-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gregory Y H Lip, Jean-Phillippe Collet, Michael Haude, Robert Byrne, Eugene H Chung, Laurent Fauchier, Sigrun Halvorsen, Dennis Lau, Nestor Lopez-Cabanillas, Maddalena Lettino, Francisco Marin, Israel Obel, Andrea Rubboli, Robert F Storey, Marco Valgimigli, Kurt Huber, ESC Scientific Document Group , 2018 Joint European consensus document on the management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous cardiovascular interventions: a joint consensus document of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), EP Europace, Volume 21, Issue 2, February 2019, Pages 192–193, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euy174

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In 2014, a joint consensus document dealing with the management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary or valve interventions was published, which represented an effort of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS). Since publication of this document, additional data from observational cohorts, randomized controlled trials, and percutaneous interventions as well as new guidelines have been published. Moreover, new drugs and devices/interventions are also available, with an increasing evidence base. The approach to managing AF has also evolved towards a more integrated or holistic approach. In recognizing these advances since the last consensus document, EHRA, WG Thrombosis, EAPCI, and ACCA, with additional contributions from HRS, APHRS, Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), proposed a focused update, to include the new data, with the remit of comprehensively reviewing the available evidence and publishing a focused update consensus document on the management of antithrombotic therapy in AF patients presenting with ACS and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary or valve interventions, and providing up-to-date consensus recommendations for use in clinical practice.

Table of Contents

Introduction 193a

Evidence review 193a

An overview of new data since last version of the document 193a

Observational cohorts 193a

New randomized controlled trials on antithrombotic therapy 193b

Oral anticoagulants 193b

Antiplatelet drugs 193c

Parenteral anticoagulants 193e

Stents in patients with increased bleeding risk 193e

Other data in structural interventions, i.e. valve interventions (TAVI, mitral), LAA closure 193f

Assessing stroke and bleeding risks 193h

Optimizing management 193i

Elective PCI 193i

Acute management 193j

Post-procedural and post-discharge therapy 193n

Long-term management 193p

Areas for future research 193t

Introduction

In 2014, a joint consensus document dealing with the management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary (PCI) or valve interventions was published, which represented an effort of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS).1 Since publication of this document, additional data from observational cohorts, randomized trials, and percutaneous interventions have been published. New guidelines on AF from the ESC2 and APHRS,3 and European ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) management4 as well as a focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)5 have been published.

This year, we saw publication of the 2018 update of the EHRA practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) in patients with AF6 and we expect new AF guidelines from North America from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS).

We also recognized that the approach to managing AF has evolved towards an integrated or holistic approach, with the three essential components of the patient management pathway as follows:7 (i) Avoid stroke with Anticoagulation therapy; (ii) Better symptom management, with a patient-centred, symptom-directed decision making with regard to rate or rhythm control; and (iii) Cardiovascular and comobidity risk factor management, i.e. addressing lifestyle changes and associated risks including hypertension, sleep apnoea, cardiac ischaemia, etc. This has been referred to as the ABC (Atrial fibrillation Better Care) pathway.7

In recognizing these advances since the last consensus document, EHRA, WG Thrombosis, EAPCI, and ACCA, with additional contributions from HRS, APHRS, Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), proposed a focused update to include the new data, with the remit of comprehensively reviewing the available evidence and publishing a focused update consensus document on the management of antithrombotic therapy in AF patients presenting with ACS and/or undergoing PCI or valve interventions (e.g. transcatheter aortic valve replacement), and providing up-to-date consensus recommendations for use in clinical practice. However, the ultimate decision on management must be made between the healthcare provider and the patient in light of all individual factors presented.

Evidence review

This document was prepared by the Task Force with representation from EHRA, WG Thrombosis, EAPCI, and ACCA, with additional contributions from HRS, APHRS, LAHRS and CASSA, and peer-reviewed by official external reviewers representing all these bodies. Their members made a detailed literature review, weighing the strength of evidence for or against a specific treatment or procedure, and including estimates of expected health outcomes where data exist. In controversial areas, or with respect to issues without evidence other than usual clinical practice, a consensus was achieved by agreement of the expert panel after thorough deliberation.

We opted for an easier and user-friendly system of ranking using ‘coloured hearts’ that should allow physicians to easily assess the current status of the evidence and consequent guidance (Table 1). This EHRA grading of consensus statements does not have separate definitions of the level of evidence. This categorization, used for consensus statements, must not be considered as directly similar to that used for official society guideline recommendations, which apply a classification (Class I-–III) and level of evidence (A, B, and C) to recommendations used in official guidelines.

| Definitions where related to a treatment or procedure . | Consensus statement instruction . | Symbol . |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific evidence that a treatment or procedure is beneficial and effective. Requires at least one randomized trial or is supported by strong observational evidence and authors’ consensus (as indicated by an asterisk). | ‘Should do this’ |  |

| General agreement and/or scientific evidence favour the usefulness/efficacy of a treatment or procedure. May be supported by randomized trials based on a small number of patients or which is not widely applicable. | ‘May do this’ |  |

| Scientific evidence or general agreement not to use or recommend a treatment or procedure. | ‘Do not do this’ |  |

| Definitions where related to a treatment or procedure . | Consensus statement instruction . | Symbol . |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific evidence that a treatment or procedure is beneficial and effective. Requires at least one randomized trial or is supported by strong observational evidence and authors’ consensus (as indicated by an asterisk). | ‘Should do this’ |  |

| General agreement and/or scientific evidence favour the usefulness/efficacy of a treatment or procedure. May be supported by randomized trials based on a small number of patients or which is not widely applicable. | ‘May do this’ |  |

| Scientific evidence or general agreement not to use or recommend a treatment or procedure. | ‘Do not do this’ |  |

This categorization for our consensus document should not be considered as being directly similar to that used for official society guideline recommendations which apply a classification (I–III) and level of evidence (A, B, and C) to recommendations.

| Definitions where related to a treatment or procedure . | Consensus statement instruction . | Symbol . |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific evidence that a treatment or procedure is beneficial and effective. Requires at least one randomized trial or is supported by strong observational evidence and authors’ consensus (as indicated by an asterisk). | ‘Should do this’ |  |

| General agreement and/or scientific evidence favour the usefulness/efficacy of a treatment or procedure. May be supported by randomized trials based on a small number of patients or which is not widely applicable. | ‘May do this’ |  |

| Scientific evidence or general agreement not to use or recommend a treatment or procedure. | ‘Do not do this’ |  |

| Definitions where related to a treatment or procedure . | Consensus statement instruction . | Symbol . |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific evidence that a treatment or procedure is beneficial and effective. Requires at least one randomized trial or is supported by strong observational evidence and authors’ consensus (as indicated by an asterisk). | ‘Should do this’ |  |

| General agreement and/or scientific evidence favour the usefulness/efficacy of a treatment or procedure. May be supported by randomized trials based on a small number of patients or which is not widely applicable. | ‘May do this’ |  |

| Scientific evidence or general agreement not to use or recommend a treatment or procedure. | ‘Do not do this’ |  |

This categorization for our consensus document should not be considered as being directly similar to that used for official society guideline recommendations which apply a classification (I–III) and level of evidence (A, B, and C) to recommendations.

Thus, a green heart indicates a ‘should do this’ consensus statement or indicated treatment or procedure that is based on at least one randomized trial, or is supported by strong observational evidence that it is beneficial and effective. A yellow heart indicates general agreement and/or scientific evidence favouring a ‘may do this’ statement or the usefulness/efficacy of a treatment or procedure. A ‘yellow heart’ symbol may be supported by randomized trials based on a small number of patients or which is not widely applicable. Treatment strategies for which there is scientific evidence of potential harm and should not be used (‘do not do this’) are indicated by a red heart.

An overview of new data since last version of the document

Observational cohorts

Since the publication of the previous consensus document, at least 30 observational reports on patients on oral anticoagulation (OAC) presenting with ACS and/or undergoing PCI have been published8–37 (Supplementary material online, Table Sw1).

