-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Umberto Leone Roberti Maggiore, Simone Ferrero, Giorgia Mangili, Alice Bergamini, Annalisa Inversetti, Veronica Giorgione, Paola Viganò, Massimo Candiani, A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 22, Issue 1, January/February 2016, Pages 70–103, https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv045

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Traditionally, pregnancy was considered to have a positive effect on endometriosis and its painful symptoms due not only to blockage of ovulation preventing bleeding of endometriotic tissue but also to different metabolic, hormonal, immune and angiogenesis changes related to pregnancy. However, a growing literature is emerging on the role of endometriosis in affecting the development of pregnancy and its outcomes and also on the impact of pregnancy on endometriosis. The present article aims to underline the difficulty in diagnosing endometriotic lesions during pregnancy and discuss the options for the treatment of decidualized endometriosis in relation to imaging and symptomatology; to describe all the possible acute complications of pregnancy caused by pre-existing endometriosis and evaluate potential treatments of these complications; to assess whether endometriosis affects pregnancy outcome and hypothesize mechanisms to explain the underlying relationships.

This systematic review is based on material searched and obtained via Pubmed and Medline between January 1950 and March 2015. Peer-reviewed, English-language journal articles examining the impact of endometriosis on pregnancy and vice versa were included in this article.

Changes of the endometriotic lesions may occur during pregnancy caused by the modifications of the hormonal milieu, posing a clinical dilemma due to their atypical appearance. The management of these events is actually challenging as only few cases have been described and the review of available literature evidenced a lack of formal estimates of their incidence. Acute complications of endometriosis during pregnancy, such as spontaneous hemoperitoneum, bowel and ovarian complications, represent rare but life-threatening conditions that require, in most of the cases, surgical operations to be managed. Due to the unpredictability of these complications, no specific recommendation for additional interventions to the routinely monitoring of pregnancy of women with known history of endometriosis is advisable. Even if the results of the published studies are controversial, some evidence is suggestive of an association of endometriosis with spontaneous miscarriage, preterm birth and small for gestational age babies. A correlation of endometriosis with placenta previa (odds ratio from 1.67 to 15.1 according to various studies) has been demonstrated, possibly linked to the abnormal frequency and amplitude of uterine contractions observed in women affected. Finally, there is no evidence that prophylactic surgery would prevent the negative impact of endometriosis itself on pregnancy outcome.

Complications of endometriosis during pregnancy are rare and there is no evidence that the disease has a major detrimental effect on pregnancy outcome. Therefore, pregnant women with endometriosis can be reassured on the course of their pregnancies although the physicians should be aware of the potential increased risk of placenta previa. Current evidence does not support any modification of conventional monitoring of pregnancy in patients with endometriosis.

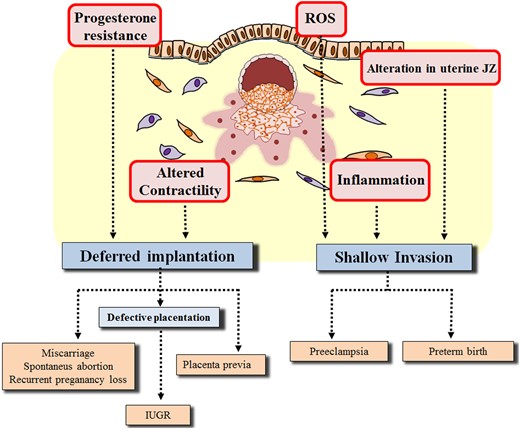

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue (stroma and glands) outside the uterus, which induces a local inflammatory response (Kennedy et al., 2005; De Nardi and Ferrari, 2011). It is an estrogen-dependent chronic condition that affects women of fertile age, and is associated with pelvic pain and infertility (Giudice, 2010). However, in recent years, evidence is emerging in support of a relevant impact of endometriosis not only in reducing fertility but also in affecting the pregnancy outcome. Different mechanisms including endocrine/inflammatory balance, bleeding from endometriotic implants, molecular and functional abnormalities of the eutopic endometrium, defective deep placentation and decidualization of the endometriotic tissue due to changes of the hormonal milieu that characterizes pregnancy are thought to be involved (Brosens et al., 2009, 2012a; Petraglia et al., 2012; Viganò et al., 2012).

Noteworthy, this rising concept is in contrast with the historical assumption that pregnancy may have a positive effect on endometriosis and its symptoms (Beecham, 1949; Kistner, 1959a, b) due to anovulation and amenorrhea preventing bleeding of endometriotic tissue but also to different metabolic, hormonal, immune and angiogenesis changes related to pregnancy (May and Becker, 2008; Taylor et al., 2009). Although the available literature is still too scanty and contradictory to draw definitive conclusions on the linkage between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes, a wide spectrum of obstetric events that originate either in the ectopic implants or in the uterus has been described.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to review the current body of knowledge on the impact of endometriosis on the outcome of pregnancy and, in detail, to:

underline the difficulty in diagnosing endometriotic lesions during pregnancy and discuss the options for the treatment of decidualized endometriosis in relation to imaging and symptomatology;

describe all the possible acute complications of pregnancy caused by pre-existing endometriosis and evaluate the potential treatments of these complications;

assess whether endometriosis affects pregnancy outcome and hypothesize mechanisms to explain the underlying relationships.

Methods

The PRISMA statement was used for reporting the Methods, Results and Discussion sections of the current review (Moher et al., 2009). No institutional review board approval was required because only published, de-identified data were analyzed. The search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria were specific for each of the three main aims of this systematic review and described below.

Literature search

General criteria

A systematic computerized search of the literature, from 1950 until March 2015 (last research 31 March 2015; the search was run every month since September 2014 until March 2015) was performed in two electronic databases (PubMed and MEDLINE) in order to identify relevant articles to be included for the purpose of this systematic review. All pertinent articles were examined and their reference lists were systematically reviewed in order to identify other studies for potential inclusion in this article.

Studies were reviewed by two independent reviewers (U.L.R.M. and S.F.) and discrepancies were resolved by consensus including a third author (P.V.). The reviewers were not blinded to the names of investigators or sources of publication. First, eligibility was assessed based on titles and abstracts. Full manuscripts were obtained for all selected studies and decision for final inclusion was made after detailed examination of the papers.

Specific criteria

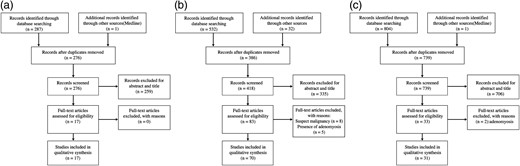

Three independent authors (A.I., A.B., V.G.) ran a specific literature search for each of the three main aims of this article (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table SI). The search included the following keywords and medical subjects heading terms, alone or in combination. The first search included the terms cancer, cyst, decidualized, decidual reaction, endometrioma, endometriosis, malignancy, pregnancy, tumor; the second the terms bladder, bowel, colorectal, complication, deep infiltrative, endometriosis, extrapelvic, fallopian tube, ovarian, pregnancy, rectovaginal endometriosis, urinary tract, uterosacral, vessels, uterus; the third the terms abruptio placentae, adverse pregnancy outcome, antepartum haemorrhage, caesarean delivery, endometriosis, gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction, miscarriage, placenta praevia, post-partum hemorrhage, pre-eclampsia, preterm labor, small for gestational age.

Flow chart of the search process for the purposes of the systematic review: decidualized endometriosis in the ovary and extra-ovarian sites (a), endometriosis complications during pregnancy (b), endometriosis and pregnancy outcomes (c).

Selection criteria

General criteria

Peer-reviewed, English-language journal articles that examined the impact of endometriosis on pregnancy and the impact of pregnancy on endometriosis were included in this systematic review. No limits on the age of participants, on type of pregnancy (single or multiple), on week of gestation of pregnancy or on the mode of conception (natural or assisted reproductive technology) were applied. Studies investigating the impact of adenomyosis (alone or associated with endometriosis) and of leiomyomas (associated with endometriosis) on pregnancy were excluded.

Specific criteria

For each of the three main aims of this article different type of studies were considered:

RCTs, prospective cohort studies, case–control studies, retrospective cohort studies, case series and case reports were screened where available;

case series and case reports were screened;

RCTs, prospective cohort studies, case–control studies, retrospective cohort studies and case series were screened where available.

Suspicion of malignant degeneration of decidualized endometriosis: imaging pattern and treatment issues

‘Deciduosis’ from decidualized endometriosis

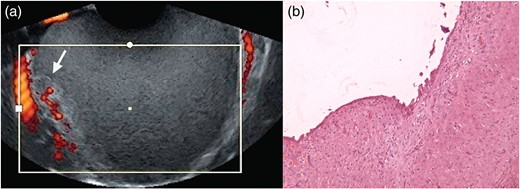

The condition in which groups of decidual cells reside outside the endometrium is termed ectopic decidua or ‘deciduosis’ and is a well-known phenomenon of pregnancy. Ectopic decidua is most commonly localized in the ovary, cervix, uterine serosa and the lamina propria of the salpinx while the peritoneal localization is uncommon. More specifically, the term ‘deciduosis’ is used to indicate two different entities (i) the phenomenon of metaplasia of the sub-coelomic pluripotent mesenchymal cells under the effect of progesterone reported very frequently in the ovary of term pregnancies and regressing post-partum within 4–6 weeks and (ii) the pregnancy-associated stromal decidualization of ectopic endometrium (endometriosis) that under progesterone action increases glandular epithelial secretion, stromal vascularity and edema (Barbieri et al., 2009; Calorbe et al., 2012). Decidualized endometriosis is characterized by typical sonographic, histological and molecular patterns (Fig. 2).

