-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Leonardo De Luca, Pier Luigi Temporelli, Donata Lucci, Lucio Gonzini, Carmine Riccio, Furio Colivicchi, Giovanna Geraci, Dario Formigli, Patrizia Maras, Colomba Falcone, Andrea Di Lenarda, Michele Massimo Gulizia, on behalf of the START Investigators, Current management and treatment of patients with stable coronary artery diseases presenting to cardiologists in different clinical contexts: A prospective, observational, nationwide study, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 25, Issue 1, 1 January 2018, Pages 43–53, https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317740663

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Stable coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide. Few studies document the complete sequence of investigation of the overall stable CAD population during outpatient visits or hospitalisation.

To obtain accurate and up-to-date information on current management of patients with stable CAD.

START (STable coronary Artery diseases RegisTry) was a prospective, observational, nationwide study aimed at evaluating the presentation, management, treatment and quality of life of stable CAD patients presenting to cardiologists during outpatient visits or discharged from cardiology wards.

Over a 3-month period, 5070 consecutive patients were enrolled in 183 participating centres: 72% managed by a cardiologist during outpatient or day hospital visits and 28% discharged from cardiology wards. The vast majority of patients (87%) received a coronary angiography (86% of patients managed during outpatient visits and 90% during hospitalisation; p < 0.0001). Outpatients more frequently received optimal medical therapy (OMT; i.e. aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers and statins) compared to hospitalised patients (70.2% vs 67.1%; p = 0.03). A personalised diet was prescribed in 58% (60.5% in outpatients and 52.9% in those admitted to hospitals; p < 0.0001), physical activity programmes were suggested in 65% (69.4% and 54.3%; p < 0.0001) and smoking cessation was recommended in 71% of currently smoking patients (73.2% and 65.2%; p = 0.02).

In this large, contemporary registry, patients with stable CAD discharged from cardiology wards more commonly underwent diagnostic imaging procedures and less frequently received OMT or lifestyle modification programmes compared to patients manged by cardiologists during outpatient visits.

Introduction

Stable coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common clinical manifestation of ischaemic heart disease and a leading cause of mortality worldwide. This condition encompasses several groups of patients, including those having stable angina pectoris or other symptoms felt to be related to CAD and those with known obstructive or non-obstructive CAD who have become asymptomatic due to pharmacological treatments and/or myocardial revascularisation.1,2

Large registries exist of patients who have CAD detected at coronary angiography3 and patients with stable angina,4 but few studies document the complete sequence of investigation of the overall stable CAD population during outpatient visits or hospitalisation.5 To obtain accurate and up-to-date information concerning the presentation and current management of patients with stable CAD managed by cardiologists in different settings, the Italian National Association of Hospital Cardiologist (ANMCO) designed the START (STable coronary Artery diseases RegisTry) study.

Methods

START was a prospective, observational, nationwide study aimed at evaluating the presentation, management, treatment and quality of life of stable CAD patients in a contemporary population as seen by cardiologists in clinical practice in Italy during a 3-month period. Patients with stable CAD presenting to a cardiologist during an outpatient visit or those discharged from cardiology wards were eligible if they had at least one of the following clinical conditions: (1) typical or atypical stable angina and/or non-anginal symptoms1,2; (2) documented ischaemia at stress test with or without symptoms; (3) previous revascularisation, such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting; (4) prior episode (occurred at least 30 days from enrolment) of acute coronary syndrome (ACS); and (5) elective admission for coronary revascularisation (including staged procedures). We excluded patients aged <18 years and those with Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class IV angina or with atypical chest pain that in all probability was not related to CAD.1,2 Enrolment was made at the end of outpatient or day hospital visits or at hospital discharge.

Data were analysed for two pre-specified groups of patients: (1) those presenting to outpatient visits or day hospital care (≤24 hours); and (2) those discharged from cardiology wards.

The ANMCO invited all Italian cardiology wards to participate, including university teaching hospitals, general and regional hospitals and private clinics receiving stable CAD patients. No specific protocols or recommendations for evaluation, management and/or treatment have been put forth during this observational study. However, current guidelines for the management of patients with stable CAD have been discussed during the investigator meetings.

All patients were informed of the nature and aims of the study and asked to sign an informed consent form for the anonymous management of their individual data. Local Institutional Review Boards (IRB) approved the study protocol according to the current Italian rules.

Data collection and data quality

Data on baseline characteristics, including demographics, risk factors and medical history, were collected. Information on the use of diagnostic cardiac procedures, type and timing of revascularisation therapy (if performed) and use of pharmacological or non-pharmacological therapies were recorded on an electronic case report form (CRF).

