-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David M Schwartzberg, Maia Kayal, Edward L Barnes, The Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis: Identifying Structural Disorders, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 30, Issue 5, May 2024, Pages 863–867, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad320

Close - Share Icon Share

Lay Summary

Chronic disorders of a pelvic pouch may result from structural complications secondary to postoperative surgical complications which manifest as a variety of symptoms. Knowing the crucial pitfalls of pouch construction can guide treatment options in patients suffering from signs of pouch failure.

Structural Complications

This “Pouch Corner” will examine structural disorders of the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA). Though almost 95% of IPAA patients do well, a minority of them will present with symptoms of pelvic pain/pressure, bowel obstruction, pouchitis, urgency, and perianal fistulae.1–3 These constellations of symptoms can ultimately lead to “pouch failure” (defined as pouch excision, permanent diversion, or redo pouch surgery).4 The timing of symptoms is crucial to determine if an inherit inflammatory condition of the pouch (ie, Crohn’s disease [CD]), or a structural complication (ie, anastomotic leak) is the driving force.5 Although pouch failure is often synonymous with CD, many patients have underlying structural disorders that mimic CD and are the root of any subsequent pathology.6,7 This article will discuss patients with a retained rectum, pouch twist, cuffitis, various anastomotic leaks, small and megapouch, and a straight ileal-anal anastomosis, as well as the common presentations and treatments of patients with structural complications of an IPAA.

Pouch History

To identify structural disorders, it is important to evaluate the evolution of the pelvic pouch and the pitfalls associated with the operation. The surgery itself, the type of pouch (J- vs S-), mucosectomy/handsewn anastomosis vs double-stapled anastomosis, as well as the procedure’s stage (3-stage, 2-stage, modified 2-stage, 1-stage), and the postoperative care are all relevant to guiding the practitioner to successfully distinguish the culprit(s) responsible for the patient’s symptoms.

Parks and Nicholls first published their results on their pelvic pouch in 1978, which was a fully handsewn S-pouch with a handsewn ileal-anal anastomosis.8 The benefits of this pouch were remarkable as it was the first operation that allowed patients the opportunity for life without a stoma, but it had certain inherit complications unique to its pouch design. Firstly, like any S-pouch design, the procedure was laborious, and the many pouch-body suture lines were at risk for anastomotic leak, which could manifest as pelvic sepsis, draining perianal fistulae, or anastomotic strictures. Additionally, specific to S-pouches was the possibility of efferent limb syndrome, caused by the exit conduit that could kink/obstruct on itself (especially if longer than 2 cm) between the pouch and the anal canal.9 With the invention of the linear stapler, Utsunomyia published his results of a fully stapled pouch, a J-pouch, which greatly standardized the procedure.10 The J-pouch would still be subject to pouch-body staple line leaks, but because there was no efferent limb, there was no longer the potential for efferent limb syndrome; however, the tip of J could now be a source of leak. Additionally, a mucosectomy and handsewn anastomosis was standard, which added to the length the bowel needed to reach to the anal canal and subsequently put the anastomosis at risk for a tension-related ischemic anastomotic stricture or leak.11 In 1999, Fazio et al published their results of a double-stapled anastomosis, which now preserved the anal transitional zone (ATZ) and resulted in better overall pouch function and less nighttime anal seepage.12 Additionally, because the ATZ was preserved, there was less distance needed for the pouch to reach the pelvis and thus, less tension on the anal anastomosis. This resulted in a decreased chance of a tension stricture/leak; however, for the first time, there was also the possibility for an incomplete proctectomy and an inadvertent ileal pouch-rectal anastomosis. Acutely, the ongoing proctitis in the retained rectum would manifest as an anastomotic leak, pelvic sepsis, or draining fistulae, and chronically, would result in pouchitis, urgency, and anastomotic strictures—all resembling CD.1 Lastly, the widespread adoption of minimally invasive surgery has led to limited visualization during the ileal-anal anastomosis creation and has rendered pouch-twists increasingly more common.5

