-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paolo Verdecchia, Gianpaolo Reboldi, Fabio Angeli, Giovanni Mazzotta, Gregory Y H Lip, Martina Brueckmann, Eva Kleine, Lars Wallentin, Michael D Ezekowitz, Salim Yusuf, Stuart J Connolly, Giuseppe Di Pasquale, Dabigatran vs. warfarin in relation to the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with atrial fibrillation— the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulation therapY (RE-LY) study, EP Europace, Volume 20, Issue 2, February 2018, Pages 253–262, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eux022

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) interferes with the antithrombotic effects of dabigatran and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

This is a post-hoc analysis of the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulation therapY (RE-LY) Study. We defined LVH by electrocardiography (ECG) and included patients with AF on the ECG tracing at entry. Hazard ratios (HR) for each dabigatran dose vs. warfarin were calculated in relation to LVH. LVH was present in 2353 (22.7%) out of 10 372 patients. In patients without LVH, the rates of primary outcome were 1.59%/year with warfarin, 1.60% with dabigatran 110 mg (HR vs. warfarin 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.75–1.36) and 1.08% with dabigatran 150 mg (HR vs. warfarin 0.68, 95% CI 0.49–0.95). In patients with LVH, the rates of primary outcome were 3.21%/year with warfarin, 1.69% with dabigatran 110 mg (HR vs. warfarin 0.52, 95% CI 0.32–0.84) and 1.55% with 150 mg (HR vs. warfarin 0.48, 95% CI 0.29–0.78). The interaction between LVH status and dabigatran 110 mg vs. warfarin was significant for the primary outcome (P = 0.021) and stroke (P = 0.016). LVH was associated with a higher event rate with warfarin, not with dabigatran. In the warfarin group, the time in therapeutic range was significantly lower in the presence than in the absence of LVH.

LVH was associated with a lower antithrombotic efficacy of warfarin, but not of dabigatran, in patients with AF. Consequently, the relative benefit of the lower dose of dabigatran compared to warfarin was enhanced in patients with LVH. The higher dose of dabigatran was superior to warfarin regardless of LVH status.

http:www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00262600.

Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) diagnosed by traditional electrocardiography (ECG) portends a higher risk of stroke, death, and myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF)1. Patients with LVH have enhanced coagulability2,3 and inflammation.4,5 The higher risk of left atrial thrombosis in AF patients with LVH treated with warfarin2,6,7 suggests that LVH might interfere with the efficacy of vitamin K antagonists. LVH has also been linked with a state of increased systemic inflammation in experimental4 and clinical5 studies. In this setting, there is evidence that thrombin may trigger inflammatory and fibrotic reactions beyond the coagulation cascade,8–10 and that these reactions can be blunted by direct thrombin inhibition with dabigatran.11,12

The experimental and clinical findings summarized above led us to hypothesize that LVH might interfere with the antithrombotic effects of dabigatran, as compared with warfarin, in patients with AF.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we performed a post-hoc subgroup analysis of AF patients with and without LVH from the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulation therapY (RE-LY) Study13 regarding major clinical outcomes.

Methods

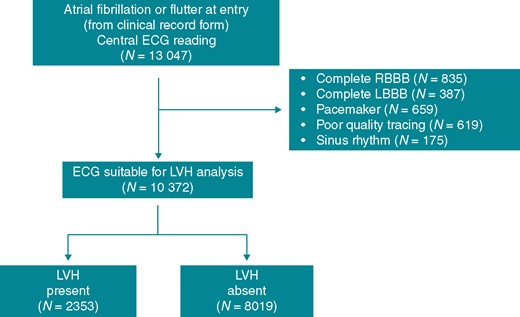

The RE-LY Study (NCT00262600) was a randomized non-inferiority trial of two doses of dabigatran, 110 mg bid and 150 mg bid, compared with warfarin for prevention of stroke or systemic embolism in patients with AF and at least one additional risk factor for stroke.13 Details of the study have been published.13,14 The authors of this study had full access to the data and designed the statistical analysis plan. We included patients with the diagnosis of AF on the ECG carried out at entry. We excluded those with conditions potentially interfering with the ECG interpretation for LVH, as well as patients in sinus rhythm (Figure 1) because the prognostic value of ECG LVH in patients in sinus rhythm is well established.

All patients had a 25 mm/sec 12-lead ECG at entry and then annually up to the final follow-up visit or premature discontinuation of the study. An expert reader blinded to the patients’ features and randomized treatment examined the baseline ECG tracings of all patients. We categorized LVH by ECG using a binary (yes/no) variable by one or both of the following15: (i) sum of the R wave in lead aVL and depth of the S wave in lead V3 > 2.0 mV in women and >2.4 mV in men and (ii) strain pattern in at least one of the following leads: I, II, aVL, or V4–V6. Strain pattern was considered present if there was ST-segment depression of at least 0.5 mm and inverted T wave in any of the above leads in the direction opposite the polarity of the QRS.

The primary outcome was a composite of stroke and systemic embolism. Other efficacy outcomes were all-cause stroke, all-cause death and vascular death. Safety outcomes were any bleedings, major bleedings and intracranial bleedings. All the above outcomes have been associated with ECG LVH in prior studies.16,17 Criteria used for definitions of events have been published.14 Deaths were adjudicated as being vascular or non-vascular, due to other specified causes such as cancer, or of unknown aetiology.

Data analysis

We used SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We present continuous data as mean (±standard deviation) and categorical data as frequencies. We compared the characteristics of patients with and without LVH in the three randomized groups by chi-squared test and analysis of variance. We categorized LVH as present or absent. We restricted analysis to the first event in those patients who experienced multiple events and limited the outcome measures to the primary RE-LY outcome (composite of stroke or systemic embolism), any stroke, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. We did not analyse systemic embolism alone because of the small number of events (10 with dabigatran 110 mg, 7 with dabigatran 150 mg, and 14 with warfarin). We used the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method to estimate the curves, and the log-rank test to compare the curves. We report the risk of events as a percentage per year, estimated by dividing the total number of patients with events by the total number of patient-years of follow-up for the randomized set. For analyses based on the safety set, the total number of years on treatment was used for the denominator. We used the Cox model to test the effect of prognostic factors on time to event.18 Separate analyses, with estimates of hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), were done for each of the two dabigatran doses (110 mg bid and 150 mg bid) vs. warfarin. In a multivariable analysis, we adjusted for the CHA2DS2VASc score19 (categorized as 0–1, 2, ≥ 3) and other covariables not included in the score. These were body mass index, valvular heart disease at entry, current smoking at entry, glomerular filtration rate, use of digoxin at entry, permanent AF at entry, randomized treatment, LVH, and LVH x treatment interaction. We used the CHA2DS2VASc score, in place of its seven components taken separately, because of its growing use in clinical practice and also to preserve model parsimony and prevent overfitting. We also made an additional analysis with the single components of the CHA2DS2VASc score, in addition to the covariables listed above. An exploratory analysis of the international normalized ratio (INR) and time in therapeutic range (TTR), defined by an INR between 2.0 and 3.0 in the warfarin group, was undertaken on the basis of all available individual observations. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study. Among 13 047 patients with AF or atrial flutter at entry as resulting from the clinical record form (CRF), and subjected to central ECG reading, 2675 patients were excluded due to the ECG being unsuitable for LVH analysis. The reasons of unsuitability are listed in Figure 1. These patients showed, when compared to those with suitable ECG (N = 10 372), a similar mean CHA2DS2VASc score (3.6 vs. 3.6) and a comparable history of diabetes (23.5% vs. 23.2%) and hypertension (79.8% vs. 78.2%). Age was marginally higher in the former than in the latter group (71.8 vs. 71.2 years; P < 0.01).

