-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Subrata Ghosh, Edouard Louis, Laurent Beaugerie, Peter Bossuyt, Guillaume Bouguen, Arnaud Bourreille, Marc Ferrante, Denis Franchimont, Karen Frost, Xavier Hebuterne, John K. Marshall, Ciara O'Shea, Greg Rosenfeld, Chadwick Williams, Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet, Development of the IBD Disk: A Visual Self-administered Tool for Assessing Disability in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 23, Issue 3, 1 March 2017, Pages 333–340, https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000001033

Close - Share Icon Share

The Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Disability Index is a validated tool that evaluates functional status; however, it is used mainly in the clinical trial setting. We describe the use of an iterative Delphi consensus process to develop the IBD Disk—a shortened, self-administered adaption of the validated IBD Disability Index—to give immediate visual representation of patient-reported IBD-related disability.

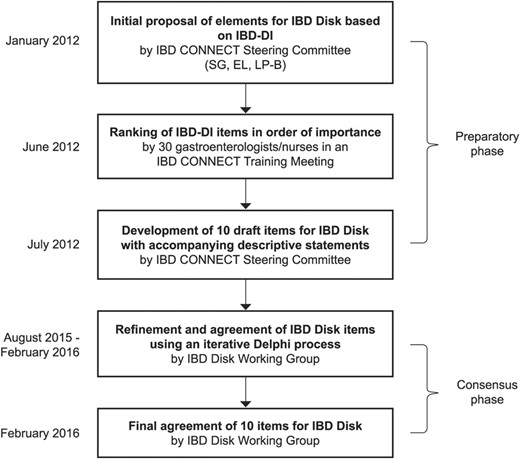

In the preparatory phase, the IBD CONNECT group (30 health care professionals) ranked IBD Disability Index items in the perceived order of importance. The Steering Committee then selected 10 items from the IBD Disability Index to take forward for inclusion in the IBD Disk. In the consensus phase, the items were refined and agreed by the IBD Disk Working Group (14 gastroenterologists) using an online iterative Delphi consensus process. Members could also suggest new element(s) or recommend changes to included elements. The final items for the IBD Disk were agreed in February 2016.

After 4 rounds of voting, the following 10 items were agreed for inclusion in the IBD Disk: abdominal pain, body image, education and work, emotions, energy, interpersonal interactions, joint pain, regulating defecation, sexual functions, and sleep. All elements, except sexual functions, were included in the validated IBD Disability Index.

The IBD Disk has the potential to be a valuable tool for use at a clinical visit. It can facilitate assessment of inflammatory bowel disease-related disability relevant to both patients and physicians, discussion on specific disability-related issues, and tracking changes in disease burden over time.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has a substantial and multifaceted burden, characterized by distressing and debilitating symptoms that can restrict the affected patient's freedom, diminish their physical and psychological well-being, reduce productivity, and isolate them socially.1,–9 A recent survey performed by the European Federation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Associations and involving 4670 patients with IBD found that 67% of respondents frequently considered the availability of toilets when planning to attend an event, 60% felt stressed or pressured about taking sick leave from work due to IBD, 56% felt that IBD had affected their career path, and 35% felt that IBD had prevented them from pursuing an intimate relationship.1

Addressing and improving the cumulative burden of disease, returning to a “normal life,” and preventing disability are now major therapeutic goals in IBD.10 Because of this, it is increasingly important to monitor aspects of functioning and disability in the patient with IBD in addition to assessing the clinical and inflammatory manifestations of the disease.10,–12 The IBD Disability Index (IBD-DI) is a physician-administered tool that evaluates the functional status of patients with IBD.13,–15 The IBD-DI was developed using a formal consensus process16 that integrated evidence from preparatory studies and expert opinion based on categories from the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).17 Participants involved in the consensus process provided a balanced representation of all relevant health professions and all World Health Organization-designated world regions. The IBD-DI has recently been validated for use in clinical trials and epidemiological studies and shows high internal consistency, interobserver reliability, and construct validity, with moderate intraobserver reliability.15

While the IBD-DI provides a robust means of assessing IBD-related disability, it needs to be administered by a health care professional and is mainly for use in the clinical trial setting. We propose that a shortened, patient-friendly adaption of the IBD-DI, comprising items that have undergone rigorous validation, would be useful for monitoring disability in the IBD outpatient. In order for the tool to stimulate meaningful patient–physician dialogue, it needs to focus on items that are useful to both the patient and the physician.