Optimal medical therapy (OMT) was defined as patients being prescribed aspirin or thienopiridine, β-blockers and a statin at any dosage. To be categorised as receiving OMT, individual patients must have been either prescribed or had reported contraindications to all medications in each category. The composite OMT percentages were calculated using the number of patients receiving OMT (as defined above) as the numerator and the total number of patients in the entire cohort as the denominator. Data on the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) were recorded and could be used to calculate their use among those patients in whom they were clinically indicated. Therefore, given that the guidelines for stable CAD recommend an ACE-I or ARB for some subgroups of patients,1,2 we also examined OMT, defined as patients being prescribed aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers, statins and ACE-Is or ARBs, if indicated by an ejection fraction of less than 40%, hypertension, diabetes or chronic renal dysfunction (eligible patients).

In addition, all patients in the study were asked to complete the self-administered EuroQoL-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L) quality of life questionnaire.6 The EQ-5D-5L is a simple, generic health-related quality of life instrument comprising a visual analogue scale (VAS) of self-rated general health and five domains (mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Scores on the VAS range from 0 (worst state) to 100 (best state). Scores in the five domains can be expressed as the percentage of patients who indicate five levels of severity on each domain.6

At each site, the principal investigator was responsible for screening consecutive patients with a diagnosis of stable CAD. Data were collected using a web-based, electronic CRF with the central database located at ANMCO Research Center. By using a validation plan integrated into the data entry software, data were checked for missing or contradictory entries and values outside of the normal range.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and compared using the chi-squared test. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs), except for timing from diagnostic procedures to enrolment, triglycerides and health status assessment, which are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The study cohort was stratified according to the modality of enrolment (i.e. outpatient visits and day hospital care vs hospital admissions). Continuous variables were compared by the t-test if normally distributed or by the Mann–Whitney U test if not.

Clinically relevant variables were included in a multivariable model (logistic regression) to identify the independent predictors of not receiving OMT (aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers and statins) among the two groups (patients managed during outpatient visits or discharged from cardiology wards). The variables included in the latter logistic model were age, systolic blood pressure and heart rate (as continuous variables), gender, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral artery disease, ejection fraction ≤40%, history of heart failure, prior revascularisation, prior myocardial infarction and prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack. When more than two categories were present, dummy variables were introduced to define a reference group.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were two-tailed. Analyses were performed with SAS system software, version 9.2.

Results

Each site started patient enrolment after local IRB approval. Therefore, data were collected in different periods of consecutive 3 months in each site between 19 March 2016 and 28 February 2017. Over these periods, 5070 consecutive patients with stable CAD were enrolled: 3638 (71.8%) presenting to a cardiologist during outpatient or day hospital visits and 1432 (28.2%) discharged from cardiology wards. The study has been carried out in 183 cardiology centres located in 177 hospitals: a mix of hospitals with non-invasive diagnostic facilities only (49%) and hospitals with catheterisation laboratories and/or cardiac surgery facilities onsite (51%), well representing the Italian cardiology reality in terms of geographical distribution and level of hospital technology (Supplementary Table 1).7

The reasons for enrolment were as follows: prior ACS in 67.5%, previous revascularisation in 78.2%, elective admission for revascularisation in 8.5% and stable angina and positive stress test in 26.8%; more than one reason was reported in 69.2% of cases. Among patients with stable angina, the majority (93.0%) had mild to moderate angina, CCS class I or II.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of enrolled patients was 68 ± 11 years, 80% were male, 31% were diabetics and 75% had hypercholesterolaemia. Patients hospitalised for stable CAD were older and had a higher incidence of risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal dysfunction, peripheral artery disease and history of heart failure compared to patients presenting to cardiologists during outpatient visits (Table 1).

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 67.6 ± 10.5 | 67.2 ± 10.7 | 68.6 ± 9.9 | <0.0001 |

| Age >75 years, n (%) | 1283 (25.3) | 902 (24.8) | 381 (26.6) | 0.18 |

| Females, n (%) | 1008 (19.9) | 700 (19.2) | 308 (21.5) | 0.07 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 4.0 | 0.06 |

| Risk factors and comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Active smokers | 887 (17.5) | 637 (17.5) | 250 (17.5) | 0.97 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 3790 (74.8) | 2734 (75.2) | 1056 (73.7) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1558 (30.7) | 1042 (28.6) | 516 (36.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 4024 (79.4) | 2840 (78.1) | 1184 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal dysfunction | 602 (11.9) | 376 (10.3) | 226 (15.8) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 451 (8.9) | 272 (7.5) | 179 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 603 (11.9) | 384 (10.6) | 219 (15.3) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep apnoea | 163 (3.2) | 115 (3.2) | 48 (3.3) | 0.73 |

