-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kevin Huang, Emma M Beckman, Norman Ng, Genevieve A Dingle, Rong Han, Kari James, Elisabeth Winkler, Michalis Stylianou, Sjaan R Gomersall, Effectiveness of physical activity interventions on undergraduate students’ mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis, Health Promotion International, Volume 39, Issue 3, June 2024, daae054, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daae054

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the effectiveness of physical activity interventions on undergraduate students’ mental health. Seven databases were searched and a total of 59 studies were included. Studies with a comparable control group were meta-analysed, and remaining studies were narratively synthesized. The included studies scored very low GRADE and had a high risk of bias. Meta-analyses indicated physical activity interventions are effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety (n = 20, standardized mean difference (SMD) = −0.88, 95% CI [−1.23, −0.52]), depression (n = 14, SMD = −0.73, 95% CI [−1.00, −0.47]) and stress (n = 10, SMD = −0.61, 95% CI [−0.94, −0.28]); however, there was considerable heterogeneity (anxiety, I2 = 90.29%; depression I2 = 49.66%; stress I2 = 86.97%). The narrative synthesis had mixed findings. Only five studies reported being informed by a behavioural change theory and only 30 reported intervention fidelity. Our review provides evidence supporting the potential of physical activity interventions in enhancing the mental health of undergraduate students. More robust intervention design and implementation are required to better understand the effectiveness of PA interventions on mental health outcomes.

Physical activity is a known health behaviour that protects undergraduate students’ mental health, but the exact effects were unknown.

Meta-analyses identified that physical activity had positive effects on stress, anxiety and depression. Narrative synthesis found mixed results.

The syntheses found high levels of variability, such as the type of physical activity and duration of intervention.

The studies were of low quality and certainty of evidence as marked by an under-reporting of intervention fidelity and potential under-utilization of behaviour change theories.

Physical activity could be a mental health promotion strategy, but future interventions need to be better reported and grounded in theory.

BACKGROUND

Undergraduate students starting university face numerous challenges. For many students, this significant life transition includes moving to a new city or state and away from sources of support typically found in friends and family (Meehan and Howells, 2019). While newfound independence and autonomy are welcomed by some, the lack of emotional support (Bitsika et al., 2010), academic workload (Fernández et al., 2017) and the self-directed learning style adopted in many universities (Bayram and Bilgel, 2008) can result in significant challenges for students’ mental health and wellbeing. Undergraduate university students, typically in the 18–25 age range, face the highest risk of experiencing the first onset of mental health issues (Solmi et al., 2022), such as poor wellbeing and symptoms of psychological distress, including anxiety and depression. Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of undergraduate students are diagnosed with some form of mental health illness relative to individuals of other ages (Solmi et al., 2022) and this population also tends to report higher levels of psychological distress when compared with non-students in three national surveys (Cvetkovski et al., 2012).

Globally, there has been an increase in the proportion of undergraduate students experiencing poor mental health (Lipson et al., 2022). For instance, a longitudinal study conducted between 2013 and 2021 across the United States showed a 50% increase in mental health diagnoses and a two-fold increase in displaying poor mental health symptoms in university students (Lipson et al., 2022). Mental health services have not been able to meet the increased demand, resulting in long wait times and inadequate access to psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals (Broglia et al., 2018; Dingle et al., 2021; Punton et al., 2022). Given the escalating need and significant barriers to accessing care, there is a key imperative to examine prevention strategies for mental health in undergraduate students.

Participation in physical activity (PA; WHO, 2023) is one strategy that has been shown to improve physical health (Benaich et al., 2021) and prevent poor mental health (Román-Mata et al., 2020). Participating in a minimum of 150 min per week of moderate to vigorous intensity PA is protective against symptoms of depression (Peluso and Guerra de Andrade, 2005) and is associated with lower anxiety and stress, and a higher quality of life (Herbert et al., 2020). PA affects mental health in both direct ways (e.g. increasing endorphin release, which improves mood; Mikkelsen et al., 2017) and indirect ways, such as via improving the quality of sleep, which can lead to better mental health (Babaeer et al., 2020). Conversely, insufficient PA is associated with poorer mental health, increased self-harm and more suicide attempts in university students (Grasdalsmoen et al., 2020). Despite the health benefits of PA, however, undergraduate students remain insufficiently active (Mahony et al., 2019). For example, an Australian study found 30% fewer undergraduate students reported sufficient PA levels in 2020 compared to 2018 (Gallo et al., 2020). Another study conducted in 2022, which had a sample of more than 15 000 South East Asian undergraduate students, reported that 39.7% of their participants were physically inactive (Rahman et al., 2022).

While available evidence supports that PA can enhance mental health outcomes in undergraduate students (e.g. Mailey et al., 2010; Melnyk et al., 2014; Herbert et al., 2020), individual studies report mixed findings. For example, in a study with German students, a 6-week aerobic exercise intervention was found to reduce symptoms of depression and stress over time relative to a waitlist control condition, although the effect on anxiety was not significant (Herbert et al., 2020). However, in a study using a 2-month internet-delivered PA intervention for undergraduate students, Mailey et al. (2010) found that those in the intervention group reported a significant decrease in anxiety compared to the waitlist control group. Interestingly, Mailey et al. (2010) also found that depression decreased in both groups. One scoping review has attempted to synthesize available evidence in young people aged 12–26 years and concluded that PA interventions seemed to be effective in reducing certain symptoms of poor mental health, particularly with higher intensity PA interventions, but found varying degrees of effectiveness depending on intervention design, intensity and context (Pascoe et al., 2020). This review, however, focused on young adults more broadly and did not exclusively examine university students in their unique context, included a small number of studies and did not include a meta-analysis. Given that most existing studies on PA interventions targeting undergraduate students’ mental health have been synthesized narratively (Lubans et al., 2016; Dogra et al., 2018; Ellard et al., 2023; Donnelly et al., 2024), we have observed that there are currently no systematic reviews on this topic that have synthesized findings quantitatively, for example, using meta-analyses, which can offer additional insights for understanding effectiveness (Melendez-Torres et al., 2017; Mellor, 2021).

Synthesizing the literature that examines the impact of PA on mental health outcomes specifically in university students is warranted given the unique context of affordances and challenges associated with being a university student (Meehan and Howells, 2019). Such an endeavour can provide insights into the effectiveness of PA interventions in enhancing the mental health of this population, as well as into the design and implementation of identified interventions, which is a critical context to consider when examining their effectiveness. Information about whether and how the design of PA interventions has been informed by conceptual or theoretical frameworks that promote behaviour change (Michie et al., 2009) is particularly important as these facilitate the development, assessment and replicability of PA interventions, and provide a deeper understanding of underlying mechanisms that support effectiveness. Therefore, the current study aims to systematically review and meta-analyse available literature to determine the effectiveness of PA interventions on mental health outcomes in undergraduate students.

