-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Eleanor Liu, Robyn Laube, Rupert W Leong, Aileen Fraser, Christian Selinger, Jimmy K Limdi, Managing Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy: Health Care Professionals’ Involvement, Knowledge, and Decision Making, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 29, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 522–530, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac101

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The management of pregnant women with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is complex. We aimed to assess health care professionals’ (HCPs) theoretical and applied knowledge of pregnancy-related IBD issues.

A cross-sectional international survey was distributed to HCPs providing IBD care between October 2020 and March 2021. Knowledge was assessed using the validated Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge Score (CCPKnow; range, 0-17). Decision-making was assessed by free text responses to 3 clinical scenarios scored against predetermined scoring criteria (maximum score 70).

Among 81 participants, median CCPKnow score was 16 (range, 8-17), and median total scenario score was 29 (range, 9-51). Health care professionals who treat >10 IBD patients per week (CCPKnow P = .03; scenarios P = .003) and are more regularly involved in pregnancy care (CCPKnow P = .005; scenarios P = .005) had significantly better scores. Although CCPKnow scoring was consistently high (median score ≥15) across all groups, consultants scored better than trainees and IBD nurses (P = .008 and P = .031). Median scenario scores were higher for consultants (32) and IBD nurses (33) compared with trainees (24; P = .018 and P = .022). There was a significant positive correlation between caring for greater numbers of pregnant IBD patients and higher CCPKnow (P = .001, r = .358) and scenario scores (P = .001, r = .377). There was a modest correlation between CCPKnow and scenario scores (r = .356; P < 0.001).

Despite “good” theoretical pregnancy-related IBD knowledge as assessed by CCPKnow, applied knowledge in the scenarios was less consistent. There is need for further HCP education and clinical experience to achieve optimal standardized care for IBD in pregnancy.

Lay Summary

Objective assessment of pregnancy-specific IBD knowledge among gastroenterology health care professionals is good; however, clinician application of knowledge in decision-making is less consistent. There is need for further clinician education to provide optimal standardized care for IBD in pregnancy.

What is already known?

Previous studies have demonstrated the benefit of health care professional–delivered education in improving patient knowledge in IBD.

What is new here?

Despite very good theoretical health care professional pregnancy-related IBD knowledge, clinician application of knowledge is less consistent, which demonstrates a need for further education.

How can this study help patient care?

Managing IBD in pregnancy should be addressed in educational initiatives to enable clinicians to counsel and manage this complex patient group appropriately, ensuring optimal standardized care for IBD in pregnancy.

Introduction

The peak incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is between the second and fourth decades of life, coinciding with a woman’s reproductive years.1 Inflammatory bowel disease activity during pregnancy is a key determinant of the course of IBD during pregnancy.2–5 Active IBD is associated with adverse pregnancy-related outcomes, such as miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, and preterm birth.5–7 Management of pregnant women with IBD therefore requires health care professionals (HCPs) and women with IBD to have an astute understanding of IBD management during the reproductive period in order to achieve optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.

In recent years, there has been evolving evidence in this area, and several international guidelines have been published.2,8–10 Patient knowledge on reproductive issues in IBD meanwhile remains suboptimal, with frequent patient misconceptions regarding fertility and pregnancy in IBD.11–14 Suboptimal knowledge and uninformed patient decision-making contributes to medication discontinuation, which increases the risk of IBD flares and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Poor pregnancy-related knowledge is also associated with voluntary childlessness,15,16 which has been documented in 18% of women with IBD compared with 6% of healthy women.17

Previous studies have demonstrated the positive impact of HCP-delivered education on improving patient knowledge,13 pregnancy rates, and reducing voluntary childlessness,14 and improving quality of life and mental health.18–20 However, HCP-delivered education is reliant on HCPs themselves possessing adequate knowledge. Pregnancy-specific IBD knowledge among HCPs has been shown to vary among specialties (gastroenterologists, general practitioners, and obstetricians), and inadequate HCP knowledge could result in inappropriate advice.21,22 An Australian study identified consistently high pregnancy-specific IBD knowledge scores among gastroenterologists with no identifiable predictors of knowledge, likely due to a “ceiling” effect.21

We performed an international survey to evaluate HCPs’ knowledge of IBD-related issues in pregnancy. The aim of this study was to assess HCPs’ applied knowledge of pregnancy-related IBD issues (using clinical scenario-based assessments) and assess for correlation with HCPs’ theoretical knowledge (as measured by CCPKnow).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

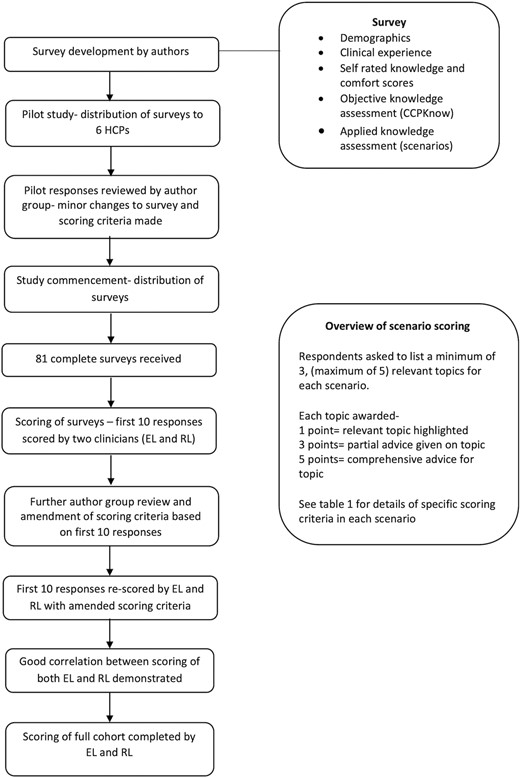

This was a cross-sectional, multicenter, international survey of gastroenterology HCPs involved in IBD care. Figure 1 outlines the methodology of the survey development and scoring. Participants included IBD specialists and general and non-IBD specialist gastroenterologists. A pilot survey was initially distributed to 2 gastroenterology consultants, 2 gastroenterology higher specialist trainees (fellows), and 2 IBD clinical nurse specialists (CNS) at a UK district general hospital. Following this pilot, minor modifications were made to the survey prior to study commencement.

The questionnaire collected demographic information including professional background, level of training (consultant, higher specialist trainee/registrar/fellow, IBD CNS), number of years in practice, and current place of work (teaching hospital/tertiary center, district/general hospital, and/or private practice). Other questions pertained to their frequency of managing pregnant and nonpregnant IBD patients, and their self-rated knowledge and competency in managing these patients.

Objective Knowledge Assessment

Pregnancy-specific knowledge was objectively assessed using the Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge score (CCPKnow; appendix 1).12 This 17-item questionnaire has been validated to assess pregnancy-specific knowledge in patients, and knowledge is classed as poor (0-7), adequate (8-10), good (11-13), and very good (14-17). The topics covered in CCPKnow include inheritance of IBD, fertility, disease activity at conception and during pregnancy, medications during pregnancy, pregnancy outcomes, delivery mode, and breastfeeding.12 Self-rated knowledge was graded using a 10-point Likert scale from “no knowledge” to “expert.” Self-rated comfort in managing pregnant IBD patients was graded using a 10-point Likert scale from “very uncomfortable” to “very comfortable.”

