (6.1) | 0.7 | 25 (5.1) | 32 (6.5) | 0.6 |

| IABP, n (%) | 39 (7) | 62 (9.1) | 0.1 | 35 (7.1) | 35 (7.1) | 1.0 |

| Emergency, n (%) | 84 (15.1) | 128 (17.1) | 0.09 | 79 (16.1) | 78 (15.9) | 1.0 |

| Redo, n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 30 (4.4) | 0.01 | 6 (1.2 | 9 (1.8 | 0.6 |

| PVD CVD, n (%) | 127 (22.8) | 177 (25.8) | 0.2 | 103 (21) | 121 (24.6) | 0.7 |

| Critical, n (%) | 38 (6.8) | 61 (8.9) | 0.2 | 34 (6.9) | 33 (6.7) | 0.9 |

| ND, n (%) | 17 (3.1) | 45 (6.6) | 0.005 | 17 (3.1) | 24 (4.9) | 0.33 |

| LM, n (%) | 16 (39) | 197 (28.8) | 0.57 | 138 (28.1) | 140 (28.5) | 0.9 |

| Preoperative PCI, n (%) | 66 (11.9) | 109 (15.9) | 0.04 | 64 (13) | 69 (14.1) | 0.7 |

| 3VD, n (%) | 422 (75.9) | 489 (71.4) | 0.07 | 312 (64.5) | 309 (62.9) | 0/8 |

| Factors . | Unmatched groups . | Matched groups . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BITA [N = 556 (45%)] . | SITA [N = 685 (55%)] . | P-valuea . | BITA (N = 491) . | SITA (N = 491) . | P-valueb . | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 9.5 | 70 ± 9.2 | 0.001c | 68.9 ± 9.5 | 69.5 ± 9.2 | 0.22d |

| NIDDM, n (%) | 208 (37.4) | 287 (41.9) | 0.1 | 182 (31.1) | 194 (39.5) | 0.45 |

| IDDM, n (%) | 19 (3.4) | 76 (11.4) | 0.001 | 19 (3.9) | 23 (4.7) | 0.6 |

| DM EOD, n (%) | 33 (5.9) | 114 (16.6) | 0.01 | 33 (6.7) | 45 (9.2) | 0.13 |

| CLD, n (%) | 27 (4.9) | 67 (9.8) | 0.01 | 27 (5.5) | 35 (7.1) | 0.35 |

| CHF, n (%) | 139 (25) | 141 (20.6) | 0.06 | 94 (19.1) | 98 (20) | 0.8 |

| CRF, n (%) | 23 (4.1) | 64 (9.3) | 0.001 | 22 (4.5) | 26 (5.3) | 0.66 |

| Old MI, n (%) | 191 (34) | 253 (36.9) | 0.3 | 164 (33.4) | 176 (35.8) | 0.63 |

| Recent MI, n (%) | 167 (30) | 198 (28.9) | 0.66 | 137 (27.9) | 133 (27.1) | 0.8 |

| UAP, n (%) | 345 (62.1) | 470 (68.6) | 0.01 | 311 (63.3) | 319 (65) | 0.64 |

| EF <50%, n (%) | 74 (13.3) | 157 (22.9) | 0.001 | 73 (14.9) | 77 (15.7) | 0.77 |

| EF <30, n (%) | 31 (5.6) | 42 (6.1) | 0.7 | 25 (5.1) | 32 (6.5) | 0.6 |

| IABP, n (%) | 39 (7) | 62 (9.1) | 0.1 | 35 (7.1) | 35 (7.1) | 1.0 |

| Emergency, n (%) | 84 (15.1) | 128 (17.1) | 0.09 | 79 (16.1) | 78 (15.9) | 1.0 |

| Redo, n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 30 (4.4) | 0.01 | 6 (1.2 | 9 (1.8 | 0.6 |

| PVD CVD, n (%) | 127 (22.8) | 177 (25.8) | 0.2 | 103 (21) | 121 (24.6) | 0.7 |

| Critical, n (%) | 38 (6.8) | 61 (8.9) | 0.2 | 34 (6.9) | 33 (6.7) | 0.9 |

| ND, n (%) | 17 (3.1) | 45 (6.6) | 0.005 | 17 (3.1) | 24 (4.9) | 0.33 |

| LM, n (%) | 16 (39) | 197 (28.8) | 0.57 | 138 (28.1) | 140 (28.5) | 0.9 |

| Preoperative PCI, n (%) | 66 (11.9) | 109 (15.9) | 0.04 | 64 (13) | 69 (14.1) | 0.7 |

| 3VD, n (%) | 422 (75.9) | 489 (71.4) | 0.07 | 312 (64.5) | 309 (62.9) | 0/8 |

The χ2 test.