METHOD

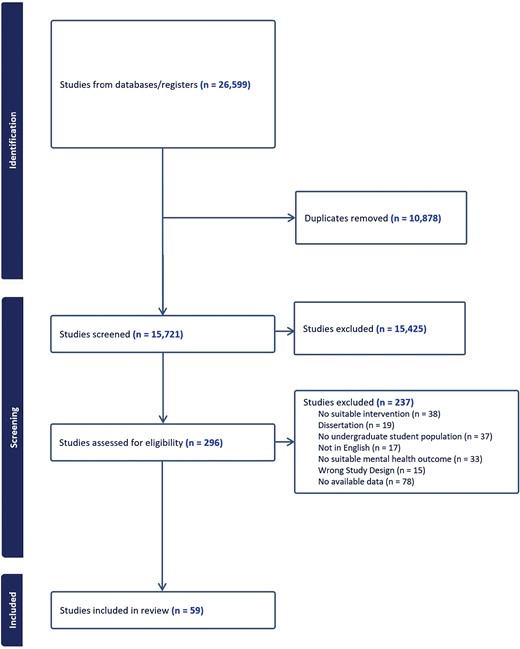

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 8 June 2022 (CRD42022320558) and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

Search strategy and study selection

An initial scoping search was conducted by the first reviewer (K.H.) to test and develop various keywords based on the PICO question. The finalized keywords were then confirmed by four reviewers (K.H., S.G., E.B. and G.D.). Subsequently, a search strategy was developed in PubMed with the assistance of an academic librarian and later adapted to an additional six databases (CINAHL, PsycINFO, Embase, Web of Science, SportsDiscus and Scopus). The search was initially conducted on 24 May 2022 and subsequently updated on 14 August 2023. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used as search terms for mental health outcomes where appropriate, alongside keywords representing various types of PA, and different ways to describe undergraduate university students. Complete search terms for each database are found in Supplementary Appendix A.

The results of the systematic searches were imported into Covidence. Following duplicate removal, title and abstracts and subsequently, full-text articles were independently screened by two reviewers based on predetermined eligibility criteria. Inter-rater discrepancies at both screening stages were resolved via discussion and, where necessary, a third reviewer was brought in to reach a consensus.

Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed studies reporting on original research and published in English were included if the following criteria were met: (i) participants were enrolled in undergraduate university programs; (ii) PA interventions were at least 4 weeks in duration (Lally et al., 2010) and were part of experimental randomized controlled trials (RCTs), longitudinal, cohort, pre-post and single-arm studies; (iii) comparators included waitlist controls, no-treatment control, other health behaviour comparison or no control (e.g. single-arm or pre-post studies); (iv) studies reported mental health outcomes including symptoms of psychological distress, such as anxiety and depression, loneliness or social isolation and stress. The exclusion criteria were: (i) undergraduate student samples that were recruited based on convenience, rather than having a rationale for recruiting undergraduate students specifically, and studies that included a mix of undergraduate and postgraduate students in their data; (ii) interventions that targeted multiple health behaviours (e.g. diet and PA, or nutrition and PA) in the same intervention arm; (iii) cross-sectional studies; (iv) studies that exclusively examined Profile of Mood States (Pollock et al., 1979) as they are indicators of transitory states rather than mental health symptoms. Additionally, grey literature, including theses and dissertations, were excluded.

Data extraction

After the screening process, the following data were extracted: study information (authors, year and country of publication, study design), participant information (e.g. sample size), characteristics of the intervention (type of PA intervention, duration and frequency, inclusion of theoretical concepts), fidelity (e.g. attendance), primary and secondary outcomes and measurement time points. Statistical data extracted (when reported) included: pre- and post-mean and standard deviation (SD), group change scores and their SD, p values for between-group effects, within-group effects and group-by-time interaction effects and standardized effect sizes. Data extraction was performed by two reviewers and a third reviewer was involved in resolving discrepancies where necessary.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted by two reviewers independently using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool from the McMaster Evidence Review and Synthesis Team (Thomas et al., 2004; Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012). The EPHPP tool is used to assess the quality of RCTs and cohort (pre-post) experimental trials. Assessments were based on six domains, with each domain requiring a rating of weak, moderate or strong: (i) selection bias; (ii) study design; (iii) confounders; (iv) blinding; (v) data collection method and (vi) attrition. The overall quality of each study was assessed based on the total number of weak ratings given per domain: weak (≥2 weak ratings), moderate (one weak rating) and strong (no weak ratings).

The overall certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Method (GRADE; Guyatt et al., 2011). GRADE was performed for each of the outcomes included in the meta-analysis.

Data synthesis

Data were synthesized in two ways. RCTs and non-RCTs with comparable control groups were synthesized using a meta-analysis. For studies that were not included in the meta-analysis, a narrative synthesis was conducted using Cochrane’s synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) guidelines (Campbell et al., 2020).

Meta-analyses

Meta-analyses were performed using STATA version 18 (StataCorp, 2023). Only the studies that compared a PA intervention with an appropriate control group not receiving the relevant intervention (RCTs and non-RCTs included) were included for determining the impact on continuous measures of mental health outcomes. The meta-analyses used inputs such as SMD and its standard error. Most studies reported cross-sectional means and SDs, but few reported on change or intervention effects with confidence intervals, and many were not obtainable even after attempting to contact corresponding authors. Therefore, for the meta-analysis, t-tests of post-intervention mean, and SD were used to calculate mean differences and their error, divided by the pre-intervention pooled SD to create SMDs that could be compared despite the disparate measures across studies. Studies that had more than one PA intervention group were counted as separate studies, with standard errors corrected for non-independence when they involved a shared control group using the method outlined by Cates (2015). The random DerSimonian-Laird effects model (Dersimonian and Laird, 1986) was used due to expected heterogeneity in the studies, which was reported in as I2 and Cochrane’s Q test. Begg’s test was performed to explore potential small-study effects and publication bias (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994), with trim-and-fill analyses reported wherever there were suggestions of publication bias (Duval and Tweedie, 2000). ‘Leave-one-out’ sensitivity analyses were performed to determine whether any studies had a disproportionately positive effect on the conclusion.

Narrative synthesis

The narrative synthesis included: studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria for the meta-analysis; and studies from the meta-analysis that tested outcomes in addition to anxiety, depression and stress. To facilitate the narrative synthesis, relevant study outcomes (e.g. depression, stress, anxiety) were coded as ‘+’, ‘−’, ‘/’ and ‘*’, where ‘+’ represents a statistically significant effect that favours improvement in the outcome, ‘−’ represents a statistically significant effect that favours a decline in the outcome, ‘/’ represents no statistical effect and ‘*’ represents outcomes that were tested using within groups statistical tests only, or where there was no statistical testing on the outcome (but pre-post descriptive data were reported).

RESULTS

The study selection process is summarized in Figure 1 based on PRISMA guidelines. After title/abstract and full-text screening, 59 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review, 38 of which were RCTs and 21 of which used other study designs. A total of 25 studies, comprising a mix of both RCTs and non-RCTs, were included in meta-analyses for the outcomes of anxiety, depression and stress.

Quality assessment of studies

Based on the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool, the quality of included studies was mostly weak (47 out of 59 studies). A summary of quality assessment results showed that about half of the studies received an overall rating of weak because of selection bias, poor study design (e.g. no control group), lack of controlling for potential confounders and/or blinding (see Supplementary Material B, Figure S3 for quality assessment breakdown). The certainty of evidence (GRADE) was very low for each of the outcomes in the meta-analysis (anxiety, depression and stress) as these studies were assessed as demonstrating a high risk of bias (limitation), heterogeneity, indirectness between included studies and imprecision (see Supplementary Material A, Table S3 for GRADE assessment).