Applied Knowledge Assessment

Decision-making was assessed by free text responses to 3 clinical scenarios (Table 1) developed by experienced senior investigators and expert IBD clinicians (J.K.L., C.S., R.W.L., A.F.). The scenarios were developed following group discussion and agreement on key concepts to be addressed in the scenario assessments based on current international guidelines.8,23 Participants were required to list and comment on a minimum of 3 (but up to 5) medical topics they considered relevant to each scenario. Ideal answers and suggested scoring criteria were developed based on current IBD and obstetric guidelines,2,8,24 and participant responses were scored against the predetermined scoring criteria. One point was awarded for highlighting a relevant topic only, 3 points for partial advice given on the topic, and 5 points for comprehensive advice given for the topic mentioned. The overall maximum attainable score was 70 (although for the mandated 3 topics only, maximum score was 45). Scenarios were scored by 2 clinicians (E.L. and R.L.). The first 30 scenarios (10 responses of each scenario) were scored by both clinicians, and common themes were identified in the responses. After a group meeting between investigators to review the scoring criteria based on the pilot responses, minor changes were made to the criteria. For example, pre-eclampsia and venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk were identified as topics very few HCPs mentioned in the pilot responses. The group agreed that although awareness of pre-eclampsia is more of an obstetric consideration, gastroenterologists managing pregnant IBD patients should still be aware of this complication,10,23 and therefore the score awarded to “pre-eclampsia” was downgraded from 3 points to 1 point. Conversely, the group agreed that VTE risk was a pertinent topic, and the scoring criteria remained unchanged for VTE risk despite few HCPs in the pilot acknowledging VTE risk. After a consensus, the first 30 scenarios were then rescored by R.L. and E.L. with the amended criteria. Good correlation between the scores of both clinicians was demonstrated prior to subsequent scoring of the full cohort.

| . | Topic 1 . | Topic 2 . | Topic 3 . | Topic 4 . | Topic 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 (Maximum score 25) Diana is a 26 year old woman with a 10 year history of ileocolonic and perianal CD. She has been on Infliximab monotherapy for 3 years and has good trough levels with no anti-drug antibodies. Her last examination under anaesthesia was 2 years ago when an abscess was treated. A seton remains in situ. She is now 22 weeks pregnant and reports feeling well. There is no abdominal pain, she opens her bowels twice daily and reports no pain or discharge from her perineum. She is already under a consultant led obstetric clinic. | Anti TNF use in 3rdtrimester pregnancy • Drug treatment (1) • Infliximab low risk, discuss 3rd trimester plan (3) • Clear advice to continue/stop Infliximab in 3rd trimester (5) | Delivery considerations in perianal CD • Delivery mentioned (1) • Advice specifically on mode of delivery (3) • Advises caesarean birth mandatory in this scenario (5) | Neonatal vaccinations with biologic use • Childhood vaccinations (1) • Advises avoid or delay live vaccinations (3) • Avoid or delay live vaccinations; specifically mentions rotavirus and/or BCG vaccination (5) | Breastfeeding considerations • Breastfeeding (1) • Breastfeeding safe while on Infliximab (3) • Breastfeeding safe and offers advantages over bottle feeding (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Growth scanning • VTE prophylaxis • IBD advice line • Risk of postpartum flare • Early postpartum follow-up • Infliximab plan postpartum • Inheritance of IBD |

| Scenario 2 (Maximum score 20) Abby is a 35-year old woman who is 28 weeks into her first pregnancy. Abby has a family history of type 2 diabetes, a BMI of 35 and a background of left sided UC that was previously well controlled. She has been flaring for 4 weeks with a FC > 1000. On advice by the advice line she has increased her mesalazine from 2.4g OD to 2.4g BD and added in mesalazine 2g liquid enemas. This has not improved her symptoms much. She opens her bowel 6/day (normal for her 2/day) and sees blood with every 2nd motion. She has no tachycardia or fever. You have commenced her on Prednisolone 40mg reducing over 8 weeks. She is under the care of a community midwife. | Considerations when managing UC flare during pregnancy • IBD treatment and observation (1) • Ensure she contacts IBD services if not improving (3) • Arrange close follow-up to ensure quick clinical improvement (5) | Obstetric considerations (maximum 5 points if all mentioned) • Needs obstetric clinic/ obstetric led care (1) • Risk of pre-eclampsia (1) • Growth scan required (3) • Risk of gestational diabetes (3) | VTE risk • VTE risk mentioned (1) • Discuss VTE risk with obstetrician (3) • Needs VTE prophylaxis as several risk factors (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Further pregnancy care • Advice on drug safety and importance • Can have vaginal delivery obstetric course permitting • Breastfeeding advice • Risk of postpartum flare • Vaccination advice | |

| Scenario 3 (Maximum score 25) Samantha is a 28 year old woman with ileo-colonic CD. She has required 2 resections including a panproctocolectomy and a further ileal resection. She has an ileostomy at present and her last imaging 6 months ago showed 20 cms of ileal inflammation leading up to the stoma. She started adalimumab 40mg 6 months ago and feels well. She reports stopping her adalimumab after she found she is pregnant 3 weeks ago. She is seen in IBD clinic by yourself and has yet to see obstetric services. She believes she is 15 weeks pregnant. Samantha says she will only consider a caesarean birth. | Risk of active disease during pregnancy, optimizing disease control • Importance of remission and drug therapy (1) • Advises adalimumab low risk in pregnancy (3) • Advises patient is high risk for active symptoms due to known active CD and risk of CD > risk from adalimumab, advises strongly to continue, assess disease activity eg. FC (5) | Anti TNF use during pregnancy • Management of adalimumab (1) • Advises on whether to stop or continue (3) • Vaccination advice, and clear advice to continue adalimumab (5) | Obstetric considerations in active IBD • Refer for obstetric care (1) • Needs “delayed” 12 week scan and obstetric clinic asap (3) [does not need to specifically state’12 week scan’ as long as they recognize pregnancy is high risk] Needs 3rd trimester growth scans (5) | Delivery considerations in non-perianal CD • Mode of delivery discussion (1) • Recognizes that CD intervention is not indication for caesarean birth (3) • Discuss benefits and risks of caesarean in patients, with suggestion towards vaginal delivery (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to 5 if good rationale) • Breastfeeding advice • VTE advice • When to start adalimumab after delivery (assuming it was stopped) • Stoma issues including change of shape, how to deal with potential stoma problems (obstruction, prolapse) • Nutritional considerations |

| . | Topic 1 . | Topic 2 . | Topic 3 . | Topic 4 . | Topic 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 (Maximum score 25) Diana is a 26 year old woman with a 10 year history of ileocolonic and perianal CD. She has been on Infliximab monotherapy for 3 years and has good trough levels with no anti-drug antibodies. Her last examination under anaesthesia was 2 years ago when an abscess was treated. A seton remains in situ. She is now 22 weeks pregnant and reports feeling well. There is no abdominal pain, she opens her bowels twice daily and reports no pain or discharge from her perineum. She is already under a consultant led obstetric clinic. | Anti TNF use in 3rdtrimester pregnancy • Drug treatment (1) • Infliximab low risk, discuss 3rd trimester plan (3) • Clear advice to continue/stop Infliximab in 3rd trimester (5) | Delivery considerations in perianal CD • Delivery mentioned (1) • Advice specifically on mode of delivery (3) • Advises caesarean birth mandatory in this scenario (5) | Neonatal vaccinations with biologic use • Childhood vaccinations (1) • Advises avoid or delay live vaccinations (3) • Avoid or delay live vaccinations; specifically mentions rotavirus and/or BCG vaccination (5) | Breastfeeding considerations • Breastfeeding (1) • Breastfeeding safe while on Infliximab (3) • Breastfeeding safe and offers advantages over bottle feeding (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Growth scanning • VTE prophylaxis • IBD advice line • Risk of postpartum flare • Early postpartum follow-up • Infliximab plan postpartum • Inheritance of IBD |