Flow diagram of the study. ECG, electrocardiography; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of patients. Prevalence of LVH was 22.7% (22.7% in the dabigatran 110 mg group, 22.9% in the dabigatran 150 mg group and 22.5% in the warfarin group). Patients with LVH showed, compared to those without LVH, a more frequent history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and heart failure, a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and a higher systolic blood pressure (BP). The CHA2DS2VASc score was shifted towards higher values in the group with LVH.

| . | All patients . | Dabigatran 110 mg bid . | Dabigatran 150 mg bid . | Warfarin . | P-value* . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 10 372 . | LVH − N = 2701 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH − N = 2666 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH – N = 2652 . | LVH + N = 771 . | ||

| Age (years) | 71.2 (9) | 71.1 (9) | 71.4 (9) | 71.3 (9) | 70.7 (10) | 71.5 (8) | 71.1 (9) | 0.2368 |

| Men (%) | 65.3 | 67.6 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 58.5 | 66.1 | 60.1 | < 0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 83 (20) | 85 (21) | 80 (19) | 84 (20) | 79 (20) | 84 (20) | 79 (19) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/(m)2) | 28.9 (6) | 29.2 (6) | 28.1 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.0 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.2 (6) | < 0.001 |

| CrCl (mL/min) | 73.6 (28) | 75.4 (29) | 69.4 (26) | 74.8 (28) | 69.0 (26) | 74.9 (27) | 67.8 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.0003 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 80.7 | 82.5 | 78.3 | 81.3 | 77.0 | 80.9 | 78.5 | |

| Asian | 18.3 | 16.7 | 21.1 | 18.0 | 21.5 | 18.1 | 19.8 | |

| Black | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | |

| Type of atrial fibrillation (%) | 0.0239 | |||||||

| Paroxysmal | 15.8 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 14.8 | |

| Persistent | 37.9 | 38.3 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 34.8 | 39.3 | 37.2 | |

| Permanent | 46.3 | 45.2 | 48.9 | 47.3 | 49.4 | 44.4 | 48.0 | |

| Medical history (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 78.2 | 76.5 | 80.5 | 79.0 | 78.3 | 77.8 | 80.2 | 0.0525 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23.2 | 21.8 | 26.0 | 22.9 | 26.3 | 21.5 | 28.5 | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 25.6 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 24.5 | 28.6 | 24.9 | 30.1 | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 33.1 | 29.9 | 45.4 | 29.2 | 47.4 | 28.5 | 46.7 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 13.3 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 15.6 | 0.2236 |

| Non CNS embolism | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.7157 |

| Current smoking | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 0.5355 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 130 (17) | 130 (17) | 133 (18) | 129 (16) | 132 (18) | 130 (17) | 132 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (10) | 78 (11) | 0.4170 |

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 76 (15) | 0.3384 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.1 (21) | 102.3 (24) | 98.9 (15) | 102.0 (26) | 97.9 (15) | 101.4 (17) | 98.4 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Medication use at entry (%) | ||||||||

| Antiplateletsa | 38.7 | 37.5 | 43.2 | 36.5 | 41.3 | 39.2 | 41.0 | 0.0003 |

| Digoxin | 34.6 | 30.5 | 51.6 | 29.7 | 48.3 | 29.6 | 51.5 | < 0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 62.2 | 62.7 | 60.4 | 62.8 | 65.5 | 61.0 | 61.6 | 0.7491 |

| ARBs or ACE inhibitors | 65.5 | 63.3 | 74.0 | 65.1 | 70.5 | 62.6 | 71.2 | < 0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 7.2 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 10.4 | 6.2 | 9.6 | < 0.001 |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 12.6 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 13.2 | 0.3953 |

| Statins | 41.8 | 42.3 | 41.6 | 41.6 | 39.9 | 42.8 | 38.9 | 0.0726 |

| Long term VKA Therapy | 70.1 | 71.4 | 66.8 | 71.3 | 66.9 | 70.5 | 66.3 | < 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score (%) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| 0–1 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 2.3 | |

| 2 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 14.5 | 22.4 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 16.3 | |

| ≥ 3 | 76.1 | 74.3 | 81.5 | 74.4 | 79.3 | 75.6 | 81.3 | |

| Electrocardiography | ||||||||

| R wave in aVL (mm) | 4.2 (3) | 3.7 (3) | 6.1 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | < 0.001 |

| S wave in V3 (mm) | 10.3 (6) | 9.2 (4) | 14.4 (7) | 9.0 (4) | 15 (7) | 9.1 (4) | 14.5 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Strain (%) | 16.6 | 0 | 72.9 | 0 | 73.7 | 0 | 72.6 | - |

| LV ejection fractionb | < 0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 40% (%) | 23.0 | 19.0 | 35.1 | 17.6 | 36.6 | 19.5 | 35.5 | |

| > 40% (%) | 77.0 | 81.0 | 64.9 | 82.4 | 63.4 | 80.5 | 64.5 | |

| . | All patients . | Dabigatran 110 mg bid . | Dabigatran 150 mg bid . | Warfarin . | P-value* . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 10 372 . | LVH − N = 2701 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH − N = 2666 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH – N = 2652 . | LVH + N = 771 . | ||

| Age (years) | 71.2 (9) | 71.1 (9) | 71.4 (9) | 71.3 (9) | 70.7 (10) | 71.5 (8) | 71.1 (9) | 0.2368 |

| Men (%) | 65.3 | 67.6 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 58.5 | 66.1 | 60.1 | < 0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 83 (20) | 85 (21) | 80 (19) | 84 (20) | 79 (20) | 84 (20) | 79 (19) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/(m)2) | 28.9 (6) | 29.2 (6) | 28.1 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.0 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.2 (6) | < 0.001 |

| CrCl (mL/min) | 73.6 (28) | 75.4 (29) | 69.4 (26) | 74.8 (28) | 69.0 (26) | 74.9 (27) | 67.8 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.0003 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 80.7 | 82.5 | 78.3 | 81.3 | 77.0 | 80.9 | 78.5 | |

| Asian | 18.3 | 16.7 | 21.1 | 18.0 | 21.5 | 18.1 | 19.8 | |

| Black | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | |

| Type of atrial fibrillation (%) | 0.0239 | |||||||

| Paroxysmal | 15.8 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 14.8 | |

| Persistent | 37.9 | 38.3 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 34.8 | 39.3 | 37.2 | |

| Permanent | 46.3 | 45.2 | 48.9 | 47.3 | 49.4 | 44.4 | 48.0 | |

| Medical history (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 78.2 | 76.5 | 80.5 | 79.0 | 78.3 | 77.8 | 80.2 | 0.0525 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23.2 | 21.8 | 26.0 | 22.9 | 26.3 | 21.5 | 28.5 | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 25.6 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 24.5 | 28.6 | 24.9 | 30.1 | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 33.1 | 29.9 | 45.4 | 29.2 | 47.4 | 28.5 | 46.7 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 13.3 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 15.6 | 0.2236 |

| Non CNS embolism | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.7157 |

| Current smoking | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 0.5355 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 130 (17) | 130 (17) | 133 (18) | 129 (16) | 132 (18) | 130 (17) | 132 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (10) | 78 (11) | 0.4170 |