A total of 171 026 patients have been included, with AF being the most frequent, albeit not the only, indication for OAC. For 29 418 patients, information on the different antithrombotic strategies was provided: 7656 (26%) received triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT) of OAC, aspirin and a P2Y12-receptor inhibitor (generally clopidogrel), 21 279 (72%) DAPT of aspirin and P2Y12-receptor inhibitor (generally clopidogrel), and 483 (2%) dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT) of OAC and either aspirin or clopidogrel. In all studies, except three14,15,21 where approximately 50%, 39%, and 8% of patients, respectively, received a NOAC as part of the antithrombotic regimen, OAC consisted of a vitamin K-antagonist (VKA), generally warfarin (Supplementary material online, Table Sw1). Indication for PCI included, in most cases, either ACS or stable coronary artery disease (CAD). The majority were retrospective analyses of either small-size databases or large, multicentre nationwide registries that had generally been set up for other purposes. In only a few cases, the data were derived from prospective, observational registries specifically designed to evaluate the management strategies and outcomes of OAC patients undergoing PCI. Length of follow-up was variable, ranging from in-hospital to 6 years (Supplementary material online, Table Sw1) between 1999 and 2015.

Overall, TAT was consistently associated with a significantly increased risk of total and/or major bleeding compared with other antithrombotic regimens. The risk of (major) bleeding may be inversely related to the quality of OAC, measured as time in therapeutic range (TTR) for patients receiving a VKA.8 The bleeding risk profile may impact on the occurrence of major bleeding more than the antithrombotic combination.10 The rates of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) were similar irrespective of the antithrombotic regimen and/or use of OAC.

The limitations of these studies include the lack of randomization and associated selection bias in the prescription of the various antithrombotic regimens, as well as the lack of systematic bleeding risk assessment, incomplete information on adherence to treatment and TTR values, the independent contribution of periprocedural management on the occurrence of MACCE and bleeding, and the alterations in the prescribed antithrombotic therapy subsequent to an ischaemic or haemorrhagic event.

In patients with CHA2DS2-VASc [congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled)-vascular disease, age 65–74 and sex category (female)] score 1 when compared with ≥2, the efficacy of TAT in the prevention of stroke and/or systemic embolism was not statistically superior to DAPT22 (Supplementary material online, Table Sw1). In general, these data have to be interpreted with caution as this registry study was small and not randomized. The use of the newer, more potent P2Y12-receptor inhibitors, prasugrel and ticagrelor as part of a TAT regime, has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding events. No specific information on the relative efficacy and safety of NOACs, either as a category or as individual agents, can be derived from available observational data. Further data are expected to come from the observational, multicentre AVIATOR 2 registry.38 This study was capped after including 500 (of the originally planned 2500) AF patients undergoing PCI and evaluates MACCE and bleeding rates.

New randomized controlled trials on antithrombotic therapy

Oral anticoagulants

Since publication of the 2014 consensus document, two randomized controlled trials on NOAC vs. VKA in combination with antiplatelets for patients with AF undergoing PCI have been published primarily investigating safety,39,40 and at least two large trials are ongoing.

In the randomized PIONEER AF PCI trial (Open-Label, Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Study Exploring Two Treatment Strategies of Rivaroxaban, and a Dose-Adjusted Oral Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment Strategy in Subjects with Atrial Fibrillation who Undergo Percutaneous Coronary Intervention), 2124 participants with non-valvular AF who had undergone PCI with stenting (about 30% of patients had a troponin-positive ACS and about 20% had unstable angina as index event) were randomly assigned to DAT with ‘low-dose’ rivaroxaban [15 mg od (once daily)] plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months (Group 1), novel TAT with ‘very-low-dose’ rivaroxaban [2.5 mg bid (twice daily)] plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (Group 2), or standard therapy with a dose-adjusted VKA (od) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (Group 3).39 The primary endpoint of the trial was clinically-significant bleeding. The rates of clinically-significant bleeding were lower in the two groups receiving rivaroxaban than in the group receiving standard therapy (16.8% in Group 1, 18.0% in Group 2, and 26.7% in Group 3; P < 0.001 for both comparisons). There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, although the study was not powered for efficacy and the observed broad confidence intervals (CIs) diminish the surety of any conclusions. No power calculation in this exploratory trial, recruitment was not event-driven, and that prior stroke was an exclusion criteria (which led to the selection of low risk patients).

In the Randomized Evaluation of Dual Antithrombotic Therapy With Dabigatran vs. Triple Therapy With Warfarin in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (RE-DUAL PCI) study,39,40 DAT with dabigatran etexilate (110 or 150 mg bid) and a P2Y12 inhibitor (either clopidogrel or ticagrelor) was compared with TAT with warfarin, a P2Y12 inhibitor (either clopidogrel or ticagrelor), and low-dose aspirin (for 1 or 3 months, depending on stent type) in 2725 non-valvular AF patients who had undergone PCI with stenting. The primary endpoint was major or clinically-relevant non-major bleeding during follow-up, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH). The trial also tested for the non-inferiority of dual therapy with dabigatran (both doses combined) to TAT with warfarin with respect to the incidence of a composite efficacy Endpoint of thromboembolic events (MI, stroke, or systemic embolism), death, or unplanned revascularization. Approximately half of the patients had an ACS. Most of the patients received clopidogrel as the P2Y12 inhibitor; only 12.0% received ticagrelor. Drug-eluting stents alone were used in 82.6% of the patients.

In RE-DUAL PCI, the incidence of the primary endpoint was 15.4% in the 110-mg DAT group when compared with 26.9% in the TAT group [hazard ratio (HR) 0.52, 95% CI 0.42–0.63; P < 0.001 for non-inferiority; P < 0.001 for superiority] and 20.2% in the 150-mg DAT group when compared with 25.7% in the corresponding TAT group, which did not include elderly patients outside the United States (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.58–0.88; P < 0.001 for non-inferiority). The incidence of the composite efficacy endpoint was 13.7% in the two DAT groups combined when compared with 13.4% in the TAT group (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.84–1.29; P = 0.005 for non-inferiority). When looking at the two dabigatran groups separately, there was a non-significant excess in the number of ischaemic events (i.e. stent thrombosis and MI) with the 110 mg bid dose compared with TAT.

Apixaban has been shown to have similar beneficial effects on stroke or systemic embolism and major bleeding compared with warfarin, irrespective of concomitant aspirin use.41 However, no completed trial has studied apixaban as part of dual or triple therapy in patients with AF and ACS or PCI. The ongoing AUGUSTUS study (NCT02415400) is an open-label, 2 × 2 factorial, randomized, controlled non-inferiority clinical trial to evaluate the safety of apixaban (standard dosing) vs. VKA and aspirin vs. aspirin placebo in patients with AF and ACS (the only trial including ACS patients treated conservatively or by PCI).42 The primary focus is a comparison of the bleeding risk of apixaban, with or without aspirin, vs. a VKA such as warfarin, with or without aspirin. This study will include 4600 patients and enrolment was completed in April 2018 (Table 2). The Edoxaban Treatment vs. Vitamin K Antagonist in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ENTRUST-AF-PCI, 1500 patients are planned) study is designed to evaluate the safety and to explore the efficacy of an edoxaban-based (standard dosing) antithrombotic regimen vs. a VKA-based antithrombotic regimen in subjects with AF following PCI with stent placement.43 In both the AUGUSTUS and the ENTRUST-AF-PCI study (again, both being safety studies not sufficiently powered for ischaemic outcomes), standard dosing of NOAC is used in combination with antiplatelets, with dose reduction only in selected patients fulfilling NOAC specific dose reduction criteria.