Ultrasonographic (a) and histologic (b, low-power magnification) patterns of a decidualized endometrioma (reproduced with permission from Mascilini et al., 2014 and Barbieri et al., 2009).

The sonographic pattern of decidualized ovarian endometriomas, in a proportion of cases, may mimic malignancy (Mascilini et al., 2014). As better described in depth later on, solid components can be easily recognized and the echogenicity of the cyst content is usually ground-glass or low level. The content usually consists of papillary projections with smooth rounded contour. Color Doppler analysis can detect multiple vascularization signals within the solid part with low resistance index.

Histologically, ‘deciduosis’ deriving from peritoneal metaplasia is usually found as small cell groups or single cell clusters under the mesothelium with polygonal and eosinophilic decidualized cells with various rates of vacuolar degeneration. The stroma may contain a myxoid deposit due to the vacuole rupture. Distended capillaries and numerous lymphocytes are typically found within the decidual foci (Bolat et al., 2012). Endometriotic lesions in pregnancy typically reveal a decidual reaction similar to that seen in the eutopic endometrium. The glands are usually atrophic resulting in fibrosis. Necrosis of the decidual cells, stromal myxoid change or edema and infiltration of lymphocytes may also be seen (Clement, 2007). The two entities are not easily histologically distinguishable.

The molecular aspects of decidualized endometriosis are under extensive investigation due to the potential implications for the disease development. Indeed, both eutopic and ectopic endometrial cells of women with endometriosis have compromised decidualization whose origins are probably multifactorial (Klemmt et al., 2006; Erikson et al., 2014). Main reason for this seems related to a differentiation defect in endometriotic stromal cells due to a resistance to the actions of progesterone, as progesterone is the key hormone involved in inducing the decidualization process. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis seems manifested by selective molecular abnormalities in the endometrium (Bulun et al., 2006; Burney et al., 2007). Overactivation of phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT, mitogen-activated protein kinase and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathways has also been hypothesized as causing aberrant decidualization of stromal cells from women with endometriosis (Erikson et al., 2014).

Amongst the interacting partners of progesterone receptor in the human endometrium are members of the forkhead box class O (FOXO) family of transcription factors. FOXO proteins, functioning downstream of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, are central to a diversity of cellular functions, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and resistance to oxidative stress (Kajihara et al., 2013). While normal decidualized stromal cells in response to activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway secrete abundant amounts of prolactin and express insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), ectopic endometrium has a blunted expression of the decidual markers prolactin and IGFBP-1 and of their upstream transcriptional regulator FOXO1. In particular, increased activation of PI3K/AKT pathway in endometriosis would promote translocation of FOXO1 to the cytoplasm and its modification for degradation (Yin et al., 2012). Further investigations are however needed to completely clarify these mechanisms. Notably, this compromised decidualization of ectopic lesions might not only promote their proliferation and/or survival but may also reflect their limited differentiation capacity (Erikson et al., 2014).

Decidualized ovarian endometriosis in pregnancy: diagnosis

Ovarian endometrioma represents a common finding in women affected by endometriosis, with an estimated prevalence of 30–40% (Redwine, 1999; Vercellini et al., 2006; Sanchez et al., 2014). Besides corpus luteal cysts, adnexal masses are detected in 0.5–1.2% of pregnancies: of these, 11% are endometriomas, while the reported rate of ovarian cancer is 1% (Bromley and Benacerraf, 1997; Leiserowitz et al., 2006). Of the latter, a proportion of about 51% is epithelial (both invasive and borderline) and 39% are germ cell tumors, mainly dysgerminomas and malignant teratomas, in line with the young age of pregnant woman. Ovarian endometriomas in pregnancy represents a peculiar entity, still debated both concerning diagnosis and treatment. During pregnancy, changes in the dimension and in the appearance of the endometriotic cyst have been described. Ueda and colleagues observed that during pregnancy size of the cysts decreased in 52% of the cases, went unchanged in 28%, and increased in 20% (Ueda et al., 2010). A more recent study reported that the number of endometriotic cysts was unchanged in 33% of the cases, increased in 8%, reduced in 13%, and in the remaining 46% no cyst could be detected (Benaglia et al., 2013). Different possible explanations for this phenomenon have been hypothesized. The cessation of menstrual cycles may be a factor potentially involved in the different endometrioma behavior during pregnancy. In addition, the peculiar histological characteristics of each endometrioma are likely related to this variability in modification during pregnancy, since endometrioma shrinkage only occurs in selected cases. It has been suggested that only those covered by endometrium, which is more prone to decidualization, may undergo shrinkage and even ‘vanishing’ (Benaglia et al., 2013). Furthermore, as mentioned above, pregnancy-related hormonal status may effectively lead to changes in the histologic, sonographic and molecular appearance referred as ‘decidualization’, which may in some cases resemble malignant ovarian tumors, potentially leading to an unnecessary surgical intervention. Formal assessment of the frequency of this phenomenon is lacking, and on the basis of indirect evidence supporting highly variable estimations, no definitive conclusion can be drawn (Ueda et al., 2010; Benaglia et al., 2013). Benaglia and coworkers conducted a study in order to assess modifications in number and size of ovarian endometriomas before and after pregnancy in 24 women who underwent IVF procedures. Forty endometriomas were identified and no sign of decidualization of the ovarian cysts was detected (Benaglia et al., 2013). Another study aimed at clarifying the frequency of pregnancies complicated by ovarian endometriosis and to investigate the size change and outcome of ovarian endometriosis during pregnancy. Twenty-four women carrying 25 endometriomas were included in this study and signs of decidualization were seen in 3 cases (12%). However, ovarian endometriosis in pregnancy is a rare condition with an estimated frequency of about 0.05–0.5% (Bromley and Benacerraf, 1997; Leiserowitz et al., 2006; Ueda et al., 2010) and literature on decidualized ovarian endometrioma mainly consists of case reports of three or fewer patients (Table I). Some larger studies have been recently published to define its peculiar sonographic appearance (Groszmann et al., 2014; Mascilini et al., 2014). As borderline tumors and cystadenofibromas, decidualized endometriomas are difficult to classify since they show sonographic characteristics common to both malignant and benign adnexal masses. It is likely that an under-diagnosis of such a transformation should be considered in explaining the rarity of this event because the ovaries are not routinely evaluated during obstetric ultrasound. Another possible explanation is the variability in levels and response to steroid hormones among pregnant women.

Ovarian decidualized endometriosis during pregnancy: cases reported in literature.

| Author, year . | Cases (n) . | Age [range] . | History of endometriosis . | Pain . | CA125 (U/ml) . | Laterality . | Size, mm [range] . | Intracystic papillae . | Solid part, mm . | Blood flow . | Septa . | MRI . | Surgery, type . | Surgery, GA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyakoshi et al. (1998) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 20 |

| Tanaka et al. (2002) | 1 | 27 | − | − | 103 | Unilateral | 120 × 80 × 70 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Fruscella et al. (2004) | 1 | 39 | − | − | 76 | Unilateral | 55 (max diam) | + | 8 × 10 and 5 × 5 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 18 |

| Sammour et al. (2005) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 × 50 × 63 | + | 23 × 18 × 14 | + | − | − | Oophorectomy | 16 |

| 1 | 36 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 37 × 27 × 25 | + | 15 × 20 × 25 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 15 | |

| Guerriero et al. (2005) | 1 | 38 | − | − | 109 | Unilateral | 40 × 48 | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral oophorectomy | 37 (CS) |

| Iwamoto et al. (2006) | 1 | 31 | + | − | 28.3 | Unilateral | 75 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 22 |

| Asch and Levine (2007) | 1 | Unilateral | NT | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral cystectomy | After delivery | ||||

| Poder et al. (2008) | 1 | 34 | + | − | 24 | Unilateral | 62 | + | + | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 38 (CS) |

| Machida et al. (2008) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 119 | Unilateral | 80 × 50 | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 |

| 41 | − | − | 220 | Unilateral | 160 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Oophorectomy | 14 | ||

| 24 | − | − | 34 | Bilateral | 50 | + | NR | NR | − | + | Cystectomy | 14 | ||

| Yoshida et al. (2008) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 × 53 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 14 |

| 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 74 × 48 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 | |

| Takeuchi et al. (2008) | 5 | 28 [20–32] | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 58 [40–90] | + | 20 mm (max) | NR§ | − | + | In 1 case | NR |

| Barbieri et al. (2009) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 30 | Unilateral | 66 × 44 | + | 20 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | |

| 36 | − | + | 159 | Bilateral | 85 × 63/50 × 30 | + | 27 × 14/7 × 7 | + | − | − | None | |||

| 39 | + | − | 85 | Unilateral | 38 × 14 | + | 19 × 12 | + | − | − | None | |||

| Sayasneh et al. (2012) | 1 | 35 | + | − | 89* | Unilateral | 31 × 40 × 5 × 40.5 | + | 15 | + | − | − | None | |

| Tazegül et al. (2013) | 1 | 32 | − | + (12 weeks) | 220 | Unilateral | 65 × 57 | + | 8 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Proulx and Levine (2014) | 1 | 30 | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | None | |

| Mascilini et al. (2014) | 18 | 34 [20–43] | 3 (17%) | 61 [12–285]** | 3(17%) Bilateral | 66 [41–121] | +17 (94%) | +17 (94%) | +16 (94%) | +7 (39%) | − | In 13 cases (72%) | ||

