-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Parisa Torabi, Giulia Rivasi, Viktor Hamrefors, Andrea Ungar, Richard Sutton, Michele Brignole, Artur Fedorowski, Early and late-onset syncope: insight into mechanisms, European Heart Journal, Volume 43, Issue 22, 7 June 2022, Pages 2116–2123, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac017

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Unexplained syncope is an important clinical challenge. The influence of age at first syncope on the final syncope diagnosis is not well studied.

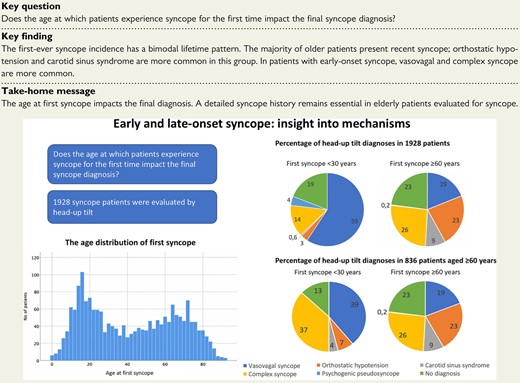

Consecutive head-up tilt patients (n = 1928) evaluated for unexplained syncope were stratified into age groups <30, 30–59, and ≥60 years based on age at first syncope. Clinical characteristics and final syncope diagnosis were analysed in relation to age at first syncope and age at investigation. The age at first syncope had a bimodal distribution with peaks at 15 and 70 years. Prodromes (64 vs. 26%, P < 0.001) and vasovagal syncope (VVS, 59 vs. 19%, P < 0.001) were more common in early-onset (<30 years) compared with late-onset (≥60 years) syncope. Orthostatic hypotension (OH, 3 vs. 23%, P < 0.001), carotid sinus syndrome (CSS, 0.6 vs. 9%, P < 0.001), and complex syncope (>1 concurrent diagnosis; 14 vs. 26%, P < 0.001) were more common in late-onset syncope. In patients aged ≥60 years, 12% had early-onset and 70% had late-onset syncope; older age at first syncope was associated with higher odds of OH (+31% per 10-year increase, P < 0.001) and CSS (+26%, P = 0.004). Younger age at first syncope was associated with the presence of prodromes (+23%, P < 0.001) and the diagnoses of VVS (+22%, P < 0.001) and complex syncope (+9%, P = 0.018).

In patients with unexplained syncope, first-ever syncope incidence has a bimodal lifetime pattern with peaks at 15 and 70 years. The majority of older patients present only recent syncope; OH and CSS are more common in this group. In patients with early-onset syncope, prodromes, VVS, and complex syncope are more common.

The age distribution of first-ever syncope in 1928 patients with unexplained syncope and the proportions of head-up tilt diagnoses in the same group and in a subgroup of 836 patients aged ≥60 years at investigation.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Age at first syncope: a consideration for assessing probable cause?’, by Shaun Colburn and David G. Benditt, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac122.

Introduction

Syncope is a common clinical problem, with ∼40% of the population experiencing at least one episode in their lifetime.1–4 The most common cause is vasovagal syncope (VVS), followed by orthostatic hypotension (OH) and cardiac syncope.1 The head-up tilt (HUT) test is used in clinical practice for diagnosing hypotensive susceptibility to vasovagal reflex and cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction as syncope aetiology.1

Epidemiological studies indicate that syncope has a bimodal incidence through life with peaks at 15–20 and >70 years.2,5–8 The incidence of syncope rises steeply after 70 years.9 Syncope aetiology differs with age. In the young, most cases are due to VVS, while cardiac syncope, OH, and effects of medications become more common in old age.6,10 Syncope in older patients is a diagnostic challenge as they tend to have short or absent prodromes and may present with falls where amnesia for the event conceals loss of consciousness.5,11,12 Data point to increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity following unexplained syncope.13

To establish effective diagnostic approaches for syncope, the causes in different age groups and factors associated with the final diagnosis need elucidation. One such factor is the age at which patients experience syncope for the first time. Only a few studies, focused on young adults or patients with an established VVS diagnosis, report the age at first syncope.2,14 It is unclear whether the age at first syncope impacts the results of syncope investigation.

The aim of the present study was to ascertain if the bimodal epidemiological pattern pertains to a large sample of unexplained syncope patients investigated in a specialized syncope unit and to study the influence of early-onset vs. late-onset syncope on clinical characteristics and final HUT diagnosis in this population.

