-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nicole Ide, James P LoGerfo, Biraj Karmacharya, Barriers and facilitators of diabetes services in Nepal: a qualitative evaluation, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 33, Issue 4, May 2018, Pages 474–482, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

For the past three decades, the burden of diabetes in Nepal has been steadily increasing, with an estimated 3% annual increase since the year 2000. Although the burden is increasing, the methods of addressing the challenge have remained largely unchanged. This study sought to assess the current state of diabetes services provided by health facilities and to identify the major barriers that people with diabetes commonly face in Nepal. For this qualitative study, we selected five health facilities of varying levels and locations. At each site, we employed three unique methods: a process evaluation of the diabetes treatment and prevention services available, in-depth interviews with patients and focus group discussions with community members without diabetes. We used thematic analysis to analyse the data. Our findings were organized into the five categories of the Ecological Model: Individual, Interpersonal, Organizational, Community and Public Policy. Sub-optimal knowledge and behaviors of patients often contributed to poor diabetes management, especially related to diet control, physical activity and initiation of drug treatment. Social support was often lacking. Organizational challenges included health provider shortages, long wait times, high patient loads and minimal time available to spend with patients, often resulting in incomprehensive care. Public policy challenges include limited services in rural settings and financial burden. The scarcity of financial and human resources for health in Nepal often results in the inability of the current healthcare system to provide comprehensive prevention and management services for chronic diseases. A multilevel, coordinated approach is necessary to address these concerns. In the short-term, adding community-based supplementary solutions outside of the traditional hospital-based model could help to increase access to affordable services.

Key Messages

In recent decades, the burden of diabetes in Nepal has rapidly increased, with a prevalence likely nearing 10%.

The current Nepali health system is not currently equipped to manage the growing number of people with diabetes and to provide adequate prevention, diagnosis and management services for diabetes.

People with diabetes in Nepal face a variety of significant barriers to managing their condition, including accessing affordable and convenient care, receiving comprehensive diabetes education and managing their lifestyle changes.

A multilevel, coordinated approach is necessary to bridge the current gap between the community and the health system to ensure equal access to diabetes services for all Nepali people.

Introduction

Nepal is undergoing a health transition with the burden of chronic, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) surpassing the burden of communicable diseases (MoHP Nepal 2012; IHME 2014; Aryal et al. 2014; Government of Nepal and World Health Organisation 2014; WHO 2014). Type 2 diabetes in particular is a growing problem in Nepal. Nepal has experienced an estimated 89% increase in the Years of Life Lost due to diabetes between 1990 and 2010 (IHME 2013). The increase is mainly attributed to rapid urbanization, sedentary lifestyle, unbalanced diet especially including a high intake of refined carbohydrates, and increased life expectancy resulting in an aging population (Hu 2011). To exacerbate the problem, it has also been established that South Asian populations are predisposed to higher diabetes risk and metabolic disorders (Yajnik 2009; Kanaya et al. 2014).

While the exact prevalence of diabetes in Nepal is not definitively known, some estimate the country-wide prevalence to be 9.1% (WHO 2016), and a systematic review conducted of prevalence studies reported a pooled prevalence of 8.4% (Gyawali et al. 2015). Urban prevalence is particularly high, with one estimate reporting an urban prevalence of 14.6% for adults over 20 (Singh and Bhattarai 2003). Many cases remain undiagnosed; for example, Shrestha et al. (2006) found that 54.4% of all the diabetes cases in their sample were undiagnosed.

Despite the magnitude of the burden, services for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of diabetes are limited in Nepal. Existing examples of effective strategies for controlling and managing diabetes were mostly developed outside Nepal and have not been tailored to meet the local Nepali context. In order to best meet the specific realities of the Nepali population and health system, we studied the outstanding needs, barriers, and bottlenecks to providing and receiving comprehensive diabetes services in Nepal. Specifically, we explored the strengths and weaknesses of current diabetes services; health service utilization patterns of people with diabetes, health behaviors, and barriers to care; and the diabetes-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices of a sample of community members without diabetes.

Methods

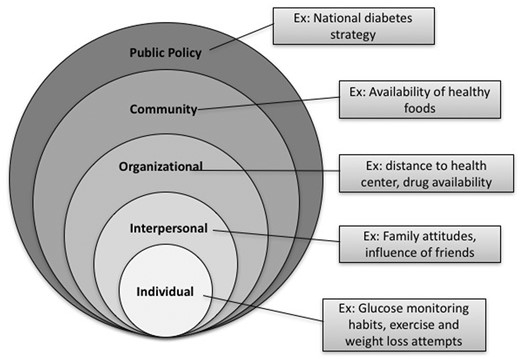

We adopted a qualitative, multilevel approach to understanding the current services, barriers and needs of diabetes programs in Nepal from the perspectives of the patient, the health system, and the community. Our framework (see Figure 1) is based on McLeroy et al.’s Ecological Model and Arthur Kleinman’s Explanatory Model (Kleinman 1978; McLeroy et al. 1988).