Initial Evaluation and History

All previous pathology specimens and operative notes should be reviewed to determine pathology consistent with Crohn’s disease and what type of pouch/anastomosis the patient has. The operative report may have noted the intended omission of a complete proctectomy to allow a tension-free anastomosis by leaving a rectal “cuff,” creating a small pouch (<12 cm), or extensive superior mesenteric mobilization to allow pouch-reach which may have resulted in pouch ischemia.11 The previously mentioned findings are further highlighted by noting the stage(s) of the procedure, as patients without a 3-stage or modified 2-stage did not benefit from mesenteric lengthening before pouch creation which could result in reach issues to the pelvis. Any mention of postoperative complications such as pelvic bleed and sepsis, return to the operating room, percutaneous drainage/trans-anal drainage, or a prolonged time before the protective stoma was reversed would be clues of a structural complication to explain the patient’s symptoms.5 Additionally, many patients will fall into 2 categories: years of excellent pouch function followed by detrimental symptoms (high likelihood of CD), or patients whose symptoms developed immediately after the IPAA/stoma closure (high likelihood of structural complication).2 Radiologic testing is crucial, as cross-sectional imaging can identify anastomotic defects, retained rectum, pouch twist, or proximal small bowel inflammation consistent with CD; and a water-soluble contrast enema can identify anastomotic leak and evidence of afferent loop syndrome.5 Physical exam will note the presence of perianal abscesses/fistulae, and a digital exam can note the presence of an anastomotic stricture. Of utmost importance is the presence of a circular stapled line within 2 cm of the anal verge, as any absence of a staple line may indicate one of 2 things: either the patient had a handsewn anastomosis or they have retained rectum and their anastomosis is in the mid-rectum.

Pouchoscopy

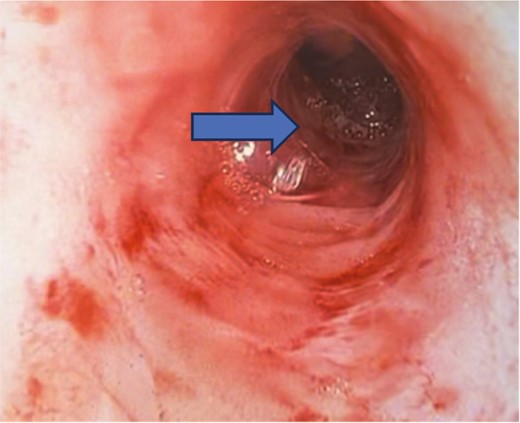

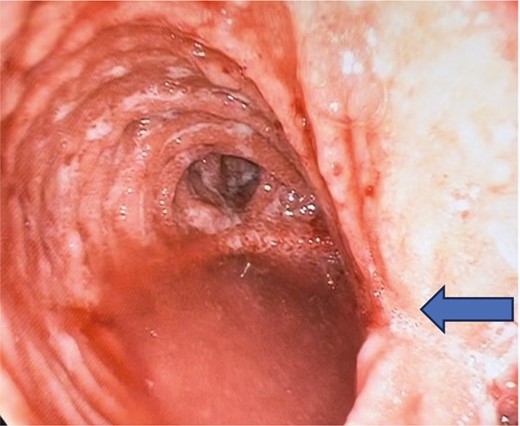

As the scope is passed through the anal canal, the view should be of the pouch body. If there is bowel that must be traversed before entering the pouch, it is either evidence of the efferent limb of an S-pouch or incomplete proctectomy (Figure 1). It should be mentioned that pediatric patients may have a straight ileo-anal anastomosis or a pull-through procedure (often performed for other pediatric conditions) and may lack a pelvic pouch entirely. The pouch body mucosa should be evaluated for pouchitis, ulcers (often along the staple lines as a sign of ischemia), and overt signs of anastomotic leak or inflammatory strictures; and guided biopsies should be taken, as well as effluent sent for pathogen testing (ie, Clostridioides difficile). The staple lines should be seen coming from the anastomosis and traveling anteriorly and posteriorly towards the owl’s eye. If staple lines are seen spiraling towards the owl’s eye or the staple lines are located on the left and right sides of the pouch, it likely is a sign of a pouch twist (Figure 2). Furthermore, the 2 eyes of the owl’s eye should be located next to each other in the pouch’s horizonal plane (supine positioning), but a “stacked” owl’s eye in the vertical plane is a sign of a partial or complete pouch twist (Figure 3). The overall size of the pouch should be noted, and a small pouch or too large pouch (a megapouch) could be responsible for the symptomatology of the patient.9 A normal pouch length is 15-20 cm, and a small pouch will lead to frequent filling and emptying resulting in multiple bowel movements, while a megapouch could be evidence of a distal obstruction or abnormal defecation. The tip of the J should be easily identified and should be healthy and intact, and the proximal small bowel lumen should be patent and readily entered without stricture or severe angulation, which could be signs of inlet stricture and/or afferent limb syndrome (ALS), respecively.13 Although CD can be identifiable in the proximal small bowel, a singular stricture seen between 10-30 cm proximal to the pouch might be sign of a surgical stricture at the prior ileostomy site.

