-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dahham Alsoud, João Sabino, Denis Franchimont, Anneline Cremer, Julie Busschaert, François D’Heygere, Peter Bossuyt, Anne Vijverman, Séverine Vermeire, Marc Ferrante, Real-world Effectiveness and Safety of Risankizumab in Patients with Moderate to Severe Multirefractory Crohn’s Disease: A Belgian Multicentric Cohort Study, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 30, Issue 12, December 2024, Pages 2289–2296, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad315

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As real-world data on risankizumab in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease (CD) are scarce, we evaluated its effectiveness and safety in multirefractory Belgian patients.

Data from consecutive adult CD patients who started risankizumab before April 2023 were retrospectively collected at 6 Belgian centers. Clinical remission and response were defined using the 2-component patient-reported outcome. Endoscopic response was defined as a decrease in baseline Simple Endoscopic Score with ≥50%. Both effectiveness end points were evaluated at week 24 and/or 52, while surgery-free survival and safety were assessed throughout follow-up.

A total of 69 patients (56.5% female, median age 37.2 years, 85.5% exposed to ≥4 different advanced therapies and 98.6% to ustekinumab, 14 with an ostomy) were included. At week 24, 61.8% (34 of 55) and 18.2% (10 of 55) of patients without an ostomy achieved steroid-free clinical response and remission, respectively. At week 52, these numbers were 58.2% (32 of 55) and 27.3% (15 of 55), respectively. Endoscopic data were available in 32 patients, of whom 50.0% (16 of 32) reached endoscopic response within the first 52 weeks. Results in patients with an ostomy were similar (steroid-free clinical response and remission, 42.9% and 14.3%, respectively). During a median follow-up of 68.3 weeks, 18.8% (13 of 69) of patients discontinued risankizumab, and 20.3% (14 of 69) of patients underwent CD-related intestinal resections. The estimated surgery-free survival at week 52 was 75.2%. No new safety issues were observed.

In this real-world cohort of multirefractory CD patients, risankizumab was effective in inducing both clinical remission and endoscopic response. Risankizumab was well tolerated with no safety issues.

Lay Summary

In this real-world study of multirefractory Crohn’s disease patients, risankizumab was effective, with 58.2% and 27.3% achieving steroid-free clinical response and remission, respectively, at week 52. Surgery-free survival at week 52 was 75.2%, and no new safety concerns arose.

Risankizumab demonstrated efficacy and safety for the treatment of moderate to severe Crohn’s disease in recent phase 3 randomized clinical trials.

In this first real-world assessment of week 52 outcomes in multirefractory Crohn’s disease patients starting risankizumab, 58.2% and 27.3% of patients achieved steroid-free clinical response and remission, respectively, with no safety issues.

Risankizumab can be used to induce and maintain remission in Crohn’s disease patients who were refractory to 3 or more biologics or small molecules.

Introduction

In recent years, the therapeutic landscape of Crohn’s disease (CD) has undergone a momentous transformation with the advent of several therapeutic agents that target key inflammatory pathways.1 Despite an improvement in disease outcomes,2 a considerable proportion of patients do not respond adequately to the available therapies, and others lose response over time or develop adverse events.3–5 High rates of treatment failure lead to frequent biologic switches, resulting in the inevitable exhaustion of available therapeutic options in patients with refractory disease. Notably, the efficacy of subsequently administered biologics in patients who underwent multiple biologic cycles (ie, bio-exposed) has been observed to be lower compared with bio-naïve patients.6–8 This reality clearly emphasizes the persistent need for the advent of novel therapeutic agents.

Risankizumab has recently been approved for the treatment of moderate to severe CD. Risankizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that selectively targets the p19 subunit of interleukin (IL)-23, thereby intercepting the inflammatory cascade promoted by this cytokine. Recently, in 3 separate phase 3 randomized clinical trials (RCTs), risankizumab demonstrated efficacy and safety in inducing and maintaining the coprimary end points of clinical remission and endoscopic response in bio-naïve as well as bio-exposed patients with moderate to severe CD.9,10 In a post hoc analysis, risankizumab showed numerically higher efficacy rates compared with placebo, regardless of whether patients were previously exposed to 1, 2, or 3 or more advanced therapies.11

Considering the significant differences between RCTs and real-world populations, it is paramount to report real-world effectiveness and safety data to translate evidence derived from RCTs into clinical practice, bridge knowledge gaps, and facilitate informed therapeutic decisions.12 So far, 2 retrospective studies reported on the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in real-world cohorts of multirefractory CD patients.13,14 However, study end points were evaluated only at an early stage (ie, week 12) and lacked endoscopic assessments.