We selected a stratified, purposeful sample of five study sites for this research. To increase the generalizability of the results, we selected sites that represent a combination of urban and rural locations, including government, community and private health centers. The five sites are enumerated in Table 1. Three of the five sites were conducted in urban settings, including two large public hospitals and one small private clinic. One site was a rural setting, and another was in a suburban setting which serves as the tertiary hospital for many rural settings, thus representing a mix of suburban and rural participants. Interviews were conducted between November 2015 and March 2016.

| Study site . | Location . | Type of facility . | Setting . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahunepati Outreach Clinic | Sindhupalchowk | Rural Community Clinic | Rural |

| B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) | Dharan | Tertiary Semi-Autonomous Public Hospital | Urban |

| Dhulikhel Hospital—Kathmandu University Hospital | Kavrepalanchowk | Community Hospital | Suburban (small town) |

| Diabetes, Thyroid, and Endocrinology Care Center | Pokhara | Private Health Clinic | Urban |

| Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital | Kathmandu | Government Teaching Hospital | Urban |

| Study site . | Location . | Type of facility . | Setting . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahunepati Outreach Clinic | Sindhupalchowk | Rural Community Clinic | Rural |

| B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) | Dharan | Tertiary Semi-Autonomous Public Hospital | Urban |

| Dhulikhel Hospital—Kathmandu University Hospital | Kavrepalanchowk | Community Hospital | Suburban (small town) |

| Diabetes, Thyroid, and Endocrinology Care Center | Pokhara | Private Health Clinic | Urban |

| Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital | Kathmandu | Government Teaching Hospital | Urban |

| Study site . | Location . | Type of facility . | Setting . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahunepati Outreach Clinic | Sindhupalchowk | Rural Community Clinic | Rural |

| B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) | Dharan | Tertiary Semi-Autonomous Public Hospital | Urban |

| Dhulikhel Hospital—Kathmandu University Hospital | Kavrepalanchowk | Community Hospital | Suburban (small town) |

| Diabetes, Thyroid, and Endocrinology Care Center | Pokhara | Private Health Clinic | Urban |

| Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital | Kathmandu | Government Teaching Hospital | Urban |

| Study site . | Location . | Type of facility . | Setting . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahunepati Outreach Clinic | Sindhupalchowk | Rural Community Clinic | Rural |

| B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) | Dharan | Tertiary Semi-Autonomous Public Hospital | Urban |

| Dhulikhel Hospital—Kathmandu University Hospital | Kavrepalanchowk | Community Hospital | Suburban (small town) |

| Diabetes, Thyroid, and Endocrinology Care Center | Pokhara | Private Health Clinic | Urban |

| Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital | Kathmandu | Government Teaching Hospital | Urban |

To generate data from different perspectives, we utilized three unique methods and study populations in this research: Process Evaluations of diabetes programs, in-depth qualitative interviews with diabetes patients, and focus group discussions (FGDs) with community members without diabetes. Each method is described below.

Process evaluations: health provider perspective

At each facility, we conducted a process evaluation of the diabetes treatment and prevention services available through one-on-one interviews with health workers. Participants were identified using snowball sampling methods (Goodman 1961). We first identified the primary contact for the diabetes services in the facility, and requested him/her to provide the names of other clinic staff who are active in the provision of diabetes services. The lead researcher conducted interviews with staff, including clinic managers, doctors, nurses, dieticians, and diabetes educators. We conducted interviews in English using a structured questionnaire that lasted 30–60 min. Questions covered the following topics: program history and structure, patient profile, program activities, monitoring and evaluation activities and an open-ended section on the providers’ perspectives on the challenges, needs, and barriers to diabetes control in their clinic and throughout Nepal. The interview guide was modelled after the CDC Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health and ACI’s Framework for ‘Understanding Program Evaluation’ (CDC 1999; NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation 2013).

In-depth interviews: people with diabetes

We conducted individual in-depth interviews with people with diabetes at each of the five sites. Participants were eligible if they were at least age 18 and had previously been diagnosed with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes in a health facility at least 1 year prior to the interview. Participants were recruited using purposive stratified sampling methods aimed at maximum variation (Patton 2001). We visited each site during OPD clinic hours, and clinic staff assisted us by inviting patients who were attending the clinic that day to participate in an interview. Throughout the recruitment period, we made efforts to enrol a diverse set of participants in terms of gender, age, and educational/economic status. In order to avoid selection bias, we recruited some participants outside of the health facility using snowball sampling methods. We conducted all interviews in Nepali language using a qualitative, semi-structured questionnaire lasting between 45 and 90 min. The guide was originally written in English, then translated to Nepali, and back translated to English. The interview guide was pretested on individuals known to the study researchers and revised as necessary. Interview topics included: disease history; psychological and other life impacts of diabetes; monitoring and treatment habits; health expenditures; barriers to care; knowledge about healthy lifestyle; behaviour change practices; and social/family support.

FGDs: community members without diabetes

We held a FGD at each study site with community members without diabetes. We aimed to recruit between 7 and 10 participants for each FGD. Participants were eligible if they were at or above age 18, had never been diagnosed with diabetes or prediabetes, and did not live in the same household as someone with diabetes. Staff at study sites assisted in locating participants in the community for interview. We conducted focus groups in the Nepali language using a qualitative, semi-structured discussion guide. The FGD guide also went through the same translation and pretesting process as the in-depth interview questionnaire. FGD topics included: knowledge about diabetes; knowledge and attitudes about healthy lifestlyes; diet and exercise practices; and healthcare seeking behaviours.

