-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Chiara Dello Iacono, Sol P Juárez, Mikolaj Stanek, Duration of residence and offspring birth weight among foreign-born mothers in Spain: a cross-sectional study, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 34, Issue 3, June 2024, Pages 524–529, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckae011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Duration of residence has been used to monitor changes in the health of a foreign-born population in a destination country. This study assesses whether the mother’s duration of residence influences the relationship between maternal origin and birth weight.

We conducted a cross-sectional study using Spanish census microdata (2011) linked to Vital Statistics (2011–15). Linear and multinomial logistic regression models were used to estimate birth weight differences between children born to foreign-born mothers by duration of residence and those born to natives. Maternal countries of origin were classified according to the Human Development Index (HDI).

Our findings revealed significant differences in birth weight of 109 683 births from both foreign- and native-born mothers. Overall, in descriptive statistics, compared with Spanish mothers, foreign-born mothers gave birth more frequently to high-birth weight (HBW) newborns (8.4% vs. 5.3%, respectively) and less frequently to low-birth weight (LBW) newborns (4.8% vs. 5.1%). According to the model’s estimations, the risk of giving birth to HBW babies remains relatively high in foreign-born mothers. Especially, mothers from very high-HDI countries experienced changes in the RRR of HBW (1.59–1.28) and LBW (0.58–0.89) after spending over 10 years in Spain.

Foreign-born mothers residing in Spain are at increased risk of delivering a HBW child regardless of their duration of residence. In fact, given the long-term health consequences associated with HBW, our results highlight the need to improve prenatal care in the foreign-born population.

Introduction

Evidence is growing on how health disparities between population subgroups emerge and are reproduced over time.1 Most study results show that immigrants have better or at least better-than-expected health than native-born residents of their host countries, given their socioeconomic characteristics (i.e. the phenomenon known as the healthy migrant paradox).2 However, this health advantage declines with increasing duration of residence in the host country and is presumably affected by unhealthy cultural changes (i.e. the acculturation paradox).3–5

Because birth weight depends on maternal behavior and health status, it provides valuable information about maternal reproductive health.6 Birth weight is also a crucial indicator of the child’s health because it is strongly associated with newborn survival and health status throughout life.7 Infants who are born with low birth weight (LBW, <2500 g) and very LBW (<1500 g) are mostly at immediate higher risk of mortality and survivors are at greater risk of infant morbidity, as well as long-term morbidity including hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.8 Furthermore, learning difficulties, hyperactivity,9 and limited socioeconomic status,10 later in life were observed among LBW and very LBW infants. Conversely, children born with a high birth weight (HBW, >4000 g) are more likely than others to be overweight or obese and to have chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, during childhood and adulthood.11

Recently, duration of residence has been used to monitor changes in population health. In the specific case of immigrants, duration of residence can provide information on the extent to which the situation in the destination country may influence the mother’s initial health condition.12 To date, some studies that have focused on gestational age (mainly preterm births)1 and birth weight13–16 have examined changes in foreign mothers’ reproductive health as a function of duration of residence. However, when interpreting the association between birth weight and duration of residence, inequalities in origin have rarely been considered.17

Examining the trajectories of perinatal health and childbirth outcomes among foreign-born mothers in the host country is challenging. The accessibility of healthcare services for the immigrant population remains a matter of critical importance, bearing substantial implications for overall health and perinatal well-being. In Spain, despite limited literature on access to healthcare services, particularly those pertaining to prenatal care, it is evident that immigrant women utilize preventive services less frequently than their Spanish counterparts.18 This disparity can be attributed to administrative hurdles in accessing these services, cultural factors, language barriers, religious considerations and the demands of extensive work hours.18 In fact, it has been observed that enhanced prenatal care can mitigate the risk of low-birth-weight infants.19 To date, examining the association between duration of residence and birth weight in Spain has not been feasible because of the lack of information in the Spanish Vital Statistics regarding duration of residence. Migration and perinatal health studies have found that foreign-born women are less likely to give birth to LBW children than native-born women.20 However, when both LBW and HBW indicators were analyzed, foreign mothers were more likely to have HBW children and at lower risk of LBW.21,22 This study aims to fill the above-mentioned knowledge gap by examining whether the association between country of origin (considering the level of Human Development) and birth weight outcomes (LBW and HBW) is modified by the mother’s duration of residence in Spain. Given that no prior relevant studies exist in Spain; the country represents a unique context for research on this topic.