| Groszmann et al. (2014) | 17 | 29 [22–43] | NR | NR | 5 (29%) Bilateral | [30–270] | NR | +14 (64%) | +12 (55%) | +8 (36%) | − | In 8 cases (47%) |

| Author, year . | Cases (n) . | Age [range] . | History of endometriosis . | Pain . | CA125 (U/ml) . | Laterality . | Size, mm [range] . | Intracystic papillae . | Solid part, mm . | Blood flow . | Septa . | MRI . | Surgery, type . | Surgery, GA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyakoshi et al. (1998) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 20 |

| Tanaka et al. (2002) | 1 | 27 | − | − | 103 | Unilateral | 120 × 80 × 70 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Fruscella et al. (2004) | 1 | 39 | − | − | 76 | Unilateral | 55 (max diam) | + | 8 × 10 and 5 × 5 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 18 |

| Sammour et al. (2005) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 × 50 × 63 | + | 23 × 18 × 14 | + | − | − | Oophorectomy | 16 |

| 1 | 36 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 37 × 27 × 25 | + | 15 × 20 × 25 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 15 | |

| Guerriero et al. (2005) | 1 | 38 | − | − | 109 | Unilateral | 40 × 48 | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral oophorectomy | 37 (CS) |

| Iwamoto et al. (2006) | 1 | 31 | + | − | 28.3 | Unilateral | 75 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 22 |

| Asch and Levine (2007) | 1 | Unilateral | NT | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral cystectomy | After delivery | ||||

| Poder et al. (2008) | 1 | 34 | + | − | 24 | Unilateral | 62 | + | + | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 38 (CS) |

| Machida et al. (2008) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 119 | Unilateral | 80 × 50 | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 |

| 41 | − | − | 220 | Unilateral | 160 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Oophorectomy | 14 | ||

| 24 | − | − | 34 | Bilateral | 50 | + | NR | NR | − | + | Cystectomy | 14 | ||

| Yoshida et al. (2008) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 × 53 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 14 |

| 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 74 × 48 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 | |

| Takeuchi et al. (2008) | 5 | 28 [20–32] | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 58 [40–90] | + | 20 mm (max) | NR§ | − | + | In 1 case | NR |

| Barbieri et al. (2009) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 30 | Unilateral | 66 × 44 | + | 20 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | |

| 36 | − | + | 159 | Bilateral | 85 × 63/50 × 30 | + | 27 × 14/7 × 7 | + | − | − | None | |||

| 39 | + | − | 85 | Unilateral | 38 × 14 | + | 19 × 12 | + | − | − | None | |||

| Sayasneh et al. (2012) | 1 | 35 | + | − | 89* | Unilateral | 31 × 40 × 5 × 40.5 | + | 15 | + | − | − | None | |

| Tazegül et al. (2013) | 1 | 32 | − | + (12 weeks) | 220 | Unilateral | 65 × 57 | + | 8 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Proulx and Levine (2014) | 1 | 30 | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | None | |

| Mascilini et al. (2014) | 18 | 34 [20–43] | 3 (17%) | 61 [12–285]** | 3(17%) Bilateral | 66 [41–121] | +17 (94%) | +17 (94%) | +16 (94%) | +7 (39%) | − | In 13 cases (72%) | ||

| Groszmann et al. (2014) | 17 | 29 [22–43] | NR | NR | 5 (29%) Bilateral | [30–270] | NR | +14 (64%) | +12 (55%) | +8 (36%) | − | In 8 cases (47%) |

NR, not reported; +, present; −, absent; CS, Cesarean section; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; GA, gestational age.

*CA125 was measured prior to conception and not measured again.

**Available for nine women.

§Ultrasound (US) scan parameters not reported.

Ovarian decidualized endometriosis during pregnancy: cases reported in literature.

| Author, year . | Cases (n) . | Age [range] . | History of endometriosis . | Pain . | CA125 (U/ml) . | Laterality . | Size, mm [range] . | Intracystic papillae . | Solid part, mm . | Blood flow . | Septa . | MRI . | Surgery, type . | Surgery, GA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyakoshi et al. (1998) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 20 |

| Tanaka et al. (2002) | 1 | 27 | − | − | 103 | Unilateral | 120 × 80 × 70 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Fruscella et al. (2004) | 1 | 39 | − | − | 76 | Unilateral | 55 (max diam) | + | 8 × 10 and 5 × 5 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 18 |

| Sammour et al. (2005) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 × 50 × 63 | + | 23 × 18 × 14 | + | − | − | Oophorectomy | 16 |

| 1 | 36 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 37 × 27 × 25 | + | 15 × 20 × 25 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 15 | |

| Guerriero et al. (2005) | 1 | 38 | − | − | 109 | Unilateral | 40 × 48 | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral oophorectomy | 37 (CS) |

| Iwamoto et al. (2006) | 1 | 31 | + | − | 28.3 | Unilateral | 75 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 22 |

| Asch and Levine (2007) | 1 | Unilateral | NT | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral cystectomy | After delivery | ||||

| Poder et al. (2008) | 1 | 34 | + | − | 24 | Unilateral | 62 | + | + | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 38 (CS) |

| Machida et al. (2008) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 119 | Unilateral | 80 × 50 | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 |

| 41 | − | − | 220 | Unilateral | 160 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Oophorectomy | 14 | ||

| 24 | − | − | 34 | Bilateral | 50 | + | NR | NR | − | + | Cystectomy | 14 | ||

| Yoshida et al. (2008) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 × 53 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 14 |

| 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 74 × 48 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 | |

| Takeuchi et al. (2008) | 5 | 28 [20–32] | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 58 [40–90] | + | 20 mm (max) | NR§ | − | + | In 1 case | NR |

| Barbieri et al. (2009) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 30 | Unilateral | 66 × 44 | + | 20 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | |

| 36 | − | + | 159 | Bilateral | 85 × 63/50 × 30 | + | 27 × 14/7 × 7 | + | − | − | None | |||

| 39 | + | − | 85 | Unilateral | 38 × 14 | + | 19 × 12 | + | − | − | None | |||

| Sayasneh et al. (2012) | 1 | 35 | + | − | 89* | Unilateral | 31 × 40 × 5 × 40.5 | + | 15 | + | − | − | None | |

| Tazegül et al. (2013) | 1 | 32 | − | + (12 weeks) | 220 | Unilateral | 65 × 57 | + | 8 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Proulx and Levine (2014) | 1 | 30 | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | None | |

| Mascilini et al. (2014) | 18 | 34 [20–43] | 3 (17%) | 61 [12–285]** | 3(17%) Bilateral | 66 [41–121] | +17 (94%) | +17 (94%) | +16 (94%) | +7 (39%) | − | In 13 cases (72%) | ||

| Groszmann et al. (2014) | 17 | 29 [22–43] | NR | NR | 5 (29%) Bilateral | [30–270] | NR | +14 (64%) | +12 (55%) | +8 (36%) | − | In 8 cases (47%) |

| Author, year . | Cases (n) . | Age [range] . | History of endometriosis . | Pain . | CA125 (U/ml) . | Laterality . | Size, mm [range] . | Intracystic papillae . | Solid part, mm . | Blood flow . | Septa . | MRI . | Surgery, type . | Surgery, GA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyakoshi et al. (1998) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 20 |

| Tanaka et al. (2002) | 1 | 27 | − | − | 103 | Unilateral | 120 × 80 × 70 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Fruscella et al. (2004) | 1 | 39 | − | − | 76 | Unilateral | 55 (max diam) | + | 8 × 10 and 5 × 5 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 18 |

| Sammour et al. (2005) | 1 | 28 | + | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 × 50 × 63 | + | 23 × 18 × 14 | + | − | − | Oophorectomy | 16 |

| 1 | 36 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 37 × 27 × 25 | + | 15 × 20 × 25 | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 15 | |

| Guerriero et al. (2005) | 1 | 38 | − | − | 109 | Unilateral | 40 × 48 | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral oophorectomy | 37 (CS) |

| Iwamoto et al. (2006) | 1 | 31 | + | − | 28.3 | Unilateral | 75 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 22 |

| Asch and Levine (2007) | 1 | Unilateral | NT | + | NR | + | − | − | Bilateral cystectomy | After delivery | ||||

| Poder et al. (2008) | 1 | 34 | + | − | 24 | Unilateral | 62 | + | + | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 38 (CS) |

| Machida et al. (2008) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 119 | Unilateral | 80 × 50 | + | NR | + | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 |

| 41 | − | − | 220 | Unilateral | 160 | + | NR | NR | + | + | Oophorectomy | 14 | ||

| 24 | − | − | 34 | Bilateral | 50 | + | NR | NR | − | + | Cystectomy | 14 | ||

| Yoshida et al. (2008) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 85 × 53 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 14 |

| 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Unilateral | 74 × 48 | + | NR | − | − | + | Oophorectomy | 19 | |

| Takeuchi et al. (2008) | 5 | 28 [20–32] | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 58 [40–90] | + | 20 mm (max) | NR§ | − | + | In 1 case | NR |

| Barbieri et al. (2009) | 3 | 32 | − | − | 30 | Unilateral | 66 × 44 | + | 20 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | |

| 36 | − | + | 159 | Bilateral | 85 × 63/50 × 30 | + | 27 × 14/7 × 7 | + | − | − | None | |||

| 39 | + | − | 85 | Unilateral | 38 × 14 | + | 19 × 12 | + | − | − | None | |||

| Sayasneh et al. (2012) | 1 | 35 | + | − | 89* | Unilateral | 31 × 40 × 5 × 40.5 | + | 15 | + | − | − | None | |

| Tazegül et al. (2013) | 1 | 32 | − | + (12 weeks) | 220 | Unilateral | 65 × 57 | + | 8 × 14 | + | − | − | Cystectomy | 12 |

| Proulx and Levine (2014) | 1 | 30 | NR | − | NR | Unilateral | 40 (max diam) | + | NR | + | − | + | None | |

| Mascilini et al. (2014) | 18 | 34 [20–43] | 3 (17%) | 61 [12–285]** | 3(17%) Bilateral | 66 [41–121] | +17 (94%) | +17 (94%) | +16 (94%) | +7 (39%) | − | In 13 cases (72%) | ||

| Groszmann et al. (2014) | 17 | 29 [22–43] | NR | NR | 5 (29%) Bilateral | [30–270] | NR | +14 (64%) | +12 (55%) | +8 (36%) | − | In 8 cases (47%) |

NR, not reported; +, present; −, absent; CS, Cesarean section; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; GA, gestational age.