Therefore, the objective of the current study was to assess the clinical and endoscopic effectiveness of risankizumab in a Belgian multicenter cohort of multirefractory CD patients over a 1-year period. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate the long-term safety profile and surgery-free survival in this cohort throughout the whole exposure period to risankizumab.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This observational retrospective multicenter cohort study was conducted at 6 inflammatory bowel disease centers and is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cohort studies.15 The study protocol was first approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (S-number 66870) and subsequently by the ethics committees of the other participating centers.

Consecutive adult CD patients who started risankizumab via an early access program between October 2019 and April 2023 were screened for eligibility at the 6 participating centers. Included patients should not have been exposed to risankizumab in clinical trials and should have had active disease at the initiation of risankizumab. Active disease was defined as the presence of endoscopic evidence of disease activity (Simple Endoscopic Score for CD [SES-CD] >3 or the presence of ulcers), and/or other objective signs of inflammation (radiological evidence of disease activity, C-reactive protein [CRP] ≥5 mg/L or fecal calprotectin [fcal] ≥250 ug/g). Data collection was terminated on August 16, 2023.

All patients received 3 infusion induction doses of 600 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 8. From week 12 onwards, patients received an 8-weekly subcutaneous maintenance dose of 180 or 360 mg. Initially, only the 180 mg dosing was provided by AbbVie, while after the FORTIFY data became available, most patients received the 360 mg dosing. Dose optimizations were performed at the discretion of the treating physician based on achieved response and subject to approval by AbbVie.

Data Collection

A secure web-based application, REDCap (Vanderbilt University, USA), was utilized to collect data from study subjects, with access granted to all participating centers.16 Questionnaires were constructed to collect data pertaining to patient demographic and disease characteristics, history of CD-related surgeries, previous exposure to biologics or small molecules, risankizumab therapy information, measures of disease activity, reasons for hospitalizations and surgeries during follow-up, and concomitant CD medications and any concomitant biologics or small molecules started for CD or other immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

Patient demographic and disease characteristics included sex, age, disease duration, smoking history, and Montreal classification. History of CD-related surgeries included previous ileocolonic resections and other CD-related intestinal resections. Data on previous and concomitant exposure to biologics or small molecules included the start and end dates of each drug and the reasons for discontinuation. Risankizumab therapy information included induction and maintenance schemes and possible dose optimizations and their reasons, in addition to the date and reasons for eventual discontinuation.

Measures of disease activity were collected at baseline and at weeks 24 and 52, and included endoscopic findings, abdominal pain (AP), and stool frequency (SF) components of patient-reported outcomes,17 physician global assessment (PGA),18 CRP, and fcal.

Therapy Outcomes

In line with the risankizumab phase 3 trials, the coprimary end points for this study were clinical remission and endoscopic response at week 24 and week 52. Clinical remission was defined using the following algorithm: (1) average daily SF ≤2.8 and average daily AP score ≤1 and both not worse than baseline OR if unknown, (2) the impression of the treating physician of a complete relief of symptoms compared with baseline. Clinical response was defined using the following algorithm: (1) ≥30% decrease in average daily SF and/or ≥30% decrease in average daily AP score and both not worse than baseline OR if unknown, (2) the impression of a partial, though significant, improvement of symptoms compared with baseline. Due to the inability to report SF in patients with an ostomy, clinical outcomes were assessed in these patients only using the PGA.18 Steroid-free outcomes were defined as no use of concomitant steroids in the last 4 weeks prior to outcome assessment. Endoscopic response was defined using the following algorithm: (1) ≥50% decrease in baseline SES-CD OR if unknown, (2) decrease in baseline ulcers. Endoscopic remission was defined using the following algorithm: (1) SES-CD <3 OR if unknown, (2) disappearance of baseline ulcers. The frequency of using these different measures of disease activity in evaluating therapy outcomes is reported in the supplementary material online.

Serious adverse events were defined as any adverse event leading to treatment discontinuation, hospitalization, disability, intestinal resection, or death.

Primary nonresponse was defined as the absence of any clinical improvement after drug initiation by week 24, whereas secondary loss of response was defined as clinical deterioration after an initial clinical response.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics of included patients were stated as absolute numbers and percentages for categorical variables and as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs, quartile 1-quartile 3) for continuous variables.

Absolute numbers and percentages of patients meeting clinical response and clinical remission were reported on an intention-to-treat basis. Treatment discontinuation before reaching an assessment time point, whether due to adverse events, inadequate response, loss of response or loss to follow-up, was considered as treatment failure from that time point onward. Patients who continued treatment and adhered to follow-up but did not reach a specific time point due to a shorter treatment duration were excluded from effectiveness analyses at that particular time point. As endoscopic evaluations are typically performed only in a subset of patients in real-life clinical practice, the assessment of endoscopic outcomes was conducted on a per protocol basis. This means that the evaluation was limited to those patients who underwent endoscopic examinations at both baseline and outcome assessment time points. Effectiveness analysis was performed and reported separately for patients without and with an ostomy.

