-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrew D. Krahn, Carlos A. Morillo, Teresa Kus, Braden Manns, Sarah Rose, Michele Brignole, Robert S. Sheldon, Empiric pacemaker compared with a monitoring strategy in patients with syncope and bifascicular conduction block—rationale and design of the Syncope: Pacing or Recording in ThE Later Years (SPRITELY) study, EP Europace, Volume 14, Issue 7, July 2012, Pages 1044–1048, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eus005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study seeks to identify the optimal management strategy for patients with syncope in the context of bifascicular block and preserved left ventricular systolic function.

This multicentre, randomized, open label, parallel group pragmatic randomized trial will test the hypothesis that a strategy of empiric permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with syncope and bifascicular heart block improves future outcome more effectively than a strategy of therapy guided by prolonged monitoring with an implantable loop recorder (ILR). A total of 120 patients with bifascicular block, preserved left ventricular function, and ≥1 syncopal spell in the preceding year will be randomized to receive a permanent pacemaker or ILR in at least 20 centres in Canada, the USA, Asia, and Europe. The primary outcome measure will be a composite of Major Adverse Study-Related Events (MASRE) in a 2-year observation period, wherein the events are death, syncope, symptomatic bradycardia, asymptomatic diagnostic bradycardia, and acute and chronic device complications. Prespecified secondary endpoints will include syncope symptoms, quality of life, and economic burden.

This trial will provide high-level and generalizable evidence for the use of either permanent pacing or implantable loop recorders as a first line intervention for patients with syncope, preserved systolic function, and bifascicular block.

Introduction

Syncope is a complex clinical syndrome with a lifetime prevalence approaching 50%.1,2 There is a substantially impaired quality of life in all dimensions of health, particularly in terms of mobility, usual activities, and self-care.3–5 Quality of life returns to normal within 6 months if syncope frequency is reduced. Syncope in the USA accounts for over $2.4 billion USD yearly in direct health costs.6

The potential aetiology of syncope is broad, as are the characteristics of the population it affects. Patients can faint in the presence or absence of structural heart disease. The patient population of interest in the current study is comprised of patients >50 years of age who have a physiological finding that is a plausible but unproven cause of their syncope. The most common causes of syncope in older patients with preserved left ventricular function include intermittent complete heart block, vasovagal syncope, supraventricular tachyarrhythmias including bradycardia tachycardia syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, and carotid sinus syncope.7 Of these, orthostatic hypotension does not usually pose a diagnostic challenge, and carotid sinus syncope is usually treated with a pacemaker. Intermittent complete heart block, once it has been recorded and therefore is clinically evident, can be treated effectively with a pacemaker. However, the optimum approach to the patient with bifascicular block and syncope has not been established, nor has there been a randomized trial in such patients.

Study summary

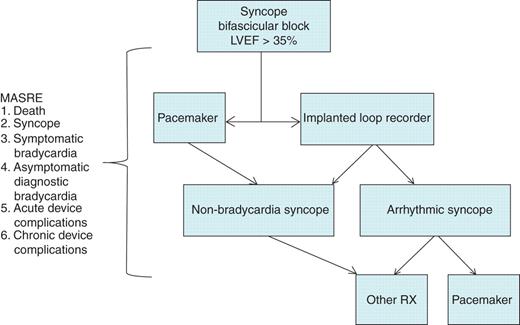

The Syncope: Pacing or Recording in ThE Later Years (SPRITELY) trial will test the hypothesis that a strategy of empiric permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with syncope and bifascicular heart block will prevent syncope recurrences and major clinical events more effectively than a strategy of therapy guided by prolonged monitoring with an implantable loop recorder (ILR). A total of 120 patients with bifascicular block, preserved left ventricular function, and ≥1 syncopal spell in the preceding year will be randomized to receive a permanent pacemaker or ILR in an open-label, parallel group study. The study is designed to capture the major clinical events that might arise following the decision to implant either device, and is a pragmatic clinical trial. Accordingly, the primary outcome measure will be a composite of major adverse study-related events (MASRE) in a 2-year observation period, where the events will be death, syncope, symptomatic bradycardia, asymptomatic diagnostic bradycardia, and acute and chronic device complications (Figure 1).

