-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Olli Paakkari, Markus Kulmala, Nelli Lyyra, Terhi Saaranen, Pirjo Lindfors, Heli Tyrväinen, The core competencies of a health education teacher, Health Promotion International, Volume 39, Issue 4, August 2024, daae078, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daae078

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Teachers play a crucial role in students’ learning and in the development of health literacy. Hence, the aim of this study was to identify the core competencies needed for teachers of health education in supporting student learning. A three-round Delphi study was carried out over an 8-week period, through consultation with 25 Finnish experts in health education. An open-ended question was used to identify the core competencies for school health educators. The data were analysed using inductive content analysis. In subsequent rounds, experts were asked to assess the importance of the identified competencies on a 7-point Likert scale, and finally to rank the most important competencies. In total, 52 competencies were identified and categorized into eight core competence domains. Thereafter, 40 competencies were assessed and selected for the third round, in which the experts ranked the 15 most important competencies, encompassing four core domains, i.e. pedagogic and subject-specific didactic, social and emotional, content knowledge and continuous professional development. Other domains of competence identified in the present study were ethical competence, competence in school health promotion, contextual competence and professional well-being competence. The study defines health education teacher core competencies and domains, and the information can be used in teacher education programmes, for developing teaching and for teachers’ self-evaluation.

Competent health education teachers can have a significant impact on students’ health literacy.

This study identifies the extensive list of competencies needed for teachers of health education.

The results of the study can be used to build competence-based curricula and guide the development of future health education teacher education programmes.

BACKGROUND

Teaching is a complex and demanding profession that requires a wide range of expertise. Teachers form one of the key factors in students’ learning and academic achievement (Hattie, 2009), but there are differences between teachers (Stronge et al., 2007; Hattie, 2009). Competent teachers influence the quality of teaching and thus student learning, and various explanations of these chains of effects have been offered (Fauth et al., 2019; Blömeke et al., 2022). The importance of teachers’ work for students’ learning and development places high demands on teachers’ initial training and on continuous professional development. From the perspective of health education (HE) teacher training, it is critical to take a holistic view of the teacher’s work and to consider the competencies that teachers need to succeed in their profession. This broad understanding of the teacher’s profession is fundamental, and relevant factors can also support teachers in constructing strong professional identities. There is thus a need for a conceptually coherent framework of teacher competencies, based on knowledge of teaching and learning, and taking into account the complexity of the teacher’s work (Grossmann and McDonald, 2008).

One key aspect relevant to identifying HE teacher competencies is that the school reaches almost the whole age group at any given time. It thus offers an excellent opportunity to develop health literacy, regardless of the individual’s background (Paakkari and Paakkari, 2012). Health literacy has been found to be a constitutive determinant for health across age groups (Berkman et al., 2011; van der Heide et al., 2016; Paakkari et al., 2020), and low health literacy has been identified as an independent risk factor (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow, 2007). Among children and adolescents, health literacy has emerged as an independent factor explaining health disparities, with higher health literacy being related to more positive health outcomes (Paakkari et al., 2019a). Thus, competent HE teachers have the possibilities to benefit a nation’s health, while providing quality education for future adults (St Leger and Nutbeam, 2000).

Internationally, HE in schools is organized in diverse ways. HE can be an independent and obligatory school subject taught by teachers with a degree in the subject, or health topics may be integrated within other school subjects. Regardless of how HE is organized, it is essential for the development of the subject and for students’ learning that teachers have sufficient competence. A conceptually coherent competence framework can provide a basis for relevant and versatile teachers’ competencies, allowing them to perform well in different contexts.

The concept of competence is characterized by controversy, ambiguity and contradiction (Schneider, 2019), and there is variation in key constructs and domains, depending on scientific and academic disciplines and education, and policy cultures across countries (Caena, 2014). Competence can be defined as the capability to perform tasks, as a learnable and contextualized disposition, as a process, as a relation between abilities and the completion of a task, as a quality or state of being or as a behaviour integrating resources (Schneider, 2019). It is a combination of attributes such as knowledge, skills, dispositions and attitudes (Hager and Gonczi, 1996; European Commission, 2013; Blömeke et al., 2015) which construct the ability to successfully perform domain (subject) task-specific actions (Blömeke et al., 2015; Schneider, 2019). In this article, the concept encompasses the professional demands related to the functions, responsibilities and roles of the HE teacher in the subject-specific context.

The literature on the core competencies of teachers contains studies examining the general competencies needed in the work of a teacher, as well as studies from the perspective of more specific contextual requirements. Topic- or subject-specific competencies have been defined for teachers in various domains, including sustainable development (Lohman et al., 2021), digital competence (European Commission et al., 2017), collaborative learning (Kaendler et al., 2015), sexuality education (World Health Organization, 2017) and science (Nouri et al., 2021).

An interest in holistic, dynamic and process-oriented approaches has increased within research on teacher competencies (Caena, 2014; Metsäpelto et al., 2021). Competence development processes and transformation into performance can be viewed as personally, situationally and socially determined (Blömeke and Kaiser, 2017). All higher education graduates need generic competencies, such as conceptual skills (e.g. problem-solving, thinking skills, creativity, information processing), social skills (e.g. communication, teamwork, leadership) and personal skills (e.g. lifelong learning, critical reflection, social responsibility) (Strijbos et al., 2015). It has been suggested that the competencies common to all teachers include well-structured knowledge of education theories and curricula, solid knowledge on how to teach specific subjects, classroom management strategies and skills, reflective and research skills (including a commitment to professional development), collaborative skills and the ability to adapt to different situations within schools (European Commission, 2013; Caena, 2014).

On the basis of previous studies (e.g. Shulman, 1987; Baumert and Kunter, 2013; Blömeke et al., 2015; Blömeke and Kaiser, 2017; Klassen and Kim, 2019), Metsäpelto et al. (2021) constructed a multidimensional adapted process model of teaching (MAP model); this identifies the relevant competence domains and is applicable to teachers in a wide range of teaching professions and school subjects. The MAP model refined the competencies of Blömeke et al.’s (2015) model, framing them as observable teaching practices. The MAP model emphasizes the situation-specific skills of perceiving, interpreting and making decisions, teaching and professional practices as indicators of teaching competencies. In addition, the MAP model contains a set of individual competencies. These consist of possession of the knowledge base, cognitive thinking skills, social skills, personal orientations and professional well-being (Metsäpelto et al., 2021).

