-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Emilie Fréalle, Christophe Noël, Eric Viscogliosi, Daniel Camus, Eduardo Dei-Cas, Laurence Delhaes, Manganese superoxide dismutase in pathogenic fungi: An issue with pathophysiological and phylogenetic involvements, FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, Volume 45, Issue 3, September 2005, Pages 411–422, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsim.2005.06.003

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Manganese-containing superoxide dismutases (MnSODs) are ubiquitous metalloenzymes involved in cell defence against endogenous and exogenous reactive oxygen species. In fungi, using this essential enzyme for phylogenetic analysis of Pneumocystis and Ganoderma genera, and of species selected among Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Zygomycota, provided interesting results in taxonomy and evolution. The role of mitochondrial and cytosolic MnSODs was explored in some pathogenic Basidiomycota yeasts (Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii, Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii, Malassezia sympodialis), Ascomycota filamentous fungi (Aspergillus fumigatus), and Ascomycota yeasts (Candida albicans). MnSOD-based phylogenetic and pathogenic data are confronted in order to evaluate the roles of fungal MnSODs in pathophysiological mechanisms.

1 Introduction

Diversity in clinical manifestations of mycoses (superficial, allergic, primary or opportunistic systemic infections), and fungal pathogenic species repartition among Zygomycota, Basidiomycota, or Ascomycota, indicate both a clinical and a phylogenetic diversity in human pathogenic fungi.

In spite of this diversity, all these primary or opportunistic pathogenic fungi have to face the first line of host defence against fungal infection: oxidative stress in phagocytes. Evolution of antioxidant system could therefore be a key process determining fungal adaptation and resistance in the host environment, contributing to the emergence of pathogenicity among fungi.

Many enzymatic, e.g., catalase, glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase (SOD), and non-enzymatic systems, e.g., melanin and mannitol, participate to reactive oxygen species (ROS) elimination [1]. In enzymatic antioxidant systems, one monofunctional enzyme is often encoded by multigene families, with each isoform differently regulated or located. For example, in Aspergillus fumigatus, three catalases have been reported: the conidial catalase, encoded by the catA genes [2], and the two mycelial catalases encoded by cat1/catB[3] and cat2[2], respectively. Four more catalases homologues to cat1/catB and cat2 have been detected in the genome of A. fumigatus.

In SODs (EC 1.15.1.1), redundancy is even more evident.

These ubiquitous metalloenzymes, catalyzing the dismutation of toxic superoxide anions into hydrogen peroxide, have three main isoforms, depending on their metal cofactor: manganese- (MnSOD), iron- (FeSOD), or copper/zinc- (Cu/ZnSOD) SODs. Mn- and Fe-SODs share a similar sequence and structure [4], but they are unrelated to Cu/ZnSODs [5,6]. MnSODs (product of the SOD2 gene) are located in the mitochondrial matrix, while Cu/ZnSODs (product of the SOD1 gene) were initially thought to reside in the cytosol [7]. Recently, Cu/Zn has also been found to reside in the mitochondrial intermembrane space of some fungi as well [8,9]. Fungal SOD diversity is based on: (i) the structure and metal cofactor: fungi typically have both a mitochondrial MnSOD and a cytosolic Cu/ZnSOD, (ii) the gene redundancy in each SOD family. For example, two MnSOD and four Cu/ZnSOD genes were recently found in Candida albicans completely sequenced genome [10,11].

2 MnSOD: a major role in oxidative or temperature-induced stress

In eukaryotes, MnSODs are usually homotetrameric mitochondrial metalloenzymes [12]. Expression of sod2 and phenotype of sod2 mutants explored in model organisms (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Saccharomyces pombe), and in some pathogenic fungi (Cryptococcus neoformans, C. albicans) supported the role of MnSOD in oxidative stress and high temperature conditions, two major stresses encountered by pathogenic fungi in the host environment.

2.1 MnSOD: scavenging endogenous and exogenous superoxide anions produced in oxidative stress

Fungi, like all aerobic organisms, are exposed to endogenous superoxide anions generated by the leakage of electrons onto O2 from various components of the cellular electron transport chain during natural metabolic conditions. Mitochondria, where 90% of the O2 is consumed, and the endoplasmic reticulum are the two major compartments where endogenous superoxide accumulation occurs [13]. Therefore, usual mitochondrial localization of MnSOD makes endogenous ROS the primary target of this SOD isoform. In C. neoformans var. gattii, SOD2 rather than SOD1 was shown to be essential for survival during the stationary phase, when mitochondrial formation of ROS is especially increased. In fact, 98% of C. neoformans var. gattii sod2 deletional mutant in stationary phase, versus 10% of wild-type cells, lost viability in 3 days [14], whereas sod1 mutant cells did not show viability loss in the same conditions [15]. In C. albicans, both mitochondrial (SOD2) and cytosolic MnSOD (SOD3) could also play a role during the stationary phase since their expression was increased, while SOD1 expression decreased [10,16,17].