*CA125 was measured prior to conception and not measured again.

**Available for nine women.

§Ultrasound (US) scan parameters not reported.

The literature review allowed us to identify only 17 studies, reporting a total of 60 cases of ovarian decidualized endometriomas in pregnancy. Table I summarizes the main characteristics of the identified published cases.

Transvaginal sonography is the gold standard imaging method for the diagnosis of ovarian endometriomas (Barbieri et al., 2009; Mascilini et al., 2014). A typical sonographic appearance has been documented in up to 95% of cases (Patel et al., 1999; Barbieri et al., 2009), consisting of a round shaped cystic aspect, a minimum diameter of 10 mm, thick walls, regular margins, homogeneous low echogenic fluid content, scattered internal echoes and absence of papillae. However, in 5% of cases, an atypical aspect is detected, which includes anechoic content, solid appearance, and presence of punctuate echogenic foci within the cystic wall. Noteworthy is the fact that the performance of ultrasonography in terms of sensitivity and specificity is much lower during pregnancy (Alcázar et al., 2003; Barbieri et al., 2009). In addition, the potential decidualization of ovarian endometriomas leads to serious diagnostic challenges (Patel et al., 1999; Eskenazi et al., 2001; Alcázar et al., 2003) (Table I). Even considering all these studies, it is still difficult to define clear guidelines for the diagnostic management of such cases. A retrospective study including 18 pregnant patients was the first specifically aimed at describing the ultrasound characteristics of decidualized endometriomas according to the IOTA (International Ovarian Tumour Analysis) terminology (Mascilini et al., 2014). The main strength of this study was the standardized terminology used, although both the small sample size and the retrospective design have limited its value. Typically, a decidualized endometrioma appears as a uni- or multilocular cystic mass containing rounded vascularized papillary projections with smooth contour and with a ground glass or low-level echogenicity cystic content (Fig. 2). Papillations have been detected in all cases reported in literature (Table I). Their presence is relevant since papillary projections are a common sign of malignancy, present both in borderline tumors and in the malignant degeneration of endometriotic cysts (Granberg et al., 1989; Fruscella et al., 2004; Valentin et al., 2006; Testa et al., 2011). The possibility of differentiating malignant papillations from those of decidualized endometriomas would be crucial to avoid unnecessary surgery during pregnancy. As mentioned, the different round-shaped sonography appearance typically observed in benign papillations of decidualized endometriomas is the only distinguishing sign while papillary projections usually have an irregular surface in borderline malignancies.

As reported in Table I, the majority of cases showed an increased blood flow at color Doppler sonography, which therefore cannot be considered reliable in distinguishing a benign decidualized endometrioma from a malignant adnexal mass. Contrary to malignant tumors, the presence of septations was uncommon and their absence could be considered a reassuring sign. The absence of growth in these patients, followed up with serial sonographic evaluations, might be considered another reassuring sign, even if the follow-up sonographic examination throughout pregnancy was not available for all cases. In none of the cases was free pelvic fluid detected during ultrasonography. CA125 levels are not diagnostic in these patients, since it is physiologically elevated during pregnancy (Aslam et al., 2000). However, some authors have suggested a potential diagnostic role for serial CA125 measures or when levels are >1000 U/ml in the second trimester or beyond (Goh et al., 2014). Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) levels have been found to be significantly lower in pregnant women compared with their premenopausal counterparts and rarely increased in patients with ovarian endometriotic cysts (Huhtinen et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2012). Therefore, the role of a combined assessment of CA125 and HE4 for the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant adnexal tumors in pregnancy should be further elucidated in future investigations.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without gadolinium is considered safe in pregnancy and can be useful in evaluating sonographically undetermined adnexal lesions (Adusumili et al., 2006; Goh et al., 2014; Morisawa et al., 2014). Although no well-controlled human studies have been conducted to evaluate the teratogenic effect of gadolinium in pregnant women, no harmful effects have been reported for human fetuses exposed to gadolinium in utero. Different studies have demonstrated that the fetus can excrete, swallow, and reabsorb gadolinium into the gastrointestinal tract, which persists in the amniotic fluid (Mettler et al., 2008). Therefore, in clinical practice, it is wise to consider the use of gadolinium-based contrast media in pregnant women only when the benefit to the mother overwhelmingly outweighs the theoretic risks to the fetus (Sundgren and Leander, 2011; Wang et al., 2012). MRI was performed in 35 cases, 23 of whom were included in two studies assessing the usefulness of this technique in diagnosing decidualized endometriomas during pregnancy (Takeuchi et al., 2008; Morisawa et al., 2014). These studies provided evidence that the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was significantly higher for decidualized endometrial tissues as compared with malignant ovarian tumors, probably due to the edematous vascularized nature of endometrial tissue with abundant cytoplasm of stromal cells. Takeuchi et al. (2008) have evaluated the MRI features of 5 decidualized endometriomas. In 3 cases, diffusion weighted images were obtained, measuring ADC of 10 decidualized mural nodules of 3 endometriomas and these were compared with values from 7 ovarian cancers. The mean ADC of the decidualized mural nodules was 2.10 ± 0.32 × 10−3 versus 1.05 ± 0.13 × 10−3 mm2/s for the malignant ovarian cyst mural nodules (P < 0.001) (Takeuchi et al., 2008). In a more recent study by Morisawa et al. (2014), the authors retrospectively investigated the MRI findings of 18 decidualized endometriotic cysts and 24 ovarian cancers, considering height, signal intensity of the solid component on T2-diffusion weighted imaging, ADC of the solid component, size of the lesion, and signal intensity of the intracystic fluid on T1-weighted imaging. The ADC values of the intracystic decidualized solid component and of the cancer group were 1.77 × 10−3 mm2/s and 1.13 × 10−3 mm2/s, respectively (P < 0.0001). Another difference between the two entities was found in the signal of the intracystic fluid on T1-weighted imaging (higher in decidualized endometriotic cysts) as a possible result of the repeated intracystic bleeding. A lower signal intensity of the intracystic fluid during malignant transformation of the endometriotic cysts has already been described (Tanaka et al., 2000, 2010). Overall, in the presence of an endometrioma with prominent hyperintense mural nodules on T2-weighted images, the suspicion of a decidualized endometrioma should be high, but close follow-up should be provided to exclude the possibility of a malignant transformation. ADC measurement was suggested as an additional tool to help in the diagnosis (Takeuchi et al., 2008).

Decidualized ovarian endometriosis in pregnancy: treatment

The management of adnexal masses in pregnancy represents an actual dilemma between expectant management and surgical intervention. This might lead to an unnecessary removal of a benign mass on one hand, and to the conservative observation of a malignant condition on the other. Decision on surgical intervention should in any case undergo multidisciplinary discussion, balancing the level of malignant suspicion, gestational age, and fetal and maternal risks. Among all cases reported in the literature, only 19 were managed expectantly, more frequently for the most recently published cases (Table I). Probably, the increasing number of decidualized endometriomas mimicking ovarian malignancies published in these last years has contributed to moving clinicians toward a more conservative approach. All other cases underwent either cystectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy. Unfortunately, the detailed description of surgical procedures and their timing were not available for all cases.

Of note, pregnancy outcome in those patients who underwent surgery has been reported to be uneventful except for one, who suffered preterm rupture of membranes on the day of laparotomy at the 19th gestational week (Machida et al., 2008). However, surgery-related risks are reported to increase after 23 weeks' gestation, also considering that the enlarged uterus might represent a technical problem for surgeons (Whitecar et al., 1999; Usui et al., 2000; Barbieri et al., 2009). If the decision on surgical approach presents in the late third trimester, surgery should be postponed until after or at the time of delivery (Palanivelu et al., 2007).

Surprisingly, all patients underwent laparotomy (Table I) even though laparoscopy has been reported to be a safe approach during pregnancy, provided it is performed by an experienced surgeon (Palanivelu et al., 2007; Goh et al., 2014).

Decidualized endometriosis in extra-ovarian sites

Extra-ovarian endometriosis involves several sites, most commonly the peritoneum, bladder, bowel, diaphragm, pleura, lungs, breast and the skin, either intact or following surgery (scars, episiotomy). Endometriotic implants in these sites undergo changes under the influence of pregnancy-related hormones, becoming hypertrophic or gaining features of decidualization. Given its rarity, such a condition might be misdiagnosed as a malignant disease (Bergqvist, 1993; Nogales et al., 1993).