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 76 (15) | 0.3384 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.1 (21) | 102.3 (24) | 98.9 (15) | 102.0 (26) | 97.9 (15) | 101.4 (17) | 98.4 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Medication use at entry (%) | ||||||||

| Antiplateletsa | 38.7 | 37.5 | 43.2 | 36.5 | 41.3 | 39.2 | 41.0 | 0.0003 |

| Digoxin | 34.6 | 30.5 | 51.6 | 29.7 | 48.3 | 29.6 | 51.5 | < 0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 62.2 | 62.7 | 60.4 | 62.8 | 65.5 | 61.0 | 61.6 | 0.7491 |

| ARBs or ACE inhibitors | 65.5 | 63.3 | 74.0 | 65.1 | 70.5 | 62.6 | 71.2 | < 0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 7.2 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 10.4 | 6.2 | 9.6 | < 0.001 |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 12.6 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 13.2 | 0.3953 |

| Statins | 41.8 | 42.3 | 41.6 | 41.6 | 39.9 | 42.8 | 38.9 | 0.0726 |

| Long term VKA Therapy | 70.1 | 71.4 | 66.8 | 71.3 | 66.9 | 70.5 | 66.3 | < 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score (%) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| 0–1 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 2.3 | |

| 2 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 14.5 | 22.4 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 16.3 | |

| ≥ 3 | 76.1 | 74.3 | 81.5 | 74.4 | 79.3 | 75.6 | 81.3 | |

| Electrocardiography | ||||||||

| R wave in aVL (mm) | 4.2 (3) | 3.7 (3) | 6.1 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | < 0.001 |

| S wave in V3 (mm) | 10.3 (6) | 9.2 (4) | 14.4 (7) | 9.0 (4) | 15 (7) | 9.1 (4) | 14.5 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Strain (%) | 16.6 | 0 | 72.9 | 0 | 73.7 | 0 | 72.6 | - |

| LV ejection fractionb | < 0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 40% (%) | 23.0 | 19.0 | 35.1 | 17.6 | 36.6 | 19.5 | 35.5 | |

| > 40% (%) | 77.0 | 81.0 | 64.9 | 82.4 | 63.4 | 80.5 | 64.5 | |

Continuous data are reported as mean (SD); categorical data as %.

LVH −, absence of left ventricular hypertrophy; LVH + , presence of left ventricular hypertrophy; bid, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; CrCl, creatinine clearance; CNS, central nervous system; BP, blood pressure; VKA, vitamin K antagonists; SD, standard deviation.

aspirin, clopidogrel, or dipyridamole.

by echocardiography, radionuclide study or angiography.

P-value based on t-test or χ2 test comparing patients with vs. without LVH.

| . | All patients . | Dabigatran 110 mg bid . | Dabigatran 150 mg bid . | Warfarin . | P-value* . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 10 372 . | LVH − N = 2701 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH − N = 2666 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH – N = 2652 . | LVH + N = 771 . | ||

| Age (years) | 71.2 (9) | 71.1 (9) | 71.4 (9) | 71.3 (9) | 70.7 (10) | 71.5 (8) | 71.1 (9) | 0.2368 |

| Men (%) | 65.3 | 67.6 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 58.5 | 66.1 | 60.1 | < 0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 83 (20) | 85 (21) | 80 (19) | 84 (20) | 79 (20) | 84 (20) | 79 (19) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/(m)2) | 28.9 (6) | 29.2 (6) | 28.1 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.0 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.2 (6) | < 0.001 |

| CrCl (mL/min) | 73.6 (28) | 75.4 (29) | 69.4 (26) | 74.8 (28) | 69.0 (26) | 74.9 (27) | 67.8 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.0003 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 80.7 | 82.5 | 78.3 | 81.3 | 77.0 | 80.9 | 78.5 | |

| Asian | 18.3 | 16.7 | 21.1 | 18.0 | 21.5 | 18.1 | 19.8 | |

| Black | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | |

| Type of atrial fibrillation (%) | 0.0239 | |||||||

| Paroxysmal | 15.8 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 14.8 | |

| Persistent | 37.9 | 38.3 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 34.8 | 39.3 | 37.2 | |

| Permanent | 46.3 | 45.2 | 48.9 | 47.3 | 49.4 | 44.4 | 48.0 | |

| Medical history (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 78.2 | 76.5 | 80.5 | 79.0 | 78.3 | 77.8 | 80.2 | 0.0525 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23.2 | 21.8 | 26.0 | 22.9 | 26.3 | 21.5 | 28.5 | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 25.6 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 24.5 | 28.6 | 24.9 | 30.1 | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 33.1 | 29.9 | 45.4 | 29.2 | 47.4 | 28.5 | 46.7 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 13.3 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 15.6 | 0.2236 |

| Non CNS embolism | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.7157 |

| Current smoking | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 0.5355 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 130 (17) | 130 (17) | 133 (18) | 129 (16) | 132 (18) | 130 (17) | 132 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (10) | 78 (11) | 0.4170 |

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 76 (15) | 0.3384 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.1 (21) | 102.3 (24) | 98.9 (15) | 102.0 (26) | 97.9 (15) | 101.4 (17) | 98.4 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Medication use at entry (%) | ||||||||

| Antiplateletsa | 38.7 | 37.5 | 43.2 | 36.5 | 41.3 | 39.2 | 41.0 | 0.0003 |

| Digoxin | 34.6 | 30.5 | 51.6 | 29.7 | 48.3 | 29.6 | 51.5 | < 0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 62.2 | 62.7 | 60.4 | 62.8 | 65.5 | 61.0 | 61.6 | 0.7491 |

| ARBs or ACE inhibitors | 65.5 | 63.3 | 74.0 | 65.1 | 70.5 | 62.6 | 71.2 | < 0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 7.2 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 10.4 | 6.2 | 9.6 | < 0.001 |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 12.6 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 13.2 | 0.3953 |

| Statins | 41.8 | 42.3 | 41.6 | 41.6 | 39.9 | 42.8 | 38.9 | 0.0726 |

| Long term VKA Therapy | 70.1 | 71.4 | 66.8 | 71.3 | 66.9 | 70.5 | 66.3 | < 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score (%) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| 0–1 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 2.3 | |

| 2 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 14.5 | 22.4 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 16.3 | |

| ≥ 3 | 76.1 | 74.3 | 81.5 | 74.4 | 79.3 | 75.6 | 81.3 | |

| Electrocardiography | ||||||||

| R wave in aVL (mm) | 4.2 (3) | 3.7 (3) | 6.1 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | < 0.001 |

| S wave in V3 (mm) | 10.3 (6) | 9.2 (4) | 14.4 (7) | 9.0 (4) | 15 (7) | 9.1 (4) | 14.5 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Strain (%) | 16.6 | 0 | 72.9 | 0 | 73.7 | 0 | 72.6 | - |

| LV ejection fractionb | < 0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 40% (%) | 23.0 | 19.0 | 35.1 | 17.6 | 36.6 | 19.5 | 35.5 | |