The development of self-administered versions of disease monitoring instruments is becoming an area of interest in the outpatient setting, potentially allowing remote monitoring of health.18 As an example, a 10-item visual instrument, known as the Psodisk, has been developed and validated in patients with psoriasis.19,–21 The Psodisk is a patient-reported outcome measure that includes items relevant to disability and provides the physician and patient with an immediate and intuitive visual representation of the disease burden for that individual. Changes in disease burden over time can also be assessed if the Psodisk is used regularly.

In this article, we describe the use of an iterative Delphi consensus process to develop the IBD Disk—a self-administered and shortened adaption of the validated IBD-DI. The IBD Disk application is based on the Psodisk platform and can be used in the outpatient setting to give immediate visual representation of patient-reported IBD-related disability.

Materials and Methods

The methodology for developing the IBD Disk is shown in Figure 1. The development of the IBD Disk was initially an effort of IBD CONNECT, an international educational program designed to provide training and tools (including essential motivational interviewing techniques) to improve collaboration and communication between health care professionals and their patients with IBD (see Acknowledgement). In the preparatory phase of the process, the IBD CONNECT Steering Committee (S.G., E.L., L.P-B.) proposed that the elements for the IBD Disk be based on the validated IBD-DI.13 To ensure that the tool would be useful in the outpatient setting, it was decided to limit the number of items included to 10. Participants in an IBD CONNECT meeting (30 global gastroenterologists and nurses; Prague, Czech Republic; May 11–12, 2012) then completed a paper-based survey that ranked the IBD-DI items in order of importance (i.e., relevance to both the patient and physician) and collected general feedback on which items should be included in the IBD Disk. The Steering Committee reviewed feedback and selected 10 draft items by consensus from the IBD-DI, with accompanying descriptive statements, for the IBD Disk.

Between August 2015 and February 2016, the IBD Disk Working Group (comprised of 14 gastroenterologists from Belgium, Canada, and France) used an iterative Delphi process to refine and agree to the IBD Disk items proposed by the IBD CONNECT program. Communication was solely through an online platform. The Working Group members were asked to rank each of the selected items from the IBD-DI in the order of importance. In addition, a free text space allowed members to suggest new element(s) (including those not in the IBD-DI) or recommend changes to/deletions of included elements. The level of agreement for new suggestions was determined in the subsequent voting round; suggestions meeting 75% or more agreement were accepted. After each round of feedback, the modified proposal was recirculated. The final items for the IBD Disk were agreed in February 2016.

Results

Preparatory Phase

Participants in the IBD CONNECT meeting ranked 19 IBD-DI items in the perceived order of importance (Table 1). “General health,” “abdominal pain,” and “energy” were the 3 items ranked as most important, whereas “abdominal pain,” “energy,” and “regulating defecation” were the items selected most frequently.

Based on the feedback given, the Steering Committee proposed 10 draft items with accompanying descriptive statements for the IBD Disk (Table 1). Given the similarity and overlap of some items, it was decided to group some elements together (e.g., difficulty with school or studying activities and difficulty with work or household activities under the heading of “education and work”; feeling sad, low, or depressed and feeling worried or anxious under the heading of “emotions”; and difficulty with a personal relationship and difficulty participating in the community under the heading of “interpersonal interactions”). It was also agreed to include “sexual functions” from the comprehensive ICF core set.

Consensus Phase

The 14 Working Group members completed 4 rounds of voting to achieve consensus on elements to include in the IBD Disk.

Round 1

“Emotions and work” was ranked as the most important, followed by “regulating defecation.” “Sexual functions” was considered the least important. The only new suggestion was to include “pain in joints” as an additional item, taken from the IBD-DI and the comprehensive ICF core set.