There has been relatively little research on the specific competencies of HE teachers. The empirical study of Moynihan et al. (2015) aimed to identify HE teachers’ core competencies in supporting the development of health literacy. The study identified 12 competencies, divided into three overlapping competence domains: knowledge (about curricula, health determinants, learners, HE theories and models, general pedagogical knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge), skills (communication, ethical thinking, researching, planning and implementing initiatives) and attitude. Similarly, the theoretical framework of Szucs et al. (2021) describes knowledge and skills as core competence domains for teachers delivering HE; however, the third competence domain is that of personal characteristics (e.g. an academic degree in HE, confidence, beliefs, cultural responsiveness and humility, a sense of equity). The knowledge domain encompasses five categories (learner characteristics and development, pedagogical knowledge, subject content knowledge, professional standards), while the essential skills domain includes learning environments, content and delivery and collaboration and learning (Szucs et al., 2021). In addition to these studies, there are some national (USA) guidance documents aiming to standardize HE teacher competencies (National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, 2002; Society for Health and Physical Educators, 2018).

Based on the paucity of previous empirical studies and the fact that HE teachers’ voices were not taken into account in the studies in question, the present study aimed to identify and describe competencies relevant to HE teachers’ work. It is envisaged that the results of the study could be used in the development of HE teacher education.

METHODS

A Delphi approach was utilized in this study, with three survey questionnaire rounds over an 8-week period in 2022. The Delphi method has been considered appropriate in cases where research-based knowledge of the topic is scarce (Jünger et al., 2017). In this method, in which both qualitative and quantitative processes are used, selected expert panel members give individual opinions, the aim being to generate a consensus opinion based on these views (Nasa et al., 2021). The key principles of the process are anonymity, an iterative questionnaire procedure and controlled feedback (Jünger et al., 2017; Staykova, 2019; Nasa et al., 2021). The rationale for anonymous responses is the avoidance of social pressure that would produce conformity to a dominant view (Jünger et al., 2017). In a similar vein, there were no feedback discussions in the present study, since these can affect individuals’ responses and create a biased consensus (Barrios et al., 2021). After each survey round, the data collected were analysed and presented to the expert panel in the form of another questionnaire, presented in the next round.

In the present study, the Delphi rounds were conducted via online questionnaires, with the anonymity of the responses secured. The questionnaire for each round was pre-tested by external researchers and by teachers with experience in the field of the study. Based on their comments, minor changes were made to the questionnaires. The participants received general information on the process of the study via email between the rounds.

Participants

One of the most important steps in a Delphi study is the selection of the panel members, i.e. experts (Green et al., 1999). Adequate heterogeneity of panel members helps to provide a broader picture of the phenomenon under study. There is no precise definition of the size of an expert panel; in fact, panels typically range from 10 to 100 members, and in the health sciences, 20–50 members are deemed sufficient for a Delphi study (Niederberger and Spranger, 2020; Nasa et al., 2021). What matters in a Delphi study is the expertise and representativeness of the experts, rather than the number of panellists (Staykova, 2019). Bearing in mind the complexity of the phenomenon under study (teacher competencies), the study aimed to achieve a comprehensive picture of the subject. A sufficiently large number of experts from different backgrounds can increase the diversity of the responses and the possibilities to generalize results (Nasa et al., 2021). For these reasons, this study aimed at a panel size greater than the minimum number, i.e. a medium double-digit range typically used in Delphi studies (Diamond et al., 2014; Niederberger and Spranger, 2020; Nasa et al., 2021). The selection of experts was based on pre-defined criteria (Jünger et al., 2017; Nasa et al., 2021). These criteria included appropriate education and an academic degree in HE, relevant expertise with long experience in the subject and an active role in the development of HE. A pre-selected list of 29 HE experts was formulated based on the criteria, and these experts were invited to participate in the study. All the experts were contacted personally to explain the purpose and method of the study. In total, 25 experts (all from Finland) agreed to participate in the study (Table 1).

| . | . | Round 1 n = 25 n (%) . | Round 2 n = 23 n (%) . | Round 3 n = 24 n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 (24) | 6 (26) | 5 (22) |

| Female | 19 (76) | 16 (70) | 19 (78) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Years of work in health education | Mean | 19.7 | 19.5 | 18.6 |

| Median | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| SD | 6.4 | 7.3 | 6.2 | |

| Highest degree obtained | Master’s | 16 (64) | 13 (57) | 14 (61) |

| PhD | 9 (36) | 10 (43) | 10 (39) | |

| Pedagogical studies for teachers (60 ECTS) | Yes | 25 (100) | 23 (100) | 24 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (0) | |

| Professional title | Lecturer in comprehensive school, upper secondary school or vocational education | 10 (40) | 7 (30) | 8 (30) |

| Lecturer in teacher education or university teacher | 10 (40) | 13 (57) | 12 (52) | |

| Professor | 2 (8) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) | |

| Other | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 2 (9) |

| . | . | Round 1 n = 25 n (%) . | Round 2 n = 23 n (%) . | Round 3 n = 24 n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 (24) | 6 (26) | 5 (22) |

| Female | 19 (76) | 16 (70) | 19 (78) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Years of work in health education | Mean | 19.7 | 19.5 | 18.6 |

| Median | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| SD | 6.4 | 7.3 | 6.2 | |

| Highest degree obtained | Master’s | 16 (64) | 13 (57) | 14 (61) |

| PhD | 9 (36) | 10 (43) | 10 (39) | |

| Pedagogical studies for teachers (60 ECTS) | Yes | 25 (100) | 23 (100) | 24 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (0) | |

| Professional title | Lecturer in comprehensive school, upper secondary school or vocational education | 10 (40) | 7 (30) | 8 (30) |

| Lecturer in teacher education or university teacher | 10 (40) | 13 (57) | 12 (52) | |

| Professor | 2 (8) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) | |

| Other | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 2 (9) |

| . | . | Round 1 n = 25 n (%) . | Round 2 n = 23 n (%) . | Round 3 n = 24 n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 (24) | 6 (26) | 5 (22) |

| Female | 19 (76) | 16 (70) | 19 (78) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Years of work in health education | Mean | 19.7 | 19.5 | 18.6 |

| Median | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| SD | 6.4 | 7.3 | 6.2 | |

| Highest degree obtained | Master’s | 16 (64) | 13 (57) | 14 (61) |

| PhD | 9 (36) | 10 (43) | 10 (39) | |

| Pedagogical studies for teachers (60 ECTS) | Yes | 25 (100) | 23 (100) | 24 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (0) | |

| Professional title | Lecturer in comprehensive school, upper secondary school or vocational education | 10 (40) | 7 (30) | 8 (30) |

| Lecturer in teacher education or university teacher | 10 (40) | 13 (57) | 12 (52) | |

| Professor | 2 (8) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) | |

| Other | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 2 (9) |

| . | . | Round 1 n = 25 n (%) . | Round 2 n = 23 n (%) . | Round 3 n = 24 n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 (24) | 6 (26) | 5 (22) |

| Female | 19 (76) | 16 (70) | 19 (78) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Years of work in health education | Mean | 19.7 | 19.5 | 18.6 |

| Median | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| SD | 6.4 | 7.3 | 6.2 | |

| Highest degree obtained | Master’s | 16 (64) | 13 (57) | 14 (61) |

| PhD | 9 (36) | 10 (43) | 10 (39) | |

| Pedagogical studies for teachers (60 ECTS) | Yes | 25 (100) | 23 (100) | 24 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (0) | |

| Professional title | Lecturer in comprehensive school, upper secondary school or vocational education | 10 (40) | 7 (30) | 8 (30) |

| Lecturer in teacher education or university teacher | 10 (40) | 13 (57) | 12 (52) | |

| Professor | 2 (8) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) | |

| Other | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 2 (9) |

In aiming to define the teacher’s competencies, it is important to take into account the authentic challenges of a HE teacher’s work. In this study, the panellists included experienced teachers and teacher trainers with an understanding of the different aspects of a teacher’s work. This was done to ensure that the study would be maximally applicable to HE teacher education and teacher competence development.