| > 40% (%) | 77.0 | 81.0 | 64.9 | 82.4 | 63.4 | 80.5 | 64.5 | |

| . | All patients . | Dabigatran 110 mg bid . | Dabigatran 150 mg bid . | Warfarin . | P-value* . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 10 372 . | LVH − N = 2701 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH − N = 2666 . | LVH + N = 791 . | LVH – N = 2652 . | LVH + N = 771 . | ||

| Age (years) | 71.2 (9) | 71.1 (9) | 71.4 (9) | 71.3 (9) | 70.7 (10) | 71.5 (8) | 71.1 (9) | 0.2368 |

| Men (%) | 65.3 | 67.6 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 58.5 | 66.1 | 60.1 | < 0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 83 (20) | 85 (21) | 80 (19) | 84 (20) | 79 (20) | 84 (20) | 79 (19) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/(m)2) | 28.9 (6) | 29.2 (6) | 28.1 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.0 (6) | 29.1 (6) | 28.2 (6) | < 0.001 |

| CrCl (mL/min) | 73.6 (28) | 75.4 (29) | 69.4 (26) | 74.8 (28) | 69.0 (26) | 74.9 (27) | 67.8 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.0003 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 80.7 | 82.5 | 78.3 | 81.3 | 77.0 | 80.9 | 78.5 | |

| Asian | 18.3 | 16.7 | 21.1 | 18.0 | 21.5 | 18.1 | 19.8 | |

| Black | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | |

| Type of atrial fibrillation (%) | 0.0239 | |||||||

| Paroxysmal | 15.8 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 14.8 | |

| Persistent | 37.9 | 38.3 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 34.8 | 39.3 | 37.2 | |

| Permanent | 46.3 | 45.2 | 48.9 | 47.3 | 49.4 | 44.4 | 48.0 | |

| Medical history (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 78.2 | 76.5 | 80.5 | 79.0 | 78.3 | 77.8 | 80.2 | 0.0525 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23.2 | 21.8 | 26.0 | 22.9 | 26.3 | 21.5 | 28.5 | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 25.6 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 24.5 | 28.6 | 24.9 | 30.1 | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 33.1 | 29.9 | 45.4 | 29.2 | 47.4 | 28.5 | 46.7 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 13.3 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 15.6 | 0.2236 |

| Non CNS embolism | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.7157 |

| Current smoking | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 0.5355 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 130 (17) | 130 (17) | 133 (18) | 129 (16) | 132 (18) | 130 (17) | 132 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (11) | 78 (10) | 78 (11) | 0.4170 |

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 77 (15) | 76 (15) | 0.3384 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.1 (21) | 102.3 (24) | 98.9 (15) | 102.0 (26) | 97.9 (15) | 101.4 (17) | 98.4 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Medication use at entry (%) | ||||||||

| Antiplateletsa | 38.7 | 37.5 | 43.2 | 36.5 | 41.3 | 39.2 | 41.0 | 0.0003 |

| Digoxin | 34.6 | 30.5 | 51.6 | 29.7 | 48.3 | 29.6 | 51.5 | < 0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 62.2 | 62.7 | 60.4 | 62.8 | 65.5 | 61.0 | 61.6 | 0.7491 |

| ARBs or ACE inhibitors | 65.5 | 63.3 | 74.0 | 65.1 | 70.5 | 62.6 | 71.2 | < 0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 7.2 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 10.4 | 6.2 | 9.6 | < 0.001 |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 12.6 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 13.2 | 0.3953 |

| Statins | 41.8 | 42.3 | 41.6 | 41.6 | 39.9 | 42.8 | 38.9 | 0.0726 |

| Long term VKA Therapy | 70.1 | 71.4 | 66.8 | 71.3 | 66.9 | 70.5 | 66.3 | < 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score (%) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| 0–1 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 2.3 | |

| 2 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 14.5 | 22.4 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 16.3 | |

| ≥ 3 | 76.1 | 74.3 | 81.5 | 74.4 | 79.3 | 75.6 | 81.3 | |

| Electrocardiography | ||||||||

| R wave in aVL (mm) | 4.2 (3) | 3.7 (3) | 6.1 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.9 (4) | < 0.001 |

| S wave in V3 (mm) | 10.3 (6) | 9.2 (4) | 14.4 (7) | 9.0 (4) | 15 (7) | 9.1 (4) | 14.5 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Strain (%) | 16.6 | 0 | 72.9 | 0 | 73.7 | 0 | 72.6 | - |

| LV ejection fractionb | < 0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 40% (%) | 23.0 | 19.0 | 35.1 | 17.6 | 36.6 | 19.5 | 35.5 | |

| > 40% (%) | 77.0 | 81.0 | 64.9 | 82.4 | 63.4 | 80.5 | 64.5 | |

Continuous data are reported as mean (SD); categorical data as %.

LVH −, absence of left ventricular hypertrophy; LVH + , presence of left ventricular hypertrophy; bid, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; CrCl, creatinine clearance; CNS, central nervous system; BP, blood pressure; VKA, vitamin K antagonists; SD, standard deviation.

aspirin, clopidogrel, or dipyridamole.

by echocardiography, radionuclide study or angiography.

P-value based on t-test or χ2 test comparing patients with vs. without LVH.

Outcome events

Median follow-up time was 2.0 years. During this period, 327 patients (3.2%) developed a primary outcome event, a composite of stroke or systemic embolism. Overall, there were 303 patients (2.9%) who developed a stroke, 261 patients experienced at least one ischaemic stroke and 47 a haemorrhagic stroke. Overall, 497 patients (4.8%) died of cardiovascular causes and 778 patients (7.5%) died from any cause (including cardiovascular causes).

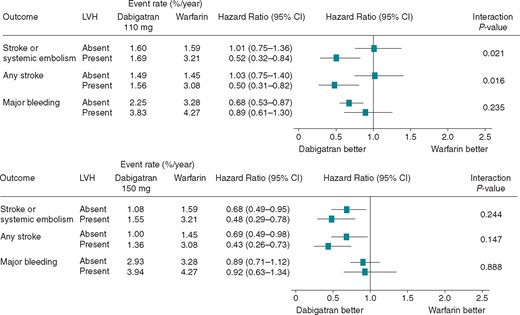

As shown in Table2 and Figure 2, in patients without LVH the rates of primary outcome were 1.59% per year with warfarin, 1.60% with dabigatran 110 mg (HR vs. warfarin 1.01, 95% CI 0.75–1.36; P = 0.95) and 1.08% with dabigatran 150 mg (HR vs. warfarin 0.68, 95% CI 0.49–0.95; P = 0.023). In patients with LVH, the rates of primary outcome were 3.21% per year with warfarin, 1.69% with dabigatran 110 mg (HR vs. warfarin 0.52, 95% CI 0.32–0.84) and 1.55% with dabigatran 150 mg (HR vs. warfarin 0.48, 95% CI 0.29–0.78).

For the primary RE-LY outcome, there was a significant interaction between LVH status and dabigatran 110 mg vs. warfarin (P = 0.021), while there was no significant interaction (P = 0.244) between LVH status and dabigatran 150 mg vs. warfarin.

