-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Frank I Scott, Orna Ehrlich, Dallas Wood, Catherine Viator, Carrie Rains, Lisa DiMartino, Jill McArdle, Gabrielle Adams, Lara Barkoff, Jennifer Caudle, Jianfeng Cheng, Jami Kinnucan, Kimberly Persley, Jennifer Sariego, Samir Shah, Caren Heller, David T Rubin, Creation of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease Referral Pathway for Identifying Patients Who Would Benefit From Inflammatory Bowel Disease Specialist Consultation, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 29, Issue 8, August 2023, Pages 1177–1190, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac216

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Recommendations regarding signs and symptoms that should prompt referral of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to an IBD specialist for a consultation could serve to improve the quality of care for these patients. Our aim was to develop a consult care pathway consisting of clinical features related to IBD that should prompt appropriate consultation.

A scoping literature review was performed to identify clinical features that should prompt consultation with an IBD specialist. A panel of 11 experts was convened over 4 meetings to develop a consult care pathway using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Items identified via scoping review were ranked and were divided into major and minor criteria. Additionally, a literature and panel review was conducted assessing potential barriers and facilitators to implementing the consult care pathway.

Of 43 features assessed, 13 were included in the care pathway as major criteria and 15 were included as minor criteria. Experts agreed that stratification into major criteria and minor criteria was appropriate and that 1 major or 2 or more minor criteria should be required to consider consultation. The greatest barrier to implementation was considered to be organizational resource allocation, while endorsements by national gastroenterology and general medicine societies were considered to be the strongest facilitator.

This novel referral care pathway identifies key criteria that could be used to triage patients with IBD who would benefit from IBD specialist consultation. Future research will be required to validate these findings and assess the impact of implementing this pathway in routine IBD-related care.

Lay Summary

This study aimed to develop a care pathway consisting of clinical features that should prompt inflammatory bowel disease expert consultation. A scoping literature review was performed to identify attributes, and an expert panel finalized the structure and components of the pathway.

What is already known: Identifying key criteria that should prompt appropriate and timely triage of individuals with a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to consultation with an IBD specialist remains an unmet need.

What is new here: Using a combination of a scoping literature review and modified RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method, this research identifies 13 major and 15 minor criteria that should prompt consultation with an IBD specialist for individuals with a diagnosis of IBD and highlights potential barriers and facilitators to pathway implementation.

How can this study help patient care: Application of this pathway may serve to improve clinical care and reduce rates of adverse events and healthcare utilization in IBD.

Over 3.1 million Americans experience the 2 primary forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).1 While incidence rates appear to have stabilized in many Westernized countries, estimates and simulations demonstrate that the prevalence of CD and UC will continue to compound over time.2,3 A significant proportion of patients with IBD will require biologic or small-molecule immunosuppressive therapies,4 and overall costs of care, due to these medical therapies as well as to urgent and ancillary care, are estimated to be 3-fold higher than other disease processes and will likely continue to rise.5

Despite an improved range of therapeutic options for IBD, there remain significant challenges in the appropriate diagnosis and management of these disorders. Diagnostic delays remain a significant challenge in both CD and UC and potentially impact the overall trajectory of disease and risks of surgery.6-8 Several studies have demonstrated a median time from symptom onset to diagnosis in CD to extend beyond 10 months, potentially doubling the risk of stricturing disease or surgery for those with the longest delays.9-11 There has subsequently been a significant research effort to identify biochemical or clinical markers that may predict a future diagnosis of IBD to minimize time to diagnosis.12,13 Regarding clinical indices, one of the first efforts to combine predictors to identify those at risk of having undiagnosed IBD was the Red Flags Index, constructed using 3 cohorts of patients with IBD, IBS, and normal control subjects in Europe.13 Initial results demonstrated sensitivity and specificity exceeding 94% for a diagnosis of CD. In a separate validation cohort, however, these clinical criteria performed less well, demonstrating a sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 59%.14 These test characteristics were improved markedly with the addition of fecal calprotectin, however. Another study, IBD-REFER, assessed a combination of major and minor criteria, incorporating inflammatory markers as well as serologic markers such as anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, among a cohort of 200 IBD patients and 100 normal control subjects. Their criteria performed well in a validation exercise using data collected in an Israeli hospital (sensitivity 98%, specificity 96%). The high degree of validation demonstrates that this combined approach of clinical characteristics and baseline laboratory markers may be an ideal future approach for identifying those individuals at risk for an IBD diagnosis.15

Another unmet need for individuals with IBD is ensuring appropriate triage and treatment once diagnosed. Cohort studies have demonstrated that delays in advancing medical care or appropriately initiating biologic therapies are associated with increased risks of adverse outcomes, surgical interventions, and overall costs of care in IBD.16,17 The protean nature of IBD, including its multitude of extraintestinal manifestations, can make identification of signs or symptoms of active disease challenging.18 Further, superimposed irritable bowel syndrome and other functional bowel disorders are common in this population.19 IBD-related care is additionally confounded by increased rates of depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia in this patient population.20 Prior excellent comprehensive care pathway development efforts, such as the American Gastroenterological Association’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Referral pathway, have sought to address these concerns and identify when providers should consider referral to gastroenterologist (GI) providers as well as to ancillary services such as nutrition or mental health services.21 However, there are limited data to date regarding the successful implementation of these guides. Implementation may be further hindered by availability of support resources or access to appropriate subspecialist care. Developing a simplified scale for identifying those who may benefit from referral from GI to IBD specialist for consultation may help in assisting in such stratification.

We aimed to address this gap regarding delays in appropriate triage of individuals with an IBD diagnosis through the development of a consult care pathway to assist GIs in identifying when they should consider referring patients with IBD for consultation with an IBD specialist. To achieve this aim, we employed a scoping literature review and panel elicitation. To facilitate future dissemination and implementation of this consult care pathway, we also used similar methods to identify potential barriers and useful facilitators of forthcoming pathway implementation

Methods

Development of Consult Care Pathway

We sought to develop an easily implementable care pathway to guide GI providers as to when it would be appropriate to consider referring patients with IBD for an IBD specialist consultation. We based the structure of this consult care pathway on the aforementioned IBD-REFER pathway, which divides eligible criteria for referral into 2 groups, group 1 (major criteria) and group 2 (minor criteria),15 and requires at least 1 criterion from the major group or 2 criteria from the minor group. While IBD-REFER was designed for assisting in referral for evaluation for possible IBD, our care pathway was designed explicitly to be used by care providers to assist in deciding when to consult an IBD specialist for individuals with established IBD who may be at significant risk for future disease-related complications. An IBD specialist was defined as a physician or advanced care provider with a career focused on the care of patients with IBD, with access to multidisciplinary surgical, behavioral health, social work, and nutritional support for this patient population.21

The process for determining which factors should be included as criteria in this care pathway was subdivided into 4 steps. First, we conducted a literature review to identify the factors that might be included as criteria in the consult care pathway. Second, we recruited a panel of qualified individuals and experienced stakeholders that included IBD experts, general GIs, primary care providers, and patients to best assess the importance of these factors as potential criteria. Third, we employed a modified UCLA/RAND expert elicitation approach to reach consensus on which factors to include in the consult care pathway and whether factors should be assigned to major or minor criteria.22 Last, to establish a foundation for future dissemination and implementation of our findings, we performed an additional survey and elicitation from the experts and stakeholders to identify barriers and facilitators to future utilization of the finalized consult care pathway. Details for each step of this process are provided subsequently.