Algorithm summarizing the SPRITELY study. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MASRE, major adverse study related events; Rx, therapy.

Rationale

The incremental value of empiric pacemaker implantation over an ILR-driven monitoring strategy with symptom/rhythm recurrence-driven therapy delivery will be tested in the SPRITELY study. The prevalence of bifascicular block in syncope patients can be estimated from three reports based on emergency room patients. The proportion of patients with syncope that emergency room physicians and consultants deemed to be due to presumed or known intermittent complete heart block is 4.9%, and to sick sinus syndrome is 1.3%.8–10 Since syncope has been estimated to be responsible for 1–3% of emergency room visits, a conservative estimate of 1.5% can be used to estimate the annual proportion of emergency room patients with a presentation of syncope with intermittent complete heart block. This then is not a rare presentation, with a conservatively estimated 74 of 100 000 emergency visits per year for patients with syncope and bifascicular block (1.5% with syncope × 4.9% of syncope × 100 000).

Several studies have reported the rate of progression of asymptomatic bifascicular block to symptomatic high-grade or complete heart block. All studies included patients with a variety of electrical and structural heart diseases, and methodological differences prevent firm conclusions from pooled data. However, the rate of progression in all subjects (not just those who have previous syncope) to complete heart block appears to be in the range of 1–4% per year, and symptomatic patients with prolonged His-to-ventricle intervals are at higher risk of progression.11–14

Two previous studies have estimated the proportion of patients with syncope and bifascicular block whose syncope may be attributed to intermittent complete heart block. Donateo et al.15 investigated 55 patients with syncope and bundle branch block, and estimated that 20 (36%) would have intermittent atrioventricular (AV) block, 2 (4%) would have sick sinus syndrome, and 15 (27%) had tilt test-positive vasovagal syncope. These estimates were not based on prospectively defined outcome data collection, but did suggest that 40% of patients might benefit from pacemaker implantation. The likelihood of complete heart block as an outcome can be estimated from the ISSUE observational study.16 The ISSUE investigators implanted loop recorders in 52 patients with syncope with bifascicular block and negative electrophysiological testing and moderate or no structural heart disease. The results illustrate the markedly worse outcome for patients with syncope compared with previously reported asymptomatic patients. Over a follow-up of 3–15 months, syncope recurred in 22 patients (42%), the event being documented in 19 patients after a median of only 48 days. These included complete heart block in 24%, sinus arrest in 8%, and undefined asystole in 2%, for a total of 34%. Another 6% developed stable complete heart block, and 4% had presyncope due to transient complete heart block. Syncope without a rhythm disturbance occurred in 4%, similar to an estimate of 10.8% modelled from the Donateo data. Thus, the progression to a pacing indication was 44% in 2 years. The ISSUE study is the only series to report documented outcomes,16 rather than baseline diagnoses, and therefore it was used for outcome estimates for pacemaker indications and power calculations in this study. This study also diminished previous enthusiasm for electrophysiological testing in patients with syncope and conduction system disease.

Both US and European guidelines state that syncope and bifascicular block is a Class IIA indication for pacing, implying that it is reasonable but not necessary to perform the intervention.17,18 Of note, the European Heart Rhythm Association states that an ILR for syncope and bifascicular block is also a Class IIA indication, indicating the equipoise that supports the conduct of the current study.19