The McNemar test.

The independent t-test.

The paired samples t-test.

BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CHF: congestive heart failure; CLD: chronic lung disease; CRF: chronic renal failure; DM: diabetes mellitus; EF: ejection fraction; EOD: end organ damage; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; IDDM: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; MI: myocardial infarction; ND: neurological dysfunction; NIDDM: non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PCI: percutaneous intervention; redo: repeat operation; SD: standard deviation; SITA: single internal thoracic artery; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

| Factors . | Unmatched groups . | Matched groups . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BITA [N = 556 (45%)] . | SITA [N = 685 (55%)] . | P-valuea . | BITA (N = 491) . | SITA (N = 491) . | P-valueb . | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 9.5 | 70 ± 9.2 | 0.001c | 68.9 ± 9.5 | 69.5 ± 9.2 | 0.22d |

| NIDDM, n (%) | 208 (37.4) | 287 (41.9) | 0.1 | 182 (31.1) | 194 (39.5) | 0.45 |

| IDDM, n (%) | 19 (3.4) | 76 (11.4) | 0.001 | 19 (3.9) | 23 (4.7) | 0.6 |

| DM EOD, n (%) | 33 (5.9) | 114 (16.6) | 0.01 | 33 (6.7) | 45 (9.2) | 0.13 |

| CLD, n (%) | 27 (4.9) | 67 (9.8) | 0.01 | 27 (5.5) | 35 (7.1) | 0.35 |

| CHF, n (%) | 139 (25) | 141 (20.6) | 0.06 | 94 (19.1) | 98 (20) | 0.8 |

| CRF, n (%) | 23 (4.1) | 64 (9.3) | 0.001 | 22 (4.5) | 26 (5.3) | 0.66 |

| Old MI, n (%) | 191 (34) | 253 (36.9) | 0.3 | 164 (33.4) | 176 (35.8) | 0.63 |

| Recent MI, n (%) | 167 (30) | 198 (28.9) | 0.66 | 137 (27.9) | 133 (27.1) | 0.8 |

| UAP, n (%) | 345 (62.1) | 470 (68.6) | 0.01 | 311 (63.3) | 319 (65) | 0.64 |

| EF <50%, n (%) | 74 (13.3) | 157 (22.9) | 0.001 | 73 (14.9) | 77 (15.7) | 0.77 |

| EF <30, n (%) | 31 (5.6) | 42 (6.1) | 0.7 | 25 (5.1) | 32 (6.5) | 0.6 |

| IABP, n (%) | 39 (7) | 62 (9.1) | 0.1 | 35 (7.1) | 35 (7.1) | 1.0 |

| Emergency, n (%) | 84 (15.1) | 128 (17.1) | 0.09 | 79 (16.1) | 78 (15.9) | 1.0 |

| Redo, n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 30 (4.4) | 0.01 | 6 (1.2 | 9 (1.8 | 0.6 |

| PVD CVD, n (%) | 127 (22.8) | 177 (25.8) | 0.2 | 103 (21) | 121 (24.6) | 0.7 |

| Critical, n (%) | 38 (6.8) | 61 (8.9) | 0.2 | 34 (6.9) | 33 (6.7) | 0.9 |

| ND, n (%) | 17 (3.1) | 45 (6.6) | 0.005 | 17 (3.1) | 24 (4.9) | 0.33 |

| LM, n (%) | 16 (39) | 197 (28.8) | 0.57 | 138 (28.1) | 140 (28.5) | 0.9 |

| Preoperative PCI, n (%) | 66 (11.9) | 109 (15.9) | 0.04 | 64 (13) | 69 (14.1) | 0.7 |

| 3VD, n (%) | 422 (75.9) | 489 (71.4) | 0.07 | 312 (64.5) | 309 (62.9) | 0/8 |

| Factors . | Unmatched groups . | Matched groups . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BITA [N = 556 (45%)] . | SITA [N = 685 (55%)] . | P-valuea . | BITA (N = 491) . | SITA (N = 491) . | P-valueb . | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 9.5 | 70 ± 9.2 | 0.001c | 68.9 ± 9.5 | 69.5 ± 9.2 | 0.22d |