Peritoneal deciduosis in pregnancy mimicking carcinomatosis have been reported (Adhikari and Shen, 2013). Conversely, no case of peritoneal decidualized endometriosis in pregnancy has been described, despite the peritoneal surface being a common site for endometriosis localization. Tables II–IV summarizes all cases of extraovarian decidualized endometriosis (cutaneous, vesical and pulmonary) reported in the literature.

Decidualized extraovarian endometriosis of the skin, cases reported in literature.

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Staining . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellegrini (1982) | 1 | 30 | Cesarean scar | − | None | NR | NR | Excision during CS | NR |

| Nogales et al. (1993) | 1 | 25 | Cesarean scar | − | Cyclic pain and nodule starting 1 year previously. | + | Vimentin + α1 antitrypsin + Keratin − | Danazol until pregnancy Local Anti-inflammatory therapy Excision at CS | AW |

| Skidmore et al. (1996) | 1 | 40 | Umbilicus | + | Umbilical nodule 1 year previously, increasing in size Cyclic enlargement, cramping and bleeding during menstrual period in the past 5 years | − | NR | Excision during CS | Recurrence a few months after excision |

| Fair et al. (2000) | 2 | 21 | Vulvar | NR | Vulvar nodule, not noticed before pregnancy | + | Vimentin + Ki67+ PAS + | Excision | NR |

| 27 | Umbilicus | − | Umbilical nodule firstly noticed during the current pregnancy | + | NR | Excision | NR | ||

| El-Gohary et al. (2009) | 1 | 24 | Cesarean scar | NR | Lesion noted 2 years before No cyclic pain No cyclic enlargement | + | CD10+ ER − Calretinin + | NR | NR |

| Val-Bernal et al. (2011) | 1 | 36 | Cesarean scar | NR | Noted 2 years before | − | CK8+, hPL +, CD10+ Epithelial membrane antigen −, placental alkaline phosphatase −, CK 5/6 −, calretinin − | Excision | AW |

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Staining . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellegrini (1982) | 1 | 30 | Cesarean scar | − | None | NR | NR | Excision during CS | NR |

| Nogales et al. (1993) | 1 | 25 | Cesarean scar | − | Cyclic pain and nodule starting 1 year previously. | + | Vimentin + α1 antitrypsin + Keratin − | Danazol until pregnancy Local Anti-inflammatory therapy Excision at CS | AW |

| Skidmore et al. (1996) | 1 | 40 | Umbilicus | + | Umbilical nodule 1 year previously, increasing in size Cyclic enlargement, cramping and bleeding during menstrual period in the past 5 years | − | NR | Excision during CS | Recurrence a few months after excision |

| Fair et al. (2000) | 2 | 21 | Vulvar | NR | Vulvar nodule, not noticed before pregnancy | + | Vimentin + Ki67+ PAS + | Excision | NR |

| 27 | Umbilicus | − | Umbilical nodule firstly noticed during the current pregnancy | + | NR | Excision | NR | ||

| El-Gohary et al. (2009) | 1 | 24 | Cesarean scar | NR | Lesion noted 2 years before No cyclic pain No cyclic enlargement | + | CD10+ ER − Calretinin + | NR | NR |

| Val-Bernal et al. (2011) | 1 | 36 | Cesarean scar | NR | Noted 2 years before | − | CK8+, hPL +, CD10+ Epithelial membrane antigen −, placental alkaline phosphatase −, CK 5/6 −, calretinin − | Excision | AW |

AW, alive and well; CS, Cesarean section; ER, estrogen receptor; hPL, human placental lactogen; PAS, periodic acid Schiff.

Decidualized extraovarian endometriosis of the skin, cases reported in literature.

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Staining . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellegrini (1982) | 1 | 30 | Cesarean scar | − | None | NR | NR | Excision during CS | NR |

| Nogales et al. (1993) | 1 | 25 | Cesarean scar | − | Cyclic pain and nodule starting 1 year previously. | + | Vimentin + α1 antitrypsin + Keratin − | Danazol until pregnancy Local Anti-inflammatory therapy Excision at CS | AW |

| Skidmore et al. (1996) | 1 | 40 | Umbilicus | + | Umbilical nodule 1 year previously, increasing in size Cyclic enlargement, cramping and bleeding during menstrual period in the past 5 years | − | NR | Excision during CS | Recurrence a few months after excision |

| Fair et al. (2000) | 2 | 21 | Vulvar | NR | Vulvar nodule, not noticed before pregnancy | + | Vimentin + Ki67+ PAS + | Excision | NR |

| 27 | Umbilicus | − | Umbilical nodule firstly noticed during the current pregnancy | + | NR | Excision | NR | ||

| El-Gohary et al. (2009) | 1 | 24 | Cesarean scar | NR | Lesion noted 2 years before No cyclic pain No cyclic enlargement | + | CD10+ ER − Calretinin + | NR | NR |

| Val-Bernal et al. (2011) | 1 | 36 | Cesarean scar | NR | Noted 2 years before | − | CK8+, hPL +, CD10+ Epithelial membrane antigen −, placental alkaline phosphatase −, CK 5/6 −, calretinin − | Excision | AW |

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Staining . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellegrini (1982) | 1 | 30 | Cesarean scar | − | None | NR | NR | Excision during CS | NR |

| Nogales et al. (1993) | 1 | 25 | Cesarean scar | − | Cyclic pain and nodule starting 1 year previously. | + | Vimentin + α1 antitrypsin + Keratin − | Danazol until pregnancy Local Anti-inflammatory therapy Excision at CS | AW |

| Skidmore et al. (1996) | 1 | 40 | Umbilicus | + | Umbilical nodule 1 year previously, increasing in size Cyclic enlargement, cramping and bleeding during menstrual period in the past 5 years | − | NR | Excision during CS | Recurrence a few months after excision |

| Fair et al. (2000) | 2 | 21 | Vulvar | NR | Vulvar nodule, not noticed before pregnancy | + | Vimentin + Ki67+ PAS + | Excision | NR |

| 27 | Umbilicus | − | Umbilical nodule firstly noticed during the current pregnancy | + | NR | Excision | NR | ||

| El-Gohary et al. (2009) | 1 | 24 | Cesarean scar | NR | Lesion noted 2 years before No cyclic pain No cyclic enlargement | + | CD10+ ER − Calretinin + | NR | NR |

| Val-Bernal et al. (2011) | 1 | 36 | Cesarean scar | NR | Noted 2 years before | − | CK8+, hPL +, CD10+ Epithelial membrane antigen −, placental alkaline phosphatase −, CK 5/6 −, calretinin − | Excision | AW |

AW, alive and well; CS, Cesarean section; ER, estrogen receptor; hPL, human placental lactogen; PAS, periodic acid Schiff.

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Treatment . | Histological examination . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flieder et al. (1998) | 1 | 27 | Lung, bilaterally | – | Bilateral lung nodules slowly enlarging during the previous 2 years; Right pneumothorax at 28 weeks' gestation – shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain | + (slowly increasing during the previous 2 years) | Open lung biopsy Chest tube placement | Pulmonary deciduosis. Eosinophilic cells with granular and vacuolated eosinophilic and focally basophilic cytoplasm No endometrial glands | Unchanged after 5.5 years |

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Treatment . | Histological examination . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flieder et al. (1998) | 1 | 27 | Lung, bilaterally | – | Bilateral lung nodules slowly enlarging during the previous 2 years; Right pneumothorax at 28 weeks' gestation – shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain | + (slowly increasing during the previous 2 years) | Open lung biopsy Chest tube placement | Pulmonary deciduosis. Eosinophilic cells with granular and vacuolated eosinophilic and focally basophilic cytoplasm No endometrial glands | Unchanged after 5.5 years |

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Treatment . | Histological examination . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flieder et al. (1998) | 1 | 27 | Lung, bilaterally | – | Bilateral lung nodules slowly enlarging during the previous 2 years; Right pneumothorax at 28 weeks' gestation – shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain | + (slowly increasing during the previous 2 years) | Open lung biopsy Chest tube placement | Pulmonary deciduosis. Eosinophilic cells with granular and vacuolated eosinophilic and focally basophilic cytoplasm No endometrial glands | Unchanged after 5.5 years |

| Author, year . | No. of cases . | Age . | Site . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Treatment . | Histological examination . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flieder et al. (1998) | 1 | 27 | Lung, bilaterally | – | Bilateral lung nodules slowly enlarging during the previous 2 years; Right pneumothorax at 28 weeks' gestation – shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain | + (slowly increasing during the previous 2 years) | Open lung biopsy Chest tube placement | Pulmonary deciduosis. Eosinophilic cells with granular and vacuolated eosinophilic and focally basophilic cytoplasm No endometrial glands | Unchanged after 5.5 years |

| Author, year . | N . | Age . | GA . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Diagnosis . | Site . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chertin et al. (2007) | 1 | 36 | 23 | NR | Dysuria, frequency Catamenial exacerbation | + | US Cystoscopy | Right bladder wall | Cold cup biopsy during cystoscopy | − |

| Trpkov et al. (2009) | 1 | 25 | 16 | NR | None | NR | US Cystoscopy | Anterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Szopiński et al. (2009) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | Dysuria | + | US Cystoscopy | Posterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Lambrechts et al. (2011) | 1 | 29 | 19 | NR | Intermittent hematuria since 8 weeks | + | US MRI Cystoscopy | Junction of the urachal ligament and the bladder dome | Partial cystectomy | − |

| Faske et al. (2012) | 1 | 38 | 20 | NR | None | − | US Cystoscopy | Posterior wall of the bladder | Biopsy | − |

| Author, year . | N . | Age . | GA . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Diagnosis . | Site . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chertin et al. (2007) | 1 | 36 | 23 | NR | Dysuria, frequency Catamenial exacerbation | + | US Cystoscopy | Right bladder wall | Cold cup biopsy during cystoscopy | − |

| Trpkov et al. (2009) | 1 | 25 | 16 | NR | None | NR | US Cystoscopy | Anterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Szopiński et al. (2009) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | Dysuria | + | US Cystoscopy | Posterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Lambrechts et al. (2011) | 1 | 29 | 19 | NR | Intermittent hematuria since 8 weeks | + | US MRI Cystoscopy | Junction of the urachal ligament and the bladder dome | Partial cystectomy | − |

| Faske et al. (2012) | 1 | 38 | 20 | NR | None | − | US Cystoscopy | Posterior wall of the bladder | Biopsy | − |

