-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pedro Acién, Maribel Acién, The presentation and management of complex female genital malformations, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 22, Issue 1, January/February 2016, Pages 48–69, https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv048

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Common uterine anomalies are important owing to their impact on fertility, and complex mesonephric anomalies and certain Müllerian malformations are particularly important because they cause serious clinical symptoms and affect woman's quality of life, in addition to creating fertility problems. In these cases of complex female genital tract malformations, a correct diagnosis is essential to avoid inappropriate and/or unnecessary surgery. Therefore, acquiring and applying the appropriate embryological knowledge, management and therapy is a challenge for gynaecologists. Here, we considered complex malformations to be obstructive anomalies and/or those associated with cloacal and urogenital sinus anomalies, urinary and/or extragenital anomalies, or other clinical implications or symptoms creating a difficult differential diagnosis.

A diligent and comprehensive search of PubMed and Scopus was performed for all studies published from 1 January 2011 to 15 April 2015 (then updated up to September 2015) using the following search terms: ‘management’ in combination with either ‘female genital malformations’ or ‘female genital tract anomalies’ or ‘Müllerian anomalies’. The MeSH terms ‘renal agenesis’, ‘hydrocolpos’, ‘obstructed hemivagina’ ‘cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia’, ‘vaginal agenesis or atresia’, ‘Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome’, ‘uterine duplication’ and ‘cloacal anomalies’ were also used to compile a list of all publications containing these terms since 2011. The basic embryological considerations for understanding female genitourinary malformations were also revealed. Based on our experience and the updated literature review, we studied the definition and classification of the complex malformations, and we analysed the clinical presentation and different therapeutic strategies for each anomaly, including the embryological and clinical classification of female genitourinary malformations.

From 755 search retrieved references, 230 articles were analysed and 120 studied in detail. They were added to those included in a previous systematic review. Here, we report the clinical presentation and management of: agenesis or hypoplasia of one urogenital ridge; unilateral renal agenesis and ipsilateral blind or obstructed hemivagina or unilateral cervicovaginal agenesis; cavitated and non-communicating uterine horns and Müllerian atresias or agenesis, including Rokitansky syndrome; anomalies of the cloaca and urogenital sinus, including congenital vagino-vesical fistulas and cloacal anomalies; malformative combinations and other complex malformations. The clinical symptoms and therapeutic strategies for each complex genitourinary malformation are discussed. In general, surgical techniques to correct genital malformations depend on the type of anomaly, its complexity, the patient's symptoms and the correct embryological interpretation of the anomaly. Most anomalies can typically be resolved vaginally or by hysteroscopy, but laparoscopy or laparotomy is often required as well. We also include additional discussion of the catalogue and classification systems for female genital malformations, the systematic association between renal agenesis and ipsilateral genital malformation, and accessory and cavitated uterine masses.

Knowledge of the correct genitourinary embryology is essential for the understanding, study, diagnosis and subsequent treatment of genital malformations, especially complex ones and those that lead to gynaecological and reproductive problems, particularly in young patients. Some anomalies may require complex surgery involving multiple specialties, and patients should therefore be referred to centres that have experience in treating complex genital malformations.

Introduction

Uterine malformations have been reported to occur in 3–4% of women overall, in 4% of infertile women and in 15% of those who have experienced recurrent miscarriage (March, 1990; Acién, 1997; Grimbizis et al., 2001). Other studies identified in a systematic review to present the prevalence and diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies in women with reproductive failure (Saravelos et al., 2008) observed higher percentages: 6.7% in the general population, 7.3% in the infertile population and 16.7% in the recurrent miscarriage patients. The corresponding prevalence values in unselected and high-risk populations (Chan et al., 2011) were 5.5, 8, 13.3 and 24.5% in those with miscarriage and infertility. Therefore, common uterine or Müllerian anomalies are important because of their effects on fertility, but mesonephric anomalies, certain obstructive Müllerian malformations and other malformative combinations are particularly important because they cause several clinical symptoms and impact the patient's quality of life, in addition to creating fertility problems. Such complex malformations of the female genital tract are not common (17.3% of all female genitourinary malformations; Acién and Acién, 2007), but they can cause severe gynaecological symptoms and other problems, particularly in young women.

In some patients, genital anomalies are associated with other extragenital malformations (Acién et al., 1991; Li et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2001), and they may have a genetic origin (Moerman et al., 1994; Acién et al., 2010c), while in other patients, these anomalies could result from an environmental insult or teratogenic drugs (diethylstilboestrol (DES) syndrome). However, in most cases, there is no evident aetiology or association. Currently, certain genetic mutations and deletions are been studied (Dang et al., 2012; Sanna-Cherchi et al., 2013; Murry et al., 2015; Vera-Carbonell et al., 2015), although these studies have lacked clear identifiable and related pathogenic mechanisms. Therefore, it appears that genital malformations are influenced by multifactorial, polygenic and familial mechanisms that together create a favourable environment for the development of the anomaly (Acién and Acién, 2013a).

The clinical presentation of each anomaly and genital malformation is different; given the diversity of situations and the possible combinations of the wide range of female genital tract malformations (FGTM), it is nearly impossible to outline a single uniform treatment and management plan. Most common malformations do not typically require surgery, but the majority of complex cases do and the solution is often simple; it is essential to obtain a correct diagnosis to avoid inappropriate and/or unnecessary surgery. Therefore, selecting the appropriate management and therapeutic strategy presents a challenge for gynaecologists. In this paper, we analyse the clinical presentation, review the different therapeutic strategies and discuss the cataloging and classification of complex female genitourinary anomalies.

Methods

We performed a diligent and comprehensive search of PubMed and Scopus for all studies published from 1 January 2011 to 15 April 2015 using the search term ‘management’ in combination with either ‘female genital malformations’ or ‘female genital tract anomalies’ or ‘Müllerian anomalies’. The MeSH terms ‘renal agenesis’, ‘hydrocolpos’, ‘obstructed hemivagina’, ‘cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia’, ‘vaginal agenesis or atresia’, ‘Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome’, ‘uterine duplication’ and ‘cloacal anomalies’ were also used in the search. This search has been updated up to September 2015. Our reference list of the included articles (755 documents) was reviewed to identify case reports, case series, reviews and relevant studies related to complex female genital malformations, and these amounted to 120 full-length reviewed articles and 110 abstracts, including ‘Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome’ (56 papers) and ‘cervicovaginal agenesis’ or ‘vaginal aplasia’ (105 papers). In a previous systematic review, these terms were analysed in publications since 1950 (Acién and Acién, 2011).

Ethical approval was not required. The authors have the signed consent of the patients whose images are included or the permission of those that were previously published.

Cataloging complex female genital malformations

There are no widely accepted criteria for classifying certain female genitourinary anomalies as complex malformations. Even the definition of a female genital malformation is controversial. Excluding the anomalies in sexual determination and differentiation, malformations of the female genital tract should include those anomalies that affect the development and morphology of the Fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, vulvae and vaginal introitus, with or without associated ovarian, urinary, skeletal or other organ malformations (Acién and Acién, 2007). It is generally accepted that complex anomalies can be defined as those malformations that include more than one organ or part of the female genital tract and/or more than one stage in embryological maldevelopment. Although this is correct, certain malformations that affect a single organ (e.g. Müllerian segmentary atresias) cause severe symptoms and complications (retrograde menstruation and endometriosis) and are associated with a difficult diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, we considered complex malformations to be obstructive anomalies (due to partial unilateral agenesis or Müllerian segmentary atresia) and/or those associated with cloacal and urogenital sinus anomalies, urinary and/or extragenital anomalies, or other clinical implications or symptoms creating a difficult differential diagnosis. All of these complex malformations are included in Table I, which notes the embryological and clinical classification of each complex malformation, which together represent 17.3% of all female genitourinary malformations (Acién and Acién, 2007). Table I also analyzes the correspondence of these complex malformations as included in the American Fertility Society (currently American Society for Reproductive Medicine, ASRM) classification of Müllerian anomalies (American Fertility Society, 1988), and in the new European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology/European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESHRE/ESGE) classification system of female genital anomalies (Grimbizis et al., 2013).