| Scenario 2 (Maximum score 20) Abby is a 35-year old woman who is 28 weeks into her first pregnancy. Abby has a family history of type 2 diabetes, a BMI of 35 and a background of left sided UC that was previously well controlled. She has been flaring for 4 weeks with a FC > 1000. On advice by the advice line she has increased her mesalazine from 2.4g OD to 2.4g BD and added in mesalazine 2g liquid enemas. This has not improved her symptoms much. She opens her bowel 6/day (normal for her 2/day) and sees blood with every 2nd motion. She has no tachycardia or fever. You have commenced her on Prednisolone 40mg reducing over 8 weeks. She is under the care of a community midwife. | Considerations when managing UC flare during pregnancy • IBD treatment and observation (1) • Ensure she contacts IBD services if not improving (3) • Arrange close follow-up to ensure quick clinical improvement (5) | Obstetric considerations (maximum 5 points if all mentioned) • Needs obstetric clinic/ obstetric led care (1) • Risk of pre-eclampsia (1) • Growth scan required (3) • Risk of gestational diabetes (3) | VTE risk • VTE risk mentioned (1) • Discuss VTE risk with obstetrician (3) • Needs VTE prophylaxis as several risk factors (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Further pregnancy care • Advice on drug safety and importance • Can have vaginal delivery obstetric course permitting • Breastfeeding advice • Risk of postpartum flare • Vaccination advice | |

| Scenario 3 (Maximum score 25) Samantha is a 28 year old woman with ileo-colonic CD. She has required 2 resections including a panproctocolectomy and a further ileal resection. She has an ileostomy at present and her last imaging 6 months ago showed 20 cms of ileal inflammation leading up to the stoma. She started adalimumab 40mg 6 months ago and feels well. She reports stopping her adalimumab after she found she is pregnant 3 weeks ago. She is seen in IBD clinic by yourself and has yet to see obstetric services. She believes she is 15 weeks pregnant. Samantha says she will only consider a caesarean birth. | Risk of active disease during pregnancy, optimizing disease control • Importance of remission and drug therapy (1) • Advises adalimumab low risk in pregnancy (3) • Advises patient is high risk for active symptoms due to known active CD and risk of CD > risk from adalimumab, advises strongly to continue, assess disease activity eg. FC (5) | Anti TNF use during pregnancy • Management of adalimumab (1) • Advises on whether to stop or continue (3) • Vaccination advice, and clear advice to continue adalimumab (5) | Obstetric considerations in active IBD • Refer for obstetric care (1) • Needs “delayed” 12 week scan and obstetric clinic asap (3) [does not need to specifically state’12 week scan’ as long as they recognize pregnancy is high risk] Needs 3rd trimester growth scans (5) | Delivery considerations in non-perianal CD • Mode of delivery discussion (1) • Recognizes that CD intervention is not indication for caesarean birth (3) • Discuss benefits and risks of caesarean in patients, with suggestion towards vaginal delivery (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to 5 if good rationale) • Breastfeeding advice • VTE advice • When to start adalimumab after delivery (assuming it was stopped) • Stoma issues including change of shape, how to deal with potential stoma problems (obstruction, prolapse) • Nutritional considerations |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn’s disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VTE, venous thromboembolism; BMI, body mass index; UC, ulcerative colitis; FC, fecal calprotectin; OD, once daily; BD, twice daily.

Number of points awarded in parentheses after each topic and criteria listed.

| . | Topic 1 . | Topic 2 . | Topic 3 . | Topic 4 . | Topic 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 (Maximum score 25) Diana is a 26 year old woman with a 10 year history of ileocolonic and perianal CD. She has been on Infliximab monotherapy for 3 years and has good trough levels with no anti-drug antibodies. Her last examination under anaesthesia was 2 years ago when an abscess was treated. A seton remains in situ. She is now 22 weeks pregnant and reports feeling well. There is no abdominal pain, she opens her bowels twice daily and reports no pain or discharge from her perineum. She is already under a consultant led obstetric clinic. | Anti TNF use in 3rdtrimester pregnancy • Drug treatment (1) • Infliximab low risk, discuss 3rd trimester plan (3) • Clear advice to continue/stop Infliximab in 3rd trimester (5) | Delivery considerations in perianal CD • Delivery mentioned (1) • Advice specifically on mode of delivery (3) • Advises caesarean birth mandatory in this scenario (5) | Neonatal vaccinations with biologic use • Childhood vaccinations (1) • Advises avoid or delay live vaccinations (3) • Avoid or delay live vaccinations; specifically mentions rotavirus and/or BCG vaccination (5) | Breastfeeding considerations • Breastfeeding (1) • Breastfeeding safe while on Infliximab (3) • Breastfeeding safe and offers advantages over bottle feeding (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Growth scanning • VTE prophylaxis • IBD advice line • Risk of postpartum flare • Early postpartum follow-up • Infliximab plan postpartum • Inheritance of IBD |

| Scenario 2 (Maximum score 20) Abby is a 35-year old woman who is 28 weeks into her first pregnancy. Abby has a family history of type 2 diabetes, a BMI of 35 and a background of left sided UC that was previously well controlled. She has been flaring for 4 weeks with a FC > 1000. On advice by the advice line she has increased her mesalazine from 2.4g OD to 2.4g BD and added in mesalazine 2g liquid enemas. This has not improved her symptoms much. She opens her bowel 6/day (normal for her 2/day) and sees blood with every 2nd motion. She has no tachycardia or fever. You have commenced her on Prednisolone 40mg reducing over 8 weeks. She is under the care of a community midwife. | Considerations when managing UC flare during pregnancy • IBD treatment and observation (1) • Ensure she contacts IBD services if not improving (3) • Arrange close follow-up to ensure quick clinical improvement (5) | Obstetric considerations (maximum 5 points if all mentioned) • Needs obstetric clinic/ obstetric led care (1) • Risk of pre-eclampsia (1) • Growth scan required (3) • Risk of gestational diabetes (3) | VTE risk • VTE risk mentioned (1) • Discuss VTE risk with obstetrician (3) • Needs VTE prophylaxis as several risk factors (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Further pregnancy care • Advice on drug safety and importance • Can have vaginal delivery obstetric course permitting • Breastfeeding advice • Risk of postpartum flare • Vaccination advice | |