Methods

Patient population

Patients were recruited from the previously described SYSTEMA cohort,15,16 which includes patients referred for investigation of syncope to the tertiary syncope unit at Skåne University Hospital in Malmö from hospitals and outpatient care in the southern Sweden.

During the study period from August 2008 to October 2018, a total of 1972 consecutive patients undergoing HUT for unexplained syncope were enrolled. Before referral to the syncope unit, initial evaluation was carried out according to the European syncope guidelines.1 The number and proportion of different tests made prior to referral is shown in Supplementary material online, Table S1. Patients with an established diagnosis of cardiac syncope or non-syncopal loss of consciousness were excluded. In patients aged <30 years, there were no known cases of congenital heart disease or channelopathies. Unexplained syncope was defined as a transient loss of consciousness without an established diagnosis after the initial evaluation according to the current syncope guidelines.1 This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The regional ethical review board in Lund, Sweden, approved the study protocol (reference number 82/2008) and all study participants gave written informed consent.

Investigation protocol

Data were drawn from medical history, including the year of the first-ever syncope, the total number of syncope episodes, and the characteristics of syncope-related symptoms of recent syncopes using a self-administered questionnaire. Evaluation in the syncope unit included a thorough history taking. Head-up tilt was performed according to the Italian protocol,17 i.e. a drug-free HUT phase of 20 min or until syncope occurred and if the drug-free phase was negative, 400 μg sublingual nitroglycerine was administered, and the patient remained tilted upright for another 15 min. Beat-to-beat blood pressure and electrocardiogram were monitored continuously by a validated non-invasive photoplethysmographic method (Nexfin monitor; BMEYE, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, or Finapres Nova, Finapres Medical Systems, PH Enschede, The Netherlands).18,19

Vasovagal reflex syncope was defined as a characteristic pattern of hypotension and bradycardia accompanied by reproduction of the patient’s typical symptoms/syncope.

Orthostatic hypotension was defined as a sustained decrease in systolic blood pressure ≥20 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥10 mmHg during HUT, including both classical and delayed OH.20 Carotid sinus hypersensitivity (CSH) was defined as a fall in systolic blood pressure of ≥50 mmHg and/or ventricular pause of ≥3 s on carotid sinus massage (CSM). If spontaneous syncope had previously occurred and was reproduced by the massage, CSH was interpreted as carotid sinus syndrome (CSS).1

Complex syncope was defined as the detection of two or more concomitant diagnoses (CSH/CSS, VVS, and OH) during CSM and HUT which could contribute to syncope episodes. Orthostatic hypotension and VVS were diagnosed in the same patient during HUT if there was first a sustained decrease in blood pressure as defined above, and then a rapid decrease in blood pressure and heart rate, leading to syncope, as previously proposed.1,21

No definite HUT diagnosis was defined as a normal haemodynamic response to HUT and CSM. Psychogenic pseudosyncope (PPS) was defined as apparent loss of consciousness during HUT with no decrease in blood pressure or heart rate, and characteristic features as previously defined.22 In unresolved cases, the diagnosis was adjudicated by at least two syncope unit physicians. When HUT was non-diagnostic, further evaluation for cardiac and non-cardiac syncope and epilepsy was recommended.

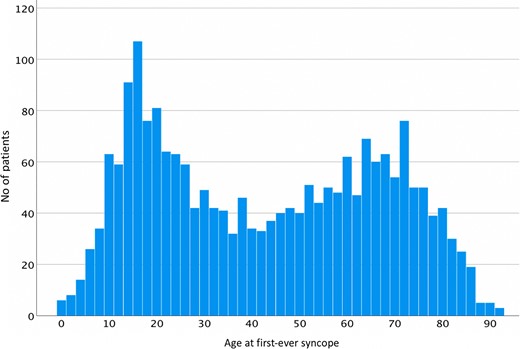

A histogram of the age at first-ever syncope was plotted to determine the age distribution. The study population was stratified into three age groups, <30, 30–59, and ≥60 years. The <30 and ≥60-year groups corresponded to the two peaks of the first-ever syncope incidence, as shown in Figure 1; the middle-age group corresponded to the nadir of lower first syncope incidence. A histogram of the distribution of age at investigation for unexplained syncope was also plotted (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). The clinical characteristics and the final HUT diagnoses were analysed in relation to age at first syncope and age at investigation.