Complex malformations of the female genitourinary tract and their inclusion in the embryological and clinical classification of female genital malformations (Acién, 1992; Acién et al., 2004c; Acién and Acién, 2011) and in other classification systems (AFS/ASRM, 1988; ESHRE/ESGE, 2013).

| Complex malformations of the female genital tract . | As included in the embryological and clinical classification (Acién and Acién, 2011) . | As included in the AFS/ASRM classification of Müllerian anomalies (American Fertility Society, 1988) . | As included in the new ESHRE/ESGE classification system of female genital anomalies (Grimbizis et al., 2013) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agenesis or hypoplasia of a urogenital ridge | Group I: I.1. Rokitansky syndrome with URA. I.2. Unicornuate uterus with contralateral RA | Class Ie (uterovaginal agenesis). Additional findings: URA. Class II (unicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U5 (aplastic)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA. U4 (hemi-uterus)/C0/V0. Associated anomalies: URA |

| 2. Unilateral renal agenesis (URA) (sometimes ectopic ureter and/or renal dysplasia) and ipsilateral blind or atretic hemivagina syndrome showing | Group II: All distal mesonephric anomalies: uterine duplicity with blind hemivagina (or atresia) and URA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C1, C2 or C3 (septate, double or unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2, V1 or V0 (obstructing, non-obstructing vaginal septum, or normal vagina). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| A. Obstructed or blind hemivagina with large haematocolpos (Wunderlich syndrome) | II.1 Didelphys or bicornuate (rarely septate) uterus with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C2, C1 (double, or septate cervix)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| B. A Gartner duct pseudocyst in the upper anterolateral wall of the vagina (Herlyn–Werner syndrome) | II.2 Bicornuate communicating uterus with athretic blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter, or mesonephric remnants). | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum).a Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| C. A short vaginal septum or a communicating buttonhole | II.3 Didelphys or bicornis-bicollis uterus with a short vaginal septum or buttonhole, and URA | Class III or IVa (didelphus or bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3b, U3c (bicorporeal uterus)/C2 (double ‘normal'cervix)/V1 (longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum. Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| D. Bicornuate-unicollis communicating uterus with unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.4 Bicornis-unicollis communicating uterus with an anomalous horn and ipsilateral RA | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).b Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| E. Didelphys/unicornuate uterus with unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.5 Didelphys (ultrasound, MR)/unicornuate uterus with contralateral unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | Class III (didelphus) or IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating). Additional findings: URA | U3b or U4a (complete bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).c Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| 3. Cavitated non-communicating uterine horns (CNCUH) and Müllerian atresias | Group III. Isolated Müllerian anomalies affecting to ducts, tubercle or both elements | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| A. CNCUH associated with unicornuate/bicornuate uterus (sometimes septate uterus, Robert's uterus) | III.A.2 or III.A.4 Unicornuate uterus (bicornuate and sometimes septate) with cavitated non-communicated uterine horn | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina). U2b/C3/V0 in certain cases of Robert's uterus? |

| B. Segmentary atresia of the one Müllerian duct with a detached horn | III.A.2 Unicornuate uterus with detached cavitated non-communicated uterine horn due to segmentary atresia | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| C. Vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia with a functional uterus | III.B.1 Complete vaginal or cervicovaginal atresia | Class Ia, Ib (hypoplasis/agenesis, vaginal, cervical) | U0 (normal uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| D. Vaginal segmentary atresia and transverse vaginal septum | III.B.2 Complete or incomplete transverse vaginal septum | Not included. Isolated vaginal anomalies | U0 (normal uterus)/C0 (normal cervix)/V3 (transverse vaginal septum and/or imperforate hymen) |

| E. Rokitansky or MRKH syndrome | III.C. Complete uterovaginal agenesis (sometimes with a cavitated rudimentary horn) | Class Ic (combined uterovaginal agenesis) | U5b or U5a (aplastic uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

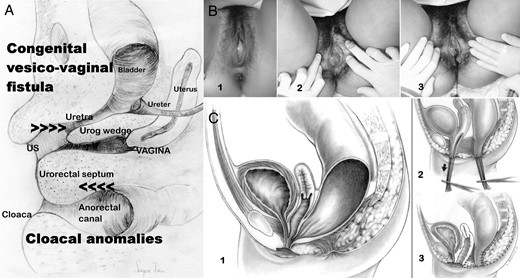

| 4. Congenital vagino-vesical fistula (pseudo-lower vagina atresia) and cloacal anomalies. | Group V. Anomalies of the cloaca and urogenital sinus Imperforated hymen. Congenital vesicovaginal fistula. Cloacal exstrophy | Not included | U6 (unclassified malformations)/V3 (imperforate hymen) |

| 5. Variable malformative combinations | Group VI. Malformative combinations | Not included | U6 (unclassified anomalies). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies |

| Complex malformations of the female genital tract . | As included in the embryological and clinical classification (Acién and Acién, 2011) . | As included in the AFS/ASRM classification of Müllerian anomalies (American Fertility Society, 1988) . | As included in the new ESHRE/ESGE classification system of female genital anomalies (Grimbizis et al., 2013) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agenesis or hypoplasia of a urogenital ridge | Group I: I.1. Rokitansky syndrome with URA. I.2. Unicornuate uterus with contralateral RA | Class Ie (uterovaginal agenesis). Additional findings: URA. Class II (unicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U5 (aplastic)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA. U4 (hemi-uterus)/C0/V0. Associated anomalies: URA |

| 2. Unilateral renal agenesis (URA) (sometimes ectopic ureter and/or renal dysplasia) and ipsilateral blind or atretic hemivagina syndrome showing | Group II: All distal mesonephric anomalies: uterine duplicity with blind hemivagina (or atresia) and URA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C1, C2 or C3 (septate, double or unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2, V1 or V0 (obstructing, non-obstructing vaginal septum, or normal vagina). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| A. Obstructed or blind hemivagina with large haematocolpos (Wunderlich syndrome) | II.1 Didelphys or bicornuate (rarely septate) uterus with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C2, C1 (double, or septate cervix)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| B. A Gartner duct pseudocyst in the upper anterolateral wall of the vagina (Herlyn–Werner syndrome) | II.2 Bicornuate communicating uterus with athretic blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter, or mesonephric remnants). | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum).a Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| C. A short vaginal septum or a communicating buttonhole | II.3 Didelphys or bicornis-bicollis uterus with a short vaginal septum or buttonhole, and URA | Class III or IVa (didelphus or bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3b, U3c (bicorporeal uterus)/C2 (double ‘normal'cervix)/V1 (longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum. Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| D. Bicornuate-unicollis communicating uterus with unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.4 Bicornis-unicollis communicating uterus with an anomalous horn and ipsilateral RA | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).b Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| E. Didelphys/unicornuate uterus with unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.5 Didelphys (ultrasound, MR)/unicornuate uterus with contralateral unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | Class III (didelphus) or IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating). Additional findings: URA | U3b or U4a (complete bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).c Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| 3. Cavitated non-communicating uterine horns (CNCUH) and Müllerian atresias | Group III. Isolated Müllerian anomalies affecting to ducts, tubercle or both elements | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| A. CNCUH associated with unicornuate/bicornuate uterus (sometimes septate uterus, Robert's uterus) | III.A.2 or III.A.4 Unicornuate uterus (bicornuate and sometimes septate) with cavitated non-communicated uterine horn | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina). U2b/C3/V0 in certain cases of Robert's uterus? |

| B. Segmentary atresia of the one Müllerian duct with a detached horn | III.A.2 Unicornuate uterus with detached cavitated non-communicated uterine horn due to segmentary atresia | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| C. Vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia with a functional uterus | III.B.1 Complete vaginal or cervicovaginal atresia | Class Ia, Ib (hypoplasis/agenesis, vaginal, cervical) | U0 (normal uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| D. Vaginal segmentary atresia and transverse vaginal septum | III.B.2 Complete or incomplete transverse vaginal septum | Not included. Isolated vaginal anomalies | U0 (normal uterus)/C0 (normal cervix)/V3 (transverse vaginal septum and/or imperforate hymen) |

| E. Rokitansky or MRKH syndrome | III.C. Complete uterovaginal agenesis (sometimes with a cavitated rudimentary horn) | Class Ic (combined uterovaginal agenesis) | U5b or U5a (aplastic uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| 4. Congenital vagino-vesical fistula (pseudo-lower vagina atresia) and cloacal anomalies. | Group V. Anomalies of the cloaca and urogenital sinus Imperforated hymen. Congenital vesicovaginal fistula. Cloacal exstrophy | Not included | U6 (unclassified malformations)/V3 (imperforate hymen) |

| 5. Variable malformative combinations | Group VI. Malformative combinations | Not included | U6 (unclassified anomalies). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies |

AFS/ASRM, American Fertility Society/American Society for Reproductive Medicine; ESHRE/ESGE, European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology/European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy; MRKH, Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster Hauser; MR, magnetic resonance; URA, unilateral renal agenesis; RA, renal agenesis; U, uterus; C, Cervix; V, vagina.

aIt could initially be catalogued as U3a/C0/V0.

bIt could initially be catalogued as U3a/C0/V0 except suggestion from intravenous pyelography and performance of a hysterosalpingography and/or magnetic resonance.

cIt could initially be catalogued as U3b/C0/V0 or U4a/C0/V0.