Data management and analysis

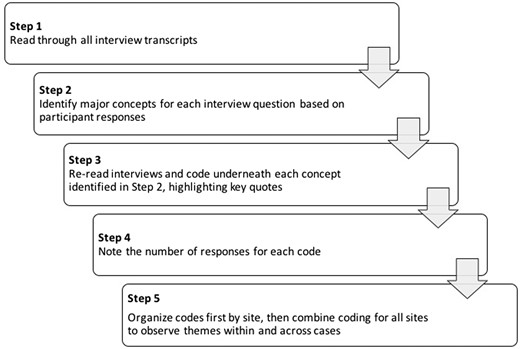

We voice-recorded all interviews, with participant permission. Afterwards, a research assistant translated each interview into English. Next, using Microsoft Word and Excel, the lead researcher performed data analysis using thematic analysis methods (see Figure 2). Each transcript was read thoroughly, and afterwards, the major concepts for each interview question were identified based on participant responses. Transcripts were read through again with inductive codes assigned underneath each concept. Key quotes for each code were noted. Finally, the number of responses for each code was counted. Codes were first organized separately by site; afterwards, data from each site were combined in order to explore overarching, across-site themes. Other members on the research team reviewed the codes and themes to provide feedback and validation of the findings.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the authors’ institute. Informed, written consent was received from each participant before each interview or FGD.

Results

Participant demographics

Among the five sites, we conducted a total of 17 interviews with health care staff, between 2 and 6 interviews per site. Participants included four clinic directors, five diabetes health educators, three dieticians, three medical officers, one auxiliary nurse midwife and one pharmacy director.

A total of 44 participants were selected for in-depth interviews, with a range of 6–10 participants per site. Exactly half of the patients were female, and the age range of the participants varied, with the majority (59%) falling between 45 and 64 years of age. Only 7% were <34 years of age. Half of the sample had at least some primary school education, with almost 30% having no education and 20% with post-secondary education. Of all in-depth interview participants, 38.6% self-reported to be using insulin at the time of interview and 56.8% reported using oral medications only. Two participants were not taking any type of medication at the time of interview. Demographics of these participants are displayed in Table 2.

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 3 (7) |

| 35–44 | 3 (7) |

| 45–54 | 13 (29.5) |

| 55–64 | 13 (29.5) |

| 65+ | 12 (27) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (50) |

| Female | 22 (50) |

| Education | |

| No education | 13 (29.5) |

| Primary school | 7 (16) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 15 (34) |

| Post-secondary | 9 (20.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 11 (26) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 6 (14) |

| Newar | 11 (26) |

| Janajati | 12 (29) |

| Dalits and others | 2 (5) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 7 (16) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 22 (51) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 9 (21) |

| More than 60 000 | 5 (12) |

| Family history of diabetes | |

| No one | 18 (41) |

| Extended family member only | 1 (2) |

| Immediate family member | 18 (41) |

| Don't know | 7 (16) |

| Medication use | |

| Insulin | 17 (39) |

| Oral medication only | 25 (57) |

| No medication | 2 (4) |

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 3 (7) |

| 35–44 | 3 (7) |

| 45–54 | 13 (29.5) |

| 55–64 | 13 (29.5) |

| 65+ | 12 (27) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (50) |

| Female | 22 (50) |

| Education | |

| No education | 13 (29.5) |

| Primary school | 7 (16) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 15 (34) |

| Post-secondary | 9 (20.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 11 (26) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 6 (14) |

| Newar | 11 (26) |

| Janajati | 12 (29) |

| Dalits and others | 2 (5) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 7 (16) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 22 (51) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 9 (21) |

| More than 60 000 | 5 (12) |

| Family history of diabetes | |

| No one | 18 (41) |

| Extended family member only | 1 (2) |

| Immediate family member | 18 (41) |

| Don't know | 7 (16) |

| Medication use | |

| Insulin | 17 (39) |

| Oral medication only | 25 (57) |

| No medication | 2 (4) |

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 3 (7) |

| 35–44 | 3 (7) |

| 45–54 | 13 (29.5) |

| 55–64 | 13 (29.5) |

| 65+ | 12 (27) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (50) |

| Female | 22 (50) |

| Education | |

| No education | 13 (29.5) |

| Primary school | 7 (16) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 15 (34) |

| Post-secondary | 9 (20.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 11 (26) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 6 (14) |

| Newar | 11 (26) |

| Janajati | 12 (29) |

| Dalits and others | 2 (5) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 7 (16) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 22 (51) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 9 (21) |

| More than 60 000 | 5 (12) |

| Family history of diabetes | |

| No one | 18 (41) |

| Extended family member only | 1 (2) |

| Immediate family member | 18 (41) |

| Don't know | 7 (16) |

| Medication use | |

| Insulin | 17 (39) |

| Oral medication only | 25 (57) |

| No medication | 2 (4) |

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 3 (7) |

| 35–44 | 3 (7) |

| 45–54 | 13 (29.5) |

| 55–64 | 13 (29.5) |

| 65+ | 12 (27) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (50) |

| Female | 22 (50) |

| Education | |

| No education | 13 (29.5) |

| Primary school | 7 (16) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 15 (34) |