Methods

Study population and data sources

We used a novel database provided by the Spanish National Statistical Office that links people who appear in the 2011 Census with mothers who have given birth in the country between January 2011 and December 2015 as recorded in the Vital Statistics (Movimiento Natural de la Población). Specifically, the data on births and mothers collected by Vital Statistics were linked to the 2011 Census data on personal maternal characteristics, including births, sex, age, marital status, country of origin, education level, employment status, living conditions and migration status. The dataset represents a sample of ∼10% of the Spanish population.

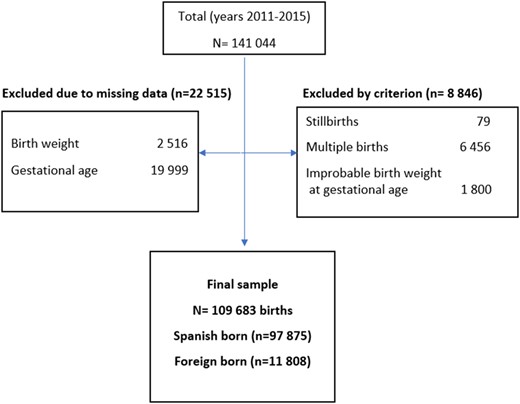

As the study population, we considered women who gave birth during the 2011–15 period (12–54 years old; N = 140 533). We excluded stillbirths (n = 79), multiple births (n = 6456) and births associated with data entry errors that resulted in biologically improbable birth weights for the associated gestational age (n = 1800). We further excluded entries with missing birth weights (n = 2516) and gestational ages (n = 19 999). Our final study population consisted of 109 683 births. Of these, 89.2% of infants were born to natives and 10.8% to foreign-born mothers (figure 1).

Outcome and covariates

We defined birth weight in grams as the main outcome and categorized birth weight into three groups for some analyses: LBW (≤2500 g), normal birth weight (2500–3999 g) and HBW (≥4000 g). Our main exposure was the maternal country of birth classified according to the human development index (HDI), The HDI is a measure developed by the United Nations Development Programme that takes into account gross national income per capita, education (i.e. the highest average level of education attained) and life expectancy at birth.23 Duration of residence was calculated by subtracting the year of immigration from the date of birth and was then divided into three groups: ≤4, 5–9, and ≥10 years.

In addition, we included several covariates, such as the year of birth (2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015), maternal age (≤24, 25–34, and ≥35 years), maternal education (primary, secondary and tertiary) and family situation (married, cohabiting and single). The Spanish census distinguishes between family household types. The household structure variable was used rather than marital status to determine the family situation because marital status is decreasingly informative about a mother’s living situation and, given its dynamic nature, cannot be the only demographic variable considered when analyzing a mother’s family situation. Birth characteristics, such as newborn sex, birth order (1, 2, ≥3) and gestational age (<37, 37–41, and ≥42 weeks) were considered.

Statistical analyses

First, using Spanish-born mothers as the reference group, we used adjusted linear regression models stratified by duration of residence to examine whether the maternal duration of residence in Spain modified the association between birth weight and maternal origin. Second, in order to assess whether the mean birth weight falls within a typical range or is linked to unfavorable health outcomes multinomial logistic regression models were estimated with Spanish-born mothers as the reference group.

We ran two sets of models. Model 1 presented the overall association between the HDI categories (compared with Spain) and LBW or HBW (compared with normal birth weight). Model 2 assessed differences in LBW and HBW compared with normal weight among mothers from countries with varying HDIs stratified by duration of residence. The effect estimates were relative risk ratios (RRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). The models were adjusted for confounding factors, such as newborn sex, birth order, gestational age (linear) and maternal age. The study was approved by the Confidentiality Committee of the Spanish National Statistical Office.

Sensitivity analyses

Additional model estimations considering three different classifications of duration of residence used in the reference literature were estimated. The first classification categorizes the duration of residence into four groups: 0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and ≥15.13,14 The second categorizes the duration of residence into four groups: 0–3, 4–12 and ≥13.24 The third categorizes the duration of residence into two groups: <10 and ≥10 years25 (see Supplementary file). Furthermore, we calculated the number of excluded births in the explanatory variables to assess potential study bias (see Supplementary file). All analyses were performed using Stata version 17 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. We included 109 683 births to foreign- and native-born mothers that had complete information. Overall, foreign mothers more frequently gave birth to HBW newborns (8.4% vs. 5.3%) and less frequently to LBW newborns (4.8% vs. 5.1%) than did Spanish-born mothers. Foreign-born mothers were more likely to be young (11.8% vs. 4.7%), have more than one child (16.2% vs. 7.1%) and have a low level of education (39.2% vs. 25.1%) than Spanish-born mothers. Moreover, foreign mothers had a higher unemployment rate than native mothers (56.8% vs. 31.2%). Regarding their family situations, foreign-born women, like their native counterparts, typically reside with their partners (62.5% vs. 76%). Notably, they also display a higher tendency to cohabit with family members in comparison to Spanish-natives (29.6% vs. 11.4%).