Invitations were issued to teacher trainers from each of the Finnish universities providing teacher training in HE, and to experienced HE teachers working at different school levels. The experts had diverse educational backgrounds and competence in areas such as teacher education, health promotion, management, health organizations and research. The panellists included people who had been active in the development of teaching; also those who had built the theoretical basis of the subject, been involved in the matriculation examination board, produced learning materials and HE textbooks, developed national and local curricula and reformed assessments.

Delphi procedure

In the first round, the experts were given the opportunity to freely detail competencies they deemed relevant to a HE teacher’s work. Open-ended questions were framed: ‘What do you consider to be relevant competencies in HE teachers’ work? Name and describe in detail as many competencies as possible’. The study researchers performed inductive content analysis on the answers (Kyngäs, 2020). As a first step, the data (i.e. the experts’ responses) were carefully reviewed and read through multiple times by the researchers. Some of the longer expressions were slightly condensed, while ensuring that the idea still corresponded to the raw data. Thereafter, individual similar or identical original expressions were combined, leaving a comprehensive list of all the competencies mentioned in the experts’ answers. Finally, content similarities and differences were compared to determine which competencies could be grouped together. The main categories emerged from the shared content of the group. The researchers named the categories, applying their expertise and theoretical understanding. Any disagreements or discrepancies were resolved by open discussion to reach a final consensus. The experts’ expressions were followed closely in constructing the items for the second-round questionnaire.

In the second round, experts were asked to evaluate the importance of the competencies identified in the first round, using a 7-point Likert scale. The scale ran from 1 = not at all important to 7 = very important. The most important competencies for inclusion in the third-round questionnaire were selected, applying four criteria and pre-defined cut-off values (Nasa et al., 2021) as follows: 5 for the median, 2 for the interquartile ranges (IQRs), 60% for the proportion of respondents who gave a rating of at least 6 on the Likert scale, and 22% for pairwise agreement (twice the agreement compared to a situation in which the respondents rated the item as maximally different). The pairwise agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreeing pairs of raters by the number of all possible pairs in the dataset.

According to systematic reviews, in Delphi studies a consensus is commonly defined on the basis of the percentage of agreement, the central tendency (the median in this study), or a combination of these (Diamond et al., 2014; Jünger et al., 2017). However, the definition of an appropriate agreement percentage varies widely and is to some extent arbitrary, given that there are no clear guidelines or commonly accepted criteria for determining a consensus (Diamond et al., 2014; Jünger et al., 2017; Nasa et al., 2021). In addition to the values typically used to describe a consensus (percentage of agreement, central tendency), two other values were used in this study. These were intended to provide more diverse information on the variation between respondents, and in this way provide more evidence that an appropriate consensus had been reached.

In setting cut-off values for the study, the aim was to ensure that the key issues were reliably selected from the data. Hence, cut-off values of 2 for the IQR and 22% for pairwise agreement were chosen, so that the pool of competencies would be limited to those displaying less variability between raters. The IQR range was preferred to the raw first and third quartiles, since it captures the amount of variability more concisely. To ensure that all the competencies were deemed highly important, it was decided that, for any given competency, at least 60% of the respondents should give it a rating of at least 6 on the Likert scale. These values were based on the best judgement of the research group, because there is no clear research-based guidance on the exact threshold values or on the range of these values.

In the third round, the experts were asked to select and rank the top 15 competencies from the list generated in the second round. The most important item received the highest value, i.e. 15, and the least important item the value of 1. Items outside the list of the 15 most important items received a value of 0. Based on this, a rank sum was calculated. Agreement among the experts was examined via the pairwise agreement, the proportion of experts who ranked a certain competence as being among the 15 most important items, and Kendall’s concordance coefficient W; the latter measures the agreement among raters, and takes values between 0 and 1, with 1 representing total agreement between raters. The applied critical values (although by nature arbitrary) were, as presented in Landis and Koch (1977), as follows: for Kendall’s concordance, a coefficient W of 0.00 ≤ W < 0.20 indicates slight agreement, 0.20 ≤ W < 0.40 fair agreement, 0.40 ≤ W < 0.60 moderate agreement, 0.60 ≤ W < 0.80 substantial agreement and W ≥ 0.80 almost perfect agreement. The pairwise agreement was calculated by first categorizing the data into groups composed of five ratings plus the group of 0 (0, 1–5, 6–10, 11–15) and then dividing the number of agreeing pairs by the number of all possible pairs in the dataset.

The present Delphi study consisted of three rounds, as described above. Traditionally, a Delphi study is thought to require at least four rounds (Nasa et al., 2021), but systematic reviews have shown that the majority of studies have used either two or three rounds, with the number of rounds varying from one to five (Diamond et al., 2014; Jünger et al., 2017). On this basis, it was anticipated that the current study would involve three to four rounds, depending on the degree of consensus achieved. Controlled feedback, presented to the expert panel in the form of another questionnaire in the next round, could support consensus building and thus reduce the number of rounds needed. When the pre-defined criteria with the chosen cut-off values were met, it was concluded that three rounds were sufficient to achieve a reliable result.

Ethics

This study followed the ethical principles of research with human participants (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity, 2019), and the research was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Active consent was obtained from all participants at each stage of data collection. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, its design, the anonymous response and the voluntary nature of participation. Data privacy was implemented appropriately.

RESULTS

First and second round

In the first Delphi round, experts produced in total 343 expressions describing competencies. Using content analysis, 52 competencies were rephrased from the data as a sentence with concrete examples, and categorized into eight core competence domains (Table 2). The largest domain (n = 19) was Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence; this refers to classroom management, planning, instruction, assessment (in general and from a subject-specific perspective), plus understanding the cognitive, motivational and emotional factors that regulate students learning. The second largest domain, Social and emotional competence (n = 9) refers to the teacher’s ability to relate to other people; it includes being aware of one’s own and others’ emotions, regulating a supportive emotional atmosphere, and respecting diversity. The domain of Content knowledge (n = 3) encompasses teachers’ knowledge of key concepts, facts, theories and phenomena in the subject area, plus comprehension of the structure of the subject and how this knowledge is generated. Ethical competence (n = 5) emphasizes the teachers’ ability to commit to professional ethics, to assess and justify their work from an ethical perspective, to solve ethical problems in the school and to reflect on their own values, attitudes and principles, including the consequences ensuing from them.

