-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Bruce E Sands, Silvio Danese, J Casey Chapman, Khushboo Gurjar, Stacy Grieve, Deepika Thakur, Jenny Griffith, Namita Joshi, Kristina Kligys, Axel Dignass, Mucosal and Transmural Healing and Long-term Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 31, Issue 3, March 2025, Pages 857–877, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izae159

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Healing in Crohn’s disease is complex and difficult to measure due to incongruencies between clinical symptoms and disease states. Mucosal healing (MH) and transmural healing (TH) are increasingly used to measure clinical improvement in Crohn’s disease, but definitions of MH and TH can vary across studies, and their relationship to long-term outcomes is not clear. To address this knowledge gap, we performed a systematic literature review (SLR) to examine studies measuring MH and TH in Crohn’s disease.

Database records from 2012 to 2022 were searched for real-world evidence and interventional studies that reported the association of MH or TH with clinical, economic, or quality of life outcomes of adult patients with Crohn’s disease.

A total of 46 studies were identified in the systematic literature review, representing a combined patient population of 5530. Outcomes of patients with MH were reported by 39 studies; of these, 14 used validated scales for endoscopic assessment. Thirteen studies reported outcomes of patients with TH. Among studies that examined the outcomes of patients with and without MH or TH, patients with healing generally experienced improved clinical outcomes and reduced healthcare resource utilization, including fewer hospitalizations and surgeries and improved rates of clinical remission. This was especially true for patients with TH.

Mucosal and transmural healing are associated with positive long-term outcomes for adult patients with Crohn’s disease. The adoption of standardized measures and less invasive assessment tools will maximize the benefits of patient monitoring.

Lay Summary

Inflammation of the bowel wall is a key component of Crohn’s disease (CD). A systematic literature review (SLR) showed bowel wall healing was associated with positive long-term outcomes in CD, supporting healing as an indicator of disease control.

Achievement of mucosal healing (MH) and transmural healing (TH) are long-term therapeutic goals despite variations in their definitions and uncertainty in their association with long-term outcomes.

This systematic literature review (SLR) is the first to show that both MH and TH are associated with improved clinical outcomes including increased rates of clinical remission, decreased rates of relapse, and fewer hospitalizations and surgeries among patients with CD.

MH and TH may serve as useful indicators of clinical outcomes and disease control in CD. However, standardization and better education for clinicians will be paramount for the adoption of endoscopic monitoring of healing for CD.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the bowel wall (mucosal and transmural inflammation) that causes mucosal injury and intestinal damage, commonly resulting in complications like abscesses, fistulae, stricture, and intestinal obstruction.1–5 Long-term mucosal inflammation is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization, complications that may require surgery, and cancer.2,6 Symptoms of CD include abdominal pain, fatigue, diarrhea, fever, anemia, urgency, and weight loss,7,8 which negatively impact quality of life and social functioning, and slightly more than one-third of patients experience anxiety or depression.9 However, the clinical symptoms of CD are not reliable indicators of mucosal inflammation and provide an incomplete picture of disease control and response to treatment.3,5,10,11 This disconnect between symptoms and mucosal inflammation in CD necessitates monitoring of both for accurate assessment of disease severity.

Until recently, endoscopy has been the primary instrument used to assess mucosal inflammation in CD. Endoscopy is an invasive procedure with barriers to repeatability, including the need for bowel preparation, risk of complications, and high cost.12 Other measures used to assess CD are the biomarkers fecal calprotectin (FC) and C-reactive protein (CRP), although neither is specific to CD.10 While traditional endoscopy is limited in its ability to assess the small intestine due to the length and diameter of the small intestine, small capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy are gaining attention as alternatives to this traditional approach.13,14 Intestinal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are noninvasive options that provide high imaging accuracy, but tools to standardize the measurement of disease severity in CD require further validation.15,16

Adding to the complexity of treating CD, definitions of healing (mucosal or transmural) for the disease have not been clearly defined, and long-term, deep healing has not been taken into consideration until recently.17 The definition of healing in CD has been based on endoscopic or imaging examinations (eg, MRI, CT imaging, or intestinal ultrasound), which are used for diagnosis and treatment monitoring. Endoscopic healing has been recommended by the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IOIBD) as a long-term target for CD and is assessed through ileocolonoscopy, enteroscopy, or video capsule endoscopy for small bowel disease. In STRIDE II, the achievement of endoscopic healing was confirmed as an important therapeutic goal that enabled patients to achieve improved long-term outcomes.10 Historically, mucosal healing (MH) has been synonymous with endoscopic healing, indicating the resolution of mucosal inflammation and damage visible through colonoscopy and other endoscopies (video capsule, enteroscopy with single or double balloon, or spiral, and gastroscopy in the case of upper gastrointestinal [GI] involvement). Mucosal healing has been reported to be significantly associated with long-term clinical remission.18 More recently, definitions of MH increasingly incorporate histologic healing, although this is still not well-defined and lacks agreement among clinicians and experts.19

Increasingly, transmural healing (TH), which represents healing across all layers of the bowel, has been recognized as an important clinical outcome with long-term benefits, since CD involves inflammation throughout the intestinal wall and not just in the mucosa.20–22 In the CALM study, deep remission (defined as “endoscopic remission, clinical remission, and no steroid use”) correlated with TH and was associated with lower rates of disease progression over time.18 The IOIBD’s STRIDE initiative recommended in their 2021 treat-to-target strategies for clinical practice that TH be used to assess the depth of remission but did not recommend it as a formal target since the data were still limited.10

Despite recommendations for MH and TH as treat-to-target goals, they are infrequently implemented in clinical practice, perhaps because of the limited data on their importance for long-term outcomes in CD.18 Both MH and TH may change the natural course of CD by reducing inflammation that would normally lead to structural damage to the bowel and increase the risk of surgery, hospitalization, or long-term complications. However, a clear connection between MH and TH and potential clinical benefits has not been firmly established. The objective of this study was to examine how MH and TH relate to long-term clinical, economic (eg, healthcare resource utilization [HCRU]), and quality of life outcomes among patients with CD.

Methods

A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted following the principles outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,23 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Healthcare,24 and Methods for the Development of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Public Health Guidance.25 Cochrane, MEDLINE, EconLit, and EMBASE databases were searched on July 28, 2022, and the CRD database was searched on August 2, 2022, to examine the association of MH or endoscopic outcomes with improved long-term clinical and economic outcomes among adult patients with CD. A detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Real-world evidence studies and interventional studies (including randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) from within the past 10 years (2012 to July 28, 2022) were included. Systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses were included for the purpose of cross-checking and identifying primary literature sources through a bibliographic search. Publications were reviewed based on their titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 2) by 2 independent researchers, and disagreements were resolved by a third independent reviewer. Two reviewers then screened all citations and full-text articles, and any discrepancies in their decisions were resolved by a third independent reviewer. Data were extracted in a predefined extraction form by one reviewer and independently checked for accuracy and completeness by a second reviewer.

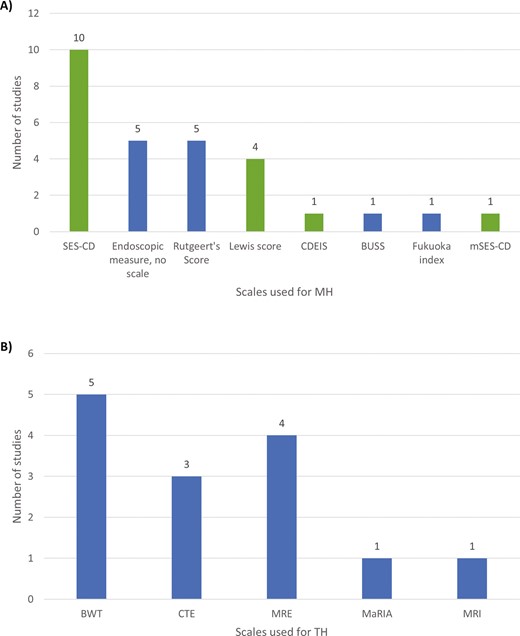

The SLR protocol captured the broadest inclusion of all definitions of MH, TH, and specific outcomes. This review focuses on the studies using validated scales to measure MH, including the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD),26 Modified Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (mSES-CD),27 Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS),28 and Lewis score.29 Among the included studies, modalities such as CT enterography (CTE), magnetic resonance enterography (MRE), and MRI were used to monitor TH, with specific measures or scales including bowel wall thickness (BWT) or the Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity (MaRIA) scale.