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies and interventions. Aerobic exercise was the most reported PA intervention; 26 out of 59 studies implemented some form of aerobic exercise such as running, dancing or walking. Seventeen studies were mindfulness-based, low-intensity or low-impact exercises like yoga, baduanjin and taichiquan. Eight studies included resistance training such as muscular strengthening exercises, with six studies exposing participants to both aerobic and strength exercises. Two studies conducted pilates interventions, one used walking and another conducted an educational intervention only. The specific modalities for each study can be found in Table 2. Anxiety (N = 28), depression (N = 25) and stress (N = 21) were the most frequently assessed mental health outcomes across all included studies, with other outcomes being assessed in six or fewer studies each, and thus were selected to be meta-analysed. Commonly used measures were the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1968), the Beck’s Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961) and the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983). Eight studies reported change in PA with the intervention, and of these, seven reported positive changes in PA and one reported post-intervention follow-up of PA as a measure of sustained improvement in PA behaviour (McFadden et al., 2017). It is worth noting that four studies were conducted during COVID-19 (BARĞI, 2022; Hamed et al., 2021; Terzioğlu et al., 2022; Tomar et al., 2023) and thus the mental health state of the participants might have been influenced by COVID-19-related factors.

| Characteristic . | Category . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | 2 | 3.39 |

| Canada | 4 | 6.78 | |

| China | 16 | 27.11 | |

| Germany | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Iran | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Japan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Jordan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 3.39 | |

| South Korea | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Spain | 2 | 3.39 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Turkey | 7 | 11.86 | |

| United States | 15 | 25.42 | |

| Study design | Randomized | 35 | 40.68 |

| Non-randomized | 24 | 59.32 | |

| Sample size | ≥100 | 18 | 30.51 |

| <100 | 41 | 69.49 | |

| Gender | Mixed | 46 | 77.97 |

| Males only | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Females only | 12 | 20.34 | |

| Participant background | Existing mental health condition (Anxiety) | 8 | 13.56 |

| Existing mental health condition (Depression) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Enrolled as part of a course | 9 | 15.25 | |

| Referred to from psychology clinic | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Healthy (Physically/Mentally) | 10 | 16.94 | |

| Others (e.g. fatigue, poor sleep quality, stress, experience of negative life event, dance experience) | 6 | 10.17 | |

| Not reported | 22 | 37.29 | |

| Intervention duration | 4–6 weeks | 14 | 23.73 |

| 7–9 weeks | 18 | 30.51 | |

| 10–12 weeks | 17 | 28.81 | |

| >12 weeks | 10 | 16.95 | |

| Intervention frequency | 1–2 times per week | 23 | 38.98 |

| 3–4 times per week | 22 | 37.29 | |

| 5–7 times/week | 8 | 13.56 | |

| Other (gradual increase/self-directed) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Not reported | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Session duration | 0–30 min | 10 | 16.95 |

| 30–60 min | 18 | 30.51 | |

| ≥60 min | 11 | 18.64 | |

| Not reported | 20 | 33.90 | |

| Type of physical activity* | Aerobic exercise (including dancing, walking, cheerleading and structured ball sports) | 41 | 54.66 |

| Strength training | 15 | 20 | |

| Low-intensity/Low-impact exercise (including pilates, Tai Chi Quan, yoga, Ba Duan Jin, Kuok Sun Do) | 19 | 25.33 | |

| Education only | 3 | 4 | |

| Intervention fidelity measures** | Reported | 30 | 50.85 |

| Not reported | 29 | 49.15 | |

| Measurement of physical activity | Reported | 8 | 13.56 |

| Not reported | 51 | 86.44 | |

| Intervention based on theory | Yes (list of theories used) 1. SAAFE principles (Lubans et al., 2017) 2. SMART goal setting Doran, 1981, 3. Nies and Kershaw, (2002) model of PA and health outcomes 4. Motivational interviewing (Noonan & Moyers, 2009) 5. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2002) 6. Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2022) | 5 | 8.47 |

| Not reported | 54 | 91.53 |

| Characteristic . | Category . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | 2 | 3.39 |

| Canada | 4 | 6.78 | |

| China | 16 | 27.11 | |

| Germany | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Iran | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Japan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Jordan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 3.39 | |

| South Korea | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Spain | 2 | 3.39 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Turkey | 7 | 11.86 | |

| United States | 15 | 25.42 | |

| Study design | Randomized | 35 | 40.68 |

| Non-randomized | 24 | 59.32 | |

| Sample size | ≥100 | 18 | 30.51 |

| <100 | 41 | 69.49 | |

| Gender | Mixed | 46 | 77.97 |

| Males only | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Females only | 12 | 20.34 | |

| Participant background | Existing mental health condition (Anxiety) | 8 | 13.56 |

| Existing mental health condition (Depression) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Enrolled as part of a course | 9 | 15.25 | |

| Referred to from psychology clinic | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Healthy (Physically/Mentally) | 10 | 16.94 | |

| Others (e.g. fatigue, poor sleep quality, stress, experience of negative life event, dance experience) | 6 | 10.17 | |

| Not reported | 22 | 37.29 | |

| Intervention duration | 4–6 weeks | 14 | 23.73 |

| 7–9 weeks | 18 | 30.51 | |

| 10–12 weeks | 17 | 28.81 | |

| >12 weeks | 10 | 16.95 | |

| Intervention frequency | 1–2 times per week | 23 | 38.98 |

| 3–4 times per week | 22 | 37.29 | |

| 5–7 times/week | 8 | 13.56 | |

| Other (gradual increase/self-directed) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Not reported | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Session duration | 0–30 min | 10 | 16.95 |

| 30–60 min | 18 | 30.51 | |

| ≥60 min | 11 | 18.64 | |

| Not reported | 20 | 33.90 | |

| Type of physical activity* | Aerobic exercise (including dancing, walking, cheerleading and structured ball sports) | 41 | 54.66 |

| Strength training | 15 | 20 | |

| Low-intensity/Low-impact exercise (including pilates, Tai Chi Quan, yoga, Ba Duan Jin, Kuok Sun Do) | 19 | 25.33 | |

| Education only | 3 | 4 | |

| Intervention fidelity measures** | Reported | 30 | 50.85 |

| Not reported | 29 | 49.15 | |

| Measurement of physical activity | Reported | 8 | 13.56 |

| Not reported | 51 | 86.44 | |

| Intervention based on theory | Yes (list of theories used) 1. SAAFE principles (Lubans et al., 2017) 2. SMART goal setting Doran, 1981, 3. Nies and Kershaw, (2002) model of PA and health outcomes 4. Motivational interviewing (Noonan & Moyers, 2009) 5. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2002) 6. Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2022) | 5 | 8.47 |

| Not reported | 54 | 91.53 |

Note. *Some interventions had more than one type of physical activity. ** Intervention fidelity was assessed according to whether authors reported attendance/adherence to the prescribed physical activity program.

| Characteristic . | Category . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | 2 | 3.39 |

| Canada | 4 | 6.78 | |

| China | 16 | 27.11 | |

| Germany | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Iran | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Japan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Jordan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 3.39 | |

| South Korea | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Spain | 2 | 3.39 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Turkey | 7 | 11.86 | |

| United States | 15 | 25.42 | |

| Study design | Randomized | 35 | 40.68 |

| Non-randomized | 24 | 59.32 | |

| Sample size | ≥100 | 18 | 30.51 |

| <100 | 41 | 69.49 | |

| Gender | Mixed | 46 | 77.97 |

| Males only | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Females only | 12 | 20.34 | |

| Participant background | Existing mental health condition (Anxiety) | 8 | 13.56 |

| Existing mental health condition (Depression) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Enrolled as part of a course | 9 | 15.25 | |

| Referred to from psychology clinic | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Healthy (Physically/Mentally) | 10 | 16.94 | |

| Others (e.g. fatigue, poor sleep quality, stress, experience of negative life event, dance experience) | 6 | 10.17 | |

| Not reported | 22 | 37.29 | |

| Intervention duration | 4–6 weeks | 14 | 23.73 |

| 7–9 weeks | 18 | 30.51 | |

| 10–12 weeks | 17 | 28.81 | |

| >12 weeks | 10 | 16.95 | |

| Intervention frequency | 1–2 times per week | 23 | 38.98 |

| 3–4 times per week | 22 | 37.29 | |

| 5–7 times/week | 8 | 13.56 | |

| Other (gradual increase/self-directed) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Not reported | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Session duration | 0–30 min | 10 | 16.95 |

