-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Neil J Stone, RACING to judgement: weighing the value of pre-specified subgroup analyses, European Heart Journal, Volume 44, Issue 11, 14 March 2023, Pages 984–985, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac782

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘Moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe vs. high-intensity statin in patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the RACING trial’, by Y.-J. Lee et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac709.

Large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the backbone of clinical practice guidelines. They inform clinical decision-making for individual patients. Importantly, they allow the patient and clinician to utilize proven treatment regimens to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.

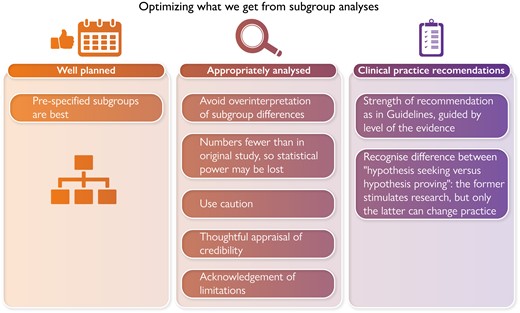

Subgroup analyses from large RCTs are informative and at times provide answers to questions not specifically addressed in the larger trial. However, caution is advised. The results of subgroup analyses can be misleading. This is especially true when the RCT results from the larger trial from which subgroup data are derived are negative. For example, the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial of lipid lowering in those with Type 2 diabetes did not show that fibrates added to moderate-intensity statin therapy reduced atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) outcomes.1 Subgroup analysis suggested that there might be benefit in men with elevated triglycerides and low HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), a subgroup that made sense based on prior post-hoc analyses of trials with fibrates. However, caution was appropriately urged before accepting this subgroup analysis2 Now in 2022, the PROMINENT TRIAL featuring permafibrate as the intervention confirms the wisdom of that caution. Fibrate therapy added to baseline statin therapy in those with Type 2 diabetes, mild to moderate hypertriglyceridaemia, low HDL-C, and low LDL-C showed no reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events.3 LDL-C and apolipoprotein B (apo B) were not significantly lowered, confirming the ‘LDL principle’ (no longer a hypothesis) that to reduce rates of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events lowering of LDL-C and, more precisely, apo B levels is required.4

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Lee et al. present the subgroup analysis study of the RACING trial that focuses on the 1398 participants (38%) with Type 2 diabetes.5 The RACING trial enrolled 3780 patients with ASCVD at 26 clinical centres in South Korea.6 It was an open-label non-inferiority trial that compared rosuvastatin 20 mg/day (high-intensity statin therapy) with ezetimibe 10 mg/day added to rosuvastatin 10 mg/day (combination therapy). The primary endpoint was the 3-year composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or non-fatal stroke. The strategy employing combination therapy proved non-inferior to the high-intensity statin strategy. However, LDL-C concentrations of <70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) were lower in the combination therapy group compared with the high-intensity statin group in the first 3 years and intolerance-related discontinuation rates were lower (4.8% vs. 8.2%). These results prompted the editorialists for the paper by Kim et al., Drs Abushamat and Ballantyne, to suggest a paradigm shift in initial lipid-focused treatment away from a high-intensity statin therapy to combination therapy with moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe.7 They noted that combination therapy to initiate treatment is already widely used and endorsed for blood pressure control.

The subgroup analysis confined to those with diabetes agreed with the findings of the larger trial of patients with ASCVD. However, as is the case with subgroup analyses, numbers are fewer and statistical power is lost, an important consideration when addressing outcome events. This underscores an important limitation of subgroup analyses that readers should understand.8 Thus, the data presented by Lee et al. are hypothesis generating, not proving. However, in accord with the main RACING trial were two additional and noteworthy findings. Combination therapy led to significantly less intolerance-related discontinuation or dose reduction of the study regimen (5.2% vs. 8.7% of patients in the combination vs. high-intensity statin regimens, respectively; P = 0.014). This may have contributed to even greater numbers achieving an LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L). The difference was notable: 81.0, 83.1, and 79.9% of patients assigned to combination therapy achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) vs. 64.1, 70.2, and 66.8% of patients assigned to the high-intensity statin (all P < 0.001). In clinical practice, tolerability along with affordability and accessibility are important for optimal adherence.

RACING was not the first RCT to use ezetimibe, an intestinal-acting drug that inhibits a crucial mediator of cholesterol absorption in the gut—the Niemann–Pick-C1 like 1 receptor. A recent and influential RCT, IMPROVE IT, compared ezetimibe with placebo in those high-risk patients with a history of acute coronary syndrome on a moderate-intensity statin with an LDL-C of ∼70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L).9 ‘Lower was better’, with ASCVD outcomes improved in the group assigned ezetimibe who achieved an LDL-C of ∼54 mg/dL (1.4 mmol/L). The results were especially striking in those over age 75 and in those with diabetes. Given the high absolute risk of patients with these characteristics, that insight reminds us how helpful additional LDL-C lowering is in these very high-risk patients. Further informative analyses of IMPROVE-IT by Navar and colleagues showed that discontinuation was high early in the trial, but then stabilized at 8% per year. Importantly, adding ezetimibe to moderate-intensity simvastatin did not increase discontinuation.10

Thus, the subgroup analysis by Lee and colleagues, while hypothesis generating due to its small size, nonetheless provides a valuable reminder for us that strategies that have the potential to improve adherence are important for all, but especially those at highest risk. However, it may be vital to consider more than just ‘racing’ to keeping LDL-C and apo B low in secondary prevention with proven therapy. We also need to stop and focus on achieving adherence, with regular follow-up testing to derive the full benefit of our guideline-directed antiatherosclerotic therapy. Innovative studies to guide clinicians and patients on improving adherence should be an important focus for continuing research to provide effective implementation of guideline-directed strategies.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

Conflict of interest: N.J.S. does not accept honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry. He discloses an honorarium for an educational talk on randomized trials from an educational company, Knowledge to Practice.