-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Philipp Rössner, Peasants, Wars and Evil Coins: Towards a ‘Monetary Turn’ in Explaining the ‘Revolution of 1525’, German History, 2025;, ghaf016, https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghaf016

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Is there anything left to say about the Peasants’ War of 1524/25? This article takes up that challenge by demonstrating how the ‘monetary turn’ evident in the later decades of the fifteenth century and early decades of the sixteenth century explains an often-overlooked item amongst peasants’ complaints: the nature of their financial exploitation by feudal lords and their administrators. Such monetary concerns had featured prominently on lists of peasant grievances since the 1460s and fed into Empire-wide discourses on good governance and imperial reform. At their core, this article suggests, was the debasement and lack of the small change coins that peasants used in daily exchanges and to pay taxes and other levies. This article explores these very real monetary grievances and the challenges of righting them, generating a new thread to weave into explanations of the nature and timing of the German peasant revolt of 1524/25.

In 1514 the Poor Conrad (Arme Konrad) movement saw a series of peasant insurrections in the German south-west. The peasants of Elchesheim and Steinmauern in the Margraviate of Baden advanced numerous bitter complaints, including a specific grievance about the way they paid tax:

Whenever the poor common man is asked at the common time of the year to render their Bethen [a local tax], the administrators—even in those cases where the sums due fall below the value of one Gulden—insist on payment in gold.1 Nay, your officials refuse to accept the common land currency [i.e. medium and small change Pfennigs and Groschens] issued by our gracious lord the margrave himself, meaning we are forced to take considerable trouble and toils going about and around trying to get good money, which causes us a lot of mishaps and financial loss. But since, our dear lord, we poor people do not usually come across much gold coin; and our dear lord’s Landesordnung [territorial regulation] forbids us to engage in coin trading and the purchasing of gold at any more than the legal rates, we humbly petition your princely lordship that you accept tax and other such payments in your lordship’s own common land currency or currency of similar value and type.2

This passage portrays the essence of the ‘monetary problem’ of the medieval peasant revolts, including the Great German Peasants’ War of 1524/25. Monetary complaints are known to have been made during all revolts in the German-speaking lands during the medieval period (and continued beyond 1525), including many urban uprisings. In the instance cited above, the peasants complained that when they did not have gold or any other ‘good’ coins to hand and even in instances when the sum due was less than one Gulden, the temporal authorities (lords, princes, dukes, counts, bishops etc.) and their administrators overcharged them by requiring that they pay more than the official exchange rate for small coins against the full-bodied Gulden. According to the peasants, this created additional economic hardship on top of their already considerable grievances. Peasant complaints were voiced regularly, often against the background of the late medieval crisis of feudalism, which had seen landowners and lords across the German-speaking lands increase services, dues and levies in the face of declining real revenue. These grievances constituted the matrix of late medieval peasant discontent, culminating in the German Peasants’ War of 1524/25.3

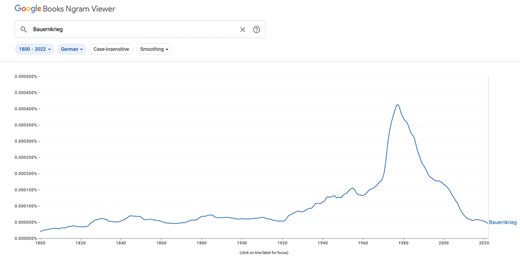

As a topic of historical research, the Peasants’ War of 1524/25—or ‘Revolution of 1525’ in the words and interpretation of one of its leading historians, the late Peter Blickle—now seems closed. Historians’ attention declined after 1975, when its 450th anniversary had seen a flurry of workshops, conferences and publications, both in West Germany and in the GDR (see Fig. 1).4 Structuralist-materialist interpretations focusing on the late medieval ‘crisis of feudalism’ waned with the removal of the Iron Curtain. Western counter-models such as the Bielefeld School’s historical materialism (historische Sozialwissenschaft) likewise withered. Some historians now consciously abstain from macro models when explaining the Peasants’ War.5 In a recent article, Gerd Schwerhoff discusses ‘cultural turns’ of the last few decades which ‘involved, on the one hand, source criticism and critical reading of sources and, on the other, approaches to actor-centred histories of events and communication which might convey a true impression of the dynamic unfolding of events in the Peasants’ War’.6 Schwerhoff concludes that although modern accounts of the peasants and the several local and regional revolts of 1524 and 1525 have employed the all-encompassing term ‘German Peasants’ War’, the events were too complex to be explained by simplified structural models.

References to Bauernkrieg (peasants’ war) in the German-language printed record, 1500–2019.

Whilst the field seems to have moved away from materialist explanations, it should be stressed that cultural and economic—or ‘materialist’ (not material)—narratives are not mutually exclusive. Sections Four and Five of this article will point out ways of combining a monetary-history (and thus potentially ‘structuralist’-type) approach based on coins with more cultural-historical traditions of scholarship. Writing the history of a political economy of money without considering money’s materiality and culture—that is, people’s strategies, modes and habits in using money—would be myopic, but so too would be the reverse, for people’s culture, material as well as immaterial, always has a political-economic basis (one need not even be a Marxist to realize this). All peasant risings of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were manifestly co-determined by money and currency, especially shortages of some coins, and by the way that payments and obligations were settled. Thus, this article proposes a monetary turn as a new lens on the Peasants’ War of 1524/25.

Monetary factors have been overlooked by modern historians. Even the recent landmark survey the Routledge History Handbook of Medieval Revolt (2017) features the word ‘monetary’ only once.7 Yet earlier scholarship had picked up on money’s significance. In his interpretation of the Peasants’ War, Friedrich Engels noted in passing that on the eve of the early modern period coin matters were one of the prime causes of social unrest:

When nothing else availed, when there was nothing to pawn and no free imperial city was willing to grant credit any longer, one resorted to coin manipulations of the basest kind, one coined depreciated money, one set a higher or lower rate of legal tender most convenient for the prince.8

According to Engels (and Marxist/historical-materialist interpretations in his wake), currency debasement was part and parcel of the larger economic burdens imposed upon the common man during the age of early bourgeois capitalism, a result of the ruthless drive by the feudal nobility to optimize their income and the incessant hunger for money of the emerging princely fiscal-military states. Rulers and nobility alike stood firm against peasant calls for societal reform, with urban burghers part of the oppressed in Marx and Engels’s model.

Money played a significant role in this narrative. In the commercially and economically developed areas in central and south-west Germany, where the Peasants’ War was particularly widespread, coins were objects of quotidian use, as also elsewhere. Almost every adult of the time used coins regularly. In the village economies, coin use often clustered around harvest time, when rent and other payments were due; there were therefore also slack times when money played less of a role. Coin use also varied across economic regions and specific groups of economic actors. In specialized agrarian regions integrated into wider markets, money was used regularly and in large quantities. Such was also the case for individuals (‘elites’) such as cattle traders in the northern marches and Schleswig, taverners, innkeepers and other peasant entrepreneurs. Elites often provided leadership in revolts, their economic interests shining through in formalized lists of peasant complaints (Gravamina, Beschwerdeschriften).9 In cities and towns and their hinterlands, especially areas with high levels of manufacturing, the amount of money in circulation was greater and its circulation faster.10 Many local and regional complaints, including articles two, eight, nine and eleven of the Twelve Articles of the Upper Swabian Peasantry, composed in 1525 and adopted as a somewhat ‘national’ programme for reform during the Peasants’ War, specifically referred to ‘payments’.11 And specific types of money featured in the hundreds of known local and regional complaints that formed the basis of the formulaic and somewhat codified Twelve Articles.

But apart from occasional writings and cursory remarks by Franz Irsigler12 and Matthias Puhle13 on urban uprisings, Wilhelm Zimmermann’s old history14 and Ekkehard Westermann’s article on miners’ revolts,15 neither of which focuses on the Peasants’ War specifically, and studies by Philipp Rössner,16 Oliver Volckart17 and Jürgen Bücking,18 the monetary issue (Münzfrage) has hitherto evaded historians’ radar. As an appendix to his groundbreaking book The Revolution of 1525, Peter Blickle produced a systematic template of peasant grievances by topic, based on a representative sample of Upper Swabian complaints. This mapping contains no separate columns for currency; the monetary issue would have been covered under the catch-all heading ‘remainder/other’.19 In regional grievances and complaints, however, coin issues cropped up regularly, often as the first point. They also had a firm place in Empire-wide reform discourses such as Friedrich Weigand’s Reichsreform or the Oberrheinische Revolutionär, two programmatic pamphlets calling for imperial reform that seemed to have found a large audience in the German-speaking lands during the first two decades of the sixteenth century.