| NIDDM, n (%) | 208 (37.4) | 287 (41.9) | 0.1 | 182 (31.1) | 194 (39.5) | 0.45 |

| IDDM, n (%) | 19 (3.4) | 76 (11.4) | 0.001 | 19 (3.9) | 23 (4.7) | 0.6 |

| DM EOD, n (%) | 33 (5.9) | 114 (16.6) | 0.01 | 33 (6.7) | 45 (9.2) | 0.13 |

| CLD, n (%) | 27 (4.9) | 67 (9.8) | 0.01 | 27 (5.5) | 35 (7.1) | 0.35 |

| CHF, n (%) | 139 (25) | 141 (20.6) | 0.06 | 94 (19.1) | 98 (20) | 0.8 |

| CRF, n (%) | 23 (4.1) | 64 (9.3) | 0.001 | 22 (4.5) | 26 (5.3) | 0.66 |

| Old MI, n (%) | 191 (34) | 253 (36.9) | 0.3 | 164 (33.4) | 176 (35.8) | 0.63 |

| Recent MI, n (%) | 167 (30) | 198 (28.9) | 0.66 | 137 (27.9) | 133 (27.1) | 0.8 |

| UAP, n (%) | 345 (62.1) | 470 (68.6) | 0.01 | 311 (63.3) | 319 (65) | 0.64 |

| EF <50%, n (%) | 74 (13.3) | 157 (22.9) | 0.001 | 73 (14.9) | 77 (15.7) | 0.77 |

| EF <30, n (%) | 31 (5.6) | 42 (6.1) | 0.7 | 25 (5.1) | 32 (6.5) | 0.6 |

| IABP, n (%) | 39 (7) | 62 (9.1) | 0.1 | 35 (7.1) | 35 (7.1) | 1.0 |

| Emergency, n (%) | 84 (15.1) | 128 (17.1) | 0.09 | 79 (16.1) | 78 (15.9) | 1.0 |

| Redo, n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 30 (4.4) | 0.01 | 6 (1.2 | 9 (1.8 | 0.6 |

| PVD CVD, n (%) | 127 (22.8) | 177 (25.8) | 0.2 | 103 (21) | 121 (24.6) | 0.7 |

| Critical, n (%) | 38 (6.8) | 61 (8.9) | 0.2 | 34 (6.9) | 33 (6.7) | 0.9 |

| ND, n (%) | 17 (3.1) | 45 (6.6) | 0.005 | 17 (3.1) | 24 (4.9) | 0.33 |

| LM, n (%) | 16 (39) | 197 (28.8) | 0.57 | 138 (28.1) | 140 (28.5) | 0.9 |

| Preoperative PCI, n (%) | 66 (11.9) | 109 (15.9) | 0.04 | 64 (13) | 69 (14.1) | 0.7 |

| 3VD, n (%) | 422 (75.9) | 489 (71.4) | 0.07 | 312 (64.5) | 309 (62.9) | 0/8 |

The χ2 test.

The McNemar test.

The independent t-test.

The paired samples t-test.

BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CHF: congestive heart failure; CLD: chronic lung disease; CRF: chronic renal failure; DM: diabetes mellitus; EF: ejection fraction; EOD: end organ damage; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; IDDM: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; MI: myocardial infarction; ND: neurological dysfunction; NIDDM: non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PCI: percutaneous intervention; redo: repeat operation; SD: standard deviation; SITA: single internal thoracic artery; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

Early results

There was a trend towards increased mortality for the SITA group compared to the BITA group [16 (5%) vs 34 (3%) patients, P = 0.06] (Table 2). The CVA rate was significantly higher for the BITA group; however, the differences in SWI, Redo and perioperative MI rates did not reach a level of significance (Table 2). The increased CVA rate in the BITA group may be explained by attempts to decrease aortic manipulation in patients with calcified aorta by using BITA grafting.