Randomized trials comparing NOAC vs. VKA in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention/stenting

| Author, year . | Study design . | Size (n) . | Comparison . | Summary of findings . | Comment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published RCTs | |||||

| Gibson et al.39 (PIONEER AF PCI) | RCT Open-label (exploratory without statistical power calculation) | 2124 | 15 mg rivaroxaban od plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months, very-low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg bid) plus dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 1, 6, or 12 months, or standard therapy with a dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonist (od) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months | Rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the two groups receiving rivaroxaban than in the group receiving standard therapy with VKA (16.8% vs. 26.7% and 18.0% vs. 26.7%; P < 0.001 for both comparisons) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Cannon et al.39,40 (RE-DUAL PCI) | RCT Open-label PROBE design | 2725 | Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran etexilate (110 mg or 150 mg bid) plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor is compared with triple therapy with warfarin | ISTH major or CRNM bleeding was significantly lower in the two groups receiving dual therapy with dabigatran than in the group receiving triple therapy with warfarin (15.4% vs. 26.9% and 20.2% vs. 25.7%) (HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.42–0.63 and HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.58–0.88, respectively) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Ongoing RCTs | |||||

| AUGUSTUS42 (NCT02415400) | RCT Open-label, 2 × 2 factorial design | 4600 patients with ACS or PCI | Two randomization steps include (i) Apixaban (5 mg bid) vs. VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy and (ii) Aspirin vs. Aspirin Placebo | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Enrolment completed April 2018 |

| ENTRUST-AF-PCI43 (NCT02866175) | RCT | 1500 | Edoxaban-based regimen (60 mg od) is compared with a VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Estimated completion 2019 |

| Author, year . | Study design . | Size (n) . | Comparison . | Summary of findings . | Comment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published RCTs | |||||

| Gibson et al.39 (PIONEER AF PCI) | RCT Open-label (exploratory without statistical power calculation) | 2124 | 15 mg rivaroxaban od plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months, very-low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg bid) plus dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 1, 6, or 12 months, or standard therapy with a dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonist (od) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months | Rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the two groups receiving rivaroxaban than in the group receiving standard therapy with VKA (16.8% vs. 26.7% and 18.0% vs. 26.7%; P < 0.001 for both comparisons) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Cannon et al.39,40 (RE-DUAL PCI) | RCT Open-label PROBE design | 2725 | Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran etexilate (110 mg or 150 mg bid) plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor is compared with triple therapy with warfarin | ISTH major or CRNM bleeding was significantly lower in the two groups receiving dual therapy with dabigatran than in the group receiving triple therapy with warfarin (15.4% vs. 26.9% and 20.2% vs. 25.7%) (HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.42–0.63 and HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.58–0.88, respectively) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Ongoing RCTs | |||||

| AUGUSTUS42 (NCT02415400) | RCT Open-label, 2 × 2 factorial design | 4600 patients with ACS or PCI | Two randomization steps include (i) Apixaban (5 mg bid) vs. VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy and (ii) Aspirin vs. Aspirin Placebo | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Enrolment completed April 2018 |

| ENTRUST-AF-PCI43 (NCT02866175) | RCT | 1500 | Edoxaban-based regimen (60 mg od) is compared with a VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Estimated completion 2019 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CRNM, clinically relevant non-major; CI, confidence interval; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; HR, hazard ratio; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PROBE, prospective open-label blinded event adjudication; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

Randomized trials comparing NOAC vs. VKA in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention/stenting

| Author, year . | Study design . | Size (n) . | Comparison . | Summary of findings . | Comment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published RCTs | |||||

| Gibson et al.39 (PIONEER AF PCI) | RCT Open-label (exploratory without statistical power calculation) | 2124 | 15 mg rivaroxaban od plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months, very-low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg bid) plus dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 1, 6, or 12 months, or standard therapy with a dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonist (od) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months | Rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the two groups receiving rivaroxaban than in the group receiving standard therapy with VKA (16.8% vs. 26.7% and 18.0% vs. 26.7%; P < 0.001 for both comparisons) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Cannon et al.39,40 (RE-DUAL PCI) | RCT Open-label PROBE design | 2725 | Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran etexilate (110 mg or 150 mg bid) plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor is compared with triple therapy with warfarin | ISTH major or CRNM bleeding was significantly lower in the two groups receiving dual therapy with dabigatran than in the group receiving triple therapy with warfarin (15.4% vs. 26.9% and 20.2% vs. 25.7%) (HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.42–0.63 and HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.58–0.88, respectively) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Ongoing RCTs | |||||

| AUGUSTUS42 (NCT02415400) | RCT Open-label, 2 × 2 factorial design | 4600 patients with ACS or PCI | Two randomization steps include (i) Apixaban (5 mg bid) vs. VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy and (ii) Aspirin vs. Aspirin Placebo | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Enrolment completed April 2018 |

| ENTRUST-AF-PCI43 (NCT02866175) | RCT | 1500 | Edoxaban-based regimen (60 mg od) is compared with a VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Estimated completion 2019 |

| Author, year . | Study design . | Size (n) . | Comparison . | Summary of findings . | Comment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published RCTs | |||||

| Gibson et al.39 (PIONEER AF PCI) | RCT Open-label (exploratory without statistical power calculation) | 2124 | 15 mg rivaroxaban od plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months, very-low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg bid) plus dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 1, 6, or 12 months, or standard therapy with a dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonist (od) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months | Rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the two groups receiving rivaroxaban than in the group receiving standard therapy with VKA (16.8% vs. 26.7% and 18.0% vs. 26.7%; P < 0.001 for both comparisons) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Cannon et al.39,40 (RE-DUAL PCI) | RCT Open-label PROBE design | 2725 | Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran etexilate (110 mg or 150 mg bid) plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor is compared with triple therapy with warfarin | ISTH major or CRNM bleeding was significantly lower in the two groups receiving dual therapy with dabigatran than in the group receiving triple therapy with warfarin (15.4% vs. 26.9% and 20.2% vs. 25.7%) (HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.42–0.63 and HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.58–0.88, respectively) | Not powered for efficacy |

| Ongoing RCTs | |||||

| AUGUSTUS42 (NCT02415400) | RCT Open-label, 2 × 2 factorial design | 4600 patients with ACS or PCI | Two randomization steps include (i) Apixaban (5 mg bid) vs. VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy and (ii) Aspirin vs. Aspirin Placebo | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Enrolment completed April 2018 |

| ENTRUST-AF-PCI43 (NCT02866175) | RCT | 1500 | Edoxaban-based regimen (60 mg od) is compared with a VKA based triple antithrombotic therapy | Primary outcome: ISTH major or CRNM bleeding during the treatment period | Estimated completion 2019 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CRNM, clinically relevant non-major; CI, confidence interval; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; HR, hazard ratio; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PROBE, prospective open-label blinded event adjudication; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of four randomized clinical trials including 5317 patients [3039 (57%) received DAT], Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major or minor bleeding showed a reduction by 47% in the DAT arm compared with the TAT arm (4.3% vs. 9.0%; HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36–0.85).44 There was no difference in the major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (10.4% vs. 10.0%, HR 0.85, 95% CrI 0.48–1.29), or in individual outcomes of all-cause mortality, cardiac death, MI, stent thrombosis, or stroke between DAT and TAT.

Antiplatelet drugs

The WOEST study initially tested the concept of dropping aspirin after PCI and using a combination of clopidogrel and warfarin alone, suggesting that this approach is effective and safe in terms of thrombotic events, and reduced overall bleeding risk.45 As discussed above, the PIONEER and RE-DUAL trials39,40 further reinforce the concept of potential redundancy of aspirin and its associated bleeding hazard in AF patients treated with anticoagulant and P2Y12 inhibitor.

