-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rita Kleemann, Rainer U. Meckenstock, Anaerobic naphthalene degradation by Gram-positive, iron-reducing bacteria, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, Volume 78, Issue 3, December 2011, Pages 488–496, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01193.x

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

An anaerobic naphthalene-degrading culture (N49) was enriched with ferric iron as electron acceptor. A closed electron balance indicated the total oxidation of naphthalene to CO2. In all growing cultures, the concentration of the presumed central metabolite of naphthalene degradation, 2-naphthoic acid, increased concomitantly with growth. The first metabolite of anaerobic methylnaphthalene degradation, naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid, was not identified in culture supernatants, which does not support a methylation to methylnaphthalene as the initial activation reaction of naphthalene, but rather a carboxylation, as proposed for other naphthalene-degrading cultures. Substrate utilization tests revealed that the culture was able to grow on 1-methyl-naphthalene, 2-methyl-naphthalene, 1-naphthoic acid or 2-naphthoic acid, whereas it did not grow on 1-naphthol, 2-naphthol, anthracene, phenanthrene, indane and indene. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses revealed that the microbial community of the culture was dominated by one bacterial microorganism, which was closely related (99% 16S sequence similarity) to the major organism in the iron-reducing, benzene-degrading enrichment culture BF [ISME J (2007) 1: 643; Int J Syst Evol Microbiol (2010) 60: 686]. The phylogenetic classification supports a new candidate species and genus of Gram-positive spore-forming iron-reducers that can degrade non-substituted aromatic hydrocarbons. It furthermore indicates that Gram-positive microorganisms might also play an important role in anaerobic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degradation.

Introduction

During the last decades, most manufactured gas plants were closed, leaving behind large bodies of tar oil, consisting mainly of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and heterocyclic compounds. A major constituent of tar oil is naphthalene (up to 10%), which is often taken as a model compound for PAH degradation. Naphthalene is also an important constituent of crude oil and can be derived from the combustion of wood or tobacco. Naphthalene is poorly soluble in water (250 μmol L−1 at 20 °C) and has a high chemical stability due to the aromatic ring system. Both factors lead to a low bioavailability and a persistence of naphthalene in the environment. Anaerobic microbial degradation makes up an important part of the natural attenuation of aromatic hydrocarbons in contaminated aquifers (Christensen et al., ; Meckenstock et al., ). However, only a few sulfate-reducing microorganisms able to degrade PAHs in the absence of molecular oxygen have been identified in enrichments and pure cultures (Zhang & Young, ; Galushko et al., ; Meckenstock et al., ; Davidova et al., ; Musat et al., ). The strains involved were shown to be members of the Desulfobacteriaceae within the Deltaproteobacteria. Anaerobic PAH degradation with nitrate as electron acceptor has been reported, but organisms could not sustainably be enriched (Mihelcic & Luthy, ; Rockne & Strand, ; Eriksson et al., ).

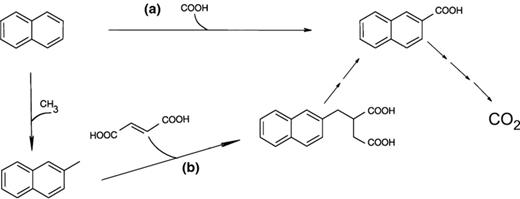

The initial biochemical activation reaction for naphthalene has still not been conclusively elucidated but two different pathways have been proposed (Fig. 1). One possible mechanism is a carboxylation in position 2, yielding 2-naphthoic acid. The latter can be further activated by co-enzyme-A ligation and subsequent ring reduction by naphthoyl-CoA reductase, similar to the benzoyl-CoA reductase pathway (Boll et al., ; Raulf, ). Experimental evidence for carboxylation was given by Zhang & Young (), Meckenstock et al. () and Bergmann et al. (, b). On the other hand, methylation of naphthalene to 2-methyl-naphthalene has also been proposed (Safinowski & Meckenstock, ). The produced 2-methyl-naphthalene should be degraded by the known methylnaphthalene degradation pathway, which consists of an addition of fumarate to the methyl group producing naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and a subsequent beta-oxidation to 2-naphthoic acid (Annweiler et al., ; Safinowski & Meckenstock, ). Methylation was excluded for the sulfate-reducing strains NaphS2, NaphS3 and NaphS6 (Musat et al., ).