Round 2

“Emotions and work” and “regulating defecation” remained the most important items and “pain in joints” was the least important. Two suggestions were made: first, “sexual functions” should be removed as it is not included in the validated IBD-DI, and second, “sleep” and “energy” should be combined as they are included as a single item in the validated IBD-DI. No new elements were proposed.

Round 3

Participants voted to retain “sexual functions” as an item and to retain “sleep” and “energy” as separate items. It was suggested that “general health” be removed. No new elements were proposed.

Round 4

It was agreed to remove “general health” from the IBD Disk. No new elements were proposed.

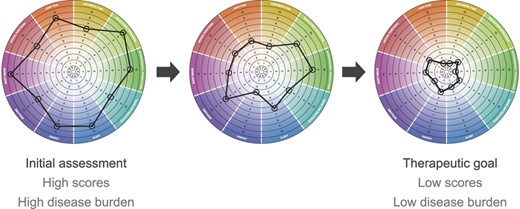

The final IBD Disk included 10 items (Table 1). The tool comprises a questionnaire with an explanatory statement for each of the items, which should be scored on a disc-shaped visual analog scale from 0 (absolutely disagree) to 10 (absolutely agree) (Fig. 2). All included elements, except “sexual functions,” were included in the validated IBD-DI. “Sexual functions” is included from the comprehensive ICF core set.

Discussion

One of the major therapeutic goals in IBD clinical practice is to prevent disability and to minimize disruption to the patient's education, work, family, and social life. This goal requires long-term collaboration between a patient and their gastroenterology team. Indeed, studies have shown that patient satisfaction with health care is largely influenced by their interactions with health care professionals,22,–26 with suggestion that improved patient engagement leads to improved treatment adherence and outcomes.27,–31

However, there is often a discrepancy between the perspective of the health care professional and the patient. Health care professionals may underestimate the impact that IBD has on the patient's daily life,32 or they may misinterpret what matters most to patients about their disease.33 As indicated by the European Federation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Associations survey, patients often have difficulty in expressing their needs to their health care professional or are not asked probing questions that reveal the true impact of their disease.1 Part of this disconnect may be attributed to the lack of suitable or accessible tools with which to illicit and monitor key markers of disease burden or disability in outpatients with IBD.34

The IBD-DI is a physician-administered tool that captures specific objective items that describe what it means to live with IBD.13 The published version of the questionnaire comprises 28 items: 18 items that cover different aspects of disability across the 3 domains of body functions, body structures, and activities and participation; 8 supplemental items that provide information about how the patient's environment interacts with their disease; and 2 items relating to social security and access to the health care system.13 These items were rigorously generated through a comprehensive process involving patient concept elicitation interviews, expert interviews, item generation, content validity, patient cognitive interviews, and a quantitative study. A modified version of the IBD-DI comprising 14 disability-related questions (general health, sleep, energy, emotions [feeling sad/depressed and feeling worried/anxious], body image, abdominal pain, regulating defecation, looking after one's health, interpersonal activities [difficulty with personal relationships/difficulty with community participation], work, education, and number of liquid/very soft stools) was recently rigorously validated in an independent population-based cohort of patients with IBD in France.15

The IBD Disk was developed using a consensus-based process to select elements from the IBD-DI that are most likely to be important in assessing a patient's disease burden and had relevance to both the patient and physician. Several items (difficulties with work/education and feeling depressed/anxious) were combined owing to similarities in concept. In addition, the IBD CONNECT Steering Committee suggested inclusion of “sexual functions” from the ICF comprehensive core set.17 Sexual dysfunction is a common concern in patients with IBD and may be present in approximately half of women and a quarter of men with IBD.35 Based on clinical experience, the Steering Committee considered that sexual dysfunction was likely to be important to patients and may not have been captured in the development of the IBD-DI because patients felt uncomfortable discussing the topic in the preparatory discussions. The Working Group agreed to include this item. The Working Group later also agreed to include “joint pain,” from the IBD-DI and ICF core set. Articular involvement is the most common extraintestinal manifestation in IBD, even in patients who are in clinical and endoscopic IBD remission. A recent Swiss cohort study found 44% of patients with IBD have inflammatory articular disease.36 The Working Group considered that it was important to include “joint pain” in the IBD Disk, as patients do not always attribute this to IBD and it may be a relevant point for discussion in a clinical consultation. In the last round of voting, “General health” was excluded from the IBD Disk, as the wide range of specific items now included in the disk covered the key elements of disability associated with IBD. The Working Group also felt that keeping the number of items to 10 would facilitate the use of the tool in clinical practice.

