-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

S. Goya Wannamethee, Frailty and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: are we at a crossroad to include frailty in cardiovascular risk assessment in older adults?, European Heart Journal, Volume 43, Issue 8, 21 February 2022, Pages 827–829, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab818

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US Veterans’, by W. Shrauner et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850.

Interest in frailty and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has grown considerably in the past decade and has become a high priority theme in CVD management.1 , 2 Frailty, which is commonly defined as a biological syndrome that reflects a state of decreased physical reserve and increased vulnerability to stressors, is associated with many adverse clinical outcomes including disability and increased mortality.3 The prevalence and incidence of CVD morbidity has continued to increase in the last decade with population ageing and improved event survival. Frailty is commonly seen among people with CVD; a pooled analysis of 46 studies estimated that ∼1 in 5 adults with coronary heart disease are frail,4 and frailty in those with CVD has been shown to have a worse prognosis than in those who are not frail.2 , 5 The question of whether CVD leads to frailty or whether frailty may precede the development of CVD has been a topic of intense research. There is growing evidence that the relationship between frailty and CVD is bidirectional; CVD is associated with over a twofold increase in frailty,5 and several prospective studies and a meta-analysis have shown frailty variously defined to be associated with the development of CVD.6–8

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Shrauner et al. report on the association between frailty and incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in >3 million US veterans aged >65 years who were predominantly white males.9 Frailty was defined according to the Rockwood accumulative deficit model which included 31 items including CVD. The veterans were divided into five frailty status categories, i.e. none, pre-frail, mildly frail, moderately frail, and severely frail. Over the 15-year follow-up period from 2002 to 2017, the survival rate for CVD mortality decreased progressively from ∼75% in the pre-frail group to just over 25% in the severely frail group. Presence of frailty was associated with increased risk of CVD morbidity (stroke or myocardial infarction) and mortality after taking conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as hyperlipidaemia, smoking, and treatment (statins, antihypertensive drugs) into account, and a dose–response association was seen with increasing severity of frailty. The hazard ratio for CVD deaths increased from 1.6 in pre-frail to 2.7 in those with mild, to 4.3 in those with moderate, and to 7.9 in those with severe frailty. The relative risk of CVD in those who were pre-frail was comparable with that of those reported in the meta-analysis by Veronese et al. 6 but the relative risk associated with frailty was higher. However, it should be noted that in the study performed by Shrauner et al. some important risk factors such as obesity, nutrition, and physical activity, which relate to both frailty and CVD, were not taken into account.

The results of this study are not unexpected and confirm previous recent reports that frailty is associated with increased risk of CVD morbidity and mortality.6–8 The importance of the findings from this study was that it was conducted in a very large cohort of >3 million veterans screened in the 2000s when use of statin therapy and high potency antiplatelet agents was more widespread, and the authors assessed the changing trend in the association between frailty and subsequent CVD mortality and morbidity from 2002 to 2014. Despite the increasing prevalence and severity of frailty from 2002 to 2012, there was a trend towards lower rates of CVD deaths overall but, interestingly, rates for developing myocardial infarction remained unchanged. Compared with the non-frail group, the relative risk of CVD mortality associated with severe frailty dropped from 8.6 in 2002 to 6.2 in 2014, and in those with pre-frailty the corresponding relative risk dropped from 1.8 to 1.4. The decline in CVD mortality rates mirrors the overall decline in deaths from CVD seen in the USA10 which is likely to reflect the more effective and advanced CVD therapeutic treatments as well as the impact of medical advances in the prevention and management of CVD risk factors. The observation that there was no changing trend in the association between frailty and incident myocardial infarction is of interest, although the authors do not allude to this.