Results

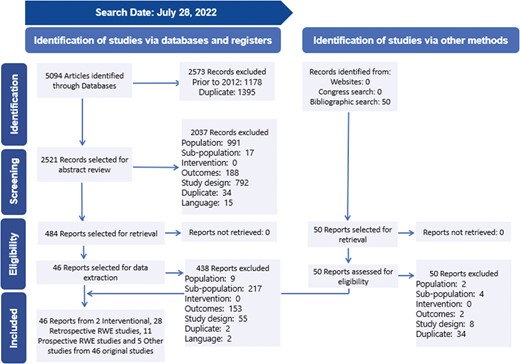

A total of 5094 records were identified in the SLR. Of these, 484 records were included for full-text review after deduplicating and screening them against the population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design (PICOS) criteria (Supplementary Table 2). Forty-six studies met the final inclusion criteria and were selected for extraction. Most of these studies were real-world evidence studies (28 retrospective and 14 prospective), and the 4 remaining studies had other study designs (2 interventional RCTs and 2 post hoc analyses of phase 3 RCTs, Figure 1). Twenty-five studies reported clinical outcomes among patients with MH vs patients without MH. Fourteen studies used validated scales (Table 1; Figure 2).

| Studies Reporting MH Using Validated Measures . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Validated Measure Used and Cut-off Score | Interventions |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 60 | Patients with CD who underwent capsule endoscopy | Lewis score <270 | Immunomodulator, anti-TNFα agent, prednisolone |

| Hoekman, 2018 | Retrospective, multicenter | Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany | 49 | Adult patients with mild to moderate CD | SES-CD = 0 | Corticosteroids, anti-TNF agents |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD | SES-CD ≤2 or Rutgeert’s score i0-i1 (for patients with history of previous surgery) | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | SES-CD ≤2 | Infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) |

| Takenaka, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Japan | 116 | Patients with CD in clinical-serological remission | SES-CDa = 0 | Concomitant treatment of steroids, immunomodulator, or anti-TNF inhibitor |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | SES-CD <5 | 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), glucocorticoid, azathioprine (AZA), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Naganuma, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 131 | Patients with CD with clinical remission and who underwent conventional ileocolonoscopy | SES-CD ≤2 | Surgical, nonsurgical |

| Yzet, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | France | 84 | Patients with CD | CDEIS = 0 | IFX, ADA or vedolizumab |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | Retrospective, single center, case review | US | 32 | Patients with CD who underwent ≥1 colonoscopy before or during treatment | SES-CD >70% reduction | Natalizumab |

| Morise, 2015 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 76 | Patients with CD who underwent transanal double-balloon endoscopy (DBE), included patients with stenosis which hampered passage of the scope and those who underwent DBE with observation for ≥ 80 cm from the ileocecal valve | mSES-CD <4 or SES-CD <4 | IFX, AZA, elemental diet, 5-ASA |

| Beigel, 2014 | Retrospective, single center | Germany | 152 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | SES-CD = 0 | One anti-TNFα antibody or 2 anti-TNFα antibodies |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | Retrospective, case control | Portugal | 47 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | Lewis score ≤135 | Thiopurines, biologics, corticosteroids |

| Elosua, 2021 | Retrospective, single center | Spain | 432 | Established patients with CD with SBCE | Lewis score <135 | 5-ASA, steroids, immunomodulators (thiopurines and methotrexate) and biologics (IFX, ADA, ustekinumab, vedolizumab and certolizumab) |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | Prospective, multicenter | Israel | 61 | Adult patients with CD involving the small bowel with confirmed small bowel patency | Lewis score <350 | Immunomodulators, biologics |

| Studies Reporting TH . | ||||||

| Study reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Measure used and Criteria for Healing | Interventions |

| Halle, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | France | 115 | Small bowel CD | A radiological response was defined as (1) a complete response, if all inflammatory signs had disappeared, (2) a partial response if the length of the wall enhancement of any inflammatory segment decreased or if there was a clear decrease in the size of an abscess or fistula without worsening of the other inflammatory parameters, (3) progression if any inflammatory segment showed a clear increase in any of inflammatory parameters or if a new inflammatory lesion appeared, and (4) stable in other cases | Immunosuppressant, anti-TNF treatment, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, steroids |

| Ma, 2021 | Prospective, single center, cohort | China | 77 | Patients with CD who had been consecutively hospitalized without use of CD-related steroids, immunosuppressants, or biologics for ≥6 months prior | BWT ≤3 mm in any place, with the normalization of stratification, no hypervascularization, the resolution of mesenteric inflammatory fat, and no signs of active inflammation (abscesses or fistulas) | NR |

| Messadeg, 2020 | Prospective, multicenter | France | 46 | Adult patients with CD | Early transmural response, defined as a 25% decrease of either Clermont score or MaRIA. Clermont score: 1.646 × bowel thickness − 1.321 × ADC + 5.613 × edema + 8.306 × ulcers + 5.039 MaRIA: 1.5 × wall thickening [mm] + 0.02 × RCE + 5 × edema + 10 × ulceration Transmural response: Cumulative score using 5 parameters (disappearance of ulcerations; disappearance in enlarged lymph nodes, disappearance of sclerolipomatosis; 30% decrease of RCE; 10% increase in ADC) | IFX or ADA |

| Deepak, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | US | 150 | Patients with small bowel CD who had pre-therapy CTE/MRE with follow-up CTE or MRE after 6 months, or 2 CTE/MREs ≥6 months apart while on maintenance therapy | CTE or MRE | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD who underwent a clinical, endoscopic, and radiological assessment of disease within 1 month | CTE Absence of lesions | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | Normalization of BWT of all inflamed segments involved in CD; BWT ≤3 mm | IFX and ADA |

| Paredes, 2019 | Prospective, single center | Spain | 36 | Adult patients with CD who were treated with biologics | Normalization of BWT (<3 mm) | IFX or ADA |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | MaRIA score of <50 | 5-ASA, glucocorticoid, AZA, 6-MP, IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Fernandes, 2017 | Retrospective, single center | Portugal | 214 | Patients with CD | Both a normal MRE and normal endoscopy: complete healing of all the bowel layers (including the mucosa) | Thiopurines, methotrexate, anti-TNF therapy |

| Lafeuille, 2021 | Retrospective, database review | France | 154 | Adult patients with CD | Combination of endoscopic MH and MRI healing (absence of mucosal ulceration including aphtoid erosions and no sign of active inflammation (ie, ulceration, edema, diffusion-weighted hyperintensity, increased contrast enhancement), no extra-enteric sign (ie, fat creeping, enlarged lymph nodes, comb sign), and no CD-related complications (ie, stricture, fistula, or abscess)) | 5-ASA, corticoids, immunosuppressants, anti-TNF agents, IFX, ADA, golimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab |

| Helwig, 2022 | Prospective, noninterventional, multicenter | Germany | 180 | Adult patients with ileocecal or colonic CD | Simplified TH: Normalization of BWT (terminal ileum ≤2mm, colon ≤3mm) and the absence of an amplified color Doppler signal (Limberg 1/2) Extended TH: Normalized BWT and normalized color Doppler signal or no loss of stratification or no fibrofatty proliferation Complete TH: All 4 factors normalized | Systemic corticosteroids, AZA/6-MP, anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti IL12/23 |

| Studies Reporting MH Using Validated Measures . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Validated Measure Used and Cut-off Score | Interventions |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 60 | Patients with CD who underwent capsule endoscopy | Lewis score <270 | Immunomodulator, anti-TNFα agent, prednisolone |

| Hoekman, 2018 | Retrospective, multicenter | Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany | 49 | Adult patients with mild to moderate CD | SES-CD = 0 | Corticosteroids, anti-TNF agents |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD | SES-CD ≤2 or Rutgeert’s score i0-i1 (for patients with history of previous surgery) | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | SES-CD ≤2 | Infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) |

| Takenaka, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Japan | 116 | Patients with CD in clinical-serological remission | SES-CDa = 0 | Concomitant treatment of steroids, immunomodulator, or anti-TNF inhibitor |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | SES-CD <5 | 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), glucocorticoid, azathioprine (AZA), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Naganuma, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 131 | Patients with CD with clinical remission and who underwent conventional ileocolonoscopy | SES-CD ≤2 | Surgical, nonsurgical |

| Yzet, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | France | 84 | Patients with CD | CDEIS = 0 | IFX, ADA or vedolizumab |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | Retrospective, single center, case review | US | 32 | Patients with CD who underwent ≥1 colonoscopy before or during treatment | SES-CD >70% reduction | Natalizumab |

| Morise, 2015 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 76 | Patients with CD who underwent transanal double-balloon endoscopy (DBE), included patients with stenosis which hampered passage of the scope and those who underwent DBE with observation for ≥ 80 cm from the ileocecal valve | mSES-CD <4 or SES-CD <4 | IFX, AZA, elemental diet, 5-ASA |

| Beigel, 2014 | Retrospective, single center | Germany | 152 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | SES-CD = 0 | One anti-TNFα antibody or 2 anti-TNFα antibodies |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | Retrospective, case control | Portugal | 47 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | Lewis score ≤135 | Thiopurines, biologics, corticosteroids |

