-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kelsey Archer Barnhill, The deep sea and me, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 79, Issue 7, September 2022, Pages 1996–2002, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsac147

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In this perspective, I reflect on my path to the deep sea, a field, and ecosystem that are often hard to access. Growing up in a coastal town, the seashore was my playground, but it was not until I was 18 years old that I was inspired to be a deep-sea scientist. From a Bachelor of Arts in the United States to a Master of Science in Norway and currently a PhD programme in Scotland, I have let the deep sea lead my career path with the help of supportive mentors and peers. Now, as an early career scientist with over 100 d of at-sea experience working on science, mapping, and outreach teams, I highlight the key moments that allowed me to enter the field. Looking to Horizon 2050, I share my goals for the future of deep-sea science. I hope to see a new age of ocean exploration with an increased commitment to advancing technologies, a more diverse, inclusive, and international team offshore and onshore, and a more engaged public through placing a larger focus on the deep sea in educational curricula.

Shaped by the sea

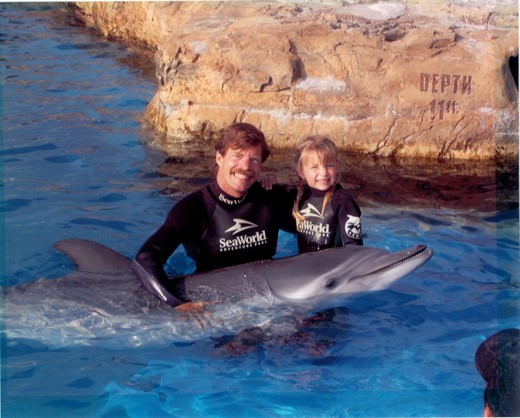

I grew up as an only child living <5 min by car away from the beach in a small coastal town called Cardiff-by-the-Sea, California. I spent my childhood building sand castles and looking for rocks and shells to place in my sandy pockets (Figure 1). My parents took me to the beach to witness plankton blooms glowing in the moonlight, watch dolphins wave riding with local surfers, ogle at sea lions lazily sunning themselves in the sand, and squat down to search tide pool crevices for sea stars. I benefited from the many educational attractions San Diego offers, having access from a young age to learn about sea life at the Birch Aquarium, the Nat, The San Diego Zoo, and SeaWorld, among others. SeaWorld San Diego was a personal favourite, with some of my earliest memories focused on my frequent visits with J.J., the orphaned grey whale calf successfully rescued, rehabilitated, and released after 14 months in captivity (Ponganis and Kooyman, 1999). I counted down days for my sixth birthday when I was finally old enough to don a wetsuit and swim with the SeaWorld trainers and dolphins (Figure 2).

Kelsey with a seaweed necklace at Cardiff State Beach in 2001.

Kelsey and her father, Barney Barnhill, participating in a dolphin encounter at SeaWorld San Diego in 2000.

For all my exposure to the sea, by the time I was an 18-year-old community college student, I knew one thing for certain: I was not going to pursue a STEM career. In high school, I struggled in math and science courses whilst soaring through the humanities with flying colours. With this track record, it was only natural to consider the social sciences as my path forward at university. I sampled courses in history, anthropology, languages, and theatre before settling on international relations as my major. The US higher education system usually requires students to take general education requirements across core subjects to graduate, regardless of the programme (Filsecker, 2012). From speaking with other students, I discovered that the perceived easiest path to completing the science requirement was to enrol in the oceanography course.

I entered the classroom set to finish off my science requirement nice and early in my degree before heading on to pursue a career in foreign affairs and diplomacy. However, the sea had other plans for me. During the first week of class, the instructor showed us a TED talk by Professor Robert Ballard (Ballard, 2008). As he enthusiastically spoke about the importance of deep-sea exploration with colourful videos of the depths playing behind him, I was enthralled and shocked to learn how little we knew of the world around us. By the end of the talk, I knew I wanted to be a deep-sea scientist.