Literature Review to Identify Factors for Inclusion in Consult Care Pathway

We conducted a scoping literature review to identify research studies examining clinical factors that should prompt referral of patients with IBD to an IBD specialist for consultation. In contrast to systematic reviews, which are conducted using a systematic search with the goal of appraising and synthesizing the available literature related to a specific topic, scoping reviews are ideally applied in order to determine the scope, volume, and content of existing or emerging evidence on a particular topic wherein synthesis may not be possible.23 The target population for studies included in this scoping review was patients who were diagnosed with IBD.

We defined 2 research questions for this scoping review:

(1) What outcomes trigger concern that patients with IBD are not doing well, that their condition is worsening, or that they are not receiving optimal results of their care? and

(2) What risk factors predict that patients with IBD are not doing well, that their condition is worsening, or that they are not receiving optimal results of their care?

We searched PubMed and Cochrane for original research published in English from January 1, 2013, through February 28, 2021, using search terms related to IBD, referrals, consultation, GIs, and practice guidelines (see Supplemental Methods). Our search yielded 273 peer-reviewed articles. We also reviewed 7 articles and examples of care pathways provided by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation that were not identified in the initial database search, for a total of 280 articles screened. In our full review, we included articles that studied adult (≥18 years of age) IBD patients and assessed existing diagnostic tests, referrals from primary care providers to GIs, or referrals from GIs to IBD specialists. We included studies that evaluated diagnostic tests or criteria, as well as systematic literature reviews and published referral care pathways for IBD patients. We limited articles to those conducted in the United States or in comparable populations (countries categorized as “very high” using the Human Development Index, as defined by the United Nations Development Programme).24 Editorials, letters, or commentaries were not included.

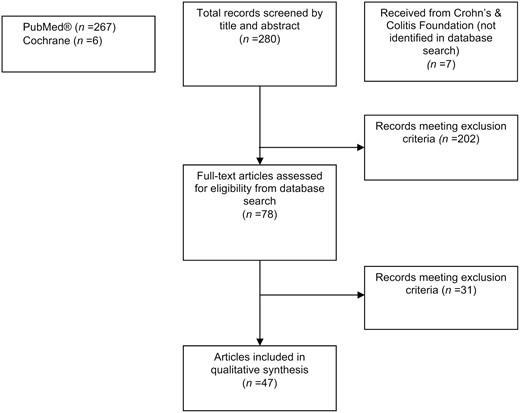

Two reviewers each screened half of the titles and abstracts retrieved from our database search against the inclusion/exclusion criteria (C.R., C.V.). We retrieved the original articles for 78 retained abstracts, and 2 reviewers each conducted a full-text review of half of the articles to further assess eligibility. We then extracted and synthesized the data from 47 articles that met our inclusion criteria in tabular format. (Figure 1). Because this was a scoping review, we did not conduct risk-of-bias or strength-of-evidence assessments, or quantitatively synthesize findings. Using these findings, we developed a list of 43 symptoms, tests, patient characteristics, and treatments/medications that could indicate that a patient with IBD is not doing well or that their condition is worsening.

Flowchart for article search, screening, retrieval, and review for the scoping literature review.

Panel Recruitment, Composition, and Elicitation

We recruited a panel of 11 experienced experts and stakeholders to inform the development of the consult care pathway. We chose to include 11 individuals for 2 reasons. First, choosing an odd number helps avoid ties on questions that are resolved by simple majority vote. Second, the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM) is best implemented with 7 to 15 experts to allow for diversity while giving every panelist an opportunity to participate.22 These individuals included 5 IBD experts, 2 GIs, 2 primary care providers, and 2 patient representatives. Panel members were identified through review by the research team and prior collaborations with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation as well as their individual clinical and research expertise. Panelist selection was intentionally geographically heterogeneous, and no 2 panelists were from the same center or city.

After the panel was recruited, a modified RAM was used in order to reach consensus among panelists for factors to include in the pathway.22 Typically, the RAM reaches consensus on which factors are appropriate for determining whether a medical intervention should be pursued through a 2-round process. First, panelists vote on the appropriateness of each factor on their own. Second, a structured meeting is held in which the appropriateness of each factor is assessed as a group. We modify the typical RAM approach by adding a third round in which a second structured meeting was held to finalize the referral pathway.

Prior to elicitation, panelists were provided with a premeeting survey regarding factors identified in our scoping literature review, listing 64 factors that might influence the decision to refer to an IBD specialist. Additionally, a series of open-ended questions related to this list of factors was also provided. They were also provided with the results of the scoping literature review, including search terms, the factors identified, and citations supporting the assessment of that factor. Last, we provided them with an overview of potential referral pathway structures for discussion. Elicitation was conducted over a total of 4 rounds of online surveys and virtual meetings to evaluate the appropriateness of each factor as a criterion for the consult care pathway, and also to determine in which group each factor belonged. Details on each round of the elicitation are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Results from each round of expert elicitation were used in selecting factors, grouping factors into major and minor criteria, and informing the final pathway selection. Factors were selected for inclusion based on mean ranking scores from the expert panel. Mean scores of 7 or greater on a 10-point Likert scale were considered strongly associated, whereas items with a score of <4 were deemed to not be informative and were rejected. This cutoff was selected based in the distribution of results from Likert rankings.

Initial panel feedback suggested that the clinical context of individual criteria, or in combination with others, could potentially indicate whether it would be appropriate to consider referral. This discussion influenced the subsequent development of major and minor criteria groups, mimicking a structure similar to the previously developed IBD-REFER program.15 Two groups were decided on: major criteria that alone should result in considering IBD specialist referral (group 1) and minor criteria that, when present in combination with each other, should prompt referral (group 2). Factors with an initial median appropriateness score ≥7 were included as major criteria. Factors with a median appropriateness score of 5 to 7 were included as minor criteria and reviewed with the expert panel.

Exploring Pathway Dissemination and Implementation

We also discussed with the panel potential barriers that might inhibit adopting tools like the consult care pathway, and strategies that could be used for pathway dissemination and implementation. We first used implementation science methods to identify potential barriers to adoption as well as potential dissemination and implementation strategies. Next, we conducted an expert elicitation to determine which barriers/strategies were most important (see Supplemental Methods).