| 30–60 min | 18 | 30.51 | |

| ≥60 min | 11 | 18.64 | |

| Not reported | 20 | 33.90 | |

| Type of physical activity* | Aerobic exercise (including dancing, walking, cheerleading and structured ball sports) | 41 | 54.66 |

| Strength training | 15 | 20 | |

| Low-intensity/Low-impact exercise (including pilates, Tai Chi Quan, yoga, Ba Duan Jin, Kuok Sun Do) | 19 | 25.33 | |

| Education only | 3 | 4 | |

| Intervention fidelity measures** | Reported | 30 | 50.85 |

| Not reported | 29 | 49.15 | |

| Measurement of physical activity | Reported | 8 | 13.56 |

| Not reported | 51 | 86.44 | |

| Intervention based on theory | Yes (list of theories used) 1. SAAFE principles (Lubans et al., 2017) 2. SMART goal setting Doran, 1981, 3. Nies and Kershaw, (2002) model of PA and health outcomes 4. Motivational interviewing (Noonan & Moyers, 2009) 5. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2002) 6. Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2022) | 5 | 8.47 |

| Not reported | 54 | 91.53 |

| Characteristic . | Category . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | 2 | 3.39 |

| Canada | 4 | 6.78 | |

| China | 16 | 27.11 | |

| Germany | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Iran | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Japan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Jordan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 3.39 | |

| South Korea | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Spain | 2 | 3.39 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Turkey | 7 | 11.86 | |

| United States | 15 | 25.42 | |

| Study design | Randomized | 35 | 40.68 |

| Non-randomized | 24 | 59.32 | |

| Sample size | ≥100 | 18 | 30.51 |

| <100 | 41 | 69.49 | |

| Gender | Mixed | 46 | 77.97 |

| Males only | 1 | 1.69 | |

| Females only | 12 | 20.34 | |

| Participant background | Existing mental health condition (Anxiety) | 8 | 13.56 |

| Existing mental health condition (Depression) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Enrolled as part of a course | 9 | 15.25 | |

| Referred to from psychology clinic | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Healthy (Physically/Mentally) | 10 | 16.94 | |

| Others (e.g. fatigue, poor sleep quality, stress, experience of negative life event, dance experience) | 6 | 10.17 | |

| Not reported | 22 | 37.29 | |

| Intervention duration | 4–6 weeks | 14 | 23.73 |

| 7–9 weeks | 18 | 30.51 | |

| 10–12 weeks | 17 | 28.81 | |

| >12 weeks | 10 | 16.95 | |

| Intervention frequency | 1–2 times per week | 23 | 38.98 |

| 3–4 times per week | 22 | 37.29 | |

| 5–7 times/week | 8 | 13.56 | |

| Other (gradual increase/self-directed) | 2 | 3.39 | |

| Not reported | 4 | 6.78 | |

| Session duration | 0–30 min | 10 | 16.95 |

| 30–60 min | 18 | 30.51 | |

| ≥60 min | 11 | 18.64 | |

| Not reported | 20 | 33.90 | |

| Type of physical activity* | Aerobic exercise (including dancing, walking, cheerleading and structured ball sports) | 41 | 54.66 |

| Strength training | 15 | 20 | |

| Low-intensity/Low-impact exercise (including pilates, Tai Chi Quan, yoga, Ba Duan Jin, Kuok Sun Do) | 19 | 25.33 | |

| Education only | 3 | 4 | |

| Intervention fidelity measures** | Reported | 30 | 50.85 |

| Not reported | 29 | 49.15 | |

| Measurement of physical activity | Reported | 8 | 13.56 |

| Not reported | 51 | 86.44 | |

| Intervention based on theory | Yes (list of theories used) 1. SAAFE principles (Lubans et al., 2017) 2. SMART goal setting Doran, 1981, 3. Nies and Kershaw, (2002) model of PA and health outcomes 4. Motivational interviewing (Noonan & Moyers, 2009) 5. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2002) 6. Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2022) | 5 | 8.47 |

| Not reported | 54 | 91.53 |

Note. *Some interventions had more than one type of physical activity. ** Intervention fidelity was assessed according to whether authors reported attendance/adherence to the prescribed physical activity program.

| Studies in meta-analysis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention and duration . | Sample Size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Abavisani et al., (2019) | RCT | Pilates (8 weeks) | 62 (31 PA; 31 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Demir (2011) | RCT | Dance (12 weeks) | 120 (60 PA; 60 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Tekin (2008) | Non-RCT | Mixed (gymnastics, volleyball, athletics) (6 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Aşçı, (2002) | RCT | Step dance (10 weeks) | 40 (20 PA, 20 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Balkin et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (6 weeks) | 90 (21 anaerobic, 46 aerobic, 13 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Choi et al., (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (9 weeks) | 63 (33 PA; 30 control) | Stress | Yes | Weak |

| de Vries et al., (2017) | RCT | Low-intensity running (6 weeks) | 97 (49 PA; 48 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Eather et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training (8 weeks) | 53 (27 PA; 26 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 89 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al. (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Online only | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Strong |

| Hemat-Far et al. (2007) | RCT | Running (8 weeks) | 20 (10 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Ji et al., (2022) | RCT | Team sports, strength and aerobic exercises (7 weeks) | 197 (66 team sports; 64 individual strength and aerobic training; 67 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Kuok Sun Do (4 weeks) | 18 (7 PA; 11 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Li and Li (2017) | RCT | Running and strength training (14 weeks) | 37 (19 PA; 19 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2022) | RCT | Resistance training (8 weeks) | 27 (13 PA; 14 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Ning (2020) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (20 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Paolucci et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity training (6 weeks) | 55 (18 HIIT; 19 mod-intensity training; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Roth and Holmes, (2014) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (11 weeks) | 55 (18 aerobic; 19 relaxation; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Moderate |

| Xiao et al., (2021) | RCT | Basketball and baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 96 (31 basketball, 31 baduanjin, 34 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Yigiter and Hardee (2017) | RCT | Tennis and unspecified aerobic exercises (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Zhang et al., (2023) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (8 weeks) | 18 (9 PA; 9 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Moderate |

| Zheng et al., (2015) Zheng et al. (2015) (Zheng et al., 2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Studies in meta-analysis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention and duration . | Sample Size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Abavisani et al., (2019) | RCT | Pilates (8 weeks) | 62 (31 PA; 31 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Demir (2011) | RCT | Dance (12 weeks) | 120 (60 PA; 60 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Tekin (2008) | Non-RCT | Mixed (gymnastics, volleyball, athletics) (6 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Aşçı, (2002) | RCT | Step dance (10 weeks) | 40 (20 PA, 20 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Balkin et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (6 weeks) | 90 (21 anaerobic, 46 aerobic, 13 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Choi et al., (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (9 weeks) | 63 (33 PA; 30 control) | Stress | Yes | Weak |

| de Vries et al., (2017) | RCT | Low-intensity running (6 weeks) | 97 (49 PA; 48 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Eather et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training (8 weeks) | 53 (27 PA; 26 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 89 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al. (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Online only | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Strong |

| Hemat-Far et al. (2007) | RCT | Running (8 weeks) | 20 (10 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Ji et al., (2022) | RCT | Team sports, strength and aerobic exercises (7 weeks) | 197 (66 team sports; 64 individual strength and aerobic training; 67 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Kuok Sun Do (4 weeks) | 18 (7 PA; 11 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Li and Li (2017) | RCT | Running and strength training (14 weeks) | 37 (19 PA; 19 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2022) | RCT | Resistance training (8 weeks) | 27 (13 PA; 14 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Ning (2020) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (20 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Paolucci et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity training (6 weeks) | 55 (18 HIIT; 19 mod-intensity training; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Roth and Holmes, (2014) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (11 weeks) | 55 (18 aerobic; 19 relaxation; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Moderate |