| Post-secondary | 9 (20.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 11 (26) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 6 (14) |

| Newar | 11 (26) |

| Janajati | 12 (29) |

| Dalits and others | 2 (5) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 7 (16) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 22 (51) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 9 (21) |

| More than 60 000 | 5 (12) |

| Family history of diabetes | |

| No one | 18 (41) |

| Extended family member only | 1 (2) |

| Immediate family member | 18 (41) |

| Don't know | 7 (16) |

| Medication use | |

| Insulin | 17 (39) |

| Oral medication only | 25 (57) |

| No medication | 2 (4) |

A total of 46 participants attended the FGDs. Most (84%) were aged between 18 and 44 years, and there was a nearly even distribution of male and female. The group was relatively educated, with 78% having some secondary education or higher. Demographics of these participants are displayed in Table 3.

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 26 (56.5) |

| 35–44 | 12 (26.1) |

| 45–54 | 4 (8.7) |

| 55–64 | 2 (4.3) |

| 65+ | 1 (2.2) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (47.8) |

| Female | 24 (52.2) |

| Education | |

| No education | 7 (15.2) |

| Primary school | 3 (6.5) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 21 (45.7) |

| Post-secondary | 14 (30.4) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 16 (34.8) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 3 (6.5) |

| Newar | 10 (21.7) |

| Janajati | 7 (15.2) |

| Dalits and others | 6 (13) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 12 (26.1) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 21 (45.7) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 7 (15.2) |

| More than 60 000 | 2 (4.3) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 26 (56.5) |

| 35–44 | 12 (26.1) |

| 45–54 | 4 (8.7) |

| 55–64 | 2 (4.3) |

| 65+ | 1 (2.2) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (47.8) |

| Female | 24 (52.2) |

| Education | |

| No education | 7 (15.2) |

| Primary school | 3 (6.5) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 21 (45.7) |

| Post-secondary | 14 (30.4) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 16 (34.8) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 3 (6.5) |

| Newar | 10 (21.7) |

| Janajati | 7 (15.2) |

| Dalits and others | 6 (13) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 12 (26.1) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 21 (45.7) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 7 (15.2) |

| More than 60 000 | 2 (4.3) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 26 (56.5) |

| 35–44 | 12 (26.1) |

| 45–54 | 4 (8.7) |

| 55–64 | 2 (4.3) |

| 65+ | 1 (2.2) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (47.8) |

| Female | 24 (52.2) |

| Education | |

| No education | 7 (15.2) |

| Primary school | 3 (6.5) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 21 (45.7) |

| Post-secondary | 14 (30.4) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 16 (34.8) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 3 (6.5) |

| Newar | 10 (21.7) |

| Janajati | 7 (15.2) |

| Dalits and others | 6 (13) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 12 (26.1) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 21 (45.7) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 7 (15.2) |

| More than 60 000 | 2 (4.3) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Demographic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 26 (56.5) |

| 35–44 | 12 (26.1) |

| 45–54 | 4 (8.7) |

| 55–64 | 2 (4.3) |

| 65+ | 1 (2.2) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (47.8) |

| Female | 24 (52.2) |

| Education | |

| No education | 7 (15.2) |

| Primary school | 3 (6.5) |

| Secondary/Higher Secondary | 21 (45.7) |

| Post-secondary | 14 (30.4) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin | 16 (34.8) |

| Chhetri/Thakuri/Sanyasi | 3 (6.5) |

| Newar | 10 (21.7) |

| Janajati | 7 (15.2) |

| Dalits and others | 6 (13) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 10 000 | 12 (26.1) |

| 10 000–30 000 | 21 (45.7) |

| 30 000–60 000 | 7 (15.2) |

| More than 60 000 | 2 (4.3) |

| Not reported | 4 (8.7) |

We identified a wide variety of gaps, challenges and barriers that appear to prevent or complicate the successful management of diabetes in Nepal. We organized our themes into the five categories of the Ecological Model: Individual, Interpersonal, Organizational, Community and Public Policy.

Individual

General diabetes knowledge

To determine whether participants understood the causes of diabetes, we asked what could be done to prevent diabetes in their community. Many had a basic idea about some of the contributing factors, such as poor diet or lack of exercise, but around 30% reported having no idea. For example, one participant explained, ‘No one knows what causes blood sugar to increase or decrease. I don’t know about that. Nobody can say. There is nothing you can do to control this disease. There is no known reason for what causes it, whether it is because of spicy foods, or sweets …’ (female patient, suburban hospital). Focus group participants (individuals without diabetes), were generally able to brainstorm a list of the major causes of diabetes as well as some of the primary treatment methods. However, complications of diabetes were less frequently known.

Behaviour change: diet

Most interview participants with diabetes reported implementing a few key behaviour changes after getting diabetes. The most common changes included: reducing sugar consumption; reducing quantity of food; reducing white refined rice consumption or replacing it with a whole grain; avoiding starchy vegetables such as potatoes or yams; and reducing/avoiding oily or fried foods. Reducing consumption of tea with sugar was a major shift for many; ‘I used to drink five to six cups of tea with sugar per day, but now I only drink one cup with sugar’ (female patient, rural clinic).