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran 110 mg . | Dabigatran 150 mg . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | |||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 87 | 1.60 | 58 | 1.08 | 84 | 1.59 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) | 0.9504 | 0.0231 | 0.0215 | 0.2448 | |||

| Present | 26 | 1.69 | 24 | 1.55 | 48 | 3.21 | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.0076 | 0.0031 | ||||||

| Any stroke | Absent | 81 | 1.49 | 54 | 1.00 | 77 | 1.45 | 1.03 (0.75–1.40) | 0.69 (0.49–0.98) | 0.8724 | 0.0355 | 0.0162 | 0.1467 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.56 | 21 | 1.36 | 46 | 3.08 | 0.50 (0.31–0.82) | 0.43 (0.26–0.73) | 0.0062 | 0.0016 | ||||||

| All-cause death | Absent | 166 | 3.05 | 151 | 2.81 | 185 | 3.49 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) | 0.1938 | 0.0448 | 0.9329 | 0.7406 | |||

| Present | 88 | 5.73 | 88 | 5.69 | 100 | 6.70 | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.2783 | 0.2667 | ||||||

| Vascular death | Absent | 90 | 1.65 | 93 | 1.73 | 107 | 2.02 | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.85 (0.65–1.13) | 0.1595 | 0.2656 | 0.8121 | 0.5317 | |||

| Present | 69 | 4.49 | 60 | 3.88 | 78 | 5.22 | 0.86 (0.62–1.19) | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.3551 | 0.0819 | ||||||

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran 110 mg . | Dabigatran 150 mg . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | |||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 87 | 1.60 | 58 | 1.08 | 84 | 1.59 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) | 0.9504 | 0.0231 | 0.0215 | 0.2448 | |||

| Present | 26 | 1.69 | 24 | 1.55 | 48 | 3.21 | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.0076 | 0.0031 | ||||||

| Any stroke | Absent | 81 | 1.49 | 54 | 1.00 | 77 | 1.45 | 1.03 (0.75–1.40) | 0.69 (0.49–0.98) | 0.8724 | 0.0355 | 0.0162 | 0.1467 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.56 | 21 | 1.36 | 46 | 3.08 | 0.50 (0.31–0.82) | 0.43 (0.26–0.73) | 0.0062 | 0.0016 | ||||||

| All-cause death | Absent | 166 | 3.05 | 151 | 2.81 | 185 | 3.49 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) | 0.1938 | 0.0448 | 0.9329 | 0.7406 | |||

| Present | 88 | 5.73 | 88 | 5.69 | 100 | 6.70 | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.2783 | 0.2667 | ||||||

| Vascular death | Absent | 90 | 1.65 | 93 | 1.73 | 107 | 2.02 | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.85 (0.65–1.13) | 0.1595 | 0.2656 | 0.8121 | 0.5317 | |||

| Present | 69 | 4.49 | 60 | 3.88 | 78 | 5.22 | 0.86 (0.62–1.19) | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.3551 | 0.0819 | ||||||

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; CI, confidence interval; N, number of patients; yr, year; D, dabigatran.

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran 110 mg . | Dabigatran 150 mg . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | |||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 87 | 1.60 | 58 | 1.08 | 84 | 1.59 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) | 0.9504 | 0.0231 | 0.0215 | 0.2448 | |||

| Present | 26 | 1.69 | 24 | 1.55 | 48 | 3.21 | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.0076 | 0.0031 | ||||||

| Any stroke | Absent | 81 | 1.49 | 54 | 1.00 | 77 | 1.45 | 1.03 (0.75–1.40) | 0.69 (0.49–0.98) | 0.8724 | 0.0355 | 0.0162 | 0.1467 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.56 | 21 | 1.36 | 46 | 3.08 | 0.50 (0.31–0.82) | 0.43 (0.26–0.73) | 0.0062 | 0.0016 | ||||||

| All-cause death | Absent | 166 | 3.05 | 151 | 2.81 | 185 | 3.49 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) | 0.1938 | 0.0448 | 0.9329 | 0.7406 | |||

| Present | 88 | 5.73 | 88 | 5.69 | 100 | 6.70 | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.2783 | 0.2667 | ||||||

| Vascular death | Absent | 90 | 1.65 | 93 | 1.73 | 107 | 2.02 | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.85 (0.65–1.13) | 0.1595 | 0.2656 | 0.8121 | 0.5317 | |||

| Present | 69 | 4.49 | 60 | 3.88 | 78 | 5.22 | 0.86 (0.62–1.19) | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.3551 | 0.0819 | ||||||

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran 110 mg . | Dabigatran 150 mg . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | |||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 87 | 1.60 | 58 | 1.08 | 84 | 1.59 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) | 0.9504 | 0.0231 | 0.0215 | 0.2448 | |||

| Present | 26 | 1.69 | 24 | 1.55 | 48 | 3.21 | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.0076 | 0.0031 | ||||||

| Any stroke | Absent | 81 | 1.49 | 54 | 1.00 | 77 | 1.45 | 1.03 (0.75–1.40) | 0.69 (0.49–0.98) | 0.8724 | 0.0355 | 0.0162 | 0.1467 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.56 | 21 | 1.36 | 46 | 3.08 | 0.50 (0.31–0.82) | 0.43 (0.26–0.73) | 0.0062 | 0.0016 | ||||||

| All-cause death | Absent | 166 | 3.05 | 151 | 2.81 | 185 | 3.49 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) | 0.1938 | 0.0448 | 0.9329 | 0.7406 | |||

| Present | 88 | 5.73 | 88 | 5.69 | 100 | 6.70 | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.2783 | 0.2667 | ||||||

| Vascular death | Absent | 90 | 1.65 | 93 | 1.73 | 107 | 2.02 | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.85 (0.65–1.13) | 0.1595 | 0.2656 | 0.8121 | 0.5317 | |||

| Present | 69 | 4.49 | 60 | 3.88 | 78 | 5.22 | 0.86 (0.62–1.19) | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.3551 | 0.0819 | ||||||

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; CI, confidence interval; N, number of patients; yr, year; D, dabigatran.

Stroke rate (Figure 2) did not differ between the dabigatran 110 mg group and the warfarin group in the patients without LVH (1.49% vs. 1.45% per year), while it was considerably lower in the dabigatran 110 mg group than in the warfarin group in the patients with LVH (1.56% vs. 3.08% per year, P = 0.0062). For stroke, the interaction between LVH status and dabigatran 110 mg vs. warfarin was significant (P = 0.016), whereas the interaction between LVH status and dabigatran 150 mg vs. warfarin was not significant.

Interaction between left ventricular hypertrophy and effects of dabigatran vs. warfarin. CI, confidence interval; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

Neither all-cause death nor vascular death showed statistically significant interactions between LVH status and dabigatran 110 or 150 mg.

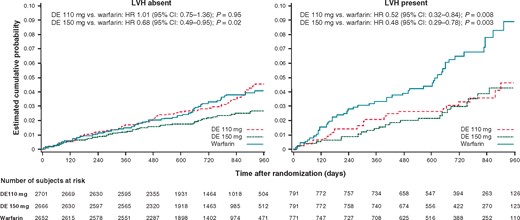

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier failure curves for the primary outcome in the three randomized groups for patients without and with LVH.

