-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

S M Peters, R Guppy, D Ramsewak, A Potts, Socioeconomic dimensions of the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, an assessment of stakeholder perceptions towards enhanced management through MSP, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 80, Issue 5, July 2023, Pages 1399–1409, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsad066

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The effective management of marine protected areas (MPAs) requires an in-depth understanding and assessment of the varying socioeconomic uses and users of the physical space. However, in some localities, little research is conducted on this aspect and in particular user perceptions on current and proposed management strategies for MPAs. Such site-specific evaluations are imperative to developing context-dependent management measures. The aim of this study was to identify the spatial extent of socioeconomic activities, assess stakeholders’ awareness of the varying socioeconomic activities that take place in the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, Tobago, and gauge stakeholder support for proposed management mechanisms, namely marine spatial planning (MSP). Targeted surveys were conducted over a six-month period, to obtain perspectives from key Marine Park stakeholder groups, namely marine resource managers, visitors, and tour operators. The results indicated over ten main socioeconomic activities occurring within the Marine Park, with multiple activities taking place in the same location. Results also suggest that stakeholders are aware of the conflicts that occur between various users of the space with jet skis operation identified as the primary contributor. Finally, using a Likert scale, stakeholder groups predominantly rated the need for a marine spatial plan as “necessary.” This research, therefore, documents existing socioeconomic activities in the Buccoo Reef Marine Park and highlights the importance of stakeholder engagement in future management strategies.

Introduction

The view that marine protected areas (MPAs) provide countless ecological and socio-economic benefits is widely supported in existing literature (e.g. Pomeroy et al., 2014; Dehens and Fanning, 2018; Lotze et al., 2018; JanBen et al., 2019; Mann-Lang et al., 2021). Some ecological benefits of MPAs include the provision of ecosystem services, climate regulation, and shoreline protection, while socioeconomic benefits include the provision of livelihoods and maintaining cultural uses (Kough et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2017; Pendleton et al., 2018; Calò et al., 2022). Assessment of the ecological and socio-economic parameters of MPAs is critical in determining level of success, and the absence of such plays a significant role in the factors contributing to the failure of many MPAs worldwide.

Socioeconomic benefits are disproportionately represented in the literature as many studies focus on fishing and fishing-related activities and tourism activities (Pascual et al., 2016; Pendleton et al., 2018; De Matteis et al., 2021; Kirkman et al., 2021). This may be in part due to a limited understanding of the socioeconomic impacts over temporal and spatial scales as well as variability between stakeholder groups (Pascual et al., 2016). The complexity of the uses of MPAs and the various categories of users or stakeholders and their perceptions/expectations are often neither fully studied nor considered when designing, implementing, and assessing MPAs. This remains a critical element to inform current and future management strategies for MPA management globally, regionally, and in the local Tobago context.

Incorporating socioeconomic assessments can be burdensome due to the complexity of cultural interactions and uses in MPAs. Notwithstanding gaps in the literature, some studies detail varying degrees of success in incorporating socioeconomic considerations in the development of zoning plans (Smallhorn-West et al., 2019; Sarker et al., 2021); Bergseth et al., 2015; Gurney, 2015; Mangubhai et al., 2015; Rodriguez et al., 2015; Pascual et al., 2016). The use of socioeconomic data improves the spatial configuration of various zones created for marine spatial plans (MSPs), leads to increased levels of stakeholder support for the process, and fosters compliance (Mangubhai et al., 2015; Ruiz-Frau et al., 2015; Agiua et al., 2021). In other applications, understanding the varying stakeholders and usage types in the marine space is typified in willingness-to-pay studies (Kirkbride-Smith et al., 2016; Lara-Pulido et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022).

A review of the literature indicates an overall lack of socioeconomic-related studies in the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, with most assessments related to ecological parameters, specifically coral health (Malella et al., 2009; Lapointe et al., 2010; Alemu and Clement, 2014; Amoroso, 2017). Hassanali (2013) notes that stakeholder relations, particularly between varying user groups, including tour operators and resource managers, have been eroded, leading to limited opportunities for discourse and agreement. At a management level, minimal information has been acquired on the varying types of activities taking place within the Marine Park over spatial and temporal scales. Therefore, the lack of a current socioeconomic assessment has been identified as a significant research gap towards the further development and implementation of recommended management interventions, namely the development of a MSP.

The overall aim of this study is to determine the types of socio-economic activities that occur in the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, Tobago and the spatial interaction of these activities. The objective of the study is to provide a baseline, with up-to-date data on the types of socioeconomic activities taking place in the study area with the added use of maps illustrating the spatial interaction of these activities. This study further attempts to assess stakeholder support for future management strategies, namely the development of a MSP. Through this, it aims to explore the relationship between stakeholder perspectives and demographic traits (namely gender and education). This research will contribute to a wider study from 2019 to 2023 that aims to develop a MSP for the Buccoo Reef Marine Park in Tobago based on socioeconomic, temporal, and ecological assessments.