MnSOD role in organisms facing exogenous oxidative ROS, and especially superoxide overproduction, were also explored, using artificial oxidative stressors such as menadione, paraquat or H2O2. The role of MnSOD was deduced from the SOD2 increased expression after exposure to menadione in S. pombe[18,19], Penicillium chrysogenum[20], or S. cerevisiae[21]. Furthermore, sod2 mutants were more sensitive than wild-type to menadione [14,18,21,22], paraquat [14,18,22–25], and other oxidant agents, such as plumbagin, a menadione derivative [18]. After exposure to hydrogen peroxide, neither an enhanced MnSOD expression or a sod2 mutant growth inhibition were observed in S. pombe[18], suggesting SOD2 is not involved in resistance to H2O2 induced stress.

Even if they are experimentally useful, these agents provide just a simulation of oxidative stress undertaken by fungal cells in natural conditions. In vitro exposure of fungi to the phagocytic activity of macrophages or neutrophils, which is rarely reported, is closer to the in vivo model. Results from the two methods can be divergent. In C. neoformans var. gattii, sod2 mutant did not show an increased sensitivity to killing by human neutrophils, even if sod2 mutant was sensitive to menadione or paraquat [14].

2.2 Heat shock

Growth at 37 °C is a determinant character in fungal pathogenicity. Fungi are often exposed to several stresses simultaneously, like in the host, where they are exposed to both an increased temperature, and to ROS generated by phagocytes. The development of common response pathways could explain the close correlation between heat shock and oxidative stress responses [26,27]. In addition, at higher temperature, an increased metabolism could lead to a greater consumption of molecular oxygen and greater production of ROS, with accumulation in mitochondria [27].

In C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. grubii, SOD2 essential role in adaptation to grow at elevated temperature was clearly demonstrated by (i) an induced SOD2 expression in C. neoformans var. gattii upon shift from 30 to 37 °C (fivefold upregulation) [14], (ii) a marked growth inhibition of a sod2 mutant of both species at 37 °C [14,23]. No loss of viability was observed in sod2 mutant strains incubated at 37 °C under low oxygen concentration [14] or anaerobic conditions [23], showing sod2 mutant increased thermosensitivity was oxygen dependent. This observation confirmed the close relationship between oxidative and temperature stress pathways.

SOD2 participation to the heat shock-induced SOD response is dominant in C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. grubii, since sod1 mutant did not show any growth defect at 37 °C [15,28]. C. albicans sod2 mutant sensitivity to high temperature (43 °C) was also reported [22].

3 MnSOD for fungal phylogeny: taxonomic and evolutionary data

Fungal taxonomy, for a long time, was mainly based on morphological characters, leading to a complex, controversial and incomplete classification. This resulted mostly from: (i) the fact that macroscopic and microscopic characters could fail to differentiate closely related species (e.g., Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex, Ganoderma lucidum complex); (ii) the existence of two morphological forms, asexual (anamorph) and sexual (teleomorph, frequently unknown), with different names, in the same species; (iii) the difficulty to determine the taxonomic position within Asco-, Basidio-, or Zygomycota of species whose teleomorph is unknown, which were classified on the basis of their anamorph within the Deuteromycota; (iv) the impossibility to determine the taxonomic position of fungi whose culture in vitro is difficult (e.g., Lacazia loboi[29]).

Phylogenetic studies using molecular sequence data, mainly ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences, provided an alternative to morphological-based taxonomy and highly contributed to clarify the complex taxonomy and evolution of these eukaryotes [30–32]. Furthermore, they provided precious information on fungal rRNA gene sequences, further used for he development of molecular methods for identification of fungi [33–36]

However, since congruence between several phylogenies is needed to confirm classical rRNA genes data, many other phylogenetic markers were explored: internal transcribed regions (ITS) [37], or protein-coding genes such as cytochrome b[38], RPB1, RPB2, EF2 or ACT1 [39], translation elongation factor 1 alpha, actin-1, RNA polymerase II, cytochrome oxidase II [40]. MnSOD is one of the protein-coding genes used in taxonomy and phylogenetic fungal studies. Interesting results were obtained in Ganoderma[41], and Pneumocystis genera [42], and in fungi selected in Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Zygomycota [43, Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted]. Furthermore, the molecular phylogeny of essential enzymes helped to understand their evolution, interrelationships and functions [43, Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted].

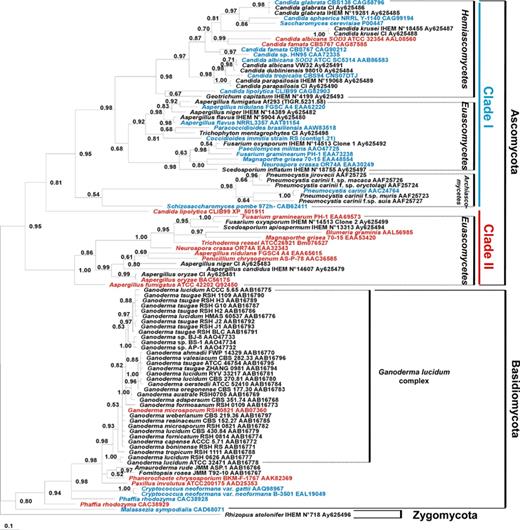

The 99 MnSOD amino acid sequences, corresponding to these studies, were aligned using the BioEdit v7.0.1 program (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu:BioEdit/bioedit.html), and the MnSOD-based phylogenetic tree synthetizing the results of these studies (Fig. 1) was built using maximum parsimony in MrBAYES 3_0b4 program [44], as previously described [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted].