The extent of implementing these changes varied by participant. Participants described experiencing many challenges related to diet change. The most common challenge reported was the feeling of not being able to eat the food that they want. We documented many statements such as, ‘The diabetes diet bothers me a lot…it makes me wish I could die sometimes. To have to live without those foods’ (female patient, private urban clinic).

All participants explained that changing what they have consumed twice a day since birth is not an easy task. ‘This is our food by birth’ one focus group participant explained. Moreover, most participants reported they were accustomed to eating large amounts of rice, and many complained that if they followed the recommended portions from the doctor, they would be left feeling hungry after every meal. ‘If your soul demands food and you don’t eat until you are satisfied, your soul won’t accept that’ (male patient, private urban clinic). Another explained, ‘having diabetes is equal to being hungry’ (male patient, rural clinic).

Behaviour change: physical activity

Exercise was found to be a fairly neglected activity, especially among city dwellers. The most common type of exercise reported among participants with diabetes was a simple morning walk. For many, this is the only type of intentional exercise done. Participants rarely mentioned doing more rigorous exercise or yoga. Those who regularly conduct farm work were among the only respondents reporting sufficient physical activity. A frequently mentioned form of physical activity reported was conducting household work such as laundry, cooking, carrying water, or cleaning the house. Many of the respondents viewed household work as an adequate amount of physical activity during a day.

The most commonly reported barriers to exercise were: lack of time; lack of energy; weakness or pain; age; disliking exercise; laziness; or perceiving themselves as too thin and not wanting to lose more weight. Multiple participants reported explanations such as, ‘For me, 30 min (of exercise per day) is enough. If I increase my exercise, I will feel dizzy or fall down. I don’t have anyone to walk with, otherwise I could go for longer’ (female patient, urban hospital). For those living in Kathmandu, pollution was also reported to be a barrier.

Medication adherence

Many mentioned feeling irritated about being on a lifelong medication. Some delayed initiating treatment, either because they thought the medication was unnecessary or they strongly disliked the idea of taking a daily, long-term medication. ‘I am irritated by having to take medicine my whole life. I wish I could just control with diet’ (female patient, urban hospital). Some participants only began taking medication once complications or symptoms developed. Many are especially hesitant or even refuse to begin insulin therapy, viewing it as a last stage drug. In fact, one doctor reported being extra cautious when recommending insulin to patients, as many will not return to the clinic if insulin is prescribed. Other insulin barriers included pain, fear, discomfort, difficulty in learning to use insulin, or having to rely on others to give the injections. ‘It is painful to take insulin … I curse myself,’ one participant described (female patient, rural clinic).

Disregard for healthy lifestyles

Nearly all focus group participants explained they do not take health into consideration when deciding what to eat. ‘There is no reason to change your foods unless you have a disease,’ one suburban focus group participant explained. When discussing nutrition, some interview respondents did not have a concept of food being related to long term health. Many others understood the general importance of a healthy diet, but lacked specific knowledge of what a healthy diet includes. Similar to the individual interview participants, FGD respondents often were unable to define what constituted ‘unhealthy food’, with many listing only spoiled food or spicy food as unhealthy. Foods such as soda or sweets were said to be unhealthy in only two of the five focus groups discussions.

Similar to diet, physical activity was seen as important by most participants with diabetes, but many did not understand its long-term benefits. Most only reported immediate benefits, such as feeling fresh, light, relaxed or active after exercise. Less than half mentioned the relationship between physical activity and diabetes control. Among focus group participants, exercise was mostly seen only as a method of weight loss, not necessarily related to long-term health; ‘If you’re already thin, you don’t need exercise’ (FGD participant, urban setting). In general, focus group participants were mostly unconcerned with how their current behaviours might impact their health.

Interpersonal

Social support

Overall, participants who had good family and social support seemed to do a better job with managing their lifestyle, behaviours, and drug adherence. Most participants said that their family is supportive of them; however, in a few cases, participants complained of an unsupportive environment. Some felt their community did not understand diabetes or know how to support them with their lifestyle changes. For example, one participant explained, ‘There should be an education program for family members because many are not supportive and it is hard for people with diabetes’ (male patient, suburban hospital). At the rural site, it was common for participants to report experiencing a stigma because of their disease. One participant described, ‘I am worried that other people will think I have done something wrong in my previous life to get this disease. Especially if I get a complication’ (male patient, rural clinic).

Many (especially older participants) reported having to rely on others for things such as picking up medicine, going to the hospital, taking medicine on time, and eating proper food. Having a family member who is willing to cook the right food was important for those participants who do not cook for themselves. One participant explained, ‘My wife doesn’t cook separate food for me, so I have to eat whatever she cooks. She is irritated if she has to prepare roti, dhido (a porridge traditionally made from buckwheat or millet), or boiled rice’ (male patient, urban hospital). Family members can also play an important role in encouraging physical activity. One older participant explained, ‘My family won't let me go on walks alone, so I only go if someone can take me’ (female patient, suburban hospital).