Study area

Trinidad and Tobago is an archipelago (comprising the two large islands and twenty-one smaller islets) located in the Caribbean Sea some eleven kilometres from the South American coast between 10° 02’–10° 50’N latitude and 60° 55’–61° 56’W longitude. The country covers a terrestrial area of 5128 km2 with its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending to 200 NM (Ramadhan and Kareem, 2022). Trinidad’s coastline covers a distance of 420 km, while Tobago, the smaller of the two islands, has 120 km of coastline. The landscape varies between the two islands with Trinidad’s landscape characterized by three mountain ranges separated by plains with a midland plain dominating three-quarter of the island.

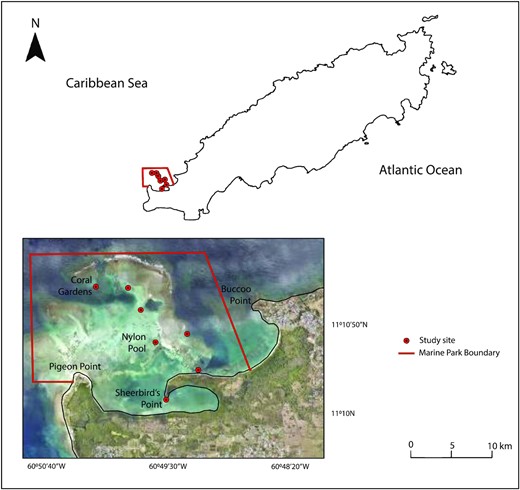

The country’s only Marine Protected Area is located off the southwest coast of Tobago. For the wider study, which includes an ecological assessment, seven study sites within the Buccoo Reef Marine Park were selected (Figure 1). This protected area is 7 km2 and is a major economic asset, attracting tens of thousands of visitors per year. The area is home to ∼70 species of tropical fish (as well as the invasive lionfish) and over forty coral species. The Buccoo Reef Marine Park is considered an IUCN category IV protected area: “Protected area managed mainly for conservation through management intervention [Habitat/Species Management Area]” (Da Costa, 2010). The park has no zoning scheme to date.

Location of the study area—the Buccoo Reef Marine Park in Tobago (with sites for the wider study identified). (Basemap source: Surveys and mapping Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Land, and Fisheries, Government of Trinidad and Tobago).

In addition to its ecological importance, its economic value cannot be understated, as indicated in a 2008 report, which valued the total economic impact of reef-related tourism and recreation in Tobago at between US$101 and US$130 million (Burke et al., 2008), equivalent to between US$461 and US$571 million in 2022. A willingness to pay study on the non-market value of sea turtles indicated a value of US$62 for a turtle encounter (Cazabon-Mannette et al., 2017), while a study on the recreational value associated with coastal water quality improvements indicated that visitors are willing to pay more to visit beaches with higher levels of environmental quality in Tobago.

Coined the Buccoo Reef Complex by Richard Laydoo in 1985, this Marine Park comprises contiguous mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and coral reef ecosystems. The Bon Accord Lagoon, which acts as a nursery and spawning area, was designated as a Ramsar Site (#1496) under the United Nations Ramsar Convention in 2004. It is the largest mangrove forest in Tobago, (predominantly Red Mangrove, Rhizophora mangle) and covers an area of 90.8 hectares, inclusive of open water lagoons (Ramsewak et al., 2022). Seagrass beds are found in the complex, with larger communities located in nearshore areas close to Buccoo Bay, Pigeon Point’s Windhole Beach, the Bon Accord Lagoon, and the Nylon Pool. Turtle Grass (Thalassia testudinum) is dominant in these areas with smaller communities of Manatee Grass (Syringodium filiforme) observed (Amoroso, 2017).

The Buccoo Reef, like other coastal and marine ecosystems throughout Tobago, is subject to numerous pressures, including coastal development and land clearing (leading to sedimentation and smothering of corals), improper sewage treatment, pollution, and fishing pressures (Ganase, 2020).; Lapointe et al., 2010). A 2017 study indicated a decline in coral cover, the proliferation of macroalgae and zoanthids, high incidences of coral diseases (such as the white band disease in Elkhorn coral), coral bleaching, and the large-scale expansion of seagrass communities to the Nylon Pool due to nutrient enrichment (Amoroso, 2017), which negatively affects the aesthetics of the “clear sand” tourism product.

The Buccoo Reef and other coastal areas in southwest Tobago are popular sites for tourism-related activities, including reef tours, snorkelling, and water sports. Tourism-related activities are prevalent along three beaches; Store Bay, Pigeon Point, and Buccoo, all of which serve as embarkation points for Buccoo Reef tours. Standard reef tours, which last approximately two hours in duration, typically comprise a stopover at Coral Gardens for coral viewing and snorkelling and at the Nylon Pool and Sheerbird’s Point (No Man’s Land) for swimming. The Marine Park is managed by the Fisheries Department, Tobago House of Assembly, and daily monitoring is conducted by a specialized unit of Park Rangers. Park regulations, including access permits and restrictions on jet ski use, have varied in recent times, along with the level of enforcement and collaborative management approaches (multistakeholder committees). Presently, there are no access fees or valid permits to enter the park. Visitor numbers fluctuate seasonally; however, exact numbers are unavailable as there is no system in place to capture this data.