| Scenario 3 (Maximum score 25) Samantha is a 28 year old woman with ileo-colonic CD. She has required 2 resections including a panproctocolectomy and a further ileal resection. She has an ileostomy at present and her last imaging 6 months ago showed 20 cms of ileal inflammation leading up to the stoma. She started adalimumab 40mg 6 months ago and feels well. She reports stopping her adalimumab after she found she is pregnant 3 weeks ago. She is seen in IBD clinic by yourself and has yet to see obstetric services. She believes she is 15 weeks pregnant. Samantha says she will only consider a caesarean birth. | Risk of active disease during pregnancy, optimizing disease control • Importance of remission and drug therapy (1) • Advises adalimumab low risk in pregnancy (3) • Advises patient is high risk for active symptoms due to known active CD and risk of CD > risk from adalimumab, advises strongly to continue, assess disease activity eg. FC (5) | Anti TNF use during pregnancy • Management of adalimumab (1) • Advises on whether to stop or continue (3) • Vaccination advice, and clear advice to continue adalimumab (5) | Obstetric considerations in active IBD • Refer for obstetric care (1) • Needs “delayed” 12 week scan and obstetric clinic asap (3) [does not need to specifically state’12 week scan’ as long as they recognize pregnancy is high risk] Needs 3rd trimester growth scans (5) | Delivery considerations in non-perianal CD • Mode of delivery discussion (1) • Recognizes that CD intervention is not indication for caesarean birth (3) • Discuss benefits and risks of caesarean in patients, with suggestion towards vaginal delivery (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to 5 if good rationale) • Breastfeeding advice • VTE advice • When to start adalimumab after delivery (assuming it was stopped) • Stoma issues including change of shape, how to deal with potential stoma problems (obstruction, prolapse) • Nutritional considerations |

| . | Topic 1 . | Topic 2 . | Topic 3 . | Topic 4 . | Topic 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 (Maximum score 25) Diana is a 26 year old woman with a 10 year history of ileocolonic and perianal CD. She has been on Infliximab monotherapy for 3 years and has good trough levels with no anti-drug antibodies. Her last examination under anaesthesia was 2 years ago when an abscess was treated. A seton remains in situ. She is now 22 weeks pregnant and reports feeling well. There is no abdominal pain, she opens her bowels twice daily and reports no pain or discharge from her perineum. She is already under a consultant led obstetric clinic. | Anti TNF use in 3rdtrimester pregnancy • Drug treatment (1) • Infliximab low risk, discuss 3rd trimester plan (3) • Clear advice to continue/stop Infliximab in 3rd trimester (5) | Delivery considerations in perianal CD • Delivery mentioned (1) • Advice specifically on mode of delivery (3) • Advises caesarean birth mandatory in this scenario (5) | Neonatal vaccinations with biologic use • Childhood vaccinations (1) • Advises avoid or delay live vaccinations (3) • Avoid or delay live vaccinations; specifically mentions rotavirus and/or BCG vaccination (5) | Breastfeeding considerations • Breastfeeding (1) • Breastfeeding safe while on Infliximab (3) • Breastfeeding safe and offers advantages over bottle feeding (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Growth scanning • VTE prophylaxis • IBD advice line • Risk of postpartum flare • Early postpartum follow-up • Infliximab plan postpartum • Inheritance of IBD |

| Scenario 2 (Maximum score 20) Abby is a 35-year old woman who is 28 weeks into her first pregnancy. Abby has a family history of type 2 diabetes, a BMI of 35 and a background of left sided UC that was previously well controlled. She has been flaring for 4 weeks with a FC > 1000. On advice by the advice line she has increased her mesalazine from 2.4g OD to 2.4g BD and added in mesalazine 2g liquid enemas. This has not improved her symptoms much. She opens her bowel 6/day (normal for her 2/day) and sees blood with every 2nd motion. She has no tachycardia or fever. You have commenced her on Prednisolone 40mg reducing over 8 weeks. She is under the care of a community midwife. | Considerations when managing UC flare during pregnancy • IBD treatment and observation (1) • Ensure she contacts IBD services if not improving (3) • Arrange close follow-up to ensure quick clinical improvement (5) | Obstetric considerations (maximum 5 points if all mentioned) • Needs obstetric clinic/ obstetric led care (1) • Risk of pre-eclampsia (1) • Growth scan required (3) • Risk of gestational diabetes (3) | VTE risk • VTE risk mentioned (1) • Discuss VTE risk with obstetrician (3) • Needs VTE prophylaxis as several risk factors (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to maximum 5 points if good rationale) • Further pregnancy care • Advice on drug safety and importance • Can have vaginal delivery obstetric course permitting • Breastfeeding advice • Risk of postpartum flare • Vaccination advice | |

| Scenario 3 (Maximum score 25) Samantha is a 28 year old woman with ileo-colonic CD. She has required 2 resections including a panproctocolectomy and a further ileal resection. She has an ileostomy at present and her last imaging 6 months ago showed 20 cms of ileal inflammation leading up to the stoma. She started adalimumab 40mg 6 months ago and feels well. She reports stopping her adalimumab after she found she is pregnant 3 weeks ago. She is seen in IBD clinic by yourself and has yet to see obstetric services. She believes she is 15 weeks pregnant. Samantha says she will only consider a caesarean birth. | Risk of active disease during pregnancy, optimizing disease control • Importance of remission and drug therapy (1) • Advises adalimumab low risk in pregnancy (3) • Advises patient is high risk for active symptoms due to known active CD and risk of CD > risk from adalimumab, advises strongly to continue, assess disease activity eg. FC (5) | Anti TNF use during pregnancy • Management of adalimumab (1) • Advises on whether to stop or continue (3) • Vaccination advice, and clear advice to continue adalimumab (5) | Obstetric considerations in active IBD • Refer for obstetric care (1) • Needs “delayed” 12 week scan and obstetric clinic asap (3) [does not need to specifically state’12 week scan’ as long as they recognize pregnancy is high risk] Needs 3rd trimester growth scans (5) | Delivery considerations in non-perianal CD • Mode of delivery discussion (1) • Recognizes that CD intervention is not indication for caesarean birth (3) • Discuss benefits and risks of caesarean in patients, with suggestion towards vaginal delivery (5) | Other considerations (1 point each, up to 5 if good rationale) • Breastfeeding advice • VTE advice • When to start adalimumab after delivery (assuming it was stopped) • Stoma issues including change of shape, how to deal with potential stoma problems (obstruction, prolapse) • Nutritional considerations |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn’s disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VTE, venous thromboembolism; BMI, body mass index; UC, ulcerative colitis; FC, fecal calprotectin; OD, once daily; BD, twice daily.

Number of points awarded in parentheses after each topic and criteria listed.

Eligible participants from UK and Australia were invited between October 2020 and March 2021 via email and text message to complete the web-based questionnaire using an online survey tool (Smart Survey UK). Invitations with the web link were sent to regional gastroenterologists and IBD clinical nurse specialists who then shared the link with their teams. Invitations were also sent to specialist trainee networks. Completion of the questionnaire was taken as consent, and all responses were collected anonymously.

Statistical Considerations

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The CCPKnow, scenario, self-rated knowledge, and comfort scores were analyzed as continuous variables; and analyzed against categorical variables using the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Results were expressed as median scores with interquartile ranges and mean scores with standard deviations. Spearman correlation was used for nonparametric continuous data; P values <0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 26.0 for Windows.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Macquarie University Ethics Committee (reference number 52020670919116). This ethics application incorporated all international sites involved in the project.