Age distribution of first-ever syncope in 1928 patients with unexplained syncope.

Statistical analysis

The main characteristics of the study population are presented as mean and standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, as median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed variables, and number with percentages for categorical variables.

Pearson’s χ 2 test was used for comparisons between the age groups for categorical variables, and analysis of variance test and Fisher’s least significance difference test were used for continuous variables. Additional analyses were performed, exploring the effect of age at first syncope treated as a continuous variable on the final diagnosis in patients aged ≥60 years at examination. A logistic regression model was applied by entering age at first syncope as the independent variable and final HUT diagnosis as the dependent variable.

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered significant, except for the intergroup comparisons (n = 3), where significance level was set at P = 0.017 after Bonferroni correction.

Results

Basic cardiovascular autonomic testing (active standing, Valsalva manoeuvre, CSM, and HUT) was performed in 1972 patients (61% women; 52 ± 21 years) and data on age at first syncope were available for 1928 patients. The distribution of age at first syncope was bimodal with the highest peak at 15 years and a smaller peak at 70 years (Figure 1). The distribution of age at examination had the highest peak at 75 years and a smaller peak at 20 years (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

Clinical characteristics and HUT diagnoses of the study population, stratified according to age at first syncope, are presented in Table 1.

Clinical features and head-up tilt diagnoses of 1928 patients with unexplained syncope, according to age at first syncope

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 773) . | 30–59 years (n = 570) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Age at examination, median (IQR) | 28 (22–43) | 52 (44–60) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 578 (75) | 324 (57) | 276 (47) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 10 (2–30) | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total number of syncope episodes, median (IQR) | 7 (3–20) | 4 (2–10) | 3 (2–6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.136 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 124 ± 17 | 133 ± 20 | 144 ± 23 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 71 ± 10 | 75 ± 11 | 74 ± 12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.209 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.519 | 0.996 | 0.542 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 496 (64) | 269 (47) | 149 (26) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 290 (41) | 166 (34) | 71 (15) | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 590 (76) | 380 (67) | 398 (68) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.562 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (8) | 145 (26) | 341 (59) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 13 (2) | 29 (5) | 79 (14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VVS, n (%) | 455 (59) | 251 (44) | 108 (19) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 24 (3) | 54 (10) | 133 (23) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 14 (2.5) | 54 (9) | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 106 (14) | 97 (17) | 152 (26) | 0.096 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PPS, n (%) | 33 (4) | 9 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| No HUT diagnosis, n (%) | 148 (19) | 144 (25) | 135 (23) | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.404 |

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 773) . | 30–59 years (n = 570) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Age at examination, median (IQR) | 28 (22–43) | 52 (44–60) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 578 (75) | 324 (57) | 276 (47) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 10 (2–30) | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total number of syncope episodes, median (IQR) | 7 (3–20) | 4 (2–10) | 3 (2–6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.136 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 124 ± 17 | 133 ± 20 | 144 ± 23 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 71 ± 10 | 75 ± 11 | 74 ± 12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.209 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.519 | 0.996 | 0.542 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 496 (64) | 269 (47) | 149 (26) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 290 (41) | 166 (34) | 71 (15) | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 590 (76) | 380 (67) | 398 (68) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.562 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (8) | 145 (26) | 341 (59) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 13 (2) | 29 (5) | 79 (14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VVS, n (%) | 455 (59) | 251 (44) | 108 (19) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 24 (3) | 54 (10) | 133 (23) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 14 (2.5) | 54 (9) | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 106 (14) | 97 (17) | 152 (26) | 0.096 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PPS, n (%) | 33 (4) | 9 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| No HUT diagnosis, n (%) | 148 (19) | 144 (25) | 135 (23) | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.404 |

The Bonferroni-adjusted significance level was set at P = 0.017.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; CAD, coronary artery disease; VVS, vasovagal syncope; OH, orthostatic hypotension; CSH, carotid sinus hypersensitivity; CSS, carotid sinus syndrome; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; HUT, head-up tilt; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Clinical features and head-up tilt diagnoses of 1928 patients with unexplained syncope, according to age at first syncope