| . | . | . | Spanish-born . | Foreign-born . | By mother's duration of residence in Spain . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . |

| N | 97 875 | 11 808 | 1 783 | 4 730 | 5 295 | ||

| Variable | Categories | (89.2%) | (10.8%) | (15.1%) | (40.1%) | (44.8%) | |

| Birth weight (grams) | Mean | 3252 | 3330 | 3338 | 3345 | 3313 | |

| (SD) | 478 | 514 | 505 | 517 | 513 | ||

| ≤2500 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 5.3 | ||

| 2500–3999 | 89.5 | 86.8 | 87.5 | 86.5 | 86.7 | ||

| >4000 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 8 | 9 | 8 | ||

| P-value =0.000 | |||||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | Mean | 39.18 | 39.12 | 39.15 | 39.14 | 39.10 | |

| (SD) | (1.65) | (1.79) | (1.84) | (1.81) | (1.75) | ||

| <37 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6 | 5.1 | 5.8 | ||

| 37–41 | 93.3 | 91.9 | 91.5 | 92.1 | 92 | ||

| ≥42 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Newborn’s sex | Male | 51.7 | 52.4 | 53.1 | 52.3 | 52.2 | |

| Female | 48.3 | 47.6 | 46.9 | 47.7 | 47.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Birth order | 1 | 52.9 | 45.6 | 56.3 | 44.5 | 43 | |

| 2 | 40 | 38.2 | 33 | 39.1 | 39.2 | ||

| ≥3 | 7.1 | 16.2 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 17.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal age | <25 | 4.7 | 11.8 | 18.6 | 12.5 | 8.9 | |

| 25–34 | 51.7 | 53.4 | 59.1 | 59.9 | 45.7 | ||

| ≥35 | 43.7 | 34.8 | 22.3 | 27.6 | 45.5 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal education | Low | 25.1 | 39.2 | 39.1 | 40.6 | 37.9 | |

| Medium | 31.6 | 33.8 | 27.8 | 33.7 | 36 | ||

| High | 43.2 | 27 | 33.1 | 25.7 | 26.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal family status | Married | 76 | 62.5 | 61.1 | 61.1 | 64.2 | |

| Cohabit | 11.4 | 29.6 | 33.5 | 32.4 | 25.7 | ||

| Single | 12.6 | 7.9 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 10.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal employment | Yes | 68.8 | 43.2 | 26.3 | 40.2 | 51.6 | |

| No | 31.2 | 56.8 | 73.7 | 59.8 | 48.4 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| . | . | . | Spanish-born . | Foreign-born . | By mother's duration of residence in Spain . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . |

| N | 97 875 | 11 808 | 1 783 | 4 730 | 5 295 | ||

| Variable | Categories | (89.2%) | (10.8%) | (15.1%) | (40.1%) | (44.8%) | |

| Birth weight (grams) | Mean | 3252 | 3330 | 3338 | 3345 | 3313 | |

| (SD) | 478 | 514 | 505 | 517 | 513 | ||

| ≤2500 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 5.3 | ||

| 2500–3999 | 89.5 | 86.8 | 87.5 | 86.5 | 86.7 | ||

| >4000 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 8 | 9 | 8 | ||

| P-value =0.000 | |||||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | Mean | 39.18 | 39.12 | 39.15 | 39.14 | 39.10 | |

| (SD) | (1.65) | (1.79) | (1.84) | (1.81) | (1.75) | ||

| <37 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6 | 5.1 | 5.8 | ||

| 37–41 | 93.3 | 91.9 | 91.5 | 92.1 | 92 | ||

| ≥42 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Newborn’s sex | Male | 51.7 | 52.4 | 53.1 | 52.3 | 52.2 | |

| Female | 48.3 | 47.6 | 46.9 | 47.7 | 47.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Birth order | 1 | 52.9 | 45.6 | 56.3 | 44.5 | 43 | |