Two initial reaction mechanisms proposed for the anaerobic degradation of naphthalene. (a) Carboxylation of naphthalene to 2-naphthoic acid. (b) Methylation to 2-methylnaphthalene. An addition of fumarate would follow here and produce the compound 2-naphthylmethylsuccinic acid, which is then further transformed into 2-naphthoic acid. In both cases, 2-naphthoic acid is oxidized to CO2.

Although ferric iron is an important and highly abundant electron acceptor in anoxic aquifers, PAH-degradation with ferric iron as terminal electron acceptor has only been described with sediment incubations (Anderson & Lovley, ). However, microorganisms belonging to the genera Geobacter, Desulfitobacterium, Georgfuchsia, and the family Peptococcaceae have been reported to be involved in the degradation of other aromatic compounds such as toluene or xylene, with iron as electron acceptor (Prakash et al.; Lovley et al., ; Christiansen & Ahring, ; Coates et al., , ; Wiegel et al., ; Kunapuli et al., , ; Abu Laban et al., ; Weelink et al., ).

Here, we present a new Fe(III)-reducing enrichment culture that grows with the PAH naphthalene as sole electron source. The culture was enriched from a contaminated aquifer of a former gas works site. Analyses of metabolites, substrate utilization and microbial communities were performed to identify the pathway of anaerobic naphthalene degradation and the microorganism involved.

Materials and methods

Culture and growth conditions

Culture N49 was enriched from a former manufactured gas plant site (Testfeld Süd) in Stuttgart, Germany, an aquifer shown to be contaminated with tar oil. Sediment from the bottom of a monitoring well was taken as inoculum (for more information about the site see Herfort et al., ; Bockelmann et al., ; Zamfirescu & Grathwohl, ; Griebler et al., ). Culture N49 was grown under standard anoxic conditions in the dark at 30 °C. The growth medium consisted of 1.0 g L−1 NaCl, 0.4 g L−1 MgCl2·6H2O, 0.2 g L−1 KH2PO4, 0.25 g L−1 NH4Cl, 0.5 g L−1 KCl, 0.15 g L−1 CaCl2·2H2O, trace elements (SL10), vitamins as well as a selenite and tungsten solution (Widdel & Pfennig, ; Widdel et al., ). FeCl2 was added to a final concentration of 3 mM as a reducing agent and to scavenge produced sulfide. The medium was buffered with 30 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.0). Bottles were flushed with a mixture of N2/CO2 (80/20), and closed with butyl rubber stoppers. The adsorber resin Amberlite® XAD7HP was added at a final concentration of 6 g L−1 to ensure a constant and low concentration of naphthalene within the medium. Medium bottles were shaken for 2 weeks in the dark to let the naphthalene adsorb to the resin before inoculation. If not otherwise mentioned, ferrihydrite was used as an electron acceptor and added to a final concentration of 50 mM (Lovley & Phillips, ). For a better accessibility of the electron acceptor, 243 μmol L−1 2,6-anthraquinone-disulfonate was added. All substrates except methanol (10 mM) were added in 2-mM concentrations. Alternative electron acceptors were added in slight excess according to the stoichiometric ratios. Elemental sulfur was added as powder. Grown cultures served as inoculum, which was transferred into fresh media in a 1 : 10 ratio using a sterile syringe and standard anaerobic techniques. For pasteurization, 10 mL of a grown culture was heated to 80 °C for 10 min in a closed reagent vial and used as inoculum.

Fe(II)-determination

Iron concentrations were determined with the ferrozine assay (Stookey, ). At each sample point, 0.1 mL was taken from the culture bottle, mixed with 0.9 mL 1 M HCl. Samples were shaken for 24 h at 25 000 g. Aliquots of 0.1-mL were then diluted in 1 : 10 ratio with ferrozine and incubated for 5 min. The absorbance at 560 nm was determined in a Wallac 1420 Victor3 micro-plate reader (Perkin Elmer, MA).

Determination of bacterial biomass

Bacterial biomass was monitored with an A-LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Nucleic acid stain 1× SYBR® Green I (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was diluted 1 : 30 000 in sterile filtered phosphate-buffered saline (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM KH2PO4) and was used to stain bacterial cells. Reference beads were used as internal standard (TrueCount™; Becton Dickinson Bioscience). Cells were fixed in 2.4% paraformaldehyde, stained with SYBR® Green for 10 min in the dark and counted at a wavelength of 510 nm.

