-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jae Seung Soh, Woo Jin Yun, Kyung-Jo Kim, Chong Hyun Won, Sang Hyoung Park, Dong-Hoon Yang, Byong Duk Ye, Jeong-Sik Byeon, Seung-Jae Myung, Suk-Kyun Yang, Jin-Ho Kim, Concomitant Use of Azathioprine/6-Mercaptopurine Decreases the Risk of Anti-TNF–Induced Skin Lesions, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 21, Issue 4, 1 April 2015, Pages 832–839, https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000342

Close - Share Icon Share

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents are widely used to treat patients with moderate-to-severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We aimed to identify the risk factors for adverse skin lesions in patients with IBD receiving anti-TNF agents and assess the effect of concomitant use of azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (AZA/6 MP).

A total of 500 patients (404 with Crohn's disease, 96 with ulcerative colitis) who received anti-TNF agents between June 2002 and July 2013 were identified and retrospectively investigated. We compared 47 patients with IBD with skin lesions with 443 patients with IBD without skin lesions to identify risk factors by univariate and multivariate analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of adverse skin lesions in relation to the concomitant use of AZA/6 MP.

Eczematiform eruptions (n = 18, 38%) were the most common skin lesion type, followed by psoriasiform lesions (n = 13, 28%). A response to topical steroids was seen in 70% (33/47) of patients with skin lesions, and anti-TNF agents had to be discontinued in 9% (4/47). Concomitant use of AZA/6 MP decreased the risk of skin lesions in univariate (hazard ratio, 0.452; 95% CI, 0.251–0.814; P = 0.008) and multivariate (hazard ratio, 0.437; 95% CI, 0.242–0.790; P = 0.006) analysis. In addition, the cumulative incidence of adverse skin lesions was lower in patients on concomitant maintenance with AZA/6 MP (P = 0.009) than in those on anti-TNF monotherapy.

Concomitant use of AZA/6 MP may decrease the occurrence of adverse skin lesions in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, but its cause is unclear.1 Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents not only induce remission but also maintain remission in moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)2,–4 and provide major therapeutic strategies in moderate-to-severe IBD. However, infrequent serious adverse events, such as infections, malignancies, demyelinating disease, and congestive heart failure have been reported.5 In addition, adverse skin reactions, also called paradoxical responses,6 occur in 5% to 22% of cases.7 This phenomenon has been reported in several studies and reviews of paradoxical eczematiform and psoriasiform skin lesions in patients with IBD receiving treatment with anti-TNF agents.6,8,–10 The outcomes of adverse skin events vary from a good response to topical agents as the sole treatment to the need to discontinue the anti-TNF treatment.8

Most previous studies of adverse skin reactions during anti-TNF treatment in patients with IBD have focused on dermatological manifestations,7,8,10,11 and few have evaluated the risk factors for paradoxical skin reactions.8,11,12 In this study, we classified adverse skin lesions in patients with IBD receiving anti-TNF agents and investigated the risk factors for these lesions. We also calculated the cumulative incidence of lesions in relation to the concomitant use of azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (AZA/6 MP).

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Between June 2002 and July 2013, a total of 2217 patients with CD and 2173 patients with UC were registered at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center of Asan Medical Center, a tertiary university hospital in Seoul, South Korea. CD and UC were diagnosed on the basis of conventional clinical, radiological, endoscopic, and histopathologic criteria.13,14 A total of 404 (18.2%) of the 2217 patients with CD and 96 (4.4%) of the 2173 patients with UC received anti-TNF agents (infliximab or adalimumab) over the same period. Adverse skin lesions associated with anti-TNF agents were defined as new-onset skin lesions or aggravation of skin lesions while being treated with an anti-TNF agent, as confirmed by 2 expert dermatologists (C.H.W., W.J.Y.).8 All adverse skin lesions were seen simultaneously at Asan Medical Center and treated by the above 2 dermatologists. Among 500 patients who received the anti-TNF agents, we identified 57 with adverse skin lesions. Of these, 10 were excluded because their skin lesions were associated with infections (n = 5) or were IBD-related (n = 5). In all, 47 patients (47/500, 9.4%) were classified as having adverse skin lesions associated with anti-TNF treatment. In addition, we compared the patients with adverse skin lesions with those without history of skin lesions during the period of use of the anti-TNF agents (n = 443).