| 2 | 40 | 38.2 | 33 | 39.1 | 39.2 | ||

| ≥3 | 7.1 | 16.2 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 17.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal age | <25 | 4.7 | 11.8 | 18.6 | 12.5 | 8.9 | |

| 25–34 | 51.7 | 53.4 | 59.1 | 59.9 | 45.7 | ||

| ≥35 | 43.7 | 34.8 | 22.3 | 27.6 | 45.5 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal education | Low | 25.1 | 39.2 | 39.1 | 40.6 | 37.9 | |

| Medium | 31.6 | 33.8 | 27.8 | 33.7 | 36 | ||

| High | 43.2 | 27 | 33.1 | 25.7 | 26.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal family status | Married | 76 | 62.5 | 61.1 | 61.1 | 64.2 | |

| Cohabit | 11.4 | 29.6 | 33.5 | 32.4 | 25.7 | ||

| Single | 12.6 | 7.9 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 10.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal employment | Yes | 68.8 | 43.2 | 26.3 | 40.2 | 51.6 | |

| No | 31.2 | 56.8 | 73.7 | 59.8 | 48.4 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| . | . | . | Spanish-born . | Foreign-born . | By mother's duration of residence in Spain . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . |

| N | 97 875 | 11 808 | 1 783 | 4 730 | 5 295 | ||

| Variable | Categories | (89.2%) | (10.8%) | (15.1%) | (40.1%) | (44.8%) | |

| Birth weight (grams) | Mean | 3252 | 3330 | 3338 | 3345 | 3313 | |

| (SD) | 478 | 514 | 505 | 517 | 513 | ||

| ≤2500 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 5.3 | ||

| 2500–3999 | 89.5 | 86.8 | 87.5 | 86.5 | 86.7 | ||

| >4000 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 8 | 9 | 8 | ||

| P-value =0.000 | |||||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | Mean | 39.18 | 39.12 | 39.15 | 39.14 | 39.10 | |

| (SD) | (1.65) | (1.79) | (1.84) | (1.81) | (1.75) | ||

| <37 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6 | 5.1 | 5.8 | ||

| 37–41 | 93.3 | 91.9 | 91.5 | 92.1 | 92 | ||

| ≥42 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Newborn’s sex | Male | 51.7 | 52.4 | 53.1 | 52.3 | 52.2 | |

| Female | 48.3 | 47.6 | 46.9 | 47.7 | 47.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Birth order | 1 | 52.9 | 45.6 | 56.3 | 44.5 | 43 | |

| 2 | 40 | 38.2 | 33 | 39.1 | 39.2 | ||

| ≥3 | 7.1 | 16.2 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 17.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal age | <25 | 4.7 | 11.8 | 18.6 | 12.5 | 8.9 | |

| 25–34 | 51.7 | 53.4 | 59.1 | 59.9 | 45.7 | ||

| ≥35 | 43.7 | 34.8 | 22.3 | 27.6 | 45.5 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal education | Low | 25.1 | 39.2 | 39.1 | 40.6 | 37.9 | |

| Medium | 31.6 | 33.8 | 27.8 | 33.7 | 36 | ||

| High | 43.2 | 27 | 33.1 | 25.7 | 26.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal family status | Married | 76 | 62.5 | 61.1 | 61.1 | 64.2 | |

| Cohabit | 11.4 | 29.6 | 33.5 | 32.4 | 25.7 | ||

| Single | 12.6 | 7.9 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 10.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal employment | Yes | 68.8 | 43.2 | 26.3 | 40.2 | 51.6 | |

| No | 31.2 | 56.8 | 73.7 | 59.8 | 48.4 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| . | . | . | Spanish-born . | Foreign-born . | By mother's duration of residence in Spain . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . |

| N | 97 875 | 11 808 | 1 783 | 4 730 | 5 295 | ||

| Variable | Categories | (89.2%) | (10.8%) | (15.1%) | (40.1%) | (44.8%) | |

| Birth weight (grams) | Mean | 3252 | 3330 | 3338 | 3345 | 3313 | |

| (SD) | 478 | 514 | 505 | 517 | 513 | ||

| ≤2500 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 5.3 | ||

| 2500–3999 | 89.5 | 86.8 | 87.5 | 86.5 | 86.7 | ||

| >4000 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 8 | 9 | 8 | ||

| P-value =0.000 | |||||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | Mean | 39.18 | 39.12 | 39.15 | 39.14 | 39.10 | |