Core competence domains and a list of competencies based on content analysis from the first Delphi round, arranged within the domains according to the consensus criteria used in the second Delphi round (median, IQR with first and third quartiles, pairwise agreement and proportion with value 6 on a Likert scale 1–7)

| Core competence domain . | Competencies . | Median . | Proportion % ≥ 6 . | Q1 . | Q3 . | IQR . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence | Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively (planning-implementation-assessment and impact of choices made at these stages on each other) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 48 |

| Ability to design logically-progressing educational modules and individual lessons according to the curriculum (health literacy, objectives, content), taking into account students and groups | 7 | 95.7 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 63 | |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 7 | 95.7 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 58 | |

| Group management skills | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Skill to give feedback to the student | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Assessment competence (e.g. skills to design and implement criteria-based and ethically sustainable diagnostic, formative and summative evaluation, targeting of evaluation) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Situation-specific competence in lessons (e.g. observation, interpretation, decision-making in learning, flexibility, ability to change activities in a teaching situation if appropriate) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 43 | |

| Ability to take into account the specific characteristics of the subject in learning situations (e.g. the personal nature of the contents, cultural ties, sensitivity) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Teaching skills, encompassing the ability to use various learning environments (including authentic and digital environments), working methods, and learning materials; also the ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters as required | 7 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills (e.g. versatile information-processing) | 7 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 37 | |

| Knowledge of students and groups (e.g. health behaviour, growth and development, youth cultures, background/growth environment, prior knowledge of the subject to be taught, concerns), plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 7 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 36 | |

| Knowledge of the general and subject-specific parts of the curriculum | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 33 | |

| Knowledge of cognitive, emotional and motivational factors governing the learning of students and obstacles to learning | 6 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 30 | |

| Ability and willingness to differentiate teaching according to the needs of the student and the group | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Knowledge of general pedagogical principles and theories related to teaching and learning | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 31 | |

| Ability to plan and develop a local curriculum on the basis of the national curriculum | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 23 | |

| Organizational and classroom management skills (e.g. organizing class activities) | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 25 | |

| Digital skills, ICT skills [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 56.5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Social and emotional competence | Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 100 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 60 |

| Interactional competence (e.g. active listening, asking, guiding interaction situations and conversation, genuine presence and encounter, encouragement of discussion) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 56 | |

| Emotional competence (e.g. identification and regulation of the teacher’s own feelings, putting oneself in the position of another person, i.e. empathy) | 6 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Communication skills (e.g. readiness for spoken and written communication, informing, preparing instructions, readiness to communicate sensitively) | 6 | 87.0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 47 | |

| Ability to take into account diversity and to act in a multicultural classroom and school community | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Cooperation competence (e.g. ability to work towards a common goal, co-operation with homes, colleagues, other school staff, other stakeholders) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 28 | |

| Leadership, taking and bearing responsibility in the school community and in teaching situations [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 52.2 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 23 | |

| Networking competence (e.g. ability to create networks, participation in a professional community, shared expertise) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 21 | |

| International competence (e.g. language skills, ability to create international networks) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 13.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 19 | |

| Content knowledge | Content knowledge of health education (e.g. content, concepts, current issues and phenomena to be taught) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education (expansion and deepening of the content from one school level to the next), core content, the connections between the content and the comprehensive phenomena arising from the content | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 52 | |

| Ability to identify the diverse nature of knowledge related to the subject (e.g. multidisciplinarity, how knowledge is produced, who produces knowledge, changes in knowledge) | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 27 | |

| Ethical competence | Ability to commit to the ethical responsibility of the teacher’s work (e.g. truthfulness, justice, freedom and responsibility, dignity, reliability) | 7 | 100 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 76 |

| Ability to guide students towards ethical thinking (e.g. building safe learning situations that include ethical reflection and argumentation) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 44 | |

| Ability to identify one’s own values, principles, attitudes and views, plus their significance for personal pedagogical and content choices | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to analyse and solve ethical problems arising in the work of a health education teacher | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Ability to assess and justify the work of a health education teacher from an ethical point of view | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 26 | |

| Competence in school health promotion | Awareness of the role, importance and activities of the teacher as a health promoter for students (e.g. the ability to address the student’s concerns and to guide them, if necessary, to the right kind of help, promoting mental health in the classroom) | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 36 |

| Ability to plan, implement and evaluate initiatives/projects/programmes promoting community well-being and the health of the whole school, and to support the collective ability of staff to promote health [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 18 | |

| Ability to understand the overall health promotion of the school community (e.g. goals, participants, areas of responsibility, subjects, policies) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 30.4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Administrative and financial competence (can plan and implement health-promoting activities from the perspectives of administration and finance) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 21 | |

| Contextual competence | Ability to understand the socio-cultural and social context of the health education subject (e.g. norms and values, political, cultural, historical and economic factors, taking into account local context factors such as school, residential area, families) | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 26 |

| Ability to study widely the starting points and objectives of the subject in relation to current and future challenges (e.g. the nature and ethos of the subject, planetary well-being, peace education, globalization, human rights, inequality, over-consumption, eco-health education, democracy education) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 26 | |

| Knowledge of disciplines related to the health education subject, socially significant organizations and influence channels [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 21.7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 30 | |

| Continuous professional development competence | Ability to reflect, i.e. critical examination of one’s own thinking, competence, teaching and action (e.g. values, attitudes, emotions, motives, awareness of one’s own perception of learning, humanity and knowledge), plus readiness to change one’s own actions following reflection | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills (e.g. collecting and utilizing feedback, innovativeness, learning skills, enthusiasm and motivation for development, self-directiveness) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 51 | |

| Ability to search for, structure and evaluate information | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills (e.g. applying, analysing, evaluating, reasoning, justifying, and creating new knowledge), plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 30 | |

| Ability to examine the competence of the health education teacher in a broad and comprehensive manner (touching on the integrity of competencies, connections, and their impact on one another) [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 69.6 | 4.5 | 7 | 2.5 | 28 | |

| Evidence-based approach (use of effective practices and methods) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 25 | |

| Research competence (management and application of the principles of scientific research in studying one´s own work) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 23 | |

| Professional well-being competence | Ability to maintain and promote one’s well-being at work (e.g. skills in recovery, stress management, limiting work, planning and managing time use) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 41 |

| Resilience (e.g. flexibility, tolerance of incompleteness and uncertainty, readiness for change, readiness to recover from unexpected and difficult situations) | 7 | 87 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 38 |

| Core competence domain . | Competencies . | Median . | Proportion % ≥ 6 . | Q1 . | Q3 . | IQR . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence | Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively (planning-implementation-assessment and impact of choices made at these stages on each other) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 48 |