Identifying Barriers and Implementation Strategies to Pathway Adoption

Potential barriers were assessed using the Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment questionnaire, a validated questionnaire used to determine how ready an organization is to adopt new practices (see the Supplemental Methods for details).25 Potential dissemination and implementation strategies were identified using the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation as a guide.26 The ERIC is a published compilation of implementation strategy terms and definitions. Strategies were chosen from this guide based on their potential relevance for promoting use of pathway tools in a clinical care setting (see Supplemental Methods for details).26

Elicitation Process

To collect panel opinions regarding barriers and implementation strategies, we conducted 2 online surveys, 1 for IBD-REFER and 1 for the consult care pathway developed during this project. After these data were collected, we analyzed the mean scores to determine which barriers and strategies were considered as most important to panelists. We also conducted a virtual meeting to review survey results with panelists and discuss those barriers to adoption and dissemination and implementation strategies that the majority of panelists agreed or strongly agreed were important. For each of these barriers and strategies, we prepared questions for the panelists to discuss during the meeting to gather qualitative data on how to address the top barriers and how to apply the top dissemination and implementation strategies.

Ethical Considerations

Based on communication with the Office of Research Protection, the Institutional Review Board at RTI International was not required to make a formal determination on this study.

Results

Scoping Review Findings

A total of 280 articles were initially screened in our scoping review (Figure 1). After abstract review, 47 articles were selected for extraction (seeSupplemental Table 1). After full-text review, a total of 43 diagnostic tests, baseline patient demographic factors, healthcare utilization, and signs and symptoms were identified that might predict the need for referral from a GI office to an IBD specialist for consultation (Table 1). These factors and associated references are also listed in Supplemental Tables 1-4.

Factors identified during scoping literature review and basis for initial inclusion

| Factor Type . | Associated With . | References . |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| GI-related bleeding (including hematochezia or melena) | Patients with rectal bleeding are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Blackwell et al, 202027; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Perianal fistula or abscess | Patients with perianal fistulas or abscesses are more likely to have abdominal pain, anemia, early CD-related hospitalization, and referrals with spondyloarthritis to a gastroenterologist. Nonhealing or complex perianal fistula or abscess or perianal lesions (apart from hemorrhoids) are associated with CD diagnosis. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Golovics et al, 201530; Coates et al, 201331; Felice et al, 201928; Sulz et al, 201332; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Penetrating and stricturing disease phenotypes | Increased healthcare utilization has been seen among patients with penetrating and structuring disease phenotypes. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Chronic abdominal pain | Patients with chronic abdominal pain are more likely to have a CD diagnosis and have a referral to the gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Diarrhea | Patients with diarrhea are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis; patients with nocturnal symptoms are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis and be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Danese et al, 201513; Blackwell et al, 20207; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Arthritis or chronic lower back pain | IBD patients with arthritis and lower back pain are more likely to have a high disability score on the IBD Disability Index and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| Weight loss | Patients that have lost 5% of usual body weight in the last 3 months are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| Dactylitis or enthesitis | IBD patients with dactylitis or enthesitis are more likely to receive a referral to the rheumatologist. | Felice et al, 201928 |

| Disease duration | There are high bowel damage scores on the Lémann Index among patients with longer disease durations (measured in years). | Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| History of Clostridioides difficile infection | Patients that have a history of C. difficile infection are correlated with increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Dyspepsia | Dyspepsia is associated with referral to a gastroenterologist and is also included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Pelitari et al, 201837 ; Danese et al, 201513; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Constipation | Constipation is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Jaundice | Jaundice is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Fatty liver | Fatty liver was frequently found in IBD patients undergoing imaging evaluation. | Fousekis et al, 201939; Ho et al, 201640 |

| Nausea/vomiting | Nausea/vomiting can be a significant predictor of clinically significant computed tomography findings in emergency department patients with UC. | Gashin et al, 201541 |

| History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa | History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Risk for malnourishment | Malnourishment has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Fever or night sweats | Fever and night sweats has previously been included in red flag index for early referral of adults with symptoms of CD. | Fiorino et al, 202014; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Signs or laboratory tests | ||

| Elevated FC | Patients with elevated FC are more likely to have anemia, and those with FC levels at RFI ≥8 and/or FC >250 ng/g have a high probability of being identified with CD at an early stage. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Fiorino et al, 202014 |

| Elevated C-reactive protein value | Patients with elevated C-reactive protein have a higher likelihood of having abdominal pain, anemia, hospitalization, and increased healthcare utilization. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Coates et al, 201331; Sulz et al, 201332; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Presence of hypoalbuminemia | Patients with hypoalbuminemia at presentation or the time of UC diagnosis were found to use corticosteroids and a complex IBD hospital admission. | Waljee et al, 201742; Verma et al, 202235; Khan et al, 201743 |

| Higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value | Patients with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value are more likely to experience abdominal pain. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Anemia (as measured by low hemoglobin or low serum ferritin) | Patients with low hemoglobin levels are at higher risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year, while those with CD with higher hemoglobin have a greater chance of remission. | Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Higher Platelet counts | High platelet counts are linked to future hospitalization or steroid use, while low platelet counts are linked to remission among CD patients. | Waljee et al, 201742; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Tachycardia | Patients with baseline tachycardia have been found to have increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Recent liver function tests | Negative predictors of hospitalization included recent liver function tests. | Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Demographic factors | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Patients that are Black or other racial minority have been found to have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup, greater likelihood of corticosteroid use, and morbidity related to medically refractory UC in the ICU. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Khan et al, 201743; Ha et al, 201348 |

| Public insurance | Patients with public insurance have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup and an increased time to colonoscopy. Patients using a medical assistance program also have higher healthcare utilization. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Cigarette smoking | Being a current or former smoker has been found to result in higher healthcare utilization, early IBD-related hospitalization, and CD remission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Golovics et al, 201530; Poncin et al, 201445; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Presence of mental health condition | Patients with moderate-to-severe depression have higher rates of increased healthcare utilization. Patients with a concurrent diagnosis of a mood disorder or a chronic pain disorder are more likely to experience abdominal pain. Patients with any sort of psychiatric illness are at high risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Coates et al, 201331; Limsrivilai et al, 201744 |

| IBS | Patients with abdominal pain are more likely to have IBS. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Age | Younger patients have been found to have higher abdominal pain and corticosteroid use, while older patients have higher likelihood of hospitalization, ICU admittance, outpatient visits, and steroid use. Older patients have also been found to have a shorter time to diagnosis but a longer time to treatment and higher likelihood of CD remission. One study46 found a lower likelihood of IBD-related hospitalization among older patients. | Younger: Coates et al, 201331; Khan et al, 201743 Older: Ha et al, 201348; Hicks et al, 202049; Poncin et al, 201445; Vaughn et al, 201846; Sulz et al, 201332; Waljee et al, 201742 |

| Gender/sex | Female patients with IBD have previously been found to have greater likelihood of needing an outpatient visit and hospitalization. These patients also present with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding. | Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Family history of IBD | There is greater likelihood of CD diagnosis if the patient has a first-degree relative with confirmed IBD. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| BMI | A lower BMI was associated with greater likelihood of CD remission. | Poncin et al, 201445 |

| History of IBD-related medication nonadherence | Nonadherence to IBD medical therapies has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Recent healthcare utilization | ||

