-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas Münzel, Andreas Daiber, Omar Hahad, Are e-cigarettes dangerous or do they boost our health: no END(S) of the discussion in sight, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 30, Issue 5, April 2023, Pages 422–424, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwac266

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘Acute effects of electronic cigarettes on vascular endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’, by X.-c. Meng et al. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwac248.

The global burden of tobacco use is devastating and is still ranked number 2 as a risk factor of death in the last 25 years just after the most significant risk factor arterial hypertension.1 Tobacco smoking reduces the life expectancy worldwide by 2.2 years.2 The WHO states that tobacco kills 50% of its users (more than 8 million people/year) and that 1.2 million deaths are attributable to exposure to second-hand smoke.3

When burned, cigarettes create more than 7000 chemicals. At least 69 of these chemicals are known to cause cancer, and many are toxic.4 Many of these chemicals also are found in consumer products, but these products will have warning labels—such as rat poison packaging.5

E-cigarettes came into the market in 2003 and were patented internationally in 2007. Soon they gained a striking popularity among cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Importantly, e-cigarettes are promoted as safe alternatives for traditional tobacco smoking and are often suggested as a method to reduce or quit smoking. There are many different types of e-cigarettes in use, also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) or electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS).3

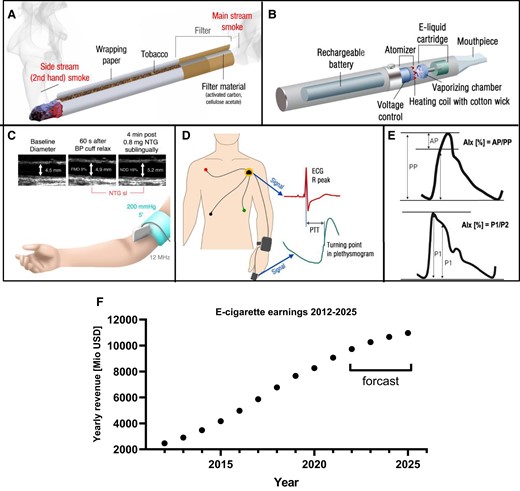

These systems heat a liquid to create aerosols that are inhaled by the user (see details of function in Figure 1). These e-liquids contain no tobacco and contain nicotine (that is highly addictive) or no nicotine as well as chemicals such glycerine and propylene glycol which may cause pulmonary and cardiovascular health side effects.6 This may explain why the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),7 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),8 and the World Health Organization (WHO)3 and also recently the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC)9 have issued concerns to use these e-cigarettes. With respect to cardiovascular side effects, several but not all studies have demonstrated that e-vaping may cause endothelial dysfunction,4 which can be considered as biomarker for cardiovascular disease.10

(A and B) Schematic construction of tobacco cigarette and e-cigarette. With permission from Münzel et al.,4 copyright © 2020, Oxford University Press. Overview on methods to assess vascular and endothelial function: (C) flow-mediated dilation, (D) pulse transit time, and (E) augmentation index (AIx) from aortic pressure pulse wave (upper) and peripheral arterial pressure pulse wave (lower). NTG, nitroglycerin; NDD, nitroglycerin-dependent dilation; AP, augmentation pressure; PP, pulse pressure; P1, the amplitude of the early systolic peak; P2, the amplitude of the late systolic peak. With permission from Daiber et al.,23 © 2016 The British Pharmacological Society (C) and Shimizu and Kario,24 copyright © 2008, SAGE Publications (E). (F) Yearly revenue from e-cigarette sales. Approximated from https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1178429/europe-revenue-in-the-e-cigarette-market (accessed 7 November 2022).