Cumulative incidence of the primary RE-LY study outcome in the three randomized groups in patients without (left panel) and with (right panel) left ventricular hypertrophy. CI, confidence interval; DE, dabigatran etexilate; HR, hazard ratio; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

Distribution of the time in therapeutic range in the warfarin group according to the absence or presence of left ventricular hypertrophy. LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

A multivariable model (Table 3) including the CHA2DS2VASc score, body mass index, valvular heart disease, current smoking, use of digoxin, permanent AF, randomized treatment and glomerular filtration rate as additional explanatory covariables, confirmed a significant interaction between LVH status and dabigatran 110 mg on the risk of primary outcome and any stroke. When the single components of the CHA2DS2VASc score entered the model in addition to the other covariables (Table 4), the significant interaction between LVH status and dabigatran 110 mg on the risk of primary outcome (P = 0.0362) and any stroke (P = 0.0247) was confirmed. In the above model, congestive heart failure showed an independent association with all-cause death (HR 1.61; 95% CI 1.34–1.93; P < 0.001) and vascular death (HR 2.02; 95% CI 1.61–2.55; P < 0.001), but not with the primary RE-LY outcome (P = 9196) and stroke (P = 0.9081) in the comparison between dabigatran 110 mg and warfarin.

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 0.8704 | 0.0246 | 0.69 (0.50–0.97) | 0.0329 | 0.2734 |

| Present | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.0106 | 0.50 (0.30–0.81) | 0.0053 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 0.1757 | 0.0309 | 0.70 (0.50–1.00) | 0.0494 | 0.1626 |

| Present | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) | 0.0903 | 0.45 (0.27–0.76) | 0.0026 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) | 0.1773 | 0.9953 | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.0471 | 0.5854 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.89 (0.66–1.18) | 0.4197 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.1595 | 0.7352 | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) | 0.3058 | 0.6656 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.78 (0.56–1.10) | 0.1611 | |||

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 0.8704 | 0.0246 | 0.69 (0.50–0.97) | 0.0329 | 0.2734 |

| Present | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.0106 | 0.50 (0.30–0.81) | 0.0053 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 0.1757 | 0.0309 | 0.70 (0.50–1.00) | 0.0494 | 0.1626 |

| Present | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) | 0.0903 | 0.45 (0.27–0.76) | 0.0026 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) | 0.1773 | 0.9953 | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.0471 | 0.5854 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.89 (0.66–1.18) | 0.4197 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.1595 | 0.7352 | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) | 0.3058 | 0.6656 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.78 (0.56–1.10) | 0.1611 | |||

Adjusted for CHA2DS2VASc score, body mass index, current smoking at entry, glomerular filtration rate, use of digoxin at entry, valvular heart disease at entry, permanent AF at entry, randomized treatment, LVH, treatment, LVH x treatment interaction.

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; D, dabigatran; AF, atrial fibrillation.

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 0.8704 | 0.0246 | 0.69 (0.50–0.97) | 0.0329 | 0.2734 |

| Present | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.0106 | 0.50 (0.30–0.81) | 0.0053 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 0.1757 | 0.0309 | 0.70 (0.50–1.00) | 0.0494 | 0.1626 |

| Present | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) | 0.0903 | 0.45 (0.27–0.76) | 0.0026 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) | 0.1773 | 0.9953 | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.0471 | 0.5854 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.89 (0.66–1.18) | 0.4197 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.1595 | 0.7352 | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) | 0.3058 | 0.6656 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.78 (0.56–1.10) | 0.1611 | |||

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 0.8704 | 0.0246 | 0.69 (0.50–0.97) | 0.0329 | 0.2734 |

| Present | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.0106 | 0.50 (0.30–0.81) | 0.0053 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 0.1757 | 0.0309 | 0.70 (0.50–1.00) | 0.0494 | 0.1626 |

| Present | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) | 0.0903 | 0.45 (0.27–0.76) | 0.0026 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) | 0.1773 | 0.9953 | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.0471 | 0.5854 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.89 (0.66–1.18) | 0.4197 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.1595 | 0.7352 | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) | 0.3058 | 0.6656 |

| Present | 0.86 (0.65–1.16) | 0.3238 | 0.78 (0.56–1.10) | 0.1611 | |||

Adjusted for CHA2DS2VASc score, body mass index, current smoking at entry, glomerular filtration rate, use of digoxin at entry, valvular heart disease at entry, permanent AF at entry, randomized treatment, LVH, treatment, LVH x treatment interaction.

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; D, dabigatran; AF, atrial fibrillation.

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.9500 | 0.0362 | 0.66 (0.47–0.92) | 0.0145 | 0.4186 |

| Present | 0.55 (0.34–0.89) | 0.0147 | 0.51 (0.31–0.84) | 0.0079 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.8453 | 0.0247 | 0.67 (0.47–0.95) | 0.0263 | 0.2409 |

| Present | 0.53 (0.32–0.86) | 0.0112 | 0.46 (0.28–0.78) | 0.0035 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.1374 | 0.9020 | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.0312 | 0.4560 |

| Present | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.3541 | 0.90 (0.68–1.21) | 0.4397 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.80 (0.60–1.05) | 0.1123 | 0.5388 | 0.84 (0.63–1.11) | 0.2163 | 0.7872 |

| Present | 0.91 (0.66–1.27) | 0.5821 | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 0.1715 | |||

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.9500 | 0.0362 | 0.66 (0.47–0.92) | 0.0145 | 0.4186 |

| Present | 0.55 (0.34–0.89) | 0.0147 | 0.51 (0.31–0.84) | 0.0079 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.8453 | 0.0247 | 0.67 (0.47–0.95) | 0.0263 | 0.2409 |

| Present | 0.53 (0.32–0.86) | 0.0112 | 0.46 (0.28–0.78) | 0.0035 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.1374 | 0.9020 | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.0312 | 0.4560 |

| Present | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.3541 | 0.90 (0.68–1.21) | 0.4397 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.80 (0.60–1.05) | 0.1123 | 0.5388 | 0.84 (0.63–1.11) | 0.2163 | 0.7872 |

| Present | 0.91 (0.66–1.27) | 0.5821 | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 0.1715 | |||

Adjusted for the single components of the CHA2DS2VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke, coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease, gender), body mass index, current smoking at entry, glomerular filtration rate, use of digoxin at entry, valvular heart disease at entry, permanent AF at entry, randomized treatment, LVH, treatment, LVH x treatment interaction.

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; D, dabigatran; AF, atrial fibrillation.

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.9500 | 0.0362 | 0.66 (0.47–0.92) | 0.0145 | 0.4186 |

| Present | 0.55 (0.34–0.89) | 0.0147 | 0.51 (0.31–0.84) | 0.0079 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.8453 | 0.0247 | 0.67 (0.47–0.95) | 0.0263 | 0.2409 |

| Present | 0.53 (0.32–0.86) | 0.0112 | 0.46 (0.28–0.78) | 0.0035 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.1374 | 0.9020 | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.0312 | 0.4560 |

| Present | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.3541 | 0.90 (0.68–1.21) | 0.4397 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.80 (0.60–1.05) | 0.1123 | 0.5388 | 0.84 (0.63–1.11) | 0.2163 | 0.7872 |

| Present | 0.91 (0.66–1.27) | 0.5821 | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 0.1715 | |||

| . | LVH . | Hazard Ratio . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P value for interaction . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | P-value . | P-value for interaction . | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | Absent | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.9500 | 0.0362 | 0.66 (0.47–0.92) | 0.0145 | 0.4186 |

| Present | 0.55 (0.34–0.89) | 0.0147 | 0.51 (0.31–0.84) | 0.0079 | |||

| Any stroke | Absent | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.8453 | 0.0247 | 0.67 (0.47–0.95) | 0.0263 | 0.2409 |

| Present | 0.53 (0.32–0.86) | 0.0112 | 0.46 (0.28–0.78) | 0.0035 | |||

| All-cause death | Absent | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.1374 | 0.9020 | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.0312 | 0.4560 |

| Present | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.3541 | 0.90 (0.68–1.21) | 0.4397 | |||

| Vascular death | Absent | 0.80 (0.60–1.05) | 0.1123 | 0.5388 | 0.84 (0.63–1.11) | 0.2163 | 0.7872 |

| Present | 0.91 (0.66–1.27) | 0.5821 | 0.79 (0.56–1.11) | 0.1715 | |||

Adjusted for the single components of the CHA2DS2VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke, coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease, gender), body mass index, current smoking at entry, glomerular filtration rate, use of digoxin at entry, valvular heart disease at entry, permanent AF at entry, randomized treatment, LVH, treatment, LVH x treatment interaction.