| Malignancy | 331 (6.5) | 221 (6.1) | 110 (7.7) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 531 (10.5) | 397 (10.9) | 134 (9.4) | 0.10 |

| Cardiovascular history, n (%) | ||||

| Previous stroke/TIA | 276 (5.4) | 186 (5.1) | 90 (6.3) | 0.10 |

| History of major bleeding events | 95 (1.9) | 63 (1.7) | 32 (2.2) | 0.23 |

| History of heart failure | 680 (13.4) | 420 (11.5) | 260 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class III–IV | 153 (3.0) | 61 (1.7) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Prior STEMI | 1828 (36.1) | 1452 (39.9) | 376 (26.3) | <0.0001 |

| Previous revascularisation | 3966 (78.2) | 3048 (83.8) | 918 (64.1) | <0.0001 |

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 67.6 ± 10.5 | 67.2 ± 10.7 | 68.6 ± 9.9 | <0.0001 |

| Age >75 years, n (%) | 1283 (25.3) | 902 (24.8) | 381 (26.6) | 0.18 |

| Females, n (%) | 1008 (19.9) | 700 (19.2) | 308 (21.5) | 0.07 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 4.0 | 0.06 |

| Risk factors and comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Active smokers | 887 (17.5) | 637 (17.5) | 250 (17.5) | 0.97 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 3790 (74.8) | 2734 (75.2) | 1056 (73.7) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1558 (30.7) | 1042 (28.6) | 516 (36.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 4024 (79.4) | 2840 (78.1) | 1184 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal dysfunction | 602 (11.9) | 376 (10.3) | 226 (15.8) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 451 (8.9) | 272 (7.5) | 179 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 603 (11.9) | 384 (10.6) | 219 (15.3) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep apnoea | 163 (3.2) | 115 (3.2) | 48 (3.3) | 0.73 |

| Malignancy | 331 (6.5) | 221 (6.1) | 110 (7.7) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 531 (10.5) | 397 (10.9) | 134 (9.4) | 0.10 |

| Cardiovascular history, n (%) | ||||

| Previous stroke/TIA | 276 (5.4) | 186 (5.1) | 90 (6.3) | 0.10 |

| History of major bleeding events | 95 (1.9) | 63 (1.7) | 32 (2.2) | 0.23 |

| History of heart failure | 680 (13.4) | 420 (11.5) | 260 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class III–IV | 153 (3.0) | 61 (1.7) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Prior STEMI | 1828 (36.1) | 1452 (39.9) | 376 (26.3) | <0.0001 |

| Previous revascularisation | 3966 (78.2) | 3048 (83.8) | 918 (64.1) | <0.0001 |

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI: myocardial infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 67.6 ± 10.5 | 67.2 ± 10.7 | 68.6 ± 9.9 | <0.0001 |

| Age >75 years, n (%) | 1283 (25.3) | 902 (24.8) | 381 (26.6) | 0.18 |

| Females, n (%) | 1008 (19.9) | 700 (19.2) | 308 (21.5) | 0.07 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 4.0 | 0.06 |

| Risk factors and comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Active smokers | 887 (17.5) | 637 (17.5) | 250 (17.5) | 0.97 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 3790 (74.8) | 2734 (75.2) | 1056 (73.7) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1558 (30.7) | 1042 (28.6) | 516 (36.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 4024 (79.4) | 2840 (78.1) | 1184 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal dysfunction | 602 (11.9) | 376 (10.3) | 226 (15.8) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 451 (8.9) | 272 (7.5) | 179 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 603 (11.9) | 384 (10.6) | 219 (15.3) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep apnoea | 163 (3.2) | 115 (3.2) | 48 (3.3) | 0.73 |

| Malignancy | 331 (6.5) | 221 (6.1) | 110 (7.7) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 531 (10.5) | 397 (10.9) | 134 (9.4) | 0.10 |

| Cardiovascular history, n (%) | ||||

| Previous stroke/TIA | 276 (5.4) | 186 (5.1) | 90 (6.3) | 0.10 |

| History of major bleeding events | 95 (1.9) | 63 (1.7) | 32 (2.2) | 0.23 |

| History of heart failure | 680 (13.4) | 420 (11.5) | 260 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class III–IV | 153 (3.0) | 61 (1.7) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Prior STEMI | 1828 (36.1) | 1452 (39.9) | 376 (26.3) | <0.0001 |

| Previous revascularisation | 3966 (78.2) | 3048 (83.8) | 918 (64.1) | <0.0001 |