| Ability to design logically-progressing educational modules and individual lessons according to the curriculum (health literacy, objectives, content), taking into account students and groups | 7 | 95.7 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 63 | |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 7 | 95.7 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 58 | |

| Group management skills | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Skill to give feedback to the student | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Assessment competence (e.g. skills to design and implement criteria-based and ethically sustainable diagnostic, formative and summative evaluation, targeting of evaluation) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Situation-specific competence in lessons (e.g. observation, interpretation, decision-making in learning, flexibility, ability to change activities in a teaching situation if appropriate) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 43 | |

| Ability to take into account the specific characteristics of the subject in learning situations (e.g. the personal nature of the contents, cultural ties, sensitivity) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Teaching skills, encompassing the ability to use various learning environments (including authentic and digital environments), working methods, and learning materials; also the ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters as required | 7 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills (e.g. versatile information-processing) | 7 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 37 | |

| Knowledge of students and groups (e.g. health behaviour, growth and development, youth cultures, background/growth environment, prior knowledge of the subject to be taught, concerns), plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 7 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 36 | |

| Knowledge of the general and subject-specific parts of the curriculum | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 33 | |

| Knowledge of cognitive, emotional and motivational factors governing the learning of students and obstacles to learning | 6 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 30 | |

| Ability and willingness to differentiate teaching according to the needs of the student and the group | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Knowledge of general pedagogical principles and theories related to teaching and learning | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 31 | |

| Ability to plan and develop a local curriculum on the basis of the national curriculum | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 23 | |

| Organizational and classroom management skills (e.g. organizing class activities) | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 25 | |

| Digital skills, ICT skills [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 56.5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Social and emotional competence | Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 100 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 60 |

| Interactional competence (e.g. active listening, asking, guiding interaction situations and conversation, genuine presence and encounter, encouragement of discussion) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 56 | |

| Emotional competence (e.g. identification and regulation of the teacher’s own feelings, putting oneself in the position of another person, i.e. empathy) | 6 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Communication skills (e.g. readiness for spoken and written communication, informing, preparing instructions, readiness to communicate sensitively) | 6 | 87.0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 47 | |

| Ability to take into account diversity and to act in a multicultural classroom and school community | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Cooperation competence (e.g. ability to work towards a common goal, co-operation with homes, colleagues, other school staff, other stakeholders) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 28 | |

| Leadership, taking and bearing responsibility in the school community and in teaching situations [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 52.2 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 23 | |

| Networking competence (e.g. ability to create networks, participation in a professional community, shared expertise) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 21 | |

| International competence (e.g. language skills, ability to create international networks) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 13.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 19 | |

| Content knowledge | Content knowledge of health education (e.g. content, concepts, current issues and phenomena to be taught) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education (expansion and deepening of the content from one school level to the next), core content, the connections between the content and the comprehensive phenomena arising from the content | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 52 | |

| Ability to identify the diverse nature of knowledge related to the subject (e.g. multidisciplinarity, how knowledge is produced, who produces knowledge, changes in knowledge) | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 27 | |

| Ethical competence | Ability to commit to the ethical responsibility of the teacher’s work (e.g. truthfulness, justice, freedom and responsibility, dignity, reliability) | 7 | 100 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 76 |

| Ability to guide students towards ethical thinking (e.g. building safe learning situations that include ethical reflection and argumentation) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 44 | |

| Ability to identify one’s own values, principles, attitudes and views, plus their significance for personal pedagogical and content choices | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to analyse and solve ethical problems arising in the work of a health education teacher | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Ability to assess and justify the work of a health education teacher from an ethical point of view | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 26 | |

| Competence in school health promotion | Awareness of the role, importance and activities of the teacher as a health promoter for students (e.g. the ability to address the student’s concerns and to guide them, if necessary, to the right kind of help, promoting mental health in the classroom) | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 36 |

| Ability to plan, implement and evaluate initiatives/projects/programmes promoting community well-being and the health of the whole school, and to support the collective ability of staff to promote health [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 18 | |

| Ability to understand the overall health promotion of the school community (e.g. goals, participants, areas of responsibility, subjects, policies) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 30.4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Administrative and financial competence (can plan and implement health-promoting activities from the perspectives of administration and finance) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 21 | |

| Contextual competence | Ability to understand the socio-cultural and social context of the health education subject (e.g. norms and values, political, cultural, historical and economic factors, taking into account local context factors such as school, residential area, families) | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 26 |

| Ability to study widely the starting points and objectives of the subject in relation to current and future challenges (e.g. the nature and ethos of the subject, planetary well-being, peace education, globalization, human rights, inequality, over-consumption, eco-health education, democracy education) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 26 | |

| Knowledge of disciplines related to the health education subject, socially significant organizations and influence channels [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 21.7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 30 | |

| Continuous professional development competence | Ability to reflect, i.e. critical examination of one’s own thinking, competence, teaching and action (e.g. values, attitudes, emotions, motives, awareness of one’s own perception of learning, humanity and knowledge), plus readiness to change one’s own actions following reflection | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills (e.g. collecting and utilizing feedback, innovativeness, learning skills, enthusiasm and motivation for development, self-directiveness) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 51 | |

| Ability to search for, structure and evaluate information | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills (e.g. applying, analysing, evaluating, reasoning, justifying, and creating new knowledge), plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 30 | |

| Ability to examine the competence of the health education teacher in a broad and comprehensive manner (touching on the integrity of competencies, connections, and their impact on one another) [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 69.6 | 4.5 | 7 | 2.5 | 28 | |

| Evidence-based approach (use of effective practices and methods) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 25 | |

| Research competence (management and application of the principles of scientific research in studying one´s own work) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 23 | |

| Professional well-being competence | Ability to maintain and promote one’s well-being at work (e.g. skills in recovery, stress management, limiting work, planning and managing time use) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 41 |

| Resilience (e.g. flexibility, tolerance of incompleteness and uncertainty, readiness for change, readiness to recover from unexpected and difficult situations) | 7 | 87 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 38 |