In fact, if one feature unites most uprisings of the late medieval era, including the German Peasants’ War, fits within both Western (e.g. Blickle’s ‘Revolution of 1525’) and East German models (e.g. frühbürgerliche Revolution) present and past, and affected broader social groups and actors across a vast number of politically non-homogeneous areas within the Empire, then that feature is money. Monetary debates affected the rise of the premodern state.20 Deliberations focused on just and unjust trade profits and the common good, economic rents enjoyed by some at the expense of the peasants (who formed the majority of the populace), and, put bluntly, who got to eat how big of a slice of the cake that we now term GDP. These were the guiding questions of older ‘materialist’ interpretations.21 The first two-and-a-half decades of the sixteenth century were marked by crisis, deflation and depression in the regional market economies of southern and central Germany.22 Coupled with skyrocketing trade profits and monopoly rents enjoyed by well-known overseas trading firms, silver outflows facilitated the rise of commercial capitalism and led to a widening gap between merchants’ profits (or capitalists’ incomes) and peasant revenue. They also caused recurring monetary shortages, especially in economically advanced areas of Saxony, Thuringia, Swabia and Bavaria. Monetary squeezes featured as main topics at the Imperial Diets of Augsburg and Nuremberg during the 1520s, particularly in juxtaposition to the ‘monopoly’ debates.23 They also merged with broader issues of religious and imperial reform.24

Section One of this article discusses the monetary foundations of medieval popular revolts, which occasions Section Two’s broader consideration of imperial reform when monetary matters were moved to the top of the agenda around 1500. Section Three discusses the Peasants’ War as a ‘monetary’ event. Discourses on money traced through peasant grievances and complaints were rooted in day-to-day practices of the peasant economy, but at the same time they impinged on wider questions of capitalism, monopolies and merchants’ profits. Evidently there was a larger political economy of money out there, the basic contours of which are sketched in Section Four, suggesting a framework for future studies addressing the point where culture, capitalism and the politics of early modern money meet. Finally, Section Five somewhat reframes the old Tawney thesis about reformation, religion and the rise of capitalism.

I. Precedents and Predecessors

During the so-called Plappartkrieg, in August/September 1458, some 4,000 confederates marched against the city of Constance. The event appears to have been a result of local conflicts over coins.25 Citizens of Constance had allegedly refused to accept Swiss Plappart money as payment, derogatorily referring to it as ‘cow coins’ (Kuhplapparte).26 In this instance, as in so many late medieval grievances about money, coins were identified as ‘good’ or ‘bad’. But what did such terms mean?

The Salzburg peasant war of 1462 gives us one answer.27 It occurred in the wake of massive inflation caused by the excessive minting of Schinderlinge, heavily debased small Pfennig-type coins consisting almost entirely of copper. The prevailing monetary paradigm deemed them practically useless, as contemporary monetary theory assumed all currency had to contain at least some silver or gold, to embody purchasing power. Such böse (‘bad’ or ‘evil’) coins, as they were labelled in contemporary documents, had been minted in the Austrian lands since the mid-1450s.28 They spread across the Alps wreaking economic havoc. Initially, on 20 May 1459, the official ratio (determining how much silver these coins would legally contain; their intrinsic ‘goodness’) was set such that 4,300 Pfennigs were to be struck from the Vienna silver mark, but by spring 1460 this number had increased more than five-fold, to 23,040 Pfennigs, creating a grotesquely debased and literally worthless currency. Weak from the beginning, these coins were now doomed. In normal times the Hungarian ducat (the leading currency in the region) exchanged at one ducat for 220 to 240 pennies. But during the Schinderling age this ratio exploded from one ducat for 300 Pfennigs (early in 1459) to one ducat for 3,686 Pfennigs (in spring 1460), triggering the first known European hyperinflation.29 Schinderlings flowed rapidly into Vienna, Styria, Carniola and southern Germany. Complaints centred on the agio, or premium, on payments made in bad pennies and other small change nominals. This agio was applied when the Schinderlings, which circulated alongside other regional currencies, competed against older coin types that contained more silver: people refused to accept Schinderlings at face value, preferring older (heavier) coins instead.30 The regional diet (Landtag) held at Gollarsdorf in 1460 summarized the effects: ‘No war, no plunder or armed robbery, no arson could have possibly ruined and impoverished the country as the Schinderling [lit. ‘Oppressor’s Penny’] has.’31

While the Schinderling hyperinflation was exceptional, complaints about bad coin were not. Nor were they limited to Austria or the Alps. As we will see in Section Two, since the 1440s monetary improvement had become a centrepiece of Empire-wide discourses on good governance and imperial reform. Local revolts in Carinthia and Styria in 1462 and 1470 again brought to the fore the matter of agio (Aufwechsel or Aufwexl, in the language of the time) and other currency issues. Similar complaints continued unabated up to the Peasants’ War and even beyond.32 In 1504, the farmers of Thurgau, in the Swiss Confederacy, complained about the Rolle(n)batzen, a notoriously ‘bad’ or ‘evil’ type of small change coin initially of the Groschen type (a medium-sized coin; the word Rollen may have stemmed from a term for excrement, and Rollenbatzen thus literally translates as ‘shit coin’) whose value was heavily contested; it would eventually be prohibited by the Imperial Currency Edict of 1559. Contemporaries claimed that ‘good’ (i.e. full-bodied, heavy) money had become progressively more difficult to obtain. When peasants sold their wine and other products, they were paid in coins that would be heavily discounted when used in subsequent transactions, such as purchases of corn. The farmers pleaded to the authorities, including nearby cities and local counts, abbeys and monasteries that had the right to mint money, such as St Gallen and Constance, that they produce currencies that would have equal value in peasant purchases and sales.33

It may seem bewildering today that many currencies did not fulfil what is considered the basic purpose of money: to serve as a reliable means of exchange, storing value and denoting prices and equally accepted by everybody. Their instability runs against the modern monetary imagination. It also contradicts textbook narratives that casually assume that a florin was a florin and a thaler a thaler, worth so many Groschens, Batzens, Schillings and so forth. It has been supposed that we can convert historical monetary values in written sources by using official exchange rates reconstructed from contemporary monetary legislation, without any consideration given to what types of coins were normally used on what occasion and in which marketplace. The evidence presented here suggests that the common folk were sufficiently financially literate to be able to recognize a sizable number and range of shoddy coins. Thus, while historians today have assumed that generally money circulated by tale (face value) not weight, so according to the official relations stipulated in the normative legislation contained in monetary edicts and ordinances, this assumption has remained unproven.34 And, in fact, many sources used in this article suggest the opposite: often coins were given and taken not at face value but in light of what they were considered to be intrinsically worth by weight.

Back to our Thurgau peasants. Rollebatzen coins were widely considered a particular nuisance. As the complaint from 1504 suggests, they were valued between eleven and twelve regional Pfennigs, depending on whether the farmer was paying or was paid in them. Either way, this market valuation fell far short of their official rate of sixteen Pfennigs to the Batzen. Eventually, Franconian and Swabian mint masters—government officials tasked with declaring official coin values and bringing order to the monetary landscape—capitulated. It was impossible, or so they claimed, to put a reliable tariff on the Rollebatzen, for too many were in circulation and they were of various provenances and dubious intrinsic content.35 Similar scenarios ensued elsewhere. In 1511 the peasants of Kammer and Kogl, in Austria, complained that while by statute they had to pay taxes in good coin, they received the lion’s share of their proceedings in small change pennies, or even smaller coins, such as Hellers (a half-Pfennig coin). These contained little to no silver, but when used in tax payments in lieu of gold, peasants had to pay a premium over their nominal value—we heard similar complaints from the Elchesheim and Steinmauern peasants at the start of this article. Authorities refused to accept them at face value.36

The prevailing monetary standard was based on an understanding that the purchasing power of a coin was determined by the value of the silver (or gold, in the case of high value Florins or Guldens) it contained, with the value of that silver (or gold) determined by what it could buy on the market if uncoined, so as an ingot. The purchasing power of the coin was based on this value of the silver (or gold) minus brassage (the costs of minting) and seigniorage (the ruler’s remuneration for the regalian right of coinage, or Münzregal). It was also understood that small (Pfennigs, Hellers, Kreuzers) and medium (Groschens, Batzens etc.) change coins contained proportionally less precious metal than high value Thalers (silver) and Florins (gold) coins of the Gulden type and its equivalents (as gold became progressively more scarce after 1500, ‘gold’ coins such as Guldens were increasingly minted in silver and were accordingly larger (gold was usually priced at about twelve times its weight in silver). Otherwise, they would have been minted at a loss, which would have resulted in the small change supply drying up altogether. But the common man needed small change coins for their daily economy. Even though exchange rates between small, medium and high value coins were usually fixed by law, whenever small change coins were old, unknown, or foreign, or for another reason their silver content could not be asserted, administrators charged with collecting taxes and rents refused to accept them at face value (i.e. the legal rate) or asked for a risk premium if peasants were unable to pay in high-value cash.

During the Solothurn uprising of 1513/14, the first article of the grievances presented by the Büren peasants put it plainly: ‘We suffer from the currency’ (Der munz halb oder pfunden sind wir beschwert).37 In the same year the territorial diet of the Duchy of Württemberg held at Stuttgart received petitions about the very Rollebatzen that the Thurgau peasants had lamented earlier, because they were pricing good money out of the market (which aligns with Gresham’s Law, which states that bad money drives out good money). The coins were identified as a risk to the country, depressing business and trade. Merchants would flee countries where bad coin was in circulation, the petitioners claimed (dann sonst die gewerb us disem land gepracht werden).38 On 29 June 1514, Duke Ulrich acknowledged that bad money reduced the common good.39

Similar warnings were heard in the same year from peasants from Rot(h)enfels, Gaggenau and Bischweier and, as we heard at the beginning of this article, from peasants from Elchesheim and Steinmauern.40 In 1523 the peasants of Further Austria petitioned to have bad coins prohibited, particularly Batzens; again this concern was the first point on their list.41 With neither the margraves of Baden nor any other monetary authority of the time able to control the amount and composition of coins in circulation (many of which were foreign), the ratio of better coins in circulation to bad coins determined the current (or spot) exchange rate between the two, fluctuating around target exchange rates set by monetary edicts.42 Complaints had been heard since the 1470s from raftsmen (Flößer) on the Upper Rhine who were paid for their services at the official coin exchange rate of twenty-four white pennies (called Albus in that particular region, using the Latin equivalent term for ‘white’) to the Florin as stipulated in the official ordinances of the margraves of Baden and the dukes of Württemberg. But when peasants paid taxes to the territorial authorities, their reeves and other administrators frequently refused to accept Albi—a type of groat or Groschen, a medium-sized nominal—at the official rate. They discounted the Albi by up to three white pennies, which drove up the spot exchange rate of the full-bodied Florin or Gulden to twenty-seven Albi, so to three Albi more than its ‘legal’ rate.43

Thus, coins gave rise to perennial bargaining, heckling, conflict and complaints.44 Incidents like those described above were not limited to the Swiss Confederation, Swabia and south-west Germany or Tyrol. By the early 1520s they were appearing on the imperial agenda.

