-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Bharati Kochar, Lakshman Kalasapudi, Nneka N Ufere, Ryan D Nipp, Ashwin N Ananthakrishnan, Christine S Ritchie, Systematic Review of Inclusion and Analysis of Older Adults in Randomized Controlled Trials of Medications Used to Treat Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 27, Issue 9, September 2021, Pages 1541–1543, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izab052

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), comprising Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic conditions affecting nearly 7 million people worldwide.1 Because of more effective treatments, improved life expectancy, and the global rise in IBD incidence and prevalence, the number of older adults with IBD is rapidly increasing, especially in Western nations.2 Although IBD is traditionally diagnosed in younger adults, 26% of Americans with IBD are aged ≥65 years.3 Globally, the highest peaks of age-specific prevalence rates for IBD occur between ages 60 and 64 years for women and 70 and 74 years for men.1

Older adults diagnosed with UC have a 57% higher rate of surgery, and older adults diagnosed with CD have nearly 6 times the IBD-specific mortality compared with younger patients.4 These considerable disparities may result from a paucity of data on the optimal medical management of older patients. Older adults are underrepresented in clinical trials across many fields.5, 6 Because the number of older adults with IBD is rapidly increasing, it is important to understand the generalizability of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that guide disease management. To date, there is no assessment of trial design and inclusion of older adults in clinical trials to guide the practice of IBD treatment. In this study, we examined the inclusion and analysis of older adults in RCTs of medications approved to treat IBD.

METHODS

We searched for published RCTs of currently approved IBD medications. The search strategy used in PubMed was as follows: “((Randomized Controlled Trial) AND (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) AND (adult)) AND ((ulcerative colitis) OR (Crohn’s disease)).” We restricted the results to trials published during or after 2000. In parallel to previous work in general medicine,6 we included articles from 4 leading general medicine journals and 4 leading gastroenterology (GI) journals, selected by impact factor, to focus our findings on the studies that are most likely to affect routine clinical practice. The general medicine journals were the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association, Lancet, and the British Medical Journal. The GI journals were Gut, Gastroenterology, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and the American Journal of Gastroenterology. To ensure that we did not miss any practice-guiding RCTs, we hand-searched references of recent systematic reviews of trials in IBD.

To focus the results on those studies that impact routine clinical practice, we excluded trials that included patients without IBD, pilot trials, phase 1 and 2 trials, dosing and formulation studies, cluster randomized trials, withdrawal trials, posthoc analyses of RCTs, trials that studied postoperative medical therapy, and trials that did not have an efficacy endpoint. In addition, we excluded trials that were an extension of an included trial, such as maintenance trials for patients enrolled in an included induction trial.

We constructed an abstraction spreadsheet modeled upon previous work.6 Abstracted information included the number of older adults in the intervention arm and control arm and exclusion criteria, including specific comorbidities, age-specific subgroup analyses, and the presence of functional status or cognitive decline as an exclusion criterion or outcome. We assessed the number of adults aged ≥65 years in each manuscript and reported the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

RESULTS

Our search strategy identified 1697 articles. Restricting the results to articles published in 2000 or later resulted in 1261 articles identified. Further restricting those 1261 articles to articles published in the 4 highest-impact general medical journals and 4 highest-impact GI journals resulted in 334 articles identified. A review of titles to ensure that the articles met our inclusion and exclusion criteria shrank the results to 108 articles. Abstract review of these articles further revealed that 67 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A review of the full texts resulted in eliminating 21 articles. We included a total of 46 RCTs, 23 for CD and 23 for UC, in this systematic review (see Table 1). The RCTs included 19,571 patients with IBD. There were 4 trials of mesalamine formulations; 13 trials of nonbiologic immunosuppression drugs, including immunomodulators, budesonide, cyclosporine, and tofacitinib; and 29 trials of biologic agents.