Data Collection

Medical records were reviewed retrospectively. Information related to adverse skin lesions included the following data: number, distribution, location, presence of pigmentation, involved site, accompanying articular symptoms, presence of alopecia, type and dosage of anti-TNF agent, interval between the start of anti-TNF treatment and the appearance of skin lesions, dermatologic treatment, and response to treatment. The following patient data were also extracted: gender, age at diagnosis, disease duration, smoking status, family history of IBD, extraintestinal disease, duration of anti-TNF treatment, and number of agents infused, follow-up duration, and concomitant medication. The IBD was classified according to the Montreal classification.15 Smoking status was classified as current, exsmoker, or never smoker.

The skin lesions were treated in a variety of ways: by observation, topical steroids and/or antihistamine, systemic steroids, and other drugs including antibiotics. Outcomes were classified as either considerable improvement or only a partial response with persistence of the lesions. Pharmacological treatment for the underlying IBD consisted of concomitant use of AZA/6 MP or steroids from the start of anti-TNF treatment. The former were further divided into those receiving ongoing AZA/6 MP and those in whom AZA/6 MP was discontinued in the follow-up period. The patients treated with infliximab were infused with 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks after an induction dosage of 5 mg/kg in weeks 0, 2, and 6, whereas those treated with adalimumab were injected with 160 mg in week 0 and 80 mg in week 2, followed by 40 mg every 2 weeks.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No 2011-0963).

Statistical Analyses

Possible risk factors for skin lesions during the period of anti-TNF use were identified with a Cox proportional hazards model. Variables with P values less than 0.05 in a univariate analysis, and some confounding factors, were entered into a multivariate analysis, and a backward variable elimination procedure was used to assess the strength of the association while controlling for possible confounding variables. The cumulative incidence of skin lesions was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and subgroups were compared by the log rank test. We used SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) for all statistical analyses.

Results

Incidence and Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Adverse Skin Lesions

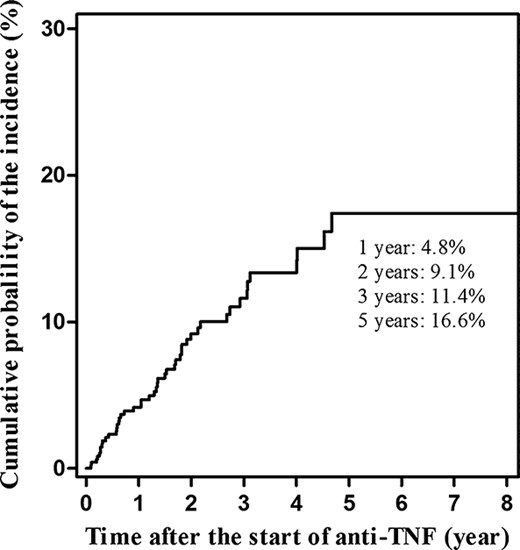

Forty-seven patients (9.4%) were confirmed as having adverse skin lesions during anti-TNF treatment. Of these, 42 (89%) received infliximab and 5 (11%) received adalimumab. The cumulative probabilities of the occurrence of skin lesions were 4.8%, 9.1%, 11.4%, and 16.6% after 1 year, 2, 3, and 5 years, respectively (Fig. 1). The incidence within the first 2 years was higher than in the following 3 years. Of the 47 subjects, 22 were men (male:female = ratio 1:1.13). The median age was 30 years (range, 15–66 yr). There were 6 (12.8%) current smokers. Eighteen patients (38.3%) suffered from extraintestinal manifestations associated with IBD. Most of the patients with CD were of the ileocolonic (79.1%) type and/or had perianal disease modifiers (67.4%). Regarding disease behavior, 16 patients (37.2%) had nonstricturing nonpenetrating disease, 10 (23.3%) had stricturing disease and 17 (39.5%) had penetrating disease. The median duration of anti-TNF treatment was 30 months (range, 1–94 mo), and the median number of infusions of anti-TNF agents was 18 (range, 2–78). The mean follow-up period was 105.5 months (range, 7–249 mo). Twenty-five patients (53.2%) received concomitant AZA/6 MP at the start of the anti-TNF treatment. The median dose was 25 mg (0.57 mg/kg) for AZA (range, 25–100 mg [0.41–2.42 mg/kg]) and 50 mg (1.05 mg/kg) for 6 MP (range, 25–75 mg [0.43–1.23 mg/kg]). Six patients (12.8%) received steroids at the start of the anti-TNF treatment (Table 2).