Headstrong and set on a new path at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I first had to overcome my fear of failure. Instead of entering into a programme in the familiar humanities where I had historically succeeded, I risked it all, knowing I would likely suffer a lower GPA to get on track for my dream career. Without the self-imposed pressure to earn full marks in everything, I felt freer in my coursework. Fuelled by my refusal to accept a geological concept may be beyond my reach, I pulled the first all-nighter of my life to study for a test in mineralogy. Papers spread across the floor of my dorm room in an order only I could make sense of, I repeated the same worksheets over and over until halfway through one sheet at 2:00 a.m. I saw the pattern and everything clicked. With 2 h of light sleep and an early morning exam later, I proudly left with an A-. The desire flowing within me to succeed in the field pulled me away from the fear of failure and, for the first time in my life, gave me the chance to just learn. I walked into the classroom each morning feeling curious and truly wanting to grasp the concepts taught. This was new for me. In high school, I solely focused on the result of getting a high grade. This new outlook did not have me graduating summa cum laude, or with an invitation to the coveted Phi Beta Kappa honours society, but I did leave with a Bachelor of Arts in Geological Sciences with a Minor in Marine Sciences and an excitement for the future.

Exposure to the deep sea

As an undergraduate, I was eager to get to sea and do research first-hand. I jumped at the opportunity to spend time at University of North Carolina's Institute of Marine Sciences, taking an entire semester of marine-focused classes and participating in field work. Living on Duke University Marine Lab's island, I spoke to Professor Cindy Van Dover and asked if there was any way to become involved in deep-sea science. While there were no opportunities open for undergraduates in her lab at the time, she told me I should apply to sail as an ocean science intern on board the E/V Nautilus.

It was the first I had heard about shipboard training opportunities. Scanning the website (https://nautiluslive.org/), my heart raced as I became immensely excited and threw all my efforts behind writing the best application I could. During my interview, sweat seeped through my ocean blue blouse as the opportunity meant so much to me. My passion and eagerness to join the expedition must have shone through, as I was fortunate enough to be selected to sail on two cruises that summer.

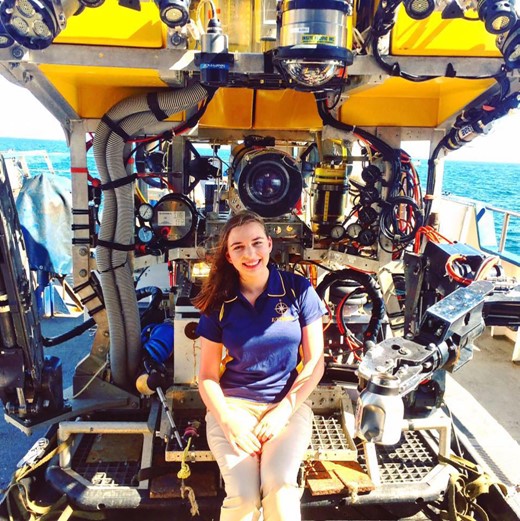

On board, I found I no longer simply wanted to do deep-sea science; I needed to do it. I came alive. Everything made sense. I found I love spending time at sea, and if I could be on a boat constantly, I would. Where a 03:40 a.m. wakeup time would be my nightmare in any other scenario, at sea, I did not mind the pitch-black start for my 04:00 a.m. shift. Long hours and a flexible schedule where the Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) launch and recovery dictates your schedule more so than the sun, were easy for me to adapt to. Endless energy seemed to course through me as I could not believe I was getting to contribute to furthering live deep-sea ocean exploration (Figure 3). During the dives, I was drawn to the colourful and diverse cold-water corals and their associated biodiversity. I could not get over the stunning coral gardens in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. As much as I had been drawn to the deep sea, I now felt the similar pull towards these corals.

The day I had been anxiously awaiting came in the form of a small boat transfer. The E/V Nautilus stood still as dynamic positioning allowed for a small boat to deposit the organization's president Dr Robert Ballard on board. I could not have been more star-struck. The next morning I was logging data during an ROV dive when Bob joined me in the control room. My eyes widened as the man who inspired me to pursue a career in deep sea occupied the seat next to me as the team explored paleoshorelines off the California coast.