Although in a non-AF population, the GEMINI-ACS-1 study has reinforced the concept that oral anticoagulation may substitute for aspirin in patients who are stable early after PCI, showing that rivaroxaban combined with either clopidogrel or ticagrelor provided similar efficacy in prevention of ischaemic events compared with aspirin with either of these P2Y12 inhibitors.46 The COMPASS study demonstrated higher efficacy of rivaroxaban 2.5 mg bid plus aspirin 100 mg od in long-term prevention of ischaemic events vs. aspirin alone, in a non-AF vascular disease population. This was accompanied by higher bleeding complications when compared with aspirin alone, and does not support the suggestion that aspirin can be substituted by an OAC.47 The GLOBAL-LEADERS study is assessing, amongst other concepts, whether ticagrelor monotherapy from 1 month after PCI is superior to standard DAPT and will further define the necessity of aspirin from this timepoint in a non-AF population.48 TWILIGHT is the largest study to date that is designed and powered in order to demonstrate a lower bleeding rate with ticagrelor monotherapy vs. ticagrelor plus acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) beyond 3 months post-procedure in a high-risk patient population undergoing PCI with drug-eluting stents (DES).49

Overall, limited numbers of patients have been studied with the combination of an anticoagulant and either prasugrel or ticagrelor.23,28,50 Because of the greater platelet inhibition with approved doses of prasugrel or ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel, the risk of spontaneous bleeding is higher when used in combination with aspirin.51,52

The PEGASUS-TIMI 54 study assessed a lower dose of ticagrelor (60 mg bid) in addition to the 90 mg bid dose licensed for use in ACS in combination with aspirin (75–150 mg od) in non-AF patients within 1–3 years of MI and at higher risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events.53 Both doses of ticagrelor had similar efficacy and safety although there were numerical trends suggesting less minor bleeding and better tolerability with ticagrelor 60 mg bid.54 Interestingly, the extent of platelet inhibition with ticagrelor 60 mg bid was similar to that achieved with ticagrelor 90 mg bid.55 The TROPICAL-ACS study suggested that guided de-escalation from prasugrel to clopidogrel (in clopidogrel responders) after PCI is non-inferior to continuing prasugrel in a DAPT strategy.56 Another de-escalation trial (TOPIC) compared a switch from DAPT (aspirin plus a new P2Y12-inhibitor) with conservative DAPT (aspirin plus clopidorel) 1 month after ACS or to continue their initial drug regimen (unchanged DAPT).57 These authors reported that switched DAPT is superior to an unchanged DAPT strategy to prevent bleeding complications without increase in ischaemic events following ACS, although these studies were not powered to compare ischaemic event rates However, the implications of poor response to clopidogrel in patients treated with clopidogrel and an anticoagulant, rather than aspirin, are not well characterized.

Parenteral anticoagulants

Recent meta-analysis of 2325 VKA-treated AF patients undergoing coronary angiography with or without PCI showed that both bleeding and 30-day major adverse cardiovascular event rates were similar between those with interrupted or uninterrupted VKA.58 However, those who received parenteral bridging anticoagulants on interruption of VKA had higher major bleeding rates.58 The above data confirm recommendations of uninterrupted anticoagulation for elective PCI.1 At present, little is known regarding the bleeding and MACCE rates with continuation or interruption of NOAC during PCI.

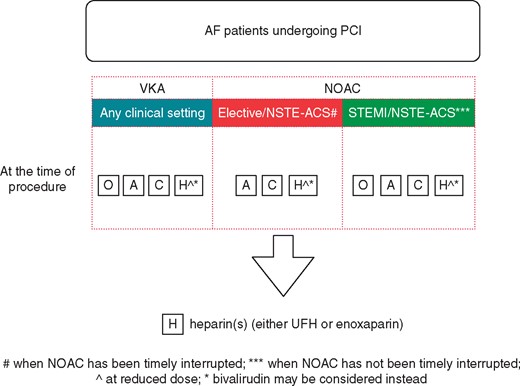

Limited data exists to guide the choice of and the dose of parenteral anticoagulants, whether unfractionated heparin (UFH), bivalirudin, or enoxaparin and their optimal dosages, specific to AF patients already taking OAC when undergoing PCI for ACS. Additional parenteral anticoagulants may not be needed, particularly if the international normalized ratio (INR) is more than 2.5 at the time of elective PCI.1,59 On the other hand, the usage of parenteral anticoagulants during PCI is recommended in AF patients on NOAC regardless of the timing of the last NOAC dose.59

Stents in patients with increased bleeding risk

Drug-eluting and bare-metal stents

Since December 2014, three large-scale trials, comparing different stents, have enrolled relatively high proportions of patients with AF requiring treatment with OAC. One trial enrolled patients regarded as being uncertain candidates for DES at the time.60 About 12% had OAC at discharge. This pre-specified post hoc analysis of the ZEUS trial demonstrated that the use of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent is superior to bare-metal stents in terms of the composite of death, MI and target vessel revascularization (TVR) (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61–0.95; P = 0.011) in patients at high bleeding risk (mainly triggered by TVR).60 The median duration of DAPT was 1 month.

Another prospective randomized trial enrolled patients at high bleeding risk and randomly allocated treatment with a polymer-free biolimus A9-DES vs. a bare-metal stent (LEADERS FREE trial).61 The main finding was that the primary safety endpoint of death, MI, and stent thrombosis was reduced with the biolimus A9-DES (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56–0.91; P < 0.001 for non-inferiority and P = 0.005 for superiority). In line with expectations, the primary efficacy endpoint of target lesion revascularization was reduced by half with the biolimus A9-DES (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.37–0.69; P < 0.001), while death as single endpoint was not reduced. Treatment effects were consistent in patients with planned OAC therapy at discharge for efficacy and safety endpoints.

Subgroup analysis demonstrated similar outcome data for the biolimus A9-DES vs. bare-metal stents in elderly patients; there was evidence of interaction with regard to treatment effect and diagnosis of ACS at baseline in relation to the primary safety endpoint (P = 0.04) with greater benefit for patients treated with the biolimus A9-DES.62 Safety and efficacy were maintained during an extended follow-up out to 2 years, even amongst the subgroup of patients who were candidates for long term OAC.63,64

A more recent clinical trial compared the outcomes of elderly patients (>75 years) undergoing PCI with a new generation DES (biodegradable polymer everolimus-eluting stents) compared with bare-metal stents (SENIOR trial), where 17.6% had AF at enrolment.65 DAPT was recommended in both groups for the same duration: 1 month in patients with stable angina and 6 months in patients with ACS. The composite of death, MI, stroke, or target lesion revascularization was significantly reduced in patients treated with DES (relative risk 0.71, 95% CI 0.52–0.94; P = 0.02). Bleeding was similar in both groups, in line with the identical recommendations for antithrombotic treatment in both groups.

Results with new-generation DES are generally excellent across the spectrum of patient and lesion subgroups. A recent systematic review of 158 trials—conducted as part of a ESC-EAPCI task force on the evaluation of coronary stents—reported low rates of both restenosis and stent thrombosis at 9–12 months with new-generation DES (less than 5% and 1%, respectively), with lower rates compared with both bare-metal stents and early-generation DES.66 Large-scale registries support the generally high efficacy and safety of new-generation DES. Convincing data to support different durations of DAPT according to stent type are lacking and the general recommendation for 1-month DAPT after bare-metal stenting in stable patients is not well supported. More recently, drug-eluting balloons can be an alternative for stenting in special lesions (e.g in patients with in-stent restenosis).

The 2017 ESC Focused Update on Antiplatelet Therapy recommends that choice of duration of DAPT in patients should no longer be differentiated on basis of device used, i.e. whether the stent implanted at time of PCI is a DES or bare-metal stent, or whether a drug eluting balloon is used.5 In view of the superior antirestenotic efficacy and no signal of higher thrombotic risks even after short term DAPT duration of new generation DES when compared with BMS, it is recommended that patients with AF undergoing PCI should be treated with new generation DES.

Bioresorbable scaffolds

Bioresobable scaffolds (BRS) are rarely used in clinical practice at present,67 due to an increased risk of target lesion failure and device thrombosis at 2–3 year follow-up and an excess of 1-year target vessel MI and stent thrombosis in comparison with conventional DES.68

Consensus statements

| . | . | References . |

|---|---|---|

|  | 5,66 |

|  | 5 |

|  | 63,64 |

| . | . | References . |

|---|---|---|

|  | 5,66 |

|  | 5 |

|  | 63,64 |

DES, drug-eluting stent; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; BRS, biovascular scaffold.

| . | . | References . |

|---|---|---|

|  | 5,66 |

|  | 5 |

|  | 63,64 |

| . | . | References . |

|---|---|---|

|  | 5,66 |

|  | 5 |

|  | 63,64 |

DES, drug-eluting stent; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; BRS, biovascular scaffold.