| Current or chronic corticosteroid use | Corticosteroid use is associated with high risk for outpatient visits, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year; steroid dependency and resistance are associated with total colectomy; a history of corticosteroids is associated with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding; and early need for steroids is associated with developing advanced disease. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Samuel et al, 201352; Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332; Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Kalkan et al, 201553; Lakatos et al, 201554 |

| Current or prior use of biologic or immunosuppressive therapies for the management of their IBD treatment | Use of biologics at enrollment has been associated with outpatient visits and hospitalization. Immunosuppressive medication use has been associated with increased stool frequency, rectal bleeding, more outpatient visits, steroid use, and future hospitalization; however, it has also been associated with reduced risk of surgery and CD remission. | Sulz et al, 201332; Golovics et al, 201530; Nam et al, 202150; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034; Waljee et al, 201742; Sulz et al, 201332; Poncin et al, 201445; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Use of opioids | The use of opioids has been associated with higher use of the emergency department and inpatient hospital stays. | Park et al, 20205 |

| Increased urgent, emergency, or inpatient healthcare utilization | Two or more GI-related emergency department visits in the past 6 months has been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Presence of a stoma | If a patient has a stoma, there is greater likelihood of high healthcare utilization. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Prior IBD-related surgeries (eg, colectomy, bowel resection, anastomosis) | Prior IBD-related surgeries has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Factor Type . | Associated With . | References . |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| GI-related bleeding (including hematochezia or melena) | Patients with rectal bleeding are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Blackwell et al, 202027; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Perianal fistula or abscess | Patients with perianal fistulas or abscesses are more likely to have abdominal pain, anemia, early CD-related hospitalization, and referrals with spondyloarthritis to a gastroenterologist. Nonhealing or complex perianal fistula or abscess or perianal lesions (apart from hemorrhoids) are associated with CD diagnosis. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Golovics et al, 201530; Coates et al, 201331; Felice et al, 201928; Sulz et al, 201332; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Penetrating and stricturing disease phenotypes | Increased healthcare utilization has been seen among patients with penetrating and structuring disease phenotypes. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Chronic abdominal pain | Patients with chronic abdominal pain are more likely to have a CD diagnosis and have a referral to the gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Diarrhea | Patients with diarrhea are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis; patients with nocturnal symptoms are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis and be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Danese et al, 201513; Blackwell et al, 20207; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Arthritis or chronic lower back pain | IBD patients with arthritis and lower back pain are more likely to have a high disability score on the IBD Disability Index and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| Weight loss | Patients that have lost 5% of usual body weight in the last 3 months are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| Dactylitis or enthesitis | IBD patients with dactylitis or enthesitis are more likely to receive a referral to the rheumatologist. | Felice et al, 201928 |

| Disease duration | There are high bowel damage scores on the Lémann Index among patients with longer disease durations (measured in years). | Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| History of Clostridioides difficile infection | Patients that have a history of C. difficile infection are correlated with increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Dyspepsia | Dyspepsia is associated with referral to a gastroenterologist and is also included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Pelitari et al, 201837 ; Danese et al, 201513; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Constipation | Constipation is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Jaundice | Jaundice is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Fatty liver | Fatty liver was frequently found in IBD patients undergoing imaging evaluation. | Fousekis et al, 201939; Ho et al, 201640 |

| Nausea/vomiting | Nausea/vomiting can be a significant predictor of clinically significant computed tomography findings in emergency department patients with UC. | Gashin et al, 201541 |

| History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa | History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Risk for malnourishment | Malnourishment has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Fever or night sweats | Fever and night sweats has previously been included in red flag index for early referral of adults with symptoms of CD. | Fiorino et al, 202014; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Signs or laboratory tests | ||

| Elevated FC | Patients with elevated FC are more likely to have anemia, and those with FC levels at RFI ≥8 and/or FC >250 ng/g have a high probability of being identified with CD at an early stage. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Fiorino et al, 202014 |

| Elevated C-reactive protein value | Patients with elevated C-reactive protein have a higher likelihood of having abdominal pain, anemia, hospitalization, and increased healthcare utilization. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Coates et al, 201331; Sulz et al, 201332; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Presence of hypoalbuminemia | Patients with hypoalbuminemia at presentation or the time of UC diagnosis were found to use corticosteroids and a complex IBD hospital admission. | Waljee et al, 201742; Verma et al, 202235; Khan et al, 201743 |

| Higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value | Patients with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value are more likely to experience abdominal pain. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Anemia (as measured by low hemoglobin or low serum ferritin) | Patients with low hemoglobin levels are at higher risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year, while those with CD with higher hemoglobin have a greater chance of remission. | Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Higher Platelet counts | High platelet counts are linked to future hospitalization or steroid use, while low platelet counts are linked to remission among CD patients. | Waljee et al, 201742; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Tachycardia | Patients with baseline tachycardia have been found to have increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Recent liver function tests | Negative predictors of hospitalization included recent liver function tests. | Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Demographic factors | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Patients that are Black or other racial minority have been found to have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup, greater likelihood of corticosteroid use, and morbidity related to medically refractory UC in the ICU. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Khan et al, 201743; Ha et al, 201348 |

| Public insurance | Patients with public insurance have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup and an increased time to colonoscopy. Patients using a medical assistance program also have higher healthcare utilization. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Cigarette smoking | Being a current or former smoker has been found to result in higher healthcare utilization, early IBD-related hospitalization, and CD remission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Golovics et al, 201530; Poncin et al, 201445; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Presence of mental health condition | Patients with moderate-to-severe depression have higher rates of increased healthcare utilization. Patients with a concurrent diagnosis of a mood disorder or a chronic pain disorder are more likely to experience abdominal pain. Patients with any sort of psychiatric illness are at high risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Coates et al, 201331; Limsrivilai et al, 201744 |

| IBS | Patients with abdominal pain are more likely to have IBS. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Age | Younger patients have been found to have higher abdominal pain and corticosteroid use, while older patients have higher likelihood of hospitalization, ICU admittance, outpatient visits, and steroid use. Older patients have also been found to have a shorter time to diagnosis but a longer time to treatment and higher likelihood of CD remission. One study46 found a lower likelihood of IBD-related hospitalization among older patients. | Younger: Coates et al, 201331; Khan et al, 201743 Older: Ha et al, 201348; Hicks et al, 202049; Poncin et al, 201445; Vaughn et al, 201846; Sulz et al, 201332; Waljee et al, 201742 |

| Gender/sex | Female patients with IBD have previously been found to have greater likelihood of needing an outpatient visit and hospitalization. These patients also present with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding. | Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Family history of IBD | There is greater likelihood of CD diagnosis if the patient has a first-degree relative with confirmed IBD. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| BMI | A lower BMI was associated with greater likelihood of CD remission. | Poncin et al, 201445 |

| History of IBD-related medication nonadherence | Nonadherence to IBD medical therapies has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Recent healthcare utilization | ||