Core competence domains and a list of competencies based on content analysis from the first Delphi round, arranged within the domains according to the consensus criteria used in the second Delphi round (median, IQR with first and third quartiles, pairwise agreement and proportion with value 6 on a Likert scale 1–7)

| Core competence domain . | Competencies . | Median . | Proportion % ≥ 6 . | Q1 . | Q3 . | IQR . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence | Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively (planning-implementation-assessment and impact of choices made at these stages on each other) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 48 |

| Ability to design logically-progressing educational modules and individual lessons according to the curriculum (health literacy, objectives, content), taking into account students and groups | 7 | 95.7 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 63 | |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 7 | 95.7 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 58 | |

| Group management skills | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Skill to give feedback to the student | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Assessment competence (e.g. skills to design and implement criteria-based and ethically sustainable diagnostic, formative and summative evaluation, targeting of evaluation) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Situation-specific competence in lessons (e.g. observation, interpretation, decision-making in learning, flexibility, ability to change activities in a teaching situation if appropriate) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 43 | |

| Ability to take into account the specific characteristics of the subject in learning situations (e.g. the personal nature of the contents, cultural ties, sensitivity) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Teaching skills, encompassing the ability to use various learning environments (including authentic and digital environments), working methods, and learning materials; also the ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters as required | 7 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills (e.g. versatile information-processing) | 7 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 37 | |

| Knowledge of students and groups (e.g. health behaviour, growth and development, youth cultures, background/growth environment, prior knowledge of the subject to be taught, concerns), plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 7 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 36 | |

| Knowledge of the general and subject-specific parts of the curriculum | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 33 | |

| Knowledge of cognitive, emotional and motivational factors governing the learning of students and obstacles to learning | 6 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 30 | |

| Ability and willingness to differentiate teaching according to the needs of the student and the group | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Knowledge of general pedagogical principles and theories related to teaching and learning | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 31 | |

| Ability to plan and develop a local curriculum on the basis of the national curriculum | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 23 | |

| Organizational and classroom management skills (e.g. organizing class activities) | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 25 | |

| Digital skills, ICT skills [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 56.5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Social and emotional competence | Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 100 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 60 |

| Interactional competence (e.g. active listening, asking, guiding interaction situations and conversation, genuine presence and encounter, encouragement of discussion) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 56 | |

| Emotional competence (e.g. identification and regulation of the teacher’s own feelings, putting oneself in the position of another person, i.e. empathy) | 6 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Communication skills (e.g. readiness for spoken and written communication, informing, preparing instructions, readiness to communicate sensitively) | 6 | 87.0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 47 | |

| Ability to take into account diversity and to act in a multicultural classroom and school community | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Cooperation competence (e.g. ability to work towards a common goal, co-operation with homes, colleagues, other school staff, other stakeholders) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 28 | |

| Leadership, taking and bearing responsibility in the school community and in teaching situations [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 52.2 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 23 | |

| Networking competence (e.g. ability to create networks, participation in a professional community, shared expertise) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 21 | |

| International competence (e.g. language skills, ability to create international networks) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 13.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 19 | |

| Content knowledge | Content knowledge of health education (e.g. content, concepts, current issues and phenomena to be taught) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education (expansion and deepening of the content from one school level to the next), core content, the connections between the content and the comprehensive phenomena arising from the content | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 52 | |

| Ability to identify the diverse nature of knowledge related to the subject (e.g. multidisciplinarity, how knowledge is produced, who produces knowledge, changes in knowledge) | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 27 | |

| Ethical competence | Ability to commit to the ethical responsibility of the teacher’s work (e.g. truthfulness, justice, freedom and responsibility, dignity, reliability) | 7 | 100 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 76 |

| Ability to guide students towards ethical thinking (e.g. building safe learning situations that include ethical reflection and argumentation) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 44 | |

| Ability to identify one’s own values, principles, attitudes and views, plus their significance for personal pedagogical and content choices | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to analyse and solve ethical problems arising in the work of a health education teacher | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Ability to assess and justify the work of a health education teacher from an ethical point of view | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 26 | |

| Competence in school health promotion | Awareness of the role, importance and activities of the teacher as a health promoter for students (e.g. the ability to address the student’s concerns and to guide them, if necessary, to the right kind of help, promoting mental health in the classroom) | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 36 |

| Ability to plan, implement and evaluate initiatives/projects/programmes promoting community well-being and the health of the whole school, and to support the collective ability of staff to promote health [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 18 | |

| Ability to understand the overall health promotion of the school community (e.g. goals, participants, areas of responsibility, subjects, policies) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 30.4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Administrative and financial competence (can plan and implement health-promoting activities from the perspectives of administration and finance) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 21 | |

| Contextual competence | Ability to understand the socio-cultural and social context of the health education subject (e.g. norms and values, political, cultural, historical and economic factors, taking into account local context factors such as school, residential area, families) | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 26 |

| Ability to study widely the starting points and objectives of the subject in relation to current and future challenges (e.g. the nature and ethos of the subject, planetary well-being, peace education, globalization, human rights, inequality, over-consumption, eco-health education, democracy education) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 26 | |

| Knowledge of disciplines related to the health education subject, socially significant organizations and influence channels [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 21.7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 30 | |

| Continuous professional development competence | Ability to reflect, i.e. critical examination of one’s own thinking, competence, teaching and action (e.g. values, attitudes, emotions, motives, awareness of one’s own perception of learning, humanity and knowledge), plus readiness to change one’s own actions following reflection | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills (e.g. collecting and utilizing feedback, innovativeness, learning skills, enthusiasm and motivation for development, self-directiveness) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 51 | |

| Ability to search for, structure and evaluate information | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills (e.g. applying, analysing, evaluating, reasoning, justifying, and creating new knowledge), plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 30 | |

| Ability to examine the competence of the health education teacher in a broad and comprehensive manner (touching on the integrity of competencies, connections, and their impact on one another) [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 69.6 | 4.5 | 7 | 2.5 | 28 | |

| Evidence-based approach (use of effective practices and methods) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 25 | |

| Research competence (management and application of the principles of scientific research in studying one´s own work) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 23 | |

| Professional well-being competence | Ability to maintain and promote one’s well-being at work (e.g. skills in recovery, stress management, limiting work, planning and managing time use) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 41 |

| Resilience (e.g. flexibility, tolerance of incompleteness and uncertainty, readiness for change, readiness to recover from unexpected and difficult situations) | 7 | 87 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 38 |

| Core competence domain . | Competencies . | Median . | Proportion % ≥ 6 . | Q1 . | Q3 . | IQR . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence | Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively (planning-implementation-assessment and impact of choices made at these stages on each other) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 48 |

| Ability to design logically-progressing educational modules and individual lessons according to the curriculum (health literacy, objectives, content), taking into account students and groups | 7 | 95.7 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 63 | |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 7 | 95.7 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 58 | |

| Group management skills | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Skill to give feedback to the student | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Assessment competence (e.g. skills to design and implement criteria-based and ethically sustainable diagnostic, formative and summative evaluation, targeting of evaluation) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 45 | |

| Situation-specific competence in lessons (e.g. observation, interpretation, decision-making in learning, flexibility, ability to change activities in a teaching situation if appropriate) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 43 | |

| Ability to take into account the specific characteristics of the subject in learning situations (e.g. the personal nature of the contents, cultural ties, sensitivity) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Teaching skills, encompassing the ability to use various learning environments (including authentic and digital environments), working methods, and learning materials; also the ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters as required | 7 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills (e.g. versatile information-processing) | 7 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 37 | |

| Knowledge of students and groups (e.g. health behaviour, growth and development, youth cultures, background/growth environment, prior knowledge of the subject to be taught, concerns), plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 7 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 36 | |