Treatment persistence was defined as time from risankizumab initiation to the last follow-up visit or to the discontinuation of risankizumab for any reason and plotted on a Kaplan-Meier curve. Patients who underwent intestinal resection due to therapy ineffectiveness but continued risankizumab thereafter due to the lack of alternative medical therapies were censored as treatment nonresponders at time of surgery. Incidence rates of serious adverse events were reported including all patients.

Statistical analyses and data visualizations were performed using the R programming language (v. 4.3.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study Population

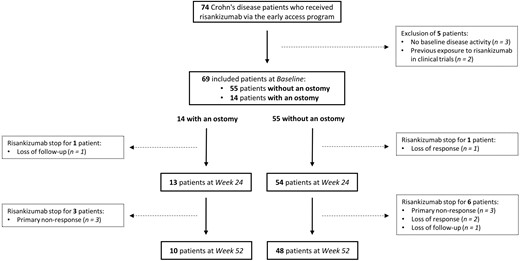

A total of 69 CD patients received risankizumab via the early access program and met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among these included patients, 54 (78.3%) had endoscopically confirmed luminal ulcerations prior to starting risankizumab, while 15 (21.7%) had other objective signs of disease activity (12 patients had elevated fcal and/or CRP, and 3 showed disease activity on cross-sectional imaging).

Flowchart of patients’ inclusion and follow-up through study time points.

Of the included patients, 55 (79.7%) did not have an ostomy at the time of starting risankizumab. All these patients without an ostomy had previously been exposed to at least 2 biologics or small molecules, with 46 (83.6%) and 16 (29.1%) of them having been exposed to at least 4 and 5 different biologics or small molecules, respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, all but 1 patient (98.2%) had prior exposure to ustekinumab, with loss of response being the primary reason for discontinuation in 34 (63.0%) cases. Additionally, 33 (60.0%) patients had undergone at least 1 previous CD-related intestinal resection. At risankizumab initiation, 10 (18.2%) patients had fibrostenosing disease, and 1 patient (1.8%) had penetrating complications. All patients received a 600 mg induction dose at weeks 0, 4,` and 8. For maintenance, 26 (47.3%) and 29 (52.7%) patients started an 8-weekly 180 mg and 360 mg subcutaneous scheme, respectively, and this from week 12 onwards.

| Baseline Characteristic . | Without an Ostomy (n = 55) . | With an Ostomy (n = 14) . |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 32 (58.2) | 7 (50.0) |

| Age (year), Median (IQR) | 39 (30–50) | 34 (26–43) |

| Disease duration (year), Median (IQR) | 17 (10–24) | 16 (11–21) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 8 (14.8) | 2 (14.3) |

| missing, n | 1 | 0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), Median (IQR) | 23.6 (19.7–27.0) | 21.65 (18.9–24.1) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), Median (IQR) | 10 (4–25) | 21 (8–52) |

| missing, n | 6 | 1 |

| Faecal calprotectin (ug/g), Median (IQR) | 955 (484–1800) | 1038 (656–1419) |

| missing, n | 30 | 12 |

| Simple endoscopic score for CD, Median (IQR) | 10 (7–16) | 11 (8–19) |

| missing, n | 19 | 5 |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| < 17 years | 15 (27.3) | 8 (57.1) |

| 17-40 years | 33 (60.0) | 6 (42.9) |

| > 40 years | 7 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disease location, n (%) | ||

| Ileal | 7 (12.7) | 2 (14.3) |

| Colonic | 9 (16.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Ileocolonic | 39 (70.9) | 11 (78.6) |

| Upper GI modifier | 11 (20.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Disease behavior, n (%) | ||

| Inflammatory | 18 (32.7) | 3 (21.4) |

| Fibrostenotic | 25 (45.5) | 7 (50.0) |

| Penetrating | 12 (21.8) | 4 (28.6) |

| Perianal modifier | 24 (43.6) | 10 (71.4) |

| Current fibrostenosing complications, n (%) | 10 (18.2) | 4 (28.6) |

| Current penetrating complications, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (7.1) |

| Previous CD-related intestinal resection, n (%) | 33 (60.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Concomitant corticosteroids, n (%) | ||

| Topical | 8 (14.5) | 1 (7.1) |

| Systemic | 10 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) |

| Concomitant immunomodulators, n (%) | 6 (10.9) | 3 (21.4) |

| Concomitant 5-aminosalicylates, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Concomitant advanced therapies, n (%) | 3 (5.5) | 2 (14.3) |