II. The Political Economy of Money—From Canon Law to Imperial Diets

In 1522, the Imperial Cities claimed at the Imperial Diet held at Nuremberg that ‘both the German nation, as well as the common man are burdened with the sheer variety and ubiquity of bad silver and small change coin’.45 Good, reliable money was exported out of the German-speaking lands, which benefited mint masters, merchants and other financiers. Such complaints echoed the Reformatio Sigismundi (c.1439), a collection of programmatic writings discussing various matters of political economy, including how currency debasement ‘betrayed’ the common man.46 Very similar terminology was deployed in the anonymous Oberrheinische Revolutionär, produced around 1500, which noted how the common man was disadvantaged by the coin (muntz, do wirt der gemein man schandtlich mit vberfůrt). A marginal note states, ‘a good currency is evidence of the highest praise’ (laus maxima bona moneta), meaning, in modern terms, ‘a good currency is the best evidence that the country is flourishing’.47 ‘People lend in bad money and demand repayment in good coin in return’ (Man lyhet eym yetz müntz vmb goltt), Sebastian Brant mused in The Ship of Fools in 1494. The Imperial Diet of 1524 noted the problematic Batzen currencies, which caused many problems for the common man (merkliche, heimliche beschwerd des gemeinen mannes im h. Reich).48 Based on an anonymous pamphlet from 1523 entitled ‘The Needs of the German Nation’ (Teütscher Nation Notturfft), Friedrich Weigand’s draft imperial constitution of 1525 proposed a common imperial currency to solve the matter. The Empire should not have more than twenty or twenty-one mints (places where coins were struck), so that the common man remained unscathed (der gemain Man in der Munz unbetrogen bleib).49 Michael Gaismair’s Tyrolean constitution of 1526 struck the same note, proposing a ‘good sound currency as we used to have under Emperor Sigismund’.50 The Imperial Currency Ordinance of Esslingen, issued in 1524, marked a first attempt to make Utopia a reality, although a common currency had to wait for decades.51 As Volckart notes, ‘Negotiations about a common currency took place […] at practically all imperial diets between the 1520s and the 1550s.’52 Monetary matters remained one of the pressing socio-political discourses beyond the Reformation.

Coin manipulations of the type discussed so far came close to what Canon Law deemed usury. Scholastics like Gabriel Biel (1410–1495), who had written a widely read treatise on money, were well aware of the dangers of coin usury, that is, unfair gains made in the marketplace by those who knew how to handle different types of coin for profit.53 Roman Law jurists, including Christoph Cuppener/Kuppener and Cyriacus Spangenberg, defined certain coin manipulations as usurious, for example, the provision of loans in Muntz (regional small change) but requiring payment ‘in gold’ (at an agio).54 In his Large Catechism of 1529, Luther declared, ‘What a plague the world is now suffering from the bad and evil coin, which daily harms common trade, commerce and labour!’55 His ‘Sermon on Usury’ of 1520, which appeared in his longer treatise ‘On Commerce and Usury’ (Von Kauffshandlung vnd Wucher, 1524) insisted that ‘no one would normally borrow rye for wheat, or bad coin for good coin’. Such exchanges would involve returning more than initially given, another definition of usury.56 In a more personal context, in a letter dated 1540, Luther wrote to his wife, Katharina, ‘We have here not a single penny and hardly any small change, possibly as little as you have at Wittenberg’, and advised, ‘People should refrain from using Märkische groats and the Schottenhellers [lit. Scots Hellers, or half-pennies], as these considerably harm these lands and their people, being worth less than five hellers each.’57 The numismatic literature is unclear on what exactly Schottenhellers were, but clearly they represented bad money. By the sixteenth century Schotten, by no means necessarily or exclusively referring to Scots (or Irish) people, had attained a proverbially pejorative connotation in the German-speaking lands, coming close to the modern notion of ‘shoddy’.58 Luther was referring to debased coins of dubious value, which he identified as damaging. But note that Luther also mentioned a general shortage of small change. And when he writes of ‘small change’ being in short supply, he is referring to good small coins. Luther was reiterating an issue that had been repeatedly raised since the later fifteenth century and would continue to be a feature of the German political economy (Kameralwissenschaften) until the dissolution of the Empire in 1806.59

By the early sixteenth century the various voices had morphed into a broader set of discourses on political, imperial and religious reform, and thus the Luther Affair (Causa Lutheri) and monetary reform were both discussed at the Imperial Diets of the early 1520s. Emperor Maximilian had committed to restoring the currency to its former ‘good’ old standard.60 The first steps were taken to coordinate monetary policy across larger parts of the Empire. The larger administrative units known as Reichskreise (imperial districts) that were created in 1500/1520 would replace the late medieval currency unions (Münzvereine). The Reichskreise committed to holding regular meetings of experts, collecting samples of current coins and modes of payment, and negotiating common standards of fine weight (how much silver, gold or billon should each coin contain? What should it be worth against all other coins deemed legal for the respective Kreis?)61 Yet, until the Empire’s dissolution, hundreds of coin types and currencies continued to exist, leading to perennial monetary confusion. As late as the 1720s, government records feature the formulaic lament about how the bewildering variety of small and larger coins, foreign and domestic, old and new made payments unsafe and incomes unstable, reducing business and trade (Handel vnd Wandel).62

In his electoral capitulation (Wahlkapitulation) of 1519, the newly crowned Emperor Charles V committed to creating a unified imperial currency, as ‘our empire has suffered many woes from bad coin’.63 The issue was a weighty item on the agenda of the Imperial Diets held at Nuremberg in 1522 and 1524.64 The imperial estates now took matters of currency seriously, recognizing how they were harming the common good and thus contributing to political instability and social unrest.65 The first Imperial Currency Ordinance, issued at Esslingen, was published in autumn 1524.66 By that date, the Peasants’ War had begun.

III. Peasants’ War

When the miners of Neusohl (Banská Bystrica), Schemnitz (Banská Štiavnica) and Kremnitz (Kremnica), silver mining and metal working districts located in Slovakia today, revolted against the regional administrators of the Hungarian king in 1524, they explicitly referred to the currency debasement of 1521 as the main cause of their grievances: it had, they stated, cost them about 50 per cent of their local money’s purchasing power.67 In Tyrol, the articles of the Brixen peasants issued in May 1525 called for a ‘return to the old currency standard under Emperor Sigismund, as a means of protecting the people’.68 As we have seen, there was a tradition of unrest in Tyrol related to coins. The thirty-second article of the text issued by peasants of Meran and Innsbruck in 1525 highlighted the agio as a cause for concern, asking for ‘a good currency to be struck in the country forthwith’.69 The issue also featured in wider political programmes such as Michael Gaismair’s Tyrolean constitution of 1526, the Heilbronn ‘imperial reform’ and Friedrich Weigand’s articles.70 In south-west Germany, where complaints about coin had been frequent, especially during the Poor Conrad movement, similar grievances reappeared in 1524/25. The peasants of Eltmann, which belonged to the prince-bishopric of Würzburg, listed coin matters as their second article: they were burdened by the new currency (ain arme gemainde hoch beschwert ist).71

Peasants in nearby Münnerstadt, also in the prince-bishopric of Würzburg, noted that good, old hard money was difficult to come by; local small currencies consisted of a confusing variety of debased coins of contestable provenience and age; meanwhile the authorities insisted on payment of dues and fines in high quality money (mit Golde und dergleichen grober Münz). Farmers asked for permission to pay taxes and dues in the monies used for their everyday purchases and sales of ‘wine and bread’, the principle marketable produce in the regional peasant economy, particularly since their superiors—the Würzburg bishops—had failed to produce sound currency in the first place.72 The citizens of Würzburg, the principle city in the prince-bishopric of Würzburg, confirmed that the poor suffered the most from bad currency (die armen mit der muntz beschwert worden). Peasants had to make a variety of payments (zins, gult, rent, steuer) in new coin but according to values fixed using old currency relations, eroding their purchasing power by about a third.73 Farmers in the adjacent districts of Biburg and Neuburg had similar grievances.74