| Knowledge of the general and subject-specific parts of the curriculum | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 33 | |

| Knowledge of cognitive, emotional and motivational factors governing the learning of students and obstacles to learning | 6 | 78.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 30 | |

| Ability and willingness to differentiate teaching according to the needs of the student and the group | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Knowledge of general pedagogical principles and theories related to teaching and learning | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 29 | |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 31 | |

| Ability to plan and develop a local curriculum on the basis of the national curriculum | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 23 | |

| Organizational and classroom management skills (e.g. organizing class activities) | 6 | 60.9 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 25 | |

| Digital skills, ICT skills [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 56.5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Social and emotional competence | Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 100 | 6.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 60 |

| Interactional competence (e.g. active listening, asking, guiding interaction situations and conversation, genuine presence and encounter, encouragement of discussion) | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 56 | |

| Emotional competence (e.g. identification and regulation of the teacher’s own feelings, putting oneself in the position of another person, i.e. empathy) | 6 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Communication skills (e.g. readiness for spoken and written communication, informing, preparing instructions, readiness to communicate sensitively) | 6 | 87.0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 47 | |

| Ability to take into account diversity and to act in a multicultural classroom and school community | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Cooperation competence (e.g. ability to work towards a common goal, co-operation with homes, colleagues, other school staff, other stakeholders) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 28 | |

| Leadership, taking and bearing responsibility in the school community and in teaching situations [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 52.2 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 23 | |

| Networking competence (e.g. ability to create networks, participation in a professional community, shared expertise) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 21 | |

| International competence (e.g. language skills, ability to create international networks) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 13.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 19 | |

| Content knowledge | Content knowledge of health education (e.g. content, concepts, current issues and phenomena to be taught) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education (expansion and deepening of the content from one school level to the next), core content, the connections between the content and the comprehensive phenomena arising from the content | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 52 | |

| Ability to identify the diverse nature of knowledge related to the subject (e.g. multidisciplinarity, how knowledge is produced, who produces knowledge, changes in knowledge) | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 27 | |

| Ethical competence | Ability to commit to the ethical responsibility of the teacher’s work (e.g. truthfulness, justice, freedom and responsibility, dignity, reliability) | 7 | 100 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 76 |

| Ability to guide students towards ethical thinking (e.g. building safe learning situations that include ethical reflection and argumentation) | 7 | 95.7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 44 | |

| Ability to identify one’s own values, principles, attitudes and views, plus their significance for personal pedagogical and content choices | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 42 | |

| Ability to analyse and solve ethical problems arising in the work of a health education teacher | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 40 | |

| Ability to assess and justify the work of a health education teacher from an ethical point of view | 6 | 69.6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 26 | |

| Competence in school health promotion | Awareness of the role, importance and activities of the teacher as a health promoter for students (e.g. the ability to address the student’s concerns and to guide them, if necessary, to the right kind of help, promoting mental health in the classroom) | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 36 |

| Ability to plan, implement and evaluate initiatives/projects/programmes promoting community well-being and the health of the whole school, and to support the collective ability of staff to promote health [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 18 | |

| Ability to understand the overall health promotion of the school community (e.g. goals, participants, areas of responsibility, subjects, policies) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 30.4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 34 | |

| Administrative and financial competence (can plan and implement health-promoting activities from the perspectives of administration and finance) [Removed Round 3] | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 21 | |

| Contextual competence | Ability to understand the socio-cultural and social context of the health education subject (e.g. norms and values, political, cultural, historical and economic factors, taking into account local context factors such as school, residential area, families) | 6 | 65.2 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 26 |

| Ability to study widely the starting points and objectives of the subject in relation to current and future challenges (e.g. the nature and ethos of the subject, planetary well-being, peace education, globalization, human rights, inequality, over-consumption, eco-health education, democracy education) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 26 | |

| Knowledge of disciplines related to the health education subject, socially significant organizations and influence channels [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 21.7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 30 | |

| Continuous professional development competence | Ability to reflect, i.e. critical examination of one’s own thinking, competence, teaching and action (e.g. values, attitudes, emotions, motives, awareness of one’s own perception of learning, humanity and knowledge), plus readiness to change one’s own actions following reflection | 7 | 100 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills (e.g. collecting and utilizing feedback, innovativeness, learning skills, enthusiasm and motivation for development, self-directiveness) | 7 | 87.0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 51 | |

| Ability to search for, structure and evaluate information | 6 | 82.6 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 35 | |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills (e.g. applying, analysing, evaluating, reasoning, justifying, and creating new knowledge), plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 6 | 73.9 | 5.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 30 | |

| Ability to examine the competence of the health education teacher in a broad and comprehensive manner (touching on the integrity of competencies, connections, and their impact on one another) [Removed Round 3] | 6 | 69.6 | 4.5 | 7 | 2.5 | 28 | |

| Evidence-based approach (use of effective practices and methods) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 47.8 | 5 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 25 | |

| Research competence (management and application of the principles of scientific research in studying one´s own work) [Removed Round 3] | 5 | 39.1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 23 | |

| Professional well-being competence | Ability to maintain and promote one’s well-being at work (e.g. skills in recovery, stress management, limiting work, planning and managing time use) | 7 | 91.3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 41 |

| Resilience (e.g. flexibility, tolerance of incompleteness and uncertainty, readiness for change, readiness to recover from unexpected and difficult situations) | 7 | 87 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 38 |

The domain Competence in school health promotion (n = 4) refers to the ability to understand school health promotion as a whole, plus the ability to plan, implement and evaluate school-wide health promotion projects or programmes. Contextual competence (n = 3) contains an understanding of the socio-cultural context in which teaching occurs. The Continuous professional development competence (n = 7) refers to the ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional expertise, and to incorporate new understandings within practice. The last domain, the Professional well-being competence (n = 2), includes the ability to maintain and promote one’s own well-being at work, and also teachers’ resilience as a dynamic interplay between protective and stress factors.

In the second Delphi round, 40 of the 52 original competencies were selected as the most important for HE teachers’ work based on four criteria mentioned above and their pre-defined cut-off values, thus establishing the consensus among the expert panellists (Table 2). Most of the competencies (n = 43) had a median value of 7 or 6, and the median for the remaining nine competencies was 5 or 4. The level of agreement between the experts was comparatively high for all the competencies, being highest for the most important items and slightly lower for items with a median of 6. The agreement was lowest among competencies with a median of 5 or 4, but still relatively strong.

All the competencies that fell under the domains of Ethical competence (n = 5), Content knowledge (n = 3) or Professional well-being competence (n = 2) were selected for the third Delphi round. In the largest competence domain, Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence (n = 19), only one competence was excluded. Three competencies were removed from each of the domains of Social and emotional competence (n = 9), Competence in school health promotion (n = 4) and Continuous professional development competence (n = 7). Two competencies were omitted from the Contextual competence (n = 3) domain.