| Current or chronic corticosteroid use | Corticosteroid use is associated with high risk for outpatient visits, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year; steroid dependency and resistance are associated with total colectomy; a history of corticosteroids is associated with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding; and early need for steroids is associated with developing advanced disease. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Samuel et al, 201352; Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332; Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Kalkan et al, 201553; Lakatos et al, 201554 |

| Current or prior use of biologic or immunosuppressive therapies for the management of their IBD treatment | Use of biologics at enrollment has been associated with outpatient visits and hospitalization. Immunosuppressive medication use has been associated with increased stool frequency, rectal bleeding, more outpatient visits, steroid use, and future hospitalization; however, it has also been associated with reduced risk of surgery and CD remission. | Sulz et al, 201332; Golovics et al, 201530; Nam et al, 202150; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034; Waljee et al, 201742; Sulz et al, 201332; Poncin et al, 201445; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Use of opioids | The use of opioids has been associated with higher use of the emergency department and inpatient hospital stays. | Park et al, 20205 |

| Increased urgent, emergency, or inpatient healthcare utilization | Two or more GI-related emergency department visits in the past 6 months has been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Presence of a stoma | If a patient has a stoma, there is greater likelihood of high healthcare utilization. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Prior IBD-related surgeries (eg, colectomy, bowel resection, anastomosis) | Prior IBD-related surgeries has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CD, Crohn’s disease; FC, fecal calprotectin; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Factors identified during scoping literature review and basis for initial inclusion

| Factor Type . | Associated With . | References . |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| GI-related bleeding (including hematochezia or melena) | Patients with rectal bleeding are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Blackwell et al, 202027; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Perianal fistula or abscess | Patients with perianal fistulas or abscesses are more likely to have abdominal pain, anemia, early CD-related hospitalization, and referrals with spondyloarthritis to a gastroenterologist. Nonhealing or complex perianal fistula or abscess or perianal lesions (apart from hemorrhoids) are associated with CD diagnosis. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Golovics et al, 201530; Coates et al, 201331; Felice et al, 201928; Sulz et al, 201332; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Penetrating and stricturing disease phenotypes | Increased healthcare utilization has been seen among patients with penetrating and structuring disease phenotypes. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Chronic abdominal pain | Patients with chronic abdominal pain are more likely to have a CD diagnosis and have a referral to the gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Diarrhea | Patients with diarrhea are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis; patients with nocturnal symptoms are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis and be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Danese et al, 201513; Blackwell et al, 20207; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Arthritis or chronic lower back pain | IBD patients with arthritis and lower back pain are more likely to have a high disability score on the IBD Disability Index and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| Weight loss | Patients that have lost 5% of usual body weight in the last 3 months are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| Dactylitis or enthesitis | IBD patients with dactylitis or enthesitis are more likely to receive a referral to the rheumatologist. | Felice et al, 201928 |

| Disease duration | There are high bowel damage scores on the Lémann Index among patients with longer disease durations (measured in years). | Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| History of Clostridioides difficile infection | Patients that have a history of C. difficile infection are correlated with increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Dyspepsia | Dyspepsia is associated with referral to a gastroenterologist and is also included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Pelitari et al, 201837 ; Danese et al, 201513; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Constipation | Constipation is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Jaundice | Jaundice is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Fatty liver | Fatty liver was frequently found in IBD patients undergoing imaging evaluation. | Fousekis et al, 201939; Ho et al, 201640 |

| Nausea/vomiting | Nausea/vomiting can be a significant predictor of clinically significant computed tomography findings in emergency department patients with UC. | Gashin et al, 201541 |

| History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa | History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Risk for malnourishment | Malnourishment has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Fever or night sweats | Fever and night sweats has previously been included in red flag index for early referral of adults with symptoms of CD. | Fiorino et al, 202014; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Signs or laboratory tests | ||

| Elevated FC | Patients with elevated FC are more likely to have anemia, and those with FC levels at RFI ≥8 and/or FC >250 ng/g have a high probability of being identified with CD at an early stage. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Fiorino et al, 202014 |

| Elevated C-reactive protein value | Patients with elevated C-reactive protein have a higher likelihood of having abdominal pain, anemia, hospitalization, and increased healthcare utilization. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Coates et al, 201331; Sulz et al, 201332; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Presence of hypoalbuminemia | Patients with hypoalbuminemia at presentation or the time of UC diagnosis were found to use corticosteroids and a complex IBD hospital admission. | Waljee et al, 201742; Verma et al, 202235; Khan et al, 201743 |

| Higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value | Patients with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value are more likely to experience abdominal pain. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Anemia (as measured by low hemoglobin or low serum ferritin) | Patients with low hemoglobin levels are at higher risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year, while those with CD with higher hemoglobin have a greater chance of remission. | Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Higher Platelet counts | High platelet counts are linked to future hospitalization or steroid use, while low platelet counts are linked to remission among CD patients. | Waljee et al, 201742; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Tachycardia | Patients with baseline tachycardia have been found to have increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Recent liver function tests | Negative predictors of hospitalization included recent liver function tests. | Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Demographic factors | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Patients that are Black or other racial minority have been found to have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup, greater likelihood of corticosteroid use, and morbidity related to medically refractory UC in the ICU. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Khan et al, 201743; Ha et al, 201348 |

| Public insurance | Patients with public insurance have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup and an increased time to colonoscopy. Patients using a medical assistance program also have higher healthcare utilization. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Cigarette smoking | Being a current or former smoker has been found to result in higher healthcare utilization, early IBD-related hospitalization, and CD remission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Golovics et al, 201530; Poncin et al, 201445; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Presence of mental health condition | Patients with moderate-to-severe depression have higher rates of increased healthcare utilization. Patients with a concurrent diagnosis of a mood disorder or a chronic pain disorder are more likely to experience abdominal pain. Patients with any sort of psychiatric illness are at high risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Coates et al, 201331; Limsrivilai et al, 201744 |

| IBS | Patients with abdominal pain are more likely to have IBS. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Age | Younger patients have been found to have higher abdominal pain and corticosteroid use, while older patients have higher likelihood of hospitalization, ICU admittance, outpatient visits, and steroid use. Older patients have also been found to have a shorter time to diagnosis but a longer time to treatment and higher likelihood of CD remission. One study46 found a lower likelihood of IBD-related hospitalization among older patients. | Younger: Coates et al, 201331; Khan et al, 201743 Older: Ha et al, 201348; Hicks et al, 202049; Poncin et al, 201445; Vaughn et al, 201846; Sulz et al, 201332; Waljee et al, 201742 |

| Gender/sex | Female patients with IBD have previously been found to have greater likelihood of needing an outpatient visit and hospitalization. These patients also present with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding. | Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Family history of IBD | There is greater likelihood of CD diagnosis if the patient has a first-degree relative with confirmed IBD. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| BMI | A lower BMI was associated with greater likelihood of CD remission. | Poncin et al, 201445 |

| History of IBD-related medication nonadherence | Nonadherence to IBD medical therapies has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Recent healthcare utilization | ||