In April 1525, Upper Swabian peasants from Fürstenberg, near Constance, noted that their lords had recently required payment in Rappenmuntz rather than Schaffhausen currency, which significantly increased the burden of these payments.75 In 1525, the city council of Nuremberg responded to complaints about the overvaluing of gold currency (wirdigung oder uebertewrung des golds / hoch beschwert haben), especially in payments for local rents and dues. The council committed to accepting payment in current silver coin (Muentz) according to the statutory rate of 15 Batzens to 1 Rhenish Florin (Goldgulden) or 8 Pfunds 12 Pfennigs, and 9 Pfunds 2 Pfennigs for 1 Florin city currency (Statwerung), on the basis that this would aid the common people (in solchem dem gemainen Man auch geholffen / vnd dieselben beschwerden abgestellt werden). Similar regulations were adopted for the payment of local excises (Vngelt), which could now be paid half in gold (i.e. at an agio when not paid in Florin) and half in Muntz (i.e. current small change money valued as noted above).76 Like Nuremberg administrators, the bishop of Würzburg and the margraves of Ansbach and Bayreuth were known as serial offenders: they demanded tax payments in gold, forcing subjects to pay up to 25 per cent more than the current exchange rate if no full-bodied coins were at hand.77

Nuremberg and Augsburg were the Empire’s wealthiest cities at the time, important financial centres serving the international economy and especially the nascent Portuguese trading empire in Africa and the Indian Ocean through its silver and copper exports. Upper Germany was the engine of commercial capitalism.78 Upper German high financiers controlled European silver mining from Tyrol to the Erzgebirge, as well as metallurgy and other significant manufacturing ventures such as the Thuringian Saiger complex (one of the biggest industries of the age, where argentiferous copper from the local copper mines was separated into its component pure silver and pure copper) and thus also, as we will see in the next section, the monetary supply within the Empire (and, to an extent, silver flows to Asia). In the Alpine regions, mining districts linked to the international economy provided up to a third of European silver supply at the time. Here currency grievances in 1525 mirrored those heard in the area since the 1460s.79 The twelfth of the articles issued by the Salzburg peasants identified the agio as a usurious operation widely practised by the feudal lords of the area (gruntherrn mit wuecher understanden, aufwechsl und aufsleg zu machen).80 In 1525, in Kitzbühel, in Tyrol, peasants put the agio at the head of their list: ‘First of all we want to lodge a formal complaint about the agio [auf wechsls halben], which has been increased and increased for as long as we can remember.’81 In the district of Anras and Heinfels, feudal lords were charged with recently increasing dues, demanding payment according to the new ratio of nine fierers per kreutzer, rather than sticking to the accustomed exchange rate of six fierer per kreuzer. Those paying in ducats had seen their liabilities increase due to devaluated Bern currency (from six to 8.5 Pfunds, or pounds, Bern currency to be paid per ducat; with 1 Pfund = 20 Schillings = 240 Pfennigs).82 Further west, on 21 April 1525 peasants of Gericht Appenweier, near Strasbourg, asked for the land currency (Landmünze) to be equally accepted in payment of taxes, fees and fines (das man die munz, so im lande gemeinlichen gebrucht, die selbyg werung an betten und ungelt genomen werde).83

In the county of Mansfeld, Saiger production was one of the most technologically sophisticated industries of the time and created, in turn, a highly developed economy. Much of the prodigious quantities of copper and silver was exported via Antwerp, Lisbon and Venice into the Levant and Asiatic trades.84 Miners and smelters habitually protested about payment in ‘bad’ or ‘evil’ coins.85 Again, such complaints had been heard since the 1460s, as also in the Saxon tin and silver districts of Altenberg and Annaberg, where workers requested they be ‘paid only in the common coin minted here or coin of equal standard’.86 In 1525 the miners of Joachimsthal (today Jáchymov in the Czech Republic), another leading silver supplier, made clear the connections between silver mining, (proto)global trade, a lack of silver in situ and weak local currencies.87 Their third article pinpointed uncoined silver exports as a prime cause of the prevailing weak currency and ensuing social problems. The fourth article addressed the export of large silver Thalers equivalent in value to one Rhinegulden. These were used by only two or three merchants and financiers who sought, according to the source, ‘nothing but their own self-interest, to the harm of the miners’, who were paid in bad small coins. Miners’ money bought much less proportionally in daily trade than the much-coveted but hard-to-obtain high value silver Thalers. The sixth article identified the Zehnder (officials tasked with charging the Bergzehnt, a tithe or regalian revenue on silver mines) as pocketing huge profits from such financial manipulations.

Stemming from a dynasty of cloth merchants from the Bohemian town of Eger/Cheb, the imperial counts of Schli(c)k/Šlikové had acquired for a brief time the imperial regalian right to mint money. Around 1517 they had begun to mint large silver Thalers that emulated those produced since 1500 by the duke of Saxony and elector of Saxony, who held jointly a regalian right of coinage and usually coordinated their monetary policy. These full-bodied silver coins made a signature contribution to global monetary history for their minting marked the beginning of the end of gold as the leading currency in central Europe.88 But the miners hardly ever carried them in their own money pouches, for the Thalers were exported as soon as they sprang from the local mints. In 1525, peasants of Amt Meiningen, an exclave located within the county of Henneberg at the border between Franconia and Thuringia and held by the prince-bishopric of Würzburg, complained that they were required to pay their tax (bethe) ‘in gold’ or good coin (den sie werden ierlich mit grober munz und mit golde zu geben gedrungen) and if they did not have such coins, their small change was discounted, so they were constantly overreached.89 The articles of the town of Erfurt, which was under the archbishops of Mainz, complained about the debased penny currency minted since 1518, which was about 54 per cent underweight compared to the leading Saxon monetary standard, the principle currency in that part of Germany.90 A memorandum drawn up in late May 1525 in Aschersleben, in the prince-bishopric of Halberstadt, confirmed that when charging rents and other dues, some of the monastic landowners in the area had recently increased the ratio of local pennies to one Groschen from two to three.91 The chancellor of Count Günther von Schwarzburg, who ruled another mini-territory in central Germany, recorded similar currency manipulations in the case of debts, fines and other fees charged in local law courts, noting a ubiquitous use of ‘evil currency’ (etliche buße muntz).92 In the Imperial City of Mühlhausen, centre of Thomas Müntzer’s radical reformation, issues with bad pennies were formally documented in the city’s official complaints (Mühlhäuser Rezess) in 1525.93 As early as February 1524, so before the Peasants’ War, the peasants of the abbey of Volkenroda, in Thuringia, had refused to pay dues calculated on the newly stipulated monetary relation of eighteen (rather than eight) pennies to the Schilling; evidently the intrinsic value of the new pennies had been drastically reduced.94 Much the same was the case for the citizens of Plaue, in Thuringia, and the peasants of Käfernburg, near Arnstadt, in the county of Schwarzburg.95 And the list could continue.

But let us pause for a moment and consider the implications.

IV. Political Economies of Money in the Age of Peasant Wars (1460s–1525)

Since the fourteenth century, European peasants have demonstrated a tendency to rebel.96 Organized peasant unrest occurred as late as the 1920s, when the Schleswig Black Flag movement imitated some of the symbolism of the Peasants’ War of 1525.97 Peasant revolts need not be particularly warlike or violent. Recent scholarship has marked out the 1524/25 ‘war’ as relatively bloodless on the part of the peasants, who seem to have focused on the symbolic destruction of castles and capital assets. It was the Swabian League and its confederation army led by Georg von Waldburg-Zeil (known as Bauernjörg, or Peasant Jörg, 1488–1531) that resorted to violence in brutally crushing the revolt. (We can note that the mercenaries who fought the peasants were commonly paid in bad small change coin.)98 Uprisings were orchestrated according to praxeological patterns, with formulaic language employed in presenting grievances and complaints.99 Some historians have proposed we interpret such lists of grievances as part of a ritualized political discourse, a manifestation of a specifically premodern mode of governance that rested on confrontation as much as collaboration and conversation.100 As we have seen, peasants habitually complained about coinage (and lack thereof), and about bad coin in particular, and ‘re-establishing’ an ancient, good standard of sound currency had been on the imperial political economy agenda since the mid-fifteenth century. Monetary grievances continued after the peasant revolts had been crushed: as late as 1549 Saxon delegates to the imperial monetary conference in Speyer warned, with a now-distant memory of the Peasants’ War, that a lack of reliable small change would again ‘burden the common man and likely lead to a national [i.e. Empire-wide] revolt’.101

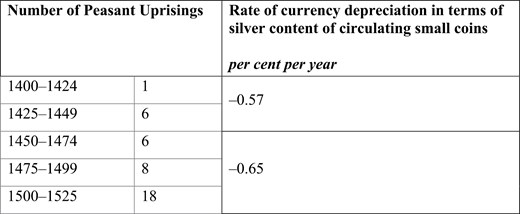

As Figure 2 indicates, although without implying causation, between 1460 and the 1520s both coin debasement rates and the number of social revolts increased. This period was also a time of political transformation, with imperial frameworks of political, religious and monetary-economic regulation strengthening alongside a rapid development of commercial capitalism and its concomitant socio-economic transformations. And then there was the Luther Affair.

Monetary deterioration and popular unrest in the German-speaking lands, 1400–1525

Source: P. R. Rössner, Deflation—Devaluation—Rebellion: Geld im Zeitalter der Reformation (Stuttgart, 2012), p. 19.