Consensus Bayesian tree of fungi inferred from MnSOD protein sequences. R. stolonifer served as outgroup. Accession numbers or references of the sequences retrieved from genome sequencing projects are shown after each species. The predicted cytosolic or mitochondrial subcellular localization of fungal MnSODs is indicated in red and blue, respectively. Numbers near the individual nodes indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities given as percentages. Nodes with values of <50% are not shown. Scale bar, 0.1 substitutions (corrected) per site.

3.1 MnSOD sequences: alignment and phylogenetic information

MnSOD sequence variability is much higher than 18S rRNA one, probably reflecting a weaker selective pressure on the MnSOD gene. For example, identity between homologous A. fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus flavus MnSOD gene sequences ranges from 73.1% to 79.9%, whereas SSU rRNA sequence identity exceeds 98.4% [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted].

With protein-coding genes, either nucleotide or protein sequences can be used. In the Pneumocystis study, trees inferred from 15 protein or nucleotide sequences yielded the same topology [42]. cDNA nucleotide sequences were used to build the Ganoderma tree [41], and protein sequences were used to build the two others MnSOD trees [43, Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted]. Using protein rather than nucleotide sequences avoid (i) intron interference: exons and introns undergo different evolutionary pressures, leading to a different rate of incorporation of base substitutions, which does not reflect the protein evolution, and (ii) wrobble base degeneracy interference. Aligning deduced amino acid sequences (20 amino acids) rather than DNA sequences (4 nucleotides) will also improve the quality of the alignment since sequences are shorter and much easier to align, and the information will sharpen up considerably [45]. When nucleotide sequences have high identity rates, like in the Ganoderma study, where sequences U56106–U56137 (GenBank Accession Nos.) had over 79.5% identity, unambiguous alignment is possible [41].

Interestingly, although MnSOD protein sequences are shorter than 18S rRNA nucleotide sequences they exhibit higher variability and enough informative sites for phylogenetic analysis. For example, in the recent study comparing MnSOD and SSU rRNA-based phylogenies of pathogenic fungi, 131 and 1260 sites from MnSOD and SSU rRNA sequences were used, respectively, showing that shorter sequences could provide more phylogenetic information [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted].

3.2 High variability of MnSOD sequences: usefulness for taxonomy of closely related species and genotyping

Another advantage of using MnSOD for phylogeny is that highly divergent MnSOD sequences allow closely related species differentiation. In the Pneumocystis genus, MnSOD-based phylogeny confirmed the existence of host-specific species, already supported by 18S rRNA sequence heterogeneity, together with phenotypic variability among the different host-derived Pneumocystis carinii isolates [46–48]. In Denis et al., Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis P. carinii f. sp. macacae, P. carinii f. sp. oryctolagi, P. carinii f. sp. muris, P. carinii f. sp. suis, and rat-derived P. carinii formed a monophyletic group within fungi. Grouping of P. carinii f. sp. hominis (=P. jirovecii) and P. carinii f. sp. macacae with P. carinii f. sp. oryctolagi was even clearer using the MnSOD than the 18S rRNA sequences. However, the position of P. carinii f. sp. suis was not better resolved (BPP 40%) [42]. In Fig. 1, using more MnSOD sequences resulted in P. carinii f. sp. suis clustering with P. carinii f. sp. muris and rat-derived P. carinii (BPP 64%).

Within the Basidiomycota Ganoderma genus, regarded as an herb of longevity in Orient, MnSOD-based phylogenetic analysis of 28 Ganoderma isolates of the G. lucidum complex (whose taxonomic relationships failed to be clarified by conventional taxonomy) exhibited 5 groups, like in ITS- and LSU rRNA-based analysis [41]. Fig. 1 confirms morphological and cultural characters based-species identification fails to recognize monophyletic groups.

A polymorphism of the MnSOD gene in G. lucidum and G. tsugae was observed [41]. In P. jirovecii, two genotypes were identified at the SOD locus: one with C/T and the second with T/C at positions 110/215 [49–51].

3.3 MnSOD for large taxonomic studies

A phylogenetic analysis of MnSODs mainly including plants (18 sequences), fungi (15 sequences) and prokaryotes (58 sequences) [43], and a recent comparison of MnSOD- and SSU rRNA-based phylogenies including Zygomycota, Basidiomycota and Ascomycota species [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted] confirmed MnSOD could be used for large phylogenetic studies in fungi. In the first study, 15 fungal MnSOD sequences (8 Basidiomycota and 7 Ascomycota) were included. Basidiomycota species clustered together. In Ascomycota, Euascomycetes (3 species) and Hemi/Archiascomycetes (4 species) were in 2 different clades. The overall topology of the tree closely reflected the taxonomic classification [43]. The second study only targeted fungi and included 61 MnSOD sequences: 1 Zygomycota, 9 Basidiomycota, and 51 Ascomycota sequences [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted]. On this tree, like in Fig. 1, the ancestral Zygomycota Rhizopus stolonifer was used as an outgroup, and Basidiomycota and Ascomycota both formed strongly supported monophyletic groups. In Ascomycota, two highly supported clades were found. The topology of the “clade I” was largely congruent with the Ascomycota classical SSUrRNA tree, suggesting MnSOD could be used for further phylogenetic studies in fungi. In this clade, the MnSOD-based phylogeny confirmed the early emergence of Pneumocystis spp. within Ascomycota. The “clade II” in Ascomycota was clearly resolved, and contained paralogous Euascomycetes MnSOD sequences (Fig. 1). Predicted localization of these MnSOD sequences supported an unusual cytosolic localization for the corresponding proteins, suggesting that many Euascomycetes had both a mitochondrial and a cytosolic MnSOD. Some Hemiascomycetes also had both a mitochondrial and a cytosolic MnSOD, resulting either from an early (Candida lipolytica) or a late duplication (C. albicans and Candida famata), as shown by low (41.9%) or high (63.3% and 74.0%, respectively) identity rates between the two paralogous sequences.