Materials and methods

A combination of methods was used for this study targeted at obtaining stakeholder perspectives and identifying the spatial extent of socioeconomic activities in the study area (Table 1). Data were collected via means of semi-structured questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and direct observation.

| Socioeconomic parameter . | Methodology used Research tool . | Target . | Output . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human use of the study area | Direct observation | Types of socioeconomic activities, frequency of use, and location of activities | Qualitative and quantitative data; spatial data |

| Stakeholder perceptions on socioeconomic activities in the study area | Stakeholder questionnaires | Identification of activities and conflicts. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data |

| Stakeholders (tour operators) operations by sector | Semi-structured interviews | Location and extent of tour activities. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data; spatial data |

| Spatial extent of socioeconomic activities | Handheld GPS ArcGIS Pro | Location of activities; frequency of usage | Spatial data |

| Socioeconomic parameter . | Methodology used Research tool . | Target . | Output . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human use of the study area | Direct observation | Types of socioeconomic activities, frequency of use, and location of activities | Qualitative and quantitative data; spatial data |

| Stakeholder perceptions on socioeconomic activities in the study area | Stakeholder questionnaires | Identification of activities and conflicts. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data |

| Stakeholders (tour operators) operations by sector | Semi-structured interviews | Location and extent of tour activities. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data; spatial data |

| Spatial extent of socioeconomic activities | Handheld GPS ArcGIS Pro | Location of activities; frequency of usage | Spatial data |

| Socioeconomic parameter . | Methodology used Research tool . | Target . | Output . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human use of the study area | Direct observation | Types of socioeconomic activities, frequency of use, and location of activities | Qualitative and quantitative data; spatial data |

| Stakeholder perceptions on socioeconomic activities in the study area | Stakeholder questionnaires | Identification of activities and conflicts. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data |

| Stakeholders (tour operators) operations by sector | Semi-structured interviews | Location and extent of tour activities. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data; spatial data |

| Spatial extent of socioeconomic activities | Handheld GPS ArcGIS Pro | Location of activities; frequency of usage | Spatial data |

| Socioeconomic parameter . | Methodology used Research tool . | Target . | Output . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human use of the study area | Direct observation | Types of socioeconomic activities, frequency of use, and location of activities | Qualitative and quantitative data; spatial data |

| Stakeholder perceptions on socioeconomic activities in the study area | Stakeholder questionnaires | Identification of activities and conflicts. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data |

| Stakeholders (tour operators) operations by sector | Semi-structured interviews | Location and extent of tour activities. Stakeholder perceptions towards the creation of an accepted MSP | Qualitative data; spatial data |

| Spatial extent of socioeconomic activities | Handheld GPS ArcGIS Pro | Location of activities; frequency of usage | Spatial data |

Survey design and administration

Data on stakeholder perceptions were collected via two means: (i) semi-structured questionnaires targeting visitors to the Marine Park and marine resource managers/experts, and (ii) semi-structured interviews targeting tour operators. Questionnaires were conducted over a period from July to September 2019 and administered both in-person and online via Google Forms (following COVID-19 regulations, which included beach closure). For sampling purposes, in-person questionnaires were administered to visitors at embarkation points to the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, namely the Pigeon Point Heritage Park, the Store Bay Beach Facility, and Buccoo Beach. Workdays and weekends were alternated for questionnaire interviews, which were conducted between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. Visitors were selected at random, once over 18 years of age, and based on their willingness to participate in the survey, which lasted ∼15 min.

Semi-structured questionnaires, both in person and via telephone interviews, were also administered to marine resource managers and experts (identified from prior researcher knowledge and referrals from the management entity), including NGOs, national research institutions, government agencies, and local universities. The questionnaires comprised three main sections: (a) visitor demographics in terms of age, gender, and education level; (b) study site information with respect to reasons for visiting and identification of socioeconomic activities; and (c) perceptions on the need for zoning, which were rated using a five-point Likert scale (1-completely unnecessary to 5-completely necessary).

Semi-structured interviews were utilized to garner data from tour operators in each of the main tourism activities, including reef tours, jet skiing, kayaking, kitesurfing, and windsurfing, while persons engaged in illegal poaching (poached species include queen conch, spiny lobster, and fish species, including barracuda, parrotfish, and kingfish) were also interviewed. The interviews were conducted in person, and questions were opened ended and designed to capture information relating to the areas in which persons operate, the perceived changes in the study area over time, the threats facing the Marine Park, and the need for marine spatial planning (MSP) interventions. A map of the study area was also shown to participants to accurately indicate the areas of operation and areas in which changes were observed. All information acquired from questionnaires and semi-structured interviews was coded and input into spreadsheets using Microsoft Excel 2016.