The resulting IBD Disk questionnaire and scoring disk (Fig. 2) fit on a single page that would be easy to translate and administer to patients before or during a clinic visit. A hypothetical example of how a patient's IBD Disk assessment provides a visual representation of disease burden and may change over time with good disease management is shown in Figure 3.

Hypothetical example of how a patient's IBD Disk assessment may change over time with good disease management.

The IBD Disk could be used to track changes in disease burden over time, assess and monitor treatment efficacy in terms of disease burden, and set short-term and long-term goals. Regular completion of the IBD Disk, together with regular clinical assessments during clinic visits may provide a more complete picture of the patient's overall health, well-being, and disease state. Short-term goals that include reducing the IBD Disk scores for all or selected elements could be set and monitored over time, and treatment modified as required if goals are not reached. Explanations for changes in any specific element may be explored further at the clinic. Monitoring to achieve longer term goals of keeping IBD Disk scores low could provide information on the efficacy of and adherence to maintenance treatment. It will also be a good tool for a patient-centered conversation at follow-up visits.

This use of visual feedback to allow patients to see changes in their disease status may create a new experience for the patient and translate into potential improvements in understanding, behavior and treatment adherence. Furthermore, inclusion of items that are of relevance to both the patient and health care professional should allow meaningful dialogue between the 2 parties. This can be helpful for goal setting and shared decision making in a chronic condition such as IBD, which should be based on participatory medicine, mutual respect, patient engagement, and communication.

Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, there is currently a lack of evidence in the literature evaluating how visual representation of disease state may impact patient outcomes. Further work should include assessment of changes in health behaviors in patients who measure their IBD burden with the IBD Disk.

It must be acknowledged that one of the possible shortcomings of this tool is the lack of direct patient involvement in selection of the items for inclusion. Nevertheless, items were obtained from the IBD-DI and ICF core set, which were developed based on analysis of a qualitative study (6 focus groups with 26 participants) to identify aspects of the “lived experience” of IBD and a multicenter cross-sectional study to describe functioning and health of persons with IBD. This gives us confidence that the components of the IBD Disk are meaningful to patients.

The next step for the IBD Disk will be to evaluate its operating characteristics in clinical practice as an outpatient tool in comparison to the IBD-DI, followed by validation of the capacity of the IBD Disk to assess changes in disability. As a potential value of the IBD Disk lies in the long-term monitoring of IBD-associated disability, some longitudinal studies will be needed. Studies that directly compare the IBD Disk and the IBD-DI—and other clinical and nonclinical measures—will also be useful.

In conclusion, the IBD Disk is a self-administered adaption of the validated IBD-DI that has the potential to be a valuable tool for assessing IBD-related disability experienced by the patient and promoting discussion on specific issues important to the patient and the health care professional during consultation.

Acknowledgments

Preparatory phase: Supported by AbbVie, who provided funding to the Lucid Group, Loudwater, United Kingdom, to manage the IBD CONNECT educational program in 2012. AbbVie paid consultancy and speaker fees to the Steering Committee members (S. Ghosh, E. Louis, and L. Peyrin-Biroulet) for their participation in a Steering Committee meeting (London, United Kingdom; January 6, 2012) and a training meeting (Prague, Czech Republic; May 11–12, 2012). Travel to and from these meetings was paid by AbbVie.