| Xiao et al., (2021) | RCT | Basketball and baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 96 (31 basketball, 31 baduanjin, 34 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Yigiter and Hardee (2017) | RCT | Tennis and unspecified aerobic exercises (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Zhang et al., (2023) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (8 weeks) | 18 (9 PA; 9 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Moderate |

| Zheng et al., (2015) Zheng et al. (2015) (Zheng et al., 2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Studies in narrative synthesis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention . | Sample size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Pilates (6 weeks) | 30 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Alsaraireh and Aloush, (2017) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (10 weeks) | 181 (90 exercise, 91 meditation) | Depression (*) | No | Moderate |

| Arbinaga et al. (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 141 (G1 no exercise, 13; G2, 15; G3, 17; G4, 21) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| BARĞI, (2022) | RCT | PA counselling (walking; 4 weeks) | 31 (15 PA, 16 control) | Anxiety (+) Depression (/) | No | Moderate |

| Berger and Owen (1987) | Non-RCT | Swimming (14 weeks, study 1; 5 weeks, study 2) | 100 (study 1: 52, study 2: 48—all were in swimming) | Anxiety (/) | No | Weak |

| Biber and Knoll, (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Strength training (12 weeks) | 9 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Caldwell et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Tai Chi Quan (15 weeks) | 208 (76 taijiquan; 132 lectures/discussions control group) | Mindfulness (+) Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Deng et al., (2022) | Single-arm non-RCT | Cheerleading (16 weeks) | 63 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 99 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological health (*) Social relationships (*) | No | Weak |

| Forseth et al., (2022) | Non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 99 (44 PA; 45 control) | Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Fukui et al., (2021) | RCT | Strength training and balance exercises (8 weeks) | 88 (39 PA; 49 control) | Psychological distress (+) Psychological wellbeing (+) Quality of life (/) | No | Weak |

| Gaskins et al., (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 19 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al., (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Social function/Loneliness (+) | No | Weak |

| Hamed et al., (2021) | RCT | Running, cycling and strength training (8 weeks) | 54 (27 PA; 27 control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Lab Study | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (+) Coping strategy (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (+) | No | Strong |

| Huang (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (4 weeks) | 240 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Johnston et al., (2020) | Non-RCT | Running, dance, volleyball and soccer (12 weeks) | 291 (138 team sports; 153 aerobic) | Anxiety (+) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Yoga (12 weeks) | 27 (12 PA; 15 control) | Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Li and Liu, (2013) | Single-arm non-RCT | Running (16 weeks) | 68 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Causes of stress (*) | No | Moderate |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Mailey et al. (2010) | RCT | N/A—theory-focused intervention (12 weeks) | 47 (24 PA; 23 control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | Yes | Weak |

| Margulis et al., (2021) | Non-RCT | Volleyball, soccer and strength training (12 weeks) | 355 (140 team sports; 215 strength training) | Anxiety (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| McCann and Holmes, (2006) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (10 weeks) | 43 (15 aerobic; 14 placebos; 14 control) | Depression (+) | No | Weak |

| McFadden et al., (2017) | Single-arm non-RCT | PA counselling—no specifics provided (8 weeks) | 4 (no control) | Depression (*) | Yes | Weak |

| Murray et al., (2022) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic training and resistance training (8 weeks) | 74 (46 PA; 28 mindful) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | No | Strong |

| Sabourin et al., (2016) | RCT | Running (14 weeks) | 154 (125 CBT; 67 PA) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Distress (*) | No | Weak |

| Salehian et al., (2021) | RCT | Qigong and resilience training (12 weeks) | 45 (15 qigong; 15 resilience; 15 control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Schmalzl et al., (2018) | RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 40 (22 movement; 18 breath) | Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Severtsen and Bruya, (2010) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 10 (5 aerobic; 5 meditation) | Stress (*) Social readjustment/Loneliness (*) | No | Weak |

| Sharp and Caperchione, (2016) | RCT | Walking (12 weeks) | 137 (72 PA; 65 control) | Psychological wellbeing (/) Mental health status (−) | Yes | Weak |

| Sun et al., (2022) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (16 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Terzioğlu et al., (2022) | RCT | Mindfulness-based stretching (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological wellbeing (+) | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Psychological wellbeing (*) | No | Moderate |

| Tong et al., (2020) | RCT | Yoga, running and strength training (12 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Stress (+) Mindfulness (+) | No | Weak |

| Tucker and Maxwell, (2011) | Non-RCT | Strength training (15 weeks) | 152 (60 PA; 92 control) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| Wang et al., (2023) | RCT | Aerobic and resistance exercises (8 weeks) | 49 (24 HIIT, 25 aerobic) | Psychological symptoms (/) | No | Moderate |

| Yazici et al., (2016) | Single-arm non-RCT | Tennis (13 weeks) | 76 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Moderate |

| Zhang and Luo, (2020) | Non-RCT | Water sports (8 weeks) | 800 (400 PA; 400 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Psychological symptoms (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2021) | RCT | Dance (8 weeks) | 181 (90 PA; 91 control) | Anxiety (*) Loneliness (*) Psychological stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Studies in narrative synthesis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention . | Sample size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Pilates (6 weeks) | 30 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Alsaraireh and Aloush, (2017) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (10 weeks) | 181 (90 exercise, 91 meditation) | Depression (*) | No | Moderate |

| Arbinaga et al. (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 141 (G1 no exercise, 13; G2, 15; G3, 17; G4, 21) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| BARĞI, (2022) | RCT | PA counselling (walking; 4 weeks) | 31 (15 PA, 16 control) | Anxiety (+) Depression (/) | No | Moderate |

| Berger and Owen (1987) | Non-RCT | Swimming (14 weeks, study 1; 5 weeks, study 2) | 100 (study 1: 52, study 2: 48—all were in swimming) | Anxiety (/) | No | Weak |

| Biber and Knoll, (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Strength training (12 weeks) | 9 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Caldwell et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Tai Chi Quan (15 weeks) | 208 (76 taijiquan; 132 lectures/discussions control group) | Mindfulness (+) Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Deng et al., (2022) | Single-arm non-RCT | Cheerleading (16 weeks) | 63 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 99 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological health (*) Social relationships (*) | No | Weak |

| Forseth et al., (2022) | Non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 99 (44 PA; 45 control) | Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Fukui et al., (2021) | RCT | Strength training and balance exercises (8 weeks) | 88 (39 PA; 49 control) | Psychological distress (+) Psychological wellbeing (+) Quality of life (/) | No | Weak |

| Gaskins et al., (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 19 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al., (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Social function/Loneliness (+) | No | Weak |

| Hamed et al., (2021) | RCT | Running, cycling and strength training (8 weeks) | 54 (27 PA; 27 control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Lab Study | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (+) Coping strategy (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (+) | No | Strong |

| Huang (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (4 weeks) | 240 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Johnston et al., (2020) | Non-RCT | Running, dance, volleyball and soccer (12 weeks) | 291 (138 team sports; 153 aerobic) | Anxiety (+) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Yoga (12 weeks) | 27 (12 PA; 15 control) | Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Li and Liu, (2013) | Single-arm non-RCT | Running (16 weeks) | 68 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Causes of stress (*) | No | Moderate |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Mailey et al. (2010) | RCT | N/A—theory-focused intervention (12 weeks) | 47 (24 PA; 23 control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | Yes | Weak |

| Margulis et al., (2021) | Non-RCT | Volleyball, soccer and strength training (12 weeks) | 355 (140 team sports; 215 strength training) | Anxiety (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| McCann and Holmes, (2006) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (10 weeks) | 43 (15 aerobic; 14 placebos; 14 control) | Depression (+) | No | Weak |

| McFadden et al., (2017) | Single-arm non-RCT | PA counselling—no specifics provided (8 weeks) | 4 (no control) | Depression (*) | Yes | Weak |