| (SD) | (1.65) | (1.79) | (1.84) | (1.81) | (1.75) | ||

| <37 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6 | 5.1 | 5.8 | ||

| 37–41 | 93.3 | 91.9 | 91.5 | 92.1 | 92 | ||

| ≥42 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Newborn’s sex | Male | 51.7 | 52.4 | 53.1 | 52.3 | 52.2 | |

| Female | 48.3 | 47.6 | 46.9 | 47.7 | 47.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Birth order | 1 | 52.9 | 45.6 | 56.3 | 44.5 | 43 | |

| 2 | 40 | 38.2 | 33 | 39.1 | 39.2 | ||

| ≥3 | 7.1 | 16.2 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 17.8 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal age | <25 | 4.7 | 11.8 | 18.6 | 12.5 | 8.9 | |

| 25–34 | 51.7 | 53.4 | 59.1 | 59.9 | 45.7 | ||

| ≥35 | 43.7 | 34.8 | 22.3 | 27.6 | 45.5 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal education | Low | 25.1 | 39.2 | 39.1 | 40.6 | 37.9 | |

| Medium | 31.6 | 33.8 | 27.8 | 33.7 | 36 | ||

| High | 43.2 | 27 | 33.1 | 25.7 | 26.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal family status | Married | 76 | 62.5 | 61.1 | 61.1 | 64.2 | |

| Cohabit | 11.4 | 29.6 | 33.5 | 32.4 | 25.7 | ||

| Single | 12.6 | 7.9 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 10.1 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

| Maternal employment | Yes | 68.8 | 43.2 | 26.3 | 40.2 | 51.6 | |

| No | 31.2 | 56.8 | 73.7 | 59.8 | 48.4 | ||

| P-value = 0.000 | |||||||

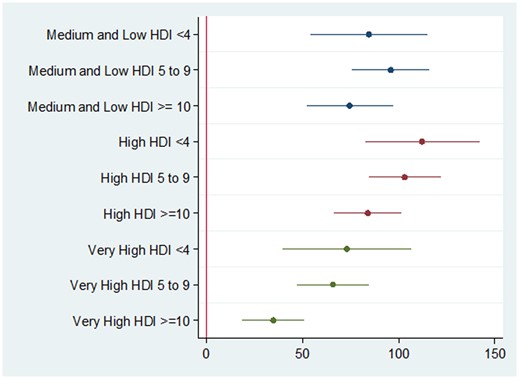

Figure 2 shows the beta coefficients with 95% CIs for the association between average birth weight and maternal origin by duration of residence, using Spanish-born mothers as a reference. Given that all point estimates were above the reference point (i.e. zero), foreign-born mothers were determined to have a higher likelihood of giving birth to heavy children than native-born mothers regardless of duration of residence. The pattern underlying the relationship between birth weight and duration of residence in Spain remains unclear. However, we observed a variation in the average birth weight of children born to mothers from very high-HDI countries who had spent 10 years or more in Spain. This group of mothers gave birth to infants with a lower average birth weight than those born to mothers who had resided in Spain for <10 years (β>10: 95% CI). The birth weight of these lighter-weight newborns nearly matches that of infants born to native Spanish mothers.

Beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals for the association between average birthweight and maternal origin (reference: Spanish-born) by duration of residence

Table 2 shows the adjusted RRRs with 95% CIs for LBW and HBW by maternal origin, using children born in Spain as a reference. Regardless of the maternal duration of residence, the results indicate significant differences in birth weight and reflect an overall higher prevalence of HBW among mothers from countries with varying levels of human development. Compared with Spanish mothers, mothers from countries with low and medium HDIs had a higher risk of giving birth to children with HBW (RRR = 1.74; 95% CI: 1.54–1.97) than mothers from countries with high (RRR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.4–1.79) and very high (RRR = 1.38; 95% CI: 1.22–1.55) HDIs. In contrast, among children born to mothers from countries with very high-HDI, changes in the RRR of HBW (1.59–1.28) and LBW (0.58–0.89) were observed when the mother had spent 10 years or more in the destination country.