Organizational

The health providers interviewed offered fairly consistent observations on many of the challenges and needs/opportunities of the diabetes landscape in Nepal.

Provider shortage

‘The government should train more endocrinologists and distribute them all around the country, not just in Kathmandu’ (health provider, urban hospital). Providers complained of a shortage of endocrinologists or diabetes specialists in the country, with most residing in or around the Kathmandu Valley or other large cities at referral hospitals or private diabetes centres. Even in large hospitals, the burden of a high patient load lies mostly on internal medicine residents and medical officers, with few, if any, specialists overseeing them.

High patient load leads to insufficient care

Outpatient departments, particularly those in large public or community hospitals, have a high patient load. Providers reported seeing up to 100 patients per endocrine OPD session, which usually lasts a half day. Providers from larger facilities (especially public) complained about having very little time to spend with each patient. On average, doctors at large hospitals reported spending around 5 min with a follow-up case and around 10 min with a newly diagnosed case. This was a source of frustration for some of the health providers we interviewed. One doctor stated: ‘When we are in such a hurry, the patients may sometimes misunderstand how to take the medicine. When they come back for their next visit, the doctor notices that they are taking the medicine improperly’ (medical resident, urban hospital). Doctors also admitted they typically only have time to review recent laboratory results and discuss any medication changes necessary. Little attention, if any, is given to lifestyle management. A majority of interview participants with diabetes reported they had never received comprehensive counselling on diabetes, which should include basic pathophysiology, prevention of complications, treatment, and lifestyle and behaviour change. One patient explained, ‘If I could get better advice about my diet and lifestyle it would help me better control my diabetes’ (female patient, urban hospital). Another said, ‘I know I need many improvements to my lifestyle, but I don’t know what else I can do’ (female patient, urban hospital).

Long wait times

Patients often experience long wait times during OPD visits. In large hospitals, where the majority of patients reportedly go for treatment, wait times for a regular follow-up visit range from 3 to 4 h to 2 days. At two of the large hospital sites we visited, patients reported that they are required to visit the hospital twice: one day for labs, and another day to retrieve the lab report and meet with a doctor. One woman described, ‘It is time consuming to go for check-ups. It can waste 2 days of the week. There are long queues up to 6 or 7 h, (female patient, urban hospital). Small private clinics and the rural health centre were generally faster, with shorter wait times both for completing the laboratory tests and consultations with the doctor.

Underutilized nurse education programs

At two sites, a nurse educator program was available where patients could receive comprehensive individual or group education outside of their OPD visit. Although these services seemed to be of good quality, they were often underutilized. ‘Some patients don’t even know that we have a diabetes education room,’ one nurse educator explained at an urban hospital. In one site, a doctor estimated that only around 10% of follow-up patients have attended the group education session offered. A dietician was available for diet education at two sites; however, this service was also underutilized, as both doctors and the dietician admitted that patients were rarely referred. All nurse educators and dieticians interviewed agreed on the need to scale up these educational services.

Community

Dietary transition/urbanization

Nearly all health providers interviewed mentioned that the lifestyle and diet behaviours, particularly of urban residents, have been rapidly changing. A dietician noted, ‘Lifestyles are becoming more luxurious and the standard of living has improved’ (Dietician, urban hospital). Health providers seemed concerned that people are no longer eating healthy food, but instead relying on unhealthy snacks and fried food that are now more available than health foods. As one health provider explained, ‘People are outside of the home more nowadays and eating at restaurants and fast food’ (Medical Officer, suburban hospital).

Participants with diabetes explained that finding the healthier options in the markets can be difficult. ‘In the past, I used to cultivate my own land, and I used a healthy, unrefined flour for bread items. Now, no one is working in the field, so I buy the normal refined flours’ (male patient, suburban hospital).

Replacing or reducing consumption of white, refined rice proved to be a major challenge for many respondents. Rice replacement options, such as whole grains or dhido, are sometimes unavailable in the market or hard to find, can be more expensive than processed white rice, and are often harder or take longer to cook.

Not only has diet transitioned, but mobility and transport options as well. Health providers also explained that sedentary lifestyles are now more common, especially due to recent urbanization patterns; ‘Nowadays, less people are working in the fields and instead they are working in offices … before people walked far everywhere, but now they take a car, bus or motorcycle’ (health provider, urban hospital).

Lack of community screening

Another challenge in Nepal is the lack of time and resources for community screening programmes. One nurse explained, ‘We need more staff to conduct screening events and community education programs’ (health provider, urban hospital). We heard very few reports of screening activities beyond incidental case finding at most sites. Only two patients interviewed mentioned they had been diagnosed during a routine health check-up. Nearly all were diagnosed after going to the hospital for treatment of a diabetes related symptom or complication or while being treated for an unrelated condition.

Public policy

Adapting guidelines to the Nepali context

Some health providers interviewed claimed that the guidelines used by Nepali doctors and nurses were developed outside the country and context of Nepal. As one urban consulting doctor explained, Nepal ‘needs guidelines for diabetes depending on Nepali food habits … and how to use metformin in the Nepali context.’ In addition, the government ‘has not been implementing a concrete plan to address diabetes,’ one dietician explained (Dietician, urban hospital).