Results

Complete surveys were received from 81 participants (response rate 20.3%), 59.2% from the UK and 40.7% from Australia (Table 2). Of these, 67% worked in a teaching hospital, 28% in a district general hospital, and 10% in private practice. One-third of HCPs (n = 27, 33.3%) were consultant gastroenterologists, one-third (n = 26, 32.1%) were IBD nurse specialists, 27.2% (n = 22) were in higher specialist training (registrars/fellows in gastroenterology), and the remaining 6 participants (7.4%) comprised other HCP roles (nonclinical fellows, pharmacists, non-CNS nurses); this latter group were excluded from most statistical analyses. Sixteen HCPs (19.8%) had >10 years of clinical experience following gastroenterology specialist qualification/certification, accreditation or appointment to IBD CNS role, and 32 (40%) were newly qualified <1 year or still in training.

| . | n . | CCPKnow Score (median) . | Scenario Score (median) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants . | n = 81 . | . | . |

| Job role | |||

| Gastroenterology consultant | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 32 |

| Gastroenterology specialty registrar/ higher specialist trainee | 22 (27.2%) | 15 | 24 |

| IBD nurse specialist (CNS/ANP/non-medical consultant) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 33 |

| Gastroenterology other (Associate specialist/ clinical or research fellow/ staff grade) | 3 (3.7%) | 16 | 26 |

| Other (pharmacist, liver fellow, non-CNS nurse) | 3 (3.7%) | 11 | 23 |

| Country | |||

| UK | 48 (59.2%) | 15 | 28 |

| Australia | 33 (40.7%) | 16 | 32 |

| Place of work | |||

| District general hospital | 23 (28.0%) | 15 | 29 |

| Teaching hospital | 54 (67.0%) | 16 | 28 |

| Private rooms/ own offices | 8 (9.9%) | 17 | 35 |

| Years (post gastroenterology certification) in practice | |||

| 0 (still in training) | 23 (28.4%) | 15 | 25 |

| <1 year | 9 (11.1%) | 14 | 23 |

| 1-4 years | 20 (24.7%) | 16 | 33 |

| 5-9 years | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 35 |

| 10-19 years | 11 (13.5%) | 17 | 32 |

| >20 years | 5 (6.2%) | 16 | 33 |

| Number IBD patients reviewed per week | |||

| 0–5 per week | 19 (23.5%) | 15 | 26 |

| 6–10 per week | 17 (21.0%) | 15 | 25 |

| 11–15 per week | 11 (13.6%) | 16 | 41 |

| 16–20 per week | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 33 |

| >20 per week | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 32 |

| Frequency of care for pregnant women with IBD | |||

| Never | 7 (8.6%) | 12 | 17 |

| Very few cases (<5 total) | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 26 |

| Occasionally (≤3 per year) | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 29 |

| Regularly (>3 year) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 35 |

| Availability of specialized IBD pregnancy team | |||

| Available and respondent part of team | 15 (18.5%) | 16 | 35 |

| Available, but respondent not part of team | 19 (23.5%) | 17 | 29 |

| Not available | 47 (58.0%) | 16 | 29 |

| . | n . | CCPKnow Score (median) . | Scenario Score (median) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants . | n = 81 . | . | . |

| Job role | |||

| Gastroenterology consultant | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 32 |

| Gastroenterology specialty registrar/ higher specialist trainee | 22 (27.2%) | 15 | 24 |

| IBD nurse specialist (CNS/ANP/non-medical consultant) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 33 |

| Gastroenterology other (Associate specialist/ clinical or research fellow/ staff grade) | 3 (3.7%) | 16 | 26 |

| Other (pharmacist, liver fellow, non-CNS nurse) | 3 (3.7%) | 11 | 23 |

| Country | |||

| UK | 48 (59.2%) | 15 | 28 |

| Australia | 33 (40.7%) | 16 | 32 |

| Place of work | |||

| District general hospital | 23 (28.0%) | 15 | 29 |

| Teaching hospital | 54 (67.0%) | 16 | 28 |

| Private rooms/ own offices | 8 (9.9%) | 17 | 35 |

| Years (post gastroenterology certification) in practice | |||

| 0 (still in training) | 23 (28.4%) | 15 | 25 |

| <1 year | 9 (11.1%) | 14 | 23 |

| 1-4 years | 20 (24.7%) | 16 | 33 |

| 5-9 years | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 35 |

| 10-19 years | 11 (13.5%) | 17 | 32 |

| >20 years | 5 (6.2%) | 16 | 33 |

| Number IBD patients reviewed per week | |||

| 0–5 per week | 19 (23.5%) | 15 | 26 |

| 6–10 per week | 17 (21.0%) | 15 | 25 |

| 11–15 per week | 11 (13.6%) | 16 | 41 |

| 16–20 per week | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 33 |

| >20 per week | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 32 |

| Frequency of care for pregnant women with IBD | |||

| Never | 7 (8.6%) | 12 | 17 |

| Very few cases (<5 total) | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 26 |

| Occasionally (≤3 per year) | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 29 |

| Regularly (>3 year) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 35 |

| Availability of specialized IBD pregnancy team | |||

| Available and respondent part of team | 15 (18.5%) | 16 | 35 |

| Available, but respondent not part of team | 19 (23.5%) | 17 | 29 |

| Not available | 47 (58.0%) | 16 | 29 |

Abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CNS, clinical nurse specialist; ANP, advanced nurse practitioner; UK, United Kingdom.

| . | n . | CCPKnow Score (median) . | Scenario Score (median) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants . | n = 81 . | . | . |

| Job role | |||

| Gastroenterology consultant | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 32 |

| Gastroenterology specialty registrar/ higher specialist trainee | 22 (27.2%) | 15 | 24 |

| IBD nurse specialist (CNS/ANP/non-medical consultant) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 33 |

| Gastroenterology other (Associate specialist/ clinical or research fellow/ staff grade) | 3 (3.7%) | 16 | 26 |

| Other (pharmacist, liver fellow, non-CNS nurse) | 3 (3.7%) | 11 | 23 |

| Country | |||

| UK | 48 (59.2%) | 15 | 28 |

| Australia | 33 (40.7%) | 16 | 32 |

| Place of work | |||

| District general hospital | 23 (28.0%) | 15 | 29 |

| Teaching hospital | 54 (67.0%) | 16 | 28 |

| Private rooms/ own offices | 8 (9.9%) | 17 | 35 |

| Years (post gastroenterology certification) in practice | |||

| 0 (still in training) | 23 (28.4%) | 15 | 25 |

| <1 year | 9 (11.1%) | 14 | 23 |

| 1-4 years | 20 (24.7%) | 16 | 33 |

| 5-9 years | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 35 |

| 10-19 years | 11 (13.5%) | 17 | 32 |

| >20 years | 5 (6.2%) | 16 | 33 |

| Number IBD patients reviewed per week | |||

| 0–5 per week | 19 (23.5%) | 15 | 26 |

| 6–10 per week | 17 (21.0%) | 15 | 25 |

| 11–15 per week | 11 (13.6%) | 16 | 41 |

| 16–20 per week | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 33 |

| >20 per week | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 32 |

| Frequency of care for pregnant women with IBD | |||

| Never | 7 (8.6%) | 12 | 17 |

| Very few cases (<5 total) | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 26 |

| Occasionally (≤3 per year) | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 29 |

| Regularly (>3 year) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 35 |

| Availability of specialized IBD pregnancy team | |||

| Available and respondent part of team | 15 (18.5%) | 16 | 35 |

| Available, but respondent not part of team | 19 (23.5%) | 17 | 29 |

| Not available | 47 (58.0%) | 16 | 29 |

| . | n . | CCPKnow Score (median) . | Scenario Score (median) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants . | n = 81 . | . | . |