DNA extraction

Culture bottles (approximately 45 mL) were harvested by centrifugation for 20 min at 4000 g and 4 °C (Thermo Megafuge 1.0R; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The cell pellets also contained the iron phase and were used for DNA extraction using the FastDNA spin kit for soil (MP Biomedicals, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

16S PCR amplification

All PCR amplifications were performed in a mastercycler ep gradient (Eppendorf, Hamburg) using the standard thermal profile [5 min initial denaturation (94 °C), 25–30 cycles of amplification (30 s/94 °C, 30 s/52 °C, 60 s/70 °C) and 5 min of terminal extension (70 °C)]. All standard PCR reaction mixes were prepared as described previously (Winderl et al., ). PCR amplicons were purified using MinElute PCR Purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Analysis of the microbial community

PCR for terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) was performed with 16S rRNA gene primer pairs and Ba27f(-FAM)/907r (Weisburg et al., ; Muyzer et al., ). Amplicons were digested by using restriction enzyme MspI (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Digested amplicons were desalted using DyeEx Spin kit columns (Qiagen) and size-separated on an ABI 3730 DNA analyzer as described in Lueders et al. ().

Quantitative PCR

Bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified using a MX3000P qPCR cycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) following the protocol described in Kunapuli et al. ().

Cloning and sequencing

For cloning and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes, purified DNA was amplified with primer pair Ba27f/Ba1492r (Weisburg et al., ). Amplicons were then cloned using the pGEM-T vector system, sequenced on an ABI 3730 sequencer, and the resulting data were assembled to contigs as described previously (Winderl et al., ). The blastn search tool (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) was used to identify the resulting sequences and, for further phylogenetic analyses, the respective sequences were fed into the arb 16S rRNA database (Ludwig et al., ). Using the methods implemented in arb (distance matrix, maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic treeing) a phylogenetic dendrogram was constructed to visualize phylogenetic relations. All 16S rRNA gene clone sequences from this study were deposited with GenBank under the accession nos. JF820824–JF820825.

Detection of metabolites

For metabolite analysis, 1-mL of culture was taken and centrifuged at 25 000 g for 10 min. A 150-μL aliquot of the resulting supernatant was transferred into small GC glass vials with a 200-μL insert. Metabolite analysis was carried out by LC/MS/MS on an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system coupled to an Applied Biosystems Q-Trap mass spectrometer equipped with a TurboSpray ionization source. Samples of 50 μL were injected to a LiChroCART® 125-2 Purospher® STAR RP-18e (5 μm) HPLC cartridge (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The column oven was set to 35 °C. A gradient of 25–40% acetonitrile in 0.1% acetic acid over 25 min at a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1 was applied. The sample was infused into the mass spectrometer via multiple reaction monitoring in negative mode and an entrance potential of −8 V. The declustering potential was set to −63 V and the collision energy was adjusted to −35 V.

Determination of CO2 production from 13C-naphthalene

The amount of naphthalene consumed was taken as equal to the accumulated 13CO2 at the end of the experiment because only one carbon atom of naphthalene was labeled.