| Previous number of advanced therapies, n (%) ≥3 | 52 (94.5) | 14 (100.0) |

| ≥4 | 46 (83.6) | 13 (92.9) |

| ≥5 | 16 (29.1) | 5 (35.7) |

| Previous ustekinumab, n (%) | 54 (98.2) | 14 (100.0) |

| Reason for ustekinumab discontinuation, n (%) | ||

| Loss of response | 34 (63.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Primary nonresponse | 20 (37.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Adverse events | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Baseline Characteristic . | Without an Ostomy (n = 55) . | With an Ostomy (n = 14) . |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 32 (58.2) | 7 (50.0) |

| Age (year), Median (IQR) | 39 (30–50) | 34 (26–43) |

| Disease duration (year), Median (IQR) | 17 (10–24) | 16 (11–21) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 8 (14.8) | 2 (14.3) |

| missing, n | 1 | 0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), Median (IQR) | 23.6 (19.7–27.0) | 21.65 (18.9–24.1) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), Median (IQR) | 10 (4–25) | 21 (8–52) |

| missing, n | 6 | 1 |

| Faecal calprotectin (ug/g), Median (IQR) | 955 (484–1800) | 1038 (656–1419) |

| missing, n | 30 | 12 |

| Simple endoscopic score for CD, Median (IQR) | 10 (7–16) | 11 (8–19) |

| missing, n | 19 | 5 |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| < 17 years | 15 (27.3) | 8 (57.1) |

| 17-40 years | 33 (60.0) | 6 (42.9) |

| > 40 years | 7 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disease location, n (%) | ||

| Ileal | 7 (12.7) | 2 (14.3) |

| Colonic | 9 (16.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Ileocolonic | 39 (70.9) | 11 (78.6) |

| Upper GI modifier | 11 (20.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Disease behavior, n (%) | ||

| Inflammatory | 18 (32.7) | 3 (21.4) |

| Fibrostenotic | 25 (45.5) | 7 (50.0) |

| Penetrating | 12 (21.8) | 4 (28.6) |

| Perianal modifier | 24 (43.6) | 10 (71.4) |

| Current fibrostenosing complications, n (%) | 10 (18.2) | 4 (28.6) |

| Current penetrating complications, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (7.1) |

| Previous CD-related intestinal resection, n (%) | 33 (60.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Concomitant corticosteroids, n (%) | ||

| Topical | 8 (14.5) | 1 (7.1) |

| Systemic | 10 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) |

| Concomitant immunomodulators, n (%) | 6 (10.9) | 3 (21.4) |

| Concomitant 5-aminosalicylates, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Concomitant advanced therapies, n (%) | 3 (5.5) | 2 (14.3) |

| Previous number of advanced therapies, n (%) ≥3 | 52 (94.5) | 14 (100.0) |

| ≥4 | 46 (83.6) | 13 (92.9) |

| ≥5 | 16 (29.1) | 5 (35.7) |

| Previous ustekinumab, n (%) | 54 (98.2) | 14 (100.0) |

| Reason for ustekinumab discontinuation, n (%) | ||

| Loss of response | 34 (63.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Primary nonresponse | 20 (37.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Adverse events | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) |

Abbreviations: N, number; IQR, interquartile range; CD, Crohn’s disease

| Baseline Characteristic . | Without an Ostomy (n = 55) . | With an Ostomy (n = 14) . |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 32 (58.2) | 7 (50.0) |

| Age (year), Median (IQR) | 39 (30–50) | 34 (26–43) |

| Disease duration (year), Median (IQR) | 17 (10–24) | 16 (11–21) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 8 (14.8) | 2 (14.3) |

| missing, n | 1 | 0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), Median (IQR) | 23.6 (19.7–27.0) | 21.65 (18.9–24.1) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), Median (IQR) | 10 (4–25) | 21 (8–52) |

| missing, n | 6 | 1 |

| Faecal calprotectin (ug/g), Median (IQR) | 955 (484–1800) | 1038 (656–1419) |

| missing, n | 30 | 12 |

| Simple endoscopic score for CD, Median (IQR) | 10 (7–16) | 11 (8–19) |

| missing, n | 19 | 5 |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| < 17 years | 15 (27.3) | 8 (57.1) |

| 17-40 years | 33 (60.0) | 6 (42.9) |

| > 40 years | 7 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disease location, n (%) | ||

| Ileal | 7 (12.7) | 2 (14.3) |

| Colonic | 9 (16.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Ileocolonic | 39 (70.9) | 11 (78.6) |