Trials Included in a Systematic Review of RCTs of Medications Approved for the Treatment of IBD

| . | n . |

|---|---|

| Total number of manuscripts | 46 |

| Trials of nonimmunosuppressive medications (%) | 4 (9) |

| Trials of biologics (%) | 29 (63) |

| Trials of other immunosuppression medications (%) | 13 (28) |

| Range of mean age | 31-45 y |

| Range of median age | 25-45 y |

| RCTs that indicated whether adults aged ≥65 y were included (%) | 26 (57) |

| RCTs that reported an age-specific subgroup analysis (%) | 5 (11) |

| RCTs that reported an upper age limit as an exclusion (%) | 18 (39) |

| Upper age limit: 65 y | 1 (2) |

| Upper age limit: 70 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 75 y | 8 (17) |

| Upper age limit: 80 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 85 y | 1 (2) |

| Exclusion criteria that disproportionately affect older adults (%) | |

| History of malignancy | 25 (59) |

| Nonmalignant, noninfectious comorbidities | 29 (64) |

| Functional status | 0 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 (2) |

| RCTs with functional status as an outcome | 0 |

| . | n . |

|---|---|

| Total number of manuscripts | 46 |

| Trials of nonimmunosuppressive medications (%) | 4 (9) |

| Trials of biologics (%) | 29 (63) |

| Trials of other immunosuppression medications (%) | 13 (28) |

| Range of mean age | 31-45 y |

| Range of median age | 25-45 y |

| RCTs that indicated whether adults aged ≥65 y were included (%) | 26 (57) |

| RCTs that reported an age-specific subgroup analysis (%) | 5 (11) |

| RCTs that reported an upper age limit as an exclusion (%) | 18 (39) |

| Upper age limit: 65 y | 1 (2) |

| Upper age limit: 70 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 75 y | 8 (17) |

| Upper age limit: 80 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 85 y | 1 (2) |

| Exclusion criteria that disproportionately affect older adults (%) | |

| History of malignancy | 25 (59) |

| Nonmalignant, noninfectious comorbidities | 29 (64) |

| Functional status | 0 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 (2) |

| RCTs with functional status as an outcome | 0 |

Trials Included in a Systematic Review of RCTs of Medications Approved for the Treatment of IBD

| . | n . |

|---|---|

| Total number of manuscripts | 46 |

| Trials of nonimmunosuppressive medications (%) | 4 (9) |

| Trials of biologics (%) | 29 (63) |

| Trials of other immunosuppression medications (%) | 13 (28) |

| Range of mean age | 31-45 y |

| Range of median age | 25-45 y |

| RCTs that indicated whether adults aged ≥65 y were included (%) | 26 (57) |

| RCTs that reported an age-specific subgroup analysis (%) | 5 (11) |

| RCTs that reported an upper age limit as an exclusion (%) | 18 (39) |

| Upper age limit: 65 y | 1 (2) |

| Upper age limit: 70 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 75 y | 8 (17) |

| Upper age limit: 80 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 85 y | 1 (2) |

| Exclusion criteria that disproportionately affect older adults (%) | |

| History of malignancy | 25 (59) |

| Nonmalignant, noninfectious comorbidities | 29 (64) |

| Functional status | 0 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 (2) |

| RCTs with functional status as an outcome | 0 |

| . | n . |

|---|---|

| Total number of manuscripts | 46 |

| Trials of nonimmunosuppressive medications (%) | 4 (9) |

| Trials of biologics (%) | 29 (63) |

| Trials of other immunosuppression medications (%) | 13 (28) |

| Range of mean age | 31-45 y |

| Range of median age | 25-45 y |

| RCTs that indicated whether adults aged ≥65 y were included (%) | 26 (57) |

| RCTs that reported an age-specific subgroup analysis (%) | 5 (11) |

| RCTs that reported an upper age limit as an exclusion (%) | 18 (39) |

| Upper age limit: 65 y | 1 (2) |

| Upper age limit: 70 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 75 y | 8 (17) |

| Upper age limit: 80 y | 4 (9) |

| Upper age limit: 85 y | 1 (2) |

| Exclusion criteria that disproportionately affect older adults (%) | |

| History of malignancy | 25 (59) |

| Nonmalignant, noninfectious comorbidities | 29 (64) |

| Functional status | 0 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 (2) |