3.4 Cytosolic/mitochondrial MnSODs in fungi: a complex evolutionary history

The MnSOD-based phylogenetic analysis of fungi contributed to understand the complex evolutionary history of this gene within fungi, where (i) multiple early or late duplication of the MnSOD genes, (ii) loss of the mitochondrial targeting peptide in the course of evolution in numerous fungi, leading to a cytosolic localization of the MnSOD, occurred. Consequently, many fungi express both Cu/ZnSOD and MnSOD in the cytosolic compartment, whereas a second MnSOD protects the mitochondrial compartment against ROS [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted].

4 From MnSOD genes to protein characterization; pathophysiological involvements

Among these 99 MnSOD sequences currently reported in the databases and used for the previously cited phylogenetic analyses, only 14 have been characterized so far (Table 1). Other sequences are putative MnSOD sequences, predicted to encode MnSOD proteins, based on sequence homology and presence of characteristic residues: tetrameric and iron/manganese-binding amino acids [4,52].

| Fungal strain (GenBank accession number) | Protein purification, gene cloning or expression | Protein length (AA) | ORF (bp) | CDS (bp) | Intron number (size in bp) | Molecular mass (kDa), subunit/polymer | Mitochondrial targeting peptide (predicted localization) | Activity (U mg−1) | References |

| Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 42202 (U53561) | Gene cloned into BamHI/HindIII-restricted p(His)6-DHFR vector and expressed in E. coli M15 | 210 | ND | 630 | ND | 26.7/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | 2.32–2.61 | [54] |

| Candida albicans SOD2 (AF031478) | • Protein purified from culture | 234 | 702 | 702 | 0 | 26/106 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [17] |

| • Gene cloned into pGEM-T | |||||||||

| Candida albicans ATCC 32354 SOD3 (AF416340) | • Gene cloned into pQE30 and expressed in E. coli M15 | 206 | 678 | 618 | 1 (60) | 22.7/85 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 370 | [10] |

| • Gene cloned into pVT102U and expressed in S. cerevisiae | |||||||||

| Colletrichum graminicola M1.001 (AF430836) | No | 208 | 794 | 624 | 3 (51, 60, 59) | 23/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [76] |

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii ATCC 32609 (AY423630) | • Protein purified from culture | 225 | 956 | 675 | 4 (56, 120, 55, 50) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [14] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR2.1 | |||||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii H99 (AY737799) | No | 234 | 1010 | 702 | 6 (55, 58, 62, 54, 51, 28) | 19.5/80 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [23,77] |

| Ganoderma microporum RSH 0821 (U56403, U56127) | Protein purified from culture | 200 | >708 | 600 | ≥2 (65, 217) | 25/98 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 398–433 | [78] |

| Humicola lutea 110 | Protein purified from culture | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18.9/76 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [79] |

| Malassezia sympodialis ATCC 42132 (AJ548421) | Gene cloned into the pCR4 TOPO vector, subcloned into pQE30, and expressed in E. coli M15 | 237 | ND | 711 | ND | 22.4/ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [56] |

| Paxillus involutus ATCC 200175 (AF114848) | • Protein purified from culture | 206 | 859 | 618 | 3 (113, 66, 62) | 26.2/53.2 | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [53] |

| • Gene cloned into pET3d and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) | |||||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum AS-P-78 (AF026790, AF026523) | • Protein purified from culture | 210 | 747 | 630 | 2 (60,57) | 23.1/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [16] |

| • Gene cloned into pBluescript I-KS | |||||||||

| Pneumocystis carinii (AF036321) | • Protein purified from culture | 220 | 1094 | 660 | 7 (45, 54, 144, 50, 48, 47, 46) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | 2 | [80,81] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR-Script SK | |||||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae YHR008C, ChrVIII (X02156, AY557821) | • Protein purified from culture | 233 | 699 | 699 | 0 | 24/97 | Present (mitochondrial) | 7500 | [82] |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972h-, ChrI (AL133357, AF069292) | • Protein purified from culture | 219 | 780 | 657 | 1 (123) | 22/50 | Present (mitochondrial) | 940 | [18,83] |

| • Gene cloned into pET-15b and expressed in E. coli |

| Fungal strain (GenBank accession number) | Protein purification, gene cloning or expression | Protein length (AA) | ORF (bp) | CDS (bp) | Intron number (size in bp) | Molecular mass (kDa), subunit/polymer | Mitochondrial targeting peptide (predicted localization) | Activity (U mg−1) | References |

| Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 42202 (U53561) | Gene cloned into BamHI/HindIII-restricted p(His)6-DHFR vector and expressed in E. coli M15 | 210 | ND | 630 | ND | 26.7/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | 2.32–2.61 | [54] |

| Candida albicans SOD2 (AF031478) | • Protein purified from culture | 234 | 702 | 702 | 0 | 26/106 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [17] |

| • Gene cloned into pGEM-T | |||||||||

| Candida albicans ATCC 32354 SOD3 (AF416340) | • Gene cloned into pQE30 and expressed in E. coli M15 | 206 | 678 | 618 | 1 (60) | 22.7/85 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 370 | [10] |

| • Gene cloned into pVT102U and expressed in S. cerevisiae | |||||||||

| Colletrichum graminicola M1.001 (AF430836) | No | 208 | 794 | 624 | 3 (51, 60, 59) | 23/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [76] |

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii ATCC 32609 (AY423630) | • Protein purified from culture | 225 | 956 | 675 | 4 (56, 120, 55, 50) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [14] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR2.1 | |||||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii H99 (AY737799) | No | 234 | 1010 | 702 | 6 (55, 58, 62, 54, 51, 28) | 19.5/80 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [23,77] |

| Ganoderma microporum RSH 0821 (U56403, U56127) | Protein purified from culture | 200 | >708 | 600 | ≥2 (65, 217) | 25/98 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 398–433 | [78] |

| Humicola lutea 110 | Protein purified from culture | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18.9/76 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [79] |

| Malassezia sympodialis ATCC 42132 (AJ548421) | Gene cloned into the pCR4 TOPO vector, subcloned into pQE30, and expressed in E. coli M15 | 237 | ND | 711 | ND | 22.4/ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [56] |

| Paxillus involutus ATCC 200175 (AF114848) | • Protein purified from culture | 206 | 859 | 618 | 3 (113, 66, 62) | 26.2/53.2 | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [53] |

| • Gene cloned into pET3d and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) | |||||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum AS-P-78 (AF026790, AF026523) | • Protein purified from culture | 210 | 747 | 630 | 2 (60,57) | 23.1/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [16] |

| • Gene cloned into pBluescript I-KS | |||||||||

| Pneumocystis carinii (AF036321) | • Protein purified from culture | 220 | 1094 | 660 | 7 (45, 54, 144, 50, 48, 47, 46) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | 2 | [80,81] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR-Script SK | |||||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae YHR008C, ChrVIII (X02156, AY557821) | • Protein purified from culture | 233 | 699 | 699 | 0 | 24/97 | Present (mitochondrial) | 7500 | [82] |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972h-, ChrI (AL133357, AF069292) | • Protein purified from culture | 219 | 780 | 657 | 1 (123) | 22/50 | Present (mitochondrial) | 940 | [18,83] |

| • Gene cloned into pET-15b and expressed in E. coli |

ND: Not determined.

SOD activity determined according to Elstner et al. protocol [84].

SOD activity determined according to Beauchamp and Fridovich protocol [85].

SOD activity determined according to Oberley and Spitz protocol [86].

SOD activity determined according to Marklund and Marklund protocol [87].

| Fungal strain (GenBank accession number) | Protein purification, gene cloning or expression | Protein length (AA) | ORF (bp) | CDS (bp) | Intron number (size in bp) | Molecular mass (kDa), subunit/polymer | Mitochondrial targeting peptide (predicted localization) | Activity (U mg−1) | References |

| Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 42202 (U53561) | Gene cloned into BamHI/HindIII-restricted p(His)6-DHFR vector and expressed in E. coli M15 | 210 | ND | 630 | ND | 26.7/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | 2.32–2.61 | [54] |

| Candida albicans SOD2 (AF031478) | • Protein purified from culture | 234 | 702 | 702 | 0 | 26/106 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [17] |

| • Gene cloned into pGEM-T | |||||||||

| Candida albicans ATCC 32354 SOD3 (AF416340) | • Gene cloned into pQE30 and expressed in E. coli M15 | 206 | 678 | 618 | 1 (60) | 22.7/85 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 370 | [10] |

| • Gene cloned into pVT102U and expressed in S. cerevisiae | |||||||||

| Colletrichum graminicola M1.001 (AF430836) | No | 208 | 794 | 624 | 3 (51, 60, 59) | 23/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [76] |

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii ATCC 32609 (AY423630) | • Protein purified from culture | 225 | 956 | 675 | 4 (56, 120, 55, 50) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [14] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR2.1 | |||||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii H99 (AY737799) | No | 234 | 1010 | 702 | 6 (55, 58, 62, 54, 51, 28) | 19.5/80 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [23,77] |

| Ganoderma microporum RSH 0821 (U56403, U56127) | Protein purified from culture | 200 | >708 | 600 | ≥2 (65, 217) | 25/98 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 398–433 | [78] |

| Humicola lutea 110 | Protein purified from culture | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18.9/76 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [79] |

| Malassezia sympodialis ATCC 42132 (AJ548421) | Gene cloned into the pCR4 TOPO vector, subcloned into pQE30, and expressed in E. coli M15 | 237 | ND | 711 | ND | 22.4/ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [56] |