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 67.6 ± 10.5 | 67.2 ± 10.7 | 68.6 ± 9.9 | <0.0001 |

| Age >75 years, n (%) | 1283 (25.3) | 902 (24.8) | 381 (26.6) | 0.18 |

| Females, n (%) | 1008 (19.9) | 700 (19.2) | 308 (21.5) | 0.07 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 4.0 | 0.06 |

| Risk factors and comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Active smokers | 887 (17.5) | 637 (17.5) | 250 (17.5) | 0.97 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 3790 (74.8) | 2734 (75.2) | 1056 (73.7) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1558 (30.7) | 1042 (28.6) | 516 (36.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 4024 (79.4) | 2840 (78.1) | 1184 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal dysfunction | 602 (11.9) | 376 (10.3) | 226 (15.8) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 451 (8.9) | 272 (7.5) | 179 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 603 (11.9) | 384 (10.6) | 219 (15.3) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep apnoea | 163 (3.2) | 115 (3.2) | 48 (3.3) | 0.73 |

| Malignancy | 331 (6.5) | 221 (6.1) | 110 (7.7) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 531 (10.5) | 397 (10.9) | 134 (9.4) | 0.10 |

| Cardiovascular history, n (%) | ||||

| Previous stroke/TIA | 276 (5.4) | 186 (5.1) | 90 (6.3) | 0.10 |

| History of major bleeding events | 95 (1.9) | 63 (1.7) | 32 (2.2) | 0.23 |

| History of heart failure | 680 (13.4) | 420 (11.5) | 260 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class III–IV | 153 (3.0) | 61 (1.7) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Prior STEMI | 1828 (36.1) | 1452 (39.9) | 376 (26.3) | <0.0001 |

| Previous revascularisation | 3966 (78.2) | 3048 (83.8) | 918 (64.1) | <0.0001 |

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI: myocardial infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

Table 2 shows the haemodynamic parameters and laboratory data at the time of enrolment. Among patients with data available, the mean ejection fraction was 54%, the heart rate was 66 bpm, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was 87 mg/dL and the median level of triglycerides was 112 mg/dL. Once again, patients admitted to hospital presented with high-risk features such as a lower ejection fraction and higher levels of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides compared to the other group of patients (Table 2).

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection fraction, % (mean ± SD) | 53.9 ± 9.9 | 54.8 ± 9.1 | 51.7 ± 11.5 | <0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 130.1 ± 16.5 | 130.1 ± 16.4 | 130.0 ± 16.7 | 0.86 |

| DBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 75.9 ± 9.1 | 76.5 ± 8.8 | 74.4 ± 9.7 | <0.0001 |

| HR, bpm (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 10.8 | 65.6 ± 10.3 | 66.6 ± 12.1 | 0.005 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 211 (4.2) | 119 (3.3) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hb, g/dL (mean ± SD) | 13.6 ± 1.7 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.10 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 154.7 ± 39.0 | 153.6 ± 38.1 | 157.1 ± 40.9 | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 87.4 ± 33.8 | 86.3 ± 33.4 | 89.5 ± 34.7 | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 112 (84–152) | 110 (83–150) | 115 (85–159) | 0.02 |

| Glycaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 113.7 ± 36.1 | 112.5 ± 33.1 | 116.1 ± 41.2 | 0.007 |

| Uricaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection fraction, % (mean ± SD) | 53.9 ± 9.9 | 54.8 ± 9.1 | 51.7 ± 11.5 | <0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 130.1 ± 16.5 | 130.1 ± 16.4 | 130.0 ± 16.7 | 0.86 |

| DBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 75.9 ± 9.1 | 76.5 ± 8.8 | 74.4 ± 9.7 | <0.0001 |

| HR, bpm (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 10.8 | 65.6 ± 10.3 | 66.6 ± 12.1 | 0.005 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 211 (4.2) | 119 (3.3) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hb, g/dL (mean ± SD) | 13.6 ± 1.7 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.10 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 154.7 ± 39.0 | 153.6 ± 38.1 | 157.1 ± 40.9 | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 87.4 ± 33.8 | 86.3 ± 33.4 | 89.5 ± 34.7 | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 112 (84–152) | 110 (83–150) | 115 (85–159) | 0.02 |

| Glycaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 113.7 ± 36.1 | 112.5 ± 33.1 | 116.1 ± 41.2 | 0.007 |

| Uricaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; Hb: haemoglobin; HR: heart rate; IQR: interquartile range; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection fraction, % (mean ± SD) | 53.9 ± 9.9 | 54.8 ± 9.1 | 51.7 ± 11.5 | <0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 130.1 ± 16.5 | 130.1 ± 16.4 | 130.0 ± 16.7 | 0.86 |

| DBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 75.9 ± 9.1 | 76.5 ± 8.8 | 74.4 ± 9.7 | <0.0001 |

| HR, bpm (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 10.8 | 65.6 ± 10.3 | 66.6 ± 12.1 | 0.005 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 211 (4.2) | 119 (3.3) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hb, g/dL (mean ± SD) | 13.6 ± 1.7 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.10 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 154.7 ± 39.0 | 153.6 ± 38.1 | 157.1 ± 40.9 | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 87.4 ± 33.8 | 86.3 ± 33.4 | 89.5 ± 34.7 | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 112 (84–152) | 110 (83–150) | 115 (85–159) | 0.02 |

| Glycaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 113.7 ± 36.1 | 112.5 ± 33.1 | 116.1 ± 41.2 | 0.007 |

| Uricaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection fraction, % (mean ± SD) | 53.9 ± 9.9 | 54.8 ± 9.1 | 51.7 ± 11.5 | <0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 130.1 ± 16.5 | 130.1 ± 16.4 | 130.0 ± 16.7 | 0.86 |

| DBP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 75.9 ± 9.1 | 76.5 ± 8.8 | 74.4 ± 9.7 | <0.0001 |

| HR, bpm (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 10.8 | 65.6 ± 10.3 | 66.6 ± 12.1 | 0.005 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 211 (4.2) | 119 (3.3) | 92 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hb, g/dL (mean ± SD) | 13.6 ± 1.7 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.10 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 154.7 ± 39.0 | 153.6 ± 38.1 | 157.1 ± 40.9 | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 87.4 ± 33.8 | 86.3 ± 33.4 | 89.5 ± 34.7 | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 112 (84–152) | 110 (83–150) | 115 (85–159) | 0.02 |

| Glycaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 113.7 ± 36.1 | 112.5 ± 33.1 | 116.1 ± 41.2 | 0.007 |

| Uricaemia, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; Hb: haemoglobin; HR: heart rate; IQR: interquartile range; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Diagnostic procedures

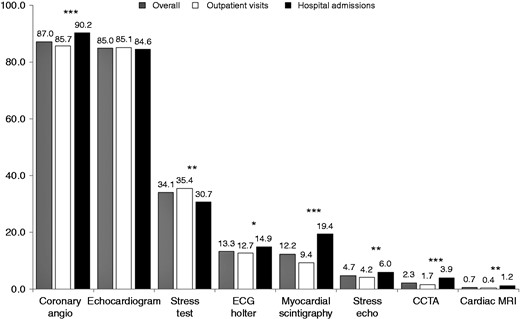

Diagnostic cardiac procedures performed in the overall population and in the two groups (i.e. outpatients or hospitalised patients) are shown in Figure 1. The vast majority of patients received a coronary angiography (87%) and a transthoracic echocardiogram (85%), followed by a stress test (34%) and other diagnostic procedures.

Diagnostic procedures performed in the overall population and in the two groups of patients.

CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; ECG: electrocardiogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

***p < 0.0001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

The time intervals between imaging procedures and enrolment are depicted in Table 3. In general, patients discharged from hospitals underwent more frequent and earlier coronary angiographies and other diagnostic imaging procedures compared to stable CAD subjects presenting to outpatient visits (Figure 1 and Table 3).

Timing (days) from diagnostic procedures to enrolment, median (interquartile range).

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary angiography | 159 (21–897) | 322 (88–1316) | 2 (1–5) | <0.0001 |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | 32 (1–144) | 55 (2–206) | 4 (1–19) | <0.0001 |

| Stress test | 42 (2–220) | 61 (1–289) | 27 (9–72) | <0.001 |

| ECG Holter | 46 (9–274) | 91 (30–362) | 6 (1–27) | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial scintigraphy | 134 (41–607) | 349 (97–1071) | 50 (28–148) | <0.0001 |

| Stress echocardiography | 93 (8–469) | 164 (13–624) | 55 (7–312) | 0.06 |

| CCTA | 52 (16–328) | 91 (17–545) | 37 (15–136) | 0.05 |

| Cardiac MRI | 178 (35–802) | 400 (62–983) | 103 (7–742) | 0.21 |

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary angiography | 159 (21–897) | 322 (88–1316) | 2 (1–5) | <0.0001 |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | 32 (1–144) | 55 (2–206) | 4 (1–19) | <0.0001 |

| Stress test | 42 (2–220) | 61 (1–289) | 27 (9–72) | <0.001 |

| ECG Holter | 46 (9–274) | 91 (30–362) | 6 (1–27) | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial scintigraphy | 134 (41–607) | 349 (97–1071) | 50 (28–148) | <0.0001 |

| Stress echocardiography | 93 (8–469) | 164 (13–624) | 55 (7–312) | 0.06 |

| CCTA | 52 (16–328) | 91 (17–545) | 37 (15–136) | 0.05 |

| Cardiac MRI | 178 (35–802) | 400 (62–983) | 103 (7–742) | 0.21 |

CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; ECG: electrocardiogram; IQR: interquartile range; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Timing (days) from diagnostic procedures to enrolment, median (interquartile range).