Relative risk ratios (RRR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of low and high birth weight by maternal origin classified by the human development index (HDI) (reference: Spanish-born) and duration of residence

| . | N . | Overall effect . | Duration of residence . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . | |||

| . | . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . |

| Spanish-born (ref) | 97 875 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medium-Low HDI | 3 218 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.55; 0.88] | 0.60 | [0.35; 1.03] | 0.67 | [0.47; 0.96] | 0.79 | [0.54; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.74 | [1.54; 1.97] | 1.74 | [1.32; 2.31] | 1.78 | [1.49; 2.13] | 1.68 | [1.37; 2.06] | |

| High HDI | 4 172 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.57; 0.85] | 0.66 | [0.39; 1.10] | 0.56 | [0.40; 0.79] | 0.82 | [0.62; 1.08] | |

| HBW | 1.59 | [1.41; 1.79] | 1.25 | [0.90; 1.73] | 1.73 | [1.44; 2.08] | 1.57 | [1.32; 1.87] | |

| Very high HDI | 4 418 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.81 | [0.67; 0.97] | 0.58 | [0.34; 1.01] | 0.76 | [0.56; 1.03] | 0.89 | [0.70; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.38 | [1.22; 1.55] | 1.59 | [1.14; 2.22] | 1.44 | [1.19; 1.74] | 1.28 | [1.07; 1.52] | |

| . | N . | Overall effect . | Duration of residence . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . | |||

| . | . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . |

| Spanish-born (ref) | 97 875 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medium-Low HDI | 3 218 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.55; 0.88] | 0.60 | [0.35; 1.03] | 0.67 | [0.47; 0.96] | 0.79 | [0.54; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.74 | [1.54; 1.97] | 1.74 | [1.32; 2.31] | 1.78 | [1.49; 2.13] | 1.68 | [1.37; 2.06] | |

| High HDI | 4 172 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.57; 0.85] | 0.66 | [0.39; 1.10] | 0.56 | [0.40; 0.79] | 0.82 | [0.62; 1.08] | |

| HBW | 1.59 | [1.41; 1.79] | 1.25 | [0.90; 1.73] | 1.73 | [1.44; 2.08] | 1.57 | [1.32; 1.87] | |

| Very high HDI | 4 418 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.81 | [0.67; 0.97] | 0.58 | [0.34; 1.01] | 0.76 | [0.56; 1.03] | 0.89 | [0.70; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.38 | [1.22; 1.55] | 1.59 | [1.14; 2.22] | 1.44 | [1.19; 1.74] | 1.28 | [1.07; 1.52] | |

Notes: Results adjusted for newborn’s sex, birth order, gestational age and maternal age. Ref, reference category; RRR, relative risk ratios; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; LBW, low birth weight; HBW, high birth weight.

Relative risk ratios (RRR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of low and high birth weight by maternal origin classified by the human development index (HDI) (reference: Spanish-born) and duration of residence

| . | N . | Overall effect . | Duration of residence . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . | |||

| . | . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . |

| Spanish-born (ref) | 97 875 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medium-Low HDI | 3 218 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.55; 0.88] | 0.60 | [0.35; 1.03] | 0.67 | [0.47; 0.96] | 0.79 | [0.54; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.74 | [1.54; 1.97] | 1.74 | [1.32; 2.31] | 1.78 | [1.49; 2.13] | 1.68 | [1.37; 2.06] | |

| High HDI | 4 172 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.57; 0.85] | 0.66 | [0.39; 1.10] | 0.56 | [0.40; 0.79] | 0.82 | [0.62; 1.08] | |

| HBW | 1.59 | [1.41; 1.79] | 1.25 | [0.90; 1.73] | 1.73 | [1.44; 2.08] | 1.57 | [1.32; 1.87] | |

| Very high HDI | 4 418 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.81 | [0.67; 0.97] | 0.58 | [0.34; 1.01] | 0.76 | [0.56; 1.03] | 0.89 | [0.70; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.38 | [1.22; 1.55] | 1.59 | [1.14; 2.22] | 1.44 | [1.19; 1.74] | 1.28 | [1.07; 1.52] | |

| . | N . | Overall effect . | Duration of residence . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | <4 . | 5–9 . | ≥10 . | |||

| . | . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . | RRR . | 95% CI . |

| Spanish-born (ref) | 97 875 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medium-Low HDI | 3 218 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.55; 0.88] | 0.60 | [0.35; 1.03] | 0.67 | [0.47; 0.96] | 0.79 | [0.54; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.74 | [1.54; 1.97] | 1.74 | [1.32; 2.31] | 1.78 | [1.49; 2.13] | 1.68 | [1.37; 2.06] | |

| High HDI | 4 172 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.70 | [0.57; 0.85] | 0.66 | [0.39; 1.10] | 0.56 | [0.40; 0.79] | 0.82 | [0.62; 1.08] | |