Sharing the sea

One of my favourite things about the deep sea is getting to share it with others. The E/V Nautilus does an excellent job sharing deep-sea science with the general public, and this was an aspect I was eager to be involved in during my time at sea. I loved sharing our discoveries with tens of thousands of viewers, highlighting information about what we were seeing, the goal of the ROV dive, and my path to joining the expedition. Whenever we were in port, I enjoyed assisting with ship tours for local school groups and community members. On the galley's whiteboard, I wrote my name next to as many ship-to-shore live video calls with schools and museums as I could possibly fit into my day. I loved answering questions from the public: What was the coolest thing I had seen in the ocean? (A Mola mola! ) Had we discovered any new species? (Possibly, but it can take years to describe a new species.) What did we eat for breakfast? (Eggs and pancakes.) Did we miss our friends and family? (Sometimes, but I brought my teddy bear on board.)

I am so fortunate for the opportunity the E/V Nautilus provided for me. This scheme along with others such as NOAA's Explorer-in-Training (https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/okeanos/training.html) and Schmidt Ocean Institute's Student-at-Sea (https://schmidtocean.org/apply/student-opportunities/) are phenomenal programmes that allow students to join expeditions and gain at-sea skills. I would not be where I am today without that at-sea experience. For me it was an added bonus to not merely receive training but also be able to actively contribute to research while learning. The inclusive team on board were supportive and made me feel appreciated through acknowledging my contributions, such as when I was asked to join as a co-author on an article for the annual Oceanography Supplement (Bell et al., 2017). This output gave me my first scientific writing experience and jump-started the publication portion of my CV. When appropriate, collaborating with and including early career scientists (ECS) on outputs helps them learn and can have positive impacts on their careers (Bozeman & Corley, 2004).

Mastering the sea

I said my tearful goodbyes as I parted ways with my friends and colleagues I had met during the cruises. I left the ship knowing without any semblance of a doubt that I would be back at sea soon. This was where I was meant to be. The one thing I did not know was how to get there. After my experience at sea, I knew I wanted to shift towards the biological side of marine sciences. Unable to find an affordable master's programme in the United States that would allow me to work with the gorgeous cold-water corals I had been so drawn to, I looked for opportunities abroad. The free tuition and intriguing curriculum at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences took me to Norway.

The move abroad was just what I needed. Whereas in the United States my courses would often start with explaining why climate change was in fact real and man-made, in Norway this discourse was bypassed, allowing us to get straight into the topic. Instead of weeks spent looking at past climate trends to show evidence to support climate change, accepting the consensus meant we were able to immediately start discussing the impacts and the mitigation strategies we could use to improve ecosystems. I fully embraced the culture, learning the language, joining student societies, and working part-time jobs.

During my master's degree, I spent my summer field placement at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology's Coral Reef Ecology Lab. With the support of my supervisors, Professor Ian Bryceson and Dr Keisha Bahr, I was able to strengthen my scientific skills, resulting in two scientific publications. First, I followed up on a survey initially done in 2000, which had not been revisited to compare benthic cover and coral resilience at Malauka`a fringing reef (Barnhill and Bahr, 2019). After finding variations in coral and algal cover across the reef, I conducted a reciprocal transplant experiment to determine if growth rates varied between sites, and if so, than whether environmental conditions or colony genetics were responsible (Barnhill et al., 2020). I focused my Master of Science in Tropical Ecology and Management of Natural Resources on shallow coral reefs, hoping I could combine my education with my at-sea experience to get me closer to my goal.

My strategy worked. Whilst attending the Reef Conservation UK 2018 conference, I met my now primary PhD supervisor Dr Sebastian Hennige. As soon as he began a presentation on his research into ocean acidification impacts on cold-water coral reefs (Hennige et al., 2020), I knew I wanted to work with him. After strategically placing myself by the sandwiches during the lunch break to introduce myself and express my interest, I began the path towards applying for a PhD. After not making it through upon my first attempt, my second round was successful and I started my PhD in Deep Sea Ecology at the University of Edinburgh in January 2020. Finally, I could look forward to spending all my time focused on the deep sea and cold-water corals.

Back to sea

Just as COVID-19 impacted the entire world, it impacted the research of my lab group too. As our research group lead, Professor Murray Roberts is the project coordinator of the EU Horizon 2020’s iAtlantic (https://www.iatlantic.eu/, grant agreement No 818123), COVID's impact on this project was of particular concern. The flagship iMirabilis cruise scheduled for 2020 was already pushed back by a year and then ECS from project partners in South Africa and Brazil were prevented from joining the 2021 rescheduled iMirabilis2 due to variant-imposed travel bans. iMirabilis was written into the European project as a training and capacity building cruise with a focus on outreach (Orejas et al., 2022). To deliver on this commitment in the wake of COVID-19, the role of an on-board outreach liaison was created and I was selected to fill this position.