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; D, dabigatran; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Table 5 summarizes the bleeding events in the population. The risk of any bleeding, major bleeding and intracranial bleeding did not show any statistically significant interaction with the LVH status in the comparison of dabigatran 110 mg, or dabigatran 150 mg, vs. warfarin.

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran . | Dabigatran . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 110 mg . | 150 mg . | . | . | . | interaction . | ||||||

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | ||

| Any bleeding | Absent | 760 | 15.8 | 798 | 17.1 | 941 | 19.4 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.996 |

| Present | 181 | 13.9 | 232 | 17.9 | 271 | 20.3 | 0.63 (0.53–0.77) | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) | 0.001 | 0.067 | |||

| Major bleeding | Absent | 108 | 2.2 | 137 | 2.9 | 159 | 3.3 | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.002 | 0.307 | 0.235 | 0.888 |

| Present | 50 | 3.8 | 51 | 3.9 | 57 | 4.3 | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 0.553 | 0.669 | |||

| Intracranial bleeding | Absent | 7 | 0.15 | 14 | 0.3 | 34 | 0.7 | 0.21 (0.09–0.46) | 0.42 (0.23–0.79) | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.764 | 0.976 |

| Present | 4 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.2 | 0.26 (0.09–0.77) | − | 0.015 | − | |||

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran . | Dabigatran . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 110 mg . | 150 mg . | . | . | . | interaction . | ||||||

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | ||

| Any bleeding | Absent | 760 | 15.8 | 798 | 17.1 | 941 | 19.4 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.996 |

| Present | 181 | 13.9 | 232 | 17.9 | 271 | 20.3 | 0.63 (0.53–0.77) | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) | 0.001 | 0.067 | |||

| Major bleeding | Absent | 108 | 2.2 | 137 | 2.9 | 159 | 3.3 | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.002 | 0.307 | 0.235 | 0.888 |

| Present | 50 | 3.8 | 51 | 3.9 | 57 | 4.3 | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 0.553 | 0.669 | |||

| Intracranial bleeding | Absent | 7 | 0.15 | 14 | 0.3 | 34 | 0.7 | 0.21 (0.09–0.46) | 0.42 (0.23–0.79) | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.764 | 0.976 |

| Present | 4 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.2 | 0.26 (0.09–0.77) | − | 0.015 | − | |||

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; N, number of patients; yr, year; D, dabigatran; CI, confidence interval.

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran . | Dabigatran . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 110 mg . | 150 mg . | . | . | . | interaction . | ||||||

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | ||

| Any bleeding | Absent | 760 | 15.8 | 798 | 17.1 | 941 | 19.4 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.996 |

| Present | 181 | 13.9 | 232 | 17.9 | 271 | 20.3 | 0.63 (0.53–0.77) | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) | 0.001 | 0.067 | |||

| Major bleeding | Absent | 108 | 2.2 | 137 | 2.9 | 159 | 3.3 | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.002 | 0.307 | 0.235 | 0.888 |

| Present | 50 | 3.8 | 51 | 3.9 | 57 | 4.3 | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 0.553 | 0.669 | |||

| Intracranial bleeding | Absent | 7 | 0.15 | 14 | 0.3 | 34 | 0.7 | 0.21 (0.09–0.46) | 0.42 (0.23–0.79) | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.764 | 0.976 |

| Present | 4 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.2 | 0.26 (0.09–0.77) | − | 0.015 | − | |||

| . | LVH . | Dabigatran . | Dabigatran . | Warfarin . | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) . | P-value . | P-value . | P-value for . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 110 mg . | 150 mg . | . | . | . | interaction . | ||||||

| N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | N . | %/yr . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | D 110 mg vs. warfarin . | D 150 mg vs. warfarin . | ||

| Any bleeding | Absent | 760 | 15.8 | 798 | 17.1 | 941 | 19.4 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.996 |

| Present | 181 | 13.9 | 232 | 17.9 | 271 | 20.3 | 0.63 (0.53–0.77) | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) | 0.001 | 0.067 | |||

| Major bleeding | Absent | 108 | 2.2 | 137 | 2.9 | 159 | 3.3 | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.002 | 0.307 | 0.235 | 0.888 |

| Present | 50 | 3.8 | 51 | 3.9 | 57 | 4.3 | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 0.553 | 0.669 | |||

| Intracranial bleeding | Absent | 7 | 0.15 | 14 | 0.3 | 34 | 0.7 | 0.21 (0.09–0.46) | 0.42 (0.23–0.79) | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.764 | 0.976 |

| Present | 4 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.2 | 0.26 (0.09–0.77) | − | 0.015 | − | |||

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; N, number of patients; yr, year; D, dabigatran; CI, confidence interval.

International normalized ratio in the warfarin group

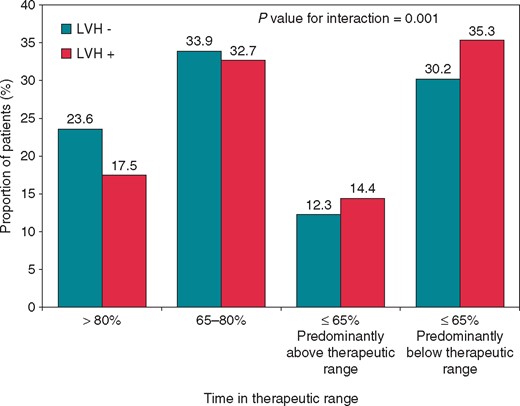

Information on INR in the warfarin group was available in 3305 patients (97%) and missing in 118. The mean TTR in the warfarin group was 64.6%. The proportion of patients with TTR below the mean was higher in the presence than in the absence of LVH (48.8% vs. 41.8%; P = 0.0008). To further explore this finding, we defined four groups on the basis of TTR: (i) TTR > 80% (n = 734; 22%); (ii) TTR 65–80% (n = 1111; 34%); (iii) TTR ≤ 65%, but predominantly above the therapeutic range (n = 423; 13%); (iv) TTR ≤ 65% but predominantly below the therapeutic range (n = 1037; 31%). As shown in Figure 4, LVH was associated with a poorer INR control, as reflected by the significant interaction (P = 0.001) between TTR and LVH status in the warfarin group.

Discussion

The present post-hoc analysis of the RE-LY study showed two main findings. First, the primary RE-LY outcome (stroke and systemic embolism) was two-fold more frequent in the patients with than in those without LVH in the warfarin group. Conversely, the excess risk associated with LVH was smaller or negligible in the two dabigatran groups. Second, LVH was associated with a poorer INR control in the warfarin group. Consequently, the lower dose of dabigatran was superior to warfarin in reducing the primary RE-LY outcome in patients with LVH, while the higher dose of dabigatran remained superior to warfarin regardless of LVH. The interaction of LVH status with the effects of dabigatran 110 mg vs. warfarin was thus largely explained by the poorer performance of warfarin in patients with LVH.