| Current or chronic corticosteroid use | Corticosteroid use is associated with high risk for outpatient visits, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year; steroid dependency and resistance are associated with total colectomy; a history of corticosteroids is associated with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding; and early need for steroids is associated with developing advanced disease. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Samuel et al, 201352; Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332; Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Kalkan et al, 201553; Lakatos et al, 201554 |

| Current or prior use of biologic or immunosuppressive therapies for the management of their IBD treatment | Use of biologics at enrollment has been associated with outpatient visits and hospitalization. Immunosuppressive medication use has been associated with increased stool frequency, rectal bleeding, more outpatient visits, steroid use, and future hospitalization; however, it has also been associated with reduced risk of surgery and CD remission. | Sulz et al, 201332; Golovics et al, 201530; Nam et al, 202150; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034; Waljee et al, 201742; Sulz et al, 201332; Poncin et al, 201445; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Use of opioids | The use of opioids has been associated with higher use of the emergency department and inpatient hospital stays. | Park et al, 20205 |

| Increased urgent, emergency, or inpatient healthcare utilization | Two or more GI-related emergency department visits in the past 6 months has been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Presence of a stoma | If a patient has a stoma, there is greater likelihood of high healthcare utilization. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Prior IBD-related surgeries (eg, colectomy, bowel resection, anastomosis) | Prior IBD-related surgeries has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Factor Type . | Associated With . | References . |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| GI-related bleeding (including hematochezia or melena) | Patients with rectal bleeding are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Blackwell et al, 202027; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Perianal fistula or abscess | Patients with perianal fistulas or abscesses are more likely to have abdominal pain, anemia, early CD-related hospitalization, and referrals with spondyloarthritis to a gastroenterologist. Nonhealing or complex perianal fistula or abscess or perianal lesions (apart from hemorrhoids) are associated with CD diagnosis. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Golovics et al, 201530; Coates et al, 201331; Felice et al, 201928; Sulz et al, 201332; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Penetrating and stricturing disease phenotypes | Increased healthcare utilization has been seen among patients with penetrating and structuring disease phenotypes. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Chronic abdominal pain | Patients with chronic abdominal pain are more likely to have a CD diagnosis and have a referral to the gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Diarrhea | Patients with diarrhea are more likely to have 6-18 mo of symptoms before diagnosis; patients with nocturnal symptoms are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis and be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Danese et al, 201513; Blackwell et al, 20207; Felice et al, 201928 |

| Arthritis or chronic lower back pain | IBD patients with arthritis and lower back pain are more likely to have a high disability score on the IBD Disability Index and are more likely to be referred to a gastroenterologist. | Felice et al, 201928; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| Weight loss | Patients that have lost 5% of usual body weight in the last 3 months are more likely to receive a CD diagnosis. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| Dactylitis or enthesitis | IBD patients with dactylitis or enthesitis are more likely to receive a referral to the rheumatologist. | Felice et al, 201928 |

| Disease duration | There are high bowel damage scores on the Lémann Index among patients with longer disease durations (measured in years). | Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034 |

| History of Clostridioides difficile infection | Patients that have a history of C. difficile infection are correlated with increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Dyspepsia | Dyspepsia is associated with referral to a gastroenterologist and is also included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Pelitari et al, 201837 ; Danese et al, 201513; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Constipation | Constipation is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Jaundice | Jaundice is included as an indication for referral to gastroenterology services in previous clinical guidelines. | Eskeland et al, 201836; Eskeland et al, 201638 |

| Fatty liver | Fatty liver was frequently found in IBD patients undergoing imaging evaluation. | Fousekis et al, 201939; Ho et al, 201640 |

| Nausea/vomiting | Nausea/vomiting can be a significant predictor of clinically significant computed tomography findings in emergency department patients with UC. | Gashin et al, 201541 |

| History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa | History of deep ulcers of the GI mucosa has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Risk for malnourishment | Malnourishment has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Fever or night sweats | Fever and night sweats has previously been included in red flag index for early referral of adults with symptoms of CD. | Fiorino et al, 202014; Danese et al, 201513 |

| Signs or laboratory tests | ||

| Elevated FC | Patients with elevated FC are more likely to have anemia, and those with FC levels at RFI ≥8 and/or FC >250 ng/g have a high probability of being identified with CD at an early stage. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Fiorino et al, 202014 |

| Elevated C-reactive protein value | Patients with elevated C-reactive protein have a higher likelihood of having abdominal pain, anemia, hospitalization, and increased healthcare utilization. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Coates et al, 201331; Sulz et al, 201332; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Presence of hypoalbuminemia | Patients with hypoalbuminemia at presentation or the time of UC diagnosis were found to use corticosteroids and a complex IBD hospital admission. | Waljee et al, 201742; Verma et al, 202235; Khan et al, 201743 |

| Higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value | Patients with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate value are more likely to experience abdominal pain. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Anemia (as measured by low hemoglobin or low serum ferritin) | Patients with low hemoglobin levels are at higher risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year, while those with CD with higher hemoglobin have a greater chance of remission. | Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Higher Platelet counts | High platelet counts are linked to future hospitalization or steroid use, while low platelet counts are linked to remission among CD patients. | Waljee et al, 201742; Poncin et al, 201445 |

| Tachycardia | Patients with baseline tachycardia have been found to have increased healthcare utilization and complex IBD hospital admission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Verma et al, 202235 |

| Recent liver function tests | Negative predictors of hospitalization included recent liver function tests. | Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Demographic factors | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Patients that are Black or other racial minority have been found to have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup, greater likelihood of corticosteroid use, and morbidity related to medically refractory UC in the ICU. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Khan et al, 201743; Ha et al, 201348 |

| Public insurance | Patients with public insurance have decreased odds of having an appropriate workup and an increased time to colonoscopy. Patients using a medical assistance program also have higher healthcare utilization. | Anyane-Yeboa et al, 202047; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Cigarette smoking | Being a current or former smoker has been found to result in higher healthcare utilization, early IBD-related hospitalization, and CD remission. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Golovics et al, 201530; Poncin et al, 201445; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Presence of mental health condition | Patients with moderate-to-severe depression have higher rates of increased healthcare utilization. Patients with a concurrent diagnosis of a mood disorder or a chronic pain disorder are more likely to experience abdominal pain. Patients with any sort of psychiatric illness are at high risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Coates et al, 201331; Limsrivilai et al, 201744 |

| IBS | Patients with abdominal pain are more likely to have IBS. | Coates et al, 201331 |

| Age | Younger patients have been found to have higher abdominal pain and corticosteroid use, while older patients have higher likelihood of hospitalization, ICU admittance, outpatient visits, and steroid use. Older patients have also been found to have a shorter time to diagnosis but a longer time to treatment and higher likelihood of CD remission. One study46 found a lower likelihood of IBD-related hospitalization among older patients. | Younger: Coates et al, 201331; Khan et al, 201743 Older: Ha et al, 201348; Hicks et al, 202049; Poncin et al, 201445; Vaughn et al, 201846; Sulz et al, 201332; Waljee et al, 201742 |