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 773) . | 30–59 years (n = 570) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Age at examination, median (IQR) | 28 (22–43) | 52 (44–60) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 578 (75) | 324 (57) | 276 (47) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 10 (2–30) | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total number of syncope episodes, median (IQR) | 7 (3–20) | 4 (2–10) | 3 (2–6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.136 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 124 ± 17 | 133 ± 20 | 144 ± 23 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 71 ± 10 | 75 ± 11 | 74 ± 12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.209 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.519 | 0.996 | 0.542 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 496 (64) | 269 (47) | 149 (26) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 290 (41) | 166 (34) | 71 (15) | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 590 (76) | 380 (67) | 398 (68) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.562 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (8) | 145 (26) | 341 (59) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 13 (2) | 29 (5) | 79 (14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VVS, n (%) | 455 (59) | 251 (44) | 108 (19) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 24 (3) | 54 (10) | 133 (23) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 14 (2.5) | 54 (9) | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 106 (14) | 97 (17) | 152 (26) | 0.096 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PPS, n (%) | 33 (4) | 9 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| No HUT diagnosis, n (%) | 148 (19) | 144 (25) | 135 (23) | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.404 |

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 773) . | 30–59 years (n = 570) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Age at examination, median (IQR) | 28 (22–43) | 52 (44–60) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 578 (75) | 324 (57) | 276 (47) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 10 (2–30) | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total number of syncope episodes, median (IQR) | 7 (3–20) | 4 (2–10) | 3 (2–6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.136 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 124 ± 17 | 133 ± 20 | 144 ± 23 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 71 ± 10 | 75 ± 11 | 74 ± 12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.209 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.519 | 0.996 | 0.542 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 496 (64) | 269 (47) | 149 (26) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 290 (41) | 166 (34) | 71 (15) | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 590 (76) | 380 (67) | 398 (68) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.562 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (8) | 145 (26) | 341 (59) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 13 (2) | 29 (5) | 79 (14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VVS, n (%) | 455 (59) | 251 (44) | 108 (19) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 24 (3) | 54 (10) | 133 (23) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 14 (2.5) | 54 (9) | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 106 (14) | 97 (17) | 152 (26) | 0.096 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PPS, n (%) | 33 (4) | 9 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| No HUT diagnosis, n (%) | 148 (19) | 144 (25) | 135 (23) | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.404 |

The Bonferroni-adjusted significance level was set at P = 0.017.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; CAD, coronary artery disease; VVS, vasovagal syncope; OH, orthostatic hypotension; CSH, carotid sinus hypersensitivity; CSS, carotid sinus syndrome; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; HUT, head-up tilt; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

In 1928 patients (Table 1), prodromes (nausea, sweating, and pallor, 64 vs. 26%, P < 0.001), palpitations (41 vs. 15%, P < 0.001), VVS (59 vs. 19%, P < 0.001), and PPS (4 vs. 0.2%, P < 0.001) were more common in early-onset (<30 years) compared with late-onset (≥60 years) syncope. Orthostatic hypotension (3 vs. 23%, P < 0.001), CSH/CSS (0.6 vs. 9%, P < 0.001), and complex syncope (14 vs. 26%, P < 0.001) were more common in late-onset syncope. The proportion of patients with no definitive diagnosis after HUT was not significantly different between early-onset and late-onset syncope groups.

In 836 patients investigated at age ≥60 years (Table 2), 12% reported having early-onset syncope and 70% reported late-onset syncope. Vasovagal syncope as a single diagnosis was more common in early-onset compared with late-onset syncope (39 vs. 19%, P < 0.001). Orthostatic hypotension was more common in late-onset syncope (23 vs. 7%, P < 0.001), as was hypertension (59 vs. 40%, P = 0.001). Complex syncope aetiology (findings suggesting overlap between VVS, OH, and/or CSH/CSS) tended to be more common among patients with early-onset syncope (37 vs. 26%, P = 0.023). Prodromes were less common in late-onset syncope (26 vs. 52%, P < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference in reported palpitations preceding syncope and dizziness on standing. In a logistic regression model of patients aged ≥60 years (Table 3), older age at first syncope was a significant predictor of OH (+31% per 10-year difference, <0.001) and CSH/CSS (+26%, P = 0.004). In contrast, younger age at first syncope predicted the occurrence of prodromes (+23% per 10-year difference, P < 0.001), VVS (+22%, P < 0.001), and complex syncope (+9%, P = 0.018).