Showing an inadvertent ileal pouch-rectal anastomosis as there is a long segment of retained rectum on pouchoscopy. The ileal pouch begins at the mid-rectum (arrow) and not at the proximal anal canal.

Pouchoscopy on a supine patient with an IPAA, demonstrating a vertically stacked owl’s eye with an almost horizontal staple line, indicative of a partial pouch twist.

Pouchoscopy in a supine patient with an IPAA, showing a mid-pouch body stricture (arrow), pouchitis, signs of a twisted pouch with vertically stacked owl’s eye with corresponding staple lines on the left and right of the patient (not anterior and posterior).

Treatment

In patients who have undergone the appropriate workup and have signs of a structural disorder, a multidisciplinary conversation must be initiated focused on the patient’s desired outcome. This should ideally including a pouch surgeon with experience in revisional pouch surgery, as many structural complications may be corrected with pouch augmentation and diversion-alone or pouch excision should not be the default.14

The treatment of anastomotic leaks is complex, as many occur shortly after IPAA creation, but some may be occult and lead to smoldering pelvic infections that subsequently become chronic pouch dysfunction and fistulae. Leaks occur in 15% of patients and are most located at the pouch-anal anastomosis, followed by the pouch body’s staple lines and lastly, at the tip of the J1. The location and extent of leak dictates the possible medical and surgical curative options; however, pelvic sepsis remains the number one reason for pouch failure.14 Hence, multiple fistula tracts in the perineum are often confused for CD but may just be the result of a chronically draining anastomotic leak.15 A tip of the J leak may undergo endoscopic over-the-scope clip attempts at closing the defect, but ultimately surgical revision of the J-tip will likely be needed.16 Pouch body leaks may respond to antibiotics and even biologic therapy, but ultimately the chronic rind from the ongoing infection might limit the effectiveness of nonoperative approaches.5 Patients with an evacuation disorder secondary to a partial-pouch twist may remain candidates for treatment with dietary changes or endoscopic banding, however a complete twist is truly only amenable to a redo pouch procedure.17,18 Patients with retained rectum fall into a spectrum of treatment options based off associated pathology and the amount of rectum present. Patients with cuffitis might be managed with topical anti-inflammatory medications or biologic medications, but a surgical option of a trans-anal pouch-advancement might be indicated.1,19 Conversely, patients with retained rectum and associated ongoing proctitis, chronic pouchitis, or a recalcitrant anastomotic stricture might need a redo pouch with a formal completion proctectomy and re-anastomosis. Strictures can be seen from a variety of causes—post-surgical, inflammatory, or related to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication use, and many require endoscopic and/or surgical intervention.1 Mild strictures at the anal anastomosis are likely from tension (in the absence of other pathology) and might be amenable to digital or endoscopic dilation.1 Mid-pouch strictures might be amenable to endoscopic stricturotomy, but surgical intervention may be necessary. Pouch inlet strictures might also benefit from dilations; however, the long-term durability is varied, and surgery might be required.1 Patients with an S-pouch and efferent limb syndrome will need surgical undergo revision to shorten the efferent limb and re-anastomose the pouch to the anal canal.9 Afferent limb syndrome is characteristically seen with sharp angulation on pouchoscopy and as bowel trapped between the pouch and sacrum on cross-sectional imaging. The treatment involves mobilizing the pouch and retracting the small bowel out of the pelvis, typically accompanied by performing a pouch pexy to the retroperitoneum to avoid recurrence.13 A patient with a small pouch may also need a revision, as no intervention other than enlarging the pouch will result in the decrease of frequent emptying. Occasionally an elongated tip of the J can be used to enlarge the pouch by enlarging the pouch body, but commonly a new pouch will need to be created in patients with a small pouch.

Conclusion

In summary, patients with pouch dysfunction demand a thorough and time-consuming evaluation, beginning with pathology and operative details, information on postoperative complications, specificities on the timing of pouch dysfunction, cross-sectional imaging, contrast enemas, physical exam, and pouchoscopy. These patients benefit greatly from multidisciplinary care so they may be informed of all relevant treatment options. Many patients with structural disorders will need intervention from endoscopic procedures and/or surgery, and a subset will ultimately require revisional pouch surgery to correct anatomic complications.

Conflicts of Interest

D.S. has nothing to disclose. M.K. has served as a consultant for Pfizer, AbbVie, Bristol Meyers Squibb, and Fresenius. E.B. has served as a consultant for Target RWE.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [K23DK127157].