Poor access for rural patients

Unequal provision of services geographically was a frequent concern throughout the interviews. Patients in rural areas face challenges accessing services for diabetes. Rural diabetes patients often must travel long distances to reach a hospital where comprehensive diabetes services and specialists are available. Some patients in rural areas explained that they do not trust the doctor or health assistants in the rural health centres for diabetes care. For example, one participant claimed, ‘That doctor does not know about nutrition. Some people only trust specialists, not generalists’ (male patient, rural clinic). Many rural health centres lack the availability of sophisticated laboratory tests for diabetes, especially HbA1c. One medical officer explained, ‘(Nepal) needs more sophisticated labs at the VDC (village development committee) level so that testing can be done in villages. We need a lab facility in every VDC that can test glucose’ (medical officer, suburban hospital). Drug shortages are also common in the rural areas and many rural clinics do not stock insulin, usually because of a lack of stable power for proper cold storage. The medical officer continued, explaining that rural dwellers often ‘must come to towns to get medicine.’

Financial barriers to care

Respondents frequently reported on the financial burden of having diabetes. These include high out-of-pocket health-care payments for outpatient visits or medications/supplies, and catastrophic medical expenses. In addition, many participants reported having to reduce their work and stop farming or other hard physical labour. This results in a long-term loss in financial earnings with less money for basic necessities or financing their children’s education. For example, one participant told us, ‘I even have trouble paying for food and water, so how can I pay for diabetes treatment?’ (male patient, suburban hospital). Another mentioned, ‘I have to decrease other expenses in the home to afford treatment’ (male patient, urban hospital). Around half of the participants must take or borrow money from a family member for treatment, thus financially affecting the whole extended family. Some participants mentioned experiencing family tension about the financial consequences of their disease. One reported, ‘Some (family members) treat me badly because of all the money I have to spend. I feel bad about having to use my daughter’s money on my treatment’ (female patient, urban private clinic). Another explained, ‘Sometimes my mother-in-law doesn’t support me spending so much of her son’s money on medicine. Sometimes there is quarrelling’ (female patient, rural clinic).

Our findings on diabetes-related cost expenditure show a wide range in what people spend on their treatment. A few reported only spending around Rs. 170 (US$1.59) per month for medicine only and Rs. 200 (US$1.87) every 3 months for a check-up. Most others, however, especially those on insulin, reported much higher expenses. The highest monthly expenditure reported was around Rs. 25 000 (US$234.28), and the average monthly expenditure was between Rs. 2000 and 7000/month (between US$18.74 and 65.60).

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the most significant gaps and barriers to providing and receiving comprehensive diabetes services specific to a Nepali setting. Our results confirm many of the findings from the literature review published by Gyawali et al. (2016) which sought to determine the prevalence, complications, cost, and treatment of Type 2 Diabetes, and the challenges that need to be addressed in order to contain the epidemic and its negative economic consequences. We identified a variety of barriers to diabetes management from various levels of society. On an individual level, patients’ knowledge and self-management behaviours can be a barrier. For example, limited education on diabetes and its management can lead to inadequate self-care strategies, particularly in terms of diet and physical activity. Interpersonal factors, such as lack of social support, can also be a barrier, especially for those who rely on others for regular self-management activities. Our findings of the most common self-care strategies and barriers were largely in agreement with Bhandari and Kim’s (2016) research on self-care behaviours of Nepalese adults with Type 2 Diabetes, especially in terms of diet control and exercise.

While some patients face self-management challenges, many of the barriers to diabetes care occur on an organizational level, which are related to the scarcity of financial and human resources for health. Health centres and hospitals struggle to provide comprehensive, ongoing care to a growing number of diabetes patients. The ratio of patients to diabetes specialists and support staff remains high, while educational resources for patients and the community remain low (MoHP 2013). These organizational challenges are exacerbated by various community or cultural barriers, such as the recent shift to diets high in carbohydrates and sugar.

From a public policy level, major gaps remain in the provision of services for diabetes. Financial barriers continue to prevent some patients from receiving regular treatment, including checkups and medication. This was especially true for patients requiring insulin. A study conducted by the WHO found that purchasing 1 month of insulin would cost the lowest-paid government worker in Nepal the equivalent of 7.3 days of work (Mendis et al. 2007). Most patients in our study spend somewhere between Rs. 2000 and 7000/month (between US$18.74 and 65.60), which is in agreement with a previous study in Nepal reporting the average cost incurred in the treatment and care of diabetes per month to be US$40.40 (Shrestha et al. 2013).

Inadequate drug supply continues to be a major concern. According to the Nepal Government’s Free Essential Healthcare Services Program, some diabetes medications should be given free of cost at certain hospitals. However, in a review of the Nepal National Free Health Care Program, only 25% of district hospital users and 40% of primary health care centre users reported that the essential drugs were always available (Prasai 2013).

The 2015 Nepal Health Facility Survey reported that only 21% of facilities in the country offer services for diabetes. The division between public and private facilities was quite stark; while nearly all private facilities offer diabetes services, only 15% of public facilities do. Among facilities offering diabetes services, only 4% had guidelines for the diagnosis and management of diabetes, and only 2% had a staff member recently trained in provision of such services (Ministry of Health, Nepal et al. 2017).