We defined LVH by traditional ECG using a validated score (‘Perugia score’) which improved cardiovascular risk stratification in patients with1 and without20 AF. The added prognostic value of ECG-LVH in patients with evidence of AF on the ECG at entry is supported by a prior analysis of RE-LY, in which ECG-LVH improved risk stratification and discrimination in AF patients over and beyond the CHA2DS2VASc score and other risk markers.1

The mechanisms of the higher thrombotic risk in patients with LVH and exposed to warfarin, but not to dabigatran, remain uncertain. LVH is believed to reflect and integrate, in a variety of clinical conditions, the long-term detrimental effects of several cardiovascular risk factors, mainly arterial hypertension.21 In a post-hoc analysis of the RE-LY study, the relative benefits of dabigatran vs. warfarin were similar in patients with and without hypertension.22 However, the relative benefit of dabigatran 110 mg vs. warfarin on the risk of the primary RE-LY outcome bordered statistical significance in hypertensive patients (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.65–1.02; P for interaction = 0.0547), while the benefit of dabigatran 150 mg vs. warfarin was statistically significant in patients with and without hypertension (P for interaction = 0.6207).22

Less clear is the direct relation between LVH and coagulation. Lip and co-workers first showed increased levels of fibrinogen, and an association between fibrinogen and left ventricular mass (LVM), in hypertensive patients.3 Other reports confirmed a link between LVH and enhanced coagulation. In a study of 230 anticoagulated patients who underwent transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) prior to cardioversion or catheter ablation of AF, LVH and persistent AF were the only two independent predictors of left atrial thrombus.2 In another study of 123 anticoagulated patients with AF who underwent TEE, left atrial thrombi were noted in 33% of patients with LVH, as opposed to 13% of patients without LVH (P < 0.001).7 In a study of 129 anticoagulated patients with AF who underwent TEE, LVM was the only parameter predictive of left atrial thrombus (P < 0.001) in a multivariate logistic model.6

It remains unclear why the adverse prognostic impact of LVH in the present study was greater in the warfarin group than in the two dabigatran groups. In the warfarin group, patients with LVH showed a poorer control of INR than those without LVH, thereby justifying their higher risk of thromboembolism.23 In a study conducted in 2223 anticoagulated patients with non-valvular AF, for any 10% increase in the time with INR out of range there was a 29% higher risk of mortality (P < 0.001), a 10% higher risk of ischaemic stroke (P = 0.006) and a 12% higher risk of other thromboembolic events.24

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that LVH is associated with a moderately poorer control of INR in patients with non-valvular AF receiving warfarin. LVH might be a marker for a poor adherence not only to antihypertensive treatment, as reflected by the higher BP values associated with LVH (Table 1), but also to warfarin, as reflected by the lower TTR. However, the poorer control of INR appears to be unable to fully explain the two-fold higher risk of the primary outcome and stroke in the LVH group. The design of the present study does not allow us to clarify the pathological mechanisms of this phenomenon. LVH may be associated with overt or subclinical heart failure.25 The decrease in oxygen delivery to the liver, potentially associated with episodes of heart failure, might impair the hepatic clearance of warfarin via cytochrome P450, known to require a considerable amount of oxygen to perform oxidative reactions.26 This intriguing hypothesis is supported by the evidence that patients admitted to hospital for exacerbations of heart failure show INR instability and enhanced sensitivity to warfarin.27 An enhanced sensitivity to warfarin in the acute phase of heart failure might lead to difficulties in the management of INR even in the long term. In contrast, the elimination of dabigatran, which is predominantly renal, would be less affected by episodes of heart failure associated with LVH. Consequently, the antithrombotic potential of dabigatran could be less impaired by LVH when compared with warfarin. We included the CHA2DS2VASc score, which encompasses congestive heart failure, in the multivariate model comparing the treatments and testing their interaction with LVH status. Our results did not change when the single components of the CHA2DS2VASc score were forced into the multivariate analysis.

LVH may be associated not only with disorders of coagulation, but also with a state of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation.4,5 Thrombin participates in the mechanisms of inflammation and fibrosis.8–10 There is experimental evidence that inflammatory and fibrotic reactions may be counteracted by selective thrombin blockade with dabigatran.11,12 Studies in humans are needed to clarify whether selective thrombin blockade offers an advantage over warfarin in a context of systemic inflammation.

Limitations of the study

Firstly, stemming from an unanticipated post-hoc analysis, our findings should not be viewed as definitive, but rather as hypothesis-generating and subjected to the play of chance. Secondly, our study lacks imaging assessment of LVH, which could have resulted in better precision. An echocardiographic study was not systematically performed in the RE-LY trial. To the best of our knowledge, none of the other mega-trials with oral non vitamin K antagonists vs. warfarin have sufficient echocardiographic information to test the link between baseline LVM and outcome. Such association should be addressed in future studies. Thirdly, our investigation has been specifically conducted in the RE-LY patients with ECG evidence of AF at entry, not in the entire RE-LY population. We pre-specified this aspect in order to make results applicable to patients with actual evidence of AF on the index ECG, regardless of the type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent or permanent), because the prognostic value of LVH in patients with sinus rhythm on the ECG tracings is well established. Finally, the difference in TTR between the patients with and without LVH in the warfarin group was numerically small, albeit statistically significant. The strength of this study was that all ECG tracings were examined by a single experienced reader in blind conditions with regard to clinical features and randomized treatment. Because of the high number of ECG tracings which required manual reading (n = 13 047), we could not rely on a higher number of readers for assessment of interpersonal variability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study suggests that LVH on ECG portends a reduced antithrombotic efficacy of warfarin, but not dabigatran, in patients with ECG evidence of AF. Consequently, the lower dose of dabigatran (110 mg) was better than warfarin in reducing the risk of primary RE-LY outcome and stroke in AF patients with LVH. The higher dose of dabigatran (150 mg) was superior to warfarin regardless of LVH status.

Conflict of interest: Dr Verdecchia and Dr Di Pasquale received research grants, consulting fees, and lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr Connolly has received consulting and research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr Ezekowitz is a consultant for and/or has received consulting/honoraria fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Portola, Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Aegerion, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pozen Inc., Amgen, Coherex, and Armetheon. Dr Yusuf has received research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr Wallentin has received research grants, consultancy and lecture fees, honoraria, and travel support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline; research grants, consultancy and lecture fees, and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim; research grants and consultancy fees from Merck & Co.; and consultancy fees from Abbott, Athera Biotechnologies, and Regado Biosciences. Dr Lip is a consultant for Bayer/Janssen, Astellas, Merck, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Biotronik, Medtronic, Portola, Boehringer Ingelheim, Microlife and Daiichi-Sankyo. Dr Lip is a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Microlife, Roche and Daiichi-Sankyo. Eva Kleine and Martina Brueckmann are full-time employees of Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH & Co. KG, Germany. The other authors report no conflicts.

Funding

The RE-LY study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany. This analysis was funded by the Fondazione Umbra Cuore e Ipertensione – ONLUS, Perugia, Italy.

References