| Elosua, 2021 | Retrospective, single center | Spain | 432 | Established patients with CD with SBCE | Lewis score <135 | 5-ASA, steroids, immunomodulators (thiopurines and methotrexate) and biologics (IFX, ADA, ustekinumab, vedolizumab and certolizumab) |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | Prospective, multicenter | Israel | 61 | Adult patients with CD involving the small bowel with confirmed small bowel patency | Lewis score <350 | Immunomodulators, biologics |

| Studies Reporting TH . | ||||||

| Study reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Measure used and Criteria for Healing | Interventions |

| Halle, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | France | 115 | Small bowel CD | A radiological response was defined as (1) a complete response, if all inflammatory signs had disappeared, (2) a partial response if the length of the wall enhancement of any inflammatory segment decreased or if there was a clear decrease in the size of an abscess or fistula without worsening of the other inflammatory parameters, (3) progression if any inflammatory segment showed a clear increase in any of inflammatory parameters or if a new inflammatory lesion appeared, and (4) stable in other cases | Immunosuppressant, anti-TNF treatment, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, steroids |

| Ma, 2021 | Prospective, single center, cohort | China | 77 | Patients with CD who had been consecutively hospitalized without use of CD-related steroids, immunosuppressants, or biologics for ≥6 months prior | BWT ≤3 mm in any place, with the normalization of stratification, no hypervascularization, the resolution of mesenteric inflammatory fat, and no signs of active inflammation (abscesses or fistulas) | NR |

| Messadeg, 2020 | Prospective, multicenter | France | 46 | Adult patients with CD | Early transmural response, defined as a 25% decrease of either Clermont score or MaRIA. Clermont score: 1.646 × bowel thickness − 1.321 × ADC + 5.613 × edema + 8.306 × ulcers + 5.039 MaRIA: 1.5 × wall thickening [mm] + 0.02 × RCE + 5 × edema + 10 × ulceration Transmural response: Cumulative score using 5 parameters (disappearance of ulcerations; disappearance in enlarged lymph nodes, disappearance of sclerolipomatosis; 30% decrease of RCE; 10% increase in ADC) | IFX or ADA |

| Deepak, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | US | 150 | Patients with small bowel CD who had pre-therapy CTE/MRE with follow-up CTE or MRE after 6 months, or 2 CTE/MREs ≥6 months apart while on maintenance therapy | CTE or MRE | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD who underwent a clinical, endoscopic, and radiological assessment of disease within 1 month | CTE Absence of lesions | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | Normalization of BWT of all inflamed segments involved in CD; BWT ≤3 mm | IFX and ADA |

| Paredes, 2019 | Prospective, single center | Spain | 36 | Adult patients with CD who were treated with biologics | Normalization of BWT (<3 mm) | IFX or ADA |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | MaRIA score of <50 | 5-ASA, glucocorticoid, AZA, 6-MP, IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Fernandes, 2017 | Retrospective, single center | Portugal | 214 | Patients with CD | Both a normal MRE and normal endoscopy: complete healing of all the bowel layers (including the mucosa) | Thiopurines, methotrexate, anti-TNF therapy |

| Lafeuille, 2021 | Retrospective, database review | France | 154 | Adult patients with CD | Combination of endoscopic MH and MRI healing (absence of mucosal ulceration including aphtoid erosions and no sign of active inflammation (ie, ulceration, edema, diffusion-weighted hyperintensity, increased contrast enhancement), no extra-enteric sign (ie, fat creeping, enlarged lymph nodes, comb sign), and no CD-related complications (ie, stricture, fistula, or abscess)) | 5-ASA, corticoids, immunosuppressants, anti-TNF agents, IFX, ADA, golimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab |

| Helwig, 2022 | Prospective, noninterventional, multicenter | Germany | 180 | Adult patients with ileocecal or colonic CD | Simplified TH: Normalization of BWT (terminal ileum ≤2mm, colon ≤3mm) and the absence of an amplified color Doppler signal (Limberg 1/2) Extended TH: Normalized BWT and normalized color Doppler signal or no loss of stratification or no fibrofatty proliferation Complete TH: All 4 factors normalized | Systemic corticosteroids, AZA/6-MP, anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti IL12/23 |

Abbreviations: 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; 6-MP, 6-mercaptoprine; ADA, adalimumab; AZA, azathioprine; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; BWT, bowel wall thickness; CD, Crohn’s disease; CDEIS, Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity; CTE, computed tomography enterography; DBE, double balloon endoscopy; IFX, Infliximab; MaRIA, Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity; MH, mucosal healing; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mSES-CD, modified SES-CD; NR, not reported; RCE, relative contrast enhancement; SBCE, small bowel endoscopy; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; SES-CDa, Simple Endoscopic Active Score for Crohn’s Disease; TH, transmural healing; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

| Studies Reporting MH Using Validated Measures . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Validated Measure Used and Cut-off Score | Interventions |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 60 | Patients with CD who underwent capsule endoscopy | Lewis score <270 | Immunomodulator, anti-TNFα agent, prednisolone |

| Hoekman, 2018 | Retrospective, multicenter | Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany | 49 | Adult patients with mild to moderate CD | SES-CD = 0 | Corticosteroids, anti-TNF agents |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD | SES-CD ≤2 or Rutgeert’s score i0-i1 (for patients with history of previous surgery) | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | SES-CD ≤2 | Infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) |

| Takenaka, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Japan | 116 | Patients with CD in clinical-serological remission | SES-CDa = 0 | Concomitant treatment of steroids, immunomodulator, or anti-TNF inhibitor |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | SES-CD <5 | 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), glucocorticoid, azathioprine (AZA), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Naganuma, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 131 | Patients with CD with clinical remission and who underwent conventional ileocolonoscopy | SES-CD ≤2 | Surgical, nonsurgical |

| Yzet, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | France | 84 | Patients with CD | CDEIS = 0 | IFX, ADA or vedolizumab |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | Retrospective, single center, case review | US | 32 | Patients with CD who underwent ≥1 colonoscopy before or during treatment | SES-CD >70% reduction | Natalizumab |

| Morise, 2015 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 76 | Patients with CD who underwent transanal double-balloon endoscopy (DBE), included patients with stenosis which hampered passage of the scope and those who underwent DBE with observation for ≥ 80 cm from the ileocecal valve | mSES-CD <4 or SES-CD <4 | IFX, AZA, elemental diet, 5-ASA |

| Beigel, 2014 | Retrospective, single center | Germany | 152 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | SES-CD = 0 | One anti-TNFα antibody or 2 anti-TNFα antibodies |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | Retrospective, case control | Portugal | 47 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | Lewis score ≤135 | Thiopurines, biologics, corticosteroids |

| Elosua, 2021 | Retrospective, single center | Spain | 432 | Established patients with CD with SBCE | Lewis score <135 | 5-ASA, steroids, immunomodulators (thiopurines and methotrexate) and biologics (IFX, ADA, ustekinumab, vedolizumab and certolizumab) |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | Prospective, multicenter | Israel | 61 | Adult patients with CD involving the small bowel with confirmed small bowel patency | Lewis score <350 | Immunomodulators, biologics |

| Studies Reporting TH . | ||||||

| Study reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Measure used and Criteria for Healing | Interventions |

| Halle, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | France | 115 | Small bowel CD | A radiological response was defined as (1) a complete response, if all inflammatory signs had disappeared, (2) a partial response if the length of the wall enhancement of any inflammatory segment decreased or if there was a clear decrease in the size of an abscess or fistula without worsening of the other inflammatory parameters, (3) progression if any inflammatory segment showed a clear increase in any of inflammatory parameters or if a new inflammatory lesion appeared, and (4) stable in other cases | Immunosuppressant, anti-TNF treatment, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, steroids |

| Ma, 2021 | Prospective, single center, cohort | China | 77 | Patients with CD who had been consecutively hospitalized without use of CD-related steroids, immunosuppressants, or biologics for ≥6 months prior | BWT ≤3 mm in any place, with the normalization of stratification, no hypervascularization, the resolution of mesenteric inflammatory fat, and no signs of active inflammation (abscesses or fistulas) | NR |

| Messadeg, 2020 | Prospective, multicenter | France | 46 | Adult patients with CD | Early transmural response, defined as a 25% decrease of either Clermont score or MaRIA. Clermont score: 1.646 × bowel thickness − 1.321 × ADC + 5.613 × edema + 8.306 × ulcers + 5.039 MaRIA: 1.5 × wall thickening [mm] + 0.02 × RCE + 5 × edema + 10 × ulceration Transmural response: Cumulative score using 5 parameters (disappearance of ulcerations; disappearance in enlarged lymph nodes, disappearance of sclerolipomatosis; 30% decrease of RCE; 10% increase in ADC) | IFX or ADA |