Cumulative probability of the incidence of adverse skin lesions occurring during treatment with anti-TNF agents in IBD.

Adverse skin lesions developed in 9.3% (42/453) of patients on infliximab and in 13.5% (5/37) of patients on adalimumab (P = 0.400). Of 13 patients with psoriasiform skin lesions, 11 (85%) received infliximab and 2 (15%) received adalimumab. All psoriasiform skin lesions occurred in patients with CD, and none occurred in patients with UC (P = 0.087). In the infliximab group, the median interval between starting anti-TNF and the occurrence of adverse skin lesions was 13.5 months (range, 1–56 mo), and the median number of infusions in that period was 9 (range, 1–38). In the adalimumab group, the median interval was 12 months (range, 8–35 mo) and the median number of injections was 10 (range, 10–51).

Classification and Characteristics of Skin Lesions

The most frequent adverse skin lesions were eczematiform (n = 18, 38%), followed by psoriasiform (n = 13, 28%) and acneiform (n = 7, 15%) lesions. Table 1 lists the other skin lesions. Figure 2 shows representative cases of the eczematiform (Fig. 2A, B) and psoriasiform (Fig. 2C) lesions induced by anti-TNF agents. The face was the most common involved location (n = 21, 45%), followed by the trunk (n = 18, 38%), upper extremities (n = 18, 38%), scalp (n = 17, 36%), and lower extremities (n = 10, 21%). Most of the skin lesions were multiple (n = 46, 98%) and symmetric (n = 35, 79%) in distribution. They were limited in 34 patients (72%). Eight patients (17%) had articular symptoms, and alopecia, including alopecia areata, was observed in 9 patients.

A, Eczematiform lesions of the lower extremities induced by infliximab. B, Eczematiform lesions of the face and neck induced by infliximab. C, Psoriasiform lesions of the trunk and extensor surface induced by infliximab.

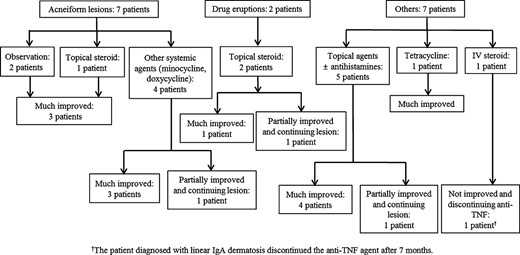

Thirty-four patients (72%) were treated with topical agents including steroids. Systemic steroids were required in only 2 patients (4%). Minocycline, doxycycline, or tetracycline was used in 7 patients (15%), and an antihistamine was used in 9 patients (19%). Four patients (9%) were simply observed without any treatment until their skin lesion improved. The lesions in 33 patients (70%) responded well to the initial treatment, but the skin lesions in the 14 other patients (30%) only partially improved and required continuous treatment in the Dermatology Department. Anti-TNF agents were stopped in 4 patients because of uncontrolled skin lesions (2 patients with eczematiform lesions, 1 with psoriasiform lesions, and 1 with linear immunoglobulin A dermatosis). In these 4 patients who discontinued anti-TNF agents, 1 patient with CD underwent a right hemicolectomy and small bowel resection and anastomosis and 1 patient with UC underwent a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis during the follow-up period. Of the remaining 2 patients, 1 patient commenced on AZA at a dose of 0.61 mg/kg and 1 patient has been receiving mesalamine and has been in clinical remission. No patient received a second anti-TNF agent. Figures 3–5 illustrate the treatment and responses of the patients with adverse skin lesions.