Patients with syncope and structural heart disease are at risk of life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Those with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <35% should be considered for implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapy for the purpose of primary prevention of sudden death, and will not be included in the study. The ISSUE 1 study showed that those with LVEF > 35% and a negative electrophysiological study have a very low risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and no sudden death in the 24 months of follow-up.20 Accordingly, patients with structural heart disease and LVEF > 35% will undergo programmed electrical stimulation for the purposes of determining whether ventricular tachycardia (VT) is inducible. We will exclude patients who have either a standard indication for a pacemaker or an ICD, and those with inducible sustained monomorphic at protocol-mandated electrophysiological study. Conversely, patients with syncope and an ejection fraction >35% who undergo electrophysiological study will be included in the study if the His-to-ventricle time is markedly prolonged (>100 ms) because this is only a risk factor for conduction disease progression, not a diagnostic finding, and as a result is a Class IIA indication for pacing. Ultimately, this decision will be left to the implanting sites. This is anticipated to be a very small proportion of the recruited patient population.

Study objective

Recognizing the existence of competing causes of syncope, the objective is to determine whether patients with syncope and bifascicular block but not documented complete heart block should be paced empirically, or be subjected to further attempts at clarifying the mechanism causing syncope.

Study design

The SPRITELY study evaluates two competing interventional strategies for patients with syncope and bifascicular block after baseline risk stratification to exclude those with an LVEF < 35%. The first strategy involves empiric implantation of a pacemaker, and the second involves insertion of an ILR, then acting appropriately on the results. The goal of the pacemaker strategy is to empirically treat syncope that might be due to intermittent complete AV block, while the goal of the ILR strategy is to treat most appropriately, according to the true cause of syncope based on symptom rhythm correlation. Patients with recurrent syncope with documented complete AV block on ILR tracings will receive a pacemaker. As well, less symptomatic bradycardia that suggests that complete heart block is the cause of syncope will usually lead to a decision to implant a pacemaker. This strategy has the advantage of limiting the morbidity and mortality of pacemaker implantation and follow-up to those who have a documented need for one.

Inclusion

Patients will be eligible if they have:

≥1 syncopal spell within 1 year preceding enrolment;

bifascicular block on a 12-lead ECG (electrocardiogram) (includes left bundle branch block, or right bundle branch block and left anterior or posterior fascicular block; PR interval prolongation is not a criterion);

age≥50 years;

provide written informed consent.

Exclusion

Patients will be excluded if they have:

previous pacemaker, ICD, or ILR;

ACC/AHA/HRS/ESC Class I indication for permanent pacing or ICD implantation;17,18

left ventricular ejection fraction <35%;

contraindication to a transvenous pacemaker such as mechanical tricuspid valve or active sepsis;

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy;

documented sustained VT;

inducible, sustained monomorphic VT on EP study;

myocardial infarction within 3 months prior to enrolment;

a major chronic co-morbid medical condition that would preclude 24 months of follow-up;

a reversible cause of fascicular block.

Screening and enrolment

Syncope will be defined based on a structured history using a standardized form.21–24 A total of at least 20 centres will enrol 120 patients, with targeted enrolment completion in 3 years. All patients will be followed every 6 months for 2 years. All centres will have approval by their local ethics review boards, and will be required to report all adverse events.

Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations

Treatment with pacemaker or ILR implantation will occur ≤2 weeks after enrolment, according to local practice and the manufacturer's instructions for standard use and techniques. Either a single- or dual-chamber pacemaker will be permitted according to local practice unless the patient is in chronic atrial fibrillation, in which case a single-chamber pacemaker will be utilized.17,18

The pacemaker configuration will be at the discretion of the investigator. Single-chamber ventricular pacemakers will be programmed to VVI 50 b.p.m. Dual-chamber pacemaker programming will be to DDD mode (50–120) with mode switch and pacing avoidance algorithms on. The rate drop feature will not be activated. The ILR will be programmed for automatic detection using settings of low heart rate <50 b.p.m., high heart rate >165 b.p.m., and pause >3 s. Patients and family members will be instructed in the use of the device. All medications and medication changes will be recorded, in keeping with other syncope treatment studies.25,26