Clinical features of the 836 patients who were examined at ≥60 years according to age at first syncope

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 100) . | 30–59 years (n = 151) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 71 (71) | 83 (55) | 276 (47) | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.088 |

| Age at investigation, median (IQR) | 70 (65–75) | 64 (61–70) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 54 (46–60) | 11 (5–20) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total no. of syncopes, median (IQR) | 8 (3–20) | 6 (3–10) | 3 (2–6) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 145 ± 19 | 141 ± 22 | 144 ± 23 | 0.256 | 0.910 | 0.143 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 77 ± 11 | 75 ± 12 | 74 ± 12 | 0.316 | 0.026 | 0.222 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.804 | 0.689 | 0.902 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 51 (52) | 52 (34) | 149 (26) | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.113 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 13 (13) | 28 (19) | 71 (12) | 0.146 | 0.186 | 0.136 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 69 (69) | 98 (65) | 398 (68) | 0.500 | 0.884 | 0.431 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 40 (40) | 70 (47) | 341 (59) | 0.307 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 8 (8) | 15 (10) | 79 (14) | 0.609 | 0.129 | 0.241 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2 (2) | 8 (5) | 50 (9) | 0.198 | 0.024 | 0.186 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (9) | 13 (9) | 113 (20) | 0.921 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| VVS, n (%) | 39 (39) | 47 (31) | 108 (19) | 0.198 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 7 (7) | 21 (14) | 133 (23) | 0.089 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) | 54 (9) | 0.637 | 0.082 | 0.120 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 37 (37) | 45 (30) | 152 (26) | 0.234 | 0.023 | 0.351 |

| PPS, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.415 | 0.697 | 0.302 |

| No diagnosis, n (%) | 13 (13) | 29 (19) | 135 (23) | 0.197 | 0.023 | 0.299 |

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 100) . | 30–59 years (n = 151) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 71 (71) | 83 (55) | 276 (47) | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.088 |

| Age at investigation, median (IQR) | 70 (65–75) | 64 (61–70) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 54 (46–60) | 11 (5–20) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total no. of syncopes, median (IQR) | 8 (3–20) | 6 (3–10) | 3 (2–6) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 145 ± 19 | 141 ± 22 | 144 ± 23 | 0.256 | 0.910 | 0.143 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 77 ± 11 | 75 ± 12 | 74 ± 12 | 0.316 | 0.026 | 0.222 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.804 | 0.689 | 0.902 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 51 (52) | 52 (34) | 149 (26) | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.113 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 13 (13) | 28 (19) | 71 (12) | 0.146 | 0.186 | 0.136 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 69 (69) | 98 (65) | 398 (68) | 0.500 | 0.884 | 0.431 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 40 (40) | 70 (47) | 341 (59) | 0.307 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 8 (8) | 15 (10) | 79 (14) | 0.609 | 0.129 | 0.241 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2 (2) | 8 (5) | 50 (9) | 0.198 | 0.024 | 0.186 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (9) | 13 (9) | 113 (20) | 0.921 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| VVS, n (%) | 39 (39) | 47 (31) | 108 (19) | 0.198 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 7 (7) | 21 (14) | 133 (23) | 0.089 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) | 54 (9) | 0.637 | 0.082 | 0.120 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 37 (37) | 45 (30) | 152 (26) | 0.234 | 0.023 | 0.351 |

| PPS, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.415 | 0.697 | 0.302 |

| No diagnosis, n (%) | 13 (13) | 29 (19) | 135 (23) | 0.197 | 0.023 | 0.299 |

The Bonferroni-adjusted significance level was set at P = 0.017.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; CAD, coronary artery disease; VVS, vasovagal syncope; OH, orthostatic hypotension; CSH, carotid sinus hypersensitivity; CSS, carotid sinus syndrome; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Clinical features of the 836 patients who were examined at ≥60 years according to age at first syncope

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 100) . | 30–59 years (n = 151) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 71 (71) | 83 (55) | 276 (47) | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.088 |

| Age at investigation, median (IQR) | 70 (65–75) | 64 (61–70) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 54 (46–60) | 11 (5–20) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total no. of syncopes, median (IQR) | 8 (3–20) | 6 (3–10) | 3 (2–6) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 145 ± 19 | 141 ± 22 | 144 ± 23 | 0.256 | 0.910 | 0.143 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 77 ± 11 | 75 ± 12 | 74 ± 12 | 0.316 | 0.026 | 0.222 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.804 | 0.689 | 0.902 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 51 (52) | 52 (34) | 149 (26) | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.113 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 13 (13) | 28 (19) | 71 (12) | 0.146 | 0.186 | 0.136 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 69 (69) | 98 (65) | 398 (68) | 0.500 | 0.884 | 0.431 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 40 (40) | 70 (47) | 341 (59) | 0.307 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 8 (8) | 15 (10) | 79 (14) | 0.609 | 0.129 | 0.241 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2 (2) | 8 (5) | 50 (9) | 0.198 | 0.024 | 0.186 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (9) | 13 (9) | 113 (20) | 0.921 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| VVS, n (%) | 39 (39) | 47 (31) | 108 (19) | 0.198 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 7 (7) | 21 (14) | 133 (23) | 0.089 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) | 54 (9) | 0.637 | 0.082 | 0.120 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 37 (37) | 45 (30) | 152 (26) | 0.234 | 0.023 | 0.351 |