Results

Growth properties of the enrichment culture N49

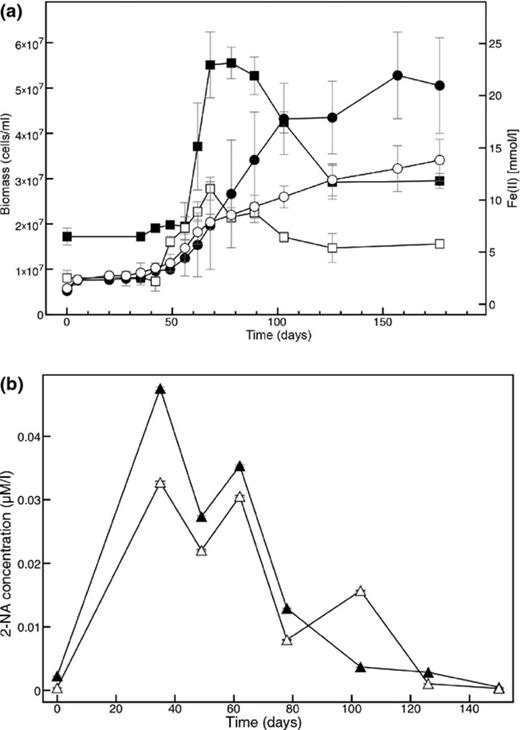

No decrease of naphthalene or increase of Fe(II) could be detected in the autoclaved controls or in the controls without electron acceptor. The turnover of naphthalene was coupled to growth as depicted by the increasing cell numbers (Fig. 2a). Culture N49 also grew after pasteurization, indicating that the organisms responsible for naphthalene degradation produce spores. Spores were also observed in microscopic analysis, although it could not be proven that the respective organisms are identical to the naphthalene degraders because the culture was not pure after pasteurization (data not shown).

Growth of culture N49 with 13C-naphthalene as electron and carbon source and ferrihydrite as electron acceptor (a). Filled symbols, untreated cultures; open symbols, pasteurized cultures; squares, biomass; circles, Fe(II)-concentration. Error bars depict standard deviations of three replicate incubations. (b) 2-Naphthoic acid (2-NA) concentrations during growth of untreated (filled triangles) and pasteurized N49 cultures (open triangles).

Metabolites produced during growth on naphthalene

Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) analysis of culture supernatants revealed two different metabolites with the corresponding masses of 144/116 (naphthol) and 172/128 (2-naphthoic acid). Naphthol was found in all experimental set-ups, even in sterile control bottles, and the concentrations did not correlate with growth (data not shown). In contrast, 2-naphthoic acid (2-NA) was found only in bottles that showed microbial growth. Concomitant with increasing biomass, 2-naphthoic acid concentrations increased and decreased in the stationary phase, indicating consumption (Fig. 2b).

Electron donors and acceptors utilized

Different PAHs as well as non-aromatic compounds were tested as alternative carbon sources for N49 with ferrihydrite as electron acceptor. The culture was able to grow with 1-methylnaphthalene, 2-methylnaphthalene, 1-naphthoic acid and 2-naphthoic acid. The microbial community composition remained the same for all substrates, indicating that the same organisms utilized the substrates. No growth was observed on 1-naphthol, 2-naphthol, anthracene, phenanthrene, indane or indene. Furthermore, sulfate, elemental sulfur (S0), and nitrate were tested as alternative electron acceptors for N49. However, only S0 led to a measurable increase in biomass (Table 1).

Tested alternative substrates and electron acceptors for the enrichment culture N49

| Trait | N49 | Major TRF observed (bp) |

| Naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 1-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 1-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthol | − | − |

| 1-Naphthol | − | − |

| Anthracene | − | − |

| Phenanthrene | − | − |

| Indane | − | − |

| Indene | − | − |

| S0 | + | − |

| Sulfate | − | − |

| Nitrate | − | − |

| Trait | N49 | Major TRF observed (bp) |

| Naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 1-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 1-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthol | − | − |

| 1-Naphthol | − | − |

| Anthracene | − | − |

| Phenanthrene | − | − |

| Indane | − | − |

| Indene | − | − |

| S0 | + | − |

| Sulfate | − | − |

| Nitrate | − | − |

Tested alternative substrates and electron acceptors for the enrichment culture N49

| Trait | N49 | Major TRF observed (bp) |

| Naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 1-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 1-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthol | − | − |

| 1-Naphthol | − | − |

| Anthracene | − | − |

| Phenanthrene | − | − |

| Indane | − | − |

| Indene | − | − |

| S0 | + | − |

| Sulfate | − | − |

| Nitrate | − | − |

| Trait | N49 | Major TRF observed (bp) |

| Naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 1-Methyl naphthalene | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 1-Naphthoic acid | + | 287 |