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary angiography | 159 (21–897) | 322 (88–1316) | 2 (1–5) | <0.0001 |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | 32 (1–144) | 55 (2–206) | 4 (1–19) | <0.0001 |

| Stress test | 42 (2–220) | 61 (1–289) | 27 (9–72) | <0.001 |

| ECG Holter | 46 (9–274) | 91 (30–362) | 6 (1–27) | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial scintigraphy | 134 (41–607) | 349 (97–1071) | 50 (28–148) | <0.0001 |

| Stress echocardiography | 93 (8–469) | 164 (13–624) | 55 (7–312) | 0.06 |

| CCTA | 52 (16–328) | 91 (17–545) | 37 (15–136) | 0.05 |

| Cardiac MRI | 178 (35–802) | 400 (62–983) | 103 (7–742) | 0.21 |

| . | Overall (n = 5070) . | Outpatient visits (n = 3638) . | Hospital admissions (n = 1432) . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary angiography | 159 (21–897) | 322 (88–1316) | 2 (1–5) | <0.0001 |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | 32 (1–144) | 55 (2–206) | 4 (1–19) | <0.0001 |

| Stress test | 42 (2–220) | 61 (1–289) | 27 (9–72) | <0.001 |

| ECG Holter | 46 (9–274) | 91 (30–362) | 6 (1–27) | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial scintigraphy | 134 (41–607) | 349 (97–1071) | 50 (28–148) | <0.0001 |

| Stress echocardiography | 93 (8–469) | 164 (13–624) | 55 (7–312) | 0.06 |

| CCTA | 52 (16–328) | 91 (17–545) | 37 (15–136) | 0.05 |

| Cardiac MRI | 178 (35–802) | 400 (62–983) | 103 (7–742) | 0.21 |

CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; ECG: electrocardiogram; IQR: interquartile range; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Lifestyle and pharmacological management

A personalised diet was prescribed in 58% of the patients (60.5% in outpatients and 52.9% in those hospitalised; p < 0.0001), physical activity programmes were suggested in 65% (69.4% and 54.3%; p < 0.0001) and smoking cessation was recommended in 71% of currently smoking patients (73.2% and 65.2%; p = 0.02).

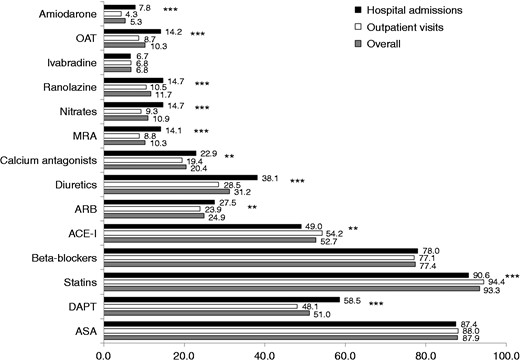

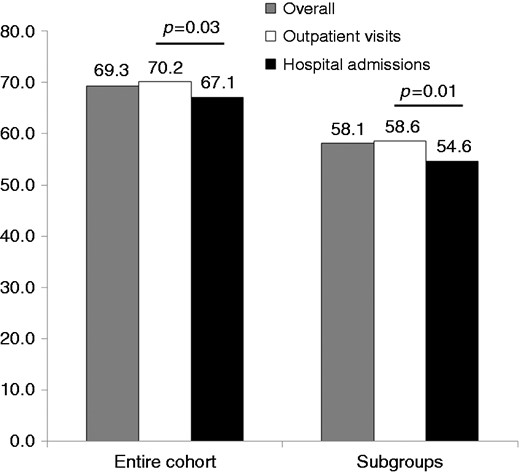

At the end of the visit or at discharge, the majority of patients were prescribed aspirin (88%), renin angiotensin system inhibitors (77%), statins (93%), β-blockers (77%) or ACE-Is/ARBs (77%), while drugs for angina relief were used in a minority of cases (Figure 2). In general, hospitalised stable CAD patients more frequently received single pharmacological therapies compared to outpatients. However, patients managed during outpatient visits received more frequently OMT (aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers and statins) in the entire cohort (70.2% vs 67.1%; p = 0.03) and OMT (aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers, statins and ACE-Is or ARBs) in eligible patients (58.6% vs 54.6%; p = 0.01) compared to hospitalised patients (Figure 3).