| RCTs with functional status as an outcome | 0 |

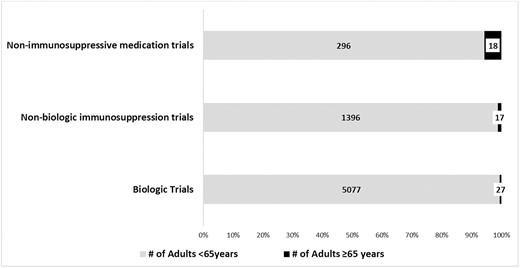

The 46 RCTs reported upper mean and median ages of 45 years. Only 39% of RCTs specified an upper age limit, which ranged from 65 to 85 years, as an exclusion criterion. Of the 46 trials, only 26 (57%) indicated in the manuscript whether adults aged ≥65 years were included in the study; 18 of these 26 trials included adults aged ≥65 years (Fig. 1).

Older adult inclusion in RCTs of medications approved to treat IBD stratified by class of medication.

The 18 trials that reported enrolling adults aged ≥65 years included 6831 patients. In these 18 trials, 62 patients (0.9%) were aged ≥65 years. In biologic trials including 5104 patients, 0.5% were aged ≥65 years. In nonbiologic immunosuppressive trials including 1413 patients, 1.2% were aged ≥65 years. In trials of mesalamine formulations including 314 participants, 5.7% were aged ≥65 years. Only 11% of trials reported age-specific subgroup analyses.

The majority of trials (64%) used nonmalignant comorbidities that disproportionately affected older adults as exclusion criteria. Malignancy history was an exclusion criterion in 59% of RCTs. Only 1 trial included cognitive impairment as an exclusion criterion. No RCTs included functional status for inclusion, exclusion, or outcomes.

Discussion

In this systematic review of older adult inclusion in RCTs of medications approved to treat IBD, we found that <1% of participants were aged ≥65 years. This finding is in stark contrast to the expanding body of data highlighting the increasing number of older adults with IBD.1, 2 Research has shown that IBD has a well-described bimodal peak of incidence; with effective treatments, preserved life expectancy, and aging, the population of older adults with IBD is rapidly increasing. It is clear that IBD RCTs need to provide proportionate representation of older adults.

Older adults with IBD experience worse outcomes than younger patients.4 Our review revealed that trials of mesalamine agents had the highest proportion of older adults and trials of biologic agents had the lowest proportion of older adults. This trend may be a reflection of the general perception that biologic agents confer great risks. The reluctance in practice to treat older adults with IBD with biologic agents may be because of the lower number of older adults included in trials, resulting in a cycle of undertreatment. As treatment with biologic agents becomes a mainstay of IBD treatment and the number of older adults with IBD continues to expand, intentional efforts to increase the representation of older adults in trials of modern biologics for the treatment of IBD will be essential.

Upper age limits, comorbidities—especially when they are vaguely phrased—and any history of malignancy represent major barriers that disproportionately affect older adult participation in clinical trials.6 We showed that more than half of IBD clinical trials had 1 or more of these factors that pose barriers to the recruitment and enrollment of older adults. Exclusion criteria should be justified with biologically relevant properties of the study medication, such as heart failure for trials of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents. This information may increase older adult trial eligibility and make the registration trials more generalizable to the patients we treat in practice.

We also found that no IBD RCTs included functional status either for inclusion or as an outcome. As patients with IBD age and younger patients have more multiple morbidities, functional status should be considered. For example, functional status indices are routinely implemented before chemotherapy to identify patients at greater risk.7 Previous research has shown that frailty confers a significantly higher risk for infections after immunosuppression for IBD.8 Including functional status for trial eligibility will also serve to expand the number of older adults represented in IBD RCTs.

Conclusions

Despite the high prevalence of IBD at older ages, a negligible proportion of older adults is included in clinical trials. Current trial practices should systematically seek to assure the proportional representation of older adults with IBD in IBD clinical trials.

Supported by: Funding for this study was supported in part by a Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award (568735 to BK).

Conflicts of interest: BK has been on the advisory board for Pfizer. ANA has received research funding from Pfizer and has been on the scientific advisory board for Kyn Therapeutics.

References