The results of the meta-analysis by Meng et al.11 indicate that e-cigarettes may have negative effects on vascular endothelial function. Eight studies involving 372 participants were eligible for this review. Pairwise and network analysis were conducted for three different methodologies to assess vascular NO formation such as flow-mediated dilation (FMD), arterial pulse wave velocity (PWV), and the heart rate-corrected augmentation index (AIx75) (see the explanation of the methodologies in Figure 1). Compared with vaping without nicotine, e-cigarettes with nicotine-containing e-liquid increased aPWV and AIx75, compatible with a reduction of vascular NO production, interestingly without affecting FMD. Also compared with traditional tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarettes failed to impair FMD. However, the present meta-analysis did not mention several studies that reported detrimental effects of acute e-cigarette vaping on endothelial function (measured by FMD), e.g.6,12–14 or an important study that reported beneficial effects on FMD when switching from tobacco cigarettes to vaping.15 The studies that were not mentioned did not match the inclusion criteria of the present meta-analysis since they did not have the predefined control groups (vaping without nicotine or tobacco smoking) for comparison with the vaping with nicotine group, but rather compared FMD prior and post e-cigarette vaping in the same individual. Nevertheless, they all provide important data on the impairment of endothelial function (measured by FMD) by acute e-cigarette vaping with nicotine. Also, methodological variability of FMD determination in the included studies may have interfered with the results as FMD is based on a less standardized and reliable approach when compared with, for example, endothelial function measurement by digital peripheral arterial tonometry.16,17 Interestingly, in network meta-analysis conducted by the authors, e-cigarette vaping, tobacco, and vaping without nicotine were ranked with respect to their effects on endothelial function, indicating e-cigarettes to have the strongest effect on FMD [as derived from the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) with SUCRA values ranging from 0 to 100%]. These analyses also revealed that e-cigarettes were not beneficial in terms of endothelial function compared with tobacco. Overall, the plausibility of e-cigarettes inducing cardiovascular damage is also reflected by a range of observational/epidemiological studies suggesting an increased cardiovascular disease risk in response to e-cigarette vaping (for an overview, see Munzel et al.4)

The authors concluded that there is evidence from their pooled analysis that acute inhalation of e-cigarettes has a negative effect on endothelial function. They also concluded that e-cigarettes cannot be used as an alternative to public health strategies for tobacco control and should also not be considered cardiovascular safety products.

Where to go from here? Is e-cigarette vaping as dangerous as tobacco smoking? Certainly not. Just based on the number of toxic compounds formed during the burning process, one has to conclude that vaping is clearly less dangerous than tobacco smoking. Is switching from tobacco smoking to e-cigarettes less harmful to our vessels? Definitively yes. For example, within 1 month of switching from tobacco smoking to e-cigarette vaping, there was a significant improvement in endothelial function and vascular stiffness which is because of the less toxicity not surprising.15

Do electronic cigarettes harm healthy vessels? The results of the present meta-analysis and a systematic review of 38 experimental studies (animals, humans, and cultured cells)18 revealed that e-cigarette vaping may have adverse effects on vascular function, all of which may be secondary to activation of superoxide-producing enzymes, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction6 and through mechanisms that increase the risk of thrombosis and atherosclerosis.18

The FDA, CDC, and WHO, all expressed reservations about the value of e-cigarettes and grave concerns about their risks. The American Heart Association (AHA) has even initiated a campaign to ban all e-cigarette sales. The AHA also claims that there is enough evidence associating e-cigarettes with teenager’s addiction to nicotine and with the seduction of non-smokers to smoking, is asking for stricter e-cigarette regulation,19 and welcomes the FDA decision to ban JUUL from the e-cigarette market: ‘The FDA’s decision sends the strongest possible message that Juul put the health of millions of our nation’s young people at risk with flavored e-cigarettes, high nicotine concentrations and years-long marketing campaigns aimed at kids’.20 Just recently, a position paper of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) was published.9 The authors concluded that there is increasing use of e-cigarettes by adolescents and young individuals, which is of major concern.9 They also noticed that long-term direct cardiovascular effects are unknown and that e-cigarettes should not be considered as a cardiovascular safe product.9

Importantly, the position in Europe concerning e-cigarettes is not consistent at all. In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) and the British Heart Foundation (BHF) strongly support the use of e-cigarettes in order to quit tobacco smoking21 and that their use could boost UK health. They even recommend that any smoker with a heart condition should try e-cigarettes in case he has tried to quit in the past and failed.

In summary, the strikingly increased use of e-cigarettes is concerning and a recently published statistics predicts that in Europe, an e-cigarette market in 2025 with around 10 Billion dollars is getting generated (see sales for Europe in Figure 1).22 Thus, broader tobacco control efforts by raising tobacco taxes, adopting smoke-free laws, conducting mass media campaigns, and restricting tobacco and e-cigarette marketing should be implemented for better health protection of the general population. We urgently need more long-term mechanistic studies to better understand the mechanisms of how e-cigarettes may affect the cardiovascular system. Despite a somewhat less toxic profile of e-cigarettes, smoking cessation remains the most powerful approach to prevent smoking-induced cardiovascular and pulmonary disease. Thus, there is no END(S) of the discussion in sight.

Funding

A.D. and T.M. were supported by vascular biology research grants from the Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation for the collaborative research group ‘Novel and neglected cardiovascular risk factors: molecular mechanisms and therapeutics’ and through continuous research support from Foundation Heart of Mainz. T.M. is PI and A.D. and O.H. are Scientists of the DZHK (German Center for Cardiovascular Research), Partner Site Rhine-Main, Mainz, Germany.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology or of the European Society of Cardiology.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Comments