| Murray et al., (2022) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic training and resistance training (8 weeks) | 74 (46 PA; 28 mindful) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | No | Strong |

| Sabourin et al., (2016) | RCT | Running (14 weeks) | 154 (125 CBT; 67 PA) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Distress (*) | No | Weak |

| Salehian et al., (2021) | RCT | Qigong and resilience training (12 weeks) | 45 (15 qigong; 15 resilience; 15 control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Schmalzl et al., (2018) | RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 40 (22 movement; 18 breath) | Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Severtsen and Bruya, (2010) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 10 (5 aerobic; 5 meditation) | Stress (*) Social readjustment/Loneliness (*) | No | Weak |

| Sharp and Caperchione, (2016) | RCT | Walking (12 weeks) | 137 (72 PA; 65 control) | Psychological wellbeing (/) Mental health status (−) | Yes | Weak |

| Sun et al., (2022) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (16 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Terzioğlu et al., (2022) | RCT | Mindfulness-based stretching (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological wellbeing (+) | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Psychological wellbeing (*) | No | Moderate |

| Tong et al., (2020) | RCT | Yoga, running and strength training (12 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Stress (+) Mindfulness (+) | No | Weak |

| Tucker and Maxwell, (2011) | Non-RCT | Strength training (15 weeks) | 152 (60 PA; 92 control) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| Wang et al., (2023) | RCT | Aerobic and resistance exercises (8 weeks) | 49 (24 HIIT, 25 aerobic) | Psychological symptoms (/) | No | Moderate |

| Yazici et al., (2016) | Single-arm non-RCT | Tennis (13 weeks) | 76 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Moderate |

| Zhang and Luo, (2020) | Non-RCT | Water sports (8 weeks) | 800 (400 PA; 400 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Psychological symptoms (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2021) | RCT | Dance (8 weeks) | 181 (90 PA; 91 control) | Anxiety (*) Loneliness (*) Psychological stress (*) | No | Weak |

Note: Specific behavioural change theories are mentioned in text. Some studies do not report the specific aerobic/anaerobic exercise. Weight training and strength training were used interchangeably and had been standardized as strength training here. Legend: + (statistically positive effect); − (statistically negative effect); / (statistically non-significant effect); * (insufficient evidence).

| Studies in meta-analysis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention and duration . | Sample Size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Abavisani et al., (2019) | RCT | Pilates (8 weeks) | 62 (31 PA; 31 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Demir (2011) | RCT | Dance (12 weeks) | 120 (60 PA; 60 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Tekin (2008) | Non-RCT | Mixed (gymnastics, volleyball, athletics) (6 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Aşçı, (2002) | RCT | Step dance (10 weeks) | 40 (20 PA, 20 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Balkin et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (6 weeks) | 90 (21 anaerobic, 46 aerobic, 13 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Choi et al., (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (9 weeks) | 63 (33 PA; 30 control) | Stress | Yes | Weak |

| de Vries et al., (2017) | RCT | Low-intensity running (6 weeks) | 97 (49 PA; 48 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Eather et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training (8 weeks) | 53 (27 PA; 26 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 89 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al. (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Online only | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Strong |

| Hemat-Far et al. (2007) | RCT | Running (8 weeks) | 20 (10 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Ji et al., (2022) | RCT | Team sports, strength and aerobic exercises (7 weeks) | 197 (66 team sports; 64 individual strength and aerobic training; 67 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Kuok Sun Do (4 weeks) | 18 (7 PA; 11 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Li and Li (2017) | RCT | Running and strength training (14 weeks) | 37 (19 PA; 19 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2022) | RCT | Resistance training (8 weeks) | 27 (13 PA; 14 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Ning (2020) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (20 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Paolucci et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity training (6 weeks) | 55 (18 HIIT; 19 mod-intensity training; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Roth and Holmes, (2014) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (11 weeks) | 55 (18 aerobic; 19 relaxation; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Moderate |

| Xiao et al., (2021) | RCT | Basketball and baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 96 (31 basketball, 31 baduanjin, 34 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Yigiter and Hardee (2017) | RCT | Tennis and unspecified aerobic exercises (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Zhang et al., (2023) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (8 weeks) | 18 (9 PA; 9 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Moderate |

| Zheng et al., (2015) Zheng et al. (2015) (Zheng et al., 2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Studies in meta-analysis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention and duration . | Sample Size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Abavisani et al., (2019) | RCT | Pilates (8 weeks) | 62 (31 PA; 31 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Demir (2011) | RCT | Dance (12 weeks) | 120 (60 PA; 60 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Akandere and Tekin (2008) | Non-RCT | Mixed (gymnastics, volleyball, athletics) (6 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Aşçı, (2002) | RCT | Step dance (10 weeks) | 40 (20 PA, 20 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Balkin et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (6 weeks) | 90 (21 anaerobic, 46 aerobic, 13 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Choi et al., (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (9 weeks) | 63 (33 PA; 30 control) | Stress | Yes | Weak |

| de Vries et al., (2017) | RCT | Low-intensity running (6 weeks) | 97 (49 PA; 48 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Eather et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training (8 weeks) | 53 (27 PA; 26 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 89 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al. (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Online only | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Strong |

| Hemat-Far et al. (2007) | RCT | Running (8 weeks) | 20 (10 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Ji et al., (2022) | RCT | Team sports, strength and aerobic exercises (7 weeks) | 197 (66 team sports; 64 individual strength and aerobic training; 67 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Kuok Sun Do (4 weeks) | 18 (7 PA; 11 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Li and Li (2017) | RCT | Running and strength training (14 weeks) | 37 (19 PA; 19 control) | Anxiety | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Li et al., (2022) | RCT | Resistance training (8 weeks) | 27 (13 PA; 14 control) | Anxiety | No | Moderate |

| Ning (2020) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (20 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Weak |

| Paolucci et al., (2018) | RCT | High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity training (6 weeks) | 55 (18 HIIT; 19 mod-intensity training; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Roth and Holmes, (2014) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (11 weeks) | 55 (18 aerobic; 19 relaxation; 18 control) | Anxiety, depression, stress | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Depression | No | Moderate |

| Xiao et al., (2021) | RCT | Basketball and baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 96 (31 basketball, 31 baduanjin, 34 control) | Anxiety, stress | No | Weak |

| Yigiter and Hardee (2017) | RCT | Tennis and unspecified aerobic exercises (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Depression | No | Weak |

| Zhang et al., (2023) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (8 weeks) | 18 (9 PA; 9 control) | Anxiety, depression | No | Moderate |

| Zheng et al., (2015) Zheng et al. (2015) (Zheng et al., 2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Stress | No | Weak |

| Studies in narrative synthesis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention . | Sample size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Pilates (6 weeks) | 30 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Alsaraireh and Aloush, (2017) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (10 weeks) | 181 (90 exercise, 91 meditation) | Depression (*) | No | Moderate |

| Arbinaga et al. (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 141 (G1 no exercise, 13; G2, 15; G3, 17; G4, 21) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| BARĞI, (2022) | RCT | PA counselling (walking; 4 weeks) | 31 (15 PA, 16 control) | Anxiety (+) Depression (/) | No | Moderate |

| Berger and Owen (1987) | Non-RCT | Swimming (14 weeks, study 1; 5 weeks, study 2) | 100 (study 1: 52, study 2: 48—all were in swimming) | Anxiety (/) | No | Weak |

| Biber and Knoll, (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Strength training (12 weeks) | 9 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Caldwell et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Tai Chi Quan (15 weeks) | 208 (76 taijiquan; 132 lectures/discussions control group) | Mindfulness (+) Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Deng et al., (2022) | Single-arm non-RCT | Cheerleading (16 weeks) | 63 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 99 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological health (*) Social relationships (*) | No | Weak |