Religious, monetary and political reform became entangled. The religious schism threatened the integrity of the Empire just like monetary fragmentation and bad currency or the unfair business practices of some of the largest firms of the age, including the Fuggers, Welsers and Höchstetters, who featured large in the ‘monopoly debates’ of the 1520s. During the early 1500s and into the 1520s silver outflows from Germany increased, while Nuremberg and Augsburg firms increased their financial engagement in Venice, Lisbon and Antwerp, the biggest trading hubs in international finance and trade. The silver outflow controlled by the large Upper German trading firms financed Portuguese overseas expansion and the emerging inter-oceanic trade, leaving little monetary material in the Holy Roman Empire. Even as mining output boomed, central and southern German mints dried up, fuelling deflation (because money was in short supply) and debasement (because the money supply had to be stretched to extremes to provide a growing population with cash). This was the age before the Hispano-American silver from Potosí triggered European inflation and a so-called ‘price revolution’. The authorities faced producing no good currency or no currency altogether; either route would increase socio-economic instability. The Empire was composed of more than 300 rulers, who included electors, dukes, counts, bishops, prince-bishops, the Imperial Cities and others, all of whom could exercise the regalian right to mint coin. Governments usually tried to fix coin exchange rates, especially when new coins were issued, increasing or decreasing the amount of precious metal in the coins. But as market integration increased and old and new, foreign and local coins all circulated freely, it proved progressively more difficult to regulate to create stable relationships between types of coins circulating within (often overlapping) regional or local currency systems. Exchange rates between the larger (florin) and smaller coins (groschen, pennies, heller) were flexible, determined by type, age and provenience; whenever these rates were altered, making it profitable for traders to export overvalued (or import undervalued) coin, the market rebalanced coin valuations (‘exchange rates’) toward their equilibrium price marked by the gold–silver ratio.

As we have seen, coins were above all supposed to include at least some precious metal, in line with prevailing conceptualizations of money (a ‘metallist’ or commodity theory of money as opposed to chartalism, which comes close in many ways to modern ‘fiduciary’ concepts of money, where trust in money is decoupled from its materiality).102 Heckling and bargaining over dubious coins were frequent, but so too were coin crimes, counterfeiting and other usurious manipulations.103 Moreover, minting coins was a free-market business. Rulers had no effective control over the money supply as there were no fixed currency borders, and they could seek only to control the basic incremental parameters. How many new coins were to be struck? How many were to be Pfennigs (and other penny-type coins) rather than larger nominals such as Groschens or Thalers? Since mints were usually run, however, as profit-making enterprises, the mint masters themselves often had a free hand in determining how many coins of which denomination they produced each year. A source from Livonia noted in 1532, ‘They tend to mint whatever coin type is most profitable to them.’104 Merchants doing business in foreign locations or currency brought silver to the mint, where the mint master would transform it into current money according to a ‘mint equivalent’ (Ausbringung) set by the ruler, or ‘state’; the ‘mint price’ (Münzfuß) determined how much the mint would pay for the precious metal. The difference between mint equivalent and mint price determined the profitability of the minting business.105 Per capita silver supplies faced a protracted decline between around 1350 and 1900, with population and total economic activity in the German lands outstripping monetary growth, which created a persistent tendency for coins to become lighter over time.106

It also cost progressively more, in terms of expenses relative to new coins’ nominal value, to produce small change pennies than full-bodied Thaler. Around 1500, the mint prices and silver market structures in Saxony meant that 100 kilograms of silver could be minted into 1.7 million Hellers (half-pennies), or 637,000 Pfennigs containing between one and two grams of pure silver, or 3,571 silver Thalers (equivalent to one Goldgulden) containing about twenty-seven grams of silver fine weight. Most mints and their masters therefore preferred to produce high-value coins. When they were forced to produce at least some smaller coins for the common man, these currencies became more debased over time, containing proportionally less precious metal compared to full-bodied ‘heavy’, ‘old’ ‘good coins’. Evidence from smaller territories in the Empire such as Nassau-Idstein suggests that smaller states even used their mints to make a profit by putting out heavily debased penny-type coins and not much else. Larger silver-rich countries like Electoral Saxony and Ducal Saxony, which had considerable domestic silver supplies, had a preference, however, for heavy-weight, full-bodied ‘good’ currencies. Their profits came at a social cost: the peasant economy was under great strain in the decades when no new pennies were struck in the Saxon lands.

Catch-all explanations presented as general models struggle to capture the Empire’s multifaceted monetary history, particularly since the composition of the monetary stock—the proportions of good or full-bodied high-value coins and debased small change coins—depended upon individual actors bringing silver to the hundreds of mints.107 Coin usage and preferences for certain sorts of money also differed widely. Merchants generated a higher demand for full-bodied coin than did smaller artisans, craftsmen and the ‘common man’, who depended on small change coins. In the 1520s hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of coin types circulated in the German-speaking lands. Whatever the specific reasons, small change debasement was the norm. High-value coins had significantly lower rates of debasement over time.108

Medieval scholastic and early modern cameralist monetary theorists habitually stressed monetary stability as a prime policy goal, intended to steady, even promote, the common weal.109 Wages (usually daily wages) and the price of essentials such as bread, grain, fish and wine tended to remain static, as did regular income streams such as rents and dues, often set by contract over long-term periods. Coin debasement chiefly affected urban property owners and the rentier classes, but as we have seen, peasants also preferred reliable money, because they faced various disadvantages in the marketplace and the fiscal realm if they had to pay with unreliable, unstable and unverifiable ‘bad’ coin. Coin debasement harmed economic interests across the spectrum of medieval and early modern society, but nobles, rulers and administrators devised ways to protect themselves against the devaluation of their rent and tax revenue. Precisely these manipulations contributed to social unrest.

V. Coins, Crisis and Commercial Capitalism: Towards a Monetary Turn

Late medieval peasant (and urban) uprisings and revolts, including the Peasants’ War of 1524/25, were frequently associated with monetary matters. Currency problems were not necessarily the only or even main reason for such unrest, but currency belongs within a larger matrix of material factors and socio-economic hardships faced especially by better-off farmers in regions that after 1450 witnessed rapidly increasing market integration, commercialization and specialization. Levels of monetization had increased in the period of transformation that began with the bullion famine and economic contraction after the Black Death and ended in the age of commercial capitalism in the wake of the central European silver mining boom after 1470. When peasants complained about ‘bad coin’, they were raising political economy issues that ranged far beyond either the peasant economy or regional market systems. Their concerns were tied to international and increasingly global payments and trade, to merchants’ profits and the common weal, to spiritual salvation and commercial capitalism, even to issues of monetary capacity, state capacity and state formation that have not been covered here but should attract the attention of historians in the future.110

Until 1530 the Holy Roman Empire was the biggest silver supplier in Europe and the world. Often the entire annual silver production in Tyrol, second only to the output of Saxon-Thuringian mining, was assumed by concerns such as the Fuggers (who alone accounted for 50 per cent), Höchstetters, Welsers, Gossemprots and Imhofs in return for ever-larger financial loans to the notoriously indebted Austrian archdukes and emperors (who were also notorious for their failure to repay their loans). These firms secured a preferential right to draw on this silver at significantly below market price; they then used it to finance their businesses, which spanned from Nuremberg and Augsburg to Antwerp, Lisbon and Venice and reached on to the Indian Ocean and Chinese Sea. Production in Tyrol could only be maintained at the expense of declining marginal returns, which favoured capital concentration, as is confirmed by the constant decline in the number of individuals listed as share owners in the Tyrolean industry between 1500 and the 1530s.111

Before late capitalism turned into perversion, Joseph Schumpeter proposed in 1942, it would be marked by increasing monopolization, cartelization and exploitation of the people—all concerns that were taken up by the Imperial Diets during the 1520s.112 As some of the written grievances, complaints and printed pamphlets of the time demonstrate, peasant farmers (and urban burghers joining them in revolt) were well aware of the connections between capitalism, big business, monopoly, silver shortage and monetary problems. They often showed a clear understanding of the larger connections and political economies of capitalism, religious salvation and the common good. As monetary supply contracted and many sectors of the German economy went into depression during the first decades of the sixteenth century, these debates reflected a political economy of capitalism not on the rise, as famously claimed by R. H. Tawney, but rather in decline.113 And these monetary grievances were entangled with the wider cultural, religious and political ramifications of the early Reformation.

Footnotes

I am indebted to Prof. Joachim Whaley, two anonymous reviewers and Prof. Oliver Volckart of the London School of Economics, who all read and commented upon the manuscript of this article. All remaining errors are my own.

‘In gold’ was a contemporary financial terminus technicus denoting an enhanced exchange rate; payments in currency other than actual gold florins included an agio, or premium.

Quoted in W. Kattermann, ‘Bäuerliche Beschwerden in der Markgrafschaft Baden und dem Bühler Armen Konrad von 1514’, Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins, 95 (1943), pp. 110–205, here p. 147. All translations are mine.

For a comprehensive overview see P. Blickle, Unruhen in der ständischen Gesellschaft 1300–1800 (2nd edn, Munich, 2010), pp. 7–34; P. Blickle, ‘Bäuerliche Erhebungen im spätmittelalterlichen deutschen Reich’, Zeitschrift für Agrargeschichte und Agrarsoziologie, 27, 2 (1979), pp. 208–31. On the Arme Konrad and Bundschuh, see P. Blickle and T. Adam (eds), Bundschuh: Untergrombach 1502, das unruhige Reich und die Revolutionierbarkeit Europas (Stuttgart, 2004), and J. Dillinger, ‘Der Bundschuh von 1517: neue Quellen, eine Chronologie und der Versuch einer Revision’, Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins, 153 (2005), pp. 357–78.