| Deepak, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | US | 150 | Patients with small bowel CD who had pre-therapy CTE/MRE with follow-up CTE or MRE after 6 months, or 2 CTE/MREs ≥6 months apart while on maintenance therapy | CTE or MRE | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD who underwent a clinical, endoscopic, and radiological assessment of disease within 1 month | CTE Absence of lesions | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | Normalization of BWT of all inflamed segments involved in CD; BWT ≤3 mm | IFX and ADA |

| Paredes, 2019 | Prospective, single center | Spain | 36 | Adult patients with CD who were treated with biologics | Normalization of BWT (<3 mm) | IFX or ADA |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | MaRIA score of <50 | 5-ASA, glucocorticoid, AZA, 6-MP, IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Fernandes, 2017 | Retrospective, single center | Portugal | 214 | Patients with CD | Both a normal MRE and normal endoscopy: complete healing of all the bowel layers (including the mucosa) | Thiopurines, methotrexate, anti-TNF therapy |

| Lafeuille, 2021 | Retrospective, database review | France | 154 | Adult patients with CD | Combination of endoscopic MH and MRI healing (absence of mucosal ulceration including aphtoid erosions and no sign of active inflammation (ie, ulceration, edema, diffusion-weighted hyperintensity, increased contrast enhancement), no extra-enteric sign (ie, fat creeping, enlarged lymph nodes, comb sign), and no CD-related complications (ie, stricture, fistula, or abscess)) | 5-ASA, corticoids, immunosuppressants, anti-TNF agents, IFX, ADA, golimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab |

| Helwig, 2022 | Prospective, noninterventional, multicenter | Germany | 180 | Adult patients with ileocecal or colonic CD | Simplified TH: Normalization of BWT (terminal ileum ≤2mm, colon ≤3mm) and the absence of an amplified color Doppler signal (Limberg 1/2) Extended TH: Normalized BWT and normalized color Doppler signal or no loss of stratification or no fibrofatty proliferation Complete TH: All 4 factors normalized | Systemic corticosteroids, AZA/6-MP, anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti IL12/23 |

| Studies Reporting MH Using Validated Measures . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Validated Measure Used and Cut-off Score | Interventions |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 60 | Patients with CD who underwent capsule endoscopy | Lewis score <270 | Immunomodulator, anti-TNFα agent, prednisolone |

| Hoekman, 2018 | Retrospective, multicenter | Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany | 49 | Adult patients with mild to moderate CD | SES-CD = 0 | Corticosteroids, anti-TNF agents |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD | SES-CD ≤2 or Rutgeert’s score i0-i1 (for patients with history of previous surgery) | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | SES-CD ≤2 | Infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) |

| Takenaka, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Japan | 116 | Patients with CD in clinical-serological remission | SES-CDa = 0 | Concomitant treatment of steroids, immunomodulator, or anti-TNF inhibitor |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | SES-CD <5 | 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), glucocorticoid, azathioprine (AZA), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Naganuma, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 131 | Patients with CD with clinical remission and who underwent conventional ileocolonoscopy | SES-CD ≤2 | Surgical, nonsurgical |

| Yzet, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | France | 84 | Patients with CD | CDEIS = 0 | IFX, ADA or vedolizumab |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | Retrospective, single center, case review | US | 32 | Patients with CD who underwent ≥1 colonoscopy before or during treatment | SES-CD >70% reduction | Natalizumab |

| Morise, 2015 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 76 | Patients with CD who underwent transanal double-balloon endoscopy (DBE), included patients with stenosis which hampered passage of the scope and those who underwent DBE with observation for ≥ 80 cm from the ileocecal valve | mSES-CD <4 or SES-CD <4 | IFX, AZA, elemental diet, 5-ASA |

| Beigel, 2014 | Retrospective, single center | Germany | 152 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | SES-CD = 0 | One anti-TNFα antibody or 2 anti-TNFα antibodies |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | Retrospective, case control | Portugal | 47 | CD subgroup patients treated with anti-TNFα antibodies (IFX and/or ADA) | Lewis score ≤135 | Thiopurines, biologics, corticosteroids |

| Elosua, 2021 | Retrospective, single center | Spain | 432 | Established patients with CD with SBCE | Lewis score <135 | 5-ASA, steroids, immunomodulators (thiopurines and methotrexate) and biologics (IFX, ADA, ustekinumab, vedolizumab and certolizumab) |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | Prospective, multicenter | Israel | 61 | Adult patients with CD involving the small bowel with confirmed small bowel patency | Lewis score <350 | Immunomodulators, biologics |

| Studies Reporting TH . | ||||||

| Study reference (author, year) | Study Design | Geography | N | Patient Population | Measure used and Criteria for Healing | Interventions |

| Halle, 2020 | Retrospective, single center | France | 115 | Small bowel CD | A radiological response was defined as (1) a complete response, if all inflammatory signs had disappeared, (2) a partial response if the length of the wall enhancement of any inflammatory segment decreased or if there was a clear decrease in the size of an abscess or fistula without worsening of the other inflammatory parameters, (3) progression if any inflammatory segment showed a clear increase in any of inflammatory parameters or if a new inflammatory lesion appeared, and (4) stable in other cases | Immunosuppressant, anti-TNF treatment, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, steroids |

| Ma, 2021 | Prospective, single center, cohort | China | 77 | Patients with CD who had been consecutively hospitalized without use of CD-related steroids, immunosuppressants, or biologics for ≥6 months prior | BWT ≤3 mm in any place, with the normalization of stratification, no hypervascularization, the resolution of mesenteric inflammatory fat, and no signs of active inflammation (abscesses or fistulas) | NR |

| Messadeg, 2020 | Prospective, multicenter | France | 46 | Adult patients with CD | Early transmural response, defined as a 25% decrease of either Clermont score or MaRIA. Clermont score: 1.646 × bowel thickness − 1.321 × ADC + 5.613 × edema + 8.306 × ulcers + 5.039 MaRIA: 1.5 × wall thickening [mm] + 0.02 × RCE + 5 × edema + 10 × ulceration Transmural response: Cumulative score using 5 parameters (disappearance of ulcerations; disappearance in enlarged lymph nodes, disappearance of sclerolipomatosis; 30% decrease of RCE; 10% increase in ADC) | IFX or ADA |

| Deepak, 2016 | Retrospective, single center | US | 150 | Patients with small bowel CD who had pre-therapy CTE/MRE with follow-up CTE or MRE after 6 months, or 2 CTE/MREs ≥6 months apart while on maintenance therapy | CTE or MRE | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | Prospective, single center | Italy | 57 | Patients with CD who underwent a clinical, endoscopic, and radiological assessment of disease within 1 month | CTE Absence of lesions | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | Prospective, single center, longitudinal | Italy | 218 | Patients with CD achieving TH following treatment with biologics Patients reaching only MH or no healing | Normalization of BWT of all inflamed segments involved in CD; BWT ≤3 mm | IFX and ADA |

| Paredes, 2019 | Prospective, single center | Spain | 36 | Adult patients with CD who were treated with biologics | Normalization of BWT (<3 mm) | IFX or ADA |

| Sagami, 2019 | Retrospective, single center | Japan | 50 | Patients with CD who underwent ileocolonoscopy and MRE | MaRIA score of <50 | 5-ASA, glucocorticoid, AZA, 6-MP, IFX, ADA, elemental diet, antibiotics, none |

| Fernandes, 2017 | Retrospective, single center | Portugal | 214 | Patients with CD | Both a normal MRE and normal endoscopy: complete healing of all the bowel layers (including the mucosa) | Thiopurines, methotrexate, anti-TNF therapy |

| Lafeuille, 2021 | Retrospective, database review | France | 154 | Adult patients with CD | Combination of endoscopic MH and MRI healing (absence of mucosal ulceration including aphtoid erosions and no sign of active inflammation (ie, ulceration, edema, diffusion-weighted hyperintensity, increased contrast enhancement), no extra-enteric sign (ie, fat creeping, enlarged lymph nodes, comb sign), and no CD-related complications (ie, stricture, fistula, or abscess)) | 5-ASA, corticoids, immunosuppressants, anti-TNF agents, IFX, ADA, golimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab |

| Helwig, 2022 | Prospective, noninterventional, multicenter | Germany | 180 | Adult patients with ileocecal or colonic CD | Simplified TH: Normalization of BWT (terminal ileum ≤2mm, colon ≤3mm) and the absence of an amplified color Doppler signal (Limberg 1/2) Extended TH: Normalized BWT and normalized color Doppler signal or no loss of stratification or no fibrofatty proliferation Complete TH: All 4 factors normalized | Systemic corticosteroids, AZA/6-MP, anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti IL12/23 |

Abbreviations: 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; 6-MP, 6-mercaptoprine; ADA, adalimumab; AZA, azathioprine; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; BWT, bowel wall thickness; CD, Crohn’s disease; CDEIS, Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity; CTE, computed tomography enterography; DBE, double balloon endoscopy; IFX, Infliximab; MaRIA, Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity; MH, mucosal healing; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mSES-CD, modified SES-CD; NR, not reported; RCE, relative contrast enhancement; SBCE, small bowel endoscopy; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; SES-CDa, Simple Endoscopic Active Score for Crohn’s Disease; TH, transmural healing; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

PRISMA flow diagram. Abbreviations: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RWE, real-world evidence

Scales used for MH and TH. A, Scales used for MH; B, Scales used for TH. Abbreviations: BUSS, Bowel Ultrasound Score; BWT, Bowel wall thickness; CDEIS, Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity; CTE, computed tomography enterography; MaRIA, Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity; MH, mucosal healing; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mSES-CD, Modified Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; TH, transmural healing.