Other data in structural interventions, i.e. valve interventions (TAVI, mitral), left atrial appendage closure

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Cerebral embolization is one of the major complications that might occur in the very early phase of valve placement. New periprocedural cerebral ischaemic defects have been reported in more than 60% of patients, and clinically-apparent stroke occurs in around 3% of cases on average (range 0–6%).69

Despite a higher incidence of cerebrovascular events with the first devices in the PARTNERS trials,70,71 there seems to be a similar risk of stroke in patients undergoing TAVI compared with patients receiving the surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).72–75 Parenteral antithrombotic treatment during TAVI aims to prevent thrombo-embolic complications related to large catheter manipulation, guidewire insertion, balloon aortic valvuloplasty, and valve prosthesis implantation, while minimizing the risk of bleeding, particularly at the vascular access site. Based on retrospective studies and randomized trials,72,73,76,77 the most commonly used anticoagulant is UFH at doses of 50–70 IU/kg with a target activated clotting time (ACT) of 250–300 s, although no optimal ACT has been defined, even in guidelines.78–82 Given the higher cost and similar efficacy of bivalirudin when compared with UFH, the latter should remain the standard of care for patients undergoing TAVI unless contra-indications to UFH, such as known heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, exist.83

Subacute cerebrovascular events associated with TAVI occur between 24 h and 30 days, while all the episodes occurring after 30 days are defined as late. Stroke rate at 30 days reported by randomized clinical trials and registries ranges from 0% to 9%.84 Factors potentially involved in such cerebrovascular events development are: thrombogenicity of the valve apparatus, exposure of the stent struts (expanded together with the valve), persistence of the perivalvular space occupied by the native valve and the development of paroxysmal atrial arrhythmias.69,82 Moreover, the baseline risk for ischaemic and thromboembolic complications is further increased by comorbidities including concomitant CAD, which is present in 20–70% of patients and requires PCI in 20–40% of patients. Furthermore, AF is found in about one-third of patients referred for TAVI.70,71,85–87

Prospective data on antithrombotic therapy after TAVI are still scarce and recommendations regarding choice and optimal duration of antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapy are largely based on experience from PCI and open-heart aortic valve replacement.

Among patients without CAD and without AF, the current standard of care is still DAPT consisting of low-dose aspirin (75–100 mg per day) and clopidogrel 75 mg od (after loading dose of 300–600 mg), both started within 24 h prior to the intervention, and continued for 3–6 months followed by indefinite aspirin monotherapy. Patients receiving single antiplatelet therapy soon after TAVI tended to have a lower rate of major adverse events after the intervention when compared with patients on DAPT, with a significant reduction of major and life-threatening bleeding complications at three months follow-up.88 A meta-analysis of the pooled results of this trial and other minor studies showed no benefit of DAPT in early stroke reduction with a trend towards an increase in major bleeding, thus suggesting the opportunity to adopt an antiplatelet monotherapy soon after the intervention for all patients without indication for anticoagulation.89

Other clinical trials are currently ongoing. The Antiplatelet Therapy for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (POPular TAVI, n = 1000) trial is currently exploring whether it is possible to skip clopidogrel in a larger population of patients undergoing TAVI with or without an indication for OAC prior to the procedure. Patients are randomized to aspirin alone vs. aspirin plus clopidogrel for the first 3 months after the procedure and evaluated for the primary safety endpoint of freedom of non-procedure-related bleeding complications at 1 year follow-up. The cohort of patients for whom OAC is indicated (AF, mechanical valve prostheses) is randomized to clopidogrel plus OAC vs. OAC alone (NCT02247128).

The Global Study Comparing a rivAroxaban-based Antithrombotic Strategy to an antiplatelet-based Strategy after Transcatheter aortic vaLve rEplacement to Optimize Clinical Outcome (Galileo, n = 1520) study is an open-label, multicentre, randomized controlled trial actively recruiting patients undergoing TAVI with no indication to permanent anticoagulant therapy. Patients assigned to the OAC arm are randomly assigned to receive 10 mg od rivaroxaban up to 25 months plus low-dose aspirin during the first 3 months in order to assess whether this strategy is superior to DAPT with aspirin plus clopidogrel (for 3 months) followed by aspirin alone in reducing death or first clinical thromboembolic events with no increase in bleeding complications (NCT02556203).90

Third, the Anti-Thrombotic Strategy after Trans-Aortic Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis (ATLANTIS, n = 1509) trial is evaluating whether an anticoagulant-based strategy with apixaban 5 mg bid is superior to standard-of-care therapy in preventing death, MI, stroke, systemic embolism, intracardiac or bioprosthesis thrombus formation, or life-threatening/major bleeding complications at 1 year follow-up in patients successfully treated with a TAVI procedure. The ATLANTIS trial will include two different populations: patients with an indication for anticoagulation, where standard of care is represented by a VKA and patients for whom an antiplatelet regimen with aspirin plus clopidogrel is the first-choice antithrombotic treatment. Randomization is consequently stratified according to the need (or no need) for anticoagulation for clinical reasons other than TAVI itself (NCT02664649).

Finally, another study that aims at demonstrating the superiority of a single anticoagulant vs. the combination of an anticoagulation plus aspirin with respect to a net clinical benefit endpoint at 1 year (the AVATAR trial, NCT02735902) has been announced (n = 170).

Among TAVI patients with AF but without CAD, OAC is recommended in accordance with recommendations for AF alone.1 Whether the addition of antiplatelet therapy to OAC is required in this context remains to be determined. The existing experience with patients receiving biological aortic valve replacement suggests that OAC alone may be sufficient to prevent thrombotic events.79 Indeed, OAC (essentially VKA) use in surgically-implanted biological aortic valves is generally recommended for only 3 months and can be stopped thereafter, except where patients have other reasons for prolonged or life-long OAC.

The POPular TAVI trial, which is currently recruiting patients, will provide information regarding the safety and the net clinical benefit of a VKA alone vs. the combination of clopidogrel plus a VKA in patients undergoing TAVI who have an indication to permanent OAC.91 With reference to the life-long use of a NOAC compared with VKA, beyond the reported ATLANTIS trial, the Edoxaban Compared to Standard Care after Heart Valve Replacement Using a Catheter in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (ENVISAGE-TAVI AF) trial recently started recruiting a planned population of 1400 AF patients undergoing TAVI. The study will compare the two anticoagulant drugs (warfarin vs. edoxaban) in terms of overall side effects and major bleeding during 3 years follow-up (NCT02943785).

In summary, TAVI patients taking OAC (e.g. for AF) and recent PCI should be treated similarly to patients receiving a stent without TAVI. While awaiting results of controlled randomized trials, patients undergoing TAVI without concomitant need for OAC should receive an antiplatelet regimen consisting of lifelong aspirin monotherapy or aspirin and clopidogrel for 3–6 months followed by aspirin monotherapy, depending on bleeding risk, and concomitant treated or untreated coronary artery disease. The use of prasugrel or ticagrelor in combination with aspirin or NOAC after TAVI has not been investigated and cannot be recommended at this time.

Mitral intervention

No study has addressed the optimal antithrombotic regimen after percutaneous edge-to-edge transcatheter mitral valve repair (e.g. MitraClip system, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA92) Pivotal studies have mandated the use of aspirin for at least 6 months in combination with clopidogrel for 1–3 months in patients without AF while patients with AF are treated with OAC plus aspirin.93

Transcatheter mitral valve implantation (TMVI) with a transcatheter mitral valve prosthesis has been performed in patients with surgical degenerated bioprostheses [valve-in-valve (ViV)] or with recurrent MR following mitral repair annuloplasty [valve-in-ring (ViR)].94 There is currently limited evidence that adding a single antiplatelet therapy or DAPT to OACs further decreases the risk of symptomatic or asymptomatic valve thrombosis.

Left atrial appendage closure

The left atrial appendage (LAA) is implicated in approximately 90% of strokes in patients with AF.95 Left atrial appendage occlusion, either percutaneous or surgical, is a rapidly-emerging option for patients who cannot take long-term OAC.96 Of the percutaneous options, the WATCHMAN (Boston Scientific) device is so far the only tested LAA closure device in a randomized controlled fashion. It is currently the only percutaneous device approved in both Europe and the US.

In the PROTECT-AF trial, patients were treated with warfarin and aspirin 81 mg for 45 days post-procedure, then with aspirin and clopidogrel for 6 months, and then with aspirin indefinitely.97 In the PREVAIL study, patients were on warfarin plus aspirin 81 mg for the first 45 days, then on aspirin 325 mg plus clopidogrel until post-operative month 6 (in the absence of any clot), then on aspirin 325 mg alone.98 Thus, PROTECT and PREVAIL did not enroll patients unable to take OACs, but patients who were at least able to take warfarin for 45 days post-procedure. This contradicts the current suggested indication to use a LAA closure device in patients with contraindications against OACs. Moreover, the efficacy and safety of using a NOAC instead of warfarin was not assessed in these two major trials.