| HBW | 1.59 | [1.41; 1.79] | 1.25 | [0.90; 1.73] | 1.73 | [1.44; 2.08] | 1.57 | [1.32; 1.87] | |

| Very high HDI | 4 418 | ||||||||

| LBW | 0.81 | [0.67; 0.97] | 0.58 | [0.34; 1.01] | 0.76 | [0.56; 1.03] | 0.89 | [0.70; 1.14] | |

| HBW | 1.38 | [1.22; 1.55] | 1.59 | [1.14; 2.22] | 1.44 | [1.19; 1.74] | 1.28 | [1.07; 1.52] | |

Notes: Results adjusted for newborn’s sex, birth order, gestational age and maternal age. Ref, reference category; RRR, relative risk ratios; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; LBW, low birth weight; HBW, high birth weight.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine whether the association between country of birth and birth weight is modified by the mother’s duration of residence in Spain. We observed two main findings. We acknowledge the inequalities in reproductive health—including perinatal outcomes—among mothers from different countries of origin. Regardless of duration of residence in Spain, foreign-born mothers from countries with varying levels of human development were more likely to give birth to heavier newborn infants on average than Spanish-born mothers. However, despite the significant variation in average birth weight by duration of residence, we did not observe an obvious association between foreign mothers’ duration of residence and average birth weight. We observed a high risk of HBW among infants born to mothers from countries with low and medium HDIs and a high risk of LBW among those born to mothers from countries with a very high HDI who had a longer duration of residence in Spain.

Consistent with previous studies conducted in Spain21,22 and other countries,26,27 our results suggest that foreign-born mothers are more likely to give birth to HBW babies compared with native-born women. HBW is associated with increased risks of being overweight in childhood and adulthood28 developing type 2 diabetes and related diseases, such as hypertension and metabolic syndrome.29 Previous epidemiological studies have focused primarily on clinical risk factors for HBW, including older maternal age, maternal obesity, gestational diabetes mellitus, prolonged gestation, smoking and glycosuria.11 However, foreign status30 has been observed to influence HBW outcomes, and certain groups31 are more likely to give birth to HBW babies than others.

Previous research is consistent with acculturation theory, suggesting a monotonic association between duration of residence and poor health. That is, the longer foreign-born mothers are in the host country, the worse their health status in general4 and their reproductive status in particular.24, 32 Specifically, duration of residence in the destination country is reported to have an impact on the HBW of children born to foreign mothers.16,32 However, we found no evidence of an association between worsening birth weight and duration of residence among foreign mothers.

Our results were inconsistent with those from cross-sectional studies conducted in the USA and Sweden. In contrast to American studies that indicated that the average birth weight decreased with duration of residence,13,14 our study did not indicate such a decrease. However, similar to the Swedish study,15 the variation in average birth weight that we observed by duration of residence played only a marginal role when examining the association between a foreign mother’s country of birth and birth weight.

Our study has important implications for understanding differences in reproductive health outcomes among foreign mothers compared with native-born in Spain. First, duration of residence has only a minor impact on the average birth weight. Our results are consistent with earlier findings, suggesting that differences in birth weight should be analyzed for corresponding adverse health outcomes.33,34 These birth weight outcomes may be related to the mother’s ethnicity or social status in early life.15

Second, tracking the health trajectory of immigrant mothers and noting differences in origin are challenging because it is not always possible to collect and publicly share data from multiple countries on mothers’ pre-migration reproductive health and living conditions.34 Moreover, the association between foreign-born status and reproductive health varies by migrant subgroup, status and country of origin or destination.17 Despite these challenges, the HDI—a composite indicator of life expectancy, education and gross national income per capita—allows a more complete overview of inequalities among mothers from different countries of origin. The persistent risk of LBW among mothers from medium- and low-HDI countries—such as countries in sub-Saharan and North Africa—confirms concerns raised in earlier research.19,21,35,36 In addition, the increasing rate of HBW among mothers from high- and very high-HDI countries—such as those in Europe and Latin America—suggests that inequalities between immigrant mothers are evident and that mothers are exposed to different risk factors regardless of their socioeconomic status.

Strengths and limitations

Considering our study’s strengths and limitations is important when interpreting the results. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Spain to examine the relationship between birth weight and duration of residence using the maternal condition in the origin country as a reference. The rich data source—the Spanish National Statistical Office, which linked the 2011 Census with the Spanish Vital Statistics for the 2011–15 period—enabled our assessment of the relationship between birth weight and duration of residence among foreign-born mothers.