| Job role | |||

| Gastroenterology consultant | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 32 |

| Gastroenterology specialty registrar/ higher specialist trainee | 22 (27.2%) | 15 | 24 |

| IBD nurse specialist (CNS/ANP/non-medical consultant) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 33 |

| Gastroenterology other (Associate specialist/ clinical or research fellow/ staff grade) | 3 (3.7%) | 16 | 26 |

| Other (pharmacist, liver fellow, non-CNS nurse) | 3 (3.7%) | 11 | 23 |

| Country | |||

| UK | 48 (59.2%) | 15 | 28 |

| Australia | 33 (40.7%) | 16 | 32 |

| Place of work | |||

| District general hospital | 23 (28.0%) | 15 | 29 |

| Teaching hospital | 54 (67.0%) | 16 | 28 |

| Private rooms/ own offices | 8 (9.9%) | 17 | 35 |

| Years (post gastroenterology certification) in practice | |||

| 0 (still in training) | 23 (28.4%) | 15 | 25 |

| <1 year | 9 (11.1%) | 14 | 23 |

| 1-4 years | 20 (24.7%) | 16 | 33 |

| 5-9 years | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 35 |

| 10-19 years | 11 (13.5%) | 17 | 32 |

| >20 years | 5 (6.2%) | 16 | 33 |

| Number IBD patients reviewed per week | |||

| 0–5 per week | 19 (23.5%) | 15 | 26 |

| 6–10 per week | 17 (21.0%) | 15 | 25 |

| 11–15 per week | 11 (13.6%) | 16 | 41 |

| 16–20 per week | 13 (16.0%) | 16 | 33 |

| >20 per week | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 32 |

| Frequency of care for pregnant women with IBD | |||

| Never | 7 (8.6%) | 12 | 17 |

| Very few cases (<5 total) | 27 (33.3%) | 16 | 26 |

| Occasionally (≤3 per year) | 21 (25.9%) | 16 | 29 |

| Regularly (>3 year) | 26 (32.1%) | 16 | 35 |

| Availability of specialized IBD pregnancy team | |||

| Available and respondent part of team | 15 (18.5%) | 16 | 35 |

| Available, but respondent not part of team | 19 (23.5%) | 17 | 29 |

| Not available | 47 (58.0%) | 16 | 29 |

Abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CNS, clinical nurse specialist; ANP, advanced nurse practitioner; UK, United Kingdom.

There was an even spread of HCP’s level of involvement in managing IBD patients, and only 7 (8.6%) had no experience in caring for pregnant women with IBD (5 gastroenterology higher specialist trainees, 1 newly qualified IBD CNS, and 1 non-clinical fellow). Less than a half of participants (n = 34, 42%) had access to a combined IBD-obstetric clinic, and only 18.5% (n = 15) participants were part of that team. Median self-rated knowledge and comfort scores were 5/10 (interquartile range [IQR], 4-7) and 5/10 (IQR, 4-7), respectively (Table 3). There was a strong positive correlation between self-rated knowledge and comfort score (r = .940, P < 0.001).

| Score . | Median (IQR) . | Mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| CCPKnow (0–17) | 16.0 (14.5–17.0) | 15.2 (2.1) |

| Scenarios (0–70) | 29.0 (22.5–37.0) | 29.7 (10.4) |

| Scenario 1 (0–25) | 11.0 (8.0–15.0) | 11.4 (5.0) |

| Scenario 2 (0–20) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | 8.2 (3.3) |

| Scenario 3 (0–25) | 10.0 (6.5–14.0) | 10.2 (4.6) |

| Self-rated knowledge (0–10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.1) |

| Self-rated comfort score (0-10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.3) |

| Score . | Median (IQR) . | Mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| CCPKnow (0–17) | 16.0 (14.5–17.0) | 15.2 (2.1) |

| Scenarios (0–70) | 29.0 (22.5–37.0) | 29.7 (10.4) |

| Scenario 1 (0–25) | 11.0 (8.0–15.0) | 11.4 (5.0) |

| Scenario 2 (0–20) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | 8.2 (3.3) |

| Scenario 3 (0–25) | 10.0 (6.5–14.0) | 10.2 (4.6) |

| Self-rated knowledge (0–10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.1) |

| Self-rated comfort score (0-10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.3) |

Abbreviations: CCPKnow, Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge score; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

| Score . | Median (IQR) . | Mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| CCPKnow (0–17) | 16.0 (14.5–17.0) | 15.2 (2.1) |

| Scenarios (0–70) | 29.0 (22.5–37.0) | 29.7 (10.4) |

| Scenario 1 (0–25) | 11.0 (8.0–15.0) | 11.4 (5.0) |

| Scenario 2 (0–20) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | 8.2 (3.3) |

| Scenario 3 (0–25) | 10.0 (6.5–14.0) | 10.2 (4.6) |

| Self-rated knowledge (0–10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.1) |

| Self-rated comfort score (0-10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.3) |

| Score . | Median (IQR) . | Mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| CCPKnow (0–17) | 16.0 (14.5–17.0) | 15.2 (2.1) |

| Scenarios (0–70) | 29.0 (22.5–37.0) | 29.7 (10.4) |

| Scenario 1 (0–25) | 11.0 (8.0–15.0) | 11.4 (5.0) |

| Scenario 2 (0–20) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | 8.2 (3.3) |

| Scenario 3 (0–25) | 10.0 (6.5–14.0) | 10.2 (4.6) |

| Self-rated knowledge (0–10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.1) |

| Self-rated comfort score (0-10) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 (2.3) |

Abbreviations: CCPKnow, Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge score; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Knowledge Assessment

Overall median CCPKnow scores were excellent at 16/17 (IQR, 14.5-17.0), with 67 respondents (82.7%) achieving a “very good” CCPKnow score, 10 (12.3%) achieving a “good” score, 4 (4.9%) achieving an “adequate” score, and no HCPs scoring below 8 (Table 4). Median CCPKnow scores were 16 for consultant gastroenterologists and IBD CNSs, and 15 for gastroenterology trainees (Kruskall-Wallis test, P = .51). Although CCPKnow scoring was consistently high (median score ≥15), only 35.8% (n = 29) of HCPs self-rated their knowledge and/or comfort scores in managing pregnant IBD patients ≥7/10.

| Knowledge Level . | CCPKnow Score . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | 0–7 | 0 |

| Adequate | 8–10 | 4 (4.9%) |

| Good | 11–13 | 10 (12.3%) |

| Very Good | ≥14 | 67 (82.7%) |

| Knowledge Level . | CCPKnow Score . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | 0–7 | 0 |

| Adequate | 8–10 | 4 (4.9%) |

| Good | 11–13 | 10 (12.3%) |

| Very Good | ≥14 | 67 (82.7%) |

Abbreviations: CCPKnow: Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge score.

| Knowledge Level . | CCPKnow Score . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | 0–7 | 0 |

| Adequate | 8–10 | 4 (4.9%) |

| Good | 11–13 | 10 (12.3%) |

| Very Good | ≥14 | 67 (82.7%) |

| Knowledge Level . | CCPKnow Score . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | 0–7 | 0 |

| Adequate | 8–10 | 4 (4.9%) |

| Good | 11–13 | 10 (12.3%) |

| Very Good | ≥14 | 67 (82.7%) |

Abbreviations: CCPKnow: Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge score.