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 16 (2.9) | 34 (5) | 0.06 |

| Sternal infection | 19 (3.4) | 20 (2.9) | 0.6 |

| CVA | 19 (3.4) | 8 (1.2) | 0.007 |

| Perioperative MI | 8 (1.4) | 11 (1.6) | 0.8 |

| Revision | 13 (2.3) | 27 (3.9) | 0.1 |

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 16 (2.9) | 34 (5) | 0.06 |

| Sternal infection | 19 (3.4) | 20 (2.9) | 0.6 |

| CVA | 19 (3.4) | 8 (1.2) | 0.007 |

| Perioperative MI | 8 (1.4) | 11 (1.6) | 0.8 |

| Revision | 13 (2.3) | 27 (3.9) | 0.1 |

The χ2 or the Fisher’s exact test.

BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; MI: myocardial infarction; SITA: single internal thoracic artery.

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 16 (2.9) | 34 (5) | 0.06 |

| Sternal infection | 19 (3.4) | 20 (2.9) | 0.6 |

| CVA | 19 (3.4) | 8 (1.2) | 0.007 |

| Perioperative MI | 8 (1.4) | 11 (1.6) | 0.8 |

| Revision | 13 (2.3) | 27 (3.9) | 0.1 |

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 16 (2.9) | 34 (5) | 0.06 |

| Sternal infection | 19 (3.4) | 20 (2.9) | 0.6 |

| CVA | 19 (3.4) | 8 (1.2) | 0.007 |

| Perioperative MI | 8 (1.4) | 11 (1.6) | 0.8 |

| Revision | 13 (2.3) | 27 (3.9) | 0.1 |

The χ2 or the Fisher’s exact test.

BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; MI: myocardial infarction; SITA: single internal thoracic artery.

Late results for unmatched groups

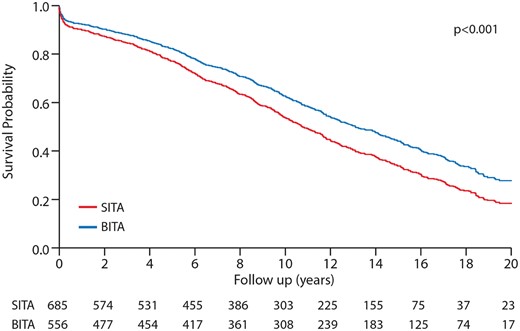

The median follow-up time was 15.6 years (evaluated using the reverse censoring method, range: 1 day–21.2 years). A total of 319 BITA patients and 427 SITA patients died. The 10-year and 15-year Kaplan–Meier survival of the patients in the BITA group was significantly better (65.4% and 43.2% vs 51.4% and 34.5% for the SITA group, P < 0.001, the log-rank test, Fig. 1). The survival data for unmatched SITA and BITA female patients are shown in Fig. 1. The median survival for the BITA patients was 13.8 years (95% CI 12.8–14.9) compared with 10.3 years (95% CI 9.6–11.1) for the SITA patients. The equality of survival distribution for the unmatched SITA and BITA groups demonstrated a significant difference (P < 0.001).

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing survival of patients before matching: BITA versus SITA. BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; SITA: single internal thoracic artery.

To identify independent predictors of late death, a Cox proportional hazards regression model was created to measure the effects of various prognostic factors on time-to-response late survival. The choice of the conduit SITA versus BITA was associated with increased overall mortality (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.14–1.53; P = 0.001). In addition, after forcing preoperative and intraoperative characteristics in a Cox model, SITA grafting remained an independent predictor for increased mortality (HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.036–1.418; P = 0.01). Other independent predictors for mortality were NIDDM (HR 1.40, 95% CI 1.215–1.654; P = 0.001), IDDM (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.254–2.194; P = 0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.122–1.896; P = 0.004), congestive heart failure (HR 1.4, 95% CI 1.195–1.675; P = 0.001) and Redo (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.397–2.925; P = 0.001). The right system revascularization was associated with better survival (HR 0.7, 95% CI 0.642–0.926; P = 0.001) (Table 3).

| . | HR (95% CI) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| SITA | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 0.001 |

| NIDDM | 1.40 (1.215–1.654) | 0.001 |

| IDDM | 1.66 (1.254–2.194) | 0.001 |

| CLD | 1.44 (1.122–1.896) | 0.004 |

| CHF | 1.4 (1.195–1.675) | 0.001 |

| Redo | 2.0 (1.397–2.925) | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.047–1.067) | 0.001 |

| Critical | 1.46 (1.130–1.880) | 0.005 |

| CRF | 1.26 (0.967–1643) | 0.08 |

| UAP | 0.88 (0.757–1.036) | 0.13 |

| EF <50 | 1.6 (0.970–1.039) | 0.12 |

| OPCAB | 1.15 (0.975–1.367) | 0.09 |

| Right system | 0.7 (0.642–0.926) | 0.001 |

| . | HR (95% CI) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| SITA | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 0.001 |