Direct observation

Direct observation was used to identify and record the spatial distribution of socioeconomic activities identified by stakeholders. This was conducted from July to December 2019 using methods outlined by Cudney-Bueno and Basurto (2009). Using both shore and vessel-based vantage points, socioeconomic activities were observed and recorded for a period of 4 h d-1 for 3 d per week, including weekends, at varying times from 6:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. To determine the location of the various activities, a handheld GPS device (2–3-metre accuracy) was used to record the area utilized.

Mapping using ArcGIS pro

Spatial data were exported to ArcGIS Pro 2.8 using the geoprocessing spatial analyst tool. This software was used to map the extent of key features in the study area by creating point and polygon features and assigning values based on the frequency of use. Spatial data with respect to the location of socioeconomic activities, obtained through semi-structured interviews with tour operators, were recorded on a paper map and transferred to ArcGIS Pro for further analysis following the creation of line and polygon features. Maps were created to reflect the types of activities and their locations within the study area.

Data and statistical analysis

Data from semi-structured interviews were analysed using coding techniques as proposed in studies by Krippendorff (2012), Franzosi (2008), and Hsieh and Shannon (2005). Interview responses were analyzed and coded to identify the themes and sorted into categories using a tree diagram to show relationships between responses (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). The coding system was further refined following an initial analysis and categorization of responses. A similar coding system was also developed for questionnaire responses. Microsoft Excel was used to generate infographics on data, and ArcGIS Pro 2.8 was used to generate maps.

The data acquired from the semi-structured interviews and questionnaires was non-parametric as it did not meet the assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variance and due to the small and imbalanced sample sizes. The statistical testing methodology followed Cvitanovic et al., 2018. Non-parametric tests were conducted using the Real Statistics Resource Pack for Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses using the Kruskal–Wallis H test and Dunn’s post-hoc test were conducted to determine the statistical difference between the means of independent variables (stakeholder groups) and pairwise differences.

To explore the relationship between variables, such as gender or levels of education, and the perceptions of management, chi-square tests were performed. Wilcoxon-signed rank tests were performed on categorical data from the same population (for example, responses and corresponding education levels in one stakeholder group), while the Wilcoxon Rank-sum test was performed on categorical data from different populations (for example, selection of zones by two stakeholder groups). The results of all statistical tests were represented by the p and z values (based on the test conducted) to determine the presence or absence of a statistical difference. Traits, namely gender and level of education, were analysed to determine their influence on stakeholder perceptions.

Results

Stakeholder profile

The respondents in the sample comprised a representative cross-section of stakeholders, inclusive of marine resource managers and experts (n = 13), tour operators for various socioeconomic activities (n = 8), and visitors (n = 55). A total of 74 responses were obtained for the demographic questions with one omission from the marine resource managers/experts group and the visitors group . The pertinent information with respect to socio-demographic characteristics is listed in Table 2.

Stakeholders’ profile (%) for gender, age, and education level of users within the Buccoo Reef MPA.

| Variable . | % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine resource managers and experts . | Visitors . | Operators* . | Significance p-value . | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62 | 42 | 100 | 0.007 |

| Female | 38 | 58 | 0 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–27 | 15.4 | 18 | 0 | |

| 28–37 | 46.2 | 29 | 12.5 | 0.014 |

| 38–47 | 23 | 31 | 12.5 | |

| 48 and over | 15.4 | 22 | 75 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| Secondary | 15.3 | 0 | 75 | |

| Diploma | 0 | 21 | 0 | |

| Bachelors | 38.4 | 26 | 12.5 | 0.0007 |

| Masters | 31 | 49 | 0 | |

| Doctorate | 15.3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Variable . | % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine resource managers and experts . | Visitors . | Operators* . | Significance p-value . | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62 | 42 | 100 | 0.007 |

| Female | 38 | 58 | 0 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–27 | 15.4 | 18 | 0 | |

| 28–37 | 46.2 | 29 | 12.5 | 0.014 |

| 38–47 | 23 | 31 | 12.5 | |

| 48 and over | 15.4 | 22 | 75 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| Secondary | 15.3 | 0 | 75 | |

| Diploma | 0 | 21 | 0 | |

| Bachelors | 38.4 | 26 | 12.5 | 0.0007 |

| Masters | 31 | 49 | 0 | |

| Doctorate | 15.3 | 4 | 0 | |

Operators include Reef Tour Operators (2), Kayakers (1), Poachers (1), jet ski Operators (1), Kite and Windsurfing Operators (1), and Fishermen (2). Stakeholders’ profile (%) for gender, age, and education level of users within the Buccoo Reef MPA. The p-value relates to the statistical difference across stakeholder groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Stakeholders’ profile (%) for gender, age, and education level of users within the Buccoo Reef MPA.