The treatment and response of patients with acneiform, drug eruption, and other skin lesions.

Risk Factors for Skin Lesions

Table 2 shows the results of univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with adverse skin lesions occurring during anti-TNF treatment. Female gender was associated with an increased risk of adverse skin lesions, whereas concomitant use of AZA/6 MP decreased the risk of adverse skin lesions. There was no association between the occurrence of adverse skin lesions and age at diagnosis, smoking history, family history of IBD, extraintestinal manifestations, months of anti-TNF treatment, number of infusions of anti-TNF agents, duration of follow-up, disease location, and disease behavior. In a multivariate analysis, only concomitant use of AZA/6 MP at the start of anti-TNF treatment decreased the risk of adverse skin lesions (P = 0.006).

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Skin Lesions Occurring During Treatment with Anti-TNF Agents in the Study Patients with IBD

|

|

|

|

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Skin Lesions Occurring During Treatment with Anti-TNF Agents in the Study Patients with IBD

|

|

|

|

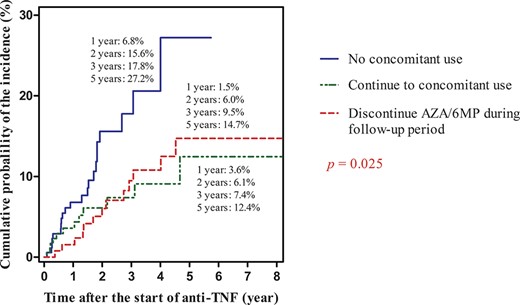

The cumulative probabilities of the incidence of adverse skin lesions in relation to concomitant use of AZA/6 MP at the start of anti-TNF agent treatment are shown in Figure 6. The cumulative probability of the incidence of adverse skin lesions was higher in patients on anti-TNF monotherapy than in those receiving concomitant AZA/6 MP, independent of discontinuation during the follow-up period (P = 0.025).

Cumulative probability of the incidence of adverse skin lesions in relation to concomitant use of AZA/6 MP at the start of anti-TNF agent treatment.

Discussion

Our current findings show that the incidence of all skin lesions among those receiving anti-TNF treatment was 9.4%. However, if we consider only adverse psoriasiform and eczematiform lesions, the incidence was 6.2%. The cumulative probability of the incidence of adverse skin lesions was 4.8%, 9.1%, 11.4%, and 16.6% at 1 year, 2, 3, and 5 years after the start of anti-TNF treatment, respectively. Concomitant use of AZA/6 MP decreased the risk of adverse skin lesions. The incidence of adverse skin lesions after the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with IBD varies between 5% and 22% in Western studies,8,10,–12 which is comparable with the rate seen in this study. The wide variation in incidence may be due to differences in the definitions and criteria for skin lesions.

Many skin lesions occurring in response to anti-TNF agents are associated with immune-mediated reactions.10,16 In particular, psoriatic lesions are closely connected to an imbalance between tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-α (IFN-α).16,–19 TNF-α normally inhibits the maturation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells from hematopoietic progenitors and IFN-α production. Hence, TNF-α inhibition by anti-TNF agents may allow the unlimited production of IFN-α by plasmacytoid dendritic cells and an increased pooling and sequestration of Th1 lymphocytes in the peripheral circulation.16 Accordingly, increased IFN-α expression was found in the dermal vasculature of patients receiving anti-TNF treatment, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration was observed in the affected skin.20

Although most skin lesions (73%) in a study by Rahier et al8 were psoriasiform, eczematiform lesions (38%) were the most frequent in our case, followed by psoriasiform lesions (28%). The remaining 34% of skin lesions could not be clearly assigned to one or other of these 2 categories and were as follows: acneiform eruptions, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, xerosis cutis, and alopecia areata. Others have also reported the occurrence of various types of skin lesions.10,21 The severity of the skin lesions ranged from mild forms such as acne, vitiligo, and lichenoid drug reactions to severe features, such as erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.21 In this study, the patient with linear immunoglobulin A dermatosis had the most severe problem and required discontinuation of the anti-TNF agent.