Complex malformations of the female genitourinary tract and their inclusion in the embryological and clinical classification of female genital malformations (Acién, 1992; Acién et al., 2004c; Acién and Acién, 2011) and in other classification systems (AFS/ASRM, 1988; ESHRE/ESGE, 2013).

| Complex malformations of the female genital tract . | As included in the embryological and clinical classification (Acién and Acién, 2011) . | As included in the AFS/ASRM classification of Müllerian anomalies (American Fertility Society, 1988) . | As included in the new ESHRE/ESGE classification system of female genital anomalies (Grimbizis et al., 2013) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agenesis or hypoplasia of a urogenital ridge | Group I: I.1. Rokitansky syndrome with URA. I.2. Unicornuate uterus with contralateral RA | Class Ie (uterovaginal agenesis). Additional findings: URA. Class II (unicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U5 (aplastic)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA. U4 (hemi-uterus)/C0/V0. Associated anomalies: URA |

| 2. Unilateral renal agenesis (URA) (sometimes ectopic ureter and/or renal dysplasia) and ipsilateral blind or atretic hemivagina syndrome showing | Group II: All distal mesonephric anomalies: uterine duplicity with blind hemivagina (or atresia) and URA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C1, C2 or C3 (septate, double or unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2, V1 or V0 (obstructing, non-obstructing vaginal septum, or normal vagina). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| A. Obstructed or blind hemivagina with large haematocolpos (Wunderlich syndrome) | II.1 Didelphys or bicornuate (rarely septate) uterus with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C2, C1 (double, or septate cervix)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| B. A Gartner duct pseudocyst in the upper anterolateral wall of the vagina (Herlyn–Werner syndrome) | II.2 Bicornuate communicating uterus with athretic blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter, or mesonephric remnants). | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum).a Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| C. A short vaginal septum or a communicating buttonhole | II.3 Didelphys or bicornis-bicollis uterus with a short vaginal septum or buttonhole, and URA | Class III or IVa (didelphus or bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3b, U3c (bicorporeal uterus)/C2 (double ‘normal'cervix)/V1 (longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum. Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| D. Bicornuate-unicollis communicating uterus with unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.4 Bicornis-unicollis communicating uterus with an anomalous horn and ipsilateral RA | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).b Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| E. Didelphys/unicornuate uterus with unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.5 Didelphys (ultrasound, MR)/unicornuate uterus with contralateral unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | Class III (didelphus) or IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating). Additional findings: URA | U3b or U4a (complete bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).c Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| 3. Cavitated non-communicating uterine horns (CNCUH) and Müllerian atresias | Group III. Isolated Müllerian anomalies affecting to ducts, tubercle or both elements | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| A. CNCUH associated with unicornuate/bicornuate uterus (sometimes septate uterus, Robert's uterus) | III.A.2 or III.A.4 Unicornuate uterus (bicornuate and sometimes septate) with cavitated non-communicated uterine horn | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina). U2b/C3/V0 in certain cases of Robert's uterus? |

| B. Segmentary atresia of the one Müllerian duct with a detached horn | III.A.2 Unicornuate uterus with detached cavitated non-communicated uterine horn due to segmentary atresia | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| C. Vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia with a functional uterus | III.B.1 Complete vaginal or cervicovaginal atresia | Class Ia, Ib (hypoplasis/agenesis, vaginal, cervical) | U0 (normal uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| D. Vaginal segmentary atresia and transverse vaginal septum | III.B.2 Complete or incomplete transverse vaginal septum | Not included. Isolated vaginal anomalies | U0 (normal uterus)/C0 (normal cervix)/V3 (transverse vaginal septum and/or imperforate hymen) |

| E. Rokitansky or MRKH syndrome | III.C. Complete uterovaginal agenesis (sometimes with a cavitated rudimentary horn) | Class Ic (combined uterovaginal agenesis) | U5b or U5a (aplastic uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| 4. Congenital vagino-vesical fistula (pseudo-lower vagina atresia) and cloacal anomalies. | Group V. Anomalies of the cloaca and urogenital sinus Imperforated hymen. Congenital vesicovaginal fistula. Cloacal exstrophy | Not included | U6 (unclassified malformations)/V3 (imperforate hymen) |

| 5. Variable malformative combinations | Group VI. Malformative combinations | Not included | U6 (unclassified anomalies). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies |

| Complex malformations of the female genital tract . | As included in the embryological and clinical classification (Acién and Acién, 2011) . | As included in the AFS/ASRM classification of Müllerian anomalies (American Fertility Society, 1988) . | As included in the new ESHRE/ESGE classification system of female genital anomalies (Grimbizis et al., 2013) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agenesis or hypoplasia of a urogenital ridge | Group I: I.1. Rokitansky syndrome with URA. I.2. Unicornuate uterus with contralateral RA | Class Ie (uterovaginal agenesis). Additional findings: URA. Class II (unicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U5 (aplastic)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA. U4 (hemi-uterus)/C0/V0. Associated anomalies: URA |

| 2. Unilateral renal agenesis (URA) (sometimes ectopic ureter and/or renal dysplasia) and ipsilateral blind or atretic hemivagina syndrome showing | Group II: All distal mesonephric anomalies: uterine duplicity with blind hemivagina (or atresia) and URA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C1, C2 or C3 (septate, double or unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2, V1 or V0 (obstructing, non-obstructing vaginal septum, or normal vagina). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| A. Obstructed or blind hemivagina with large haematocolpos (Wunderlich syndrome) | II.1 Didelphys or bicornuate (rarely septate) uterus with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia, or other ipsilateral renal anomalies) | Class III, IV or V (didelphus, bicornuate or septate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3 or U2 (bicorporeal or septate uterus)/C2, C1 (double, or septate cervix)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| B. A Gartner duct pseudocyst in the upper anterolateral wall of the vagina (Herlyn–Werner syndrome) | II.2 Bicornuate communicating uterus with athretic blind hemivagina and ipsilateral RA (sometimes ectopic ureter, or mesonephric remnants). | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V2 (longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum).a Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| C. A short vaginal septum or a communicating buttonhole | II.3 Didelphys or bicornis-bicollis uterus with a short vaginal septum or buttonhole, and URA | Class III or IVa (didelphus or bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: vagina, cervix, kidneys | U3b, U3c (bicorporeal uterus)/C2 (double ‘normal'cervix)/V1 (longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum. Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA, ectopic ureter |

| D. Bicornuate-unicollis communicating uterus with unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.4 Bicornis-unicollis communicating uterus with an anomalous horn and ipsilateral RA | Class IVb (partial bicornuate uterus). Additional findings: URA | U3a (partial bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).b Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| E. Didelphys/unicornuate uterus with unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | II.5 Didelphys (ultrasound, MR)/unicornuate uterus with contralateral unattached and cavitated rudimentary horn, unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and ipsilateral URA | Class III (didelphus) or IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating). Additional findings: URA | U3b or U4a (complete bicorporeal uterus)/C3 (unilateral cervical aplasia)/V0 (normal vagina).c Associated non-Müllerian anomalies: URA |

| 3. Cavitated non-communicating uterine horns (CNCUH) and Müllerian atresias | Group III. Isolated Müllerian anomalies affecting to ducts, tubercle or both elements | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| A. CNCUH associated with unicornuate/bicornuate uterus (sometimes septate uterus, Robert's uterus) | III.A.2 or III.A.4 Unicornuate uterus (bicornuate and sometimes septate) with cavitated non-communicated uterine horn | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina). U2b/C3/V0 in certain cases of Robert's uterus? |

| B. Segmentary atresia of the one Müllerian duct with a detached horn | III.A.2 Unicornuate uterus with detached cavitated non-communicated uterine horn due to segmentary atresia | Class IIb (unicornuate uterus, non-communicating) | U4a (hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity)/C0 (normal cervix)/V0 (normal vagina) |

| C. Vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia with a functional uterus | III.B.1 Complete vaginal or cervicovaginal atresia | Class Ia, Ib (hypoplasis/agenesis, vaginal, cervical) | U0 (normal uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| D. Vaginal segmentary atresia and transverse vaginal septum | III.B.2 Complete or incomplete transverse vaginal septum | Not included. Isolated vaginal anomalies | U0 (normal uterus)/C0 (normal cervix)/V3 (transverse vaginal septum and/or imperforate hymen) |

| E. Rokitansky or MRKH syndrome | III.C. Complete uterovaginal agenesis (sometimes with a cavitated rudimentary horn) | Class Ic (combined uterovaginal agenesis) | U5b or U5a (aplastic uterus)/C4 (cervical aplasia)/V4 (vaginal aplasia) |

| 4. Congenital vagino-vesical fistula (pseudo-lower vagina atresia) and cloacal anomalies. | Group V. Anomalies of the cloaca and urogenital sinus Imperforated hymen. Congenital vesicovaginal fistula. Cloacal exstrophy | Not included | U6 (unclassified malformations)/V3 (imperforate hymen) |

| 5. Variable malformative combinations | Group VI. Malformative combinations | Not included | U6 (unclassified anomalies). Associated non-Müllerian anomalies |