| Variable . | % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine resource managers and experts . | Visitors . | Operators* . | Significance p-value . | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62 | 42 | 100 | 0.007 |

| Female | 38 | 58 | 0 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–27 | 15.4 | 18 | 0 | |

| 28–37 | 46.2 | 29 | 12.5 | 0.014 |

| 38–47 | 23 | 31 | 12.5 | |

| 48 and over | 15.4 | 22 | 75 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| Secondary | 15.3 | 0 | 75 | |

| Diploma | 0 | 21 | 0 | |

| Bachelors | 38.4 | 26 | 12.5 | 0.0007 |

| Masters | 31 | 49 | 0 | |

| Doctorate | 15.3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Variable . | % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine resource managers and experts . | Visitors . | Operators* . | Significance p-value . | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62 | 42 | 100 | 0.007 |

| Female | 38 | 58 | 0 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–27 | 15.4 | 18 | 0 | |

| 28–37 | 46.2 | 29 | 12.5 | 0.014 |

| 38–47 | 23 | 31 | 12.5 | |

| 48 and over | 15.4 | 22 | 75 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| Secondary | 15.3 | 0 | 75 | |

| Diploma | 0 | 21 | 0 | |

| Bachelors | 38.4 | 26 | 12.5 | 0.0007 |

| Masters | 31 | 49 | 0 | |

| Doctorate | 15.3 | 4 | 0 | |

Operators include Reef Tour Operators (2), Kayakers (1), Poachers (1), jet ski Operators (1), Kite and Windsurfing Operators (1), and Fishermen (2). Stakeholders’ profile (%) for gender, age, and education level of users within the Buccoo Reef MPA. The p-value relates to the statistical difference across stakeholder groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Overall, the total number of male respondents was 38 (51%) as compared with 37 females (49%) for the cumulative gender of respondents, indicating an almost equal gender distribution. Male respondents (54%) outweighed females for the marine resource managers and the operators group, which was 100% male, while females were more prominent for the visitor group (58% compared to 42% male).

Overall, the 28–37 age group accounted for the highest percentage (31%), while the 18–27 age group accounted for the smallest percentage of (16%) of respondents. Almost half (46.2%) of respondents in the marine resource managers and experts group were in the 28–37 age group, while in the visitor group, the largest percentage (31%) was recorded in the 38–47 age category. The tour operator group was dominated (75%) by respondents in the forty-eight and over age group.

Generally, all respondents attained formal education with the majority (77.3%) having tertiary-level education. Tertiary-level education dominated the visitors group (82%) and the marine resource managers and experts group (77%). Secondary school level education dominated the tour operator group (75%).

Statistically significant demographic differences were noted across the three stakeholder groups (Table 2). Surveys indicated gender differences between the visitors and the operators group only (p-value = 0.002). A statistical difference in the age distribution across stakeholder groups (p = 0.014) was noted with differences noted between the marine resource managers/experts and operators (p = 0.006) and visitors and operators (p = 0.007). Results also indicated a statistical difference in education levels between the operators group and the marine resource managers/experts group (p = 0.0009) and the tour operators group and the visitors group (p = 0.0003).

Stakeholders’ indication of socioeconomic activities and conflicts

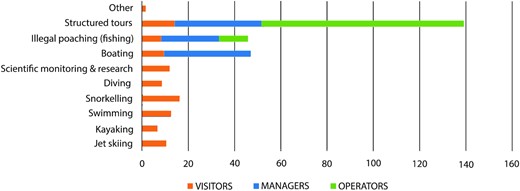

Stakeholder responses indicated a variation in their indication of the main types of activities taking place in the Marine Park (Figure 2). Overall, a total of ten socioeconomic activities were identified. Across all stakeholder groups, two activities were commonly identified, structured tours (87.5% for operators, 37.5% for marine resource managers and experts, and 14% for visitors) and illegal poaching (12.5% for operators, 8% for visitors, and 25% for marine resource managers and experts). Boating was another main activity identified by managers and tour operators. The visitors group also identified snorkelling, swimming, and scientific monitoring as other main activities. Kruskall–Wallis tests indicated a statistical significance in socioeconomic activity type identified by stakeholder groups with the visitor group accounting for the difference (marine resource managers versus visitors p = 0.004

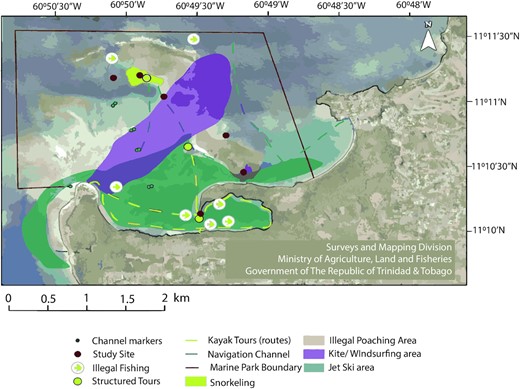

The spatial analysis revealed a significant level of overlap with respect to the socioeconomic activities taking place in the Marine Park (Figure 3). Two of the three areas for structured tours were also utilized for other socioeconomic activities. The Nylon Pool was utilized for both kite/windsurfing and jet ski activities, while Sheerbird’s Point, a site for structured tours, was also used for jet ski activities. There was also considerable overlap in the jet ski and kite/windsurfing areas. Results also indicated that navigation routes (for vessels) traversed the snorkelling, structured tours, jet ski, kayak areas, and recreational activity areas.