| Upper GI modifier | 11 (20.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Disease behavior, n (%) | ||

| Inflammatory | 18 (32.7) | 3 (21.4) |

| Fibrostenotic | 25 (45.5) | 7 (50.0) |

| Penetrating | 12 (21.8) | 4 (28.6) |

| Perianal modifier | 24 (43.6) | 10 (71.4) |

| Current fibrostenosing complications, n (%) | 10 (18.2) | 4 (28.6) |

| Current penetrating complications, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (7.1) |

| Previous CD-related intestinal resection, n (%) | 33 (60.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Concomitant corticosteroids, n (%) | ||

| Topical | 8 (14.5) | 1 (7.1) |

| Systemic | 10 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) |

| Concomitant immunomodulators, n (%) | 6 (10.9) | 3 (21.4) |

| Concomitant 5-aminosalicylates, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Concomitant advanced therapies, n (%) | 3 (5.5) | 2 (14.3) |

| Previous number of advanced therapies, n (%) ≥3 | 52 (94.5) | 14 (100.0) |

| ≥4 | 46 (83.6) | 13 (92.9) |

| ≥5 | 16 (29.1) | 5 (35.7) |

| Previous ustekinumab, n (%) | 54 (98.2) | 14 (100.0) |

| Reason for ustekinumab discontinuation, n (%) | ||

| Loss of response | 34 (63.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Primary nonresponse | 20 (37.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Adverse events | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Baseline Characteristic . | Without an Ostomy (n = 55) . | With an Ostomy (n = 14) . |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 32 (58.2) | 7 (50.0) |

| Age (year), Median (IQR) | 39 (30–50) | 34 (26–43) |

| Disease duration (year), Median (IQR) | 17 (10–24) | 16 (11–21) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 8 (14.8) | 2 (14.3) |

| missing, n | 1 | 0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), Median (IQR) | 23.6 (19.7–27.0) | 21.65 (18.9–24.1) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), Median (IQR) | 10 (4–25) | 21 (8–52) |

| missing, n | 6 | 1 |

| Faecal calprotectin (ug/g), Median (IQR) | 955 (484–1800) | 1038 (656–1419) |

| missing, n | 30 | 12 |

| Simple endoscopic score for CD, Median (IQR) | 10 (7–16) | 11 (8–19) |

| missing, n | 19 | 5 |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| < 17 years | 15 (27.3) | 8 (57.1) |

| 17-40 years | 33 (60.0) | 6 (42.9) |

| > 40 years | 7 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disease location, n (%) | ||

| Ileal | 7 (12.7) | 2 (14.3) |

| Colonic | 9 (16.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Ileocolonic | 39 (70.9) | 11 (78.6) |

| Upper GI modifier | 11 (20.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Disease behavior, n (%) | ||

| Inflammatory | 18 (32.7) | 3 (21.4) |

| Fibrostenotic | 25 (45.5) | 7 (50.0) |

| Penetrating | 12 (21.8) | 4 (28.6) |

| Perianal modifier | 24 (43.6) | 10 (71.4) |

| Current fibrostenosing complications, n (%) | 10 (18.2) | 4 (28.6) |

| Current penetrating complications, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (7.1) |

| Previous CD-related intestinal resection, n (%) | 33 (60.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Concomitant corticosteroids, n (%) | ||

| Topical | 8 (14.5) | 1 (7.1) |

| Systemic | 10 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) |

| Concomitant immunomodulators, n (%) | 6 (10.9) | 3 (21.4) |

| Concomitant 5-aminosalicylates, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Concomitant advanced therapies, n (%) | 3 (5.5) | 2 (14.3) |

| Previous number of advanced therapies, n (%) ≥3 | 52 (94.5) | 14 (100.0) |

| ≥4 | 46 (83.6) | 13 (92.9) |

| ≥5 | 16 (29.1) | 5 (35.7) |

| Previous ustekinumab, n (%) | 54 (98.2) | 14 (100.0) |

| Reason for ustekinumab discontinuation, n (%) | ||

| Loss of response | 34 (63.0) | 8 (57.1) |

| Primary nonresponse | 20 (37.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Adverse events | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) |

Abbreviations: N, number; IQR, interquartile range; CD, Crohn’s disease

Table 1 also summarizes the demographic and disease characteristics of included patients with an ostomy. These patients exhibited a refractory disease profile comparable to that of patients without an ostomy.