AFS/ASRM, American Fertility Society/American Society for Reproductive Medicine; ESHRE/ESGE, European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology/European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy; MRKH, Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster Hauser; MR, magnetic resonance; URA, unilateral renal agenesis; RA, renal agenesis; U, uterus; C, Cervix; V, vagina.

aIt could initially be catalogued as U3a/C0/V0.

bIt could initially be catalogued as U3a/C0/V0 except suggestion from intravenous pyelography and performance of a hysterosalpingography and/or magnetic resonance.

cIt could initially be catalogued as U3b/C0/V0 or U4a/C0/V0.

Embryological considerations

Certain embryological knowledge should be generally accepted.

The formation of the gonads is independent of that of the urogenital tract (Moore, 1976, 1988; Byskov, 1986; Acién, 1992), although agenesis of a complete urogenital ridge implies ipsilateral gonadal agenesis or dysgenesis.

The Müllerian ducts form the Fallopian tubes and uterus up to the external cervical os but without reaching the urogenital sinus (Moore, 1976; Sadler, 1986; Acién, 1992; Moore and Persaud, 1999; Sánchez-Ferrer et al., 2006).

The Wolffian ducts open into the urogenital sinus, and the ureteral bud sprouts from the caudal tip of their opening (Campbell, 1928; Mackie, 1978; Acién, 1992).

The Müller tubercle is located between the distal portion of the Müllerian ducts and the urogenital sinus, and the Wolffian ducts are positioned at both sides (Koff, 1933; Grüenwald, 1941; Marshall and Beisel, 1978; Dohr and Tarmann, 1984; Acién, 1992; Sánchez-Ferrer et al., 2006).

When considering the Müllerian development processes, we must distinguish the following:

Anomalies caused by total or partial agenesis of one (unicornuate uterus) or both Müllerian ducts [Rokitansky or Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser (MRKH) syndrome];

Anomalies caused by the total or partial absence of fusion, i.e. didelphys uterus and bicornuate (bicollis and unicollis) uterus;

Anomalies caused by total or partial lack of reabsorption of the septum between the Müllerian ducts (septate and sub-septate uterus);

Anomalies caused by a lack of later development [hypoplastic uterus, T-shaped and DES exposure (DES syndrome)];

Segmentary defects and combinations.

This classification system for uterine or Müllerian malformations corresponds to the traditional classifications (Strassmann, 1907; Jarcho, 1946; Buttram and Gibbons, 1979), the widely used ASRM classification (1988) or that included in Netter's Atlas (Netter, 1979). The latest ESHRE/ESGE classification system ‘UCV’ (Grimbizis et al., 2012, 2013) is also based on those concepts (Müllerian development processes), with anatomy providing the basis for the systematic categorization of anomalies. Transitional uterine malformations and those ‘without a classification’ (Acién et al., 2009) are well cataloged within the ESHRE/ESGE system.

These classification schemes essentially refer to only Müllerian anomalies or the anatomic visual appearance and do not explain or suggest the actual origin of female genitourinary tract malformations nor their appropriate therapeutic correction, except for the uterine anomalies where the cataloguing of the ESHRE/ESGE classes (septate, bicorporeal) and sub-classes seems to be better than in the ASRM classification, especially considering fertility problems.

Woolf and Allen (1953) discovered several possible associations between uterine or genital tract malformation and renal agenesis, which is always ipsilateral and is considered the consequence of a mesonephric anomaly. Usually, if both kidneys are present, this anomaly does not occur. The mesonephric or Wolffian ducts are as important as the Müllerian ducts and the Müller tubercle. Specifically, these structures are fundamental for the appropriate development of the female genital tract, particularly when considering three key points related to the previously mentioned embryological knowledge: the embryological development of the human vagina does not proceed from the urogenital sinus and Müllerian ducts (as classically thought) but instead proceeds from the Wolffian ducts and the Müllerian tubercle (Bok and Drews, 1983; Mauch et al., 1985; Acién, 1992; Sánchez-Ferrer et al., 2006); the appropriate development, fusion and resorption of the separating wall between the Müllerian ducts is induced by the Wolffian ducts, which are located on either side and act as guide elements for Müllerian development (Grüenwald, 1941; Magee et al., 1979); the ureteral buds sprout and exit from the opening of the Wolffian ducts into the urogenital sinus, and the definitive kidneys are formed when these buds approach the metanephros (Campbell, 1928; Mackie, 1978). Therefore, a distal Wolffian or mesonephric lesion will promote a vaginal anomaly, a uterine anomaly and ipsilateral renal agenesis or renal dysplasia with or without ectopic ureter (Acién, 1992; Acién et al., 2004c, 2010b; Acién and Acién, 2007, 2010, 2011, 2013b), i.e. a complex malformation.

Results

From 755 retrieved references, 230 articles were analysed and 120 studied in detail. They were added to those included in a previous systematic review (Acién and Acién, 2011). Based on our experience and an updated literature review, we briefly analyse the clinical presentation of, and different therapeutic strategies for, each complex malformation included in Table I as well as their cataloging with the embryological and clinical classification of female genitourinary malformations and other classification system.

Agenesis or hypoplasia of the urogenital ridge (1.6% of all FGTM; Acién and Acién, 2007)

The anomalies included in this group might not be considered complex malformations due to the lack of relevant symptoms, although they are associated with unilateral renal agenesis (URA). This association must be considered in reproductive medicine, not only because of the uterine malformation but also because of the ipsilateral absence of the Fallopian tube and ovary (Haydardedeoglu et al., 2006). Clinical manifestations are often due to the absence of the kidney, ovary and Fallopian tube as well as a hemiuterus or hemivagina (undetectable) on one side. In some cases, the ovary was situated ectopically (Kollia et al., 2014). The most common presentation is a unicornuate uterus without a rudimentary horn or adnexa (tube and ovary) on the opposite side. This condition is sometimes associated with skeletal and/or auditory anomalies (King et al., 1987; Acién et al., 1991; Acién and Acién, 2010) or with branchio-oto-renal syndrome (Safaya et al., 2014). No treatment is necessary. If contralateral Müllerian agenesis is also evident, the diagnosis is Rokitansky syndrome with URA (Acién et al., 2010c) or atypical MRKH syndrome (Strübbe et al., 1993; Gorgojo et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2007), which can require laparoscopy for diagnosis [although this can also be given by magnetic resonance imaging (MR) and dilation or surgery to create a neovagina (Nakhal and Creighton, 2012)]. Recently, a patient with such a malformation (atypical Rokitansky syndrome) achieved the first live birth after receiving a uterus transplant (Brännström et al., 2015).

URA and ipsilateral blind or atretic hemivagina syndrome (distal mesonephric anomalies) (7.1% of all FGTM)

The clinical presentation of these anomalies includes a duplicate uterus (didelphys, bicornuate or, less commonly, septate uterus) with one of the following subtypes: (i) large haematocolpos in a blind or obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis or ectopic ureter and renal dysplasia; (ii) Gartner's duct pseudocyst in the anterolateral wall of the permeable vagina, with ipsilateral renal agenesis or dysplasia; (iii) partial reabsorption of the vaginal septum and renal agenesis or dysplasia or (iv) complete unilateral vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis, with or without communication between both hemi-uteri and ipsilateral renal agenesis or dysplasia (Acién et al., 2004a; Acién and Acién, 2011, 2013a). All of these conditions are variants of renal agenesis and ipsilateral blind hemivagina syndrome, which we described previously as a systematic association (Acién et al., 1987, 1991) that clinicians should be aware of. There is sometimes no renal agenesis, only dysplasia that varies in severity, with an ectopic ureter opening into the blind hemivagina (Acién et al., 1990, 2004b). Although cases with normal kidneys have been described (Pinsonneault and Goldstein, 1985; Johnson and Hillman, 1986; Smith and Laufer, 2007), the analysis of what is referred in these works shows that there was always some kind of ipsilateral reno-ureteral anomaly or malrotation (Heinonen, 2000); anomaly that nowadays would be more evident after directed investigation with MR, hysterosalpingography (HSG), urography and endoscopy.