| Forseth et al., (2022) | Non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 99 (44 PA; 45 control) | Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Fukui et al., (2021) | RCT | Strength training and balance exercises (8 weeks) | 88 (39 PA; 49 control) | Psychological distress (+) Psychological wellbeing (+) Quality of life (/) | No | Weak |

| Gaskins et al., (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 19 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al., (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Social function/Loneliness (+) | No | Weak |

| Hamed et al., (2021) | RCT | Running, cycling and strength training (8 weeks) | 54 (27 PA; 27 control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Lab Study | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (+) Coping strategy (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (+) | No | Strong |

| Huang (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (4 weeks) | 240 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Johnston et al., (2020) | Non-RCT | Running, dance, volleyball and soccer (12 weeks) | 291 (138 team sports; 153 aerobic) | Anxiety (+) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Yoga (12 weeks) | 27 (12 PA; 15 control) | Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Li and Liu, (2013) | Single-arm non-RCT | Running (16 weeks) | 68 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Causes of stress (*) | No | Moderate |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Mailey et al. (2010) | RCT | N/A—theory-focused intervention (12 weeks) | 47 (24 PA; 23 control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | Yes | Weak |

| Margulis et al., (2021) | Non-RCT | Volleyball, soccer and strength training (12 weeks) | 355 (140 team sports; 215 strength training) | Anxiety (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| McCann and Holmes, (2006) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (10 weeks) | 43 (15 aerobic; 14 placebos; 14 control) | Depression (+) | No | Weak |

| McFadden et al., (2017) | Single-arm non-RCT | PA counselling—no specifics provided (8 weeks) | 4 (no control) | Depression (*) | Yes | Weak |

| Murray et al., (2022) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic training and resistance training (8 weeks) | 74 (46 PA; 28 mindful) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | No | Strong |

| Sabourin et al., (2016) | RCT | Running (14 weeks) | 154 (125 CBT; 67 PA) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Distress (*) | No | Weak |

| Salehian et al., (2021) | RCT | Qigong and resilience training (12 weeks) | 45 (15 qigong; 15 resilience; 15 control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Schmalzl et al., (2018) | RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 40 (22 movement; 18 breath) | Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Severtsen and Bruya, (2010) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 10 (5 aerobic; 5 meditation) | Stress (*) Social readjustment/Loneliness (*) | No | Weak |

| Sharp and Caperchione, (2016) | RCT | Walking (12 weeks) | 137 (72 PA; 65 control) | Psychological wellbeing (/) Mental health status (−) | Yes | Weak |

| Sun et al., (2022) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (16 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Terzioğlu et al., (2022) | RCT | Mindfulness-based stretching (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological wellbeing (+) | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Psychological wellbeing (*) | No | Moderate |

| Tong et al., (2020) | RCT | Yoga, running and strength training (12 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Stress (+) Mindfulness (+) | No | Weak |

| Tucker and Maxwell, (2011) | Non-RCT | Strength training (15 weeks) | 152 (60 PA; 92 control) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| Wang et al., (2023) | RCT | Aerobic and resistance exercises (8 weeks) | 49 (24 HIIT, 25 aerobic) | Psychological symptoms (/) | No | Moderate |

| Yazici et al., (2016) | Single-arm non-RCT | Tennis (13 weeks) | 76 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Moderate |

| Zhang and Luo, (2020) | Non-RCT | Water sports (8 weeks) | 800 (400 PA; 400 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Psychological symptoms (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2021) | RCT | Dance (8 weeks) | 181 (90 PA; 91 control) | Anxiety (*) Loneliness (*) Psychological stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Studies in narrative synthesis . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year . | Study design . | Intervention . | Sample size . | Mental health outcome(s) . | Behavioural theory . | Quality . |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Pilates (6 weeks) | 30 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Alsaraireh and Aloush, (2017) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise and strength training (10 weeks) | 181 (90 exercise, 91 meditation) | Depression (*) | No | Moderate |

| Arbinaga et al. (2018) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 141 (G1 no exercise, 13; G2, 15; G3, 17; G4, 21) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| BARĞI, (2022) | RCT | PA counselling (walking; 4 weeks) | 31 (15 PA, 16 control) | Anxiety (+) Depression (/) | No | Moderate |

| Berger and Owen (1987) | Non-RCT | Swimming (14 weeks, study 1; 5 weeks, study 2) | 100 (study 1: 52, study 2: 48—all were in swimming) | Anxiety (/) | No | Weak |

| Biber and Knoll, (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Strength training (12 weeks) | 9 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Caldwell et al., (2011) | Non-RCT | Tai Chi Quan (15 weeks) | 208 (76 taijiquan; 132 lectures/discussions control group) | Mindfulness (+) Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Deng et al., (2022) | Single-arm non-RCT | Cheerleading (16 weeks) | 63 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Erdoğan Yüce and Muz, (2020) | Non-RCT | Yoga (4 weeks) | 99 (44 yoga; 45 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological health (*) Social relationships (*) | No | Weak |

| Forseth et al., (2022) | Non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 99 (44 PA; 45 control) | Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Fukui et al., (2021) | RCT | Strength training and balance exercises (8 weeks) | 88 (39 PA; 49 control) | Psychological distress (+) Psychological wellbeing (+) Quality of life (/) | No | Weak |

| Gaskins et al., (2020) | Single-arm non-RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 19 (no control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Ghorbani et al., (2014) | RCT | Running and rope skipping (6 weeks) | 30 (15 PA; 15 control) | Social function/Loneliness (+) | No | Weak |

| Hamed et al., (2021) | RCT | Running, cycling and strength training (8 weeks) | 54 (27 PA; 27 control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Herbert et al. (2020) Lab Study | RCT | Cardiovascular and muscular endurance exercises (6 weeks) | Online study: 61 (30 PA; 31 waitlist control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (+) Coping strategy (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (+) | No | Strong |

| Huang (2021) | Single-arm non-RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (4 weeks) | 240 (no control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Johnston et al., (2020) | Non-RCT | Running, dance, volleyball and soccer (12 weeks) | 291 (138 team sports; 153 aerobic) | Anxiety (+) Depression (*) Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Kim, (2014) | RCT | Yoga (12 weeks) | 27 (12 PA; 15 control) | Stress (+) | No | Weak |

| Li and Liu, (2013) | Single-arm non-RCT | Running (16 weeks) | 68 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Causes of stress (*) | No | Moderate |

| Li et al., (2015) | RCT | Baduanjin exercise (12 weeks) | 206 (101 PA; 105 control) | Quality of life (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Mailey et al. (2010) | RCT | N/A—theory-focused intervention (12 weeks) | 47 (24 PA; 23 control) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | Yes | Weak |

| Margulis et al., (2021) | Non-RCT | Volleyball, soccer and strength training (12 weeks) | 355 (140 team sports; 215 strength training) | Anxiety (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| McCann and Holmes, (2006) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (10 weeks) | 43 (15 aerobic; 14 placebos; 14 control) | Depression (+) | No | Weak |

| McFadden et al., (2017) | Single-arm non-RCT | PA counselling—no specifics provided (8 weeks) | 4 (no control) | Depression (*) | Yes | Weak |

| Murray et al., (2022) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic training and resistance training (8 weeks) | 74 (46 PA; 28 mindful) | Anxiety (/) Depression (/) | No | Strong |

| Sabourin et al., (2016) | RCT | Running (14 weeks) | 154 (125 CBT; 67 PA) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Distress (*) | No | Weak |

| Salehian et al., (2021) | RCT | Qigong and resilience training (12 weeks) | 45 (15 qigong; 15 resilience; 15 control) | Stress (*) | No | Weak |