| PPS, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.415 | 0.697 | 0.302 |

| No diagnosis, n (%) | 13 (13) | 29 (19) | 135 (23) | 0.197 | 0.023 | 0.299 |

| Clinical features . | First syncope . | P-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years (n = 100) . | 30–59 years (n = 151) . | ≥60 years (n = 585) . | <30 vs. 30–59 years . | <30 vs. ≥60 years . | 30–59 vs. ≥60 years . | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 71 (71) | 83 (55) | 276 (47) | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.088 |

| Age at investigation, median (IQR) | 70 (65–75) | 64 (61–70) | 74 (69–80) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Years between first syncope and investigation, median (IQR) | 54 (46–60) | 11 (5–20) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total no. of syncopes, median (IQR) | 8 (3–20) | 6 (3–10) | 3 (2–6) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Supine SBP, mean ± SD | 145 ± 19 | 141 ± 22 | 144 ± 23 | 0.256 | 0.910 | 0.143 |

| Supine DBP, mean ± SD | 77 ± 11 | 75 ± 12 | 74 ± 12 | 0.316 | 0.026 | 0.222 |

| Supine HR, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.804 | 0.689 | 0.902 |

| Prodromes, n (%) | 51 (52) | 52 (34) | 149 (26) | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.113 |

| Palpitations, n (%) | 13 (13) | 28 (19) | 71 (12) | 0.146 | 0.186 | 0.136 |

| Dizziness upon standing, n (%) | 69 (69) | 98 (65) | 398 (68) | 0.500 | 0.884 | 0.431 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 40 (40) | 70 (47) | 341 (59) | 0.307 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 8 (8) | 15 (10) | 79 (14) | 0.609 | 0.129 | 0.241 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2 (2) | 8 (5) | 50 (9) | 0.198 | 0.024 | 0.186 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (9) | 13 (9) | 113 (20) | 0.921 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| VVS, n (%) | 39 (39) | 47 (31) | 108 (19) | 0.198 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| OH, n (%) | 7 (7) | 21 (14) | 133 (23) | 0.089 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| CSS/CSH, n (%) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) | 54 (9) | 0.637 | 0.082 | 0.120 |

| Complex syncope, n (%) | 37 (37) | 45 (30) | 152 (26) | 0.234 | 0.023 | 0.351 |

| PPS, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.415 | 0.697 | 0.302 |

| No diagnosis, n (%) | 13 (13) | 29 (19) | 135 (23) | 0.197 | 0.023 | 0.299 |

The Bonferroni-adjusted significance level was set at P = 0.017.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; CAD, coronary artery disease; VVS, vasovagal syncope; OH, orthostatic hypotension; CSH, carotid sinus hypersensitivity; CSS, carotid sinus syndrome; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Association between self-reported age at first-ever syncope and outcome of carotid sinus massage and tilt testing in 836 unexplained syncope patients aged ≥60 years

| . | Odds ratioa . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| VVS | 0.78 | 0.71–0.86 | <0.001 |

| OH | 1.31 | 1.18–1.43 | <0.001 |

| CSH/CSS | 1.26 | 1.08–1.45 | 0.004 |

| Complex syncope | 0.91 | 0.84–0.98 | 0.018 |

| PPS | 0.89 | 0.29–1.53 | 0.730 |

| No diagnosis | 1.09 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.069 |

| Prodromes | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | <0.001 |

| . | Odds ratioa . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| VVS | 0.78 | 0.71–0.86 | <0.001 |

| OH | 1.31 | 1.18–1.43 | <0.001 |

| CSH/CSS | 1.26 | 1.08–1.45 | 0.004 |

| Complex syncope | 0.91 | 0.84–0.98 | 0.018 |

| PPS | 0.89 | 0.29–1.53 | 0.730 |

| No diagnosis | 1.09 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.069 |

| Prodromes | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | <0.001 |

VVS, vasovagal syncope; OH, orthostatic hypotension; CSH, carotid sinus hypersensitivity; CSS, carotid sinus syndrome; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; CI, confidence interval.