Third round

With 24 expert panellists in the final Delphi round, the theoretical maximum for the inverse sum score was 360 if all experts had chosen the same competence as the most important. The five most important competencies were content knowledge (score 211), teaching skills (score 204), interactional competence (score 187), the ability to reflect (score 155) and the ability to design logically progressing educational modules in line with the curriculum (score 149) (Table 3). At least three-quarters of the experts ranked these competencies in the top 15 most important. The sum score of the remaining 10 competencies varied between 87 and 129. Moreover, 46%–71% of the experts ranked these competencies in the top 15, with reasonably good pairwise agreement (26%–34%). Overall, the agreement between experts in the third round could be regarded as fair according to Kendall’s W (0.22; Χ²(39) = 205.86; p < 0.001).

| Competencies . | Rank . | Sum . | Percentage in top 15 . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content knowledge of health education | 1 | 211 | 75.0 | 35 |

| Teaching skills, ability to use various learning environments, working methods and learning materials, ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters | 2 | 204 | 75.0 | 31 |

| Interactional competence | 3 | 187 | 75.0 | 28 |

| Ability to reflect | 4 | 155 | 83.3 | 23 |

| Ability to design logically progressing educational modules and individual lessons | 5 | 149 | 75.0 | 24 |

| Assessment competence | 6 | 129 | 70.8 | 32 |

| Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 120 | 54.2 | 30 |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 8 | 117 | 58.3 | 26 |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills | 9 | 107 | 45.8 | 37 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills | 10 | 99 | 58.3 | 29 |

| Knowledge of students and groups, plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 11 | 93 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 12 | 91 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively | 13 | 89 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education | 14 | 88 | 54.2 | 29 |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills, plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 15 | 87 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Competencies . | Rank . | Sum . | Percentage in top 15 . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content knowledge of health education | 1 | 211 | 75.0 | 35 |

| Teaching skills, ability to use various learning environments, working methods and learning materials, ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters | 2 | 204 | 75.0 | 31 |

| Interactional competence | 3 | 187 | 75.0 | 28 |

| Ability to reflect | 4 | 155 | 83.3 | 23 |

| Ability to design logically progressing educational modules and individual lessons | 5 | 149 | 75.0 | 24 |

| Assessment competence | 6 | 129 | 70.8 | 32 |

| Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 120 | 54.2 | 30 |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 8 | 117 | 58.3 | 26 |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills | 9 | 107 | 45.8 | 37 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills | 10 | 99 | 58.3 | 29 |

| Knowledge of students and groups, plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 11 | 93 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 12 | 91 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively | 13 | 89 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education | 14 | 88 | 54.2 | 29 |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills, plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 15 | 87 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Competencies . | Rank . | Sum . | Percentage in top 15 . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content knowledge of health education | 1 | 211 | 75.0 | 35 |

| Teaching skills, ability to use various learning environments, working methods and learning materials, ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters | 2 | 204 | 75.0 | 31 |

| Interactional competence | 3 | 187 | 75.0 | 28 |

| Ability to reflect | 4 | 155 | 83.3 | 23 |

| Ability to design logically progressing educational modules and individual lessons | 5 | 149 | 75.0 | 24 |

| Assessment competence | 6 | 129 | 70.8 | 32 |

| Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 120 | 54.2 | 30 |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 8 | 117 | 58.3 | 26 |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills | 9 | 107 | 45.8 | 37 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills | 10 | 99 | 58.3 | 29 |

| Knowledge of students and groups, plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 11 | 93 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 12 | 91 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively | 13 | 89 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education | 14 | 88 | 54.2 | 29 |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills, plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 15 | 87 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Competencies . | Rank . | Sum . | Percentage in top 15 . | Pairwise agreement . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content knowledge of health education | 1 | 211 | 75.0 | 35 |

| Teaching skills, ability to use various learning environments, working methods and learning materials, ability to promote the active participation of the learner and to demonstrate matters | 2 | 204 | 75.0 | 31 |

| Interactional competence | 3 | 187 | 75.0 | 28 |

| Ability to reflect | 4 | 155 | 83.3 | 23 |

| Ability to design logically progressing educational modules and individual lessons | 5 | 149 | 75.0 | 24 |

| Assessment competence | 6 | 129 | 70.8 | 32 |

| Ability to create a safe learning environment | 7 | 120 | 54.2 | 30 |

| Ability to plan motivating and meaningful learning situations and to support learners’ self-efficacy | 8 | 117 | 58.3 | 26 |

| Ability to develop students’ thinking skills | 9 | 107 | 45.8 | 37 |

| Ability and willingness to maintain and develop one’s own professional skills | 10 | 99 | 58.3 | 29 |

| Knowledge of students and groups, plus the ability to strengthen student and group knowledge | 11 | 93 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to guide students in study skills, and to support them in setting goals and evaluating their achievement | 12 | 91 | 50.0 | 31 |

| Ability to look at the teaching-learning process of health education comprehensively | 13 | 89 | 45.8 | 34 |

| Ability to understand the knowledge structure of the learning content of health education | 14 | 88 | 54.2 | 29 |

| Critical thinking and problem-solving skills, plus awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes (metacognition) | 15 | 87 | 45.8 | 34 |

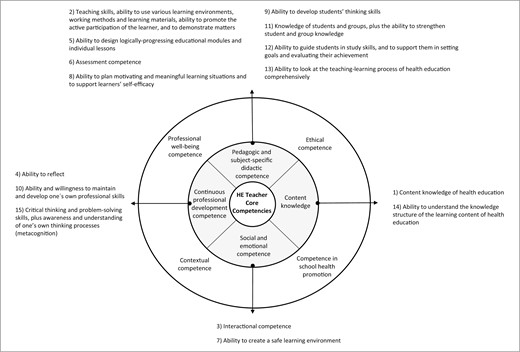

The distribution of the 15 most important competencies in terms of the core competence domains is shown in Figure 1. Most of the important competencies (n = 8) belonged to the domain of Pedagogic and subject-specific didactic competence. Other competence domains that received mentions were Continuous professional development competence (n = 3), Social and emotional competence (n = 2) and Content knowledge (n = 2). The competencies included in the other four domains did not make the list of the 15 most important competencies.

Health education teacher core competence domains and the related 15 most important competencies, numbered according to rank. Fundamental competencies are presented in gray, and supportive competencies are in the outer circle.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to identify and describe the competencies that are essential for a HE teacher’s work. In the first round, 52 competencies were identified from the experts’ expressions (n = 343), and these were categorized into eight domains. In the second round, the expert panellists evaluated the importance of each competence and 40 most important were identified based on pre-defined cut-off values. In the third round, the experts ranked the 15 most important competencies from this set, and these competencies were divided into four fundamental domains.

Fundamental HE teacher competence domains