| NIDDM | 1.40 (1.215–1.654) | 0.001 |

| IDDM | 1.66 (1.254–2.194) | 0.001 |

| CLD | 1.44 (1.122–1.896) | 0.004 |

| CHF | 1.4 (1.195–1.675) | 0.001 |

| Redo | 2.0 (1.397–2.925) | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.047–1.067) | 0.001 |

| Critical | 1.46 (1.130–1.880) | 0.005 |

| CRF | 1.26 (0.967–1643) | 0.08 |

| UAP | 0.88 (0.757–1.036) | 0.13 |

| EF <50 | 1.6 (0.970–1.039) | 0.12 |

| OPCAB | 1.15 (0.975–1.367) | 0.09 |

| Right system | 0.7 (0.642–0.926) | 0.001 |

Cox regression analysis.

CHF: congestive heart failure; CI: confidence interval; CLD: chronic lung disease; CRF: chronic renal failure; EF: ejection fraction; HR: hazard ratio; IDDM: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; NIDDM: non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; OPCAB: off-pump coronary artery bypass; Redo: repeat operation; SITA: single internal thoracic artery; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

| . | HR (95% CI) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| SITA | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 0.001 |

| NIDDM | 1.40 (1.215–1.654) | 0.001 |

| IDDM | 1.66 (1.254–2.194) | 0.001 |

| CLD | 1.44 (1.122–1.896) | 0.004 |

| CHF | 1.4 (1.195–1.675) | 0.001 |

| Redo | 2.0 (1.397–2.925) | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.047–1.067) | 0.001 |

| Critical | 1.46 (1.130–1.880) | 0.005 |

| CRF | 1.26 (0.967–1643) | 0.08 |

| UAP | 0.88 (0.757–1.036) | 0.13 |

| EF <50 | 1.6 (0.970–1.039) | 0.12 |

| OPCAB | 1.15 (0.975–1.367) | 0.09 |

| Right system | 0.7 (0.642–0.926) | 0.001 |

| . | HR (95% CI) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| SITA | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 0.001 |

| NIDDM | 1.40 (1.215–1.654) | 0.001 |

| IDDM | 1.66 (1.254–2.194) | 0.001 |

| CLD | 1.44 (1.122–1.896) | 0.004 |

| CHF | 1.4 (1.195–1.675) | 0.001 |

| Redo | 2.0 (1.397–2.925) | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.047–1.067) | 0.001 |

| Critical | 1.46 (1.130–1.880) | 0.005 |

| CRF | 1.26 (0.967–1643) | 0.08 |

| UAP | 0.88 (0.757–1.036) | 0.13 |

| EF <50 | 1.6 (0.970–1.039) | 0.12 |

| OPCAB | 1.15 (0.975–1.367) | 0.09 |

| Right system | 0.7 (0.642–0.926) | 0.001 |

Cox regression analysis.

CHF: congestive heart failure; CI: confidence interval; CLD: chronic lung disease; CRF: chronic renal failure; EF: ejection fraction; HR: hazard ratio; IDDM: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; NIDDM: non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; OPCAB: off-pump coronary artery bypass; Redo: repeat operation; SITA: single internal thoracic artery; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

Matched results

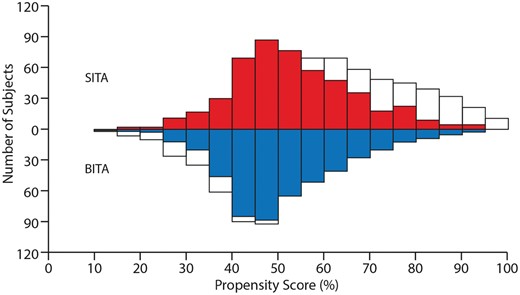

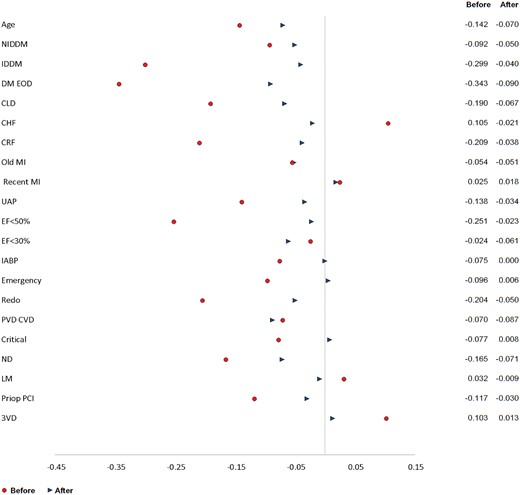

Propensity score matching was performed to compare outcomes between groups. The results yielded 491 pairs of well‐matched patients from the 2 groups (Figs 2 and 3).