Pharmacological therapiesa prescribed at the end of the visit or at hospital discharge in the overall population and in the two groups of patients.

aDrugs not reported have been used in less than 1% of cases.

ACE-I: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; OAT: oral anticoagulation therapy.

***p < 0.0001; **p < 0.01.

Use of optimal medical therapy (OMT) (aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers and statins) in the overall population and in the two groups of patients and OMT (aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers, statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers) among eligible patients.

At multivariate analyses, age and the presence of COPD were the only independent predictors of no OMT prescription among both patients managed during outpatient visits (odds ratio [OR] 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.02; p < 0.0001 and OR 1.60; 95% CI 1.27–2.00; p < 0.0001, respectively) and those discharged from cardiology wards (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.01–1.04; p < 0.0001 and OR 1.50; 95% CI 1.09–2.06; p = 0.013, respectively).

Quality of life assessment

The EQ 5D-5L questionnaire was completed by 4853 (96%) patients. The median (IQR) VAS score of self-rated general health status was 75 (range 60–85) (80 [range 65–90] in outpatients and 70 [range 60–80] in hospitalised patients; p < 0.0001).

Over 60% of patients reported having ‘no problems’ in all EQ-5D-5L domains (61.4–85.6%), except for depression/anxiety, which was present, to different degrees, in at least 42% of patients enrolled. The single domains with the five levels of severity in each domain are represented in Figure 4 and did not differ between the two groups.

Single domains of EuroQoL-5D-5L questionnaire in the overall population and in the two groups of patients. (a) movement ability; (b) body care; (c) usual activities; (d) pain or worry; (e) anxiety or depression.

Discussion

In this nationwide, contemporary, prospective registry of 5070 consecutive, unselected, stable CAD patients enrolled over 3 months in 183 cardiology Italian centres, we observed that patients discharged from cardiology wards more commonly undergo diagnostic imaging procedures and less frequently receive OMT or lifestyle modification programmes compared to patients managed by cardiologists during outpatient visits.

The clinical profile of the patients enrolled in the START registry is closer to that of patients enrolled in contemporary registries with stable CAD, such as the Chronic Ischaemic Cardiovascular Disease Registry (CICD)-PILOT survey, a European observational, longitudinal registry in CAD and/or peripheral arterial disease (PAD) patients,5 and the ProspeCtive observational LongitudinAl RegIstry oF patients with stable coronary arterY disease (CLARIFY) registry, a large, international registry of patients with stable angina and/or documented ischaemia.8 As expected, patients enrolled in our registry during hospitalisation were older and more frequently had a history of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and peripheral artery diseases compared to patients enrolled during outpatient visits. These findings confirm the different clinical profiles and related management patterns of patients with suspected CAD managed during ambulatory visits and those with confirmed disease discharged from cardiology wards.

In case of suspected stable CAD, a stepwise approach for decision making is recommended by current international guidelines.1,2 This process begins with a clinical assessment followed by non-invasive testing to establish the diagnosis of CAD in patients with an intermediate probability of disease. Regarding follow-up visits of patients with confirmed CAD, recent guidelines recommend a multifaceted approach, including lifestyle modification, control of CAD risk factors, evidence-based pharmacological therapies and cardiac rehabilitation, when indicated,9,10 generally discouraging the use of non-invasive testing on a regular basis in asymptomatic patients with uncomplicated CAD.1,2 Our data show that diagnostic cardiac procedures are largely employed in clinical practice in patients with a diagnosis of stable CAD. Nevertheless, the high use of echocardiography and other non-invasive investigations together with a lower rate of stress testing observed in our population compared favourably with that reported from other European and North American real-world studies on stable CAD.5,11–14 Recently, two randomised clinical trials, namely SCOT-HEART (Scottish COmputed Tomography of the HEART)15 and PROMISE (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain),16 demonstrated that the addition of an advanced imaging test such as coronary computed tomography angiography to standard clinical care is able to markedly clarify the diagnosis of angina due to CAD, reducing the need for further stress testing and potentially providing better prognostic information than functional testing in patients whit stable angina. However, this imaging technique does not seem to be integrated in real-world diagnostic pathways of stable CAD, since it has been used in only 2% of cases in our series. On the other hand, coronary angiography was the most common diagnostic technique performed, especially among patients admitted to hospital who received this invasive procedure very early from enrolment (median time: 2 days before hospital discharge). It seems reasonable that in our series, patients enrolled during hospitalisation who more frequently present with risk factors or comorbidities compared to those managed during cardiology visits were mainly admitted for coronary angiography or for programmed PCI, potentially explaining the very high rate of coronary angiography observed in this patient group.