Study Population and Follow-up Time

The study populations included a total of 5530 adult patients with a median disease duration ranging from 10.3 to 180 months. Median patient age ranged from 21.0 to 43.5 years. Validated endoscopic measures indicated a wide range of disease severity at baseline, as indicated by scores such as CDEIS <430 and SES-CD 0 to 18. Similarly, wide ranges in clinical measures at baseline were observed including BWT (≤3 mm and >3 mm)31; Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI; mean 106.7-450)27,32,33; Harvey–Bradshaw Index (HBI; mean 2.0 [SD: 2.3] to median 11 [IQR: 8-15])34,35; and Rutgeert’s score36 (i0-i1: 11/57 Table 1). Four studies included patients with a disease duration of 2 years or less, all of whom had full or partial MH at baseline.12,30,33,37

Follow-up time ranged from 16 weeks to 11 years. Cost and work productivity data were not reported by studies using validated scales. Quality of life data were not reported by studies comparing MH and non-MH using a validated scale or by studies comparing TH and non-TH.

Mucosal Healing

Thirty-nine studies reported on long-term outcomes among patients with MH with follow-up times ranging from 5 to 132 months (Table 2); however, definitions of MH and outcomes used to assess MH varied across studies (Supplementary Table 3). Studies that reported MH outcomes without using validated scales typically described the presence of MH based on visible inflammation as observed through endoscopy; these studies were not included in our analyses. The remaining 14 studies reported on long-term outcomes using established definitions of MH that included the SES-CD (9 studies), CDEIS (1 study), and Lewis (4 studies) scores.

| Study Reference (author, year) . | . | . | Results and significance . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Time (months) | Intervention of Interest* | Clinical remission | Relapse/ recurrence | Treatment Change | Hospitalization | Surgery | Event-free Survival | |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | ≤24 | None | NR | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 5.3% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 2.6% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 27.3% vs 2.6% • Multivariate HR for patients with LS ≥270: 9.475 (95% CI, 2.596-34.59), P = .001 | NR | NR |

| Hoekman, 2018 | 24 | Early combined immunosuppression (top-down) vs conventional management (step-up) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 70% vs 70% (P = .64) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 13% vs 13% (P = .65) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between patients with MH vs no MH for use of rescue therapy (P = .48) or time to new fistula (P = .37) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups for time to CD-related hospitalization (P = .67) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups in time to CD-related surgery (P = .5) | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | 36 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: up to 36 months • Baseline mucosal activity associated with higher use of topical steroids (P < .01) • No differences found for the use of immunosuppressants, systemic steroids, and anti-TNFα | Timepoint: up to 36 months • No differences between groups based on mucosal activity | NR | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | 12 | Anti-TNF alpha agents | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 75% vs 41% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o NH: 0.2 (95% CI, 0.1-0.6), P = .03 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 25% vs 59% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.06 (95% CI, 0.02‐0.1), P < .001 o NH: 7.79 (95% CI, 3.1‐19.5), P < .001 | Timepoint: 1 year (need for dose escalation) • MH vs NH: 33.3% vs 38.8% (P = .6) • Need for dose escalation, MH vs NH: HR = 0.96 (95% Cl, 0.73-1.24), P = .08 • “Switch or swap,” MH vs NH: 15% vs 26.6% (P = .1) | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 28.3% vs 66.6% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.1 (95% Cl, 0.05‐0.3), P < .001 o NH: 3.6 (95% Cl, 1.6‐8.1), P = .002 • Need for hospitalization, MH vs NH: HR = 0.65 (95% Cl, 0.49-0.86), P = .01 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 10% vs 35.5% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.2 (95% Cl, 0.07‐0.6), P = .006 o NH: 3.8 (95% Cl, 1.9‐6.8), P < .001 • Later need for surgery, MH vs NH: HR = 0.83 (95% Cl, 0.76-0.92), P = .01 | NR |

| Takenaka, 2018 | 27 | None | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease o Clinical relapse: 9.2% vs 36.5% o Serological relapse: 31.6% vs 60.3% • Multivariate HR in ulcerative disease: o Clinical relapse: 5.34 (95% CI, 2.06-13.81), P = .001 o Serological relapse: 3.02 (95% CI, 1.65-5.51), P < .001 | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 18.4% vs 42.9% • Adjusted HR in ulcerative disease: 2.34 (95% CI, 1.13-4.83), P = .021 | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 3.9% vs 20.6% • Adjusted HR for surgery in no/mild disease: 5.40 (95% CI, 1.41-20.67), P = .014 | NR |

| Sagami, 2019 | 15 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: Median: 449 days • Time to treatment escalation for endoscopic remission vs endoscopic active disease: HR = 2.43 (95% CI, 1.09-5.42), P = .0302 | NR | NR | NR |

| Naganuma, 2016 | ≥ 6 | None | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Duration of clinical remission, MH vs non-MH: 44.8 vs 16.9 months (P < .01) • Multivariate HR for maintenance of remission in MH: HR = 0.17 (95% CI, 0.06-0.48), P = .001 | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Total population: 39% had clinical recurrence | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yzet, 2019 | 58 | Anti-TNF agents | NR | NR | • Median TTF for: o EH: 21.5 months o Partial MH: 13.5 months • Complete EH vs Partial MH o Treatment failure at 1 year: 9% vs 16% (P = .028) o Treatment failure at 3 years: 19% vs 37% (P = .049) • Multivariate HR for partial MH vs complete EH: 2.17 (95% CI, 1.01-4.65), P = .0204 | Increased risk of CD-related hospitalization with partial MH: P < .0246 | Increased risk of CD-related intestinal resection with partial MH: P = .0082 | NR |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | 5 | Natalizumab | NR | NR | • Proportion of patients continuing natalizumab significantly higher in patients with a significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH (P = .032)† | • RR for hospitalization per patient-year follow-up for MH with: o Significant vs no improvement: 0.17 (95% CI, 0.039-0.78) o Partial vs no improvement: 0.77 (95% CI, 0.24-2.5) | Median time after initiation of therapy: 5 months • Rate of surgery during or after natalizumab for patients with significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH: 66.7% vs 44.4% vs 27.3% | NR |

| Morise, 2015 | NR | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | • 34.2% of patients underwent surgery • Multivariate analysis: mSES-CD (≥4) associated with surgery-free survival: HR = 9.38 (95% CI, 1.20-73.5), P = .033 | NR |

| Beigel, 2014 | 58–87.5 | Infliximab and/or adalimumab | NR | NR | NR | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD hospitalized, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 9 vs 26 (P = .82) o TNF2: 2 vs 11 (P = .42) | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD undergoing surgery, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 3 vs 24 (P = .049) o TNF2: 0 vs 7 (P = .14) | NR |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | ≥12 | None | NR | Timepoint: 1 year MH vs no MH • 25.5% vs 48.3% (P = .01) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Elosua, 2021 | 132 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: At next clinic visit or within 3 months after capsule endoscopy MH vs mild-to-moderate mucosal inflammation vs moderate-to-severe mucosal inflammation • Treatment escalation o 6.3% vs 57.8% vs 89.5% (P < .001) • De-escalation of therapy o 13.9% vs 1.1% vs 0% (P < .001) | NR | NR | NR |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | 24 | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Study Reference (author, year) . | . | . | Results and significance . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Time (months) | Intervention of Interest* | Clinical remission | Relapse/ recurrence | Treatment Change | Hospitalization | Surgery | Event-free Survival | |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | ≤24 | None | NR | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 5.3% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 2.6% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 27.3% vs 2.6% • Multivariate HR for patients with LS ≥270: 9.475 (95% CI, 2.596-34.59), P = .001 | NR | NR |