US, ultrasonography.

| Author, year . | N . | Age . | GA . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Diagnosis . | Site . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chertin et al. (2007) | 1 | 36 | 23 | NR | Dysuria, frequency Catamenial exacerbation | + | US Cystoscopy | Right bladder wall | Cold cup biopsy during cystoscopy | − |

| Trpkov et al. (2009) | 1 | 25 | 16 | NR | None | NR | US Cystoscopy | Anterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Szopiński et al. (2009) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | Dysuria | + | US Cystoscopy | Posterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Lambrechts et al. (2011) | 1 | 29 | 19 | NR | Intermittent hematuria since 8 weeks | + | US MRI Cystoscopy | Junction of the urachal ligament and the bladder dome | Partial cystectomy | − |

| Faske et al. (2012) | 1 | 38 | 20 | NR | None | − | US Cystoscopy | Posterior wall of the bladder | Biopsy | − |

| Author, year . | N . | Age . | GA . | Abdominal endometriosis . | Symptoms . | Increased size during pregnancy . | Diagnosis . | Site . | Treatment . | Follow-up . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chertin et al. (2007) | 1 | 36 | 23 | NR | Dysuria, frequency Catamenial exacerbation | + | US Cystoscopy | Right bladder wall | Cold cup biopsy during cystoscopy | − |

| Trpkov et al. (2009) | 1 | 25 | 16 | NR | None | NR | US Cystoscopy | Anterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Szopiński et al. (2009) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | Dysuria | + | US Cystoscopy | Posterior bladder wall | Biopsy | − |

| Lambrechts et al. (2011) | 1 | 29 | 19 | NR | Intermittent hematuria since 8 weeks | + | US MRI Cystoscopy | Junction of the urachal ligament and the bladder dome | Partial cystectomy | − |

| Faske et al. (2012) | 1 | 38 | 20 | NR | None | − | US Cystoscopy | Posterior wall of the bladder | Biopsy | − |

US, ultrasonography.

Cutaneous decidualized endometriosis

Cutaneous decidualized endometriosis, cutaneous deciduosis, deciduoma or pseudotumoral deciduosis represents a rare, benign manifestation of endometriosis that may involve the skin or the subcutaneous tissue, both on an intact site or in relation to an abdominal surgical scar. Concurrent pelvic endometriotic implants are rarely present (Fair et al., 2000). It may represent a diagnostic challenge, since it can potentially be mistaken for malignancy due to its abnormal location and for the atypia of the decidual cells. A history of cyclical pain, the typical lesion enlargement occurring during pregnancy, the shape of the nodules with smooth rounded borders and their non-infiltrative nature may help for the diagnosis, even if a clinical-pathological analysis is required.

Decidualized endometriosis of the bladder

Bladder endometriosis is rare, reported in 1% of women with pelvic endometriosis (Shook and Nyberg, 1988). As for the other sites, the hormonally induced-decidualization of the lesion can cause its rapid growth, simulating a bladder tumor. Differential diagnoses include benign bladder polyp, bladder leiomyoma, bladder cancer and placenta percreta (Faske et al., 2012). In all cases described in the literature, the clinical assessment was performed using ultrasound and cystoscopy. In only one case, MRI was used as an additional diagnostic tool. Bladder decidualized endometriosis shares features common to both non-decidualized endometriosis and bladder malignancies. These lesions appear as a node covered by a small rim of hyperechogenic bladder wall, like benign endometriosis does. Common characteristics with bladder malignancy include the high vascularization on color Doppler analysis, feeding arterial vessels seen on MRI scans and the location most commonly found at the bladder dome. Conversely, benign endometriosis usually involves the vesicouterine pouch (Lambrechts et al., 2011). All cases reported have been treated successfully with no consequences on pregnancy outcome.

Decidualized pulmonary endometriosis

A single case of decidualized pulmonary endometriosis in pregnancy has been reported (Flieder et al., 1998) (Table III).

Complications of a pre-existing endometriosis during pregnancy

Several case reports of acute endometriosis-related complications occurring during pregnancy have been described. However, these complications are rarely reported and consequently underestimated, and they may represent life-threatening conditions for both the mother and the fetus. For this reason, physicians managing pregnancy of women with endometriosis should be aware of these insidious adverse events. Hence, in this section of the review, we offer the reader a complete overview of these complications and of their possible management (Tables V–VII).

Endometriosis-related complications involving bowel and pelvic vessels during pregnancy, cases reported in literature.

| . | Authors, years . | No. of cases . | Age (years) . | History of endometriosis . | Surgery before pregnancy (type, time before) . | Conception . | Presenting symptoms . | Site of complication . | Onset of complication (gestational week) . | Complication management during pregnancy . | Histological examination . | Pregnancy outcome, gestational week at delivery . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel | ||||||||||||

| Intestinal perforation | Clement (1977) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Sigmoid colon | 37 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 37 |

| Gini et al. (1981) | 1 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | Vaginal bleeding, AP | Appendix | 35 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Floberg et al. (1984) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Ovary, sigmoid colon | Immediate post-partum | LPT: OC, segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 41 | |

| Nakatani et al. (1987) | 1 | 25 | − | − | NR | N, V, AP | Appendix | 26 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, term | |

| Loverro et al. (1999) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP, hyperpyrexia | Sigmoid colon | 35 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Schweitzer et al. (2006) | 1 | 32 | − | − | A | N, AP, dyspnea | Sigmoid colon | 40 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 40 | |

| Faucheron et al. (2008) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | N, AP | Appendix | 27 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, term | |

| Beamish et al. (2010) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | Acute AP | Cecum | 3 days post-partum | LPT: segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 37 | |

| Pisanu et al. (2010) | 1 | 37 | + | OC, LOA, DTC, 5 years | NR | Lower AP | Rectum | 33 | LPT: Hartmann procedure, appendectomy | E+D | LB, 33 | |

| Lebastchi et al. (2013) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | Upper AP | Appendix | 31 | LPT: appendectomy, ileocecetomy | E+D | LB, 31 | |

| Nishikawa et al. (2013) | 1 | 38 | + | OC, 15 years | A | Upper AP, melena | Ileum | 28 | LPT: segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 33 | |

| Menzlova et al. (2014) | 1 | 32 | + | OC, 3 years | NR | Asymptomatic | Rectum | Immediate post-partum | Rectum repair | NR | LB, term | |

| Setúbal et al. (2014) | 3 | 36; 35; 34 | +; −: − | −; −; − | A; S; S | AP; AP; AP | Sigmoid colon; Rectosigmoid colon; Sigmoid colon | 28; 35; 16 | EX LPT during pregnancy and LPS hysterectomy, SO, OC, segmental bowel resection post-partum; LPT: Hartman procedure, appendectomy; LPT: Hartman procedure after EX LPT | E; E+D; E+D | LB, 37; LB, 35; LB, 39 | |

| Costa et al. (2014) | 1 | 32 | − | − | NR | AP | Rectum, sigmoid colon | 25 | LPS: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 41 | |

| Appendicitis | Lane (1960) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR |

| Tedeschi and Masand (1971) | 1 | 30 | − | − | NR | AP | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Finch and Lee (1974) | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Appendix | 28 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | ND, 29 | |

| Nielsen et al. (1983) | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | AP | Appendix | Term | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | NR, NR | |

| Silvestrini and Marcial (1995) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, N, V, diarrhea | Appendix | 21 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Stefanidis et al. (1999) | 1 | 27 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, V | Appendix | 20 | LPT: appendectomy | E | LB, 39 | |

| Perez et al. (2007) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, N, V | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | NR, NR | |

| Utero-ovarian vessels | ||||||||||||

| Vessel rupture | Inoue et al. (1992) | 1 | 37 | NR | NR | NR | AP | Uterus | 29 | EX LPT | NR | LB, 29 |

| Mizumoto et al. (1996) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | Upper AP | Uterus | 28 | EX LPT | E+D | ND, 29 | |

| Leung et al. (1998) | 1 | 35 | − | − | NR | AP | Uterus | 33 | EX LPT | NR | IUD, 33 | |

| Ismail and Shervington (1999) | 2 | NR | NR; NR | NR | NR | AP; AP | Uterus; uterus | 33; 2 weeks post-partum | EX LPT; EX LPT | E; E | NR, 33; NR, NR | |

| Aziz et al. (2004) | 1 | 30 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Parametrium | 20 | EX LPT: left SO | E+D | IUD, 20 | |

| O'Leary (2006) | 1 | 41 | + | DTC, 9 months | NR | Lower AP, hyperpyrexia | Parametrium | 11 days post-partum | EX LPT: subtotal hysterectomy, BSO | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Wu et al. (2007) | 1 | 31 | + | Bilateral OC, 5 years | A | Lower AP | Uterus | 33 (twins) | EX LPT | NR | LB, LB, 34 | |