The authors acknowledge the preparatory work conducted by the IBD CONNECT participants in 2012. IBD CONNECT was an international educational program that provided training and tools to improve collaboration between health care professionals (gastroenterologists and IBD nurses) and their patients with IBD. Content included essential motivational interviewing skills, shared decision-making principles, and techniques to improve health literacy. IBD CONNECT ran from 2011 to 2014 and included annual training meetings. The program was led by a Steering Committee of health care professionals (including S. Ghosh, E. Louis, and L. Peyrin-Biroulet) and was sponsored by AbbVie.

Consensus phase: Supported by AbbVie, who provided funding to the Lucid Group, Loudwater, United Kingdom, to manage the delivery of consensus phase. AbbVie paid consultancy fees to the IBD Disk Working Group for their participation in the process.

Manuscript phase: The article was developed from recommendations made by the IBD Disk Working Group. Recommendations for the IBD Disk Working Group members were made by AbbVie. The authors maintained complete control over the content of the article and it reflects their opinions. No payments were made to the authors for the development or writing of this article. Juliette Allport of the Lucid Group provided editorial support to the authors in the development of this article; AbbVie paid the Lucid Group for this work. Payment of fees for Open Access was made by AbbVie.

The Steering Committee acknowledge the administrative and editorial support provided by Katherine Duxbury of the Lucid Group throughout the development of the IBD Disk 2012 to 2016.

S. Ghosh has received financial support for research from AbbVie and received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Receptos, Shire, and Takeda. E. Louis has received educational grants from AbbVie and MSD; speaker fees from AbbVie, Chiesi, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen, Mitsubishi Pharma, MSD, and Takeda; and advisory board fees from AbbVie, Celltrion, Ferring, Mitsubishi Pharma, MSD, Prometheus and Takeda. L. Beaugerie has received consulting fees from AbbVie and Janssen; lecture fees from AbbVie, Ferring, and MSD; and research support from AbbVie, Biocodex, and Ferring. P. Bossuyt has received educational grants from AbbVie; speaker fees from AbbVie, Takeda, and Vifor Pharma; and advisory board fees from Hospira, Janssen, MSD, Mundipharma, and Dr Falk Benelux. G. Bouguen has received consultancy fees from AbbVie and MSD; and lecture fees from AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, and Takeda. A. Bourreille has received educational grants from MSD; speaker fees from AbbVie, Ferring, Hospira, Medtronic, MSD, and Takeda; and advisory board fees from AbbVie, Ferring, Medtronic, MSD, and Takeda. M. Ferrante has received financial support for research from Takeda; lecture fees from AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, Falk, Ferring, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Janssen, Takeda, Tillotts Pharma, and Zeria; and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferring, Janssen, and MSD. D. Franchimont has received education grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from AbbVie and MSD; personal fees from Amgen, Ferring, Takeda, Mundipharma, Hospira, and Pfizer, outside of the submitted work. K. Frost has no financial support to report. X. Hebuterne has received funding from AbbVie, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, and Takeda for advisory activity as a member of an advisory board and from AbbVie, Arard, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Mayoli-Spindler, MSD, Nestlé, Norgine, Nutricia, and Takeda for educational activities. J. K. Marshall has received honoraria for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Allergan, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Shire, and Takeda. C. O'Shea, an AbbVie employee, may own AbbVie stock and/or options. G. Rosenfeld has received honoraria for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Pendopharm, Shire, and Takeda. C. Williams has received consulting and/or lecture fees from AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Shire, and Takeda and has been an advisory board participant for AbbVie, Janssen, and Takeda. L. Peyrin-Biroulet has received consulting fees from Merck, AbbVie, Janssen, Genentech, Mitsubishi, Ferring, Norgine, Tillots, Vifor, Therakos, Pharmacosmos, Pilège, BMS, UCB-pharma, Hospira, Celltrion, Takeda, Biogaran, Boerhinger-Ingelheim, Lilly, Pfizer, HAC-Pharma, Index Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Sandoz, Forward Pharma GmbH, Celgene, Biogen, Lycera, and Samsung Bioepis; and lecture fees from Merck, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Takeda, Ferring, Norgine, Tillots, Vifor, Therakos, Mitsubishi, and HAC-pharma.

References

Author notes

Author disclosures and funding are available in the Acknowledgments.