| 2-Naphthol | − | − |

| 1-Naphthol | − | − |

| Anthracene | − | − |

| Phenanthrene | − | − |

| Indane | − | − |

| Indene | − | − |

| S0 | + | − |

| Sulfate | − | − |

| Nitrate | − | − |

Analysis of the microbial community composition of culture N49

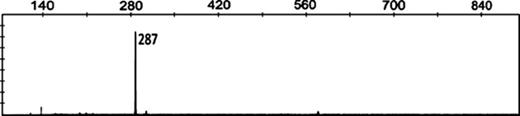

To identify the microorganisms involved in naphthalene degradation of the enrichment culture N49, T-RFLP and comparative sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA genes of bacteria were performed. The electropherogram of cells grown in naphthalene showed a single dominant bacterial TRF of 287 bp (Fig. 3) indicating that the naphthalene-degrading culture is mainly composed of one type of microorganism. T-RFLP analyses of liquid and solid phase of the cultures were identical (data not shown). To identify the dominant microorganism in the culture, 16S rRNA gene PCR amplicons were cloned and sequenced. Only one dominant type of sequence was present in each bacterial (n = 85) rRNA gene. ARB analysis revealed that the closest phylogenetic relative (≥ 99% 16S sequence similarity) was the dominant organism of the iron-reducing, benzene-degrading culture BF (Fig. 4) (Kunapuli et al., , ). In culture BF, the Gram-positive microorganism constituted more than 90% of the microbial community and was responsible for the degradation of benzene. The next cultivated and described relative in the data bank was Thermincola carboxydiphila within the Gram-positive Peptococcaceae with 92% sequence similarity (Sokolova et al., ).

Electropherogram of a T-RFLP analysis of culture N49 grown on naphthalene as sole carbon source. Numbers give the length of the TRF in base pairs.

![Phylogenetic dendrogram comprising clones from culture N49 designed with the arb software (using the Fitch algorithm implemented in arb). The scale bar represents 0.10 changes per nucleotide. [Correction added after online publication 21 October 2011: Previous figure replaced due to an incorrect version of the phylogenetic tree].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/femsec/78/3/10.1111_j.1574-6941.2011.01193.x/1/m_fem1193-fig-0004.jpeg?Expires=1749894755&Signature=UEds95GhqdS5Top4znV8jVmt5efpmTbCZAyFj3xWHsRTa2h~U2DoVSo3exjbIL2cZUX8zhGbHj7vKTgyUxNQ4Bvte1oki7ouCduSCJTwDTug9GpL8BVUmWMVAU6YpZdCTOrEV8euMMVmu6BYSNmEum2WFEXHQoNRoSpmyBnOp6~xaTzhAlDxY9HhThUjq~I0LxYUqZd3G4sQTzaSj~jlD8noJsKVy50AKdPKhLZ8i55xeryeywX53gZPYcR40cY6keWIplbVrqoMTqNuIeTvArCHvfZG1UiH~bHTz7Qfw6iRB4WlJiVRx~tT0OR2TtJ~CvdC2xCIuzBxOA8yWMz8NQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Phylogenetic dendrogram comprising clones from culture N49 designed with the arb software (using the Fitch algorithm implemented in arb). The scale bar represents 0.10 changes per nucleotide. [Correction added after online publication 21 October 2011: Previous figure replaced due to an incorrect version of the phylogenetic tree].

Discussion

In the current study, we present an anaerobic, iron-reducing enrichment culture that degrades naphthalene as sole electron and carbon source.

Key microbial members of enrichment culture N49

Based on T-RFLP and 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses and the results of the quantitative PCR, the enrichment consisted mainly of bacteria belonging to the family Peptococcaceae within the phylum Firmicutes. The closest relative in the data bank (≥ 99% 16S sequence similarity) was the dominant benzene-degrading organism from the iron-reducing enrichment culture BF (Kunapuli et al., , ). Considering the high phylogenetic similarity (99%) of the major key players in cultures N49 and BF, which is beyond the generally accepted 16S sequence similarity of 97% for the species level, we propose that the naphthalene degrader N49 and the benzene degrader BF depict two different strains of an iron-reducing candidate species that is specialized for the degradation of non-substituted aromatic hydrocarbons. Considering the close phylogenetic proximity of the two key players in N49 and BF it would be interesting to know whether N49 was able to grow on mono aromatic hydrocarbons. However, this has not been tested yet.