Effectiveness Outcomes in Patients Without an Ostomy

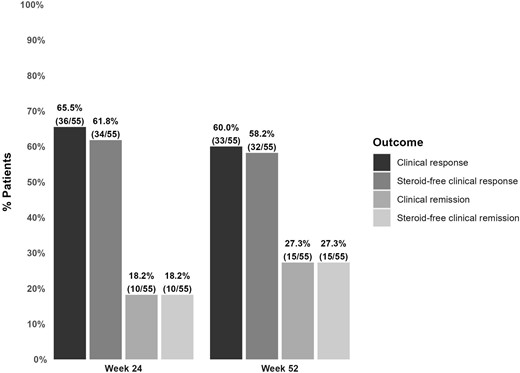

Of the included 55 patients without an ostomy, 10 (18.2%) reached clinical remission at week 24, and all were steroid-free (Figure 2, Table 2). Thirty-four (61.8%) and 36 (65.5%) patients reached steroid-free clinical response and clinical response, respectively.

| Outcome . | Time Point . | Total Number of Patients . | No. Patients Who Stopped RZB or Dropped Out of Follow-up Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Continued RZB but Required Intestinal Resection Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Achieved the Outcome Without Requiring Intestinal Resection . | Percentage of Patients Who Achieved the Outcome on ITT Basis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 61.8% |

| Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 36 | 65.5% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 32 | 58.2% |

| Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 33 | 60.0% |

| Outcome . | Time Point . | Total Number of Patients . | No. Patients Who Stopped RZB or Dropped Out of Follow-up Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Continued RZB but Required Intestinal Resection Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Achieved the Outcome Without Requiring Intestinal Resection . | Percentage of Patients Who Achieved the Outcome on ITT Basis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 61.8% |

| Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 36 | 65.5% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 32 | 58.2% |

| Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 33 | 60.0% |

Abbreviations: RZB, risankizumab; ITT, intention-to-treat

| Outcome . | Time Point . | Total Number of Patients . | No. Patients Who Stopped RZB or Dropped Out of Follow-up Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Continued RZB but Required Intestinal Resection Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Achieved the Outcome Without Requiring Intestinal Resection . | Percentage of Patients Who Achieved the Outcome on ITT Basis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 61.8% |

| Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 36 | 65.5% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 32 | 58.2% |

| Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 33 | 60.0% |

| Outcome . | Time Point . | Total Number of Patients . | No. Patients Who Stopped RZB or Dropped Out of Follow-up Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Continued RZB but Required Intestinal Resection Before the Time Point . | No. Patients Who Achieved the Outcome Without Requiring Intestinal Resection . | Percentage of Patients Who Achieved the Outcome on ITT Basis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 18.2% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 61.8% |

| Clinical Response | Week 24 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 36 | 65.5% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Clinical Remission | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 27.3% |

| Steroid-free Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 32 | 58.2% |

| Clinical Response | Week 52 | 55 | 7 | 3 | 33 | 60.0% |

Abbreviations: RZB, risankizumab; ITT, intention-to-treat

Clinical outcomes of risankizumab in patients without an ostomy.

At week 52, 15 patients (27.3%) were in clinical remission, again all being steroid-free. Thirty-two (58.2%) and 33 (60.0%) patients reached steroid-free clinical response and clinical response, respectively.

Among the 42 patients who underwent an endoscopy prior to risankizumab initiation, 32 patients had endoscopic reassessment during the first 52 weeks of follow-up. Of these patients, 16 (50.0%) achieved endoscopic response, with 2 patients (6.3%) achieving endoscopic remission.

Effectiveness Outcomes in Patients With an Ostomy

Among the included 14 patients with an ostomy, 1 and 7 reached clinical remission and response, respectively, at week 24. At week 52, 2 and 6 patients were in clinical remission and response, respectively. All these patients were steroid-free at these time points.

Out of the 12 patients who underwent a baseline endoscopic assessment, 6 patients had an endoscopy during the first year of follow-up. Four of these 6 patients reached endoscopic response and remission.

Risankizumab Persistence and Dose Optimization in the Overall Population

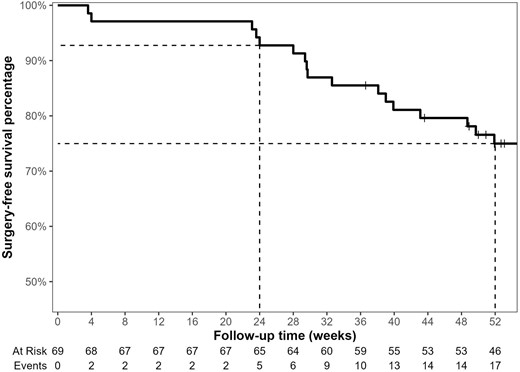

The median follow-up duration in this cohort was 68.3 weeks (IQR, 51.9-98.4). Among all included patients (n = 69), 13 (18.8%) patients discontinued risankizumab after a median of 43.1 weeks (IQR, 29.6-55.9), due to primary nonresponse (n = 6, 46.2%) or secondary loss of response (n = 7, 53.8%). Of these 13 discontinuation incidents, 9 occurred during the first 52 weeks of follow-up. Two other patients were lost to follow-up (1 before week 24, and 1 before week 52). In this multirefractory cohort, the estimated surgery-free survival percentage of risankizumab was 92.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 86.8%-99.1%) and 75.2% (95% CI, 65.6%-86.1%) at week 24 and week 52, respectively (Figure 3).