A mirrored histogram (BITA and SITA). White colour indicates unmatched patients, and red (SITA) and blue (BITA) colours indicate matched patients. BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; SITA: single internal thoracic artery.

A standardized differences plot (BITA versus SITA) before–before matching and after–after matching. BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CHF: congestive heart failure; CLD: chronic lung disease; CRF: chronic renal failure; DM: diabetes mellitus; EF: ejection fraction; EOD: end organ damage; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; IDDM: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; MI: myocardial infarction; ND: neurological dysfunction; NIDDM: non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PCI: percutaneous intervention; redo: repeat operation; SITA: single internal thoracic artery; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

Early results for matched groups

The early mortality rate was low in the matched BITA and SITA groups (1.6% vs 2.9%, P = 0.3) (Table 4). Similar results were observed for postoperative SWI (3.3% vs 2.6%, P = 0.7) and CVA (3.3% vs 1.4%, P = 0.09). Revision and preoperative MI rates were not significantly different for the 2 groups (Table 4).

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 8 (1.6) | 14 (2.9) | 0.3 |

| Deep sternal infection | 16 (3.3) | 13 (2.6) | 0.7 |

| CVA | 16 (3.3) | 7 (1.4) | 0.09 |

| Perioperative MI | 5 (1) | 8 (1.6) | 0.5 |

| Revision | 11 (2.2) | 18 (3.7) | 0.26 |

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 8 (1.6) | 14 (2.9) | 0.3 |

| Deep sternal infection | 16 (3.3) | 13 (2.6) | 0.7 |

| CVA | 16 (3.3) | 7 (1.4) | 0.09 |

| Perioperative MI | 5 (1) | 8 (1.6) | 0.5 |

| Revision | 11 (2.2) | 18 (3.7) | 0.26 |

The McNemar’s test.

BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; MI: myocardial infarction; SITA: single internal thoracic artery.

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 8 (1.6) | 14 (2.9) | 0.3 |

| Deep sternal infection | 16 (3.3) | 13 (2.6) | 0.7 |

| CVA | 16 (3.3) | 7 (1.4) | 0.09 |

| Perioperative MI | 5 (1) | 8 (1.6) | 0.5 |

| Revision | 11 (2.2) | 18 (3.7) | 0.26 |

| Factors . | BITA, N (%) . | SITA, N (%) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early mortality | 8 (1.6) | 14 (2.9) | 0.3 |

| Deep sternal infection | 16 (3.3) | 13 (2.6) | 0.7 |

| CVA | 16 (3.3) | 7 (1.4) | 0.09 |

| Perioperative MI | 5 (1) | 8 (1.6) | 0.5 |

| Revision | 11 (2.2) | 18 (3.7) | 0.26 |

The McNemar’s test.

BITA: bilateral internal thoracic artery; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; MI: myocardial infarction; SITA: single internal thoracic artery.

Overall survival for the matched groups

The long-term survival was significantly better for the BITA patients. The median survival for the BITA patients was 14.5 years (95% CI 13.3–15.6) compared with 11.8 years (95% CI 10.7–12.9) for the SITA patients. The equality of survival distribution for the unmatched SITA and BITA groups revealed a significant difference (P < 0.001). In the multivariable analysis using the backwards method for variables selection, all variables were removed from regression and only the choice of conduits, SITA or BITA, was associated with increased late mortality (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.024–1.591; P = 0.03).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents one of the largest experiences in BITA grafting in women. BITA grafting is the preferred left-sided revascularization technique in our centre since 1996. We have used BITA arterial revascularization in more than 45% of all female patients. The advantages of our investigation are that it is based on data obtained from a centre where BITA is routinely performed and that it is one of the largest studies that analysed the benefit of BITA versus SITA grafting. The main finding of our current study is a long-term survival benefit of BITA grafting for women. Despite the presence of multiple risk factors, the early mortality and major event rates were similar for BITA and SITA groups. Assignment to BITA grafting was a significant predictor for better survival in both the matched and non-matched groups.