| Hoekman, 2018 | 24 | Early combined immunosuppression (top-down) vs conventional management (step-up) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 70% vs 70% (P = .64) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 13% vs 13% (P = .65) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between patients with MH vs no MH for use of rescue therapy (P = .48) or time to new fistula (P = .37) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups for time to CD-related hospitalization (P = .67) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups in time to CD-related surgery (P = .5) | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | 36 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: up to 36 months • Baseline mucosal activity associated with higher use of topical steroids (P < .01) • No differences found for the use of immunosuppressants, systemic steroids, and anti-TNFα | Timepoint: up to 36 months • No differences between groups based on mucosal activity | NR | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | 12 | Anti-TNF alpha agents | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 75% vs 41% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o NH: 0.2 (95% CI, 0.1-0.6), P = .03 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 25% vs 59% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.06 (95% CI, 0.02‐0.1), P < .001 o NH: 7.79 (95% CI, 3.1‐19.5), P < .001 | Timepoint: 1 year (need for dose escalation) • MH vs NH: 33.3% vs 38.8% (P = .6) • Need for dose escalation, MH vs NH: HR = 0.96 (95% Cl, 0.73-1.24), P = .08 • “Switch or swap,” MH vs NH: 15% vs 26.6% (P = .1) | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 28.3% vs 66.6% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.1 (95% Cl, 0.05‐0.3), P < .001 o NH: 3.6 (95% Cl, 1.6‐8.1), P = .002 • Need for hospitalization, MH vs NH: HR = 0.65 (95% Cl, 0.49-0.86), P = .01 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 10% vs 35.5% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.2 (95% Cl, 0.07‐0.6), P = .006 o NH: 3.8 (95% Cl, 1.9‐6.8), P < .001 • Later need for surgery, MH vs NH: HR = 0.83 (95% Cl, 0.76-0.92), P = .01 | NR |

| Takenaka, 2018 | 27 | None | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease o Clinical relapse: 9.2% vs 36.5% o Serological relapse: 31.6% vs 60.3% • Multivariate HR in ulcerative disease: o Clinical relapse: 5.34 (95% CI, 2.06-13.81), P = .001 o Serological relapse: 3.02 (95% CI, 1.65-5.51), P < .001 | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 18.4% vs 42.9% • Adjusted HR in ulcerative disease: 2.34 (95% CI, 1.13-4.83), P = .021 | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 3.9% vs 20.6% • Adjusted HR for surgery in no/mild disease: 5.40 (95% CI, 1.41-20.67), P = .014 | NR |

| Sagami, 2019 | 15 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: Median: 449 days • Time to treatment escalation for endoscopic remission vs endoscopic active disease: HR = 2.43 (95% CI, 1.09-5.42), P = .0302 | NR | NR | NR |

| Naganuma, 2016 | ≥ 6 | None | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Duration of clinical remission, MH vs non-MH: 44.8 vs 16.9 months (P < .01) • Multivariate HR for maintenance of remission in MH: HR = 0.17 (95% CI, 0.06-0.48), P = .001 | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Total population: 39% had clinical recurrence | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yzet, 2019 | 58 | Anti-TNF agents | NR | NR | • Median TTF for: o EH: 21.5 months o Partial MH: 13.5 months • Complete EH vs Partial MH o Treatment failure at 1 year: 9% vs 16% (P = .028) o Treatment failure at 3 years: 19% vs 37% (P = .049) • Multivariate HR for partial MH vs complete EH: 2.17 (95% CI, 1.01-4.65), P = .0204 | Increased risk of CD-related hospitalization with partial MH: P < .0246 | Increased risk of CD-related intestinal resection with partial MH: P = .0082 | NR |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | 5 | Natalizumab | NR | NR | • Proportion of patients continuing natalizumab significantly higher in patients with a significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH (P = .032)† | • RR for hospitalization per patient-year follow-up for MH with: o Significant vs no improvement: 0.17 (95% CI, 0.039-0.78) o Partial vs no improvement: 0.77 (95% CI, 0.24-2.5) | Median time after initiation of therapy: 5 months • Rate of surgery during or after natalizumab for patients with significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH: 66.7% vs 44.4% vs 27.3% | NR |

| Morise, 2015 | NR | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | • 34.2% of patients underwent surgery • Multivariate analysis: mSES-CD (≥4) associated with surgery-free survival: HR = 9.38 (95% CI, 1.20-73.5), P = .033 | NR |

| Beigel, 2014 | 58–87.5 | Infliximab and/or adalimumab | NR | NR | NR | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD hospitalized, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 9 vs 26 (P = .82) o TNF2: 2 vs 11 (P = .42) | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD undergoing surgery, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 3 vs 24 (P = .049) o TNF2: 0 vs 7 (P = .14) | NR |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | ≥12 | None | NR | Timepoint: 1 year MH vs no MH • 25.5% vs 48.3% (P = .01) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Elosua, 2021 | 132 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: At next clinic visit or within 3 months after capsule endoscopy MH vs mild-to-moderate mucosal inflammation vs moderate-to-severe mucosal inflammation • Treatment escalation o 6.3% vs 57.8% vs 89.5% (P < .001) • De-escalation of therapy o 13.9% vs 1.1% vs 0% (P < .001) | NR | NR | NR |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | 24 | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn’s disease; CI, confidence interval; DBE, double balloon endoscopy; EH, endoscopic healing; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; LS, Lewis score; MH, mucosal healing; mSES-CD, modified SES-CD; NA, not applicable; NH, no healing; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; RR, relative risk; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; TNF1, one TNFα antibody; TNF2, 2 TNFα antibodies; TTF, time to treatment failure.

*Studies without an intervention of interest included real-world and observational studies that did not limit the patient participation based on existing treatment regimens (ie, all-comers).

†MH with significant improvement: >70% reduction of SES-CD; MH with partial improvement: 20%-70% reduction of SES-CD; No improvement in MH: <20% reduction of SES-CD.

| Study Reference (author, year) . | . | . | Results and significance . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Time (months) | Intervention of Interest* | Clinical remission | Relapse/ recurrence | Treatment Change | Hospitalization | Surgery | Event-free Survival | |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | ≤24 | None | NR | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 5.3% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 2.6% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 27.3% vs 2.6% • Multivariate HR for patients with LS ≥270: 9.475 (95% CI, 2.596-34.59), P = .001 | NR | NR |

| Hoekman, 2018 | 24 | Early combined immunosuppression (top-down) vs conventional management (step-up) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 70% vs 70% (P = .64) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 13% vs 13% (P = .65) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between patients with MH vs no MH for use of rescue therapy (P = .48) or time to new fistula (P = .37) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups for time to CD-related hospitalization (P = .67) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups in time to CD-related surgery (P = .5) | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | 36 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: up to 36 months • Baseline mucosal activity associated with higher use of topical steroids (P < .01) • No differences found for the use of immunosuppressants, systemic steroids, and anti-TNFα | Timepoint: up to 36 months • No differences between groups based on mucosal activity | NR | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | 12 | Anti-TNF alpha agents | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 75% vs 41% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o NH: 0.2 (95% CI, 0.1-0.6), P = .03 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 25% vs 59% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.06 (95% CI, 0.02‐0.1), P < .001 o NH: 7.79 (95% CI, 3.1‐19.5), P < .001 | Timepoint: 1 year (need for dose escalation) • MH vs NH: 33.3% vs 38.8% (P = .6) • Need for dose escalation, MH vs NH: HR = 0.96 (95% Cl, 0.73-1.24), P = .08 • “Switch or swap,” MH vs NH: 15% vs 26.6% (P = .1) | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 28.3% vs 66.6% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.1 (95% Cl, 0.05‐0.3), P < .001 o NH: 3.6 (95% Cl, 1.6‐8.1), P = .002 • Need for hospitalization, MH vs NH: HR = 0.65 (95% Cl, 0.49-0.86), P = .01 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 10% vs 35.5% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.2 (95% Cl, 0.07‐0.6), P = .006 o NH: 3.8 (95% Cl, 1.9‐6.8), P < .001 • Later need for surgery, MH vs NH: HR = 0.83 (95% Cl, 0.76-0.92), P = .01 | NR |

| Takenaka, 2018 | 27 | None | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease o Clinical relapse: 9.2% vs 36.5% o Serological relapse: 31.6% vs 60.3% • Multivariate HR in ulcerative disease: o Clinical relapse: 5.34 (95% CI, 2.06-13.81), P = .001 o Serological relapse: 3.02 (95% CI, 1.65-5.51), P < .001 | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 18.4% vs 42.9% • Adjusted HR in ulcerative disease: 2.34 (95% CI, 1.13-4.83), P = .021 | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 3.9% vs 20.6% • Adjusted HR for surgery in no/mild disease: 5.40 (95% CI, 1.41-20.67), P = .014 | NR |

| Sagami, 2019 | 15 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: Median: 449 days • Time to treatment escalation for endoscopic remission vs endoscopic active disease: HR = 2.43 (95% CI, 1.09-5.42), P = .0302 | NR | NR | NR |