| Kirkinen et al. (2007) | 1 | 37 | − | − | NR | Vaginal bleeding | Parametrium | 22 | Uterine artery embolization during pregnancy and EX LPT post-partum | E+D | LB, 24 | |

| Katorza et al. (2007) | 2 | 29; 32 | −;+ | −; OC, DTC, LOA, NR | A; A | Lower AP; lower AP | Uterus; Uterus | 25 (twins); 29 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | LB, LB, 28; LB, 29 | |

| Passos et al. (2008) | 2 | 30; 32 | +;+ | OC, LOA, NR; LOA, 2 years | NR; NR | NR; AP | Parametrium; Parametrium and uterus | 32 (twins); 31 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | LB, LB, 32; LB, 31 | |

| Bouet et al. (2009) | 1 | 32 | − | − | NR | Lower AP, dyspnea | Parametrium | 24 | Thoracic drainage, EX LPT: left SO | E+D | IUD, 24 | |

| Roche et al. (2008) | 1 | 43 | + | LPS, NR | A | Lower AP, hematemesis | Uterus, uteroovarian ligament | 33 (twins) | EX LPT: OC | NR | IUD, IUD, 34 | |

| Wada et al. (2009) | 1 | 31 | + | Bilateral OC, DTC, LOA, 4 months | S | Lower AP | Uterus | Immediate post-partum | EX LPT | NR | LB, 37 | |

| Zhang et al. (2009) | 2 | 38; 35 | +; + | Bilateral OC, LOA, NR; DTC, LOA, NR | A; A | AP; upper AP, hyperpyrexia | Uterus; Uterus | 29 (twins); 35 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | IUD, IUD, 29; LB, 35 | |

| Grunewald and Jördens (2010) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | AP | Sacro-uterine ligament | 27 | EX LPT | E | LB, 42 | |

| Gao et al. (2010) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Upper AP | Uterus | 2 days post-partum | LPS: LOA, left internal iliac artery ligation | E+D | LB, NR | |

| Urinary system | ||||||||||||

| Uroperitoneum | Chiodo et al. (2008) | 1 | 25 | + | LOA, OC, DTC, 2 years | NR | AP, hematuria | Sacro-uterine ligament with right ureter and uterine artery involvement | 31 | LPT: ligation of the right uterine artery and ureteroneocystostomy | E+D | LB, 31 |

| Leone Roberti Maggiore et al. (2015) | 1 | 30 | + | Transurethral nodule resection | A | AP | Bladder | 27 | LPT: bladder resection | E+D | LB, 27 | |

| Distorsion of renal system anatomy | Yaqub et al. (2008) | 1 | 25 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Renal area | 34 | LPT: removal of cyst by blunt dissection and clamping vascular pedicle | E | LB, 34 |

| Pezzuto et al. (2009) | 1 | 34 | + | − | NR | AP | Broad ligament | 35 | Ureteral stent | NR | NR, NR | |

| . | Authors, years . | No. of cases . | Age (years) . | History of endometriosis . | Surgery before pregnancy (type, time before) . | Conception . | Presenting symptoms . | Site of complication . | Onset of complication (gestational week) . | Complication management during pregnancy . | Histological examination . | Pregnancy outcome, gestational week at delivery . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel | ||||||||||||

| Intestinal perforation | Clement (1977) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Sigmoid colon | 37 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 37 |

| Gini et al. (1981) | 1 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | Vaginal bleeding, AP | Appendix | 35 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Floberg et al. (1984) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Ovary, sigmoid colon | Immediate post-partum | LPT: OC, segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 41 | |

| Nakatani et al. (1987) | 1 | 25 | − | − | NR | N, V, AP | Appendix | 26 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, term | |

| Loverro et al. (1999) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP, hyperpyrexia | Sigmoid colon | 35 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Schweitzer et al. (2006) | 1 | 32 | − | − | A | N, AP, dyspnea | Sigmoid colon | 40 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 40 | |

| Faucheron et al. (2008) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | N, AP | Appendix | 27 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, term | |

| Beamish et al. (2010) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | Acute AP | Cecum | 3 days post-partum | LPT: segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 37 | |

| Pisanu et al. (2010) | 1 | 37 | + | OC, LOA, DTC, 5 years | NR | Lower AP | Rectum | 33 | LPT: Hartmann procedure, appendectomy | E+D | LB, 33 | |

| Lebastchi et al. (2013) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | Upper AP | Appendix | 31 | LPT: appendectomy, ileocecetomy | E+D | LB, 31 | |

| Nishikawa et al. (2013) | 1 | 38 | + | OC, 15 years | A | Upper AP, melena | Ileum | 28 | LPT: segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 33 | |

| Menzlova et al. (2014) | 1 | 32 | + | OC, 3 years | NR | Asymptomatic | Rectum | Immediate post-partum | Rectum repair | NR | LB, term | |

| Setúbal et al. (2014) | 3 | 36; 35; 34 | +; −: − | −; −; − | A; S; S | AP; AP; AP | Sigmoid colon; Rectosigmoid colon; Sigmoid colon | 28; 35; 16 | EX LPT during pregnancy and LPS hysterectomy, SO, OC, segmental bowel resection post-partum; LPT: Hartman procedure, appendectomy; LPT: Hartman procedure after EX LPT | E; E+D; E+D | LB, 37; LB, 35; LB, 39 | |

| Costa et al. (2014) | 1 | 32 | − | − | NR | AP | Rectum, sigmoid colon | 25 | LPS: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 41 | |

| Appendicitis | Lane (1960) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR |

| Tedeschi and Masand (1971) | 1 | 30 | − | − | NR | AP | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Finch and Lee (1974) | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Appendix | 28 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | ND, 29 | |

| Nielsen et al. (1983) | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | AP | Appendix | Term | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | NR, NR | |

| Silvestrini and Marcial (1995) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, N, V, diarrhea | Appendix | 21 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Stefanidis et al. (1999) | 1 | 27 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, V | Appendix | 20 | LPT: appendectomy | E | LB, 39 | |

| Perez et al. (2007) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, N, V | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | NR, NR | |

| Utero-ovarian vessels | ||||||||||||

| Vessel rupture | Inoue et al. (1992) | 1 | 37 | NR | NR | NR | AP | Uterus | 29 | EX LPT | NR | LB, 29 |

| Mizumoto et al. (1996) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | Upper AP | Uterus | 28 | EX LPT | E+D | ND, 29 | |

| Leung et al. (1998) | 1 | 35 | − | − | NR | AP | Uterus | 33 | EX LPT | NR | IUD, 33 | |

| Ismail and Shervington (1999) | 2 | NR | NR; NR | NR | NR | AP; AP | Uterus; uterus | 33; 2 weeks post-partum | EX LPT; EX LPT | E; E | NR, 33; NR, NR | |

| Aziz et al. (2004) | 1 | 30 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Parametrium | 20 | EX LPT: left SO | E+D | IUD, 20 | |

| O'Leary (2006) | 1 | 41 | + | DTC, 9 months | NR | Lower AP, hyperpyrexia | Parametrium | 11 days post-partum | EX LPT: subtotal hysterectomy, BSO | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Wu et al. (2007) | 1 | 31 | + | Bilateral OC, 5 years | A | Lower AP | Uterus | 33 (twins) | EX LPT | NR | LB, LB, 34 | |

| Kirkinen et al. (2007) | 1 | 37 | − | − | NR | Vaginal bleeding | Parametrium | 22 | Uterine artery embolization during pregnancy and EX LPT post-partum | E+D | LB, 24 | |

| Katorza et al. (2007) | 2 | 29; 32 | −;+ | −; OC, DTC, LOA, NR | A; A | Lower AP; lower AP | Uterus; Uterus | 25 (twins); 29 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | LB, LB, 28; LB, 29 | |

| Passos et al. (2008) | 2 | 30; 32 | +;+ | OC, LOA, NR; LOA, 2 years | NR; NR | NR; AP | Parametrium; Parametrium and uterus | 32 (twins); 31 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | LB, LB, 32; LB, 31 | |

| Bouet et al. (2009) | 1 | 32 | − | − | NR | Lower AP, dyspnea | Parametrium | 24 | Thoracic drainage, EX LPT: left SO | E+D | IUD, 24 | |

| Roche et al. (2008) | 1 | 43 | + | LPS, NR | A | Lower AP, hematemesis | Uterus, uteroovarian ligament | 33 (twins) | EX LPT: OC | NR | IUD, IUD, 34 | |

| Wada et al. (2009) | 1 | 31 | + | Bilateral OC, DTC, LOA, 4 months | S | Lower AP | Uterus | Immediate post-partum | EX LPT | NR | LB, 37 | |

| Zhang et al. (2009) | 2 | 38; 35 | +; + | Bilateral OC, LOA, NR; DTC, LOA, NR | A; A | AP; upper AP, hyperpyrexia | Uterus; Uterus | 29 (twins); 35 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | IUD, IUD, 29; LB, 35 | |

| Grunewald and Jördens (2010) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | AP | Sacro-uterine ligament | 27 | EX LPT | E | LB, 42 | |

| Gao et al. (2010) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Upper AP | Uterus | 2 days post-partum | LPS: LOA, left internal iliac artery ligation | E+D | LB, NR | |

| Urinary system | ||||||||||||

| Uroperitoneum | Chiodo et al. (2008) | 1 | 25 | + | LOA, OC, DTC, 2 years | NR | AP, hematuria | Sacro-uterine ligament with right ureter and uterine artery involvement | 31 | LPT: ligation of the right uterine artery and ureteroneocystostomy | E+D | LB, 31 |

| Leone Roberti Maggiore et al. (2015) | 1 | 30 | + | Transurethral nodule resection | A | AP | Bladder | 27 | LPT: bladder resection | E+D | LB, 27 | |

| Distorsion of renal system anatomy | Yaqub et al. (2008) | 1 | 25 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Renal area | 34 | LPT: removal of cyst by blunt dissection and clamping vascular pedicle | E | LB, 34 |

| Pezzuto et al. (2009) | 1 | 34 | + | − | NR | AP | Broad ligament | 35 | Ureteral stent | NR | NR, NR | |

DTC, diathermocoagulation of endometriotic lesions; LOA, lysis of adhesions; OC, ovarian cystectomy; S, spontaneous; A, assisted reproductive technology (ART); AP, abdominal pain; N, nausea; V, vomiting; LPT, laparotomy; EX LPT, exploratory laparotomy; LPS, laparoscopy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; SO, salpingo-oophorectomy; E, endometriosis; D, decidual change; I, inflammation; LB, live birth; IUD, intrauterine death; ND, neonatal demise.