Endpoints

The primary outcome will be a composite of major adverse study-related events in a 2-year observation period (MASRE, Table 1). MASRE will capture the major consequences ensuing from both strategies in patients with syncope and bifascicular block, including (i) syncope, (ii) symptomatic bradycardias, (iii) asymptomatic complete heart block, (iii) acute and chronic pacemaker and ILR complications, and (iiv) cardiovascular death. The primary outcome analysis will be on a per-event basis, not per-subject basis. Therefore, all events will be captured, including multiple types of events in each subject. Secondary outcome measures will include total number of syncopal spells, the time to the first recurrence of syncope, and the physical trauma due to syncope. In addition, quality of life, syncope symptom scores, and economic analyses are planned. Complications can occur after 2 years, but are beyond the purview of the study, as currently written and funded.

| MASRE outcome . | Pacemaker arm . | ILR arm . |

|---|---|---|

| First vasovagal spell | 0.074 | 0.074 |

| Vasovagal recurrences | 0.148 | 0.148 |

| Diagnostic bradycardia (online Appendix 1) | 0 | 0.44 |

| Pacemaker acute complications | 0.046 | 0.02024 |

| PM chronic complications | 0.032 | 0.00704 |

| ILR acute complications | 0 | 0.014 |

| ILR chronic complications | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0.3 | 0.71 |

| MASRE outcome . | Pacemaker arm . | ILR arm . |

|---|---|---|

| First vasovagal spell | 0.074 | 0.074 |

| Vasovagal recurrences | 0.148 | 0.148 |

| Diagnostic bradycardia (online Appendix 1) | 0 | 0.44 |

| Pacemaker acute complications | 0.046 | 0.02024 |

| PM chronic complications | 0.032 | 0.00704 |

| ILR acute complications | 0 | 0.014 |

| ILR chronic complications | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0.3 | 0.71 |

The conditional probabilities account for all potential MASRE outcomes following an intention to use either of the strategies, including those resulting from crossing over to the other strategy.

MASRE, major adverse study-related events; ILR, implantable loop recorder; PM, pacemaker.

| MASRE outcome . | Pacemaker arm . | ILR arm . |

|---|---|---|

| First vasovagal spell | 0.074 | 0.074 |

| Vasovagal recurrences | 0.148 | 0.148 |

| Diagnostic bradycardia (online Appendix 1) | 0 | 0.44 |

| Pacemaker acute complications | 0.046 | 0.02024 |

| PM chronic complications | 0.032 | 0.00704 |

| ILR acute complications | 0 | 0.014 |

| ILR chronic complications | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0.3 | 0.71 |

| MASRE outcome . | Pacemaker arm . | ILR arm . |

|---|---|---|

| First vasovagal spell | 0.074 | 0.074 |

| Vasovagal recurrences | 0.148 | 0.148 |

| Diagnostic bradycardia (online Appendix 1) | 0 | 0.44 |

| Pacemaker acute complications | 0.046 | 0.02024 |

| PM chronic complications | 0.032 | 0.00704 |

| ILR acute complications | 0 | 0.014 |

| ILR chronic complications | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0.3 | 0.71 |

The conditional probabilities account for all potential MASRE outcomes following an intention to use either of the strategies, including those resulting from crossing over to the other strategy.

MASRE, major adverse study-related events; ILR, implantable loop recorder; PM, pacemaker.

Data collection is based on web-based data acquisition and storage from the Data Coordination Centre at the Libin Cardiovascular Institute in Calgary. A central Outcomes Adjudication Committee will adjudicate all outcomes unblinded, and the subsequent data will be analysed blindly. Ethical approval will be obtained at all sites, and study safety will be monitored by a Data Safety Management Committee composed of members not involved in the study.