These trials have been subject to much debate,99 with reports of device related thrombus that can lead to thromboembolism.100 In the absence of clinically relevant LAA leaks, OAC can be discontinued and the patient treated with DAPT or a single antiplatelet therapy for at least 6 months after the procedure, although some cardiologists continue single antiplatelet therapy long term. There are also no data to suggest the optimal management of an AF patient with left atrial appendage occlusion who requires a cardioversion. A transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) assessment for thrombus may be performed, and a shorten duration of anticoagulation similar to TOE-guided cardioversion protocol may be considered.

Amplatzer

The data on Amplatzer Cardiac Plug (now Amulet), are largely based on registry studies.101,102 The most recent study had 18.9% patients on either a VKA or NOAC immediately post-procedure.101 In a study of 52 Canadian patients receiving this device, there was an only 1.9% rate of stroke when antiplatelets alone were used post-procedure during a mean follow-up of 20 ± 5 months.103

Lariat

The LARIAT device (SentreHeart) ligates off the LAA via a combined trans-septal and epicardial approach. It received FDA approval for soft tissue closure but not specifically for LAA closure. It has not been tested in a randomized controlled trial, so efficacy data are derived from prospective registries.104 Since the US FDA released a safety alarm communication in July 2015 due to reports of adverse patient outcomes, the use of LARIAT in the US has dropped significantly (https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm454501.htm).

In summary, LAA occlusion may be considered in selected AF patients with absolute contraindications to any OAC. Trial data supporting use of shorter duration TAT or even DAT in these patients in general (as discussed above), as well as the recommendation for short duration OAC after the procedure in patients treated with Watchman device, makes the rationale for implanting these devices solely for the reason that the AF patient requires PCI unclear.

Assessing stroke and bleeding risks

The CHA2DS2-VASc has been widely used worldwide for stroke risk stratification in AF,105 even in patients with coronary artery disease treated with coronary stenting.106,107 Other less established risk factors for stroke include unstable INR and low TTR in patients treated with a VKA; previous bleed or anaemia; alcohol excess and other markers for decreased therapy adherence; chronic kidney disease; elevated high-sensitivity troponin; and elevated N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.2 Some have been incorporated into more recent stroke scores proposed for AF, such as the ATRIA (AnTicoagulation and Risk factors In Atrial fibrillation), QStroke, and ABC-stroke scores.108–110 Biomarker-based stroke risk scores (e.g. ABC score) do not appear to confer long-term benefit over simple clinical scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc.111,112 In addition, stroke risk is not static, and regular review and reassessment of risk is needed during follow-up.113,114

In the CHA2DS2-VASc score, the V criterion for ‘vascular disease’ is defined as ‘previous MI, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque’, since these are factors, which are more validated to confer an excess of stroke risk in patients with AF. Patients with mild coronary atheroma alone, or simply a history of angina, have not been definitively shown to have an excess of stroke risk if no other CHA2DS2-VASc risk factors are present (hence do not score a point for the V criterion). Patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥1 for men or ≥2 for women are likely to benefit from stroke prevention with specific treatment decisions for type and duration of associations of antithrombotic agents based on the clinical setting and patient profile (elective PCI or ACS, risk factor for CAD progression, and coronary events, risk of bleeding) possibly incorporating patient preferences.

Clinical risk scores for bleeding

Several bleeding risk scores have been developed, mainly in patients on VKAs. These include HAS-BLED [hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function (1 point each), stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile INR, elderly (>65 years), drugs/alcohol concomitantly (1 point each)], ATRIA, ORBIT (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation), and more recently, the ABC (age, biomarkers, clinical history) bleeding score, which includes selected biomarkers.115–118 While stroke and bleeding risks correlate with each other, the HAS-BLED score is a superior predictor of bleeding risk compared with the CHADS2 [congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke (doubled)] or CHA2DS2-VASc scores.119,120

The simple HAS-BLED score has similar or a superior bleeding risk assessment to other proposed scores, some of which are more complex.121–123 This is particularly evident amongst VKA users, given that other scores (HEMORRH2AGES, ATRIA, ORBIT) do not consider quality of anticoagulation control, i.e. labile INR as a bleeding risk.124,125 In another trial cohort, the ORBIT score demonstrated the best discrimination and calibration when tested in the RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulant therapY with dabigatran etexilate) trial, whereby all the scores demonstrated, to a variable extent, an interaction with bleeding risk associated with dabigatran or warfarin.126 On the other hand, the biomarker-based ABC bleeding risk score did not appear to confer long-term benefit over a more simple clinical score such as HAS-BLED.112,127 Similarly, the PRECISE DAPT score has been developed to assess the out-of-hospital bleeding risk in patients in whom DAPT but not OAC is indicated; however, this score currently does not provide useful information on the additional bleeding risk in patients in whom both OAC and DAPT are concomitantly indicated.128

Of note, the HAS-BLED, ORBIT, and ABC scores have also been validated in patients on NOACs.126,129 The HAS-BLED score has been validated in patients with CAD treated with coronary stenting.130,131 A high bleeding risk score should generally not result in withholding OAC, and is appropriately used to ‘flag up’ patients at high risk of bleeding (HAS-BLED score ≥3) for more regular review and earlier follow-up.

Of importance, modifiable bleeding risk factors (e.g. uncontrolled blood pressure, concomitant antiplatelet or NSAID use, alcohol excess) should always be identified and corrected at every patient contact. In addition, bleeding risk is not static, and regular review and reassessment of risk is needed during follow-up, especially since an adverse change in (say) HAS-BLED score is associated with excessive bleeding risk particularly in the initial 3 months.132

When managing patients with AF undergoing PCI/stenting, it is recommended to concomitantly assess stroke, bleeding, and ischaemic event risks (using validated tools such as the REACH, Syntax, and GRACE scores6,133–135) A recent retrospective analysis confirmed the value of the Syntax and GRACE scores for identifying higher risks of coronary events and mortality, respectively, in AF patients with coronary stenting.106

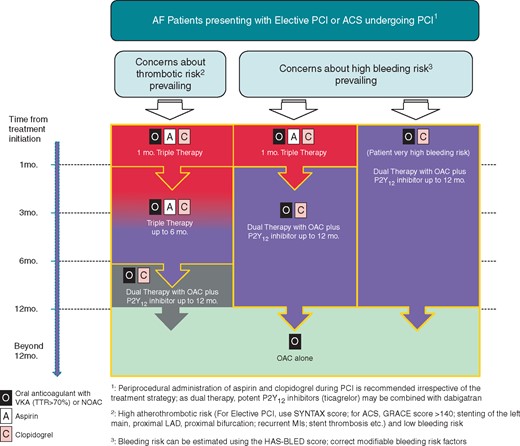

What is the practical application of formal bleeding risk assessment? An approach based only on modifiable bleeding risk factors alone is an inferior assessment compared with a formal bleeding risk score.119,136,137 A high (uncorrectable) bleeding risk may flag up the patient for earlier review and follow-up (e.g. 4 weeks rather than 4–6 months), as well as lead to shortening of TAT with earlier switch to DAT in case of estimated low atherothrombotic risk as calculated with the Syntax or REACH score, although prospective validation is missing in such combination scenarios. A similar clinical setting may lead to the decision to discontinue all antiplatelets and provide anticoagulation as monotherapy earlier (e.g. after 6 months instead of 1 year).2,6 In the small subset of AF patients undergoing PCI with elevated bleeding risk and a relatively low stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc of one in males or two in females), one option would be to treat with only DAPT, without OACs, from the onset (although in ACTIVE-W, there were numerically more MIs with aspirin plus clopidogrel compared with warfarin).138