Endometriosis-related complications involving bowel and pelvic vessels during pregnancy, cases reported in literature.

| . | Authors, years . | No. of cases . | Age (years) . | History of endometriosis . | Surgery before pregnancy (type, time before) . | Conception . | Presenting symptoms . | Site of complication . | Onset of complication (gestational week) . | Complication management during pregnancy . | Histological examination . | Pregnancy outcome, gestational week at delivery . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel | ||||||||||||

| Intestinal perforation | Clement (1977) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Sigmoid colon | 37 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 37 |

| Gini et al. (1981) | 1 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | Vaginal bleeding, AP | Appendix | 35 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Floberg et al. (1984) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Ovary, sigmoid colon | Immediate post-partum | LPT: OC, segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 41 | |

| Nakatani et al. (1987) | 1 | 25 | − | − | NR | N, V, AP | Appendix | 26 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, term | |

| Loverro et al. (1999) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP, hyperpyrexia | Sigmoid colon | 35 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Schweitzer et al. (2006) | 1 | 32 | − | − | A | N, AP, dyspnea | Sigmoid colon | 40 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 40 | |

| Faucheron et al. (2008) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | N, AP | Appendix | 27 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, term | |

| Beamish et al. (2010) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | Acute AP | Cecum | 3 days post-partum | LPT: segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 37 | |

| Pisanu et al. (2010) | 1 | 37 | + | OC, LOA, DTC, 5 years | NR | Lower AP | Rectum | 33 | LPT: Hartmann procedure, appendectomy | E+D | LB, 33 | |

| Lebastchi et al. (2013) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | Upper AP | Appendix | 31 | LPT: appendectomy, ileocecetomy | E+D | LB, 31 | |

| Nishikawa et al. (2013) | 1 | 38 | + | OC, 15 years | A | Upper AP, melena | Ileum | 28 | LPT: segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 33 | |

| Menzlova et al. (2014) | 1 | 32 | + | OC, 3 years | NR | Asymptomatic | Rectum | Immediate post-partum | Rectum repair | NR | LB, term | |

| Setúbal et al. (2014) | 3 | 36; 35; 34 | +; −: − | −; −; − | A; S; S | AP; AP; AP | Sigmoid colon; Rectosigmoid colon; Sigmoid colon | 28; 35; 16 | EX LPT during pregnancy and LPS hysterectomy, SO, OC, segmental bowel resection post-partum; LPT: Hartman procedure, appendectomy; LPT: Hartman procedure after EX LPT | E; E+D; E+D | LB, 37; LB, 35; LB, 39 | |

| Costa et al. (2014) | 1 | 32 | − | − | NR | AP | Rectum, sigmoid colon | 25 | LPS: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 41 | |

| Appendicitis | Lane (1960) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR |

| Tedeschi and Masand (1971) | 1 | 30 | − | − | NR | AP | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Finch and Lee (1974) | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Appendix | 28 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | ND, 29 | |

| Nielsen et al. (1983) | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | AP | Appendix | Term | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | NR, NR | |

| Silvestrini and Marcial (1995) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, N, V, diarrhea | Appendix | 21 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Stefanidis et al. (1999) | 1 | 27 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, V | Appendix | 20 | LPT: appendectomy | E | LB, 39 | |

| Perez et al. (2007) | 1 | 21 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP, N, V | Appendix | 12 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D + I | NR, NR | |

| Utero-ovarian vessels | ||||||||||||

| Vessel rupture | Inoue et al. (1992) | 1 | 37 | NR | NR | NR | AP | Uterus | 29 | EX LPT | NR | LB, 29 |

| Mizumoto et al. (1996) | 1 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | Upper AP | Uterus | 28 | EX LPT | E+D | ND, 29 | |

| Leung et al. (1998) | 1 | 35 | − | − | NR | AP | Uterus | 33 | EX LPT | NR | IUD, 33 | |

| Ismail and Shervington (1999) | 2 | NR | NR; NR | NR | NR | AP; AP | Uterus; uterus | 33; 2 weeks post-partum | EX LPT; EX LPT | E; E | NR, 33; NR, NR | |

| Aziz et al. (2004) | 1 | 30 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Parametrium | 20 | EX LPT: left SO | E+D | IUD, 20 | |

| O'Leary (2006) | 1 | 41 | + | DTC, 9 months | NR | Lower AP, hyperpyrexia | Parametrium | 11 days post-partum | EX LPT: subtotal hysterectomy, BSO | E+D | NR, NR | |

| Wu et al. (2007) | 1 | 31 | + | Bilateral OC, 5 years | A | Lower AP | Uterus | 33 (twins) | EX LPT | NR | LB, LB, 34 | |

| Kirkinen et al. (2007) | 1 | 37 | − | − | NR | Vaginal bleeding | Parametrium | 22 | Uterine artery embolization during pregnancy and EX LPT post-partum | E+D | LB, 24 | |

| Katorza et al. (2007) | 2 | 29; 32 | −;+ | −; OC, DTC, LOA, NR | A; A | Lower AP; lower AP | Uterus; Uterus | 25 (twins); 29 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | LB, LB, 28; LB, 29 | |

| Passos et al. (2008) | 2 | 30; 32 | +;+ | OC, LOA, NR; LOA, 2 years | NR; NR | NR; AP | Parametrium; Parametrium and uterus | 32 (twins); 31 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | LB, LB, 32; LB, 31 | |

| Bouet et al. (2009) | 1 | 32 | − | − | NR | Lower AP, dyspnea | Parametrium | 24 | Thoracic drainage, EX LPT: left SO | E+D | IUD, 24 | |

| Roche et al. (2008) | 1 | 43 | + | LPS, NR | A | Lower AP, hematemesis | Uterus, uteroovarian ligament | 33 (twins) | EX LPT: OC | NR | IUD, IUD, 34 | |

| Wada et al. (2009) | 1 | 31 | + | Bilateral OC, DTC, LOA, 4 months | S | Lower AP | Uterus | Immediate post-partum | EX LPT | NR | LB, 37 | |

| Zhang et al. (2009) | 2 | 38; 35 | +; + | Bilateral OC, LOA, NR; DTC, LOA, NR | A; A | AP; upper AP, hyperpyrexia | Uterus; Uterus | 29 (twins); 35 | EX LPT; EX LPT | NR; NR | IUD, IUD, 29; LB, 35 | |

| Grunewald and Jördens (2010) | 1 | 33 | − | − | NR | AP | Sacro-uterine ligament | 27 | EX LPT | E | LB, 42 | |

| Gao et al. (2010) | 1 | 29 | − | − | NR | Upper AP | Uterus | 2 days post-partum | LPS: LOA, left internal iliac artery ligation | E+D | LB, NR | |

| Urinary system | ||||||||||||

| Uroperitoneum | Chiodo et al. (2008) | 1 | 25 | + | LOA, OC, DTC, 2 years | NR | AP, hematuria | Sacro-uterine ligament with right ureter and uterine artery involvement | 31 | LPT: ligation of the right uterine artery and ureteroneocystostomy | E+D | LB, 31 |

| Leone Roberti Maggiore et al. (2015) | 1 | 30 | + | Transurethral nodule resection | A | AP | Bladder | 27 | LPT: bladder resection | E+D | LB, 27 | |

| Distorsion of renal system anatomy | Yaqub et al. (2008) | 1 | 25 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Renal area | 34 | LPT: removal of cyst by blunt dissection and clamping vascular pedicle | E | LB, 34 |

| Pezzuto et al. (2009) | 1 | 34 | + | − | NR | AP | Broad ligament | 35 | Ureteral stent | NR | NR, NR | |

| . | Authors, years . | No. of cases . | Age (years) . | History of endometriosis . | Surgery before pregnancy (type, time before) . | Conception . | Presenting symptoms . | Site of complication . | Onset of complication (gestational week) . | Complication management during pregnancy . | Histological examination . | Pregnancy outcome, gestational week at delivery . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel | ||||||||||||

| Intestinal perforation | Clement (1977) | 1 | 28 | − | − | NR | Lower AP | Sigmoid colon | 37 | LPT: Hartmann procedure | E+D | LB, 37 |

| Gini et al. (1981) | 1 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | Vaginal bleeding, AP | Appendix | 35 | LPT: appendectomy | E+D | LB, 35 | |

| Floberg et al. (1984) | 1 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | Lower AP | Ovary, sigmoid colon | Immediate post-partum | LPT: OC, segmental bowel resection | E+D | LB, 41 | |