This syndrome includes others described in the literature that relate to renal agenesis and unilateral haematocolpos or Gartner duct pseudocyst [Wunderlich (1976) and Herlyn and Werner (1971) syndromes, respectively], which is frequently reported as ‘Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome’, as well as to ‘obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OVHIRA) syndrome’ (Smith and Laufer, 2007) and others (Fedele et al., 2013).

The clinical presentation and management are different for each variant or subtype.

Cases with unilateral obstructed or blind hemivagina with large haematocolpos (in girls, hydrocolpos) (Spencer and Levy, 1962; Rosenberg et al., 1982; Burbige and Hensle, 1984) clinically manifest as progressive intra- and postmenstrual dysmenorrhea present from menarche, although it was frequently diagnosed at 16–18 years of age in our patients. In the series published by Tong et al. (2013), the age at diagnosis was 13 ± 2 years (mean ± SD) in cases with complete obstruction and 24.7 ± 7.7 years (mean ± SD) in those with incomplete obstruction. However, the clinical presentation is highly variable, frequently delaying diagnosis and leading to significant complications (Acién et al., 1981). Occasionally, the condition can be diagnosed following acute urinary retention (Alumbreros-Andujar et al., 2014). There are also some cases described in girls under 5 years old (Sanghvi et al., 2011; Angotti et al., 2015). Angotti et al. (2015) highlight that this syndrome should be taken into consideration as differential diagnosis in newborn with prenatal ultrasonography of a cystic mass behind the urinary bladder in the absence of a kidney. Lopes Dias and Jogo (2015) also state that when a prenatal diagnosis of URA in newborn girls is known, a gynaecological imaging study should be performed to exclude uterine and vaginal abnormalities.

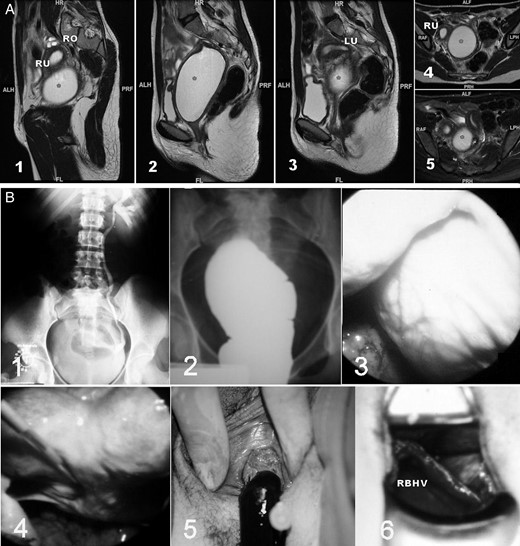

In general, examination reveals an anterolateral bulge in the vagina that makes it impossible to reach the cervix. Ultrasound can greatly aid in the diagnosis if haematocolpos is suspected, and the diagnosis is confirmed when i.v. pyelography (IVP) and/or cystoscopy show renal agenesis. Transvaginal puncture allows the chocolate blood to drain out, and the injection of a contrast agent permits the visualization of the blind vagina and fills the corresponding hemi-uterus and tube in a retrograde manner. Currently, three-dimensional ultrasound, and especially MR, are the primary diagnostic tools, but they must be adequately interpreted to be conclusive: MR of the case presented in Fig. 1A resulted in a diagnosis of endometrioma. Because the diagnosis is incorrect in many cases, leading to unnecessary and inadequate procedures (Nawfal et al., 2011), it is imperative to have acute clinical suspicion when encountering a patient with urogenital anomalies (Adair et al., 2011; Gungor-Ugurlacan et al., 2014). Tzialidou-Palermo et al. (2012) have also presented the diagnostic challenges of hemihaematocolpos and dysmenorrhea in adolescents and suggested a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm to reduce destructive interventions. In these patients laparoscopy could be performed, and it will show a didelphys or bicornuate uterus (with absence of visualization of the rectovesical ligament—Heinonen, 2013b) and possibly a haematosalpinx and endometriosis that will improve when the obstruction is resolved. The same surgical procedure should include resection of the separating wall between the permeable and blind hemivagina, with drainage of the haematocolpos (Fig. 1B) (Vallerie and Breech, 2010). In general, a single transvaginal surgical procedure, including removal of the obstructed vaginal septum and marsupialization of the blind hemivagina, solves the symptoms of this pathology (Tzialidou-Palermo et al., 2012). Nonetheless, resection of the obstructive vaginal septum may be difficult. Some authors prefer excision of the vaginal septum and a marsupialization-type operation. This prevents reclosing of the opening. However, clinicians should be aware that in the case of uterus didelphys, the vaginal septum has two layers (one per hemivagina) that might peel off. After the haematocolpos is drained, inadvertent resection of just one layer might occur, with the other remaining flaccid, covering the hemi-cervix of the blind side and suggesting that the cervix is absent, or in the future, that a transverse vaginal septum is present. Some authors recommend hysteroscopic resection of the oblique vaginal septum in virgin girls to maintain hymen integrity (Cetinkaya et al., 2011; Sanghvi et al., 2011; Nassif et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2015). Dietrich et al. (2014b) described the technique for vaginal septum resection in detail, explaining the need for care in avoiding complications (e.g. establish landmarks, determine the deviation and thickness of the septum, perform a wide resection with vaginoscopy, use a Foley balloon catheter and respond appropriately to microperforations). There is sometimes limited inter-uterine (at the level of the isthmus) or inter-vaginal (at the vaginal apex) communication. In these cases, persistent postmenstrual haemorrhagia (sometimes malodorous) is characteristic before the patient presents with pyocolpos in the obstructed vaginal canal (Dhar et al., 2011; Cortés-Contreras et al., 2014; Wozniakowska et al., 2014). In other cases, there is intermittent mucopurulent discharge or a history of acute pelvic inflammation (Tong et al., 2013). The inter-uterine communication may also be extensive and asymptomatic if there are no associated pathologies. Likewise, there may be an ectopic ureter opening into the blind vagina (Acién et al., 1990), and because communication between both sides is common, the symptom is permanent urinary incontinence between instances of normal micturition. The injection of a contrast agent into the blind hemivagina, or the uterus in cases of communicating uteri, will enable the identification of the ectopic ureter by retrograde filling (Acién et al., 2004b). These cases might require nephrectomy and ureterectomy of the dysplastic kidney (Acién et al., 1990, 2004b).

Unilateral renal agenesis and ipsilateral obstructed hemivagina with haematocolpos. (A) Magnetic resonance imaging (MR) of a 16-year-old patient with a unilateral blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis who experienced strong dysmenorrhea. After clinical examination and MR, she was diagnosed with endometrioma in another hospital. However, a didelphys uterus and right haematocolpos (*) can be observed; 1–3, sagittal cuts from right to left; 4–5, axial cuts from caudal to cranial. RO, right ovary; RU, right hemiuterus; LU, left hemiuterus. ALH/ALF, anterior; PRF/PRH, posterior; HR, head; FL, foot; RAF, right; LPH, left. (B) Images from a 17-year-old patient with unilateral renal agenesis and ipsilateral blind hemivagina syndrome who presented with a large haematocolpos. 1, i.v. pyelogram showing the right renal agenesis; 2, colpography of the right blind hemivagina filled with contrast agent. The transvaginal puncture allows the chocolate-coloured blood to drain, and the injection of a contrast agent permits the visualization of the blind vagina and fills the corresponding hemiuterus and tube in a retrograde manner, revealing potential inter-uterine communication at the level of the isthmus; 3, laparoscopic observation of an intraperitoneal bulging haematocolpos; 4, laparoscopic observation of the bicornuate uterus after drainage of the haematocolpos; 5, drainage of the haematocolpos; 6, observation of both hemivaginas and the vaginal septum. RBHV, right blind hemivagina.