The TIMI-AF score has recently been proposed in VKA-naive patients with AF to assist in the prediction of a poor composite outcome and guide selection of anticoagulant therapy by identifying a differential clinical benefit with a NOAC or VKA.139 This complex score includes 11 items (including a history of MI) with a maximum integer score of 17 and needs to be more specifically validated in AF patients with ACS and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary or valve interventions. In a ‘real world’ cohort of VKA-experienced AF patients, the TIMI-AF score was found to have limited usefulness in predicting net clinical outcomes over a long-term period of follow-up and was not superior to CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED for identifying low-risk AF patients.140 Another simple score, the 2MACE [two points for Metabolic Syndrome and Age ≥75; one point for MI/revascularization, Congestive heart failure (ejection fraction ≤40%), thrombo-embolism (stroke/transient ischaemic attack)] score has also been proposed for the prediction of MACE, but has not been validated in AF patients undergoing PCI.141,142

Optimizing management

Table 3 summarizes the key points outlined in major European and American guidelines in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions when on oral anticoagulation.

| . | ESC myocardial revascularization 2017143 . | ESC AF 20162 . | ACC/AHA 2016 combined OAC/APT144 . | ESC 2017 DAPT update5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of periprocedural aspirin and clopidogrel | − | − | − | ++ |

| Preferred use of DES | ++ | − | ++ | |

| Recommendations according to the type of platform (DES vs. BMS) | n/a | − | ++ | n/a |

| Use of ticagrelor or prasugrel | − | − | − | − |

| Use of specific score for ischaemic or bleeding risks | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAPT as an alternative to TAT in CHA2DS2-VASc score ≤1 | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAT as an alternative to initial TAT | + | + | n/a | ++ |

| 1–6 months as the default strategy in ACS patients | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Use of NOAC | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Stopping aspirin rather than clopidogrel | + | + | ++ | + |

| Stopping all antiplatelet therapy after 1 year | n/a | ++ | n/a | ++ |

| . | ESC myocardial revascularization 2017143 . | ESC AF 20162 . | ACC/AHA 2016 combined OAC/APT144 . | ESC 2017 DAPT update5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of periprocedural aspirin and clopidogrel | − | − | − | ++ |

| Preferred use of DES | ++ | − | ++ | |

| Recommendations according to the type of platform (DES vs. BMS) | n/a | − | ++ | n/a |

| Use of ticagrelor or prasugrel | − | − | − | − |

| Use of specific score for ischaemic or bleeding risks | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAPT as an alternative to TAT in CHA2DS2-VASc score ≤1 | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAT as an alternative to initial TAT | + | + | n/a | ++ |

| 1–6 months as the default strategy in ACS patients | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Use of NOAC | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Stopping aspirin rather than clopidogrel | + | + | ++ | + |

| Stopping all antiplatelet therapy after 1 year | n/a | ++ | n/a | ++ |

++, recommended; +, may be considered; −, not recommended by the relevant guideline; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMS, bare-metal stent; DAT, dual therapy; DES, drug-eluting stent; n/a, box means not stated; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; TAT, triple therapy.

| . | ESC myocardial revascularization 2017143 . | ESC AF 20162 . | ACC/AHA 2016 combined OAC/APT144 . | ESC 2017 DAPT update5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of periprocedural aspirin and clopidogrel | − | − | − | ++ |

| Preferred use of DES | ++ | − | ++ | |

| Recommendations according to the type of platform (DES vs. BMS) | n/a | − | ++ | n/a |

| Use of ticagrelor or prasugrel | − | − | − | − |

| Use of specific score for ischaemic or bleeding risks | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAPT as an alternative to TAT in CHA2DS2-VASc score ≤1 | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAT as an alternative to initial TAT | + | + | n/a | ++ |

| 1–6 months as the default strategy in ACS patients | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Use of NOAC | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Stopping aspirin rather than clopidogrel | + | + | ++ | + |

| Stopping all antiplatelet therapy after 1 year | n/a | ++ | n/a | ++ |

| . | ESC myocardial revascularization 2017143 . | ESC AF 20162 . | ACC/AHA 2016 combined OAC/APT144 . | ESC 2017 DAPT update5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of periprocedural aspirin and clopidogrel | − | − | − | ++ |

| Preferred use of DES | ++ | − | ++ | |

| Recommendations according to the type of platform (DES vs. BMS) | n/a | − | ++ | n/a |

| Use of ticagrelor or prasugrel | − | − | − | − |

| Use of specific score for ischaemic or bleeding risks | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAPT as an alternative to TAT in CHA2DS2-VASc score ≤1 | ++ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DAT as an alternative to initial TAT | + | + | n/a | ++ |

| 1–6 months as the default strategy in ACS patients | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Use of NOAC | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Stopping aspirin rather than clopidogrel | + | + | ++ | + |

| Stopping all antiplatelet therapy after 1 year | n/a | ++ | n/a | ++ |

++, recommended; +, may be considered; −, not recommended by the relevant guideline; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMS, bare-metal stent; DAT, dual therapy; DES, drug-eluting stent; n/a, box means not stated; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; TAT, triple therapy.

From the OAC perspective, the main management aspects pertain to the introduction of the NOACs. The latter drugs have changed the landscape of stroke prevention management amongst patients with AF, although some regional differences are evident.145

Table 4 provides a summary of the antithrombotic management differences between a VKA and NOAC in relation to management of AF patients presenting with an ACS and/or undergoing PCI/stenting.

Summary of the antithrombotic management differences between a VKA and NOAC in patients undergoing elective PCI

| . | VKA . | NOAC . |

|---|---|---|

| Periprocedural management | ||

| Anticoagulation (see Figure 1) | Because of the reduced risk of bleeding, VKA should not be interrupted (or bridged with heparin). | Elective PCI

|

| Vascular access | Because of the reduced risk of access-site bleeding complications, the radial approach should be preferred. | |

| Additional intra-procedural UFH | To prevent radial artery occlusion, and possibly limit the occurrence of intra-procedural thrombotic complications, UFH should be administered. | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, UFH should be administered as per usual practice |

| Dose of additional intra-procedural UFH | To limit the risk of bleeding (in ongoing VKA), reduced dose (30–50 U/kg) should be given. | Standard dose UFH (70–100 U/kg) should be given |

| Use of bivalirudin | Because of the observation of superior safety, and possibly also efficacy, it may be considered in accordance with prescribing label.Specific data in patients on OAC are limited. | |

| P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because of potential increased risk of bleeding with prasugrel and ticagrelor in stable CAD patients on OAC, clopidogrel is generally recommended.

| |

| Dose of P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because clopidogrel should be given in advance of PCI, 300 mg loading should generally be preferred to limit the risk of bleeding (with ongoing VKA). | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, 300 or 600 mg loading dose should be selected as per usual practice due to limited data. |

| Use of GPI | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischaemic outcomes, GPI should not be used, except for bail-out, in life-threatening situations. | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischemic outcomes, GPI should not be use where NOACs are uninterrupted, except for bail out, in life-threatening situations. |

| Use of GPI as per standard practice can be made for patients on NOAC when timely discontinuation before PCI has been carried out. | ||

| Post-procedural management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen | ||

| Intensity of OAC |

|

|

| Intensity of OAC during subsequent antithrombotic regimen after 12 months | Target INR should be 2.0–2.5 after withdrawal of one antiplatelet agent, with high TTR (>65–70%). |

|

| Duration of TAT |

| |

| Dose of aspirin | Low-dose 75–100 mg od should be used to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. | |

| Use of gastric protection | Proton-pump inhibitors should be routinely administered throughout TAT. | |

| Subsequent antithrombotic regimen after triple therapy | Upon completion of initial course of TAT, one antiplatelet agent, either aspirin (preferably), or clopidogrel should be withdrawn and DAT with OAC plus single antiplatelet therapy continued. | |

| Duration of subsequent antithrombotic regimen | Combined OAC plus single antiplatelet regimen should be continued up to 12 months after PCI.