Statistical considerations

The estimates of MASRE outcomes are presented in Appendix 1. Based on the entry criteria and published observational reports, we estimate that 44% of patients will develop a clinically indicated reason for pacing. A further 7.4% will have syncope without an indication for pacing based on the prevalence of vasovagal syncope. Therefore, 7.4% of subjects in the pacemaker arm are anticipated to have syncope per year. We anticipate that the complication rate for pacemakers will be 4.6% for acute complications and 1.6% per year for chronic complications and the ILR acute complication rate will be 1.4%.27–30 With these assumptions, the study is powered using an estimated 2-year event rate of 0.71 in the ILR arm and 0.30 in the pacemaker arm, adjusting for patients who cross over from the ILR to the pacemaker after experiencing a bradycardia-related MASRE outcome. Sample size calculations are based on the primary intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Patients will remain in the group to which they are randomized for this analysis. Patients who are otherwise lost to follow-up or who withdraw from the study for reasons unrelated to either symptoms or treatment will be included in the analysis. The primary ITT analysis is based on a group sequential design with two planned analyses at 3.5 and 5 years after enrolment has started.

A total sample size of 116 patients, randomized equally between the two groups will achieve 90% power to detect a difference when the event rates are 0.71 in the ILR and 0.30 in the pacemaker arms at an overall significance level, α = 0.05 using a two-sided test. These results assume that two sequential tests (one interim and one final) are made using the O'Brien–Fleming alpha spending function to determine the test boundaries.31 We anticipate no more than 4% loss of data (due to loss to follow-up for unknown reasons and refusal) and therefore plan to increase the sample size to 120 patients.

Conclusions

This multicentre, randomized, open-label, parallel group trial, if positive, will provide high-level and generalizable evidence for the use of either permanent pacing or ILRs as a first-line intervention for patients with syncope, preserved systolic function, and bifascicular block. Given that the inclusion criteria are based on clinical presentations, the results should provide for an accessible treatment strategy that can be readily adopted into practice, predicated on their history and ECG findings alone.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

A.D.K. is a Career Investigator of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. The study is supported by an Operating Grant of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ottawa, Canada (MOP-111094) to R.S.S.

Appendix 1. Rationale and probability of each major adverse study-related events (MASRE) outcome.

| MASRE outcome . | Rationale . | Probability . |

|---|---|---|

| Syncope | Major target symptom | 0.24 |

| Syncope and sinus arrest | Class I pacemaker indication | 0.08 |

| Syncope and asystole unspecified | Class I pacemaker indication | 0.02 |

| Presyncope and complete heart block | Class I pacemaker indication | 0.04 |

| Stable complete heart block | Likely to trigger pacemaker insertion | 0.06 |

| Complete heart block, rate <40 b.p.m. or asystole >3 s | Class I pacemaker indication | |

| Total bradycardia-related outcomes | 0.44 | |

| Vasovagal syncope | Major target symptom | 0.074 |

| ILR complications, first 30 days | Related morbidities | 0.014 |

| Pacemaker complications, first 30 days | Related morbidities | 0.046 |

| ILR complications, yearly | Related morbidities | 0.016 |

| Cardiovascular death | 0.00 |

| MASRE outcome . | Rationale . | Probability . |

|---|---|---|

| Syncope | Major target symptom | 0.24 |

| Syncope and sinus arrest | Class I pacemaker indication | 0.08 |

| Syncope and asystole unspecified | Class I pacemaker indication | 0.02 |

| Presyncope and complete heart block | Class I pacemaker indication | 0.04 |

| Stable complete heart block | Likely to trigger pacemaker insertion | 0.06 |

| Complete heart block, rate <40 b.p.m. or asystole >3 s | Class I pacemaker indication | |

| Total bradycardia-related outcomes | 0.44 | |

| Vasovagal syncope | Major target symptom | 0.074 |

| ILR complications, first 30 days | Related morbidities | 0.014 |

| Pacemaker complications, first 30 days | Related morbidities | 0.046 |

| ILR complications, yearly | Related morbidities | 0.016 |

| Cardiovascular death | 0.00 |