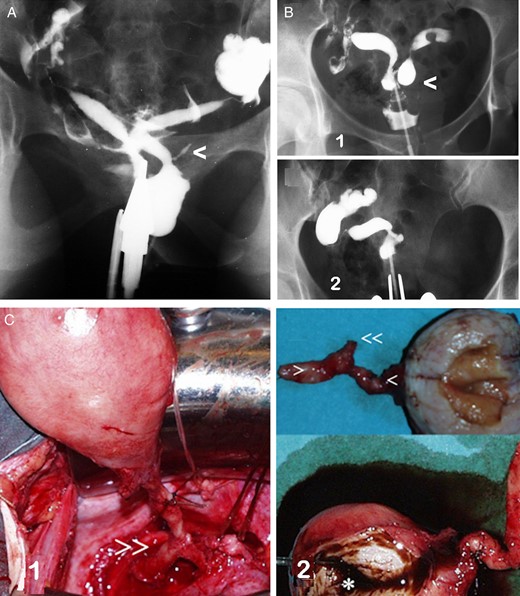

Cases of Gartner duct pseudocyst frequently have no symptoms other than fertility problems related to the bicornuate uterus. These cases are similar to those of Herlyn–Werner syndrome (Herlyn and Werner, 1971). Examination may reveal a cystic mass with the appearance of a Gartner cyst in the upper anterolateral wall of the vagina. This mass is actually an atretic blind hemivagina (Gadbois and Duckett, 1974). The corresponding hemi-cervix is usually atretic, and the examination and HSG can show a bicornuate-unicollis uterus with normal cervix and vagina (U3a/C0/V0 in the new ESHRE/ESGE classification system, 2013) due to communicating uteri. In other cases with the same hysterographic image, the atretic hemi-cervix is permeable and fistulous and communicates with the atretic blind hemivagina (Fig. 2). The predominant symptom is sudden leucorrhoea that is occasionally malodorous and that perhaps interferes with sexual intercourse. A wide resection of the vaginal septum resolves these symptoms (Acién and Acién, 2007; Pereira et al., 2014), and no other surgery is needed. In some cases, a hysteroscopic resection of the uterine septum (partial septate uterus) has been practiced and then an intrapartal rupture of obstructed hemivagina has occurred (Zivković et al., 2014). In other cases without communicating uteri, clinical presentation is similar to those that will be presented in ‘cases of complete unilateral cervicovaginal agenesis’ below, being the cause of repeated surgeries (Dorais et al., 2011). The existence of URA must be, again, the reason for suspecting and then confirming the right diagnosis.

Unilateral renal agenesis and ipsilateral cervicovaginal atresia with or without communicating uteri. (A) HSG image in a case with a mesonephric anomaly involving an apparent bicornuate-unicollis uterus in which the atretic left hemi-cervix is permeable, fistulous and communicating with an atretic left blind hemivagina. There was also left renal agenesis. This presentation corresponds to Herlyn–Werner syndrome (Herlyn and Werner, 1971). Moreover, a remnant of the mesonephric duct or ectopic ureter can be observed (<). (B) Images of a patient with primary infertility who was diagnosed with a genitourinary malformation (left cervicovaginal atresia and renal agenesis with communicating bicornuate uterus) and endometriosis. She underwent surgery in another hospital, where they performed a left hemi-hysterectomy, and an endometrioma in the left ovary was removed. 1, HSG image before surgery; 2, current HSG image. (modified with permission from Acién et al., 2004c); (C) images of a patient with unilateral cervicovaginal atresia and no communication between the two hemi-uteri. There was also right renal agenesis. After a right adnexectomy to treat tubo-ovarian and appendicular endometriosis was performed in another hospital, a large unilateral right haematometra developed, with severe clinical symptoms. 1, during the right hemi-hysterectomy, we identified what we thought was the mesonephric duct (>>); 2, surgical image showing the cervical and vaginal atresia (> and <) and the mesonephric remnant (<<) (modified with permission from Acién et al., 2004a).

Cases of partial reabsorption of the vaginal septum are similar to those of didelphys uterus with a double vagina, but typically, the vaginal septum does not reach the inferior third of the vagina, or a buttonhole is present on the lateral wall of the vagina that allows access to the genitalia on the side with ipsilateral renal agenesis (Acién and Acién, 2010). Heinonen (2006) reported 67 patients who had a complete septate uterus including the cervix and a longitudinal vaginal septum, finding 4 cases with an obstructed hemivagina causing unilateral haematocolpos. All of them also had ipsilateral renal agenesis. A fifth patient with URA and five more cases with a double ureter did not present obstructed hemivagina. No treatment is needed in these last cases unless there is dyspareunia, associated gynaecological pathology (leiomyomas) or obstetric complications. Malformations associated with URA (bicornuate and didelphys uterus) have fewer reproductive losses compared with the same uterine malformations without URA (Acién et al., 2014). However, Heinonen (2004, 2013a) reported a higher frequency of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia associated with URA in women with uterine malformations; one of our patients with right renal agenesis had thick varicosities on the surface of the left pregnant hemiuterus with vascular rupture and significant haemoperitoneum at 30 weeks gestation (Acién and Acién, 2007; Acién et al., 2014).

Cases of complete unilateral vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis, ipsilateral to the renal agenesis, can present with communication between both hemi-uteri, which behaves as a bicornuate-unicollis uterus (communicating uteri) as presented above (U3a/C0/V0 according to the ESHRE/ESGE classification system). The clinical presentation and management corresponds to that of bicornuate-unicollis uterus, although if the communication is limited, a hemi-hysterectomy might be required (Fig. 2B) because it has a better reproductive outcome than hysteroscopic widening of the communication. So, if the patient has a known URA, an ipsilateral vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis with a communicating bicornuate uterus must be suspected during the ultrasonographic finding of a bicornuate uterus and a gynecological exam showing normal vagina and cervix. HSG, or better MR, could confirm the diagnosis.

In other cases, there is no communication between the hemi-uteri. These patients present with a didelphys uterus with unilateral vaginal or cervicovaginal atresia and haematometra (or haematometra, haematocervix and haematosalpinx) as well as endometriosis caused by retrograde menstruation on the side lacking the vagina and kidney (Ruiz et al., 1999; Saleh and Badawy, 2010; Adair et al., 2011); the symptoms will worsen if the tube (or the adnexa, in cases of endometriosis) is removed or sectioned (Acién et al., 2004a; Dorais et al., 2011). Treatment includes a hemi-hysterectomy, which results in a unicornuate uterus (Fig. 2C). In some cases of unknown final diagnosis of the malformation, some authors have performed conservative treatment with a uterine unification procedure per-hysteroscopy and simultaneous laparoscopy (Dorais et al., 2011).

Therefore, patients with URA and ipsilateral blind or atretic hemivagina syndrome, after a proper diagnosis, may require only removal of the inter-vaginal septum and evacuation of the haematocolpos; a wide resection of this wall is potentially necessary for the Gartner duct pseudocyst type. A laparotomy, or laparoscopy if possible, will be necessary if there is a haematosalpinx or endometriomas. In fact, endometriosis is frequently associated with these malformations; within our URA patients (Acién and Acién, 2010) we found that 15% of cases (20% in case of bicornuate/didelphys uterus) had associated moderate or severe endometriosis against 7.4% of the control group of genital malformations with both kidneys present. Although in general, endometriosis disappears when the obstructive anomaly is corrected. Nevertheless, and even though no connection between a malformed uterus and ovarian neoplasm has been found (Woods et al., 1992; Heinonen, 2000), the published cases associating ovarian cancer and malformation were endometrioid ovarian carcinomas (Heinonen, 2000), as in one of our cases (52-year-old woman with a bicorne-bicollis uterus communicating at the cervical level, left blind hemivagina and left renal agenesis, with previously suspected endometriosis but not operated, and findings of endometrioid carcinoma of the left ovary and pelvic, right ovarian and appendicular endometriosis). Thus, we suspect that such endometriosis in patients with URA and blind hemivagina might have a higher risk of malignant transformation into ovarian endometrioid carcinoma.

In the case of a duplicate uterus (didelphys uterus) with unilateral cervicovaginal atresia, a hemi-hysterectomy must be performed (Lee et al., 1999; Acién et al., 2004a), and this operation can be conducted laparoscopically (Nawfal et al., 2011; Bolonduro et al., 2015). However, the presence of haematocolpos in a blind vagina proves that the cervix is not completely atretic and that the patient might become pregnant on that side (Nawfal et al., 2011). Obstetric complications are higher in such cases, but pregnancy can result in the delivery of a live infant (Heinonen, 2013a; Acién et al., 2014). If there is a dysplastic kidney with an ectopic ureter opening into the blind vagina, a nephrectomy and ureterectomy may be required (Acién et al., 1990). Removal of the ectopic ureter may also be necessary if it is associated with ascending infections and related problems, even if there is no detectable renal mass (Acién et al., 2004b).

In certain cases (Perino et al., 1995; Romano et al., 2000; El Saman et al., 2011a), hysteroscopic metroplasty has been performed with simultaneous abdominal ultrasound to evacuate and correct a ‘complete septate uterus with unilateral haematometra’. However, this appears to be of little benefit, particularly if the tube is occluded (Dorais et al., 2011), and this procedure might even worsen the perinatal results related to the uterine malformation. The need for other surgeries on the genital tract depends on the associated anomaly.