| Schmalzl et al., (2018) | RCT | Yoga (8 weeks) | 40 (22 movement; 18 breath) | Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Severtsen and Bruya, (2010) | RCT | Unspecified aerobic exercise (7 weeks) | 10 (5 aerobic; 5 meditation) | Stress (*) Social readjustment/Loneliness (*) | No | Weak |

| Sharp and Caperchione, (2016) | RCT | Walking (12 weeks) | 137 (72 PA; 65 control) | Psychological wellbeing (/) Mental health status (−) | Yes | Weak |

| Sun et al., (2022) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (16 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Terzioğlu et al., (2022) | RCT | Mindfulness-based stretching (8 weeks) | 60 (30 PA; 30 control) | Psychological wellbeing (+) | No | Weak |

| Tomar et al., (2023) | Non-RCT | Recreational team sports (12 weeks) | 26 (16 PA; 10 control) | Psychological wellbeing (*) | No | Moderate |

| Tong et al., (2020) | RCT | Yoga, running and strength training (12 weeks) | 143 (67 Yoga; 67 fitness) | Stress (+) Mindfulness (+) | No | Weak |

| Tucker and Maxwell, (2011) | Non-RCT | Strength training (15 weeks) | 152 (60 PA; 92 control) | Wellbeing (+) | No | Moderate |

| Wang et al., (2023) | RCT | Aerobic and resistance exercises (8 weeks) | 49 (24 HIIT, 25 aerobic) | Psychological symptoms (/) | No | Moderate |

| Yazici et al., (2016) | Single-arm non-RCT | Tennis (13 weeks) | 76 (no control) | Anxiety (*) Depression (*) Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Moderate |

| Zhang and Luo, (2020) | Non-RCT | Water sports (8 weeks) | 800 (400 PA; 400 control) | Psychological symptoms (*) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2015) | RCT | Tai Chi Quan (12 weeks) | 195 (92 PA; 103 control) | Psychological symptoms (/) Quality of life (/) Stress (/) | No | Weak |

| Zheng et al., (2021) | RCT | Dance (8 weeks) | 181 (90 PA; 91 control) | Anxiety (*) Loneliness (*) Psychological stress (*) | No | Weak |

Note: Specific behavioural change theories are mentioned in text. Some studies do not report the specific aerobic/anaerobic exercise. Weight training and strength training were used interchangeably and had been standardized as strength training here. Legend: + (statistically positive effect); − (statistically negative effect); / (statistically non-significant effect); * (insufficient evidence).

Meta-analysis findings

The pooled effects indicated that the PA interventions showed moderate to large effects (Cohen, 2013) in reducing poor mental health outcomes in undergraduate students in terms of anxiety (N = 20, pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) = −0.88, 95% CI [−1.23, −0.52]), depression (N = 14, pooled SMD = −0.73, 95% CI [−1.00, −0.47]) and stress (N = 11, pooled SMD = −0.61, 95% CI [−0.94, −0.28]). Heterogeneity was moderately high and statistically significant for anxiety (I2 = 90.29%; Q(19) = 195.61, p < 0.001), depression (I2 = 49.66%; Q(13) = 25.82, p = 0.02) and stress (I2 = 86.97%; Q(10) = 76.74, p < 0.001). A list of the studies included in the meta-analysis can be found in Table 2. The variable findings underpinning heterogeneity were mostly in the form of almost all studies pointing towards benefit but to differing degrees (as can be seen in the forest plots for anxiety, depression and stress presented in Figure 2), rather than a mix of studies showing benefits and detrimental impacts. Begg’s test for publication bias was not statistically significant for anxiety (z = −0.32, p = 0.795) and depression (z = −0.88, p = 0.443), but was significant for stress (z = −2.18, p = 0.043). The trimmed and filled estimate for stress was (−0.22, 95% CI [−0.31, −0.14]).

(a) Forest Plot for Anxiety. (b) Forest Plot for Depression. (c) Forest Plot for Stress after removing Kim, (2014).

The leave-one-out sensitivity analyses indicated the findings for anxiety and depression were robust to study inclusion, with pooled effects remaining moderately sized and statistically significant regardless of which studies were included, with results ranging from −0.77, 95% CI [−1.00, −0.54] to −0.92, 95% CI [−1.28, −0.57] for anxiety and −0.68, 95% CI [−0.94, −0.41] to −0.79, 95% CI [−1.05, −0.43] for depression, still with significant heterogeneity. Conclusions regarding stress were affected by study inclusion. The omission of most studies did not affect the pooled effects, which ranged from −0.58, 95% CI [−0.92, −0.24] to −0.72, 95% CI [−1.08, −0.36]. However, omitting the findings of Kim, (2014), led to a much smaller effect, −0.34, 95% CI [−0.53, −0.14], which was still heterogeneous (I2 = 58.47%; Q(9) = 21.67, p = 0.01) but no longer showed small study effects (z = −1.97, p = 0.074). Pooled effects in the trimmed and filled analyses were −0.26, 95% CI [−0.45, −0.07] after omitting Kim (2014).

Narrative synthesis results

The narrative synthesis included 40 studies that reported on 12 mental health outcomes. Descriptive data for studies included in the narrative synthesis are summarized in Table 2 and a synthesis of findings per outcome is available in Supplementary Material A, Table S4. Anxiety, depression and stress were the most assessed mental health outcomes in studies included in the narrative synthesis, which is consistent with the outcomes included in the meta-analyses. Overall, across outcomes, the synthesis of findings showed 22% positive effects, 26% insignificant effects and only about 1% negative effects. However, 51% (37 out of 73) instances were unable to be coded due to a lack of appropriate statistical analyses (e.g. use of independent samples t-tests instead of ANOVAs, even where comparison groups were available), a lack of reporting of group by time interactions, or studies using single-arm trials with no comparison group. When looking at specific outcomes, psychological wellbeing had the highest proportion of statistically significant positive effects (4 out of 6, or 67%).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of PA interventions on undergraduate students’ mental health outcomes. Meta-analyses showed that PA interventions had a significant, moderate effect on reducing anxiety and depression and an uncertain (moderate or smaller), but significant, effect on reducing stress. In contrast, the narrative synthesis found mixed findings for the effectiveness of PA interventions in improving mental health outcomes in undergraduate students, with only 22% significant positive effects across 12 different mental health outcomes. Across both the meta-analyses and narrative synthesis, we observed significant variability in the parameters of prescribed PA interventions (e.g. frequency, intensity, duration and type). About 80% of included papers demonstrated low quality and the certainty of evidence (GRADE) was very low for the three outcomes included in meta-analyses. Findings should be interpreted with this information in mind.

The findings from our meta-analyses are generally consistent with existing literature, which suggests that engaging in PA can be beneficial to university students’ mental health (e.g. Hrafnkelsdottir et al., 2018; Román-Mata et al., 2020; Reyes-Molina et al., 2022; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2022). Our findings are also consistent with those of a scoping review focusing on the impact of PA on the mental health of young people aged 12–26 years (Pascoe et al., 2020), with both studies indicating positive improvements for anxiety and depression but our results also supporting improvements in symptoms of stress. Specifically focusing on university students, our findings complement those of a previous systematic review and meta-analysis that reported that PA interventions increased moderate intensity PA in university students (Plotnikoff et al., 2015), by also showing that PA interventions can benefit mental health outcomes. Recent data suggest that while participation rates are still low, university students are amongst the most physically active, but still experience the highest onsets of mental health disorders compared to other age groups (ABS, 2023). One possible explanation could be the gap between university students’ understanding of PA as a mental health strategy (Dingle et al., 2022). Future research could address the discrepancy between students’ knowledge of PA as a coping strategy to mitigate the effects of poor mental health and the actual utilization of PA.