| Naganuma, 2016 | ≥ 6 | None | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Duration of clinical remission, MH vs non-MH: 44.8 vs 16.9 months (P < .01) • Multivariate HR for maintenance of remission in MH: HR = 0.17 (95% CI, 0.06-0.48), P = .001 | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Total population: 39% had clinical recurrence | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yzet, 2019 | 58 | Anti-TNF agents | NR | NR | • Median TTF for: o EH: 21.5 months o Partial MH: 13.5 months • Complete EH vs Partial MH o Treatment failure at 1 year: 9% vs 16% (P = .028) o Treatment failure at 3 years: 19% vs 37% (P = .049) • Multivariate HR for partial MH vs complete EH: 2.17 (95% CI, 1.01-4.65), P = .0204 | Increased risk of CD-related hospitalization with partial MH: P < .0246 | Increased risk of CD-related intestinal resection with partial MH: P = .0082 | NR |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | 5 | Natalizumab | NR | NR | • Proportion of patients continuing natalizumab significantly higher in patients with a significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH (P = .032)† | • RR for hospitalization per patient-year follow-up for MH with: o Significant vs no improvement: 0.17 (95% CI, 0.039-0.78) o Partial vs no improvement: 0.77 (95% CI, 0.24-2.5) | Median time after initiation of therapy: 5 months • Rate of surgery during or after natalizumab for patients with significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH: 66.7% vs 44.4% vs 27.3% | NR |

| Morise, 2015 | NR | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | • 34.2% of patients underwent surgery • Multivariate analysis: mSES-CD (≥4) associated with surgery-free survival: HR = 9.38 (95% CI, 1.20-73.5), P = .033 | NR |

| Beigel, 2014 | 58–87.5 | Infliximab and/or adalimumab | NR | NR | NR | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD hospitalized, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 9 vs 26 (P = .82) o TNF2: 2 vs 11 (P = .42) | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD undergoing surgery, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 3 vs 24 (P = .049) o TNF2: 0 vs 7 (P = .14) | NR |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | ≥12 | None | NR | Timepoint: 1 year MH vs no MH • 25.5% vs 48.3% (P = .01) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Elosua, 2021 | 132 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: At next clinic visit or within 3 months after capsule endoscopy MH vs mild-to-moderate mucosal inflammation vs moderate-to-severe mucosal inflammation • Treatment escalation o 6.3% vs 57.8% vs 89.5% (P < .001) • De-escalation of therapy o 13.9% vs 1.1% vs 0% (P < .001) | NR | NR | NR |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | 24 | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Study Reference (author, year) . | . | . | Results and significance . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Time (months) | Intervention of Interest* | Clinical remission | Relapse/ recurrence | Treatment Change | Hospitalization | Surgery | Event-free Survival | |

| Nishikawa, 2020 | ≤24 | None | NR | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 5.3% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 54.5% vs 2.6% | Timepoint: within 2 years LS ≥270 vs <270: • 27.3% vs 2.6% • Multivariate HR for patients with LS ≥270: 9.475 (95% CI, 2.596-34.59), P = .001 | NR | NR |

| Hoekman, 2018 | 24 | Early combined immunosuppression (top-down) vs conventional management (step-up) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 70% vs 70% (P = .64) | Timepoint: 104 weeks MH vs no MH • Median: 13% vs 13% (P = .65) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between patients with MH vs no MH for use of rescue therapy (P = .48) or time to new fistula (P = .37) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups for time to CD-related hospitalization (P = .67) | Timepoint: 104 weeks • No difference between groups in time to CD-related surgery (P = .5) | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | 36 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: up to 36 months • Baseline mucosal activity associated with higher use of topical steroids (P < .01) • No differences found for the use of immunosuppressants, systemic steroids, and anti-TNFα | Timepoint: up to 36 months • No differences between groups based on mucosal activity | NR | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | 12 | Anti-TNF alpha agents | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 75% vs 41% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o NH: 0.2 (95% CI, 0.1-0.6), P = .03 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 25% vs 59% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.06 (95% CI, 0.02‐0.1), P < .001 o NH: 7.79 (95% CI, 3.1‐19.5), P < .001 | Timepoint: 1 year (need for dose escalation) • MH vs NH: 33.3% vs 38.8% (P = .6) • Need for dose escalation, MH vs NH: HR = 0.96 (95% Cl, 0.73-1.24), P = .08 • “Switch or swap,” MH vs NH: 15% vs 26.6% (P = .1) | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 28.3% vs 66.6% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.1 (95% Cl, 0.05‐0.3), P < .001 o NH: 3.6 (95% Cl, 1.6‐8.1), P = .002 • Need for hospitalization, MH vs NH: HR = 0.65 (95% Cl, 0.49-0.86), P = .01 | Timepoint: 1 year • MH vs NH: 10% vs 35.5% (P < .001) • Multivariate OR: o MH: 0.2 (95% Cl, 0.07‐0.6), P = .006 o NH: 3.8 (95% Cl, 1.9‐6.8), P < .001 • Later need for surgery, MH vs NH: HR = 0.83 (95% Cl, 0.76-0.92), P = .01 | NR |

| Takenaka, 2018 | 27 | None | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease o Clinical relapse: 9.2% vs 36.5% o Serological relapse: 31.6% vs 60.3% • Multivariate HR in ulcerative disease: o Clinical relapse: 5.34 (95% CI, 2.06-13.81), P = .001 o Serological relapse: 3.02 (95% CI, 1.65-5.51), P < .001 | NR | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 18.4% vs 42.9% • Adjusted HR in ulcerative disease: 2.34 (95% CI, 1.13-4.83), P = .021 | Timepoint: Median: 27 months • No/mild disease vs ulcerative disease: 3.9% vs 20.6% • Adjusted HR for surgery in no/mild disease: 5.40 (95% CI, 1.41-20.67), P = .014 | NR |

| Sagami, 2019 | 15 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: Median: 449 days • Time to treatment escalation for endoscopic remission vs endoscopic active disease: HR = 2.43 (95% CI, 1.09-5.42), P = .0302 | NR | NR | NR |

| Naganuma, 2016 | ≥ 6 | None | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Duration of clinical remission, MH vs non-MH: 44.8 vs 16.9 months (P < .01) • Multivariate HR for maintenance of remission in MH: HR = 0.17 (95% CI, 0.06-0.48), P = .001 | Timepoint: Mean: 23.5 months • Total population: 39% had clinical recurrence | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yzet, 2019 | 58 | Anti-TNF agents | NR | NR | • Median TTF for: o EH: 21.5 months o Partial MH: 13.5 months • Complete EH vs Partial MH o Treatment failure at 1 year: 9% vs 16% (P = .028) o Treatment failure at 3 years: 19% vs 37% (P = .049) • Multivariate HR for partial MH vs complete EH: 2.17 (95% CI, 1.01-4.65), P = .0204 | Increased risk of CD-related hospitalization with partial MH: P < .0246 | Increased risk of CD-related intestinal resection with partial MH: P = .0082 | NR |

| Sakuraba, 2013 | 5 | Natalizumab | NR | NR | • Proportion of patients continuing natalizumab significantly higher in patients with a significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH (P = .032)† | • RR for hospitalization per patient-year follow-up for MH with: o Significant vs no improvement: 0.17 (95% CI, 0.039-0.78) o Partial vs no improvement: 0.77 (95% CI, 0.24-2.5) | Median time after initiation of therapy: 5 months • Rate of surgery during or after natalizumab for patients with significant vs partial vs no improvement in MH: 66.7% vs 44.4% vs 27.3% | NR |

| Morise, 2015 | NR | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | • 34.2% of patients underwent surgery • Multivariate analysis: mSES-CD (≥4) associated with surgery-free survival: HR = 9.38 (95% CI, 1.20-73.5), P = .033 | NR |

| Beigel, 2014 | 58–87.5 | Infliximab and/or adalimumab | NR | NR | NR | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD hospitalized, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 9 vs 26 (P = .82) o TNF2: 2 vs 11 (P = .42) | Median time from baseline to follow-up colonoscopy: TNF1: 63 months TNF2: 64.5 months • Patients with CD undergoing surgery, MH vs no MH (n): o TNF1: 3 vs 24 (P = .049) o TNF2: 0 vs 7 (P = .14) | NR |

| Macedo Silva, 2022 | ≥12 | None | NR | Timepoint: 1 year MH vs no MH • 25.5% vs 48.3% (P = .01) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Elosua, 2021 | 132 | None | NR | NR | Timepoint: At next clinic visit or within 3 months after capsule endoscopy MH vs mild-to-moderate mucosal inflammation vs moderate-to-severe mucosal inflammation • Treatment escalation o 6.3% vs 57.8% vs 89.5% (P < .001) • De-escalation of therapy o 13.9% vs 1.1% vs 0% (P < .001) | NR | NR | NR |

| Ben-Horin, 2019 | 24 | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn’s disease; CI, confidence interval; DBE, double balloon endoscopy; EH, endoscopic healing; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; LS, Lewis score; MH, mucosal healing; mSES-CD, modified SES-CD; NA, not applicable; NH, no healing; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; RR, relative risk; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; TNF1, one TNFα antibody; TNF2, 2 TNFα antibodies; TTF, time to treatment failure.