The nearest cultivated and described relative in the culture collections (92% 16S sequence similarity) is the organism T. carboxydiphila, which was isolated from a hot spring in the Baikal Lake region (Sokolova et al., ). However, the phylogenetic distance of N49 and BF to the genus Thermincola is larger than the commonly observed 16S sequence similarity within one genus. The two organisms N49 and BF might therefore constitute a novel species within a novel, yet undescribed, candidate genus. The discovery of strains N49 and BF supports recent findings that Gram-positive organisms may play a much larger role in the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons than anticipated before. The vast majority of anaerobic aromatic hydrocarbon degraders isolated so far belong to the Beta- and Deltaproteobacteria. Most of the strict anaerobes are sulfate reducers of the genus Desulfobacterium (Galushko et al., ; Musat et al., ) and a few Geobacteraceae (Lovley et al., ; Coates et al., ; Kunapuli et al., ) or the new genus Georgfuchsia within the Betaproteobacteria (Weelink et al., ). The lately isolated Gram-positive aromatics degraders belong to such different genera as Desulfitobacterium (Kunapuli et al., ), Desulfotomaculum (Tasaki et al., ; Morasch et al., ) and the family of the Peptococcaceae (Kunapuli et al., ). As revealed by the pasteurization test, strain N49 is spore-forming, which is not uncommon within the Gram-positive organisms of the Peptococcaceae. We speculate that spore formation may constitute an important physiological advantage in contaminated aquifers. Recent studies revealed that aquifers are not as static habitats as previously anticipated and surprisingly strong spatial fluctuations of contaminant plumes can occur (Anneser et al., , ; Jobelius et al., ). As most of the biomass is attached to the sediments it could be that the environmental conditions for microbes change drastically, exposing them to hostile conditions, e.g. molecular oxygen, high sulfide concentrations or high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons. Spore formation would allow degrader populations to survive such periods and proceed with growth when the geochemical parameters return to more suitable conditions.

Dissimilatory iron reduction is found in many phylogenetic groups of bacteria or archaea (Weber et al., ). Usually, these organisms can reduce different iron minerals, and basically every iron-reducing microorganism can reduce humic substances or analogs such as AQDS. Although there are slight variations between organisms, the general principle of the respiratory chain seams to be similar and the organisms are termed metal-reducing. We did not specifically test what iron minerals or quinone analogs culture N49 could utilize but always added small amounts of AQDS to enhance electron shuttling. The reduction rates for AQDS or pure ferric iron might therefore differ substantially for culture N49.

Pathway of anaerobic naphthalene degradation

Several studies have shown that the central intermediate 2-naphthoic acid accumulated in growth media with naphthalene as carbon source (Zhang & Young, ; Meckenstock et al., ; Zhang et al., ). Experiments with13C-bicarbonate-buffered medium showed that the 13C-label was incorporated into the carboxyl group of the metabolite 2-naphthoic acid, which suggests that carboxylation of naphthalene is the initial reaction mechanism (Zhang & Young, ; Meckenstock et al., ). However, one has to admit that metabolites accumulate over long cultivation times and are detected in trace amounts only. They can only be taken as hints for putative degradation pathways. In our experiments, LC/MS/MS analysis revealed 2-naphthoic acid as intermediate with increasing concentrations during growth and a decline when cultures entered the stationary phase. Furthermore, substrate utilization tests showed that culture N49 was able to grow on 2-naphthoic acid. Therefore, it is likely that 2-naphthoic acid is a central metabolite in the naphthalene degradation pathway of strain N49. Methylation was also discussed as an initial reaction mechanism for naphthalene activation (Safinowski & Meckenstock, ). The authors performed growth experiments with deuterated naphthalene as sole carbon source and found ring-deuterated metabolites such as naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid. These compounds are known to be key intermediates of the 2-methyl-naphthalene degradation pathway (Annweiler et al., , ; Selesi et al., ). Our culture was also tested for naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid but none of these metabolites could be detected, although the culture could grow with 2-methylnaphthalene. Culture N49 can also grow with 1-methylnaphthalene. As the two currently known anaerobic degradation pathways of naphthalene and 2-methylnaphthalene proceed via 2-naphthoic acid it will be biochemically very interesting to analyze how the organism activates and degrades 1-methylnaphthalene. However, metabolite analysis of a culture grown in 1-methylnaphththalene has not been performed so far. Alternatives are a fumarate addition reaction, as in the well studied 2-methylnaphthalene degradation pathway of strain N47, or carboxylation to 1-methyl-2-naphthoic acid, similar to naphthalene degradation (Safinowski & Meckenstock, ; Selesi et al., ).

The current enrichment culture N49 indicates that anaerobic PAH-degradation can also be performed by iron-reducing microorganisms. This furthermore highlights that Gram-positive microorganisms might play a more important role in anaerobic aromatics degradation than anticipated previously.

References

Author notes

Editor: Alfons Stams