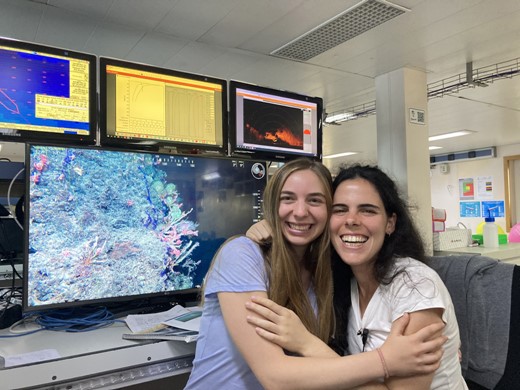

Nothing had ever felt so right as sailing on the R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa as both a member of the scientific ROV team and as the on-board outreach liaison (Figure 4). I was able to partake in deep-sea science and share my passion for it with others (Figure 5). Each day, I tracked down fellow members of the science team to give me their daily updates to fill in the 20 blog posts I authored (https://www.iatlantic.eu/imirabilis2-expedition/blog/). I had fun thinking of the most useful educational videos to share with ECS about conducting research at sea. I felt accomplished seeing the social media engagement numbers spike as I ran the iAtlantic project's Twitter (https://twitter.com/iAtlanticEU), Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/iatlanticeu/), and Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/iAtlanticEU). However, by far the most impactful and rewarding action on board was running the “Ship-to-Shore Buddies” scheme. I involved the other on board ECS to participate in the scheme and actively recruited on-shore buddies to join the expedition virtually. In total, 18 students and ECS joined the programme as official buddies. These participants connected to the cruise from their desktops in South Africa, Brazil, Ghana, and Cabo Verde. I, with the help of other ECS on board, provided daily updates to the on-shore buddies via a WhatsApp group, sending and receiving >250 messages during the expedition. When at-sea communications allowed, I also scheduled 1-h weekly Zoom calls to speak with the buddies live from the ship. During these calls, we were able to share sneak peeks of training videos, discuss life at sea, and give the on-shore participants the opportunity to request trainings and ask any questions they had for the on-board team. I had found my niche in making deep-sea expeditions more accessible and inclusive to ECS across the globe. Allowing 18 more students than the number of berths permitted to virtually sail on the expedition is the accomplishment I am most proud of thus far in my career.

![The iMirabilis2 at-sea team aboard the R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa in 2021 [Picture: iMirabilis2 Team].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/icesjms/79/7/10.1093_icesjms_fsac147/1/m_fsac147fig4.jpeg?Expires=1749825159&Signature=eZgdpN9NTaxaigclgZuNMmAws-~TeE2Od6eAdGQ1TEv6q6IsJnJ2nrR08G9Jro3Ui6XjR47i4maCBbMY1JY6YzwuZTCxFcB-XIjCvYPqsRPDq2zIjy7NuG9bsiz3aB0IjzoInjNfL5K7qM7ssd~w55HYR6uikGFvIIDcwOT94sX4jIRRUx6WFKvHzyhz-LiAoCyVtj7YJe8Si8BgS4ZFlaioLv~Ihc7YGfbqC3tkWkinmkUes-vhSlTHtPuPbuGjZhtv417C5-URuA5bMf57tLu9fDQ7Xg3NY7ZC4GJK6ksmr7CkzPLYUK7aPsLQi8R6l90OUsq9SbM4I01GQxnzgQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

The iMirabilis2 at-sea team aboard the R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa in 2021 [Picture: iMirabilis2 Team].

Kelsey sharing in the excitement of deep-sea science during an ROV dive with her friend and fellow ECS, Beatriz Vinha, aboard the iMirabilis2 cruise on R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa in August 2021.