*Studies without an intervention of interest included real-world and observational studies that did not limit the patient participation based on existing treatment regimens (ie, all-comers).

†MH with significant improvement: >70% reduction of SES-CD; MH with partial improvement: 20%-70% reduction of SES-CD; No improvement in MH: <20% reduction of SES-CD.

Clinical outcomes

Twenty-five studies reported clinical outcomes among patients with and without MH; 12 of these studies used validated scales. Three studies31,33,38 reporting clinical remission used the SES-CD scale to measure MH, and only 1 of these studies38 showed that MH was able to predict sustained clinical remission in a multivariate analysis. Five studies reporting relapse/recurrence used validated scales to define MH (SES-CD, 3 studies31,33,39; and Lewis score, 2 studies40,41). Of these, 3 showed significantly lower relapse/recurrence rates among patients with MH vs without MH. Single-center studies in Italy31 and Japan39 used multivariate analysis to show that patients with MH were less likely to have a clinical relapse, and a retrospective study in Portugal40 showed that patients with MH were less likely to suffer a disease flare compared with those without MH.

Eight studies reported the need for treatment change as an outcome indicating active disease and used a validated scale to define MH (SES-CD, 5 studies31,33–36; CDEIS, 1 study30; and Lewis score, 2 studies41,42). Six of these studies reported significantly lower need for change in treatment (ie, treatment failure rates, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor [TNFi]-intensification, topical steroid specific) among patients achieving MH. Only Ben-Horin et al43 used a validated measure, the Lewis score, as a measure of MH to report survival without a disease flare. This study reported that patients with MH had significantly longer event-free survival (P < .001) compared with patients who did not achieve MH.

Healthcare resource utilization

Eighteen studies reported HCRU outcomes among patients with MH and without MH, among which 9 studies used validated scales (Table 2). Eight studies (3 prospective, 5 retrospective) reporting hospitalization used a validated scale to define MH (SES-CD, 6 studies31,33,35,36,39,44; CDEIS, 1 study30; and Lewis score, 1 study41). Of those 8 studies, 4 studies reported that patients with MH had a lower likelihood of requiring hospitalization.31,35,39,41 Seven studies reporting need for surgery used validated scales to define MH (SES-CD, 6 studies27,31,33,35,39,44; and CDEIS, 1 study30), including 4 studies that reported statistically lower rates of surgery or intestinal resection among patients with MH vs without MH.30,31,39,44

Transmural Healing

Thirteen studies reported long-term outcomes among patients with TH (Table 3), with follow-up time ranging from 12 to 48.5 months. Two studies20,45 did not include both TH and non-TH subgroups and were not included in SLR but are relevant to this review. One was a prospective, multicenter study in Germany45 that compared different definitions of TH (transmural response, simplified TH, extended TH, and complete TH), and the other was a prospective, single-center study in China20 that compared MH and TH. Definitions of TH and specific outcomes differed between included studies (Supplementary Table 3).

| Study Reference (author, year) . | . | Results and significance . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Time (months) | Clinical Remission | Relapse/ recurrence | Treatment Change | Hospitalization | Surgery | Event-free Survival | |

| Oh, 2022 | 18 | NR | Timepoint: median of 18.0 months (IQR, 15.0–21.0) • Relapse/recurrence in 7% of patients (no statistical tests used) | Timepoint: median of 18.0 months (IQR, 15.0-21.0) • Need for anti-TNF dose intensification: 5.3%; Switch to other biologics: 0%; (no statistical tests used) | Timepoint: median of 18.0 months (IQR, 15.0-21.0) • Need for hospitalization across 4 groups was different deep healing, endoscopic healing only, radiologic healing only, and nonhealing (P = .016), with those in the nonhealing group needing the most hospitalization | Timepoint: median of 18.0 months (IQR, 15.0-21.0) • Need for surgery in 0.9% of patients (no statistical tests used) | NR |

| Halle, 2020 | 17 | NR | NR | Median time to treatment adjustment in radiologic responders vs nonresponders: • 173 vs 110 days (P = .39) | Median time to hospitalization in radiologic responders vs nonresponders: • 173 vs 270 days (P = .77) | Median time to surgery or endoscopic procedure in radiologic responders vs nonresponders: • 684 vs 162 days (P = .04) | NR |

| Ma, 2021 | 19 | Timepoint: 19 months TH predicted SFCR: • Multivariate OR = 52.6 (95% CI, 9.7-167.2), P < .001 | NR | Timepoint: 19 months TH associated with lower risk of treatment escalation: • Multivariate OR = 0.1 (95% CI, 0.03-0.4), P = .002 | Timepoint: 19 months TH associated with lower risk of hospitalization: • Multivariate: OR = 0.05 (95% CI, 0.07-0.4), P = .005 | Timepoint: 19 months TH associated with longer time to surgery (P = .03) | NR |

| Messadeg, 2020 | Timepoint: 52 weeks SFCR rate with TM response score ≥2: 84.6% TM response score associated with steroid-free remission • OR: 81.2 (95% CI, 2.6-254.12, P = .012); | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Deepak, 2016 | ≥12 | NR | NR | Timepoint: up to 10 years Multivariate HR = 0.37 (95% CI, 0.21-0.64) P < .001 | Timepoint: up to 10 years Complete response associated with reduced risk of hospitalization vs nonresponse • HR = 0.32 (95% CI, 0.17-0.61), P < .001 | Timepoint: up to 10 years Complete response associated with reduced risk of surgery vs nonresponse • Multivariate HR = 0.27 (95% CI, 0.15-0.48), P < .001 | NR |

| Laterza, 2018 | 36 | NR | NR | Timepoint: up to 36 months No significant differences in therapy adjustment based upon transmural activity stratification at baseline. | Timepoint: up to 36 months Higher transmural activity or more severe clinical activity at baseline required significantly more hospitalizations (all P < .01) | NR | NR |

| Castiglione, 2019 | 12 | Timepoint: 1 year SFCR rate: • TH: 95.6% vs • MH: 75%, P = .01 • NH: 41%, P < .001 TH associated with increased odds of SFCR vs NH: • Multivariate OR = 6.3 (95% CI, 1.5-25.7), P = .01 | Timepoint: 1 year • TH: 4.4% vs • MH: 25%, P = .03 • NH: 59%, P < .001 TH associated with reduced risk of relapse vs NH: • Multivariate OR = 0.02 (95% CI, 0.008‐0.07), P < .001 | Timepoint: 1 year Need for dose escalation • TH: 11.7% vs • MH: 33.3%, P = .005 • NH: 38.8%, P < .001 Need to switch or swap • TH: 10.2% vs • NH: 26.6%, P = .01 | Timepoint: 1 year Need for hospitalization • TH: 8.8% vs • MH: 28.3%, P = .004 • NH: 66.6%, P < .001 TH associated with lower risk of hospitalization vs NH: • Multivariate OR = 0.02 (0.009‐0.09), P < .001) | Timepoint: 1 year 0%, Need for surgery • TH: 0% vs • MH: 10.0%, P = .009 • NH: 35.5%, P < .001 TH associated with lower risk of hospitalization vs NH: • Multivariate OR: 0.1 (0.003‐0.4), P < .001) | NR |

| Paredes, 2019 | 48.5 | NR | NR | Timepoint: 1 year Required corticosteroid therapy: • TH: 0% vs • NH: 10.5%, P = .21 Required treatment intensification: • TH: 3.0% vs • NH: 26.3%, P = .9 | NR | Timepoint: 1 year Surgery rate: • TH: 0% vs • NH: 15.7%, P = .119 | NR |

| Sagami, 2019 | 15 | NR | NR | Incidence of treatment escalation higher for MaRIA score ≥50 than <50 • HR = 2.65 (95% CI, 1.23-5.70), P = .0121 | NR | NR | NR |

| Fernandes, 2017 | 42 | NR | NR | Timepoint: End of study, median: 3.5 years (IQR, 1-7.9) Need for treatment escalation: • TH: 15.2% vs • MH: 36.5%, P = .027 • NH: 54.2%, P < .001 | Timepoint: 1 year Need for hospitalization • TH: 3.0% vs • MH: 17.3%, P = .044 • NH: 24.0%, P = .003 | Timepoint: End of study, Median: 3.5 years (IQR, 1-7.9) Need for surgery • TH: 0% vs • MH: 11.5%, P = .047 • NH: 11.6%, P < .027 | NR |