Spatial extent of socioeconomic activities in the Buccoo Reef study area (as identified by tour operators and local experts).

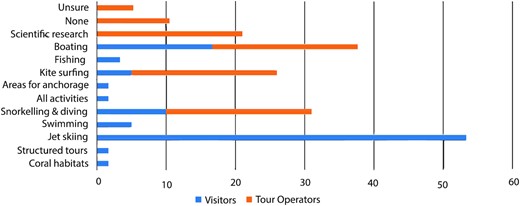

Conflicts between various users of the Marine Park were also identified by two stakeholder groups: visitors and tour operators with jet skis (operating near bathers) identified as the main source of user conflicts (Figure 4). For the visitors group, a total of 51 responses were obtained for the question which asked if any user conflicts were observed, with 48% indicating “yes” and 52% indicating “no.” Of the respondents who cited conflicts, 81% identified jet skis while 17% cited poachers, and 2% cited boaters or boats. In the tour operators group, 100% of respondents cited conflicts with jet skis, while one respondent also indicated conflicts between reef tour boat operators when soliciting passengers to select a specific vessel for tours.

Zone types for the Marine Park identified by two stakeholder groups.

Stakeholders’ perception on MSP and identification of zones

The responses of stakeholder groups indicated a need for MSP to better manage the Buccoo Reef Marine Park (Table 3). While the largest percentages in the marine resource managers and visitors groups felt that it was “completely necessary” (75% and 61%, respectively), the majority (63%) of respondents in the tour operators group felt it was “somewhat unnecessary.” Similar figures were reported when visitors were asked if they were more likely to return to the Marine Park if a zoning scheme was implemented as 78% (n = 43) were likely to return, 20% (n = 11) were unsure, and 2% (n = 1) were not likely to return. The respondent's level of education in the marine resource managers group was not found to be a determining factor (p = 0.195) in perceptions on the need for a MSP.

Stakeholders’ perceptions on the need for a marine spatial plan to manage the study area (Buccoo Reef Marine Park).

| % of Stakeholder Perception . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for MSP . | Completely unnecessary . | Somewhat unnecessary . | Neutral . | Somewhat necessary . | Completely necessary . |

| Marine resource managers and experts (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 |

| Visitors (n = 55) | 10.5 | 1.75 | 7.01 | 19.2 | 61.4 |

| Tour Operators (n = 8) | 0 | 62.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 0 |

| % of Stakeholder Perception . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for MSP . | Completely unnecessary . | Somewhat unnecessary . | Neutral . | Somewhat necessary . | Completely necessary . |

| Marine resource managers and experts (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 |

| Visitors (n = 55) | 10.5 | 1.75 | 7.01 | 19.2 | 61.4 |

| Tour Operators (n = 8) | 0 | 62.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 0 |

Stakeholders’ perceptions on the need for a marine spatial plan to manage the study area (Buccoo Reef Marine Park).

| % of Stakeholder Perception . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for MSP . | Completely unnecessary . | Somewhat unnecessary . | Neutral . | Somewhat necessary . | Completely necessary . |

| Marine resource managers and experts (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 |

| Visitors (n = 55) | 10.5 | 1.75 | 7.01 | 19.2 | 61.4 |

| Tour Operators (n = 8) | 0 | 62.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 0 |

| % of Stakeholder Perception . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for MSP . | Completely unnecessary . | Somewhat unnecessary . | Neutral . | Somewhat necessary . | Completely necessary . |

| Marine resource managers and experts (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 |

| Visitors (n = 55) | 10.5 | 1.75 | 7.01 | 19.2 | 61.4 |

| Tour Operators (n = 8) | 0 | 62.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 0 |

A significant variation in the zone selection was noted between the tour operators and visitors group (Figure 4). The visitors group identified a total of ten zones, while the tour operators identified four zones. Jet skiing was identified by most visitors (53.3%) with much fewer respondents for boating (16.67%), snorkelling and diving (10%), fishing (3.3%), structured tours (1.6%), and coral preservation zones (1.6%). Equal numbers of respondents from the tour operators group identified snorkelling and diving, kitesurfing, and boating, and scientific research (21%) for zonation 10.5% indicated that no zones were required while a small percentage, 5.2% were unsure. Overall, only three zone types (snorkelling/diving, boating, and scientific research) were common between the two stakeholder groups. A Mann–Whitney test determined statistical differences in zone type selection by tour operators and visitors (two-tail, p = 0, and a z-score of 4.997).

Discussion

Implications of multiple and overlapping socioeconomic activities

The study illustrated the spatial complexities of socioeconomic uses of the Marine Park, which are commonplace in many other multiuse protected areas (Breen et al., 2021; Kyvelou and Ierapetritis, 2021; Li et al., 2021). Despite the small sample size, which is noted as a limitation of this study, the responses from stakeholder groups indicate the variation in perspectives and its implications for management. The types of socioeconomic activities identified in this study are recreational (and for profit) in nature (similar to studies conducted by Smallwood et al., 2012) except for illegal poaching and illegal fishing, which are undertaken for economic benefit. The provision of this array of recreational activities; structured tours, kite- and windsurfing, kayaking, snorkelling, and jet skiing, by tour operators suggests the popularity of the area, as a constant influx of customers would be required to support these sectors.