Cavitated and non-communicating uterine horns and other Müllerian atresias (complex isolated Müllerian anomalies) (7.3% of all FGTM)

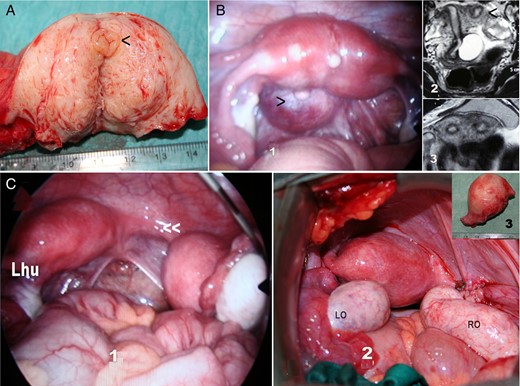

Some cases of unicornuate uterus include a cavitated and non-communicating uterine horn with external bicornuate uterine morphology. The inclusion of these cases as bicornuate or unicornuate uterus is discussed. Functionally, these uteri are unicornuate, but it is important to adequately identify the anomaly to determine whether there is renal agenesis and to decide whether surgical correction is required. The HSG image indicates a unicornuate uterus, but ultrasound, and particularly MR, can properly identify the cavitated uterine horn (Fig. 3). Patients may experience dysmenorrhea and present with endometriosis and ovarian endometriomas in the non-communicating horn side, but sometimes, there are no symptoms or adnexal pathology. In one of our studied cases (see Fig. 3B), the patient had a left retrocervical subperitoneal cyst, a Müllerian remnant, that was excised. In another case, severe symptoms appeared after bilateral tubal sterilization following several uneventful pregnancies (Acién and Acién, 2007). Tubal blockage of the side with the cavitated and non-communicating horn led to unilateral haematometra with severe dysmenorrhea. In other cases, there can be gestation in the cavitated rudimentary horns (communicating or not) with possible uterine rupture, usually at the end of the second trimester (Dhar, 2012). Management usually involves excision of the cavitated rudimentary horn, and this can be conducted laparoscopically (Fedele et al., 2005; Lennox et al., 2013). However, there is no basis for the exeresis of a non-functioning rudimentary horn to treat infertility or miscarriages (Buttram and Reiter, 1987).

Cases with a cavitated and non-communicating uterine horn. (A) Surgical image of hemi-hysterectomy showing an endometrial cavity (<); (B) another case with a cavitated and non-communicating uterine horn: 1, laparoscopic image of an apparently normal or very slightly arcuate uterus with normal adnexa, and a left retrocervical subperitoneal serous cyst (>) corresponding to a Müllerian remnant. 2 and 3, MR of the same case showing the left cavitated and non-communicating rudimentary uterine horn (<). Due to the absence of symptoms, only the cyst was excised. (C) Case with a left unicornuate uterus and proximal segmentary atresia of the right horn. 1, Laparoscopic image showing the right atretic uterine segment (<<) with a normal and cavitated distal uterine segment and normal right adnexa; 2, a right hemi-hysterectomy was performed and the rudimentary horn with haematometra is shown in 3.

In some cases of unilateral haematometra, particularly in certain cases of hybrid bicornuate/septate uterus, a hysteroscopic resection of the intermediate septum between the normal uterine horn and the cavitated and non-communicating horn has been conducted (Hucke et al., 1992; Dorais et al., 2011; El Saman et al., 2011a). However, we do not believe there is a basis for this procedure, particularly if the tube on the haematometra side is occluded (Dorais et al., 2011); besides the risks of a pregnancy in the rudimentary horn, the remaining bicornuate uterus has no better reproductive results (Acién, 1993,, 1996; Acién et al., 2014). Nevertheless, a cavitated and non-communicating horn with haematometra can also occur in cases of a septate uterus. These cases of a Robert's uterus or asymmetric septate uterus were first reported by Robert in 1970 (Robert, 1970; Benzineb et al., 1993; Gupta et al., 2007). Pregnancy in the asymmetric blind hemi-cavity of a Robert's uterus has also been noted (Singhal et al., 2003), but some reported cases of menstrual retention in a Robert's uterus (Capito and Sarnacki, 2009) might correspond to accessory and cavitated uterine masses (ACUMs) (Acién et al., 2012), which will be explained below. The hysteroscopic unification of a complete obstructing uterine septum (Spitzer et al., 2008) in a 16-year-old woman with severe, persistent dysmenorrhea and a history of significant endometriosis has also been presented and discussed. Recently, Di Spiezio Sardo et al. (2015b) have reported ‘an exceptional case of complete septate uterus with unilateral cervical aplasia (formally Robert's uterus) and combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic treatment’. However, there is no explanation on which grounds ‘unilateral cervical aplasia’ is diagnosed, or if the patient had ipsilateral renal agenesis.

In cases of segmentary atresias of one of the Müllerian ducts with a detached horn or hemiuterus, HSG reveals a unicornuate uterus, but ultrasound and MR show a didelphys uterus in the superior uterine segment with a unilateral cavitated and non-communicating uterine horn. The cervix is simple. Generally, there is dysmenorrhea and endometriosis due to retrograde menstruation from the cavitated uterine horn, but there can also be tubal segmentary atresia, and in such cases, there will be haematometra without endometriosis (Acién et al., 2008a). In all cases, a differential diagnosis must be determined, especially in cases of complete unilateral vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis without communicating uteri (Acién et al., 2004a, 2004c; Medeiros et al., 2011). Excluding these last cases, which are systematically associated with renal agenesis, both uterosacral ligaments end in the single cervix in cases of Müllerian segmentary atresia, as observed during laparoscopic observation. Regardless, the appropriate treatment is a hemi-hysterectomy, preferably performed laparoscopically (Fedele et al., 2005; Theodoridis et al., 2006; Caserta et al., 2014).

Vaginal or cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia with a functional uterus. This is usually a complex malformation in which the external genitals and tubes appear normal. The uterus may be normal or may present with fusion or resorption defects, and the cervix may be present, absent or hypoplastic (Grimbizis et al., 2004; Sparac et al., 2004). In our experience, the most common presentation, although rare, is complete cervicovaginal atresia or agenesis. The clinical presentation involves primary amenorrhoea and cyclic pain in postpubertal women. Upon gynaecological exploration, normal external genitalia and the absence of a vagina are evident. Transrectal ultrasound, and particularly MR, allows a clear diagnosis that includes a largely normal corpus uteri with endometrium and cervicovaginal atresia. The ovaries are normal, although they might present with endometriosis due to retrograde menstruation, and haematometra may be present, unless previous interventions have been undertaken or other Müllerian anomalies have been identified. A very large abdominal mass due to haematometra with severe anaemia has been reported previously (Opoku et al., 2011).

Surgical methods for the treatment of congenital anomalies of the uterine cervix have included creating a fistula endometrium-vagina with polyethylene or rubber tubes, and some published cases did achieve menstruation. However, pregnancies were rare, and hysterectomy was typically required (Geary and Weed, 1973; Rock et al., 1984). Nevertheless, there are also published cases reporting successful gestation (Deffarges et al., 2001).

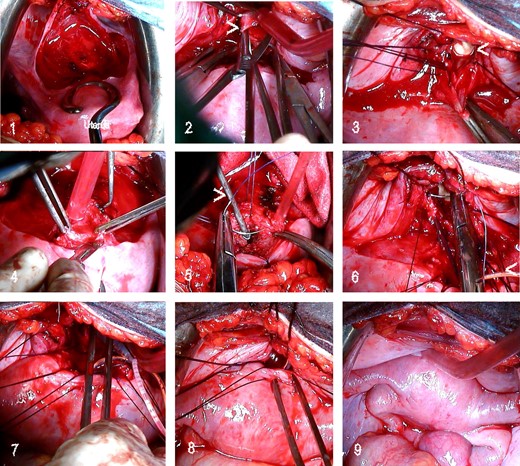

If the uterus and/or tubes also present malformations or other alterations associated with low reproductive capacity despite the successful creation of a neovagina, an elective hysterectomy is frequently recommended, even for young patients (Roberts and Rock, 2011). However, when only cervical agenesis is present (Rock et al., 2010; Roberts and Rock, 2011), reimplantation of the cavitated uterine corpus in the vagina (after atretic cervix removal) has been attempted and has achieved normal menstruation and pregnancy. We have performed reimplantation of the uterine corpus in the neovagina (in some cases with complete cervicovaginal agenesis) and have achieved normal menstruation for years and spontaneous gestation at term (Acién et al., 2008b). We first create the neovagina following the McIndoe technique, and 3–4 months later, a laparotomy with atretic cervix resection and reimplantation of the uterine corpus in the neovagina is conducted; a Foley catheter is placed in the uterine cavity to allow antibiotic and anti-inflammatory irrigation during the subsequent month. Figure 4 presents the surgical steps in one of our patients. Currently, this surgery is being performed laparoscopically with or without a stent (self-expandable metallic or silicone stent: Zhou et al., 2013; Gore-Tex: Rezaei et al., 2015) by certain groups, but the long-term follow-up results are not good because after some months blood retention re-occurs or there is ascending infection and a hysterectomy is needed. Thus, we continue to recommend the laparotomic approach.