For example, P. Blickle, Die Revolution von 1525 (4th edn, Munich, 2004; 1st edn, 1975), which appeared in English as P. Blickle, The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War from a New Perspective, trans. T. A. Brady and H. C. E. Midelfort (Baltimore, 1981); G. Franz, Der deutsche Bauernkrieg (11th edn, Darmstadt, 1977; 1st edn, 1933); H. Buszello, P. Blickle and R. Endres (eds), Der deutsche Bauernkrieg (3rd edn, Paderborn, 1995); R. Wohlfeil (ed.), Der Bauernkrieg 1524–26: Bauernkrieg und Reformation (Munich, 1975); B. Scribner and G. Benecke (eds), The German Peasant War of 1525: New Viewpoints (London, 1979); H.-U. Wehler (ed.), Der Deutsche Bauernkrieg 1524–1526 (Göttingen, 1975); T. Scott and R. W. Scribner (eds), The German Peasants’ War: A History in Documents (New Jersey and London, 1991). See also W.-H. Struck, Der Bauernkrieg am Mittelrhein und in Hessen: Darstellung und Quellen (Wiesbaden, 1975); E. Kuhn (ed.), Der Bauernkrieg in Oberschwaben (Tübingen, 2000); F. Dörrer, Die Bauernkriege und Michael Gaismair (Innsbruck, 1982); G. Vogler (ed.), Bauernkrieg zwischen Harz und Thüringer Wald (Stuttgart, 2008). A recent survey is G. Schwerhoff, ‘Beyond the Heroic Narrative: Towards the Quincentenary of the German Peasants’ War, 1525’, German History, 41, 1 (2023), pp. 103–26. Most recently the quincentenary has seen the publication of new works, most importantly L. Roper, Für die Freiheit: der Bauernkrieg 1525, trans. H. Fock and S. Müller (Frankfurt/Main, 2024), which appeared before the original English version: Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War (New York, 2025); G. Schwerhoff, Der Bauernkrieg: Geschichte eine wilden Handlung (Munich, 2024), and T. Kaufmann, Der Bauernkrieg: ein Medienereignis (Freiburg i. Br., 2024).

See, for example, B. Heidenreich, Ein Ereignis ohne Namen? Zu den Vorstellungen des ‘Bauernkriegs’ von 1525 in den Schriften der ‘Aufständischen’ und in der zeitgenössischen Geschichtsschreibung (Berlin, 2019), and T. T. Müller, Mörder ohne Opfer: die Reichsstadt Mühlhausen und der Bauernkrieg in Thüringen (Petersberg, 2021). In his last book Peter Blickle viewed the conflict through the eyes of the victors: P. Blickle, Der Bauernjörg: Feldherr im Bauernkrieg (2nd edn, Munich, 2022).

Schwerhoff, ‘Beyond the Heroic Narrative’. For a more detailed explanation of this view, see G. Schwerhoff, Der Bauernkrieg. For an auditory view on the Peasants’ War, see D. Hacke, ‘Hearing Cultures: Plädoyer für eine Klanggeschichte der Bauernkriege’, Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, 66 (2015), pp. 650–62, and for a new sensory view, L. Roper, ‘Emotions and the German Peasants’ War of 1524–6’, History Workshop Journal, 92 (2021), pp. 51–81.

J. Firnhaber-Baker and D. Schoenaers (eds), The Routledge History Handbook of Medieval Revolt (Abingdon, 2017).

Karl Marx–Friedrich Engels–Werke, vol. 7, pp. 330–41 (Berlin/DDR, 1960), here p. 333, available at https://archive.org/details/derdeutschebauer00enge/page/16/mode/2up; for the English translation by M. J. Olgin, published in 1926, see Works of Frederick Engels, ‘The Peasant War in Germany’, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/peasant-war-germany/index.htm.

G. Franz, ‘Die Führer im Bauernkrieg’, in G. Franz (ed.), Bauernschaft und Bauernstand 1500–1970: Büdinger Vorträge 1971–1972 (Limburg/Lahn, 1975), pp. 1–16; on the socio-economic architecture of urban revolts, see J. Smithuis, ‘Popular Movements and Elite Leadership: Exploring a Late Medieval Conundrum in Cities of the Low Countries and Germany’, in Firnhaber-Baker and Schoenaers, Routledge History Handbook, pp. 220–35.

B. Poulsen, ‘Die ältesten Bauernanschreibebücher: Schleswigsche Anschreibebücher des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts’, in K. J. Lorenzen-Schmidt and B. Poulsen (eds), Bäuerliche Anschreibebücher als Quellen zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte (Neumünster, 1992), pp. 89–105, here p. 93; W. Held, Zwischen Marktplatz und Anger: Stadt-Land-Beziehungen im 16. Jh. in Thüringen (Weimar, 1988).

G. Franz, ‘Die Entstehung der “Zwölf Artikel” der deutschen Bauernschaft’, Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte, 36 (1939), pp. 195–213; P. Blickle, ‘Nochmals zur Entstehung der Zwölf Artikel’, in P. Blickle (ed.), Bauer, Reich, Reformation: Festschrift für Günther Franz zum 80. Geburtstag (Stuttgart, 1982), pp. 286–308.

F. Irsigler, ‘Stadtwirtschaft im Spätmittelalter: Struktur—Funktion—Leistung’, Jahrbuch der Wittheit zu Bremen, 27 (1983), pp. 81–100, here p. 99; F. Irsigler, ‘Die Frage nach den Ursachen des Bauernkriegs’, in H. U. Rudolf (ed.), 475 Jahre Bauernkrieg in Oberschwaben (Ravensburg, 2000), pp. 2–15, here p. 12; F. Irsigler, ‘Der nervus rerum: Geld im Alltagsleben des späten Mittelalters’, in G. Gehl and M. Reichertz (eds), Leben im Mittelalter, vol. 3 (Frensdorf, 1999), pp. 103–18.

M. Puhle, ‘Geldpolitik und soziale Konflikte in den Hansestädten’, in S. Jenks and M. North (eds), Der hansische Sonderweg? Beiträge zur Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Hanse (Cologne, 1993), pp. 269–79, here p. 269.

W. Zimmermann, Allgemeine Geschichte des großen Bauernkrieges, part 1 (Stuttgart, 1841), pp. 124–36, discusses monetary origins of the Dutch Käsebröder revolt of 1492.

E. Westermann, ‘Der Mansfelder Kupferschieferbergbau und Thüringer Saigerhandel im Rahmen der mitteldeutschen Montanwirtschaft 1450–1620’, in W. Kroker and E. Westermann (eds), Montanwirtschaft Mitteleuropas vom 12. bis 17. Jahrhundert: Stand, Wege und Aufgaben der Forschung (Bochum, 1984), pp. 144–7, here p. 145.

P. R. Rössner, Deflation—Devaluation—Rebellion: Geld im Zeitalter der Reformation (Stuttgart, 2012), chap. 4.

O. Volckart, Die Münzpolitik im Deutschordensland und Herzogtum Preußen von 1370 bis 1550 (Wiesbaden, 1996), pp. 251–2; see also O. Volckart, The Silver Empire: How Germany Created Its First Common Currency (Oxford, 2024).

J. Bücking, Michael Gaismair: Reformer—Sozialrebell—Revolutionär. Seine Rolle im Tiroler ‘Bauernkrieg’ (1525/32) (Stuttgart, 1978), pp. 15–16.

Blickle, Die Revolution von 1525. I discussed this point with Peter Blickle in a telephone call and corresponded with him about it.

See P. R. Rössner, Managing the Wealth of Nations: Political Economies of Change in Preindustrial Europe (Bristol, 2023), chap. 5.

U. Pfister, ‘The Inequality of Pay in Pre-modern Germany, Late Fifteenth Century to 1889’, Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 60, 1 (2019), pp. 209–43, and U. Pfister, ‘Economic Growth in Germany, 1500–1850’, Journal of Economic History, 82, 4 (2022), pp. 1071–107.

On comparative German prices trends, see U. Pfister, ‘The Timing and Pattern of Real Wage Divergence in Pre-industrial Europe: Evidence from Germany, c.1500–1850’, Economic History Review, 70, 3 (2017), pp. 701–29; figure 2 on p. 709 shows a decline in the consumer price index in the German-speaking lands between 1500 and the mid-1520s.

The monopoly debates were Empire-wide deliberations and discourses about the business practices and profits of some of the bigger merchant houses and financial super-companies of the time, including the Augsburg Fugger and Welser firms, which enjoyed profits that were widely considered unjust, deemed unlawful in some cases, and generally seen as an infringement on the Common Good (der gemeine Nutzen). The charges were struck down by the emperor (who depended on these very companies for loans and other forms of financial support) with a stroke of a pen. See F. Blaich, Die Reichsmonopolgesetzgebung im Zeitalter Karls V: ihre ordnungspolitische Problematik (Stuttgart, 1967), pp. 74–81; B. Mertens, Im Kampf gegen die Monopole: Reichstagsverhandlungen und Monopolprozesse im frühen 16. Jahrhundert (Tübingen, 1996).

On the monetary implications of imperial reform and the repeated attempts at creating a unified currency, see O. Volckart, Eine Währung für das Reich: die Akten der Münztage zu Speyer 1549 und 1557 (Stuttgart, 2017), introduction, and O. Volckart, ‘Power Politics and Princely Debts: Why Germany’s Common Currency Failed, 1549–56’, Economic History Review, 70, 3 (2017), pp. 758–78.