ITA grafting is generally accepted as the best graft for myocardial revascularization for many reasons, 1 of which is the rarity of the development of atherosclerosis. There are numerous explanations for the resistance of an ITA to developing atherosclerosis, such as shear stress forces, endothelial cell attachment with tight endothelial junctions, biochemical generation of important molecules (e.g., nitric oxide and antithrombotic factors) and resistance to the generation of selectins and other adhesion molecules [17, 18]. In addition, ITA grafts have been associated with long-term patency and improved survival [19, 20]. The advantages of left ITA grafting motivated the use of BITA for myocardial revascularization, and most retrospective studies reported an improved long-term survival and reduced the need for repeat revascularization for patients who underwent BITA [2–5, 21, 22]. Patients who underwent BITA in those studies were significantly younger, more likely to be men and less likely to have DM or CLD compared with the SITA patients. The randomized control trials designed to provide a decisive answer to the BITA versus SITA question failed to demonstrate a survival benefit for BITA over SITA at the 5-year time point, as originally expected [23, 24]. According to the guidelines of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons on arterial revascularization, the use of BITA should be considered in patients who do not have an excessive risk of sternal complications (class IIa, level B) [25]. The advantages of BITA grafting have been demonstrated in other high-risk groups of patients, such as those with DM [26]. Despite these recommendations, the use of BITA remains limited and accounts for only 5% of all CABG procedures in the USA [5]. This can probably be explained by the potential higher risk of SWI, greater technical complexity, increased length of the procedure associated with the harvest of a second ITA graft and the lack of strong supportive evidence for the use of BITA in high-risk patients.

Data on using BITA grafting in CABG surgery in female patients are sparse. BITA grafting appears to be underused in women; only 2.3% of women who underwent CABG (0.8% of total CABG procedures) in 2014 received a BITA graft in the USA [5, 27]. The limited use of BITA grafting has been associated with the higher comorbidity profile of women than men who undergo CABG [8–10]. However, the few recent studies that used the propensity score matching analysis demonstrated that female gender is not a risk factor for CABG [11, 28, 29]. Moreover, Kurlansky et al. [29] demonstrated that the superior results of BITA grafts are independent of gender. Our current study includes 1241 consecutive female patients who underwent isolated CABG in our centre from 1996 to 2011. The main reason for our selection of BITA grafting was the lack of multiple severe comorbidities. Most of the patients referred to BITA CABG were younger than 75 years and had no more than 1 risk factor (e.g. NIDDM, COPD, congestive heart failure or CRF). We did not find any significant difference in early mortality or complications between the BITA and SITA patients, and we believe that this is associated with our patient selection policy. BITA harvesting was not a predictor for SWI, and long-term survival was significantly better for the BITA patients. Therefore, BITA grafting appears to provide an incremental survival benefit relative to SITA grafting in women. The results of the recent prospective investigation—ART study—presented by Taggart et al. at the 32 EACTS Congress, failed to demonstrate survival benefit of BITA versus SITA grafting during 10-year follow-up. These unexpected results were explained by the high crossover rate from the BITA arm to the SITA arm and the high rate of radial artery use in the SITA arm, which may have diluted the benefit of BITA. Despite the survival benefit of BITA grafting that was demonstrated in most retrospective studies [2–5, 21], the use of this technique in female patients remains sporadic. This may be due to the lack of evidence regarding the benefit of BITA grafting in women and its potentially increased risk of sternal infection and surgical complexity, especially in women.

Limitations

This is a single-centre observational retrospective study. The end point was overall survival rather than such end points as late MI, cardiac mortality and reinterventions, for which data were not available. Another limitation is a possible selection bias in the criteria used for the choice of the second conduit and the tendency of surgeons not to use BITA grafting in patients with an increased risk for complications associated with SWI (such as CLD, obesity and DM). This selection bias on the part of the surgeon was only partially accounted for in the propensity adjustment procedure.

CONCLUSION

Our study results support the use of BITA grafting in women free of multiple comorbidities. The low early mortality and complication rates, together with the survival benefit of BITA compared to SITA grafting, support the use of BITA to improve the long-term results of CABG procedures for female patients.

Conflict of interest: none declared.