| Paxillus involutus ATCC 200175 (AF114848) | • Protein purified from culture | 206 | 859 | 618 | 3 (113, 66, 62) | 26.2/53.2 | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [53] |

| • Gene cloned into pET3d and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) | |||||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum AS-P-78 (AF026790, AF026523) | • Protein purified from culture | 210 | 747 | 630 | 2 (60,57) | 23.1/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [16] |

| • Gene cloned into pBluescript I-KS | |||||||||

| Pneumocystis carinii (AF036321) | • Protein purified from culture | 220 | 1094 | 660 | 7 (45, 54, 144, 50, 48, 47, 46) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | 2 | [80,81] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR-Script SK | |||||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae YHR008C, ChrVIII (X02156, AY557821) | • Protein purified from culture | 233 | 699 | 699 | 0 | 24/97 | Present (mitochondrial) | 7500 | [82] |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972h-, ChrI (AL133357, AF069292) | • Protein purified from culture | 219 | 780 | 657 | 1 (123) | 22/50 | Present (mitochondrial) | 940 | [18,83] |

| • Gene cloned into pET-15b and expressed in E. coli |

| Fungal strain (GenBank accession number) | Protein purification, gene cloning or expression | Protein length (AA) | ORF (bp) | CDS (bp) | Intron number (size in bp) | Molecular mass (kDa), subunit/polymer | Mitochondrial targeting peptide (predicted localization) | Activity (U mg−1) | References |

| Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 42202 (U53561) | Gene cloned into BamHI/HindIII-restricted p(His)6-DHFR vector and expressed in E. coli M15 | 210 | ND | 630 | ND | 26.7/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | 2.32–2.61 | [54] |

| Candida albicans SOD2 (AF031478) | • Protein purified from culture | 234 | 702 | 702 | 0 | 26/106 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [17] |

| • Gene cloned into pGEM-T | |||||||||

| Candida albicans ATCC 32354 SOD3 (AF416340) | • Gene cloned into pQE30 and expressed in E. coli M15 | 206 | 678 | 618 | 1 (60) | 22.7/85 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 370 | [10] |

| • Gene cloned into pVT102U and expressed in S. cerevisiae | |||||||||

| Colletrichum graminicola M1.001 (AF430836) | No | 208 | 794 | 624 | 3 (51, 60, 59) | 23/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [76] |

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii ATCC 32609 (AY423630) | • Protein purified from culture | 225 | 956 | 675 | 4 (56, 120, 55, 50) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [14] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR2.1 | |||||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii H99 (AY737799) | No | 234 | 1010 | 702 | 6 (55, 58, 62, 54, 51, 28) | 19.5/80 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [23,77] |

| Ganoderma microporum RSH 0821 (U56403, U56127) | Protein purified from culture | 200 | >708 | 600 | ≥2 (65, 217) | 25/98 | Lacking (cytosolic) | 398–433 | [78] |

| Humicola lutea 110 | Protein purified from culture | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18.9/76 | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [79] |

| Malassezia sympodialis ATCC 42132 (AJ548421) | Gene cloned into the pCR4 TOPO vector, subcloned into pQE30, and expressed in E. coli M15 | 237 | ND | 711 | ND | 22.4/ND | Present (mitochondrial) | ND | [56] |

| Paxillus involutus ATCC 200175 (AF114848) | • Protein purified from culture | 206 | 859 | 618 | 3 (113, 66, 62) | 26.2/53.2 | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [53] |

| • Gene cloned into pET3d and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) | |||||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum AS-P-78 (AF026790, AF026523) | • Protein purified from culture | 210 | 747 | 630 | 2 (60,57) | 23.1/ND | Lacking (cytosolic) | ND | [16] |

| • Gene cloned into pBluescript I-KS | |||||||||

| Pneumocystis carinii (AF036321) | • Protein purified from culture | 220 | 1094 | 660 | 7 (45, 54, 144, 50, 48, 47, 46) | ND | Present (mitochondrial) | 2 | [80,81] |

| • Gene cloned into pCR-Script SK | |||||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae YHR008C, ChrVIII (X02156, AY557821) | • Protein purified from culture | 233 | 699 | 699 | 0 | 24/97 | Present (mitochondrial) | 7500 | [82] |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972h-, ChrI (AL133357, AF069292) | • Protein purified from culture | 219 | 780 | 657 | 1 (123) | 22/50 | Present (mitochondrial) | 940 | [18,83] |

| • Gene cloned into pET-15b and expressed in E. coli |

ND: Not determined.

SOD activity determined according to Elstner et al. protocol [84].

SOD activity determined according to Beauchamp and Fridovich protocol [85].

SOD activity determined according to Oberley and Spitz protocol [86].

SOD activity determined according to Marklund and Marklund protocol [87].

Among these 14 characterized fungal MnSODs, two were reported to be homodimeric enzymes [18,53], which is rather the prokaryotic MnSOD structure, or to have a putative cytosolic localization, since they were lacking the 20–30 AA mitochondrial amino terminal targeting peptide [10,16,54, Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted].