| Gender/sex | Female patients with IBD have previously been found to have greater likelihood of needing an outpatient visit and hospitalization. These patients also present with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding. | Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332 |

| Family history of IBD | There is greater likelihood of CD diagnosis if the patient has a first-degree relative with confirmed IBD. | Danese et al, 201513 |

| BMI | A lower BMI was associated with greater likelihood of CD remission. | Poncin et al, 201445 |

| History of IBD-related medication nonadherence | Nonadherence to IBD medical therapies has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Recent healthcare utilization | ||

| Current or chronic corticosteroid use | Corticosteroid use is associated with high risk for outpatient visits, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges in the next year; steroid dependency and resistance are associated with total colectomy; a history of corticosteroids is associated with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding; and early need for steroids is associated with developing advanced disease. | Al Khoury et al, 202029; Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Samuel et al, 201352; Nam et al, 202150; Sulz et al, 201332; Limsrivilai et al, 201744; Kalkan et al, 201553; Lakatos et al, 201554 |

| Current or prior use of biologic or immunosuppressive therapies for the management of their IBD treatment | Use of biologics at enrollment has been associated with outpatient visits and hospitalization. Immunosuppressive medication use has been associated with increased stool frequency, rectal bleeding, more outpatient visits, steroid use, and future hospitalization; however, it has also been associated with reduced risk of surgery and CD remission. | Sulz et al, 201332; Golovics et al, 201530; Nam et al, 202150; Lauriot dit Prevost et al, 202034; Waljee et al, 201742; Sulz et al, 201332; Poncin et al, 201445; Matsumoto et al, 201451; Vaughn et al, 201846 |

| Use of opioids | The use of opioids has been associated with higher use of the emergency department and inpatient hospital stays. | Park et al, 20205 |

| Increased urgent, emergency, or inpatient healthcare utilization | Two or more GI-related emergency department visits in the past 6 months has been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

| Presence of a stoma | If a patient has a stoma, there is greater likelihood of high healthcare utilization. | Chudy-Onwugaje et al, 202133 |

| Prior IBD-related surgeries (eg, colectomy, bowel resection, anastomosis) | Prior IBD-related surgeries has previously been included in other IBD referral care pathways. | Kinnucan et al, 201921 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CD, Crohn’s disease; FC, fecal calprotectin; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Expert Elicitation

Initial Major (Group 1) and Minor (Group 2) Criteria Selection by Expert Panel

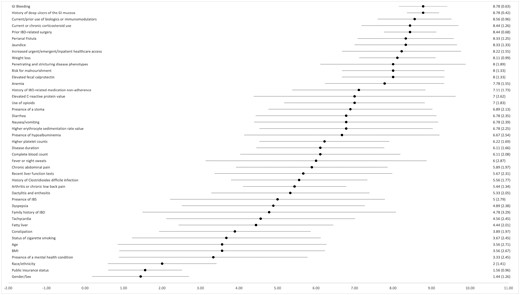

On initial survey, several factors were widely accepted by the panel as being appropriate for consideration as referral criteria in the consult care pathway (Figure 2). Factors that were agreed upon on the initial survey included GI-related bleeding (mean score = 8.78), history of deep ulcers on endoscopy (mean score = 8.78), current or chronic corticosteroid use (mean score = 8.44) or biologic/immunomodulator use (mean score = 8.56), prior IBD-related surgery (mean score = 8.44), perianal fistula (mean score = 8.33), jaundice (mean score = 8.33), increased urgent or emergent care utilization (mean score = 8.22), weight loss (mean score = 8.11) or risk of malnutrition (mean score = 8.00), penetrating or stricturing disease (mean score = 8.00), elevated fecal calprotectin (mean score = 8.00), and anemia (mean score = 7.78). Conversely, several factors were not considered appropriate for inclusion in the consult care pathway, including gender/sex (mean score = 1.44), use of public insurance (mean score = 1.56), race/ethnicity (mean score = 2.00), history of mental health diagnosis (mean score = 3.33), and cigarette smoking status (mean score = 3.67).

Rating of factors for inclusion in consult care pathway through surveys to expert panel. Factors derived from the scoping review were assessed through surveys in expert elicitation and assigned a score of 1 through 9. Mean scores >7 were included, while those <5 were excluded. BMI, body mass index; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Several factors for which there was no clear consensus were discussed individually among the panel to determine whether they should be included as individual criteria, including symptoms of chronic abdominal pain; joint-related symptoms, such as arthritis, joint pain, or back pain, dyspepsia, constipation, and nausea or vomiting; laboratory factors including elevated C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytosis, elevated liver function tests, or hypoalbuminemia; and disease-related factors including disease duration or history of Clostridioides difficile infection. However, upon review during our initial panel elicitation, clinical factors including abdominal pain, arthritis, dyspepsia, constipation, nausea or vomiting, disease duration, and history of C. difficile infection were considered inappropriate for inclusion as isolated criteria for referral to a specialist for consultation.

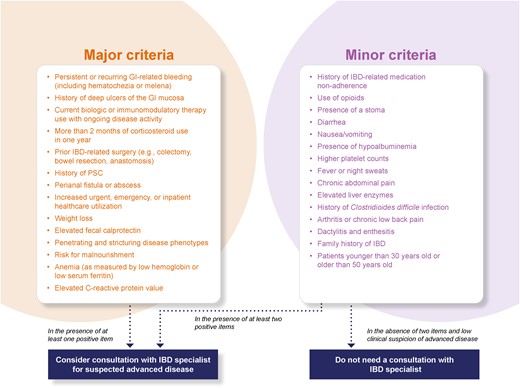

Stratification of Criteria Into 2 Groups and Pathway Finalization

Based on panel feedback, criteria were stratified into major criteria (median appropriateness score ≥7) and minor criteria (median appropriateness score of 5-7). Several factors previously noted for exclusion during the initial meetings were reviewed, including disease duration, diagnosis of IBS or dyspepsia, family history of IBD, tachycardia, fatty liver, constipation, age, and body mass index. After surveying the expert panel, <30 or >50 years of age and family history of IBD were added as minor criteria.

The final pathway was then sent to the full panel for review (Figure 3) and unanimously agreed upon to be appropriate. The panel was asked to confirm whether the finalized consult care pathway was supported by best available evidence, and to provide a score of the strength from 1 (very weak evidence) to 5 (very strong evidence). There was universal agreement that the IBD consult care pathway was supported by the literature (mean score = 4.2). All panelists agreed that the presence of at least 1 major criteria or the presence of at least 2 minor criteria should suggest the need for referral for consultation.