In terms of limitations, first our data lacked a set of control variables that are important predictors of birth weight, such as maternal chronic conditions, nutritional status, infections, tobacco, alcohol or drug use and exposure to poor environmental conditions. This limitation arises from the fact that the birth registry does not include potentially relevant data on maternal health behaviors, health system utilization or health conditions.

Second, we have a relatively high proportion of missing values in our outcome variable. In this study, we observed missing birth weight is higher among mothers originating from countries characterized by a medium-low HDI, however, the proportion was irrespective of the duration of residence so we expect the results to be robust. Missing data can be attributed to several factors like the absence or inaccuracy of information originating from the Statistical Birth Certificate. This issue may reflect a particular challenge for foreign parents as they often contend with language barriers and the accessibility of requisite information needed to complete the essential documentation.37 Furthermore, it is essential to consider the quality of the imputation procedure undertaken by the Spanish National Statistical Office when rectifying values falling below the thresholds of human viability. In such instances, errors and discrepancies concerning birth weight and gestational week may potentially emerge.37

Third, when analyzing the effect of duration of residence on the association between maternal origin and reproductive health outcomes, we compared birth weight differences between mothers with differing durations of residence rather than evaluating their reproductive outcomes over time. We could not examine the likelihood of prior selection among mothers who chose to have a child soon after moving to Spain or among those who decided to stay longer in the country. Therefore, the effects of duration of residence on birth weight may have been suppressed by differential immigrant selectivity in reproductive health. That is, if healthier mothers gradually left, an increased risk of HBW may have been observed over time.

Another study limitation is that vital information in Spain is reported by parents and not cross-checked with hospital documents. Although we did not validate the information provided by the Spanish National Statistical Office, no evidence suggests that our comparison between immigrants and natives was affected.38

Conclusions

Public health implications and future research

Inequalities in health outcomes between foreign-born mothers and natives do not follow a consistent pattern. In Spain and elsewhere, variation in average birth weight depends not only on maternal origin but also on living conditions in the host country.1,17,34 Our findings suggest that the high risk of HBW among certain groups of foreign-born mothers compared with that among Spanish-born mothers is not improved by increased duration of residence. This finding could be attributable to the fact that health conditions, such as obesity and diabetes that affect the most immediate risk factors do not improve over time. Therefore, improving prenatal care in the foreign-born population is essential not only because it is an important means of promoting maternal and child health but also because prenatal care reduces risks associated with reproductive health.39

Further studies should identify the mechanisms underlying the low risk of LBW and high risk of HBW among the offspring of foreign-born mothers compared with those of native-born women in Spain. Our research can guide design interventions that address the inequalities presented in this study.

In conclusion, our study shows that regardless of the level of development of the country of birth, foreign-born mothers in Spain are at a higher risk of delivering HBW offspring than native-born mothers. This risk does not decrease with increasing duration of residence. We encourage future research to explore the pathways between LBW and HBW risk while considering inequalities in origin among foreign-born mothers in their destination countries.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation [grant numbers: RTI2018–098455-A-C22, PID2021-128108OB-I00] and Chiara Dello Iacono acknowledges funding from the Ministry of Science and Innovation reference [PRE2019-0899070]. Sol P. Juárez acknowledges funding from the Swedish Research Council [Vetenskaprådet # 2018-01825] and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare [FORTE # 2021-00271 and #2016–07128].

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Data availability

All methods applied in this study were carried out in concordance with the Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the guarantee of digital rights (Ley Orgánica 3/2018 de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales). This research is not based on experimental protocols, but it is entirely and exclusively based on population-based data from Spanish Vital Statistics. All the individual information contained in the microdata have been duly anonymized by the Spanish National Statistical Office. The research project has been approved by the Confidentiality Committee of the Spanish National Statistical Office (Instituto Nacional de Estadística).

The article examines whether the association between country of origin and birth weight outcomes [low birth weight (LBW) and high birth weight (HBW)] is modified by the mother’s duration of residence in Spain.

Foreign-born mothers in Spain are at a higher risk of delivering offspring with HBW (≥4000 g) than native-born women. The extent to which the above-mentioned patterns change by duration of residence remains unknown.

The risk of HBW remains elevated over time, suggesting that no progress has been made in improving outcome determinants (e.g. poor medical follow-up, poor lifestyle habits, untreated associated health problems, difficulty accessing social and healthcare systems and possible lack of information).

Comments