The psoriasiform lesions induced by anti-TNF medications occurred in the scalp, palmoplantar region, and extensor surface.8,22 Cullen et al23 reported that the most frequent clinical presentation of psoriasis occurring during treatment with anti-TNF agents was palmoplantar and scalp in location. However, in this study, the most frequently affected areas in 13 patients with psoriasiform lesions were the scalp (n = 9, 69.2%), followed by the trunk (n = 5, 38.5%). Palmoplantar involvement occurred in 3 patients, which was similar to the rate seen in the GETAID cohort (23.1% versus 35%, respectively).8 Eczematous eruptions secondary to anti-TNF therapy were most commonly seen on the face and upper body.

According to our data on the cumulative probability of the incidence of skin lesions, the median interval between the introduction of anti-TNF agents and the occurrence of skin lesions was 13 months (Fig. 1), 13.5 months for infliximab, and 12 months for adalimumab. This was similar to the interval observed in the study by Rahier et al.8 Careful monitoring after introduction of anti-TNF agents could allow for quicker diagnosis and treatment or referral to a dermatology specialist.

Most patients responded well to the topical treatment, and discontinuation of treatment was only needed in 4 patients. This rate is consistent with the findings of Fidder et al.11 However, Cullen et al23 reported a lower response rate to topical therapy (41%) and a considerable frequency of switching to a second anti-TNF agent for dermatologic reasons (18%). This difference may be due to a different composition of the adverse skin lesions. Up to now, young age,11 female gender,11 and a personal history of atopic symptoms12 have been suggested as risk factors for adverse skin lesions, in addition to a personal or familial history of inflammatory skin diseases.8 However, female gender was only a risk factor in our univariate analysis (P = 0.046).

The most significant observation in our study was that the concomitant use of AZA/6 MP at the time of introducing anti-TNF agents decreased the risk of adverse skin lesions in both univariate (P = 0.008) and multivariate (P = 0.006) analysis. Moreover, the cumulative probability of the incidence of adverse skin lesion was the lowest in the group with concomitant use of AZA/6 MP at the start of the anti-TNF treatment. Interestingly, all patients who needed discontinuation of anti-TNF agents were receiving anti-TNF agents without AZA/6 MP at the start of the anti-TNF treatment.

Concomitant treatment with infliximab and AZA is recommended for the management of early CD because of superior rates of corticosteroid-free clinical remission and mucosal healing.24 However, the risk of lymphoma is a concern, although it is extremely low.25 As noted above, adverse skin effects associated with anti-TNF agents in patients with IBD occur soon after the start of anti-TNF use. Combination therapy with immunomodulators including AZA or 6 MP during the initial anti-TNF treatment might be beneficial in reducing anti-TNF–induced adverse skin reactions.

Our study had several limitations. First, it was not possible to establish that all skin lesions were associated with paradoxical immune reactions to the anti-TNF agent; mild adverse skin lesions may have been missed, so that the frequency of adverse skin lesions may have been underestimated. However, mild skin lesions may not be of clinical significance. Second, because the study was retrospective, there could have been biases due to unrecognized or unmeasured factors. Third, histologic confirmation was available for a limited number of skin lesions in this study. Although dermatologists at our center recommended skin biopsies to all of the patients with new-onset psoriasiform lesions, 4 of the 10 patients (40%) with new-onset lesions underwent skin biopsies, which was not lower than that reported in Rahier et al8 (16/85, 18.8%). Another 4 patients had mild psoriasiform dermatitis or lesions limited to the scalp, which responded well to topical agents with or without antihistamines. The remaining 2 patients were reluctant to undergo skin biopsies for aesthetic reasons.

In conclusion, various adverse skin lesions can occur during anti-TNF therapy in patients with IBD. Concomitant use of AZA/6 MP at the time of introducing the anti-TNF agent can decrease the occurrence of such skin lesions.

Acknowledgments

The results of this study were summarized as a poster at DDW 2014.

References

Author notes

Reprints: Kyung-Jo Kim, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, University of Ulsan College Of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, Songpa-gu, Seoul 138-736, Republic of Korea (e-mail: [email protected]).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

J. S. Soh and W. J. Yun contributed equally to this work.