Youth, ECS, and the sea

I am lucky to be in a PhD programme with so many engaged and kind people. My cohort have supported me through the ups and downs of the PhD. During COVID lockdowns, we would meet up at the normal 11:00 coffee break time virtually on Teams. We arranged game nights and pub quizzes over Zoom. This is how I believe ECS should interact with one another. I never feel competition from my peers; we all support each other and rely on each other when times get tough.

Similarly, I have benefited from being involved with ECS networks within the wider marine science community. I am an active member of the All-Atlantic Ocean Youth Ambassadors (https://allatlanticocean.org/view/atlanticambassadors/introduction), One Ocean Hub Early Career Researchers (https://oneoceanhub.org/), iAtlantic Fellows (https://www.iatlantic.eu/our-team/iatlantic-fellows/), and Deep Ocean Early career Researchers (DOERs) (https://deep-ocean-observing-strategy-ut-austin.hub.arcgis.com/pages/doers). These networks have not only provided me with a support network but have also opened up opportunities for me on occasion.

Through the One Ocean Hub ECR network, I was given the opportunity to speak at the 16th UN Climate Change Conference of Youth (COY16) in the run-up to the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). Through the All-Atlantic Ocean Youth Ambassadors, I was given the opportunity to attend COP26 in person in Glasgow via the World Ocean Network and present at the virtual ocean pavilion (https://cop26oceanpavilion.vfairs.com/). These networks gave me a platform at COP26 to share my ideas about the future of the deep sea and to meet other youth ocean advocates from around the world. The speaking engagements also allowed me to be noticed by future collaborators. Following my presentation on increasing ocean exploration to ensure children's rights to a healthy ocean, I was contacted by Articolo12 to film a short video on a similar topic, which is featured in the UN Environment Programme's online training for young people called “Our Rights, Our Planet” (https://leap.unep.org/ourrights-ourplanet/your-rights.html).

COP26 was slated to be a “blue COP” with the ocean in focus, but in my experience, it was not blue enough. The ocean is in the spotlight more now than ever before with the launch of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, but it is still often overlooked in negotiations with the deep sea particularly left out.

The deep sea and Horizon 2050

I cannot look forward to Horizon 2050 without considering how my path to the deep sea has influenced my vision for the future. Throughout my career, I have been impressed with the technology used to learn more about the deep sea. By 2050, I hope to see technological advances to reach greater depths, increase exploration, further research, and ensure environmental protection pledges are met. My nationality has allowed me opportunities to apply for at-sea internships limited to US and Canadian citizens. As the ocean is a widely global asset, I hope to see more opportunities for international collaborations, at-sea trainings, and virtual involvement to increase inclusion. I feel so fortunate to have found my calling in the deep sea. To ensure we have a diverse and informed future generation of deep-sea researchers, I would like to see increased efforts in incorporating the deep sea into classroom curricula and museums.

The lack of deep-sea exploration is a societal issue. Children have the right to a healthy environment through the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and that includes a healthy ocean. Through this lens, I often find myself wondering about possible consequences of not having explored much of our deep sea.

How can we conserve environments for future generations if we do not even know what is there?

What knowledge have we missed out on as our exploration efforts were too late?

How many deep-sea species have already gone extinct?

How much has climate change impacted the deep sea prior to when we first began monitoring?

How can we understand and predict future changes without having completed basic exploration?

There is much more to learn about the deep sea, including basic exploration in order to ensure adequate protections to preserve the ecosystems. To do so, we need a larger budget allocated to ocean exploration. Further, we must commit to having more baseline data and long-term monitoring sites to increase our comprehension of these ecosystems.

The wheels are already in motion to support an increase in deep-sea exploration towards 2050. The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030’s goal to map the global seafloor by 2030 is one such initiative pledging to drive deep-sea science forwards (Mayer et al., 2018). I hope to see more ocean exploration pledges with a focus on the deep sea as technologies advance, increasing the abilities of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV), ROVs, and Human Operated Vehicles (HOV) to explore the depths. However, pledges and intentions alone are not sufficient; we must follow through on these promises. In 2010, the Convention on Biological Diversity Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 committed to protecting 10% of the ocean by 2020 under Aichi Target 11. Coming in at 7.5% in December 2020, this target was not achieved (Brito-Morales et al., 2022). The new goal is set at 30% protection by 2030, often referred to as “30 by 30” (Report of the Open-Ended Working Group on the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework on Its Third Meeting (Part II), 2022). There must be more discussion about why the 10% commitment was not met to ensure 30 by 30 is achieved. We cannot expect diverse and healthy ocean ecosystems if we are unable to meet the promised protections.