On late medieval coins, currency and numismatics, see, for example, P. Spufford, Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe (Cambridge, 1988); R. Naismith (ed.), Money and Coinage in the Middle Ages (Boston and Leiden, 2018). For the German-speaking lands specifically, B. Sprenger, Das Geld der Deutschen: Geldgeschichte Deutschlands von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart (3rd edn, Paderborn, 2002).

R. C. Schwinges, ‘Bern, die Eidgenossen und Europa im späten Mittelalter’, in R. C. Schwinges, C. Hesse and P. Moraw (eds), Europa im späten Mittelalter: Politik—Gesellschaft—Kultur (Munich, 2006), pp. 167–89, here p. 180; J. Cahn, Münz- und Geldgeschichte der im Großherzogtum Baden vereinigten Gebiete, vol 1: Konstanz und das Bodenseegebiet im Mittelalter (Heidelberg, 1911), pp. 274–5.

G. Franz, ‘Der Salzburger Bauernaufstand 1462’, Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, 68 (1928), pp. 97–112.

In contemporary German, böse could refer interchangeably to bad, evil (even in a soteriological sense) and, in business accounting terms, to be written off (as in bad debt).

B. Koch, ‘Der Salzburger Pfennig’, Numismatische Zeitschrift, 75 (1953), pp. 36–73, here pp. 50–1; B. Koch, ‘Ein Beitrag zum Münzwesen der österreichischen Schinderlingszeit’, Numismatische Zeitschrift, 79 (1961), pp. 72–8, here p. 78; B. Koch, ‘Die mittelalterlichen Münzstätten Österreichs’, in P. Berghaus and G. Hatz (eds), Dona Numismatica: Walter Hävernick zum 23. Januar 1965 dargebracht (Hamburg, 1965), pp. 163–82, here p. 179; G. von Probszt, Die Münzen Salzburgs (Basel and Graz, 1959); R. Gaettens, Geschichte der Inflationen: vom Altertum bis zur Gegenwart (Munich, 1982), pp. 40–51; Sprenger, Das Geld der Deutschen, pp. 97–101.

Franz, ‘Der Salzburger Bauernaufstand 1462’, pp. 98–9.

Gaettens, Geschichte der Inflationen, cited after Sprenger, Das Geld der Deutschen, p. 100.

Franz, Bauernkrieg, 6th ed., pp. 31–3, 35–6. W. Köfler, Land—Landschaft—Alltag: Geschichte der Tiroler Landtage von den Anfängen bis 1808 (Innsbruck, 1985), from p. 396, and pp. 428–9. See also P. F. Barton, ‘Der vorweggenommene Bauernkrieg—der Modellfall Innerösterreich’, in P. F. Barton (ed.), Sozialrevolution und Reformation: Aufsätze zur Vorreformation, Reformation und zu den ‘Bauernkriegen’ in Südmitteleuropa (Vienna, 1975), pp. 62–72. For the Tyrolean diet, see J. Egger, Geschichte Tirols von den ältesten Zeiten bis zur Neuzeit, vol. 2 (Innsbruck, 1876), p. 55; for Brixen, see H. Wopfner (ed.), Acta Tirolensia: urkundliche Quellen zur Geschichte Tirols, vol. 3: Quellen zur Geschichte des Bauernkriegs in Deutschtirol 1525, part 1 (Innsbruck, 1908), p. 32, n. 2.

G. Franz (ed.), Der deutsche Bauernkrieg, Aktenband (Munich and Berlin, 1935), documents various regional complaints.

But see T. J. Sargent and F. R. Velde, The Big Problem of Small Change (Princeton, 2003). See R. Aulinger (ed.), Der Reichstag zu Worms 1545, vol. 2, no. 85 (Berlin, 2003), p. 943, for a discussion of the matter at the Diet of Worms in 1545.

J. Schüttenhelm, Der Geldumlauf im südwestdeutschen Raum vom Riedlinger Münzvertrag 1423 bis zur ersten Kipperzeit 1618: eine statistische Münzfundanalyse unter Anwendung der elektronischen Datenverarbeitung (Stuttgart, 1987), p. 191; A. Häberle, Ulmer Münz und Geldgeschichte des Mittelalters (Ulm, 1935), pp. 54–5, 66–7; A. Wrede (ed.), Deutsche Reichstagsakten, jüngere Reihe: deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Kaiser Karl V, vol. 3 (Munich, 1963; 1st edn, 1901), pp. 610–11 (Nr. 105, 8 Oct. / 15 Nov. 1522).

Franz, Bauernkrieg / Aktenband, pp. 29, 36–7.

Ibid., p. 70.

A. Schmauder, Württemberg im Aufstand: Der Arme Konrad 1514. Ein Beitrag zum bäuerlichen und städtischen Widerstand im Alten Reich und zum Territorialisierungsprozeß im Herzogtum Württemberg an der Wende zur frühen Neuzeit (Leinfelden-Echterdingen, 1998), pp. 199–200; W. Ohr and E. Kober (eds), Württembergische Landtagsakten, 1498–1515 (Stuttgart, 1913), p. 178.

Ohr and Kober, Württembergische Landtagsakten, p. 202. On definitions of ‘common good’, see, for example, R. Klump and L. Pilz, ‘Leonhard Fronsperger (1520–c.1575) as an Early Apology of the Market Economy’, in E. S. Reinert and P. R. Rössner (eds), Fronsperger and Laffemas: 16th-century Precursors of Modern Economic Ideas (London and New York, 2023), pp. 79–128.

Kattermann, ‘Bäuerliche Beschwerden’, p. 131.

‘erstlich das ir f. dt. die einreysenden muntzen als patzen etc. ab(zu)stellen seien’, Franz, Bauernkrieg / Aktenband, p. 133.

See E. Helleiner, The Making of National Money: Territorial Currencies in Historical Perspective (Ithaca, NY, and London, 2003), chap. 1, esp. pp. 23–7.

H. Günter, Das Münzwesen in der Grafschaft Württemberg (Stuttgart, 1897), p. 40, n. 1.

In economic terms such disagreement increased transaction costs, with a negative impact on market efficiency.

A. Wrede (ed.), Deutsche Reichstagsakten, jüngere Reihe: deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Kaiser Karl V, vol. 1 (Munich, 1963; 1st edn, 1901), p. 469 (25 July 1522).

Reformatio Sigismundi, quoted after H. Koller (ed.), Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Staatsschriften des späteren Mittelalters, vol. 6: Reformation Kaiser Siegmunds (Stuttgart, 1964), p. 346.

K. H. Lauterbach (ed.), Der oberrheinische Revolutionär: das Buchli der hundert Capiteln mit XXXX Statuten (Hanover, 2009); A. Franke (ed.), Das Buch der Hundert Kapitel und der Vierzig Statuten des sogenannten Oberrheinischen Revolutionärs (Berlin [East], 1966), pp. 181–529, here p. 383.

Cahn, Münz- und Geldgeschichte, vol. 1, pp. 352–3.

Weigand’s reform programme is available at Deutsche Geschichte in Dokumenten und Bildern (DGDB), Von der Reformation bis zum Dreißigjährigen Krieg (1500–1648), Friedrich Weigandts Reichsreformentwurf (18. Mai 1525), https://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=4326, and can also be accessed in English translation. On the context for Weigand’s text, see K. Arnold, ‘“damit der arm man vnnd gemainer nutz iren furgang haben...: Zum deutschen “Bauernkrieg” als politischer Bewegung: Wendel Hiplers und Friedrich Weygandts Pläne einer “Reformation” des Reiches’, Zeitschrift für historische Forschung, 9, 3 (1982), pp. 257–313; most recently, Volckart, Silver Empire, pp. 53–9.

Dokumente aus dem Deutschen Bauernkrieg: Beschwerden, Programme, theoretische Schriften (Leipzig, 1974), pp. 272–8, available at http://www.bauernkriege.de/gaismair.html.

Volckart, Eine Währung, introduction.

O. Volckart, ‘The Dear Old Holy Roman Realm: How Does It Hold Together? Monetary Policies, Cross-cutting Cleavages and Political Cohesion in the Age of Reformation’, German History, 38, 4 (2020), pp. 365–86, here p. 375.

H. A. Oberman (ed.), Gabrielis Biel, Collectorium circa quattuor libros Sententiarum (Tübingen, 1977).

For example, Christoph Kuppener/Cuppener, Ein schons Buchlein czu deutsch, doraus ein itzlicher mensche... lerne[n] mag. was wucher und wucherische he[n]del sein (Leipzig, 1508), unpaginated; Tractat M. Cyriaci Spangenberg vom rechten Brauch und Mißbrauch der Muentze, in M. Tilemann[us], Muentz Spiegel […] (Frankfurt/Main, 1592).

D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesammtausgabe (Weimar Ausgabe), vol. 30, part 1 (Weimar, 1910), p. 206.

D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesammtausgabe (Weimar Ausgabe), vol. 6 (Weimar, 1888), p. 49. For an extended commentary on the treatise see P. R. Rössner, Martin Luther on Commerce and Usury (London and New York, 2015), introduction.

The letter is held by the Landesarchiv Thüringen, Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar (henceforth ThHStA Weimar), Reg. N, pag. 109, Nr. 42 2D2, fols 2–3.