Final consult care pathway after scoping review and several rounds of expert elicitation. GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

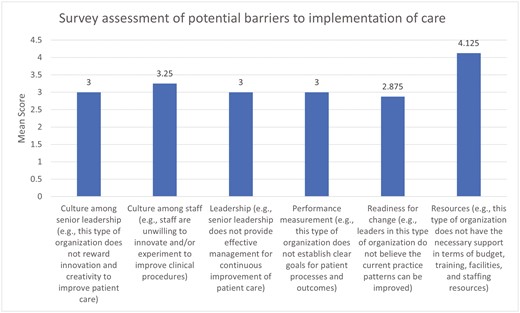

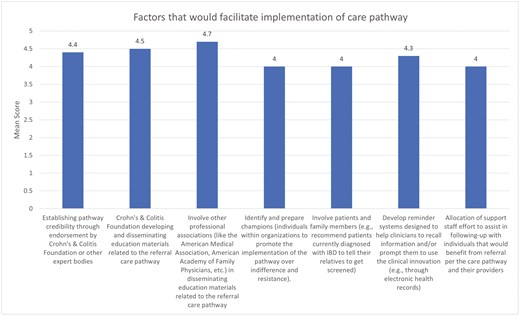

Identification of Future Barriers for Implementation of the IBD Consult Care Pathway

The panel members were also asked to identify those criteria derived from the Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment questionnaire and ERIC compilation that may present barriers to and best methods for implementation of the finalized IBD consult care pathway. The strongest perceived barriers to implementation were the availability of dedicated financial resources, training, facilities, and staffing. Other factors assessed were not perceived to be barriers implementing this consult care pathway (Figure 4). Conversely, all factors that were considered for assisting in dissemination were thought to potentially be helpful, including involving societies within and outside of GI, identifying local champions for promoting the use of these pathways, involving patients and their family members, allocating support staff to assist in patient follow-up, and designing and implementing reminder systems for implementation (Figure 5).

Results of expert elicitation regarding potential barriers to implementation of final care pathway. Expert panel members were asked to rate 6 factors on their role as potential barriers to implementation of the consult care pathway. Ratings for each barrier ranged from 1 (strongly disagree that this would be a barrier) to 5 (strongly agree this would be a barrier). Only resource-related limitations, rather than culture, leadership, performance measurement, or readiness for change, were considered to be meaningful barriers based on these survey results.

Results of expert elicitation regarding potential facilitators to implementation of final care pathway. Expert panel members were asked to rate 7 factors on their roles as potential facilitators to implementation of the consult care pathway. Ratings for each facilitator ranged from 1 (strongly disagree that this would be a facilitator) to 5 (strongly agree this would be a facilitator). All factors were considered potentially helpful in dissemination of the consult care pathway. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Discussion

Appropriately identifying patients who are at increased risk of future IBD-related adverse events and complications is imperative to improve patient care, reduce disease-related complications, and minimize healthcare utilization. In this research, we conducted a scoping literature review to identify patient-related signs, symptoms, and demographic characteristics that could indicate patients who may most benefit from a referral from a primary care physician or GI to an IBD specialist for a consultation. We then performed several rounds of elicitation using the modified RAM to derive a novel, easy-to-implement, evidence-based IBD consult care pathway, identifying primary and secondary criteria that should prompt referral of patients with IBD to IBD specialists and centers for consultations.

IBD is known to be associated with significant morbidity and healthcare utilization. Patients with IBD have been shown to accrue >3-fold increased costs in comparison with other disease states.5 The risks of adverse events, surgical intervention, healthcare utilization, and increased expenditures only increase with poor disease control, as has been demonstrated in several recent claims-based assessments.55-57 Importantly, these trends can be positively impacted through improved IBD-related care; several studies have demonstrated that earlier use of appropriate immunosuppressive and biologic therapies can reduce the risks of future stricturing disease or surgical intervention.58,59 Further, recent work within IBD Qorus,60 an initiative of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, which is a network collaborative of over 50 clinical sites focused on improving quality of care in IBD, has demonstrated that specialty centers in this network can reduce rates of healthcare utilization such as urgent care visits or hospitalization and decrease the economic burden of experiencing IBD.61,62 While these results are promising, it is important to note that data derived from cohorts such as IBD Qorus may be skewed and inherently self-selecting. It remains unclear at this time whether all IBD patients would benefit from specialized care. Identifying individuals for whom this may be required is therefore vital, as access to such resources may remain limited due to financial or geographic constraints, as well as the availability of such centers and providers.

There have been several attempts to identify appropriate triggers for referral to gastroenterology for those who may be at risk of developing IBD, as well as for identifying factors that should prompt further evaluation and assessment by a patient’s GI or referral to an IBD specialist. As previously noted, efforts such as the Red Flags Index and IBD-REFER have attempted to assist in more rapid triage of undiagnosed patients to gastroenterology for further evaluation,13-15 potentially reducing the well-described diagnostic delay that is common in IBD.6 For those who have been diagnosed, there have been multiple recent educational efforts regarding appropriate utilization of biologic and small molecule therapies, as well as more stringent monitoring of patients to maximize their benefits through treat-to-target-based algorithms of care.63-67 Such efforts have been shown in clinical trials to also improve steroid free remission, mucosal healing, and to be cost effective.68-70

There has also been an increasing effort to impart guidance to providers within and outside of gastroenterology regarding when it is appropriate to refer patients with IBD to gastroenterology as well as to other ancillary providers. The most prominent of these examples was the American Gastroenterological Association’s recent IBD Care Pathway initiative.21 Our work presented here extends these efforts using the best available evidence derived from a scoping review, combined with a panel of IBD specialists, general GIs, primary care physicians, and patient representatives to develop a novel framework of easily identifiable clinical factors for characterizing those individuals with IBD who would likely most benefit from a consult referral from their GI to an IBD specialist. This model, combining single major criteria or multiple minor criteria to guide referral, was strongly supported by the literature and our expert panel. We hope that these criteria can be used not only by gastroenterologists when considering referral to IBD specialists for consultation, but also to primary care and other providers who may care for patients with IBD. It is important to note, however, that given the limitations of the current IBD subspecialist workforce, these findings are not meant to imply that patients identified as at risk should be seen solely by an IBD subspecialist; rather, co-management with general gastroenterology and acknowledgement of their increased risk may serve to improve care.

Another major strength of our research is the additional step of identifying how best this care pathway might be implemented. Using concepts derived from the Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment questionnaire and ERIC compilation, we identified that the need for dedicated resources for implementing this consult care pathway was a key barrier that would need to be overcome.25,26 Further, we identified several factors that might assist in implementation, including support from both gastroenterology and primary care organizations. Successful dissemination would likely require the support of GI societies and organizations, such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, and American College of Gastroenterology. This latter component will require close collaboration with these national organizations.

Our work also identified the electronic medical record as a potential point of implementation. Many of the criteria identified here are stored as discrete elements within commonly used electronic medical records, which would allow for the development of provider-facing reminder systems when certain criteria or combinations thereof, as in our pathway, are met. There are numerous examples of successfully applying care pathways through the electronic medical record in other fields of medicine, including in oncology, infectious diseases, endocrinology, and primary care.71-73 Similar implementation schemes have also been shown to improve the management of anemia in pediatric patients with IBD.74 These prior efforts could serve as a critical foundation for future implementation of our findings.