The ocean is an international asset and resource so participation in ocean research should not be limited by nationality. Looking to 2050, I hope to see more global collaboration with researchers able to access funding for deep-sea work regardless of nationality/employer affiliation. By ensuring nationality does not affect participation, we will have increased diversity, which is proven to promote and advance science (Freeman & Huang, 2014). Once at sea, it is also crucially important to provide a safe and respectful working environment to promote inclusion (Amon et al., 2022).

I believe mentorship also has a role to play in increasing inclusion and diversity in deep-sea science. During my bachelor's degree, I was fortunate to interact with established researchers in the field who influenced my path and offered support. As such, as I advance in my career, I feel a duty to mentor those at an earlier stage than I am. As a PhD student, I have been a pen pal to primary school students through the Primary Science Teaching Trust's 'A Scientist Just Like Me' resource, participated in Q&As in classrooms, provided individualized advice to students who reach out to me on social media sites such as LinkedIn, and served as a Woman in STEM mentor at the University of Edinburgh. I enjoy connecting to and encouraging students, especially women, to pursue a STEM career if that is their goal. In addition to spending time as a mentor, I also participate in such schemes as a mentee. Last year, through the National Oceanography Centre's West P&I Seagoing Science Bursary, I was paired with two female deep-sea scientists and offered monthly mentoring sessions. I benefited from engaging in this bursary through discussing their career paths and receiving personalized feedback on my CV. Looking forward, I hope to see the continuation and further development of such schemes within the deep-sea community, such as the Deep-Sea Biology Society's mentoring network.

With the technology of today and that of the future, deep-sea research experiences should not be limited by the number of berths available on board. Telepresence and internet connection allow researchers to join along on cruises from their homes, providing more expertise than would be possible to have on board without this connection. I have joined Zoom calls both from a ship and from my home connecting to a ship hundreds of miles away. Looking to the future, I hope to see more opportunities for people to take part in ocean exploration virtually, such as the iMirabilis2 ship-to-shore buddy scheme. As technology advances, I hope so too will the possibilities for virtual trainings and experiences.

Finally, I would like to see educational curricula place more focus on the deep sea. I did not know there was an entire intriguing world hidden thousands of meters deep until I was 18 years old! We will have better and more diverse scientists if people are aware of the opportunities existing in this field. School systems and museums can help make deep-sea science more inclusive by featuring it in their repertoire. Connecting the public to the deep sea by making it relatable, as opposed to the scary unknown it is often portrayed as in media, will help push ecosystem conservation efforts (Jamieson et al., 2021). Deep-sea exploration creates a sense of wonder and discovery, often drawing comparisons to space exploration. We must take advantage of this interest by increasing educational outreach and along with it public support for the importance of exploration. Forget the 16th and 17th centuries, for the ocean, the true age of exploration is now.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Conflict of interest

Kelsey Archer Barnhill recieved an honorarium from Articolo12 for her involvement in UNEP's "Our Rights, Our Planet."

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to everyone who has helped me get this far in my career be that through collaboration, mentorship, or writing a letter of recommendation. Special thanks to the staff at UNC IMS, the team at Ocean Exploration Trust, Bushra Hussaini, Dr Keisha Bahr, Prof. Ian Bryceson, University of Edinburgh's Changing Oceans Research Group, the postgraduate research students and support staff at University of Edinburgh, and the entire team on board iMirabilis2 cruise for helping me to get to where I am today. Thank you to Dr Johanna N.J. Weston and Dr Howard I. Browman, who provided me with suggestions that greatly improved the quality of this work, and, of course, to my parents, for letting me go wherever the sea took me.

Notes

This is a contribution to the article series, “Rising tides – voices from the new generation of marine scientists looking at the horizon 2050”. This collection of articles was jointly developed by ICES Strategic Initiative on Integration of Early Career Scientists (SIIECS) and ICES Journal of Marine Science. The collection is dedicated to and written by early career scientists.