This term was occasionally also used to refer to Irish people and people from northern England, usually itinerant traders and pedlars.

P. R. Rössner, ‘Monetary Theory and Cameralist Economic Management, c.1500–1900 A.D.’, Journal for the History of Economic Thought, 40, 1 (2018), pp. 99–134.

H. Zeibig, ‘Der Ausschuss-Landtag der gesammten Österreichischen Erblande zu Innsbruck 1518’, Archiv für Kunde österreichischer Geschichtsquellen, 13 (1854), pp. 201–366, here p. 327.

G. Schön, ‘Die Münzprobationstage im Alten Reich’, in R. Cunz, U. Dräger and M. Lücke (eds), Interdisziplinäre Tagung zur Geschichte der neuzeitlichen Metallgeldproduktion: Projektberichte und Forschungsergebnisse, part 1 (Braunschweig, 2008), pp. 465–98, here p. 468; P. Arnold, ‘Die Reichskreise und ihre Bedeutung für die deutsche Münzgeschichte der Neuzeit’, in B. Kluge and B. Weisser (eds), XII. Internationaler Numismatischer Kongress Berlin 1997, Akten—Proceedings—Actes, vol. 2 (Berlin, 2000), pp. 1109–20.

E.g. Der Dreyen Im Muentz-Wesen Correspondierenden Hochloeblichen Fraenck= Bayer= und Schwaebischen Crayßen zu Nuernberg aufgerichteter Muentz-Abschied (7 Mar. 1724, gedruckt bey Adam Jonathan Felßecker, 1725), Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden 10025 Geheimes Konsilium Loc. 5376/08, f. 8, f. 147.

Wahlkapitulation Karl V (1519), quoted after W. Burgdorf (ed.), Die Wahlkapitulationen der römisch-deutschen Könige und Kaiser 1519–1792 (Göttingen, 2015), p. 30 (Art. XXVII).

Citatio Fiscalis Procuratoris 1524, ThHStA Weimar, Reg. U, pag. 3 Nr. 1.4 (alte Klassifikation), fol. 1.

Wrede, Deutsche Reichstagsakten, vol. 3, pp. 554–644; vol. 4, pp. 467–524.

See Volckart, Eine Währung.

P. Kalus, Die Fugger in der Slowakei (Augsburg, 1999), pp. 100–39, esp. pp. 100–1.

Cited after A. Bischoff-Urack, Michael Gaismair: ein Beitrag zur Sozialgeschichte des Bauernkrieges (Innsbruck, 1983), p. 117.

Wopfner, Acta Tirolensia, vol. 3, part 1, p. 56.

W. Lenk (ed.), Dokumente aus dem deutschen Bauernkrieg: Beschwerden, Programme, theoretische Schriften (Leipzig and Frankfurt/Main, 1983), p. 153 (Weigand), p. 159 (Heilbronn imperial reform). Michael Gaismair’s Tyrolean Constitution (Landesordnung) cited after G. Franz (ed.), Quellen zur Geschichte des Bauernkrieges (Darmstadt, 1963), no. 92, pp. 289–90.

A. Schäffler and T. Henner (eds), Die Geschichte des Bauern-Krieges in Ostfranken von Magister Lorenz Fries, 2 vols (Würzburg, 1883), vol. 2, p. 56.

Grievances of the Münnerstadt Peasants, 21 Apr. 1525, in Lenk, Dokumente, p. 127.

M. Wieland (ed.), Martin Cronthal, Die Stadt Würzburg im Bauernkriege, nebst einem Anhang: Geschichte des Kitzinger Bauernkriegs von Hieronymus Hammer (Würzburg, 1887), p. 32; Schäffler and Henner, Die Geschichte des Bauern-Krieges in Ostfranken, vol. 1, pp. 104–6.

Schäffler and Henner, Die Geschichte des Bauern-Krieges in Ostfranken, vol. 2, p. 20.

F. L. Baumann (ed.), Akten zur Geschichte des Deutschen Bauernkrieges aus Oberschwaben (Freiburg i. Br., 1877), pp. 210–11. Note that Schaffhausen had joined the Rappenmünzbund in the later fourteenth century; see J. Cahn, Der Rappenmünzbund: eine Studie zur Münz- und Geldgeschichte des oberen Rheintales (Heidelberg, 1901).

Nuremberg had several monies of account, one of which was the traditional Pfund; see G. Schön, ‘Münz- und Geldgeschichte der Fürstentümer Ansbach und Bayreuth im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert’ (PhD Thesis, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 2008), p. 80.

M. Wieland (ed.), Die Stadt Würzburg im Bauernkriege von Martin Cronthal, Stadtschreiber zu Würzburg. Nebst einem Anhang: Geschichte des Kitzinger Bauernkriegs von Hieronymus Hammer, Bürger von Kitzingen (Würzburg, 1887), p. 32.

See H. Heller, The Birth of Capitalism: A Twenty-First-Century Perspective (London and Black Point, NS, 2011); J. Banaji, A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism (Chicago, 2020). An older milestone work was Autorenkollektiv [A. Laube, M. Steinmetz and G. Vogler], Illustrierte Geschichte der frühbürgerlichen Revolution (Berlin [East], 1982). Both Heller and Banaji deploy a Marxist framework of analysis but view commercial capitalism as a capitalism on its own, not a Marxian prelude to modern industrial capitalism. See also K. Yazdani and N. Mohajer, ‘Reading Marx in the Divergence Debate’, in B. Zachariah, L. Raphael and B. Bernet (eds), What’s Left of Marxism: Historiography and the Possibilities of Thinking with Marxian Themes and Concepts (Berlin and Boston, 2020), pp. 173–240, and D. Menon and K. Yazdani (eds), Capitalisms: Towards a Global History (Oxford, 2020). While a Marxist perspective may not be considered suitable by everyone for understanding economic change around 1500, most non-Marxist histories of capitalism notably dismiss or downplay Upper German commercial capitalism around 1500 and its impact on social and economic development. See, for example, J. Kocka, Capitalism: A Short History (Princeton, 2016); L. Neal and J. Williamson (eds), The Cambridge History of Capitalism, vol. 1 (Cambridge, 2015); and G. Hodgson, Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago, 2015).

For the silver supply from this region, see tables and discussion in J. Munro, ‘The Monetary Origins of the “Price Revolution”’, in D. O. Flynn, A. Giráldez and R. von Glahn (eds), Global Connections and Monetary History, 1470–1800 (Aldershot and Burlington, VT, 2003), pp. 1–34.

A. Hollaender, ‘Die vierundzwanzig Artikel gemeiner Landschaft Salzburg 1525’, Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, 71 (1931), pp. 65–88, here p. 84.

F. Steinegger and R. Schober (eds), Die durch den Landtag 1525 (12. Juni – 21. Juli) erledigten ‘Partikularbeschwerden’ der Tiroler Bauern (Tiroler Landesarchiv, Handschriften Nr. 2889) (Innsbruck, 1976), p. 35.

Ibid., pp. 52, 54, 76.

Franz, Bauernkrieg / Aktenband, p. 367.

See E. Westermann, Das Eislebener Garkupfer und seine Bedeutung für den europäischen Kupfermarkt 1460–1560 (Cologne, 1971); E. Westermann, ‘Die Bedeutung des Thüringer Saigerhandels für den mitteleuropäischen Handel an der Wende vom 15. zum 16. Jahrhundert’, Jahrbuch für die Geschichte Mittel- und Ostdeutschlands, 21 (1972), pp. 47–65; E. Westermann, ‘Silberproduktion und -handel: mittel- und oberdeutsche Verflechtungen im 15./16. Jahrhundert’, Neues Archiv für sächsische Geschichte, 68 (1997/98), pp. 47–65. To understand the commercial entanglement of German mining, finance and global trade, Westermann should be read in conjunction with I. Blanchard, International Lead Production and Trade in the ‘Age of the Saigerprozess’ (Stuttgart, 1995), and I. Blanchard, The International Economy in the ‘Age of the Discoveries’, 1470–1570: Antwerp and the English Merchants’ World (Stuttgart, 2009).

E. Paterna, Da stunden die Bergkleute auff: die Klassenkämpfe der mansfeldischen Bergarbeiter im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert und ihre ökonomischen und sozialen Ursachen, 3 parts in 2 vols (Berlin [East], 1960), vol. 1, pp. 160–4; vol. 2, p. 277.

Dietrich, Untersuchungen, pp. 143–210, here pp. 189, 197. On the Annaberg miners see W. P. Fuchs (ed.), Akten zur Geschichte des Bauernkrieges in Mitteldeutschland, vol. 2 (Jena, 1942), Nr. 1659 (p. 475).

For the social ramifications of the miners’ revolts, see U. Schirmer, ‘Das Erzgebirge im Ausstand: die Streiks in den Revieren zu Freiberg (1444–1469), Altenberg (1469), Schneeberg und Annaberg (1496–1498) sowie in Joachimsthal (1517–1525) im regionalen Vergleich’, in A. Westermann and E. Westermann (eds), Streik im Revier: Unruhe, Protest und Ausstand vom 8. bis 20. Jahrhundert (St. Katharinen, 2007), pp. 65–94, here pp. 81–7.

M. North, Das Geld und seine Geschichte: vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart (Munich, 1994), pp. 67–76.

Schäffler and Henner, Die Geschichte des Bauern-Krieges in Ostfranken, vol. 2, pp. 201–2.