Proteins were either purified from cultures or obtained by molecular recombination (Table 1). The MnSOD gene was either cloned and transfected in wild-type or mutant fungal strains, in order to study its regulation [10,14,17,18,23,54,55], or cloned in Escherichia coli, producing recombinant proteins whose MnSOD allergenic properties were evaluated [54,56]. Great variations in SOD activity were observed, ranging from 2 to 7500 U mg−1 (Table 1). SOD activity was not inhibited by cyanide (CN−) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), indicating these proteins were members of the MnSOD family. Actually, FeSODs are sensitive to H2O2, and Cu/ZnSODs are sensitive to both H2O2 and KCN [57].

In some pathogenic fungi, MnSOD was reported to be involved in fungal virulence [14,23,54,56]. Linking these data with MnSOD-based phylogeny could contribute to understand the different roles MnSODs play in pathogenic fungi.

4.1 SOD2 in the Basidiomycota yeast C. neoformans: a clear role in virulence

C. neoformans is a basidiomycetous yeast causing cryptococcosis, a neurotropic mycosis with pulmonary route of entry. C. neoformans var. neoformans (synonym: C. neoformans var. grubii) and C. neoformans var. gattii are two variants, diverging by their geographic repartition (cosmopolite and subtropical, respectively), and antigenic properties [58].

Only one MnSOD gene was found in C. neoformans var. neoformans JEC21 and B-3501A completely sequenced genomes [59]. It encodes for a classical mitochondrial MnSOD whose role in virulence was clearly demonstrated in C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. grubii, in two independent experiments [14,23].

In vitro, a growth inhibition of sod2 mutant at 37 °C (host temperature), or facing an oxidative or osmotic stress (supposed to occur in phagocytic cells phagosomes) was observed [14,23]. In C. neoformans var. gattii SOD2 is not required for protection against human neutrophils in vitro [14]. However, SOD2 plays an important role in the virulence of both C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. grubii, depending on the route of infection. In the intranasal infection model, SOD2 is absolutely essential for virulence since no mortality or morbidity was observed in mice infected with C. neoformans var. gattii sod2 mutant at 120 days post-infection, whereas mice infected with wild-type or sod2 ΔSOD2 reconstituted strains died by 45 days post-infection. C. neoformans var. grubii sod2 mutant was avirulent too: sod2 mutant infected mice completely cleared the fungi by day 38 post-infection and survived for up to 80 days post-infection, whereas all wild-type and sod2ΔSOD2 infected mice died 25 and 38 days post-infection, respectively [23]. In a high-dose intravenous infection model, only attenuated virulence was observed, with C. neoformans var. gattii sod2 mutant producing typical meningoencephalitis, but a delayed course of the infection (31 days compared with 12–13 days with wild-type or reconstituted strains). In a low-dose intravenous infection model, sod2 mutant was avirulent [14,15].

C. neoformans var. gattii sod1sod2 double knockout strains were even more incapacitated since they were avirulent in intranasal and incapable of producing disease in intravenous infection models, in spite of long-term survival in the brain, where a lower partial pressure of oxygen (5 kPa) than in the lung (21 kPa) may have provided advantage to its growth [14].

The results of these two studies agree with the close phylogenetic relationships of these two C. neoformans variants (the two protein MnSOD sequences AAQ98967–EAL19049 have 96% identity). MnSOD probably conserved exactly the same function in both variants.

4.2 Aspergillus fumigatus and Malassezia sympodialis MnSODs: major allergens

A. fumigatus is an Ascomycota filamentous fungi, and M. sympodialis is a Basidiomycota yeast. A. fumigatus cytosolic and M. sympodialis mitochondrial complete protein MnSOD sequences (Q92450 and CAD68071, respectively) have 45.5% identity. However, surprisingly, in these two phylogenetically distant species, MnSOD was found to have similar allergenic properties: (i) recombinant A. fumigatus MnSOD (rAsp f6) binds serum IgE from allergic patients, and more specifically in ABPA (allergic broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis), which is a severe pulmonary complication of cystic fibrosis (CF) (1–15%) or asthma (1–2%) [54,60,61], and (ii) recombinant M. sympodialis MnSOD (rMala s11) binds serum IgE from AEDS (atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome) patients, a common inflammatory skin disease that often develops in early childhood [56].

Among the 23 detected and proposed allergens of A. fumigatus[60,62], MnSOD is the only one whose cross-reactivity with human MnSOD (hMnSOD) was demonstrated, both by A. fumigatus-IgE binding inhibition when recombinant hMnSOD was added (humoral cross-reactivity), and by A. fumigatus or recombinant hMnSOD ability to provoke allergic reaction when injected to anti-MnSOD IgE producing individuals (cell-mediated cross-reactivity) [54]. Putative cross-reactive epitopes were identified by comparing the crystal structures of the two MnSODs [63]. Of the identical residues between A. fumigatus and hMnSODs, 4 were at least 30% solvent exposed in both crystal structures. Two more than 50% solvent exposed residues were identified as suitable targets for substitution by site-directed mutagenesis [63]. Cross-reactivity with MnSODs from other organisms (Drosophila melanogaster, Hevea brasiliensis, E. coli and S. cerevisiae) confirmed that MnSOD is a family of cross-reactive allergens [64,65]. M. sympodialis MnSOD (Mala s11) allergenic role supports the hypothesis of a panallergen MnSOD family [64,66]. Humoral and cell-mediated cross-reactivity with human and A. fumigatus homologues was recently found on 29 out of 69 atopic dermatitis (AD) patients, who had IgE-specific response to hMnSOD and rAsp f6, and reacted positively to skin challenges with both recombinant proteins [67].