Decision-making Assessment

Overall total median scenario score was 29 (IQR, 22.5-37.0). Median total scenario scores were 32 for consultant gastroenterologists, 33 for IBD CNS, and 24 for gastroenterology trainees (Kruskall-Wallis test, P = .99). Gastroenterology consultants and IBD CNSs together had significantly greater scenario scores (mean 32.1, IQR 9.8) compared with all other HCPs combined (mean 25.3, IQR 10.1; P = .007).

Median scenario score for HCPs “never” involved in the care of pregnant IBD patients (n = 7; 8.6%) was 17; score for those with “very little” involvement was 26 (<5 cases ever; n = 27; 33.3%); score for those with “occasional” involvement was 29 (<3 cases per year; n = 21; 25.9%). And for those regularly involved (>3 cases per year; n = 26; 32.1%), the median scenario score was 35.

Correlation Between CCPKnow and Scenario Scores

The CCPKnow significantly correlated with total scenario scores; however, the effect was moderate (r = .356; P < 0.001). When comparing individual scenarios, a stronger correlation was present between CCPKnow and scenario 1 (perianal Crohn’s disease with fistula in situ in clinical remission on infliximab; r = .332; P = .002) and scenario 3 (active ileal Crohn’s disease with previous panproctocolectomy and ileostomy in situ on adalimumab; r = .318; P = .004) than scenario 2 (BMI 35, active ulcerative colitis on prednisolone therapy, under community midwife care; r = .237; P = .033). Complete scenarios are detailed in Table 1.

Health care professionals who self-rated their pregnancy-specific IBD knowledge as poor (score 0-5) scored median of 15 and 25 points for CCPKnow and scenario assessments, respectively, and HCPs who self-rated their knowledge as good (score 6-10) scored median of 16 and 35 points. Self-rated knowledge (CCPKnow P < .001, r = .416; scenarios P = .002, r = .340) and self-rated comfort (CCPKnow P < 0.001, r = .404; scenarios P = .001, r = .374) in treating pregnant women with IBD correlated modestly with both CCPKnow and scenario scores.

Predictors of CCPKnow and Scenario Scores

Neither CCPKnow (P = .190) nor scenario scores (P = .171) were significantly different between participants from the UK and Australia. Participants working primarily at teaching hospitals had significantly greater CCPKnow scores (mean 15.5, SD 2.0) than participants working primarily at general/district hospitals (mean 14.5, SD 2.3; P = .023); however, scenario scores did not differ between work places (P = .322). Overall, analysis by HCP job role displayed a trend towards significance for CCPKnow (P = .051) but not scenario scoring (P = .099). Consultants had significantly higher CCPKnow scores (mean 16.1, SD 1.1) than gastroenterology trainees (mean 14.5, SD 2.2; P = .008) and IBD nurses (mean 15.0, SD 2.1; P = .031); whereas both consultants (P = .018) and IBD nurses (P = .022) had higher scenario scores compared with trainees. Longer career duration after professional qualification or accreditation was significantly predictive of both higher CCPKnow (P = .015) and scenario scores (P = .039).

The CCPKnow scores were similar among all HCPs regardless of number of IBD patients reviewed per week (P = .299). However, scenario scores varied between quintile groups for number of IBD patients reviewed per week, and this was statistically significant (P = .006). Seeing more than 10 IBD patients per week was associated with both higher CCPKnow scores (mean 15.6, SD 1.9 vs mean 14.6, SD 2.3; P = .030) and scenario scores (P = .003). Similarly, more frequent care of pregnant IBD patients was significantly predictive of progressively greater CCPKnow (P = .005) and scenario scores (P = .005). There was a significant positive correlation between caring for progressively greater numbers of pregnant IBD patients and higher CCPKnow (P = .001, r = .358) and scenario scores (P = .001, r = .377). Access to a dedicated IBD pregnancy clinic was not significantly predictive of either CCPKnow or scenario scores; however, access to an IBD pregnancy clinic and being a member of that team trended towards being predictive of greater scenario scores (P = .054), but not CCPKnow scores (P = .309).

Topics With Poorly Applied Knowledge

In scenario 1, 55 of 81 (68%) respondents highlighted the importance of discussing mode of delivery, yet only 31% of HCPs (n = 25) correctly stated that caesarean birth was mandatory for this patient with perianal disease and a seton in situ. Only 12% of HCPs (n = 10) acknowledged the need for extra growth scans in scenario 2 and/or 3 where the patients had evidence of active disease and therefore were at higher risk of low birth weight. Similarly, only 9% (n = 7) acknowledged the venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk in these cases with active disease.

Most respondents (n = 71, 88%) gave appropriate advice regarding the use of antitumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy during pregnancy in scenario 1 and/or 2. Of these, 54 of 81 (67%) respondents gave comprehensive advice, demonstrating excellent understanding including documenting whether to continue or cease biologic therapy during the third trimester. However, only 46% (n = 37) of HCPs discussed the importance of delaying live vaccines in the neonate, and 51% (n = 42) discussed the benefits of breastfeeding following antenatal biologic exposure.

Discussion

Almost all HCPs in our study demonstrated very good objective pregnancy-related IBD knowledge (median CCPKnow score 16/17) with minimal variation between HCP roles. This is consistent with previous studies where the median CCPKnow scores were 17 among gastroenterologists and >15 in IBD clinical nurse specialists.12,21 Conversely, our study identified lower scores when assessing applied knowledge via patient scenarios, with no participants achieving more than 70% of the maximum attainable score. This suggests that despite “good” theoretical pregnancy-related IBD knowledge, applied knowledge among HCPs is less consistent.

Consultants and IBD clinical nurse specialists both scored well in the objective and applied knowledge assessments. This supports the role of experienced IBD clinical nurse specialists in providing accessible IBD-specific pregnancy advice to patients under the care of a gastroenterology consultant, in line with the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) 2020 standards.8 It is reassuring that HCP self-rated knowledge and comfort scores both correlated well with CCPKnow and scenario scores, and self-rated knowledge scores also strongly correlated with self-rated comfort scores. This contrasts previous data among general practitioners, which demonstrated that 37% felt uncomfortable managing IBD patients; no correlation between comfort and knowledge levels was identified.25 Our findings suggest that gastroenterology HCPs are more aware of their limitations and would be likely to seek advice from a colleague with relevant expertise if they lacked clinical prowess in this area.

Recent guidance from the BSG advocates for the implementation of combined IBD-pregnancy clinics or at least a nominated link clinician within both the IBD and obstetric team.8 This can help to prevent conflicting and ambiguous advice and ensure effective multi-disciplinary decision-making. We found that less than half of our respondents (42%) had access to a specialized IBD pregnancy team. This contrasts with the findings of a UK nationwide survey in 2020, in which Wolloff et al noted that only 14% of responding units had access to a combined obstetric and gastroenterology clinic, and IBD antenatal care was provided by patients’ usual gastroenterologist in 86% of units.26 In our study, we found that the availability of a dedicated IBD pregnancy team was not significantly associated with improved objective or applied knowledge scores. However, increased involvement with IBD patients and specifically pregnant IBD patients was significantly associated with both higher CCPKnow and scenario scores, as was more years of clinical practice. This suggests that even in the absence of a dedicated clinic, clinical experience and education of gastroenterology HCPs on pregnancy-related IBD issues may help to optimize patient care and thus maternofetal pregnancy outcomes. Although dedicated IBD pregnancy clinics can provide consistent expert care, we found that clinician IBD expertise and, in particular, IBD-related antenatal experience may be more important in optimizing care for this complex patient group.