Multiuse MPAs have been described as mechanisms to both create and reduce conflicts (Beuret et al., 2019; Millage et al., 2021). Stakeholder engagement and direct observation indicated that the overlapping spatial extent of socioeconomic activities is a source for user conflicts, the most notable of which occur between users of motorized crafts, specifically jet skis, and other users (bathers and snorkelers) in the marine space. Interestingly, jet ski use has been prohibited within the Marine Park since 2011 with an exception for transit purposes. The speed and manoeuvrability of these crafts may contribute to both their popularity and ability to enter the park initially undetected by patrol officers.

Furthermore, multiple uses of the Marine Park can also be an indication of challenges in maintaining natural habitats and ecosystems (Cavada-Blanco et al., 2021). Local experts have addressed this issue with respect to potential ecological damage to a popular jet ski area, the Bon Accord Lagoon, and have lobbied for enforcement of the jet ski prohibition in the area. To address the ecological impact of motorized crafts, studies have recommended education programmes for boaters, the introduction of legal mechanisms for environmental protection, and carrying capacity studies to determine the appropriate number of crafts that should operate in sensitive areas (Carreño and Lloret, 2021). From a management perspective, jet ski use is concentrated only in certain areas within the MPA, thus making it easier to focus enforcement in these areas.

The issues faced in Tobago’s MPA are commonplace in several MPAs in the Caribbean region, including St. Lucia’s Soufriere Marine Management Area (SMMA) and Antigua’s North East Marine Management Area (NEMMA) (Car and Heyman, 2009; Baldeo et al., 2012). Best practices from successfully managed MPAs, including the Bonaire National Marine Park, the Hol Chan Marine Reserve, and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, such as zoning schemes, enforcement structures, user fees, and other sustainable financing mechanisms and stakeholder inclusion mechanisms can be refined for the Tobago landscape.

Management strategies

Facilitating multiple uses may either be impractical or difficult to achieve; however, one benefit of this study lies in the simplicity of resolving user conflicts in the Marine Park due to existing legislative and policy frameworks. A likely reason for the occurrence of prohibited activities is a lack of consistent enforcement, particularly during hours outside the scheduled reef patrols. As such, management strategies must be designed to address these specific challenges, thereby ensuring that only permitted socioeconomic activities occur in the space. This will also result in the added benefit of a reduction in the negative environmental and ecological impacts associated with jet ski use and illegal poaching, particularly within sensitive areas of the park.

There is also a novel opportunity for Tobago to lead the national MSP agenda. Tobago, relying primarily on tourism as compared with Trinidad’s focus on the oil and gas industry, has legal jurisdiction through the Tobago House of Assembly Act (THA Act 40 of 1996) to develop its own MSP framework. As in the case of Barbuda, another twin-island state, this MSP framework should be stakeholder-driven (Johnson et al., 2020). Stakeholders in the Tobago landscape would include reef tour and other tourism service providers, government agencies, educational institutions, fisherfolk, NGOs, local communities, and visitors. This agenda is also supported by recent gains in the management of Tobago’s blue economy with respect to ecological protection, namely the Man and the Biosphere UNESCO designation for north-east Tobago, Castara’s selection to participate in UNWTO's (United Nations World Tourism Organization) best tourism village upgrade programme, and Blue Flag certification for several beaches and tour boats (Moses-Wothke et al., 2021)).

To further enhance the management of the MPA, a greater focus should be placed on conducting scientific studies. Given the frequency with which the area is utilized, willingness-to-pay studies can serve as a tool to potentially introduce user fees to access the park. User fees are a common financial mechanism to support MPA management (Casey and Schuhmann, 2019; Schuhmann et al., 2019; Steneck et al., 2019). Similarly, carrying capacity studies, particularly for frequently utilized areas such as Sheerbird’s Point, the Nylon Pool, and Coral Gardens, should be considered to guide management towards ecological protection (Navarro, 2019; Cockerell and Jones, 2021). Another key consideration should be on identifying or quantifying the impact of land-based activities, particularly agricultural practices, coastal land development, and wastewater treatment on the reef ecosystem (Burke et al., 2008; Da Costa, 2010; Lapointe et al., 2010; Mycoo, 2020).

It must be noted that substantial changes with respect to the management of the park occurred after the socioeconomic assessment of this study, between 2020 and 2021. Changes included the introduction of access permits, subject to terms and conditions, to enter the park, opening and closing hours, and the establishment of stakeholder committees to guide management of the area. However, at present (2023), these changes are not imposed. Enforcement mechanisms, while still insufficient, have been strengthened since 2020, as prior to this period, reef patrols were not in existence for several years. Based on this information, it is expected that stakeholders should notice a reduction in illegal fishing, poaching, and the use of jet skis in the park and this has been substantiated by recent anecdotal evidence and expert opinion. Furthermore, park closures due to COVID-19 occurred at three-time intervals during the 2020–2021 period with each interval lasting up to three months. Research shows that periods of closure positively impacted protected areas and result in healthier ecological habitats (Gao and Hailu, 2018; Koh and Fakfare, 2019; Debrot, 2020).