After a median of 48.7 weeks (IQR, 33.5-61.5), 19 (27.5%) patients had a dose optimization: 17 patients increased their maintenance dose from 180 mg to 360 mg, and 2 patients who were already on a 360 mg maintenance dose had a single intravenous re-induction with 1200 mg. Eleven (57.9%) of these dose optimizations were due to partial inadequate initial response on risankizumab, other 7 (36.8%) were due to loss of response, and 1 (5.3%) due to primary nonresponse. Of these 19 dose optimization cases, 12 occurred during the first 52 weeks of follow-up.

Serious Adverse Events in the Overall Population

No cases of malignancy, deaths, serious or opportunistic infections, or intolerance to risankizumab were reported during follow-up. Eighteen (26.1%) patients required hospitalizations during follow-up, of whom 14 (20.3%) required an intestinal resection. Seven hospitalizations unrelated to surgeries occurred in 6 patients. Three of these were for recurrent subobstruction (conservative approach), 2 for disease flare, 1 for a parastomal abscess, and 1 for severe anemia and syncope.

Discussion

In this observational multicenter cohort of multirefractory CD patients treated with risankizumab, 61.8% and 18.2% of patients without an ostomy achieved steroid-free clinical response and remission, respectively, at week 24. At 52 weeks of follow-up, these numbers were 58.2% and 27.3%, respectively. Thirty-two patients without an ostomy had endoscopic reassessment during the first 52 weeks of follow-up, of whom 50.0% reached endoscopic response. Results in patients with an ostomy were similar, as 42.9% and 14.3% of patients achieved steroid-free clinical response and remission, respectively, at week 52.

In our cohort, all patients were previously exposed to advanced therapies, with 85.5% and 30.4% of them having been exposed to at least 4 and 5 different biologics or small molecules, respectively. These numbers indicate a high level of disease refractoriness, which may explain the lower remission rates observed in our cohort compared with those seen in the registration trials. In the 2 induction RCTs, ADVANCE and MOTIVATE, 43.5% and 34.6% of patients, respectively, achieved steroid-free clinical remission at week 12.9 Notably, 42% of patients in the ADVANCE were bio-naïve, and 47% of patients in the MOTIVATE had been exposed to only one biologic. Looking only at bio-exposed patients in these 2 induction trials, 37.6% of the patients achieved steroid-free clinical remission. Similarly, more patients achieved steroid-free clinical remission at week 52 in the FORTIFY trial (51.8% in the 360 mg arm and 46.5% in the 180 mg arm).10 However, the “responders re-randomization” design of the latter study hinders direct comparison with our study. Nonetheless, rates of clinical response at week 52 in the FORTIFY trial were around 60%, which is similar to the rates observed in our cohort. Hence, the multirefractory CD patients included in our study might require longer therapy duration before achieving clinical remission. Therefore, the current data suggest that risankizumab is an effective therapeutic option for CD patients in whom multiple advanced therapies have failed.

Interestingly, 98.6% of patients in the current study were exposed to ustekinumab compared with less than 20% in the registration trials. This indicates that a previous lack or loss of response to the inhibition of the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 does not preclude a potential response from subsequent selective inhibition of IL-23. Indeed, an RCT in patients with psoriasis showed that patients who had an inadequate response to ustekinumab could still attain significant benefit from switching to a selective IL-23 inhibitor.19 Moreover, a head-to-head efficacy comparison showed that risankizumab had superior efficacy to ustekinumab in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.20 The SEQUENCE trial (NCT04524611) will compare the efficacy of both treatments in adult patients with moderate to severe CD.

In a French retrospective cohort study including 100 multirefractory CD patients, risankizumab induced steroid-free clinical remission in 39.2% of patients at week 12.13 Additionally, risankizumab improved disease symptoms, quality of life, and CRP levels at both week 4 and week 12 in another cohort of 12 CD patients.14 Both studies did not provide outcome assessments at later time points, such as week 24 or week 52. However, included patients in these studies shared a similar refractory profile with those in our cohort. Most of them had previously received 4 advanced therapies and had undergone intestinal surgeries. This corroborates our conclusion that risankizumab is efficacious in patients who were refractory to multiple lines of treatment.