We identified several important pregnancy-related IBD topics that many respondents neglected to identify as relevant points to address in their clinical practice. These knowledge gaps and inconsistencies in management represent important areas of unmet need. For example, there is clear guidance regarding the necessity for an elective caesarean birth in the context of active perianal disease.2,8–10 However, only one-third of HCPs stipulated that the patient in scenario 1 with perianal disease requires a caesarean birth. This contrasts with the findings of Wolloff et al, where 94% of respondents acknowledged that active perianal disease was an indication for an elective caesarean birth,26 and the Mediterranean study where 87% of responding patients did not believe that IBD influences mode of delivery.14 It could be argued that the presence of a seton without drainage in scenario 1 does not constitute active disease and thus does not mandate a caesarean birth. There is some data to suggest that vaginal delivery in cases of inactive perianal disease is not associated with subsequent perianal flare-ups.27 However, women with perianal CD—irrespective of disease activity—have a higher risk of perineal tears after normal vaginal delivery.28 The AGA guidance advises caesarean birth for women with history of rectovaginal fistulae and avoiding perineal trauma in women with perineal involvement or previous perineal surgery.10 We would therefore argue that vaginal delivery in this scenario could lead to a tear involving the fistula tract, which could result in adverse long-term outcomes. Together, this highlights the importance of educating both HCPs and patients about decisions pertaining to delivery in IBD to prevent potential complications resulting from inappropriate vaginal delivery in the setting of active perianal disease.

The majority of HCPs demonstrated good understanding of the safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy. This likely reflects the growing evidence that anti-TNF exposure does not negatively impact pregnancy or infant outcomes.29 However, despite the majority of respondents acknowledging the safety of biologics and the greater importance of optimizing disease activity during pregnancy, many HCPs still chose to discontinue anti-TNF therapy before the third trimester. This is likely because the concept of continuing biologic therapy throughout pregnancy is a relatively new concept, with 2015 ECCO (European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation) guidelines advising stopping biologics as early as week 24.2 Large cohort studies and subsequent international guidelines have since demonstrated no increased risk of infant infection or maternofetal adverse outcomes with continuation beyond 30 weeks.5,9,10,29

Additional growth scans are advised during the third trimester in women with active IBD.8,10 Although there is no formal guidance to mandate this, it is well-recognized that active disease during pregnancy increases the risk of low birth weight babies and babies small for their gestational age.5–7 Only the minority (12%) of respondents suggested this in scenarios where there was a clear indication for extra growth scanning due to active IBD. This contrasts a prior study where 94% of respondents acknowledged that additional growth scanning was indicated in poorly controlled IBD.26 Although it could be argued that the frequency of growth scanning is predominantly determined by the obstetric team, members of the IBD team need to be aware of these requirements and communicate effectively with patients and obstetricians to ensure optimal pregnancy outcomes.

The CCPKnow was originally developed as a patient knowledge assessment tool using feedback from patients, IBD clinical nurse specialists and gastroenterologists to maximize content validity.12 Previous studies have mostly focused on using the CCPKnow score to assess patient knowledge, as it was originally intended. Patient knowledge assessed by the CCPKnow score has been demonstrated to be poor, with about 50% of patient cohorts surveyed consistently scoring ≤7.11-13,18 There is limited literature where the CCPKnow tool has been used to assess HCP pregnancy-specific IBD knowledge. As part of its validation process, the tool was assessed in hospital staff with differing levels of IBD knowledge, with poor knowledge demonstrated in clerical staff and general staff nurses, adequate knowledge in junior doctors, and very good knowledge in IBD specialist nurses.12 Kashkooli et al evaluated CCPKnow scores in different HCP roles involved in the care of pregnant IBD patients. They demonstrated overall better pregnancy-related IBD knowledge in gastroenterologists compared with obstetricians and general practitioners, with median CCPKnow scores of 17, 13, and 11, respectively.21 Although the data are scarce, these data including our findings suggest that CCPKnow is a reliable tool to test basic nongastroenterologist HCP knowledge for managing pregnant patients with IBD but is probably not sufficient to assess more specialist IBD-specific pregnancy knowledge in gastroenterologists.

Our study has its strengths but is not without limitations. One of the major strengths of our study is the inclusion of HCPs with varying backgrounds and levels of clinical experience from multiple international centers, reflective of the real-world nature of IBD practice. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess both objective and applied knowledge in HCPs via the CCPKnow and patient-based scenarios. Limitations of our study include a relatively small sample size and potential selection bias, as those choosing to respond to the survey may be more likely to have a subspecialty interest in IBD and/or pregnancy in IBD. This may have artificially inflated the knowledge scores; however, it may have also facilitated identification of the specific knowledge gaps within the knowledge sphere of pregnancy and IBD. Furthermore, the CCPKnow questionnaire was originally developed to assess pregnancy-specific IBD knowledge among patients rather than among HCPs; therefore, it may have not adequately tested the limits of HCP knowledge.12,21 Although many of the topics in the scenario assessments were also addressed in CCPKnow such as mode of delivery and risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, there are other scenario topics that were not addressed in CCPKnow such as neonatal vaccinations and risk of VTE.12 In a novel way of performing qualitative medical research, the scenario questions were completed as free-text responses. Therefore, scores may have been artificially lowered if participants lacked sufficient time or enthusiasm to complete their responses. Although we tried to standardize the scoring criteria, we acknowledge an element of potential bias in marking the scenarios. This was minimized by 2 authors independently scoring 30 scenarios and demonstrating consistency in scoring.

In conclusion, despite very good theoretical knowledge among HCPs, clinician application of knowledge in decision-making assessments is less consistent. More frequent management of IBD patients particularly during pregnancy and greater seniority in clinical roles were predictive of greater objective and applied knowledge scores. The knowledge gaps and inconsistencies demonstrated in our study are a likely pointer to a “tip of the iceberg” effect from the hidden burden of knowledge gaps in pregnancy and IBD and implications for optimal care of pregnant women living with IBD. To provide high-quality advice to patients, HCPs require theoretical and applied expert knowledge in the field of IBD reproductive care. Management of IBD in pregnancy should be addressed through educational initiatives, opportunities for clinical experience for HCPs, and dissemination of up to date standardized guidance to all gastroenterology team members. Improved clinician knowledge will enrich patient education, enabling HCPs and patients to make informed decisions preconception, during pregnancy, and postpartum, compressing avoidable morbidity and resulting in an overall improvement in the quality of care for women with IBD.

Abbreviations:

- HCPs

health care professionals

- CCPKnow

Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge score

- CNS

clinical nurse specialist

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

- BSG

British Society of Gastroenterology

- ECCO

European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation

Author Contribution

E.L., R.L., R.W.L., A.F., C.S., and J.K.L. devised the study and survey. E.L., R.L., C.S., and J.K.L. distributed the survey. E.L. and R.L. performed data collection and initial analysis of data. E.L. performed the literature review, wrote and edited the draft manuscript. R.L. performed the statistical analysis and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.S., J.K.L., R.W.L., and A.F. critically revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Conflicts of Interest

No authors report financial support or conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Author notes

Co-first authors