The Nepali government has recognized the growing significance of chronic diseases, including diabetes, and has taken some initial steps to address the concern, such as the 2013 Ministry of Health’s Multi-Sectoral Action Plan for Prevention and Control of NCDs in Nepal and the recent call for a rapid scale-up of the Package for Essential Non-Communicable Diseases (PEN). However, executing the stated recommendations is not an easy task and few financial resources are committed; in 2009 only 0.73% of the government’s budget was spent on all NCDs (Mishra et al. 2015).

Currently, community- and mid-level health facilities are often ill equipped to provide screening and treatment services for diabetes, thus forcing patients to attend less accessible, higher-level health facilities (Bhuvan et al. 2015). The Ministry of Health must strengthen the health system at community- and mid-levels by providing training to healthcare workers on diabetes management, developing chronic disease registries, and stocking the facilities with adequate drug supply and testing equipment.

Because of the complexity of the challenges to managing diabetes, a multilevel, coordinated approach is necessary. As the government of Nepal takes steps towards developing concrete actions resource allocation to address diabetes, it will be important to consider the various levels of society described here. Given the challenges, it is doubtful that the public health system alone will be able to meet all patient and community needs in the near future. Therefore, complementary solutions to the current traditional facility-based model could be a useful development. Nepal needs an innovative solution for providing chronic disease treatment that is both affordable and easily accessible to all.

One method gaining attention in a growing number of low-resource settings is the use of community-based programs to supplement hospital-based services for chronic diseases such as diabetes (Nissinen et al. 2001; van de Vijver et al. 2012; Dhitali and Karkii 2013; Van Olmen et al. 2015; Afable and Karingula 2016). Community-based programmes can advance health promotion, improve diabetes awareness and support diabetes patients with their on-going self-management. Existing examples of community-based programmes vary in their aims as well as methodology. Some focus on nurse led or village health worker led community programmes, others use peer-educator led models, and a growing number of interventions integrate technology to promote education or improve glycaemic control.

Though further research is still required, many of these interventions are proving to be effective at both prevention and management of diabetes and other chronic conditions, with some proving to be more convenient than hospital based services with lower direct costs (Norris et al. 2006; Afable and Karingula 2016; van Olmen et al. 2016). Moreover, there is evidence that moving management of NCDs to allied health professionals or community health workers can even improve patient outcomes (Joshi et al. 2014). Nepal has a strong history of successfully implementing community based health programs. The network of Female Community Health Volunteers, Village Health Workers and the Maternal and Child Health Worker networks are still considered unique models of health workforce. Although challenging, we believe that community-based programmes would be realistic in the context of Nepal. Strengthening existing networks of community health workers and if needed creating new cadres of health workers specifically focused around the promotive aspects of diabetes would be a potential approach. Engaging schools, mothers’ groups, youth groups and other local stakeholders might be another way to create community-based programmes for diabetes.

In the past few years, the Government of Nepal has put significant emphasis on NCDs including diabetes. The government is currently piloting PEN in 6 districts and is in the process of rolling out to all 75 districts within next couple of years. This is a major development. However, there are still significant challenges in terms of training human resources and strengthening infrastructure. It is crucial that the Government of Nepal takes immediate action to implement the strategies developed in the PEN, Multi-Sectoral Action Plan for Prevention and Control of NCDs, as well as ensure that diabetes medications allocated in the Free Essential Healthcare Services Program are widely distributed. Solutions that go beyond health facilities and reach the community level (both urban and rural) will be especially important in order to affect individual behaviour change.

Strengths and limitations

Our sample was not large enough to conclusively determine distinctions between rural and urban populations, and because this study was only conducted in five districts within Nepal, the results are not necessarily generalizable to those from all over Nepal or those from all socioeconomic or ethnic backgrounds. However, we believe our results characterize the barriers experienced by patients from a broad range of different geographic regions and socioeconomic backgrounds. The language barrier was an additional limitation, as the lead researcher was not fluent in Nepali language. Thus, interview guides and participant responses required translation, which potentially could have resulted in some mistranslation or differing interpretations, culturally and linguistically. Strengths of the study include the multi-level approach taken to include an assessment of both the health facility and provider perspectives as well as the patient and community perspectives.

Conclusion

People with diabetes in Nepal face a variety of substantial barriers to successfully managing their disease. Many of these barriers will be difficult to overcome without additional financial and human resources within the health sector or implementing other novel interventions. Due to the current constraints of the health system in Nepal, community-based programmes could be utilized to supplement facility-based health services and improve diabetes awareness and management. Such programs should be developed for a Nepalese context and evaluated for their effectiveness.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Nepal National Health Research Council (269/2015), the Institutional Review Committees at Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences, and B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (IRC/701/015). Informed, written consent was received from each participant before each interview or FGD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating study sites and site collaborators and to Dr. Dina Shrestha for her support. They also extend appreciation to Ms. Shanta Asthanee who conducted all the interviews and FGDs.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the US Fulbright Student Research Fellowship program.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.