The large COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) trial17,18 and several meta-analyses19–21 concluded that there was no benefit of revascularisation compared to OMT in preventing myocardial infarction or death in patients with stable angina. Therefore, current guidelines support the aggressive use of OMT, while the use of invasive coronary angiography and revascularisation should be limited to patients with residual severe symptoms and large areas of myocardial ischaemia.1,2 Our study suggests that, although the overall use of pharmacological therapies is higher compared to other real-world experiences previously published,9,22,23 there remains an important opportunity to develop innovative strategies to increase recommended OMT in the comprehensive care of patients with stable CAD, especially among those discharged from hospitals. Indeed, in the COURAGE trial, 79% of patients received the combination of aspirin, β-blockers and statins after randomisation and 55% received the combination of aspirin, β-blockers, statins and ACE-Is or ARBs16,22 compared with our finding of 69% and 58%, respectively, being prescribed these therapies at the time of enrolment. Our data are comparable with other real-world experiences published a few years ago, soon after the publication of the COURAGE trial.5,22,23 Therefore, resistance to changing behaviour continues in clinical practice to this day. The sources of the resistance are multi-fold and include referral bias, financial gain, poor understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms and individual physician beliefs of what might benefit the patient and patient perceptions of the potential benefits of the procedure unsubstantiated by data.24–26

In the present survey, around 27% of enrolled patients with stable CAD presented with effort angina. Angina is an important predictor of cardiac events and to a large extent determines health-related quality of life in this patient group.27–29 Therefore, quality of life assessment should be regarded as an essential measure of the impact of this disease, in domains related not only to physical functioning, but also to psychological well-being and social functioning. In the Euro Heart Survey, which enrolled 3779 consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of stable angina by a cardiologist, around 60% of patients with angina were moderately/severely limited in their daily activities at the time of diagnosis.7

In addition, several studies demonstrated a strong correlation of angina frequency with depression.30 Even in our series, a history of depression was present in 10% of cases at baseline and, using the EQ 5D-5L questionnaire, depression/anxiety was present in almost 42% of patients enrolled.

Study limitations

Our study must be evaluated in the light of the known limitations of observational, cross-sectional studies. In addition, the data reported in the present analysis are limited to the time of the visit or hospitalisation. However, a clinical follow-up at 1 year from enrolment is ongoing and will assess clinical outcomes, adherence to prescribed therapies and quality of life. Finally, even though the participating centres were asked to include in the registry all consecutive patients with stable CAD, we were not able to verify the enrolment process due to the absence of administrative auditing. We believe that it is unlikely, however, that selective enrolment in a few sites may have substantially changed the study results.

Conclusions

This survey provides unique insights into the current management and treatment of patients with stable CAD presenting to a cardiologist in different clinical contexts. Patients managed by cardiologists during outpatient visits seem to more strictly follow current guideline recommendations compared to patients discharged from cardiology wards in terms of recourse to invasive diagnostic procedures and OMT. The present data should stimulate efforts to assess the appropriateness of coronary revascularisation by scientific societies and to improve compliance with current guidelines, especially among patients with stable CAD discharged from cardiology wards.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Barbara Bartolomei Mecatti for editorial assistance.

Author contribution

LDL and PLT drafted the manuscript; CR, FR, GG, DF, PM, CF, ADL and MMG revised it critically; LG and DL analysed the data. All gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: LDL and PLT report personal fees from Menarini, outside the submitted work; all other authors have reported that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organisations whose products or services may be discussed in this article. DL and LG are employees of the Heart Care Foundation, which conducted the study with an unrestricted grant of research from Menarini, Italy.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The sponsor of the study was the Heart Care Foundation, a non-profit independent organisation that also owns the database. Database management, quality control of the data and data analyses were under the responsibility of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation. The study was partially supported by an unrestricted grant by Menarini, Italy. No compensation was provided to participating sites, investigators, nor members of the Steering Committee. The Steering Committee of the study had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

Author notes

See Supplementary material for a complete list of centres and investigators.

- angina pectoris

- aspirin

- physical activity

- smoking

- coronary angiography

- coronary arteriosclerosis

- coronary artery

- statins

- cardiologists

- cardiology

- smoking cessation

- diet

- osteopathic manipulation

- outpatients

- registries

- diagnostic imaging

- mortality

- quality of life

- lifestyle changes

- thienopyridine

- medical management

Comments