The present study did not reveal any new safety concerns, with the majority of serious adverse events being associated with therapy ineffectiveness and exacerbation of CD symptoms. No cases of injection site reactions, serious or opportunistic infections, malignancy, or deaths were reported. These safety findings align with previous reports from retrospective cohorts.13,14

The objective assessment of disease activity at the time of inclusion and the endoscopic evaluation of treatment outcome in 50% of included patients are strengths of our study. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations imposed by the retrospective design, which may have resulted in misclassification bias in outcomes evaluation. Endoscopic assessments were not consistently scheduled at baseline, week 24, or week 52. As a result, we employed alternative objective measures to determine disease activity at baseline, including CRP, fcal, and cross-sectional imaging. In addition, we reported endoscopic outcomes throughout the entire initial 52 weeks of follow-up, limited to those patients who underwent endoscopic assessments. This approach diverged from the “intention-to-treat” basis we followed when reporting clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the measures used to evaluate endoscopic and clinical outcomes were not standardized among the included patients. As a result, we relied on the reduction in baseline ulcers and PGA for patients for whom SES-CD scores and patient-reported outcomes were not available.

Moreover, the sample size was insufficient to conduct reliable subgroup analyses comparing the 360 mg and 180 mg maintenance dosage groups, nor was it sufficient to assess the association between baseline characteristics and the attainment of effectiveness outcomes. In addition, data were not collected on the progression of perianal disease, its related surgeries, or the outcome of dose optimization. Since most patients who accessed risankizumab through this early access program had already exhausted all other available medical options, the persistence of risankizumab could have been overestimated due to continued use despite the lack of therapeutic benefit. To mitigate this possible bias, we censored all patients who underwent CD-related intestinal resections as nonresponders from the time of surgery onward.

In summary, risankizumab demonstrated safety and effectiveness in inducing and maintaining steroid-free clinical remission and endoscopic response in this cohort of patients with refractory CD. These results provide substantial evidence supporting the consideration of risankizumab as a valuable therapeutic option for patients with moderate to severe CD.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data is available at Inflammatory Bowel Diseases online.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research teams of the participating centers for their effort in collecting the study data. J.S. and M.F. are senior clinical investigators of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), Belgium.

Author Contributions

D.A.: study design, statistical analysis, results interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. J.S., D.F., A.C., J.B., F.D., P.B., A.V., S.V., and M.F.: study design, results interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors agreed with the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

J.S. has received reports research support from Galapagos and Viatris; speaker’s fees from Pfizer, Abbvie, Ferring, Falk, Takeda, Janssen, Fresenius, and Galapagos; consultancy fees from Janssen, Ferring, Fresenius, Abbvie, Galapagos, Celltrion, Pharmacosmos, and Pharmanovia.

D.F. has received educational grants from Abbvie, Takeda and MSD; honoraria fees for lectures or consultancy from Ferring, Falk, Chiesi, Abbvie, MSD, Centocor, Pfizer, Amgen, Janssen, Mundipharma, Takeda, and Hospira.

A.C. has received speaker’s fees from Pfizer, Abbvie, Celltrion, Janssen, and Galapagos; consultancy fees from Takeda, Janssen, Abbvie, and Galapagos.

P.B. has received financial support for research from Abbvie, Amgen, Celltrion, Mylan, Pfizer, and Takeda; lecture fees from AbbVie, Celltrion, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Pentax, and Takeda; advisory board fees from Abbvie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, BMS, Celltrion, Dr Falk, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Pentax, PSI-CRO, Roche, Takeda, and Tetrameros.

S.V. has received grants from AbbVie, J&J, Pfizer, Galapagos, and Takeda; consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Abivax, AbolerIS Pharma, AgomAb, Alimentiv, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Avaxia, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, CVasThera, Dr Falk Pharma, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech-Roche, Gilead, GSK, Hospira, Imidomics, Janssen, J&J, Lilly, Materia Prima, MiroBio, Morphic, MrMHealth, Mundipharma, MSD, Pfizer, Prodigest, Progenity, Prometheus, Robarts Clinical Trials, Second Genome, Shire, Surrozen, Takeda, Theravance, Tillots Pharma AG, and Zealand Pharma.

M.F. has received research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, EG, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda and Viatris; speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Falk, Ferring, Janssen-Cilag, Lamepro, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, Sandoz, Takeda, Truvion Healthcare, and Viatris; consultancy fees from AbbVie, AgomAb Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli-Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Medtronic, MSD, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, Takeda, and Thermo Fisher.

The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Pseudonymized data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. The needed code to reproduce the results, tables, and figures of this article is available on https://dahhamalsoud.github.io/analysis-notebooks/report-realworld-risankizumab-belgium.html.