Odds ratios are presented per 10-year increment of first-ever syncope age.

Association between self-reported age at first-ever syncope and outcome of carotid sinus massage and tilt testing in 836 unexplained syncope patients aged ≥60 years

| . | Odds ratioa . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| VVS | 0.78 | 0.71–0.86 | <0.001 |

| OH | 1.31 | 1.18–1.43 | <0.001 |

| CSH/CSS | 1.26 | 1.08–1.45 | 0.004 |

| Complex syncope | 0.91 | 0.84–0.98 | 0.018 |

| PPS | 0.89 | 0.29–1.53 | 0.730 |

| No diagnosis | 1.09 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.069 |

| Prodromes | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | <0.001 |

| . | Odds ratioa . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| VVS | 0.78 | 0.71–0.86 | <0.001 |

| OH | 1.31 | 1.18–1.43 | <0.001 |

| CSH/CSS | 1.26 | 1.08–1.45 | 0.004 |

| Complex syncope | 0.91 | 0.84–0.98 | 0.018 |

| PPS | 0.89 | 0.29–1.53 | 0.730 |

| No diagnosis | 1.09 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.069 |

| Prodromes | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | <0.001 |

VVS, vasovagal syncope; OH, orthostatic hypotension; CSH, carotid sinus hypersensitivity; CSS, carotid sinus syndrome; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; CI, confidence interval.

Odds ratios are presented per 10-year increment of first-ever syncope age.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the effect of age at syncope onset on the clinical features and final diagnosis in a large cohort of unexplained syncope patients evaluated in a syncope unit.

The age at first syncope had a bimodal distribution with peaks at 15 and 70 years. The majority of patients aged ≥60 years experienced syncope for the first time at an older age and OH and CSS were more common in this group. In contrast, among older patients with early-onset syncope, prodromes, VVS, and complex syncope were more common (Structured Graphical Abstract).

Age distribution of first syncope

The age distribution of syncope has been reported in specific populations;2–4,6,7 however, data from a large population including patients with a wide range of ages are scarce. In a study of 394 medical students, 39% had experienced syncope and the median age at first syncope was 15 years.2 The lifetime cumulative incidence of syncope was 35% in 549 persons aged 35–60 years in the general population, with a peak age of 15 years at first syncope.3 The bimodal pattern with a second peak in the incidence of syncope after the age of 70 years has been reported in a general practitioner setting23 and in the Framingham Offspring Study.9

Our study confirms the bimodal age pattern at first syncope in the setting of unexplained syncope evaluated in a specialized syncope unit.

Clinical characteristics and head-up tilt diagnoses

Older syncope patients experience prodromes less frequently than younger patients.5,12,24–26 This has been attributed to amnesia12,27 or autonomic nervous system degeneration in older patients.26 We found that older patients with early-onset syncope reported prodromes more frequently compared with those having late-onset syncope (52 vs. 26%), indicating that the characteristics of life-long syncope (predominantly VVS) remain constant in this group of patients as they age.

Few studies report the age at first syncope and include only children,28 young adults,2 or predominantly VVS patients.14 The latter study included 443 VVS patients and 88 patients with other causes of syncope and found that VVS patients had their first syncope at a median age of 18 years, similar to our findings. They reported that age at onset <44 years was 86% accurate for VVS. However, the majority of included patients had VVS; in our study, the proportion of VVS was much lower. They found that 50% of older patients had their first syncope at a young age. We found that only 12% of older patients reported syncope in youth, this discrepancy could also be explained by the higher proportion of VVS in that study.

A shift in age peaks in the distributions of age at first syncope (Figure 1) and age at examination (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1) can be seen, with the highest peak in age at examination above 60 years and a lower syncope frequency at ages 30–60 years, indicating that syncope recurrences are less frequent at these ages.

The prevalence of OH and CSS is known to increase with age.23 Isolated OH was more common in older patients with late-onset compared with early-onset syncope. Hypertension was more frequent in this group, which is known to correlate with OH.29 In agreement with previous reports,30 older syncope patients with late-onset syncope had a higher probability of CSH/CSS.