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen |

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Intensity of OAC during long-term management | Conventional INR target 2.0–3.0 should be prescribed, with TTR >65–70%. |

|

| . | VKA . | NOAC . |

|---|---|---|

| Periprocedural management | ||

| Anticoagulation (see Figure 1) | Because of the reduced risk of bleeding, VKA should not be interrupted (or bridged with heparin). | Elective PCI

|

| Vascular access | Because of the reduced risk of access-site bleeding complications, the radial approach should be preferred. | |

| Additional intra-procedural UFH | To prevent radial artery occlusion, and possibly limit the occurrence of intra-procedural thrombotic complications, UFH should be administered. | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, UFH should be administered as per usual practice |

| Dose of additional intra-procedural UFH | To limit the risk of bleeding (in ongoing VKA), reduced dose (30–50 U/kg) should be given. | Standard dose UFH (70–100 U/kg) should be given |

| Use of bivalirudin | Because of the observation of superior safety, and possibly also efficacy, it may be considered in accordance with prescribing label.Specific data in patients on OAC are limited. | |

| P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because of potential increased risk of bleeding with prasugrel and ticagrelor in stable CAD patients on OAC, clopidogrel is generally recommended.

| |

| Dose of P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because clopidogrel should be given in advance of PCI, 300 mg loading should generally be preferred to limit the risk of bleeding (with ongoing VKA). | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, 300 or 600 mg loading dose should be selected as per usual practice due to limited data. |

| Use of GPI | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischaemic outcomes, GPI should not be used, except for bail-out, in life-threatening situations. | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischemic outcomes, GPI should not be use where NOACs are uninterrupted, except for bail out, in life-threatening situations. |

| Use of GPI as per standard practice can be made for patients on NOAC when timely discontinuation before PCI has been carried out. | ||

| Post-procedural management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen | ||

| Intensity of OAC |

|

|

| Intensity of OAC during subsequent antithrombotic regimen after 12 months | Target INR should be 2.0–2.5 after withdrawal of one antiplatelet agent, with high TTR (>65–70%). |

|

| Duration of TAT |

| |

| Dose of aspirin | Low-dose 75–100 mg od should be used to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. | |

| Use of gastric protection | Proton-pump inhibitors should be routinely administered throughout TAT. | |

| Subsequent antithrombotic regimen after triple therapy | Upon completion of initial course of TAT, one antiplatelet agent, either aspirin (preferably), or clopidogrel should be withdrawn and DAT with OAC plus single antiplatelet therapy continued. | |

| Duration of subsequent antithrombotic regimen | Combined OAC plus single antiplatelet regimen should be continued up to 12 months after PCI.

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen |

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Intensity of OAC during long-term management | Conventional INR target 2.0–3.0 should be prescribed, with TTR >65–70%. |

|

For details and references, see text.

bid, twice daily; CAD, coronary artery disease; DAT, dual antithrombotic therapy; GPI, glycoprotein Iib/IIIa inhibitor; INR, international normalized ratio; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; OAC, oral anticoagulant; od, once daily; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TAT, triple antithrombotic therapy; TTR, time in therapeutic range; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

Summary of the antithrombotic management differences between a VKA and NOAC in patients undergoing elective PCI

| . | VKA . | NOAC . |

|---|---|---|

| Periprocedural management | ||

| Anticoagulation (see Figure 1) | Because of the reduced risk of bleeding, VKA should not be interrupted (or bridged with heparin). | Elective PCI

|

| Vascular access | Because of the reduced risk of access-site bleeding complications, the radial approach should be preferred. | |

| Additional intra-procedural UFH | To prevent radial artery occlusion, and possibly limit the occurrence of intra-procedural thrombotic complications, UFH should be administered. | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, UFH should be administered as per usual practice |

| Dose of additional intra-procedural UFH | To limit the risk of bleeding (in ongoing VKA), reduced dose (30–50 U/kg) should be given. | Standard dose UFH (70–100 U/kg) should be given |

| Use of bivalirudin | Because of the observation of superior safety, and possibly also efficacy, it may be considered in accordance with prescribing label.Specific data in patients on OAC are limited. | |

| P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because of potential increased risk of bleeding with prasugrel and ticagrelor in stable CAD patients on OAC, clopidogrel is generally recommended.

| |

| Dose of P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because clopidogrel should be given in advance of PCI, 300 mg loading should generally be preferred to limit the risk of bleeding (with ongoing VKA). | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, 300 or 600 mg loading dose should be selected as per usual practice due to limited data. |

| Use of GPI | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischaemic outcomes, GPI should not be used, except for bail-out, in life-threatening situations. | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischemic outcomes, GPI should not be use where NOACs are uninterrupted, except for bail out, in life-threatening situations. |

| Use of GPI as per standard practice can be made for patients on NOAC when timely discontinuation before PCI has been carried out. | ||

| Post-procedural management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen | ||

| Intensity of OAC |

|

|

| Intensity of OAC during subsequent antithrombotic regimen after 12 months | Target INR should be 2.0–2.5 after withdrawal of one antiplatelet agent, with high TTR (>65–70%). |

|

| Duration of TAT |

| |

| Dose of aspirin | Low-dose 75–100 mg od should be used to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. | |

| Use of gastric protection | Proton-pump inhibitors should be routinely administered throughout TAT. | |

| Subsequent antithrombotic regimen after triple therapy | Upon completion of initial course of TAT, one antiplatelet agent, either aspirin (preferably), or clopidogrel should be withdrawn and DAT with OAC plus single antiplatelet therapy continued. | |

| Duration of subsequent antithrombotic regimen | Combined OAC plus single antiplatelet regimen should be continued up to 12 months after PCI.

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen |

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Intensity of OAC during long-term management | Conventional INR target 2.0–3.0 should be prescribed, with TTR >65–70%. |

|

| . | VKA . | NOAC . |

|---|---|---|

| Periprocedural management | ||

| Anticoagulation (see Figure 1) | Because of the reduced risk of bleeding, VKA should not be interrupted (or bridged with heparin). | Elective PCI

|

| Vascular access | Because of the reduced risk of access-site bleeding complications, the radial approach should be preferred. | |

| Additional intra-procedural UFH | To prevent radial artery occlusion, and possibly limit the occurrence of intra-procedural thrombotic complications, UFH should be administered. | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, UFH should be administered as per usual practice |

| Dose of additional intra-procedural UFH | To limit the risk of bleeding (in ongoing VKA), reduced dose (30–50 U/kg) should be given. | Standard dose UFH (70–100 U/kg) should be given |

| Use of bivalirudin | Because of the observation of superior safety, and possibly also efficacy, it may be considered in accordance with prescribing label.Specific data in patients on OAC are limited. | |

| P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because of potential increased risk of bleeding with prasugrel and ticagrelor in stable CAD patients on OAC, clopidogrel is generally recommended.

| |

| Dose of P2Y12-receptor inhibitor | Because clopidogrel should be given in advance of PCI, 300 mg loading should generally be preferred to limit the risk of bleeding (with ongoing VKA). | Whether NOAC is interrupted or not, 300 or 600 mg loading dose should be selected as per usual practice due to limited data. |

| Use of GPI | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischaemic outcomes, GPI should not be used, except for bail-out, in life-threatening situations. | Because of the observed increase in major bleeding, with no benefit in ischemic outcomes, GPI should not be use where NOACs are uninterrupted, except for bail out, in life-threatening situations. |

| Use of GPI as per standard practice can be made for patients on NOAC when timely discontinuation before PCI has been carried out. | ||

| Post-procedural management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen | ||

| Intensity of OAC |

|

|

| Intensity of OAC during subsequent antithrombotic regimen after 12 months | Target INR should be 2.0–2.5 after withdrawal of one antiplatelet agent, with high TTR (>65–70%). |

|

| Duration of TAT |

| |

| Dose of aspirin | Low-dose 75–100 mg od should be used to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. | |

| Use of gastric protection | Proton-pump inhibitors should be routinely administered throughout TAT. | |

| Subsequent antithrombotic regimen after triple therapy | Upon completion of initial course of TAT, one antiplatelet agent, either aspirin (preferably), or clopidogrel should be withdrawn and DAT with OAC plus single antiplatelet therapy continued. | |

| Duration of subsequent antithrombotic regimen | Combined OAC plus single antiplatelet regimen should be continued up to 12 months after PCI.

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Antithrombotic regimen |

| |

| Long-term management | ||

| Intensity of OAC during long-term management | Conventional INR target 2.0–3.0 should be prescribed, with TTR >65–70%. |