Sequence of utero-neovaginal anastomosis in a 21-year-old patient with primary amenorrhoea and cyclic pelvic pain since 16 years of age. Following a diagnosis of complete cervicovaginal atresia with normal corpus uteri and ovaries, she underwent a McIndoe neovagina procedure; after 3–4 months, we performed a laparotomy with utero-neovaginal anastomosis. 1, Bladder dissection; 2, neovaginal fundus opening (>); 3, fixing sutures to open the neovagina. Note the prosthesis in the vagina (<). 4, removal of the atretic cervical portion and resection of the inferior portion of the uterine corpus; 5, hysterometre (>) inserted in the uterus and the beginning of stitches in the myometrium (uterus flipped back); 6, suturing of the corpus uteri to the neovagina; Foley catheter in the uterus (<); 7, Foley catheter introduced into the endometrial cavity and extracted via the vagina; 8, anterior suture of the corpus uteri to the neovagina; 9, final result.

If the uterus and cervix are normal, the surgical correction depends on the atretic vaginal segment. If the distance between the blind vaginal bag and the superior portion of the permeable vagina is short, vaginal anastomosis can be performed. Jeffcoate (1969) recommended waiting until a significant superior haematocolpos forms to enable facile penetration of the superior portion of the vagina and to allow adequate vaginal epithelium lining to form before the anastomosis.

If the atretic segment is larger and the area between the superior and inferior portions of the vagina is large and fibrous, or if the atresia affects the entire vagina, the formation of a neovagina must be considered, and the use of an inert material prosthesis and a skin graft is preferable (McIndoe vaginoplasty). The neovagina must be made early in life (at 13–14 years of age) to avoid pelvic menstrual retention and endometriosis. However, if a hysterectomy is required because of associated pathology, the creation of the neovagina must be postponed until 18–20 years of age, when surgery is technically easier and can be safely followed by sexual intercourse, the patient is more mature, and vaginal dilation, as the first choice, fails (Callens et al., 2014). Recently, several papers have been published on laparoscopic-assisted uterovaginal anastomosis. Kriplani et al. (2012) performed the procedure in 14 patients with a silicone tube placed as a stent in the congenital cervical atresia; in 9 patients with associated vaginal aplasia, a modified McIndoe vaginoplasty was performed concomitantly. One patient underwent a hysterectomy, and pregnancy was achieved in three patients. Kisku et al. (2014b) performed a laparotomy with sigmoid neovaginoplasty followed by utero-coloneovaginoplasty in 20 patients. Additionally, Ding et al. (2014) published their experience with a combined laparoscopic and vaginal cervicovaginal reconstruction using an acellular porcine small intestinal submucosa graft during the end of menstruation in eight patients. A T-shaped intrauterine device connected to a Foley catheter was inserted into the uterine cavity, and a permanent lower uterine cerclage was subsequently placed. All the patients resumed menstruation without complications at 8 ± 4 months of follow-up.

In cases of complete vaginal atresia, we usually follow the same technique as for cervicovaginal agenesis or atresia.

Vaginal segmentary atresia/transverse vaginal septum. This corresponds to a short segmentary atresia of the vagina that may completely or partially obliterate it and/or to a transverse constriction or septum that is perforated or imperforated. In the first case, the atresia presents as annular stenosis, sometimes sufficiently narrow that it causes menstrual retention, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia or, most likely, soft-tissue dystocia upon delivery (Bautista-Gomez et al., 2012). Vaginal Z-plasty can be performed.

A complete or imperforated transverse vaginal septum can present in young girls as a hydrometrocolpos that produces several complications derived from compression (Spencer and Levy, 1962; Nguyen et al., 1984; Hahn-Pedersen et al., 1984). In other cases, there may be no symptoms until puberty, when the haematocolpos forms and causes episodes of pelvic pain and primary amenorrhoea similar to those observed with vaginal atresia. This condition requires early surgery, and generally, vaginal anastomosis is possible after evacuation of the superior haematocolpos (Moura et al., 2000; Breech and Laufer, 2009). Some patients may require abdominoperineal vaginoplasty or more extensive surgery to treat complex septae that carry an increased risk of complications (Williams et al., 2014). Ugur et al. (2012) reported their positive experience with 11 patients with distal vaginal agenesis who were managed with interposition of a full-thickness skin graft to bridge the gap between the upper vagina and the introitus after placement of an inflatable silicone stent. El Saman et al. (2011b) have also proposed and performed an outpatient balloon vaginoplasty for treatment of vaginal aplasia.

The cases of agenesis and uterine hypoplasias (Group I of the ASRM classification) include cases of vaginal and cervical agenesis (Rock et al., 1984) with a functioning endometrial cavity as well as cases of uterine fundal or corporal agenesis. In these latter cases, except those with an indication of uterine transplantation in the near future (Brännström et al., 2010, 2014, 2015; Akar and Erdogan, 2013), there is no surgical indication or treatment available for this very rare anomaly. However, combined uterovaginal agenesis is more common and represents the most common type of Müllerian agenesis; it is related to MRKH or Rokitansky syndrome (Oppelt et al., 2006, 2012; Pizzo et al., 2013; Bombard and Mousa, 2014), which is described as an isolated Müllerian malformation affecting both the Müllerian ducts and the Müllerian tubercle (Acién and Acién, 2007, 2011). From the point of view of the differential diagnostic and clinical management, the complete androgen insensivity syndrome (CAIS) patients (phenotype female, absence of female internal genitalia, male karyotype and eventual inguinal hernia with functional testes) must be taken into account (Konar et al., 2015), as well as some urogenital sinus anomalies that will be later analysed, and certain cases of Rokitansky syndrome with associated 46,XX gonadal agenesis or dysgenesis. An exact diagnosis is stressed before adequate treatment.

Rokitansky or MRKH syndrome is usually not included within the complex malformations of the female genital tract because primary amenorrhea is the only symptom. However, there are potentially other associated urinary or extragenital malformations (Oppelt et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2007; Acién et al., 2010c; Yoo et al., 2013), and some patients present with one or both cavitated rudimentary horns, leading to classification as a complex malformation (Fig. 5). MR evaluation of the Müllerian remnants and haematomas or endometriomas is the most important diagnostic tool (Yoo et al., 2013). All typical uterine tissues can be found in these uterine rudiments, and the expression of hormone receptors does not differ significantly compared with normal controls, but interestingly the endometrium shows predominantly basalis-like features (Rall et al., 2013). However, Müllerian segmentary anomalies displaying features such as uterine malformation (atretic bicornuate uterus, one of them cavitated) and transverse vaginal septum (Jain et al., 2013) could also be included in this group of complex malformations.

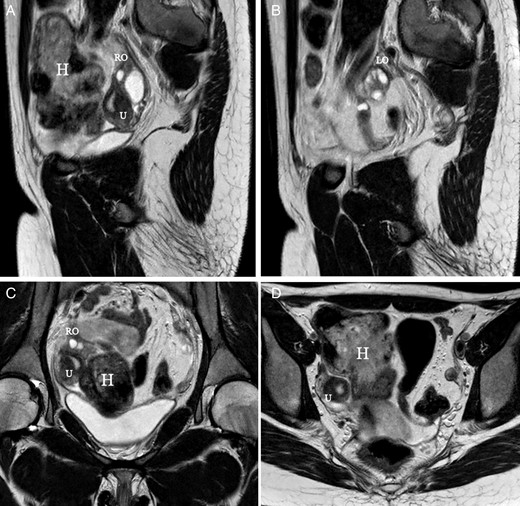

MR images corresponding to a 17-year-old patient with Rokitansky syndrome. She had a right cavitated rudimentary uterine horn with retrograde menstruation and pelvic haematomas (H). (A, B) Saggital cuts; (C, D) axial cuts. U, uterus, cavitated horn. RO, right ovary. LO, left ovary.