Previous studies have shown that VVS often overlaps with OH and CSS in elderly patients and about 20% have more than one potential cause of syncope.31,32 Complex syncope in old age is caused by impaired autonomic function affecting baroreflex sensitivity, control of blood pressure and heart rate, cardiovascular comorbidities, and polypharmacy, all predisposing the ageing individual to syncope.23,31,33–35

In a study of 873 unexplained syncope patients evaluated with HUT, 23% had complex syncope. The most common combination was OH and VVS. The frequency of complex diagnosis increased with age.31 In another study of 987 unexplained syncope patients evaluated with HUT and electrophysiology, 18% had multiple potential causes of syncope, the most common combination was VVS and CSH. Older age, cardiovascular disease, arrhythmia, and malignancy were predictors of complex syncope.32

The influence of age at first syncope on the prevalence of complex syncope has not been previously studied. We found that the proportion of complex syncope rose with increasing age at first syncope. Complex syncope was more common in older patients with early-onset compared with late-onset syncope, as age-related conditions of OH and CSH/CSS develop in patients with pre-existing VVS susceptibility. The high prevalence of multiple causes of syncope in elderly patients stresses the need for a comprehensive evaluation including HUT. The benefit of HUT including autonomic function tests in the evaluation of unexplained syncope has been highlighted in a recent study.36

Syncope remained unexplained after HUT in 22% of patients. This finding is in accordance with previous studies.32,37,38 The proportion of patients with inconclusive HUT was not significantly different between early-onset and late-onset syncope groups. In patients aged ≥60 years, inconclusive HUT tended to be more common in late-onset compared with early-onset syncope (23 vs. 13%). Considering that hypertension and atrial fibrillation were also more common in elderly patients with late-onset syncope, we propose that, in this group, undetected cardiac syncope is more common, and may overlap with dysautonomic conditions.

Study limitations

This is a single-centre study; however, a large series of patients was included. The patients included in the study were referred for HUT and this may introduce a bias as they may not represent syncope patients in the general population. However, the patients that were referred likely represent those who were most symptomatic (frequent syncope or traumatic syncope) or had no characteristic prodromes and were difficult to diagnose without HUT. The main parameter in this study, i.e. age at first syncope, requires patients to recall events that occurred many years earlier and this can be a source of error, especially among elderly patients.

Conclusion

The first-ever syncope incidence in patients with unexplained syncope has a bimodal lifetime pattern with peaks at 15 and 70 years. The majority of older patients experience their first syncope when older and orthostatic hypotension and carotid sinus syndrome are more common in this group. In older patients with early-onset syncope, prodromes, vasovagal and complex syncope are more common. A detailed syncope history remains essential in elderly patients evaluated for syncope and impacts the final diagnosis.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was supported by Regional research funding in Skåne Sweden (grant number 2020-0280), Crafoord Foundation (grant number 20190006), Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (grant number 20190383), and ALF (grant number 46701).

Conflict of interest

A.F. receives lecture fees from Medtronic Inc., Biotronik, and Finapres Medical Systems. R.S. reports acting as a consultant to Medtronic Inc. and membership of Speakers bureau of Abbott Laboratories (SJM) Corp., and holds stock in Boston Scientific Corp., and Edwards Lifesciences Corp. All other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Definitions

Early-onset syncope: first syncope before the age of 30 years.

Late-onset syncope: first syncope after the age of 60 years.

Prodromes: nausea, sweating, pallor, lightheadedness, and premonition of imminent loss of consciousness.

Vasovagal syncope (VVS): a characteristic pattern of hypotension and bradycardia accompanied by reproduction of the patient’s typical symptoms/syncope.

Orthostatic hypotension (OH): a sustained decrease in systolic blood pressure ≥20 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥10 mmHg during head-up tilt (HUT), including both classical and delayed OH.

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity (CSH): a fall in systolic blood pressure of ≥50 mmHg and/or ventricular pause of ≥3 s on carotid sinus massage (CSM).

Carotid sinus syndrome (CSS): as CSH and reproduction of symptoms/syncope.

Complex syncope: the detection of two or more concomitant diagnoses (CSH/CSS, VVS, and OH) during CSM and HUT which could contribute to syncope episodes.

Psychogenic pseudosyncope: apparent loss of consciousness during HUT with no decrease in blood pressure or heart rate, and characteristic features as previously defined in the literature.

No definite HUT diagnosis: a normal haemodynamic response to HUT and CSM.

References

Author notes

Shared first authorship.