The study by Shrauner et al. has obvious strengths. It was based on a very large study with long follow-up duration. The study provides a strong body of evidence that frailty is associated with an increased risk of CVD morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, there are also some limitations. Despite the large population studied, the US veterans are not representative of the general population, and women and other ethnic groups are under-represented. Many important potential confounders such as obesity and physical activity were not included, and the frailty index included people with CVD and several other comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and lung disease, which may have overestimated the risk of CVD mortality associated with frailty. Although the authors carried out a sensitivity analysis excluding those with CVD, the other conditions mentioned above are known to be associated with increased CVD risk. Comparisons of different frailty indices have shown that the strongest and more stable associations after adjustment with CVD events were seen for scores from the ‘accumulation of deficits approach’ group.11 Importantly, the associations observed by Shrauner et al. do not prove causation, and it is unclear whether frailty is causally related to CVD or whether it is a biomarker of CVD risk.

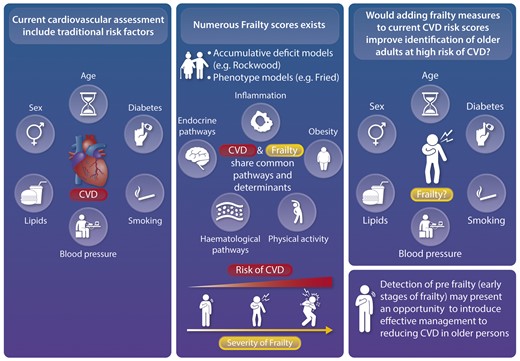

It would have been useful to see the characteristics and CVD risk profile of the veterans by frailty categories, which might help to explain the findings further. Population studies which have looked at the health profile of older adults have shown that frail older adults have an increased risk of a range of cardiovascular risk factors including obesity, HDL cholesterol, hypertension, heart rate, lung function, and renal function.12 This points to the need to manage the high cardiovascular risk in frail older people. Many common biological mechanisms may explain the connection between frailty and CVD, including inflammatory, haematological, and endocrine pathways.5 , 13 Frailty is associated with a chronic state of low-grade inflammation13 which could trigger CVD. Further investigations into the mechanisms underlying frailty and CVD are needed. It would provide greater insight into why frail people may be at high risk of CVD which could in turn guide possible interventions.

The data provided by Shrauner et al. lend further support to the importance of frailty as a risk factor for CVD. This brings us to the question of whether frailty should be included in vascular risk assessment in older people (Graphical abstract). Frailty is a slowly progressing complex clinical syndrome that can be identified at an early stage. The findings from this and previous studies demonstrate that pre-frailty (early stages of frailty) already carries increased risk, and risk of CVD increases sharply once frailty is established. Thus, identifying pre-frailty, which is reversible, represents an important opportunity to reduce risk and improve CVD health and longevity. The current 2021 ESC guidelines do not recommend that frailty measures are included in formal CVD risk assessment.14 It is not known whether assessment of frailty adds significant value to traditional risk scores used to predict CVD events in older adults (Graphical abstract). Future investigations would need to assess whether frailty improves risk prediction in older people, particularly in those without CVD. Moreover, despite numerous efforts to develop frailty assessment tools over the last few decades, there is still no consensus on the optimal frailty assessment tool to incorporate into clinical practice, and there is high variability in the strength of the association between frailty scores and CVD outcomes.11 The Fried frailty phenotype, defined as three or more of unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, low grip strength, slow walking speed, and decreased physical activity,15 is commonly used to assess frailty and is extensively used in research. However, the measures included in the Fried score may not always be practical in primary care settings. Future research needs to evaluate the validity and clinical utility of simple frailty assessment for primary care use. An emerging area for frailty screening is the use of biomarkers to identify frail older adults, but to date no single marker may be adequate for frailty prediction or diagnosis.16 Importantly, more studies are required to assess whether intervention incurs benefit for CVD in those with frailty and there is a need for evidence-based guidelines on how to manage or treat frailty. The quest to find new risk markers to assess CVD risk continues, and frailty may be a promising additional marker where current prediction scores tend to predict less well in older adults. Screening for frailty is already recommended in specific settings and geriatric clinics. With an ageing population, much effort is needed to reduce adverse CVD events associated with frailty through developing preventive strategies and primary prevention approaches (early identification and management of frailty) in the wider older population as well as tailored targeted interventions for frail adults with CVD.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

References