Enhanced management will also impact the MSP as some activities, namely illegal poaching, fishing, and jet skiing, will be eliminated due to greater enforcement, making it easier to zone the park as fewer activities will be permitted. Zoning would also ease pressures on management and provide an improved and safer tourism product (Day et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2020).

Stakeholder awareness: towards a common vision

A key finding from this study is that stakeholders have an elevated level of awareness of the range of activities that take place and an understanding of key ecological features and their importance. These findings may be due to the level of education and the economic impact of activities that are known to cause ecological harm (such as poaching and the use of jet skis).

The findings of the socioeconomic assessment also have important implications for the next phase of the wider project, which is the development of a marine spatial plan based on socioeconomic, ecological, and temporal assessments. Results indicate a substantial level of stakeholder support for a MSP initiative, a factor that can determine the success of this project. Several studies address the need for early stakeholder engagement throughout all phases in the development of marine spatial plans (Giakoumi et al., 2018; Yates, 2018; Santos et al., 2019). Studies have documented successful applications of this approach in fisheries management (Thiault et al., 2017) and coastal zone management (Tailor et al., 2021). In the case of the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, this early engagement indicates the likelihood that visitors and marine resource managers will support the MSP, while some level of resistance can be expected by tour operators.

Therefore, efforts must be tailored to educate tour operators on the ecological importance of the area and highlight the connection with economic gain, for instance, the provision of shoreline protection services that support beach and ecotourism, the link between fish and coral abundance and the quality of glass bottom boat tours, and the aesthetic appeal that healthy ecosystems provide for tourism activities (Marcos et al., 2021). This is no easy task, as shown in the work done in Barbuda and other islands that have sought to balance economic benefits and ecological priorities (Johnson et al., 2020). Emphasis can also be placed on utilizing visitors as agents of change, which will in turn encourage support from tour operators as they seek to satisfy the demands of their customer base (March et al., 2022). The importance of stakeholder engagement cannot be underscored, as evidenced by previous studies where it was considered a crucial factor affecting MPA success, and equally, its absence was the most significant factor influencing failure (Giakoumi et al., 2018; Di Franco et al., 2020; Katikiro et al., 2021).

Conclusion

This research encompassed a wide-ranging assessment of the socioeconomic activities in the Buccoo Reef Marine Park, using stakeholder questionnaires, interviews, and direct observation. Previous studies highlight the importance of stakeholder engagement in the successful development and implementation of MSPs, and as such, this study focused on obtaining stakeholder perspectives on socioeconomic activities, conflicts, and the need for a MSP for the Park. It is expected that this socioeconomic assessment will allow for stakeholder inclusion and support of the MSP initiative, which will consider the results of an ecological and temporal change assessment.

All stakeholders interviewed for this project have been identified as influential and important and include the broad categories of marine resource managers and experts, visitors, and tour operators for several types of tours/recreational activities. It should be noted that while some differences were observed in the perspectives across stakeholder groups, considerable overlap suggests that a common vision can be attained for the use of the park and the zoning of activities. Additionally, local knowledge was garnered on temporal changes in the Marine Park, changes to the tour structure, and anthropogenic threats. This is another consideration for the development of the MSP.

These findings can also provide a useful basis for evaluating and improving management strategies. For instance, the focus should be placed on enhanced enforcement strategies since the main source of user conflicts, jet skis, is in fact a prohibited activity. It also suggests that one stakeholder group may require more attention to increase levels of awareness and eventually support for the changes required for the MSP. This socioeconomic assessment is critical in designing a MSP that will be supported by stakeholders and encompass a wide range of acceptable activities that ensure economic gain while reducing environmental impacts.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the following agencies and individuals for their contributions to this study. The Tobago House of Assembly, Division of Food Production, Forestry and Fisheries for granting the permissions required to undertake the overall project, Mr Omari McPherson, Mr Dereem Anderson, and Mr Kirth McPherson for their assistance in the field and all persons, including tour operators, marine resource managers, and experts for participating in the questionnaire component.

Author contributions

Author 1: S.M.P. (Conceptualization, design and methodology, Perform experiments/collection of data, Analysis of findings, and Drafting & revising the manuscript), Author 2: R.G. (Conceptualization, design and methodology, Perform experiments/collection of data, Analysis of findings, and Drafting & revising the manuscript), Author 3: D.R. (Conceptualization, design and methodology, Perform experiments/collection of data, Analysis of findings, and Drafting & revising the manuscript), and Author 4: A.P. (Conceptualization, design and methodology, Perform experiments/collection of data, Analysis of findings, and Drafting & revising the manuscript).

Conflict of interest

None declared

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Funding

No external funding was provided for this project.