In addition, interestingly, A. fumigatus-MnSOD targeted IgE response was found to be specific of ABPA in CF patients [61,68], since rAsp f6 was recognized by IgE from ABPA patient's sera, but not by IgE from A. fumigatus-sensitized patient's sera [69]. Colonization of the respiratory tract and sensitization by A. fumigatus (up to 60% of CF patients) has to be clearly distinguished from ABPA in CF patients, since a specific prophylaxis and treatment of acute exacerbations, and prevention of end-stage fibrotic disease with corticosteroid and antifungal therapy is critical [70]. rAsp f6, like rAsp f4, a 30-kDa cytosolic protein of unknown function, could discriminate allergic patients (no specific IgE response) and ABPA patients (significant specific IgE response) [61]. However, other allergic diseases involving MnSOD can provoke Asp f6 specific IgE significant levels, like in AD where similar mean levels were found in AD and ABPA patients [67].

Specific IgE response to the cytosolic rAsp f6 in patients with ABPA, and to Mala s11 in patients with AD suggests these two allergens are involved in specific physiopathological mechanisms [67,69]. However, when it was investigated on a murine model of ABPA, rAsp f6 failed to show any airway hyperreactivity. rAsp f6 provoked an attenuated immune and inflammatory response compared to the response of Asp f1, Asp f2 and Asp f4, three other A. fumigatus major allergens [71].

The role of A. fumigatus cytosolic and M. sympodialis mitochondrial MnSODs in defence against ROS was not explored.

4.3 Mitochondrial (SOD2) and cytosolic (SOD3) MnSODs in C. albicans

In C. albicans, an Ascomycota yeast, no virulence attenuation was observed with a sod2 mutant on a murine model of candidasis [72], suggesting C. albicans SOD2, unlike C. neoformans SOD2, is not required for virulence. The presence of six SOD genes in this species, two MnSODs and four Cu/ZnSODs [10,11], instead of two in C. neoformans var. gattii, one mitochondrial MnSOD and one cytosolic Cu/ZnSOD, could explain the differences in SOD regulation.

Four out of these six SODs have been characterized so far: SOD1, a cytosolic Cu/ZnSOD [72], SOD2, a mitochondrial MnSOD [17], SOD3, a cytosolic MnSOD [10], and SOD5, a cytosolic Cu/ZnSOD [11]. SOD1, but not SOD2, is required for pathogenicity [73]. This was supported by the gene expression profile of C. albicans in human blood, which showed that SOD1 was highly expressed in blood containing leucocytes, but not in plasma, and that SOD2 was not expressed in cells exposed to blood, but only in cultures [74]. In vitro, the advantage for C. albicans to express both a MnSOD (SOD3) and a Cu/ZnSOD (SOD1) in the cytosolic compartment could be (i) to improve resistance to oxidative stress, (ii) to modulate SOD expression according to metal ions availability in growth phases. Since no difference in paraquat or menadione sensitivity was observed, and since the two SOD regulation is inversely coordinated, resulting in a constant rather than an increased cytosolic SOD activity, no improved resistance to oxidative stress could be hypothesized. The second hypothesis seems more likely: SOD1 decreased expression during stationary phase could be related to C. albicans eliminating copper to avoid copper deleterious effects, and result in an increased SOD3 expression, as seen in Podospora anserina, where copper-depleted conditions increased SOD2 transcript levels [75]. Therefore, increased SOD3 expression could substitute for SOD1 to provide protection against ROS during stationary phase. SOD3 role in pathogenicity has not been explored yet. It could be involved in the commensal pathogen C. albicans survival in the host environment [10].

Many other pathogenic fungi express both a cytosolic and a mitochondrial MnSOD. Clustering of C. albicans and C. famata cytosolic MnSOD sequences on the MnSOD tree (66.5% identity) suggest these enzymes could have similar functions. Other Ascomycota cytosolic MnSODs (gathered in the Euascomycetes and C. lipolytica“cytosolic” clade) probably result from an early duplication, as suggested by low identity rates between paralogous sequences (41.9–49.6%) [Frealle et al., 2005, manuscript submitted]. Resulting proteins could have acquired functional specialization. A. fumigatus cytosolic MnSOD showed allergenic properties, but the role of both a Cu/ZnSOD and a MnSOD in the cytosolic compartment has not been explored. Further studies should be directed to determine the role of these two MnSODs in so many phylogenetically distant species, and if they are involved in pathogenicity.

5 Conclusion

MnSOD role in pathogenic fungi is poorly known. It was only explored in four phylogenetically distant pathogenic fungi. Differences in MnSOD gene regulation, function, subcellular localization, or role in fungal virulence were not correlated to the phylogenetic position of the fungi. Since defence against ROS is determinant for pathogenicity, MnSOD evolutionary history and pathophysiological roles in invasive or allergic mycoses agree with the hypothesis that pathogenicity emerged multiple times within fungi.

References

Author notes

Present address:School of Biology, Institute for Research on Environment and Sustainability, Devonshire Building, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, United Kingdom.

Present address: Molecular Mycology Laboratory, Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, ICPMR, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia.